Subsample Analysis of Oil Revenue Shocks and Macroeconomic Policy Transmission

Abstract

1. Introduction

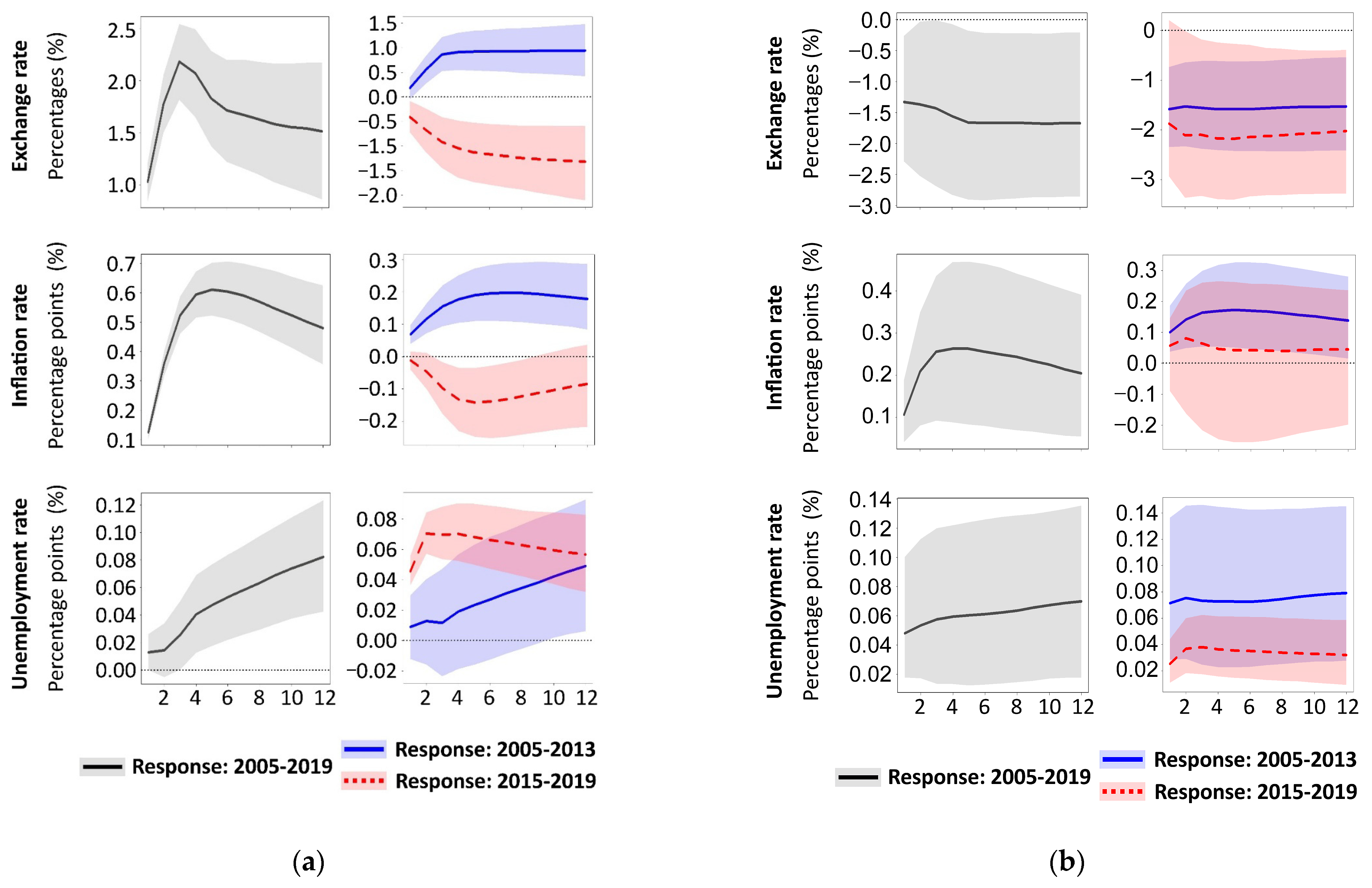

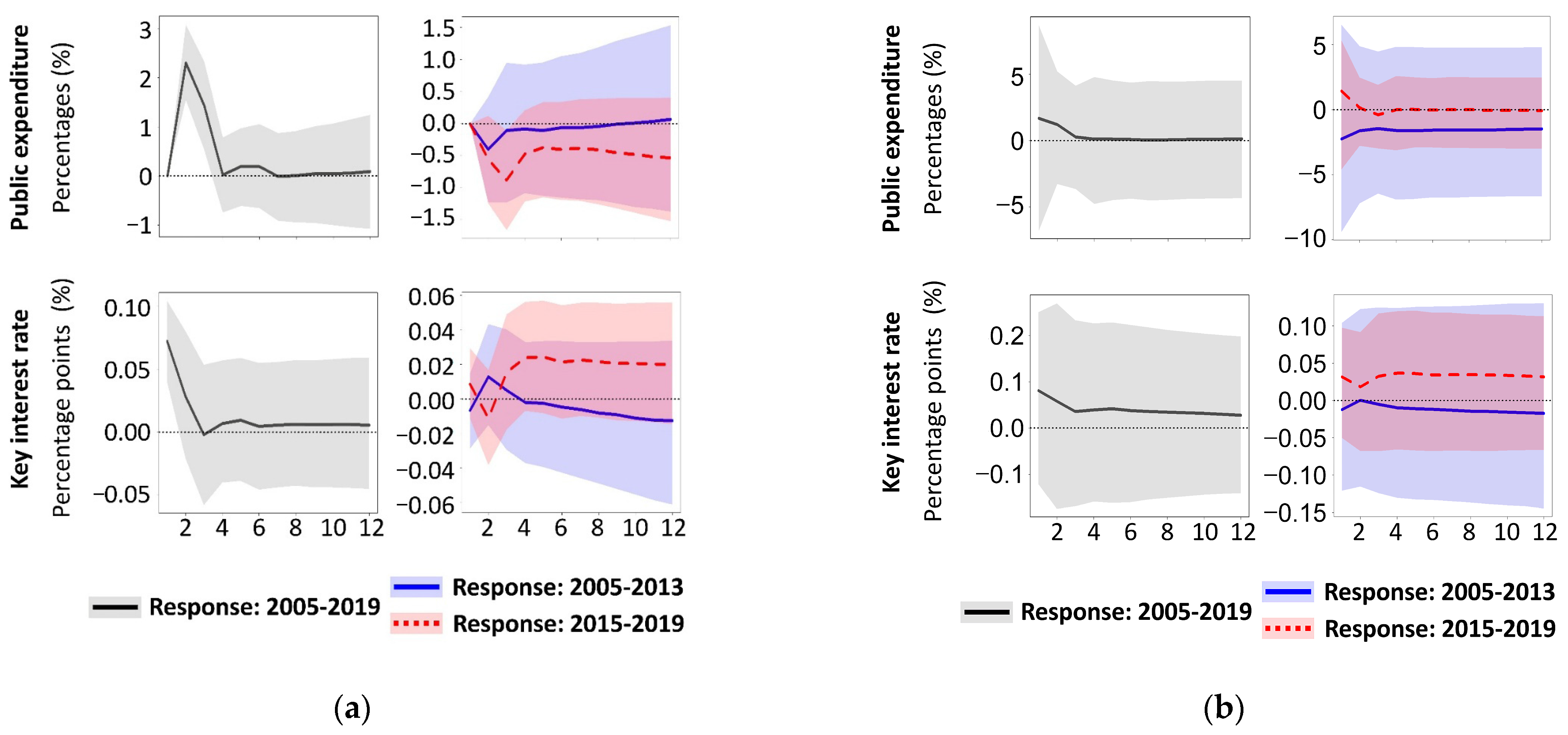

- The combined model (2005–2019)—serves as a basis for comparison

- The pre-2014 model (2005–2013)—reflects the period with reactive fiscal and monetary policies and Russian fast economic development.

- The post-2014 model (2015–2019)—takes into account the inflation targeting regime and the transition to fiscal policy consolidation with structural shifts in the Russian macroeconomy.

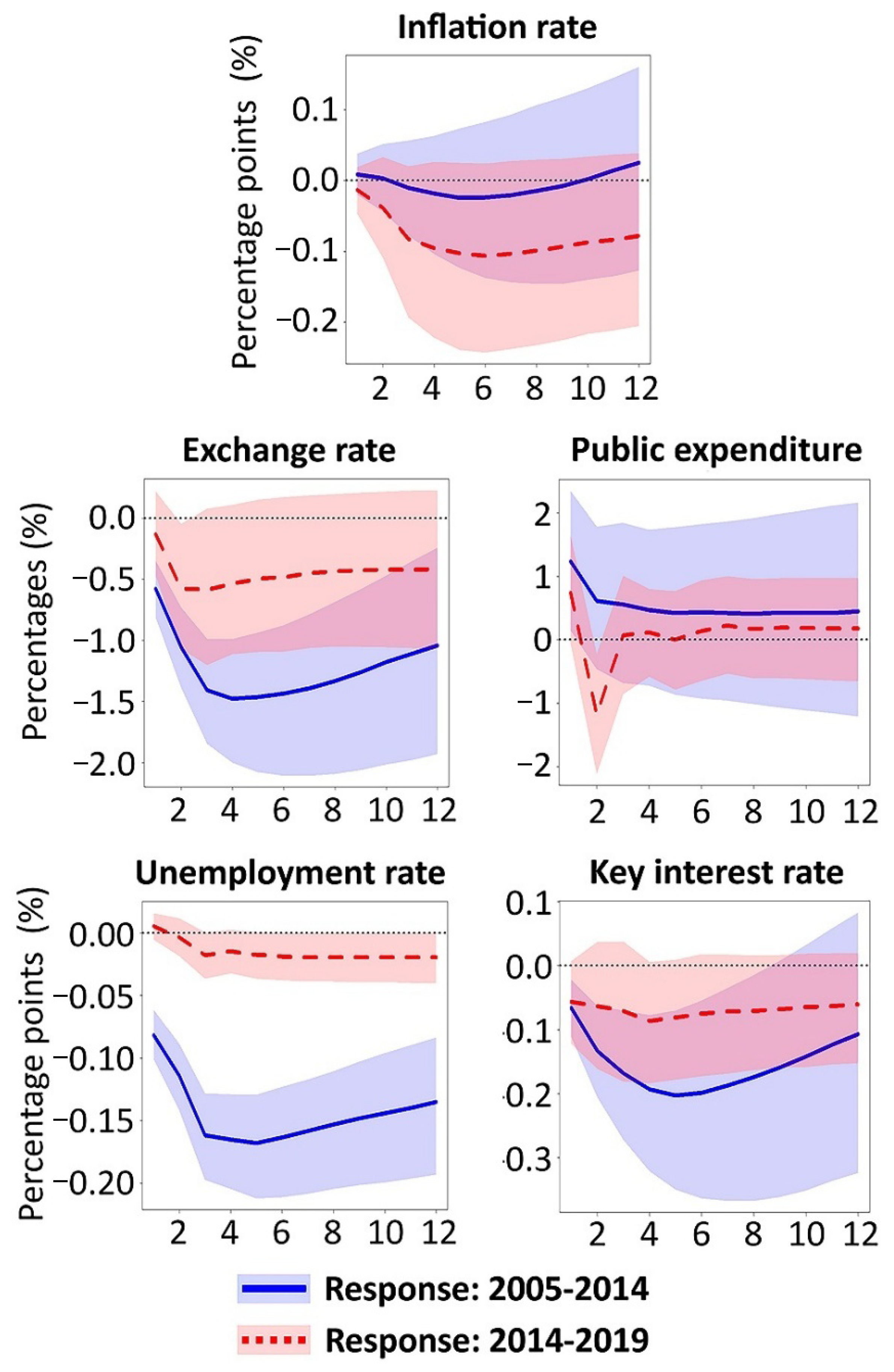

- Before 2014, macroeconomic policy (government expenditure and key interest rate) demonstrated predominantly procyclical responses to shocks in oil revenues. Since 2014, there has been an increase in countercyclicality in the response of macroeconomic policy to oil revenue booms.

- Russia’s economic dependence on oil diminished after 2014, as evidenced by the exchange rate of domestic currency and the unemployment rate.

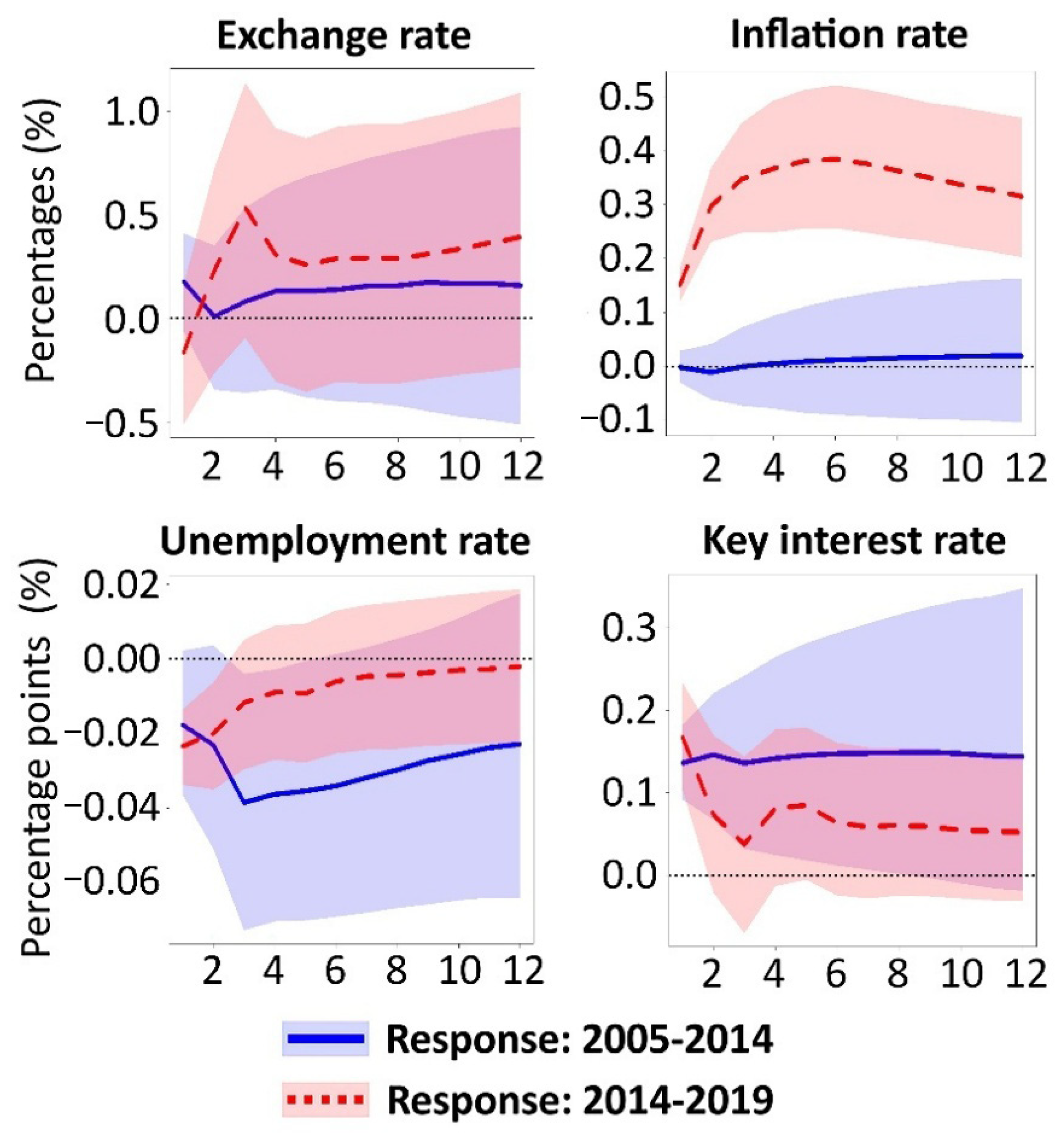

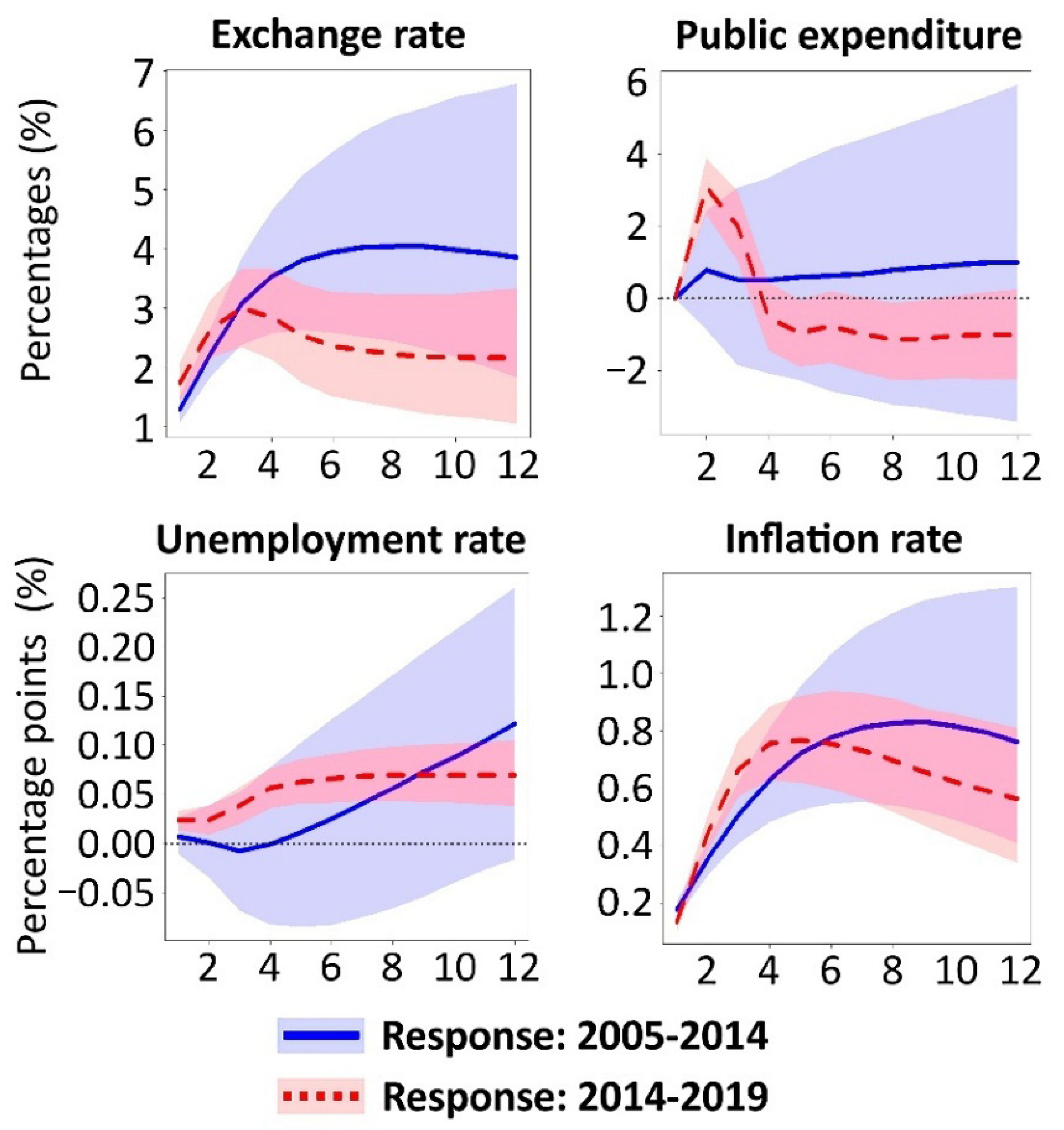

- After 2014, fiscal expansion has shifted from an anti-inflationary tool into an inflationary driver and a catalyst for currency depreciation.

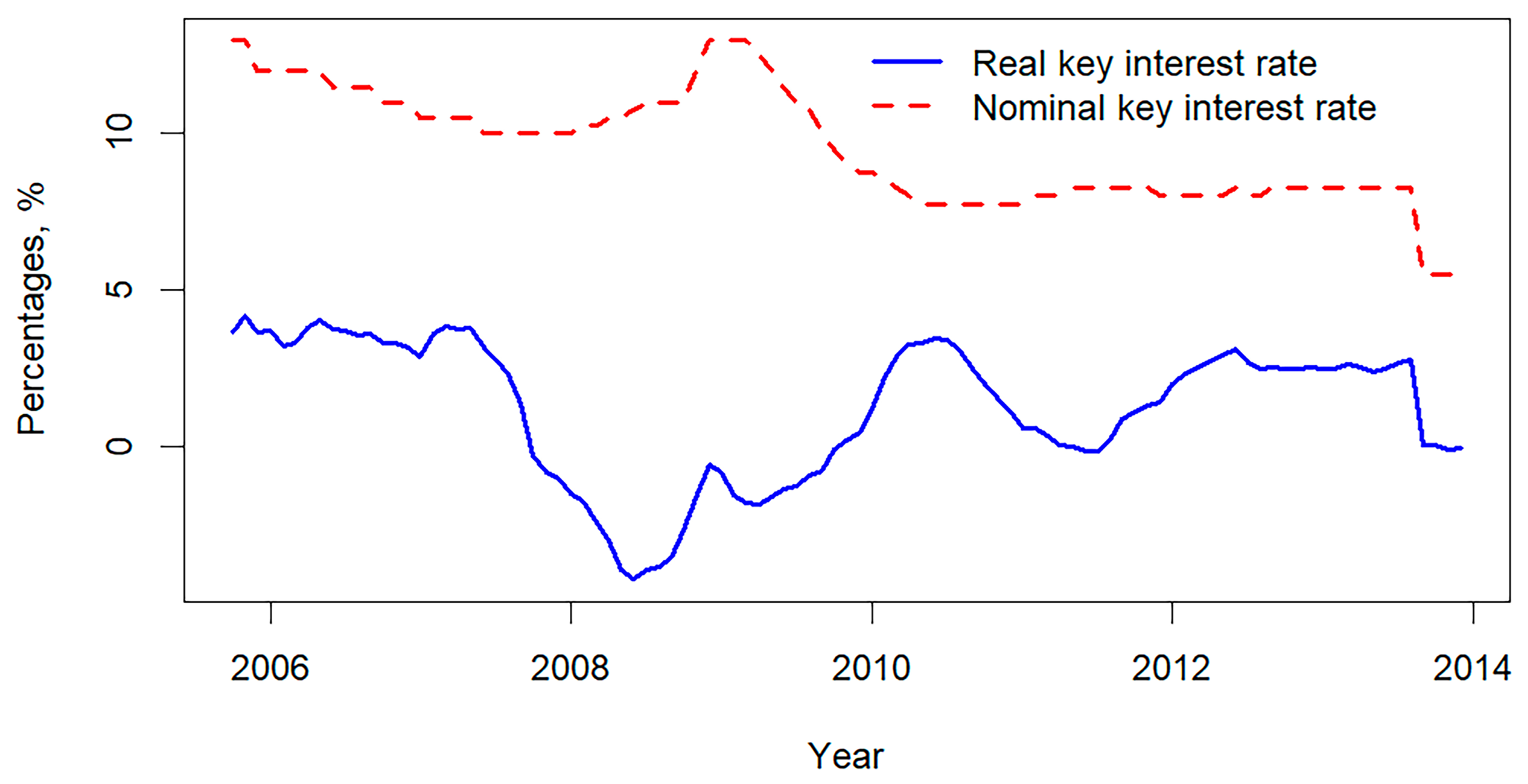

- After 2014, the monetary policy stance became explicitly anti-inflationary.

- Post-2014, fiscal policy became increasingly constrained by the Central Bank’s more dominant inflation targeting regime.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Baseline Model

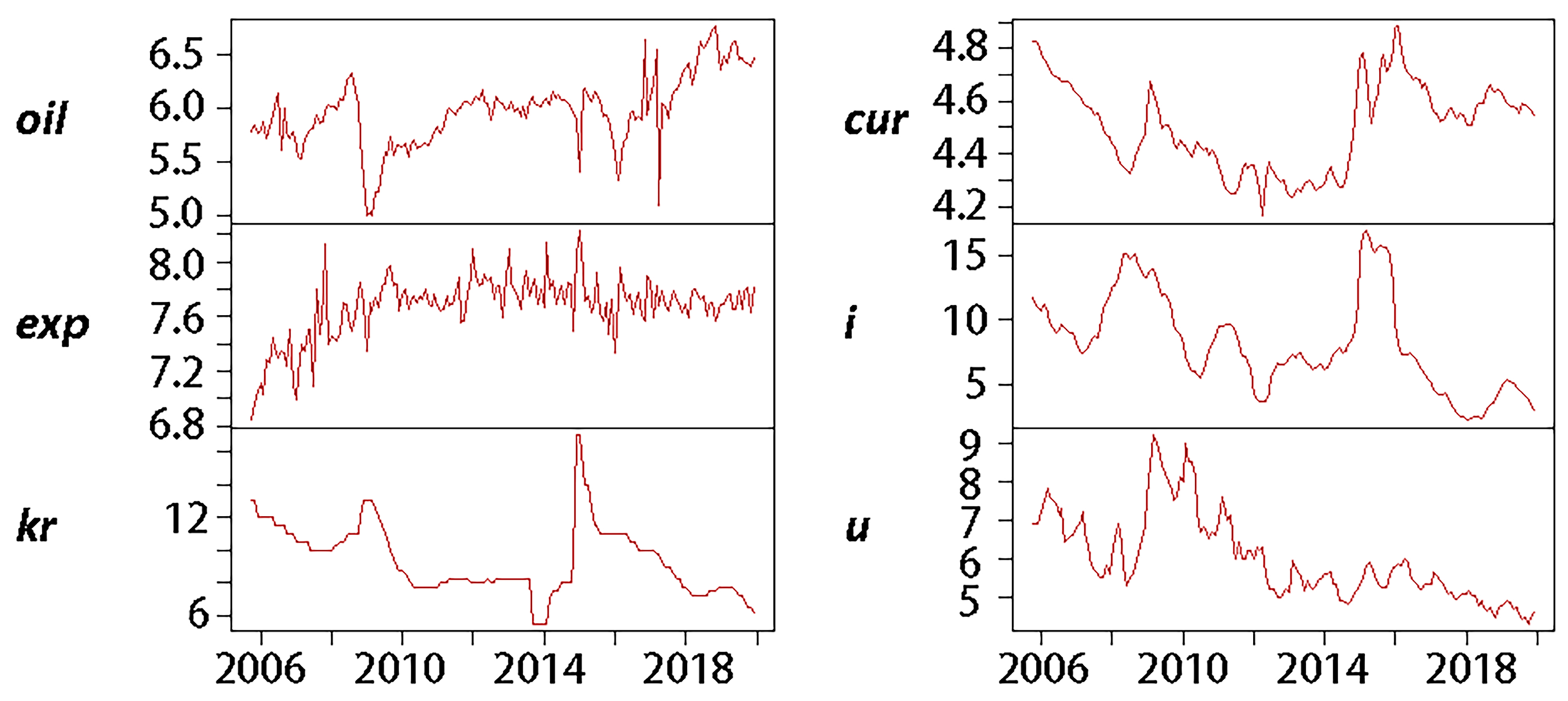

2.2. Model Variables Justification

2.3. Identification of Structural Shocks

2.3.1. Cholesky Factorization

2.3.2. Sign and Zero Restriction

2.4. Prior Specification

2.5. The Estimation Procedure

3. Results

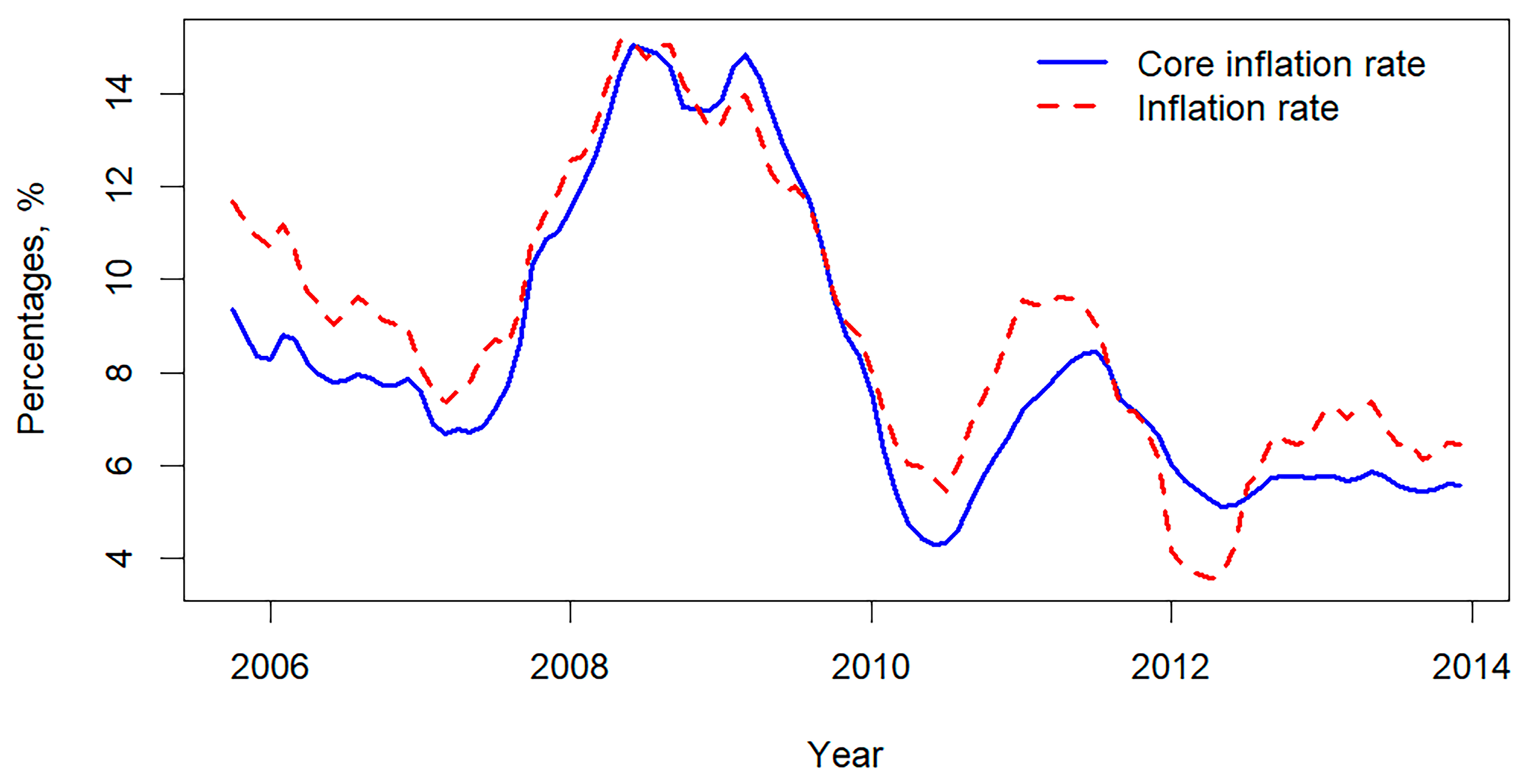

3.1. Statistical Evidence of a Structural Break in the Russian Economy in 2014

3.2. The Macroeconomic Effect of Crude Oil in Russia

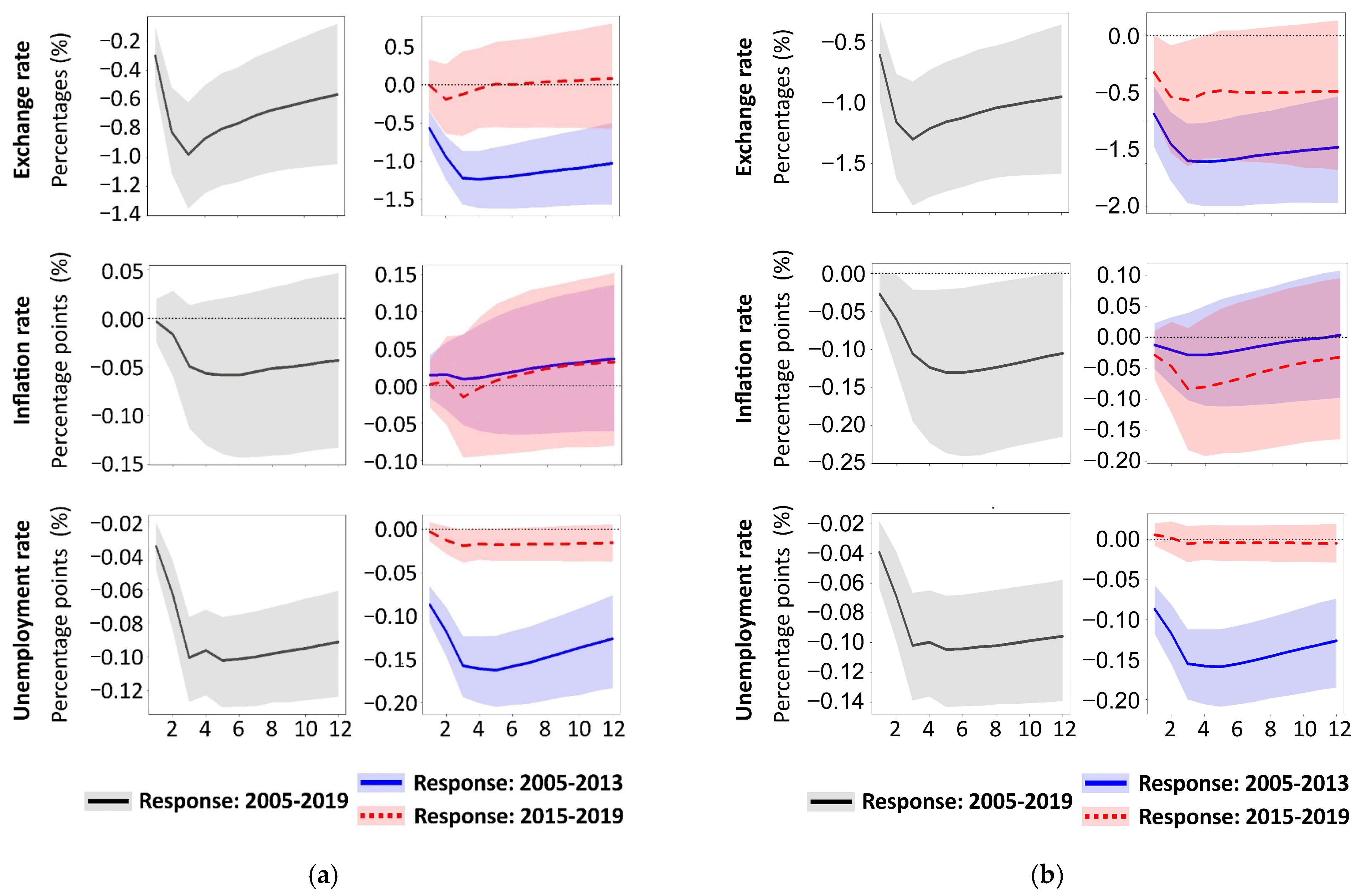

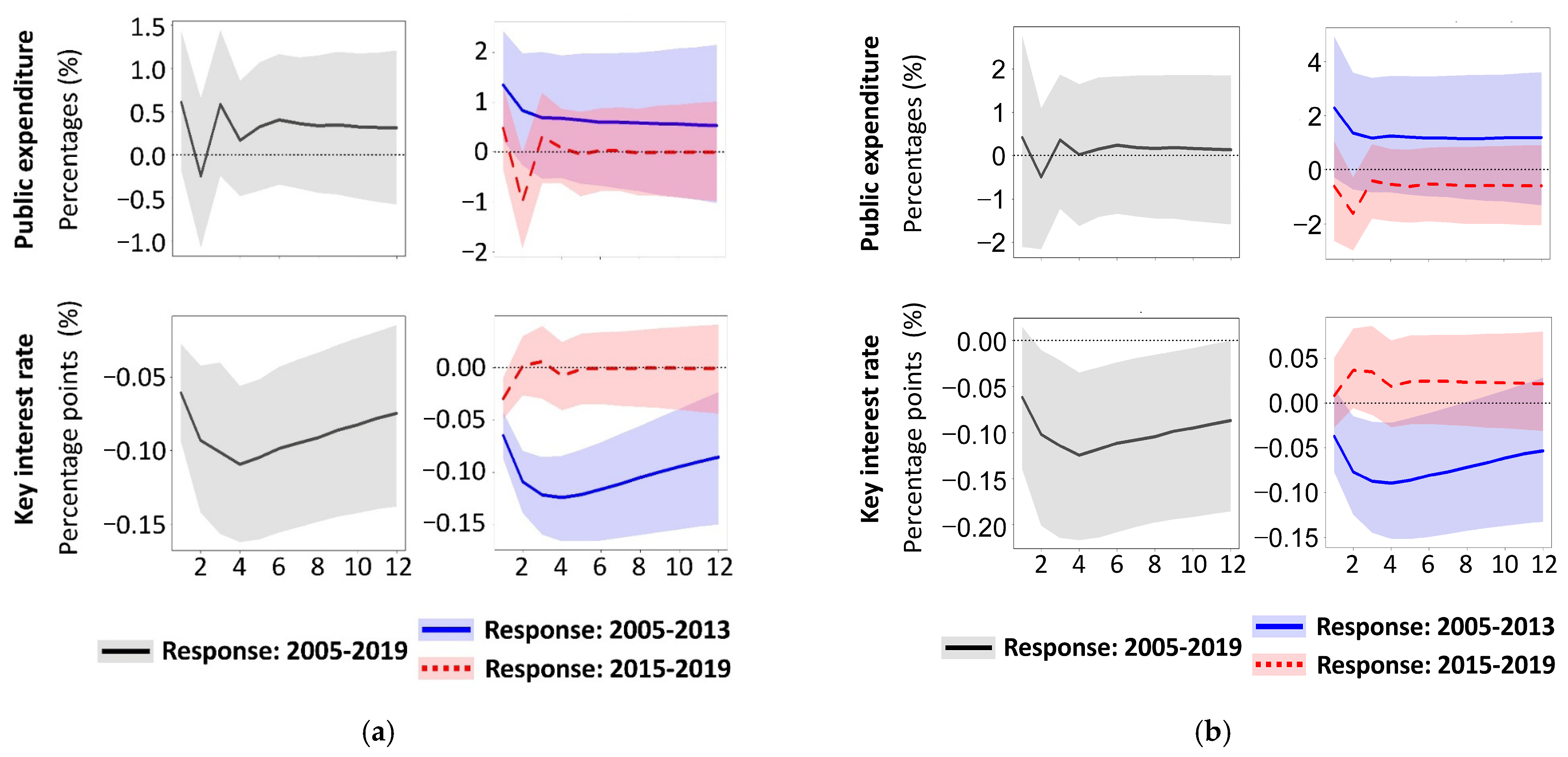

3.3. The Impact of Crude Oil on Russia’s Macroeconomic Policy

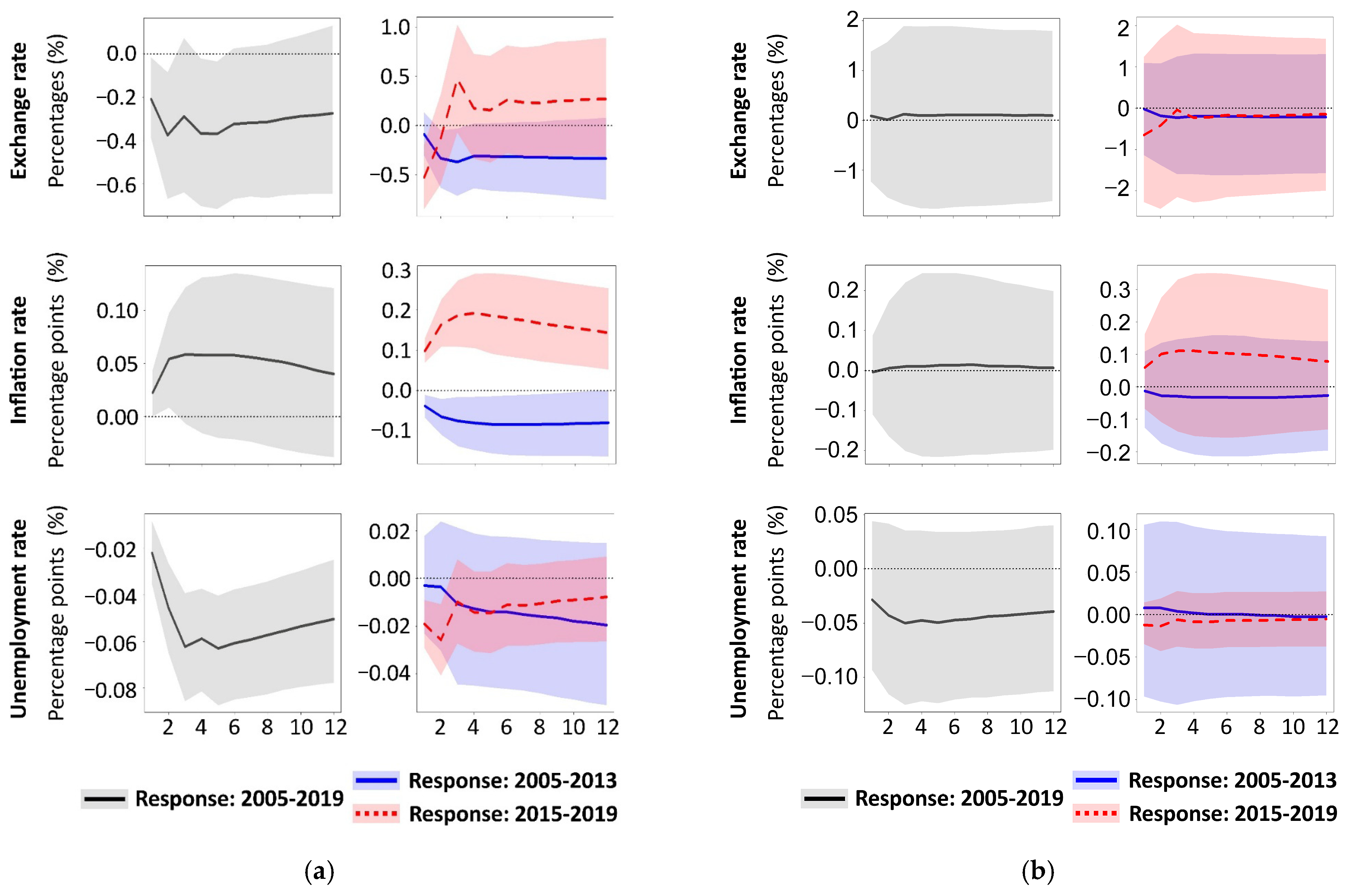

3.4. Economic Consequences of Russia’s Macroeconomic Policy Decisions

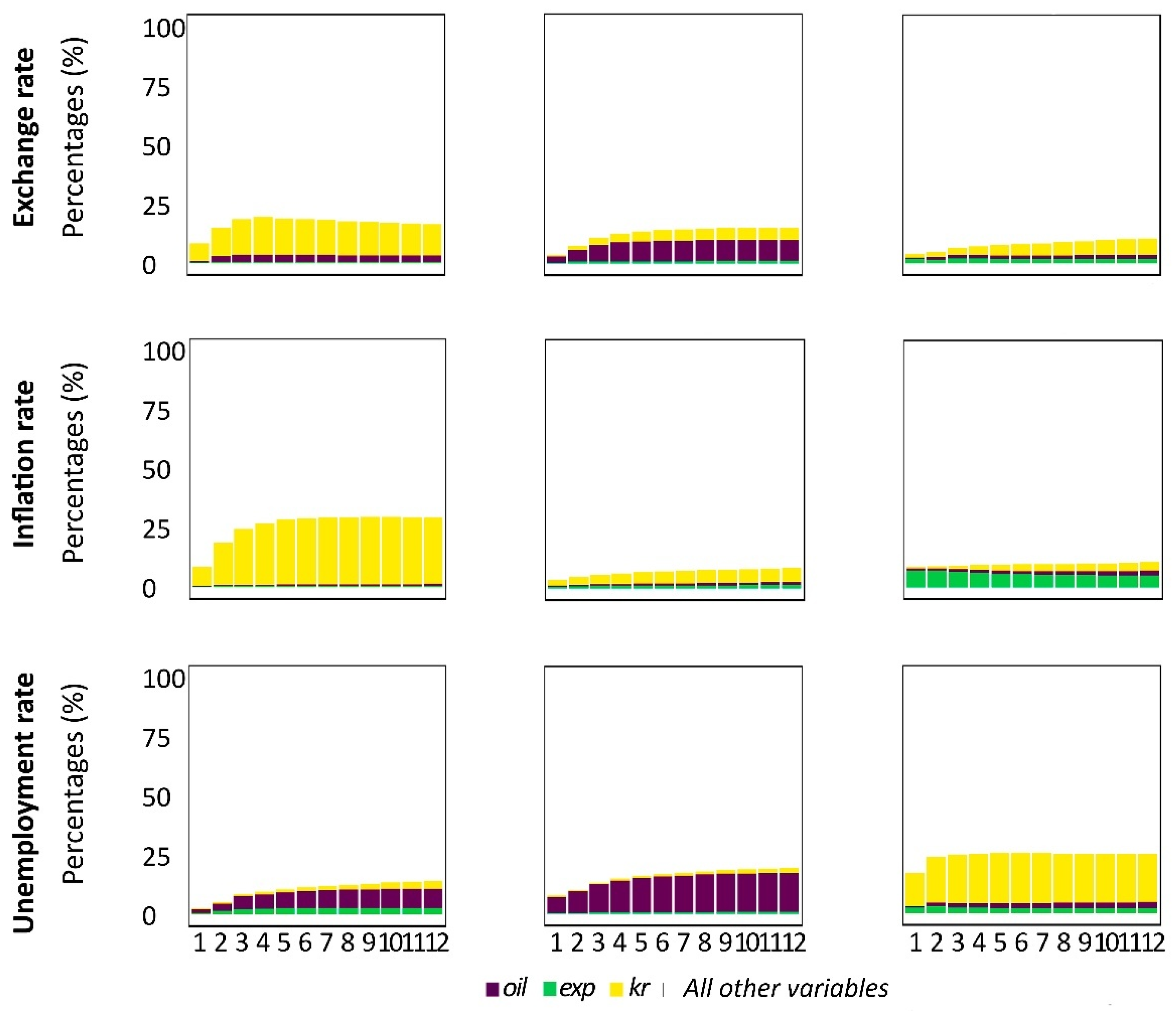

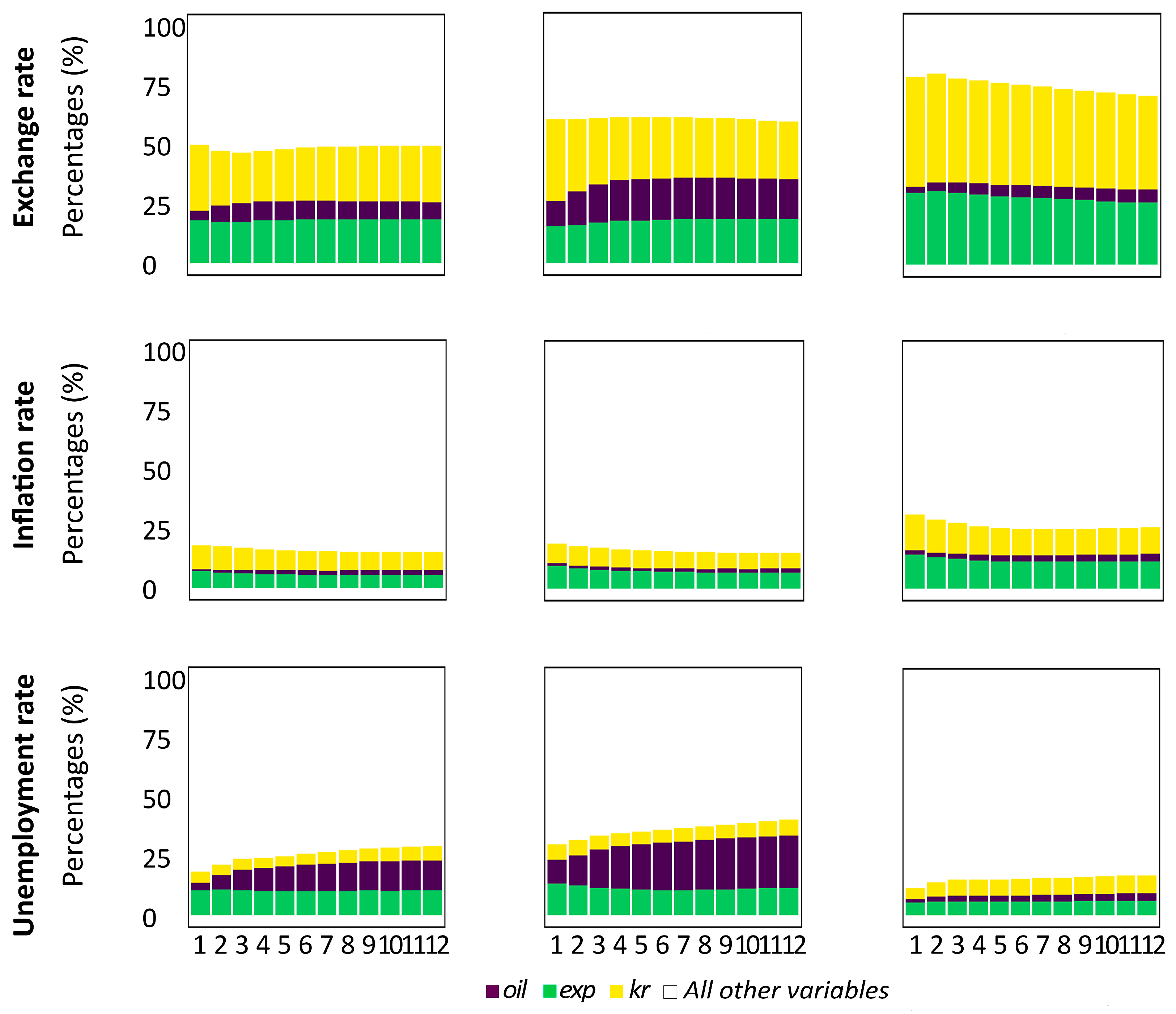

3.5. Contributions of Shocks to the Variability of Variables

3.6. Robust Check

3.6.1. 2014–2019 Additional BVAR Model

3.6.2. 2005–2014 Additional BVAR Model

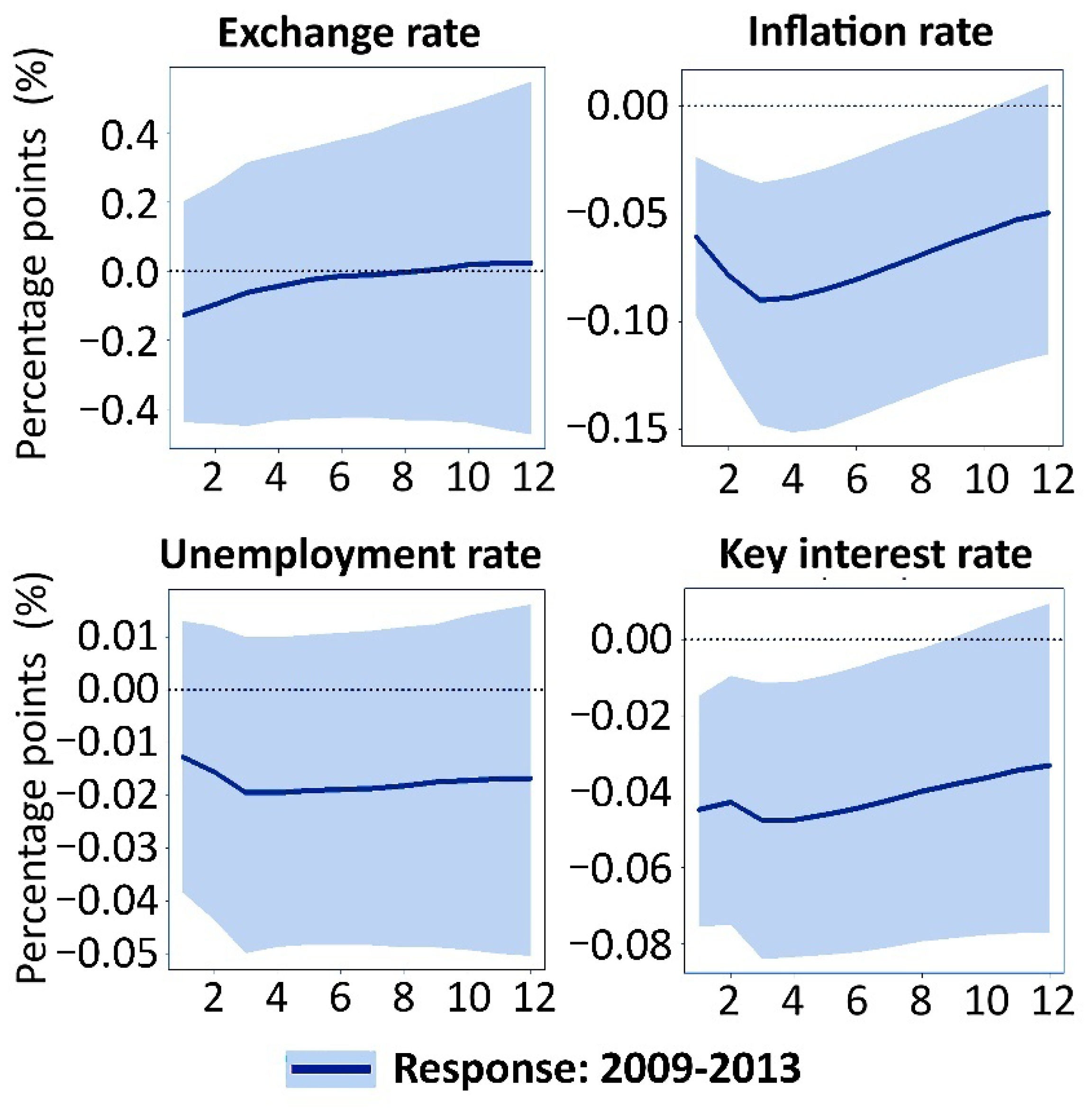

3.6.3. 2009–2013 Additional BVAR Model

3.6.4. 2005–2013 Additional BVAR Extended Model

4. Discussion

- After 2014, fiscal expansion shifted from an anti-inflationary tool to an inflationary driver and a depreciating force on the national currency.

- After 2014, the monetary policy’s tight stance became explicitly anti-inflationary.

- Post-2014, fiscal policy became increasingly constrained by the central bank’s more dominant inflation targeting regime.

- Russia’s economic dependence on oil diminished after 2014, as evidenced by the exchange rate of its domestic currency and the unemployment rate.

- Macroeconomic policy (government expenditure and key interest rate) shifted from procyclical to countercyclical in response to oil revenue shocks after 2014.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BVAR | Bayesian vector autoregression |

| FEVD | Forecast error variance decomposition |

| MCMC | Markov chain Monte Carlo |

| SOC | Sum of coefficients |

| SUR | Single-unit root |

| VAR | Vector autoregression |

| PPB | Posterior probability bands |

| ML | Marginal likelihood |

| ESS | Effective sample size |

| ADF | Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| KPSS | Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Mean | Median | SD | Variance | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil revenue | 5.973 | 6.002 | 0.335 | 0.113 | 4.995 | 6.763 | −0.243 | 0.564 |

| Total expenditure | 7.672 | 7.701 | 0.226 | 0.051 | 6.846 | 8.227 | −1.070 | 1.869 |

| Key rate | 9.377 | 8.750 | 2.096 | 4.391 | 5.500 | 17.000 | 0.753 | 0.849 |

| Exchange rate | 4.504 | 4.526 | 0.166 | 0.028 | 4.165 | 4.883 | 0.086 | −0.987 |

| Inflation | 8.134 | 7.384 | 3.764 | 14.165 | 2.197 | 16.926 | 0.523 | −0.558 |

| Unemployment | 5.978 | 5.620 | 1.101 | 1.212 | 4.290 | 9.200 | 0.892 | 0.057 |

| Mean | Median | SD | Variance | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil revenue | 5.840 | 5.889 | 0.263 | 0.069 | 4.995 | 6.331 | −1.086 | 1.439 |

| Total expenditure | 7.626 | 7.688 | 0.264 | 0.070 | 6.836 | 8.117 | −0.863 | 0.426 |

| Key rate | 9.525 | 9.000 | 1.856 | 3.446 | 5.500 | 13.000 | 0.120 | −0.754 |

| Exchange rate | 4.444 | 4.420 | 0.161 | 0.026 | 4.165 | 4.826 | 0.629 | −0.596 |

| Inflation | 9.023 | 8.797 | 2.958 | 8.750 | 3.574 | 15.144 | 0.366 | −0.660 |

| Unemployment | 6.578 | 6.500 | 1.054 | 1.111 | 5.000 | 9.200 | 0.493 | −0.588 |

| Mean | Median | SD | Variance | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil revenue | 6.175 | 6.179 | 0.369 | 0.136 | 5.092 | 6.763 | −0.691 | 0.108 |

| Total expenditure | 7.721 | 7.719 | 0.118 | 0.014 | 7.379 | 8.270 | 1.427 | 6.677 |

| Key rate | 9.358 | 9.000 | 2.235 | 4.994 | 6.250 | 17.000 | 1.035 | 1.077 |

| Exchange rate | 4.628 | 4.593 | 0.092 | 0.008 | 4.510 | 4.883 | 0.907 | 0.105 |

| Inflation | 6.734 | 4.829 | 4.751 | 22.575 | 2.197 | 16.926 | 1.121 | −0.287 |

| Unemployment | 5.148 | 5.170 | 0.440 | 0.194 | 4.290 | 5.990 | 0.075 | −0.977 |

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

| Variable | ADF Test (Levels) | KPSS Test (Levels) | Stationary in Levels? | ADF Test (First Diff.) | KPSS Test (First Diff.) | I(d) Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oil | −3.750 (0.023) | 1.4998 (0.01) | No | −6.476 (0.01) | 0.027 (0.1) | I(1) |

| exp | −4.245 | 1.1603 (0.01) | No | −7.203 (0.01) | 0.0359 (0.1) | I(1) |

| kr | −2.722 (0.275) | 0.7089 (0.013) | No | −5.925 (0.01) | 0.048 (0.1) | I(1) |

| cur | −2.4611 (0.384) | 0.5921 (0.023) | No | −5.467 (0.01) | 0.178 (0.1) | I(1) |

| i | −2.907 (0.197) | 1.0517 (0.01) | No | −3.890 (0.016) | 0.053 (0.1) | I(1) |

| u | −2.590 (0.330) | 2.0982 (0.01) | No | −6.607 (0.01) | 0.030 (0.1) | I(1) |

| Null Hypothesis (H0) | Alternative Hypothesis (H1) | Eigenvalue (λ) | Max-Eigen Statistic | 10% Critical Value | 5% Critical Value | 1% Critical Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r = 0 | r = 1 | 0.2663 | 52.03 | 40.91 | 43.97 | 49.51 | Reject H0 |

| r ≤ 1 | r = 2 | 0.145 | 26.31 | 34.75 | 37.52 | 42.36 | Accept H0 |

| r ≤ 2 | r = 3 | 0.094 | 16.59 | 29.12 | 31.46 | 36.65 | Accept H0 |

| r ≤ 3 | r = 4 | 0.0907 | 15.97 | 23.11 | 25.54 | 30.34 | Accept H0 |

| r ≤ 4 | r = 5 | 0.0687 | 11.95 | 16.85 | 18.96 | 23.65 | Accept H0 |

| r ≤ 5 | r = 6 | 0.0539 | 9.31 | 10.49 | 12.25 | 16.26 | Accept H0 |

Appendix A.4

| Parameters | BVAR (2005–2019) | BVAR (2005–2013) | BVAR (2015–2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.552 | 0.344 | 0.742 | |

| 0.199 | 0.321 | 0.220 | |

| 0.071 | 0.108 | 0.280 | |

| Max autocorrelation of | 0.046 | 0.019 | 0.022 |

| Accepted draws | 0.246 | 0.289 | 0.249 |

| ESS | 5065.83 | 5000 | 4907.643 |

| Coefficients convergence (Gelman–Rubin on three independent chains) | Point = 1 | Point = 1 | Point = 1 |

| ML | 31.295 | 86.213 | 84.383 |

| Parameters | BVAR (2009–2013) | BVAR (2005–2014) | BVAR (2014–2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.315 | 0.416 | 0.642 | |

| 0.689 | 0.352 | 0.175 | |

| 0.549 | 0.089 | 0.087 | |

| Max autocorrelation of | 0.076 | 0.0244 | 0.023 |

| Accepted draws | 0.246 | 0.255 | 0.314 |

| ESS | 3768.533 | 5011.513 | 5127.79 |

| Coefficients convergence (Gelman–Rubin on three independent chains) | Point = 1 | Point = 1 | Point = 1 |

| ML | 74.129 | 19.396 | 1.139 |

Appendix A.5

| Studies | Country | Method | Results | Data Span |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russia (2019) [1] | Russia | Vector autoregression model (VAR) | Oil dependency increased in 2016 | 1993–2016 |

| Drygalla (2023) [3] | Russia | Smal open economy BVAR | Oil dependency | 2001–2015 |

| Nyangarika and Tang (2018) [2] | Russia | Vector autoregression model (VAR) | Oil dependency | 1991–2016 |

| Idrisov et al. (2015) [7] | Russia | Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model | Oil dependency reduced. Oil price effect is short term | 2000–2014 |

| Ito (2017) [4] | Russia | Vector error correction model (VECM) | Oil dependency. Oil price effect is short term | 2003–2013 |

| Benedictow et al. (2013) [6] | Russia | Macro econometric model with investment-saving and liquidity-money (IS-LM) characteristics | Oil dependency | 1995–2008 |

| Balashova and Seretis (2020) [7] | Russia | Vector autoregression model (VAR) | Oil dependency. Oil price effect is short term | 2000–2018 |

| Lomonosov et al. (2021) [8] | Russia | Bayesian vector autoregression model (BVAR) | Oil price impact matters only in times of world activity rise. | 1999–2019 |

| Wang et al. (2022) [9] | Russia, Canada. | Bootstrap subsample rolling-window causality test (BSRWC) | Oil price effect on unemployment in specific periods. | 2000–2020 |

| Su et al. (2020) [10] | Russia | Bootstrap rolling window granger causality test (BRWGC) | Resource curse in Russia. oil price negatively affects wage arrears. | 1997–2019 |

| Yang et al. (2021) [11] | Russia | Nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag model (NARDL) | Oil blessing in Russia | 1988–2019 |

| Studies | Country | Method | Results | Data Span |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alekhina and Yoshio (2019) [1] | Russia | Vector autoregression model (VAR) | Implicitly shows key interest rate to be procyclical | 1993–2016 |

| Gurvich (2023) [3] | Russia | Smal open economy Bayesian vector autoregression model (BVAR) | Implicitly shows key interest rate to be procyclical | 2001–2015 |

| Ito (2017) [4] | Russia | Vector error correction model (VECM) | Implicitly shows government expenditure to be procyclical | 2003–2013 |

| Benedictow et al. (2013) [6] | Russia | Macro econometric model with investment-saving and liquidity-money (IS-LM) characteristics | Russian fiscal policy countercyclical | 1995–2008 |

| Gurvich et al. (2009) [18] | Venezuela, Iran, Kazakhstan, Norway, Russia | An econometric regression-type model with lags and causality tests. | Russian fiscal policy procyclical | 1995–2006 |

| Tuzova and Qayum (2016) [19] | Russia | Vector autoregression model (VAR) | Implicitly shows government expenditure to be procyclical | 1999–2015 |

| Tyunova (2018) [33] | Russia | Markov switching vector autoregression model | Procyclicality of key interest rate. CB faces dilemma and tolerates inflation during oil price drops | 2003–2016 |

| Çiçekçi and Gaygısız (2023) [20] | Panel data for 34 oil-exporting and oil-importing countries | Autoregressive moving average—exponential generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity model (ARMA(1,1)-EGARCH) | Fiscal procyclicality in Russia | 1984–2015 |

| Tyunova (2019) [21] | Russia | Bayesian vector autoregression model (BVAR) | Countercyclical monetary policy after 2014 due to inflation targeting | 2000–2019 |

| Sohag et al. (2022) [17] | Russia | Dynamic spatial autoregressive distributed lag model (DSARDL) | Fiscal counter cyclical features at managing fiscal consolidation. | 2011–2021 |

| Jin and Xiong (2021) [22] | BRICS | Threshold Bayesian vector autoregression model (BVAR) | Procyclicality of key interest rate. CB faces tradeoffs between price stability and macro stability | 2000–2019 |

Appendix B

| The Percentage Contribution (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oil | exp | kr | cur | i | u | |

| exp (2009–2013) | 1.06 [0.52, 2.02] | 96.81 [98.47, 93.89] | 0.66 [0.32, 1.27] | 0.15 [0.07, 0.30] | 0.80 [0.38, 1.51] | 0.52 [0.25, 1.02] |

| exp (2005–2014) | 1.22 [0.72, 1.99] | 92.89 [96.26, 87.73] | 4.08 [2.01, 7.22] | 0.28 [0.15, 0.51] | 0.85 [0.48, 1.43] | 0.67 [0.38, 1.13] |

| exp (2014–2019) | 2.00 [1.42, 2.73] | 83.50 [87.53, 78.93] | 5.11 [4.23, 6.13] | 0.82 [0.50, 1.35] | 7.74 [5.82, 9.52] | 0.83 [0.50, 1.35] |

| kr (2009–2013) | 2.06 [0.99, 3.70] | 1.88 [0.91, 3.30] | 94.20 [97.16, 89.61] | 0.15 [0.07, 0.29] | 1.10 [0.58, 1.94] | 0.60 [0.30, 1.15] |

| kr (2005–2014) | 1.79 [0.87, 3.23] | 1.86 [1.00, 3.02] | 93.43 [96.62, 88.83] | 1.11 [0.65, 1.67] | 1.22 [0.57, 2.21] | 0.59 [0.30, 1.05] |

| kr (2014–2019) | 1.45 [0.74, 2.57] | 2.19 [1.35, 3.40] | 92.01 [95.54, 86.94] | 2.44 [1.38, 3.70] | 1.01 [0.54, 1.72] | 0.91 [0.45, 1.67] |

| cur (2009–2013) | 1.92 [0.93, 3.40] | 1.06 [0.54, 1.93] | 1.52 [0.79, 2.71] | 93.95 [97.00, 89.08] | 0.94 [0.45, 1.77] | 0.61 [0.30, 1.12] |

| cur (2005–2014) | 5.25 [3.85, 6.63] | 0.83 [0.49, 1.33] | 32.27 [30.79, 33.04] | 60.08 [63.94, 56.47] | 0.80 [0.48, 1.29] | 0.78 [0.45, 1.24] |

| cur (2014–2019) | 1.42 [0.78, 2.38] | 1.24 [0.70, 2.08] | 19.48 [16.76, 21.62] | 75.36 [80.45, 69.82] | 0.88 [0.49, 1.45] | 1.62 [0.83, 2.65] |

| i (2009–2013) | 1.12 [0.55, 2.01] | 2.56 [1.27, 4.29] | 2.80 [1.51, 4.50] | 0.80 [0.38, 1.47] | 91.24 [95.51, 85.20] | 1.49 [0.78, 2.54] |

| i (2005–2014) | 0.79 [0.45, 1.32] | 0.77 [0.43, 1.28] | 36.30 [35.33, 36.63] | 0.98 [0.55, 1.55] | 60.11 [62.65, 57.58] | 1.06 [0.59, 1.63] |

| i (2014–2019) | 1.23 [0.61, 2.22] | 10.36 [8.31, 11.99] | 31.39 [30.98, 31.20] | 1.09 [0.62, 1.82] | 55.07 [59.06, 51.31] | 0.86 [0.43, 1.46] |

| u (2009–2013) | 1.51 [0.78, 2.62] | 1.26 [0.65, 2.22] | 1.52 [0.85, 2.54] | 4.17 [2.49, 6.02] | 1.87 [1.02, 3.21] | 89.67 [94.21, 83.39] |

| u (2005–2014) | 14.45 [12.58, 15.84] | 1.18 [0.66, 1.95] | 5.33 [3.21, 8.18] | 0.85 [0.54, 1.30] | 1.46 [0.92, 2.20] | 76.73 [82.09, 70.53] |

| u (2014–2019) | 1.50 [0.84, 2.49] | 1.88 [1.14, 2.90] | 8.31 [5.62, 10.96] | 1.16 [0.69, 1.91] | 1.99 [1.26, 3.01] | 85.16 [90.45, 78.72] |

Appendix C

| Specification | Pre-2014 Model | Post-2014 Model |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline specification | 87.155 | 85.589 |

| Exclusion of SUC and SUR priors | 25.504 | 36.93 |

| = 0.5, = 0.5 | 90.423 | 88.324 |

| = 1.5, = 1.5 | 83.264 | 83.095 |

| = 0.5 | 87.065 | 85.716 |

| = 1 | 86.587 | 85.772 |

Appendix D

References

- Alekhina, V.; Yoshino, N. Exogeneity of World Oil Prices to the Russian Federation’s Economy and Monetary Policy. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2019, 9, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangarika, A.M.; Tang, B. Influence oil price towards economic indicators in Russia. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Xiamen, China, 3–5 September 2018; Volume 192, p. 012066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drygalla, A. Monetary policy in an oil-dependent economy in the presence of multiple shocks. Rev. World Econ. 2023, 159, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K. Dutch disease and Russia. Int. Econ. 2017, 151, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balashova, S.; Serletis, A. Oil Price Shocks and the Russian Economy. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2020, 21, e00148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedictow, A.; Fjærtoft, D.; Løfsnæs, O. Oil Dependency of the Russian Economy: An Econometric Analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 32, 400–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrisov, G.; Kazakova, M.; Polbin, A. A theoretical interpretation of the oil prices impact on economic growth in contemporary Russia. Russ. J. Econ. 2015, 1, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonosov, D.; Polbin, A.; Fokin, N. The Impact of Global Economic Activity, Oil Supply and Speculative Oil Shocks on the Russian Economy. HSE Econ. J. 2021, 25, 227–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Oana-Ramona, L. Do oil price shocks drive unemployment? Evidence from Russia and Canada. Energy 2022, 253, 124107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W.; Qin, M.; Tao, R.; Umar, M. Does oil price really matter for the wage arrears in Russia? Energy 2020, 208, 118350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Rizvi, S.K.A.; Tan, Z.; Umar, M.; Koondhar, M.A. The Competing Role of Natural Gas and Oil as Fossil Fuel and the Non-Linear Dynamics of Resource Curse in Russia. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Murphy, P.; Villafuerte, M. Fiscal policy in oil producing countries during the recent oil price cycle. Int. Monet. Fund 2010, 2010, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbil, N. Is fiscal policy procyclical in developing oil-producing countries? Int. Monet. Fund 2011, 2011, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cologni, A.; Manera, M. Exogenous Oil Shocks, Fiscal Policies and Sector Reallocations in Oil Producing Countries. Energy Econ. 2013, 35, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayivodji, G.F.; Essl, S.M.; Galego, M.A.; Matta, S.N.; Richaud, C.M. Fiscal Vulnerabilities in Commodity Exporting Countries and the Role of Fiscal Policy; MTI Discussion Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, L.; Georgiou, D.; Heracleous, M.; Michaelides, A.; Tsani, S. Limiting Fiscal Procyclicality: Evidence from Resource-Dependent Countries. Econ. Model. 2022, 106, 105700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K.; Sokhanvar, A.; Belyaeva, Z.; Mirnezami, S.R. Hydrocarbon prices shocks, fiscal stability and consolidation: Evidence from Russian Federation. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurvich, E.; Vakulenko, E.; Krivenko, P. Cyclicality of Fiscal Policy in Oil-Producing Countries. Probl. Econ. Transit. 2009, 52, 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzova, Y.; Qayum, F. Global oil glut and sanctions: The impact on Putin’s Russia. Energy Policy 2016, 90, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçekçi, C.; Gaygısız, E. Procyclicality of fiscal policy in oil-rich countries: Roles of resource funds and institutional quality. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyunova, M. The Impact of Modern Monetary Policy on the Dynamics of Key Macroeconomic Indicators in Russia. Ph.D. Dissertation, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia, 17 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Xiong, C. Fiscal Stress and Monetary Policy Stance in Oil-Exporting Countries. J. Int. Money Financ. 2021, 111, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Z.; Guloglu, H. Macro-financial transmission of global oil shocks to BRIC countries—International financial (uncertainty) conditions matter. Energy 2024, 306, 132297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Central bank of Russian Federation. Available online: https://cbr.ru/content/document/file/87372/on_2015(2016-2017).pdf (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Giannone, D.; Lenza, M.; Primiceri, G.E. Prior Selection for Vector Autoregressions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2015, 97, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschnig, N.; Lukas, V. BVAR: Bayesian Vector Autoregressions with Hierarchical Prior Selection in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2021, 100, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L.; Lütkepohl, H. Bayesian VAR Analysis. In Structural Vector Autoregressive Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.A.; Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Inference in linear time series models with some unit roots. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1990, 58, 113–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litterman, R.B. Forecasting with Bayesian vector autoregressions—Five years of experience. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1986, 4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knotek, E.S., II; Zaman, S. Asymmetric responses of consumer expenditure to energy prices: A threshold VAR approach. Energy Econ. 2021, 95, 105127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.; Zha, T. Bayesian Methods for Dynamic Multivariate Models. Int. Econ. Rev. 1998, 39, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatkovska, V.; Lahiri, A.; Vegh, C.A. The exchange rate response to monetary policy innovations. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2016, 8, 137–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyunova, M. The Impact of Central Bank Policy on Production Dynamics and Inflation in Russia. Audit. Financ. Anal. 2018, 2, 185–195. Available online: https://istina.ipmnet.ru/publications/article/152182811/ (accessed on 11 January 2026).

| Variable | Description | Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Crude oil revenues in billions of rubles | Log | |

| Public expenditure in billions of rubles | Log | |

| Central policy key rate | levels | |

| National currency exchange rate against the USD | Log | |

| Year-to-year inflation rate | Levels | |

| Unemployment rate | Levels |

| Variable | Breakpoint Chow Test | Sample-Split Chow Test |

|---|---|---|

| September 2014 | <2 × 10−16 *** 1 | <2 × 10−16 *** |

| October 2017 | 1.000 | 0.248 |

| The Percentage Contribution (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oil | exp | kr | cur | i | u | |

| exp (2005–2019) | 0.77 [0.47, 1.23] | 95.13 [97.03, 92.37] | 1.55 [1.09, 2.16] | 0.43 [0.22, 0.77] | 1.64 [0.91, 2.62] | 0.50 [0.28, 0.85] |

| exp (2005–2013) | 1.27 [0.68, 2.25] | 96.54 [98.19, 93.71] | 0.56 [0.29, 1.04] | 0.16 [0.08, 0.31] | 0.87 [0.45, 1.57] | 0.60 [0.31, 1.12] |

| exp (2015–2019) | 2.34 [1.63, 3.27] | 85.63 [90.19, 80.21] | 1.30 [0.79, 2.09] | 1.35 [0.76, 2.20] | 8.30 [5.94, 10.53] | 1.09 [0.69, 1.69] |

| kr (2005–2019) | 1.71 [0.88, 2.81] | 0.79 [0.47, 1.27] | 94.24 [96.73, 90.85] | 1.99 [1.27, 2.74] | 0.71 [0.35, 1.32] | 0.57 [0.31, 1.01] |

| kr (2005–2013) | 6.90 [4.75, 9.25] | 0.78 [0.42, 1.37] | 89.16 [93.19, 84.13] | 0.15 [0.07, 0.29] | 2.32 [1.20, 3.70] | 0.69 [0.36, 1.27] |

| kr (2015–2019) | 1.80 [1.12, 2.92] | 1.60 [0.94, 2.62] | 88.18 [92.72, 82.16] | 5.36 [3.64, 7.12] | 2.00 [1.01, 3.34] | 1.06 [0.56, 1.83] |

| cur (2005–2019) | 2.35 [1.40, 3.50] | 0.78 [0.39, 1.35] | 13.19 [11.14, 15.02] | 82.25 [86.33, 77.65] | 0.63 [0.35, 1.07] | 0.79 [0.39, 1.41] |

| cur (2005–2013 | 7.61 [5.42, 9.65] | 1.09 [0.58, 1.90] | 3.98 [2.39, 5.77] | 85.15 [90.47, 79.06] | 1.41 [0.74, 2.32] | 0.76 [0.39, 1.31] |

| cur (2015–2019) | 1.47 [0.86, 2.43] | 1.96 [1.26, 2.93] | 4.59 [2.53, 6.95] | 87.60 [92.93, 80.95] | 1.43 [0.77, 2.45] | 2.95 [1.67, 4.29] |

| i (2005–2019) | 0.56 [0.27, 1.05] | 0.62 [0.30, 1.11] | 25.21 [23.59, 26.26] | 0.55 [0.28, 1.00] | 72.18 [75.13, 69.07] | 0.88 [0.43, 1.51] |

| i (2005–2013) | 0.92 [0.47, 1.64] | 1.33 [0.62, 2.42] | 4.72 [2.76, 6.90] | 0.52 [0.24, 1.00] | 90.81 [95.04, 85.27] | 1.70 [0.88, 2.77] |

| i (2015–2019) | 1.40 [0.74, 2.39] | 5.95 [3.77, 8.14] | 2.50 [1.30, 4.17] | 4.18 [2.35, 6.21] | 82.98 [90.00, 74.90] | 2.99 [1.85, 4.19] |

| u (2005–2019) | 5.92 [4.32, 7.46] | 2.34 [1.42, 3.40] | 1.81 [0.97, 2.91] | 0.76 [0.47, 1.19] | 1.02 [0.57, 1.72] | 88.16 [92.25, 83.32] |

| u (2005–2013) | 14.00 [11.60, 16.15] | 0.77 [0.41, 1.36] | 1.16 [0.64, 1.97] | 0.95 [0.54, 1.56] | 1.54 [0.90, 2.54] | 81.58 [85.90, 76.43] |

| u (2015–2019) | 2.09 [1.15, 3.37] | 2.31 [1.43, 3.51] | 20.11 [17.94, 21.32] | 1.57 [0.95, 2.51] | 3.96 [2.53, 5.64] | 69.96 [76.00, 63.65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chernykh, I.; Yu, N. Subsample Analysis of Oil Revenue Shocks and Macroeconomic Policy Transmission. Systems 2026, 14, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020133

Chernykh I, Yu N. Subsample Analysis of Oil Revenue Shocks and Macroeconomic Policy Transmission. Systems. 2026; 14(2):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020133

Chicago/Turabian StyleChernykh, Ivan, and Nannan Yu. 2026. "Subsample Analysis of Oil Revenue Shocks and Macroeconomic Policy Transmission" Systems 14, no. 2: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020133

APA StyleChernykh, I., & Yu, N. (2026). Subsample Analysis of Oil Revenue Shocks and Macroeconomic Policy Transmission. Systems, 14(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020133