Design and Implementation Procedure of a High-Gain Three-Input Step-Up 1 kW Converter

Abstract

1. Introduction

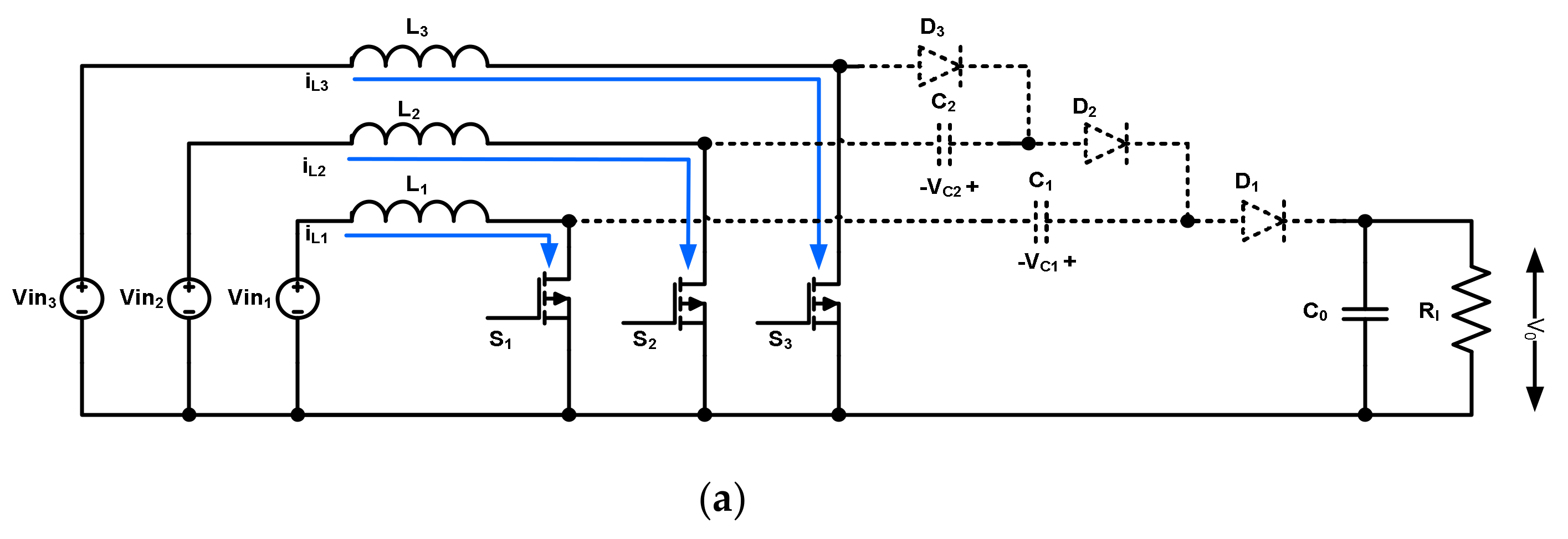

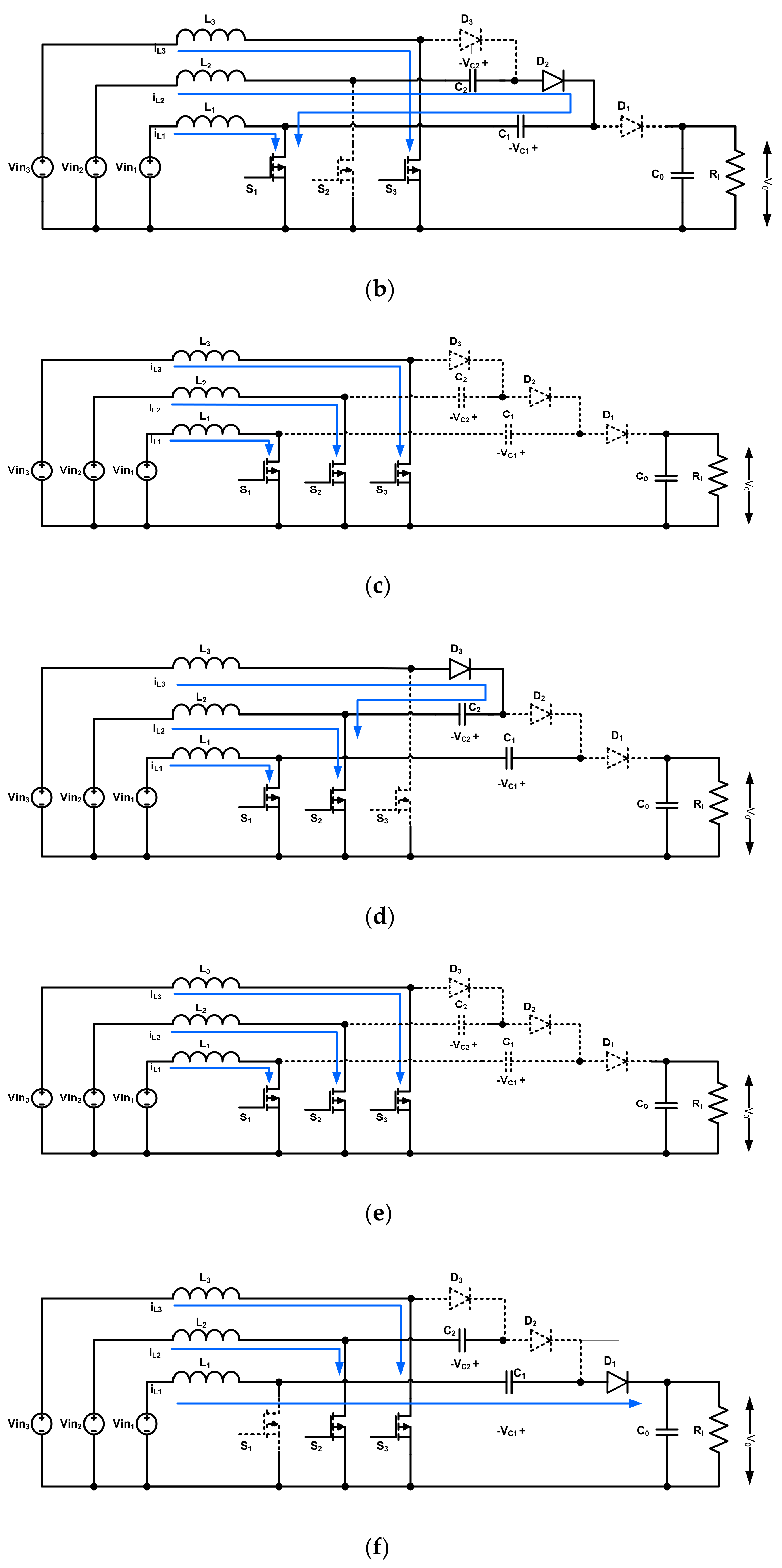

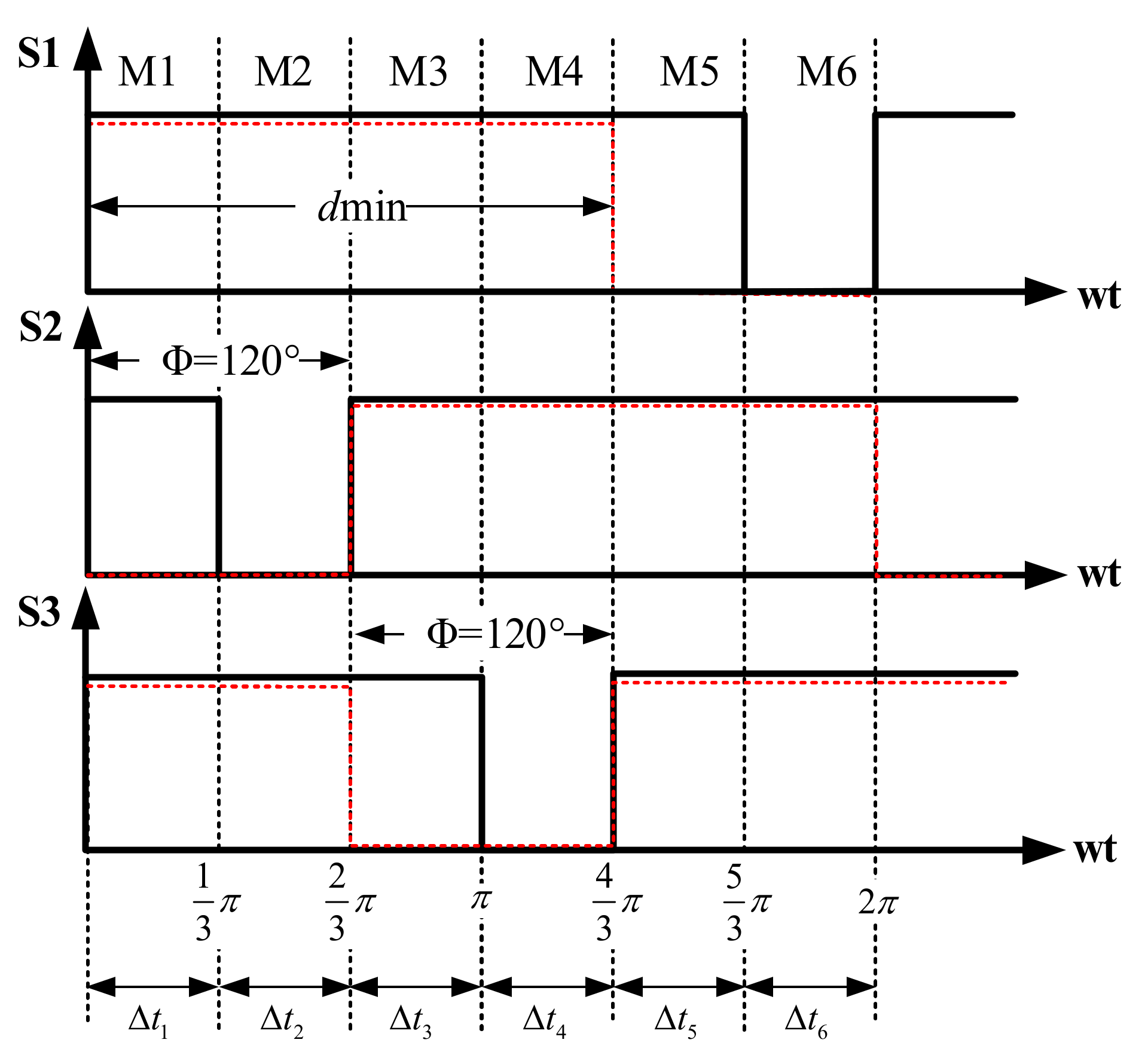

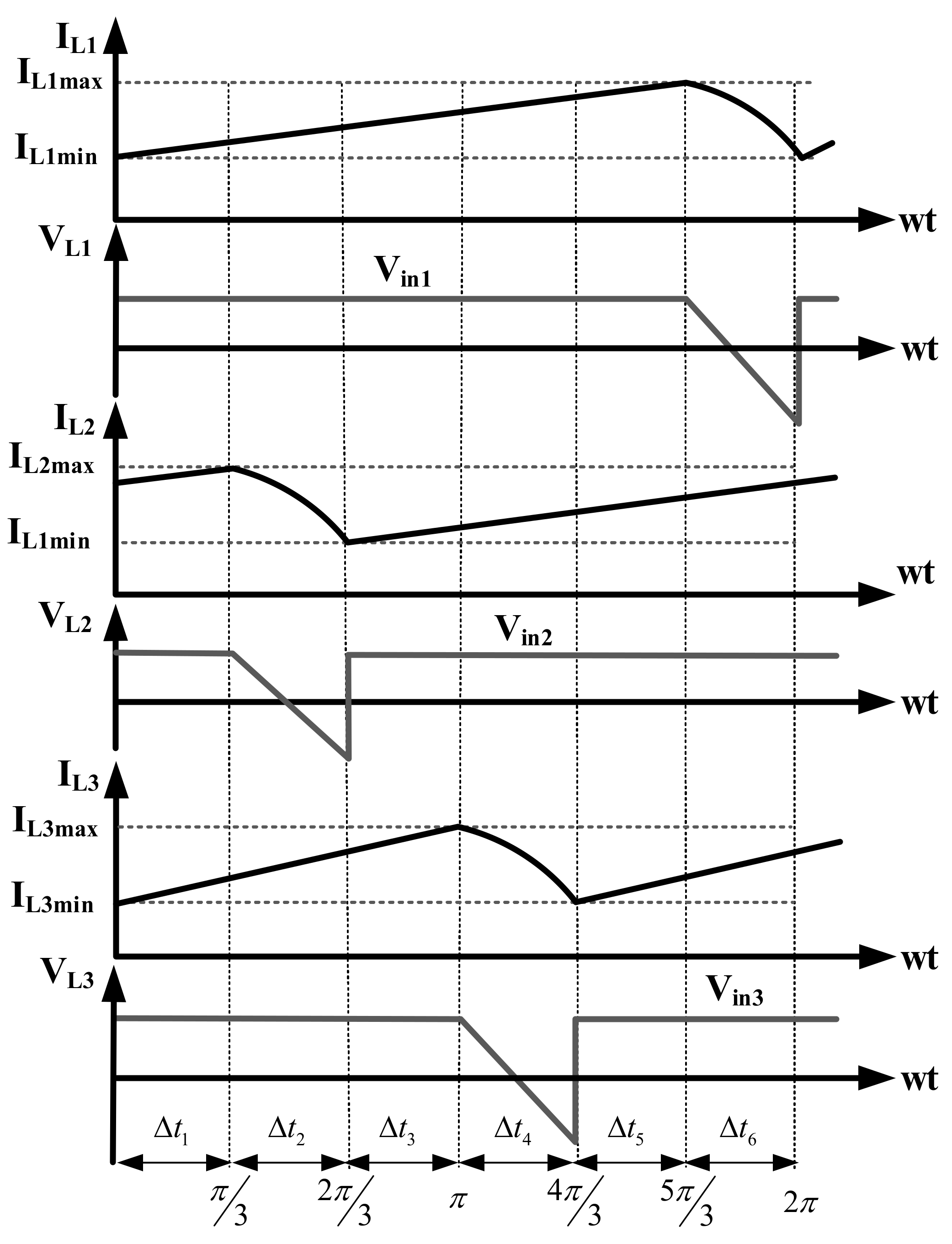

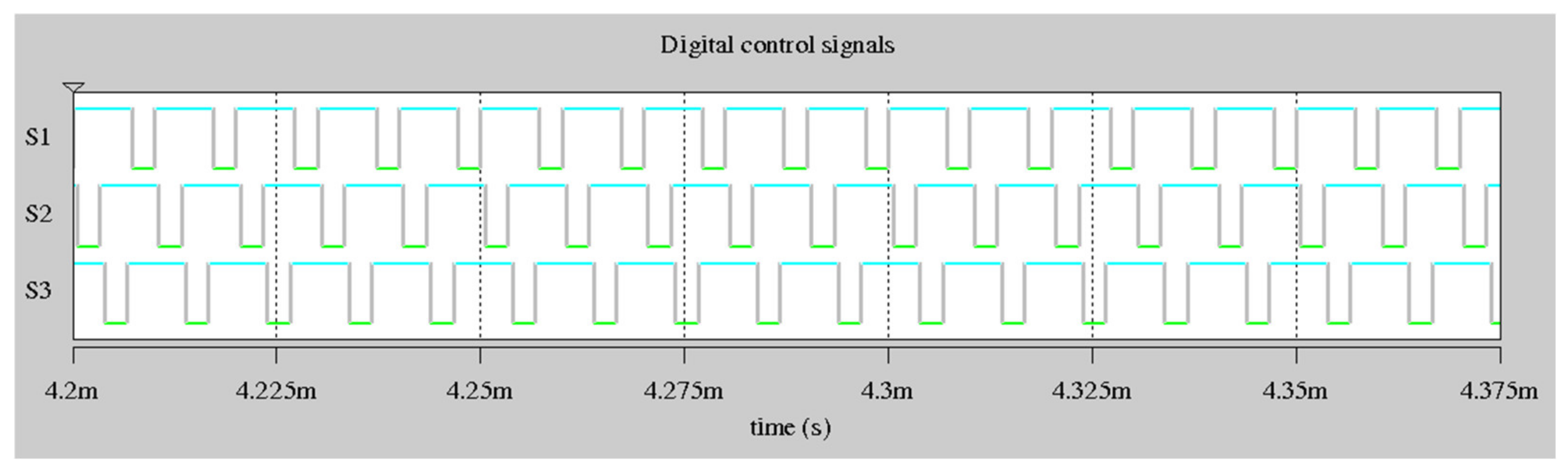

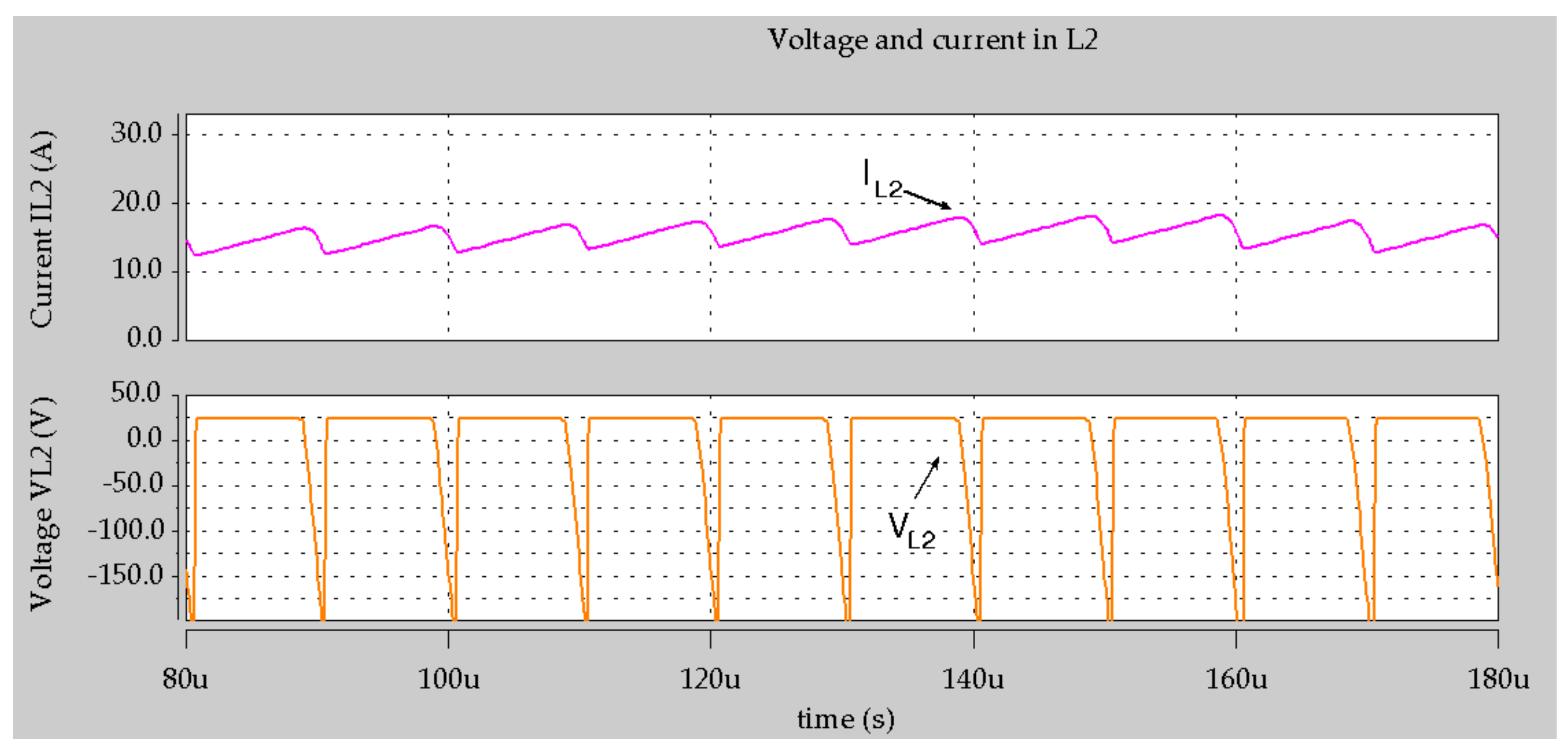

2. Principle of Operation

Model Based on a State Variable Equations

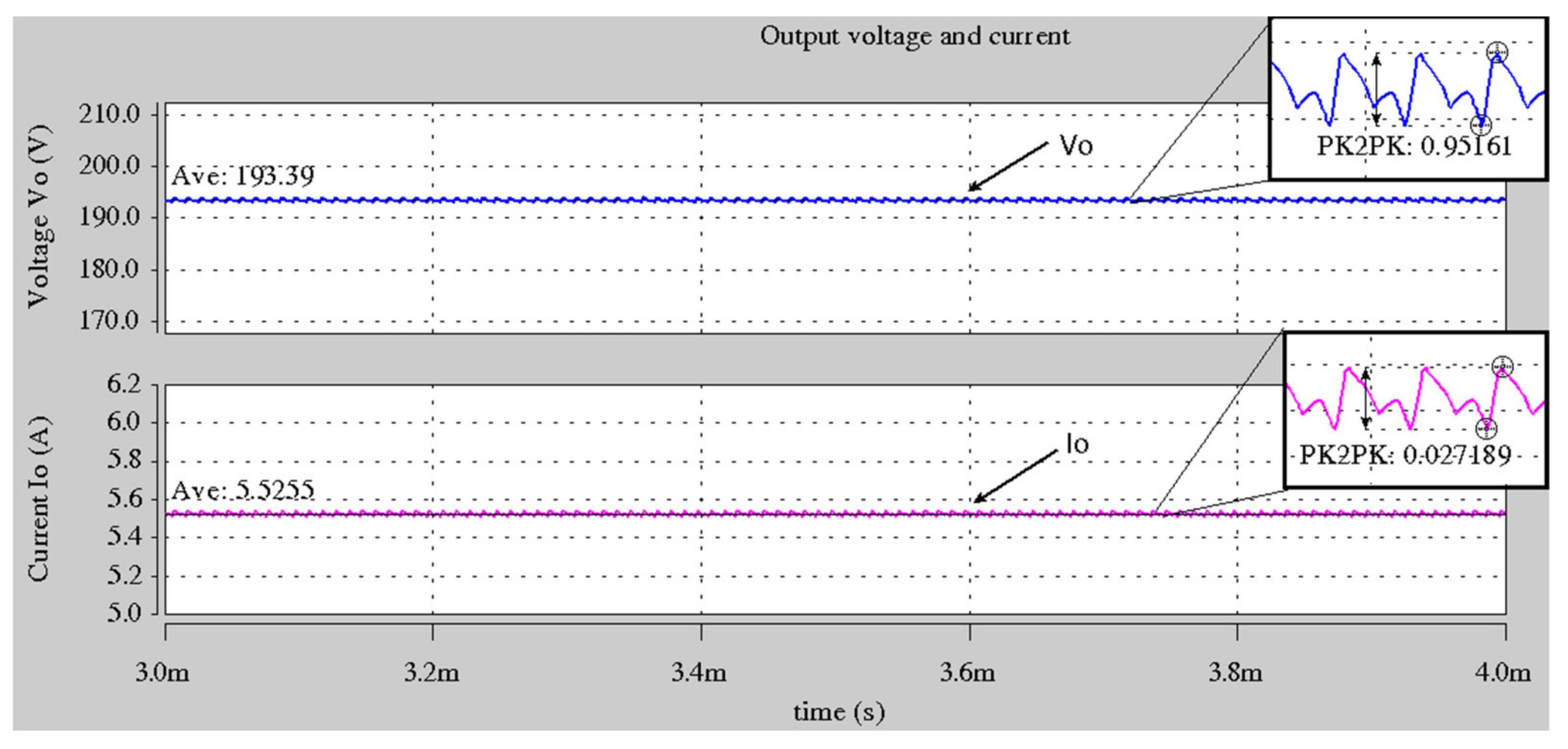

3. Design Procedure and Simulation Results

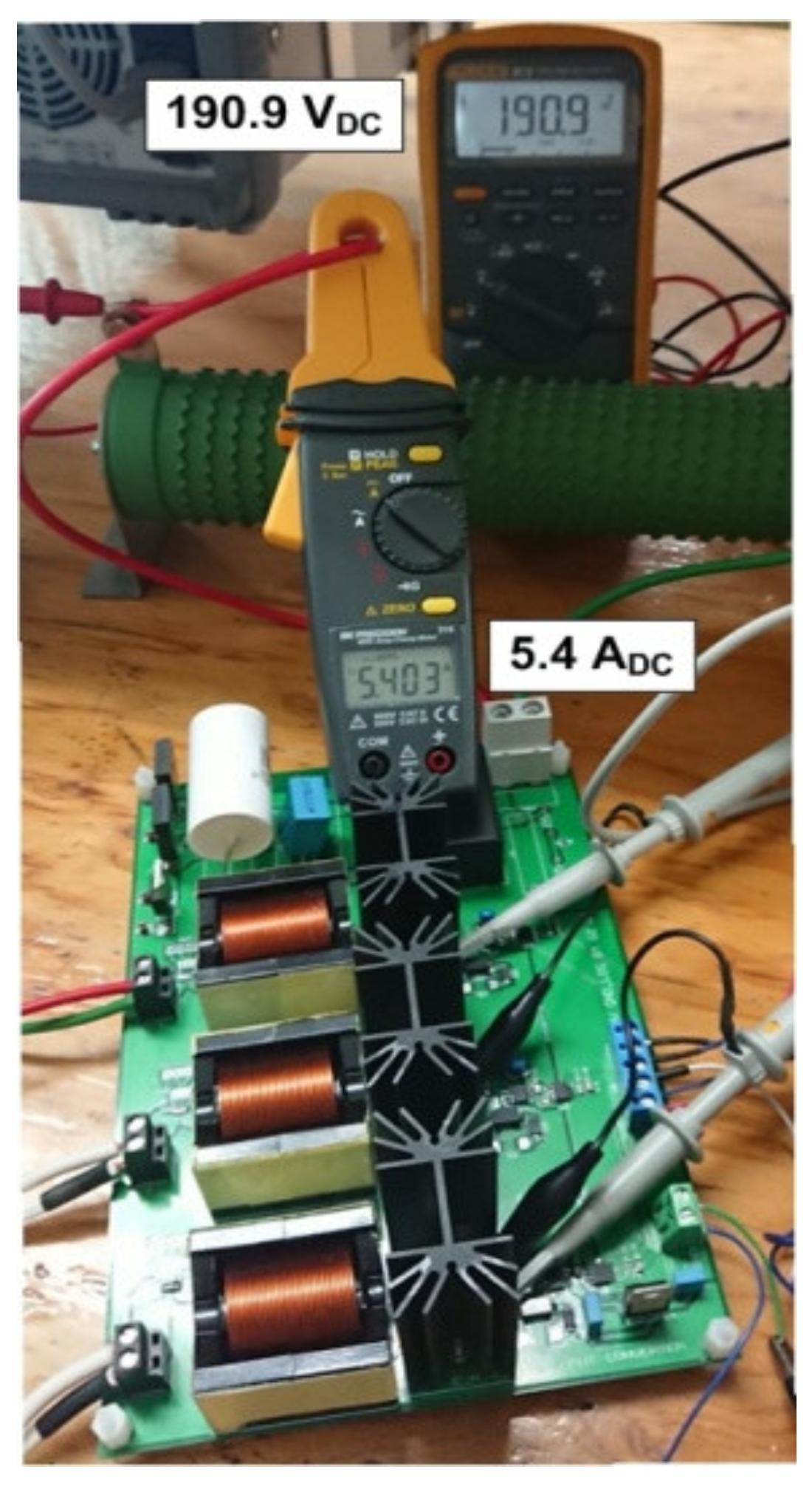

4. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Vin1, Vin2, Vin3 | Three input voltages |

| Φ | Control signals phase shift |

| d | Duty cycle in switching devices |

| dmin | Minimum duty cycle |

| S1, S2, S3 | Digital control signals in each transistor |

| L1, L2, L3 | Inductors for each input voltage source |

| IL1, IL2, IL3 | Currents in inductor L1, L2 and L3 |

| ΔI1, ΔI2, ΔI3 | Ripple current in L1, L2 and L3 |

| C1, C2 | Capacitors in boost circuits in first and second inputs |

| VC1, VC2 | Voltage in capacitors C1 and C2 |

| D1, D2, D3 | Diodes in boost circuits for each input |

| Co | Output capacitor |

| Vo | Output DC voltage |

| RL | Output load |

| ∆t1 to ∆t6 | Time interval in each operating mode |

| M1 to M6 | Operating modes 1 to 6 |

| x1 to x6 | State variables in state space analysis |

| Vin min | Minimum input voltage |

| MVDC | Voltage gain |

| fs | Switching frequency |

| swn, n = 1, 2, 3 | State of switches S1, S2 and S3 |

| Io | Output current |

| ΔVc1, ΔVc2 | Ripple voltage in C1 and C2 |

| Vo | Output voltage |

| ΔVo | Output voltage ripple |

| Po | Output power |

| Pin1, Pin2, Pin3 | Input power for each voltage source |

| η | Converter efficiency |

References

- Prasanth, J.; Rajasekar, N. A Novel Flower Pollination Based Global Maximum Power Point Method for Solar Maximum Power Point Tracking. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 32, 8486–8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaramasu, V.; Dekka, A.; Durán, M.; Kouro, S.; Wu, B. PMSG-based wind energy conversion systems: Survey on power converters and controls. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2017, 11, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Hui, Q.; Li, S. Multi-energy storage system model based on electricity heat and hydrogen coordinated optimization for power grid flexibility. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 5, 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-M. A Systematic Approach to Synthesizing Multi-Input DC–DC Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Z.J.; Ruan, T.; Zhu, M. Power Management Circuit for Wireless Sensor Nodes Powered by Energy Harvesting: On the Synergy of Harvester and Load. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 34, 8671–8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooranian, Z.; Abawajy, J.H.; Vinod, P.; Mauro, C. Scheduling Distributed Energy Resource Operation and Daily Power Consumption for a Smart Building to Optimize Economic and Environmental Parameters. Energies 2018, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Ionel, D.M. Modelling and Control of a Multiport Converter based EV Charging Station with PV and Battery. In Proceedings of the IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference, Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, D.; Beik, O.; Emadi, A. Standalone Integrated Power Electronics System: Applications for Off-Grid Rural Locations. IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2018, 6, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, P.; Hossein, H.S.; Sabahi, M.; Jalilzadeh, T.; Maalandish, M. A New High Step-Up Multi-Input Multi-Output DC–DC Converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 5197–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, R.; Farzanehfard, H.; Kampitsis, G.; Mattavelli, M.; Matioli, E.; Esteki, M. Fully Soft-Switched High Step-Up Nonisolated Three-Port DC–DC Converter Using GaN HEMTs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 67, 8371–8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varesi, K.; Hossein, H.S.; Sabahi, M.; Babaei, E. Modular non-isolated multi-input high step-up dc–dc converter with reduced normalised voltage stress and component count. IET Power Electron. 2018, 11, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzahuatl, E.; Cortes, D.; Ramirez-Salinas, M.A.; Resa, J.; Hernandez, L.; Hernandez, F.D. Modeling, Design Procedure and Control of a Low-Cost High-Gain Multi-Input Step-Up Converter. Electronics 2019, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, B.; Luo, Q. High step-up converter with capacity of multiple input. IET Power Electron. 2012, 5, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLyman, C.W.T. Transformer and Inductor Design Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781439836880. [Google Scholar]

- Varesi, K.; Hossein, H.S.; Sabahi, M.; Babei, E.; Vosoughi, N. Performance and design analysis of an improved non-isolated multiple input buck DC–DC converter. IET Power Electron. 2017, 10, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Bae, S. Multiple-input Soft-switching Ćuk Converter. In Proceedings of the IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1–5 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Modes 1, 3, 5 | Mode 2 | Mode 4 | Mode 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Lowest input voltage, Vin min | 12 V |

| First input voltage source, Vin1 | 12 V |

| Second input voltage source, Vin2 | 24 V |

| Third voltage source, Vin3 | 48 V |

| Output voltage, Vo | 190 V |

| Output current, Io | 5.2 A |

| Output power, Po | 1000 W |

| Switching frequency, fs | 100 kHz |

| Voltage gain, MVDC | 15.7 |

| Duty cycle, dn | 0.66~0.8 |

| Phase shift | 120° |

| Voltage ripple in C1, ΔVcp1 | 50 V |

| Voltage ripple in C2, ΔVcp2 | 100 V |

| Output voltage ripple, ΔVo | 2 V |

| Inductors, L1, L2, L3 | 47 µH |

| Capacitor C1 | 0.1 µF |

| Capacitor C2 | 0.2 µF |

| Capacitor Co | 20 µF |

| Output load, Ro | 33 Ω |

| Factor/Topologies | Proposed High-Gain Three-Input Step-Up Converter | High Step-Up Multi-Input Multi-Output Converter [9] | Soft-Switched Step-Up Converter [10] | Modular Step-Up Converter [11] | High-Gain Two-Input Step-Up Converter [12] | Multiphase Buck Converter [15] | Multi-Input Multi-Output [16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-loop current unbalance | Minimum | Minimum | Minimum | Medium | Minimum | Medium | Medium |

| Output power | 1.037 kW | 1 kW (divided in 2 outputs) | 125 W | 200 W | 500 W | 152 W | 100 W |

| Efficiency | 90.51% | 75–96.8% | 97% | 87% | 90–95% | 87–95% | 86% |

| Number of voltage sources | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Input voltage | 24 V, 12 V, 48 V | 52 V, 40 V, 50 V, | 24 V, 20 V | 10 V, 10 V | 24 V, 24 V | 100 V, 50 V | 60 V, 12 V |

| Output voltage | 190 V | 453 V, 322 V | 200 V | 250 V | 186.6 V | 18.5 V | 48 V |

| Number of power switching devices | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Number of diodes | 3 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Number of inductors | 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Number of capacitors | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Switching frequency | 100 kHz | 40 kHz | 100 kHz | 25 kHz | 100 kHz | 10 kHz | 100 kHz |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Netzahuatl-Huerta, E.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, L.; Cortes, D.; Ramirez-Hernandez, J. Design and Implementation Procedure of a High-Gain Three-Input Step-Up 1 kW Converter. Electronics 2021, 10, 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10050625

Netzahuatl-Huerta E, Hernandez-Gonzalez L, Cortes D, Ramirez-Hernandez J. Design and Implementation Procedure of a High-Gain Three-Input Step-Up 1 kW Converter. Electronics. 2021; 10(5):625. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10050625

Chicago/Turabian StyleNetzahuatl-Huerta, Edgardo, Leobardo Hernandez-Gonzalez, Domingo Cortes, and Jazmin Ramirez-Hernandez. 2021. "Design and Implementation Procedure of a High-Gain Three-Input Step-Up 1 kW Converter" Electronics 10, no. 5: 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10050625

APA StyleNetzahuatl-Huerta, E., Hernandez-Gonzalez, L., Cortes, D., & Ramirez-Hernandez, J. (2021). Design and Implementation Procedure of a High-Gain Three-Input Step-Up 1 kW Converter. Electronics, 10(5), 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10050625