1. Introduction

As deep learning continues to penetrate an ever-wider array of applications—from image classification and natural language processing to autonomous systems and real-time analytics—hardware accelerators for deep neural networks (DNNs) have become a critical enabler of high-throughput, energy-efficient computation [

1,

2]. These accelerators often rely on large arrays of multiply-and-accumulate (MAC) units, designed to process the matrix and tensor operations that dominate modern DNN workloads. To maximize throughput, these MAC units are scheduled to operate in parallel across entire layers, often triggered in synchronized computing rounds.

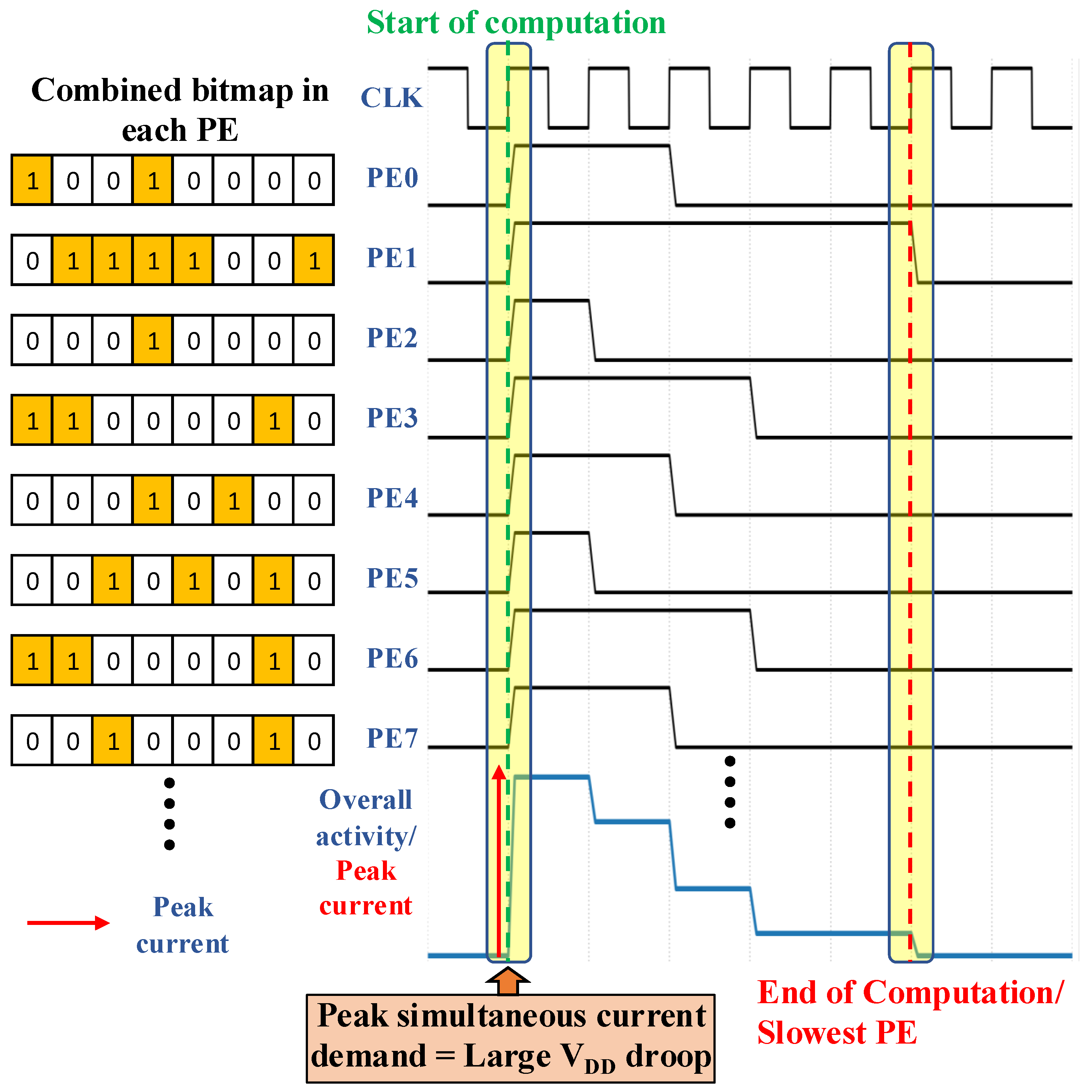

However, this parallelism introduces a fundamental challenge: as shown in

Figure 1a, the simultaneous switching activities of thousands of MACs lead to sharp increases in instantaneous current draw, also known as

transients, which in turn cause supply voltage (VDD) droop along the power delivery network (PDN) [

3,

4]. VDD droop is not merely an electrical nuisance—it is a major limiter of performance and reliability in modern hardware systems [

5]. If unaddressed, droop events can degrade timing margins, reduce operating frequencies, trigger protective throttling mechanisms, or lead to functional errors and computing failures in extreme cases [

4,

5]. Traditional techniques for dealing with this problem—such as increasing decoupling capacitance, enlarging voltage guardbands, or dynamically adjusting frequency/voltage—come at the cost of area, power, or throughput [

3,

6]. These methods are either reactive, kicking in after a droop is detected, or wasteful, guarding against worst-case behavior that may rarely occur [

6]. Furthermore, such solutions treat the workload as a black box and ignore the rich structural properties of DNN inference.

Crucially, modern DNN inference exhibits abundant sparsity in both weights and activations (from pruning, ReLU nonlinearities, and quantization) that production hardware already exploits to skip zero MACs for speed/energy [

7,

8,

9]. Yet, this extensive literature on “sparsity for acceleration” does not address the power delivery side: to our knowledge, no prior work leverages sparsity to actively shape instantaneous current and mitigate voltage droop. The distribution of zeros varies across processing elements (PEs), creating natural imbalance; when all PEs launch simultaneously, the dense-workload subset dominates round length and concentrates switching activity—precisely the pattern that produces the

spike and the accompanying VDD dip in

Figure 1a. In this paper, we propose

SparseDroop, which leverages sparsity to proactively reduce peak current while preserving sustained throughput. It combines SparseStagger—using inherent unstructured zeros to phase-offset PE launches and smooth

—and SparseBlock—introducing block-structured zeros aligned to access granularity to cap simultaneous PE activity. Together, these mechanisms repurpose sparsity from acceleration to a droop-mitigation lever. An overview of the proposed

SparseDroop technique is demonstrated in

Figure 1b. A point to note here is that, in this work, we specifically focus on ASIC-class deep learning accelerators rather than on FPGA-based implementations. The droop mechanisms studied here are derived from cycle-aligned MAC-array concurrency, a behavior characteristic of ASIC fabrics but not faithfully reproducible on commercial FPGA platforms.

We first instantiate the idea with SparseStagger, the scheduling mechanism within SparseDroop. SparseStagger uses the same nonzero bitmap metadata already present for zero-skipping to directly observe the actual weight and activation sparsity for the upcoming computing window. Using this exact information, it staggers PE within each local group so that lighter workloads launch first and denser ones are initiated slightly later, creating an interleaved wave of MAC activity. Because only the launch order is changed—and all mapped work is still executed—sustained throughput is preserved while the instantaneous current is flattened, reducing droop incidence and depth. The policy is localized and lightweight, deriving offsets from existing sparsity metadata; requires no new data formats or cross-group coordination; and preserves the current dataflow and compressed fetches. Functionally, SparseStagger converts a single simultaneous surge into tightly interleaved waves, reducing the amplitude of excursions that stress the PDN; unlike merely skipping zero MACs, it reschedules when toggling occurs, thereby mitigating VDD droop without performance loss.

To amplify the scheduler’s headroom, SparseDroop integrates SparseBlock, a block-wise structured sparsity induction technique that intentionally introduces additional sparsity to cap the number of concurrently active MACs. Unlike conventional unstructured or rigid structured sparsity schemes, SparseBlock partitions the weight tensor into 2D blocks along the input channel and output channel axes—each block mapping directly to a column of processing elements (PEs). By pruning entire blocks based on a combination of magnitude and architectural alignment, SparseBlock reduces the likelihood that all PEs in a column are simultaneously active during a computing round. This significantly smooths spatial activation patterns, spreading computation across time and reducing the incidence of high instantaneous current draw (). Beyond computing efficiency, SparseBlock plays a critical role in power delivery management by synergizing with the droop-aware scheduler. With fewer active MACs per column and a more predictable sparsity structure, the scheduler can more effectively stagger PE start times to further flatten current transients. To preserve accuracy, we apply lightweight post-pruning fine-tuning; moreover, practitioners may adopt full retraining with a droop-aware sparsity objective (e.g., a proxy for peak current) to co-optimize accuracy and PDN stress—an angle, to our knowledge, not previously explored for voltage-droop mitigation. This coordinated approach—combining architecture-aware sparsity shaping with real-time workload-aware scheduling—makes SparseDroop the first framework to jointly optimize for voltage-droop mitigation, energy efficiency, and throughput preservation.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose SparseStagger, a lightweight hardware-friendly scheduler that dynamically staggers MAC start times based on the inherent unstructured sparsity present in weights and activations. This reduces peak current demand () without affecting the overall throughput of the accelerator.

We design SparseBlock, a block-wise pruning method that introduces additional structured weight sparsity patterns in alignment with the accelerator’s compute dataflow, minimizing simultaneous activation across PE columns and improving current distribution.

To the best of our knowledge, SparseDroop, comprising both SparseStagger and SparseBlock, is the first framework to co-optimize compute scheduling and sparsity structure to mitigate VDD droop in edge accelerators, while preserving the latency and accuracy of DNN inference.

Our method operates entirely at runtime without requiring changes to software scheduling or compiler data layouts. The scheduler is localized and scalable across multiple PE columns without global coordination.

Experimental results across representative sparsity scenarios show that SparseDroop reduces simultaneous current demand by 53–73% in over 60% of computing rounds, with negligible impact on accuracy or throughput.

2. Related Work

2.1. Voltage Droop Mitigation in Accelerators

Modern DNN accelerators often face supply voltage (VDD) droop issues due to the simultaneous switching of large arrays of MAC units, which causes sharp transient current surges on the power delivery network (PDN) [

10]. Conventional hardware techniques mitigate VDD droop through the use of conservative guardbands [

11], either by operating VDD above the minimum voltage (VMIN) or by lowering clock frequency (FCLK) below its maximum limit (FMAX) to ensure timing safety during droop events. However, such static margins result in wasted energy and performance headroom under nominal conditions [

12,

13]. One class of state-of-the-art approaches targets transient smoothing by staggering the activation of functional units [

5]. In the context of DNN accelerators, this entails delaying the start of MAC operations across processing elements (PEs) or their internal compute units by fixed intervals (

) to reduce peak current demand. While this staggered execution effectively spreads out current draw, it is typically blind to input data patterns or workload sparsity, often delaying the overall computation and adversely impacting throughput. Since DNN accelerators operate under the constraint that the slowest PE dictates the computing latency, data-agnostic staggering can cause slower PEs to extend total computing time beyond the baseline, lowering performance despite droop mitigation [

8].

Beyond staggered scheduling, several adaptive circuit-level techniques have been developed to manage voltage droops. These include real-time VDD monitoring with adaptive FCLK scaling [

14], analog phase-locked loop (PLL) modulation, and tunable delay-based digital clock adaptation [

15]. While these methods provide moderate droop suppression, they often struggle with fast transients due to inherent control loop delays or analog stability issues. Hybrid control loops combining VDD and FCLK in unified feedback systems offer tighter compensation but face practical challenges in regulator design. Additionally, timing-error detection and correction techniques have been proposed that isolate and recover from timing violations without architectural state corruption [

16]. Although effective at high frequencies, their complexity and recovery latency make them difficult to scale across large DNN workloads [

17]. Proactive methods that attempt to predict VDD droops in advance based on code signatures or control flow behaviors have been proposed in general-purpose vector processors. For instance, a Proactive Clock-Gating System (PCGS) unit modulates clock-gating signals to reduce droop magnitude [

18]. However, in the domain of DNN accelerators, there is little prior research that considers input sparsity or workload structure to anticipate and prevent droop. SparseStagger addresses this gap by scheduling MACs based on actual compute density derived from weight and activation sparsity—something that traditional staggering and adaptive schemes do not exploit.

2.2. Sparsity-Driven Acceleration

To reduce computational overhead in DNNs, significant research has focused on pruning techniques that eliminate redundant parameters [

19,

20]. In unstructured sparsity schemes, weights are zeroed out without regard to position, often resulting in high sparsity ratios and minimal accuracy loss. However, these random sparsity patterns lead to irregular memory access and poor data reuse, making them difficult to exploit efficiently in hardware [

21]. To overcome this, structured sparsity approaches impose regularity—such as pruning entire channels or enforcing block patterns. Notably, NVIDIA’s 2:4 sparsity pattern enforces two zeros per four contiguous weights to simplify decoding and compute skipping in hardware [

22]. While structured pruning eases implementation, it tends to limit the achievable sparsity and requires careful retraining to preserve accuracy—particularly for non-over-parameterized networks [

23].

While these pruning methods reduce computational cost, they are typically agnostic regarding the underlying hardware’s dataflow, leading to missed opportunities for maximizing power efficiency [

24]. Furthermore, existing research does not consider the role of structured sparsity in managing power delivery challenges such as VDD droop [

25]. SparseBlock, as introduced in this work, addresses this limitation by inducing architecture-aligned block sparsity over the IC-OC axes of the accelerator. This method enhances both sparsity exploitation and power-aware execution. By tailoring sparsity to align with the PE array layout, SparseBlock ensures predictable current behavior and complements the scheduling strategy of

SparseDroop—achieving both performance and voltage stability goals.

3. Background and Motivation

3.1. DNN Accelerator Architecture

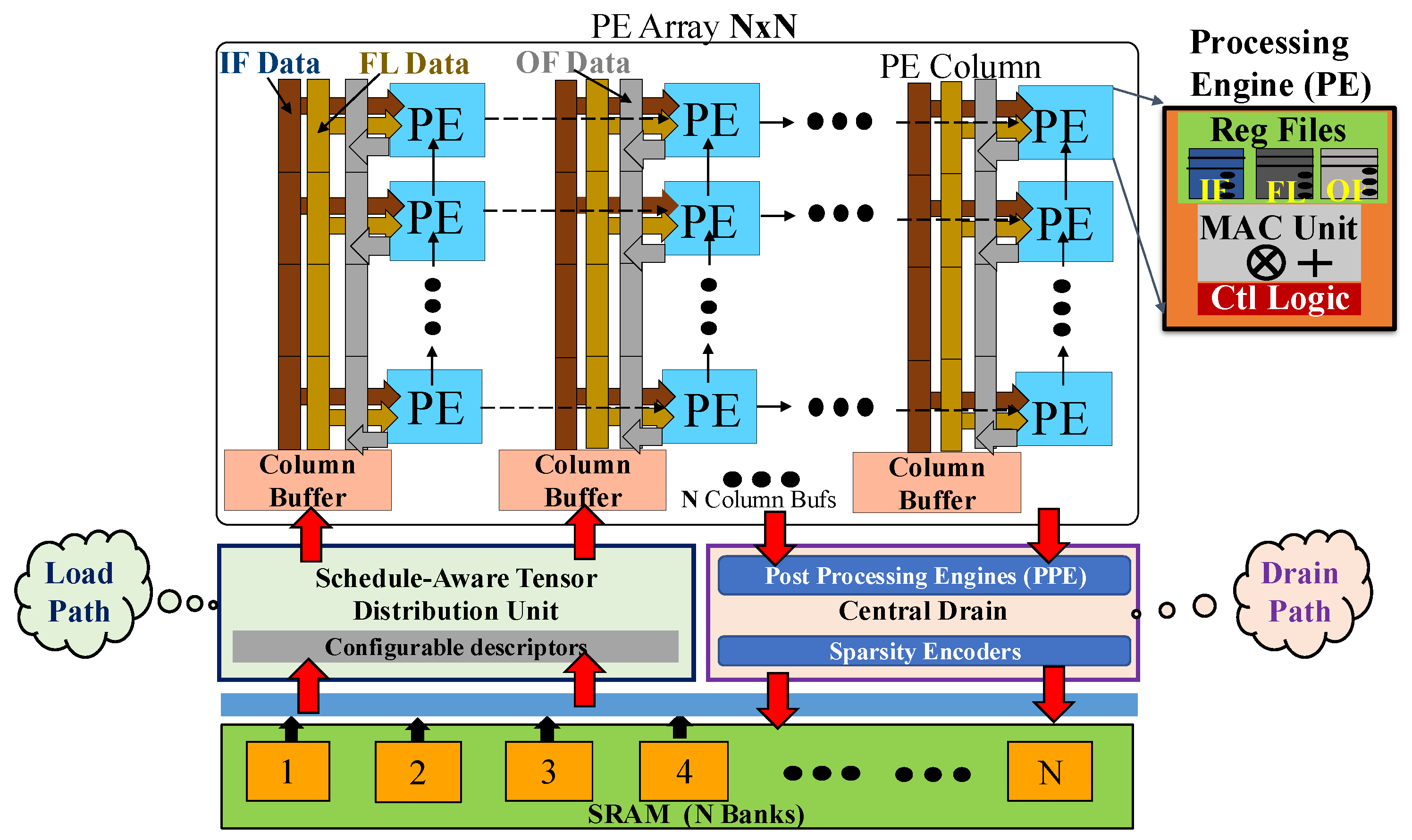

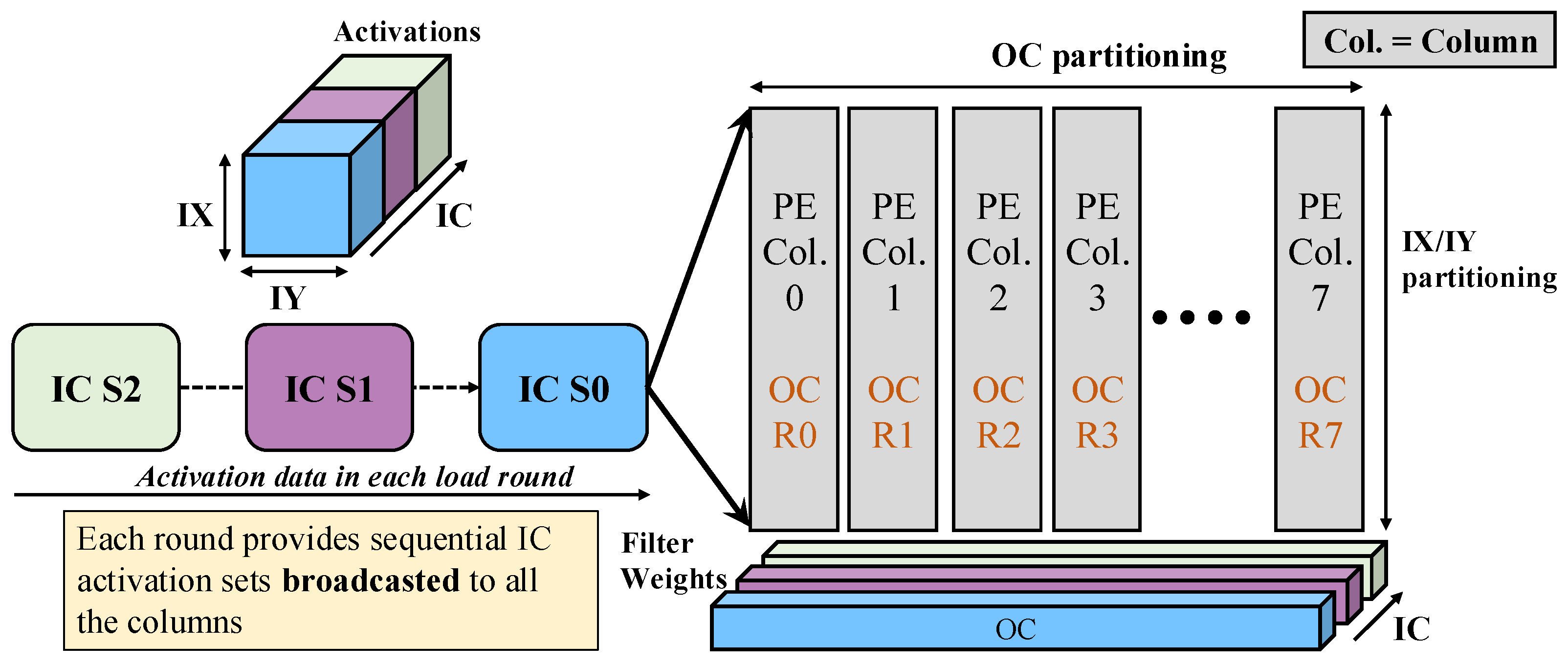

Deep neural network (DNN) accelerators are designed to efficiently process the massive computational workloads of modern machine learning models, especially during inference. A representative DNN accelerator is shown in

Figure 2. The core of such an accelerator is typically a two-dimensional grid or array of processing elements (PEs), often further organized hierarchically into columns to enable scalable data movement and computing parallelism [

8]. This columnar hierarchy helps distribute memory bandwidth and output reduction across the grid, thereby supporting higher frequencies and larger arrays.

Each PE contains local register files for input features (IFs), filter weights (FLs), and output feature maps (OFs), and performs one or more multiply-and-accumulate (MAC) operations in every computing round. The MAC operation typically performs accumulation across the input channel (IC) dimension, with IC sets streamed sequentially from the local RFs. In each computing round, the PEs load a new IC set and perform partial sums, which are eventually accumulated over multiple rounds to produce the final OF point. The MACs, thus, perform convolution over tiled IC sets, with intermediate results stored in the OF RFs.

To facilitate this computation, the accelerator includes load and drain units. The load unit fetches compressed weight and activation tiles from SRAM or intermediate data stores (shown in

Figure 3) and distributes them across PEs. The drain unit post-processes the outputs and writes the results back to memory. Activations are broadcast across PE columns, while weights for a given output channel (OC) are broadcast within each column. The broadcasted IC-OC weight tiles and activation slices define the block-level granularity of computing and memory transfer in the system.

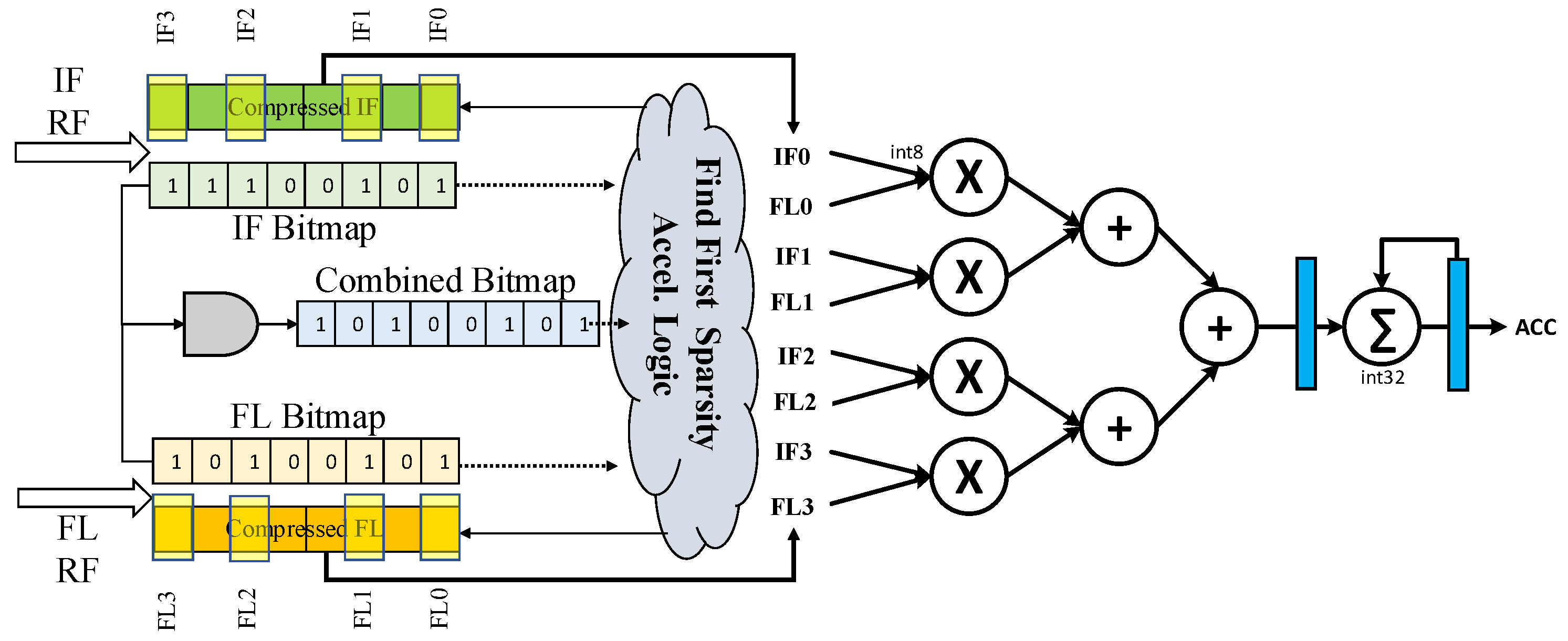

3.2. Sparsity Acceleration in MAC Units

Modern DNNs exhibit high sparsity in weights and activations—either due to training-time pruning, ReLU nonlinearities, or quantization. Accelerators exploit this sparsity via sparsity acceleration: MACs involving zeros are skipped, improving both performance and energy [

7,

8,

9,

19]. Practically, this relies on compressed formats with sparsity bitmaps indicating nonzero locations. As shown in

Figure 3, bitmap logic identifies valid MAC pairs: a bitwise AND of the IF and FL maps marks operand pairs that must be computed, and the population count of the combined bitmap equals the number of useful MACs in a computing round. In sparsity-aware designs, each PE is active only for as long as needed to accumulate its nonzero partial sums, and that active time varies with local sparsity.

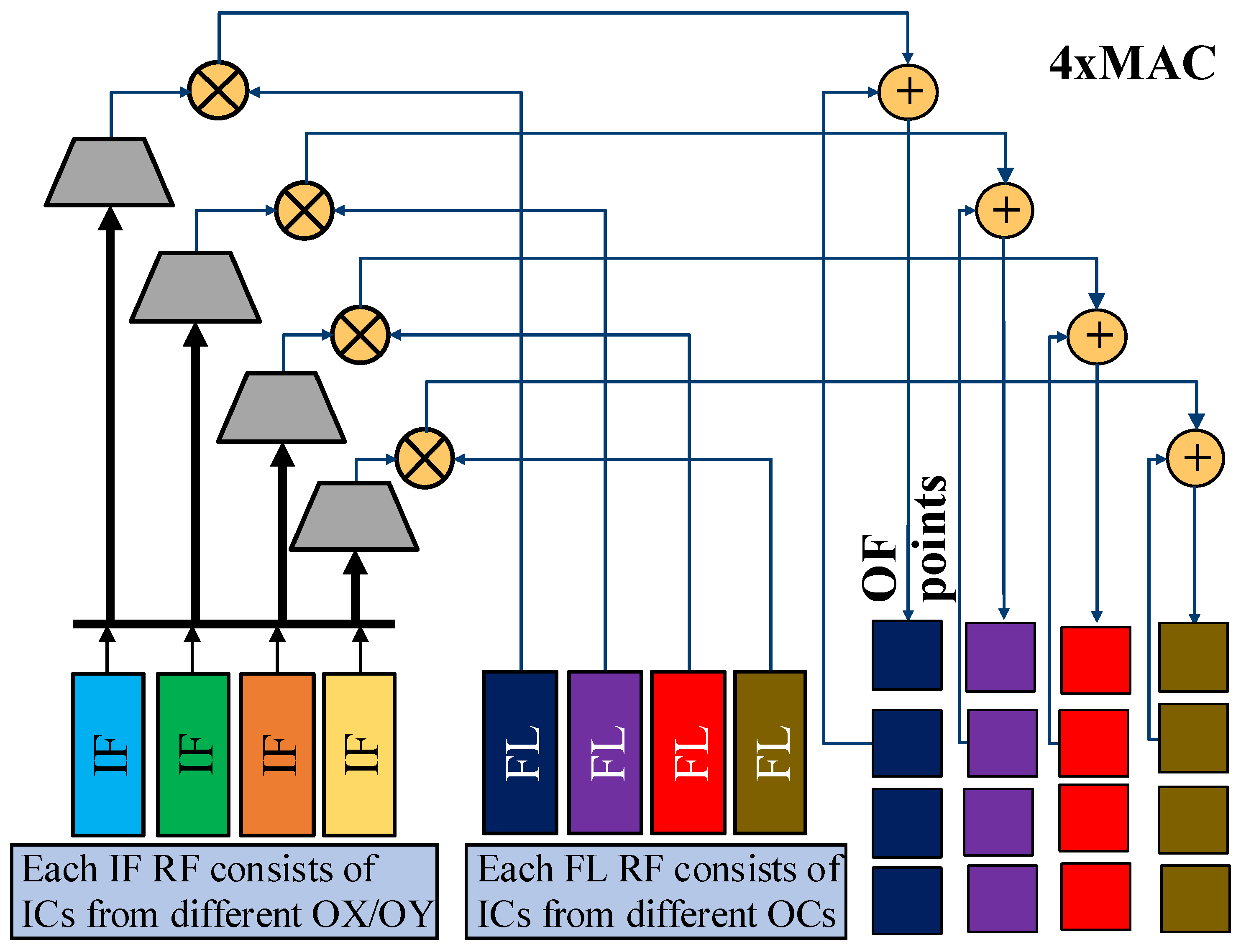

Alternative datapaths, such as

Figure 4, instantiate multiple multipliers per PE with an adder tree, fetching several IF/FL pairs per cycle while multi-bit sparsity logic selects valid groups. Some designs further deploy multiple MACs per PE (

Figure 5) using separate IF/FL banks to serve different output contexts in parallel; banks are multiplexed to feed concurrent MAC units. A “context” denotes a unique accumulation window (i.e., a specific set of indices over which partial sums are formed). Regardless of the datapath, the sparsity pattern governs the per-PE active duration and, thus, its instantaneous current draw during a round. To make this implication concrete under a conventional simultaneous-start schedule, consider the following multi-PE example.

An example of the combined sparsity across multiple PEs, where eight input channels (ICs) are processed per computing round, is shown in

Figure 6. In a baseline DNN accelerator design, computation begins simultaneously for all PEs once the required activation (IF) and weight (FL) data for a single context are fully loaded into the corresponding register files. The compute engine operates in a streaming fashion where execution begins immediately and continues uninterrupted until the round completes. The total computing latency is dictated by the slowest PE—in this case,

—since it must perform the most multiply–accumulate (MAC) operations due to its denser workload. In all subsequent waveform plots, a high signal indicates that a PE is actively performing computation. The simultaneous enabling of all PEs leads to a substantial instantaneous current draw, introducing a transient droop in the VDD rail. This voltage dip can violate timing constraints and degrade system performance, or in worst cases cause functional errors—a phenomenon that becomes a critical bottleneck as temporal and spatial activity increase in deep networks.

3.3. Motivation for IC-OC Block-Level Sparsity

As shown in

Figure 7, the distribution of weights and activations across PEs follows a predictable structure: input channels (ICs) are streamed sequentially within a PE, while output channels (OCs) are distributed across PE columns. Each computing round operates over a specific IC set (e.g., S0, S1, S2) for a given spatial activation position (IX/IY), and each column works on a different OC tile (R0, R1, R2). Because weights are broadcasted per OC and activated per IC, each compute tile forms a distinct IC-OC block that maps to a physical unit of workload in the system. This structure presents an opportunity to induce sparsity in a hardware-aligned manner: by pruning weights at the IC-OC block level (rather than at fine or random granularity), one can skip entire blocks of computation and memory fetches. For instance, if the entire S1-R1 block contains zeros, we can skip loading both the corresponding weights and activations—saving energy and avoiding unnecessary MAC switching.

If sparsity were induced at a finer granularity (e.g., per weight), we might still require full activations to be broadcasted to the column, even if only a few weights are nonzero. This limits the ability to skip memory fetches and reduces the effectiveness of compute skipping. Coarse-grained, architecture-aligned sparsity enables greater computing and memory efficiency by ensuring that entire RF tiles or broadcast paths can be gated off. The proposed SparseBlock technique exploits this idea by inducing sparsity at the IC-OC block level, followed by a fine-tuning step. By aligning sparsity with the computing and dataflow granularity of the accelerator, SparseBlock maximizes the benefit of each pruned element. Furthermore, this structured sparsity reduces the probability of simultaneous PE activation across a column, enabling the SparseDroop scheduler to more effectively stagger execution and reduce peak current draw. These components create a robust, scalable, and hardware-friendly solution to mitigate VDD droop while improving energy and throughput efficiency.

4. Results

We now present experimental results for the two main components of our framework: SparseStagger and SparseBlock. SparseStagger is evaluated in terms of its ability to reduce peak simultaneous current demand and thereby mitigate VDD droop across a wide range of sparsity scenarios. SparseBlock is evaluated for its impact on inference accuracy as well as its computing and memory efficiency when applied to representative ImageNet classification models. Together, these results demonstrate how sparsity-aware scheduling and architecture-aligned pruning jointly enable robust voltage stability and efficient execution in modern DNN accelerators.

4.1. SparseStagger Evaluation

Figure 8 shows the distribution of normalized reduction in simultaneous current demand achieved by the down-counter PE scheduler under different sparsity conditions. For randomized sparsity (

Figure 8a), more than half of the computing rounds achieve a 53–63% reduction. When both weights and activations are at 25% density (

Figure 8b), most rounds fall in the 39–52% or 52–65% ranges. For balanced 50% density in both weights and activations (

Figure 8c), 62.6% of rounds achieve a 61–73% reduction. Even in the low-sparsity case of 75% density (

Figure 8d), 64.9% of rounds still reduce peak simultaneous activity by 59–69%. These results confirm that SparseStagger consistently flattens peak current demand without impacting throughput, providing effective VDD-droop mitigation across a wide range of sparsity scenarios.

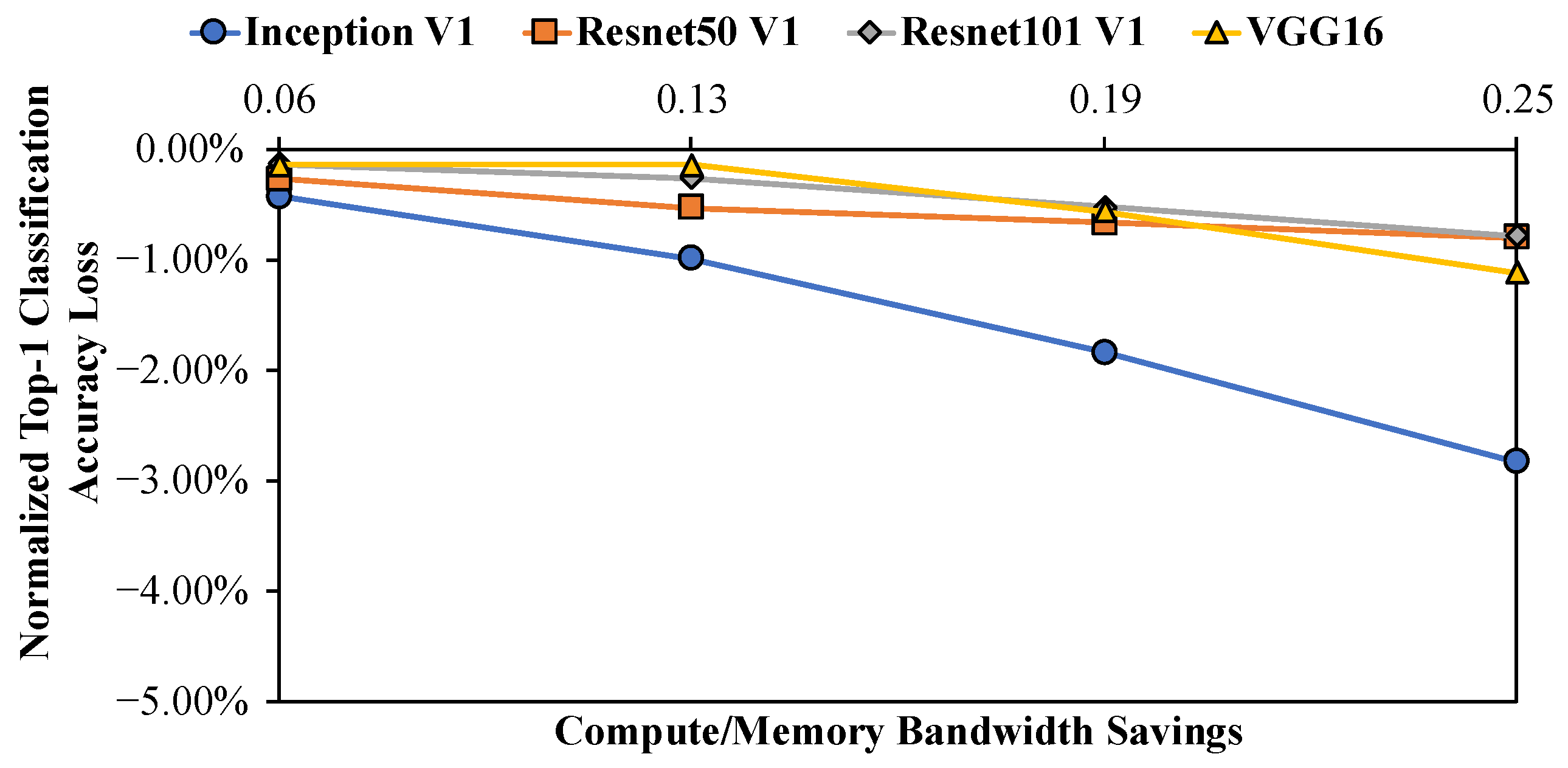

4.2. SparseBlock Evaluation

Table 1 reports the top-1 ImageNet classification accuracy of SparseBlock for ResNet50v1.5, ResNet101, VGG16, and Inception v1 under varying sparsity ratios. As expected, increasing the pruning ratio

R leads to higher weight sparsity but also greater accuracy degradation. For ResNet50/101 and VGG16, the accuracy drop remains below

even at

(

of IC8 blocks pruned). Inception v1 is more sensitive to pruning, but still maintains a less than

accuracy loss of up to

. These results indicate that SparseBlock can induce structured hardware-aligned sparsity while preserving accuracy across multiple architectures.

From a hardware perspective, pruning IC8-OC blocks directly translates into proportional reductions in computing and memory activity. For instance,

yields a

reduction in DMA fetches and MAC operations, since entire IC8 blocks are eliminated rather than scattered individual weights. This coarse-grained skipping avoids irregular access patterns and enables predictable efficiency improvements in both memory bandwidth and computing energy. As shown in

Figure 9, the top-1 accuracy loss across all networks scales inversely with the achieved computing/memory savings, confirming that SparseBlock provides linear efficiency gains while maintaining accuracy within acceptable bounds. These results demonstrate that SparseBlock achieves accuracy-preserving structured sparsity aligned with accelerator dataflow.

5. Discussion

The results presented in

Section 4 demonstrate that both SparseStagger and SparseBlock address key challenges in deploying sparse DNN workloads on modern accelerators. SparseStagger consistently reduced peak simultaneous current demand across a wide range of sparsity scenarios without incurring throughput penalties. This behavior contrasts with prior approaches such as blind staggered execution [

26] or reactive adaptive clocking [

18], which either degrade performance or rely on complex monitoring infrastructure. By leveraging sparsity patterns already exposed during computation, SparseStagger achieves proactive droop mitigation in a lightweight manner.

A point to note here is that, we focus primarily on positive-switching surges because these events produce the dominant L·di/dt droop in modern accelerators. In contrast, negative-going current transitions are naturally limited by datapath settling behavior and are significantly smaller in practice. Empirical PDN studies consistently show much lower voltage disturbance from disable events, and internal pipeline structure causes PEs to retire over several cycles rather than in one abrupt boundary. As a result, SparseStagger does not introduce any harmful supply voltage undershoot at round completion.

SparseBlock complements this by introducing hardware-aligned block sparsity that preserves accuracy while reducing computing and memory activity in proportion to the pruning ratio. Compared to unstructured pruning methods [

20] that often yield irregular access patterns and high metadata overhead, SparseBlock induces coarse-grained sparsity aligned with IC-OC dataflow, ensuring predictable bandwidth savings and efficient PE utilization. The observed <1% accuracy drop at

for most models highlights its practicality for real-world deployment, especially when combined with lightweight fine-tuning.

Together, SparseDroop supports the working hypothesis that sparsity can be exploited not only for computing and memory reduction but also as a system-level lever for power delivery stability. This dual role of sparsity has received limited attention in prior studies, which primarily treated sparsity as a means of reducing arithmetic complexity. By integrating a droop-aware scheduler with block-level pruning, the framework demonstrates that sparsity can directly alleviate electrical constraints in addition to computational ones.

The implications extend beyond the specific models and accelerators studied here. SparseStagger’s scheduling mechanism is broadly applicable to accelerators with columnar PE hierarchies, and SparseBlock’s structured sparsity can be adapted to other memory layouts by redefining block granularity. Future research could explore applying these techniques to transformer-based models, where activation sparsity is less predictable, or to mixed-precision accelerators where dataflow and power delivery dynamics differ. Another promising direction is co-optimizing sparsity induction with dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS), enabling joint control of workload balance and supply margins.

In summary, the proposed methods demonstrate how sparsity-aware design can unify accuracy preservation, efficiency, and voltage stability. These findings highlight the importance of viewing sparsity not only as a computational optimization but also as a cross-layer tool for improving the robustness of next-generation DNN accelerators.

5.1. Correlation with Next-Generation NPU Silicon

SparseDroop targets ASIC-class DNN accelerators whose PE arrays operate in tightly synchronized computing rounds that produce sharp ICC surges. Commercial FPGA platforms, however, include multi-stage voltage regulation, large on-board decoupling networks, and low-bandwidth current sensors, all of which suppress or mask transient VDD behavior. Moreover, FPGA DSP blocks cannot be forced into cycle-aligned switching as in ASIC MAC arrays, making FPGA measurements unrepresentative of the droop phenomena we study. For this reason, FPGA-based validation does not faithfully reflect SparseDroop’s mechanism of action, and we instead rely on cycle-accurate architectural modeling.

Although FPGA testing is not representative, a scheduling mechanism conceptually similar to SparseStagger has been implemented and evaluated on FlexNPU-v2, Intel’s experimental next-generation NPU chip [

8]. We supplied FlexNPU-v2 with the same activity traces used in our simulations, and the resulting peak current reduction trends correlated closely with those predicted by SparseDroop. Full FlexNPU-v2 silicon results will be published separately, but the observed correlation provides additional confidence in SparseDroop’s practical applicability.

5.2. Overhead and Integration Considerations

The hardware overhead introduced by SparseDroop is extremely low. SparseStagger adds only a small amount of control logic—primarily a lightweight down counter, a simple comparator per PE or MAC unit, and minor FSM extensions. These elements are negligible compared to the area and timing footprint of the MAC datapath and register files, and they do not modify the accelerator’s dataflow, tensor layouts, or pipeline depth. Consequently, SparseStagger does not impact the critical path or throughput. SparseBlock is applied entirely offline during pruning and, therefore, incurs no runtime overhead. At inference time, it requires only a block-level sparsity mask lookup, without additional metadata handling or control complexity. Given the localized nature of these additions, the overall area, timing, and verification overhead of integrating SparseDroop into a modern DNN accelerator is expected to be extremely small.

6. Methodology

This section details the architectural and algorithmic components of SparseDroop, a runtime framework that mitigates VDD droop in DNN accelerators by leveraging workload sparsity. SparseDroop comprises two main innovations. First, SparseStagger, a PE computation scheduler dynamically staggers the execution of processing elements (PEs) based on the workload’s sparsity to smooth transient current demand. Second, the SparseBlock method induces structured IC-OC block-level sparsity to maximize the impact of sparsity on power delivery and execution efficiency. Together, they form a unified system that reduces peak current without sacrificing throughput or model accuracy.

6.1. SparseStagger: PE Computation Scheduler for Droop Mitigation

6.1.1. Synchronous Execution and the Case for Staggered Scheduling

Under a conventional simultaneous-start schedule, once IF/FL data for a context are loaded, all PEs fire together and run uninterrupted; the round’s latency is set by the slowest (densest-workload) PE. This lockstep enablement concentrates current, producing sharp peaks and transient VDD droops that can violate timing and degrade—or even corrupt—computation. While occasional events may be tolerable, repeated peaks across deep networks become a system-level bottleneck as temporal and spatial activity increase.

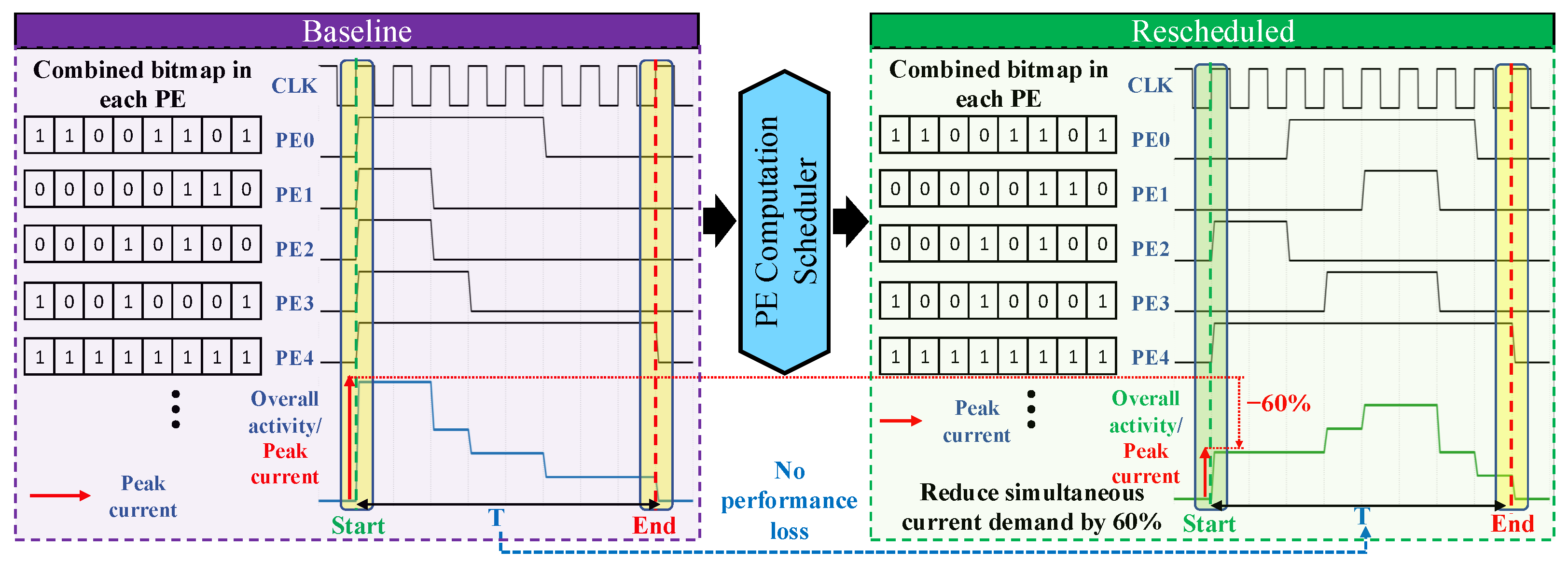

To address this challenge, SparseDroop introduces a novel approach, SparseStagger, that mitigates VDD droop without sacrificing inference throughput. A key insight behind SparseStagger is that the PE with the heaviest workload determines the overall computing latency. Therefore, delaying the start of other PEs—those with lighter sparsity-induced workloads—can substantially reduce the number of concurrently active compute elements, lowering peak current draw without increasing total round latency.

Figure 10 illustrates this approach:

, which has the highest PopCount (i.e., MAC workload), starts executing immediately. All other PEs (

–

), which have fewer active computations, are delayed such that their execution completes precisely when

finishes. This fine-grained, context-aware rescheduling of PE start times reduces concurrent switching activity and lowers peak current consumption. In this illustrative case, SparseStagger reduces the number of PEs activated simultaneously by 60% with no impact on inference throughput. This observation forms the foundational design principle behind the staggered PE scheduling mechanism introduced in the following subsections. By exploiting naturally occurring sparsity imbalance across PEs, the scheduler dynamically reorders computation to reduce power delivery stress without impacting latency—offering a scalable low-overhead solution to droop mitigation.

6.1.2. Architecture and Implementation of the Down-Counter PE Scheduler

To enable droop-aware execution without throughput loss,

SparseDroop introduces a lightweight column-level scheduling framework, SparseStagger, that dynamically staggers PE execution based on combined sparsity patterns. A block-level overview of the proposed PE computation scheduler is shown in

Figure 11. Each processing element (PE) is associated with a Sparsity Calculator that computes the number of useful MAC operations it must perform in a given computing round. This is achieved via a bitwise AND operation between the sparsity bitmaps of the weight (FL) and activation (IF) register files. The result—a per-PE population count (PopCount)—reflects the true workload of that PE for the round. These PopCount values are then fed into a centralized scheduler that operates at the column level. The rationale for column-level visibility is rooted in typical DNN accelerator architectures, where weights and activations are broadcasted or multicasted across multiple columns to improve data reuse and power efficiency. As such, simultaneous computation starts across a column is common. Scheduling within columns avoids latency overhead and the wiring complexity of global coordination while still significantly mitigating localized VDD droop. In more uncommon configurations where weights or activations are unicasted to individual columns, coordination across column-level schedulers can further enhance droop resilience through inter-column sparsity sharing.

At the heart of the scheduler is a simple yet effective hardware mechanism: a down-counter scheduling FSM. The scheduler first identifies the PE (or MAC) with the maximum PopCount—i.e., the most work to do. This value seeds a down counter that decrements every clock cycle. On each tick, the scheduler compares the current counter value with the PopCounts of all PEs. Those PEs whose workload matches the current counter value are enabled to begin execution. This mechanism ensures that all PEs complete their workload simultaneously with the slowest one—preserving full throughput while smoothing the current profile.

This down-counter PE scheduler architecture, SparseStagger, introduces a power-aware execution strategy that dynamically staggers the activation of processing elements within a column. By leveraging per-PE workload information derived from combined sparsity patterns, the scheduler reduces the likelihood of multiple PEs switching simultaneously. This temporal staggering of computing activity smooths peak current draw, which in turn alleviates transient stress on the power delivery network and minimizes the incidence of VDD droop events. Importantly, this mechanism preserves full throughput. Since overall latency is determined by the slowest PE—the one with the highest PopCount—the scheduler ensures that all other PEs are merely delayed just enough to complete simultaneously with the slowest. This guarantees that no throughput is sacrificed, even as the system benefits from reduced simultaneous switching activity.

From an implementation standpoint, SparseStagger introduces minimal hardware overhead. The primary components include lightweight PopCount units—readily repurposed from existing sparsity acceleration pipelines—a 4- or 5-bit down counter (depending on the number of input channels per computing round), a comparator per PE for matching PopCount values against the counter, and a small finite-state machine for generating clock enables. These elements are compact and easily integrated within modern accelerator control logic. The design also allows for configurable trade-offs between area and power. For example, rather than dedicating flip-flop resources to store PopCounts across cycles, these values can be recomputed on the fly each cycle. This saves approximately 4 to 16 registers per PE, depending on the number of MACs, at the cost of slightly increased dynamic activity. This trade-off proves particularly favorable in scenarios where area is at a premium and computing workload is sparse. The architecture further scales to multi-MAC PEs, which are prevalent in high-throughput designs. In such cases, the scheduler can operate at MAC-level granularity, generating independent enables for each MAC within a PE. This fine-grained control enhances the scheduler’s ability to shape the current waveform and is especially synergistic with the block-level sparsity patterns enforced by SparseBlock (

Section 4.2). Together, the down-counter PE scheduler and sparsity-aware induction form a unified framework for proactive workload-driven VDD-droop mitigation in modern DNN inference accelerators.

Pseudocode for Scheduling: The complete operation of the down-counter PE scheduler, SparseStagger, is captured in the pseudocode in Algorithm 1. The scheduler begins by initializing all PE clock enable signals to zero. It then computes the combined sparsity bitmap for each PE by bitwise-ANDing the input-feature bitmap (

ifbmp) and the filter bitmap (

flbmp), both of which reflect zero-valued compression (ZVC) information. The population count (PopCount) of each combined bitmap gives the total number of MAC operations that the PE must perform during the current round. The PE with the highest PopCount is identified, and its clock enable is asserted immediately to preserve overall throughput. Subsequently, the scheduler performs a descending count from this maximum workload, and in each cycle, enables all PEs whose workload matches the current counter value. This staggered scheduling ensures that PEs with lighter compute loads are activated later, thereby reducing simultaneous switching activity and smoothing peak current draw, while still ensuring that all PEs complete execution synchronously.

| Algorithm 1: Down-counter PE scheduler |

![Jlpea 16 00002 i001 Jlpea 16 00002 i001]() |

6.1.3. Scheduler Behavior, Scalability, and Limitations

To illustrate the operation of the proposed down-counter PE scheduler, a representative example is shown in

Figure 12, where five PEs with combined sparsity workloads of 2, 2, 3, 5, 7 are rescheduled to reduce peak simultaneous activity (note: although the scheduler shows all PEs completing in the same round, the underlying datapath does not deactivate in a single cycle; pipeline stages retire over multiple cycles, limiting the falling-edge di/dt). The PE with the maximum workload (

, PopCount = 7) is activated immediately, while the others are staggered based on their PopCounts. As the counter decrements from 7 to 0, each PE is enabled in the cycle where the counter matches its PopCount value. In this case,

(workload = 5) and

(workload = 3) are enabled in subsequent cycles, while

and

(workload = 2) are activated last. The peak current draw is significantly flattened, with a maximum of only two PEs simultaneously active in any given cycle, achieving a 60% reduction in simultaneous current draw compared to the baseline design that activates all five PEs at once.

Although SparseStagger causes PEs to complete their workloads in the same scheduler round, this does not produce a harmful negative-going current transient. In ASIC accelerators, MAC units do not shut off instantaneously; their multipliers, adders, and pipeline registers settle over multiple cycles, which naturally limits the falling-edge di/dt. PDNs are also designed to tolerate negative load steps, which occur frequently during normal operation when compute blocks become idle. Moreover, the “aligned end” in

Figure 12 reflects scheduler-level completion only; circuit-level retirement is slightly staggered due to pipeline depth and local retiming. Therefore, only the rising-edge activation surge drives droop risk, and SparseStagger specifically targets that dominant failure mode.

One of the strengths of this scheduling scheme is its scalability. Since the scheduler operates independently at the granularity of a column, no inter-column or inter-array coordination is required. Each column computes its sparsity profile and performs staggered activation based on local PopCounts. This modular design enables seamless integration across deep neural network accelerators with many columns or PE arrays, and it naturally supports scale-out architectures. Even when weights and activations are broadcasted across columns—as is typical in modern accelerators for reuse efficiency—each column can still apply independent, locally optimal scheduling without degrading global correctness or throughput. However, there are rare scenarios where the proposed scheduler provides limited benefit. For instance, if all PEs in a column exhibit the same workload (i.e., identical PopCounts), the down-counter strategy degenerates into a simultaneous activation of all PEs, offering no droop mitigation. While such events are statistically uncommon—especially given the typical variation in zero patterns across layers and contexts—a fallback strategy may be employed. In this mode, selected PEs are delayed beyond the normal finish time of the slowest PE, trading off some throughput to achieve further reduction in peak current draw. This secondary mode can be selectively engaged based on operating conditions, such as temperature, frequency, or historical droop behavior, providing a flexible knob for resilience tuning.

Overall, even though the worst-case instantaneous current may not always be improved, the average voltage droop observed across all computing rounds is significantly reduced. SparseDroop achieves this without requiring reactive guardbanding, droop sensors, or complex recovery circuitry, thereby offering a proactive low-overhead mitigation strategy that preserves performance while improving electrical stability.

6.2. SparseBlock: Structured Sparsity for Droop-Aware Scheduling

To complement the dynamic scheduling in SparseStagger, we introduce SparseBlock, a deployment-time sparsity induction technique that enforces accelerator-aligned, block-wise sparsity patterns through light-touch fine-tuning. Unlike conventional fine-grained pruning methods that result in irregular memory accesses and complex control logic, SparseBlock operates on fixed IC-OC block granularity. This structured approach simplifies sparsity metadata, enhances DDR read efficiency, and ensures compatibility with dynamic PE schedulers. Notably, SparseBlock can induce 20–30% weight sparsity with just a few epochs of fine-tuning, offering a more time- and resource-efficient alternative to conventional methods such as 2:4 sparsity.

6.2.1. Architectural Motivation and Design Constraints of SparseBlock

Modern DNN accelerators often store convolutional weights in formats such as

, where the input channel (IC) dimension varies fastest. The notation

refers to the common layout of convolutional neural network (CNN) weights, where H and W denote the spatial kernel height and width,

denotes the output channel dimension, and

denotes the input channel dimension. This layout naturally favors efficient memory access through wide vector fetches along the IC axis. However, conventional fine-grained or unstructured pruning—which allows arbitrary weights to be zero—undermines execution balance across PEs: depending on the sparsity distribution, one PE can receive a nearly dense tile and effectively operate in a dense mode for that round, while others operate with a light load. This skew elongates PE’s active window so that the round remains enabled until it retires; under a simultaneous-start schedule, the resulting overlap concentrates switching activity, raising

peaks and increasing transient VDD droop risk. To overcome these inefficiencies, we propose SparseBlock, a structured block-wise sparsity method that introduces regular zeroing patterns aligned with the hardware’s access granularity. Specifically, the IC dimension is partitioned into fixed groups of 8 channels per output channel (OC). These IC8 blocks are treated as atomic units for sparsification, meaning each block is either fully retained or fully zeroed.

Figure 13 illustrates an example of this pattern for a layer with 16 output channels and 128 input channels.

The motivation for this block-aligned design is twofold. First, it enables highly efficient DDR memory access by aligning zeroed data regions with burst fetch boundaries, allowing entire blocks to be skipped during memory reads. Second, it simplifies computing control logic—particularly for MAC arrays—since only entire blocks are gated off, avoiding the need to dynamically rewire or compress sparse data streams.

To maintain balance and uniformity across processing elements (PEs) while adhering to hardware-friendly access patterns, SparseBlock enforces the following constraints:

Per-OC Locality: Sparsity is applied independently per output channel, where only full IC8 blocks may be pruned. This keeps indexing and decoding local to a single OC context.

Global Uniformity: Each output channel must prune the same number of IC8 blocks to ensure uniform workload across computing lanes. This avoids introducing PE underutilization due to uneven zeroing.

Divisibility Constraint: The number of IC8 blocks pruned per OC must be a multiple of 4. This ensures compatibility with group-wise scheduling in accelerators where multiple MACs share resources and must be staggered in lockstep.

For example, with a 1/4 sparsity ratio (R = 0.25), in a 128-IC × 16-OC convolutional layer, each OC prunes exactly 4 out of 16 IC8 blocks. Across the layer, this results in 64 blocks being pruned (out of 256), and all control paths remain statically aligned. The combination of these constraints makes SparseBlock a highly structured and accelerator-friendly approach to sparsity—providing both efficiency and predictable execution timing.

6.2.2. Structured Encoding and Induction of SparseBlock Sparsity

To minimize both metadata overhead and control complexity, the proposed SparseBlock scheme introduces a coarser-grained sparsity encoding mechanism that aligns closely with hardware memory access patterns and vectorization granularity. Specifically, instead of tracking the presence or absence of individual nonzero weights—as is typical in unstructured sparsity schemes—SparseBlock organizes the weight tensor into logical blocks of shape , where input channels and output channel. Each block is treated as an atomic unit for both sparsity encoding and runtime execution: the entire block is either retained or pruned as a whole.

This structural constraint enables significant compression of the sparsity metadata. In contrast to unstructured sparsity, which requires one bit per weight (e.g., a 1-bit tag for each of the elements in a convolutional layer), SparseBlock only requires one bit per block. For a typical convolutional layer with , , and a block granularity of 8 input channels per output channel, the metadata overhead is reduced by a factor of in the input channel dimension. This drastically cuts down the bandwidth required to stream the sparsity mask from off-chip memory and reduces on-chip storage requirements for bitmap buffering. Additionally, it allows faster parsing of the sparsity pattern in hardware due to the reduced mask dimensionality and predictable alignment.

At runtime, this compressed SparseBlock sparsity map is streamed in parallel with the quantized or compressed weight tensors. It is parsed by a decoder unit that operates in lockstep with the weight fetch controller. Upon encountering a zeroed block in the bitmap, the corresponding weight and activation accesses are suppressed for that pair. Because the blocks are aligned to memory vector boundaries (e.g., 64-bit lines for 8 FP8 values), no additional address realignment is necessary, and compute skipping can be implemented using simple gating logic. This deterministic skipping ensures that the accelerator remains free of irregular memory access patterns, misaligned SIMD operations, or complex scatter–gather buffering logic—challenges that are often present in unstructured or coordinate-based sparse formats like CSR or CSC. In contrast to fine-grained approaches that require runtime indexing, indirection buffers, or zero-aware scheduling logic, the SparseBlock representation enables fully static scheduling and broadcast-friendly loading semantics. Since blocks are organized uniformly across output channels, multiple processing elements (PEs) can simultaneously interpret and apply the sparsity map without any cross-PE synchronization or arbitration logic. This architectural simplicity improves timing closure, reduces dynamic energy per inference pass, and allows for scalable implementations in high-throughput hardware DNN accelerators.

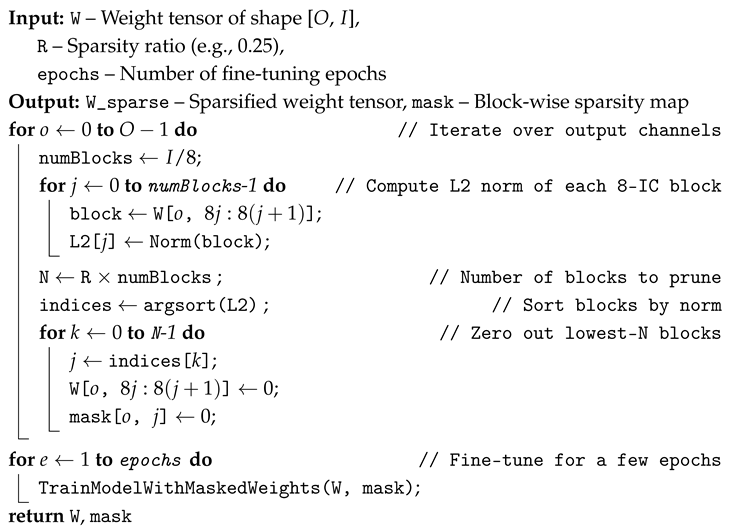

6.2.3. SparseBlock: Sparsification via Lightweight Fine-Tuning

To enable efficient runtime skipping using the SparseBlock format, we apply structured block-wise sparsification through a lightweight fine-tuning process. Rather than inducing sparsity during full model training—which is computationally expensive and rarely feasible for deployment-scale workloads—SparseBlock leverages a norm-based pruning approach that can be applied to pre-trained models with minimal retraining overhead. The method introduces sparsity at the granularity of 8-input-channel blocks (IC8), conforming to hardware alignment requirements. For each output channel, the input channel axis is partitioned into non-overlapping blocks of 8 channels. The norm of the weights in each block is computed, and blocks with the lowest norms—indicating a smaller contribution to the network’s representational capacity—are selected for pruning.

The sparsity ratio is defined as

, where

K is the number of IC8 blocks selected for pruning and

N is the total number of IC8 blocks per output channel. This ratio is incrementally increased across multiple pruning iterations to sparsify the model gradually. After each pruning step, the model is fine-tuned for a small number of epochs (typically 2–3) to recover any potential loss in accuracy caused by pruning. This curriculum-like approach ensures that the network adapts to the introduced sparsity without significant degradation in performance. Compared to fixed-pattern sparsity techniques like

, this approach provides greater flexibility and better alignment with hardware memory and computing organization. Furthermore, because sparsity is introduced post-training through lightweight fine-tuning, the method significantly reduces the computational cost and engineering complexity typically associated with sparsity-aware training. An overview of the proposed

SparseBlock approach is delineated in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: SparseBlock Fine-Tuning Sparsity Induction |

![Jlpea 16 00002 i002 Jlpea 16 00002 i002]() |

6.2.4. Hardware Implications and Synergy with PE Scheduler

The SparseBlock sparsity pattern is tightly integrated with the SparseDroop execution framework, and its hardware implications span both memory hierarchy and computing datapaths. One of the key benefits of SparseBlock lies in its ability to enforce sparsity at the granularity of IC8-OC blocks (i.e., 8 input channels × 1 output channel), which matches the data fetch width and computing parallelism of modern CNN accelerators. This alignment allows the sparsity map to be directly leveraged by memory and computing control logic without introducing irregular access patterns or requiring fine-grained gating circuitry. At the scheduler level, SparseBlock introduces predictable coarse-grained workload imbalance across processing elements (PEs). Since each PE operates on a fixed OC slice, and each OC slice contains a programmable number of pruned IC8 blocks, the number of valid MAC operations varies systematically across PEs in each computing round. This variability directly translates to differences in the PopCount values, which are inputs to the down-counter PE scheduler. As a result, the scheduler can generate staggered execution enables that are both deterministic and power-aware—maximizing delay opportunities for lightly loaded PEs without compromising overall throughput. This structured block-induced sparsity naturally leads to a wider distribution of PopCount values across PEs, which in turn enables more effective temporal staggering and smoother instantaneous current profiles during execution.

On the memory side, block-wise sparsity allows entire DMA bursts corresponding to pruned IC8–OC tiles to be skipped entirely. This significantly reduces pressure on the shared memory bandwidth, especially in edge and battery-constrained inference environments. Since DMA engines typically operate in fixed-width bursts aligned to IC8 tiles, the zeroing of a tile directly maps to a skipped fetch transaction, eliminating partial access logic or per-weight granularity masking. Within the MAC datapath, SparseBlock enables efficient gating of entire cycles. In architectures with SIMD-style parallel MAC units operating on IC8 vectors, the presence of a zeroed block implies that the entire MAC stage can be clock-gated for that output channel in the current round. This reduction in switching activity not only reduces dynamic power but also flattens instantaneous power profiles, further mitigating the risk of VDD droop. Additionally, since this gating is based on statically known sparsity maps, the logic can be implemented with minimal runtime overhead—typically as a bitmap-indexed mask per-PE column.

In summary, SparseBlock enhances SparseDroop’s efficacy by serving as both a structured workload shaper for the scheduler and a hardware-aligned sparsity format for memory and computing efficiency. Its coarse granularity reduces control complexity while maximizing the droop mitigation benefits of temporal staggering and compute gating.

7. Experimental Setup

For SparseDroop, we model a representative accelerator column with 16 processing elements (PEs), each operating on input channel (IC) tiles of size 16, matching the capacity of local IF/FL register files. The IC dimension is fixed at 256, processed in 16 consecutive rounds per output context. For each round, binary sparsity maps of IF and FL are generated according to the target weight/activation density, and the combined bitmap for each PE is obtained by bitwise AND. The population count of this bitmap (PopCount) determines the PE’s workload. In the baseline design, all PEs start simultaneously; in SparseStagger, the down-counter PE scheduler identifies the maximum PopCount, initializes a counter to this value, and enables PEs in cycles where the counter equals their PopCount so that they all complete with the slowest PE, maintaining throughput. We generate one million sparsity seeds to represent randomized sparsity as well as balanced density cases of (25%, 25%), (50%, 50%), and (75%, 75%) nonzero values for weights and activations. For each seed, the simultaneous current reduction is computed as , which directly reflects the reduction in peak and mitigated VDD droop.

For SparseBlock, we evaluate on ImageNet using ResNet50v1.5, ResNet101, VGG16, and Inception v1. In each convolutional layer, the weight tensor is partitioned into non-overlapping IC8 blocks per output channel (OC), and for a target sparsity ratio , exactly blocks (where N is the number of IC8 blocks in that OC) with the lowest norms are zeroed. The model is then fine-tuned for three epochs, and top-1 accuracy is recorded. Because each pruned block maps to a contiguous memory burst and SIMD group, the computing and memory savings scale proportionally with R.

Simulation Environment and Modeling Assumptions

SparseDroop was evaluated using a custom cycle-accurate architectural simulator that models PE-level switching activity and the precise enablement behavior of the down-counter scheduling mechanism. The simulator is implemented using Python 3.10 and C++17, with NumPy used for bitmap manipulation, sparsity sampling, and pseudo-random generation of input/weight sparsity patterns. The event-driven simulation kernel operates at single-cycle granularity. For every computing round, the simulator generates binary sparsity maps for both input-feature (IF) and filter (FL) tiles based on the target sparsity levels. These bitmaps reflect the compressed zero-value compression (ZVC) format used in real DNN accelerators. A bitwise-AND operation between IF and FL maps is computed for each PE, producing the combined sparsity bitmap. The population count (PopCount) of this combined bitmap corresponds to the number of useful multiply–accumulate operations the PE must perform in that round.

Using these PopCount values, the simulator constructs detailed cycle-by-cycle activity waveforms. In the baseline (simultaneous-start) mode, all PEs begin executing immediately after data load, and each PE remains active until completing its PopCount-determined workload. In the SparseStagger mode, we implement the down-counter scheduler exactly as defined in Algorithm 1 of the manuscript. The scheduler identifies the PE with the maximum PopCount, initializes a counter to that value, and decrements the counter every cycle. For each counter value, the simulator activates PEs whose PopCounts match the current count, thereby enforcing the staggered-launch paradigm. The simulator tracks the number of simultaneously active PEs at each cycle, which directly represents the instantaneous level of concurrent switching activity. Because peak number of active PEs correlates strongly with ASIC instantaneous current (ICCmax), this metric enables a clean architectural comparison between baseline and staggered execution without the confounding influence of device-specific PDN characteristics. Waveforms and histograms of active PE counts are then extracted to quantify reductions in peak concurrency. This simulation methodology is cycle-exact with respect to MAC toggling behavior, PopCount-driven workload variation, and scheduler-induced temporal shifts in computing activation. It provides full reproducibility of the results while isolating the architectural effects of SparseDroop from platform-specific PDN dynamics, which is important for generalization and for meaningful comparison across sparsity distributions.

8. Conclusions

This work introduced SparseDroop, comprising SparseStagger, a lightweight scheduler that leverages workload sparsity to mitigate VDD droop without impacting throughput, and SparseBlock, an architecture-aligned sparsity method that preserves accuracy while reducing computing and memory demands. Experimental results showed that SparseStagger consistently reduces peak simultaneous current demand across diverse sparsity scenarios, while SparseBlock achieves <1% accuracy loss at low practical pruning ratios and provides linear efficiency gains. Together, SparseDroop demonstrates that sparsity can serve as both a computational optimization and a system-level mechanism for power delivery stability. Future directions include extending these methods to transformer-based workloads and integrating them with dynamic voltage and frequency scaling for holistic efficiency improvements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and D.A.M.; methodology, A.R.; software, A.R.; validation, A.R., D.A.M. and A.D.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, A.R.; resources, S.K.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R., S.K., A.D. and S.K.G.; writing—review and editing, S.K., A.D. and S.K.G.; visualization, A.R. and A.D.; supervision, A.R. and D.A.M.; project administration, D.A.M.; funding acquisition, D.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge the contributions of Raymond Sung, Michael Wu, and Engin Tunali, who contributed to the writing of the initial patents based on this idea during their time at Intel Corporation.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are employed by the Intel Corporation.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASIC | Application-specific integrated circuit: custom hardware optimized for |

| a specific computation |

| PDN | Power delivery network: supplies stable voltage to on-chip components |

| PE | Processing element: executes MAC operations in the accelerator |

| MAC | Multiply–accumulate unit: the primary source of switching activity |

| IF | Input-feature map tile consumed by a PE |

| FL | Filter (weight) tile used by a PE during convolution |

| PopCount | Number of nonzero combined IF–FL entries: determines PE workload |

| Sparsity Map | Binary bitmap indicating nonzero activations or weights |

| SparseStagger | Workload-aware scheduling method that staggers PE start times |

| SparseBlock | Offline block sparsity method used to improve scheduling predictability |

| SparseDroop | Combined framework (SparseStagger + SparseBlock) for droop mitigation |

| Voltage Droop | Temporary supply voltage dip caused by rapid current increase (L·di/dt) |

| RTL | Register-transfer-level hardware description used for digital simulation |

References

- Mohaidat, T.; Khalil, K. A survey on neural network hardware accelerators. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 3801–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, B. Hardware for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Hot Chips 35 Symposium (HCS), Palo Alto, CA, USA, 27–29 August 2023; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Whatmough, P.N.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, H.; Rama, S.; Brooks, D.; Wei, G.Y. 14.3 A 28nm SoC with a 1.2 GHz 568nJ/prediction sparse deep-neural-network engine with >0.1 timing error rate tolerance for IoT applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francsico, CA, USA, 11–15 February 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K. A Comparison of Digital Droop Detection Techniques in ASAP7 FinFET. Res. Rev. Sep. 2019. Available online: https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~kevinz/droop/report.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Pandey, P.; Gundi, N.D.; Basu, P.; Shabanian, T.; Patrick, M.C.; Chakraborty, K.; Roy, S. Challenges and opportunities in near-threshold dnn accelerators around timing errors. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2020, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Feng, J.; Shoukry, A.; Zhang, X.; Magod, R.; Desai, N.; Gu, J. Proactive power regulation with real-time prediction and fast response guardband for fine-grained dynamic voltage droop mitigation on digital SoCs. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits), Kyoto, Japan, 11–16 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh, I.; Alizadeh, K.; Mehta, S.; Del Mundo, C.C.; Tuzel, O.; Samei, G.; Rastegari, M.; Farajtabar, M. Relu strikes back: Exploiting activation sparsity in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.04564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, A.; Mathaikutty, D.A.; Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S.K. FlexNPU: A dataflow-aware flexible deep learning accelerator for energy-efficient edge devices. Front. High Perform. Comput. 2025, 3, 1570210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Raha, A.; Mathaikutty, D.A. SwiSS: Switchable Single-Sided Sparsity-based DNN Accelerators. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 5–7 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Riad, J.; Sánchez-Sinencio, E.; Li, P. Dynamic heterogeneous voltage regulation for systolic array-based DNN accelerators. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 38th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD), Hartford, CT, USA, 18–21 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 486–493. [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento, D.V.C.; Georgiou, K.; Eder, K.I.; Xavier-de Souza, S. Evaluating the effects of reducing voltage margins for energy-efficient operation of MPSoCs. IEEE Embed. Syst. Lett. 2023, 16, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Zu, Y.; Reddi, V.J. Energy efficiency benefits of reducing the voltage guardband on the Kepler GPU architecture. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Silicon Errors in Logic-System Effects (SELSE), Stanford, CA, USA, 1–2 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A.; Benini, L.; Gupta, R.K. Application-adaptive guardbanding to mitigate static and dynamic variability. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2013, 63, 2160–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschanz, J.; Kim, N.S.; Dighe, S.; Howard, J.; Ruhl, G.; Vangal, S.; Narendra, S.; Hoskote, Y.; Wilson, H.; Lam, C.; et al. Adaptive frequency and biasing techniques for tolerance to dynamic temperature-voltage variations and aging. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference. Digest of Technical Papers, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–15 February 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 292–604. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, K.A.; Raina, S.; Bridges, J.T.; Yingling, D.J.; Nguyen, H.H.; Appel, B.R.; Kolla, Y.N.; Jeong, J.; Atallah, F.I.; Hansquine, D.W. A 16 nm all-digital auto-calibrating adaptive clock distribution for supply voltage droop tolerance across a wide operating range. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2015, 51, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadimas, S.; Tsiatouhas, Y.; Arapoyanni, A. Timing error tolerance in small core designs for SoC applications. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2015, 65, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Rangineni, K.; Ghodsi, Z.; Garg, S. Thundervolt: Enabling aggressive voltage underscaling and timing error resilience for energy efficient deep learning accelerators. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Design Automation Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanam, V.K.; Mahurin, E.; Bowman, K.A.; Abraham, J.A. A Proactive System for Voltage-Droop Mitigation in a 7-nm Hexagon™ Processor. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2020, 56, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Kundu, S.; Raha, A.; Mathaikutty, D.A.; Raghunathan, V. Harvest: Towards efficient sparse DNN accelerators using programmable thresholds. In Proceedings of the 2024 37th International Conference on VLSI Design and 2024 23rd International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID), Kolkata, India, 6–10 January 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1510.00149. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Liu, X.; Mao, H.; Pu, J.; Pedram, A.; Horowitz, M.A.; Dally, W.J. EIE: Efficient inference engine on compressed deep neural network. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2016, 44, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Huang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J. Accelerating transformer pre-training with 2:4 sparsity. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.01847. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.; Han, S.; Pool, J.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Dally, W.J. Exploring the regularity of sparse structure in convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.08922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plochaet, J.; Goedemé, T. Hardware-aware pruning for fpga deep learning accelerators. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 4482–4490. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.; Soma, R.; Pedram, M. Fine-grained dynamic voltage and frequency scaling for precise energy and performance tradeoff based on the ratio of off-chip access to on-chip computation times. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2005, 24, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Han, L.; Jin, R.; Su, Y.J.; Ho, C.; Yin, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; et al. 7.2 A 12 nm programmable convolution-efficient neural-processing-unit chip achieving 825TOPS. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference-(ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–20 February 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 136–140. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Overview of SparseDroop—leveraging inherent (SparseStagger) and induced block sparsity (SparseBlock) to stagger/cap MAC activity, reduce , and mitigate VDD droop.

Figure 1.

Overview of SparseDroop—leveraging inherent (SparseStagger) and induced block sparsity (SparseBlock) to stagger/cap MAC activity, reduce , and mitigate VDD droop.

Figure 2.

Representative DNN accelerator architecture with columnar PE hierarchy for scalable computing and bandwidth-efficient data movement.

Figure 2.

Representative DNN accelerator architecture with columnar PE hierarchy for scalable computing and bandwidth-efficient data movement.

Figure 3.

Sparsity-aware MAC logic using compressed activations and weights. Bitmaps enable efficient identification of valid operand pairs for computing, reducing unnecessary operations, and leveraging dynamic sparsity.

Figure 3.

Sparsity-aware MAC logic using compressed activations and weights. Bitmaps enable efficient identification of valid operand pairs for computing, reducing unnecessary operations, and leveraging dynamic sparsity.

Figure 4.

Sparsity-aware MAC design with multiple parallel multipliers and adder tree, enabling efficient processing of valid operand pairs identified through multi-bit sparsity logic.

Figure 4.

Sparsity-aware MAC design with multiple parallel multipliers and adder tree, enabling efficient processing of valid operand pairs identified through multi-bit sparsity logic.

Figure 5.

PE design with multiple MAC units using distinct IF and FL register files per output context. Context-aware accumulation enables parallel computing across IC-OC pairs, with execution shaped by operand sparsity patterns.

Figure 5.

PE design with multiple MAC units using distinct IF and FL register files per output context. Context-aware accumulation enables parallel computing across IC-OC pairs, with execution shaped by operand sparsity patterns.

Figure 6.

Start/end of computation across multiple PEs.

Figure 6.

Start/end of computation across multiple PEs.

Figure 7.

Tiled execution model where IC sets are sequentially broadcasted to all PE columns, each handling a distinct OC tile. This structured IC-OC mapping enables block-level sparsity exploitation for computing and memory savings.

Figure 7.

Tiled execution model where IC sets are sequentially broadcasted to all PE columns, each handling a distinct OC tile. This structured IC-OC mapping enables block-level sparsity exploitation for computing and memory savings.

Figure 8.

Reduction in simultaneous current demand for down-counter PE scheduler.

Figure 8.

Reduction in simultaneous current demand for down-counter PE scheduler.

Figure 9.

ImageNet top-1 classification accuracy vs. compute/memory bandwidth saving. Top-1 accuracy loss is inversely proportional to savings.

Figure 9.

ImageNet top-1 classification accuracy vs. compute/memory bandwidth saving. Top-1 accuracy loss is inversely proportional to savings.

Figure 10.

New generic rescheduling of the start of PE execution with lower combined sparsity than slowest PE.

Figure 10.

New generic rescheduling of the start of PE execution with lower combined sparsity than slowest PE.

Figure 11.

Block diagram of the proposed PE computation scheduler.

Figure 11.

Block diagram of the proposed PE computation scheduler.

Figure 12.

New down-counter-based rescheduling of the start of PE execution.

Figure 12.

New down-counter-based rescheduling of the start of PE execution.

Figure 13.

Exemplary SparseBlock sparsity pattern for R = 1/4. Each OC contains exactly 4 IC8 blocks that are pruned. This enforces alignment with vectorized memory and compute units.

Figure 13.

Exemplary SparseBlock sparsity pattern for R = 1/4. Each OC contains exactly 4 IC8 blocks that are pruned. This enforces alignment with vectorized memory and compute units.

Table 1.

Top-1 image classification accuracy.

Table 1.

Top-1 image classification accuracy.

| Network | FP32 Baseline | R = 1/16 | R = 2/16 | R = 3/16 | R = 4/16 |

|---|

| Inception V1 | 70.7 | 70.4 | 70.0 | 69.4 | 68.7 |

| Resnet50 V1 | 75.1 | 74.9 | 74.7 | 74.6 | 74.5 |

| Resnet101 V1 | 76.4 | 76.3 | 76.2 | 76.0 | 75.8 |

| VGG16 | 71.7 | 71.6 | 71.6 | 71.3 | 70.9 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |