Abstract

Geoparks are territorial organizations, whose primary aim is to foster sustainable local development through the promotion of geoheritage, geotourism and geoeducation. Sites of significant interest from the perspective of geosciences (geosites), as well as the overall geodiversity of the territory, are the fundamental resources for geopark activities. The distribution of these resources in the geographical space of geoparks may, however, be uneven. We first review four cases of UNESCO Global Geoparks from different European countries (Czechia, Germany, Hungary, Portugal) where such a situation occurs, with consequences on tourism development. Then, we place particular focus on an aspiring geopark of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes in SW Poland, providing evidence of its geoheritage and geodiversity values. The aspiring geopark integrates a mountainous–upland terrain and a lowland part, the latter with much fewer sites of interest and, apparently, fewer opportunities to successfully develop geotourism. Recognizing the challenges emerging from the non-uniform distribution of resources and learning from established geoparks, we highlight various opportunities to encourage (geo)tourism in the less diverse sections of the geoparks. Implementation of the ABC (abiotic–biotic–cultural) concept could be particularly helpful, as could be various events organized in these areas.

1. Introduction

Geoparks are territorial organizations aiming to develop sustainable tourism, particularly geotourism, based mainly on resources emerging from the appreciation of geoheritage and geodiversity [1,2]. Following the ABC (abiotic–biotic–cultural) concept, recommended for educational activities and tourism development in geoparks [3,4], other types of values and resources are taken into account as potential assets, but nevertheless, those associated with abiotic components of nature are at the core of geoparks. In fact, a basic prerequisite for an aspiring area to become a UNESCO Global Geopark is the occurrence of “geological heritage of international significance” within its territory. For the purpose of this paper, geodiversity is understood as the natural range of geological (rocks, minerals, fossils), geomorphological (land form, processes), hydrological and soil features [5]. It integrates elements of different ages and lifetimes, from protracted geological record trough landforms, typically evolving over the past few million years, to the contemporary hydrological system. Geoheritage, in turn, includes those elements of geodiversity which are considered the most valuable, particularly from the perspective of the geosciences, and therefore deserve protection [6,7]. The appreciation of geoheritage values usually goes hand in hand with the identification of specific localities, where these values are best represented. These localities are known as geosites [8,9]. If appropriately conserved and managed, selected geosites can be also used to support the tourism industry as places to visit, learn and experience. Thus, geosites are considered primary resources for geopark operations and geosite inventories are mandatory parts of any application to join the UNESCO Global Geoparks network.

However, geodiversity/geoheritage resources and implicitly geosites are not evenly distributed in geographical space, and this statement is valid for different spatial scales, from very local to regional and national. Furthermore, even though the scientific values of different geosites may be similar (although they could be difficult to compare with one another), their suitability for being developed for tourism may be different for reasons associated with conservation requirements, physical accessibility, distance, or specificity of a theme. Many geoparks are characterized by the non-uniform distribution of geoheritage resources within their territories, with implications for tourism development and possible benefits for local communities arising from geotourism. Moreover, there are two main forms of these differences. First, geosites may cluster in specific sectors of geoparks, leaving other areas relatively poor in sites of interest. This typically reflects the nature of geological and landform records themselves. Second, even if designated geosites are more evenly distributed to achieve more balanced geographical coverage, their values, especially for non-specialists, may not be appreciated in a similar way. For instance, spectacular landforms (e.g., rock crags, deep gorges, caves, high waterfalls, etc.) have much higher chances of attracting tourists than soil profiles; geological sections, especially in loose sediments; or most fossil sites [10]. Thus, the inevitably uneven distribution of geoheritage/geodiversity resources creates specific challenges for geoparks and promotion of geotourism in general.

In this paper, we aim to address this issue in more detail, diagnosing the problem and discussing possible solutions and opportunities. First, evidence of non-uniform distribution of resources is presented for several long-established UNESCO Global Geoparks (UGGps) in Europe, considered as appropriate examples. This overview forms a background for the second part, which includes a detailed examination of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark (LEV AG) in south-west Poland, whose application to join the UGG network is pending and which integrates areas with contrasting geoheritage and geodiversity resources. Third, experience from UNESCO Global Geoparks presented earlier is used to outline opportunities and solutions for the Land of Extinct Volcanoes.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we use evidence from several European geoparks, but the depth of inquiry varies, as reflected in the structure of the paper. An overview of resources for geopark activities, particularly the distribution of inventoried geosites, from four UNESCO Global Geoparks is based on the available published materials, mainly the nomination dossiers available for three of them (Bakony–Balaton, Bohemian Paradise, Estrela) [11,12,13], and official websites. Maps included in Röhling et al. [14] and other promotional materials provide information about geosite distribution in the Harz–Braunschweiger Land–Ostfalen UNESCO Global Geopark. In addition, each of these geoparks was visited by the authors, some more than once over the years, which allowed for ground checking of published information and direct observations.

Far more detailed analysis was performed for the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark. The basic source of information in the context of the problem addressed in this paper is the inventory of geosites prepared as part of an application to the UNESCO Global Geopark network [15]. The work on the inventory involved six experts from different fields of Earth sciences, all with a long record of conducting research in the region, and was coordinated by the first author of this paper. Based on experience and a literature review, as many as 130 sites of potential interest were identified, subject to qualitative description and quantitative evaluation from the perspective of potential tourist and educational use. For the qualitative part, a special descriptive form (documentation card) was designed and consistently used. It included information about location, dimensions, site properties related to scientific content (type of geosite, represented themes, rock type, landform type, origin—natural or anthropogenic, detailed characteristics, history of research, additional values, references), educational potential, accessibility, existing infrastructure and existing and potential threats.

Semi-quantitative evaluation was performed using a simple approach originally proposed for volcanic geosites in the region by Różycka and Migoń [16]. It considered six criteria, applicable to various values represented by geosites, their accessibility and their state of preservation. Since the inventory aims to evaluate the suitability of the development of geotourism within a future UNESCO Global Geopark, scientific value was only one among several attributes of a locality, not the dominant one. As any weighting of criteria in a semi-quantitative approach is subjective and open to debate [17], it was decided to apply identical weighting of individual criteria, and for each criterion, an identical partial score of 0–3 was adopted (Table 1). Thus, the possible maximum score was 18. While evaluating the state of preservation, it was assumed that vegetation growth negatively influences the value of a geosite, obscuring geological and geomorphological features and limiting physical access, occasionally causing the site to be totally inaccessible. Adverse impact of vegetation, diminishing the visibility of a geosite, is most evident during the peak of the plant growth season (May–October) which coincides with the main tourist season in Poland. Consequently, the scores adopted applied to the plant growth season.

Table 1.

Criteria and categories of geosite evaluation in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes [16].

It needs to be mentioned that the area subject to geosite inventory and evaluation is not identical to the extent of the aspiring geopark, which is short of two municipalities originally included in the inventory. The reasons for withdrawal, however, were not related to the outcome of the inventory and do not imply a lack of geoheritage values (see Section 4.1). Therefore, complete data from the original inventory, involving all adjoining municipalities, are used in this study.

3. Background—Evidence from selected UNESCO Global Geoparks in Europe

3.1. Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark

Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark, approved in 2005, is located in northern Czechia and, after several minor extensions, covers 833 km2. Geographically and geologically, it straddles two different regions. The north-eastern part belongs to the mountain range of the Sudetes, even though altitudes in the area included in the geopark do not exceed 750 m a.s.l., whereas the south-western part is within the Bohemian Tableland, with elevations in the range of 300–450 m a.s.l. (565 m a.s.l. maximum). Geologically, the former is made of basement and sedimentary rocks of Palaeozoic age, with a large share of Permian and Cenozoic volcanics, while the latter is dominated by sandstones and other clastic sedimentary rocks of Late Cretaceous age, the two being separated by a major fault [12,18,19]. Consequent to geological diversity, landforms and landscapes differ too. In the SW part, the topography bears a clear imprint of sandstone lithology, and it does so in such an intricate and complex way that the term “sandstone phenomenon” was coined by Czech researchers [20] to emphasize specific features of sandstone areas. Distinctive landforms include rock cities and labyrinths, cuesta ridges, cliffed margins of plateaus, isolated sandstone towers and pinnacles, canyons and caves, altogether forming a spectacular erosional landscape [18,21]. Within it, the rugged plateaus and escarpments of Hruboskalsko, Prachovské skály, Maloskalsko and Příhrazské skály, as well as the ruins of Trosky castle on top of two exposed basaltic plugs, are favoured tourist destinations, with the history of tourism dating back to the mid-19th century [18]. Later on, in 1951, in recognition of the values of the sandstone area, the area became the first Area of Protected Landscape in the former Czechoslovakia. The NE part is less varied and lacks similar landforms to those developed in Cretaceous sandstones. It does host interesting volcanic geosites providing evidence of different volcanic epochs [22], river gorges and mineralogical localities, as well as a few open-air exhibitions of local rock types, but is rather short of evident highlights, in comparison to rock landforms in the SW part.

The nomination dossier for the Bohemian Paradise Geopark [12] does not include a formal inventory of geosites, but only a brief description of more than ten localities, most visited and apparently considered most attractive. Among them, nine are complexes of rock landforms developed in Cretaceous sandstone, only four represent other phenomena and none are located in the NE part of the proposed geopark. Subsequently, a more detailed inventory was completed, resulting in the recognition of about 800 “geo-locations”, of which a few tens were selected as suitable resources to develop geotourism [23]. The map of geosites released in 2013 [24] indicates 67 localities within the boundaries of the geopark, including 25 in the NE part (37%), outside the sandstone area. Most of these are geological outcrops of volcanic rocks of different ages. This area also hosts one educational trail, along the gorge of Jizera River. Cultural heritage is diverse and spans many centuries. Among the highlights are the historical towns of Turnov and Jičín, preserved or ruined medieval castles (Kost, Trosky, Valečov, Frydštejn, Kumburk, Bradlec); some re-developed later as hermitage sites (Valdštejn) or Romantic ensembles (Vranov); and local museums. Most of these historical localities are also located in the sandstone part of the geopark.

The Bohemian Paradise UGGp is among the most visited areas in all of Czechia, with the annual number of visitors estimated to be well above 1 million (including day-trippers and owners of second homes) [25], which is the combined effect of its scenic qualities and the proximity of the capital city of Prague. However, tourism is clearly concentrated in the SW, sandstone part, especially during summer weekends [26], and sandstone rock cities are indicated as the most popular sites of geoheritage interest to visit. Most tourist facilities are also located in the sandstone part, clearly responding to the demand.

3.2. Harz–Braunschweiger Land–Ostfalen UNESCO Global Geopark

The Harz–Braunschweiger Land–Ostfalen UNESCO Global Geopark, located in central Germany and approved in 2004, is among the largest in Europe, covering more than 11,000 km2. Geographically and geologically, it has an evident dual nature, with the southern part being very different from the northern one. The south coincides with the Hercynian mountain massif of the Harz (Brocken, 1141 m a.s.l.), which is a young horst built of old basement rocks and Carboniferous granites. Characteristic landforms include elevated planation surface, granite tors (crags), deeply incised river valleys and extensive peat bogs [14,27]. Along the southern and western peripheries of the Harz, karst phenomena are extensively developed in dolomite and gypsum, as testified by numerous caves, sinkholes, disappearing streams and large springs [28,29]. Along the northern escarpment, in turn, a series of sandstone crags and walls are not only scenic spots, but are most important scientifically, documenting considerable deformation of the Earth’s crust just after the Cretaceous [30]. By contrast, the north is either lowland covered by thick Cenozoic and Quaternary deposits or includes low and subdued hill chains. The northern area has a fascinating geological history, which includes rising salt diapirs, deep-seated ground subsidence and multiple glaciation, but the evidence of these processes is more subtle and the sites lack the grandeur of relief present in the Harz.

This dichotomy is reflected in the distribution of sites of interest in the geopark [14]. As many as 169 such localities are listed, with 105 located in the Harz or its southern margin, 14 inside the immediate northern foreland and only 50 within the lowland/hilly northern part, despite the large surface area of the latter. Among the 50 listed localities, 8 are not geosites sensu stricto but local museums and information points. Geosites proper are mainly quarries and gravel pits.

Throughout the Harz–Braunschweiger Land–Ostfalen UGGp, cultural heritage is very rich, reminiscent of the complex and turbulent history of this part of Germany. Among the highlights are the World Heritage-listed medieval towns of Goslar, Quedlinburg and Lutherstadt Eisleben, the former constituting one property along with the abandoned copper, lead and tin mines at Rammelsberg and an innovative water management system developed to facilitate deep mining. But there are many further historical towns, churches and abbeys, castles and archaeological sites distributed across the area.

The Harz region, with its distinctive morphology and high relative elevation, has long been a popular tourist destination in central Germany. Old ore mines and some impressive landforms were already tourist destinations in the late 18th century. Both natural features (river gorges, bizarre rock outcrops, caves) and historical cities around the mountains attracted the interest of travellers. Consequently, numerous facilities were built to foster tourism, including the narrow-gauge railways to the summit of Brocken opened by the end of the 19th century. Divided by the political boundary during the Cold War era, some of the highest parts of the Harz were not accessible, but otherwise tourism continued to develop, particularly after the disappearance of political obstacles and re-unification of Germany. By the beginning of the 21st century, it was estimated that more than 2.5 million people visit the Harz annually and stay overnight, with an approximately 90% share of domestic tourists [31]. This number is likely to be considerably higher nowadays and one-day visits are undoubtedly very common.

3.3. Bakony–Balaton UNESCO Global Geopark

The Bakony–Balaton UNESCO Global Geopark, member of the GGN since 2012, is located in central–west Hungary. It extends over 3244 km2 and, as the name shows, includes two neighbouring areas: the Bakony mountains in the north and Lake Balaton with the adjacent upland in the south. In the south, the northern shore of Lake Balaton constitutes the border of the geopark (with one minor enclave on the southern shore). The adjacent Balaton Uplands are a hilly area, reaching 455 m a.s.l., geologically composed mainly of Triassic limestones and dolomites, but most striking are volcanic rocks of Pliocene age, which build isolated cones and tabular hills—remnants of ancient volcanic edifices [32]. Among them are the landmarks of the region: Badacsony, Szent György-hegy and the former basalt quarry of Hegyestű, developed as an open-air geological museum [33]. The Tihany peninsula hosts other volcanism-related landforms such as old geyser cones and maars [34]. Other geomorphological phenomena include karst (with a few caves accessible to the public) and picturesque sandstone crags. The northern part of the geopark encompasses part of the Bakony Range, which is higher than the Balaton Uplands (reaching 709 m a.s.l.), mostly forested and sparsely populated. Geologically, Mesozoic sedimentary formations prevail and Pliocene volcanic rocks are marginally represented. Consequently, striking landmarks in the form of volcanic hills are absent. Although the number of geosites, 45 in total, identified at the time of application to the GGN is similar in both parts of the geopark, those in the north are less scenic and only 2 were presented as being of international significance (including one inaccessible to casual visitors), as opposed to 12 with this status in the southern part. In addition, cultural assets are also non-uniformly distributed, mostly in the south (Benedictine abbey in Tihany, hot spring resort in Héviz, palace and gardens in Keszthely, old town of Veszprém, picturesque ruins of village churches and, last but not least, vineyards). This qualitative recognition of the non-uniform distribution of geo-resources is in agreement with the results of the quantitative geodiversity assessment [35].

From the perspective of tourism, the geopark consists of two different sub-regions, largely matching the division arising from geology and geomorphology. Lake Balaton is among the most popular tourist destinations in Hungary, with a string of densely built-up resorts along their shores [36]. The hills and forests immediately to the north (Balaton Uplands) are the natural area for outdoor activities for holidaymakers visiting the lake, with a dense network of hiking and biking trails. The Bakony Range, by contrast, is much less visited, and tourist infrastructure other than waymarked hiking routes is limited.

3.4. Serra da Estrela UNESCO Global Geopark

Estrela UNESCO Global Geopark, approved in 2020, covers 2216 km2 in central Portugal and includes the highest mountain massif in the mainland, Serra da Estrela (Torre, 1993 m a.s.l.). Morphologically, the mountains represent an extensive high-altitude plateau bounded by steep escarpments and deeply dissected by river valleys. They also bear a strong imprint of Pleistocene glacial processes, evident in cirques, long glacial troughs (U-shaped valleys) and moraines [37,38,39,40]. However, the territory of the geopark is not limited to Serra da Estrela as a geographical unit, but extends over the adjacent regions, such as lower but rugged mountains in schists, intermediate plateaus and piedmont zones. Geologically, granites are dominant and support many striking landforms such as tors (crags) and boulder fields, whereas other lithologies include schist, greywackes and hornfels along the contact with granite. From an administrative perspective, the geopark is composed of nine municipalities, among which only four include Serra da Estrela proper. This is an important observation, as it is Serra da Estrela that is the most recognized part of the geopark, hosting the most spectacular geoheritage and being most diverse.

In the nomination dossier of the Estrela Geopark, 124 geosites are listed and grouped into eight thematic categories [13,41]. Among them, localities related to glacial history are most represented (35, =28%), and these are exclusively located in the highest part of Serra da Estrela. Not only are they very important scientifically, but many are also very scenic, decisively contributing to the aesthetic appeal of the mountains and popularity among visitors. Although precise delimitation of the boundaries of Serra da Estrela would be arbitrary, it nevertheless constitutes less than one-fourth of the total geopark area (c. 450 km2), whereas about 75 geosites (=60%) are located within its limits. By contrast, large areas in the north host only about 20 geosites, mainly related to granite weathering.

The development of tourism in Serra da Estrela is relatively recent and began with the discovery of the most elevated parts for winter sports [41]. A few hiking trails were marked on the plateau and down the marginal escarpments, towards adjacent towns, but they were not much frequented. Car-based tourism was common, making use of a few paved roads towards and across the plateau. Peripheral parts were much less known and promoted. However, over time, the popularity of Serra da Estrela rose, and by the second decade of the 21st century the number of visitors annually was estimated to be around two million. Many are day-trippers and the average length of stay is only two days [13].

4. Results—Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark

4.1. The Origin of Geopark—A Brief History

The sequence of events and the history of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Geopark was comprehensively presented elsewhere [42], and therefore only a summary is offered here, to provide the context and explain the territorial extent. The beginnings date back to the early 21st century and the period after Poland’s accession into the European Union, when various European funds became available to foster regional development, especially in rural areas. Among the organizations eligible to apply were Local Action Groups (LAGs), associations of adjacent municipalities. In the study area, the Kaczawskie Partnership LAG was formed in 2005, including municipalities from both the mountainous (western) and lowland (eastern) part of the study area. The long-term development strategy placed a strong emphasis on tourism which would use various local resources as a basis to build tourist products. Realizing that remnants of ancient volcanism unify various municipalities within the LAG, and taking into account the uniqueness of this kind of geoheritage in Poland, the phrase “Land of Extinct Volcanoes” was selected as the official brand name of the region, and geotourism was considered one of the preferred types of tourism.

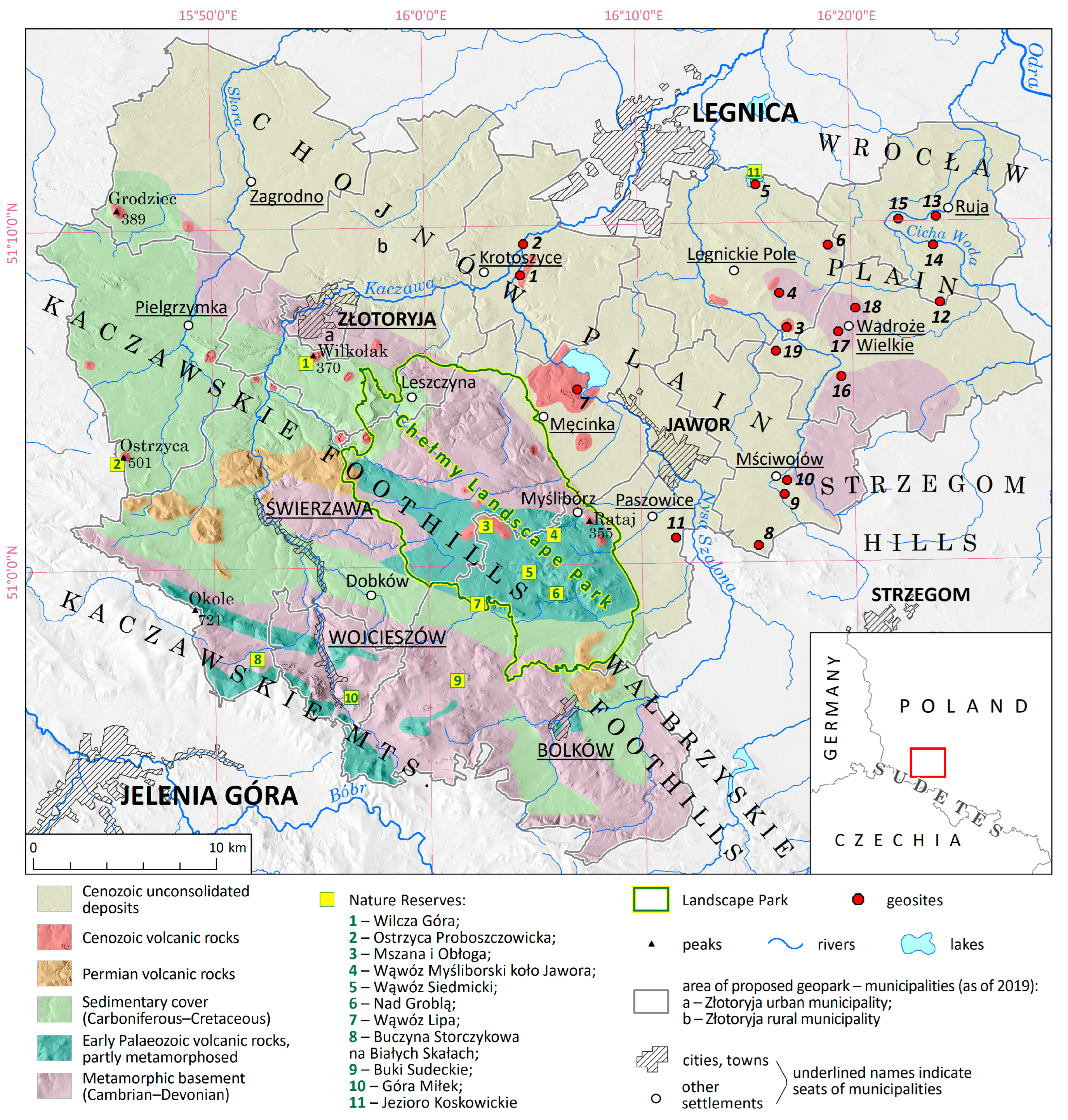

Over the years, the idea to apply for UNESCO Global Geopark status was developed and was approved in 2017 by representatives of all municipalities—members of the LAG. Thus, the boundaries of the future geopark were expected to be identical to the area covered by the respective municipalities, and these are presented in Figure 1. To fulfil one of the requirements for a UGGp, an inventory of geosites was commissioned for the LAG area, and the results of that work, executed in 2018–2019, provide the basic materials for this study. However, after the inventory was finalized, one of the municipalities withdrew its consent to be a member of the geopark, whereas another changed its status and is now a partner, not the constituting member. The application was submitted to the UNESCO Global Geoparks office in 2019, evaluated in late 2020 and again, after necessary improvements, in late 2022.

Figure 1.

Geological and relief diversity of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. Note the sharp line marking the SW extent of Cenozoic unconsolidated deposits, which divides the territory into two parts, unequal in terms of geoheritage and geodiversity resources. Inventoried geosites are shown only for the lowland (eastern part) and numbered as in Table 3.

4.2. Location, Geodiversity and Geoheritage

The Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark (LEV AG) is located in south-western Poland and covers a total area of 1263 km2 (Figure 1). With respect to the main geographical regions of this part of Europe, its area is heterogeneous, straddling the boundary between uplands/low mountains in the south-west and undulating plains with occasional isolated low hills in the north-east [42]. The western part belongs to the mountain range of the Sudetes (300–723 m a.s.l.), whereas the eastern part encompasses the Silesian Lowland and the Sudetic Foreland (150–300 m a.s.l.). For the latter, terms such as “fore-mountain part”, “lowland part” and “eastern part” will be used interchangeably in this paper. The dividing line is distinct, especially in the south, and associated with the fault-generated escarpment of the Sudetes, even though the escarpment itself is rather low, only locally exceeding 150 m in height [43]. These topographic and altitude differences are further emphasized by land cover and land use. The low-lying eastern part is almost entirely deforested and is mainly agricultural land (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Predominantly agricultural land use in the eastern, lowland part of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. In the Kaczawskie Foothills to the west (lower left corner), the percentage of forested area increases. Source of image: Google Earth (https://about.google/brand-resource-center/products-and-services/geo-guidelines/; accessed on 15 December 2023).

The visual differences indicated above emerge from different pathways of long-term geological evolution. The western part has long been an area of sedimentation (late Palaeozoic and Mesozoic) and extensive volcanism, resulting in a complex rock record spanning most of the last 0.5 billion years, with many volcanic edifices scattered across the area [16,44,45,46]. In the late Cenozoic, tectonic uplift caused relief differentiation and enhanced erosion, giving rise to more relief diversity, including specific rock-controlled landforms such as cuesta ridges, water gaps and crags [46]. By contrast, the rock record in the eastern part is less diverse and lacks pre-Cenozoic sedimentary rocks, and volcanic outcrops are few and indistinct. In the Pleistocene, large tracts of terrain were covered by the continental ice sheet, whose legacy includes a blanket of glacigenic deposits (till, gravel and sand) which hides erosional bedrock morphology that existed prior to glaciation [46,47,48]. However, as the age of glaciations is distant (ca. 450 ka and 200–180 ka), sufficient time has elapsed to smooth the topography and the formerly glaciated part of the LEV AG lacks landforms typical of fresh lowland glacial topography such as numerous lake basins, tunnel valleys, chains of moraine hills, etc.

Thus, geodiversity and geoheritage resources of both parts of the LEV AG are not only very different in terms of origin, but have different potentials to attract tourists. Table 2 lists the key resources for both sectors of the geopark and reveals evident inequalities, further explored in Section 4.4. Among them are rocks of volcanic origin and associated landforms, highlighted as the key asset and brand of the geopark, including its official name, and promoted accordingly.

Table 2.

Most important resources supporting tourism development in the mountainous (western) and fore-mountain (eastern) parts of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark.

In the Sudetic part of the LEV AG, three periods of volcanism are represented in the rock record. The legacy of the most distant Early Palaeozoic volcanism includes thick packages of altered submarine basaltic lavas (now greenschists), emplaced in the incipient ocean floor setting, with occasionally preserved pillow lava structures [49], as well as products of siliceous volcanism (trachytes) [50]. They are exposed at the surface either in rock crags on mountain slopes and crests, or within the steep rocky sides of river gorges [46]. The second volcanic epoch occurred in the Permian in terrestrial conditions and is represented by both siliceous (rhyolites) and intermediate (trachyandesites) volcanic rocks, forming steep-sided domes and local crags. Permian volcanic rocks are widely known for their colourful agates, long since collected by professional and amateur mineralogists. Between 30 ka and 20 ka, the area experienced a third phase of volcanism, with basaltic lavas and tuffs as the dominant products of volcanic activity. Many basaltic necks are present, some with eye-catching conical or dome shapes, whereas numerous quarries exposed striking columnar jointing patterns in different arrangements [45,51]. By contrast, neither Early Palaeozoic greenschists nor volcanic rocks of Permian age occur in the eastern, lowland part of the LEV AG, whereas basaltic lavas are mostly exposed in inaccessible working quarries.

4.3. Natural History and Cultural Heritage

The spatial distribution of sites of biological significance and, potentially, value for tourism development is similar to the distribution of geodiversity and geoheritage resources, being very unequal between the two parts of the LEV AG. In the western part, as many as ten protected areas (nature reserves) have been established (Figure 1) and although the primary conservation targets are natural forests and floral communities, each protected area includes localities of geoscientific significance, mainly bedrock crags. Even though not every part of the reserves can be visited due to nature conservation regulations, their values can be appreciated from existing marked trails. Landscape Park (Figure 1) is another legal category of nature protection in Poland, and one was established in the central part of the region in 1992, long before the activity of the LAG commenced. Furthermore, valuable forest communities occur outside the protected areas, particularly including thermophilous oak forests of considerable aesthetic value [52]. In the fore-mountain part, in turn, a long history of agricultural use taking advantage of soils and relief has resulted in the almost complete disappearance of forests, except for localized patches of woodland on steeper slopes and along river banks and grasslands (Figure 2). The only protected area includes the Koskowickie Lake, with large reed communities along the shores and bird habitats. Otherwise, there are few reasons to establish nature protection areas. However, valuable biodiversity elements can also be found in a few old manor parks and these include monumental trees and alleys.

Cultural heritage, by contrast, is more evenly spread throughout the LEV AG. The most valuable single object, the 17th century Church of Peace (Figure 3a), part of a World Heritage property (since 2001), is located in the town of Jawor, in the fore-mountain part. The town itself hosts further historical buildings such as medieval churches, remnants of city walls, a former medieval castle (even though much altered later), an imposing town hall and a regional museum. The Baroque former Benedictine abbey in Legnickie Pole is another historical structure of considerable value, additionally associated with the famous battle with the Mongols in 1241 (Figure 3b). Historical buildings of lower rank, but still interesting sightseeing spots, can be found in numerous villages, and these include rural churches in different styles, elaborate old gravestones exposed in churchyards, palaces and manors, and impressive examples of monumental farmsteads (Figure 3c,d). The fore-mountain part also has numerous registered archaeological sites (hilltop or valley floor forts with ramparts and/or moats) whose potential is poorly realized and largely untapped (Figure 3e). Adjacent to the Kaczawa River, one can also find monuments commemorating the Battle at the Kaczawa River, held during the Napoleonic Wars in 1813 (Figure 3f).

Figure 3.

Cultural heritage of the eastern part of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. (a) World Heritage Church of Peace in Jawor; (b) Baroque Benedictine Abbey in Legnickie Pole; (c) Palace in Luboradz (under renovation); (d) Renaissance sandstone epitaphs attached to the wall of a village church; (e) view towards a medieval hillfort site in Mierczyce; (f) monument commemorating the Battle at the Kaczawa River in 1813.

Cultural heritage in the Sudetic part of the LEV AG is also very rich, with both similarities and differences in comparison with the mountain foreland, but disparities in the distribution of resources are not so evident. Specific to the mountainous part are hilltop castles, whose origins date back to medieval times, with subsequent expansions and alterations (e.g., Bolków, Świny, Grodziec). Impressive gothic churches have survived in the towns of Złotoryja and Świerzawa, whereas more modest structures of this kind are present in most villages. There are also numerous countryside residences (palaces, manors), some in ruins, but others recently restored. Of particular interest in the context of geotourism are relicts of ancient mining, with most known localities in Leszczyna (former quarries of sandstone and limestone, remnants of copper ore mining, reconstructed kilns) and Złotoryja (an adit open to tourists). The region used to be famous for gold prospecting and mining, but the surface remnants (pit-and-mound topography) are poorly visible. However, gold searching traditions are being recreated in the form of amateur gold panning and gold panning championships [42].

4.4. Geosites and Their Evaluation

The geosite inventory and assessment for the territory of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark includes 130 sites [15]. Among them, only 19 (14.5%) are located in the fore-mountain part, even though in terms of surface area both parts are almost equal (Figure 1). This uneven participation results from a much less varied topography and the concealment of most of the bedrock under unconsolidated late Cenozoic deposits, which themselves are poorly exposed even though they may bear an interesting record of major environmental changes, including glaciations. Simply speaking, there are much fewer rock outcrops, striking landforms and scenic spots in the fore-mountain part.

The inventoried geosites represent different themes (Figure 4), with volcanic geoheritage—a key asset of the LEV AG—present at five localities (ca. 25%) (Table 3). By contrast, in the mountainous part of the geopark, various aspects of volcanism are addressed in 37 localities (33%). Moreover, the most attractive locality from both a scientific and scenic perspective (Table 3, no. 3), which scored 14 points, is formally inaccessible due to restrictions imposed by the landowner (Figure 4a), whereas another basalt quarry nearby is flooded and the rock outcrops are hardly accessible (no. 19). Access limitations apply to one quartz and one granite quarry (nos. 6 and 11). Several other sites are rather inconspicuous and scored low due to limited information in the scientific literature; lack of additional values, including scenic qualities; and poor access.

Figure 4.

Examples of geosites from the eastern part of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. (a) Columnar jointing in a lava flow (geosite no. 1); (b) flooded gneiss quarry (geosite no. 18); (c) basalt crags (geosite no. 7); (d) hilly postglacial landscape (geosite no. 13).

Table 3.

Geosites in the eastern part of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark and results of their semi-quantitative evaluation (data from [15]). Location of individual geosites in Figure 1.

A comparison with the geosites inventoried in the mountainous part of the LEV AG confirms that the fore-mountain part performs less well and resources are limited (Table 4). Although the range of scores is almost identical and the mean score is only higher by one point in the mountainous part, there is a striking difference with respect to the number of geosites scoring 10 and above. There are only two such localities in the foreland (including one formally inaccessible) versus more than thirty in the mountainous part. Among them, seven scored 13 and over, including four volcanic geosites which are all easily accessible. Here, it is also appropriate to consider one major development that took place in 2023, after the evaluation was performed. The former basalt quarry at Mt. Wilkołak was inaccessible at the time evaluation was performed and only a long-abandoned part of the quarry, poorly managed despite protection status and available for viewing, was subject to assessment and scored 11. However, rehabilitation of the quarry was under way and its final opening to the public occurred in May 2023, with well-designed infrastructure present [53]. Re-evaluation using the same criteria would result in a score of 17—the highest among all geosites in the LEV AG. This would not change the general picture emerging from Table 4, but enhances contrasts between the two parts of the geopark, where the most attractive sites tend to cluster in the west.

Table 4.

Results of semi-quantitative evaluation of geosites in two parts of the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark (data from [15]).

4.5. Current Facilities and Developments for Tourism

Current facilities for visitors are still very limited at the inventoried geosites in the fore-mountain part of the geopark (see Table 3). In a few localities, information panels were erected (some reflecting local initiatives, predating coordinated activities of the LEV AG), but the majority of sites lack signposting or on-site information. Some panels have been since vandalized and have not been (yet?) re-established. However, visitors interested in geoheritage can download the relevant documentation cards for each geosite from the geopark website. Next to the disused gravel pit in Mściwojów (site no. 10), not interpreted as being on-site itself, an open-air exhibition of common rock types from the region was set up. Along with a panel at the nearby viewing tower, these two localities are on a local nature trail. A few quarries subject to evaluation as geosites have restricted access due to ongoing operation, despite their potential significance for geotourism.

The accessibility of cultural heritage is, in general, better, and the history of many local landmarks (historic churches, manors) is shown on information panels erected in village centres. Even if the buildings themselves cannot be entered (or just sporadically), the grounds (i.e., the area inside the walled ecclesiastical compound) are normally open and, for instance, old gravestones can be inspected. Others can be visited virtually, taking “tours” available on the websites of respective municipalities. The major town in the region, Jawor, caters well for tourists, who can visit the World Heritage Church of Peace, Regional Museum, town hall and old castle. The former Benedictine Abbey in Legnickie Pole is also open to the public, although opening hours are limited. On the other hand, archaeological sites (walled settlements) are practically neglected and known to very few tourists.

Facilities for active tourism such as hiking and biking trails exist, but are not particularly extensive. The most dense network has been established in the west, where trails follow the valleys of the Kaczawa and Nysa Szalona rivers and join local sites of historical interest. The regional long-distance “Trail of Extinct Volcanoes” begins in the fore-mountain area and goes towards the western upland, but lacks geological spots of interest (it skirts one former quarry, which is formally off-limits). By contrast, agricultural flatlands in the east do not have trails, except a section of Saint James Way.

This low level of development contrasts with much more extensive and varied facilities in the mountainous part, which includes two educational centres (one managed by the geopark, another one by the Chełmy Landscape Park), a few well-developed volcanic geosites, several educational nature trails focused on geoheritage, open-air rock exhibitions, old mining works made available to tourists, panoramic viewing spots, a dense network of hiking trails and numerous sites of historical interest [42].

5. Managing Non-Uniform Distribution of Resources in Geoparks—Discussion and Recommendations

5.1. Lessons from Selected UNESCO Global Geoparks

Each of the four well-established UNESCO Global Geoparks examined here to provide inspiration for the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark deals with spatial inequalities in the distribution of geoheritage and geodiversity resources. Consequently, tourism is also non-uniformly distributed in space and, in addition, shows significant seasonal variability with strong weekend peaks. Weekend tourism is particularly popular in the Bohemian Paradise UGGp due to the proximity of the capital city to Prague. This distribution pattern results in the phenomenon of overtourism in the most popular places, which also happen to be also among the most valuable from a geoheritage perspective (sandstone rock cities, Trosky twin volcanic plug with castle ruins) [25,26]. In the Estrela UGGp, in turn, there is easy access to the highest peak of Torre, which is also the highest in mainland Portugal, so it is an obvious site to visit for domestic tourists. In winter, the Torre area turns into a ski arena. The number of visitors to Serra da Estrela is estimated to reach 2 million per year [13], which causes serious environmental stress in the most elevated parts of the geopark, and simultaneously leaving the peripheral areas much less visited. Paradoxically, this focused interest does not seem to be primarily caused by specific interest in geoheritage, but by the general appreciation of scenery and factors named above. The motivations of visitors arriving at the Bohemian Paradise UGGp are somewhat similar [54]. Most respondents indicated a willingness to relax close to nature, whereas cognitive aspects related to Earth sciences were not so important, even though the most visited localities provide excellent educational opportunities and at least some of them have appropriate interpretation facilities on site. In these circumstances, confronting the distribution of geoheritage/geodiversity resources, spatiotemporal characteristics of tourist flows and predominant motivations, it is really difficult to achieve a more balanced pattern of tourism if geoheritage and geodiversity are considered the main resources. This statement is probably valid even for the eastern part of the Bohemian Paradise UGGp, where various unique aspects of Late Palaeozoic volcanism—absent in the heavily visited sandstone part—may be explored either in the field or through mineral collections in local museums [22,55].

In all four UGGps, there seems to be a clear understanding of these constraints. Therefore, strategies to foster tourism development in sectors of geoparks with a less striking record of Earth history also use other resources, concepts and tools, although geoheritage aspects remain emphasized wherever possible. General trends include the promotion of active tourism, especially biking; cultural tourism, including culinary tourism based on local products; and organization of events. In fact, all of these can provide a connection to geoheritage and geodiversity. For instance, the brochures in the “Landmarke” series produced by the Harz–Braunschweiger Land–Ostfalen UGGp for particular parts of the geopark (more than 30 as of 2023) promotes geoheritage sites alongside historical and cultural objects, among which many are linked to Earth resources (buildings made of local stone, ancient mining remains, archaeological sites). A similar strategy is adopted in the Estrela UGGp, where Roman and medieval archaeological sites, as well as traditional architecture using granite and schist, are highlighted. In the Bakony–Balaton UGGp, wine tourism is being developed as the hills overlooking Lake Balaton are among the best-known wine regions in Hungary [56] and the very notion of terroir includes numerous connections to abiotic nature, offering various interpretation opportunities [57]. Culinary tourism, currently highly promoted in geoparks by means of the Geofood project [58], is highlighted in the Estrela UGGp, where more than 100 local products are advertised, including honey, bread, cakes, liquors and cheese [59]. A wide range of events is being organized in the Bohemian Paradise UGGp [60].

An important part of long-term strategy seems to be shifting promotional focus from the already well-known areas, even though they may be the most scientifically valuable parts of geoparks, to other parts, or at least giving them equal standing. Thus, in the Estrela UGGp, action is being undertaken aimed “at distributing visitors and economic outcomes from plateaus to the piedmonts” [13]. Opportunities for tourism include, apart from the cultural and culinary tourism mentioned above, spa tourism based on four localities with thermal waters, multi-day trekking, mountain biking and relaxing at fluvial beaches [61]. The development of app platforms to show the resources of a territory without explicitly differentiating them as more and less valuable may be particularly helpful. In the Bohemian Paradise UGGp, a SmartGuide platform and Artificial Intelligence are used to promote less visited areas by means of customized audio guides [62]. Another method is web-based materials, released each month, presenting a selected geoheritage site within the geopark.

Finally, in each geopark, education aimed at raising awareness of the value of local heritage among the communities plays an important role. Thus, in the Bakony–Balaton UGGp, special courses are organized for those who would like to become guides or educators in the geoparks [63]. In the Estrela UGGp, the “Geopark Ambassadors” programme is carried out, primarily aimed at schools (teachers, schoolchildren) in the geopark area, whereas the “Geoheritage Stewards Programme” aims to engage volunteers to become guardians of geosites located nearby and involves a special short course about Earth heritage [13].

5.2. Challenges and Opportunities for the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark

Non-uniform distribution of resources for geotourism in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark is evident, reflected in the overall qualitative assessment of geodiversity, disparities in the number of inventoried geosites, and their performance in the semi-quantitative evaluation. Although in a few cases there is room to increase scoring by improving site conditions and access (e.g., nos. 1 and 16—Table 3), it is suggested that sites which scored below 10 are not very likely to appeal to a wider audience and will remain either very local attractions or sites of interest for highly motivated geotourists and scientists. Among two sites which scored above 10 (Table 3), the disused basalt quarry is formally off-limits, and until access issues are solved with the landowner, it cannot be promoted, whereas another one, the Koskowickie Lake, is a nature reserve and bird sanctuary, and hence is not suitable for frequent tourist visits. A few other sites with certain geotourist potential gradually lose their educational values and attractiveness, even for dedicated geotourists, due to vegetation growth reducing visibility and access. An important observation is also that most geosites, if classified by theme, have equivalents in the western part of the geopark. One theme missing in the western part is granite as a rock, a stone resource and an important contributor to geomorphology (site nos. 8 and 11; Table 3). However, specifically in the LEV AG, the granite area is small, its morphology is inconspicuous and just beyond the boundaries of the geopark is the municipality and town of Strzegom (Figure 1), known as the centre of the granite quarrying industry, whose tourist promotional strategy emphasizes granite (using the phrase “Granite Heart of Poland”). Further to the south-east, some 50–60 km away but still within the broader fore-mountain region, granite mining heritage is promoted as one of the main resources of the Sudetic Foreland national geopark [64,65]. Thus, the emphasis on granite does not seem a promising way of promoting geotourism in the fore-mountain part of the LEV AG, although cooperation with the neighbouring municipality, even though from outside the geopark, is certainly an option worth exploring.

A possible window of opportunity is to focus on the heritage of the Quaternary, especially ice ages, ice-sheet advances and associated deposits and landforms. A few geosites from the inventory (nos. 9, 10, 13) have glacial history as their main or ancillary theme, even though neither the landforms nor outcrops can be considered spectacular. However, this is a common problem in glaciated lowlands of Central Europe, where landform complexes of outstanding scientific value which are impressive if examined on digital elevation models look rather inconspicuous from a ground perspective [66,67,68,69]. To capitalize on these resources, an engaging interpretation programme would have to be implemented, ideally aided by (or even centred upon) another interpretation centre of the geopark located in the eastern part of the area, whose main purpose would be to explain the glacial past, connected with contemporary issues of long-term and short-term climate change. This, however, would require considerable financial investment and it needs to be observed that the LEV AG already manages one educational centre in the western part of the area, whereas another centre of environmental education is run by the Chełmy Landscape Park and it seems that the offer is, for the time being, sufficient. Glacial legacy in the form of erratic boulders used as building stones or assembled next to village churches for ornamental reasons may also provide a link to cultural heritage, as will be developed later.

Summing up, attempts to build local (geo)tourist products solely on existing geoheritage and geodiversity resources may not prove successful for reasons independent of local stakeholders, but arising from the characteristics of the area. However, exploration of the ABC concept [4] may result in various solutions and opportunities for the area short of evident geoheritage and geodiversity resources. Connections in the study area between history and cultural heritage on one hand, and geoheritage and geodiversity on the other one, include the following:

- Historical events, particularly the famous battles of 1241 with the Mongol invaders and of 1813 during the Napoleonic Wars (the Battle on the Kaczawa River, involving 70,000 French troops and 90,000 troops of the Russian–Prussian coalition). Although little is known about the former and it largely remains in a symbolic sphere, the latter has been the subject of numerous historical studies [70] and is recalled by various monuments scattered through the former battlefield (Figure 3f) [71]. The contributing role of the Kaczawa River flood and terrain conditions in the course of the battle can be explored as examples how the natural environment influences military actions, and an inventoried geosite (no. 2) is located at the confluence of the Kaczawa and Nysa Szalona rivers, offering an opportunity to learn about fluvial processes and landforms, including their relevance to human history. The battle is commemorated each year in a large-scale historical reconstruction, one of the oldest events of this kind in Poland.

- There are several important archaeological sites in the area, recognizable in the landscape as flattened hilltops, circular or oval ramparts and dry moats. They occupy distinctive geomorphic settings such as valley shoulders, upland spurs and solitary bedrock hills, allowing for the development of an interpretation program focused on nature–human interactions, especially terrain use, in early medieval times. Three of them are located in reasonably close vicinity to one another, next to the Kaczawa River, within a distance of 5–6 km, offering the opportunity of a thematic trail.

- Locally available rocks, both present in situ and Scandinavian erratics, were used as building and ornamental stones and, in the case of sandstones from the western part of LEV AG, as tombstones (epitaphs). They can be examined at various local buildings of historical interest, especially at village churches and adjacent cemeteries.

- Some watercourses may be followed by recreational trails, which might include interpretation panels, quests or other engaging forms of participation, thematically focused on linkages between geomorphic and hydrological phenomena, vegetation patterns and human use of surface waters.

- The Koskowickie Lake is one among only a few natural lakes preserved in the region (and the only one within the boundaries of the LEV AG), whereas historical documents indicate that there were more lakes in the past, but they were drained and converted into agricultural land. Linkages between land use, societal needs and geodiversity loss can be explored using this example.

Besides (geo)tourist products involving geoheritage/geodiversity resources, the fore-mountain part of the LEV AG may use other resources, in accordance with one of the overarching goals of geoparks to foster sustainable, educational tourism for the benefit of local communities. Architectural heritage is an obvious capital, especially in the town of Jawor, with its reasonably well-preserved historical old town, and in Legnickie Pole, but historical palaces and manors, some inside historical parks, are further local spots of interest. Likewise, historical rural churches may attract attention (in some villages, there are two, once belonging to different denominations), allowing the development of interpretation programmes about the region’s turbulent cultural history since the 17th century. The long history of agriculture in the region, benefitting from fertile soils, is another possible theme to develop as part of the regional tourist product, which would also contribute to raising awareness about the significance of soils as a resource, thus providing another geo-cultural link. Actually, soils were long generally neglected within geoheritage issues, but this has recently changed and studies are being published addressing this geodiversity component as well [72,73]. The challenge is to make these localities more visible and accessible, although some action has already been undertaken. Guided tours under the name “Make your day with the geopark” are being organized in the less known parts of the LEV AG, including the lowland area, and are attended mainly by local inhabitants. This initiative appears crucial for raising awareness among the local communities, which seems to be a necessary step before not-so-obvious values are more widely promoted outside the geopark. A recommended complementary action would be to extend a programme of various participatory activities for tourists (e.g., ceramic, beekeeping, herbal, gingerbread making workshops), already well implemented in the mountainous part and popular particularly among families with children [42], but largely missing in the lowland part.

As another promising way forward in geoeducation, opportunities offered by modern technologies (e.g., virtual tours and virtual geosites based on UAV surveys, 3D models and dedicated WebGIS platforms; augmented reality) [74,75,76] should be further explored, particularly in respect to inaccessible and poorly accessible places such as the interiors of historical buildings or working quarries. Virtual flights over larger territories, supported by relevant commentaries highlighting relationships between nature and humans, may in turn be an attractive means to become acquainted with areas which lack singular spectacular sites. However, one should not forget that the idea of a geopark is primarily to bring visitors to the area rather than to offer a substitute.

Finally, an action that could help is to extend the network of waymarked routes, both for hikers and cyclists, which are of very low density at the moment. Although the lowland nature of the terrain and its predominantly agricultural use make it rather an unlikely area for long-distance hiking, recreational cycling is becoming ever more popular in Poland, especially in the vicinity of larger cities. Examples of geotourist cycling routes have been presented in the literature [77,78] and may become inspirational for the LEV AG.

6. Conclusions

The non-uniform distribution of geoheritage and geodiversity resources in geographical space imposes obvious constraints on the development of geotourism and geoeducation, facilitating it in some areas, whereas other regions are much less suitable. Geoparks, including UNESCO Global Geoparks, are territorial organizations whose primary aim to develop sustainable tourism based on these resources and which need to have geoheritage of considerable value. For UGGs, it is actually mandatory that this heritage is “of international significance”. Nevertheless, even within geoparks, geoheritage sites may not be evenly spread, with some sectors of geoparks having much more sites of interest than the others. This creates a challenge from a management perspective, especially given the overarching goal of a balanced, sustainable development of a territory, but may also be considered as an opportunity. For parts of geoparks with less obvious sites of geoheritage interest, the UNESCO Global Geopark brand can become a vehicle for promotion and development. However, specific pathways of this development need to be identified and prioritized, and adjusted to the available resources.

In this paper, using several examples, we have shown that the non-uniform distribution of geoheritage and geodiversity resources is real, and areas may exist within geoparks where geodiversity and geoheritage resources are less abundant. These areas require specific strategies to reach the goals of geoparks. Although some geoscience themes are worth exploring for geotourism, especially if they complement the main values of a geopark, it is argued that the focus is better centred around linkages between abiotic and cultural heritage, local history, active tourism and events. Geoheritage may and should be promoted, but the relevant geosites are unlikely to be the main attraction for tourists. The Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark in south-western Poland is a particularly challenging area, as it integrates the western part of high geodiversity and numerous geosites of international interest with the eastern part of subdued topography and only a few obvious geosites of wider interest. However, its rich architectural heritage, archaeological sites, intangible legacy of major battles from historical times, largely unspoilt rural countryside and good communication network provide opportunities to develop tourism and geoeducation consistent with the goals of geoparks, even though more modest in terms of the number of visitors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M. and E.P.-M.; methodology, P.M. and E.P.-M.; investigation, P.M. and E.P.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M. and E.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, P.M. and E.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Blanka Nedvědická and Fábio Loureiro for providing further information about the ongoing activities of the Bohemian Paradise UGGp and Estrela UGGp, respectively. Kacper Jancewicz is thanked for preparing Figure 1. We are also indebted to the four journal reviewers whose various comments helped us to clarify some of the issues raised in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zouros, N.C. European Geoparks Network: Transnational collaborations on Earth heritage protection, geotourism, and local development. Geotourism 2008, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brilha, J. Geoheritage and Geoparks. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 323–335. [Google Scholar]

- Gulas, O.; Vorwagner, E.M.; Pásková, M. From the orchard to the full bottle: One of the geostories of the Nature & Geopark Styrian Eisenwurzen. Czech J. Tour. 2020, 8, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M.; Zelenka, J.; Ogasawara, T.; Zavala, B.; Astete, I. The ABC concept—Value added to the Earth heritage interpretation? Geoheritage 2021, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brockx, M.; Semeniuk, V. Geoheritage and geoconservation—History, definition, scope, and scale. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2007, 90, 53–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: The backbone of geoheritage and geoconservation. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E. Geosite. In Encyclopedia of Geomorphology; Goudie, A.S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E. Geomorphosites: Definitions and characteristics. In Geomorphosites; Reynard, E., Coratza, P., Regolini-Bissig, G., Eds.; Pfeil Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2009; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. The scope and nature of geotourism. In Geotourism; Dowling, R.K., Newsome, D., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- An Application for European Geopark Status for the Aspiring Bakony–Balaton Geopark Project Hungary. Available online: http://geopark.hu/EGN_Application/BBGp_Application_web.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Adamovič, J.; Cílek, V.; Mikuláš, R.; Řídkošil, T. Geopark of the Czech Republic for Inscription in the UNESCO Geoparks Networks; Bohemian Paradise: Prague, Czech Republic, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, G.; de Castro, E.; Loureiro, F.; Patrocínio, F.; Firmino, G.; Gomes, H.; Fernandes, M.; Forte, J. Aspiring Geopark Estrela. In Application Dossier for UNESCO Global Geopark; Estrela Geopark: Torre da, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Röhling, H.-G.; Tanner, D.; Wilde, V.; Zellmer, H. (Eds.) Geopark Harz Braunschweiger Land Ostfalen. In The Classic Square Miles of Geology; Geopark Harz.Braunschweiger Land.Ostfalen: Königslutter–Quedlinburg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Inwentaryzacja Geopunktów na Obszarze Partnerstwa Kaczawskiego. 2019. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1jVK7xISZp5fcRBh1whLjf_pt_6QYXcOf/view (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Różycka, M.; Migoń, P. Customer-oriented evaluation of geoheritage—On the example of volcanic geosites in the West Sudetes, SW Poland. Geoheritage 2018, 10, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: A review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovič, J.; Mikuláš, R.; Cílek, V. Sandstone districts of the Bohemian Paradise: Emergence of a romantic landscape. Geolines 2006, 21, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mertlik, J.; Adamovič, J. Bohemian Paradise: Sandstone landscape in the foreland of a major fault. In Landscapes and Landforms of the Czech Republic; Pánek, T., Hradecký, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Härtel, H.; Cílek, V.; Herben, T.; Jackson, A.; Williams, R. (Eds.) Sandstone Landscapes; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Škvor, J. Makroreliéf a mezoreliéf Prachovských Skal. Acta Univ. Carolinae Geogr. 1982, 17, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mencl, V.; Bubal, J.; Stárková, M. The volcanic history of the UNESCO Global Geopark Bohemian Paradise. Geoconserv. Res. 2023, 6, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark Annual Reports 2016–2019. Available online: www.geoparkceskyraj.cz (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Bohemian Paradise Geopark; Map of Geosites with Explanation; Bohemian Paradise Association: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013.

- Drápela, E. Geoheritage and overtourism: A case study from sandstone rock cities in the Czech Republic. In Visages of Geodiversity and Geoheritage; Kubalíková, L., Coratza, P., Pál, M., Zwoliński, Z., Irapta, P.N., van Wyk de Vries, B., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publications: London, UK, 2023; Volume 530, pp. 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boháč, A.; Drápela, E. Overtourism hotspots: Both a threat and opportunity for rural tourism. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanle, A. Meyers Naturführer, Harz; Meyers Lexikonverlag: Mannheim, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, S. Gypsum karst of Germany. Intern. J. Speleol. Spec. Iss. 1996, 25, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubrich, H.-P.; Kempe, S. The Permian gypsum karst belt along the southern margin of the Harz Mountains (Germany). Tectonic control of regional geology and karst hydrogeology. Acta Carsologica 2020, 49, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, C.; Schultz, R.A. Fault damage zone origin of the Teufelsmauer, Subhercynian Cretaceous Basin, Germany. Intern. J. Earth Sci. Geol. Rundsch. 2013, 102, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, T.; Knolle, F.; Steingaß, F.; Hagen, K. Ein neues Leitbild für die Nationalparkregion Harz im Rahmen der Europäischen Charta für nachhaltigen Tourismus in Schutzgebieten. In Zu Besuch in Deutschlands Mitte. Natur—Kultur—Tourismus; Reeh, T., Ströhlein, G., Eds.; Universitätsverlag: Göttingen, German, 2006; pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gadányi, P. Buttes in the Tapolca Basin. In Landscapes and Landforms of Hungary; Lóczy, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Harangi, S.; Korbély, B. The basaltic monogenetic volcanic field of the Bakony–Balaton UNESCO Global Geopark Hungary: From science to geoeducation and geotourism. Geoconserv. Res. 2023, 6, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veress, M.; Gadányi, P.; Tóth, G. Thermal spring cones of the Tihany Peninsula. In Landscapes and Landforms of Hungary; Lóczy, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pál, M.; Albert, G. From geodiversity assessment to geosite analysis—A GIS-aided workflow from the Bakony–Balaton UNESCO Global Geopark, Hungary. In Visages of Geodiversity and Geoheritage; Kubalíková, L., Coratza, P., Pál, M., Zwoliński, Z., Irapta, P.N., van Wyk de Vries, B., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publications: London, UK, 2023; Volume 530, pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulcsú, R.; Csilla, M. The trends of the lake tourism and results of Balaton research. Stud. Mundi Econ. 2018, 5, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daveau, S. Structure et relief de la Serra da Estrela. Finisterra 1969, 7–8, 33–197. [Google Scholar]

- Daveau, S. La glaciation de la Serra da Estrela. Finisterra 1971, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migoń, P.; Vieira, G.T. Granite geomorphology and its geological controls, Serra da Estrela, Portugal. Geomorphology 2014, 226, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.; Nieuwendam, A. Glacial and periglacial landscapes of the Serra da Estrela. In Landscapes and Landforms of Portugal; Vieira, G., Zêzere, J., Mora, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.; Emanuel de Castro, H.; Gomes, F.; Loureiro, M.; Fernandes, F.; Patrocínio, G.; Firmino, G.; Forte, J. The Estrela Geopark—From planation surfaces to glacial erosion. In Landscapes and Landforms of Portugal; Vieira, G., Zêzere, J., Mora, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Promoting and interpreting geoheritage at the local level—Bottom-up approach in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes, Sudetes, SW Poland. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migoń, P.; Łach, J. Geomorphological evidence of neotectonics in the Kaczawa sector of the Sudetic Marginal Fault, Southwestern Poland. Geol. Sudet. 1998, 31, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Wocke, M.F. Der Basalt in der Schlesischen Landschaft. Veröffent Schles Gesell Erdk. 1927, 5, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Birkenmajer, K. Bazalty dolnośląskie jako zabytki przyrody nieożywionej. Ochr. Przyr. 1967, 32, 225–276. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P. Wybrane formy rzeźby terenu w sudeckiej części Geoparku Kraina Wygasłych Wulkanów (pd.-zach. Polska). Landf. Anal. 2021, 40, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyszkowski, D.; Czech, A. Kierunki nasunięć lądolodu plejstoceńskiego na północnym obrzeżu Wzgórz Strzegomskich, Przedgórze Sudeckie. Przegl. Geol. 1995, 43, 647–651. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, A.; Makoś, M.; Pitura, M. New insights into the glacial history of southwestern Poland based on large-scale glaciotectonic deformations—A case study from the Czaple II gravel pit (Western Sudetes). Ann. Soc. Geol. Polon. 2018, 88, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocholski, A.; Jerzmański, J. Zabytki paleowulkanizmu na Dolnym Śląsku w świetle ochrony przyrody. Ochr. Przyr. 1975, 40, 291–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kryza, R.; Muszyński, A. Pre-Variscan volcanic-sedimentary succession of the central southern Góry Kaczawskie, SW Poland: Outline geology. Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 1992, 62, 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P.; Pijet-Migoń, E. Overlooked geomorphological component of volcanic geoheritage—Diversity and perspectives for tourism industry, Pogórze Kaczawskie region, SW Poland. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczyńska, K.; Świerkosz, K. Volcanic heritage of Góry and Pogórze Kaczawskie. In Proceedings of the 27th Congress of the European Vegetation Survey, Wrocław, Poland, 23–26 May 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P.; Pijet-Migoń, E. Turbulent history of a basalt quarry and volcanic geosite—A conservation battle finally won? In Proceedings of the XIth International ProGEO Symposium, Charnwood Forest, UK, 9–11 October 2023; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M. Sustainability Management of National Geoparks in the Czech Republic. Stud. Tur. 2018, 9, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P.; Pijet-Migoń, E. Late Palaeozoic volcanism in Central Europe—Geoheritage significance and use in geotourism. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, G.; Závodi, B. The tourism geographical characteristics of wine gastronomy festivals in the Balaton wine region. Pannon. Manag. Rev. 2018, 7, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Linking wine culture and geoheritage—Missing opportunities at European UNESCO World Heritage sites and in UNESCO Global Geoparks? A survey of web-based resources. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Geoproducts—Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Intern. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.; Barata, J.; Gomes, H.; Castro, E. Deploying Smart Community Composting in Estrela UNESCO Global Geopark: A Mobile App Approach. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Information Systems Development (ISD 2021), Valencia, Spain, 8–10 September 2021; p. 12p. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1360&context=isd2014 (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Bohemian Paradise Geopark. Available online: https://www.geoparkceskyraj.cz/en/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Fernandes, G.; de Castro, E.; Gomes, H. Water resources and tourism development in Estrela geopark territory: Meaning and contributions of fluvial beaches to valorise the destination. Europ. Countrys. 2020, 12, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohemian Paradise Smart Guide. Available online: https://www.geoparkceskyraj.cz/cs/geoturistika/smartguide-audio-pruvodce.html (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Maltesics, P. Education in domestic tourism—The Bakony-Balaton Geopark. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawecki, B.; Lorenc, M.W.; Tokarczyk-Dorociak, K. Quarries in the landscape of the county of Strzelin—Native rock materials in the local architecture. Z. Dt. Ges. Geowiss. 2014, 166, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowska, K.; Szadkowski, M.; Tarka, R. Inventory and assessment of the geoheritage of the Sudetic Foreland Geopark (South-Western Poland). Geoheritage 2022, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźma, J.; Kupetz, M. The transboundary Geopark Muskau Arch (Geopark Łuk Mużakowa, Geopark Muskauer Faltenbogen). Przegl. Geol. 2008, 56, 692–698. [Google Scholar]

- Kupetz, M.; Koźma, J. Europäischer and Globaler Geopark Muskauer Faltenbogen/Geopark Łuk Mużakowa—die weltweit am besten untersuchte Grundbruchmorane (“Stauchendmorane”). Veröff. Dt. Geol. Gesell. 2015, 255, 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jamorska, I.; Sobiech, M.; Karasiewicz, T.; Tylmann, K. Geoheritage of postglacial areas in Northern Poland—Prospects for geotourism. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Zabielska, M. In the footsteps of the ice sheet in the area of the planned geopark postglacial land of the Drawa and Dębnica rivers (the Drawskie Lakeland, Poland). Landf. Anal. 2021, 40, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Malicki, P. Bitwa nad Kaczawą i jej znaczenie dla kampanii 1813 roku. In Śląsk w Dobie Kampanii Napoleońskich; Nawrot, D., Ed.; Śląsk: Katowice, Poland, 2014; pp. 64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chylińska, D. Krajobraz pola bitwy jako reprezentacja pamięci miejsca i pamięci kolektywnej narodu. Zarys Problematyki. Zesz. Nauk. Tur. Rekreac. WSTiJO 2016, 17, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zeremski, T.; Tomić, N.; Milić, S.; Vasin, J.; Schaetzl, R.J.; Milić, D.; Gavrilov, M.B.; Živanov, M.; Ninkov, J.; Marković, S.B. Saline soils: A potentially significant geoheritage of the Vojvodina Region, Northern Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masseroli, A.; Bollati, I.M.; Fracasetti, L.; Trombino, L. Soil trail as a tool to promote cultural and geoheritage: The case study of Mount Cusna geosite (Northern Italian Apennines). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquaré Mariotto, F.; Bonali, F.L. Virtual Geosites as Innovative Tools for Geoheritage Popularization: A Case Study from Eastern Iceland. Geosciences 2021, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquaré Mariotto, F.; Antoniou, V.; Drymoni, K.; Bonali, F.L.; Nomikou, P.; Fallati, L.; Karatzaferis, O.; Vlasopoulos, O. Virtual Geosite Communication through a WebGIS Platform: A Case Study from Santorini Island (Greece). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Graña, A.; González-Delgado, J.A.; Nieto, C.; Villalba, V.; Cabero, T. Geodiversity and Geoheritage to Promote Geotourism Using Augmented Reality and 3D Virtual Flights in the Arosa Estuary (NW Spain). Land 2023, 12, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T.A. Awheel along Europe’s rivers: Geoarchaeological trails for cycling geotourists. Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugeri, F.R.; Farabollini, P. Discovering the landscape by cycling: A geo-touristic experience through Italian Badlands. Geosciences 2018, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).