A Cost-Optimization Model for Water-Scarcity Mitigation Strategies Towards Differentiated City Types in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. An Integrated Modeling Approach for Water Scarcity

2.2. Regional Water Scarcity Assessment

2.3. Classification of Scarcity Types

2.4. Water-Scarcity Optimization Model

2.4.1. Water-Scarcity Management Options

2.4.2. Optimization Model Design

3. Results

3.1. Water Scarcity in China

3.2. Seasonality of Water Scarcity in China

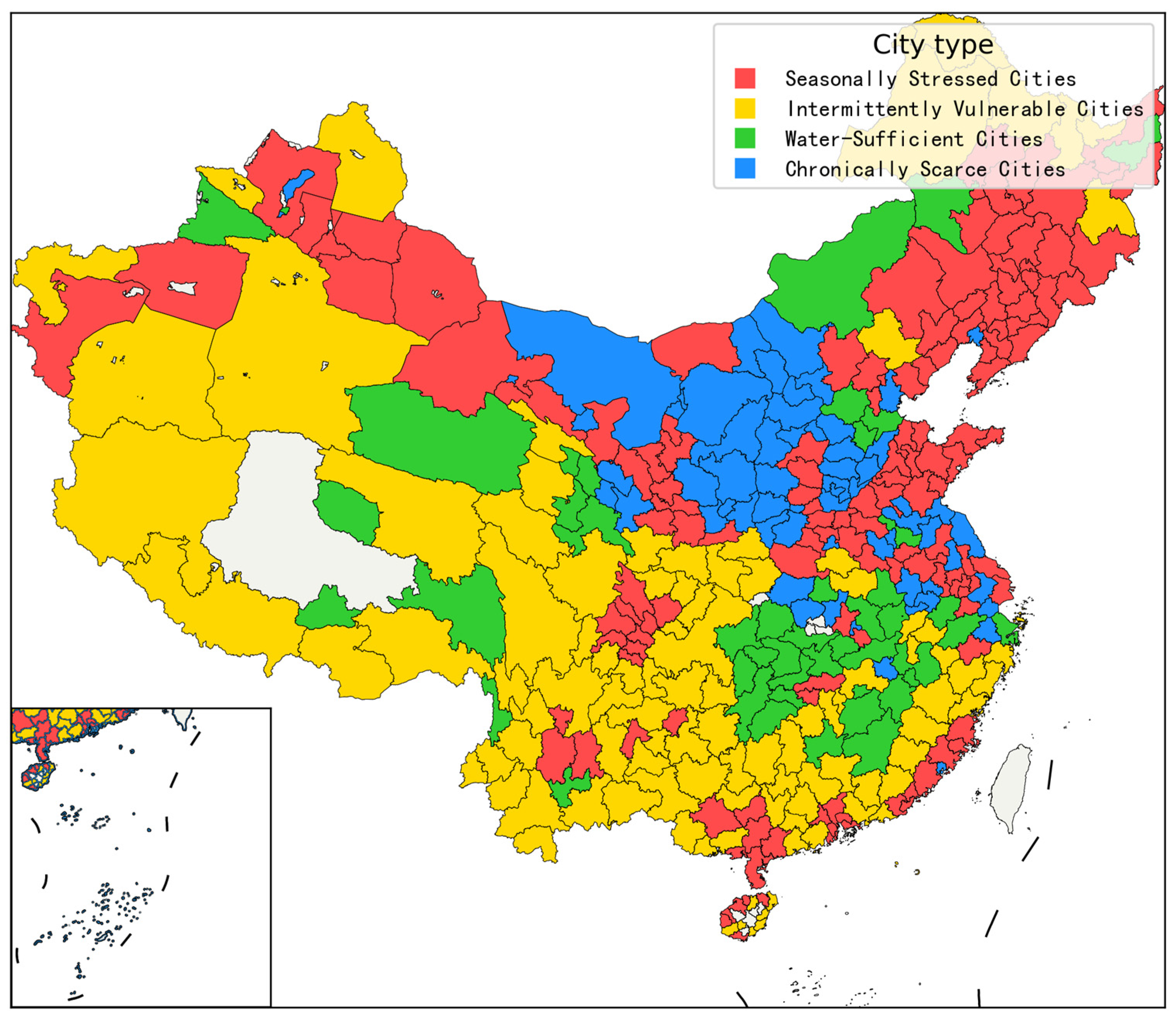

3.3. Classification of Water Scarcity Types in China

3.4. Results of the Optimization Model for Water-Scarcity Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, Y.; Bierkens, M.F. Sustainability of global water use: Past reconstruction and future projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.R.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; van Vliet, M.T.H. Current and future global water scarcity intensifies when accounting for surface water quality. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Water. Progress on Level of Water Stress—2024 Update; UN-Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Shuai, C.; Chen, X.; Sun, J.; Zhao, B. Linking local and global: Assessing water scarcity risk through nested trade networks. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Tang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wada, Y.; Yang, H. Global Agricultural Water Scarcity Assessment Incorporating Blue and Green Water Availability Under Future Climate Change. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. China’s water scarcity. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3185–3196. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, C.; Fu, G. Unraveling the effect of inter-basin water transfer on reducing water scarcity and its inequality in China. Water Res. 2021, 194, 116931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shuai, C.; Xiang, P.; Chen, X.; Zhao, B. Mapping water scarcity risk in China with the consideration of spatially heterogeneous environmental flow requirement. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Qi, L.; Liu, M. Evaluation of the comprehensive carrying capacity of interprovincial water resources in China and the spatial effect. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 794–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Peng, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Ding, Y.; et al. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature 2010, 467, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, M.T.H.; Jones, E.R.; Flörke, M.; Franssen, W.H.P.; Hanasaki, N.; Wada, Y.; Yearsley, J.R. Global water scarcity including surface water quality and expansions of clean water technologies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 024020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, M.T.H.; Flörke, M.; Wada, Y. Quality matters for water scarcity. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M.; Lundqvist, J.; Widstrand, C. Macro-scale water scarcity requires micro-scale approaches. Nat. Resour. Forum 1989, 13, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, A.V.; Ludwig, F.; Biemans, H.; Hoff, H.; Kabat, P. Accounting for environmental flow requirements in global water assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 5041–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; Fang, Z.; Li, J.; Bryan, B.A. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schewe, J.; Heinke, J.; Gerten, D.; Haddeland, I.; Arnell, N.W.; Clark, D.B.; Dankers, R.; Eisner, S.; Fekete, B.M.; Colón-González, F.J.; et al. Multimodel assessment of water scarcity under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3245–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokal, M.; Kahil, T.; Wada, Y.; Albiac, J.; Bai, Z.; Ermolieva, T.; Langan, S.; Ma, L.; Oenema, O.; Wagner, F.; et al. Cost-effective management of coastal eutrophication: A case study for the Yangtze river basin. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygoruk, M.; Mirosław-Świątek, D.; Chrzanowska, W.; Ignar, S. How Much for Water? Economic Assessment and Mapping of Floodplain Water Storage as a Catchment-Scale Ecosystem Service of Wetlands. Water 2013, 5, 1760–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Zhao, L.; Han, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Mitigating water imbalance between coastal and inland areas through seawater desalination within China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 371, 133418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Wang, K.; Di, C.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, J. Exploring China’s water scarcity incorporating surface water quality and multiple existing solutions. Environ. Res. 2024, 246, 118191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Gao, Q. Water-saving irrigation promotion and food security: A study for China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chiu, Y.-h.; Guo, Z.; Chu, Y.; Du, X. Evaluating the recycling efficiency of industrial water use systems in China: Basin differences and factor analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulkhani, K.; Logasa, B.; Presa Reyes, M.; Mostafavi, A. Understanding Fundamental Phenomena Affecting the Water Conservation Technology Adoption of Residential Consumers Using Agent-Based Modeling. Water 2018, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, R.; Sun, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Research on the progress of agricultural non-point source pollution management in China: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccour, S.; Goelema, G.; Kahil, T.; Albiac, J.; van Vliet, M.T.H.; Zhu, X.; Strokal, M. Water quality management could halve future water scarcity cost-effectively in the Pearl River Basin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Water Resources of China. China Water Resources Bulletin 2021; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Ministry of Water Resources of China. China Water Resources Bulletin 2022; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Ministry of Water Resources of China. China Water Resources Bulletin 2023; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Ministry of Water Resources of China. China Water Resources Bulletin 2024; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Zou, X.; Li, Y.e.; Cremades, R.; Gao, Q.; Wan, Y.; Qin, X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of water-saving irrigation technologies based on climate change response: A case study of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlner, H. Institutional change and the political economy of water megaprojects: China’s south-north water transfer. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 38, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China. Guidelines for the Construction and Investment of Rural Domestic Wastewater Treatment Projects; Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Sun, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, L.; Xie, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, G.; Liu, F. Optimization of pollutant reduction system for controlling agricultural non-point-source pollution based on grey relational analysis combined with analytic hierarchy process. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 243, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Li, Y.-e.; Gao, Q.; Wan, Y. How water saving irrigation contributes to climate change resilience—A case study of practices in China. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2012, 17, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Handbook on Accounting Methods and Coefficients for Pollution Discharge in the Statistical Survey of Emission Sources; Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Ma, T.; Sun, S.; Fu, G.; Hall, J.W.; Ni, Y.; He, L.; Yi, J.; Zhao, N.; Du, Y.; Pei, T.; et al. Pollution exacerbates China’s water scarcity and its regional inequality. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.; Miao, C.; Samaniego, L.; Xiao, M.; Wu, J.; Guo, X. CNRD v1. 0: A high-quality natural runoff dataset for hydrological and climate studies in China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E929–E947. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, C.; Gou, J. CNRDv1.0: The China Natural Runoff Dataset Version 1.0 (1961–2018); National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, G. Satellite-Based Global Irrigation Water Use Data Set (2011–2018); National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, G. Estimation of global irrigation water use by the integration of multiple satellite observations. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, N.; Liu, L.; Hejazi, M.; Tesfa, T.; Li, H.; Huang, M.; Liu, Y.; Leung, L. One-way coupling of an integrated assessment model and a water resources model: Evaluation and implications of future changes over the US Midwest. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 4555–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Wada, Y.; Van Beek, L.; Viviroli, D.; Dürr, H.H.; Weingartner, R.; Bierkens, M.F. Global monthly water stress: 2. Water demand and severity of water stress. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch, M.J.; Sapundjieff, M.J.; Feirer, S.T. Characterizing Precipitation Variability and Trends in the World’s Mediterranean-Climate Areas. Water 2017, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Qu, H.; Yin, L.; Guo, L. Modeling the distribution of cultural ecosystem services based on future climate variables under different scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, A.; Jilo, N.; Muluneh, F. Spatial-temporal rainfall trend and variability assessment in the Upper Wabe Shebelle River Basin, Ethiopia: Application of innovative trend analysis method. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 37, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.F.; Roche, K.R.; Dralle, D.N. Catchment processes can amplify the effect of increasing rainfall variability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 084032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, A.; Kohnová, S. Comparison of tests for trend in location and scale parameters in hydrological and precipitation time series. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 2021, 19, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, C. Evaluation of agricultural water-saving effects in the context of water rights trading: An empirical study from China’s water rights pilots. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127725. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 14th Five-Year Plan for Comprehensive Management of Water Environment in Key River Basins; National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, J.-G.; Zhang, N.; Cao, W. Biogas energy generated from livestock manure in China: Current situation and future trends. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 14th Five-Year Plan for Water Security; National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB 18918-2002; Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Ma, D.; Shi, H.; Feng, A. Estimation of agricultural non-point source pollution based on watershed unit: A case study of Laizhou Bay. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 6412–6420. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. China Water Resources Statistical Yearbook; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Beijing Municipal Water Authority. Beijing’s 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of a Water-Saving Society; Beijing Municipal Government: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Guangzhou Municipal Water Authority. Guangzhou Water Conservation Plan (2018–2035); Guangzhou Municipal Government: Guangzhou, China, 2020.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. China Urban-Rural Construction Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- General Office of Beijing Municipal People’s Government. Notice on Issuing the Implementation Plan for Resource Utilization of Livestock and Poultry Breeding Waste in Beijing; Beijing Municipal People’s Government: Beijing, China, 2018.

- General Office of Wuhan Municipal People’s Government. Notice on Issuing the Implementation Plan for Resource Utilization of Livestock and Poultry Breeding Waste in Wuhan; Wuhan Municipal People’s Government: Wuhan, China, 2018.

- Gurobi Optimization, LLC. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual; Gurobi Optimization, LLC: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Zhao, N.; Ni, Y.; Yi, J.; Wilson, J.P.; He, L.; Du, Y.; Pei, T.; Zhou, C.; Song, C.; et al. China’s improving inland surface water quality since 2003. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaau3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Implementation Opinions on Strengthening the Prevention and Control of Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution; Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

| Variables | Spatial and Temporal Resolution/Management Measures | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|

| Data related to water-scarcity assessment | ||

| Water availability | At the city level on an annual basis | China Water Resources Bulletin [27,28,29,30] |

| Water quality | At the sampling-site level on a monthly basis | China National Environmental Monitoring Centre |

| Sectoral water use | At the city level on an annual basis | China Water Resources Bulletin [27,28,29,30] |

| Data related to scarcity-optimization model | ||

| Cost parameters | Water saving | Zou et al. [31], Rasoulkhani et al. [24] |

| Water storage | Grygoruk et al. [19] | |

| Water transfer | Pohlner [32] | |

| point-source pollution control | obtained from government guidelines [33] | |

| farmland runoff treatment | Sun et al. [34] | |

| livestock manure and wastewater treatment | Sun et al. [34] | |

| Effect parameters | Water saving | Zou et al. [35], Rasoulkhani et al. [24] |

| point-source pollution control | obtained from government statistical survey [36] | |

| farmland runoff treatment | Sun et al. [34] | |

| livestock manure and wastewater treatment | Sun et al. [34] | |

| Options | Description |

|---|---|

| Agricultural water-saving management options | |

| Low-pressure pipe irrigation | |

| Micro-irrigation | |

| Sprinkler irrigation | |

| Domestic water-saving management options | |

| Water-efficient bathroom faucet | |

| Water-efficient kitchen faucet | |

| Water efficient showerhead | |

| Water efficient toilet | |

| Water-efficient washing machine | |

| Water efficient dishwasher | |

| Water transfers | |

| Water storage | |

| Water transport | |

| Rural domestic wastewater management options | |

| Construction of centralized treatment plants with Class I-A effluent standards. * | |

| Construction of centralized treatment plants with Class I-B effluent standards. | |

| Construction of centralized treatment plants with Class II effluent standards. | |

| Farmland runoff management option | |

| Interception and treatment of agricultural non-point source runoff. | |

| Livestock manure and wastewater treatment options | |

| Treatment of mixed livestock manure and wastewater for direct discharge after meeting standards. | |

| ). | |

| City | Average WS | Coefficient of Variation | Scarcity Driver | Type | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 15.29 | 0.711 | Compound | Seasonal scarcity city | North China |

| Wuhan | 1.975 | 0.639 | Quantity | Seasonal scarcity city | Central China |

| Kunming | 2.146 | 0.778 | Quality | Seasonal scarcity city | Southwest |

| Chongqing | 0.442 | 0.734 | - | Intermittent scarcity city | Southwest |

| Hohhot | 4.213 | 0.31 | Compound | Persistent scarcity city | North China |

| Guangzhou | 5.497 | 0.91 | Compound | Seasonal scarcity city | South China |

| Shanghai | 3.588 | 0.60 | Compound | Seasonal scarcity city | East China |

| City | Beijing | Guangzhou | Hohhot | Kunming | Shanghai | Wuhan | Chongqing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scarcity level after optimization | 4.69 | 2.27 | 1.72 | 1.00 | 2.25 | 1.35 | 0.40 |

| Scarcity-reduction rate | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.09 |

| Total cost (billion CNY) | 8.70 | 22.74 | 2.15 | 14.85 | 18.16 | 2.90 | 0.42 |

| Cost per 1% shortage reduction (billion CNY/%) | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Water-Quantity Options | Beijing | Guangzhou | Hohhot | Kunming | Shanghai | Wuhan | Chongqing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | Costs | Water Saving /Transfer | ||

| Agriculture water saving | Low-pressure pipe irrigation | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.3639 | 0.0093 | 7.8521 | 0.3084 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| micro irrigation | 2.0662 | 0.0256 | 14.0023 | 0.5742 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 14.3424 | 0.3220 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Sprinkler irrigation | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1213 | 0.3588 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Water transfers | Water storage | 3.7742 | 0.7171 | 8.5580 | 1.6242 | 0.3836 | 0.073 | 6.4431 | 1.2242 | 3.6500 | 0.6935 | 2.7337 | 0.5195 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Water transport | 2.6266 | 0.9600 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Water-Quality Options | Beijing | Guangzhou | Hohhot | Kunming | Shanghai | Wuhan | Chongqing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs | Pollutants Reduced | Costs | Pollutants Reduced | Costs | Pollutants Reduced | Costs | Pollutants Reduced | Costs | Pollutants Reduced | Costs | Pollutants Reduced | Costs | Pollutants Reduced | ||

| Rural domestic wastewater | Treatment of wastewater to CLASS I-A standard | 0.1541 | 8.6737 | 0.0894 | 3.0485 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0831 | 4.5285 | 0.0948 | 4.2719 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 0.6878 | 0.3447 | 0.0000 | 0.2444 | 0.3925 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| 0.5369 | 0.2700 | 0.0000 | 0.1606 | 0.2551 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| 0.0412 | 0.0414 | 0.0000 | 0.0274 | 0.0298 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| Agriculture runoff | Farmland runoff control | 0.0444 | 8.8281 | 0.0241 | 4.8004 | 0.1619 | 32.1954 | 0.0917 | 18.2289 | 0.0513 | 10.2129 | 0.0698 | 13.8732 | 0.3854 | 76.6486 |

| 7.8183 | 4.2513 | 28.5128 | 16.1438 | 9.0447 | 12.2863 | 67.8812 | |||||||||

| 0.5202 | 0.2829 | 1.8971 | 1.0741 | 0.6018 | 0.8175 | 4.5166 | |||||||||

| 0.0872 | 0.0474 | 0.3180 | 0.1801 | 0.1009 | 0.1370 | 0.7572 | |||||||||

| Livestock waste | Discharge after co-treatment | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0072 | 11.981 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0392 | 65.0960 |

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.272 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 12.3458 | |||||||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9640 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 5.2376 | |||||||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9640 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 5.2376 | |||||||||

| Land application after treatment | 0.0358 | 6.7622 | 0.0765 | 14.1985 | 0.2342 | 32.8404 | 0.3804 | 59.3320 | 0.0262 | 4.2721 | 0.0957 | 18.4651 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| 1.0720 | 2.2542 | 5.3547 | 9.5689 | 0.6860 | 2.9223 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| 0.4388 | 0.9228 | 2.1927 | 3.9180 | 0.2809 | 1.1963 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| 0.5571 | 1.1694 | 2.6932 | 4.8744 | 0.3512 | 1.5215 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| Aspect | Ma et al. [37] | Li et al. [21] | Baccour et al. [26] | This Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study domain | Nationwide | Nationwide | Pearl River Basin | Nationwide |

| Quantity–quality coupled indicator | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Number of water-quality parameters | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Identification of cost-optimal strategies | √ | √ | ||

| Consideration of existing mitigation measures in China | √ | √ | ||

| Scarcity-based classification framework | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. A Cost-Optimization Model for Water-Scarcity Mitigation Strategies Towards Differentiated City Types in China. Systems 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010006

Zeng Z, Yang Y, Wang X. A Cost-Optimization Model for Water-Scarcity Mitigation Strategies Towards Differentiated City Types in China. Systems. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Ziqiang, Yuechuan Yang, and Xingyou Wang. 2026. "A Cost-Optimization Model for Water-Scarcity Mitigation Strategies Towards Differentiated City Types in China" Systems 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010006

APA StyleZeng, Z., Yang, Y., & Wang, X. (2026). A Cost-Optimization Model for Water-Scarcity Mitigation Strategies Towards Differentiated City Types in China. Systems, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010006