Lowering the Threshold for Integration of Big Data Services into Closed-Loop Supply Chain: Necessary Conditions Based on the Variational Inequality Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can we derive necessary coordination conditions when a BDSP joins a CLSC as an independent member?

- How can decentralized coordination match centralized efficiency and reduce the need for complex contracts?

- How does a BDSP’s involvement in marketing and recycling impact pricing decisions and the profitability of a CLSC?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Supply Chain Coordination Mechanisms

2.2. Application of Big Data Services in the Supply Chain

2.3. Summary

3. Problem Description and Basic Assumptions

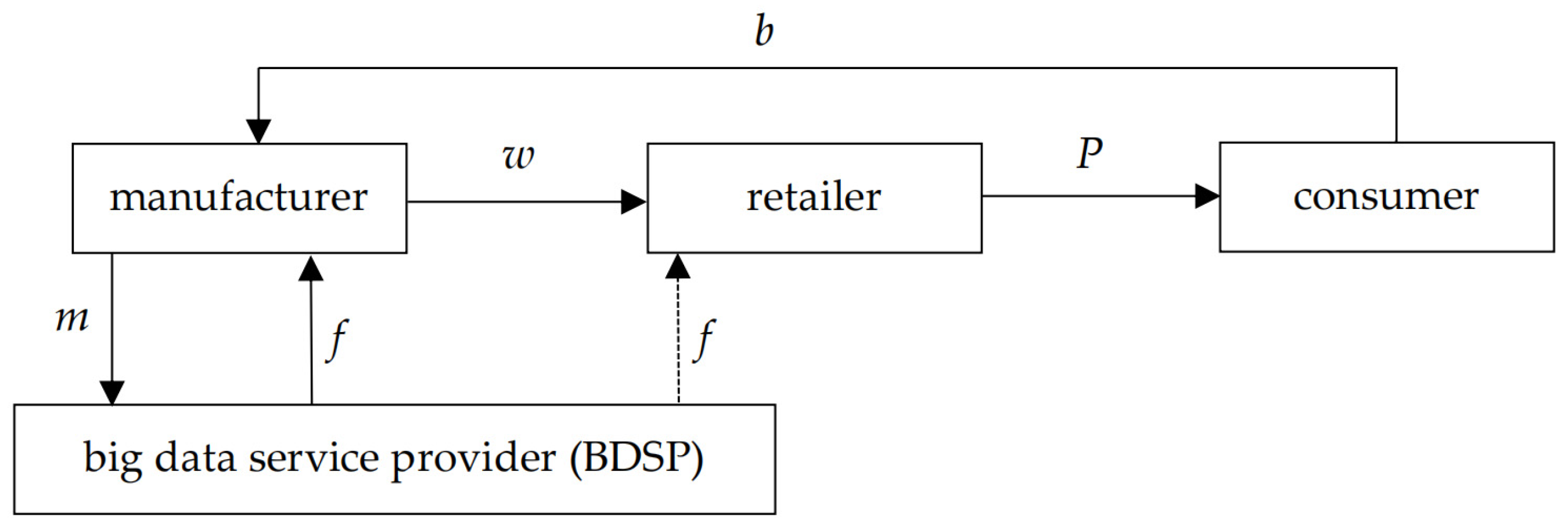

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Basic Assumptions

4. Model Construction and Solution

4.1. Decentralized Decision-Making Model

4.2. Centralized Decision-Making Model

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- .

- (4)

- .

- (5)

- .

- (6)

- .

5. Optimization Analysis of Coordination Conditions

5.1. Manufacturer’s Optimization Analysis

5.2. Retailer’s Optimization Analysis

5.3. BDSP’s Optimization Analysis

5.4. System Optimality Conditions Analysis

- (1)

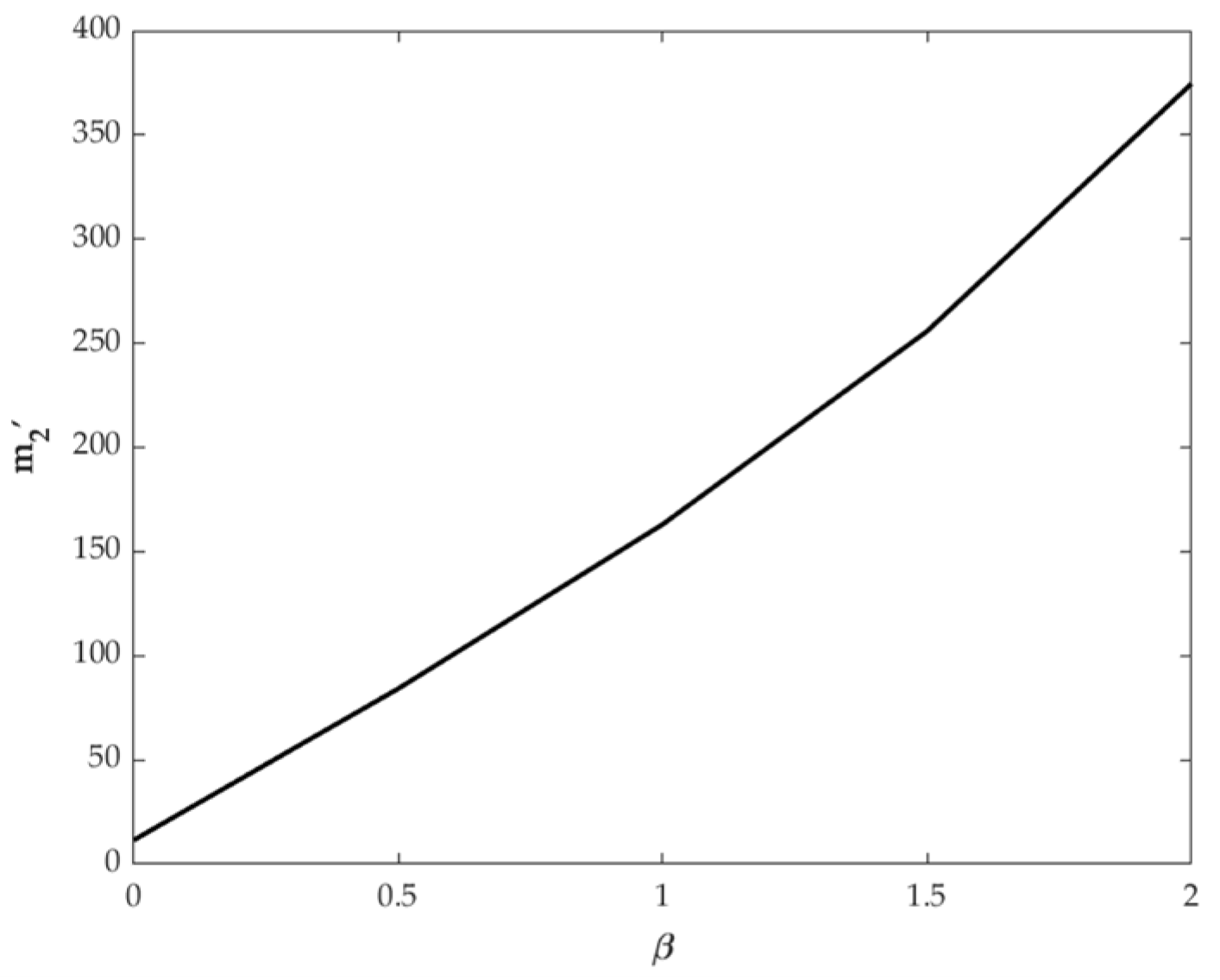

- The value of m2′ increases as production volume rises.

- (2)

- The more unit cost savings there are, the higher m2′ becomes.

- (3)

- (4)

- .

- (5)

- When , .

- (6)

- .

- (7)

- .

- (1)

- , , .

- (2)

- , , .

- (1)

- , .

- (2)

- , .

6. Numerical Analysis

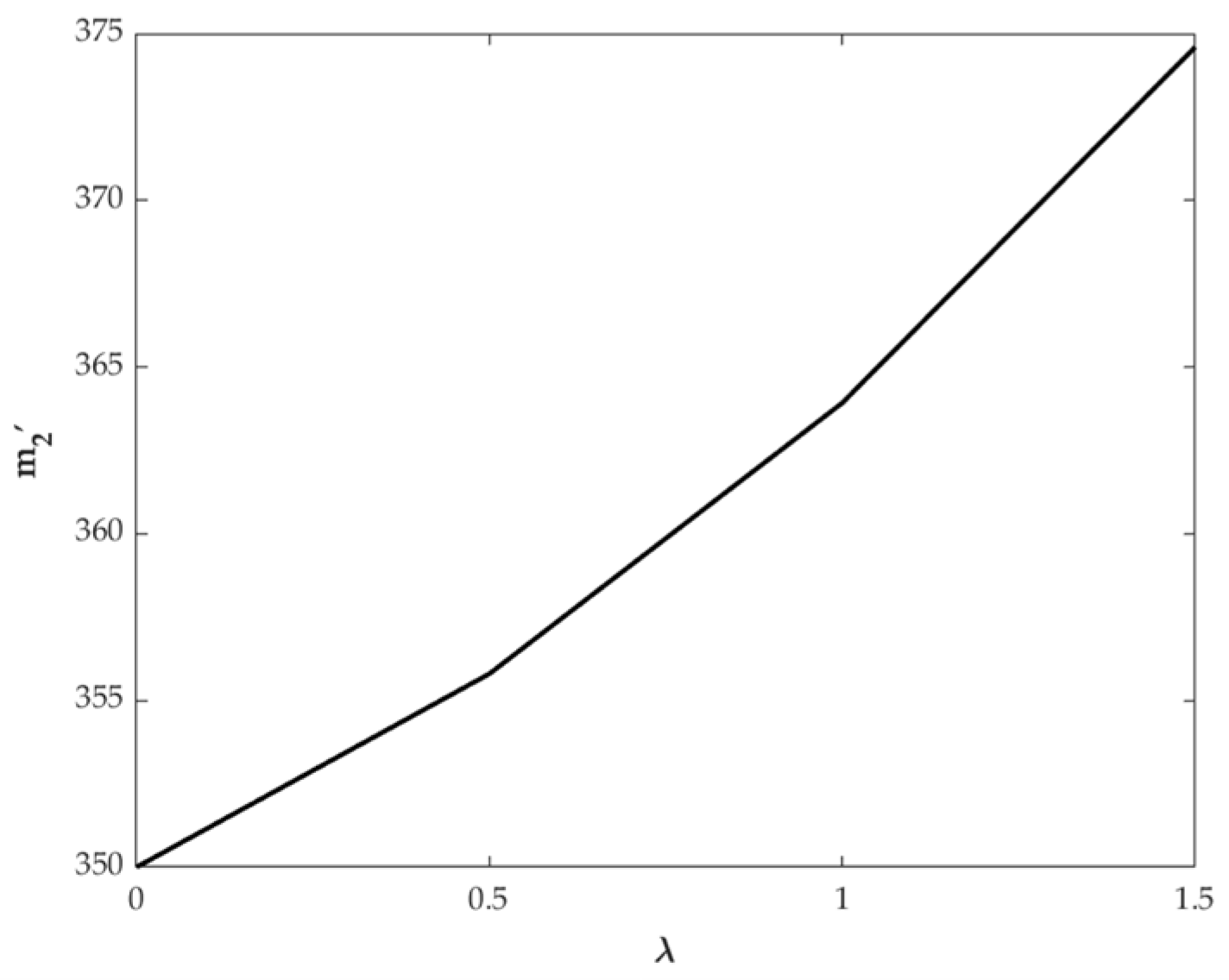

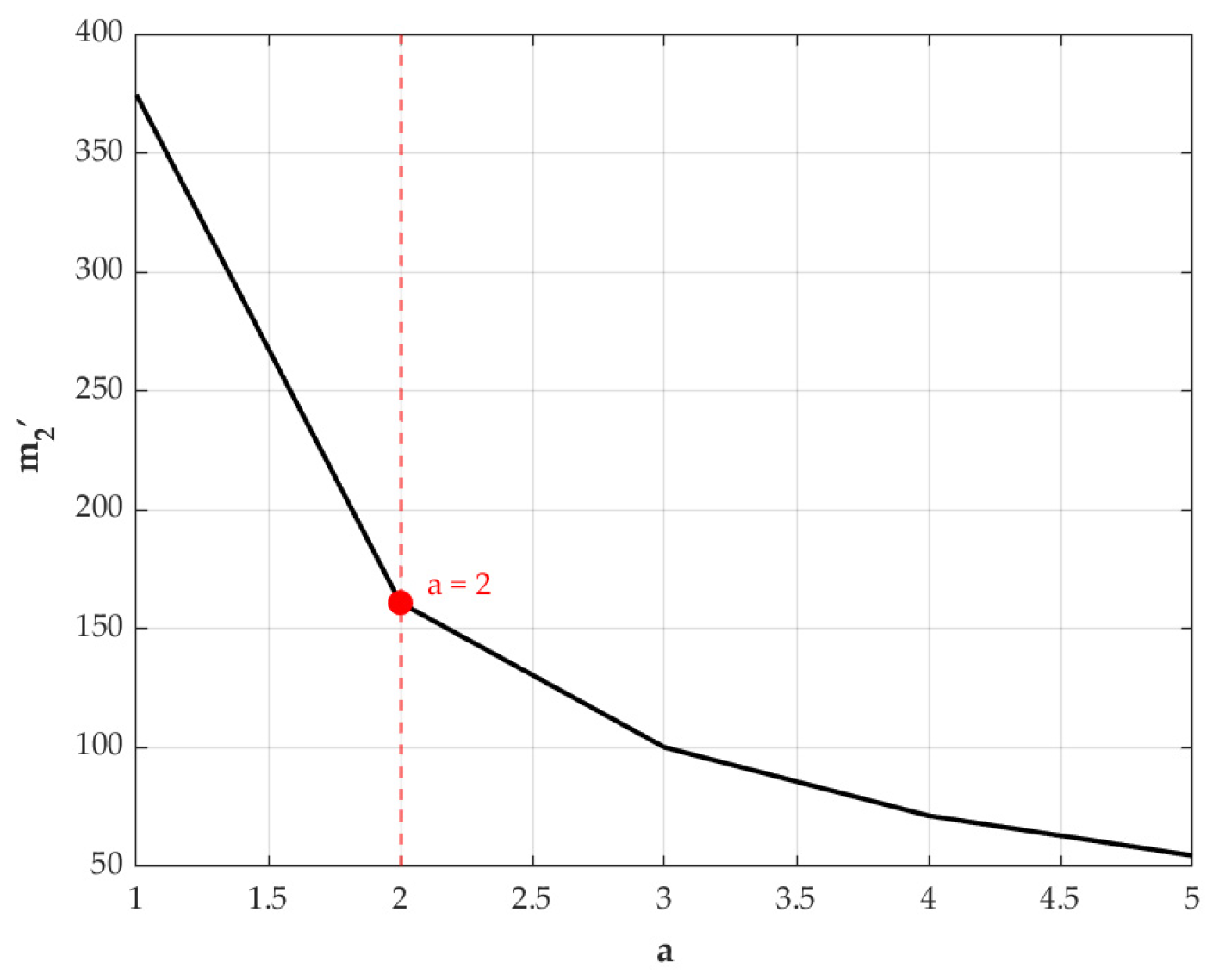

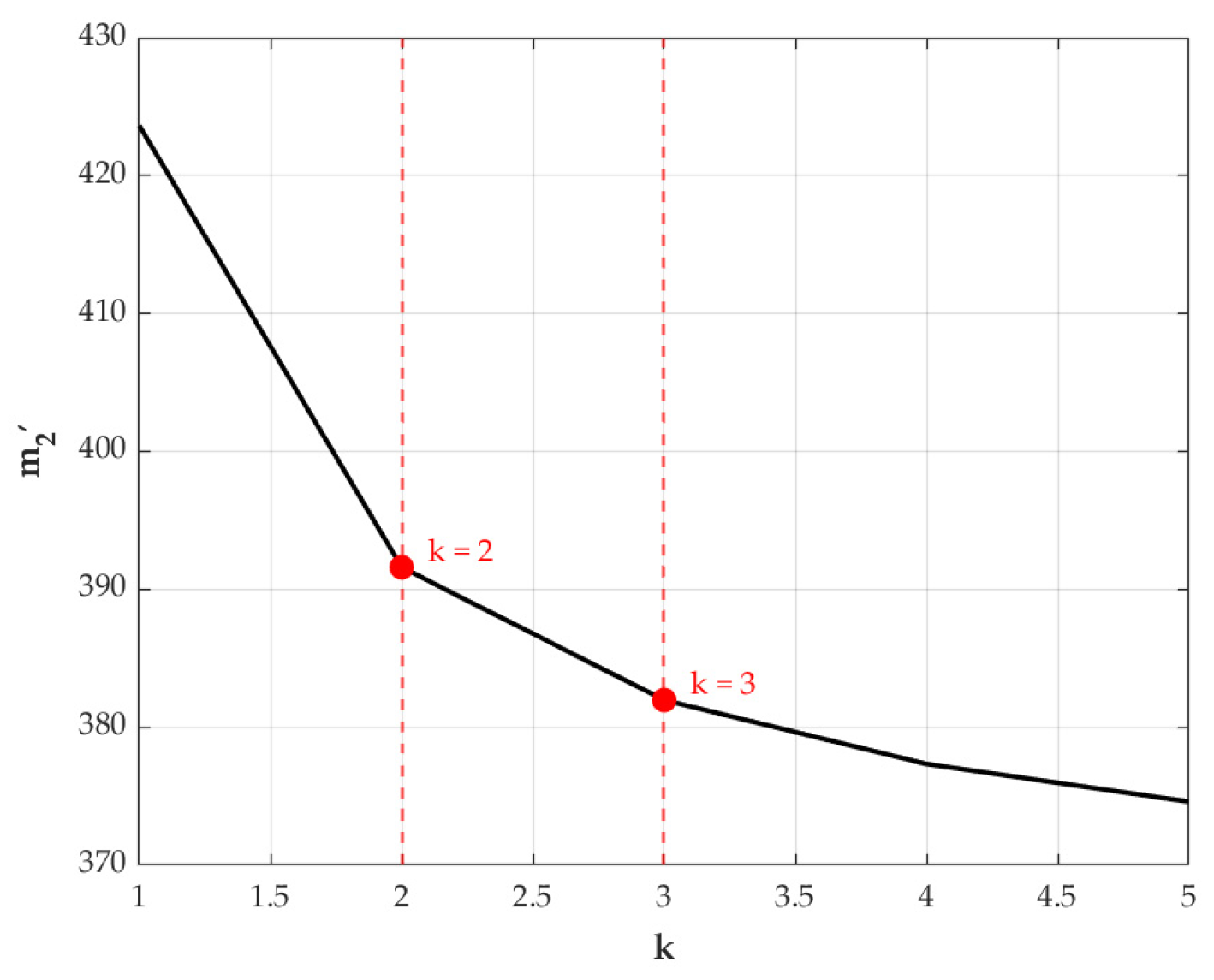

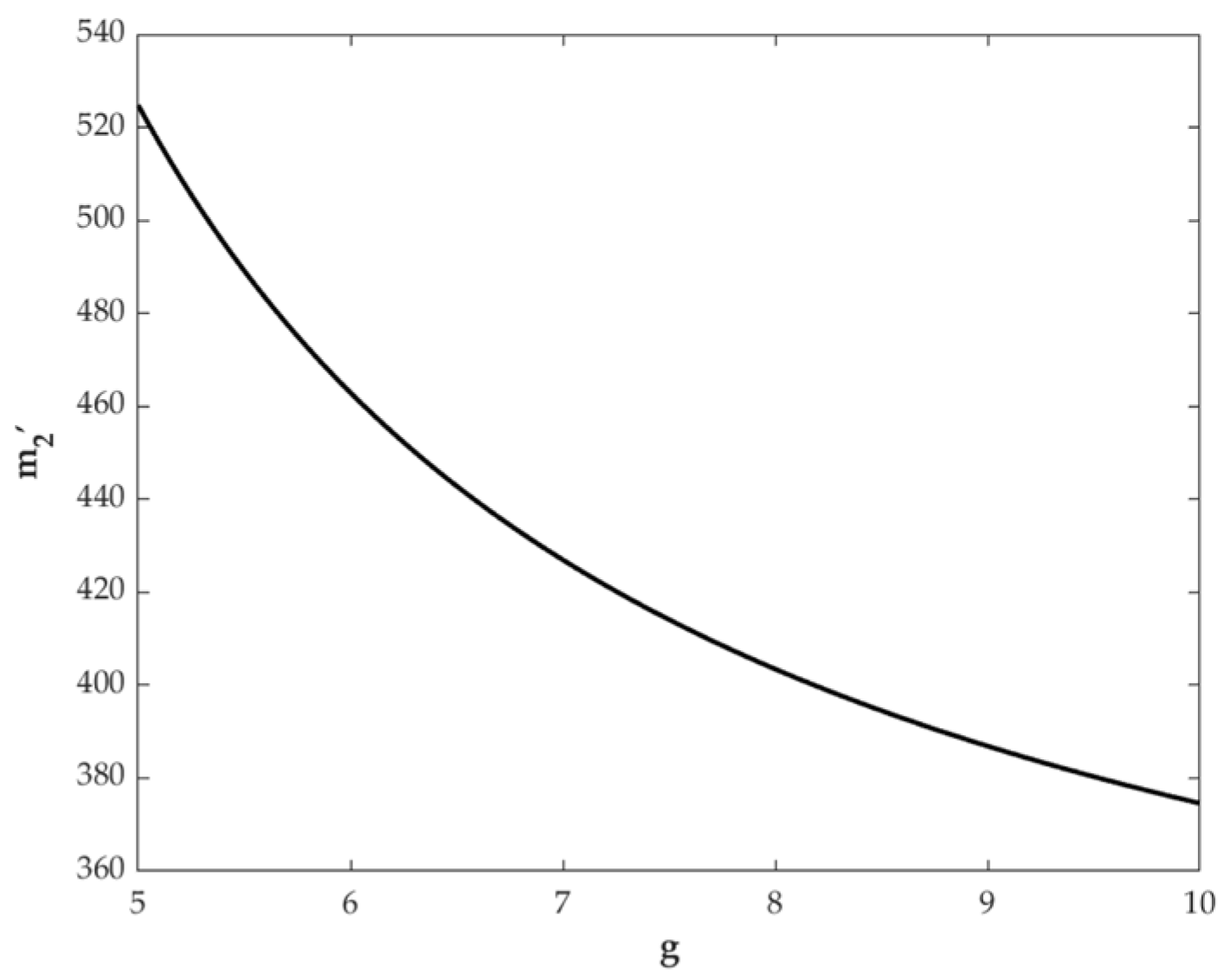

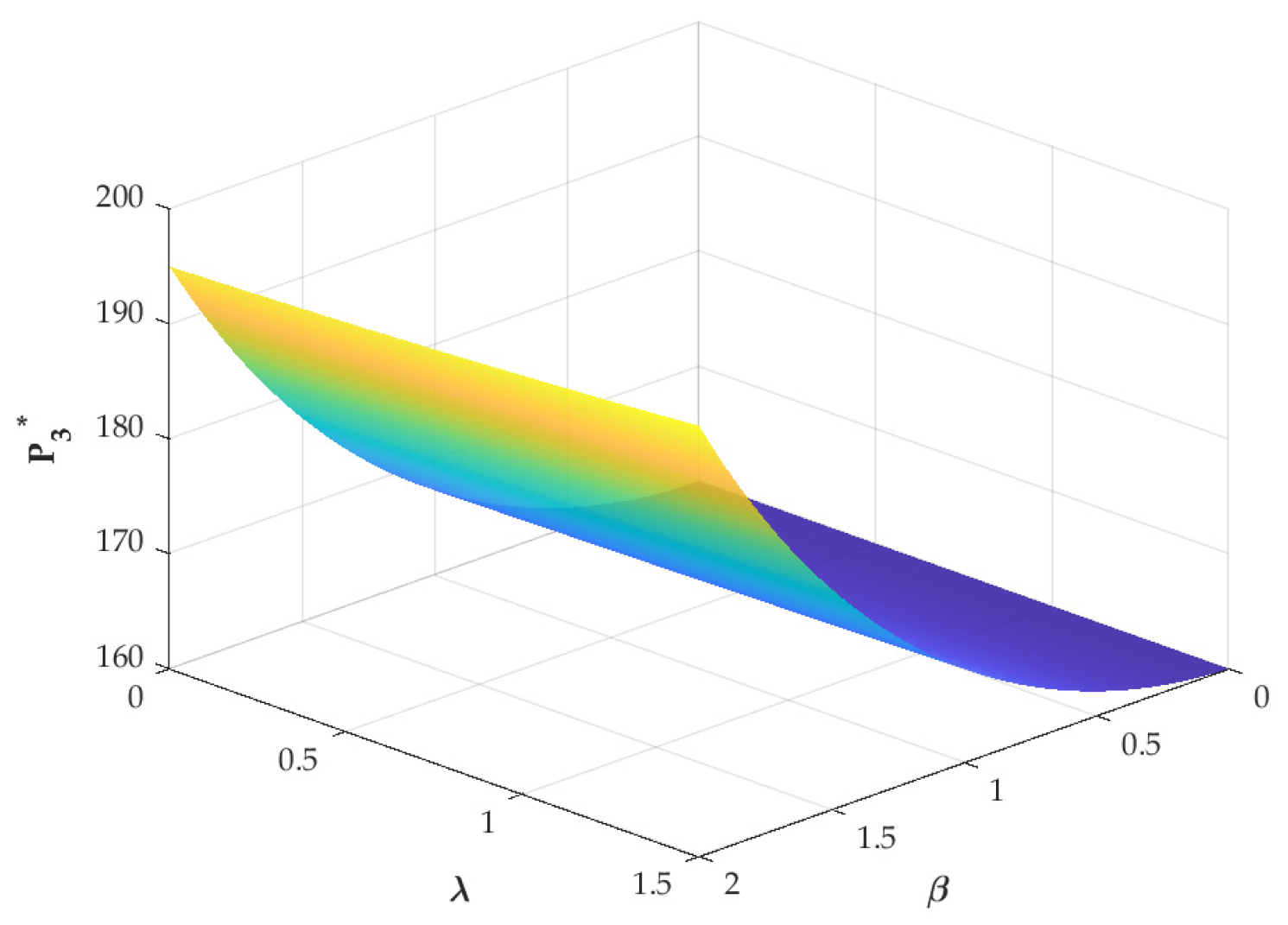

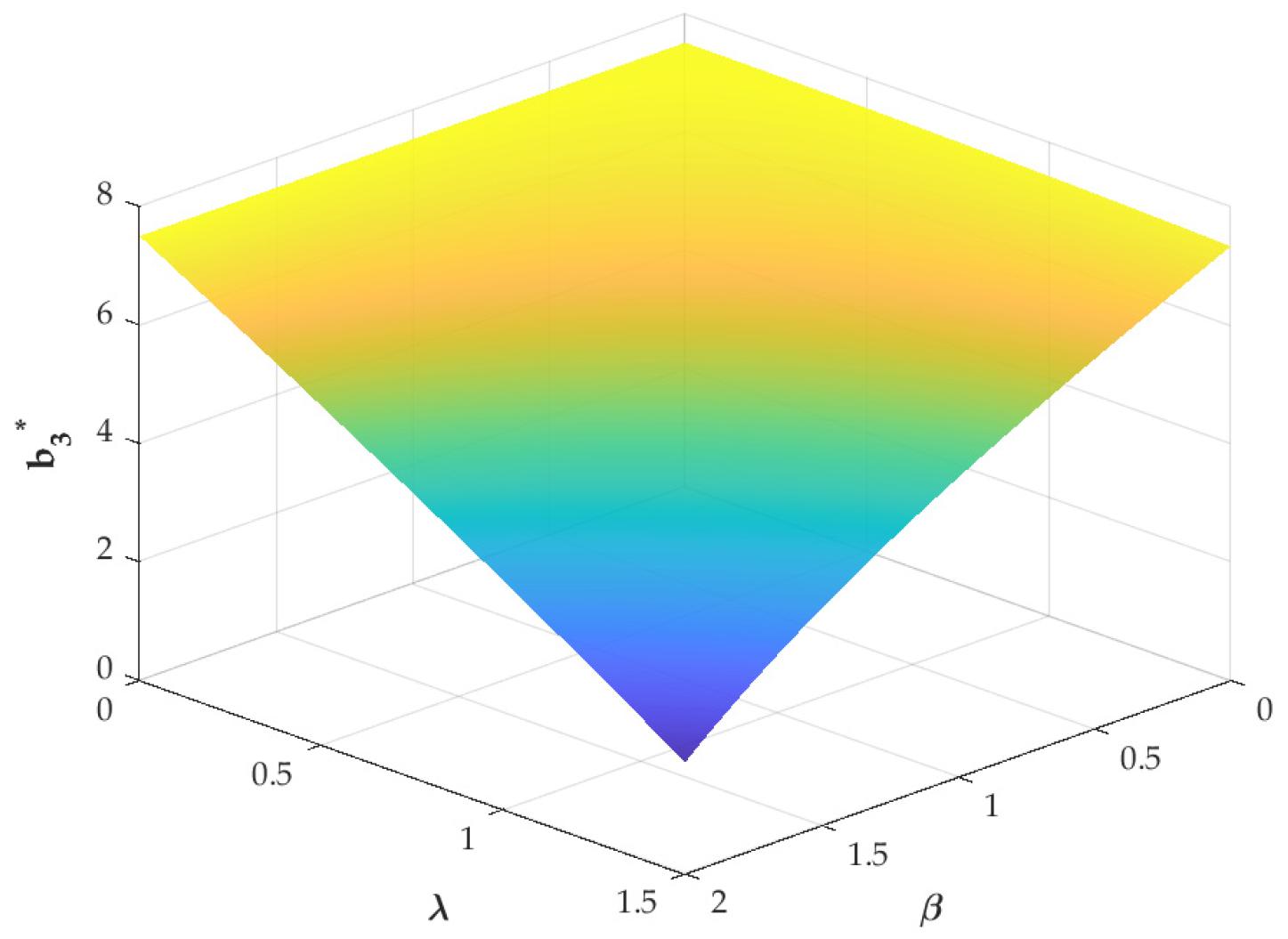

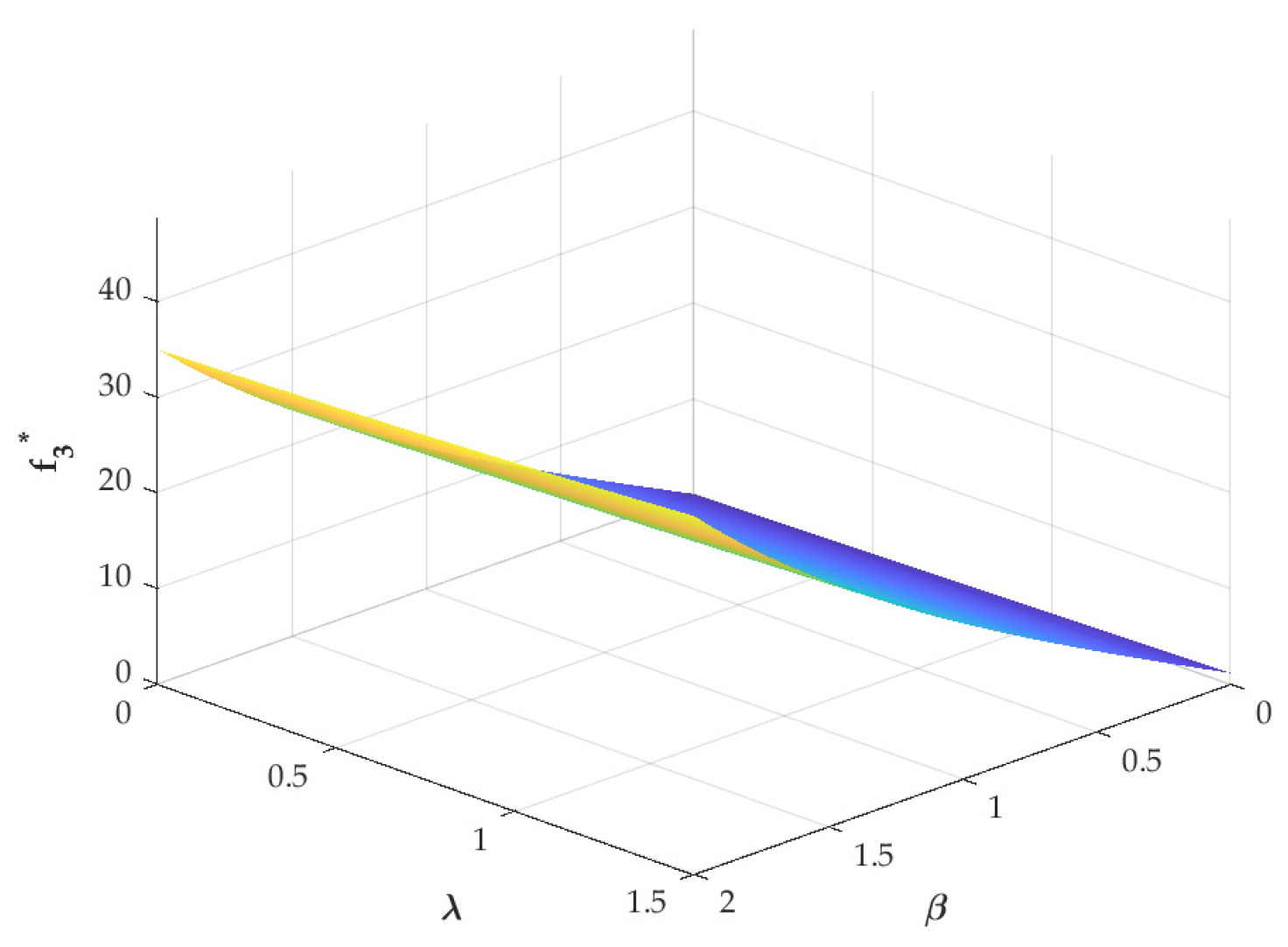

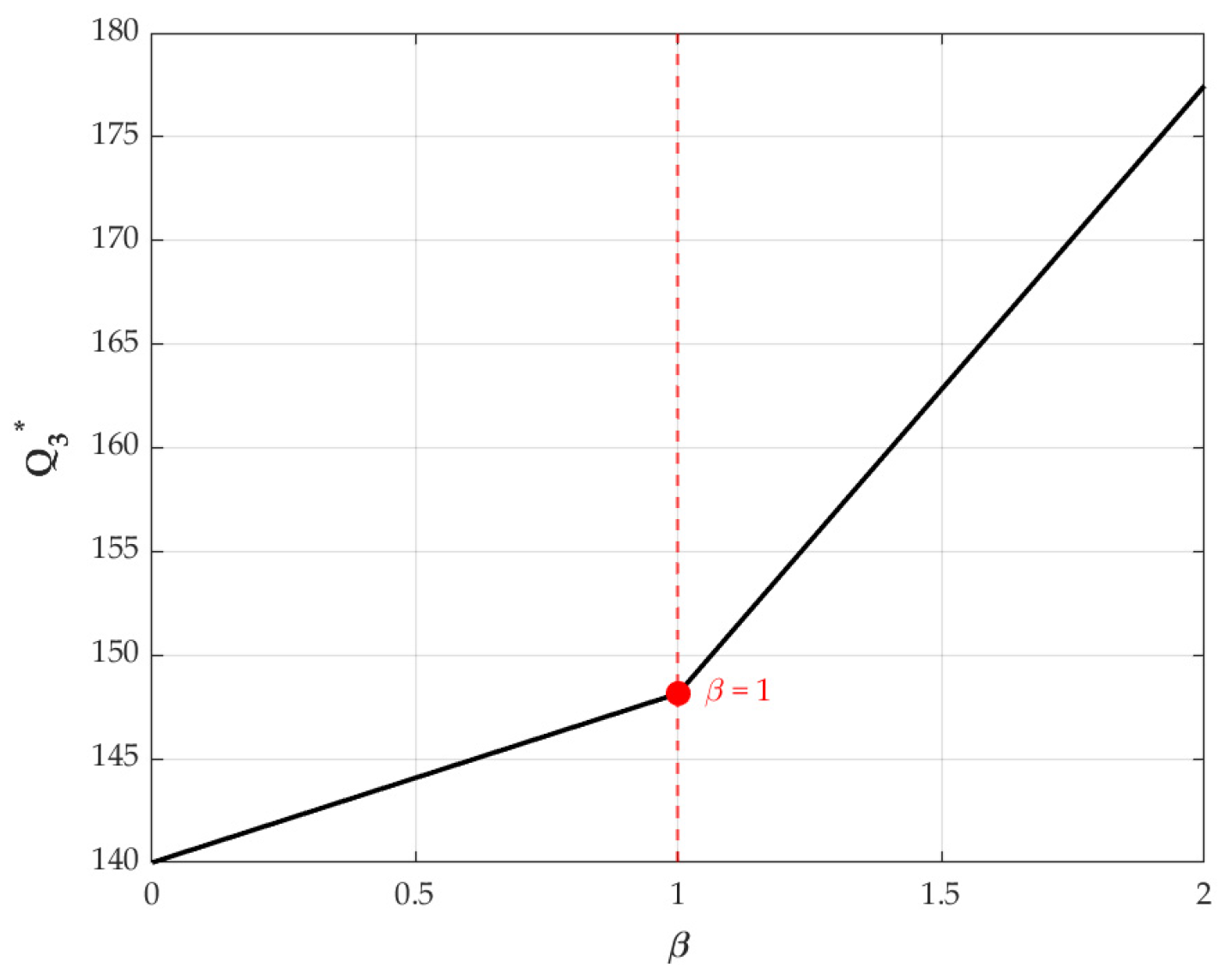

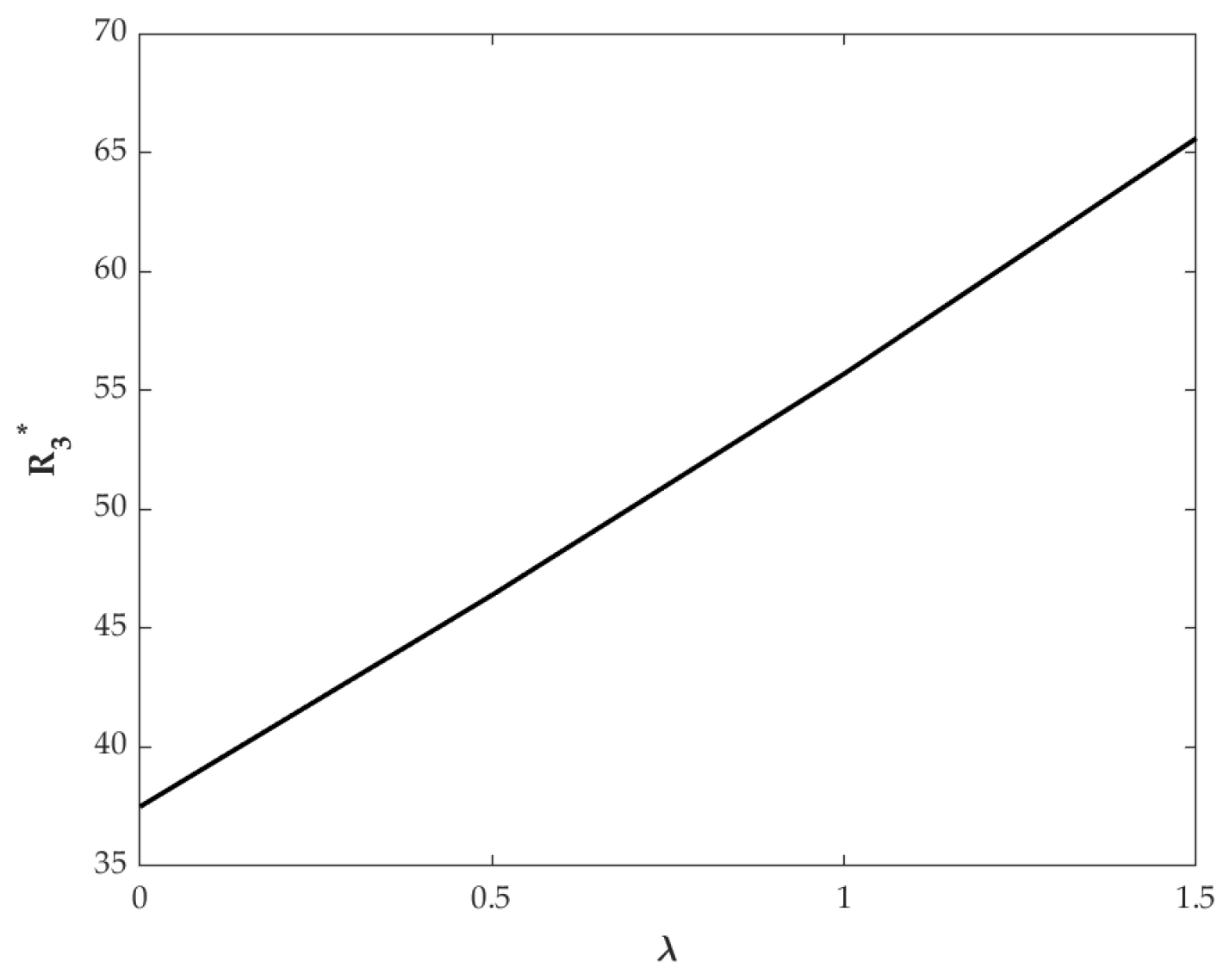

6.1. Impacts of Key Parameters on the Optimal Payment Level

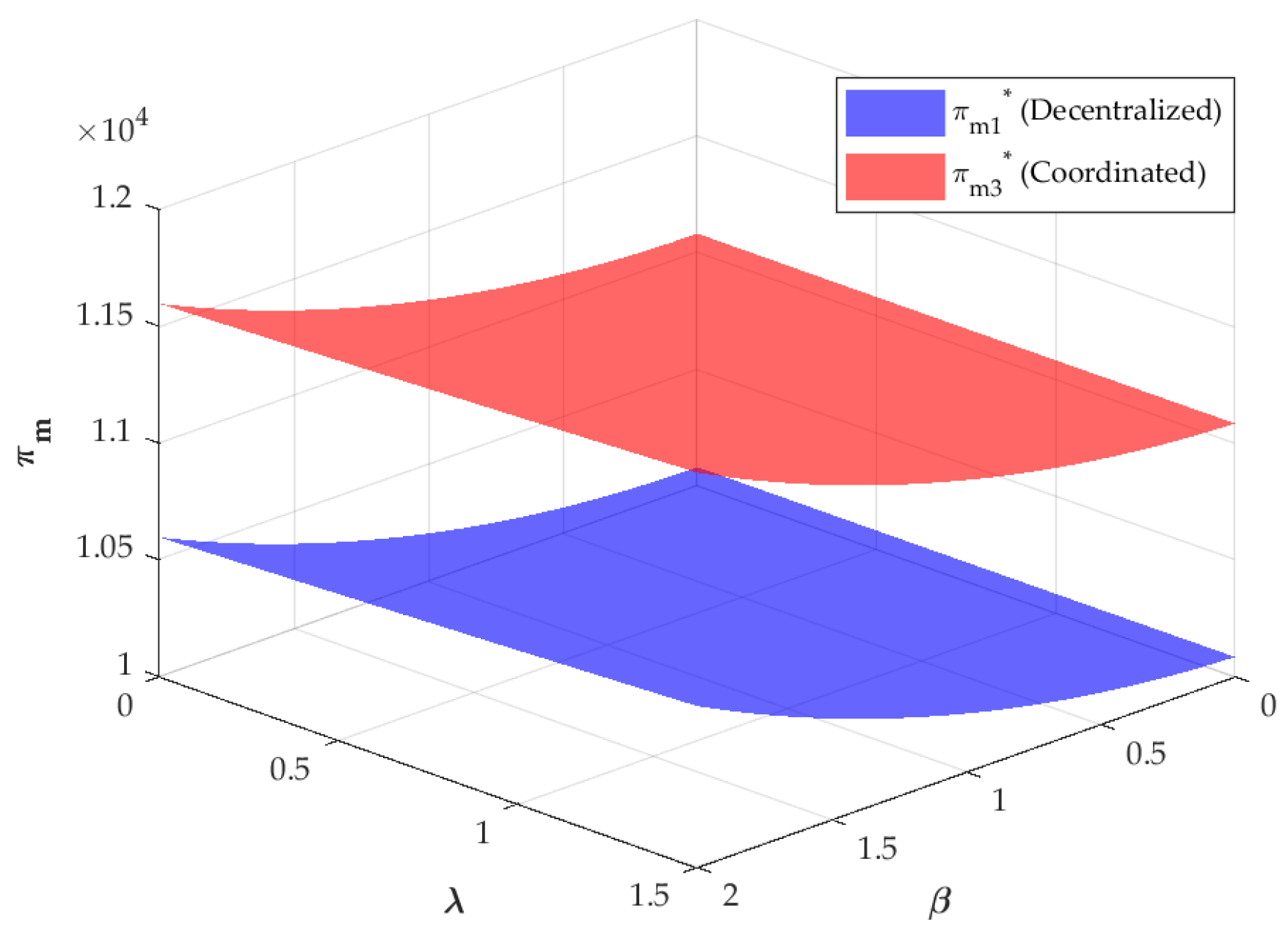

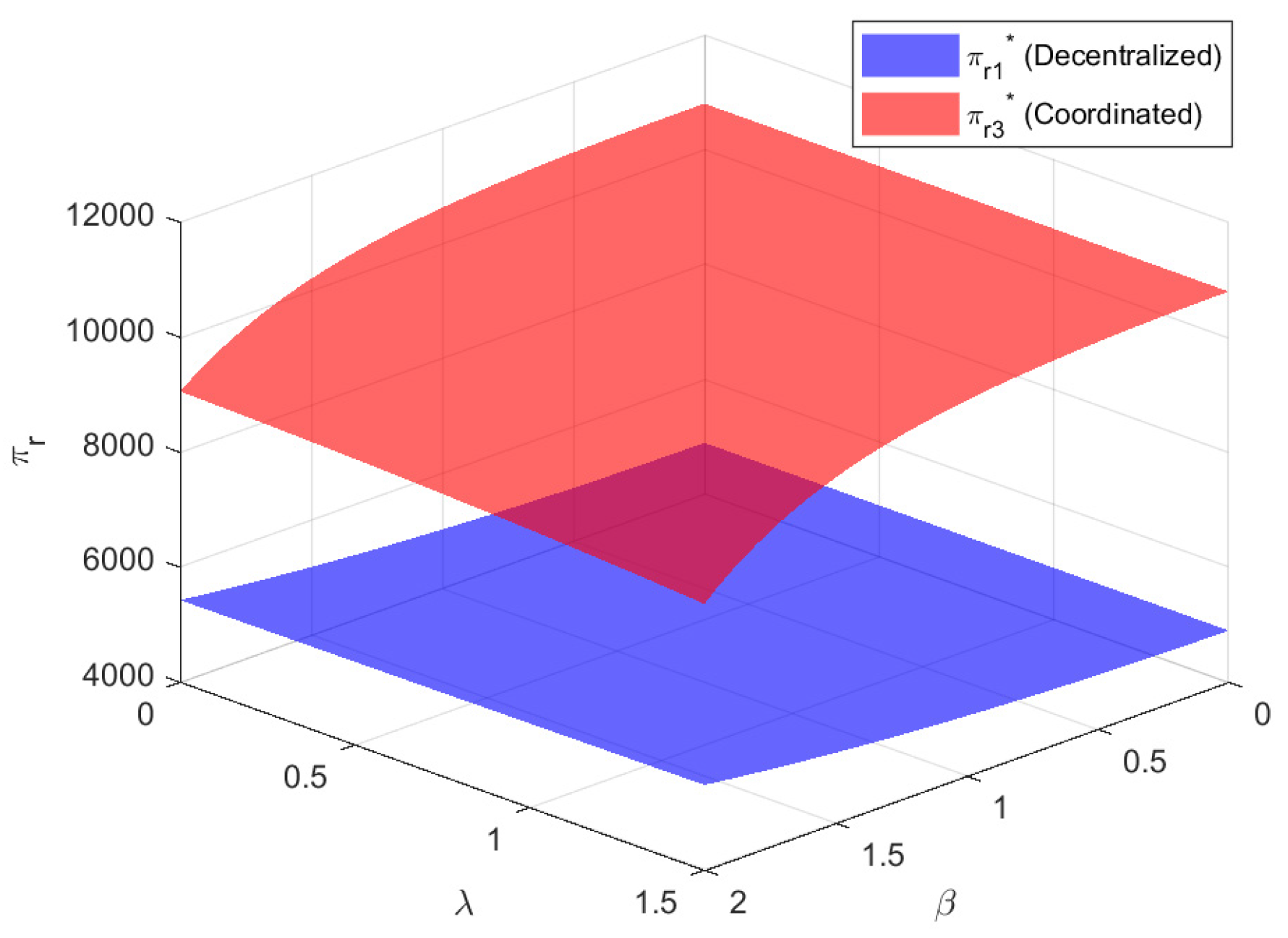

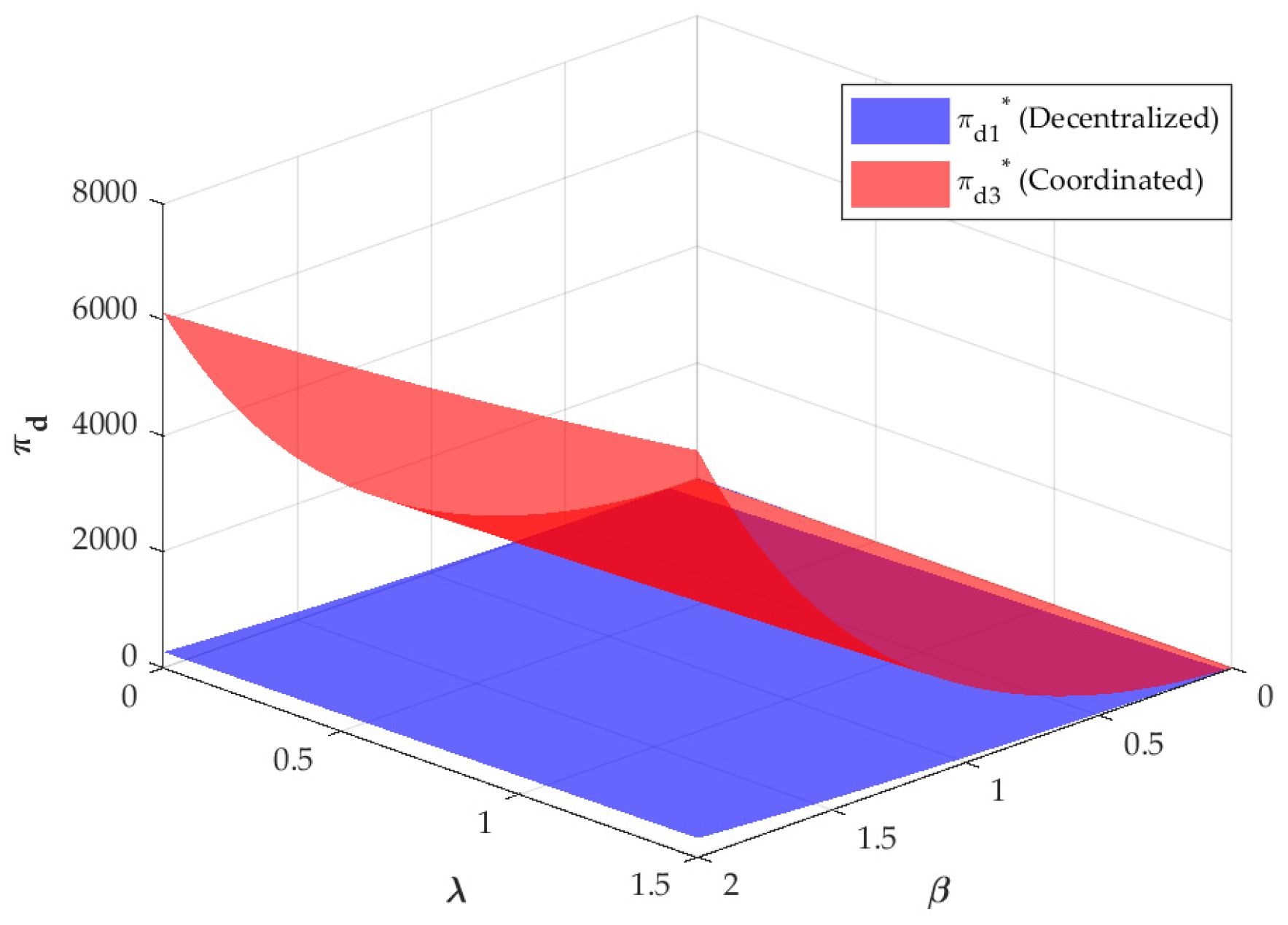

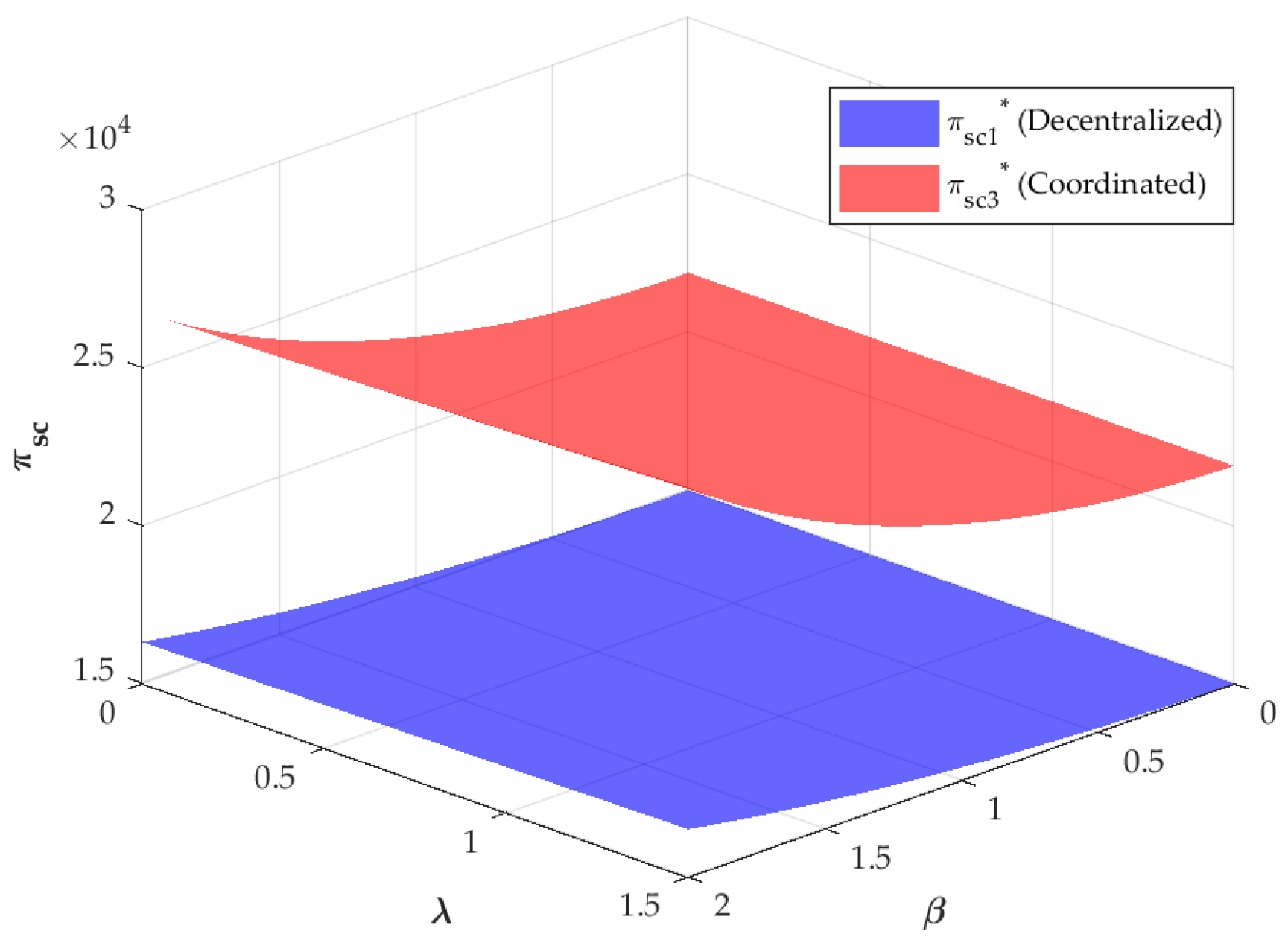

6.2. Impacts of Big Data Services on Member-Level and System-Level Profits in the CLSC

6.3. Direct and Diffusive Impacts of Big Data Services in the CLSC

7. Conclusions and Future Research Direction

- This study proposes an innovative approach and optimization framework for coordinating the participation of a BDSP in a CLSC. By thoroughly investigating the internal mechanisms of the supply chain system, it precisely identifies the specific sources of profit loss and determines two essential components of the coordination contract, thereby enriching research on supply chain coordination.

- The first necessary condition for achieving coordination in the CLSC is that the wholesale price equals the unit cost of new products. When the manufacturer wholesales the product to the retailer at cost price, it helps boost market demand and enables the equilibrium in decentralized decision-making to converge with the optimal level of centralized decision-making, thereby eliminating system profit loss.

- The second necessary condition requires that the unit payment level be positively correlated with several parameters. The parameters include production volume, unit cost savings, the BDSP marketing effort sensitivity coefficient, and the BDSP recycling effort sensitivity coefficient. Remanufacturing enterprises should (1) accurately assess market feedback on the service modes of the BDSP and the impacts of big data services on profitability, (2) streamline remanufacturing processes to achieve cost efficiencies, and (3) determine appropriate pricing for big data services based on actual output. This approach will fully unlock the value of big data.

- In addition, the unit payment level is also negatively correlated with several parameters. The parameters include the retail price sensitivity coefficient, the recycling price sensitivity coefficient, and the big data service cost coefficient. Remanufacturing enterprises should take measures to reduce consumer price sensitivity, especially retail price. For instance, Huawei provides value-added services during the sales process, such as extended warranties, cloud storage, and dedicated customer support, as well as door-to-door recycling service during the recycling stage. This full-lifecycle service design enhances consumer experience and perceived value, reducing price sensitivity and encouraging both product purchase and participation in recycling programs.

- BDSPs create greater benefits for CLSCs by assisting with both marketing and recycling. A BDSP enhances marketing effectiveness not only by leveraging its robust data mining capabilities to facilitate product transformation and upgrading, ensuring products better align with consumer preferences, but also by implementing targeted marketing strategies for diverse consumer segments. This significantly improves the precision of marketing campaigns, driving growth in both supply chain sales volume and overall profitability. Simultaneously, the positive impacts of marketing assistance indirectly lower waste recycling costs by reducing the recycling price, thereby decreasing the manufacturer’s recycling expenses. Furthermore, the BDSP’s assistance in recycling helps optimize the recycling process and promotes consumer participation in recycling activities through publicity, thereby increasing the volume of recycled waste and bringing more economic and environmental benefits to the CLSC. Additionally, recycling assistance exerts a diffuse influence on the product sales process, leading to a higher retail price and increased sales revenue. Marketing sensitivity has a stronger impact on pricing decisions than recycling sensitivity. The market responds more actively to marketing-oriented data services.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Proof of the Equilibrium Solutions in the Decentralized Decision-Making Model

Appendix A.2. Proof of the Equilibrium Solutions in the Centralized Decision-Making Model

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix B.2. Proof of Proposition 2

Appendix B.3. Proof of Proposition 3

Appendix B.4. Proof of Proposition 4

References

- Mariani, M.M.; Fosso Wamba, S. Exploring how consumer goods companies innovate in the digital age: The role of big data analytics companies. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Han, F.; Liu, H. Challenges of Big Data analysis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2014, 1, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P. Pricing Strategies of a Three-Stage Supply Chain: A New Research in the Big Data Era. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2017, 2017, 9024712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Wang, D.; Liang, S. Dynamic game strategies and coordination of closed-loop supply chain considering product remanufacturing and goodwill in the big data environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 16469–16502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Ran, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W. Data-driven approaches to integrated closed-loop sustainable supply chain design under multi-uncertainties. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Xu, M. Dynamic cooperation strategies of the closed-loop supply chain involving the internet service platform. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Hu, J. Research on Collaborative Management Strategies of Closed-Loop Supply Chain under the Influence of Big-Data Marketing and Reference Price Effect. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Guo, F.; Tang, H.; Chen, X. Research on Coordination Complexity of E-Commerce Logistics Service Supply Chain. Complexity 2020, 2020, 7031543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lang, H. Coordinating a platform supply chain with reference promotion effect and Big Data marketing. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2024, 58, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiri, Y.; Beidouri, Z.; Oumami, M.E. Coordination Contracts and Their Impact on Supply Chain Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. Eng. Proc. 2025, 97, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A.; Toyasaki, F. Reverse supply chain management and electronic waste recycling: A multitiered network equilibrium framework for e-cycling. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2005, 41, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Q.; Ke, K.; Anderson, T.; Dong, J. The closed-loop supply chain network with competition, distribution channel investment, and uncertainties. Omega 2013, 41, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, B.; Zhang, D. Closed-Loop Supply Chain Network Equilibrium Model with Subsidy on Green Supply Chain Technology Investment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, G. Closed-loop supply chain network equilibrium strategy model with environmental protection objectives. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 18, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargetta, G.; Scrimali, L.R.M. A sustainable dynamic closed-loop supply chain network equilibrium for collectibles markets. Comput. Manag. Sci. 2023, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Chen, B.; Veglianti, E. Platform Service Supply Chain Network Equilibrium Model with Data Empowerment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, W. Necessary conditions for coordination of dual-channel closed-loop supply chain. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 151, 119823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.K.; Kundu, K.; Das, P. Digital technology based game-theoretic pricing strategies in a three-tier perishable food supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, K.J. Beating the Algorithm: Consumer Manipulation, Personalized Pricing, and Big Data Management. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2023, 25, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shivendu, S.; Wang, P. Is Investment in Data Analytics Always Profitable? The Case of Third-Party-Online-Promotion Marketplace. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 2321–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeeli, Z.; Mollaverdi, N.; Safarzadeh, S. A game theoretic approach for green supply chain management in a big data environment considering cost-sharing models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 124989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Shu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, H. Big data service investment choices in a manufacturer-led dual-channel supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Zou, Z. Better Demand Signal, Better Decisions? Evaluation of Big Data in a Licensed Remanufacturing Supply Chain with Environmental Risk Considerations. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 1550–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, C. Research on digital empowerment, innovation vitality and manufacturing supply chain resilience mechanism. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ameer, I.; Hussain, M.S.; Gill, S.S.; Usama, A. Sustainable supply chain management performance in post COVID-19 era in an emerging economy: A big data perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 5900–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A. Big data-driven supply chain performance measurement system: A review and framework for implementation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Xu, M. Dynamic game strategies of a two-stage remanufacturing closed-loop supply chain considering Big Data marketing, technological innovation and overconfidence. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 145, 106538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Hu, J.; Yao, F. Big data empowering low-carbon smart tourism study on low-carbon tourism O2O supply chain considering consumer behaviors and corporate altruistic preferences. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 153, 107061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yi, S.-p. Pricing policies of green supply chain considering targeted advertising and product green degree in the Big Data environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedan, M.; Mafakheri, F. Predictive big data analytics for supply chain demand forecasting: Methods, applications, and research opportunities. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chiang, R.H.L.; Storey, V.C. Business Intelligence and Analytics: From Big Data to Big Impact. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, F.-J. Pricing strategies of dual-channel green supply chain considering Big Data information inputs. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 2981–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Ying, L.; Ping, J.; Liu, H. Understanding big consumer opinion data for market-driven product design. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 3019–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Shanthikumar, J.G. How Research in Production and Operations Management May Evolve in the Era of Big Data. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1670–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestino, A.; Prete, M.I.; Piper, L.; Guido, G. Internet of Things and Big Data as enablers for business digitalization strategies. Technovation 2020, 98, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chunming, Y.; Guo, J. Optimisation of remanufacturing supply chain with dual recycling channels under improved deep reinforcement learning algorithm. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2024, 11, 2396432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y. Research on the big data information sharing in closed-loop supply chain with triple-channel recycling. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2024, 58, 681–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Sagnak, M.; Mangla, S.K.; Sezer, M.D.; Pala, M.O. A fuzzy based hybrid decision framework to circularity in dairy supply chains through big data solutions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 170, 120927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Feng, L. The influence of big data system for used product management on manufacturing–remanufacturing operations. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Dai, H.; Tian, G.; Xie, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, H. Big-Data-Based Power Battery Recycling for New Energy Vehicles: Information Sharing Platform and Intelligent Transportation Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 99605–99623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin Cheng, T.C.; Kamble, S.S.; Belhadi, A.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Lai, K.H.; Kharat, M.G. Linkages between big data analytics, circular economy, sustainable supply chain flexibility, and sustainable performance in manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 6908–6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Q.; Preston, D.S.; Swink, M. How Big Data Analytics Affects Supply Chain Decision-Making: An Empirical Analysis. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 22, 1224–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hao, C.; Yang, X. Pricing and Carbon Emission Reduction Decisions Considering Fairness Concern in the Big Data Era. Procedia CIRP 2019, 83, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Mishra, N.; Shukla, N. Big data analytics and application for logistics and supply chain management. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 114, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yi, S.-P. Investment Decision-Making and Coordination of Supply Chain: A New Research in the Big Data Era. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2016, 2016, 2026715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, H. Investment decision-making of closed-loop supply chain driven by big data technology. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2023, 19, 4381–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yi, S.-p. Investment decision-making and coordination of a three-stage supply chain considering Data Company in the Big Data era. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakal, I.S.; Akcali, E. Effects of Random Yield in Remanufacturing with Price-Sensitive Supply and Demand. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2006, 15, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaskan, R.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Closed-Loop Supply Chain Models with Product Remanufacturing. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Q. Carbon emission reduction and product collection decisions in the closed-loop supply chain with cap-and-trade regulation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 4359–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, G. Manufacturer vs. Consumer Subsidy with Green Technology Investment and Environmental Concern. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 287, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, C. Differential game and coordination of a three-echelon closed-loop supply chain considering green innovation and big data marketing. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2025, 59, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Unit cost of new products | |

| Unit cost of remanufactured products | |

| Market baseline demand | |

| Retail price sensitivity coefficient | |

| Recycling price sensitivity coefficient | |

| BDSP marketing effort sensitivity coefficient | |

| BDSP recycling effort sensitivity coefficient | |

| Big data service cost coefficient | |

| Decision variables | |

| Wholesale price | |

| Recycling price | |

| Manufacturer’s payment level for big data services | |

| Retail price | |

| Service effort level of the BDSP | |

| Profits of the manufacturer, retailer, BDSP and CLSC | |

| Decentralized decision-making model, centralized decision-making model and optimization analysis of coordination conditions |

| Efficiency | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 5 | 200 | 1 | 4 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 10 | 15 | 67.8 | 8746.6 | 12,978.6 | 67.4% |

| 20 | 5 | 200 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 90.6 | 8456.3 | 21,862.5 | 38.7% |

| 20 | 5 | 300 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1.5 | 10 | 20 | 80.6 | 20,045.7 | 25,336.3 | 79.1% 1 |

| Efficiency | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 5 | 300 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1.5 | 10 | 20 | 374.6 | 25,336.3 | 25,336.3 | 99.9% 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Shi, L. Lowering the Threshold for Integration of Big Data Services into Closed-Loop Supply Chain: Necessary Conditions Based on the Variational Inequality Approach. Systems 2026, 14, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010050

Yuan Y, Shi L. Lowering the Threshold for Integration of Big Data Services into Closed-Loop Supply Chain: Necessary Conditions Based on the Variational Inequality Approach. Systems. 2026; 14(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Yanhong, and Liqin Shi. 2026. "Lowering the Threshold for Integration of Big Data Services into Closed-Loop Supply Chain: Necessary Conditions Based on the Variational Inequality Approach" Systems 14, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010050

APA StyleYuan, Y., & Shi, L. (2026). Lowering the Threshold for Integration of Big Data Services into Closed-Loop Supply Chain: Necessary Conditions Based on the Variational Inequality Approach. Systems, 14(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010050