What Role Does Sustainable Behavior and Environmental Awareness from Civil Society Play in the Planet’s Sustainable Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

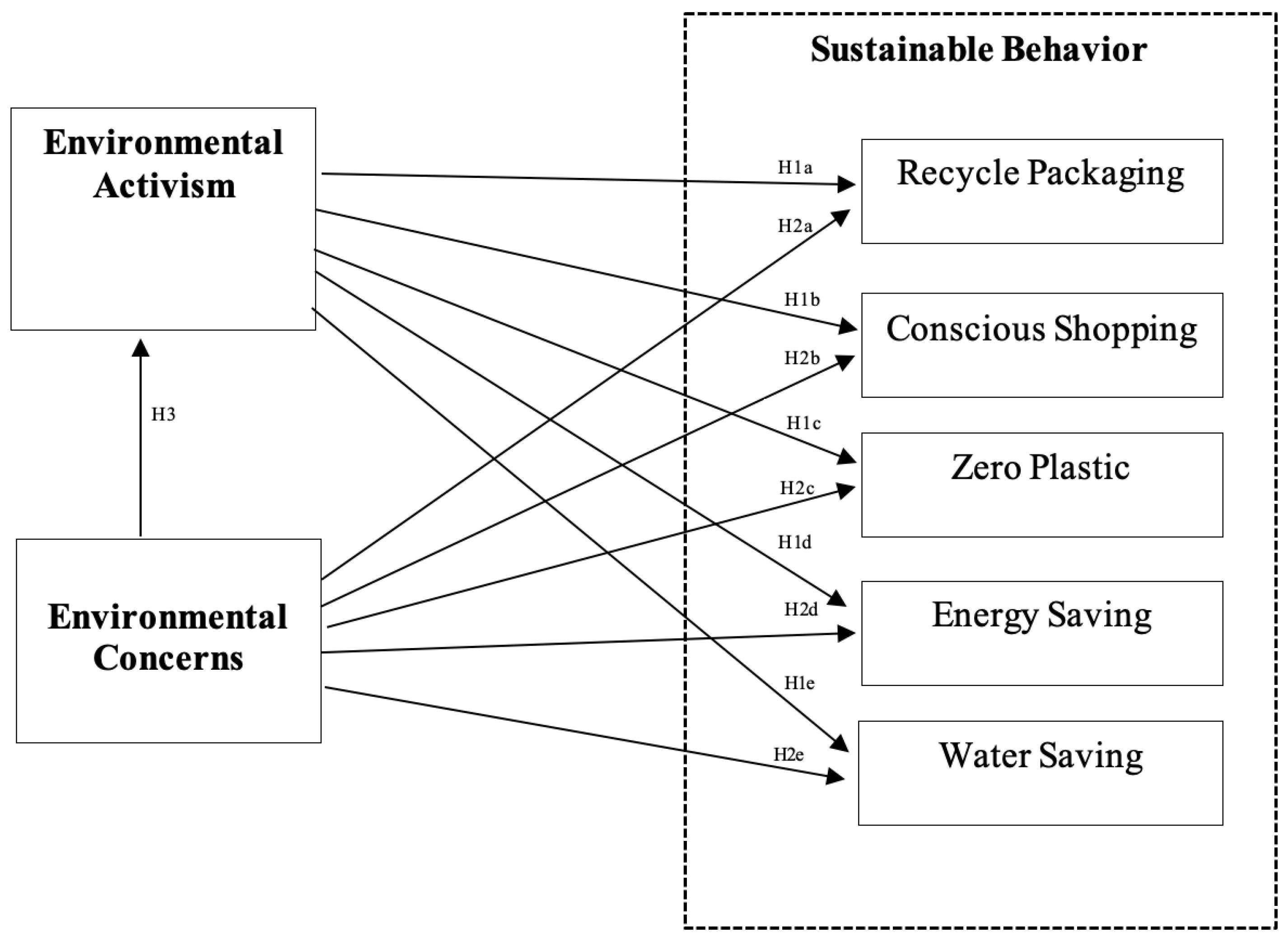

2. Literature Review and Structural Model

2.1. Sustainable Behaviours

2.2. Pro-Environmental Collective Actions/Environmental Activism

2.3. Environmental Concerns

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Measurement

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

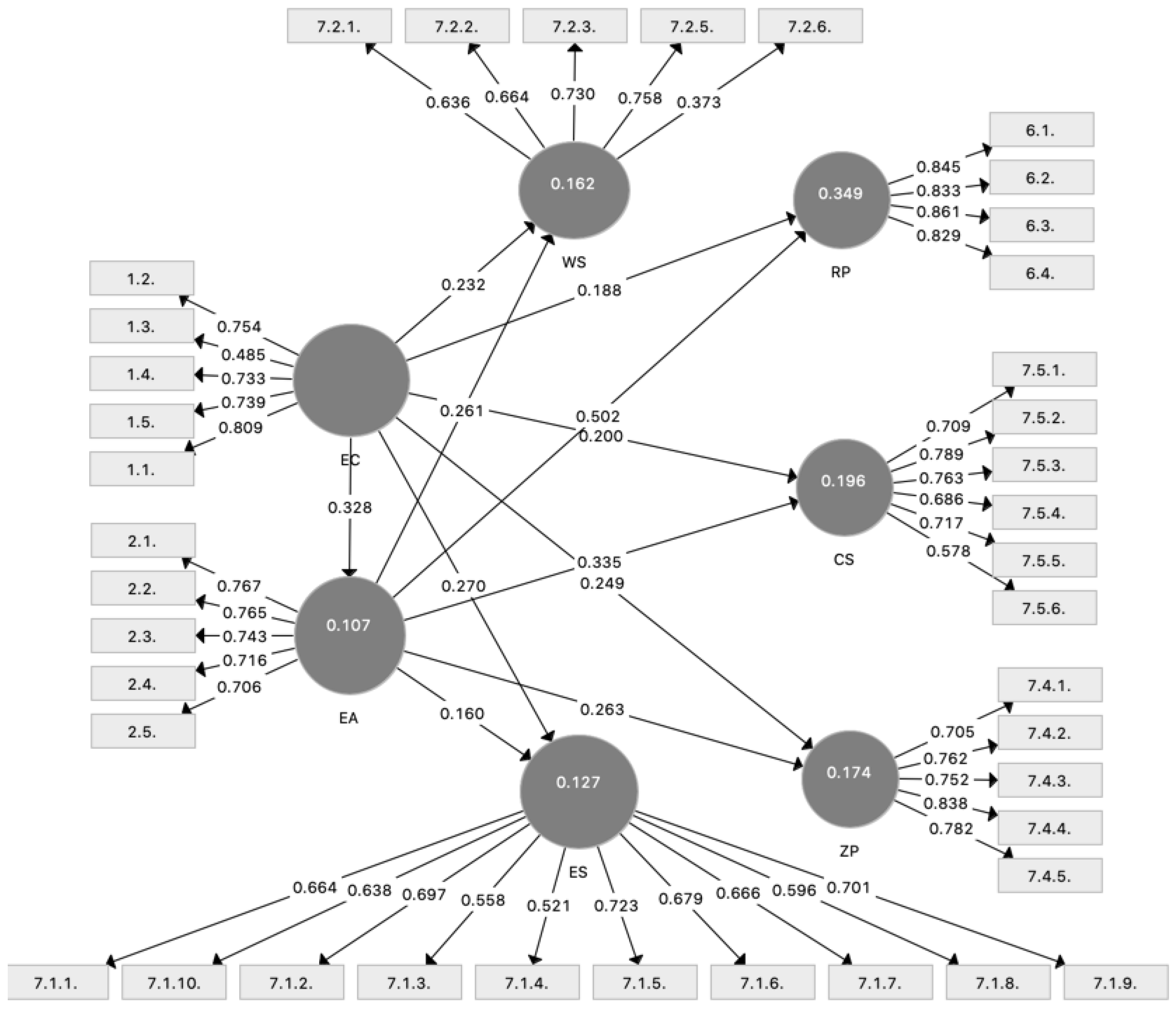

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mean (M) | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Sustainable Behaviours | ||

| A1. Sustainable consumption decisions | ||

| Recyclable Packaging (RP) | 2.98 | 0.802 |

| #1. When I have to choose a personal care product (e.g., shampoo, shower gel), I buy one with packaging made from recycled material. | 2.95 | 0.768 |

| #2. When I buy bakery products (e.g., bread, sandwiches) I choose those that have a simple packaging design (e.g., monomaterial, which can be divided into recyclable materials) | 3.10 | 0.77 |

| #3. When purchasing a product, I check the recycling information on the packaging to ensure that it is easily recyclable. | 2.80 | 0.873 |

| #4. When I buy food products, I look for those with packaging that can also be used for other purposes (eg glass packaging that can be reused as a cup). | 3.06 | 0.795 |

| Conscious Shopping (CS) * | 2.83 | 0.712 |

| #5. I buy organic products | 2.62 | 0.661 |

| #6. I buy recycled products | 2.76 | 0.611 |

| #7. I choose products keeping in mind the CO2 emission (carbon footprint) | 2.4 | 0.771 |

| #8. I try to fix things before buying replacement parts | 3.09 | 0.765 |

| #9. I use recharge products | 3.04 | 0.711 |

| #10. I don’t buy unnecessary products | 3.06 | 0.753 |

| Zero Plastic (ZP) * | 3.11 | 0.760 |

| #11. I use my own bottle or glass of water | 3.33 | 0.764 |

| #12. I use a container instead of a plastic bag | 2.89 | 0.843 |

| #13. I use my own bag/purse to go shopping | 3.38 | 0.714 |

| #14. Reduce the use of disposable products | 3.04 | 0.722 |

| #15. I don’t buy overpackaged products | 2.92 | 0.773 |

| A2. Sustainable household practices * | ||

| Energy Saving (ES) | 3.19 | 0.785 |

| #16. Avoid overloading the fridge | 2.91 | 0.803 |

| #17. I reduce the opening and closing of the refrigerator door | 3.19 | 0.776 |

| #18. I use stairs instead of elevators | 2.84 | 0.834 |

| #19. Adjust the air conditioning temperature | 3.06 | 0.956 |

| #20. I turn off the lights in empty rooms | 3.65 | 0.619 |

| #21. Turn off devices not in use | 3.46 | 0.716 |

| #22. I turn off the TV when people aren’t watching | 3.49 | 0.721 |

| #23. I set a lower shower temperature | 2.63 | 0.929 |

| #24. Buy energy efficient appliances | 3.24 | 0.765 |

| #25. I use LED lamp instead of fluorescent lamps | 3.46 | 0.728 |

| Water Saving (WS) | 2.47 | 0.712 |

| #26. I use the toothbrush cup | 2.31 | 1.128 |

| #27. I turn off the water when washing my face or brushing my teeth | 3.42 | 0.762 |

| #28. I take short showers | 3.17 | 0.707 |

| #29. I reduce the frequency of washing clothes | 2.95 | 0.775 |

| #30. Use dishwasher | 2.96 | 0.897 |

| B. Environmental Awareness ** | ||

| B1. Environmental Concerns | 4.62 | 0.657 |

| #31. I am concerned about the consumption of natural resources and the consequences for future generations. | 4.67 | 0.634 |

| #32. Waste of resources is a serious problem. | 4.86 | 0.448 |

| #33. In our country we are not doing enough to encourage waste recycling. | 4.32 | 0.884 |

| #34. Protecting the natural environment is one of the most important issues facing the world. | 4.62 | 0.679 |

| #35. Increasing the shelf life of the products we use must be a priority in order to preserve the balance of nature. | 4.65 | 0.638 |

| B2. Environmental Activism | 2.92 | 1.207 |

| #36. I talk to other people about environmental issues. | 3.61 | 0.969 |

| #37. I work with others to solve environmental problems or issues. | 2.75 | 1.154 |

| #38. I participate as a volunteer in initiatives aimed at improving the natural environment of my community. | 2.35 | 1.24 |

| #39. I visit natural sites where I live to support initiatives to protect natural heritage. | 3.08 | 1.319 |

| #40. I make donations and/or sign petitions to support environmental protection. | 2.80 | 1.354 |

| Gender | Age | Education | Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | p-Value | Beta | p-Value | Beta | p-Value | Beta | p-Value | |

| RecyclablePackaging (RP) | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.281 | 0.000 | --- | >0.05 | --- | >0.05 |

| Conscious Shopping (CS) | 0.100 | 0.015 | 0.178 | 0.000 | --- | >0.05 | --- | >0.05 |

| Zero Plastic (ZP) | 0.260 | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.003 | --- | >0.05 | --- | >0.05 |

| Energy Saving (ES) | 0.141 | 0.000 | 0.262 | 0.000 | --- | >0.05 | --- | >0.05 |

| Water Saving (WS) | 0.173 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.000 | --- | 0.018 | --- | >0.05 |

| Environmental Concerns (EC) | 0.148 | 0.000 | 0.144 | 0.000 | --- | >0.05 | --- | >0.05 |

| Environmental Activism (EA) | 0.180 | 0.000 | 0.239 | 0.000 | --- | >0.05 | --- | >0.05 |

| RP | CS | ZP | ES | WS | EC | EA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recyclable Packaging (RP) | |||||||

| #1. When I have to choose a personal care product (e.g., shampoo, shower gel), I buy one with packaging made from recycled material. | 0.845 | ||||||

| #2. When I buy bakery products (e.g., bread, sandwiches) I choose those that have a simple packaging design (e.g., monomaterial, which can be divided into recyclable materials) | 0.833 | ||||||

| #3. When purchasing a product, I check the recycling information on the packaging to ensure that it is easily recyclable. | 0.861 | ||||||

| #4. When I buy food products, I look for those with packaging that can also be used for other purposes (eg glass packaging that can be reused as a cup). | 0.829 | ||||||

| Conscious Shopping (CS) | |||||||

| #5. I buy organic products | 0.709 | ||||||

| #6. I buy recycled products | 0.789 | ||||||

| #7. I choose products keeping in mind the CO2 emission (carbon footprint) | 0.763 | ||||||

| #8. I try to fix things before buying replacement parts | 0.686 | ||||||

| #9. I use recharge products | 0.717 | ||||||

| #10. I don’t buy unnecessary products | 0.578 | ||||||

| Zero Plastic (ZP) | |||||||

| #11. I use my own bottle or glass of water | 0.705 | ||||||

| #12. I use a container instead of a plastic bag | 0.762 | ||||||

| #13. I use my own bag/purse to go shopping | 0.752 | ||||||

| #14. Reduce the use of disposable products | 0.838 | ||||||

| #15. I don’t buy overpackaged products | 0.782 | ||||||

| Energy Saving (ES) | |||||||

| #16. Avoid overloading the fridge | 0.664 | ||||||

| #17. I reduce the opening and closing of the refrigerator door | 0.638 | ||||||

| #18. I use stairs instead of elevators | 0.697 | ||||||

| #19. Adjust the air conditioning temperature | 0.558 | ||||||

| #20. I turn off the lights in empty rooms | 0.521 | ||||||

| #21. Turn off devices not in use | 0.723 | ||||||

| #22. I turn off the TV when people aren’t watching | 0.679 | ||||||

| #23. I set a lower shower temperature | 0.666 | ||||||

| #24. Buy energy efficient appliances | 0.596 | ||||||

| #25. I use LED lamp instead of fluorescent lamps | 0.701 | ||||||

| Water Saving (WS) | |||||||

| #26. I use the toothbrush cup | 0.736 | ||||||

| #27. I turn off the water when washing my face or brushing my teeth | 0.764 | ||||||

| #28. I take short showers | 0.730 | ||||||

| #29. I reduce the frequency of washing clothes | 0.758 | ||||||

| #30. Use dishwasher | 0.773 | ||||||

| Environmental Concerns (EC) | |||||||

| #31. I am concerned about the consumption of natural resources and the consequences for future generations. | 0.754 | ||||||

| #32. Waste of resources is a serious problem. | 0.785 | ||||||

| #33. In our country we are not doing enough to encourage waste recycling. | 0.733 | ||||||

| #34. Protecting the natural environment is one of the most important issues facing the world. | 0.739 | ||||||

| #35. Increasing the shelf life of the products we use must be a priority in order to preserve the balance of nature. | 0.809 | ||||||

| Environmental Activism (EA) | |||||||

| #36. I talk to other people about environmental issues. | 0.767 | ||||||

| #37. I work with others to solve environmental problems or issues. | 0.765 | ||||||

| #38. I participate as a volunteer in initiatives aimed at improving the natural environment of my community. | 0.743 | ||||||

| #39. I visit natural sites where I live to support initiatives to protect natural heritage. | 0.716 | ||||||

| #40. I make donations and/or sign petitions to support environmental protection. | 0.706 |

References

- Yamaguchi, N.U.; Bernardino, E.G.; Ferreira, M.E.C.; de Lima, B.P.; Pascotini, M.R.; Yamaguchi, M.U. Sustainable development goals: A bibliometric analysis of literature reviews. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 5502–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- East, M. The transition from sustainable to regenerative development. Ecocycles 2020, 6, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental psychology matters. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 541–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, T.; Fujii, S.; Gärling, A.; Jakobsson, C. Moderating effects of social value orientation on determinants of proenvironmental behavior intention. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, G.L.; Richardson, S.J.; Harré, N.; Hodges, D.P.; Lyver, P.O.; Maseyk, F.J.; Taylor, R.M.; Todd, J.H.; Tylianakis, J.M.; Yletyinen, J.; et al. Evaluating the Role of Social Norms in Fostering Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Psychology and the science of human-environment interactions. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Shivarajan, S.; Blau, G. Enacting ecological sustainability in the MNC: A test of an adapted value-belief-norm framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iovino, R.; Iraldo, F. The circular economy and consumer behaviour: The mediating role of information seeking in buying circular packaging. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3435–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, T.; Ilieva, I.; Angelova, M. Exploring Factors Affecting Sustainable Consumption Behaviour. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets–Portugal. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/wise/measuring-distance-to-the-SDG-targets-country-profile-Portugal.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Pirvu, R.; Bădîrcea, R.; Patrichi, I.C. Achievement of the sustainable development goals (sdg) in portugal and forecast of key indicators until 2030. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 28, 1649–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinova, E. Sustainable consumer behavior: Literature overview. Econ. Altern. 2016, 2, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Sustainable behavior and quality of life. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R. Sustainable consumer behavior. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; Volume 21, pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Trudel, R. The effect of recycling versus trashing on consumption: Theory and experimental evidence. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Antecedents to green buying behaviour: A study on consumers in an emerging economy. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Xiaoling, G.; Ali, A.; Sherwani, M.; Muneeb, F.M. Customer motivations for sustainable consumption: Investigating the drivers of purchase behavior for a green-luxury car. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horen, F.; Van der Wal, A.; Grinstein, A. Green, greener, greenest: Can competition increase sustainable behavior? J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, P.; Barker, J.L. Greener than thou: People who protect the environment are more cooperative, compete to be environmental, and benefit from reputation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, G.E.; Lamberton, C.; Reczek, R.W.; Norton, M.I. Social recycling transforms unwanted goods into happiness. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, S.Z.; DeKay, M.L.; Davidson, C.I.; Bruine de Bruin, W. Public perceptions of energy consumption and savings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16054–16059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, Z.; Korhonen, V.; Koelsch Sand, C. Consumer considerations for the implementation of sustainable packaging: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B.; Argo, J.J. The motivating role of dissociative out-groups in encouraging positive consumer behaviors. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, L.H.L.; Pinto, D.C.; Cruz-Jesus, F. Circular economy engagement: Altruism, status, and cultural orientation as drivers for sustainable consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.C. The next generation of collective action research. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Iyer, A. Introduction to the social and psychological dynamics of collective action. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Rees, J.; Seebauer, S. Collective climate action: Determinants of participation intention in community-based pro-environmental initiatives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Pauls, I.L.; Cohen-Chen, S. Is hope good for motivating collective action in the context of climate change? Differentiating hope’s emotion-and problem-focused coping functions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.H.; Bamberg, S. Climate protection needs societal change: Determinants of intention to participate in collective climate action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M. Synthesizing individualistic and collectivistic perspectives on environmental and collective action through a relational perspective. Theory Psychol. 2014, 24, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Postmes, T.; Spears, R. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Postmes, T.; Spears, R. On conviction’s collective consequences: Integrating moral conviction with the social identity model of collective action. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 51, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsche, I.; Barth, M.; Jugert, P.; Masson, T.; Reese, G. A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 2018, 125, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dono, J.; Webb, J.; Richardson, B. The relationship between environmental activism, pro-environmental behaviour and social identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M.J. A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Mackay, C.M.; Droogendyk, L.M.; Payne, D. What predicts environmental activism? The roles of identification with nature and politicized environmental identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A.M.; Otten, C.D.; BurnSilver, S.; Neuberg, S.L.; Anderies, J.M. Integrating institutional approaches and decision science to address climate change: A multi-level collective action research agenda. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 52, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harring, N.; Jagers, S.C.; Nilsson, F. Recycling as a large-scale collective action dilemma: A cross-country study on trust and reported recycling behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F.; Liu, Y. Pro-environmental behavior in an aging world: Evidence from 31 countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mase, A.S.; Gramig, B.M.; Prokopy, L.S. Climate change beliefs, risk perceptions, and adaptation behavior among Midwestern US crop farmers. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 15, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.T.; Niu, H.J. Green consumption: Environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, social norms, and purchasing behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, N. Environmental concern and purchase intention of electric vehicles in the eastern part of China. Arch. Bus. Res. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiaslis, A.; Krontalis, A.K. Green consumption behavior antecedents: Environmental concern, knowledge, and beliefs. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.D.; Acharya, N. Causality analysis of media influence on environmental attitude, intention and behaviors leading to green purchasing. J. Clean. 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B. When do (and don’t) normative appeals influence sustainable consumer behaviors? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekria, N.; Daud, S. Environmental concern and recycling behaviour. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R. The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery-Gomm, S.; Walker, T.R.; Mallory, M.L.; Provencher, J.F. There is nothing convenient about plastic pollution. Rejoinder to Stafford and Jones “Viewpoint–Ocean plastic pollution: A convenient but distracting truth?”. Mar. Policy 2019, 106, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arı, E.; Yılmaz, V. Consumer attitudes on the use of plastic and cloth bags. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, G.; Pires, A.; Portela, G.; Fonseca, M. Factors affecting consumers’ choices concerning sustainable packaging during product purchase and recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 103, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelsen, M.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ response to environmentally-friendly food packaging-A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.; Sharma, B.; Kerr, D.; Smith, T. The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7684–7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, I.; Hameed, I. An empirical study of consumers intention to purchase energy efficient appliances. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, A.; Kallbekken, S. The impact of consumer attitudes towards energy efficiency on car choice: Survey results from Norway. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W. Consumer behaviour and environmental sustainability. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Osborne, D.; Yogeeswaran, K.; Sibley, C.G. The role of national identity in collective pro-environmental action. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.A. Social identity and environmental concern: The importance of contextual effects. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 828–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.; Bamberg, S.; Rees, J.; Rollin, P. Social identity as a key concept for connecting transformative societal change with individual environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.P.; Lewis Jr, N.A.; Ellsworth, P.C. Believing in climate change, but not behaving sustainably: Evidence from a one-year longitudinal study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 56, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, S.; Lazanyuk, I.; Revinova, S.; Gomonov, K. Barriers of consumer behavior for the development of the circular economy: Empirical evidence from Russia. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P.; Chan, H.W. Environmental concern has a weaker association with pro-environmental behavior in some societies than others: A cross-cultural psychology perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, J.G. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, R. Factors Influencing Plastic Bag Avoidance Behaviour Among the Indian Consumers. Vision 2022, 09722629221099601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Liu, R.L. Future-oriented women will pay to reduce global warming: Mediation via political orientation, environmental values, and belief in global warming. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, J.; Pántya, J.; Medvés, D.; Hidegkuti, I.; Heim, O.; Bursavich, J.B. Justifying environmentally significant behavior choices: An American-Hungarian cross-cultural comparison. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Pereira, M.C.; Cruz, L.; Simões, P.; Barata, E. Affect and the adoption of pro-environmental behaviour: A structural model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodhart, B.; Swim, J.K. Sustainability and consumption: What’s gender got to do with it? J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: Do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A.; Reser, J.P. The role of climate change risk perception, response efficacy, and psychological adaptation in pro-environmental behavior: A two nation study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.; Xu, L. Relationships between personal values, micro-contextual factors and residents’ pro-environmental behaviors: An explorative study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsimanis, G.; Getter, K.; Behe, B.; Harte, J.; Almenar, E. Influences of packaging attributes on consumer purchase decisions for fresh produce. Appetite 2012, 59, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruk, A.I.; Iwanicka, A. The effect of age, gender and level of education on the consumer’s expectations towards dairy product packaging. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Mo, T.; Wang, Y. Better self and better us: Exploring the individual and collective motivations for China’s Generation Z consumers to reduce plastic pollution. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuła, A.; Raczkowska, M.; Utzig, M. Pro-environmental behaviour in the European Union countries. Energies 2021, 14, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, N.; Giusti, M.; Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S. Pro-environmental habits: An underexplored research agenda in sustainability science. Ambio 2022, 51, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cα | CR | AVE | RP | CS | ZP | ES | WS | EA | EC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recyclable Packaging (RP) | 0.863 | 0.907 | 0.709 | 0.842 | ||||||

| Conscious shopping (CS) | 0.807 | 0.858 | 0.504 | 0.525 | 0.710 | |||||

| Zero Plastic (ZP) | 0.827 | 0.878 | 0.592 | 0.446 | 0.638 | 0.769 | ||||

| Energy Saving (ES) | 0.844 | 0.877 | 0.519 | 0.380 | 0.552 | 0.562 | 0.720 | |||

| Water Saving (WS) | 0.752 | 0.775 | 0.519 | 0.381 | 0.525 | 0.544 | 0.605 | 0.720 | ||

| Environmemtal Concerns (EC) | 0.753 | 0.834 | 0.508 | 0.353 | 0.310 | 0.335 | 0.552 | 0.317 | 0.713 | |

| Environmental Activism (EA) | 0.795 | 0.858 | 0.547 | 0.564 | 0.401 | 0.344 | 0.248 | 0.337 | 0.328 | 0.740 |

| Effects on Endogenous Variable | Path (β) | t Value (Bootstrap) | Confidence Interval | Hypothesis Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||

| H1a: EA → RP | 0.502 | 17.784 | 0.444 | 0.556 | Yes |

| H1b: EA → CS | 0.335 | 7.935 | 0.256 | 0.416 | Yes |

| H1c: EA → ZP | 0.263 | 6.301 | 0.181 | 0.346 | Yes |

| H1d: EA → ES | 0.160 | 3.318 | 0.067 | 0.260 | Yes |

| H1e: EA → WS | 0.261 | 6.501 | 0.181 | 0.339 | Yes |

| H2a: EC → RP | 0.188 | 4.948 | 0.101 | 0.249 | Yes |

| H2b: EC → CS | 0.200 | 4.293 | 0.107 | 0.287 | Yes |

| H2c: EC → ZP | 0.249 | 5.734 | 0.168 | 0.332 | Yes |

| H2d: EC → ES | 0.270 | 5.149 | 0.174 | 0.371 | Yes |

| H2e: EC → WS | 0.232 | 5.021 | 0.140 | 0.319 | Yes |

| H3: EC → EA | 0.328 | 10.366 | 0.271 | 0.387 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinho, M.; Gomes, S. What Role Does Sustainable Behavior and Environmental Awareness from Civil Society Play in the Planet’s Sustainable Transition. Resources 2023, 12, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources12030042

Pinho M, Gomes S. What Role Does Sustainable Behavior and Environmental Awareness from Civil Society Play in the Planet’s Sustainable Transition. Resources. 2023; 12(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources12030042

Chicago/Turabian StylePinho, Micaela, and Sofia Gomes. 2023. "What Role Does Sustainable Behavior and Environmental Awareness from Civil Society Play in the Planet’s Sustainable Transition" Resources 12, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources12030042

APA StylePinho, M., & Gomes, S. (2023). What Role Does Sustainable Behavior and Environmental Awareness from Civil Society Play in the Planet’s Sustainable Transition. Resources, 12(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources12030042