4.1. Relationship between PAYT Systems and Municipal Recycling Rates

As noted earlier, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of PAYT systems on municipal recycling rates. To do so, weighted average recycling rates for programs with and without PAYT systems were calculated and compared. This was done on both a system wide (all 223 municipalities in Ontario) and region specific (using the 9 municipal groupings specified by the WDO) basis. These results have been graphed and are illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 respectively.

As shown in

Figure 1, weighted average recycling rates for programs with PAYT systems are, on average, ~13.5% higher than municipalities without unit based garbage pricing schemes. This is consistent with previous findings from the literature (see [

2,

13]), although the magnitude of the differences in recycling rates was larger in this study. When looking at differences in recycling rates by regional group (shown in

Figure 2), we observe an interesting phenomenon—the effectiveness of PAYT schemes diminishes the further you go outside major urban areas. In Group 1 (Large Urban) differences in recycling rates between PAYT and non PAYT municipalities was 15.5%. However, as you move from Large Urban to Medium Urban and then Rural Regional groups, the gap in recycling rates narrows. For municipal groups 7 (Small Urban) through 8 (Rural Depot South), there is no appreciable difference in recycling rates between municipalities who choose to implement PAYT systems and those that don’t. While it is difficult to isolate the reason for why this occurs, results from surveys with householders shed light on this issue. Enforcement of garbage bag limits by the municipality tends to be much higher in urban areas. There are also fewer opportunities for households to illegally dump garbage in densely populated communities. As you move outside of Ontario’s major urban centers, the effect of PAYT on household recycling decreases, as it is not perceived as being enforced consistently.

Table 2 below summarizes the results of a two tail t test to determine whether differences in municipal recycling rate values are explained by chance, or measurable differences between PAYT and non PAYT municipalities. For all groups (with the exception of Rural Regional, which does not have a PAYT program), differences in recycling rates are statistically significant.

Table 2.

Two Tail T Test (Municipal Recycling Rates).

Table 2.

Two Tail T Test (Municipal Recycling Rates).

| Municipal Group | t | p | DF |

|---|

| Large Urban | 4.015 | 0.001* | 60 |

| Urban Regional | 4.073 | 0.001* | 60 |

| Medium Urban | 3.819 | 0.001* | 70 |

| Rural Regional | - | - | 140 |

| Small Urban | 3.707 | 0.001* | 230 |

| Rural Regional | 3.659 | 0.001* | 320 |

| Small Urban | 3.646 | 0.001* | 630 |

| Rural Depot North | 3.195 | 0.001* | 460 |

| Rural Depot South | 3.232 | 0.001* | 330 |

4.2. Relationship between PAYT Systems and Municipal Program Costs

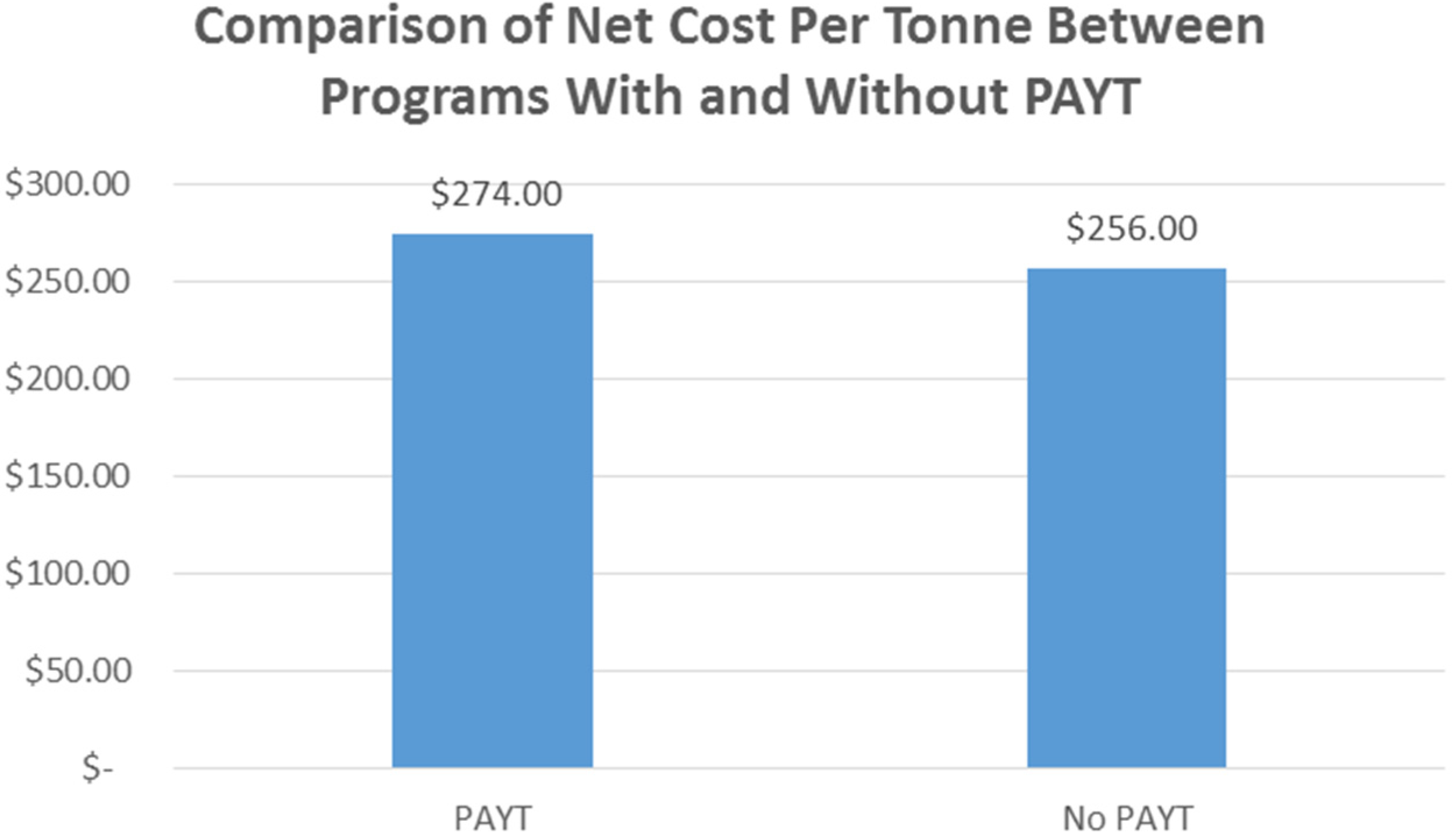

A secondary objective of this study is to determine the effect of PAYT systems on municipal program costs. Weighted average net costs (expressed on a per tonne basis) for programs with and without PAYT systems were calculated and compared (Note: Net cost is calculated by taking the gross cost of material management reported by the municipality and subtracting revenues received from the sale of recyclable material). This was done on both a system wide (all 223 municipalities in Ontario) and region specific (using the 9 municipal groupings specified by the WDO) basis. These results have been graphed and are illustrated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 respectively.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Weighted Average Net Cost per Tonne for Programs with and Without PAYT (System Wide).

Figure 3.

Comparison of Weighted Average Net Cost per Tonne for Programs with and Without PAYT (System Wide).

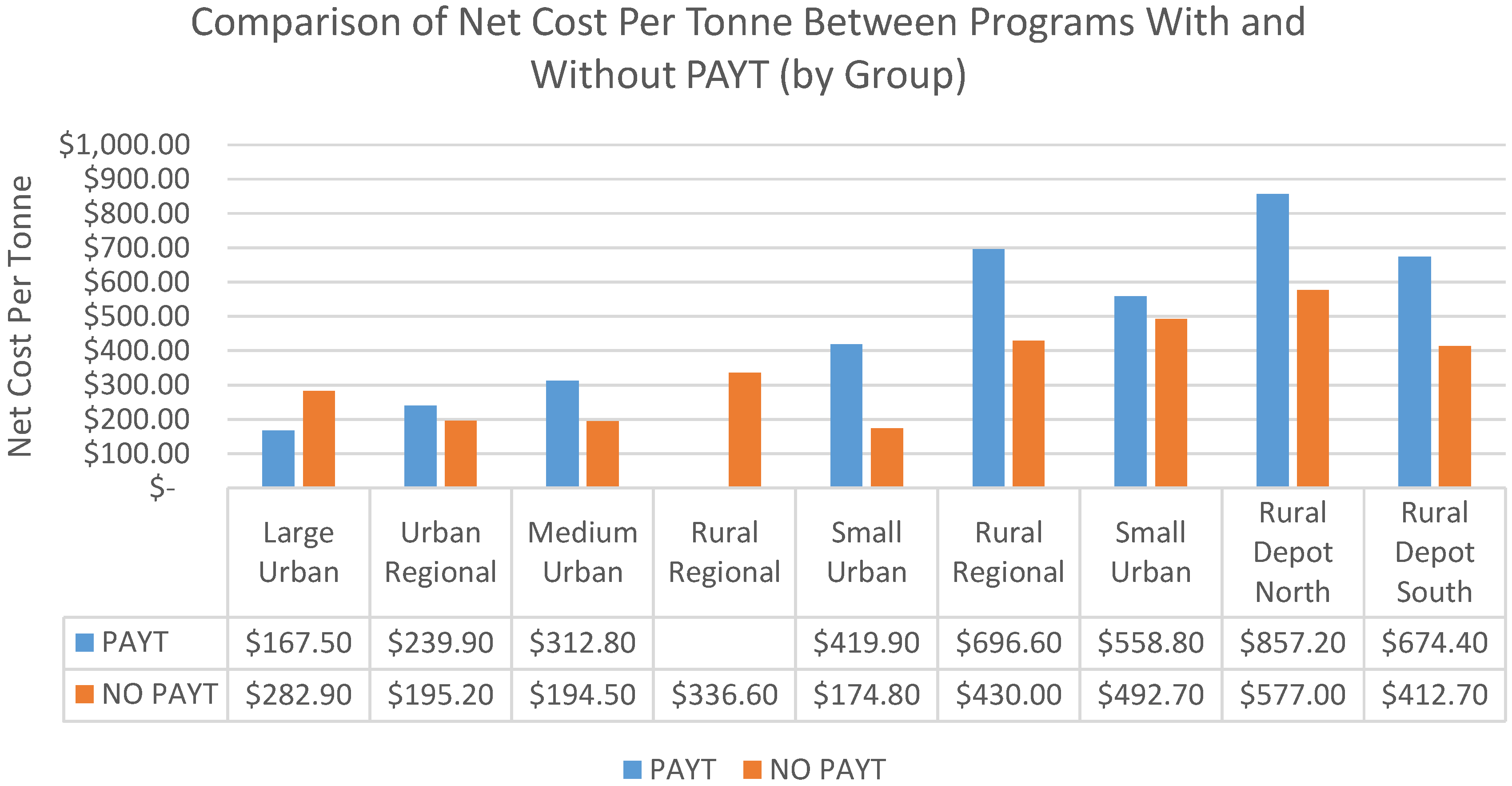

Figure 4.

Comparison of Weighted Average Net Cost per Tonne for Programs With and Without PAYT (By municipal group).

Figure 4.

Comparison of Weighted Average Net Cost per Tonne for Programs With and Without PAYT (By municipal group).

As shown above, the net cost of material management (on a per tonne basis) is approximately 8 percent higher in municipalities who implement some form of unit based pricing for weight disposal. This is once again consistent with our understanding of the costs incurred for administering, maintaining and enforcing PAYT systems in a community. Additional resources are required for waste collectors to “ticket/fine” households for setting out more than the designated limit of garbage bags. However, when looking at material management costs by municipal group, we notice that PAYT municipalities classified as “Large Urban” actually have lower material management costs than those that don’t. At this time, it is unclear as to why this is result occurred—there may be certain infrastructural and operational characteristics for PAYT municipalities in group 1 that result in lower material management costs on the whole. Densely populated urban areas tend to enjoy cost advantages relative to other areas on the whole—independent of PAYT policy. Collection costs, on average, tend to be lower in urban areas as a greater quantity of households can be serviced per trip (due to population density). Urban areas also tend to generate a “critical mass” of recyclables that are required to make curbside collection an economically viable waste management option. An analysis of groups 2 through 9 produced results more in line with our previous expectation. PAYT municipalities, on average, face higher material management costs than municipalities who do not impose bag/volume limits on household waste. However, the implementation of PAYT systems in groups 6 through 9 fails to result in appreciably higher recycling rates. Given that these programs are facing higher material management costs (in part due to the administrative burden of implementing PAYT schemes), it calls into question whether garbage bag limits are an appropriate policy for encouraging household waste diversion.

Table 3 below summarizes the results of a two tail t test to determine whether differences in municipal net cost per tonne values are explained by chance, or measurable differences between PAYT and non PAYT municipalities. For all groups (with the exception of Rural Regional, which does not have a PAYT program), differences in net cost per tonne are statistically significant.

Table 3.

Two Tail T Test (Net Cost Per Tonne).

Table 3.

Two Tail T Test (Net Cost Per Tonne).

| Municipal Group | t | p | DF |

|---|

| Large Urban | 3.837 | 0.001* | 60 |

| Urban Regional | 4.197 | 0.001* | 60 |

| Medium Urban | 3.828 | 0.001* | 70 |

| Rural Regional | - | - | 140 |

| Small Urban | 3.396 | 0.001* | 230 |

| Rural Regional | 3.421 | 0.001* | 320 |

| Small Urban | 3.551 | 0.001* | 630 |

| Rural Depot North | 3.837 | 0.001* | 460 |

| Rural Depot South | 3.745 | 0.001* | 330 |

4.3. Analysis of Household Survey Responses

Seven geographical regions (as specified by Waste Diversion Ontario) were targeted to complete questionnaires pertaining to daily household recycling activity. Geographic regions are defined by population density, geographic location and collection type (curbside collection vs. depot systems).

These groups include:

- (1)

Large Urban (Toronto, Peel Region)

- (2)

Urban Regional (Barrie)

- (3)

Medium Urban (Windsor)

- (4)

Rural Regional (Peterborough)

- (5)

Small Urban (Orangeville)

- (6)

Rural Collection—North (Timmins)

- (7)

Rural Collection—South (North Glengary)

These groups were selected on the basis that they adequately represent the geographic differences in the province. Survey data surrounding household perceptions of and response to PAYT schemes is summarized based on the answers provided by respondents.

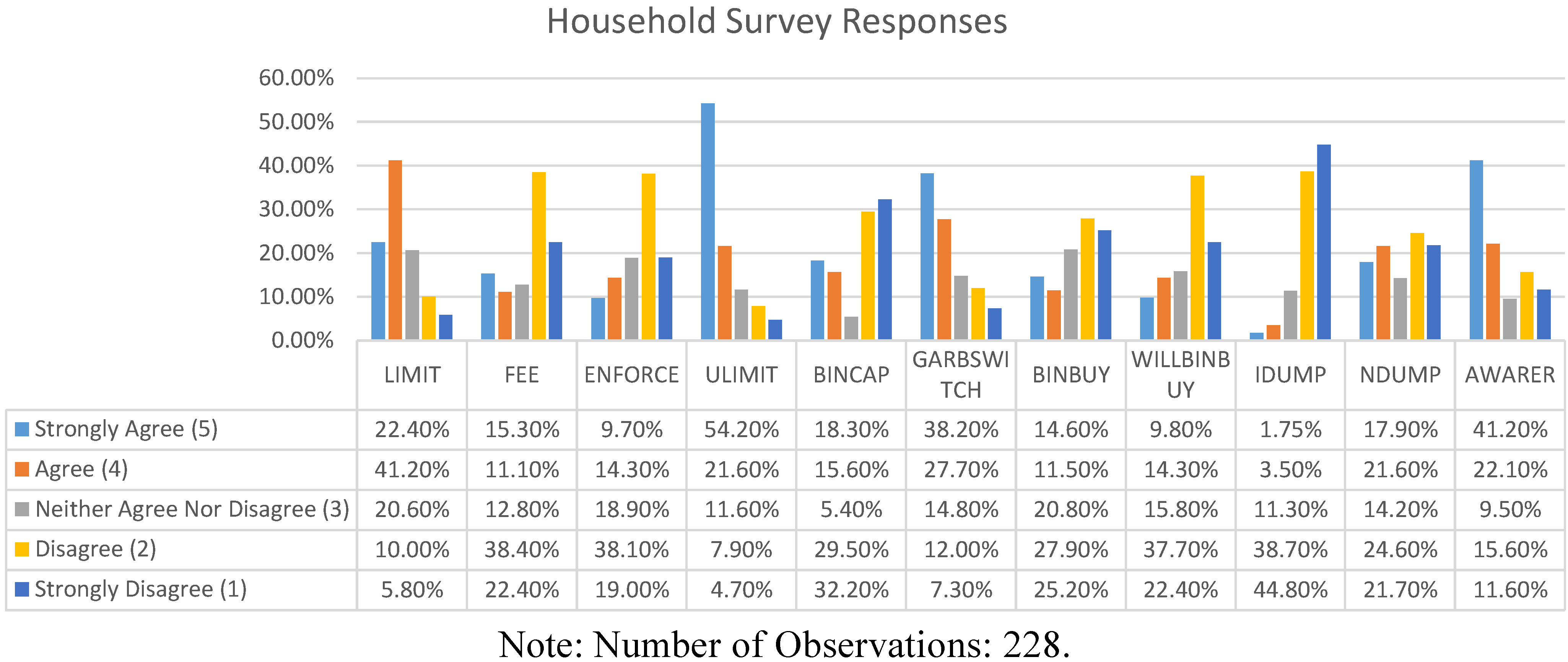

Table 4 describes the statements that were used in the survey to elicit household’s experience, knowledge and attitudes towards pay as you throw policy along with the respective distribution of Likert scale responses. A five point Likert scale was used to measure respondent’s answers (Strongly Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neither Agree or Disagree, Somewhat Agree, Strongly Agree). A total of 223 household survey responses were collected.

Table 4.

Description of Survey Statements.

Table 4.

Description of Survey Statements.

| Survey Code | Survey Statement |

|---|

| LIMIT | “I am aware that the city imposes limits on how much garbage I can place on my curb” |

| FEE | “I pay a fee for putting out more garbage bags than the city allows” |

| ENFORCE | “The city enforces their garbage bag limit policy” |

| ULIMIT | “I put out more garbage on days where the city has unlimited garbage pickup” |

| BINCAP | “My recycling bin has enough space for the amount of recyclables my house generates” |

| GARBSWITCH | “I put my recyclables in the garbage bin because I don't have enough space in my recycling bin” |

| BINBUY | “I know that I can purchase additional recycling bins and bags from the city” |

| WILLBINBUY | “I am willing to purchase additional recycling bins to store my recyclables” |

| IDUMP | “I illegally dump garbage to avoid paying the bag limit fee” |

| NDUMP | “I notice my neighbors illegally dumping garbage to avoid paying the bag limit fee” |

| AWARER | “I know that recycling is mandatory in Ontario” |

Figure 5.

Household Survey Responses.

Figure 5.

Household Survey Responses.

Note: Number of Observations: 228.

Table 5.

Mean Score and Standard Deviation of Household Survey Responses.

Table 5.

Mean Score and Standard Deviation of Household Survey Responses.

| Survey Statement | LIMIT | FEE | ENFORCE | ULIMIT | BINCAP | GARBSWITCH | BINBUY | WILLBINBUY | IDUMP | NDUMP | AWARER |

|---|

| Mean | 3.64 | 2.12 | 2.58 | 4.13 | 2.61 | 3.78 | 2.62 | 2.51 | 1.79 | 2.89 | 3.84 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 1.35 | 1.51 | 1.27 | 1.36 | 1.25 | 0.89 | 1.43 | 1.44 |

4.3.1. Awareness and Enforcement of PAYT Systems

Awareness

Survey Statement:

- (1)

“I am aware that the city imposes limits on how much garbage I can place on my curb”

63.6% of respondents indicated they either agreed, or strongly agreed with the above statement. Differences in awareness were observed among the seven communities targeted in the study. Communities situated in densely populated urban areas demonstrated higher levels of awareness than those located in rural or northern areas.

Of the 36 respondents who indicated that they either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement, all were from regions classified as rural.

Enforcement

Survey Statement:

- (1)

“I pay a fee for putting out more garbage bags than the city allows”

- (2)

“The city enforces their garbage bag limit policy”

60.8% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed when read the statement regarding fee payment. The majority of respondents indicated they rarely or never pay fees for placing excess garbage on the curbs. This result was reinforced when the follow up statement regarding enforcement was asked, where only 24% of respondents agreed that their city enforces garbage bag limit policy.

Once again, regional differences were observed in the perceived level of PAYT enforcement, with 37.5% of survey respondents from urban communities answering that PAYT schemes were enforced to some degree. This is compared to only 17.2% of respondents in rural and northern communities who felt that garbage disposal limits were being enforced. This disparity in the perceived level of enforcement among urban and rural/northern areas may also explain the difference in PAYT awareness. Generally speaking, there is very little communication on the part of the municipality in informing residents that PAYT systems are in effect in a given area. Thus, policy awareness becomes a function of whether bag limits are being enforced—unless households observe the policy in effect, they are ignorant to its existence.

4.3.2. Capacity of Recycling Bins

Survey Statement:

- (1)

“I put out more garbage on days where the city has unlimited garbage pickup”

- (2)

“My recycling bin has enough space for the amount the recyclables my house generates”

- (3)

“I put my recyclables in the garbage bin because I don’t have enough space in my recycling bin”

- (4)

“I know that I can purchase additional recycling bins and bags from the city”

- (5)

“I am willing to purchase additional recycling bins to store my recyclables”

The above group of questions were asked to respondents to gauge whether there was sufficient recycling bin capacity given the amount of waste/recyclables generated by households. Gauging whether there is sufficient recycling capacity is of particular importance in PAYT systems, as PAYT systems are only effective if recycling bins have sufficient capacity to allow for recyclable material that would otherwise be placed in the waste stream.

Overwhelmingly, respondents indicated that there was insufficient recycling bin capacity (61.7%) with majority of respondents indicating that they were forced to put items they identified as recyclable in the garbage due to insufficient space in the recycling bin (65.9%). Respondents also indicated that they stockpiled garbage due to bag limit policy, waiting for “Unlimited” garbage days by the city before placing all material out on the curb. (Some municipalities have special days where they remove the limits on the number of garbage bags set out by households).

Despite the dearth of recycling bin space for households, the majority of survey respondents indicated that they were unaware that they could purchase additional recycling bins or bags (53.1%) and were seemingly unwilling to do so (with 60.1% of respondents indicating that they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “I am willing to purchase additional recycling bins to store my recyclables”).

This suggests that while households are generally in favor of recycling, they are unwilling to incur additional costs beyond the time it takes to source separate recyclables.

4.3.3. Illegal Dumping of Excess Garbage

Survey Statement:

- (1)

“I illegally dump garbage to avoid paying the bag limit fee”

- (2)

“I notice my neighbors illegally dumping garbage to avoid paying the bag limit fee”

5.25% of respondents admitted to illegally dumping waste generated by their households (

i.e., in neighbors garbage bins, community dumpsters, public space garbage bins

etc.). This number may be under reported, as 39.5% of respondents said that they witnessed other members of their community illegally dumping garbage. Given the potentially sensitive nature of the question (households are fined for the act), it seems likely that respondents are unwilling to divulge their propensity to illegally dump material. Of note, of the 12 respondents who admitted to illegal dumping, all lived in areas classified as either rural or northern communities. As noted by the USEPA [

1], illegal dumping is more likely to take place in remote areas where access to recycling services is limited. Further to that point, rural communities provide more opportunities to dispose of material in a clandestine manner relative to densely populated urban areas.

4.4. Open Ended Analysis

For open ended survey questions, all survey responses were recorded, transcribed and reviewed to identify thematic categories and codes. Respondents were asked to answer two open ended questions related to PAYT schemes: (1) Do you think garbage bag limits are a good thing? Please explain your answer; and (2) Would you still recycle if your city eliminated limits on the amount of garbage bag you could put out? Please explain your answer. Respondents were asked to answer freely, and did not receive any additional input or instructions from the enumerator (beyond issues of clarification).

After a careful review of the interviews with each of the 228 respondents, nine and eight coding categories were identified for open ended questions one and two respectively. These findings have been summarized in

Table 6 below:

Table 6.

Coded Responses.

Table 6.

Coded Responses.

| Do You Think Garbage Bag Limits Are a Good Thing? |

| Positive Attitudes (Yes) | Negative Attitudes (No) |

| “Good for the environment”—57 | “Should be eliminated”—97 |

| “Less garbage goes to the landfill”—34 |

| “Reduces pollution”—15 | “Inconsistent enforcement”—55 |

| “Promotes recycling”—63 |

| “Stops wasteful behavior”—84 | “Unfair”—112 |

| Would you still recycle if your city eliminated limits on the amount of garbage bag you could put out? |

| Positive Attitudes (Yes) | Negative Attitudes (No) |

| “I am legally obligated to”—178 | “Saves me time”—34 |

| “It’s the right thing to do”—91 |

| “It’s good for the environment”—29 | “Don’t care”—14 |

| “Reduces litter”—16 |

| “Sets a good example”—10 | “Doesn’t make a difference”—11 |

Codes have been organized into two additional container categories indicating positive/negative attitudes towards pay as you throw policy and recycling as a whole.

A “best fit” approach was utilized to categorize respondent’s answers. For example, “It makes people throw away less garbage” was coded under the stops wasteful behavior category. The results from our analysis suggest that the majority of respondents viewed garbage bag limits unfavorably. 57% of respondents (130 of 228) thought that PAYT schemes should be eliminated, citing reasons such as being unfair, inconsistently enforced, and time consuming. Many respondents viewed bag limits as a form of tax grab by the city, and did not understand why they were being forced to pay both a property tax and bag fee. Anecdotes such as “my neighbor throws away more than two bags nearly every week, but never pays a fee” were noted during the interviews. For these respondents, the objection to bag limits was not attributed to the policy itself, but its lack of enforcement. Respondents indicated that bag limits were a waste of time if the policy was not going to be consistently and uniformly enforced.

Conversely, 98% of respondents felt that bag limits should not be eliminated, and served a role in promoting recycling and environmental wellbeing, while serving as a deterrent to wasteful behavior. 14.9% of respondents felt that bag limits reduced the amount of material being sent to the landfill, which in turn, was good for the environment. 6.5% of respondents felt as though bag limits reduced pollution (it was unclear as to what respondents meant by pollution), while 25% felt that it was good for the environment. The general opinion of respondents who viewed bag limit policy favorably was that it prevented unnecessary excess. More than 36% of respondents felt that bag limits prevented wasteful behavior.

Overwhelmingly, survey participants indicated that they would continue to recycle even if PAYT policy was eliminated. The primary reason given by respondents was that recycling was legally mandated by the province, so the threat of penalty remained even with bag limit fees removed. As per Ontario regulation 101/94, every municipality in the province with a population greater than 5000 people must implement a residential recycling program. This result, coupled with the findings from our statistical analysis, indicate that there is a synergistic effect between mandatory recycling legislation and bag limit policy. While most people recycle because of a legal obligation, they will recycle more because of garbage bag limits. Moral imperative and personal concern for the environment also ranked highly on reasons for continued recycling among respondents, as many indicated that recycling was “the right thing to do” and “good for the environment”. Of the 48 respondents who said they would stop recycling if PAYT systems were eliminated, 14 indicated that they did not care about recycling, while the remaining 34 said that recycling required too much time to sort through the garbage and store recyclable material separately.

Table 7 provides the summary statistics for responses provided by the 223 survey respondents. Age and Gender are included as demographic variables, while Income and Education are used as socioeconomic controls. Education was coded as a four point categorical scale, with higher values indicated greater levels of educational attainment. For the income variable, respondents were asked to select from five income ranges that best represents their earnings, not actual values. Gender is coded as a dummy variable, 1 = male, 0 = female.

Table 7.

Summary Statistics of Survey Participants.

Table 7.

Summary Statistics of Survey Participants.

| Variable | Mean/Percent |

|---|

| Gender | 49.2% 1 |

| Age | 41.2 |

| College | 51.5% 2 |

| Income | $45,000–$60,000 |

An ordered logit model is used to test for any relationships between the survey responses and socioeconomic/demographic variables, as well as locality.

Table 8 presents the ordered Logit results for the 11 dependent variables taken from the survey data.

Table 8.

Ordered Logit Model of Demographic/Socioeconomic variables on Attitudes towards PAYT Policy.

Table 8.

Ordered Logit Model of Demographic/Socioeconomic variables on Attitudes towards PAYT Policy.

| VARIABLE | LIMIT | FEE | ENFORCE | ULIMIT | BINCAP | GARBSWITCH | BINBUY | WILLBINBUY | IDUMP | NDUMP | AWARER |

|---|

| GENDER | 0.380 | −0.021 | −0.144 | 0.875 * | 0.011 | 0.644 | 0.244 | −0.142 | 0.141 | 0.021 | 0.004 |

| AGE | 0.727 | 0.061 | 0.191 | 0.884 | 0.445 | 0.122 | 0.412 | 0.754 | 0.143 | 0.174 | 0.947 * |

| INCOME | −0.019 | 0.015 | 0.087 | −0.215 | −1.794 ** | −0.248 | 0.341 | 0.633 | −0.054 | −0.782 | 0.874 |

| EDUCATION | 0.083 | −0.002 | 0.004 | −0.045 | −0.244 | −0.211 | 0.774 | 0.716 | −0.035 | −0.225 | 1.133 * |

| MUNICIPAL GROUP | YES *** | YES *** | YES ** | YES ** | YES * | YES ** | YES * | YES | YES | YES *** | YES ** |

As can be seen, municipal group (municipality’s location) has the greatest bearing on attitudes towards and perception of PAYT policy among study participants. In 9 of the 11 dependent statements taken from the survey data, municipal grouping had a statistically significant influence. Consistent with our expectation, municipalities classified as rural and/or northern reported inconsistent enforcement of PAYT policy, higher incidences of illegal dumping, and less awareness surrounding the implementation of said policy. Of note, there was an inverse relationship between stated income levels and the survey statement “My recycling bin has enough space for the amount of recyclables my household generates”. Respondents with higher levels of income reported having insufficient space for recyclables in their Blue Bin. This would suggest a positive relationship between income and household waste generation, a finding that has mixed empirical support (see [

24,

25]). Other salient findings gleaned from

Table 6 indicate that awareness of Ontario’s mandatory recycling policy is a function of both age and education. Generally speaking however, age, income, and gender had little bearing on how study participants responded to survey statements.

4.5. Survey—Municipal Waste Managers and Packaging Producers

Semi-structured interviews and surveys were developed in an attempt to gauge the attitudes and opinions of recycling stakeholders regarding existing and future policy initiatives.

Semi-structured interviews and surveys were conducted with recycling stakeholders from nine geographic areas in the province. Interview participants were selected on the basis of representing Ontario’s different recycling stakeholder groups (municipal officials, industry stewards & industry funded organizations).

Table 9 below briefly describes each recycling stakeholder and their role within the provincial recycling system.

Table 9.

Description of Recycling Stake Holders.

Table 9.

Description of Recycling Stake Holders.

| Stakeholder | Description | # of Respondents |

|---|

| Municipal Waste Managers | Municipal waste managers are municipal employees responsible for operation, delivery, and maintenance of waste management services. Municipal waste managers are traditionally tasked with setting budgets, allocating staff resources, and setting policy priorities for municipal waste programs. Most municipal waste managers belong to the Municipal Industry Panel Committee (MIPC), advocating for the financial interests of their particular municipality. | 29 |

| Packaging Producers | Packaging producers are representatives from packaging companies that are financially obligated to remit fees to Stewardship Ontario. These fees are used to (partially) finance the operation of the Blue Box program under Ontario’s shared producer responsibility model. In most instances, packaging producers who agreed to participate in the study were specially designated employees responsible for end of life management of company waste. | 12 |

| Industry Funded Organization | Study participants from industry funded organizations included representatives from Stewardship Ontario, the Canadian Beverage Council, The Paper and Paperboard Packaging Environmental Council and the Canadian Plastics Industry Association. Industry Funded Organizations represent and advocate for the interests of their respective members. They are financed through membership dues. Generally speaking, IFOs represent the interests of a specific sector or packaging type. | 6 |

A request for participation was sent via email to potential study participants. This correspondence outlined the purpose of the study, what the data and findings would be used for, and what results would be shared with potential participants. Interviews were conducted in person, via telephone and electronic correspondence. How the interview was administered was decided by interviewees and scheduled at their convenience.

A high-level summary highlighting the findings from phase 1 of the study (best practice testing) was sent to all study participants two weeks prior to conducting the surveys/interviews. This was done to ensure that participants had sufficient time to review the outcome of the analysis and seek clarity on any issues surrounding methodology, findings, etc. Questionnaires were pre-tested and refined prior to conducting the official survey. The pre-test allowed for wording refinements and changes to the ordering of the questions. The finalized survey was conducted over a twelve-week period beginning in February and running through to April 2014.

For the semi-structured survey, respondents were asked to answer questions using a combination of Likert scales and open-ended statements. Depending on how the survey was administered, respondents were either: (a) read questions and asked to mark their responses on the survey with the assistance of an enumerator; or (b) asked to complete the survey electronically and submit their responses via email to the project lead. Electronic surveys included a contact number and email for the project lead (I served as the project lead), in the event that the respondent required assistance in completing the questionnaire.

Upon completion of the survey, respondents were asked a series of open ended questions related to existing best practices, the current state of recycling in Ontario, the proposed waste reduction act, and where they see the Blue Box program going in the future. Interviews conducted in person were recorded and later transcribed in full. For participants who opted to participate electronically, additional comment pages were included at the end of the survey to allow for respondents to record their answers.

A total of 114 stakeholders were contacted and asked to participate in the study. Of those contacted, 47 respondents successfully completed the survey (32 electronically, 15 in person), for a response rate of 41.22%.

Table 10 further breaks down the stakeholder group “municipal waste managers” by geographic region.

Table 10.

Municipal Waste Managers (by geographic region).

Table 10.

Municipal Waste Managers (by geographic region).

| Region | # of Respondents |

|---|

| Large Urban | 12* |

| Urban Regional | 4 |

| Medium Urban | 5 |

| Rural Regional | 2 |

| Small Urban | 1 |

| Rural Collection—North | 2 |

| Rural Collection—South | 1 |

| Rural Depot—North | 1 |

| Rural Depot—South | 1 |

4.6. Analysis of Municipal Waste Manager and Packaging Producer Survey Responses

Survey data surrounding municipal waste managers and packaging producers’ perception of PAYT policy and their effectiveness are summarized in

Table 11 and

Table 12. Much like the household surveys, municipal waste managers and packaging producers were read a series of statements regarding PAYT policy, and asked to indicate their level of agreement/disagreement with the statement. A five point Likert scale was used to measure respondent’s answers (Strongly Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neither Agree or Disagree, Somewhat Agree, Strongly Agree). These results from the respective stakeholders (municipal waste managers and packaging producers) were compared and contrasted to elucidate any differences in their responses. Given that these two groups traditionally have competing interests and policy objectives, I thought it may be useful to measure differences (if any) in how they perceived policies such as PAYT. The most frequently coded responses from municipal waste managers during the semi structured interviews are also included. It should be noted that interviews conducted with packaging producers regarding PAYT policy and experiences resulted in limited feedback. Packaging producers acknowledged that were not overly familiar with how such policies were implemented, or the challenges associated with them. Beyond comments with respect to the perceived effectiveness of PAYT policy, most declined to offer any additional commentary or provide any personal anecdotes.

Table 11.

Municipal Waste Managers PAYT Survey.

Table 11.

Municipal Waste Managers PAYT Survey.

| Survey Statement | Strongly Agree (5) | Agree (4) | Neither Agree Nor Disagree (3) | Disagree (2) | Strongly Disagree (1) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|

| “I think that pay as you throw schemes are an effective way to increase household recycling.” | 32.7% | 35.8% | 12.4% | 14.1% | 5% | 4.14 | 1.11 |

| “Pay as you throw policies are an easy policy to enforce.” | 10.3% | 13.7% | 20.8% | 33.8% | 21.3% | 2.54 | 1.21 |

| “Pay as you throw policy requires significant administrative and staffing resources.” | 28.9% | 40.7% | 11.4% | 6.6% | 13.4% | 4.19 | 1.25 |

| “Pay as you throw policy results in households illegally dumping garbage.” | 27.8% | 22.5% | 19.7% | 20.8% | 9.2% | 2.61 | 1.17 |

| “Pay as you throw schemes should be promoted as a recycling best practice.” | 22.7% | 30.6% | 12.7% | 20.6% | 13.4% | 4.12 | 1.28 |

The vast majority of both municipal waste managers and packaging producers agreed (or strongly agreed) with PAYT schemes being an effective way to increase household recycling (although municipal waste managers indicated higher levels of agreement (68.5% vs. 50.9%). Only 16% of municipal waste managers did not believe PAYT schemes were an effective method for improving diversion (compared to 34.1% of packaging producers). Despite municipal waste managers viewing PAYT policy as more effective than packaging producers, they expressed lower levels of agreement when read the statement “Pay as you throw schemes should be promoted as a recycling best practice” (53.3% vs. 60%). This result was surprising, particularly given the perceived efficacy of PAYT in promoting household recycling among municipal waste managers. To understand this unexpected result, we turn to examining the additional survey responses provided by municipal waste managers.

Table 12.

Packaging Producers PAYT Survey.

Table 12.

Packaging Producers PAYT Survey.

| Survey Statement | Strongly Agree (5) | Agree (4) | Neither Agree Nor Disagree (3) | Disagree (2) | Strongly Disagree (1) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|

| “I think that pay as you throw schemes are an effective way to increase household recycling.” | 24.8% | 26.1% | 15 | 18.3% | 15.8% | 3.92 | 1.22 |

| “Pay as you throw schemes should be promoted as a recycling best practice.” | 28.5% | 31.5% | 14.7% | 18.6% | 6.7% | 3.98 | 1.25 |

Despite the effectiveness of PAYT policy, most municipal waste managers felt as though PAYT schemes were difficult to administer and implement (with more than 50% of all municipal waste managers disagreeing (or strongly disagreeing) with the statement “Pay as you throw policies are easy to implement”). Survey respondents also indicated that PAYT policy posed an administrative burden, with 69.6% of municipal waste managers feeling as though PAYT policy required significant staffing resources. Anecdotes provided by municipal waste managers during the semi-structured interview suggested that PAYT policies were only effective if they were being enforced (a result that is confirmed during interviews with households). Some municipalities, particularly those in rural and northern areas, lack the necessary resources to ensure households are complying with a bag limit policy. Several participants from the waste manager survey also indicated that enforcement of bag limit policy actually encouraged disposing of waste illegally among households. 53.3% of municipal waste managers felt as though PAYT policies gave rise to illegal dumping of garbage in their communities. Illegal dumping of garbage in public space results in additional costs incurred by the municipality—costs that they are unable to recover under the province’s existing producer responsibility model. In Ontario, municipalities are only eligible to receive reimbursement for waste collected from households. When waste is illegally disposed of in places like parks, dumpsters etc., the municipality must bear the entire cost for managing that material.

The concerns expressed by municipal waste managers in this study’s survey echo the sentiments expressed by others in the existing literature on PAYT policy. While few dispute the effectiveness of PAYT schemes in promoting diversion, there remains considerable debate as to whether such policies are worth the accompanying administrative challenges.