Abstract

The functions of community gardens (CGs) are determined by the preferences of their users and external factors such as government restrictions or the situation of the food market. Recent food prices increases and COVID-19 restrictions have shown the importance of CGs as a place for both food self-provisioning (FSP) and relaxation. These have influenced how much the benefits provided by CGs in the form of ecosystem services (ES) are appreciated. This study aims to demonstrate how ES provided by the CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ in Czechia are affected in times of crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic and to increased food prices, which trigger a demand for greater FSP. The results indicate that the importance of social interaction and educational ES decreased significantly in the COVID-19 scenario. On the contrary, the role of CGs as places for recreation increased. In the FSP scenario, the provisioning ES increased at the expense of recreational ES. The results of the economic assessment further show that the most important monetarily valued ES provided by CGs are cultural ES, followed by provisioning ES. This study demonstrates both the multifunctionality and adaptability of CGs to the current social crises and dynamic urban conditions.

1. Introduction

Urban gardening has undergone significant changes over time. As noted in [1], initially, it primarily served a production function. With population growth and urbanisation, the first gardens began to appear, where immigrants from villages grew their crops. This was partly out of habit but also out of the need to save on food expenses. With the increasing availability of food in countries of the Global North, urban gardening, initially motivated by its productive function, gradually became a leisure activity (in the form of an opportunity to spend leisure time, joy of self-fulfilment and to create a healthier environment for staying outside) in most European countries. Purely ornamental plants, leisure equipment, etc., began to appear in gardens. The same evolution can be observed with community gardens (CGs) [2,3], which are among examples of urban gardening and which are the focus of this paper. CGs can be defined as mostly vacant plots of land used for growing crops (mainly vegetables, fruits and herbs) by people from different families, typically urban dwellers, where individual beds are not fenced and some are managed together by the community. CGs, thus, contribute not only to crop production but also to community building, social interaction and recreation [4,5,6].

Urban gardening and CGs have begun to grow in importance in recent decades, also in light of the trend towards urban densification and increasing competition for land use and green spaces. In many countries, a trend of increasing numbers of CGs can be observed in recent years, and this is not only the case in larger cities [7,8]. CGs, thus, form important elements of green spaces that provide a wide range of benefits for individuals and society in the form of ecosystem services (ES) [2,9]. These are the benefits that people obtain from ecosystems and are divided into provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting ES [10,11]. In the context of provisioning ES, CGs contribute to food self-provisioning (FSP), providing high-quality and fresh crops, mainly fruits, vegetables and different types of herbs. The provisioning ES also include biomass production [12]. Gardens also usually provide space for composting household kitchen waste [13]. Under the so-called regulating ES, CGs can be classified as climate change adaptation measures [14]. CGs contribute to temperature regulation, storm water infiltration and runoff reduction, air-quality improvement and microclimate regulation but also to biodiversity protection and habitat creation [14,15,16,17,18]. Community gardening can also regulate health and improve personal well-being [6,19,20]. Through increased physical activity and horticultural therapy, CGs can reduce stress and negativity [21]. Opportunities for social interaction, community building and the associated increase in community resilience are classified as cultural ES, as well as having aesthetic and educational functions [2,6,8].

The aim of this study was to demonstrate how the ES provided by CGs are affected in times of differently induced social crises. Specifically, the baseline state (‘No crisis’ scenario) was compared to two current crises: one associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (‘COVID-19’ scenario) and the other associated with the rise in food prices that triggers a move towards greater FSP (‘Food self-provisioning’ scenario). We applied these three scenarios to the existing CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ in Ústí nad Labem, Czechia, including expression of the change in the provision of ES in monetary units.

The importance of urban gardening in times of crisis has been investigated in many countries. From the perspective of FSP, the importance of gardens increased in the 20th and 21st centuries during the world wars and economic crises [1,3,22]. Society’s demand for greater FSP is also increasing in Czechia, where food-growing households are able to cover one-third of their fruit and vegetable consumption from their gardens (including from gardens at family houses and holiday homes, allotment gardens and CGs) [23,24]. Several efforts to increase FSP in reaction to negative social consequences have also been mapped in other European countries over the last two decades. Most of them are connected with allotment gardens. In France, allotment gardens have emerged close to the residences of socially vulnerable people (e.g., near social centres) in a collaboration between the local government and a housing agency [25]. In Portugal, a network of urban allotment gardens was established for unemployed and low-income people with an interest in crop production in order to increase their capacity for FSP [26]. A large number of these gardens are still operating today, while, at the same time, a number of new jobs linked to this area were created during the economic crisis [22]. Similar examples of food security for low-income groups through urban gardening can be found in other countries such as Spain [27]. However, the increasing role of growing crops may not only be the result of a crisis and a desire to save household expenses but is associated with efforts to produce food sustainably, to know the origin of one’s food or to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In Sweden, urban gardening has historically contributed not only to residents’ FSP in times of crisis but has also served as urban green spaces and collective memory among residents about how to grow food [3]. Although growing crops is an integral part of community gardening [28,29], the emphasis on crop production as a means of supporting livelihoods varies among CGs (and urban gardens in general), reflecting gardeners’ preferences [7,30,31] and different circumstances such as a specific market situation [24,32].

More recent research suggests that various forms of urban gardening and their importance have also been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [33,34]. In countries of the Global North, urban gardening provided food for selected households at times when their incomes declined. For part of the population affected by the decline in income, urban gardening was important in providing healthy food [27]. A partial motive was also to gain control over production capacities and to support local chains [33]. In Germany, the benefits of urban gardening during the COVID-19 pandemic for mental well-being and life satisfaction were addressed in [35]. Their research showed that garden owners had higher ratings of both mental well-being and life satisfaction during the pandemic. This was likely due to garden owners spending more time outdoors than people without gardens. In [36], the importance of CGs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Edmonton, Canada, was examined. The authors specifically looked at the functioning of CGs during the period when the government measures were in place. They confirmed that coordinators had to adjust their working style so that CG members were (physically) separated but socially connected. Members confirmed that the community helped them cope with the harder times, but they were lacking group activities. Some, therefore, started to form communities in a digital space. In European countries, the start of the CG season was postponed in some cases. However, after adjusting the operating conditions, gardeners continued to grow there while paying respect to physical distancing [37].

The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 describes the CG that serves as the case study, defines three scenarios and presents the methods of data collection and analysis. The results of the benefit valuation provided by the CG in the three selected scenarios are provided in Section 3 and discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with a brief summary of the main findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ Case Study

The CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ serves as a case study to demonstrate how the ES provided by CGs are affected in times of differently induced social crises. The CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ is located in the city of Ústí nad Labem, Czechia. Ústí nad Labem lies in the northern part of Czechia, with a population of 93 thousand. It is a traditional industrial centre close to the German border and is currently characterised by above-average unemployment rates [38]. The location of the garden in Czechia is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

‘Žížala na Terase’ location in Czechia.

The CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ is located between prefabricated blocks of flats in a densely populated area (see Figure 2). Around 20,000 inhabitants live in this part of the city [39]. The CG was established in 2017 as a bottom-up initiative of local community members on an unused and neglected municipal property that belongs to the area of a public primary school. Of the total CG area of 1300 m2, approximately 200 m2 is made up of growing plots, the rest is designed for community activities and consists of fruit and ornamental trees, shrubs, herbs, open grass areas, a garden house and a fireplace. The CG is used to grow fruit, vegetables and herbs, but equally important is its cultural and educational function in connection with the local school and the surrounding area. The CG is also open to the public, especially for themed events (e.g., yoga lessons).

Figure 2.

‘Žížala na Terase’ CG in Ústí nad Labem, Czechia.

The CG is mainly attended by people from the nearby prefabricated blocks of flats. Both younger and older gardeners are represented among the members. A significant part of the members are families with one or two children, who spend their free time here not only by growing crops but also by playing. The CG is open to new members who want to get involved in growing crops in the garden. Anyone interested in membership can submit an application form, which must then be approved by the existing members. Once the membership fee (EUR 20 annually) is paid, the new member is given a plot of land. Each member has the right to garden on their plot and participate in events organised by the community. Membership also includes involvement in the maintenance of common areas of the CG at voluntary work events announced throughout the year. Those who do not participate pay a higher membership fee. Each member has a key to the garden and can visit it freely. They can also invite family and friends to the garden occasionally, e.g., for birthday parties.

2.2. Three Scenarios Applied to Evaluate Changes in ES Provided by CG

Three scenarios were applied to the CG ‘Žížala na Terase’ case study, as described in Section 2.1, to evaluate the changes in ES provision. The first scenario, ‘No crisis’, is based on the state of the garden in 2019, when the CG had a relatively stable number of 19 members actively involved in community gardening. A 200 m2 area of the CG was dedicated to growing crops. The CG was regularly visited by 60 pupils from a nearby primary school and four educational seminars and workshops per year were also held in the CG.

The second scenario, ‘COVID-19’, is based on the years 2020 and 2021, when there was a pandemic associated with COVID-19 in Czechia. Various restrictions were imposed on public spaces, such as limits on gatherings. As a result, all public events normally organised in the CG were cancelled, as well as educational activities involving pupils, seminars and workshops.

The third scenario, ‘Food self-provisioning’, is associated with the rise in food prices, which triggered a move towards greater FSP. In Czechia, consumer prices rose by 17.5% (year-on-year) in January 2023 and the inflation rate for food was 21.6% (year-on-year) in April 2023 [40]. However, food price growth is now an issue in most European countries. For example, in the EU, food price inflation reached 17.5% in March 2023 [41]. As a result of increased food prices, this valuated scenario assumes that people are increasingly interested in growing more. This ‘Food self-provisioning’ scenario also assumes that educational events for pupils and adults take place in the garden again, as in the ‘No crisis’ scenario, i.e., before the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

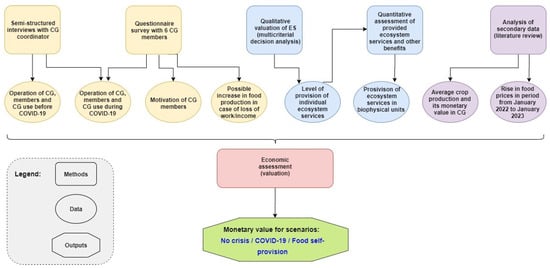

Methodologically, this article is based on a combination of several methods that have been successfully applied in research projects dealing with CGs as an adaptation measure to climate change, the motivation of members and coordinators of CGs, crop production of CGs and potential of CGs in times of crisis to eliminate the negative impacts on the population. The data collection started before COVID-19, continued during and after the COVID-19 pandemic and gradually reflected current issues (pandemic restrictions, price increases and related changes in people’s behaviour). An overview of the mixed methods is shown in Figure 3. The information was collected using two semi-structured interviews with the CG coordinator and using a questionnaire survey (QS) among members of the case study CG. Based on the interviews and field surveys, the level of provision of individual ES was identified and assessed qualitatively. Secondary data based on a literature review were collected, for instance, on the average production in Czech CGs and market crop prices, and then used to transfer values to express specific ES in monetary units. The different methods and their implementation are further presented in the following Sections.

Figure 3.

Overview of methods and data used.

2.3.1. Semi-Structured Interviews with CG Coordinator

Two semi-structured interviews with the CG coordinator were organised. The first interview was organised in the garden in April 2019. The aim was to collect data about the CG, its members and garden use. These data serve as input data for selected scenarios, mostly for the ‘No crisis’ scenario, as they are related to the CG use before the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise in inflation that can be currently observed.

The second semi-structured interview with the CG coordinator took place in the garden in July 2021, during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the coordinator’s consent, the interview was recorded and then transcribed for better data processing. The second interview was structured into several topics focused on (i) the impact of government restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic on CG members and use of CG; (ii) the change in CG members’ attendance; and (iii) the overall size of the membership base. Information on members and changes in attendance are presented as the basis for the evaluation of the ‘COVID-19’ scenario described in Section 2.2.

2.3.2. Questionnaire Survey among CG Members

Data from the semi-structured interviews with the CG coordinator are combined and supplemented with data from a QS among long-time members of the CG. The QS aimed to identify the underlying motivations of members for their involvement in the CG, the impact of COVID-19 on their behaviour and the motivation related to FSP. The questionnaire was structured into six main parts: (i) cultivation experience and motivations leading to membership of the CG; (ii) time spent in the CG and crops grown; (iii) impact of the CG on the surrounding area and on the CG member’s quality of life; (iv) interest in increasing crop production in relation to strengthening FSP due to loss of employment, decline in household incomes or increase in food prices in relation to various types of crises; (v) identification of the CG attended; and (vi) the respondent’s sociodemographic data. The questionnaire operated with both closed-ended multiple-choice and open-ended questions. The questionnaire was pilot-tested on a small sample in preparation, with an emphasis on the clarity of the questions. The data collection took place from October to December 2021 in different CGs across Czechia. Because of the worsening COVID-19 pandemic conditions, an online form for data collection was chosen.

From the total sample of 157 responses from different CGs, a total of six responses were collected from the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG, making up approximately one-fifth of all the CG members at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, and used for further analysis.

2.3.3. Qualitative Valuation of ES Provided by CG in Different Scenarios

In each of the three scenarios evaluated, the level of ES provided changes as a result of changes in CG usage, including changes in the number of its members, frequency of visits, intensity of crop production or organisation of public events (reflecting the information provided to us by the CG coordinator and members in the form of interviews and a QS). A methodological approach based on [42] was applied to qualitatively evaluate the impact of individual scenarios on ES. This methodology is primarily used in Czechia to evaluate urban adaptation measures to climate change, such as CGs, trees, wetlands or green roofs. The specific evaluation procedure is based on the use of the multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) method. The level of the provision of ES is derived from the fulfilment of certain conditions (criteria based on local conditions, type of CG and CG use) and evaluated on a scale of 0, 1, 2 and 3. The evaluator chooses a rating of 0–3 according to the extent to which the measure meets the key criteria that have been set for the chosen level. In the case of CGs, the key criteria involve water accumulation from roofs of surrounding properties, importance of the growing function, extent of composting, etc. Such qualitative valuation based on MCDA and rating was applied to individual ES and their provision in all three valuated scenarios. The CG conditions corresponding to the ‘No crisis’ scenario were considered the baseline scenario for the valuation of the level of ES provided. The ES valuation for the other two scenarios, i.e., ‘COVID-19’ and ‘FSP’, then corresponds to the level of ES provision with respect to the baseline.

2.3.4. Quantitative Valuation and Economic Assessment of ES Provided by the CG in Different Scenarios

A large number of methodologies and recommendations on how to conduct quantitative economic assessment of green and blue infrastructure elements can be found around the world (e.g., [9,43,44]). In Czechia, a methodology for the economic assessment of green and blue infrastructure in human settlements has been developed based on foreign and domestic experience [45]. It provides recommended procedures for conducting economic valuation of individual ES, taking into account the availability of necessary data. It also includes an overview of basic biophysical values, e.g., the amount of water retained in relation to different surfaces or the amount of pollutants captured from the air.

After the identification of important ES and their qualitative valuation based on the methodology described in Section 2.3.3, various input data were collected to express individual ES in the form of biophysical units and to evaluate them monetarily afterwards. Some of the primary data were provided by the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG coordinator (e.g., area of growing beds), the rest were set based on transferring available information from studies already completed in another location (e.g., [46]) and expert estimation based on field study and local conditions such as annual precipitation, type and amount of buildings (flats) in the surroundings.

Available market prices and various economic valuation methods were used to express and compare individual ES provided by the CG in monetary value. Economic assessment and valuation methods were applied based on the mentioned certified methodology for Czechia [45]. Given the objective of valuing the ES provided under different conditions (i.e., scenarios), the approach of annual benefits expressed in 2023 prices was chosen for the economic assessment of ES provided by the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG. Runoff regulation was expressed in monetary value using data on precipitation episodes in the area [47] and the available market prices of wastewater treatment [48]. The monetary value of air quality improvements and CO2 reduction were derived using the pollutant removal capacity of greenery, market prices of similar measures with the same effect combined with the market price of carbon dioxide equivalent in the EU ETS in the case of CO2 reduction [45,49].

Crop production and biomass production are expressed in monetary value using available data from the semi-structured interviews with the CG coordinator and studies on average market prices of crops and compost produced in CGs [23,24,50]. Specifically, the study in [50] on the average production and its expression in monetary values in a CG in the Czechia was used to quantify the value of crop production. The economic value of production was assumed as the average between the value of crops in conventional and organic quality based on [50].

The aesthetic improvement to buildings in the direct vicinity was assumed in the form of a 1% rent increase for all buildings next to the CG. Rent prices in the area and available studies [45,49] of rent percentage increases were used to express this ES in monetary value. Finally, educational ES was valuated using the number of events for pupils and adults in the CG and prices of similar events taking place in the area. Other ES were not considered in the assessment, as necessary input data were not available for the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG (see Section 4).

3. Results

3.1. CG Members and Motivation Factors for Joining the CG

Four of the survey respondents from ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG members (n = 6), were women. The responses were collected from members aged from 34 to 60 with, at least, high school or higher education (bachelor’s or master’s degree of university education). All of them had previous experience in crop production, and three of them were growing crops elsewhere (on the balcony and in their own gardens at home, holiday home or relatives). Their main reason for becoming a CG member was to actively spend free time with children outside (n = 3), meet other people in the community (n = 1) and grow food (n = 2). Based on the QS, it is also possible to identify the factors that influence CG members’ visits to the CG nowadays. Each member could choose the three most important factors from the 10 predefined ones. As is apparent from Table 1, the most important factors are those related to socialisation, leisure time, including the joy of growing, and then passing on this experience to children.

Table 1.

Frequency of selection of individual motivating factors by ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG members (n = 6).

3.2. Changes in Operation and Use of CG Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a decrease in the frequency of visits to the case study CG among some of the original gardeners, mainly due to restrictions, as emerged from the QS among CG members (Section 2.3.2). One of the men even stopped visiting the garden altogether. In only one case was the decline caused by an effect other than the pandemic itself. Furthermore, as emerged from the interviews with the CG coordinator (Section 2.3.1), older people visited the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG less, while, on the contrary, the garden became a peaceful place for parents with children and was visited more frequently by them than in the prepandemic period.

The coordinator also noticed more interest in the CG among people who were looking for a place to spend their leisure time during the pandemic. As a result, the overall number of members increased because of the new demand from people who were interested in new activities during the lockdowns. The interviews revealed that the number of members in the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG increased almost three times (from 10 to 29). According to the case study CG coordinator, the increase in interest in membership was linked to the COVID-19 pandemic: “I think in a way the COVID-19 pandemic helped us a lot and brought in new members because people wanted to spend their time in a meaningful way”. The coordinator further acknowledged that such membership may have been temporary for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, educational activities involving pupils, seminars and workshops were cancelled because of the COVID-19 restrictions. Because of the greater number of new gardeners, the growing area expanded significantly because of the new demand—by half of the previous area (by 100 to 300 m2). On the other hand, no general conclusions concerning changes to the growing activities can be deducted from the QS among the surveyed gardeners who had been growing in the CG before the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey showed that some members did not change their growing habits during the COVID-19 pandemic, some increased their production because they had more free time, and some either stopped growing altogether or modified their crops because of less frequent visits to the garden. The results also indicate that production is influenced, to some extent, by occupation and the difficulty of its performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some respondents also reported that they had left the city and moved to a holiday home during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, for example. Thus, there is a wide range of factors that affected the production function of CGs in general.

3.3. Possible Increase in Crop Production

As a result of increasing food prices and greater demand for FSP, people are increasingly interested in growing more, as confirmed by the QS among the members of the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG (Section 2.3.2). The survey found that half of the responding CG members would be willing to increase the growing area if the prices increased further and four out of the six current members would be willing to expand production if they were motivated to do so by some type of crisis, for instance, connected to losing a job or a decline in family income. In most cases, however, the responding CG members perceived that it would not be possible to increase production in the CG, due to space constraints, to the extent that they would be able to grow enough produce there to significantly reduce their food expenditures or even allow them to sell the surplus. However, the interviews with the case study CG coordinator confirmed that there is still space for more people and crop production in the CG, especially if the grassy area was replaced. Therefore, according to the interviews with the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG coordinator, the growing area of the case study CG could be increased three times in comparison to the initial baseline ‘No crisis’ scenario (from 200 to 600 m2).

3.4. ES Provided by CG in Different Scenarios

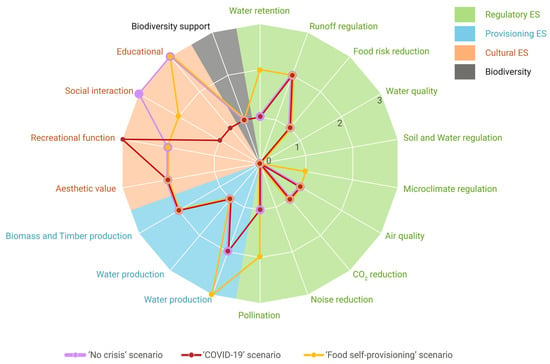

The ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG provides benefits for its members and the wider surrounding area that falls into all ES categories, i.e., ES related to regulation, provisioning, culture and biodiversity support. However, the qualitative level of these ES varies across the scenarios evaluated. Figure 4 shows how ES provision changes depending on the different scenarios, as described in Section 2.2, i.e., ‘No crisis’; ‘COVID-19’; and ‘Food self-provisioning’ scenarios. The level of ES provision is set based on multicriteria decision analysis, described in Section 2.3.3.

Figure 4.

Ecosystem services provided by CG in ‘No crisis’; ‘COVID-19’; and ‘Food self-provisioning’ scenarios.

In the ‘No crisis’ scenario, the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG contributes to greater water retention on the site and runoff regulation as rainwater is accumulated from a part of the roofs of the surrounding buildings, which would otherwise drain into a combined sewer system. The planted greenery improves the microclimate and air quality, reduces CO2 and provides space for pollinators. The crop production is an important ES provided and also biomass production as the possibility of composting plant residues is present. The existence of the CG also improves the aesthetic value of surrounding properties. In this ‘No crisis’ scenario, the CG serves as a place for recreation for its members and, in the case of events, for the public. In terms of socialisation and educational ES, community involvement and regular educational and leisure projects and the presence of informational signs are important.

In the ‘COVID-19’ scenario, the level of ES provided by the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG remains the same as in the ‘No crisis’ scenario for all regulatory and provisioning ES, and also for biodiversity. However, because of the inability to meet in larger numbers and hold public events in the CG, the level of cultural ES changes. In particular, the importance of social interaction ES and of educational ES provided by the CG decreases significantly. On the contrary, the role of the CG as a place for recreation increases significantly. In terms of crop production, although the level of provisioning ES has not risen compared to the baseline ‘No crisis’ scenario, there has been an increase in the number of members who grow; therefore, the total production in absolute terms increased.

In the ‘Food self-provisioning’ scenario, the most significant changes in ES importance can be observed for provisioning and cultural ES. Compared to the two previous scenarios, the provisioning ES increase has become the most important ES function in the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG. However, this is compensated by a decline in recreational ES, as the recreational space in the CG decreases at the expense of the growing area. On the other hand, social interaction as a part of the growing is still present but not as important as in the ‘No crisis’ scenario.

3.5. Economic Assessment of ES Provided by the CG in Different Scenarios

The ES provided and their changes according to scenarios were also valued in monetary terms. The valued ES for each scenario in EUR per year are shown in Table 2. It shows that for all scenarios, the most important monetarily valued ES of the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG are cultural ES, followed by provisioning and regulatory ES. In the ‘COVID-19’ scenario, the absence of educational ES does not play a significant role in terms of monetarily expressed ES, and the increase in the provisioning ES due to the increase in members in the CG and, thus, the expansion of the growing area is more important. In the ‘Food self-provisioning’ scenario, the emphasis on the crop production is the most significant ES related to the monetary expression.

Table 2.

Economic assessment of ES provided by CG in different scenarios.

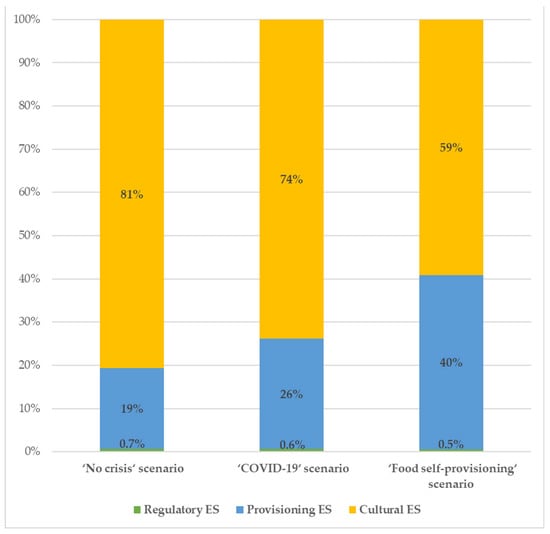

The economic value of all of the included ES of the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG differs across the assessed crisis scenarios and varies from EUR 54,206 per year in the ‘No crisis’ scenario to EUR 58,878 per year in the ‘COVID-19’ scenario to EUR 73,947 per year in the ‘Food self-provisioning’ scenario. The relative contributions of individual monetarily expressed ES provided by the CG in the different scenarios to the total economic value in each scenario are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Relative contribution of monetarily expressed ES provided by CG in different scenarios.

The cultural ES provided by the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG are the most important benefits in all of the scenarios, regardless of a crisis or non-crisis situation, as their contribution to the overall economic value is 81%, 74%, and 59%, depending on the scenario. Considering the COVID-19 crisis and the crisis induced by the increase in food prices, the importance of provisioning ES increases in the studied CG, ranging from 19% to 26% and 40%, depending on the scenario. From the point of view of the financial assessment, the crises do not significantly affect the provision of regulatory ES by the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG.

4. Discussion

The results of the economic assessment of the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG are consistent with the findings of other research (e.g., [1,22,34]) focusing on the prepandemic period, which show that the primary function of CGs is providing cultural ES (e.g., recreation, enjoyment of gardening and opportunities to socialize). However, a change in the primary function may occur due to social change (e.g., war, increase in inflation or unemployment or the COVID-19 pandemic). The potential of provisioning ES is realised more when access to food is limited by its availability or because of relatively high prices given by the market situation, such as in times of crisis [27]. As with other forms of urban gardening, the importance of CGs varies according to the current local situation in terms of social and economic conditions. The motivation of the Global North to grow crops has not been driven by material need in recent years but rather by an interest in the origin of the crops and a general change in lifestyle [7,51,52]. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, gardening was important to many people not only to be close to nature but also for individual stress release [53]. CGs also, according to the coordinators, often became a safe place for gardeners to meet their neighbours [54]. As also mentioned in [3], incorporating urban gardening into sustainable urban planning is a way to mitigate negative social consequences in times of the uncertain future development of food security [3]. A partial motive to support the establishment of CGs could also be the desire to gain control over food production capacities and support local chains [33].

As the survey among ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG members shows, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their behaviour as a CG member varied significantly. An analysis of the data from the same questionnaire survey among members of other CGs across Czechia (final results not published yet) suggests that, compared to smaller cities, visits to CGs in large cities tended to increase during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is also the case for the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG, which serves as the case study. As interviews with the coordinators in other CGs in Czechia showed, it was mainly elderly people who limited their visits the most due to health concerns, but the overall number of members increased during the pandemic period. There was also increased interest in CG membership at the beginning of the pandemic, as confirmed by both authors’ interviews with coordinators of Czech CGs and by other studies [54,55,56].

Current studies [9,14] show a wide range of ES provided by CGs. The present study shows that the quality and quantity of ES did not decrease significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to provisioning and cultural ES, regulatory ES play an important role. However, regulatory ES are only included in the monetary valuation to a limited extent in this and most other studies [57,58]. A lack of data to quantify some ES is a general limitation of valuation studies. In particular, there is a lack of the inclusion of microclimate regulation and biodiversity support in the monetary valuation. CGs provide these benefits for society, as they are part of urban green infrastructure. These ES are often highlighted in the literature but rarely quantified in relation to CGs due to both missing data and methodologies for their proper monetary expression. However, the main objective of this study was to demonstrate how the ES provided by CGs are affected in times of differently induced social crises. According to the qualitative assessment (see Figure 4), the provision of regulatory ES was not affected significantly by COVID-19 and higher food prices in comparison to cultural and provisioning ES. Thus, not including a broader range of regulatory services does not result in a bias towards the objective of this article. However, the overall value of the benefits expressed in monetary value is underestimated equally under each scenario. In addition to the value of the benefits, quality of life is further enhanced by the provision of other regulatory services, such as cooling the microclimate, improving air quality and promoting pollination. Because of the fact that the area had the appearance of unmaintained green space prior to the establishment of the CG, the majority of these services have been provided over the long term regardless of the establishment of the garden.

Considering the objective of this study, it was necessary to combine different methods that built on each other. The first two scenarios (‘No crisis’ and ‘COVID-19’) are based on the actual state of the garden or the change in use due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The scenario that examined the increase in food self-sufficiency assumed an increase in interest in growing one’s own food. This assumption is not based on the current survey but is linked to a 2021 QS, which also examined members’ preferences for behavioural change, reflecting different hypothetical situations. One possible response to the negative effects of crises was the option to increase crop production in order to reduce expenditures on food (see Section 2.3.2). Testing this assumption should be the next research objective. However, in the real world, changes in crop production should be expected with some delay because of the growing season and members’ ability to react or adapt to the manifestations of price changes. Approaches to economic assessment differ in different countries according to long-term practices. The approach applied in the present paper is similar to approaches used in the USA to evaluate a wide range of blue and green infrastructure elements [43] or in Portugal to evaluate green roofs [59]. On the contrary, it is possible, especially in a German-speaking environment, to encounter complete rejection of an economic assessment of ES using the expression of costs and benefits in monetary values (e.g., [60]) for several reasons. Although the authors of the present study are aware of these limitations, they used the benefit quantification method for the purpose of a comprehensible economic argument to demonstrate the impacts of the subscenarios not only in qualitative terms.

5. Conclusions

In most European countries, the crises that are currently affecting urban gardening are those related to the COVID-19 pandemic and also to the increase in food prices. Demonstrating the impact of these social crises on ES provided by CGs compared to the situation before them was the main objective of this study. Based on a case study of the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG in Ústí nad Labem, Czechia, it was shown that the crisis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions caused more interest in production among most of the current and also new members but resulted in a decline in social interactions and public events. In the case of the crisis associated with the increase in food prices, there has been increased emphasis on production and a desire to increase FSP, instead of recreation and leisure. However, neither crisis modelled had an impact on regulating ES and biodiversity support provided by the CG. The results of the economic assessment further show that despite not expressing all benefits in monetary value, the CG provides annual societal benefits ranging from EUR 2030 to 2853 per member.

These results demonstrate not only the multifunctional function of CGs for urban dwellers but also their adaptability to the current dynamic conditions that prevail in modern cities. The capacity to adapt to societal changes without significantly reducing their qualitative and quantitative importance is a lesson to be learned for planning other adaptation measures in cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.M., M.H. and L.D.; methodology, J.M.; validation, J.M., M.H. and L.D.; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, J.M., L.D. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., L.D. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and M.H.; visualisation, M.H.; supervision, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Technology Agency of the Czech Republic, grant number TL05000718, project “Society’s greater resilience to the effects of crisis through increasing food self-sufficiency” and by Operational Programme Research, Development and Education of the Czech Republic, grant number CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/17_048/0007435, project “Smart City–Smart Region–Smart Community”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All the authors desire to express their sincere gratitude to the coordinator and members of the ‘Žížala na Terase’ CG for providing valuable information, which was essential in carrying out the valuation of the different scenarios presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Birky, J.; Strom, E. Urban Perennials: How Diversification Has Created a Sustainable Community Garden Movement in The United States. Urban Geogr. 2013, 34, 1193–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.; Keim, J.; Engelmann, R.; Kraemer, R.; Siebert, J.; Bonn, A. Ecosystem Services of Allotment and Community Gardens: A Leipzig, Germany Case Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.; Crumley, C.; Svedin, U. Bio-Cultural Refugia—Safeguarding Diversity of Practices for Food Security and Biodiversity. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škamlová, L.; Wilkaniec, A.; Szczepańska, M.; Bačík, V.; Hencelová, P. The Development Process and Effects from the Management of Community Gardens in Two Post-Socialist Cites: Bratislava and Poznań. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, A.; Schützenberger, I. Creative Natures. Community Gardening, Social Class and City Development in Vienna. Geoforum 2018, 92, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okvat, H.A.; Zautra, A.J. Community Gardening: A Parsimonious Path to Individual, Community, and Environmental Resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 47, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubová, L.; Macháč, J.; Vackova, A. Food Provision, Social Interaction or Relaxation: Which Drivers Are Vital to Being a Member of Community Gardens in Czech Cities? Sustainability 2020, 12, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, L.; Lawson, L.J. Results of a US and Canada Community Garden Survey: Shared Challenges in Garden Management amid Diverse Geographical and Organizational Contexts. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubová, L.; Macháč, J. Improving the Quality of Life in Cities Using Community Gardens: From Benefits for Members to Benefits for All Local Residents. GeoScape 2019, 13, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, W.V.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Hassan, R.; et al. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being—Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59726-040-4. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure. 2018. Available online: https://cices.eu/content/uploads/sites/8/2018/01/Guidance-V51-01012018.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Russo, A.; Escobedo, F.J.; Cirella, G.T.; Zerbe, S. Edible Green Infrastructure: An Approach and Review of Provisioning Ecosystem Services and Disservices in Urban Environments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 242, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, M.; Hamlin, S.; Richard, S.I. Uprooting Urban Garden Contamination. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 142, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendov, N.M. Comparative Study on the Motivations That Drive Urban Community Gardens in Central Eastern Europe. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2018, 16, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordon, S.; Miller, P.A.; Bohannon, C.L. Attitudes and Perceptions of Community Gardens: Making a Place for Them in Our Neighborhoods. Land 2022, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, N.; Stuhlmacher, M.; Miles, A.; Uludere Aragon, N.; Wagner, M.; Georgescu, M.; Herwig, C.; Gong, P. A Global Geospatial Ecosystem Services Estimate of Urban Agriculture. Earths Future 2018, 6, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.M.; Hiner, C.C. Siting Urban Agriculture as a Green Infrastructure Strategy for Land Use Planning in Austin, TX. Chall. Sustain. 2016, 4, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, S.T.; Taylor, J.R. Supplying Urban Ecosystem Services through Multifunctional Green Infrastructure in the United States. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zick, C.D.; Smith, K.R.; Kowaleski-Jones, L.; Uno, C.; Merrill, B.J. Harvesting More Than Vegetables: The Potential Weight Control Benefits of Community Gardening. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twiss, J.; Dickinson, J.; Duma, S.; Kleinman, T.; Paulsen, H.; Rilveria, L. Community Gardens: Lessons Learned From California Healthy Cities and Communities. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1435–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmin-Pui, L.S.; Griffiths, A.; Roe, J.; Heaton, T.; Cameron, R. Why Garden?—Attitudes and the Perceived Health Benefits of Home Gardening. Cities 2021, 112, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C. Mapping Urban Agriculture in Portugal: Lessons from Practice and Their Relevance for European Post-Crisis Contexts. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vávra, J.; Daněk, P.; Jehlička, P. What Is the Contribution of Food Self-Provisioning towards Environmental Sustainability? A Case Study of Active Gardeners. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovová, L. Self-Provisioning, Sustainability and Environmental Consciousness in Brno Allotment Gardens. Soc. Stud. Soc. Stud. 2015, 12, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnavaud, H. Part 1—french allotment gardens: An historical type of garden which renews itself. In Urban Allotment Gardens in European Cities Future, Challenges and Lessons Learned; COST Action TU1201; Frederick University: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martinho da Silva, I.; Oliveira Fernandes, C.; Castiglione, B.; Costa, L. Characteristics and Motivations of Potential Users of Urban Allotment Gardens: The Case of Vila Nova de Gaia Municipal Network of Urban Allotment Gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Calvet, M.; Langemeyer, J.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; March, H. Sowing Resilience and Contestation in Times of Crises: The Case of Urban Gardening Movements in Barcelona. Partecip. Conflitto 2015, 8, 417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, J.L.; Childs, D.Z.; Dobson, M.C.; Gaston, K.J.; Warren, P.H.; Leake, J.R. Feeding a City—Leicester as a Case Study of the Importance of Allotments for Horticultural Production in the UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovová, L. Grow, Share or Buy? Understanding the Diverse Economies of Urban Gardeners. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ančić, B.; Domazet, M.; Župarić-Iljić, D. “For My Health and for My Friends”: Exploring Motivation, Sharing, Environmentalism, Resilience and Class Structure of Food Self-Provisioning. Geoforum 2019, 106, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lim, M.S.; Richards, D.R.; Tan, H.T.W. Utilization of the Food Provisioning Service of Urban Community Gardens: Current Status, Contributors and Their Social Acceptance in Singapore. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, V. The Contribution of Urban Garden Cultivation to Food Self-Sufficiency in Areas at Risk of Food Desertification during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Madrid-Lopez, C.; Mendoza Beltran, A.; Villalba Mendez, G. Urban Agriculture—A Necessary Pathway towards Urban Resilience and Global Sustainability? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausi, L.; Amodio, M.; Sebastiani, A.; Fusaro, L.; Manes, F. Assessing cultural ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic at the garden of ninfa (Italy). Ann. Bot. 2022, 12, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.-K.; Sparke, K. Self-Reported Well-Being and the Importance of Green Spaces—A Comparison of Garden Owners and Non-Garden Owners in Times of COVID-19. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, N.; Wende, W. Physically Apart but Socially Connected: Lessons in Social Resilience from Community Gardening during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 223, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattivelli, V. Social Innovation and Food Provisioning Initiatives to Reduce Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cities 2022, 131, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech Statistical Office Podíl nezaměstnaných osob v krajích k 30. 6. 2023. Available online: https://www.czso.cz/csu/xc/mapa-podil-kraje (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Czech Statistical Office Počet obyvatel v obcích—k 1.1.2020. Available online: https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/pocet-obyvatel-v-obcich-k-112019 (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Czech Statistical Office Indexy spotřebitelských cen—inflace—Leden. 2023. Available online: https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/cri/indexy-spotrebitelskych-cen-inflace-leden-2023 (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Trading Economics Euro Area Food Inflation—July 2023 Data—1997–2022 Historical—August Forecast. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/euro-area/food-inflation (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Macháč, J.; Hekrle, M.; Louda, J.; Brabec, J. Metodika pro Hodnocení Adaptace Hl. m. Prahy Na Změnu Klimatu z Pohledu Ekosystémových Služeb. 2022. Available online: https://klima.praha.eu/data/Dokumenty/Dokumenty%202023/machac_et_al_update2023.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Center For Neighborhood Technology. The Value of Green Infrastructure. A Guide to Recognizing Its Economic, Environmental and Social Benefits. 2010. Available online: https://cnt.org/sites/default/files/publications/CNT_Value-of-Green-Infrastructure.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Schoen, V.; Caputo, S.; Blythe, C. Valuing Physical and Social Output: A Rapid Assessment of a London Community Garden. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macháč, J.; Dubová, L.; Louda, J.; Hekrle, M.; Zaňková, L.; Brabec, J. Methodology for Economic Assessment of Green and Blue Infrastructure in Human Settlements; Institute for Economic and Environmental Policy, Faculty of Social and Economic Studies, Jan Evangelista Purkyně University: Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hekrle, M.; Liberalesso, T.; Macháč, J.; Matos Silva, C. The Economic Value of Green Roofs: A Case Study Using Different Cost–Benefit Analysis Approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ČHMÚ Portál ČHMÚ: Historická Data: Počasí: Územní Srážky. Available online: https://www.chmi.cz/historicka-data/pocasi/uzemni-srazky# (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- SCVK Cena Vodného a Stočného—Severočeské Vodovody a Kanalizace, a.s. Available online: https://www.scvk.cz/vse-o-vode/ceny-vody/ (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Macháč, J.; Hekrle, M. Modrozelená Města: Příklady Adaptačních Opatření v ČR a Jejich Ekonomické Hodnocení. Available online: https://www.ieep.cz/modrozelena-mesta-priklady-adaptacnich-opatreni-v-cr-a-jejich-ekonomicke-hodnoceni/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Macek, D. Production Function of Community Gardens. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of Social and Economic Studies, Jan Evangelista Purkyně University, Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Duží, B.; Tóth, A.; Bihuňová, M.; Stojanov, R. Challenges of Urban Agriculture: Highlights on the Czech and Slovak Republic Specifics. In Current Challenges of Central Europe: Society and Environment; Univerzita Karlova v Praze: Prague, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 82–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pícha, K.; Navrátil, J. The Factors of Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability Influencing Pro-Environmental Buying Behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, M.; Lin, B.; Kingsley, J.; Marsh, P.; Diekmann, L.; Ossola, A. Gardening Can Relieve Human Stress and Boost Nature Connection during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 68, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanbacher, W.D.; Cavendish, J.C. The Effects of COVID-19 on Central Florida’s Community Gardens: Lessons for Promoting Food Security and Overall Community Wellbeing. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1147967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, J.; Okely, J.A.; Taylor, A.M.; Page, D.; Welstead, M.; Skarabela, B.; Redmond, P.; Cox, S.R.; Russ, T.C. Home Garden Use during COVID-19: Associations with Physical and Mental Wellbeing in Older Adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Nigon-Crowley, A.; Kirkpatrick, K.; Katoch, C. Community Gardening during Times of Crisis: Recommendations for Community-Engaged Dialogue, Research, and Praxis. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 10, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekrle, M. What Benefits Are the Most Important to You, Your Community, and Society? Perception of Ecosystem Services Provided by Nature-Based Solutions. WIREs Water 2022, 9, e1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teotónio, I.; Silva, C.M.; Cruz, C.O. Economics of Green Roofs and Green Walls: A Literature Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.O.; Silva, C.M.; Teotónio, I. Green Infrastructures: Cost Benefit Analysis [Infraestruturas Verdes: 718 Análise Custo Benefício]; IST Press—Instituto Superior Técnico: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dehnhardt, A.; Grothmann, T.; Wagner, J. Cost-Benefit Analysis: What Limits Its Use in Policy Making and How to Make It More Usable? A Case Study on Climate Change Adaptation in Germany. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).