Destination Image Perception Mediated by Experience Quality: The Case of Qingzhou as an Emerging Destination in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

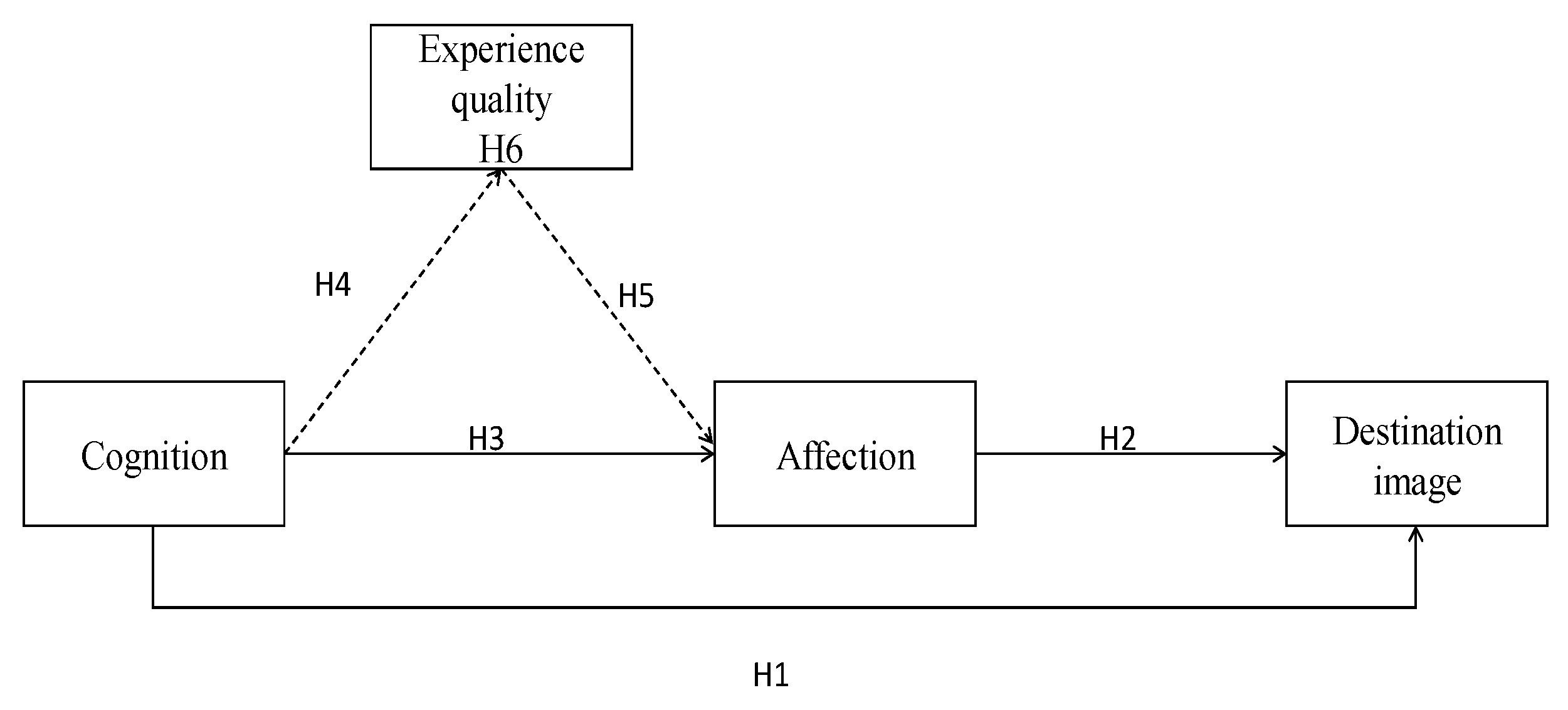

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Conceptual Framework of Destination Image

2.2. Experience Quality as a Mediator

2.2.1. Experience Quality

2.2.2. Relationship between Cognition and Experience Quality

2.2.3. Relationship between Experience Quality and Affection

3. Research Methods

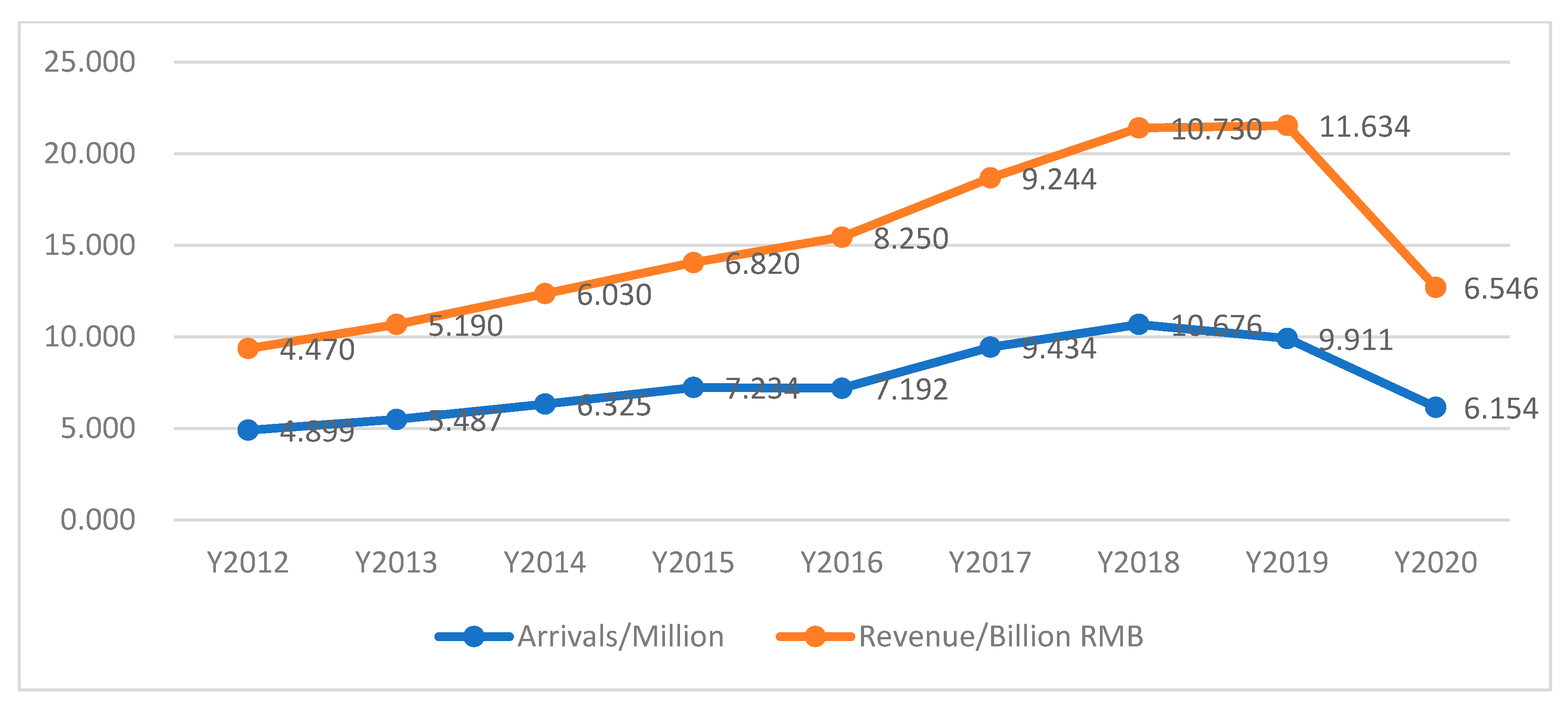

3.1. Study Setting

3.2. Instruments and Measurements

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Common Method Variance Test

4.2. EFA and CFA of Cognition

4.3. CFA of Experience Quality

4.4. Model Estimation

4.5. Reflective Measurement Model

4.6. Reflective-Formative Second-Order Constructs

4.7. Structural Model Assessment

4.8. Assessment of Mediating Effect (H6)

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Through exploratory factor and validation factor analysis, the empirical study proved that the scale has good reliability and validity, which provides inspiration for the study of measuring heritage tourism motivation.

- (2)

- Motivation has an important role in the formation process of tourists’ image perceptions of heritage tourism places, i.e., heritage tourism motivation has an important influence on destination image perceptions, and there are differences in the influences of each dimension on destination image perceptions. Specifically, the primary concern of educationally enlightened motivated tourists is the genus of the heritage attraction of the destination, as well as the communal and public benefit value of the heritage. They generally have the characteristics of being good learners and thinkers, care for others, have unique insights and opinions about heritage, and are willing to connect with others in the process of tourism, such as by participating in “fraternal” volunteer activities. In this process, they give more emotional value to the heritage tourism place, and thus, are more satisfied with the overall image of the tourism place after the tourism experience.

- (3)

- There is an influential relationship between the constructs of destination image. The cognitive image positively and significantly affects the emotional image and the overall image, and the emotional image positively and significantly affects the overall image.

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, C.; Ren, J.; Li, L. Spatial and temporal pattern characteristics and influencing factors of inbound tourism economy in western region. Ningxia Soc. Sci. 2019, 6, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Appraisal of literature on customer experience in tourismsector: Review and framework. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioral intentions: A meta analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and the Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic Processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Kim, W.G.; Li, J.; Hyeon, M. Make it delightful: Customers’ experience, satisfaction and loyalty in Malaysian theme parks. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunel, M.C.; Erkut, B. Cultural tourism in istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Burnkrant, R.E. Attitude organization and the attitude-behavior relation: A reply to Dillon and Kumar. J. Personal. Soc. Psycol. 1985, 49, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.; Crompton, J. Quality, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Zhu, Y.; He, D.; Tan, T.; Yang, X. Sources of tourism growth in Mainland China: An extended data envelopment analysis-based decomposition analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, D.J. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sanchez, J. Tourism image, evalutaiton variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, I.R.D.; Martin, H.S. Tourism Satisfaction: A Cognitive-Affective Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, H. A study on the negative perceptions of inbound tourists on the image of Chinese tourist destinations. World Geogr. Res. 2019, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A. Nature, aesthetic appreciation, and knowledge. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1995, 53, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCTV-10. The Local Records in China. 2018. Available online: https://tv.cctv.com/2018/02/24/VIDEeeJfVQelUAxsBHTAHLDb180224.shtml (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Cetin, G.; Bilgihan, A. Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.L.; Baum, T. Ecotourists’ perception of ecotourism experience in lower Kinabatangan, Sabah, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Horng, S.C. Conceptualising and measuring experience quality: The customer’s perspective. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 2401–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Memon, M.A.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Ramayah, T. Assessing reflective models in marketing research: A comparison between PLS and PLSc estimates. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, J.H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H. Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Ramayah, T.; Memon, M.A.; Cham, T.H.; Ciavolino, E. A comparisonof five reflective–formative estimation approaches: Reconsideration and recommendations for tourism research. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 1421–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.S.; Crompton, J.; Willson, V. An empirical investigation of the relationships between service quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions among visitors to a wildlife refuge. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon the image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 4, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourists’ images of a destination-an alternative analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1996, 5, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslandes, D.; Goldsmith, R.; Bonn, M.; Joseph, S. Measuring destination image: Do the existing scales work? Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 10, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The measurement of destination image: An empirical assessment. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioural, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A. Reassessing the foundations of customer delight. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 8, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Liang, S.; Law, R.; Sun, W. How do domestic and international high-end hotel brands receive and manage customer feedback? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghinea, G.; Chen, S.Y. Measuring quality of perception in distributed multimedia: Verbalizers vs. imagers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, S.R.; Ghinea, G. Defining user perception of distributed multimedia quality, ACM transactions on multimedia computing. Commun. Appl. 2006, 2, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacation Scape: Designing Tourist Regions; Van Nostrum Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, K.; Zehrer, A.; Muller, S. Perceived Destination Image: An Image Model for a Winter Sports Destination and Its Effect on Intention to Revisit. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hede, A.-M.; Garma, R.; Josiassen, A.; Thyne, M. Perceived authenticity of the visitor experience in museums: Conceptualization and initial empirical findings. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1395–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xie, M.; Li, W.; Tai, J. Review of Digital Economy Research in China: A Framework Analysis Based on Bibliometrics. Comput. Intel. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2427034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Lu, L. Study on the perception process of destination image under the influence of tourism promotional film—An experimental exploration of Bali case. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 34, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Chen, H. Analysis of the influence of the cognitive image of hot spring tourism places on tourists’ experience and behavior. Geogr. Res. Dev. 2015, 34, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.; Jane, H.B. Market orientation and hotel performance: Investigating the role of high-order marketing capabilities. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1885–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Jana, R.; Ida, R.I.; Christian, M.R. The agony of choice for medicaltourists: A patient satisfaction index model. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Tai, J.; Zhang, C. A Bibliometric-Based Analytical Framework for the Study of Smart City Lifeforms in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, B. The influence of customer experience quality on customers’ behavioral intentions. Serv. Mark. Q. 2013, 34, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, P.; Maklan, S. EXQ: A multiple-scale for assessing service experience. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. Advancing destination image: The destination content model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, G.C.M.; Mak, A.H.N. Exploring the discrepancies in perceived destination images from residents’ and tourists’ perspectives: A revised importance-performance analysis approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1124–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasalle, D.; Britton, T. Priceless: Turning Ordinary Products into Extraordinary Experiences; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Phau, I.; Hughes, M.; Li, Y.F.; Quintal, V. Heritage tourism in Singapore chinatown: A perceived value approach to authenticity and satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Workman, J.E. Consumer tendency to regret, compulsive buying, gender, and fashion time-of-adoption groups. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2018, 11, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Cheer, J.M.; Haywood, M.; Brouder, P.; Salazar, N.B. Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; da Silva, R.V.; Antova, S. Image, satisfaction, destination and product post-visit behaviours: How do they relate in emerging destinations? Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, D.; Ren, W.; Zhang, W. Auto color correction of underwater images utilizing depth information. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1504805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Siamagka, N.T.; Moraes, C.; Micevski, M. Do marketers use visual representations of destinations that tourists value? comparing visitors’ image of a Destination with marketer-controlled images online. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, I.; Fujihara, K.; Miyazawa, I.; Misu, T.; Narikawa, K.; Nakamura, M.; Watanabe, S.; Takahashi, T.; Nishiyama, S.; Shiga, Y. Clinical and MRI features of Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis positive for NMO-IgG. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 1073–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neisser, U. Cognition and Reality: Principles and Implications of Cognitive Psychology; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling:helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R. Exploring the quality of the service experience: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Adv. Serv. Mark. Manag. 1995, 4, 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination positioning and temporality: Tracking relative strengths and weaknesses over time. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre Everybusiness a Stage; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, A.M.D.; Rodríguez, M.R.G.; Roldán, J.L. The role of authenticity, experience quality, emotions, and satisfaction in a cultural heritage destination. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.H.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Human Aspect of Urban Form; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Qiu, H.; Wang, P.L.; Lin, M.C.P. Exploring customer experience with budget hotels: Dimensionality and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C. Revolutionize Your Customer Experience, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, T.C.; David, S. Examining the mediatingr Role of experience quality in a model of tourist experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 16, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, L.L.; Wang, Y.P.; Liu, F.Z.; Guo, J.W.; Wang, R.X.; Nevin, A. Technical study of the paint layers from buddhist sculptures unearthed from the longxing temple site in Qingzhou, China. Heritage 2021, 4, 2599–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; Krakover, S. The formation of a composite urban image. Geogr. Anal. 1993, 25, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Sternberg, K. Cognitive Psy-Chology, 6th ed.; Wadsworth, Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. Three tales of a city: Stakeholders’ images of Eilat as a tourist destination. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Ma, Z. A multi-stakeholder examination of destination image: Nanluoguxiang heritage street, Beijing, China. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.K. Repeat visitation: A study from the perspective of leisure constraint, tourist experience, destination images, and experiential familiarity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Wei, Q.W. Touched by the Past? Re-Articulating the Longxing Temple Sites as Community Heritage at Qingzhou County, China. Archaeologies 2021, 17, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberghien, G.; Bremner, H.; Milne, S. Performance and visitors’ perception of authenticity in eco-cultural tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.; Fam, K.S.; Hwa, J.C.J.; Richard, J.E.; Xing, N. Ethnic food consumption intention at the touring destination: The national and regional perspectives using multi-group analysis. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.N.; Kline, S. From satisfaction to delight: A model for the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Crompton, J.L. Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. The importance of servicescapes in leisure service settings. J. Serv. Mark. 1994, 8, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walesska, S.; Amparo, C.T.; Carmen, P.C. Exploring the links between destination attributes, quality of service experience and loyalty in emerging Mediterranean destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100699. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, R. A cross-sectional examination of hotel consumer experience and relative effects on consumer values. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H. Partial Least Squares, Encyclopaedia of Statistical Sciences; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zins, A.H. Consumption emotions, experience quality and satisfaction: A structural analysis for complainers versus no complainers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Sample (n = 475) | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 153 | 32.21 |

| Female | 322 | 67.79 | |

| Age | <18 | 9 | 1.89 |

| 18–39 | 316 | 66.53 | |

| 40–60 | 148 | 31.16 | |

| >61 | 2 | 0.42 | |

| Educational background | Junior middle school | 27 | 5.68 |

| Senior middle school | 82 | 17.26 | |

| Undergraduate | 352 | 74.11 | |

| Master’s degree | 10 | 2.11 | |

| Doctoral degree | 4 | 0.84 | |

| Occupation | Self-employed | 23 | 4.84 |

| Public sector employee | 270 | 56.84 | |

| Self-employed | 41 | 8.63 | |

| House wife | 116 | 24.42 | |

| Between jobs | 1 | 0.21 | |

| Student | 24 | 5.05 | |

| Annual income (RMB 33,000) | Much more | 67 | 14.11 |

| More | 83 | 17.47 | |

| Equal to | 66 | 13.89 | |

| Lower | 83 | 17.47 | |

| Much lower | 176 | 37.05 | |

| Frequency of visits | First time | 276 | 58.11 |

| Repeat visit | 199 | 41.89 |

| Attributes | Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitating Supply | |||

| art cog | 0.835 | ||

| friendly residents cog | 0.830 | ||

| cleanliness cog | 0.821 | ||

| safety cog | 0.808 | ||

| price cog | 0.803 | ||

| ecology cog | 0.801 | ||

| participation cog | 0.795 | ||

| shopping cog | 0.787 | ||

| entertainment cog | 0.764 | ||

| informationalization cog | 0.762 | ||

| hotel cog | 0.755 | ||

| responsible government cog | 0.751 | ||

| festivals cog | 0.749 | ||

| food and beverage cog | 0.729 | ||

| transportation cog | 0.727 | ||

| nightlife cog | 0.707 | ||

| Intangible Attraction | |||

| imperial exam cog | 0.771 | ||

| Christianity cog | 0.755 | ||

| Han folklore | 0.648 | ||

| Manchu ethnic group folklore cog | 0.731 | ||

| Hui ethnic group folklore cog | 0.636 | ||

| Tangible Attraction | |||

| relics cog | 0.760 | ||

| buildings cog | 0.753 | ||

| forests and mountains cog | 0.737 | ||

| water cog services cog | 0.728 0.655 | ||

| flowers cog | 0.632 | ||

| Cumulative percentage of rotation sums of squared loadings | 41.046 | 63.031 | 83.103 |

| Factor | Item | Std. Error | p-Value | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Attraction | water cog | - | - | 0.915 | 0.684 |

| buildings cog | 0.076 | 0 | |||

| flowers cog | 0.072 | 0 | |||

| forests and mountains cog | 0.073 | 0 | |||

| relics cog | 0.066 | 0 | |||

| Intangible Attraction | Hui ethnic group folklore cog | - | - | 0.944 | 0.773 |

| Manchu ethnic group folklore cog | 0.048 | 0 | |||

| Han folklore cog | 0.046 | 0 | |||

| Christianity cog | 0.050 | 0 | |||

| imperial exam cog | 0.051 | 0 | |||

| Facilitating Supply | responsible government cog | - | - | 0.984 | 0.790 |

| festivals cog | 0.047 | 0 | |||

| participation cog | 0.048 | 0 | |||

| transportation cog | 0.052 | 0 | |||

| food and beverage cog | 0.046 | 0 | |||

| hotel cog | 0.051 | 0 | |||

| entertainment cog | 0.046 | 0 | |||

| nightlife cog | 0.052 | 0 | |||

| price cog | 0.054 | 0 | |||

| informationalization cog | 0.048 | 0 | |||

| art cog | 0.048 | 0 | |||

| ecology cog | 0.047 | 0 | |||

| shopping cog | 0.053 | 0 | |||

| friendly residents cog | 0.046 | 0 | |||

| safety cog | 0.046 | 0 | |||

| cleanliness cog | 0.050 | 0 |

| Tangible Attraction | Intangible Attraction | Facilitating Supply | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Attraction | 0.827 | ||

| Intangible Attraction | 0.818 | 0.879 | |

| Facilitating Supply | 0.798 | 0.840 | 0.889 |

| Factor | Item | Std. Error | p-Value | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Attraction | water ex | - | - | 0.940 | 0.757 |

| buildings ex | 0.043 | 0 | |||

| flowers ex | 0.048 | 0 | |||

| forests and mountains ex | 0.046 | 0 | |||

| relics ex | 0.044 | 0 | |||

| Intangible Attraction | Hui ethnic group folklore ex | - | - | 0.949 | 0.787 |

| Manchu ethnic group folklore ex | 0.033 | 0 | |||

| Han folklore ex | 0.031 | 0 | |||

| Christianity ex | 0.035 | 0 | |||

| imperial exam ex | 0.034 | 0 | |||

| Facilitating Supply | responsible government ex | - | - | 0.983 | 0.786 |

| friendly residents ex | 0.037 | 0 | |||

| safety experience ex | 0.035 | 0 | |||

| cleanliness ex | 0.039 | 0 | |||

| festivals ex | 0.037 | 0 | |||

| participation ex | 0.037 | 0 | |||

| price ex | 0.039 | 0 | |||

| informationalization ex | 0.039 | 0 | |||

| art ex | 0.037 | 0 | |||

| ecology ex | 0.035 | 0 | |||

| transportation ex | 0.041 | 0 | |||

| food and beverage ex | 0.036 | 0 | |||

| hotel ex | 0.038 | 0 | |||

| entertainment ex | 0.038 | 0 | |||

| nightlife ex | 0.039 | 0 | |||

| shopping ex | 0.040 | 0 |

| Tangible Attraction | Intangible Attraction | Facilitating Supply | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Attraction | 0.870 | ||

| Intangible Attraction | 0.811 | 0.887 | |

| Facilitating Supply | 0.815 | 0.844 | 0.887 |

| Construct | Sub-Dimension | Item | Loading | CA | Rho-A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition (C) | Tangible attraction cognition (TC) | water cog | 0.824 | 0.920 | 0.921 | 0.940 | 0.759 |

| buildings cog | 0.855 | ||||||

| flowers cog | 0.872 | ||||||

| forests and mountains cog | 0.896 | ||||||

| relics cog | 0.908 | ||||||

| Intangible attraction cognition (IC) | Hui ethnic group folklore cog | 0.908 | 0.949 | 0.950 | 0.961 | 0.831 | |

| Manchu ethnic group folklore cog | 0.930 | ||||||

| Han folklore cog | 0.885 | ||||||

| Christianity cog | 0.924 | ||||||

| imperial exam cog | 0.909 | ||||||

| Facilitation cognition (FC) | responsible government cog | 0.903 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 0.826 | |

| transportation cog | 0.869 | ||||||

| food and beverage cog | 0.918 | ||||||

| hotel cog | 0.903 | ||||||

| entertainment cog | 0.926 | ||||||

| nightlife cog | 0.900 | ||||||

| shopping cog | 0.908 | ||||||

| friendly residents cog | 0.929 | ||||||

| safety cog | 0.914 | ||||||

| cleanliness cog | 0.892 | ||||||

| festivals cog | 0.911 | ||||||

| participation cog | 0.922 | ||||||

| price cog | 0.890 | ||||||

| informationalization cog | 0.918 | ||||||

| art cog | 0.925 | ||||||

| iconology cog | 0.916 | ||||||

| Experience quality (E) | Tangible attraction experience quality (TE) | water ex | 0.842 | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.953 | 0.804 |

| buildings ex | 0.917 | ||||||

| flowers ex | 0.908 | ||||||

| forests and mountains ex | 0.922 | ||||||

| relics ex | 0.890 | ||||||

| Intangible attraction experience quality (IE) | Hui ethnic group folklore ex | 0.914 | 0.948 | 0.949 | 0.960 | 0.829 | |

| Manchu ethnic group folklore ex | 0.930 | ||||||

| Han folklore ex | 0.902 | ||||||

| Christianity ex | 0.907 | ||||||

| imperial exam ex | 0.898 | ||||||

| Facilitation experience quality (FE) | responsible government ex | 0.886 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.985 | 0.800 | |

| transportation ex | 0.868 | ||||||

| food and beverage ex | 0.910 | ||||||

| hotel ex | 0.899 | ||||||

| entertainment ex | 0.910 | ||||||

| nightlife ex | 0.894 | ||||||

| shopping ex | 0.899 | ||||||

| friendly residents ex | 0.9 | ||||||

| safety ex | 0.905 | ||||||

| cleanliness ex | 0.866 | ||||||

| festivals ex | 0.896 | ||||||

| participation ex | 0.915 | ||||||

| price ex | 0.892 | ||||||

| informationalization ex | 0.889 | ||||||

| art ex | 0.884 | ||||||

| iconology ex | 0.893 | ||||||

| Affection (A) | distressing–relaxed | 0.877 | 0.886 | 0.888 | 0.930 | 0.815 | |

| unpleasant–pleasant | 0.895 | ||||||

| sleepy–lively | 0.935 | ||||||

| Reflective Construct | A | FC | FE | IC | IE | OI | TC | TE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affection (A) | ||||||||

| Facilitation cognition (FC) | 0.671 | |||||||

| Facilitation experience quality (FE) | 0.726 | 0.820 | ||||||

| Intangible attraction cognition (IC) | 0.637 | 0.873 | 0.712 | |||||

| Intangible attraction experience quality (IE) | 0.683 | 0.713 | 0.875 | 0.820 | ||||

| Overall image (OI) | 0.626 | 0.647 | 0.764 | 0.592 | 0.677 | |||

| Tangible attraction cognition (TC) | 0.623 | 0.832 | 0.679 | 0.867 | 0.676 | 0.568 | ||

| Tangible attraction experience quality (TE) | 0.683 | 0.669 | 0.851 | 0.659 | 0.861 | 0.677 | 0.786 |

| Higher-Order Construct | Sub-Dimension | Convergent Validity | Outer Weights | Outer Variance Inflation Factor | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition (C) | Tangible attraction cognition (TC) | 0.861 | 0.116 | 3.307 | 1.237 | 0.216 |

| Intangible attraction cognition (IC) | 0.174 | 4.269 | 1.770 | 0.077 * | ||

| Facilitation cognition (FC) | 0.752 | 3.961 | 8.448 | 0.000 *** | ||

| Experience | Tangible attraction experience quality (TE) | 0.853 | 0.104 | 3.588 | 1.289 | 0.197 |

| quality (E) | Intangible attraction experience quality (IE) | 0.197 | 4.147 | 2.134 | 0.033 * | |

| Facilitation experience quality (FE) | 0.739 | 4.256 | 9.232 | 0.000 *** | ||

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Standard Beta | Standard Deviation | t-Value | p-Value | R2 | Variance Inflation Factor | f2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Cognition -> Overall image | 0.455 | 0.049 | 9.349 | 0 | 0.471 | 1.700 | 0.232 | 0.463 |

| H2 | Affection -> Overall image | 0.299 | 0.044 | 6.802 | 0 | 1.700 | 0.100 | ||

| H3 | Cognition -> Affection | 0.237 | 0.048 | 4.925 | 0 | 0.497 | 2.861 | 0.039 | 0.399 |

| H4 | Cognition -> Experience quality | 0.806 | 0.03 | 26.678 | 0 | 0.649 | 1.000 | 1.849 | 0.544 |

| H5 | Experience quality -> Affection | 0.500 | 0.046 | 10.747 | 0 | 2.861 | 0.174 |

| Mediating Relationship | Indirect Effect | Standard Deviation | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC -> FE -> A | 0.256 | 0.079 | 3.222 | 0.001 ** |

| TC -> TE -> A | 0.125 | 0.065 | 1.929 | 0.054 * |

| IC -> IE -> A | 0.027 | 0.075 | 0.363 | 0.717 |

| C -> E -> A | 0.402 | 0.040 | 9.980 | 0.000 *** |

| C -> A -> OI | 0.071 | 0.016 | 4.472 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, L.-P.; Ayob, N.; Puah, C.-H.; Arip, M.A.; Jong, M.-C. Destination Image Perception Mediated by Experience Quality: The Case of Qingzhou as an Emerging Destination in China. Electronics 2023, 12, 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12040945

Guan L-P, Ayob N, Puah C-H, Arip MA, Jong M-C. Destination Image Perception Mediated by Experience Quality: The Case of Qingzhou as an Emerging Destination in China. Electronics. 2023; 12(4):945. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12040945

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Li-Ping, Norazirah Ayob, Chin-Hong Puah, Mohammad Affendy Arip, and Meng-Chang Jong. 2023. "Destination Image Perception Mediated by Experience Quality: The Case of Qingzhou as an Emerging Destination in China" Electronics 12, no. 4: 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12040945

APA StyleGuan, L.-P., Ayob, N., Puah, C.-H., Arip, M. A., & Jong, M.-C. (2023). Destination Image Perception Mediated by Experience Quality: The Case of Qingzhou as an Emerging Destination in China. Electronics, 12(4), 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12040945