Hunting in Extremadura—Profiles of the Hunter on the Basis of His Movements

Abstract

1. Introduction

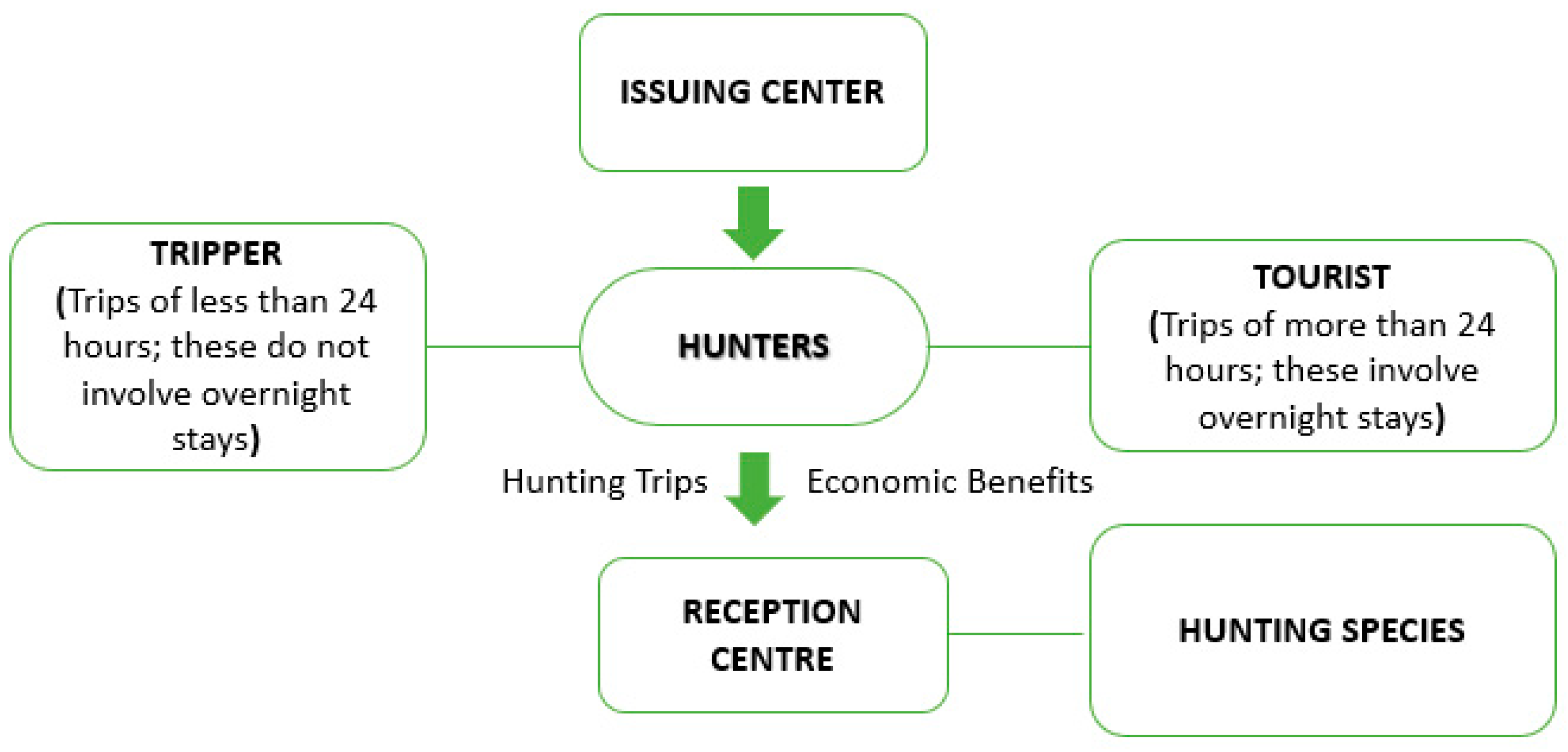

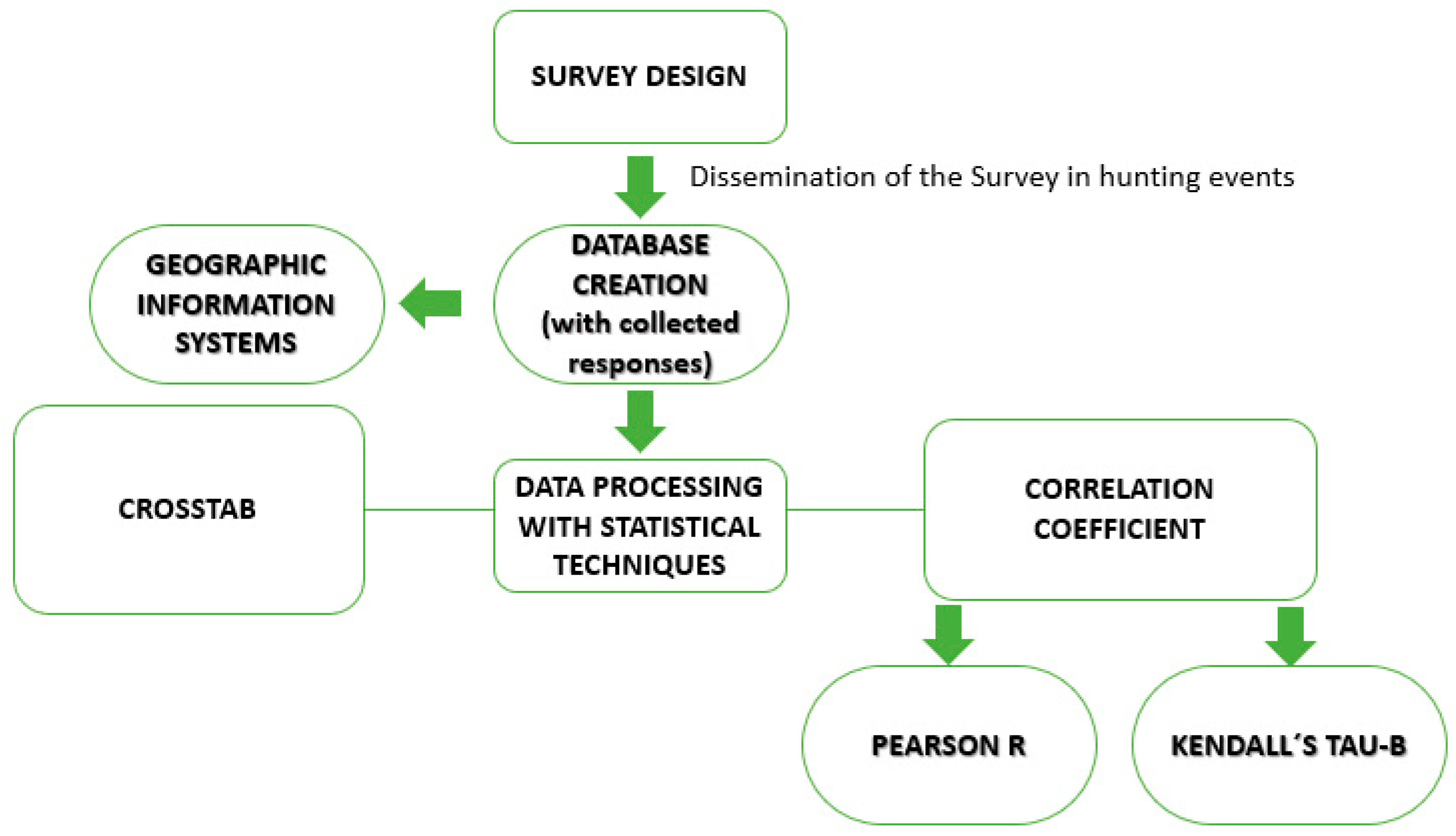

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Differences between the Hunter-Tripper and the Hunter-Tourist Resident in Extremadura

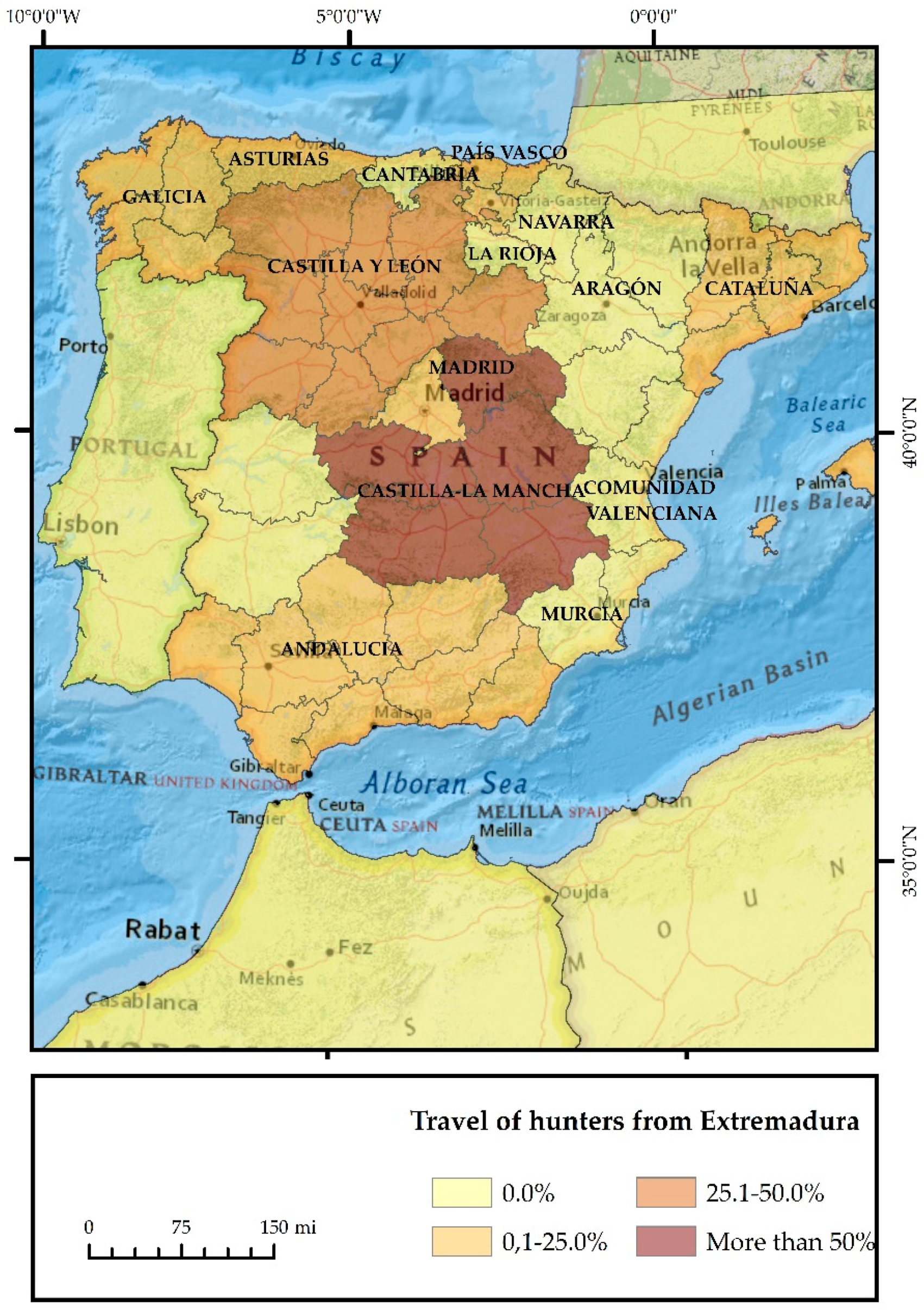

3.2. Major Hunting Destinations of the Hunter from Extremadura

3.3. Hunting Types

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- From a socioeconomic perspective, it can be appreciated that few women are to be found in either profile, even though it should be specified that their presence is increasing in the sample of hunting tourists.

- As far as age is concerned, the profile is that of a mature hunter with few under 26 years of age.

- As for movements during the hunting season, a large proportion of the hunters of the sample declare that they travel more than 30 days. During this large number of days, the hunting tourist stays overnight, spending between 1 and 10 days away from home. These overnight stays take place in various types of tourist accommodation, in particular in rural accommodation and hotels from 1 to 3 stars.

- Hunters tend to travel in company. Trips with friends and family stand out.

- The journeys of hunters from Extremadura during the 2018/2019 hunting season generated considerable income with certain differences between the two traveller profiles detected. The average expense per person incurred by the hunting tripper amounted to 800 €. The figure increases to 1182 € in the case of the hunting tourist. These data reveal the role played by hunting as an economic activity and the considerable income it contributes in tourist destinations.

- Lastly, as far as practising the main types of hunting is concerned, no major differences were found between both types of travellers. The prominence of individual pursuit and hunting parties should be emphasised.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montoya, M.I. La caza en el medievo peninsular. Revista Electrónica de Estudios Filosóficos 2003, 3. Available online: https://www.um.es/tonosdigital/znum6/portada/Cazamur.htm (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Valverde, J.A. Anotaciones al Libro de la Montería del rey Alfonso XI; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2009; Volume 82. [Google Scholar]

- López Ontiveros, A. Algunos aspectos de la evolución de la caza en España. Agricultura y Sociedad 1991, 58, 13–53. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/bitstream/handle/10396/5594/a058_01.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Bauer, J.; Herr, A. Hunting and fishing tourism. In Wildlife Tourism, Impacts, Management and Planning; Common Ground Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 57–78. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40871766 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- León, P.; Marías, D. El turismo cinegético. Abaco Revista de Cultura y Ciencias Sociales 2007, 54, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A.; Buck, W.J. La España Inexplorada; Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes: Sevilla, Spain, 1989; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Rengifo Gallego, J.I. La oferta de Caza en España en el contexto del turismo cinegético internacional: Las especies de caza mayor. Ería 2008, 53–68. Available online: https://www.unioviedo.es/reunido/index.php/RCG/issue/view/168/showToc (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation; U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Falls Church, VA, USA, 2017; p. 24. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/wsfrprograms/subpages/nationalsurvey/nat_survey2016.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- European Federation for Hunter. Available online: https://www.face.eu/2016/09/hunting-in-europe-is-worth-16-billion-euros/ (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Federation of Associations for Hunting and Conservation of the EU (FACE); Pinnet, J.M. The Hunters in Europe. Report; 1995; p. 12. Available online: https://www.kora.ch/malme/05_library/5_1_publications/P_and_Q/Pinet_1995_The_hunters_in_Europe.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Danzberjer, J.B. La caza: Un elemento esencial en el desarrollo rural. Mediterráneo Económico: El nuevo Sistema Agroalimentario en una Crisis Global. 2009, Volume 15, pp. 183–203. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/da63/600e9da6a5526375ec04bdde003393409bf9.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Lindsey, P.A.; Roulet, P.A.; Romanach, S.S. Economic and conservation significance of the trophy hunting industry in sub-Saharan Africa. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 134, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călina, A.; Călina, J.; Miluț, M.; Stan, I. Research on the practice of rural tourism specialized in sport and image hunting in Cergău area, Romania. Agrolife Sci. J. 2018, 7, 18–24. Available online: http://www.agrolifejournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.VII_1/Art2.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Martín-Delgado, L.M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. Hunting Tourism as a Possible Development Tool in Protected Areas of Extremadura, Spain. Land 2020, 9, 86. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030086 (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Saayman, M.; van der Merwe, P.; Saayman, A. The economic impact of trophy hunting in the south African wildlife industry. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, e00510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Weaver, L.C.; Diggle, R.W.; Matongo, G.; Stuart-Hill, G.; Thouless, C. Complementary benefits of tourism and hunting to communal conservancies in Namibia. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, P.; Pérez, J.L.C.; Solano, S.E.; Román, C.P. El turismo cinegético: Una oportunidad sostenible para el turismo rural. Tour. Hosp. Int. J. 2015, 4, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tello-Leyva, Y.M.; Vázquez-Herrera, S.E.; Juárez-Reina, A.; González-Pérez, M. Turismo cinegético: Una alternativa sustentable? Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 20. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/44029083/5949-17470-1-PB.pdf?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DTURISMO_CINEGETICO_UNA_ALTERNATIVA_DE_DE.pdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A%2F20200317 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Mbaiwa, J.E. The socio-economic benefits and challenges of a community-based safari hunting tourism in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Tour. Stud. 2004, 15, 1–14. Available online: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=200501357;res=IELAPA;type=pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Mbaiwa, J.E. Effects of Safari hunting tourism ban on rural livelihoods and wildfile conservation in Northern Botswana. S. Afr. Geograph. J. 2018, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, E.; Stage, J. The size and distribution of the economic impacts of Namibian hunting tourism. Afr. J. Wildlife Res. 2007, 37, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humavindu, M.N.; Barnes, J.I. Trophy hunting in the Namibian economy: an assessment. S. Afr. J. Wildlife Res. 24 Month Delayed Open Access 2003, 33, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Muposhi, V.K.; Gandiwa, E.; Bartels, P.; Makuza, S.M. Trophy hunting, conservation, and rural development in Zimbabwe: issues, options, and implications. Int. J. Biodivers. 2016, 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, V.R. The Contribution of Hunting Tourism: How Significant is Th is to National Economies. In Contribution of Wildlife to National Economies; Joint Publication of FAO and CIC: Budapest, Hungary, 2010; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Bielsa, J. La caza mayor como alternativa de desarrollo en zonas deprimidas de Extremadura. In Comunicaciones con motivo del I Congreso Internacional de caza en Extremadura; de Extremadura, J., La caza en Extremadura, Eds.; Diputacion Provincial de Cáceres: Cáceres, Spain, 1987; pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, A.; Tibebe Weldesemaet, Y.; Czajkowski, M.; Tadie, D.; Hanley, N. Trophy hunters’ willingness to pay for wildlife conservation and community benefits. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas-Rolfes, M. African wildlife conservation and the evolution of hunting institutions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, J.M. Caza y espacios naturales protegidos en Extremadura. Investigaciones Geográficas 2016, 65, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader-Williams. Recreational Hunting, Conservation; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 386. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, B. Tourism and the Consumption of Wildlife: Hunting, Shooting and Sport Fishing; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- Heffelfinger, J.R.; Geist, V.; Wishart, W. The role of hunting in North American wildlife conservation. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 70, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Minin, E.; Leader-Williams, N.; Bradshaw, C.J. Trophy hunting does and will support biodiversity: a reply to Ripple et al. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, P.; Garel, M.; Bourgoin, G.; Dubray, D.; Maillard, D.; Loison, A. Impacts of tourism and hunting on a large hervibore´s spatio-temporal behavior in and around a French protected area. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 177, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, C.; Brink, H.; Kissui, B.M.; Maliti, H.; Kushnir, H.; Caro, T. Effects of trophy hunting on lion and leopard populations in Tanzania. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueras, J.J.R.; Caridad, J.M.; Gálvez, J.C.P. El perfil del turista cinegético: un estudio de caso para Córdoba (España). Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 187–203, 2386-8570. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, L.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; y Sánchez, J.M. El turista cinegético. Una aproximación a su perfil en la comunidad autónoma de Extremadura. Investigaciones turísticas de la Universidad de Alicante 2019, 18, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrón, M. De la panorámica de la caza en Extremadura. C. Orellana (edit). Los libros de la caza española 1975, 473–520. [Google Scholar]

- Terrón, M. De la Extremadura agreste: Notas para un estudio de la evolución histórica de la fauna de caza mayor. In La caza en Extremadura; Diputación de Cáceres: Cáceres, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado Corrales, E. Los espacios rurales y el ocio. Los Cotos de caza. In VIII Coloquio de Geógrafos Españoles. Comunicaciones; Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles: Barcelona, Spain, 1983; pp. 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, E. La caza en Extremadura. Un recurso poco conocido. Agroexpo 1990, 3, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado Corrales, E. Socieconomía de la caza. El ejemplo extremeño. In Manual de Ordenación y Gestión Cinegética; Formatex: Badajoz, Spain, 1991; pp. 21–54. Available online: www.dialnet.uniroja.es (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Alvarado Corrales, E. La actividad cinegética en Extremadura. Agricultura y Sociedad 1991, 58, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, S.; y García, M. Extremadura, Tradición de la Caza; Patronato de turismo de la Diputación Provincial de Cáceres: Madrid, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional (2019): Base Topográfica Nacional 1:100 0000. Available online: http://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Gallardo, M.; Rodero, S.; Gómez, M.; Gallardo, J.M.; Arroyo, V.; Durán, J.A. Situación de la caza en Extremadura: Informe Anual Temporada 2016/17; Federación Extremeña de caza: Badajoz, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://cazawonke.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/INFORME-ANUAL-CAZA.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Morales, P.; Rodríguez, L. Aplicación de los coeficientes correlación de Kendall y Spearman. In Barquisimeto; Universidad Centroccidental Lisandro Alvarado: Venezuela, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre, A.; Payeras, M. Diferencias en el perfil del turista de la temporada alta y baja. In XVIII Reunión Anual Asepelt 2004; Universitat de Les Illes Balears: Palma, Spain, 2004; Available online: https://scholar.google.es/scholar?hl=es&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=47.%09Sastre%2C+A.%3B+Payeras%2C+M.+Diferencias+en+el+perfil+del+turista+de+la+temporada+alta+y+baja.+In+XVIII+Reuni%C3%B3n+Anual+Asepelt+2004%3B+Universitat+de+Les+Illes+Balears%3A+2004.&btnG= (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Arizón, M.J.B.; Garcés, S.A.; Sangrá, M.M. Perfil del turista de festivales: el caso del Festival Internacional de las Culturas Pirineos Sur. Cuadernos de Turismo 2012, 30, 63–90. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10201/29319 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Folgado, J.A. y Hernández. El perfil del turista de eventos culturales: análisis exploratorio. Cultura, desarrollo y nuevas tecnologías: VII Jornadas de investigación. 2014, pp. 57–74. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/77064/El%20perfil%20del%20turista%20de%20eventos%20culturales.pdf;jsessionid=C07CDD8E165CC6F629690C1790C75BA2?sequence=1 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Junta de Extremadura. Plan General de Caza en Extremadura; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Mexico, 2015; Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/files/Informacion%20Publica/2015/octbre/Anteproyecto%20PGCEx%20-%20optimizado.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Andueza, A.; Lambarri, M.; Urda, V.; Prieto, I.; Villanueva, L.F.; Sánchez-García, C. Evaluación del Impacto Económico y Social de la Caza en Castilla-La Mancha; Fundación Artemisan: Ciudad Real, Spain, 2016; p. 76. Available online: https://www.fundacionartemisan.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Resumen-Ejecutivo.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Consejería de Medio Ambiente y Rural, Políticas Agrarias y Territorio. ORDEN de 21 de agosto de 2017 General de Vedas de Caza para la temporada 2017/2018, de la Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura. 2017. Available online: http://doe.gobex.es/pdfs/doe/2017/1630o/17050355.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Consejería de Agricultura, Desarrollo Rural, Medio Ambiente y Energía. DECRETO 91/2012, de 25 de mayo, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento. 2012. Available online: http://doe.gobex.es/pdfs/doe/2013/1040o/13040100.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Consejo Económico y Social, de. Reto demográfico y equilibrio territorial en Extremadura; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Mexico, 2019; p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, L.M.; Rengifo, J.I. y Sánchez, J.M. El modelo de caza social: evolución y caracterización en Extremadura. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 82, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic/Economic Profile | Movements of the Hunter | Types of Hunting |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Places where you hunt | What types of small game hunting do you practise? |

| Age | How many days do you travel to hunt away from your place of residence? | What types of big game hunting do you practise? |

| Place of Residence | Can you estimate the number of days you stay away from your place of residence during hunting trips? | How regularly do you hunt in public reserves? |

| Level of Studies | What type of accommodation do you choose for these overnight stays? | How regularly do you hunt in private reserves? |

| Employment Situation | Who do you travel with? | Are you a member of a local hunting association? |

| Monthly Income | Do you carry out activities other than hunting on these trips? | |

| Average Spending on Trip- | Expense of hunting trips during the last season |

| Background | 38,273 hunting licences issued in Extremadura (2018) |

| Sample Size | 354 completed surveys |

| Sampling | Random sample |

| Truthfulness Level | 95% |

| Type of Survey | Questionnaire on paper and online distributed at various hunting events and through Google Drive. |

| Sampling Error (p = q = 0.50; p = q = 0.90) | 5.2%; 3.1% |

| Date of Completion | 15 September 2018 to 15 September 2019 |

| Monthly Income (€) | Nights Spent Away from Your Place of Residence (%) | Association Measurements (Correlations) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1–5 | 6–10 | Over 10 N | Pearson R | Kendall tau-b | ||

| Less than 1000 | 53.0 | 28.9 | 6.0 | 12.1 | 83 | 0.283** | 0.226** |

| 1001–1500 | 45.1 | 35.9 | 11.3 | 7.7 | 142 | ||

| 1501–2000 | 28.6 | 38.8 | 24.5 | 8.1 | 49 | ||

| 2001–2500 | 30.8 | 34.6 | 11.5 | 23.1 | 26 | ||

| Over 2500 | 14.3 | 34.3 | 14.3 | 37.1 | 35 | ||

| Where Do You Hunt? | |||||||

| Only in the municipality where you live | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 0.540** | 0.488** |

| In the municipality where you live and in others of your autonomous region | 56.7 | 34.2 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 120 | ||

| In your autonomous region and in others | 22.0 | 44.1 | 18.6 | 15.3 | 145 | ||

| In Spain and other countries | 16.3 | 16.3 | 18.6 | 48.8 | 43 | ||

| How Often Do You Hunt in Public Reserves? | |||||||

| Never | 27.9 | 23.3 | 25.6 | 23.2 | 43 | −0.341** | −0.313** |

| Sometimes | 19.4 | 35.5 | 19.3 | 25.8 | 62 | ||

| Habitually | 35.5 | 40.0 | 13.6 | 10.9 | 110 | ||

| Always | 59.9 | 29.9 | 3.1 | 7.1 | 127 | ||

| How Often Do You Hunt in Private Reserves? | |||||||

| Never | 83.9 | 12.9 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 31 | 0.311** | 0.292** |

| Sometimes | 54.0 | 35.0 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 100 | ||

| Habitually | 27.8 | 38.6 | 16.1 | 17.5 | 137 | ||

| Always | 33.7 | 27.3 | 15.6 | 23.4 | 77 | ||

| Level of Significance | *0.05 | **0.01 | |||||

| Sex | Tripper (%) | Tourist (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 4.1 | 7.8 |

| Male | 95.9 | 92.2 |

| Age Group | ||

| Under 18 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| 18–25 | 14.2 | 11.7 |

| 26–40 | 16.9 | 40.3 |

| 41–55 | 41.9 | 24.7 |

| 56–65 | 16.9 | 17.0 |

| Over 65 | 7.4 | 3.9 |

| Level of Studies | ||

| Low | 52.0 | 34.0 |

| Intermediate | 31.1 | 27.2 |

| Higher education | 16.9 | 38.8 |

| Employment Situation | ||

| Student | 10.8 | 6.8 |

| Unemployed | 10.8 | 2.0 |

| Working for an employer | 34.5 | 44.7 |

| Civil servant | 8.8 | 9.2 |

| Self-employed | 23.6 | 26.2 |

| Retired | 11.5 | 9.7 |

| Other | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| Monthly Income (€) | ||

| Under 1000 | 29.7 | 19.0 |

| 1001–1500 | 43.2 | 37.9 |

| 1501–2000 | 10.1 | 17.0 |

| 2001–2500 | 5.4 | 8.7 |

| Over 2500 | 3.5 | 14.5 |

| Don´t Know/No Answer/Refused | 8.1 | 2.9 |

| Tripper (%) | Tourist (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| In the municipality in which you live and in others of your autonomous region | 62.4 | 25.9 |

| In your autonomous region and in others | 29.4 | 56.2 |

| In Spain and in other countries | 6.4 | 17.9 |

| Don´t Know/No Answer/Refused | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| How Many Days Do You Travel Per Season to Hunt? | Tripper (%) | Tourist (%) |

| 1–10 | 23.7 | 12.1 |

| 11–20 | 13.5 | 17.0 |

| 21–30 | 16.2 | 13.6 |

| Over 30 | 35.1 | 57.3 |

| DK/NA/REF | 11.5 | 0.0 |

| Overnight Stays | Tourist (%) | |

| 1–5 | 56.8 | |

| 6–10 | 20.4 | |

| Over 10 | 22.8 | |

| Type of Tourist Accommodation | Tourist (%) | |

| Private house of friends or relatives | 25.2 | |

| Casa rural | 30.1 | |

| Rural hotel | 24.8 | |

| 1- to 3-star hotel | 35.5 | |

| 4- to 5-star hotel | 12.1 | |

| Tourist apartment | 6.8 | |

| On the estate where you hunt | 11.2 | |

| Other | 17.0 | |

| Who do you Travel With? | Tripper (%) | Tourist (%) |

| Friends | 32.4 | 67.0 |

| Family | 18.6 | 30.1 |

| Alone | 11.0 | 11.7 |

| As a couple | 1.4 | 18.0 |

| Other | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| DK/NA/REF | 13.1 | 0.0 |

| Activities Other than Hunting | ||

| None | 57.9 | 16.1 |

| Gastronomic tourism | 15.9 | 46.8 |

| Rural tourism | 10.3 | 40.0 |

| Visits to protected natural spaces | 2.1 | 17.6 |

| Cultural visits | 2.1 | 25.4 |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| DK/NA/REF | 15.2 | 3.4 |

| Average expense per person | 800 € | 1182 € |

| Frequency of Hunting in Public Reserves | Tripper (%) | Tourist (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 8.1 | 15.0 |

| Sometimes | 8.8 | 24.3 |

| Habitually | 26.4 | 34.5 |

| Always | 51.4 | 24.7 |

| DK/NA/REF | 5.3 | 1.5 |

| Frequency of Hunting in Private Reserves | ||

| Never | 17.6 | 2.4 |

| Sometimes | 36.5 | 22.3 |

| Habitually | 26.4 | 48.1 |

| Always | 17.5 | 24.8 |

| DK/NA/REF | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Do You Belong to a Local Hunters’ Association? | ||

| Yes | 87.2 | 67.5 |

| No | 12.8 | 32.0 |

| DK/NA/REF | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Types of Small Game Hunting | ||

| Individual or group pursuit | 73.5 | 71.9 |

| Fixed stand | 49.0 | 60.8 |

| Fox hunting | 37.4 | 41.7 |

| Dogs in a burrow | 26.5 | 23.1 |

| Beating small game in limited areas | 24.5 | 36.7 |

| Releasing for immediate shooting | 15.0 | 31.2 |

| Partridge beating | 12.9 | 23.6 |

| Partridge with decoy | 10.2 | 14.6 |

| With greyhounds and other dogs for pursuit | 6.1 | 8.6 |

| Types of Big Game Hunting | ||

| Hunting party | 68.7 | 77.9 |

| Waiting | 44.9 | 59.3 |

| Beating | 41.5 | 45.2 |

| Beating in limited areas | 30.6 | 39.7 |

| Stalking | 19.0 | 36.7 |

| Bow and arrow | 1.4 | 0.5 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín-Delgado, L.-M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. Hunting in Extremadura—Profiles of the Hunter on the Basis of His Movements. Resources 2020, 9, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9040046

Martín-Delgado L-M, Rengifo-Gallego J-I, Sánchez-Martín J-M. Hunting in Extremadura—Profiles of the Hunter on the Basis of His Movements. Resources. 2020; 9(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín-Delgado, Luz-María, Juan-Ignacio Rengifo-Gallego, and José-Manuel Sánchez-Martín. 2020. "Hunting in Extremadura—Profiles of the Hunter on the Basis of His Movements" Resources 9, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9040046

APA StyleMartín-Delgado, L.-M., Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I., & Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. (2020). Hunting in Extremadura—Profiles of the Hunter on the Basis of His Movements. Resources, 9(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9040046