1. Introduction

In 1950, there were 752 million people living in metropolitan areas; today, that number has increased to 4.2 billion [

1]. According to the United Nations’ “World’s Urbanization Prospect, 2018,” the global urban population is expected to increase from its current level of 55.7 percent to 68 percent by 2050, implying the addition of 2.5 billion people to the urban population in that time. In addition, over 90% of this growth is expected to occur in Asia and Africa [

2]. Slums are common in low- and middle-income nations because of fast urbanization, population growth, rapid rural-to-urban migration, low-income planning, economic stagnation, high unemployment rates, natural disasters, armed conflict, and social unrest, which leaves residents without enough access to essential services and infrastructure and leaving many in dire financial straits [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Urban populations continue to rise, but government institutions rarely keep up with the need for serviced land equipped with the necessities [

10,

11]. Because of the skyrocketing cost of land in urban regions, low-income families have no choice but to make their homes in undeveloped and underdeveloped areas (slums) with inadequate infrastructure [

11]. South Asian slums have also become an important part of urbanization, a fact highlighted in “The New Urban Agenda” (United Nations Human Settlements Programme [

12].

Slums are densely populated neighborhoods that were not considered during the city’s initial design phase [

13,

14,

15]. According to the Indian Census, slums are neighborhoods where people live in conditions that pose a threat to their health and safety, such as dilapidation, overcrowding, poor building design, narrow streets, a lack of ventilation and light, and inadequate sanitation [

16]. It has divided the slums into three groups: those that had been notified, those that had been recognised, and those that had been identified. Areas of a city that have been designated as slums in accordance with the Slum Act have been “notified” to the city. Slums that have been “recognised” by the government of a state or union territory but have not been formally designated as such under any law are nevertheless considered “slums” (UT). The Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation GoI defines slums as densely populated places with a minimum of 300 people and roughly 60–70 households living in overcrowded, substandard housing conditions.

Approximately 30 percent of the urban population in developing countries currently resides in slums, which includes about 1 billion people today [

3]. If current trends continue, the number of people living in slums will reach 2 billion in 2030 and 3 billion in 2050 [

17]. These are locations without adequate sanitation, clean water, land tenure security, housing, or living space [

13]. Health, education, child mortality, social and political marginalization, and many other factors are all influenced by the presence of slums [

18]. Between 2014 and 2050, the world’s urban population is predicted to rise by a total of 37%, with 37% of that growth occurring in India, China, and Nigeria [

19]. Records from the 2011 Census show that 22.4% of India’s total population lives in slums [

20]. Rough estimates show that 17.4 percent of urban Indian homes, or over 200 million people, live in slums [

21]. This equates to about 13.7 million households. The central government in India has sponsored numerous initiatives to improve the living conditions of India’s urban poor, with the goals of eliminating, legalizing, and redeveloping informal settlements [

22]. Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY), Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, etc. are just some of the many programmes implemented by the Government of India to remove the slums [

23]. In order to facilitate in situ renovation of houses and overall settlement upgrading, these plans have recently centered on mass evictions, relocation of slum and pavement occupants, and other similar initiatives [

24]. However, the rate at which unplanned communities are sprouting up is matching that at which urban slums are being cleared. The increasing number of people living in slums poses a threat to the government officials who are tasked with maintaining order there. Rapid changes in the form, size, and conditions of informal settlements leave them especially susceptible to catastrophes such as fire and flood [

25]. The land use and ecological sustainability suffers as a result of urbanization. Therefore, cutting-edge methods must be implemented promptly if the idea of sustainable growth is to progress [

26]. For achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals [

27], it is a very challenging task in developing nations to provide access to clean water and sanitation. Nearly 30 years of debate on how to best handle these settlements has apparently culminated in widespread consensus among a range of parties, that improving the settlements in situ is the best course of action [

28]. Slum upgrading is crucial to achieving the sustainable development aim and bettering the current situation. Slum infrastructure and the quality of life for slum residents will undeniably benefit from this type of modernization. The administration must act swiftly to save the worst slums in this scenario [

29].

Prior studies on slum research focused on (a) socio-economic and policy [

30,

31,

32] and (b) geo-physical characteristics using approaches such as remote sensing [

33,

34,

35]. Moreover, recent research into slum characteristics has also focused on automatic feature extractions using cellular automata (CA) and agent-based models (ABMs) [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Water, sanitation, adequate living space, adequate structure, kitchen and cooking fuel, bathrooms, and electricity are just some of the seven criteria that were used to create a slum severity index in a recent work by [

40]. Slum Severity Index (SSI) based on shelter deprivation in Mexico City was also developed, with the exception of [

41], which used a more robust approach. Their scale, which is based on the UNHABITAT definition of a slum and on insights from the work of [

40], defines a unidimensional measure of SSI that may be adequate for the purposes of their study but is limited in its conceptualization of housing insecurity because it does not consider security of tenure and/or the deficiencies in the built environment of slums. However, other studies have narrowed their focus to one aspect of housing insecurity in order to measure it, whether that be tenure security, the likelihood of eviction, or property rights [

42,

43]. A housing condition framework was applied by [

44] in the slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh, based on four indicators (housing structure, tenure status, housing material, and room density), to determine the correlation between housing conditions and livelihood assets.

Each of the aforementioned approaches results in its own unique set of assumptions and interpretations, providing us with only a fragmented picture of life in slums. Despite their differences, however, these instructors are linked with one another. This paper presents a framework for understanding and studying slums from a combined approach of socio-economic and geo-physical contexts, building on previous research and being motivated by the need for a more holistic approach to studying slums. This approach helps to capture the variability in slum status by identifying developmental needs of the slum, as well as understanding the monitoring and analysis challenges associated with studying slums.

However, advances in remote-sensing technology, emergence of crowdsourced information on slums, and advancements in modelling enable one to better understand the complex nature of slums, and these advancements provide new opportunities to address the problem. With this framework in mind, this paper’s main contribution is twofold: first, it identifies the most pressing issues surrounding slums based on current understandings, and second, it prescribes the treatment to be given for uplifting the slum conditions, which is what policymakers are looking for.

Jammu City in the Western Himalayas, known for its delicate ecosystem, has experienced rapid urbanization over the past 30 years, putting enormous strain on the city’s social infrastructure [

45]. The city dwellers’ physical quality of life is impacted because the city’s development body did not keep up with the rapid urbanization. Since Jammu has the maximum number of slums in Jammu and Kashmir and is going through the rapid development phase including the implementation of a smart city program. In order to overcome the worsening conditions of slums, this study has been carried out to identify the highly deteriorated slums in Jammu based on prioritization matrix analysis, with the incorporation of Management Information System (MIS) and Geographic Information System (GIS).

This research will allow officials to target the most dilapidated slum areas with a huge housing initiative funded by the Government of India’s RAY plan with a focus towards improving residents’ access to essential services.

2. Materials and Methods

Jammu, often known as the “City of Temples”, is located in the south-western district of Jammu and Kashmir at a mean elevation of 327 m above sea level. Its coordinates are 32°43′58.79″ N latitude and 74°51′51.38″ E longitude. With its four Tehsils (Jammu, Akhnoor, Ranbir Singh Pura, and Bishnah), Jammu serves as the divisional headquarters and winter capital of the Jammu and Kashmir Union territory. Temperatures range from 4 °C to 47 °C and 1070 mm of rain falls annually here, indicating a subtropical to moist temperate climate [

46]. The Himalayas to the north and the northern plains to the south surround Jammu City, which has a total size of 240 km

2. The city is enclosed on three sides by the Shivalik Range and on the fourth by the Trikuta Range. In general, the terrain in these regions is hilly, with slopes ranging from moderate to steep and linear ridges standing at a height of a few meters [

47]. A strip of flat ground runs along the city’s southern edge. One can think of the entire district as being split in half by the Jammu–Chhamb road and the Jammu–Pathankot road. There are 152,406 people living in the Jammu district, while the urban area is home to another 657,314 people, as per the 2011 census. Jammu has a population density of 596 people per square kilometer, a population growth rate of 12.48 percent, a sex ratio of 871 females per 1000 males, and a literacy rate of 83.98 percent.

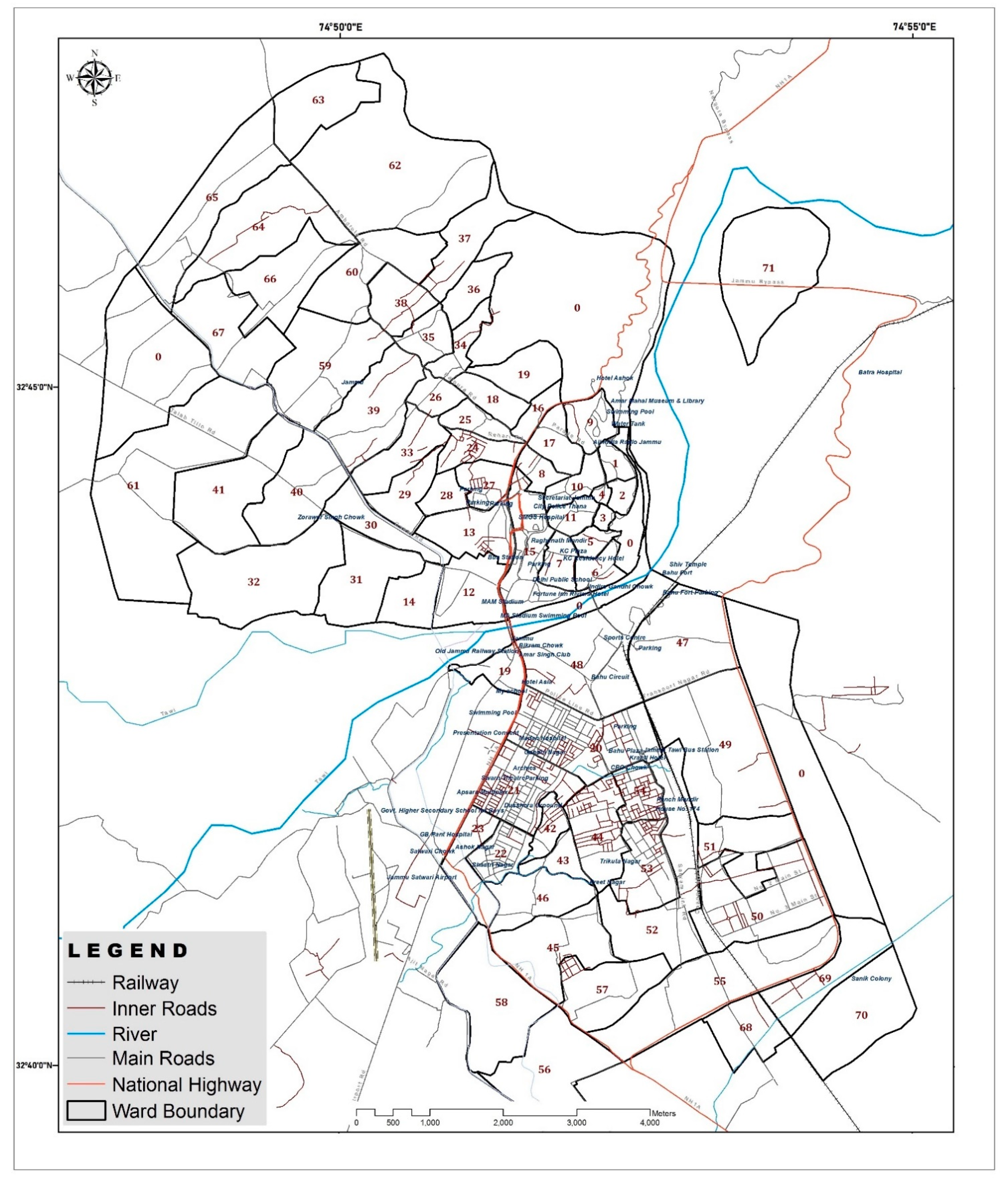

Figure 1 is a basic map of Jammu City.

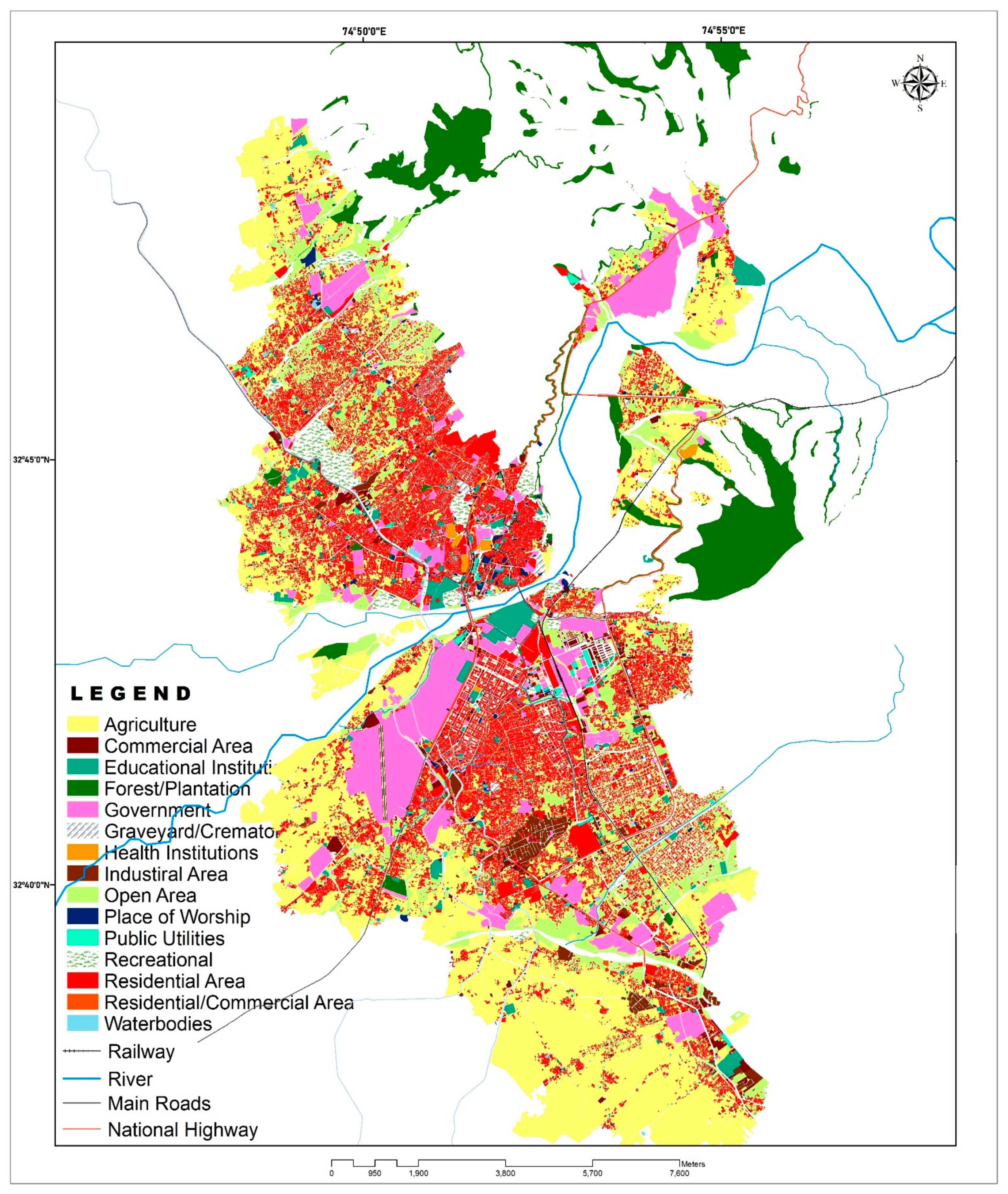

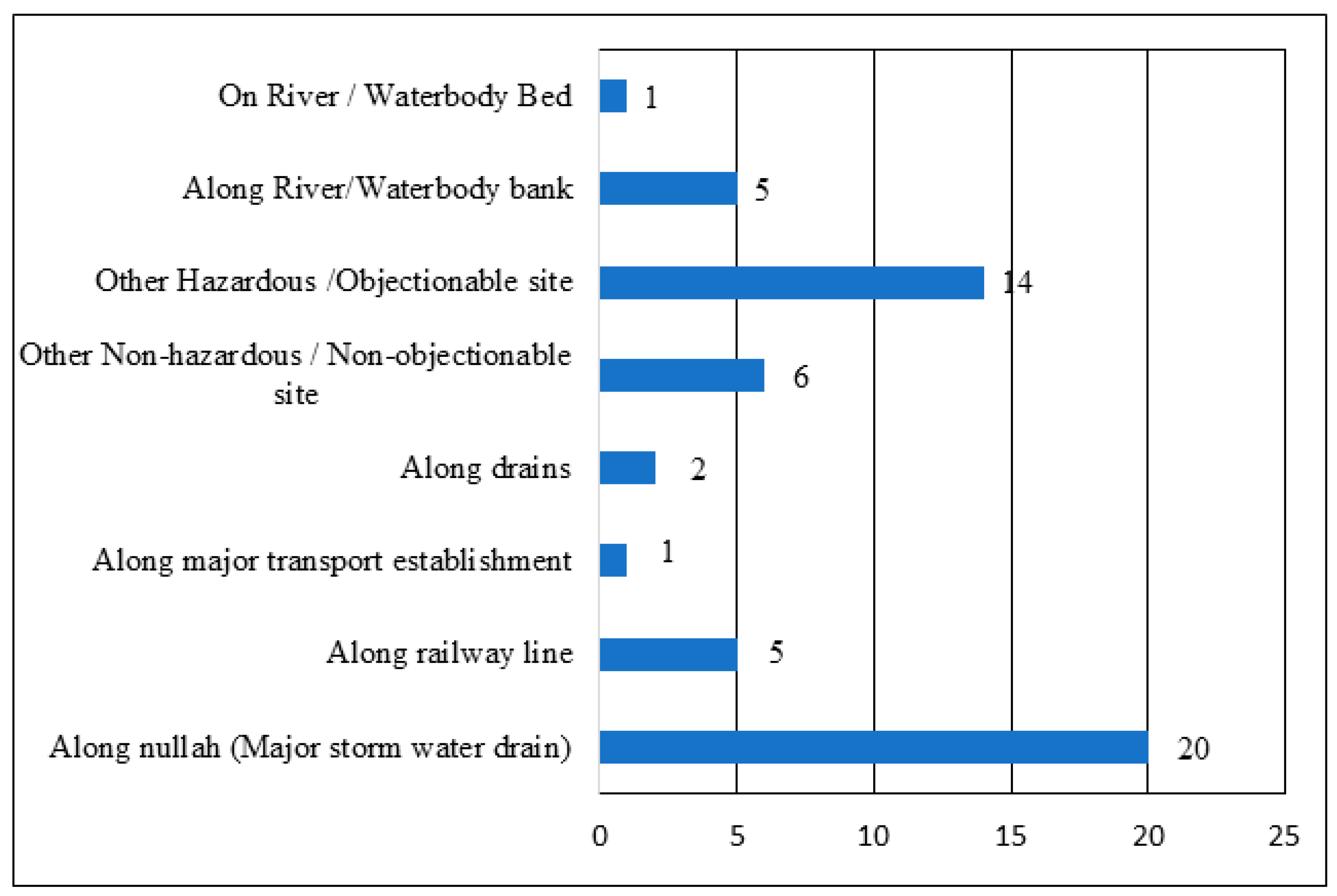

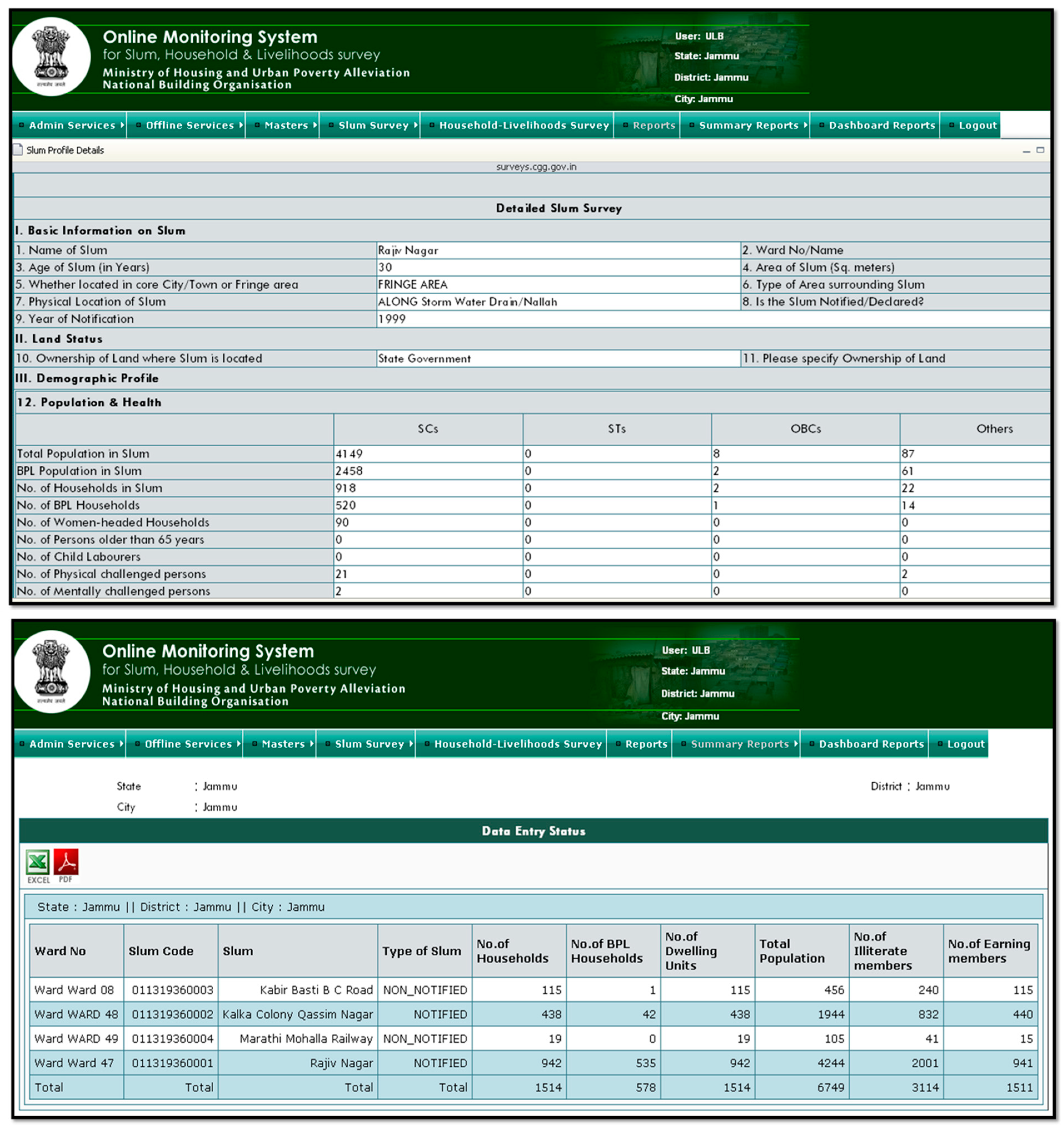

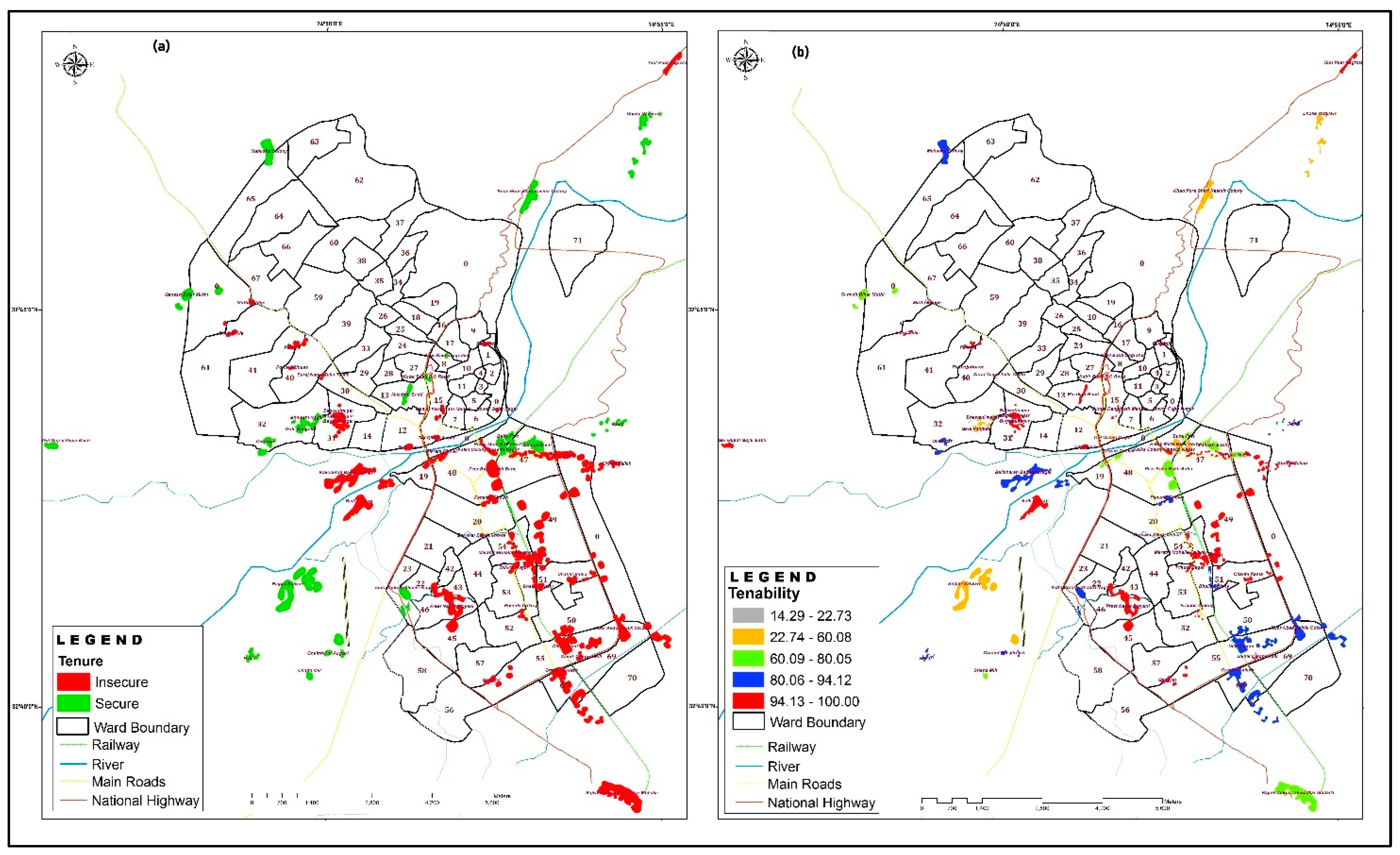

Slum area surveys, maps, a MIS survey, and a matrix analysis form the basis of this study’s conceptual framework. In this research, geo-physical and socio-economic considerations were central to the construction of a slum redevelopment strategy for Jammu City (

Figure 2). The research considers a number of crucial physical criteria, including land use/land cover (LULC), road network, drainage, and current urban facilities. LULC is useful for pinpointing where a land-cover transition has occurred, and how rapidly it has occurred, because it is directly correlated with urbanization (see

Figure 3) [

48]. After georeferencing, the ward boundaries were drawn using Cartosat-1 satellite data with a spatial resolution of 2.5 m, and base layers were created using a map of municipal wards obtained from the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) (

Figure 3). It was not possible to accurately demarcate home borders from Cartosat-1 images, thus GPS coordinates were acquired in order to create a point layer in a geographic information system. Points such as these were clustered together to make ghetto walls.

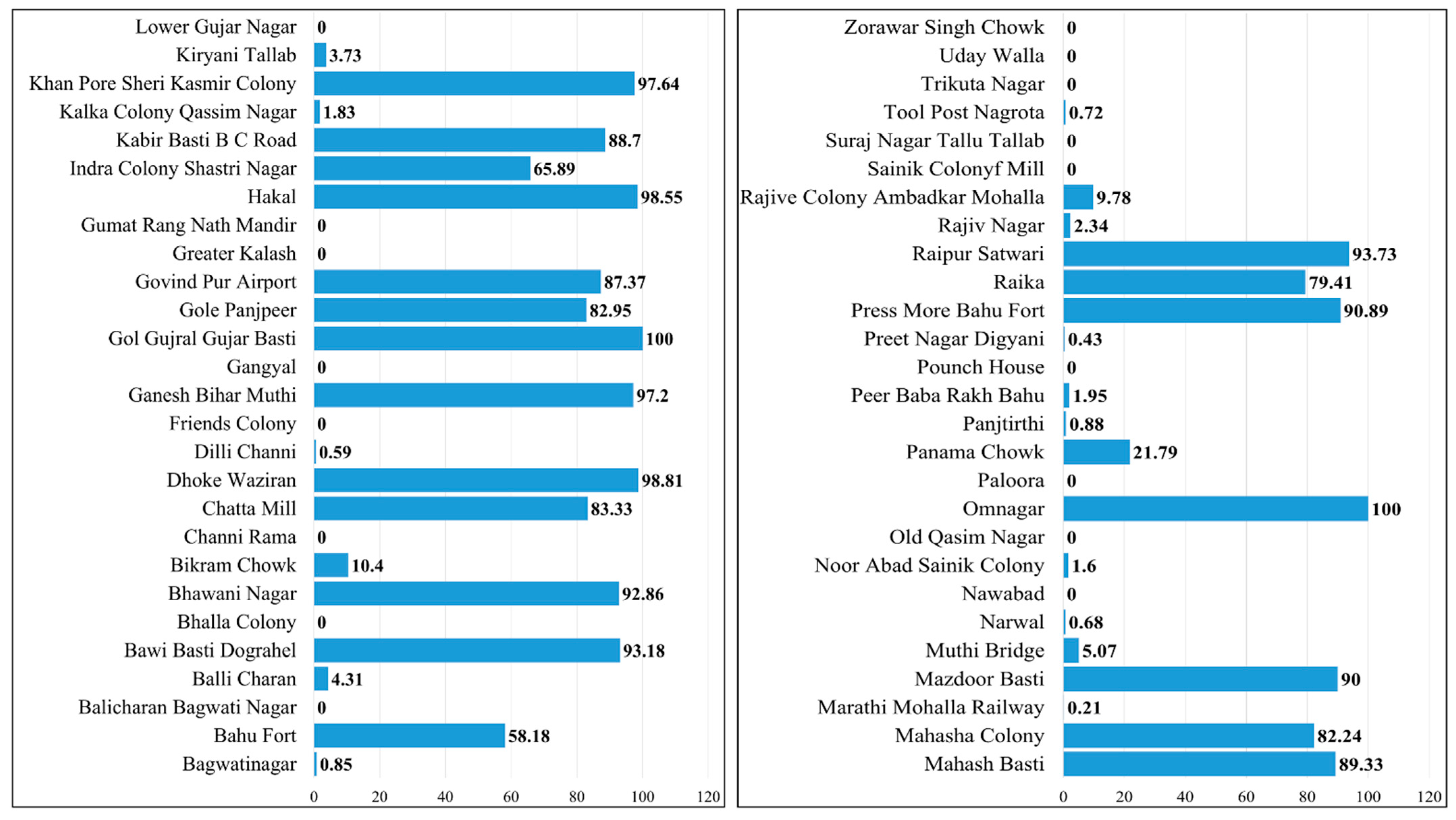

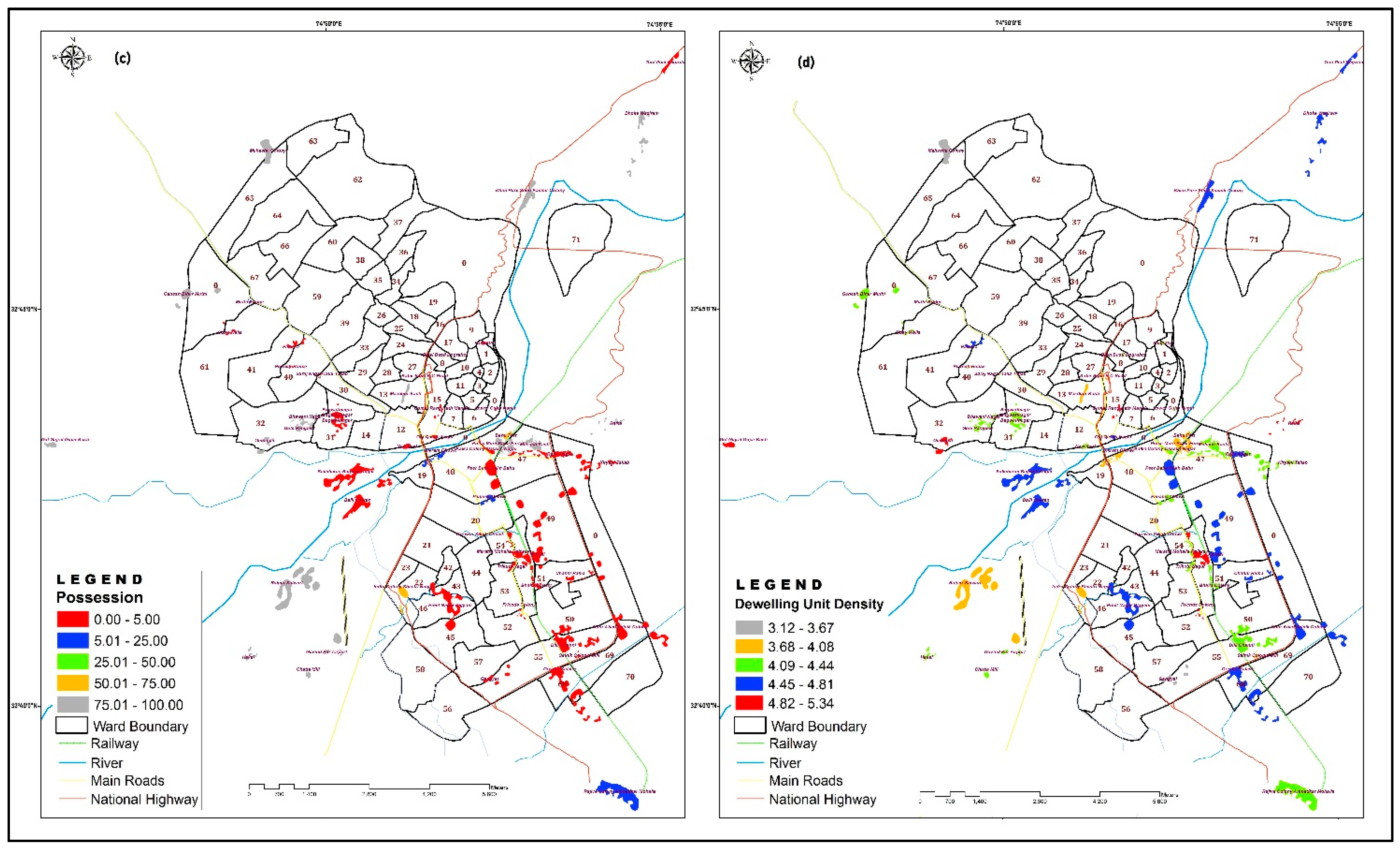

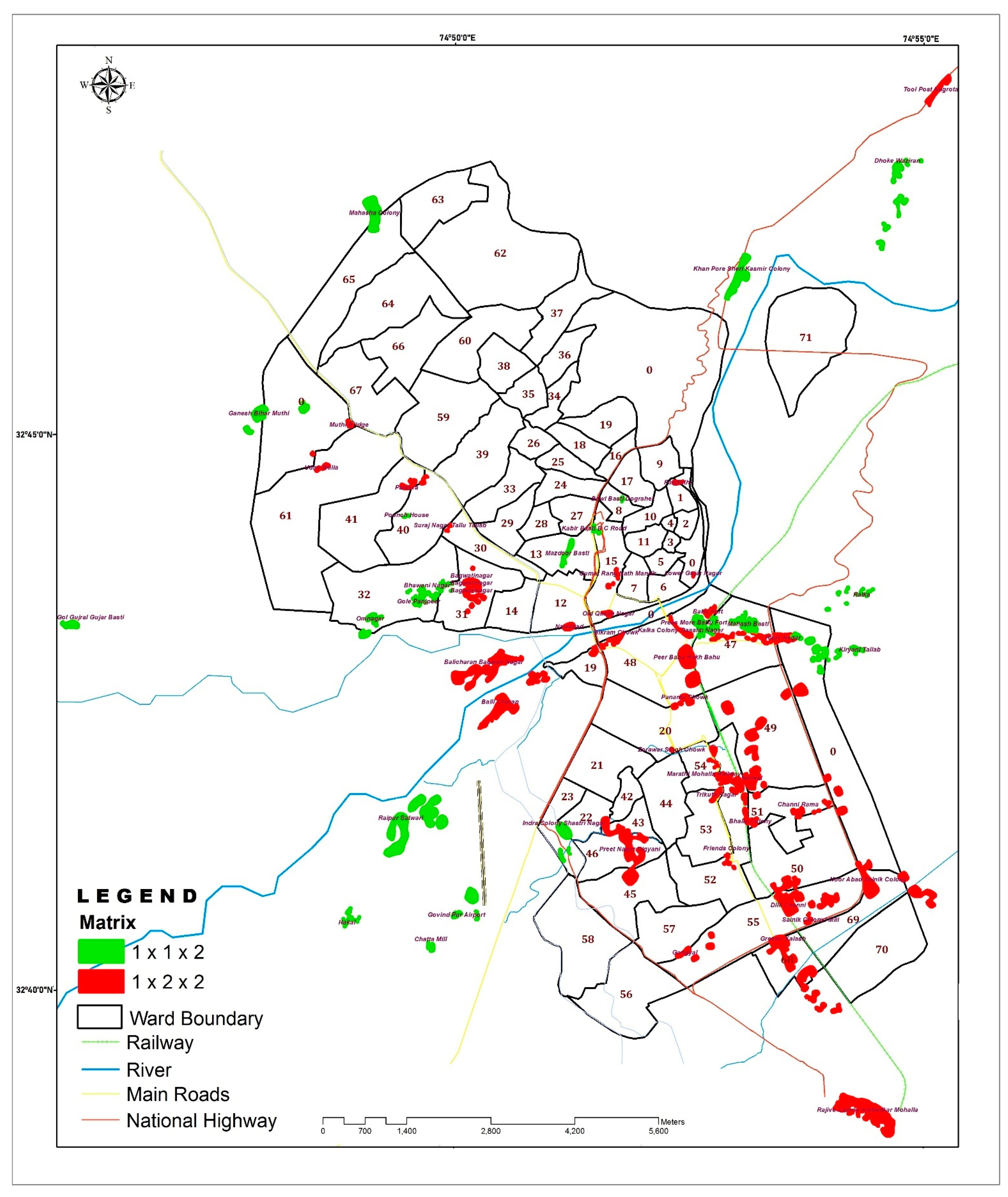

The dataset collected from the field survey (tenure status, tenability, ownership, dwelling density) was integrated into the Management Information System (MIS) in order to link with the GIS household points collected during the survey of Jammu’s slums for location, population, household size, and socio-economic profile. We considered infrastructure, tenure, and land value as key factors in developing the matrix. One of the most crucial aspects of the planning process is the tenure status of the slums, which is used to create a matrix.

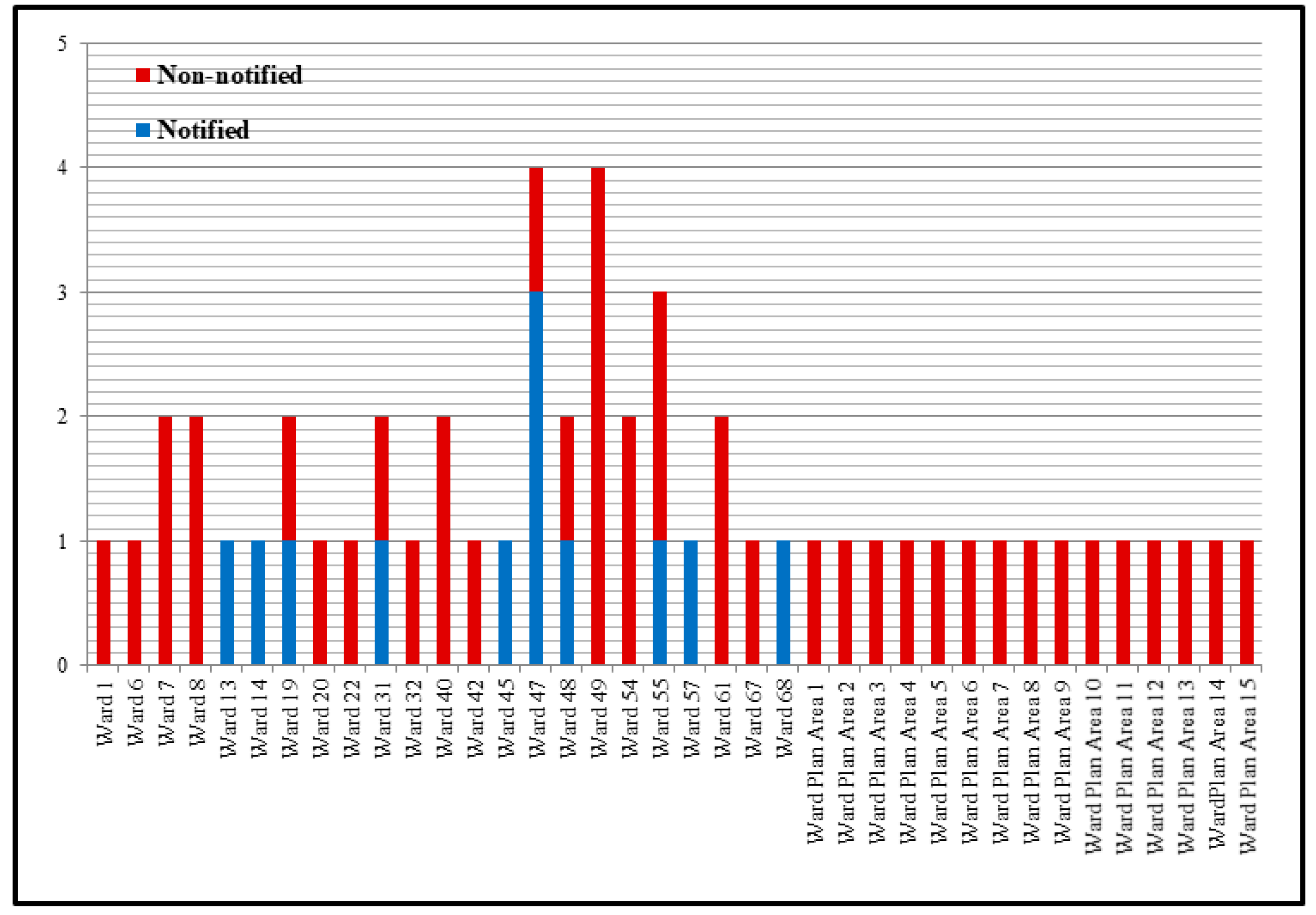

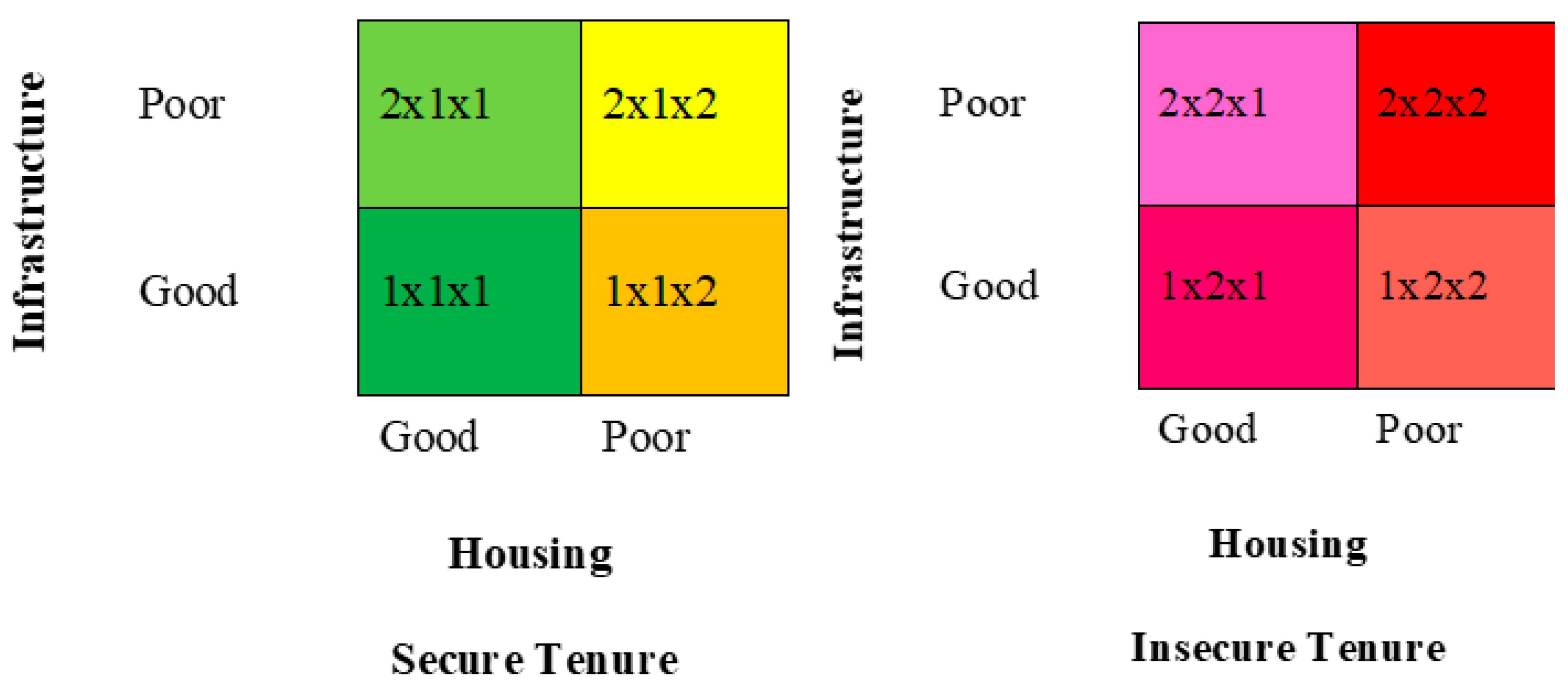

The slums that are not located on hazardous places and the land that is not planned for any important public infrastructure are suited for human habitation, hence it can be regularized in the same location as the official definition of “tenability” for slums under the Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY). Using objective and verifiable factors (land ownership, land use, spatial position, health risk, etc.), all extant slum communities were recognised and designated as Tenable or Non-Tenable, depending on their level of sustainability. A matrix for classifying slums according to RAY standards, with categories including “Infrastructure”, “Housing”, and “Tenure Status”, was developed to determine which areas are most in need of rapid improvement (

Table 1). Sustainable development planning, according to Naess (2001) [

49], necessitates integrating both specialised and generalised forms of knowledge. However, local residents’ experimental knowledge of environmental quality could make up for the lack of expert knowledge, and a shift in residents’ value priorities on development projects might be necessary for sustainable development. Keeping in view that the majority of community members did not have adequate education required to assign weightages, we conducted an exercise with community members to rank fundamental services/requirements in the order of importance and in their view and establish a consensus over the preference of identified solutions. An expanded method, as proposed in [

50], is needed to assign relative importance to the various dimensions of slum improvement from the perspective of locals. A priority weightage method proposed by Barron and Barrett (1996) has been widely used [

51]. The same approach was followed in our case as well, because it only asks participants to rank the listed objectives in their desired order. We subsequently calculated the average percentage based on those ranks, thus making the exercise accessible for the community. The most important attribute has the highest percent of priority weight, and the least important attribute has the lowest weight. The priority matrix (2 × 2 × 2) was used in this study for ranking the severity and prioritizing the slums into two classes i.e., high and low priority for intervention and as per the requirement of local government. The infrastructure metric considers factors such as the share of homes without running water, the share of homes with electricity, the share of homes with indoor plumbing, and the share of homes with toilets. The portion of households with unstable housing is included in the tenure section. In terms of housing, a higher percentage of Kutcha houses (houses made of mud and straw), as on priority weightage, are included than Semi–Pucca households (houses with fixed walls made of concrete material but roof made of hay). A total component score was calculated by summing the scores of each parameter, with each score representing the proportion of the above-mentioned components that are missing (

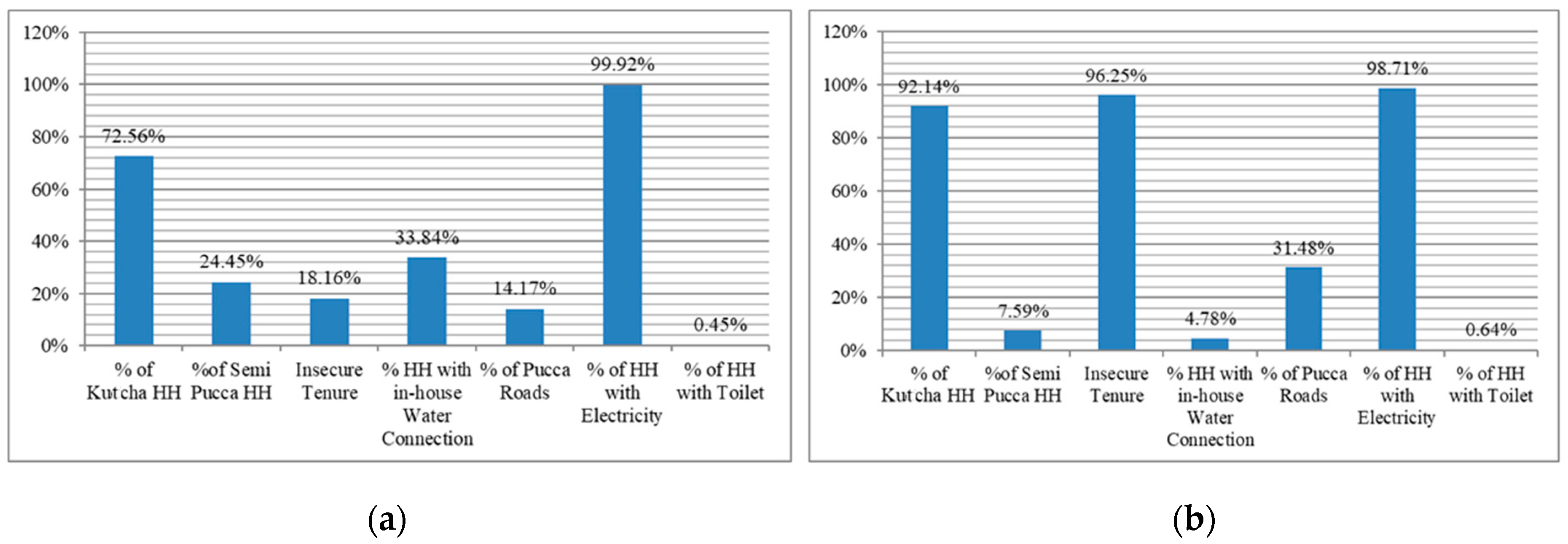

Table 2).

Table 1 details the seven criteria and three components that went into creating the 2 × 2 × 2 matrix. The ratings were calculated by giving each factor a certain weight based on what was learned from studies and community conversations.

4. Conclusions

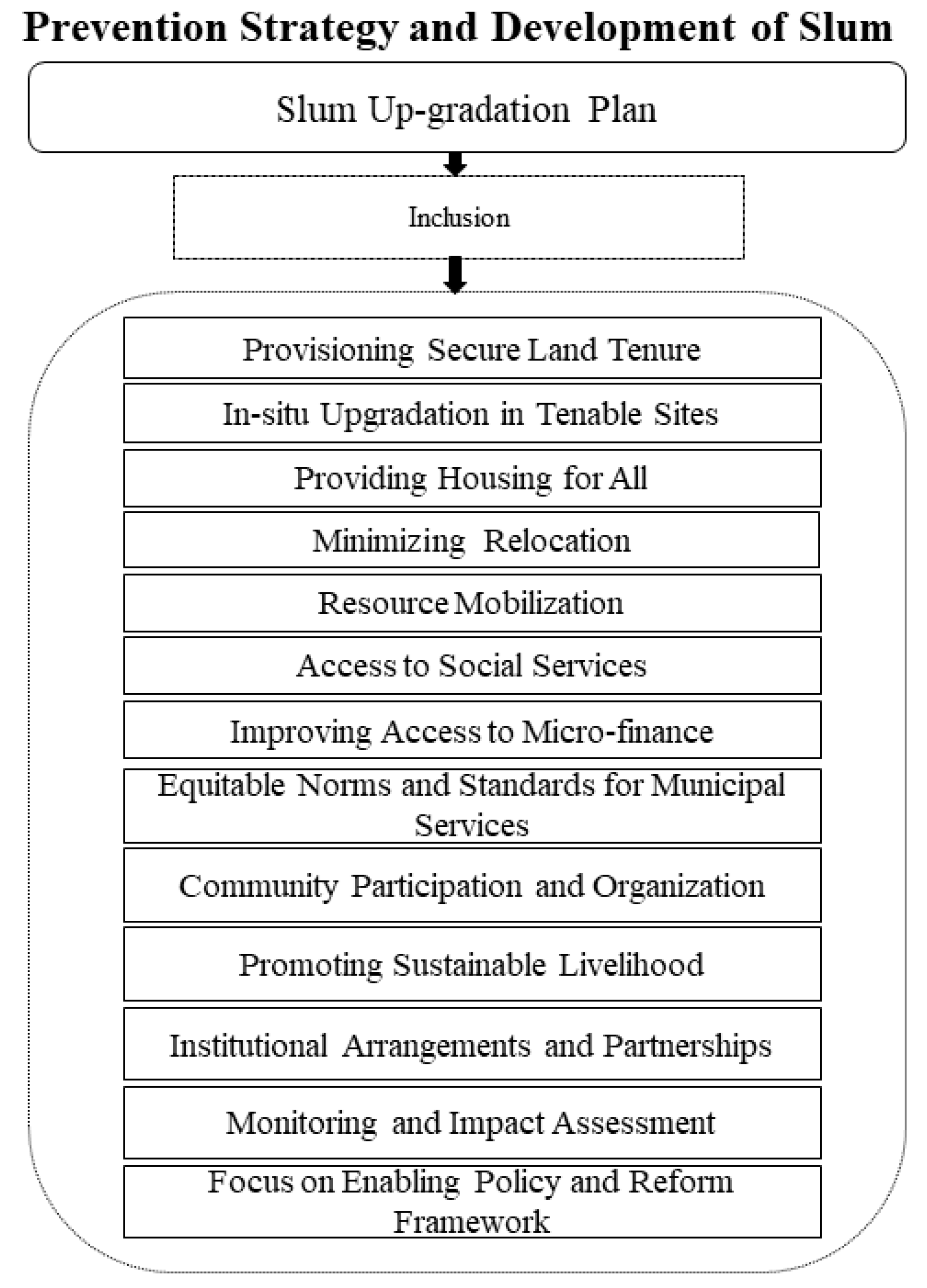

Jammu City, like many others in India, has been troubled by a housing shortage and the expansion of slums as a result of urbanization. Slum revitalization, being the primary low-cost housing alternative for the urban poor, necessitates a more in-depth diagnostic examination. The policy makers have been disconnected from the actual needs of the slum residents due to the lack of involvement of the direct stakeholders. Residents of slums have evolved to the sociocultural environment of slums, and any developmental endeavor that disrupts this environment could have a negative influence on their well-being. Individual tenure legalization is the first and best potential solution for a slum to be rehabilitated. Understanding the capabilities, options, and willingness of slum inhabitants is essential for effective slum redevelopment and urban environment management, as is the strong commitment of the administration to establish and maintain a conducive atmosphere. For slums to be successfully revitalized and improved in the future, their management strategy must take into account all viable options, regardless of how novel or unconventional they may be.

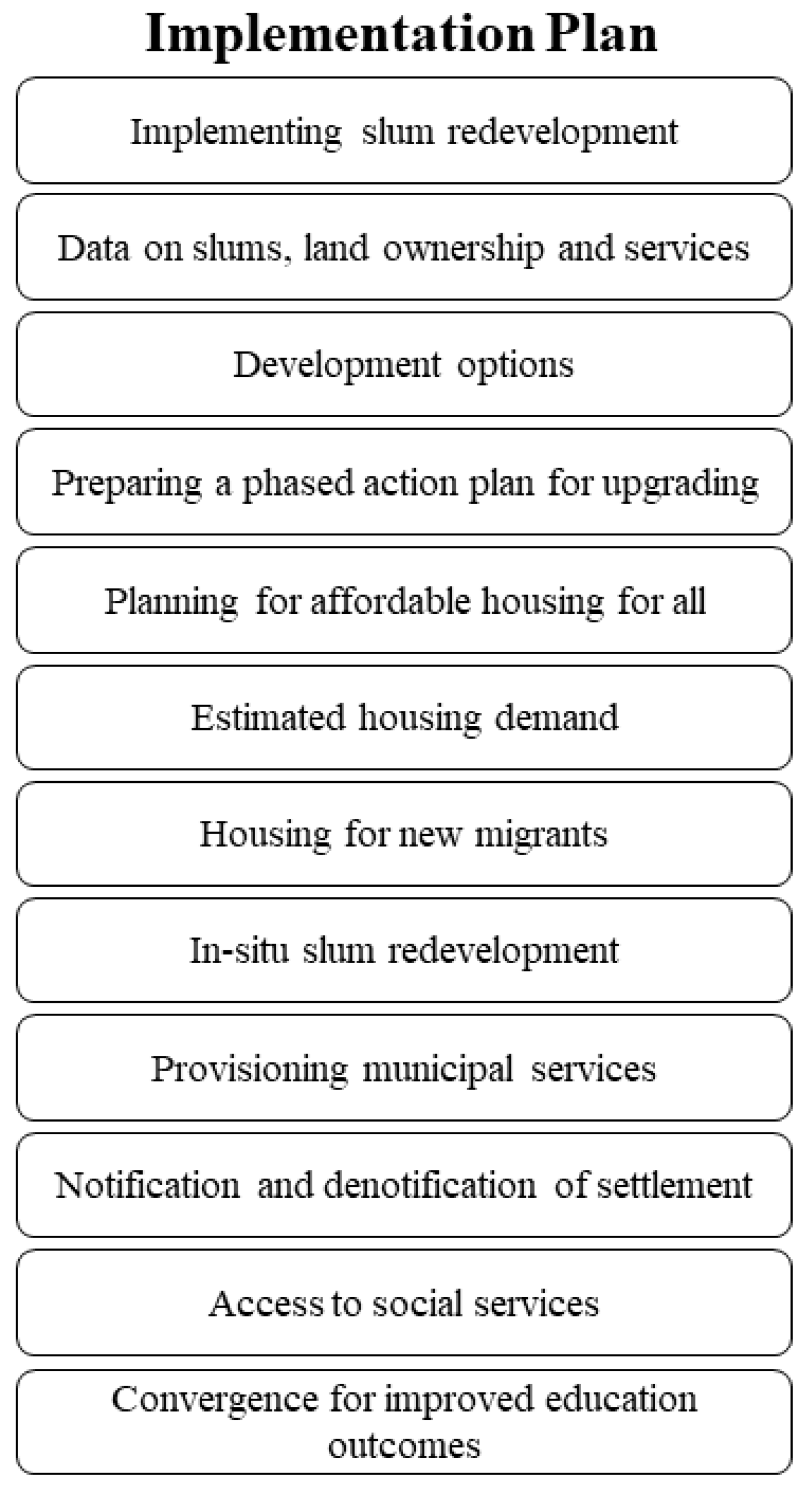

This paper presented a comprehensive framework for the selection of slum redevelopment and upgradation strategies. The main objectives of this system were to identify slum areas in Jammu City for the prioritization and formulation of a slum redevelopment plan. The framework consists of two main phases, including (1) framework structuring (generating input data) and (2) framework implementation (optimizing intervention priorities). Improvements to squatter areas should be carried out in accordance with a sensible plan, phased over a reasonable amount of time, and funded in an approachable manner. The steps of the implementation plan include: Community Participation, Promoting Sustainable Livelihoods, Estimated Housing demand for existing residents and new migrants, Affordable Housing for All, Provisioning of Municipal, Health, Educational, and Social services, Notification and De-notification of Settlements, and Community Based Monitoring. In addition, ecologically sensitive and environmentally hazardous sites should be considered untenable as habitation.

The foremost contribution of this research can be concluded in two main points. First, it recognized the most persistent problems surrounding slums based on current understanding. Second, it proposed the treatment to be given for uplifting the slum conditions, which is what policymakers are looking for. Although this study provides promising initial evidence on the informal settlements and their conditions in Jammu City, there is a lack of some important aspects which can be taken into consideration in future to overcome the limitations of this study. Rather than simply measuring the basic infrastructure and amenities, the analysis can be performed at a broader scale incorporating ladders that were recently proposed by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme to further differentiate between households on the basis of levels of service quality.