1. Introduction

Tourism is becoming an increasingly important industry in modern economies. It influences economic growth and development at national, state and regional levels. According to Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) [

1], tourism’s share of GDP in Australia was 3% in 2014–2015. The industry was employing more than 580,000 persons (4.9% of total persons employed). Queensland is one of the large tourism states in Australia. Tourism in Queensland makes a strong contribution to the state gross value added, taxes, Gross State Product and employment. Queensland’s contribution to the total national tourism gross value added was the second largest in 2013–2014. Tourism Research Australia (TRA) estimated that Queensland’s contribution to national tourism consumption was 24% in 2013–2014. Queensland made the second largest contribution to total national tourism employment in 2013–2014 [

2].

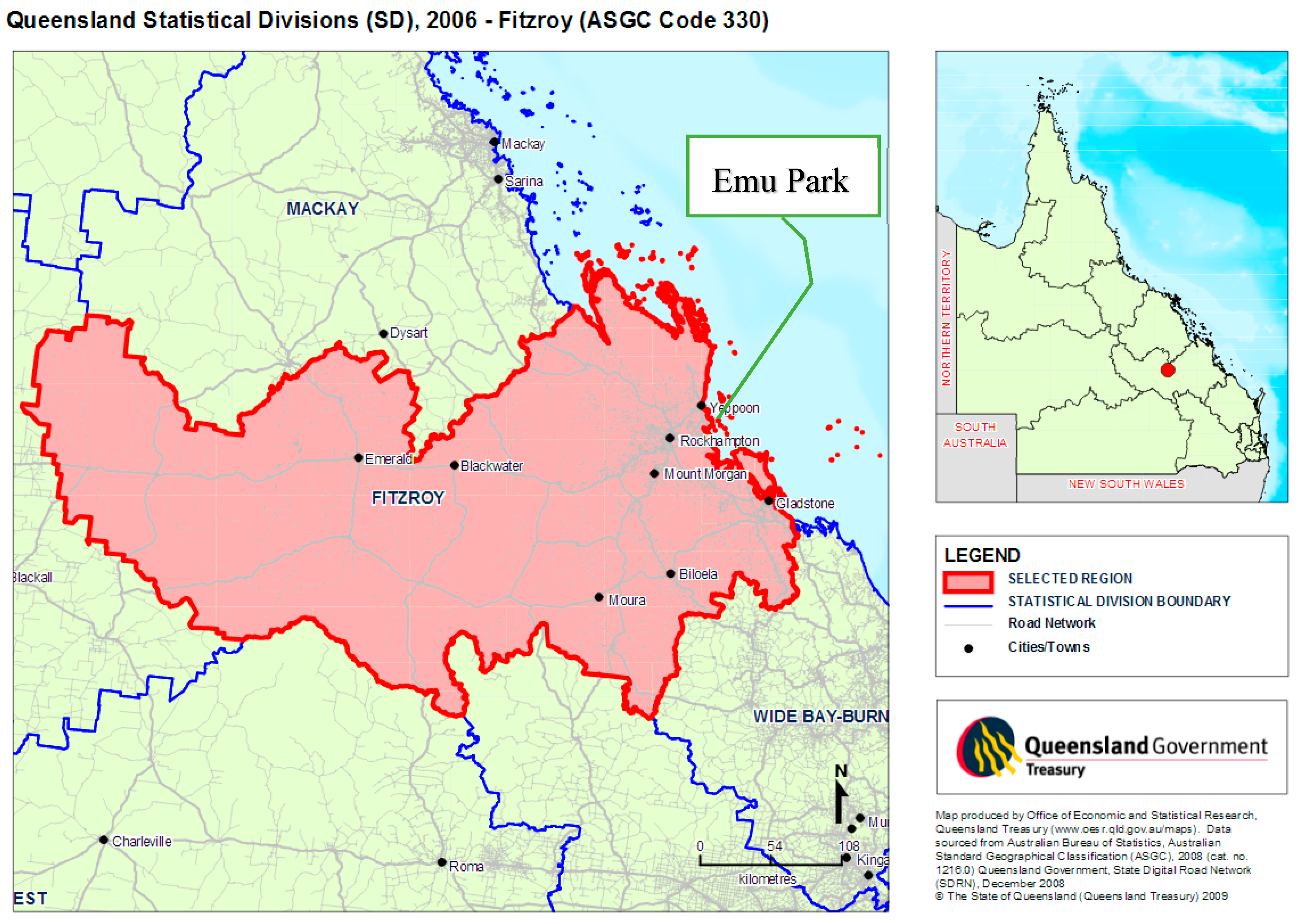

Queensland has 12 tourism regions; each tourism region is made up of a number of Statistical Local Areas (SLAs). The case study of Emu Park (a coastal town) is situated within the Central Queensland tourism region. Central Queensland tourism region can be approximated by Fitzroy Statistical Division (SD) for data collection purposes. Tourism contributes substantially to the Central Queensland region’s economy. However, the share of tourists to the coastal towns of Central Queensland (Yeppoon and Emu Park) was only 12% of the number of tourists to Central Queensland [

3]. Saarinen [

4] noted that tourism can boost economic development in peripheral regions. He suggested integrating tourism with regional development to reduce the uneven social development.

In order to increase tourists’ visits to the coastal area of Central Queensland, the development of the near foreshore area at Emu Park has been proposed by the Livingstone Shire Council. Livingstone Shire Council has proposed to develop the Peace park paths and landscape, Kerr Park path and playground, Tenant Memorial Drive Bus Turnaround, Surf Lifesaving car park and landscape, Emu street re-construction (part) and Foreshore Kiosk. Rolfe et al. [

3] predicted that the proposed new infrastructure and facilities would increase the number of overnight tourists in this region by 20%. They estimated that this increase in the number of overnight visits would provide up to A$12M additional revenue in the Yeppoon and Emu Park region and A$85M additional revenue in the Central Queensland region.

An economic impact assessment of new projects can be done using simple spending multipliers, IO analysis or computable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling. While simple spending multipliers do not provide detailed information about how the effects spread through the economy, IO and CGE modelling can be used to assess the economic impacts in more detail. IO analysis shows the industry interdependence and the effect of the initial stimulus on industries’ production. Some econometric IO models supplement the IO model with econometric equations. The empirical component of the CGE model is an IO table. CGE models are considered to have less limitations than IO models. However, CGE models require much more data than IO models. Required data might not be available at the regional level or at the necessary sectoral disaggregation. Furthermore, CGE models are based on more restrictive assumptions than IO models [

5,

6,

7]. Given the disadvantages of CGE models at the regional level and simplistic nature of spending multipliers, IO analysis was used for the economic impact assessment of proposed development projects at Emu Park for the Fitzroy SD.

This papers discusses how to create more opportunities for the tourism industry to integrate better in the regional economy. It suggests the following methodology of increasing the value of an industry at a regional level. First, an economy under investigation needs to be analysed in terms of key industries. Key industries are those industries whose expansion boosts the economy more (in terms of employment, output, income and value added) than the equal expansion of other industries. Second, the connections among tourism related industries and key industries need to be identified. Third, the strategies to enhance the connections between the tourism industry and key industries need to be discussed with the community and local policy makers to outline the recommendations to increase the value of the tourism industry within the region according to the long-term vision of regional development. In this paper, several techniques are combined to investigate the impacts of additional spending resulted from the Emu Park foreshore development on regional economy. IO multipliers are derived to analyse the interdependency of tourism related industries within the region. Then, the estimated additional tourism expenditure is proportioned according to the Queensland Tourism Satellite Account data. Finally, the potential connections with key sectors within the region are investigated and procurement strategies are suggested to enhance these connections.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 outlines basics of IO analysis with respect to the tourism industry.

Section 3 explains how IO analysis was applied to the case study.

Section 4 describes the case study.

Section 5 presents results from the projects to the regional economy.

Section 6 concludes.

2. Input–Output Analysis with Respect to the Tourism Industry

The IO technique is widely used to understand the structure of economy, the effects of changes in a given industry(s) and/or final demand and a key industry analysis. IO analysis is a descriptive technique used to identify how different industries in the economy interact, and how changes in one industry generates “ripple” effects through the wider economy. These models are used to estimate the flow-on effects of changes in income, value added, expenditure and employment (for more details see [

8]). In the economy, each industry is a seller of its output to other industries and each industry is a purchaser of the outputs from other industries (

Table 1). Value added includes compensation of employees, gross operating surplus and mixed income, and net taxes. Final demand comprises of households and government final consumption expenditure, gross fixed capital formation, changes in inventories and exports.

In IO analysis, A is the matrix of technical (or direct input) coefficients. It is calculated by dividing the transactions for each industry by their respective total output levels (a

ij = x

ij/X

j). The Leontief inverse (or total requirements) matrix is (I-A)

−1, where I is the identity matrix. The Leontief inverse matrix shows the links between the final demand and the industries’ outputs [

8]. IO analysis estimates the effects of the exogenous change on the economy through multipliers effect.

Type I (open model) multipliers include the direct and indirect business spending. A direct increase in business spending results from an increase in final demand for their product. An increase in final demand leads to an increase in production and therefore, an increase in direct business spending (direct impacts). As the business purchases more from their suppliers, the suppliers increase their spending to meet the increased demand (indirect impacts). Type II (closed model) multipliers include direct, indirect spending and household spending (induced impacts) as a result of higher employment and income across all industries. In closed models, households are treated as an industry and are included in the intermediate consumption matrix. In open models, households are excluded from the inter-industry matrix. Disaggregated multipliers for an industry show the effect of initial stimulus from that industry on the direct, indirect and induced impacts for each industry in the intermediate consumption matrix.

IO models were used in a variety of applications assessing the impact of tourism on economic activity [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. For example, Atan and Arslanturk [

14] provided an analysis of the tourism industry in Turkey using IO analysis. They used 15 aggregated sectors and found that the tourism sector makes a significant contribution to Turkey’s economy. Surugiu [

13] used IO analysis to estimate the economic impacts of tourism on the hotel and restaurant sector in Romania. Surugiu [

13] analysed the impacts of hotels and restaurants for 2000 and 2005 and found that output and employment multipliers have increased, but value added and income multipliers had declined in 2005 compared to 2000. The results of linkages analysis have shown that hotels and restaurants have one of the lowest interdependence in the economy. Surugiu [

13] suggested that in order to increase the flow-on effect of the tourism industry, strong transport infrastructure and diversified services are necessary.

Archer and Fletcher [

10], using IO analysis, examined the impact from tourism on income, employment, public sector revenue and the balance of payments in the Seychelles. They used 18 aggregated IO sectors with separate industries related to tourism such as trade, accommodation, restaurants, and land, air and sea transport; that permitted the tourism expenditure patterns to be aligned directly with the relevant sectors of the economy without heavy aggregation. The tourism expenditure data was obtained from the airport exit surveys and the Central Bank of the Seychelles. Archer and Fletcher [

10] stated that the impact from tourism was distributed over several productive sectors with a different magnitude. This information could assist governments to determine which tourist groups maximize the economic benefits and in which sectors tourists should be encouraged to spend.

The tourism industry, however, is not a “classic” input–output sector, but a complex of inter-related and inseparable activities such as travel, accommodation, sightseeing, entertainment and others [

16]. Therefore, the economic impacts of tourism should flow to several industries. Briassoulis [

16] suggested that a modification of the export component of the demand vector, in order to reflect the distribution of tourist spending in the industrial sectors that participate directly in the tourism activity, can overstate the impacts of tourism on regional economy. She suggested accounting for a short-term upwards pricing effect, capacity constraints, varied consumption patterns of different types of visitors and changes in consumption patterns of the local population, in order to obtain more reliable estimates of tourism’s impacts.

Harris [

17] argued that in the application of IO analysis to tourism regional impacts analysis, the estimated employment multipliers are likely to overstate the effect of tourism at the regional level. He noted that an increase in sales does not necessarily lead to the hiring of additional employees. Fleischer and Freeman [

18], however, suggested that results from IO modelling do not estimate the full impact of tourism. Frechtling and Horvath [

11] found that tourism multipliers are relatively high for income and employment but low for output compared with other sectors.

The results from the IO analysis should be taken with caution due to the limitations of the IO technique. The limitations of IO analysis, such as measurement problems and the theoretical basis of IO models are well discussed in the IO literature. The limitations include the fixed production patterns, emphasis on short-term effect, the lack of supply constraints, limited use of interregional feedbacks, industry homogeneity, change in multipliers over time, and substitution effect [

16,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Given that tourism is not a “classic” IO industry, Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSAs) has become popular in assessing the impact of tourism on the economy. TSAs allow to measure the direct economic contributions of tourism to the economy that is consistent with the IO table [

23,

24]. Jones et al. [

25] suggested that the restrictive assumptions underlying IO frameworks and the inadequate representation of tourism as a source of final demand might provide inaccurate estimates of the impacts. TSAs, however, could assist in linking tourism activity to final demand. Dwyer et al. [

26] provided an overview of the TSAs developments by the Centre for Economic Policy in Australia and noted some issue with using IO without taking into consideration the TSAs. Pratt [

24] estimated additional expenditure on each of the tourism related industries using the projected tourism expenditure and the TSAs allocations.

Jones and Munday [

12] examined tourism activity using Welsh IO tables and extended the IO model to comprise a set of TSAs. They aggregated 67 industries to 20 industry sectors, including six tourism related sectors (from TSA). The core tourism sectors were defined as the following:

Hotels and accommodation

Restaurants and other eating places

Bars and public houses

Museums and visitor gardens

Amusement parks, fairs and other tourist attractions

Other recreation activities not elsewhere classified [

12].

Jones and Munday [

12] identified industries that are ancillary to tourism, such as retail trade and distribution and transportation. They suggested that the level of backward linkages (multipliers) varies among tourism-related industries. For example, the local accommodation providers might purchase more in the region than the large national supply chain companies.

However, the application of TSA to IO analysis can be difficult due to data limitations and some methodological issues. For example, Surugiu [

13] stated that TSA is a complex instrument that requires a variety of statistical data, usually collected at a national and state level. Jones et al. [

25] discussed some methodological difficulties in constructing a TSA at the regional level. They noted that the IO framework can be used as a basis for more complex models, including the assessment of the regional tourism activity utilising information derived from a TSA. Jones and Munday [

12] also noted that the IO framework can be utilised to analyse the significance of overall tourism activity at national, state and regional levels, but the scarcity of tourism industry data at the regional level presents a serious issue.

3. An Application of Input–Output Analysis to the Case Study

The economic models in this paper are based on the IO tables for the Australian economy in 2012/2013 with direct allocation of imports [

1] with minor adjustments to account for regional characteristics. The IO table was calibrated by simple location quotients using employment by industry. Then, various data at state (regional) level was used to adjust/check the tables. For example, the output by industry, gross regional product and other indicators were used where appropriate and available. There are 20 industries of the economy considered in the analysis. The industries are:

| 1 | Agriculture, forestry and fishing |

| 2 | Mining |

| 3 | Manufacturing |

| 4 | Electricity, gas, water and waste services |

| 5 | Construction |

| 6 | Wholesale trade |

| 7 | Retail trade |

| 8 | Accommodation and food services |

| 9 | Transport, postal and warehousing |

| 10 | Information media and telecommunications |

| 11 | Financial and insurance services |

| 12 | Rental, hiring and real estate services |

| 13 | Professional, scientific and technical services |

| 14 | Administrative and support services |

| 15 | Public administration and safety |

| 16 | Education and training |

| 17 | Health Care Services |

| 18 | Residential Care and Social Assistance Services |

| 19 | Arts and recreation services |

| 20 | Other services |

Data about the details of potential investment in construction has been provided by the project proponent. For the impacts measured at state and regional levels, the following assumptions for the construction stage have been made:

The existing Building and Construction industry in the National IO table [

1] is representative of construction activity associated with the new developments

The construction is completed within 12 months from the start of the project

100% of the construction workforce is based in Fitzroy SD

There is no offsetting fall in public expenditure elsewhere in the region or state

For the ongoing impacts, the following sectors were considered as being tourism related sectors.

The retail trade sector (7), including fuel, food, motor vehicles and parts retailing.

The accommodation and food services sector (8), including accommodation and food and beverage services.

The transport, postal and warehousing sector (9), including road, rail, water, air and other transport, postal and courier services and transport support services and storage.

The rental, hiring and real estate services sector (12), including rental and hiring services, ownership of dwellings, and non-residential property operations and real estate.

The administrative and support services sector (14), including employment, travel agency and other administrative services, building cleaning, pest control and other support services.

The art and recreation services sector (19), including heritage, creative and performing arts, sports and recreation and gambling.

In Australia, TSA estimates are developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). At the state level, TSAs were developed by the Tourism Research Australia (TRA) and the Centre for Economic Policy (CEP) [

2,

26]. For example, Ho et al. (2008) developed a set of TSAs for each Australian state and territory for 2003–2004 and 2006–2007. They used visitor expenditure from the two major Australian tourism surveys, the Australian Tourism Satellite Account and IO tables for each state. Ho et al. [

27] noted that TSAs for Queensland were developed by the Queensland Treasury for 1998–1999 and 2003–2004. Deloitte [

28] and CEP [

26] have also examined tourism’s contribution at the regional level in Queensland. Pham et al. [

29] examined the feasibility of constructing TSAs for Queensland, Australia. They used region-specific expenditure patterns obtained from Tourism Research Australia. They noted that, while the regional TSAs might generate policy-relevant insights regarding the tourism activity, the construction of a TSA at the regional level is a complex and expensive task. Ragab [

30] also noted that some of the Australian TSA tables are presented in an aggregated form without breakdowns that makes them unusable for the detailed IO analysis at the regional level.

For the assessment of ongoing economic impacts, the expected increase in final demand from tourism on Fitzroy SD industries was adjusted using TSAs for Queensland and available data for Central Queensland [

2]. Direct tourism output by industry at basic prices in Queensland was used to allocate the share of final demand to each tourism related industry. Queensland TSAs are compiled to be comparable with IO tables. The impacts are summarized in terms of how they transfer into the economy as follows:

Initial stimulus is the level of investment made by the industry in the economy

Direct impacts are the flow-on effects that the industry has into the business industry through the purchase of goods and services from other industries in the economy

Indirect impacts are the effects on other businesses due to an increase in demand for their products and services

Induced impacts are the impacts on final household demand as a result of higher employment across all industries

Given the limitations discusses earlier, the estimates are likely to be the upper bound of the employment effect.

4. Case Study

Queensland contributed 25% to total direct tourism gross value added in Australia, which is about 4% to the state economy, in 2013–2014. Queensland contributed 25% to the total number of persons employed directly in tourism-related industries with tourism’s direct share of Queensland jobs being 5.6% in 2013–2014. The tourism products and services that contributed most to tourism consumption nationally were takeaway and restaurant meals (15.6%), long-distance passenger transportation (15%), accommodation (11.7%), shopping (12.6%), fuel (9.7%) and food products (7%). In Queensland, the main products and services that contributed most to tourism consumption were accommodation (27.4%), cafes, travel agency and tour operator services (30%) and restaurants and takeaway food services and clubs and bars (26.9% each) [

2].

Table 2 shows growth in tourism contribution in Queensland in gross value added, taxes and gross state product, while the number of persons employed has been through growth and decline between 2006–2007 and 2013–2014.

Emu Park is a small coastal town in the Livingstone Shire Council in Queensland, 21 km south of Yeppoon (Livingstone Shire Council’s headquarter), 30 km south-west of Rockhampton, a regional city for the Central Queensland region and about 700 km north of Brisbane (Queensland’s Capital). It has a population of more than 2000 people. Emu Park is part of Central Queensland (Fitzroy SD) tourism region (

Figure 1).

Table 3 provides a summary of the socio-demographics characteristics of the Livingstone Shire Council where Emu Park is located, Fitzroy SD and Queensland.

In 2013–2014, the tourism activity in Central Queensland generated A$0.7 billion in direct tourism output, A$0.343 billion in direct gross value added (or 3.1% of total gross value added), A$0.375 billion in gross regional product (or 1.9% of total gross regional product) and 4,600 direct jobs for people employed by the tourism industry (or 3.9% of the total regional employment). The tourism industries that generated the highest economic benefits, including gross value added, gross regional product and employment to Central Queensland in 2013–2014, were accommodation; retail trade; and cafe, restaurants and takeaway food services [

28].

Emu Park is a popular tourist destination in Livingstone Shire [

33]. However, Emu Park’s infrastructure and services that cater for the tourists are not adequate to attract and retain more tourists in this region. Average annual income from the overnight staying visitors in Yeppoon/Emu Park communities was only 12% of the Central Queensland [

3].

This lower share of tourist visitation in the Yeppoon and Emu Park region is one of the disadvantages that the Yeppoon and Emu Park region is facing. Livingstone Shire Council has proposed a number of projects to develop the Emu Park’s near foreshore [

34]. The new proposed infrastructure and facilities would attract up to 40 thousand more overnight visits in this region and up to A$12M per annum in tourism revenue [

3]. This paper adopts a conservative estimate of A$5M per annum of the new tourism revenue that is expected to result from the project.

6. Summary and Discussion

An analysis of the direct and indirect economic impacts of the construction stage of the project has identified large and positive gains for the regional and state economies. During the construction, the total impacts on the Fitzroy region are expected to be A$11.2M of output, A$4.4M in value added, A$2.2M of income, and an additional 31.2 jobs. At the state level, the total impacts of the construction stage are expected to be A$13.3M of output, A$5.5M in value added, A$2.7M of income, and an additional 38.2 jobs.

Some level of caution needs to be attached to these estimates, particularly those relating to employment impacts. The model that is used assumes that the bulk of additional services and supplies can be sourced from the regional area and then from the state or national economies. As economies become more integrated it becomes easier to source services and supplies from other regions and overseas, suggesting that impacts on the regional area may be overstated.

Rolfe et al. [

3] found that similar developments could increase the visitor rates between 10% and 60%. They predicted that this increased number of visitors would provide up to A$12M additional revenue to the Livingstone Shire. The conservative estimate for A$5M was used in this paper to analyse the effect of developments on regional economy. The results showed that an equal expansion of each tourism related industry would result in an unequal increase in employment by industry. These are similar results to those of Jones and Munday [

12]. For example, trade and accommodation and food services would experience a larger increase in employment than the rental, hiring and real estate sector.

Tourism related industries in Fitzroy SD have a strong potential to contribute more to the regional economy. Similar to [

13] we found that tourism related industries do not have strong interconnections within the region. For example, tourism related industries can source more from within the region from information media and communication and art and cultural services sectors. Presently, less than 40% of their required suppliers from those industries are coming from within the region compared with Queensland. Additionally, the connections with the key industries can be encouraged. To improve the local supply, strategies such as local procurement strategies can be employed.

This paper suggests a methodology on how to increase the benefits of an industry at the regional level. It might be possible to further increase direct and indirect employment, income and other benefits of the project by, first, examining the tourism related industries and the share of tourism expenditure for each industry in the region. Second, key industries in the region need to be identified. Third, the connections between the tourism related industries and those key industries at regional level need to be investigated. Fourth, strategies promoting connections among key industries and tourism related industries, such as local procurement policies, need to be suggested. The regional economy will grow more rapidly if those connections are encouraged.