Abstract

This article is devoted to the study of the role of natural cryogenic resources in the traditional subsistence systems of the people of Russia. The main source of the actual information and the empirical basis reflecting the features of traditional ecological knowledge of the ethnic groups considered in the article are the scientific publications and ethnographic descriptions made by Russian researchers in the second half of the 19th century through to the beginning of the 21st century, and the results of our modern field research in the territory of Siberia and the Far East of Russia. The methodology of the study lies in the field of ethnoecology, and contains comparative and typological approaches, which have allowed for the detection and systematization of the main spheres of using natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems by the people of Russia, which include using the environment for indigenous subsistence, building materials, food preservation, obtaining potable water, the irrigation of crops, etc. In conclusion, some of the prospective for the ethnoecological examination of the role of the natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems were designated, and adaptations to modern innovative technologies based on the rational use of natural resources were also examined.

1. Introduction

Due to the prevalence of a cold climate and being situated in the Arctic latitudes, most of Russia has a unique variety of different natural phenomena connected with low temperatures. More than 65% of the Russian Federation is situated in permafrost, the top layer of the Earth’s crust with frozen grounds. Snowfall and the freezing of rivers and lakes in the winter period and part of the off-season are characteristic of most parts of Russia. Therefore, the cryogenic conditions of Northern Asia have affected the traditional culture and economic activity of the people who live in this area. However, this situation still has not been systematically investigated by modern science. The reason for this lies in long-existing stereotypes, according to which the low temperatures and cryogenic phenomena have been considered adverse and dangerous for people. Therefore, the problems regarding how to protect mankind from the influences of the cryosphere seemed to be more relevant for science. Understanding that the Earth’s cryosphere plays a key role in maintaining balance in global climatic processes, landscapes, and ecosystems only began to develop at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries due to an increase in the societal attention to the problem of global warming. This situation has changed the axiological paradigm of the perception of cold. Today, it is more often considered as a source of cryogenic resources, whose role in the development of mankind has still not been fully comprehended yet [1]. Changes in the interest that the scientific and public consciousness have in regarding the cold have included its value in traditional subsistence and land use. These researches have been mainly developed in ethnoecology.

Ethnoecology began to develop as an independent scientific study in the United States (USA) and Europe in the second half of the 20th century. Pioneering works in the field of ethnoecology include those by American ethnologists and anthropologists such as Konklin, Freyk, etc. [2,3]. One of the key concepts of ethnoecology is subsistence. This refers to the reproduction of some elements of practical skills (agriculture, livestock breeding, hunting, gathering, etc.) and material culture (constructions, clothes, food, means of labor), which are used for the maintenance of the vital activity of people [4] (pp. 8–9). In turn, a subsistence system is “an interconnected complex of production activity features, demographic structure, settlement patterns, labor cooperation, traditions of consumption and distribution, i.e., ecologically caused forms of social behavior which provide to any human collective existence by using of natural resources.” [5] (p. 15). Since 1980, ethnoecological studies have often used the concept Traditional Ecological Knowledge [6], which is defined as “a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment.” [7] (p. 1252).

A number of fields that study the adaptation of ethnic groups to some physiographic areas, climatic conditions, and landscapes have developed in ethnoecology and include studies of the ethnoecological aspects of using traditional subsistence systems of certain natural resources. Conditionally, this field of research can be defined as resource ethnoecology. Today, most of the scientific works in this field are devoted to local features of agricultural economic activity where the emphasis is placed on the human consumption of certain biological resources. The use of natural inorganic substances in traditional cultures has been considerably less studied. Thus, natural cryogenic resources have been very insufficiently considered as an object of specialized research in the field of ethnoecology.

The central object of this research is the traditional ecological knowledge and subsistence systems of the people of Russia where the usage of natural cryogenic resources has played an important role. This article has the following main goals:

- -

- To consider from a retrospective look at how this problem was covered in the Russian scientific literature during the period from the second half of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st century;

- -

- To detect and systematize the main spheres of using natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems by the people of Russia; and

- -

- To define the general opportunities, prospects, and scopes of studying the role of natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems.

2. Materials and Methods

In this article, the traditional ecological knowledge connected with the use of natural cryogenic resources is considered among two conditional groups of the population of Russia:

- Indigenous people of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation (Khanty, Mansi, Nenets, Komi, Yakuts, Chukchi, Eskimos, etc.) living in tundra, forest–tundra, and taiga, who are engaged in reindeer breeding, hunting, and fishing.

- The East Slavic people (Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians) living in regions with a temperate climate in taiga, mixed woods, and forest–steppes zones who are engaged in agriculture.

The research area covers the Asian part of Russia, and includes macro regions such as the Ural, Siberia, and the Far East.

The main source of the actual information and empirical basis reflecting the features of traditional ecological knowledge of the ethnic groups considered in this article are the scientific publications and ethnographic descriptions made by Russian researchers in the second half of the 19th century through to the beginning of the 21st century [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. In this research, the results of our previous studies were also used, which were based on the field research in the territory of Siberia and the Far East of Russia, which took place between 2010 and 2018 [28,29,30,31,32]. Most of these works have been published only in Russian, and therefore remain poorly known worldwide. As a result, the main aim of this article was to introduce them into international scientific circulation. In this article, the data on the traditional ecological knowledge of the different ethnic groups, which have been published in these sources, were subjected to analysis through the application of comparative and typological approaches.

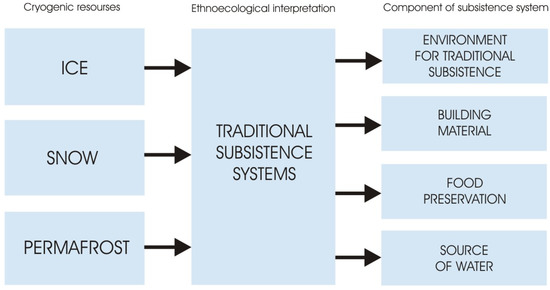

The research hypothesis considered cryogenic resources including their interpretations within the context of the ethnoecological studies as components of the traditional subsistence systems of the different people and ethnic groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research conceptual framework.

3. Results

3.1. Cryogenic Resources and Environment for Traditional Subsistence

The most important environmental value of cryogenic resources is connected to the functions of ice, snow, and permafrost, which create conditions for sustainable life and the traditional subsistence of local communities. The active layer of permafrost is an environmental component that provides the stability of landscapes that are suitable for the lives and activities of humans in the North. Investigating the ethnoecology of nomadic reindeer people (the Komi and Nenets), Istomin and Habeck noted that “permafrost affects the nomads directly, for the herders have to take into account the probability of thermokarst while choosing the campsite and performing certain herding procedures. It also affects the herders indirectly, through its influence on landscape and vegetation and thus on reindeer behavior. More rapid permafrost degradation will have a range of adverse effects on reindeer herding.” [24] (p. 1). In the winter, the nomadic routes of Nenets reindeer herders can lie quite a long distance from reservoirs since humans and deer obtain water for subsistence from the snow. In the case of an absolutely snowless winter, the lack of at least one cryogenic resource can lead to the destruction of the traditional subsistence system that has developed among the nomadic reindeer-herders. The formation of an ice crust does not give a wintering herbivore the chance to get a subsnow forage, leading to their mass deaths [16] (p. 9). Therefore, for all kinds of Arctic animals, winter warming may be much more dangerous than extremely cold air temperatures [5] (p. 129).

In the Arctic regions of Russia, winter roads called zimnik are widely used, which were often the only transportation routes for these vast areas [26] (p. 1603). Global warming can significantly reduce the season of operation of such winter roads. Changes to the cryogenic conditions (the modes of freezing and thawing of soils and reservoirs) significantly influence the activity as well as the migration routes of many animals and fishes, thus also affecting the stability of the traditional subsistence systems of indigenous people of the North. During an ice drift, the movement of ice often influences the formation of riverbeds, changes the landscapes along them, thus affecting the environmental activity of people and their planning of the settlements situated along the rivers [33] (p. 6). The large-scale anthrax epidemic that took place at Yamal in the summer of 2016 showed one of the more insufficiently studied environmental role of cryogenic resources. According to the estimates of experts, the temperature anomaly that promoted an increase in the depth of the seasonal thawing of the active layer of permafrost and the subsequent movement of anthrax to the surface of the soil through underground waters could have been the reason behind the epidemic [25]. This situation indicates the insufficiently studied protective functions of the cryosphere from a number of biological dangers.

All of these examples show that for the Arctic indigenous people who preserve traditional forms of land use, the development of cross-disciplinary criteria for an ethnoecological examination, assessment, and forecast of the environmental value of the natural cryogenic recourses for the balance of ecosystems, and the establishment of their connection to kinds of anthropogenic activity is of great importance. Its methodology requires field research for the study of traditional subsistence systems of local communities as well as monitoring the condition changes of cryogenic objects and processes.

3.2. Building Material

Using ice and snow as basic building materials or as a part of building construction takes place in regions with the coldest climates. One of the best-known examples of such constructions is the winter dwellings of the Inuit and some other indigenous people of Canada and Greenland, which is known as the igloo. An igloo is a dome-shaped shelter built from blocks made of snow or ice built by the Inuit, but not by other indigenous people of Northeast Asia [15] (p. 44). The people of Siberia and the Far East of Russia have mostly used ice and snow as additional building materials. Russian ethnographer Bogoraz, V.G. described the traditional semi-underground dwelling of the tribe of Chukchi Kereк, whose framework was constructed of wooden poles on which the turf was laid, “since autumn it becomes covered by a thick snow layer in several feet of thickness, it is given the round or rectangular form that makes it similar to the Eskimo snow house.” [23] (p. 117). For the Russian population of the North of Siberia until the end of the 19th century, ice was widely used instead of windowpanes [17] (p. 118). The Mansi living nearby also used ice in a similar way [22] (p. 122).

In ethnographic descriptions of the life of the people of Siberia, it is also possible to find references regarding the use of snow and ice for the building of seasonal supporting or wind-shelter constructions. In many Russian villages, snow was used as a material for warming the dwelling. For these purposes, in the winter, a snow embankment was constructed on the windward side of a building. One additional traditional form of the use of snow and ice as a building material is for the construction of temporal shelters. Most often, these were used by hunters in the tundra or taiga. In the traditional culture of Russians, the creation of buildings from snow was used for games and entertainment. Snow fortresses used to be built for games at the Russian traditional festival Maslenitsa, which took place at the beginning of spring [18].

In the first half of the 20th century, due to the development of engineering geocryology, scientists became interested in the use of cryogenic resources as a main building material. In some cases, the sources of the technical ideas that researchers tried to apply in industrial technologies lay in traditional ecological knowledge. In the United States, the military and participants of polar expeditions studied the practice of igloo construction. In the Soviet Union, during World War II in the winter time, snow and ice were often used for the creation of temporary shelters, fortification constructions, and also false buildings masking military constructions [11] (p. 27). In the 1930s and 1940s, Soviet engineer Krylov, M.M. actively developed technologies for the construction of storage where ice served simultaneously as a main building material and a cold source [14] (p. 43).

3.3. Use of Cryogenic Resources for Food Preservation

The use of natural cold is the most ancient method of food preservation. Neanderthals stored the meat of animals obtained from hunting in holes dug in frozen soil [31] (p. 136). In the traditional culture of different peoples throughout the millennia, various methods of using natural cryogenic resources for the storage of food have arisen. Their principles were defined both by the features of the climate and natural landscapes as well as the technological skills that were available to mankind at different stages of its history.

The climatic conditions of Siberia and the Far East of Russia affected the development of skills related to the cooled and frozen storage of food among all of the people living in the area. Investigating the traditional ecological culture of the indigenous Khanty and Nenets people living in the North of Western Siberia, Adaev, V.A. noted that regarding the use of natural weather conditions, the freezing of food in cellars or freezing holes was widely applied among them [21] (p. 109). Forest Nenets in the summertime dug wells for the storage of meat, fish, and berries. The depth of a well reached the permafrost layer, and was between 1.5 to 2 m. To strengthen the walls of a well, boards or the branches of trees were used. In some cases, ice or snow was put in a well for the best cooling of products. For thermal insulation, moss was used. A heavy item was put on the wooden cover of a well so that wild animals could not reach the food. In the winter time, Forest Nenets stored perishable food hanging on trees, on narty (Nenets sledge), and also in wooden constructions on piles named labaz. In the spring time, during snow thawing, Tundra Nenets added some salt to their fish or meat and put them on snow where they were preserved until summer [20] (p. 63). On the Gydan Peninsula, Nenets stored the meat of deer in holes with snow near their settlements. On their route of autumn nomadic movement, they would often leave some products in holes in snow with a tag [19] (p. 136–137). Indigenous people of the Far East of Russia such as the Chukchi have used underground storage where their walls are supported by whale bones [23] (p. 117).

Most Russians and other East Slavs living in the agricultural area of Siberia and the Far East of Russia use a cellar named lednik for the storage of perishable food. Most often, a lednik had of depth from 2 m up to 5 m. In the spring, a lednik was filled with ice or snow, which could be from one third to half of its volume [30], and was covered from above with thick wooden flooring. As a rule, ice or snow in a lednik did not thaw during the summertime, thus allowing the storage of meat, fish, milk, and other perishable foodstuffs for a long time. In the traditional rural estates of Russians, a lednik was often situated under wooden farm buildings [29]. A lednik could also be dug in the yard of an estate under an easy canopy or in a shadow of trees [17] (p. 131). In some settlements, the design of a lednik included special wooden compartments for snow or ice. In others, ice or snow was put on the soil bottom of a lednik, which absorbed the thawing water. In this case, the food, stored in a lednik, put in from above. An important part of the device of a lednik was its heat insulation. Different regions used straw, sawdust, peat and other materials for this purpose [32].

The people of the North of Russia used natural cryogenic resources not only for storage, but also to prepare certain types of food. Most often, they were used for the preparation of native fish dishes. Among such indigenous northern people such as the Khanty, Mansi, Nenets, Yakuts, etc., stroganina—fresh-frozen fish cut by thin plates which are eaten with salt—has wide popularity. Besides strogonina, Nenets eat the fresh-frozen meat of deer, and Yakuts eat frozen horse meat [27] (p. 267). Before the wide distribution of salt, an archaic way of preparing fish by most of the indigenous people of the North of Russia was to ferment it in holes dug in the permafrost. Fish was kept within a hole, and berries (cranberry, cowberry, cloudberries, etc.) were put between the layers of fish before the hole was covered with soil from above [12] (p. 673).

In the traditional cuisine of the Yakuts, a dish named tar had a wide distribution. Tar was prepared from turned sour milk and stored in the winter in a frozen condition in the yard of the house. Yakuts used defrosted tar in food as the main dish and as an ingredient for the preparation of porridges and other dishes. In the winter, when the diet became limited, tar was an important source of nutrients for the Yakuts [27] (p. 265).

3.4. A Resource for Getting Potable Water and Irrigation of Crops

In traditional subsistence systems of the people living in the territory of the Arctic regions and mountain areas, snow and ice play an important role as a source of potable water. Each of these people has criteria for the suitability of snow or ice for its use by the person. For example, in the Khanty language, there is a special definition of the snow suitable for use as potable water. This snow has to sparkle and be friable, which testifies to its purity and the suitability of the water for use in food, respectively. Indigenous people of Chukchi kept a special vessel filled with ice for getting thawed water in their dwelling [23] (p. 121). Among the Yakuts, the preparation and storage in the winter time of ice for its use as a source of potable water had a wide distribution [27] (p. 268).

In the traditional culture of Russians since ancient times, there were methods connected with the rational use of winter atmospheric precipitation in agriculture. The first scientific works devoted to the adaptation of this traditional ecological knowledge to solve the practical problems of agronomics began to appear in Russia in the second half of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th centuries. In 1871, the outstanding Russian climatologist Voyeykov, A.I. published the pioneering article, “Influence of a Snow Surface on Climate”, where questions on the value of snow in environmental management were studied [8]. The sufficient volume of snow cover, aside from being a moisture source, protected the soil from deep frost penetration that allowed the growth in Siberia of winter crops for bread (wheat, rye) [16] (p. 3). Gritsanov, P.K. noted that winter snowfall had an even bigger value in the economy, than the rainfall of spring and summer [9] (p. 1). The researcher explained this with the fact that unlike summer rainfall, winter snowfall was less subjected to evaporation and moisture, and gets to the soil during their thawing in the winter, which most often has a decisive influence on the productivity of crops. At the same time, it was noted that they almost entirely remained at the disposal of people who could manage the volumes of moisture intake to the soil [9] (p. 6). Russian agronomists have developed a number of rules for the effective use of winter snowfall in agriculture including plowing fields at perhaps more depth in autumn, therefore creating an uneven ploughland that will allow snow trapping and the creation of obstacles for the outflow of waters in spring. For the detention of snow, sowing high-stalk plants including sunflower, corn and sorghum was recommended [9] (p. 11). Snow plowing was a widespread way of trapping winter atmospheric precipitation on the fields. Another means of snow trapping was the creation of artificial barriers including detaining strips that could be made from brushwood or wooden boards, soil, snow or ice embankments, straw sheaves, and also by planting trees or bushes [9] (p. 21). In the spring, acceleration of snowmelt was reached by ashes being strewn on the snow cover, which allowed for the absorption of more sunshine [16] (p. 23). Traditional methods of snow trapping have gained a wide distribution in the south of Eastern Siberia due to the frequent lack of winter atmospheric precipitation there. In many cases, these methods have been introduced by migrants from southern Russia and Ukraine where similar traditional ecological knowledge have been used due to the features of the local climatic conditions. In the steppe areas of Southern Siberia and Northern Kazakhstan, the lack of water often led to a snezhnik—a small artificial reservoir which filled with water in spring from snowdrifts created in advance—being dug in the ground [13] (pp. 293–294).

Thus, snow cover can be considered as an important component of the traditional subsistence systems of the people of Siberia and the Far East of Russia that is connected to receiving water for domestic and economic needs.

3.5. Other Scopes of Use

In the traditional subsistence systems of the people of Siberia and the Far East of Russia, natural cryogenic resources have had some other uses. The condition of snow cover and tracks on it has since ancient times provided the indigenous people of the tundra and Russian hunters with information about the movement of animals and people [10] (p. 110). The natural cold had a wide use in traditional hygiene, with the principle based on the impact of low temperatures on the interior of a dwelling or was used for the extermination of insects and parasites on the clothes of humans [28].

4. Discussion

An analysis of the Russian scientific literature of the second half of the 19th to the beginning of the 21st centuries allows us to allocate a few periods of study of the role of natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems. During the first period (from the second half of the 19th century up to the 1950s), the use of traditional ecological knowledge in fields of economic activity such as food preservation, construction and agriculture dominated research interest [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. For the second half of the 20th century, Russian science has seen a typical decrease in the interest in this topic due to the wide development of industrial technologies for cooled food preservation, crop irrigation, etc. At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries due to global warming and an increase in the interest in indigenous subsistence, studies of the environmental values of natural cryogenic recourses have been developed [21,24,26,27,28,31]. If we compare this situation with the modern global trends, we can see that in the USA, Canada, Greenland, and Nordic countries, there has been a wide development in the study of the environmental value of natural cryogenic resources in the context of studying indigenous subsistence [34,35], changes in the hydrological regime [36,37,38], and Arctic tourism [39]. Research into using natural cryogenic resources in agriculture have been mostly relevant for Canada and some countries of Northern and Eastern Europe [40]. At the same time, for the worldwide scientific community, many details of traditional constructions for food preservation, and also the practices of using of natural cryogenic resources as auxiliary building materials or hygiene tools still remain largely unknown.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of the review of traditional ecological knowledge, presented in this article, allowed us to select some prospective fields of study into the role of natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems. The first of these fields has to provide answers to the questions about the impact of the existence or absence of any kind of natural cryogenic resource on the stability of the traditional subsistence system of some local communities including indigenous people. The examples given above show that in traditional subsistence systems of the East Slavic rural settlements in the territory of Siberia and the Far East of Russia, natural cryogenic resources played an important role only in certain components connected to agriculture and food preservation. Therefore, we can conclude that for Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, the absence or insignificant quantity of natural cryogenic resources was not critical for the reproduction of their traditional subsistence systems. For example, the lack of snowfall in regions with a warm climate where East Slavs lived caused them to use the methods of rain or flood irrigation and storage of meat and fish by smoking or other ways of conservation that did not require low temperatures in their traditional subsistence systems. Another situation can be observed in the Arctic indigenous people, where for them, a change in the typical seasonal aggregate states that at least one environmental cryogenic resource can be critical for the function of their traditional subsistence system.

According to model forecasts, the average annual air temperature in the northern regions of Russia could increase by 1.5–2.5 °C by the year 2030; by up to 4 °C to the middle of the 21st century; and may exceed 5 °C at the end of the 21st century. At the same time, there is a predicted increase of precipitation volume of 10–15% by the year 2030. This will significantly reduce the stability of landscapes. By the end of the 21st century, about 50% of the area of the modern permafrost zone may have completely melted [41]. Russian researchers see the following destructive consequences of these climate changes for indigenous subsistence:

- -

- A decrease in the areas for reindeer herding and changes to the traditional nomadic routes of indigenous peoples due to bogging of the tundra, changes of vegetation, formation of an ice crust, and other permanent or seasonal transformations of the Arctic landscapes [5,24];

- -

- A change and shift to the North of the flora and fauna habitat areas, and a decrease in the population of Arctic animals and fishes. This situation can significantly break the Arctic ecosystems and have a negative impact on indigenous subsistence [42,43]. Being able to access traditional food resources and ensuring food security can be a major challenge in an Arctic affected increasingly by climate change and global processes [43] (p. 658).

- -

- A reduction in the period of transport connections on winter roads and an increase in difficult transport connections in the off-season. This situation may become a reason for the isolation of small northern settlements and can compel their inhabitants to leave them [42] (p. 127). It can also deprive the spatial mobility of hunters and gatherers [44] (p. 74).

- -

- The growth of infectious diseases of people and animals connected with the loss of the protective properties of the active layer of permafrost and displacement to the North of causative agents from areas of disease [45].

Therefore, we can conclude that people living in the Arctic zone are a lot more dependent on natural cryogenic resources than people living in areas with a temperate climate. This situation defines the main fields of the ethnoecological examination of the role of natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems. Under its close attention, there have to be traditional forms of environmental management by the local communities. In addition, this examination has to include monitoring the global changes and rhythmic fluctuations of climate influencing cryogenic processes such as winter atmospheric precipitation, changes of the mode of frost penetration or thawing of reservoirs, frozen soils, and underground ice. The research methods applied in modern ethnology including studying the traditional forms of subsistence by specialized polls as well as the statistical analysis of the indicators reflecting the dynamics of indigenous land use are relevant to studying the ecological behavior of the population of the North. The results of these studies have to be compared with the data from monitoring changes in the surrounding cryogenic conditions. The organization of such an examination may have a high predictive value. In particular, being guided by the forecast of changes in cryogenic conditions, it is possible to warn of a number of critical situations that threaten the functioning of the traditional subsistence systems of indigenous people. Geographic information systems (GIS) analyzing the dependence of the dynamics of cryogenic conditions to traditional subsistence systems and indigenous land use can be used as a main tool for regional ethnoecological examination.

The second important field of studying the role of natural cryogenic resources in subsistence systems is to search for possible ways to adapt traditional ecological knowledge to modern innovative technologies. The urgency of this field has been caused by the consumption crisis of natural and energy resources by mankind. For example, today we can observe the growth of interest in natural cryogenic recourses as a source of fresh water. This is relevant not only for the Arctic territory, but also for regions with a temperate climate and mountainous areas that could profit from using snow amelioration and obtaining potable water from ice or snow. Considering crisis tendencies in the consumption of electric power, the use of natural cryogenic resources in industrial technologies for the cooled preservation of food could achieve high economic efficiency again. Studying the traditional experiences of the different ethnic groups connected to methods of food preservation by using the natural cold is very important in solving problems. At the same time, it would be wrong to use this field of study only to literally return to archaic methods of economic activity. The modern achievements in the creation of new construction materials with high heat-insulating properties provides a chance to create hi-tech cooling systems for industry that can mostly utilize the natural cold. For regions with permafrost, standard storage cooled by underground cold could have great economic efficiency.

Thus, we conclude that the traditional ecological knowledge of using of natural cryogenic resources in subsistence systems cannot be considered only as relics of culture that have lost their practical value. Due to the key role of the Earth’s cryosphere in many global ecological processes, this experience, which has been developed for many centuries, is extremely important for the survival of the Arctic indigenous people as well as for the creation of new eco-friendly technologies based on the rational use of natural resources.

Funding

This research was funded by the State assignment (research program No. IX.135.2.2) and by contract of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (No. 14.587.21.0048).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Melnikov, V.; Gennadinik, V.; Kulmala, M.; Lappalainen, H.K.; Petäjä, T.; Zilitinkevich, S. Cryosphere: A kingdom of anomalies and diversity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 6535–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, H. An ethnoecological approach to shifting agriculture. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1954, 17, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frake, C. Cultural Ecology and Ethnography. Am. Anthropol. 1962, 64, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arutyunov, S.A.; Markaryan, E.S. Culture of Subsistence and Ethnos; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1983. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Krupnik, I.I. Arctic Ethnoecology; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1989. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Traditional Ecological Knowledge in perspective. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases; Canadian Museum of Nature: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1993; pp. 1–9. ISBN 1-895926-00-9. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voeykov, A.I. Influence of the snow surface on the climate. Izv. Russk. Geogr. obshc. 1871, 7, 64–68. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gratsianov, P.K. On the Significance and Ways of Accumulation of Snow in the Fields and the Hold of Winter Precipitation; T-vo I.D. Sytina: Moscow, Russia, 1911. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tobolyakov, V.T. To the Headwaters of the Disappeared River; Rabotnik Prosveshcheniya: Sverdlovsk, Russia, 1930. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Chekotillo, A.M. Using of Snow, Ice and Frozen Soils for Construction Purposes; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1945. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M.G.; Potapov, L.P. Peoples of Siberia: Ethnographic Essays; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1956. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tokarev, S.A. East Slavic Ethnographic Collection; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1956. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Chekotillo, A.M. Accumulators of cold. Tekhn. Molod. 1959, 2, 43–44. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Menovshchikov, G.A. Eskimo; Magadanskoe Knizhnoe Izdatel’stvo: Magadan, Russia, 1959. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rikhter, G.D. Snow and Its Use; Znanie: Moscow, Russia, 1960. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov, V.A. Ethnography of the Russian Peasantry of Siberia in the 17th–Middle of the 19th Centuries; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1981. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunov, B.V. Traditional competitions for possession of a snow fortress-town as an element of the Russian folk culture. Etnogr. Obozr. 1994, 5, 103–115. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Acusi, E. Culture of Food of Gyda Nenets (Interpretation and Social Adaptation); Izdatelstvo Instituta Antropologii I Etnologii RAN: Moscow, Russia, 1997. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Haruchi, G.P. Traditions and Innovations in the life of Nenets Ethnos; Izdatelstvo Tomskogo Universitera: Tomsk, Russia, 2001. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Adaev, V.N. Traditional Ecological Culture of the Khanty and the Nenets; Vektor Buk: Tyumen, Russia, 2007. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bogordaeva, A.A. On Russian borrowings in Mansi dwelling (historiographic review after materials of 18 c.—early 21 c.). Vestn. Arkh. Antrop. Etnograf. 2015, 4, 122–129. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bogoraz, V.G. Chukchi: Material Culture; LENAND: Moscow, Russia, 2016. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Istomin, K.V.; Habeck, J.O. Permafrost and indigenous land use in the Northern Urals: Komi and Nenets reindeer husbandry. Polar Sci. 2016, 10, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.Y.; Demina, Y.V.; Ezhlova, E.B.; Kulichenko, A.N.; Ryazanova, A.G.; Maleev, V.V. Outbreak of Anthrax in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District in 2016, Epidemiological Peculiarities. Probl. Part. Danger. Infect. 2016, 4, 42–46. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A.A. “The Resources of Cold” in Economic and Socio-Cultural Practices of Rural Communities of Yakutia. The second half of XIX—Early XX centuries. Bylye Gody 2018, 50, 1601–1611. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A.A. “Cold Resources” in Food System of Yakuts: Traditions and Present Day. Nauchn. Dialog 2018, 2, 263–274. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V.; Gennadinik, V.; Fedorov, R. Humanitarian aspects of cryosophy. Kriosf. Zemli Earth’s Cryosphere 2016, 20, 112–117. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, R.; Lysenko, D.; Abolina, L. “A cellar with superstructure”: Domestic constructions for storage of food of 17–20th centuries (Angara and Yenisey region). In Culture of Russians in Archeological Researches; Nuka: Omsk, Russia, 2017; pp. 357–363. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, R. Innovations with history in thousands of years. KholodOK 2017, 15, 63–74. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov, V.; Fedorov, R. The role of natural cryogenic resources in traditional subsistence systems of the peoples of Siberia and the Far East. Tomsk State Univ. J. 2018, 1, 133–141. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanov, A.; Fedorov, R.; Andronov, S.; Kochkin, R.; Bogdanova, E.; Kobelkova, I.; Popov, A.; Lobanova, L. The constructions for storage of fish using cryogenic resources of the Arctic zone of Western Siberia. KholodOK 2018, 16, 75–83. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov, V.P. The newest phenomena, concepts, tools as the foundation for starting to new horizons of cryology. Kriosf. Zemli Earth’s Cryosphere 2012, 16, 3–9. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Koivurova, T.; Tervo, H.; Stepien, A. Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic, Background Paper, Arctic Centre and Arctic Transform. 2008. Available online: https://arctic-transform.eu/download/IndigPeoBP.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2018).

- Ferris, E.A. Complex Constellation: Displacement, Climate Change and Arctic Peoples. 2013. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/30-arctic-ferris-paper.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2018).

- Vorobyev, S.N.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Serikova, S.; Manasypov, R.M.; Krickov, I.V.; Shirokova, L.S.; Lim, A.; Kolesnichenko, L.G.; Kirpotin, S.N.; Karlsson, J. Permafrost Boundary Shift in Western Siberia May Not Modify Dissolved Nutrient Concentrations in Rivers. Water 2017, 9, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.A.; Fowler, R.A.; Northington, R.M.; Malik, H.I.; McCue, J.; Saros, J.E. How Does Changing Ice-Out Affect Arctic versus Boreal Lakes? A Comparison Using Two Years with Ice-Out that Differed by More Than Three Weeks. Water 2018, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y. Effects of Permafrost Degradation on the Hydrological Regime in the Source Regions of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, China. Water 2017, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, B.W. “An ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure”: Adopting Landscape-Level Precautionary Approaches to Preserve Arctic Coastal Heritage Resources. Resources 2017, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, K.J.; Keys, C.N. The effect of snow trapping and cropping sequence on moisture conservation and utilization in West-Central Saskatchewan. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1981, 61, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drovdov, D.S.; Malkova, G.V.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Vasiliev, A.A.; Leibman, M.O.; Sadurtdinov, M.R.; Ponomareva, O.E.; Pendin, V.V.; Gorobtsov, D.N.; Ustinova, E.V.; et al. Digital maps of permafrost zone and assessment of current trends of cryosphere changes. In 11th International Symposium on Problems of Engineering Permafrostology; MPI SB RAS: Yakutsk, Russia, 2017; pp. 233–234. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Medvedkov, A.A. Mid-Taiga Geosystems of the Yenisei Siberia under Climate Change; MAKS Press: Moscow, Russia, 2016. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall, M.; Berkes, F.; Forbes, B.; Kofinas, G.; Vlassova, T.; Wenzel, G. Hunting, Herding, Fishing, and Gathering: Indigenous Peoples and Renewable Resource Use in the Arctic. In Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 649–690. [Google Scholar]

- Vasleva, A.P. Impact of global warming on welfare of indigenous people in the territory of Sakha (Yakutia) republic. Alm. Sovr. Nauki i Obraz. 2010, 10, 74–75. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Revich, B.A. Climatic changes as a new risk factor for health of the population of Russian North. Ecol. Cheloveka 2009, 6, 11–16. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).