A Critical Examination of the Beam-Squinting Effect in Broadband Mobile Communication: Review Paper

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Broadband Communication

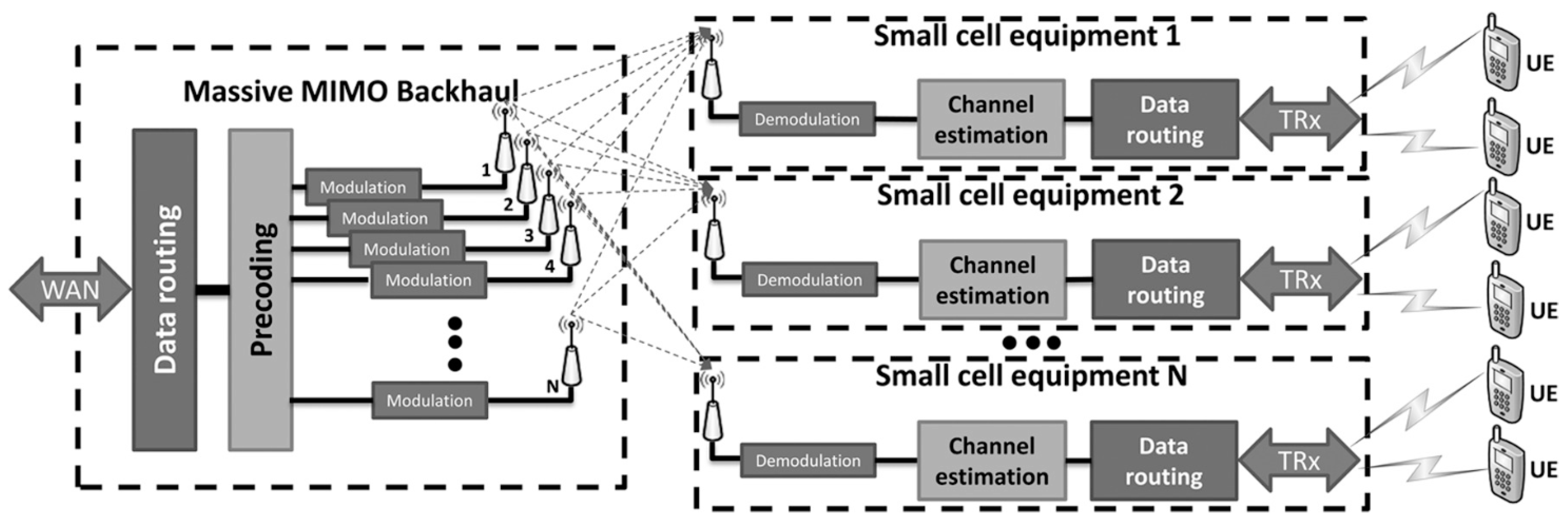

2.1. Millimeter Waves and Massive MIMO

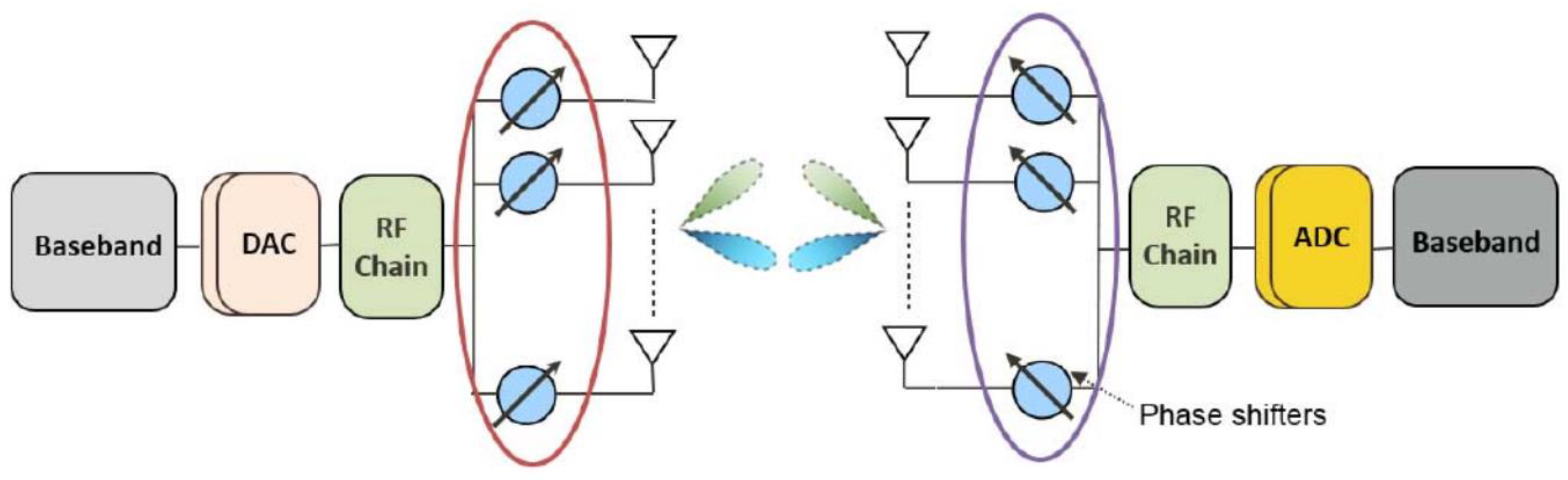

2.1.1. Analog Beamforming

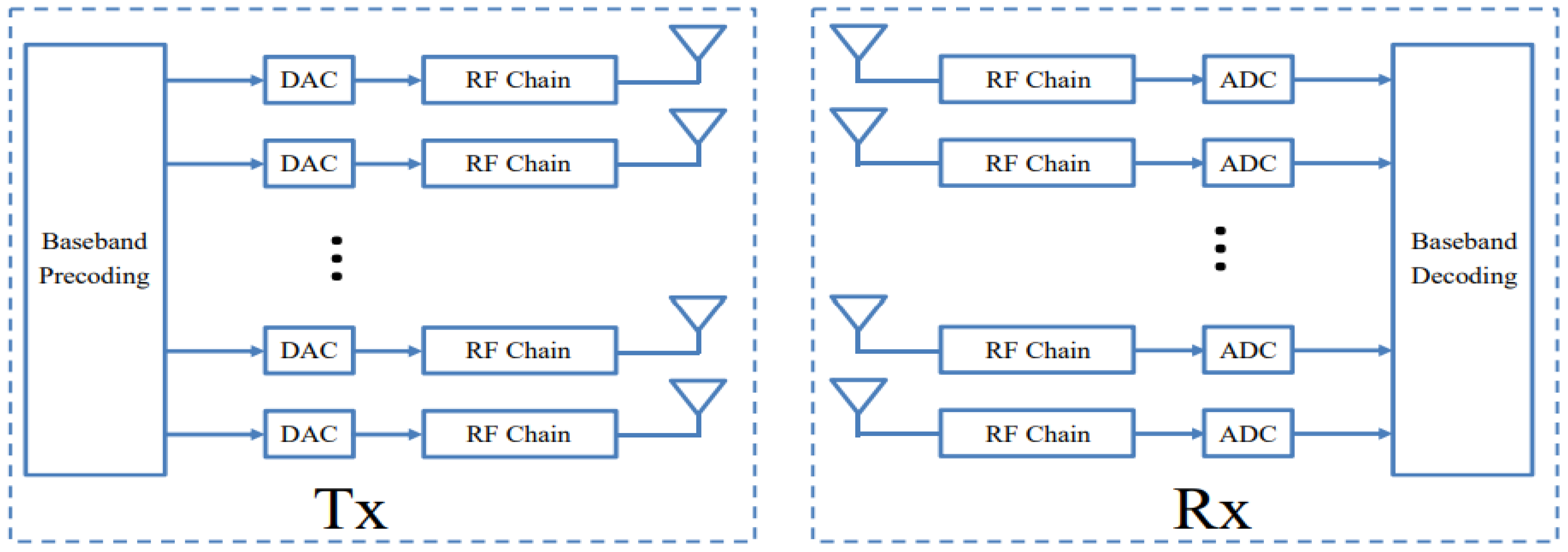

2.1.2. Digital Beamforming

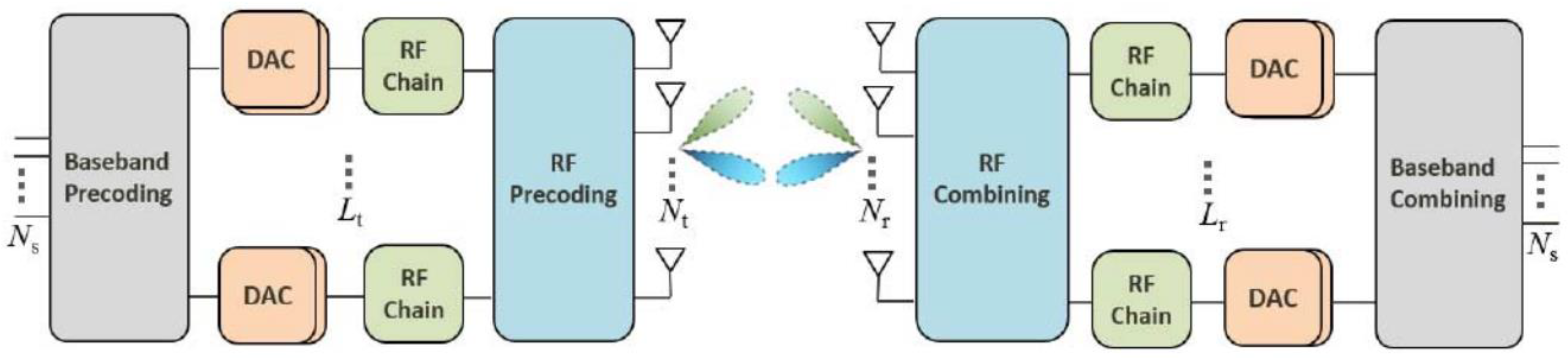

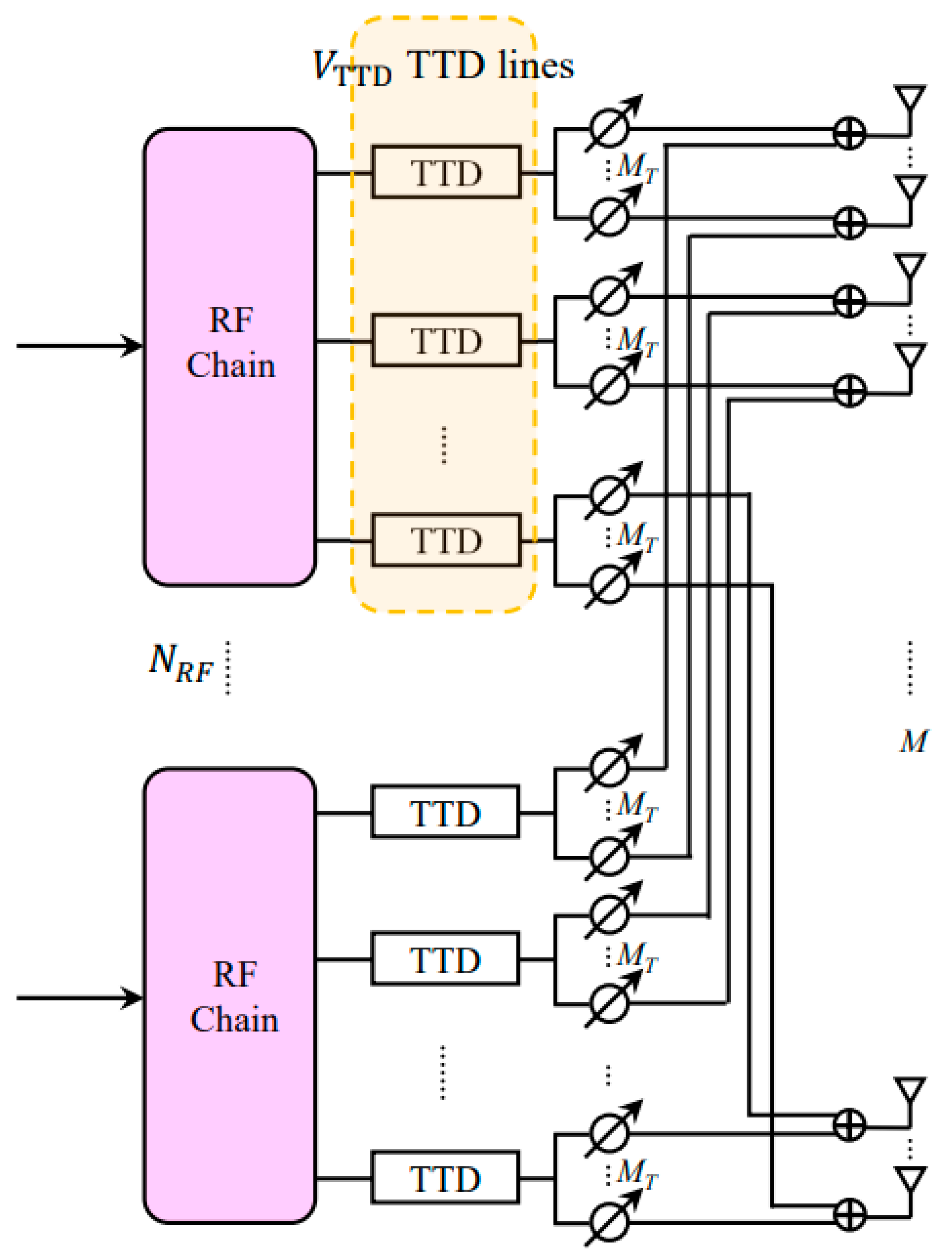

2.1.3. Hybrid Beamforming

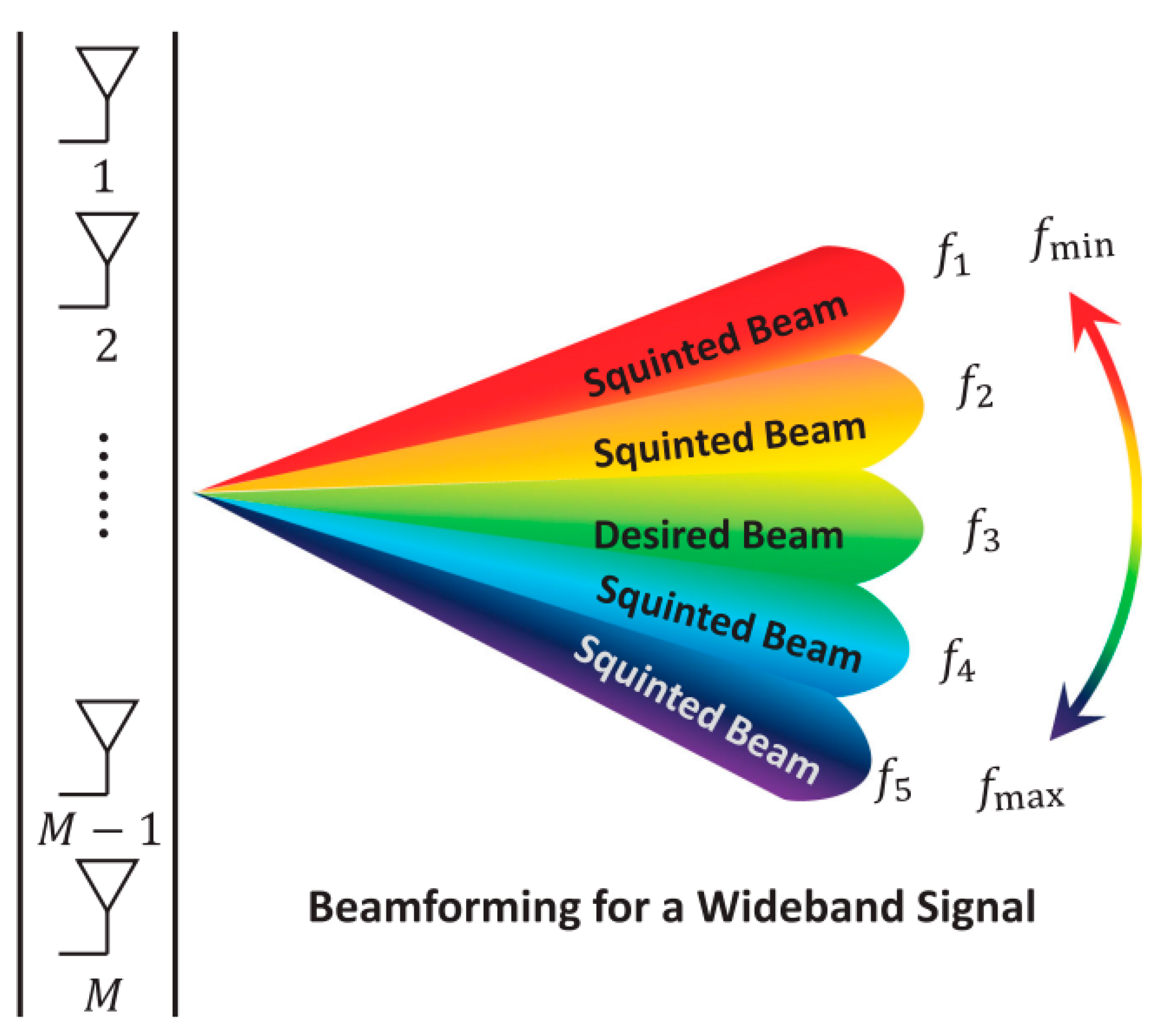

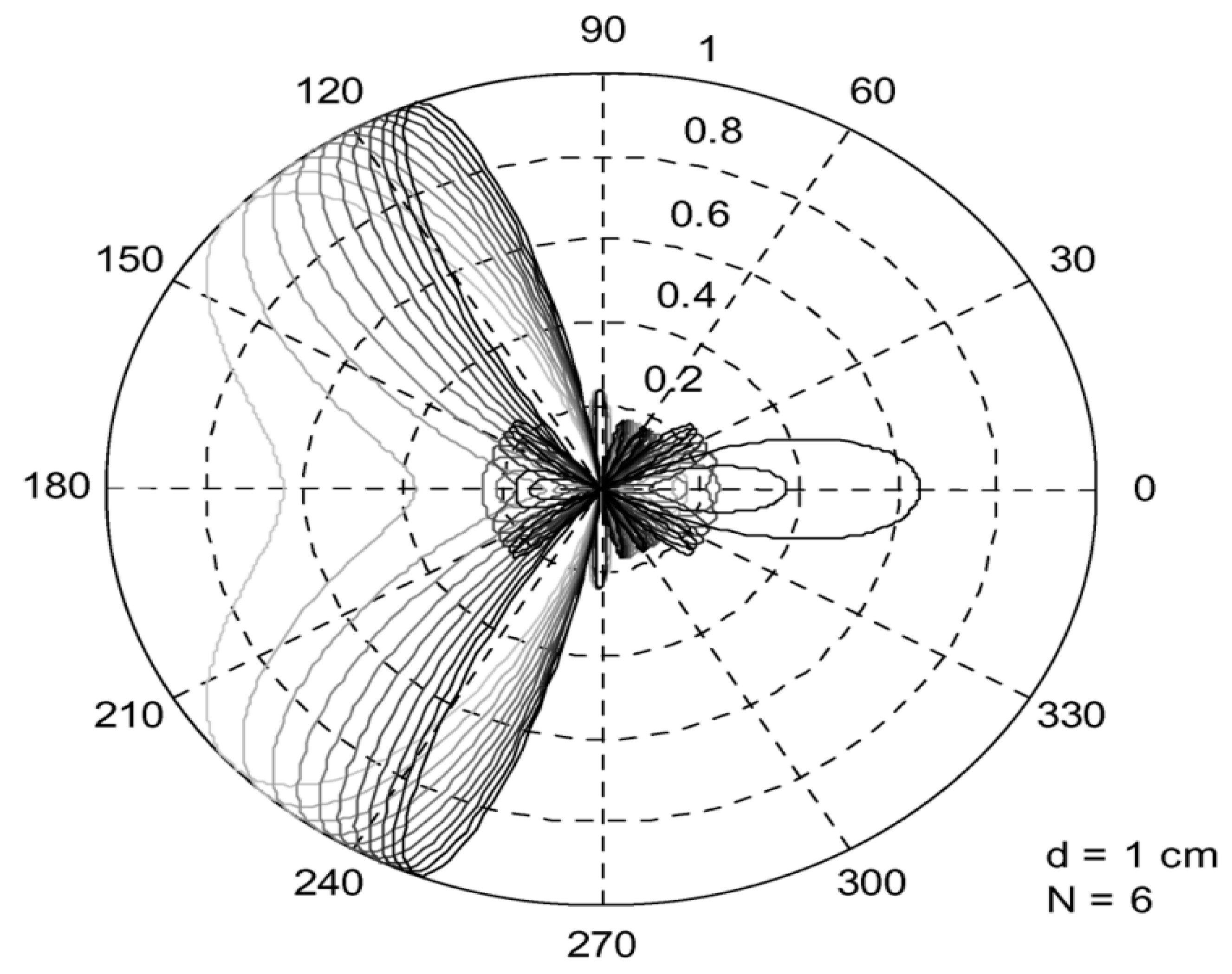

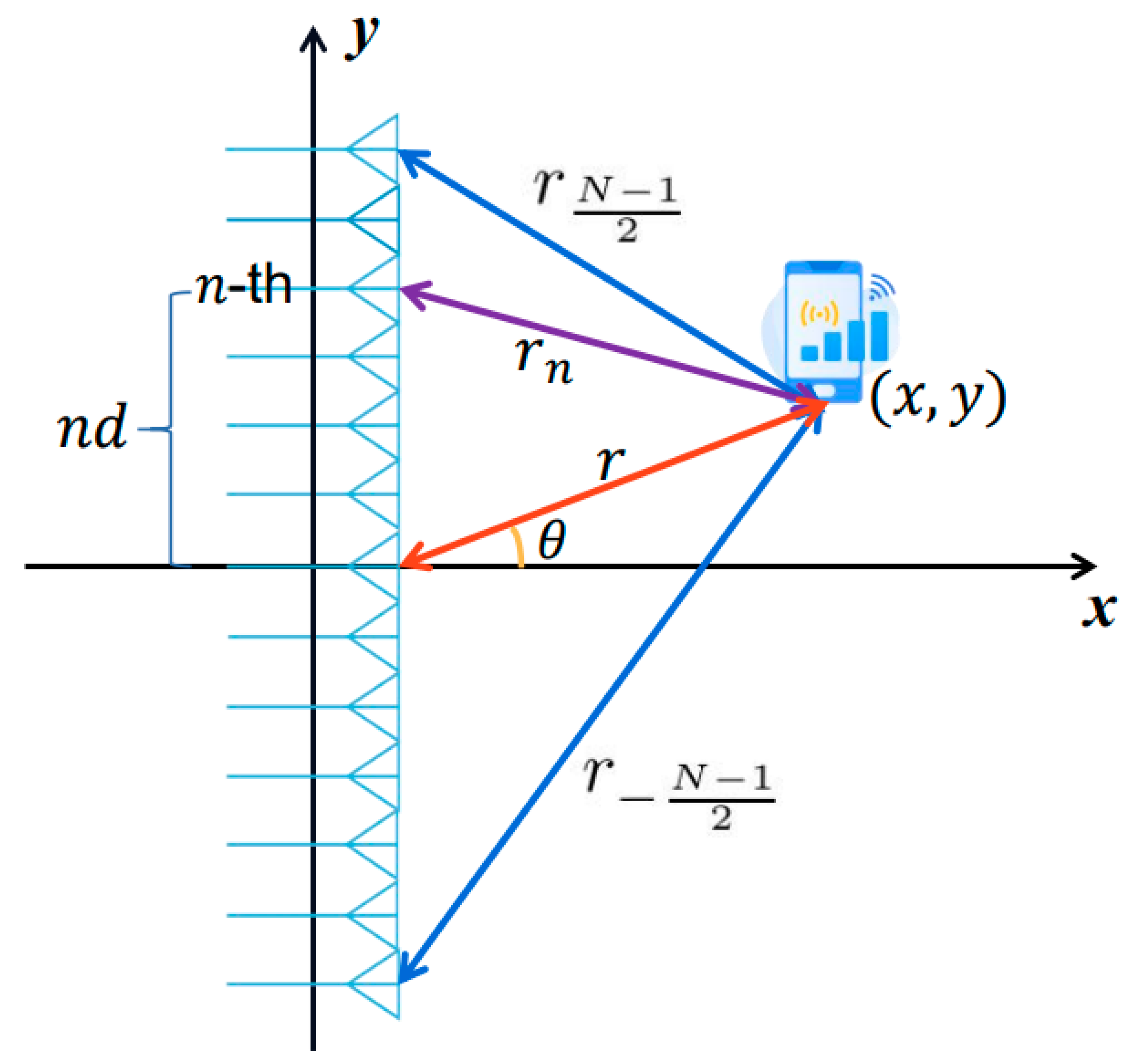

2.2. Effect of Beam Squint on the Communication System Performance

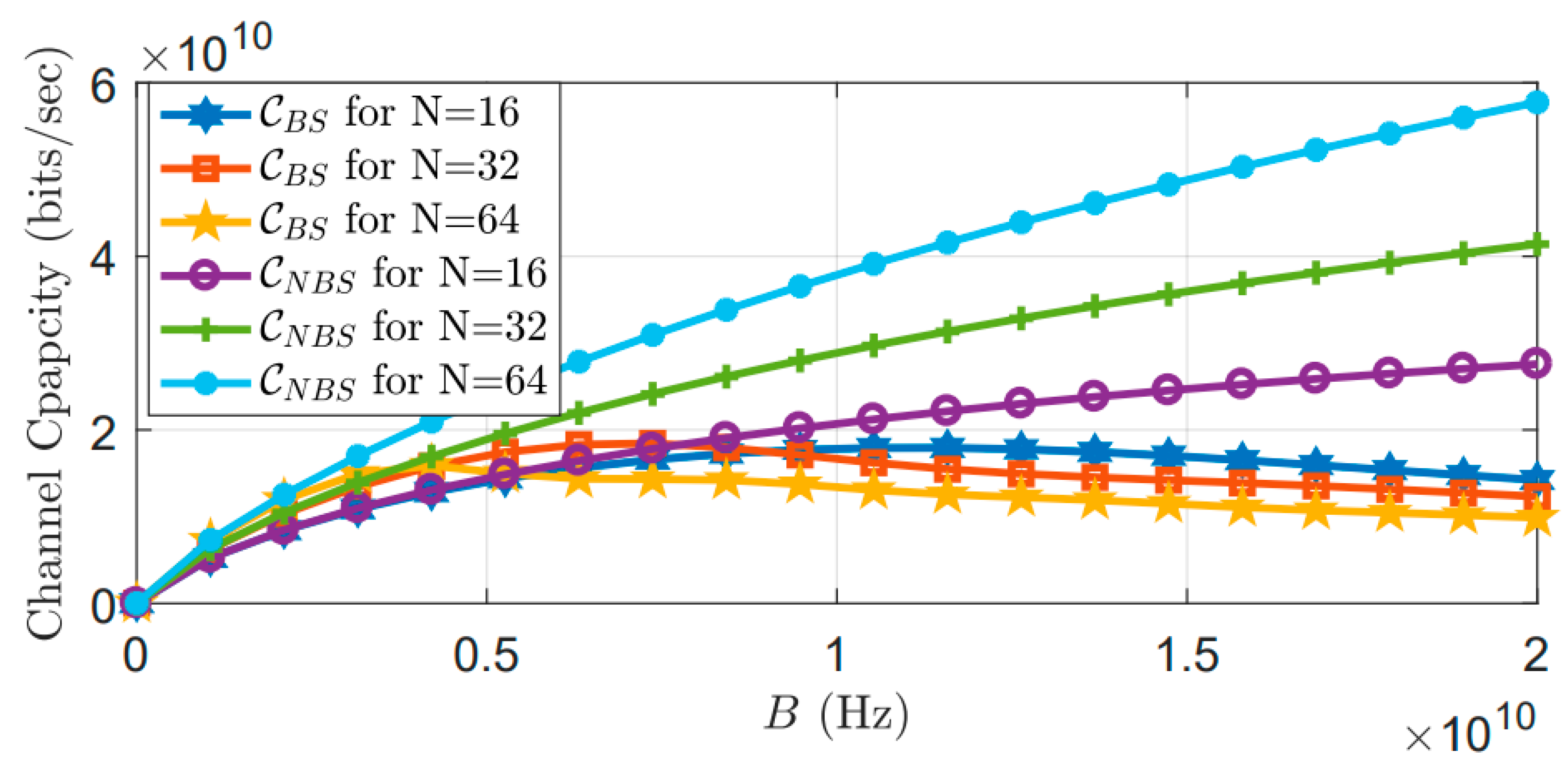

- Bandwidth and Capacity:

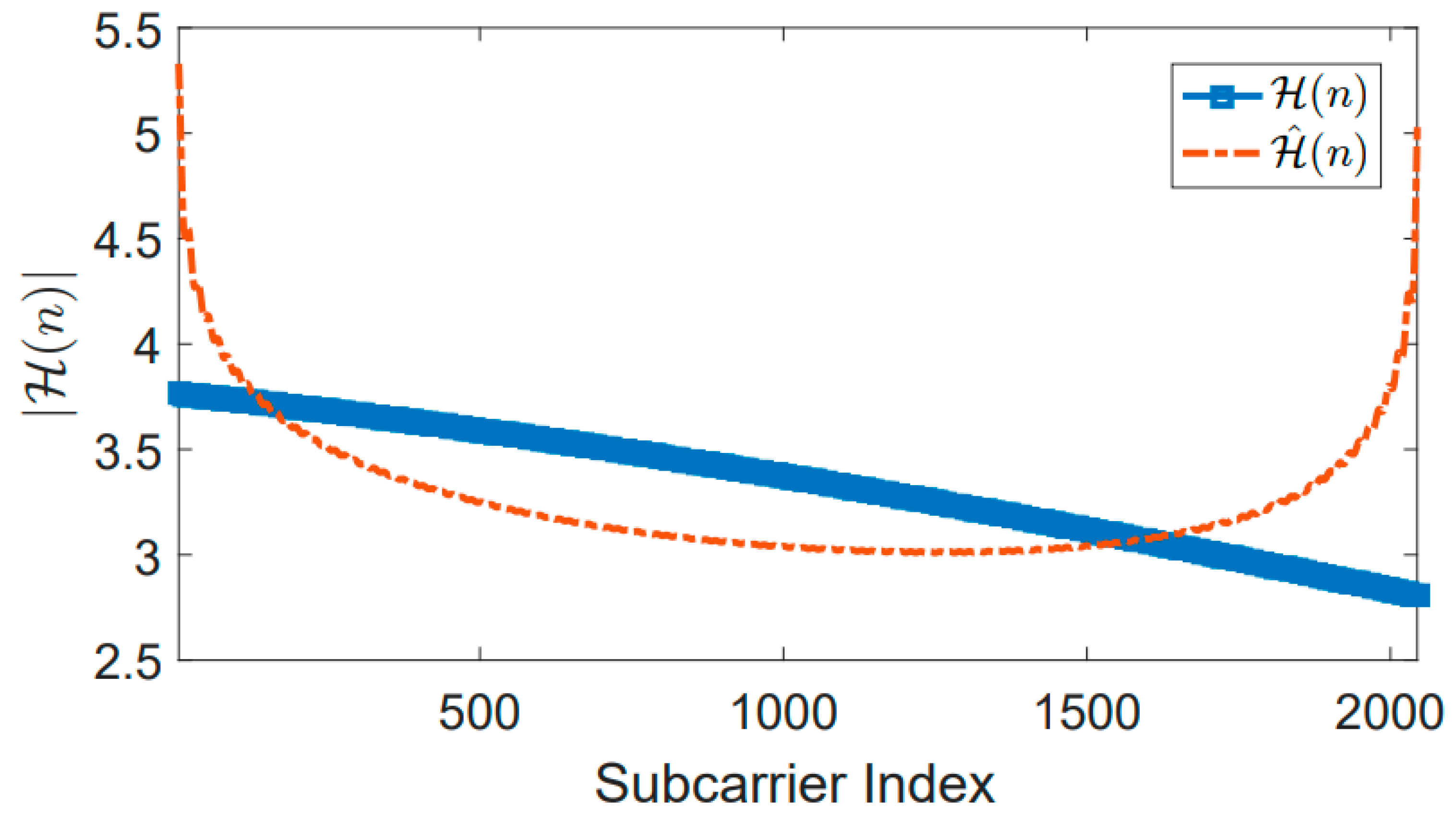

- Channel estimation:

3. Studies Related to the Beam Squint Effects

4. Studies Related to the Beam Squint Exploitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cihat, S.; Muhammet, T.; Turgut, O. A Review of Millimeter Wave Communication for 5G. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT), Ankara, Turkey, 19–21 October 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, H.; Nair, N.G.; Moore, A.; Nugent, C.; Muschamp, P.; Cuevas, M. 5G Communication: An Overview of Vehicle-to-Everything, Drones, and Healthcare Use-Cases. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 37251–37268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.; Elkashlan, M. Millimeter-wave communications for 5G: Fundamentals. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Hu, R.Q.; Qian, Y.; Wu, G. Key elements to enable millimeter wave communications for 5G wireless systems. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2014, 21, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- van Berlo, B.; Elkelany, A.; Ozcelebi, T.; Meratnia, N. Millimeter Wave Sensing: A Review of Application Pipelines and Building Blocks. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21, 10332–10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Agarwal, A.; Agarwal, K.; Mali, S.; Misran, G. Role of Millimeter Wave for Future 5G Mobile Networks: Its Po-tential, Prospects and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2021 1st Odisha International Conference on Electrical Power Engineering, Communication and Computing Technology (ODICON), Bhubaneswar, India, 8–9 January 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, T.S.; Sun, S.; Mayzus, R.; Zhao, H.; Azar, Y.; Wang, K.; Wong, G.N.; Schulz, J.K.; Samimi, M.; Gutierrez, F. Millimeter wave mobile communications for 5g cellular: It will work. Access IEEE 2013, 1, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, T.; Wang, X.; Le, L. Chapter 9–mm-Wave communication enabling techniques for 5G wireless systems: A link level perspective. Mmwave Massive MIMO 2017, 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Gao, F.; Jin, S.; Lin. An Overview of Enhanced Massive MIMO With Array Signal Processing Techniques. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2019, 13, 886–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Han, C.; Nie, S. Combating the Distance Problem in the Millimeter Wave and Terahertz Frequency Bands. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busari, S.A.; Huq, K.M.S.; Mumtaz, S.; Dai, L.; Rodriguez, J. Millimeter-Wave Massive MIMO Communication for Future Wireless Systems: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2017, 20, 836–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarieddeen, H.; Saeed, N.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y.; Alouini, M.-S. Next Generation Terahertz Communications: A Rendezvous of Sensing, Imaging, and Localization. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadoon, M.; Patwary, M.; Parchin, N.; Aldelemy, A.; Abd-Alhameed, R. New Beamforming Ap-proach Using 60 GHz Antenna Arrays for Multi-Beams 5G Applications. Electronics 2022, 11, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Mumtaz, S.; Huang, Y.; Dai, L.; Li, Y.; Matthaiou, M.; Karagiannidis, G.K.; Bjornson, E.; Yang, K.; Chih-Lin, I.; et al. Millimeter Wave Communications for Future Mobile Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2017, 35, 1909–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Valenzuela, R.A. How Much Spectrum is too Much in Millimeter Wave Wireless Access. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2017, 35, 1444–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.G.; Buzzi, S.; Choi, W.; Hanly, S.V.; Lozano, A.; Soong, A.C.K.; Zhang, J.C. What will 5G be? IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2014, 32, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.G.; Bai, T.; Kulkarni, M.N.; Alkhateeb, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Heath, R.W. Modeling and Analyzing Millimeter Wave Cellular Systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2016, 65, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindlehurst, A.L.; Ayanoglu, E.; Heydari, P.; Capolino, F. Millimeter-wave massive MIMO: The next wireless revolution? IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Li, Y.; Jin, D.; Su, L.; Chen, S. Millimeter-wave backhaul for 5G networks: Challenges and solutions. Sensors 2016, 16, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Niu, Y.; Wu, H.; Ai, B.; Chen, S.; Feng, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, N. Mobility Support for Millimeter Wave Communications: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2022, 24, 1816–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugno, T.; Drago, M.; Giordani, M.; Polese, M.; Zorzi, M. Toward standardization of millimeter-wave vehicle-tovehicle networks: Open challenges and performance evaluation. IEEE Communi. Mag. 2020, 58, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutty, S.; Sen, D. Beamforming for Millimeter Wave Communications: An Inclusive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2015, 18, 949–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornson, E.; Van der Perre, L.; Buzzi, S.; Larsson, E.G. Massive MIMO in sub-6 GHz and mm-Wave: Physical, practical, and use-case differences. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandloi, M.S.; Gupta, P.; Parmar, A.; Malviya, P.; Malviya, L. Beamforming MIMO Array Antenna for 5G-Millimeter-Wave Application. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, J.S.; Conway, M.D. The Evolution to Modern Phased Array Architectures. Proc. IEEE 2015, 104, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.C.; Maksymyuk, T.; de Almeida, A.L.; Maciel, T.; Mota, J.C.; Jo, M. Massive MIMO: Survey and future research topics. IET Commun. 2016, 10, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, T.E.; Le, L.B.; Haghighat, A.; Vandendorpe, L. On the Number of RF Chains and Phase Shifters, and Scheduling Design with Hybrid Analog–Digital Beamforming. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2010, 15, 3311–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, M.V.; van der Veen, A. Analog Beamforming in MIMO Communications with Phase Shift Networks and Online Channel Estimation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2010, 58, 4131–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyskal, H. Digital beamforming. In Proceedings of the 1988 18th European Microwave Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 12–15 September 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.W.; González-Prelcic, N.; Rangan, S.; Roh, W.; Sayeed, A.M. An Overview of Signal Processing Techniques for Millimeter Wave MIMO Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2016, 10, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan; Dudgeon, E.; Johnson, D.H. Array Signal Processing: Concepts and Techniques; P T R Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi, F.; Yu, W. Hybrid Analog and Digital Beamforming for mmWave OFDM Large-Scale Antenna Arrays. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2017, 35, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Huang, K.; Lau, V.K.N.; Xia, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. Hybrid Beamforming via the Kronecker Decomposition for the Millimeter-Wave Massive MIMO Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2017, 35, 2097–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherekhloo, S.; Ardah, K.; Haardt, M. Hybrid Beamforming Design for Downlink MU-MIMO-OFDM Millimeter-Wave Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 11th Sensor Array and Multichannel Signal Processing Workshop (SAM), Hangzhou, China, 8–11 June 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.; Pi, Z.; Rajagopal, S. Millimeter-wave mobile broadband with large scale spatial processing for 5G mobile com-munication. In Proceedings of the 2012 50th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton), Monticello, IL, USA, 1–5 October 2012; pp. 1517–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Letaief, K.B. Hybrid Beamforming for 5G and Beyond Millimeter-Wave Systems: A Holistic View. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2019, 1, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Laneman, J.N.; Hochwald, B. Beamforming codebook compensation for beam squint with channel capacity con-straint. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Aachen, Germany, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

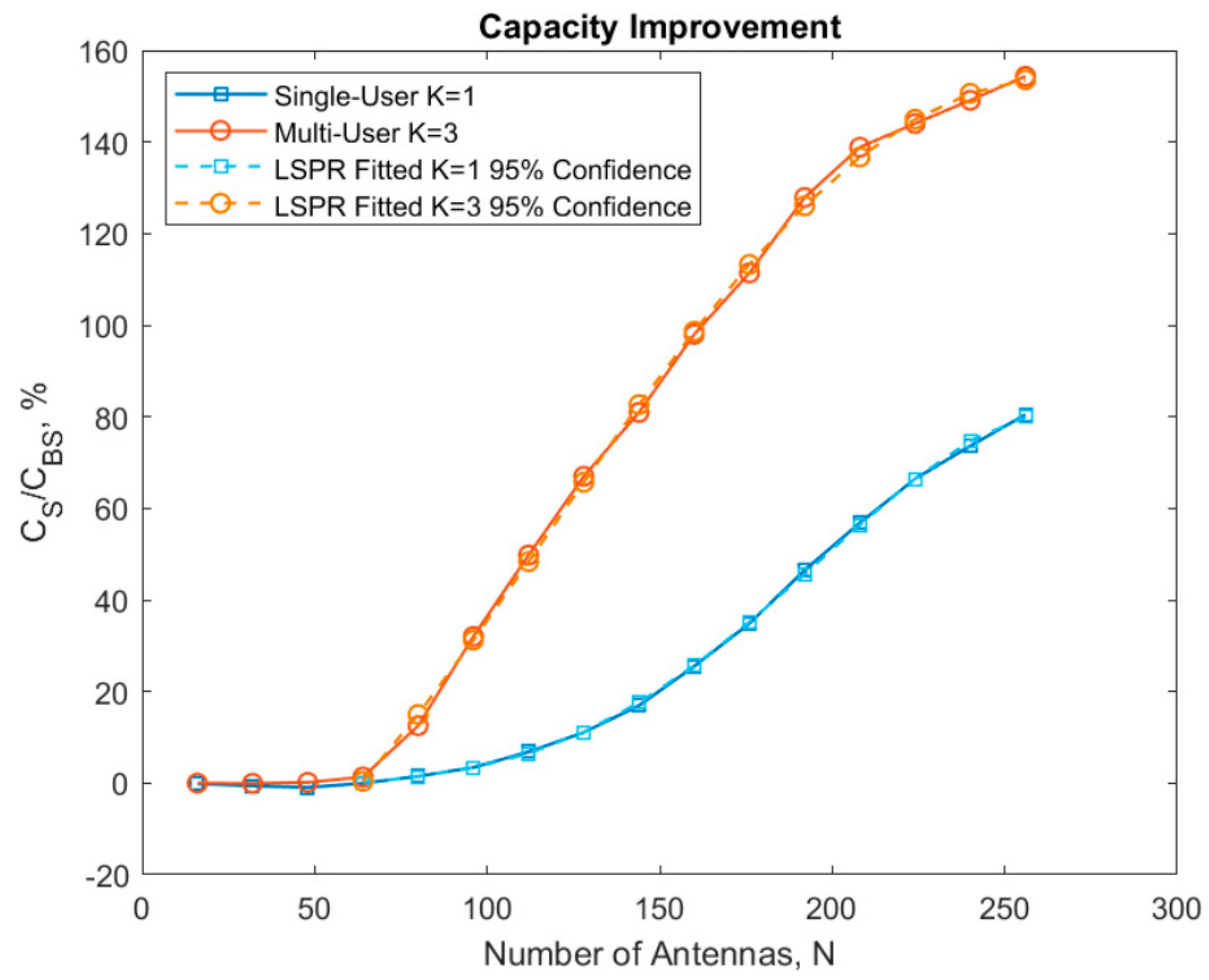

- Pan, X.; Li, C.; Yang, L. Wideband beamspace squint user grouping algorithm based on subarray collaboration. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2022, 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.analog.com/en/analog-dialogue/articles/phased-array-antenna-patterns-part2.html (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Yao, J. Microwave Photonics. J. Light. Technol. 2009, 27, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, R.; Singleton, M.; Leuchtmann, P.; Leuthold, J. Comparison of steering angle and bandwidth for various phased array antenna concepts. Opt. Commun. 2016, 373, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Modeling and Mitigating Beam Squint in Millimeter Wave Wireless Communication. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate Program in Electrical Engineering, Notre Dame, Indiana, March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseaux, O.; Leus, G.; Stoica, P.; Moonen, M. Gaussian maximum-likelihood channel estimation with short training se-quences. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2005, 4, 2945–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targonski, S.; Pozar, D. Minimization of beam squint in microstrip reflectarrays using an offset feed. In Proceedings of the IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium. 1996 Digest, Baltimore, MD, USA, 21–26 July 1996; Volume 2, pp. 1326–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.B.; Pujara, D.A.; Chakrabarty, S.B.; Singh, V.K. Removal of Beam Squinting Effects in a Circularly Polarized Offset Parabolic Reflector Antenna Using a Matched Feed. Prog. Electromagn. Res. Lett. 2009, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garakoui, S.K.; Klumperink, E.A.M.; Nauta, B.; van Vliet, F.E. Phased-array antenna beam squinting related to frequency dependency of delay circuits. In Proceedings of the 2011 41st European Microwave Conference, Manchester, UK, 10–13 October 2011; pp. 1304–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Longbrake, M. True time-delay beam steering for radar. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference (NAECON), Dayton, OH, USA, 25–27 July 2012; pp. 246–249. [Google Scholar]

- Alomar, W.; Mortazawi, A. Elimination of beam squint in uniformly excited serially fed antenna arrays using negative group delay circuits. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation, Chicago, IL, USA, 8–14 July 2012; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Brilloun, L.; Sommerfeld, A. Wave Propagation and Group Velocity; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; pp. 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Rehman, W.U.; Xu, X.; Tao, X. Minimize Beam Squint Solutions for 60GHz Millimeter-Wave Communication System. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 78th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Fall), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2–5 September 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, M.; Gao, K.; Nie, D.; Hochwald, B.; Laneman, J.N.; Huang, H.; Liu, K. Effect of Wideband Beam Squint on Codebook Design in Phased-Array Wireless Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Qiao, D. Space-Time Block Coding-Based Beamforming for Beam Squint Compensation. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 8, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurinavicius, I.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y. Beam Squint Exploitation for Linear Phased Arrays in a mmWave Multi-Carrier System. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Jian, M.; Gao, F.; Li, G.Y.; Lin, H. Beam Squint and Channel Estimation for Wideband mmWave Massive MIMO-OFDM Systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2019, 67, 5893–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, F.; Gu, Y.; Flanagan, M.F. A Block Sparsity Based Channel Estimation Technique for mmWave Massive MIMO with Beam Squint Effect. In Proceedings of the ICC 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Shanghai, China, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Longman, O.; Solodky, G.; Bilik, I. Beam Squint Correction for Phased Array Antennas Using the Tansec Waveform. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Radar Conference (RADAR), Washington, DC, USA, 28–30 April 2020; pp. 489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, S.; Lee, J.; Yu, H.; Song, J. Design of Channel Estimation for Hybrid Beamforming Millimeter-Wave Systems in the Presence of Beam Squint. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 16, 2834–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Jiang, T. Beam-Squint Mitigating in Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface Aided Wideband MmWave Communications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Nanjing, China, 29 March–1 April 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liaskos, C.; Nie, S.; Tsioliaridou, A.; Pitsillides, A.; Ioannidis, S.; Akyildiz, I. A New Wireless Communication Paradigm through Software-Controlled Metasurfaces. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wang, B.; Xing, C.; An, J.; Li, G.Y. Wideband Beamforming for Hybrid Massive MIMO Terahertz Communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 1725–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yue, G. Beam squint effect on high-throughput millimeter-wave communication with an ul-tra-massive phased array. Front. Inform. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2021, 22, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Kim, B.; Kim, D.K.; Dai, L.; Wong, K.-K.; Chae, C.-B. Beam Squint in Ultra-wideband mm-Wave Systems: RF Lens Array vs. Phase-Shifter-Based Array. arxiv 2021, arXiv:2112.04188. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentz, H.A. The Theory of Electrons: And Its Applications to the Phenomena of Light and Radiant Heat; Wentworth Press: Sydney, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Afeef, L.; Kihero, A.B.; Arslan, H. Novel Transceiver Design in Wideband Massive MIMO for Beam Squint Minimization. arxiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04679. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Niu, H.; An, K.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Chatzinotas, S.; Hu, Y. Refracting RIS-Aided Hybrid Satellite-Terrestrial Relay Networks: Joint Beamforming Design and Optimization. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 3717–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Li, C.; Hua, M.; Yan, W.; Yang, L. Compact Multi-Wideband Array for Millimeter-Wave Communications Using Squint Beams. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183146–183164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lin, M.; Wang, J.B.; de Cola, T.; Wang, J. Joint Beamforming and Power Allocation for Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks with Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2019, 3, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Gao, F. Beam Squint Assisted User Localization in Near-Field Communications Systems. Arvix 2022, arXiv:2205.11392. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Digital Beamforming | Analog Beamforming | Codebook Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity | High complexity | Acceptable complexity | Increases the number of phase shifters, which increases the complexity |

| Cost | Increased hardware requirements lead to a high cost | Compared with their digital counterparts, the costs are much lower | Power and cost rose significantly |

| Effectiveness | Incredibly efficient at correcting the squint | Has the potential to decrease the effect of squinting and improve efficiency | Able to significantly lessen the “squint” effect |

| Ref. | Year | Method | Results | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | 2012 | TTD instead of phase shifters | TDD provided good result in overcoming beam squint | Increasing complexity and cost |

| [47] | 2012 | Negative Group Delay Circuits | Reduced the beam squint | Hardware complexity |

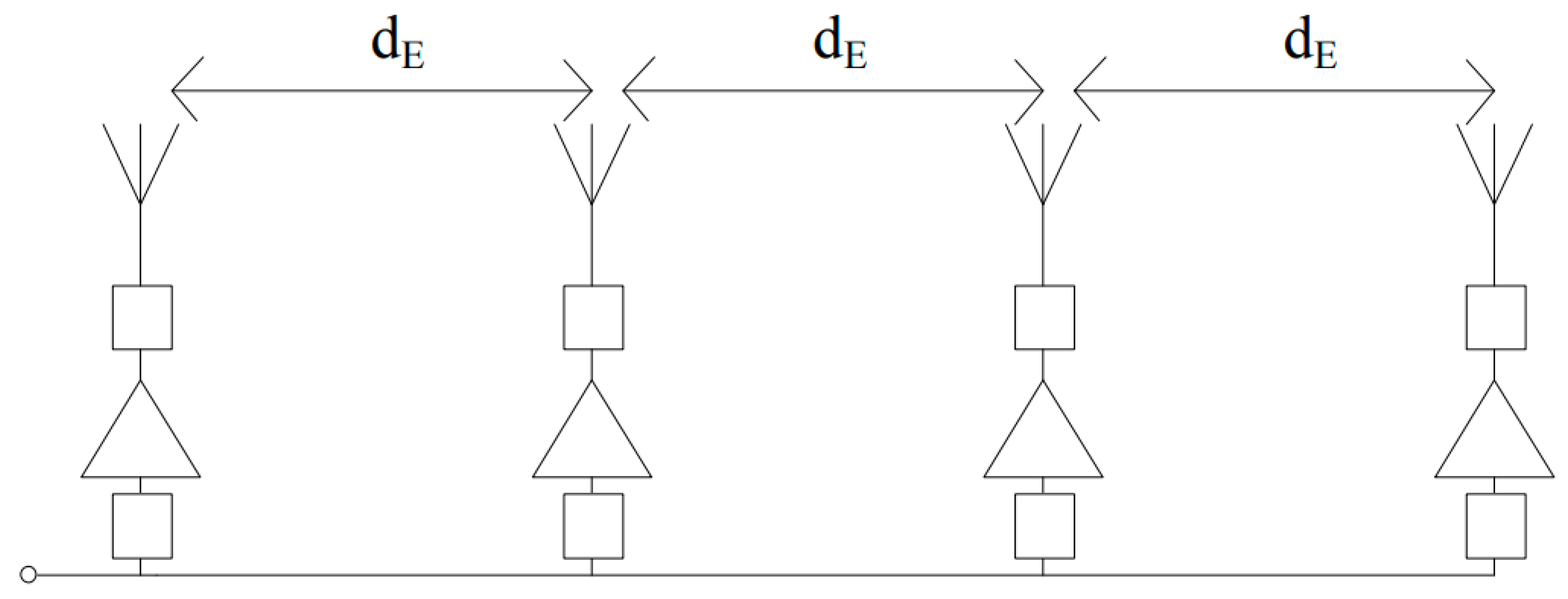

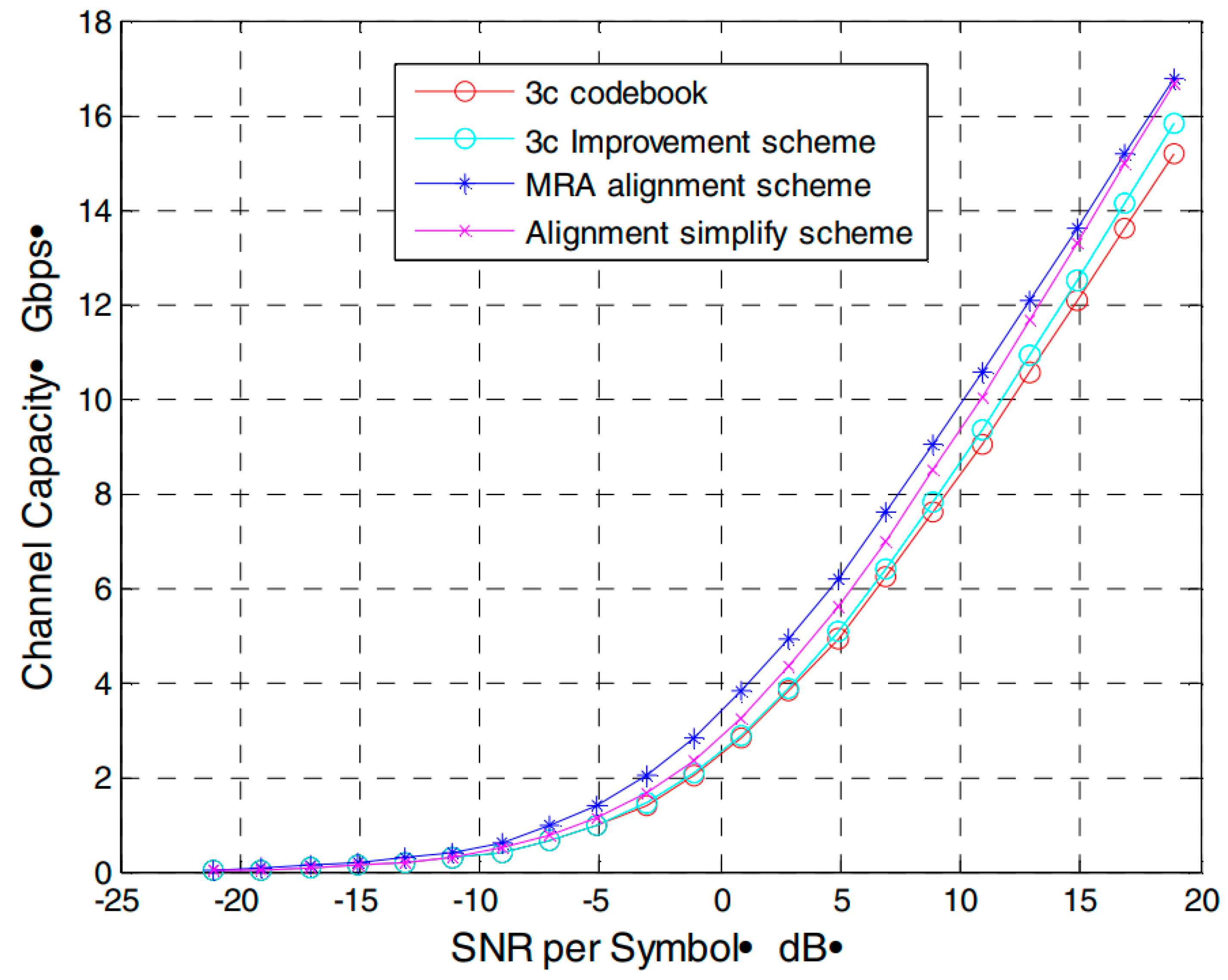

| [49] | 2013 | Three beamforming codebook design schemes | Reduced the beam squint | Increases the number of phase shifters, which increases power usage and complexity |

| [50] | 2016 | Algorithm that ensures minimum gain for all frequencies and angles | Reduced the beam squint | Greatly increases the size of codebook, which leads to high latency |

| [51] | 2018 | Alamuti-based beamforming scheme | May successfully fix the beam squint and increase throughput performance. | Proposed beam pattern optimization involves eigenvalue and -vector computation, the computation complexity of this scheme grows with the number of antennas |

| [52] | 2019 | Proposed subcarrier-to-beam allocation scheme | Exploited beam squint to enhance system performance | Hardware complexity since it is applied in digital domain |

| [53] | 2019 | Frequency-division duplex (FDD) massive MIMO-OFDM systems with hybrid analog/digital precoding using a channel estimation scheme | Provided more accurate channel estimation than other conventual methods | The assignment of pilot subcarriers and the design of training beams were not considered |

| [54] | 2019 | Shift-invariant block-sparsity-based compression sensing (CS) algorithm | Provided more accurate channel estimation than other conventual methods | - |

| [55] | 2020 | Tansec waveform with nonlinear frequency modulation to account for carrier frequency variation | Beam direction error was reduced | Implemented in digital domain which increase complexity |

| [56] | 2021 | Algorithm for channel estimation using the greatest likelihood criterion in relation to the analog training beam and pilot subcarrier assignment | The proposed algorithm minimized the mean square error | - |

| [57] | 2021 | For RIS-aided wideband (mmwave) communications, phase shift design approaches are used to reduce the impact of beam squint in both LoS and NLoS scenarios | Beam squint in such systems was effectively reduced by the proposed phase shift architecture | - |

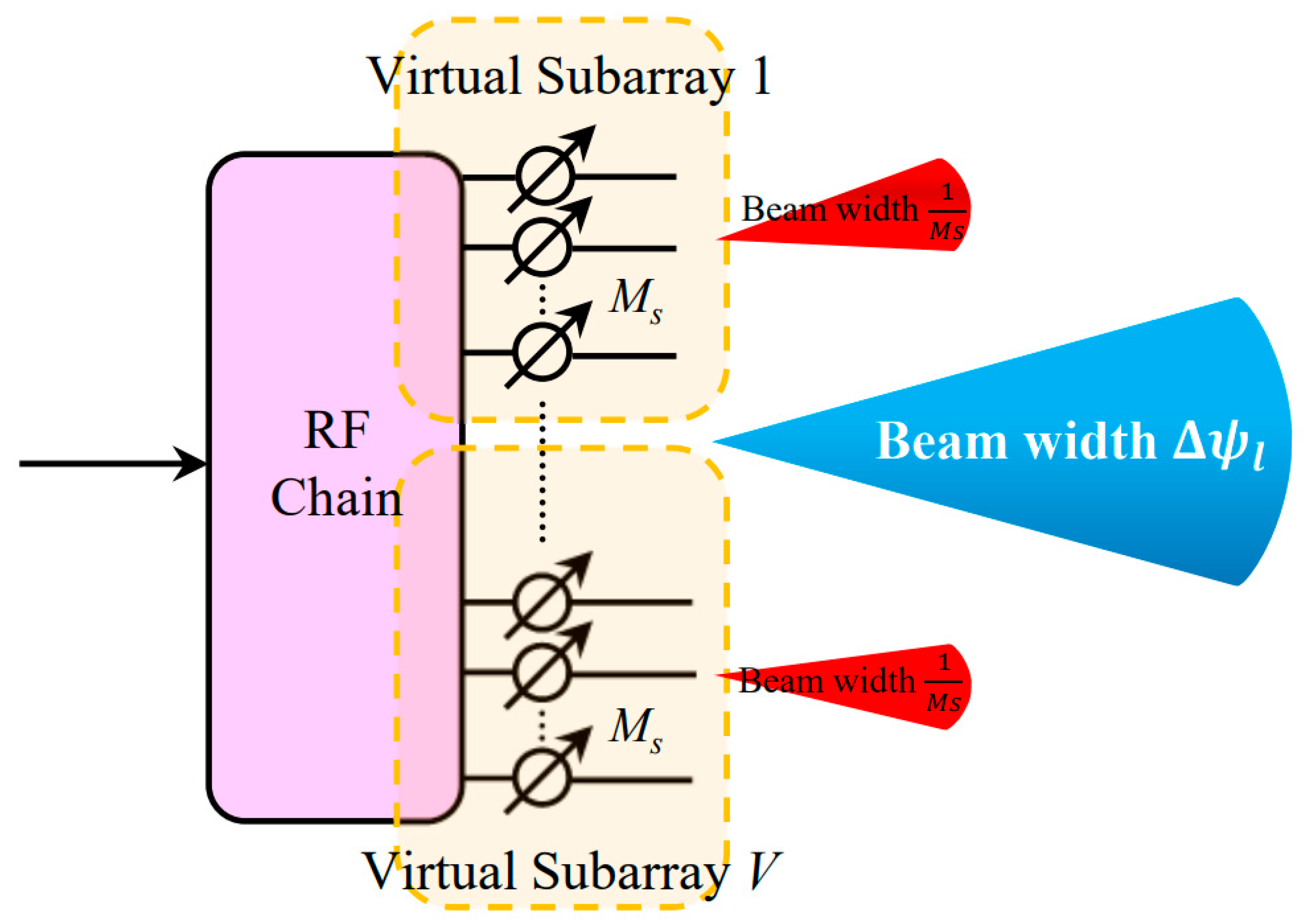

| [59] | 2021 | Virtual subarrays and TDD lines | Effective in removing beam squint | Increasing hardware complexity |

| [60] | 2021 | Advanced analog beamforming method proposed based on the Zadoff-Chu (ZC) sequence | The performance loss caused by the beam squint can be efficiently reduced using the suggested strategy | - |

| [61] | 2021 | Three-dimensional electromagnetic analysis software | Clarify how beam squint occurred in RF lens antenna and compare its effect with phased array antenna | - |

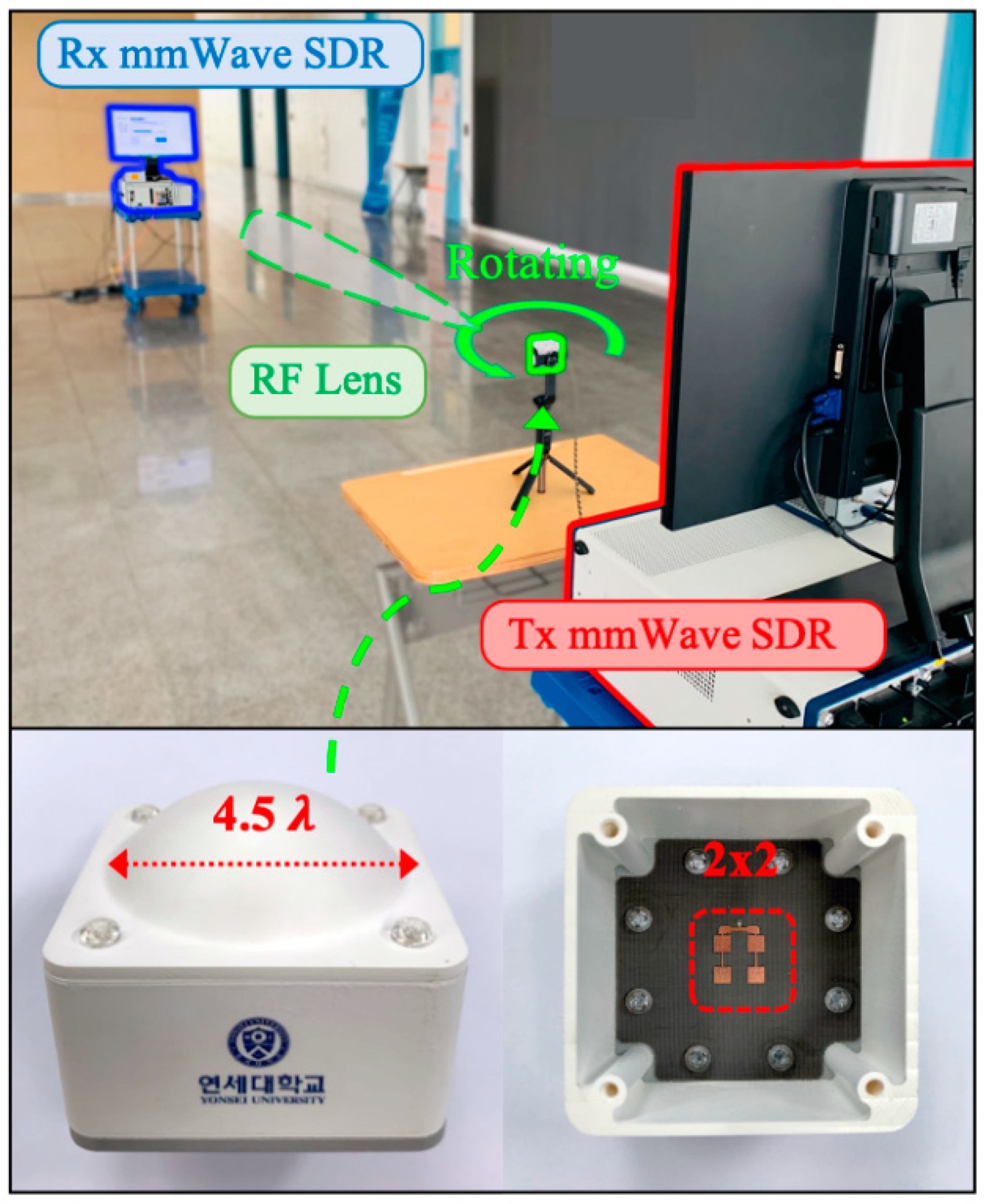

| [63] | 2022 | Transceiver design based on lens antenna subarray (LAS) and analog sub band filters | Results showed performance enhancement | Higher frequencies require high quality filters which increase hardware complexity |

| [65] | 2020 | Create multi-user communication plans that make use of squinting multi-beam properties and small multi-wideband antenna arrays | Effective method to exploit beam squint with multi-user systems | Squint-beam-based compact multi-wideband array for millimeter-wave communications |

| [67] | 2022 | Control the beam squint using time delays and using it for localization | Effective method to exploit beam squint in localization | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdalrazak, M.Q.; Majeed, A.H.; Abd-Alhameed, R.A. A Critical Examination of the Beam-Squinting Effect in Broadband Mobile Communication: Review Paper. Electronics 2023, 12, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12020400

Abdalrazak MQ, Majeed AH, Abd-Alhameed RA. A Critical Examination of the Beam-Squinting Effect in Broadband Mobile Communication: Review Paper. Electronics. 2023; 12(2):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12020400

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdalrazak, Mariam Q., Asmaa H. Majeed, and Raed A. Abd-Alhameed. 2023. "A Critical Examination of the Beam-Squinting Effect in Broadband Mobile Communication: Review Paper" Electronics 12, no. 2: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12020400

APA StyleAbdalrazak, M. Q., Majeed, A. H., & Abd-Alhameed, R. A. (2023). A Critical Examination of the Beam-Squinting Effect in Broadband Mobile Communication: Review Paper. Electronics, 12(2), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12020400