Abstract

Ideology is a systemic property of cognition central to the transmission and actualization of beliefs. Ideologies take many forms including religious, philosophical, popular and scientific. They play a central role in both personal identity and in the way society holds itself together. Therefore, it is important to understand how to model identities. The article introduces ideologies as a function of cognition that have been described by political scientists and critical theorists. There follows a typology of ideologies that shows their increasing complexity as societies develop. These considerations lead to the identification of key elements and variables in an ideology that can be expressed mathematically together with some of their systemic relations. These variables may be used to estimate the validation of ideologies.

1. Introduction

Jean Piaget’s [1] theory of cognitive development shows that as children develop their thinking becomes more complex. His stage theory describes this increasing complexity. In the first 18 months or so in the sensori-motor stage thinking is essential pre-representional. With the emergence of language thinking becomes representational and increasingly logical across domains and in early adolescence a type of formal thinking emerges allowing more systematic manipulation of possibilities. Whatever the current position taken on the accuracy of the details of this theory, it is clear Piaget had an enormous influence on the field of cognitive development (e.g., [2,3]). Two key aspects of his work are germane here, the idea that what we know is a model of our experience that is constructed, and the idea that the structure of these constructions may be usefully categorized into stages of increasing complexity.

Central to Piaget’s [1] constructivist approach is the concept of equilibration, that is, that the thinking individual strives to maintain a cognitive balance between what is expected and experienced. The individual assimilates experience in terms of what has already been experienced and remembered, and accommodates to new experience by noticing differences between what was learned previously and the present. Therefore, new events are interpreted through the filter of what was learned previously. The various approaches to ideology that follow in this paper reflect other paradigms and approaches to ideology, however, they each depend on a complex interpretive structure that is a human and social construction used like a filter to view society. This is essentially what Piaget called assimilation. It has the advantage of simplifying experience, and the disadvantage of obscuring features of experience that do not fit.

These constructivist ideas are clearly embedded in discussions about ideologies in the broader social and political domain. For example, Terry Eagleton ([4], p1) has described a set of characteristics or definitions of ideologies including the following:

- (a)

- the process of production of meanings, signs and values in social life;

- (b)

- a body of ideas characteristic of a particular social group or class;

- (c)

- ideas which help to legitimate a dominant political power;

- (d)

- false ideas which help to legitimate a dominant political power.

Constructed ideas are used to define “reality” and, as a way of seeing, they limit or constrain other ways of seeing and acting socially. In a similar vein, Mullins [5] emphasizes four qualities in ideology: the way ideas have (1) power; (2) guiding evaluations; and (3) guiding actions. The fourth characteristic was that the ideology must be logically coherent. Given that thinking in individuals and societies has a necessary systemic quality from a cognitive point of view, this coherence is necessary and explains in part the violence that totalitarian groups exercise in the face of alternative visions of “reality”. Further, when an ideology plays an important role in guiding human-social interaction and in the structure of organizations, the coherence of these organizations requires their normative acceptance [6].

The pervasive influence of an ideology is also emphasized by Cranston [7] who points out that in an ideology practical elements have similar importance to theoretical elements. As in many systems ideas can be used both as explanatory principles and descriptive ones. Therefore, one main function of an ideology is to act as a principle or set of principles by which to change society by providing a set of norms that are used as a guide for change through a normative thought process. In Duncker’s [8] view ideology claims absolute truth.

Cultural consensus is achieved through ideology. Sometimes this consensus may be held by a small and powerful group of individuals. We use the term ideology more broadly so that here it is concerned with identity and cultural continuity and is made up of ideas, symbols and beliefs. Therefore:

- (1)

- An Ideology is a system of ideas that an individual or a social group holds over time to which they are committed;

- (2)

- Ideology is an organizing world view that obscures aspects of experience and when it operates as a closed belief system is impervious to evidence contradicting its position;

- (3)

- All ideology diminishes the importance of individuals [9].

From this perspective, the ideologically motivated actor is one who uses stereotypes to analyse events and our understandings of an author (authority, originator) and an individual agent must take account of the inevitable interpretation that follows from such motivation. To the extent that the Philosophical, Political or Religious ideology is doxical and even reflected in economic relations, it expresses in specific language a certain mental model of human relations, or a view of a commonly held structure to society. This doxical ideology, however, will tend to close the debate.

Nevertheless, theoretical treatment of any ideology firstly has to be located at a synchronous level. Relations between synchronous and diachronic order are complicated because changes in the content and structure of a social system are interdependent. If we are to provide a mathematical model of a system, it must take account of both the synchronous case and the diachronic case. In the synchronous case, static or dynamic models may be constructed. In the diachronic case, we have to consider History and content as multiform movements involving heterogeneous elements. Ideology infuses society at every level, expressing the Social System’s structure. Every individual in a society constructs their own understanding of their social world on the basis of their personal histories. The way this is done usually depends on the dominant ideology in the society, i.e., capitalist, communist, and so on. Sometimes the individual is faced with a choice, between a new ideology or remaining with the traditional. In today’s world, there are choices between populist solutions to social problems and the traditional established political solutions. Following Jacques Lacan’s theory, human choices are made by distortions of ideologies in the mirror of language. For example, populism may provide quick solutions that disrupt the system in the long term, while the traditional approaches have ignored the problems populists find important. Following any choices there are positive and negative consequences, and being too focused with an ideological bias may result in being blind to some of the alternatives.

We view science as a form of ideology with its own methods and perspectives. Other well-known ideologies include ones based on economic theories such as communism, free trade, laissez-faire economics, mixed economy, mercantilism, and social Darwinism. Therefore, while we consider the scientific method as an ideology, this does not imply that it is incorrect to do so. Rather as an ideology science provides a way of organizing experience so that what we think we know can be tested against what we experience in experiments so moving beyond subjective interpretations. In everything concerning the study of the ideologies we can consider the problem in a double sense:

- (1)

- Homogeneity: each discourse informs a content previously given and that operates under its own syntaxes. This means that each ideological approach has its history and ways of solving problems, in short constitutes a paradigm. As such, problems at its boundaries are difficult to solve and may require a new paradigm. Ideologies impose a focus that produces a theoretical blindness (Kahneman, [10]);

- (2)

- Heterogeneity: the relation of reality to language introduces a complete displacement of all the usual connections to reality, a fact that makes it impossible to consider the reality-language connections as simple duplicates. This is a central feature of constructivism, that we each have different ways of making sense of the world. Inevitably, there will be differences that depend on the ways we make sense that depend on the experiences that we prioritise in coming to know. Therefore, no one has a monopoly on truth, there are different ways of accounting for experience.

If we relate these ideas to voting behaviour, early studies indicated it was primarily influenced by partisan identification often coming from the influence of the parents [11]. More recent studies however, indicate that party identity and ideology are more closely aligned [12]. In the recent 2016 voting patterns in England (Brexit) and in the USA (Presidential Election) this tendency to identify with issues and ideologies was highlighted. We argue, along the lines described by Kahneman [10], that it is what the voter holds most dearly that provides the basis for decision making, It seems that in the British case the desire to control immigration played an important role, and in the US case it was the desire to move away from the established political model. However, in each case these positions were associated with racist and or sexist positions. These elections provide examples of how political ideology is closely aligned with socially motivated cognition [13]. What is distinctive in the present paper is the step towards the development of a mathematical algorithm to account for decisions, a process advocated by Kahneman [10] in his study of behavioural economics.

There is a substantial body of literature on ideologies beyond the scope of this paper that includes contributions from a variety of domains including political science, sociology, philosophy and psychology. Given such a breath of scholarship we decided here to approach ideology principally as a way of framing cognition akin to assimilation in Piaget’s [1] theory, though such framing when developed will have wide social implications.

In what follows, we first present a classification of ideologies to illustrate a diachronic or developmental approach to ideologies. Systems may be broadly defined in terms of their elements and their interrelations so next we consider elements and variables in ideological systems. Our purpose is to provide a context for developing a mathematical model of ideologies. Details of this work are introduced in the paper and the definitions provided later give an indication of how an algorithm can provide an account of ideological elements and their dynamic relationships.

2. Typology of Ideologies

Walsby’s theory [14] is an historical proposal of a taxonomy of seven major ideologies. These are organised in historical sequence according to their order of appearance, reflecting the progressive development of needs in human social structures. In some ways, this taxonomy reflects a developmental process like that offered by John Dewey [15] when he proposed three levels of moral judgment a pre-conventional a conventional and a post-conventional level. As a (hypothetical) developmental sequence, Walsby’s ideologies are perhaps like stages of moral development with a society’s position on the sequence depending on the opportunities given to think about essential features of the given stage. The more opportunities given to think about ideologies the more likely one is to identify with more advanced human needs, without necessarily rejecting completely preceding ideologies. At the beginning the societal-individual interface prioritizes the social and with time this interface alters towards prioritizing the individual. Walford [16,17,18] divides Walsby’s major ideological categories into three groups: a group that emphasizes stability of society as a central goal while allowing varying degrees of flexibility, a group that emphasizes the importance of human needs over the importance of society again with varying degrees of flexibility, and a final position that is concerned with ideology a meta-dynamic group.

- (1)

- Ediostatic group: The ideologies in this group are:

- (a)

- The Protostatic Ideology: The function of this ideology is to provide a stable social group offering protection against other groups. Identifying with the group was important for survival so thinking was necessarily very conservative and dominated by social cohesion. The group’s thinking is focused on the in-group and hostile or potentially hostile to the out-group;

- (b)

- The Epistatic Ideology: This ideology is one in which improvements to the society become accepted by beginning to recognize individual rights. In some ways it is like Kohlberg’s stage 3 “Good boy, good girl” morality. One religion is likely to be accepted but other religions can exist. It may be described as a transition from the extreme Right to conservatism;

- (c)

- The Parastatic Ideology: A feature of this view is that additional improvements are made for individuals in society through the influence of the sciences. Liberalism with its support for religious tolerance and free political institutions is associated with this ideology.

- (2)

- Ediodynamic group: Following these ideologies emphasizing society the ediodynamic ideologies arose, concerned with restrictions to individual freedom. The emphasis has changed from conserving society and restricting individual freedom to promoting individual freedom. Improvements to living can be made by changing society. However, in each successive ideology there are less constraints on emerging dynamic forms of thinking. The ideologies in this group are:

- (a)

- The protodynamic ideology: Here society is seen to be made up of classes and in this ideology the emphasis is on restructuring society along the lines that we know as social democracy. It is the first step away from conserving society based on individual freedoms;

- (b)

- The epidynamic ideology: This ideology moves further away from social stability of the existing society by identifying class conflict as a medium of social change. Progress is achieved by resolving perceived conflict. Politically this is a form of communism;

- (c)

- The Paradynamic ideology: In cognitive change there is a balance between what was known and emerging knowledge. As the constraints are removed the changes become anarchic. Therefore, the only limit on freedom is that of the individual, that is, the individual is prioritized in the society-individual interface.

- (3)

- Metadynamic group: People in this group recognize that all ideologies depend on key assumptions. Each assumption brings its own constraints between (1) groups of individuals and (2) between individuals and societies. Studying the constraints allows insight into ways ideologies constrain freedoms.

Maturana [19] had described “manners of living” that are like paradigms or ways of looking at the world. They suggest varieties of different ways that a person or group of people approach their experience of the world. Such “manners of living” suggest another taxonomy that is descriptive of types of world view or ideology orthogonal to the previous one:

- (a)

- Affirmative Ideology: An ideology that is dominated by affirmative themes and overemphasises an optimistic world view;

- (b)

- Negative or Divergent Ideology: An ideology overly dominated by negative criticism. There are many ways of being negative such as continually calling into question views expressed about the need for careful management of resources;

- (c)

- Polar Ideology: Polar ideology is a negative oriented ideology that seems to derive its identity by being oppositional and antagonistic;

- (d)

- Marginal Ideology: Those theories on the edge are marginal. Marginal ideologies border between affirmative and negative. For example: As for violent radical Islam, Feldman [20] considers it a marginal ideology—which in many ways it is. He goes on to envision what a Middle East beyond violent jihadism could be, quoting a saying of the Prophet Muhammad on the need for a greater jihad concerned with self-development;

- (e)

- Split Ideology: Theories that indicate one thing while encouraging the opposite.

People often think of ideologies as guiding political thinking with examples associated with political parties on the left or right of the political spectrum. Well known examples on the left include the British Labour Party, the French socialists, or various Marxist regimes. On the right, examples include the British UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party), the US Republicans and the French National Front. The Cambridge academic Raymond Williams [21,22] contributed significantly to the Marxist critique of culture. His writings include the view embedded in cognitive development that ideas including ideological ones change when they meet challenging experiences. All ideas are continually in some sort of dynamic balance with both the past ideas from which they emerged and the contemporary discussions on their meaning and relevance in any society, particularly ones that encourage debate. Williams felt this worked best when it was voluntary and internalized both individually and socially. Williams [22] using Gramsci’s [23] notion of hegemony identified three cultural forces:

- (1)

- The dominant ideology or ideology now in force;

- (2)

- The residual ideology. Ideology that was dominant;

- (3)

- The emergent ideology. Ideology that is evolving in resistance to dominance.

All of these are co-present at any one moment of cultural history.

The concept of dominant ideology was defined firstly by Marx and Engels in the book The German Ideology [24]. Dominant ideologies are invisible in being taken for granted and so are not likely to be immediately challenged. All other ideologies, in contrast, will inevitably challenge the dominant ideology. Marx saw the superstructure as containing the dominant ideology. These were the values and beliefs most people take for granted at a specific cultural and social time. Any individual may relate to the dominant ideology in one of three ways:

- (1)

- The first is identification: the actor subject accepts the values and beliefs in society;

- (2)

- The second is counter-identification: the actor subject opposes the values and beliefs in the dominant ideology, and by this acceptance confirms the dominant ideology and fails to notice problems in the society;

- (3)

- The third position is termed dis-identification: this happens when a subject actor adopts an identity in opposition, rather like reframing the subject in a newer paradigm. Dis-identification requires a transformation in the way the subject is ideologically defined. It is a matter of understanding people differently, in terms of their relations to one another, and in the ways institutions relate to and define people. The concept of dis-identification is useful in analyzing group inter-relationships in sociopolitical categories such as class, race, and gender. Pecheux [25] has argued we make meaning with implicit ideological intent in our words, expressions, propositions. However, it is the meaning not the intent of the speaker that arises from the subject’s position in a conversation when most people in a society belonging to a particular Deontic Impure System (DIS) adopt the status quo and do not even want to think of alternatives, we have a hegemony or a dominating world view. This hegemony has the corollary of the over-simplistic argument of philosophers and writers of the 20th century that adjustments to the language in the media may produce ideological homogeneity.

Williams [22] describes residual ideology as referring to beliefs and practices that are derived from an earlier stage of society. Myth is still a vital component in the life of any community, still a motivating factor in our actions, and a matrix of any residual ideology of our civilization. Maybe the family belongs to a sort of residual ideology in which it was quite useful in the past for young adults to have babies because they could contribute to the family income at a very early age. We are talking of the pre-industrial situation, and maybe we still have that residual ideology in modern society. In fact, this classification complements the previous ones; an ideology can be dominant or derived (in its social context), emergent and marginal.

For Williams [22] an emergent ideology refers to those values and practices which are developing in society outside of, and sometimes actively challenging, the dominant ideology. Williams saw residual ideology as the traditions and practices of the past that were remembered or influenced the present, and saw oppositional ideologies as being like the dis-identification described above. Each type of ideology, residual, oppositional and emergent, potentially playing out a cultural dynamic at specific moments in history.

The historian George Rudé [26] emphasised two forms of ideologies: (a) Inherent, which are the beliefs people in the culture or society hold generally; (b) Derived, these are the programs for change that arise from a critique of the society. Rudé argues that traditional defensive struggles like strikes about changes to work practices are to be expected within inherent traditional ideologies. Real social change requires the addition of a derived ideology that contains new goals. George Rudé’s theory was that popular ideology emerges from the interaction between people’s life experiences and the newly emergent derived ideology that captures this life experience best [26]. Popular ideologies are dynamic and fit the society in which they flourish. Ideas meet reality in a dynamic where they are accepted or rejected by influences on the subordinate class according to whether they fit their experiences and capture their imaginations. Popular ideologies, such as populism today, arrive by means of a mix of important local concerns, like immigration and self-determination in England, and an outside structure such as Brexit. Previous examples of these “structured” ideas have included the Rights of Man, Nationalism and Marxism-Leninism.

Reference to values in ideologies implies the significance of inherent ethical principles. These are in part based on the traditions of a society and in part on the emergent experience of the population in the face of new technologies as referred to above. Ideologies influence all dimensions of a society including education, health care, labor law and justice. Political ideologies pay particular attention to goals and methods so as to mesh well with the issues arising in the daily lives of their constituents.

3. Elements of an Ideology

Social organization relates to ideology in a variety of ways including social commitment, and the transparence of the ideology to social organization. An ideology that is well connected with the daily lives of the society will work well. Therefore, an ideology with appropriate properties achieves social significance through them. Some characteristics of ideologies are:

- (1)

- Personal commitment to an ideology is a potent and evident feature. Without personal commitment, ideologies would wither through lack of support. We would need other variables to study social systems;

- (2)

- Ideologies are systems that are bigger than their expression in committed believers. The believers know the parts of the ideology that form parts of their expressed identities. However, they will recognize other aspects of the ideology since ideological systems have their own coherence. The parts of the ideology that individuals do not like will provide grist to the mill for ideological change and development;

- (3)

- Psychological mechanisms are clearly involved in ideologies and their influence. Partly this is a function of identification with the values of an ideology that goes a long way to explain commitment. The connectedness of an ideology in society is also due to the social psychology of group behavior;

- (4)

- The life span of an ideology is a function of the social relevance of the ideas rather than the individual believers;

- (5)

- Ideologies are enormously variable in terms of content;

- (6)

- The boundaries of an ideology may be difficult to define. Neat boundaries may occur if the boundaries are constructed with some social purpose in mind, determining who is “in” and who is “out”. Of course, different social groups with different ideologies are a paradigm case of clear boundaries, but whether this is because of the social groups or the ideologies is a moot point.

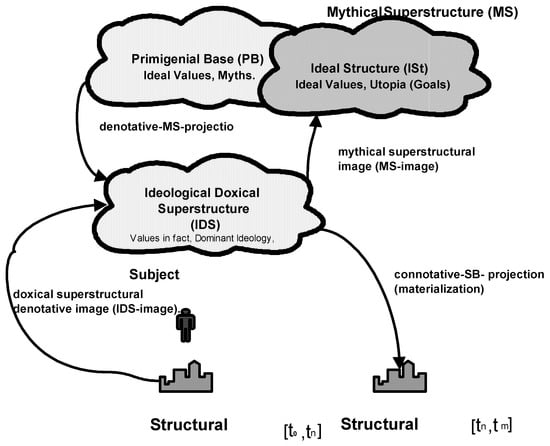

In the Deontical Impure Systems (DIS) (Impure sets and their mathematical properties have been previously defined in Nescolarde Selva et al. [27]) approach, the superstructure of social systems has been divided in two [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

- (1)

- Doxical Superstructure (DS) is formed by values in political and religious ideologies and culture of a human society in a certain historical time;

- (2)

- Mythical Superstructure(MS) also has been divided in two parts:

- (a)

- MS1 containing mythical components or primogenital bases of ideologies and cultures with ideal values;

- (b)

- MS2 containing ideal values and utopias that are ideal wished and unattainable goals of belief systems of the Doxical Superstructure (DS).

These ideas are summarized in the following diagram (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Deontical Impure Systems (DIS) approach.

The following elements [40,41] are listed in the order that would be logically required for a first approach to understanding an ideology. This does not imply priority in value or in a causal or historical sense.

- (1)

- Values. Like ideologies, values define the good in particular domains. We refer to ideal values belonging to the Mythical Superstructure (MS). They are goals in the sense that they are the values in terms of which the Doxical Superstructure (DS) is justified. Ideal values are generally tightly associated with the reward systems socially in place for particular social attributes, like heroic characteristics or fidelity to the system. Values have a function in a society like the action of evolution, that is, it is after the fact that the inherent value is recognized and lauded. Therefore, values are really a posteriori rather than a priori. Values emerge through reflection on the structural base (SB) and may then be generalized towards a new use in a flexible way. Many cultural events are expressions of cultural values in concrete situations that allow the society to relive the abstract values (take for example, the New Zealand Haka at the beginning of international rugby games);

- (2)

- Substantive beliefs (Sb) [36]. They constitute the basic and important beliefs in any ideology. Statements such as: equality is important, the right to vote, God created the World, Slavery is Wrong. For believers, the substantive beliefs are crucial;

- (3)

- Behavior. The way believers act may assume other believers think and act the same way. However, this may not be the case. If we take the example of a particular political or religious ideology, it consists of detailed doctrines and policies that emerge over a long period of time from the relevant substantive beliefs. Even naming the believers takes time whether they are Far Right, Communists, or the Real IRA (Irish Republican Army). The believers work together and then experts work out what is the correct behavior, the “right” values and so on;

- (4)

- Language. A language L is the logical expression of an ideology relating one substantive (Substantive beliefs [36,37] make up a system’s axioms, and most of the beliefs make up their theorems) belief [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] to the others in the belief system. Language is understood from repeated patterns in the use of sets of beliefs. The meanings are implicit, and often applied inconsistently. Let Sb be a substantive belief. We have proposed the following rules of generation of ideologies [33]:

Like many logical arguments, this one consists of the addition of two characteristics: hypothesis and goal.

- (5)

- Perspective. Perspectives of an ideology consist of their key ideas or tools. How does the ideology help adherents think about their social neighbors, their environment, and their own social context. How do we view neighbors or neighboring countries or immigrants? Is the relationship one of equality, or of friendship, or as dominators? How do individuals perceive themselves in the society? Perspective may exist in the Mythical Superstructure [32,33,34,35,36,38,40]. Perspective may also provide an explanation of how we come to be as in the case of religious belief and the answer to questions about the purpose of our lives. Cognitive orientation, identification and meaning (d-significances [31]) and are provided;

- (6)

- Prescriptions and proscriptions. Included here are ethical options, policy options and recommendations about behavior (deontic norms). These are the connotations, the projections from the interpretations of the belief system (IDS) to the Structural Base (SB). Within the Marxist tradition examples include Marx’s Communist Manifesto, Lenin’s What is To Be Done. Hitler’s Mein Kampf is an example of prescriptions within the Fascist tradition. Deontic norms provide a clear link of an MS-image with SB-projections illustrating the abstract idea (in the Mythical Superstructure as an Ideal Structure) and the experienced belief actualized in behavior. The social group acts on prescriptions or not and are rewarded or not by the social group;

- (7)

- Ideological Technology. Borhek and Curtis [41] describe how beliefs in an ideology are related to values. Some beliefs deal with subjective legitimacy and others with the effectiveness of d-significances. For example, the technology of an ideology consists in political activism and organizational strategy. It provides the means achieving the goals of the ideology, both in the Structural Base (immediate) or in the long term Ideal Structure as the Utopia. Ideological Technology while a central part of an ideology is on a different level to belief systems. That is, it may limit substantial beliefs, and commitment to it may be different without altering commitment to the ideology. The Ideological Technology adopted may cause changes to the ideology as can prescriptions for action or indeed living in the Structural Base. Each condition may have social consequences providing opportunities to reconsider beliefs and their implications. A good historical example is provided by Western Europe’s Eurocommunism. Ideological Technology may become symbolic through the DS-image and an inverse MS-image on the Primogenital Base belonging to Mythical Superstructure, and it can cause major differences between ideological approaches and cause conflict. In the Spanish Civil War there were conflicts between anarchists and Communists and also between Trotsky’s ideas and Stalin’s. Flashpoints occur when differences are taken to be differences that make a difference wherever they occur. Examples include the differences between Catholic and Protestants at various times in history within the Christian religion; and between Muslims and Hindus as an example of differences between different religions.

Then:

- (1)

- Conflicts depend on what difference symbolizes in the Mythical Superstructure’s Primogenital Base;

- (2)

- Substantive beliefs are understood by their ideal values, how they work (criteria of validity), the language they are expressed in, and how they provide perspective to individuals;

- (3)

- The believer can usually discuss substantive beliefs more easily than values, principles or orientations, which are likely to be the assumptions for his (ideological) activities;

- (4)

- Substantial beliefs gain significance and justification from their relation to ideal values, the validity criteria, and the forms of language and perspective.

Based on these criteria and our DIS approach, we propose the following definition of ideology:

Definition 1

We define ideology systemically and we represent it as to the system formed by an object set Sb whose elements are substantive beliefs and whose relational set IR is formed by the set of binary logical abstract relations between substantive beliefs.

4. Variables of an Ideology

Ideologies “are” in the Superstructure, but it is far from our intention to think about Neoplatonist ideas that beliefs exist per se, without material support. Without believers, there is no belief system; but the belief system itself is not coextensive with any given individual Subject or set of Subjects. Ideologies as belief systems have longer lives than Subjects and are capable of such complexity that they would exceed the capacity of a given Subject to detail. Ideologies have the quality of being real and having strong consequences but no specific location, because a Superstructure has not a physical place. According to Rokeach [42], people make their inner feelings become real for others by expressing them in such examples as votes, statements, etc. what they built or tear down, which in turn forms the basis of cooperative (or uncooperative) activity for humans, and the result of which is “Reality”. Ideology is one kind of Reality although not all of it. Ideologies, like units of energy (information), should be thought of as things which have variable, abstract characteristics, not as members of Platonic categories based on similarity. The ideological variables are:

- (1)

- Interrelatedness of their substantive beliefs defines the degree of an ideology (DId) and it is defined as the number m of their logical abstract relations. Logically, some belief systems’ ideologies are more tightly interrelated than others. We can suppose the ideologies and belief systems forming a continuum: . Then: (a) At the right end of the continuum are ideologies that consist of a few highly linked general statements from which a fairly large number of specific propositions can be derived. Confronted by a new situation, the believer may refer to the general rule to determine the stance he should take. Science considered as ideology is an example; (b) At the left end of the continuum are ideologies that consists of sets of rather specific prescriptions and proscriptions (deontical norms) between which there are only weak functional links, although they may be loosely based on one or more assumptions. Confronted by a new situation, the believer receives little guidance from the belief system because there are no general rules to apply, only specific behavioral deontical norms that may not be relevant to the problem at hand. Agrarian religions are typically of this type. They are not true ideologies but proto-ideologies. If DId is defined by m or any number of logical abstract relations between substantive beliefs, then m = 0 defines the nonexistence of a belief system and an ideal ideology that is the contemplated understanding of the totality, that is to say, of the experienced Reality. Consequences: (a) A high DId may inhibit diffusion. It may make an otherwise useful trait inaccessible or too costly by virtue of the baggage that must accompany it. Scientific theories are understood by a small number of experts; (b) If DId is high, social control may be affected on the basis of sanctions and may be taught and learned. Ideologies with a relative high DId seem to rely on rather general internalized deontical norms to maintain social control;

- (2)

- The empirical relevance (ER) is the degree to which individual substantive belief Sbi confronts the empirical world (Reality). The proposition that the velocity is the space crossed by a mobile divided by the time that takes to cross that space has high empirical relevance. The proposition “God’s existence” has low empirical relevance. , being 0 null empirical relevance (Homo neaderthalensis lives at the moment) and 1 total empirical relevance. When beliefs lacking empirical relevance arise in response to pressing strain in the economic or political structures (SB), collective action to solve economic or political problems becomes unlikely. Lack of ER protects the ideology and the social vehicle from controversies arising between the highly differentiated populations of believers;

- (3)

- The ideological function is the actual utility for a group of believing subjects. Ideological function conditions the persistence of the ideology, or the time that it is useful or influences the social structure;

- (4)

- The degree of the willingness of an ideology (WD) is the degree to which an ideology accepts or rejects innovations. . being WD = 0 null acceptance and WD = 1 total acceptance. The ease with which ideologies adapt to changes in their social environment is a major consequence of WD taking innovations. Beliefs with means accepting innovations of all ideological degrees to survive extreme changes in social structure: Shinto in Japan or Roman Catholicism are examples;

- (5)

- The degree of tolerance of an ideology (TD) is the degree with which an ideology accepts or rejects competing ideologies or belief systems. . being TD = 0 indicating total rejection and TD = 1 indicating total acceptance. Some ideologies accept all others as equally valid but simply require different explanations of reality . Others reject all other ideologies as evil , and maintain a position such as one found in revolutionary or fundamentalist movements. Then: (a) High TD seems to be independent of the ideological system and the degree of the willingness (WD); (b) Low TD is fairly strong related with WD; (c) Low TD is fairly strong related with a high relevance (ER). Relevance of highly empirical beliefs to each other is so clear. Therefore . TD has consequences for the ideology: (1) It affects the ease with which the organizational vehicle (social structure) may take alignments with other social structures; (2) It affects the social relationships of the believers;

- (6)

- The degree of commitment demanded by an ideology (DCD) is the intensity of commitment demanded of the believer on the part of the ideology or the type of social vehicle by which the ideology is carried. . being DCD = 0 indicating null commitment demanded and DCD = 1 indicating total adhesion. Then: (a) DCD is not dependent on the ideological system ID, the empirical relevance (ER), the acceptance or innovation (WD) and the tolerance (TD); (b) The degree of commitment demanded (DCD) has consequences for the persistence of the ideology. If an ideology has and cannot motivate the believers to make this commitment, it is not likely to persist for very long. Intentional communities having immediate objective utopias have typically failed in large part for this reason. Revolutionary and fundamentalist ideologies typically demand DCD = 1 of their believers and typically institute procedures, such as party names to both ensure and symbolize that commitment (Crossman, [43]); (c) DCD depends on validation. Ideological systems with low DCD fail or are invalidated slowly as particular beliefs drop from the believers’ repertoire one by one or are relegated to some inactive status. Invalidation of ideological systems with high DCD produces apostates. High DCD ideological systems seem to become invalidated in a painful explosion for their believers, and such ideologies are replaced by an equally high DCD to an ideology opposing the original one. However, reality is not constructed. Reality is encountered and then we construct our knowledge of it. Human Subjects do, in fact, encounter each other in pairs or groups in situations that require them to interact and to develop beliefs and ideologies in the process. They do so, however, as socialized beings with language, including all its values in fact, logic, prescriptions and proscriptions; in the context of the previous work of others; and constrained by endless social restrictions on alternative courses of action. Commitment is the focus of ideologies, because the focus is that Ideas may be good, true, or beautiful in some context of meaning but their goodness, truth, or beauty is not sufficient explanation for their existence, their capacity to be shared, or perpetuated through time. Ideology provides cultural consensus. This consensus may follow from a marginal group. use Using the term broadly, ideology is the system of interlinked ideas, symbols, and beliefs forming the identity of a culture that it justifies itself and from which it draws its energy. This provides the web of rhetoric, and ritual that society uses to persuade or enforce the social structures needed to develop and sustain commitment. These structures also limit alternatives, social isolation, and social insulation through strategies that require heavy involvement of the individual Subject in group-centered activities. Individual commitment is viewed as stemming either from learning and reinforcements for what is learned, or from ideological functions (actual utility) that maintain personality either by compensating for some feeling of inadequacy, or by producing order out of disorder [44,45]. Commitments are validated (or made legitimate) by mechanisms that make them subjectively meaningful to Subjects [46];

- (7)

- The external quality (EQ) of an ideology [47] is the property by which ideologies seem to believers to transcend the social groups that carry them and to have an independent existence of their own.

Then we propose the following definition:

Definition 2:

Ideological system Id during the time of its actual utility or historical time is a nonlinear function of its main characteristics, such as Id = f(DId, ER, WD, TD, DCD) = f(DId, ER, WD, f’(1/WD, ER), DCD) = F(DId, ER, WD, DCD).

An ideology varies in ideological degree (IdD) and its empirical relevance (ER) or in the extent to which it pertains directly to empirical reality. The apparent elusiveness of an ideology derives from four characteristics, all of which result from the fact that while beliefs are created and used by humans, they also have properties that are independent of their human use. As explained by Borhek and Curtis [41]:

- (1)

- Believers conserve their ideologies, that is, they hold to the identity of the ideologies in terms of stable and unchanging ideas, that are independent and make sense of their lives. Ideologies appear to members of a social group as being beyond or above the group, a set of eternal truths, if you like given and agreed by all and therefore true [47]. In reality, beliefs are changeable;

- (2)

- Similarities among substantive beliefs are not necessary parallel structural similarities among ideologies;

- (3)

- The historic source of beliefs (the myths) may, by virtue of their original use, endow them with features that remain stable through millennia of change and this particularly fits them to use in novel contexts;

- (4)

- The most important commonality among a set of substantive beliefs is social structure.

5. Validation of Ideologies

Ideologies face two critical problems in experience, the problem of commitment and the problem of validation. Ideologies persist because work for their adherents and so maintain commitment. However, this means they must seem to be valid. While we may hope that we believe is true, this is often not the case so being committed and having valid beliefs are two different things. Often one acts on the basis of a belief and it takes time to realize it was not viable, and so that it was invalid. We are often in the position of not knowing so we act on our beliefs and then we have a responsibility to see if the beliefs were valid. In psychology, the idea of heuristics refers to shortcuts we take in thinking because they are useful. While they may work, they may not be valid. What may work for a group may not work for the individual and paying attention to what works and does not work following on a belief allows people to change beliefs. However, as we have seen an ideology may require that beliefs do not change.

On account of its structure (within the Doxical Superstructure DS), an ideology may be able to ignore negative evidence in the experience of the social environment H’ but this possibility may be difficult when social conditions (within Structural Base SB) change (See Figure 1). A changing social environment may elicit change in an ideology by changing the social vehicles carrying those changes (Social Institutions), and also with changes in the discourse (Semiotic Forms). Varieties of possibilities are open when an ideology is challenged:

- (1)

- The ideology may be given up, or the commitment may fall;

- (2)

- The ideology may be maintained in the very teeth of stimuli (the jubilance of faith);

- (3)

- The believers may say the context was different so the conflicting events were not relevant or some other form of denial.

The validation of belief is a largely social process. The social power of ideology depends on its external quality. Ideologies seem, to believers, to transcend the social groups that carry them and to have an independent existence of their own [46,47]. For ideologies to persist they must not only motivate commitment through collective utility but also through making the ideology itself seem to be valid in its own right. Perceived consensus is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the social power of ideologies. Therefore, ideological validation is not simply a matter of organizational devices for the maintenance of believer commitment, but also of the social arrangements wherever the abstract system of ideology is accorded validity in terms of its own criteria. The appropriate criteria for determining validity or invalidity are socially defined. Logic and proofs are just as much social products as the ideologies they validate.

Cyclical principle of validation:

An idea is valid if it objectively passes the criterion of validity itself.

Conditions of validation:

- (1)

- Social condition: Criterion of validity is chosen consensually and it is applied through a series of social conventions [46];

- (2)

- First nonsocial condition: Ideology has a logic of its own, which may not lead where powerful members of the social group wanted it to go;

- (3)

- Second nonsocial condition: The pressure of events (physical or semiotic stimuli coming from the stimulus social environment H’) that may pressure believers to relinquish an ideology. For an ideology to survive the pressure of events with enough member-commitment to make it powerful it must receive validation beyond the level of consensus.

The pressure of the events is translated in the form of denotative significances as DS-images on the component subjects of the Dogmatic System of the set of believers belonging to Structural Base.

Main Principle of validation:

The power of an ideology depends on its ability to validate itself in the face of reason for doubt.

The internal evidence of an ideology (IE) are the data which derive from the ideology itself or from any social group or organization to which is attached. For a highly systematic belief system (an ideology), any criticism of any of its principles casts a shadow on the system. Then:

- (1)

- If one of the basic propositions (substantive beliefs) of an ideology is brought under attack, then so is the entire ideology. In consequence, an ideology is at the mercy of its weakest elements;

- (2)

- An ideology has powerful conceptual properties, but these very properties highlight the smallest disagreement and give importance to the logical connections with other items of ideology;

- (3)

- Even if an ideology is entirely non-empirical, it is vulnerable because even one shaken belief can lead to loss of commitment to the entire ideological structure;

- (4)

- Ideologies such as the religious ideologies, with relatively little reference to the empirical world cannot be much affected by external empirical relevance, simply because the events do not bear upon it. The essential substantive belief in the mercy of God can scarcely be challenged by the continuing wretchedness of life;

- (5)

- Nevertheless, concrete ideologies are directly subject to both internal and external evidence;

- (6)

- An abstract ideology is protected from external evidence by its very nature. A cult under fire may be able to preserve its ideology only by retreating to abstraction. Negative external evidence may motivate system-building at the level of the abstract ideology, where internal evidence is far more important;

- (7)

- The separation of the abstract ideology from its concrete expression depends on the ability of believers not affiliated with the association (cult and/or concern) that carried it socially to understand and use it, that is to say, subjects belonging to the Structural Base;

- (8)

- If the validation of an ideology comes from empirical events and the ability to systematically relate propositions according to an internally consistent logic, it can be reconstructed and perpetuated by any social group with only a few hints;

- (9)

- The adaptation of an ideology is some sort of compromise between the need for consensual validation and the need for independence from the associations that carry it.

Consensual validation is about checking one’s perception of reality by comparing one’s own perceptions with others’ perceptions. Consensual validation then, describes the procedures by which human beings verify that their perceptions of the world are very similar to those of others. This normalizes their experience and boosts self-confidence. Consensual validation works too for definitions and meanings. Appreciating the existence of a consensus enables communication and mutual understanding. If there is agreement about a definition, there is integrity. Our experience of Reality is a matter of consensual validation [48]. Our exact internal interpretations of all objects may differ somewhat, but normally we agree sufficiently to communicate meaningfully with each other. Phantasy can be, and often is, as real as the “real world.” Experience of reality is distorted by strong conflicting needs. Group affiliation is sought by individuals in order to maintain a balance between the desire to be part of a group and the desire to be independent These needs balance each other out so that meeting one need means the other is not met, and vice versa. We cannot be both dependent and independent at the same time. We can only experience internal data, so we need to know they are reliable. Public observation of a phenomenon requires specifying what must be done to observe the phenomenon [19]. Public observation, then, is constrained in this way. Maturana specified that science arises when a mechanism is proposed that allows the appearance of the phenomenon under investigation, and also the deduction of other consequences of the mechanism. When these specifications allow both the replication of the phenomenon and the other consequences deduced from the mechanism, we have science. This is one particular account of science, however it shows that great specificity is required and special training. The sharing of such precise ideas is taken for granted and is difficult.

Human reason may be victim of group think, or the need to be part of the herd, and of course this is partly due to the problem of shortcuts (heuristics). People can be wrong and numbers have nothing to do with it. Often it may be that being wrong hasn’t made a difference that makes a difference. Large numbers of people sharing a vice does not turn the vice into a virtue, and errors remain errors even if many believe them [44]. On the other hand, it may be the case that an ideology is identified with the community (or with a consensus), and this community it is not identified with a true socio-political institution based on the land (nation), but is identified with a transcendental principle, personified in the norms of a church, sect or another type of messianic organization. In this case, its effects on the secular political body, which prospers but with which it is not identified are inevitable and predictable destructive. The process of consensual validation then ties the content of ideological beliefs to the social order (existing in the Structural Base). It is established with a circular feedback process:

- (1)

- If the social order remains, then the ideological beliefs must somehow be valid, regardless of the pressure of the events;

- (2)

- If the ideological beliefs are agreed upon by all, then the social order is safe.

Commitment of believers is the result of two opposite forces.

- (1)

- Social support (associations and no militant people), which maintains ideology;

- (2)

- Problems posed by pressure of events which threaten ideology.

When ideology is shaken, further evidence of consensus is required. This can be provided by social rituals of various sorts, which may have any manifest content, but which act to convey additional messages [41]. Each member of a believer group, in publicly identifying himself through ritual is rewarded by the public commitment of the others. Patriotic ceremonies, political meetings, manifestations by the streets of the cities, transfers and public religious ceremonies are classic examples of this. Such ceremonies typically involve a formal restatement of the ideal ideology in speeches, as well as rituals that give opportunities for individual reaffirmation of commitment. For Durkheim [47], ideological behavior could be rendered sociologically intelligible by assuming an identity between societies and the object of worship. The ideal of all totalitarian ideology is the total identity between the civil society and the ideological thought, that is to say, the establishment of unique thought without fissures. Thus, consensual validation and validation according to an abstract ideal (Ideal Mythical Superstructure) are indistinguishable in the extreme case. If a certain ideology has as a sole raison d’être the affirmation of group membership (fundamentalist ideologies), no amount of logical or empirical proof is even relevant to validation, though proofs may in fact be emphasized as part of the ritual of group life.

We have the following examples of consensual validation in actual ideologies:

- (1)

- False patriotism consists in following a government no matter what is says;

- (2)

- Neo-conservatism is about maintaining the status quo;

- (3)

- Radical Progressivism is the belief that social reality can change undermining the foundations of a millenarian culture;

- (4)

- Shallow utilitarianism is about maintaining that the majority views should be obeyed. It is a case of following the herd and may be identified with groupthink. Erich Fromm [44] called it “the pathology of normalcy” and argued it was due to consensual validation.

Islamic fundamentalism. Like many religions, behavior is strictly prescribed in Islam. Beliefs and actions are consensually validated throughout the geography of the umma. There is no need to question, the laws are well developed and precise. Such certainty provides answers to the sense of perspective provided by this (religious) ideology. We must remember that the jihad is about the struggle and especially the struggle concerning self development.

6. Conclusions

We have identified a mechanism to account for the emergence of ideologies and belief systems of increasing complexity [1]. In their diverse nature ideologies show wide variation in terms of their requirements for supporting evidence. Broadly however, they may be said to rest on a theoretical blindness that obscures features that may be important for a fuller account of experience [10]. Even science focusing on theoretically derived hypotheses may be considered an ideology. However, science also provides and insists on a way of checking the replicability of what we know with procedures for inter-subjective agreement [19]. In the present paper, we have identified a series of variables from varied sources that are asserted to influence the importance of ideologies and belief systems for individual decision making and so for identity. We propose this list of considerations as a basis for developing algorithms to study the impact of different ideologies on decision making and behavior.

- (1)

- An ideology is a systemic set of beliefs;

- (2)

- Ideologies are not a collection of accidental facts considered separately and referred to an underlying history and are: (a) Thoughts about our own behaviors, lives and courses of action; (b) A mental impression—something that is abstract in our heads—rather than a concrete thing; (c) A system of belief. Just beliefs—non-unchangeable ultimate truths about the way the world should be;

- (3)

- Ideology has different meanings. These meanings all arise from ideologies being a form of world view, or way of viewing experience. As such ideologies filter experience and may be resistant to evidence on the contrary, but while intact form an integral part of the individual’s identity and of the mechanism through which the individual relates to the society in which he lives. As such ideologies are often highly resistant to reasonable discussion and may be intransigent as indicated in what follows;

- (4)

- The greater the ideological degree (Did), the greater the impact of negative evidence for the whole ideology;

- (5)

- The less the degree of empirical relevance, the less the importance of external evidence (pressure of events), but the greater the importance of internal evidence;

- (6)

- The supra-social form of an ideology derives most significantly from its abstract ideal form belonging to the Mythical Superstructure. The current social influence of an ideology derives of its concrete form belonging to the Doxical Superstructure;

- (7)

- The more systematic and empirically relevant an ideology is, the greater the feasibility of preserving it as an abstract ideal apart from a given concrete expression;

- (8)

- The greater the Ideological degree (DId) and the greater the degree of empiricism, the less the reliance on internal evidence and the greater the reliance of external evidence;

- (9)

- The extent of commitment to ideology varies directly with the amount of consensual validation available, and inversely with the pressure of events.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Piaget, J. Piaget’s theory. In Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology; Mussen, P.H., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 703–732. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. Neoconstructivism: The New Science of Cognitive Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tobias, S.; Duffy, T.M. Constructivist Instruction: Success or Failure; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton, T. Ideology: An Introduction; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, W.A. On the Concept of Ideology in Political Science. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1972, 66, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minar, D.M. Ideology and Political Behavior. Midwest J. Political Sci. 1961, 5, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranston, M. Ideology; Encyclopedia Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Duncker, Ch. Kritische Reflexionen des Ideologie Begriffes; Turnshare: London, UK, 2006. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Althusser, J.L. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays; New Left Books: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Strauss and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.; Converse, P.E.; Miller, W.E.; Stokes, D.E. The American Voter; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz, A.I. The Disappearing Center: Engaged Citizens, Polarization, and American Democracy; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T.; Amodio, D.M. Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence. Motiv. Emot. 2012, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsby, H. The Domain of Ideologies: A Study of the Origin, Structure and Development of Ideologies; McLellan, W., Ed.; Collaboration with the Social Science Association: Glasgow, UK, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Theory of the Moral Life; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Walford, G. Ideologies and Their Functions: A Study in Systematic Ideology; The Bookshop: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Walford, G. Systematic Ideology, the Work of Harold Walsby. Sci. Public Policy 1983, 10, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, G. Beyond Ecology. Sci. Public Policy 1983, 1, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R. Reality: The Search for Objectivity or the Quest for a Compelling Argument. Irish J. Psychol. 1988, 9, 25–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S. Enforcing Social Conformity: A Theory of Authoritarism. Polit. Psychol. 2003, 24, 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. The Long Revolution; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Marxism and Literature, Marxist Introductions; Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsci, A. Selection from the Prison Notebooks; Hoare, Q., Nowell-Smith, G., Eds.; International Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. The German Ideology; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pecheux, M. Language, Semantics and Ideology; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rudé, G. Ideology and Popular Protest; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Vives-Maciá, F.; Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Berend, D. An introduction to Alysidal Algebra I. Kybernetes 2012, 41, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Vives-Maciá, F.; Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Berend, D. An introduction to Alysidal Algebra II. Kybernetes 2012, 41, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. An introduction to Alysidal Algebra III. Kybernetes 2012, 41, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. Topological Structures of Complex Belief Systems. Complexity 2013, 19, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J. Topological Structures of Complex Belief Systems (II): Textual materialization. Complexity 2013, 19, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. Semiotic vision of ideologies. Found. Sci. 2014, 19, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. Model, Metamodel and Topology. Found. Sci. 2014, 19, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. Ecosustainability as Ideology. Am. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. Linguistic Systems and Knowledge of Reality. Am. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 2, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L. Myth, language and complex ideologies. Complexity 2014, 20, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Lloret-Climent, M. Ideological Complex Systems: Mathematical Theory. Complexity 2015, 21, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Lloret-Climent, M. Mythical Systems: Mathematic and Logical Theory. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 2015, 44, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nescolarde-Selva, J.; Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Gash, H. Language, Values, and Ideology in Complex Human Societies. Cybern. Syst. 2015, 46, 390–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Nescolarde-Selva, J. Mathematics and Semiotical Theory of Ideological Systems; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbruken, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Borhek, J.T.; Curtis, R.F. A Sociology of Belief; Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. Beliefs, Attitudes and Values; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman, R.H.S. The God That Failed; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. The Sane Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, A.F.C. Sociology of Religion; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality; Garden City, Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselin, B. The Creative Process; New American Library: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).