Abstract

The paper investigates various implementations of a master–slave paradigm using the popular OpenMP API and relative performance of the former using modern multi-core workstation CPUs. It is assumed that a master partitions available input into a batch of predefined number of data chunks which are then processed in parallel by a set of slaves and the procedure is repeated until all input data has been processed. The paper experimentally assesses performance of six implementations using OpenMP locks, the tasking construct, dynamically partitioned for loop, without and with overlapping merging results and data generation, using the gcc compiler. Two distinct parallel applications are tested, each using the six aforementioned implementations, on two systems representing desktop and worstation environments: one with Intel i7-7700 3.60 GHz Kaby Lake CPU and eight logical processors and the other with two Intel Xeon E5-2620 v4 2.10 GHz Broadwell CPUs and 32 logical processors. From the application point of view, irregular adaptive quadrature numerical integration, as well as finding a region of interest within an irregular image is tested. Various compute intensities are investigated through setting various computing accuracy per subrange and number of image passes, respectively. Results allow programmers to assess which solution and configuration settings such as the numbers of threads and thread affinities shall be preferred.

1. Introduction

In today’s parallel programming, a variety of general purpose Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are widely used, such as OpenMP, OpenCL for shared memory systems including CPUs and GPUs, CUDA, OpenCL, OpenACC for GPUs, MPI for cluster systems or combinations of these APIs such as: MPI+OpenMP+CUDA, MPI+OpenCL [1], etc. On the other hand, these APIs allow to implement a variety of parallel applications falling into the following main paradigms: master–slave, geometric single program multiple data, pipelining, divide-and-conquer.

At the same time, multi-core CPUs have become widespread and present in all computer systems, both desktop and server type systems. For this reason, optimization of implementations of such paradigms on such hardware is of key importance nowadays, especially as such implementations can serve as templates for coding specific domain applications. Consequently, within this paper we investigate various implementations of one of such popular programming patterns—master–slave, implemented with one of the leading APIs for programming parallel applications for shared memory systems—OpenMP [2].

2. Related Work

Works related to the research addressed in this paper can be associated with one of the following areas, described in more detail in subsequent subsections:

- frameworks related to or using OpenMP that target programming abstractions even easier to use or at a higher level than OpenMP itself;

- parallelization of master–slave and producer–consumer in OpenMP including details of analyzed models and proposed implementations.

2.1. OpenMP Related Frameworks and Layers for Parallelization

SkePU is a C++ framework targeted at using heterogeneous systems with multi-core CPUs and accelerators. In terms of processing structures, SkePU incorporates several skeletons such as Map, Reduce, MapReduce, MapOverlap, Scan and Call. SkePU supports back-ends such as: sequential CPU, OpenMP, CUDA and OpenCL. Work [3] describes a back-end for SkePU version 2 [4] that allows to schedule workload on CPU+GPU systems. Better performance than the previous SkePU implementation is demonstrated. The original version of hybrid execution in SkePU 1 ran StarPU [5] as a back-end. The latter allows to encompass input data with codelets that can be programmed with C/C++, OpenCL and CUDA. Eager, priority and random along with caching policies are available for scheduling. Workload can be partitioned among CPUs and accelerators either automatically or manually with a given ratio. Details of how particular skeletons are assigned in shown in [3]. In terms of modeling, autotuning is possible using a linear performance formulation and its speed-ups were shown versus CPU and accelerator implementations.

OpenStream is an extension of OpenMP [6,7] enabling to express highly dynamic control and data flows between dependent and nested tasks. Additional input and output clauses for the task construct are proposed with many examples presenting expressiveness of the approach. There is a trade-off between expressiveness of streaming annotations and overhead which is studied versus Cilk using an example of recursive Fibonacci implementations and obtaining granularity threshold above which task’s overheads are amortized. Additional clauses peek and tick allow reading data from a stream without advancing the stream as well as advancing the read index in streams. Speed-ups of the proposed OpenMP streaming solution over sequential LAPACK are demonstrated [6] for Cholesky factorization of various sizes (up to superlinear 27.4 for 4096 × 4096 matrix size and 256 numbers of blocks per matrix, due to caching effects) as well as SparseLU (19.5 for block size 64 × 64 and 22 for block size 128 × 128 for 4096+ numbers of blocks). A Gauss–Seidel algorithm using the proposed solution, hand coded, achieved the speed-ups of 8.7 for 8k × 8k matrix and 256 × 256 tile size. Tests were conducted on a dual-socket AMD Opteron Magny-Cours 6164HE machine with 2 × 12 cores running at 1.7 GHz and 16 GB of RAM.

Argobots [8] is a lightweight threading layer that can be used for efficient processing and coupling high-level programming abstractions to low-level implementations. Specifically, the paper shows that the solution outperforms state-of-the-art generic lightweight threading libraries such as MassiveThreads and Qthreads. Additionally, integrating Argobots with MPI and OpenMP is presented with better performance of the latter for an application with nested parallelism than competing solutions. For the former configuration, better opportunities regarding reduction of synchronization and latency are shown for Argobots compared to Pthreads. Similarly, better performance of Argobots vs Pthreads is discussed for I/O operations.

PSkel [9], as a framework, targets parallelization of stencil computations, in a CPU+GPU environment. As its name suggests, it uses parallel skeletons and can use NVIDIA CUDA, Intel TBB and OpenMP as back-ends. Authors presented speed-ups of the hybrid CPU+GPU version up to up to 76% and 28%, versus CPU-only and GPU-only codes.

Paper [10] deals with introduction of another source layer between a program with OpenMP constructs and actual compilation. This approach translates OpenMP constructs into an intermediate layer (NthLib is used) and the authors are advocating future flexibility and ease of introduction of changes into the implementation in the intermediate layer.

Optimization of OpenMP code can be performed at a lower level of abstraction, even targeting specific constructs. For example, in paper [11] authors present a way for automatic transformation of code for optimization of arbitrarily-nested loop sequences with affine dependencies. An Integer Linear Programming (ILP) formulation is used for finding good tiling hyperplanes. The goal is optimization of locality and communication-minimized coarse-grained parallelization. Authors presented notable speed-ups over state-of-the-art research and native compilers ranging from 1.6x up to over 10x, depending on the version and benchmark. Altogether, significant gains were shown for all of the following codes: 1-d Jacobi, 2-d FDTD, 3-d Gauss-Seidel, LU decomposition and Matrix Vec Transpose.

In paper [12], the author presented a framework for automatic parallelization of divide-and-conquer processing with OpenMP. The programmer needs to provide code for key functions associated with the paradigm, i.e., data partitioning, computations and result integration. Actual mapping of computations onto threads is handled by the underlying runtime layer. The paper presents performance results for an application of parallel adaptive quadrature integration with an irregular and imbalanced corresponding processing tree. Obtained speed-ups using an Intel Xeon Phi system reach around 90 for parallelization of an irregular adaptive integration code which was compared to a benchmark without thread management at various levels of the divide-and-conquer tree which resulted in maximum speed-ups of 98.

OmpSs [13] (https://pm.bsc.es/ompss (accessed on 16 April 2021)) extends OpenMP with new directives to support asynchronous parallelism and heterogeneity (like GPUs, FPGAs). A target construct is available for heterogeneity implementation, data dependencies can be defined between various tasks of the program. Functions can also be annotated with the task construct. While OpenMP and OmpSs are similar, some differences exist (https://pm.bsc.es/ftp/ompss/doc/user-guide/faq-openmp-vs-ompss.html (accessed on 16 April 2021)). Specifically, in OmpSs, that uses #pragma omp directives, one creates work using #pragma omp task or #pragma omp for and the program already starts with a team of threads out of which one executes the main function. #pragma omp parallel is ignored. For the for loop, a compiler creates a task which will create internally several more tasks out of which each implements some part of the iteration space of the corresponding parallel loop. OmpSs has been an OpenMP forerunner for some of the features [14,15]. Recent paper [16] presents an architecture and a solution that extends the OmpSs@FPGA environment with the possibility for the tasks offloaded to FPGA to create and synchronize nested tasks without the need to involve the host. OmpSs-2, following its specification (https://pm.bsc.es/ftp/ompss-2/doc/spec (accessed on 16 April 2021)), extends the tasking model of OmpSs/OpenMP so that both task nesting and fine-grained dependencies across different nesting levels are supported. It uses #pragma oss constructs. Important features include, in particular: nested dependency domain connection, early release of dependencies, weak dependencies, native offload API task Pause/Resume API. It should be noted that the latest OpenMP standard also allows tasking as well as offloading to external devices such as Intel Xeon Phi or GPUs [2].

Paper [17] presents PLASMA—the Parallel Linear Algebra Software for Multicore Architectures—a version which is an OpenMP task based implementation adopting a tile-based approach to storage, along with algorithms that operate on tiles and use OpenMP for dynamic scheduling based on tasks with dependencies and priorities. Detailed assessment of the software performance is presented in the paper using three platforms with 2 × Intel Xeon CPU E5-2650 v3 CPUs at 2.3 GHz, Intel Xeon Phi 7250 and 2 × IBM POWER8 CPUs at 3.5 GHz, respectively, using gcc compared to MKL (for Intel) and ESSL (for IBM). PLASMA resulted in better performance for algorithms suited for its tile type approach such as factorization as well as QR factorization in the case of tall and skinny matrices.

In [18] authors presented parts of the first prototype of sLaSs library with auto tunable implementations of operations for linear algebra. They used OmpSs with its task based programming model and features such as weak dependencies and regions with the final clause. They benchmarked their solution using a supercomputer featuring nodes with 2 sockets with Intel Xeon Platinum 8160 CPUs, with 24 cores and 48 logical processors. Results are shown for TRSM for th original LASs, sLaSs and PLASMA, MKL and ATLAS, for NPGETRF for LASs, sLaSs and MKL and for NPGESV for LASs and sLaSs demonstrating improvement of the proposed solution of about 18% compared to LASs.

2.2. Parallelization of Master–Slave with OpenMP

master–slave can be thought of as a paradigm to enable parallelization of processing among independently working slaves that receive input data chunks from the master and return results to the master.

OpenMP by itself offers ways of implementing the master–slave paradigm, in particular using:

- #pragma omp parallel along with #pragma omp master directives or#pragma omp parallel with distinguishing master and slave codes based on thread ids.

- #pragma omp parallel with threads fetching tasks in a critical section, a counter can be used to iterate over available tasks. In [19], it is called an all slave model.

- Tasking with the #pragma omp task directive.

- Assignment of work through dynamic scheduling of independent iterations of a for loop.

In [19], the author presented virtually identical and almost perfectly linear speed-up of the all slave model and the (dynamic,1) loop distribution for the Mandelbrot application on 8 processors. In our case, we provide extended analysis of more implementations and many more CPU cores.

In work [20], authors proposed a way to extend OpenMP for master–slave programs that can be executed on top of a cluster of multiprocessors. A source-to-source translator translates programs that use an extended version of OpenMP into versions with calls to their runtime library. OpenMP’s API is proposed to be extended with #pragma domp parallel taskq for initialization of a work queue and #pragma domp task for starting tasks as well as #pragma domp function for specification of MPI description for the arguments of a function. The authors presented performance results for applications such as computing Fibonacci numbers as well as embarrassingly parallel examples such as generation of Gaussian random deviates and Synthetic Matrix Addition showing very good scalability with configurations up to 4 × 2 and 8 × 1 (processes × threads). More interesting in the context of this paper were results for MAND which is a master–slave application that computes the Mandelbrot set for a 2-d image of size 512 × 512 pixels. Speed-up on an SMP machine for the best 1 × 4 configuration (4 CPUs) amounted to 3.72 while on a cluster of machines (8 CPUs) was 6.4, with a task stealing mechanism.

OpenMP will typically be used for parallelization within cluster nodes and integrated with MPI at a higher level for parallelization of master–slave computations among cluster nodes [1,21]. Such a technique should yield better performance in a cluster with multi-core CPUs than an MPI only approach in which several processes are used as slaves as opposed to threads within a process communicating with MPI. Furthermore, overlapping communication and computations can be used for earlier sending out data packets by the master for hiding slave idle times. Such a hybrid MPI/OpenMP scheme has been further extended in terms of dynamic behavior and malleability (ability to adapt to a changing number of processors) in [22]. Specifically, the authors have implemented a solution and investigated MPI’s support in terms of needed features for an extended and dynamic master/slave scheme. A specific implementation was used which is called WaterGAP that computes current and future water availability worldwide. It partitions the tested global region in basins of various sizes which are forwarded to slaves for independent (fro other slaves) processing. Speed-up is limited by processing of the slave that takes the maximum of slaves’ times. In order to deal with load imbalance, dynamic arrival of slaves has been adopted. The master assigns the tasks by size, from the largest task. Good allocation results in large basins being allocated to a process with many (powerful) processors, smaller basins to a process with fewer (weaker) processors. If a more powerful (in the aforementioned sense) slave arrives, the system can reassign a large basin. Furthermore, slave processes can dynamically split into either processes or threads for parallelization. The authors have concluded that MPI-2 provides needed support for these features apart from a scenario of sudden withdrawal of slaves in the context of proper finalization of an MPI application. No numerical results have been presented though.

In the case of OpenMP, implementations of master–slave and the producer–consumer pattern might share some elements. A buffer could be (but does not have to be) used for passing data between the master and slaves and is naturally used in producer–consumer implementations. In master–slave, the master would typically manage several data chunks ready to be distributed among slaves while in producer–consumer producer or producers will typically add one data chunk at a time to a buffer. Furthermore, in the producer–consumer pattern consumers do not return results to the producer(s). In the producer–consumer model we typically consider one or more producers and one or more consumers of data chunks. Data chunk production and consuming rates/speeds might differ, in which case a limited capacity buffer is used into which producer(s) inserts() data and consumer(s) fetches() data from for processing.

Book [1] contains three implementations of the master–slave paradigm in OpenMP. These include the designated-master, integrated-master and tasking, also considered in this work. Research presented in this paper extends directly those OpenMP implementations. Specifically, the paper extends the implementations with the dynamic-for version, as well as versions overlapping merging and data generation—tasking2 and dynamic-for2. Additionally, tests within this paper are run for a variety of thread affinity configurations, for various compute intensities as well as on four multi-core CPU models, of modern generations, including Kaby Lake, Coffee Lake, Broadwell and Skylake.

There have been several works focused on optimization of tasking in OpenMP that, as previously mentioned, can be used for implementation of master–slave. Specifically, in paper [23], authors proposed extensions of the tasking and related constructs with dependencies produce and consume which creates a multi-producer multi-consumer queue that is associated with a list item. Such a queue can be reused if it already exists. The life time of such a queue is linked to the life time of a parallel region that encompasses the construct. Such a construct can then be used for implementation of the master–slave model as well. In paper [24], the authors proposed an automatic correction algorithm meant for the OpenMP tasking model. It automatically generates correct task clauses and inserts appropriate task synchronization to maintain data dependence relationships. Authors of paper [25] show that when using OpenMP’s tasks for stencil type of computations, when tasks are generated with #pragma omp task for a block of a 3D space, significant gains in performance are possible by adding block objects to locality queues from which a given thread executing a task dequeues blocks using an optimized policy.

3. Motivations, Application Model and Implementations

It should be emphasized that since the master–slave processing paradigm is widespread and at the same time multi-core CPUs are present in practically all desktops and workstations/cluster nodes thus it is important to investigate various implementations and determine preferred settings for such scenarios. At the same time, the processor families tested in this work are in fact representatives of the new generations CPUs in their respective CPU lines. The contribution of this work is experimental assessment of performance of proposed master–slave codes using OpenMP directives and library calls, compiled with gcc and -fopenmp flag for representative desktop and workstation systems with multicore CPUs listed in Table 1.

The model analyzed in this paper distinguishes the following conceptual steps, that are repeated:

- Master generates a predefined number of data chunks from a data source if there is still data to be fetched from the data source.

- Data chunks are distributed among slaves for parallel processing.

- Results of individually processed data chunks are provided to the master for integration into a global result.

It should be noted that this model, assuming that the buffer size is smaller than the size of total input data, differs from a model in which all input data is generated at once by the master. It might be especially well suited to processing, e.g., data from streams such as from the network, sensors or devices such as cameras, microphones etc.

Implementations of the Master–Slave Pattern with OpenMP

The OpenMP-based implementations of the analyzed master–slave model described in Section 3 and used for benchmarking are as follows:

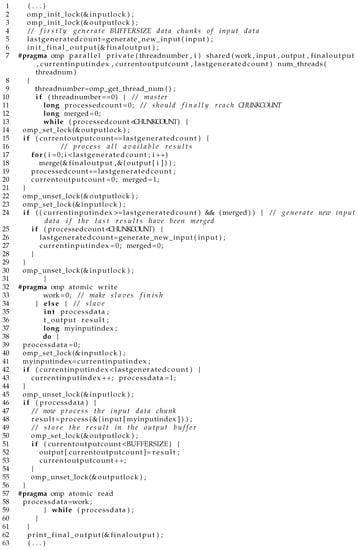

- designated-master (Figure 1)—direct implementation of master–slave in which a separate thread is performing the master’s tasks of input data packet generation as well as data merging upon filling in the output buffer. The other launched threads perform slaves’ tasks.

Figure 1. Designated-master implementation.

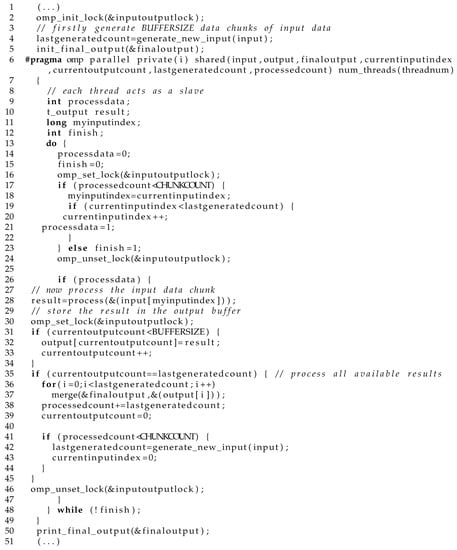

Figure 1. Designated-master implementation. - integrated-master (Figure 2)—modified implementation of the designated-master code. Master’s tasks are moved to within a slave thread. Specifically, if a consumer thread has inserted the last result into the result buffer, it merges the results into a global shared result, clears its space and generates new data packets into the input buffer. If the buffer was large enough to contain all input data, such implementation would be similar to the all slave implementation shown in [19].

Figure 2. Integrated-master implementation.

Figure 2. Integrated-master implementation. - tasking (Figure 3)—code using the tasking construct. Within a region in which threads operate in parallel (created with #pragma omp parallel), one of the threads generates input data packets and launches tasks (in a loop) each of which is assigned processing of one data packet. These are assigned to the aforementioned threads. Upon completion of processing of all the assigned tasks, results are merged by the one designated thread, new input data is generated and the procedure is repeated.

Figure 3. Tasking implementation.

Figure 3. Tasking implementation. - tasking2—this version is an evolution of tasking. It potentially allows overlapping of generation of new data into the buffer and merging of latest results into the final result by the thread that launched computational tasks in version tasking. The only difference compared to the tasking version is that data generation is executed using #pragma omp task.

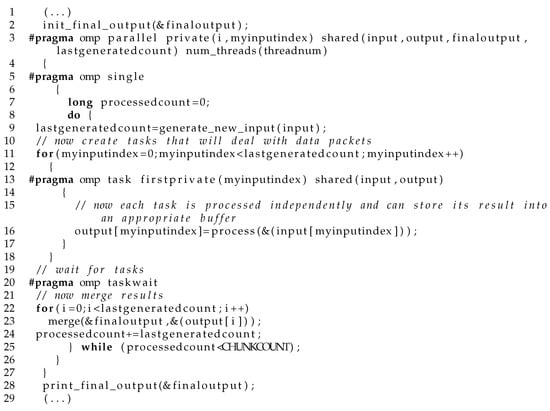

- dynamic-for (Figure 4)—this version is similar to the tasking one with the exception that instead of tasks, in each iteration of the loop a function processing a given input data packet is launched. Parallelization of the for loop is performed with #pragma omp for with a dynamic chunk 1 size scheduling clause. Upon completion, output is merged, new input data is generated and the procedure is repeated.

Figure 4. Dynamic-for implementation.

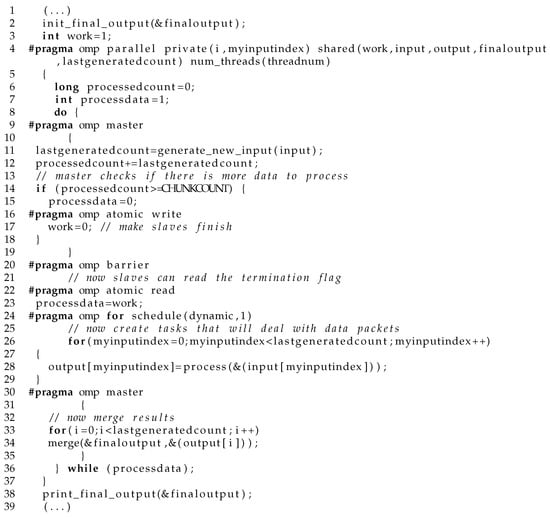

Figure 4. Dynamic-for implementation. - dynamic-for2 (Figure 5)—this version is an evolution of dynamic-for. It allows overlapping of generation of new data into the buffer and merging of latest results into the final result through assignment of both operations to threads with various ids (such as 0 and 4 in the listing). It should be noted that ids of these threads can be controlled in order to make sure that these are threads running on different physical cores as was the case for the two systems tested in the following experiments.

Figure 5. Dynamic-for2 implementation.

Figure 5. Dynamic-for2 implementation.

For test purposes, all implementations used the buffer of 512 elements which is a multiple of the numbers of logical processors.

4. Experiments

4.1. Parametrized Irregular Testbed Applications

The following two applications are irregular in nature which results in various execution times per data chunk and subsequently exploits the dynamic load balancing capabilities of the tested master–slave implementations.

4.1.1. Parallel Adaptive Quadrature Numerical Integration

The first, compute-intensive, application, is numerical integration of any given function. For benchmarking, integration of was run over the [0, 100] range. The range was partitioned into 100,000 subranges which were regarded as data chunks in the processing scheme. Each subrange was then integrated (by a slave) by using the following adaptive quadrature [26] and recursive technique for a given range [a, b] being considered:

- if the area of triangle is smaller than(k = 18) then the sum of areas of two trapezoidsandis returned as a result,

- otherwise, recursive partitioning into two subranges and is performed and the aforementioned procedure is repeated for each of these until the condition is met.

This way increasing the partitioning coefficient increases accuracy of computations and consequently increases the compute to synchronization ratio. Furthermore, this application does not require large size memory and is not memory bound.

4.1.2. Parallel Image Recognition

In contrast to the previous application, parallel image recognition was used as a benchmark that requires much memory and frequent memory reads. Specifically, the goal of the application is to search for at least one occurrence of a template (sized TEMPLATEXSIZExTEMPLATEYSIZE in pixels) within an image (sized IMAGEXSIZExIMAGEYSIZE).

In this case, the initial image is partitioned and within each chunk, a part of the initial image of size (TEMPLATEXSIZE + BLOCKXSIZE)x(TEMPLATEYSIZE + BLOCKYSIZE) is searched for occurrence of the template. In the actual implementation values of IMAGEXSIZE = IMAGEYSIZE = 20,000, BLOCKXSIZE = BLOCKYSIZE = 20, TEMPLATEXSIZE =TEMPLATEYSIZE = 500 in pixels were used.

The image was initialized with every third row and every third column having pixels not matching the template. This results in earlier termination of search for template, also depending on the starting search location in the initial image which results in various search times per chunk.

In the case of this application a compute coefficient reflects how many passes over the initial image are performed. In actual use cases it might correspond to scanning slightly updated images in a series (e.g., satellite images or images of location taken with a drone) for objects. On the other hand, it allows to simulate scenarios of various relative compute to memory access and synchronization overheads for various systems.

4.2. Testbed Environment and Methodology of Tests

Experiments were performed on two systems typical of a modern desktop and workstation systems with specifications outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Testbed configurations.

The following combinations of tests were performed: {code implementation} × {range of thread counts} × {affinity setting} × {partitioning coefficients: 1, 8, 32}. The range of thread counts tested depends on the implementation and varied as follows, based on preliminary tests that identified the most interesting values based on most promising execution times, where means the number of logical processors: for designated-master these were , , and , for all other versions the following were tested: , , and . Thread affinity settings were imposed with environment variables OMP_PLACES and OMP_PROC_BIND [27,28]. Specifically, the following combinations were tested independently: default (no additional affinity settings) marked with default, OMP_PROC_BIND=false which turns off thread affinity (marked in results as noprocbind), OMP_PLACES=cores and OMP_PROC_BIND=close marked with corclose, OMP_PLACES=cores and OMP_PROC_BIND=spread marked with corspread, OMP_PLACES=threads and OMP_PROC_BIND=close marked with thrclose, OMP_ PLACES=sockets without setting OMP_PROC_BIND marked with sockets which defaults to true if OMP_PLACES is set for gcc (https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc-9.3.0/libgomp/OMP_005fPROC_005fBIND.html (accessed on 16 April 2021)). If OMP_PROC_BIND equals true then behavior is implementation defined and thus the above concrete settings were tested.In the experiments the code was tested with compilation flags -O3 and also -O3 -march=native. Best values are reported for each configuration, an average value out of 20 runs is presented along with corresponding standard deviation.

4.3. Results

Since all combinations of tested configurations resulted in a very large number of execution times, we present best results as follows. For each partitioning coefficient separately for numerical integration and compute coefficient for image recognition and for each code implementation 3 best results with a configuration description are presented in Table 2 and Table 3 for numerical integration as well as in Table 4 and Table 5 for image recognition, along with the standard deviation computed from the results. Consequently, it is possible to identify how code versions compare to each other and how configurations affect execution times.

Table 2.

Numerical integration—system 1 results.

Table 3.

Numerical integration—system 2 results.

Table 4.

Image recognition—system 1 results.

Table 5.

Image recognition—system 2 results.

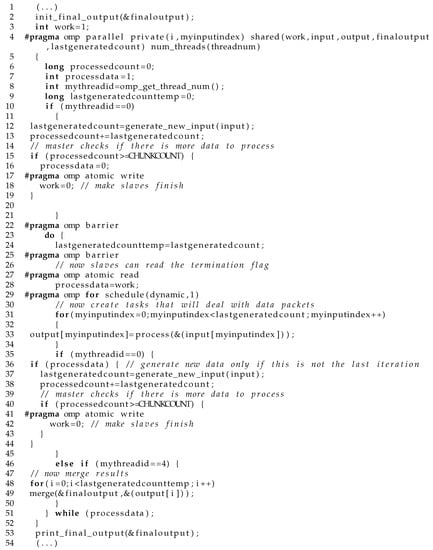

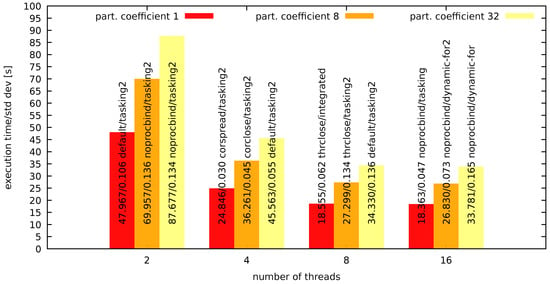

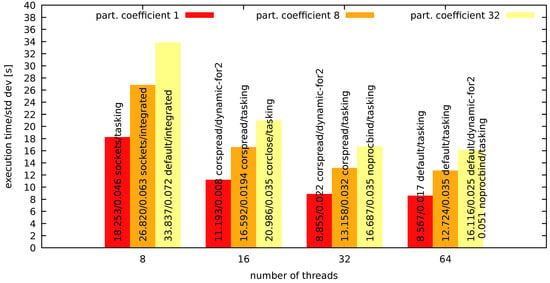

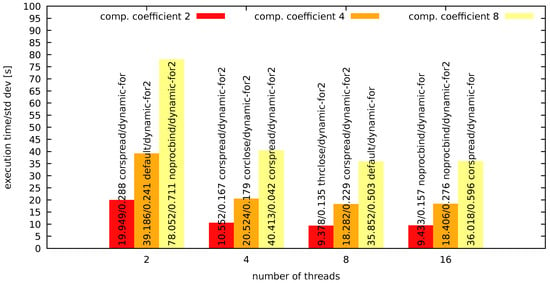

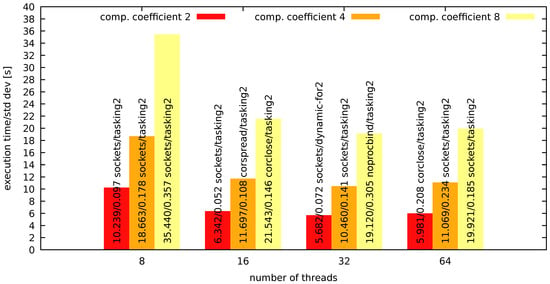

Additionally, for the coefficients, execution times and corresponding standard deviation values are shown for various numbers of threads. These are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7 for numerical integration as well as in Figure 8 and Figure 9 for image recognition.

Figure 6.

Numerical integration—system 1 results for various numbers of threads.

Figure 7.

Numerical integration—system 2 results for various numbers of threads.

Figure 8.

Image recognition—system 1 results for various numbers of threads.

Figure 9.

Image recognition—system 2 results for various numbers of threads.

4.4. Observations and Discussion

4.4.1. Performance

From the performance point of view, based on the results the following observations can be drawn and subsequently be generalized:

- For numerical integration, best implementations are tasking and dynamic-for2 (or dynamic-for for system 1) with practically very similar results. These are very closely followed by tasking2 and dynamic-for and then by visibly slower integrated-master and designated-master.

- For image recognition best implementations for system 1 are dynamic-for2/dynamic-for and integrated-master with very similar results, followed by tasking, designated-master and tasking2. For system 2, best results are shown by dynamic-for2/dynamic-for and tasking2, followed by tasking and then by visibly slower integrated-master and designated-master.

- For system 2, we can see benefits from overlapping for dynamic-for2 over dynamic-for for numerical integration and for both tasking2 over tasking, as well as dynamic-for2 over dynamic-for for image recognition. The latter is expected as those configurations operate on considerably larger data and memory access times constitute a larger part of the total execution time, compared to integration.

- For the compute intensive numerical integration example we see that best results were generally obtained for oversubscription, i.e., for tasking* and dynamic-for* best numbers of threads were 64 rather than generally 32 for system 2 and 16 rather than 8 for system 1. The former configurations apparently allow to mitigate idle time without the accumulated cost of memory access in the case of oversubscription.

- In terms of thread affinity, for the two applications best configurations were measured for default/noprocbind for numerical integration for both systems and for thrclose/corspread for system 1 and sockets for system 2 for smaller compute coefficients and default for system 1 and noprocbind for system 2 for compute coefficient 8.

- For image recognition, configurations generally show visibly larger standard deviation than for numerical integration, apparently due to memory access impact.

- We can notice that relative performance of the two systems is slightly different for the two applications. Taking into account best configurations, for numerical integration system 2’s times are approx. 46–48% of system 1’s times while for image recognition system 2’s times are approx. 53–61% of system 1’s times, depending on partitioning and compute coefficients.

- We can assess gain from HyperThreading for the two applications and the two systems (between 4 and 8 threads for system 1 and between 16 and 32 threads for system 2) as follows: for numerical integration and system 1 it is between 24.6% and 25.3% for the coefficients tested, for system 2 it is between 20.4% and 20.9%; for image recognition and system 1, it is between 10.9% and 11.3% and similarly for system 2 between 10.4% and 11.3%.

- We can see that ratios of best system 2 to system 1 times for image recognition are approx. 0.61 for coefficient 2, 0.57 for coefficient 4 and 0.53 for coefficient 8 which means that results for system 2 for this application get relatively better compared to system 1’s. As outlined in Table 1, system 2 has larger cache and for subsequent passes more data can reside in the cache. This behavior can also be seen when results for 8 threads are compared—for coefficients 2 and 4 system 1 gives shorter times but for coefficient 8 system 2 is faster.

- integrated-master is relatively better compared to the best configuration for system 1 as opposed to system 2—in this case, the master’s role can be taken by any thread, running on one of the 2 CPUs.

The bottom line, taking into consideration the results, is that preferred configurations are tasking and dynamic-for based ones, with preferring thread oversubscription (2 threads per logical processor) for the compute intensive numerical integration and 1 thread per logical processor for memory requiring image recognition. In terms of affinity, default/noprocbind are to be preferred for numerical integration for both systems and thrclose/corspread for system 1 and sockets for system 2 for smaller compute coefficients and default for system 1 and noprocbind for system 2 for compute coefficient 8.

4.4.2. Ease of Programming

Apart from the performance of the proposed implementations, ease of programming can be assessed in terms of the following aspects:

- code length—the order from the shortest to the longest version of the code is as follows: tasking, dynamic-for, tasking2, integrated-master, dynamic-for2 and designated-master,

- the numbers of OpenMP directives and functions. In this case the versions can be characterized as follows:

- designated-master—3 directives and 13 function calls;

- integrated-master—1 directive and 6 function calls;

- tasking—4 directives and 0 function calls;

- tasking2—6 directives and 0 function calls;

- dynamic-for—7 directives and 0 function calls;

- dynamic-for2—7 directives and 1 function call,

which makes tasking the most elegant and compact solution. - controlling synchronization—from the programmer’s point of view this seems more problematic than the code length, specifically how many distinct thread codes’ points need to synchronize explicitly in the code. In this case, the easiest code to manage is tasking/tasking2 as synchronization of independently executed tasks is performed in a single thread. It is followed by integrated-master which synchronizes with a lock in two places and dynamic-for/dynamic-for2 which require thread synchronization within #pragma omp parallel, specifically using atomics and designated-master which uses two locks, each in two places. This aspect potentially indicates how prone to errors each of these implementations can be for a programmer.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Within the paper, we compared six different implementations of the master–slave paradigm in OpenMP and tested relative performances of these solutions using a typical desktop system with 1 multi-core CPU—Intel i7 Kaby Lake and a workstation system with 2 multi-core CPUs—Intel Xeon E5 v4 Broadwell CPUs.

Tests were performed for irregular numerical integration and irregular image recognition with three various compute intensities and for various thread affinities, compiled with the popular gcc compiler. Best results were generally obtained for OpenMP task and dynamic for based construct implementations, either with thread oversubscription (numerical integration) or without oversubscription (image recognition) for the aforementioned applications.

Future work includes investigation of aspects such as the impact of buffer length and false sharing on the overall performance of the model, as well as performing tests using other compilers and libraries. Furthermore, tests with a different compiler and OpenMP library such as using, e.g., icc -openmp would be practical and interesting for their users. Another research direction relates to consideration of potential performance-energy aspects of implementations in the context of CPUs used and configurations, also when using power capping as an extension of previous works in this field [29,30,31]. Finally, investigation of performance of basic OpenMP constructs for modern multi-core systems and compilers is of interest, as an extension of previous works such as [32,33].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Czarnul, P. Parallel Programming for Modern High Performance Computing Systems; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, M.; Supinski, B.R. (Eds.) OpenMP Application Programming Interface Specification Version 5.0; OpenMP Architecture Review Board: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1795759885. [Google Scholar]

- Ohberg, T.; Ernstsson, A.; Kessler, C. Hybrid CPU–GPU execution support in the skeleton programming framework SkePU. J. Supercomput. 2019, 76, 5038–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstsson, A.; Li, L.; Kessler, C. SkePU 2: Flexible and Type-Safe Skeleton Programming for Heterogeneous Parallel Systems. Int. J. Parallel Program. 2018, 46, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augonnet, C.; Thibault, S.; Namyst, R.; Wacrenier, P.A. StarPU: A unified platform for task scheduling on heterogeneous multicore architectures. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2011, 23, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, A.; Cohen, A. OpenStream: Expressiveness and data-flow compilation of OpenMP streaming programs. ACM Trans. Archit. Code Optim. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, A.; Cohen, A. A Stream-Computing Extension to OpenMP. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on High Performance and Embedded Architectures and Compilers, HiPEAC ’11, Crete, Greece, 24–26 January 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Amer, A.; Balaji, P.; Bordage, C.; Bosilca, G.; Brooks, A.; Carns, P.; Castelló, A.; Genet, D.; Herault, T.; et al. Argobots: A Lightweight Low-Level Threading and Tasking Framework. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2018, 29, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.D.; Ramos, L.; Góes, L.F.W. PSkel: A stencil programming framework for CPU-GPU systems. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2015, 27, 4938–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balart, J.; Duran, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Martorell, X.; Ayguade, E.; Labarta, J. Skeleton driven transformations for an OpenMP compiler. In Proceedings of the 11th Workshop on Compilers for Parallel Computers (CPC 04), Chiemsee, Germany, 7–9 July 2004; pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bondhugula, U.; Baskaran, M.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Ramanujam, J.; Rountev, A.; Sadayappan, P. Automatic Transformations for Communication-Minimized Parallelization and Locality Optimization in the Polyhedral Model; Compiler Construction; Hendren, L., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnul, P. Parallelization of Divide-and-Conquer Applications on Intel Xeon Phi with an OpenMP Based Framework. In Information Systems Architecture and Technology: Proceedings of 36th International Conference on Information Systems Architecture and Technology—ISAT 2015—Part III; Swiatek, J., Borzemski, L., Grzech, A., Wilimowska, Z., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A.; Beltran, V.; Martorell, X.; Badia, R.M.; Ayguadé, E.; Labarta, J. Task-Based Programming with OmpSs and Its Application. In Euro-Par 2014: Parallel Processing Workshops; Lopes, L., Žilinskas, J., Costan, A., Cascella, R.G., Kecskemeti, G., Jeannot, E., Cannataro, M., Ricci, L., Benkner, S., Petit, S., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 601–612. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, R.; Casas, M.; Moretó, M.; Chasapis, D.; Ferrer, R.; Martorell, X.; Ayguadé, E.; Labarta, J.; Valero, M. Evaluating the Impact of OpenMP 4.0 Extensions on Relevant Parallel Workloads. In OpenMP: Heterogenous Execution and Data Movements; Terboven, C., de Supinski, B.R., Reble, P., Chapman, B.M., Müller, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesko, J.; Mateo, S.; Teruel, X.; Beltran, V.; Martorell, X.; Badia, R.M.; Ayguadé, E.; Labarta, J. Task-Parallel Reductions in OpenMP and OmpSs. In Using and Improving OpenMP for Devices, Tasks, and More; DeRose, L., de Supinski, B.R., Olivier, S.L., Chapman, B.M., Müller, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, J.; Vidal, M.; Filgueras, A.; Álvarez, C.; Jiménez-González, D.; Martorell, X.; Ayguadé, E. Breaking master–slave Model between Host and FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming, PPoPP ’20, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 February 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongarra, J.; Gates, M.; Haidar, A.; Kurzak, J.; Luszczek, P.; Wu, P.; Yamazaki, I.; Yarkhan, A.; Abalenkovs, M.; Bagherpour, N.; et al. PLASMA: Parallel Linear Algebra Software for Multicore Using OpenMP. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2019, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Lara, P.; Catalán, S.; Martorell, X.; Usui, T.; Labarta, J. sLASs: A fully automatic auto-tuned linear algebra library based on OpenMP extensions implemented in OmpSs (LASs Library). J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 138, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmider, H. Shared-Memory Programming Programming with OpenMP; Ontario HPC Summer School, Centre for Advance Computing, Queen’s University: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjidoukas, P.E.; Polychronopoulos, E.D.; Papatheodorou, T.S. OpenMP for Adaptive master–slave Message Passing Applications. In High Performance Computing; Veidenbaum, A., Joe, K., Amano, H., Aiso, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 540–551. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Schmider, H.; Edgecombe, K.E. A Hybrid Double-Layer master–slave Model For Multicore-Node Clusters. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 385, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, C.; Süß, M. Observations on MPI-2 Support for Hybrid Master/Slave Applications in Dynamic and Heterogeneous Environments. In Recent Advances in Parallel Virtual Machine and Message Passing Interface; Mohr, B., Träff, J.L., Worringen, J., Dongarra, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Scogland, T.; de Supinski, B. A Case for Extending Task Dependencies. In OpenMP: Memory, Devices, and Tasks; Maruyama, N., de Supinski, B.R., Wahib, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.K.; Chen, P.S. Automatic scoping of task clauses for the OpenMP tasking model. J. Supercomput. 2015, 71, 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Hager, G. A Proof of Concept for Optimizing Task Parallelism by Locality Queues. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0902.1884. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnul, P. Programming, Tuning and Automatic Parallelization of Irregular Divide-and-Conquer Applications in DAMPVM/DAC. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 2003, 17, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijkhout, V.; van de Geijn, R.; Chow, E. Introduction to High Performance Scientific Computing; lulu.com. 2011. Available online: http://www.tacc.utexas.edu/$\sim$eijkhout/istc/istc.html (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Eijkhout, V. Parallel Programming in MPI and OpenMP. 2016. Available online: https://pages.tacc.utexas.edu/$\sim$eijkhout/pcse/html/index.html (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Czarnul, P.; Proficz, J.; Krzywaniak, A. Energy-Aware High-Performance Computing: Survey of State-of-the-Art Tools, Techniques, and Environments. Sci. Program. 2019, 2019, 8348791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywaniak, A.; Proficz, J.; Czarnul, P. Analyzing Energy/Performance Trade-Offs with Power Capping for Parallel Applications On Modern Multi and Many Core Processors. In Proceedings of the 2018 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Poznań, Poland, 9–12 September 2018; pp. 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Krzywaniak, A.; Czarnul, P.; Proficz, J. Extended Investigation of Performance-Energy Trade-Offs under Power Capping in HPC Environments; 2019. In Proceedings of the High Performance Computing Systems Conference, International Workshop on Optimization Issues in Energy Efficient HPC & Distributed Systems, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, A.; Getov, V.; Chapman, B. Performance Comparisons of Basic OpenMP Constructs. In High Performance Computing; Zima, H.P., Joe, K., Sato, M., Seo, Y., Shimasaki, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Berrendorf, R.; Nieken, G. Performance characteristics for OpenMP constructs on different parallel computer architectures. Concurr. Pract. Exp. 2000, 12, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).