FP-Growth Algorithm for Discovering Region-Based Association Rule in the IoT Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We proposed a novel problem of discovering association rules in item transactions considering the item purchase location.

- We proposed RFP-Growth which organizes item transaction data with location data into clusters by dense regions and discovers association rules for each cluster.

- We conducted extensive experiments on the real and synthetic datasets to prove that RFP-Growth discovers the new frequent rules that are not discovered in the analysis of the entire data.

2. Background and Related Works

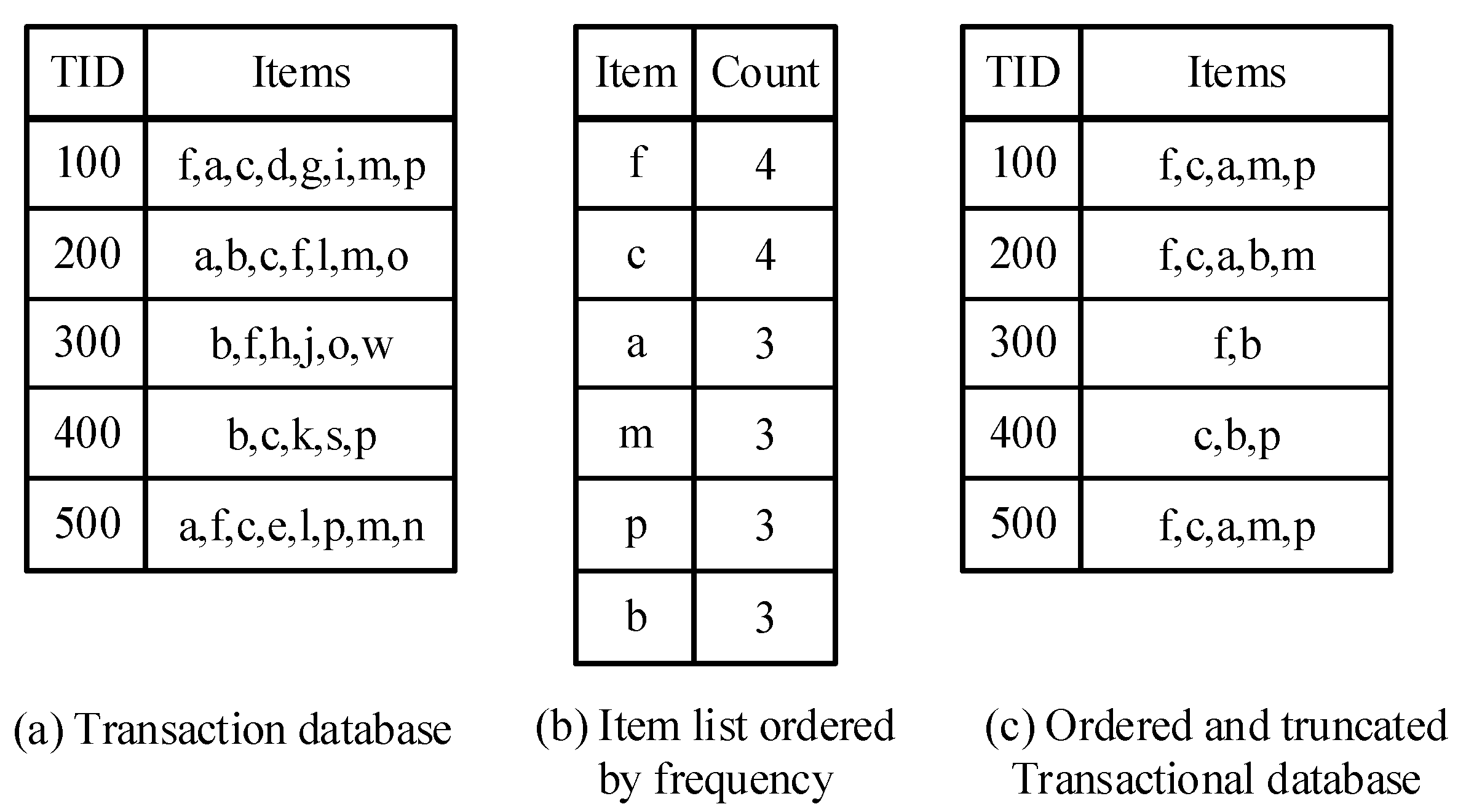

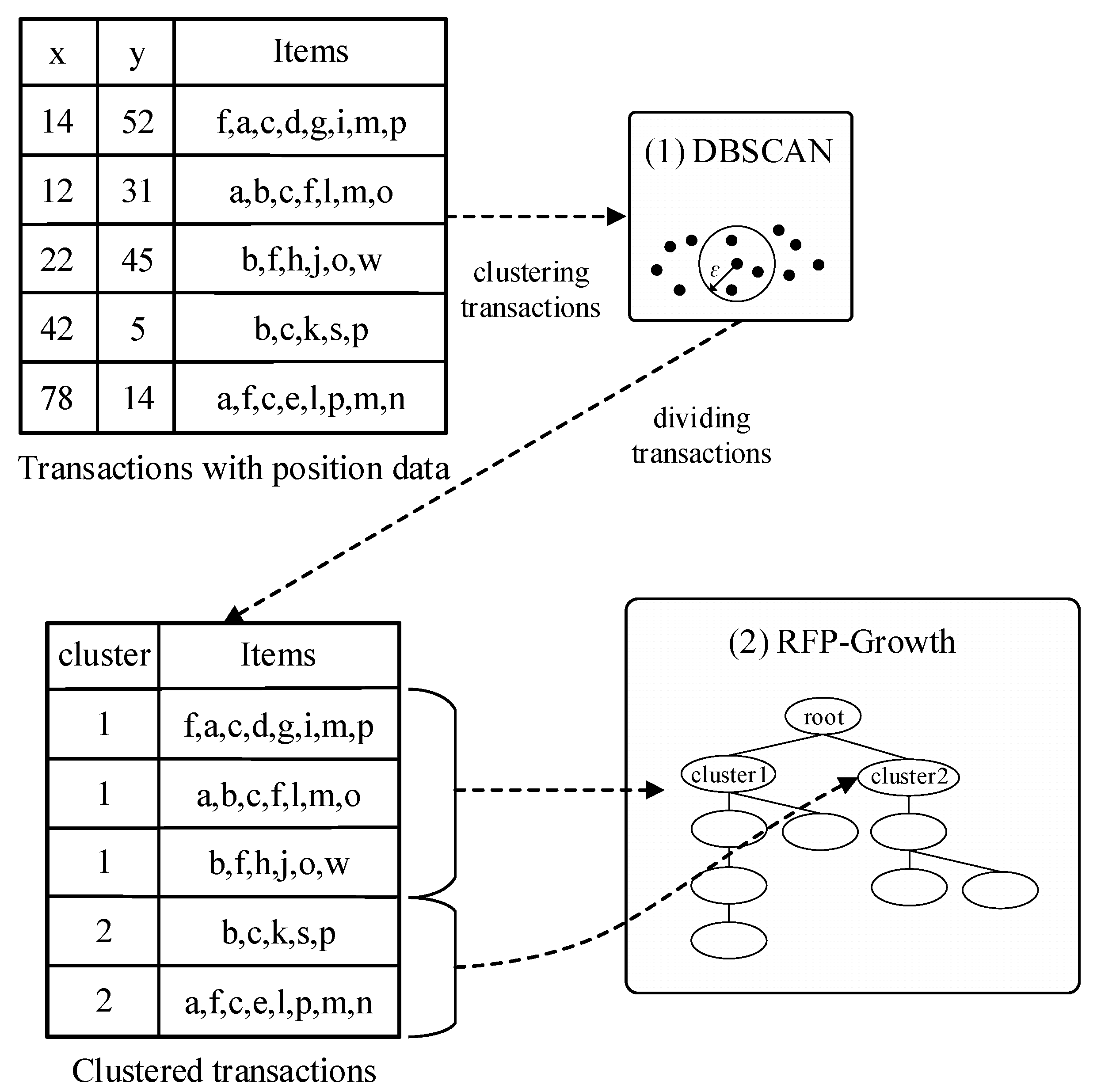

2.1. Background: FP-Growth

2.2. Variants of FP-Growth

2.3. FP-Growth Based on Spatial Data

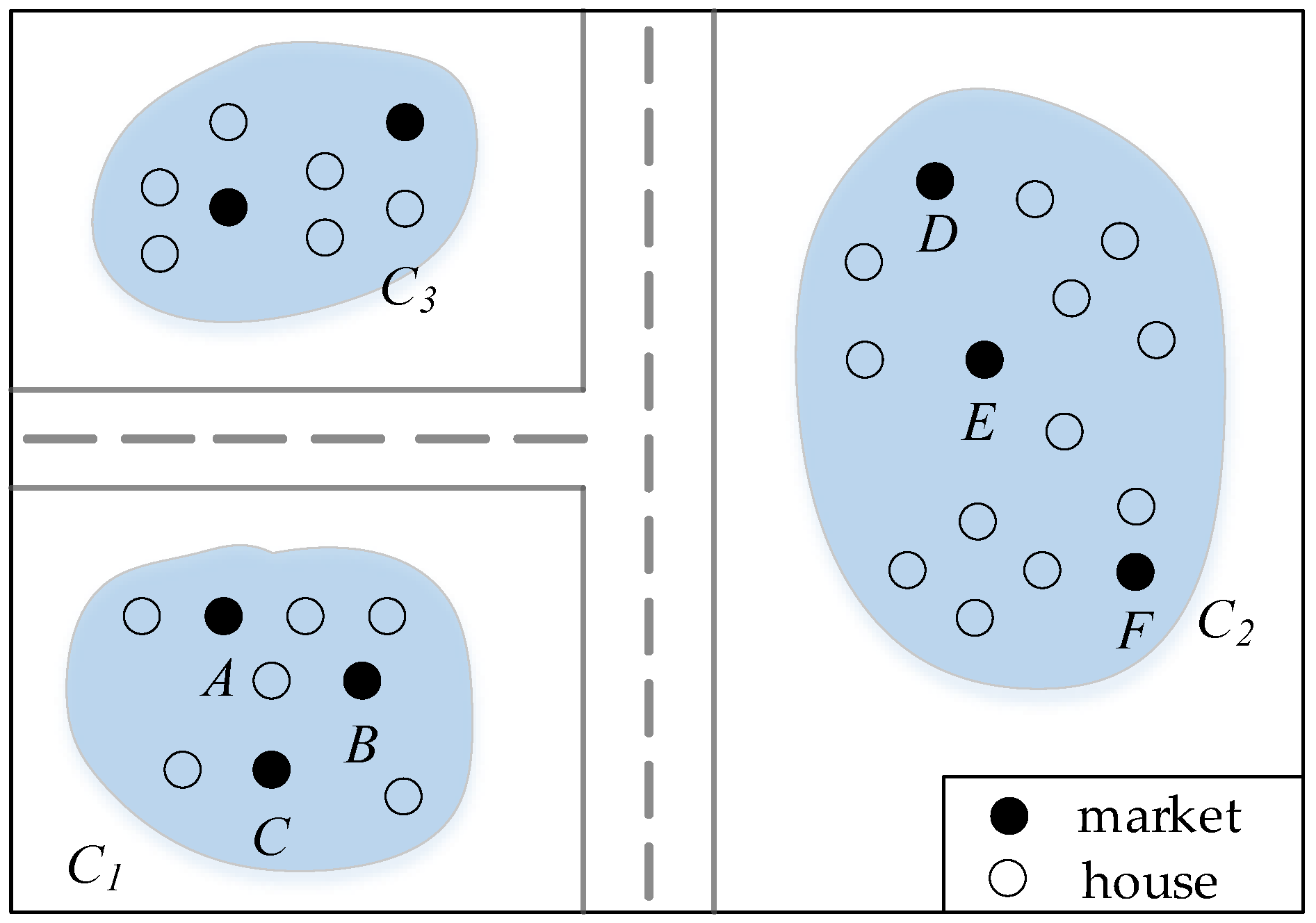

2.4. Problem Definition

3. Methods

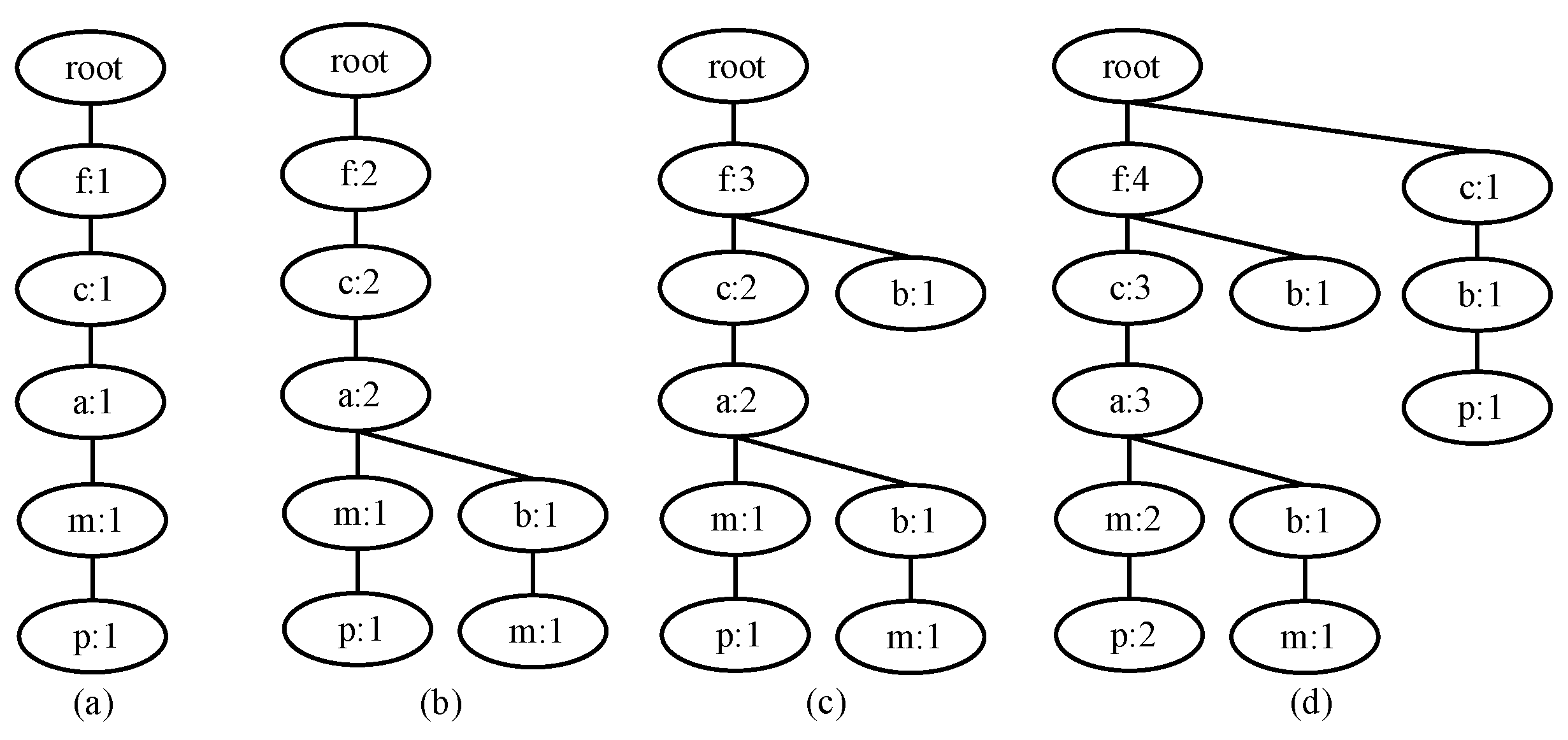

3.1. Overview of RFP-Growth

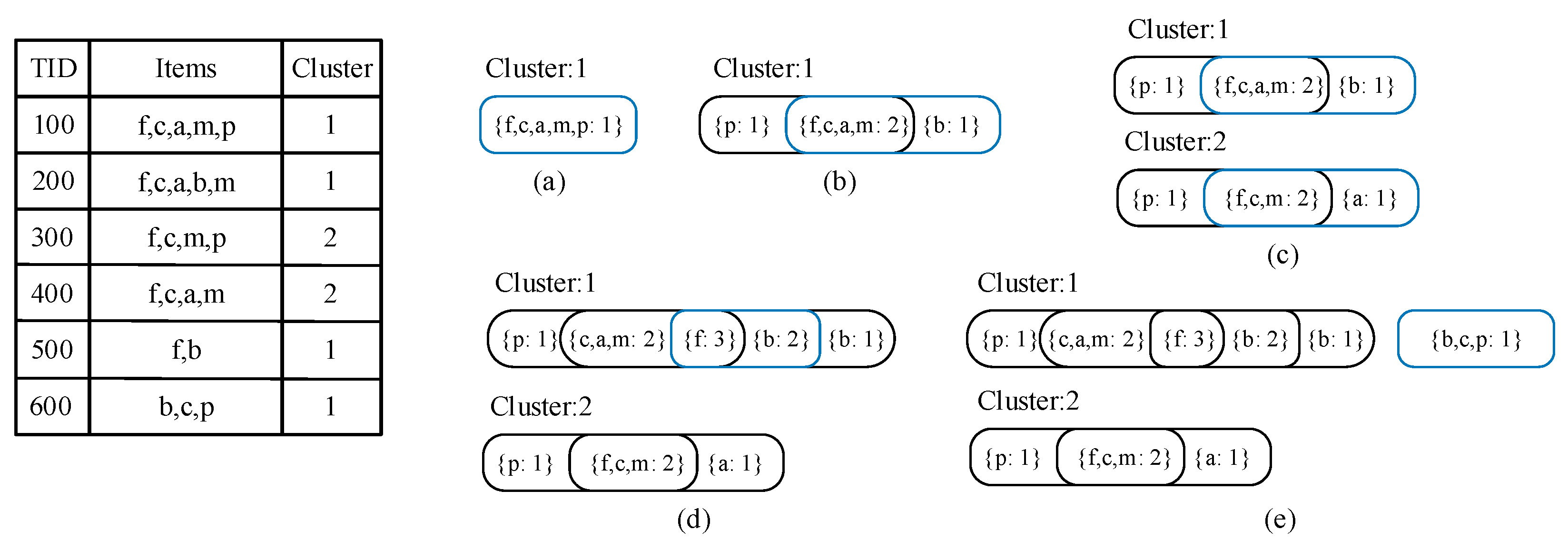

3.2. Intersection-Based FP-Tree

| Algorithm1 TreeBuilder |

| Input: A transaction DB, a set Q of query keywords, a set R of region Output: FP-tree

|

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experiment Setting

4.1.1. Algorithms

4.1.2. Data Sets

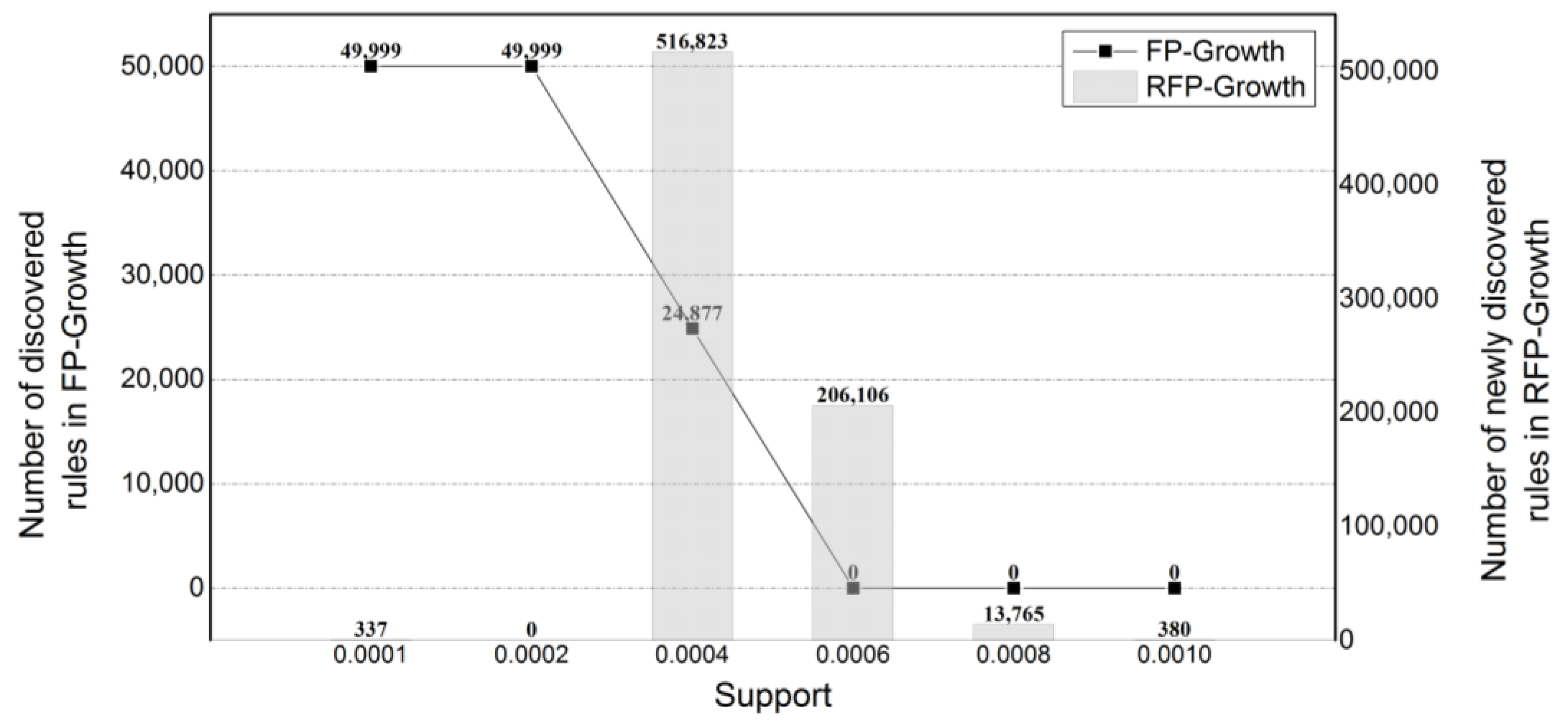

4.2. The Discovery of New Association Rules

4.3. Memory Consumption

4.4. The Effect of the Number of Clusters

4.5. The Effect of the Size of Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alshammari, H.; El-Ghany, S.A.; Shehab, A. Big IoT Healthcare Data Analytics Framework Based on Fog and Cloud Computing. J. Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 16, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Yang, P.; Hanneghan, M.; Tang, S.; Zhou, B. A Hybrid Hierarchical Framework for Gym Physical Activity Recognition and Measurement Using Wearable Sensors. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Qiu, L.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Liu, A.; Alam Bhuiyan, Z.; Ma, Y. Edge-Computing-Based Trustworthy Data Collection Model in the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 4218–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shargabi, A.; Siewe, F. A Lightweight Association Rules Based Prediction Algorithm (LWRCCAR) for Context-Aware Systems in IoT Ubiquitous, Fog, and Edge Computing Environment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference (FTC) 2020, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–6 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Park, J.S. An SDN-Based Packet Scheduling Scheme for Transmitting Emergency Data in Mobile Edge Computing Environments. Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tang, Z. Strategy for Task Offloading of Multi-user and Multi-server Based on Cost Optimization in Mobile Edge Computing Environment. J. Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 17, 615–629. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-H. Next Task Size Prediction Method for FP-Growth Algorithm. Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Imieliski, T.; Swami, A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD Record, New York, NY, USA, 1 June 1993; Volume 22, pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Srikant, R. Fast algorithms for mining association rules in large databases. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 September 1994; pp. 487–499. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Yin, Y. Mining Frequent Patterns without Candidate Generation. ACM SIGMOD Rec. 2000, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannella, C.; Han, J.; Pei, J.; Yan, X.; Yu, P.S. Mining Frequent Patterns in Data Streams at Multiple Time Granularities. In Data Mining: Next Generation Challenges and Future Directions; Kargupta, H., Joshi, A., Sivakumar, K., Yesha, Y., Eds.; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zaïane, O.R.; El-Hajj, M. COFI Approach for Mining Frequent Itemsets Revisited. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM SIGMOD Workshop on Research Issues in Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, Paris, France, 13 June 2004; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan, M.; Alhajj, R. DRFP-tree: Disc-resident frequent pattern tree. Appl. Intell. 2009, 30, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Alhajj, R. A bounded and Adaptive Memory-based Approach to Mine Frequent Patterns from Very Large Databases. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B 2011, 41, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.K.-S.; Khan, Q.I.; Hoque, T. CanTree:A Tree Structure for Efficient Incremental Mining of Frequent Patterns. In Proceedings of the Fifth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM’05), Houston, TX, USA, 27–30 November 2005; pp. 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ünvan, Y.A. Market basket analysis with association rules. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2021, 50, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, Z.; Oo, K.K. An Improvement of Apriori Mining Algorithm using Linked List Based Hash Table. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Advanced Information Technologies (ICAIT), Yangon, Myanmar, 4–5 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Liu, P.; Yi, J. An Improved FP-Tree Algorithm for Mining Maximal Frequent Patterns. In Proceedings of the 2018 10th International Conference on Measuring Technology and Mechatronics Automation (ICMTMA), Changsha, China, 10–11 February 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.K.-S.; Khan, Q.I. DSTree: A tree structure for the mining of frequent sets from data streams. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM’06), Hong Kong, China, 18–22 December 2006; pp. 928–932. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Lu, H.; Yu, J.X.; Wang, W.; Xiao, X. AFOPT: An efficient implementation of pattern growth approach. In Proceedings of the ICDM Workshop, Melbourne, FL, USA, 19–22 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, W.; Zaiane, O.R. Incremental mining of frequent patterns without candidate generation or support constraint. Database Engineering and Applications Symposium. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Database Engineering and Applications Symposium, Hong Kong, China, 18 July 2003; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Maiti, S.; Subramanyam, R.B.V. Mining co-location patterns from distributed spatial data. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 33, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Nam, K.W.; Ryu, K.H. Fast mining of spatial frequent wordset from social database. Spat. Inf. Res. 2017, 25, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kiran, R.U.; Shrivastava, S.; Fournier-Viger, P.; Zettsu, K.; Toyoda, M.; Kitsuregawa, M. Discovering Frequent Spatial Patterns in Very Large Spatiotemporal Databases. In Proceedings of the SIGSPATIAL ’20: 28th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 3–6 November 2020; pp. 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.-H. DiffNodesets: An Efficient Structure for Fast Mining Frequent Itemsets. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 41, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryabarzan, N.; Minaei-Bidgoli, B.; Teshnehlab, M. negFIN: An efficient algorithm for fast mining frequent itemsets. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 105, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TID | Market | Items |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | Bread, Milk, Peanut |

| 2 | A | Bread, Diaper, Beer, Eggs, Peanut |

| 3 | B | Milk, Diaper, Beer, Cola |

| 4 | B | Bread, Milk, Diapers, Beer |

| 5 | C | Diaper, Beer, Eggs |

| 6 | D | Bread, Beer, Peanut, Eggs |

| 7 | D | Beer, Milk, Peanut |

| 8 | E | Beer, Peanut, Diaper |

| 9 | E | Bread, Milk, Cola, Eggs |

| 10 | F | Beer, Milk, Peanut, Cola, Eggs |

| Parameters | Description | Values |

|---|---|---|

| n | no. of objects | 1K, 2K, 3K, 4K, 5K, 6K, 7K, 8K, 9K, 10K |

| k | no. of clusters | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 |

| minsup | minimum support | 0.20, 0.22, 0.24, 0.26, 0.28, 0.30, 0,32, 0,34, 0.36, 0.38, 0.40, 0.42, 0.44, 0.46, 0.48, 0.50, 0.52, 0.54, 0.56, 0.58, 0.60, 0.62, 0.64, 0.66, 0.68, 0.70 |

| Invoice No. | Stock Code | Quantity | Invoice Date | Unit Price | Customer ID | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 536365 | 85123A | 6 | 01-12-2010 08:26 | 2.55 | 17850 | UK |

| 536365 | 71053 | 6 | 01-12-2010 08:26 | 3.39 | 17850 | UK |

| 356365 | 84406B | 8 | 01-12-2010 08:26 | 2.75 | 17850 | UK |

| 536370 | 22728 | 24 | 01-12-2010 08:45 | 3.75 | 12583 | France |

| 536370 | 22727 | 24 | 01-12-2010 08:45 | 3.75 | 12583 | France |

| 536370 | 22726 | 12 | 01-12-2010 08:45 | 3.75 | 12583 | France |

| 536389 | 22941 | 6 | 01-12-2010 10:03 | 8.5 | 12431 | Australia |

| 536389 | 22941 | 8 | 01-12-2010 10:03 | 4.95 | 12431 | Australia |

| 536389 | 22941 | 12 | 01-12-2010 10:03 | 1.25 | 12431 | Australia |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, H.-J.; Yang, Y.; Park, J.S.; Kim, B. FP-Growth Algorithm for Discovering Region-Based Association Rule in the IoT Environment. Electronics 2021, 10, 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10243091

Jang H-J, Yang Y, Park JS, Kim B. FP-Growth Algorithm for Discovering Region-Based Association Rule in the IoT Environment. Electronics. 2021; 10(24):3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10243091

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Hong-Jun, Yeongwook Yang, Ji Su Park, and Byoungwook Kim. 2021. "FP-Growth Algorithm for Discovering Region-Based Association Rule in the IoT Environment" Electronics 10, no. 24: 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10243091

APA StyleJang, H.-J., Yang, Y., Park, J. S., & Kim, B. (2021). FP-Growth Algorithm for Discovering Region-Based Association Rule in the IoT Environment. Electronics, 10(24), 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10243091