1. Introduction

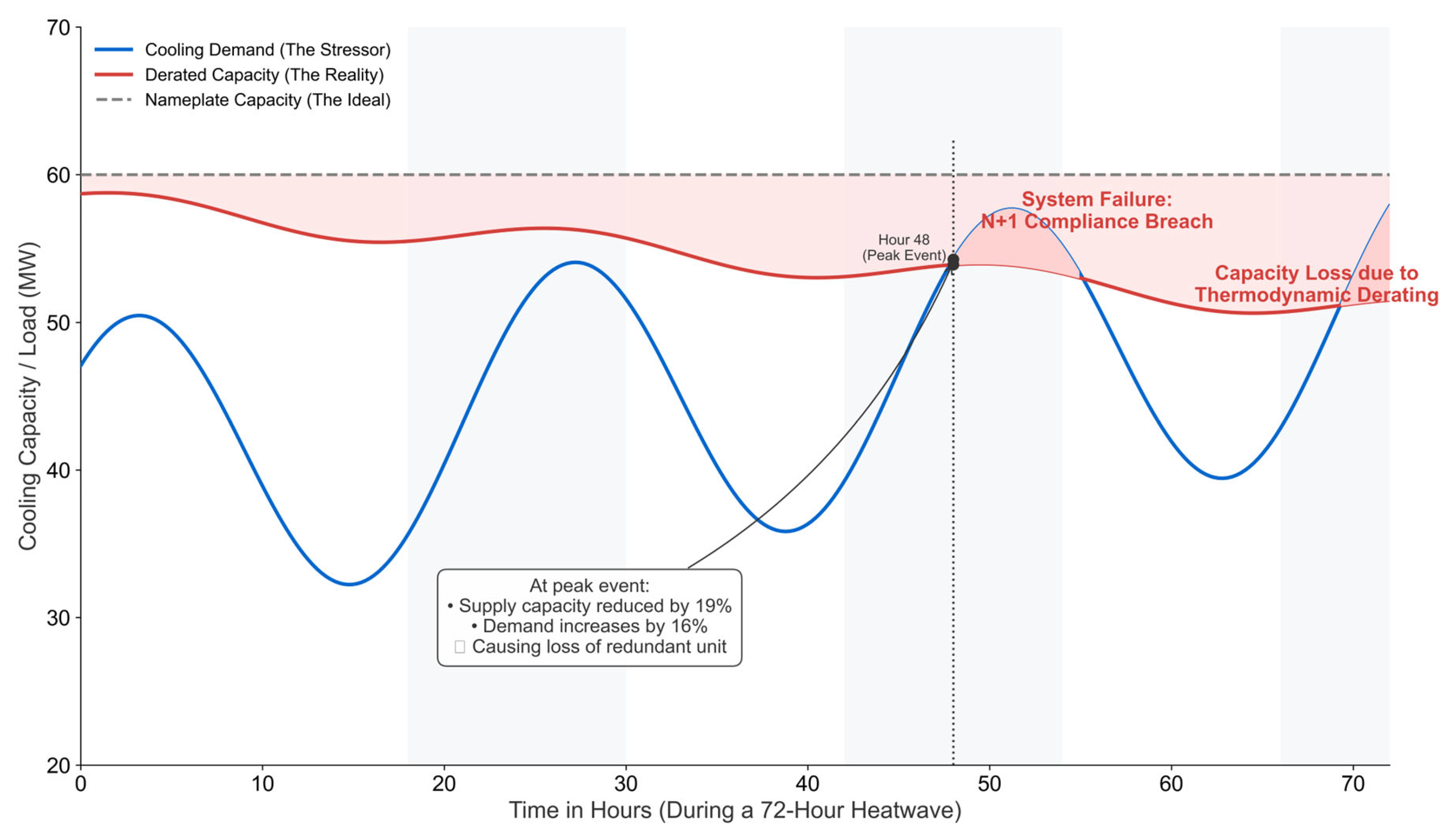

Recent analyses indicate that exceeding certain climate thresholds often leads to catastrophic failures in cooling systems, power networks, and site hydrology. In mission-critical digital infrastructure, such failures lead to outages costing millions of dollars, as extreme heat causes an abrupt loss of fault tolerance that far surpasses incremental degradation [

1,

2]. Despite this physical reality, traditional risk assessment frameworks—such as ESG ratings and Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs)—tend to misprice this risk by treating it as a linear operational challenge rather than a nonlinear systemic threat [

3,

4,

5]. This mispricing occurs at multiple levels; just as physical failure thresholds are overlooked at the asset level, the systemic financial instability caused by climate volatility is often unaccounted for in conventional risk models [

6]. Consequently, infrastructure owners and investors are currently facing a ‘Global Adaptation Gap.’ While projections estimate this gap to surpass US

$310–365 billion annually by 2035, it represents not merely a funding shortfall but a fundamental failure in pricing, rooted in the structural limitations of conventional models to properly value thermodynamic boundaries [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The foundational flaw in the prevailing approach is its reliance on linear assumptions. Top-down models that link warming to economic loss often assume a smooth, incremental relationship, effectively treating climate change as a marginal increase in operating expenditure (

). This assumption is invalidated not only by empirical studies demonstrating that economic activity is non-linearly coupled to climate [

12,

13], but also by critiques highlighting the inadequacy of linear damage functions in capturing systemic risks [

10,

14]. More fundamentally, the laws of thermodynamics dictate that for mission-critical infrastructure, the primary threat is not a gradual erosion of performance but a sudden, non-linear breakdown once physical limits are breached [

15].

This distinction shifts the perspective from probabilistic risk management to deterministic liability accounting, which necessitates quantifying the precise capital premium required to avert failure. Conventional frameworks regard climate impacts as a ‘tail risk’—an event characterized by low probability but high severity [

16]. Nonetheless, the laws of thermodynamics specify that for an engineered system subjected to a known future thermal stressor exceeding its design parameters, failure is not a matter of probability; rather, it is an inevitable event [

17]. Although the probability of such a scenario occurring remains probabilistic, conditioned upon that scenario, failure is certain [

18]. Consequently, this transforms the ‘risk’ into a deterministic future liability that, under established principles of financial prudence, necessitates valuation today [

19].

To operationalize the valuation of this future liability, this study addresses two central questions: (1) How do non-linear thermodynamic limits render existing probability-based risk models obsolete? (2) What is the precise capital premium required to engineer out these deterministic failures?

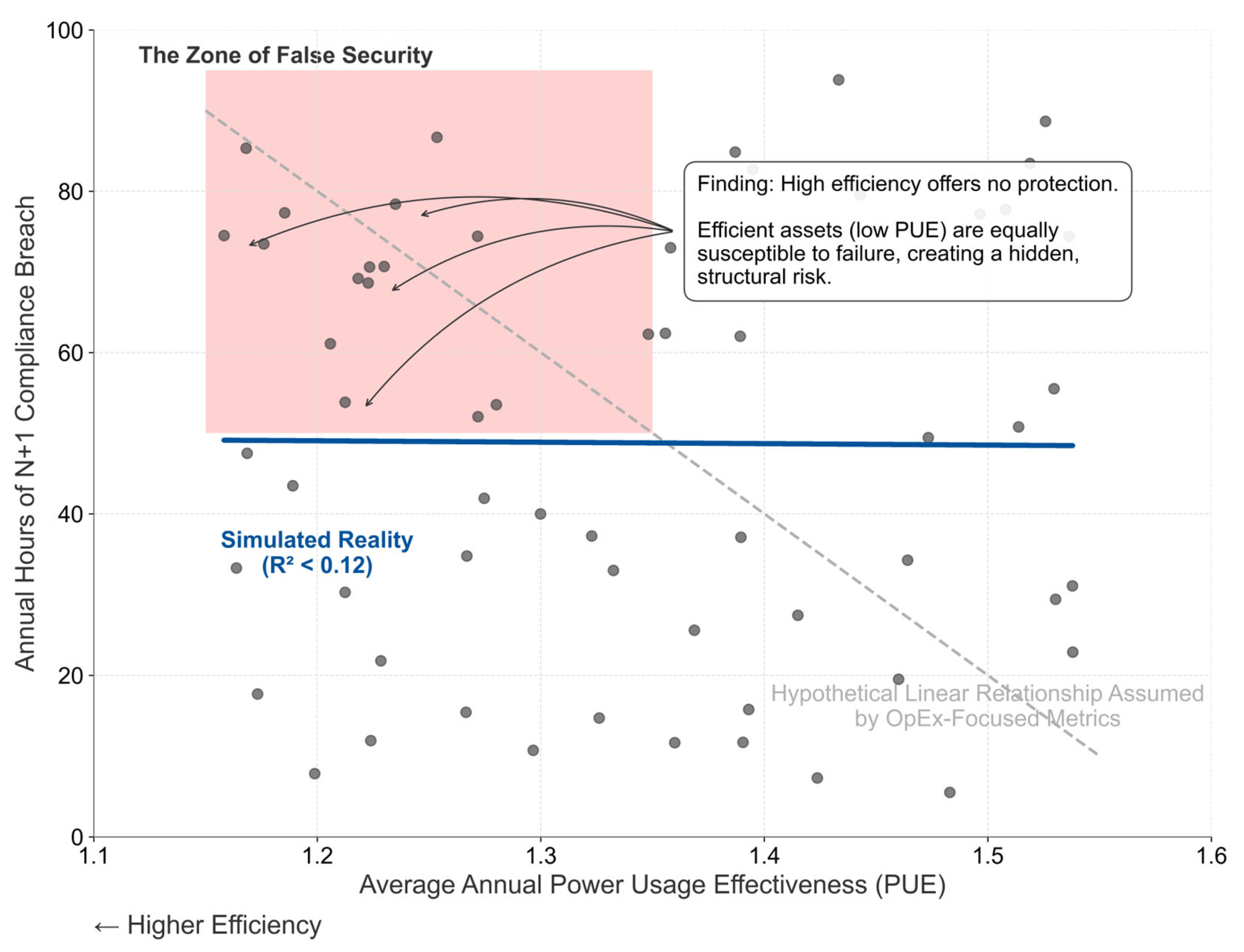

While these thermodynamic limits apply to any engineered system—from power turbines to industrial manufacturing—this vulnerability is most immediate in mission-critical digital infrastructure, which we use here as an ideal laboratory for analysis. Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), the dominant industry metric for preparedness, dangerously misleads by ignoring deterministic capital risks in its focus on historical efficiency [

20]. Nowhere is this vulnerability more acute than in the sector’s reliance on continuous cooling, which creates a direct, financially material exposure to the non-linear thermodynamic failures analyzed in this study [

1,

2].

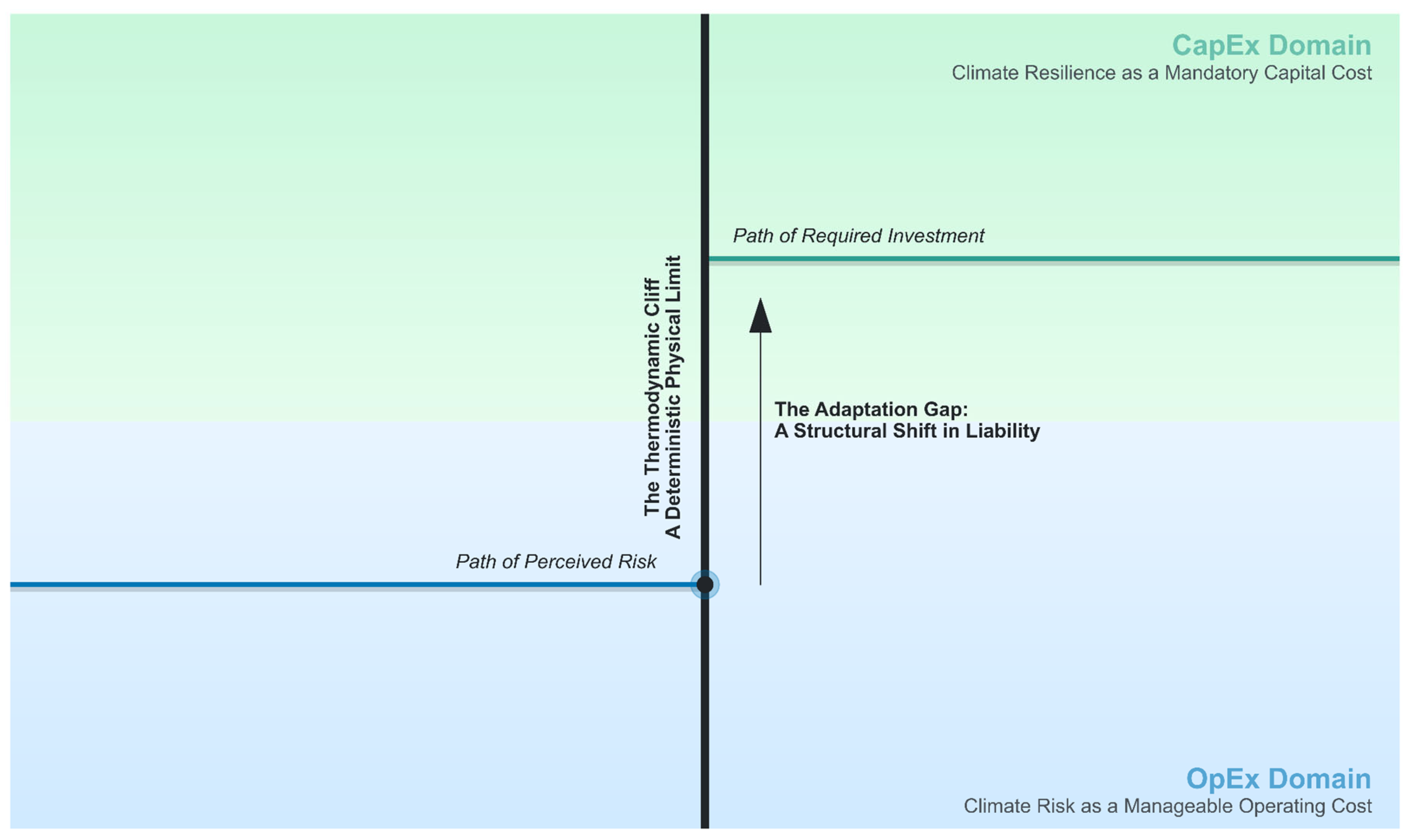

This reality necessitates a shift from probabilistic risk assessment to deterministic cost analysis. To encapsulate this deterministic reality, we introduce two core concepts. First, the

“Thermodynamic Cliff” is a tangible physical threshold beyond which an asset’s cooling demand surpasses its diminishing operational capacity, rendering it non-compliant. Surpassing this boundary invalidates the conventional view of climate risk as a manageable operational expenditure (OpEx), forcing a paradigm shift to one of mandatory capital investment (CapEx) to ensure resilience. This structural shift in liability creates what we define as the

“Adaptation Gap”: a quantifiable, unbooked capital liability representing the cost premium required to upgrade an asset’s physical design to maintain its specified fault tolerance under projected future climate conditions. As illustrated in the conceptual model in

Figure 1, the Thermodynamic Cliff is the deterministic boundary compelling this leap, and the Adaptation Gap quantifies the required capital investment to bridge the delta between legacy design standards and future climate reality.

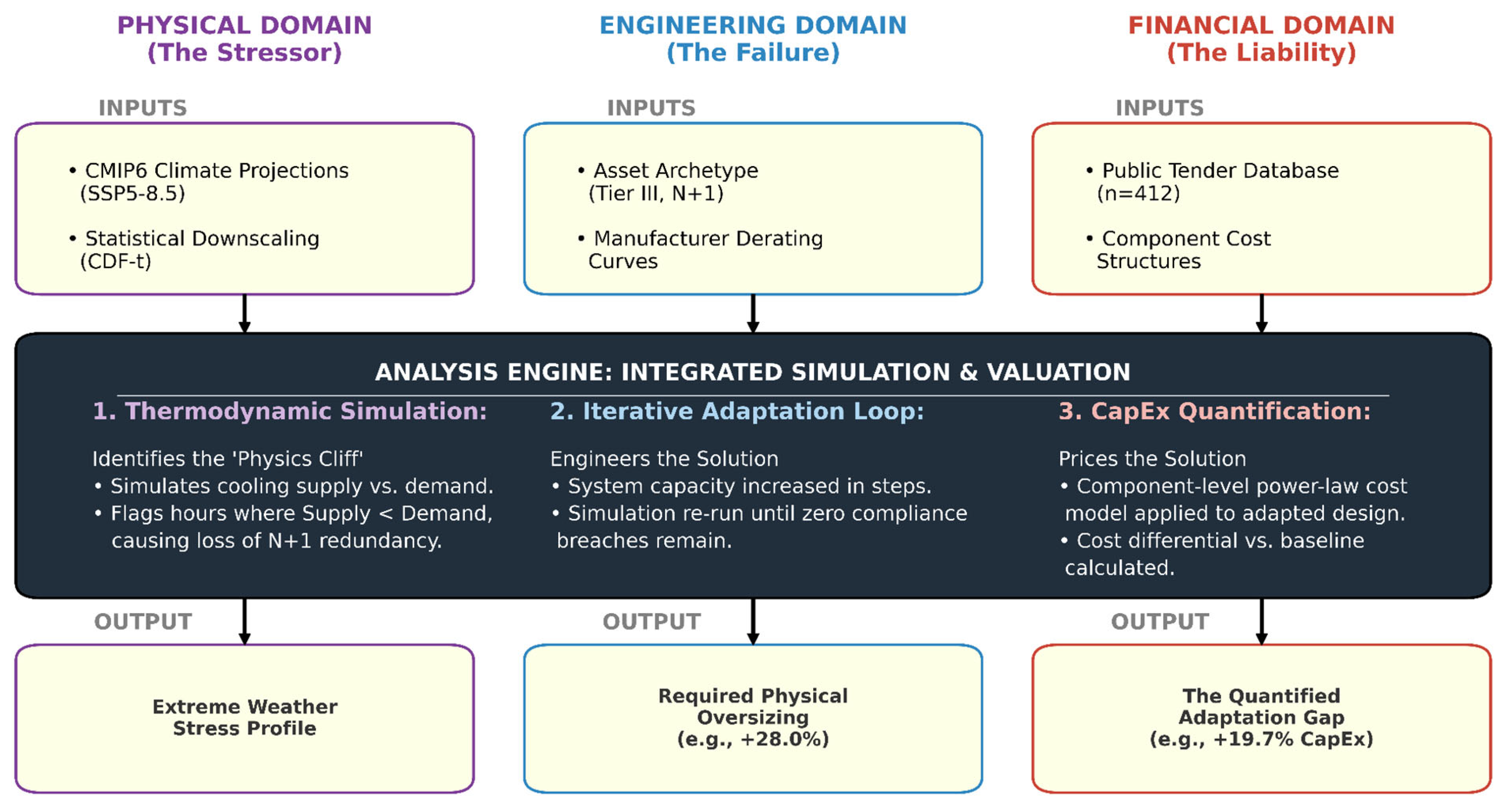

To price the Adaptation Gap for digital infrastructure—a sector in which thermal limits force a binary choice between service continuity and operational failure—our methodology shifts from probabilistic risk assessment to deterministic cost analysis. This approach is grounded in the principle of “stress-testing,” the standard practice for mission-critical engineering where system failure carries severe consequences. Unlike probabilistic models that focus on likely outcomes, a stress test is designed to evaluate whether a system can maintain function under plausible worst-case conditions. To construct this deterministic test, our framework integrates three critical data layers: (1) CMIP6 climate projections representing ‘tail-risk’ scenarios—high-impact, low-probability events at the extremes of the probability distribution (SSP5-8.5) [

20,

21]; (2) manufacturer-verified engineering derating curves to simulate physical failure; and (3) an empirically derived, power-law cost model to price the required adaptation [

22,

23].

The primary contribution of this paper is a replicable, physics-first valuation framework that transforms the capital liability arising from climate risk from a nebulous operational concern into a specific, auditable capital liability. Our analysis, using this framework, demonstrates that even modern, high-efficiency (Tier III) data centers built to current standards will experience a loss of fault tolerance during future heatwaves. We argue that closing the Adaptation Gap requires a material, unbooked CapEx premium for the mechanical plant, revealing a systemic under-capitalization of digital infrastructure. This paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 deconstructs the theoretical failures of prevailing risk paradigms.

Section 3 details our quantitative methodology.

Section 4 presents the results, visualizing the failure mechanism and quantifying the Adaptation Gap. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the implications of this liability for asset valuation, financial risk, and public policy.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study directly challenge the prevailing paradigms of climate risk assessment in finance and real estate. By demonstrating a deterministic capital expenditure premium of 19.7% is necessary to maintain engineering reliability, our analysis shifts the conversation from probabilistic “risk” to structural “cost.” We interpret this “Adaptation Gap” from three perspectives: (1) the mispricing of thermodynamic risk, (2) the immediate implications for asset valuation, and (3) the emerging need for new public policy.

5.1. The Mispricing of Thermodynamic Risk: From to

Our fundamental discovery—that a low Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) does not prevent thermodynamic failure—exposes a critical error in risk valuation. This finding challenges the assumptions in high-level economic models used to guide climate policy. In line with critiques from Bressan et al. [

54] and Vogl et al. [

55], our research shows that Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), which lack asset-level detail, are unfit for capturing the non-linear failure points of critical infrastructure. This unfitness extends beyond physical asset failure; recent econometric evidence demonstrates that temperature shocks also propagate through the financial system to heighten systemic risk, a non-linear financial channel that high-level models are ill-equipped to capture [

6]. Current ESG frameworks, which focus on efficiency metrics, treat climate exposure as an operational expenditure (OpEx) problem of higher energy bills. Our analysis shows this view is dangerously incomplete. For critical infrastructure, the main threat is not a marginal rise in OpEx, but the loss of capital equipment function leading to service-level breaches and mandatory capital reinvestment (CapEx).

The “Physics Cliff” is a capital expenditure event. It marks the point where an asset, however efficient, becomes physically obsolete because it was designed for a climate that no longer exists. This vulnerability is getting worse, as documented by Charaf et al. [

41] and Isazadeh et al. [

30], rising data center power densities increase internal heat loads, making these systems ever more susceptible to rising ambient temperatures. Therefore, the 19.7% premium is not just a future risk but a current, unbooked liability. It is the cost of fixing a design flaw based on outdated climate data. This 19.7% premium on mechanical systems, which typically account for 15–20% [

56] of a data center’s total construction budget, translates into a material 3–4% increase in total project cost, directly impacting investment returns. This observation indicates that a large portion of global digital infrastructure, while appearing “green” on paper, is physically “pre-stranded”—rendered obsolete by future climate conditions long before its expected financial depreciation.

The persistence of this valuation gap can be attributed to several systemic factors. First, informational silos create a structural disconnect between engineers, who understand component-level physical thresholds, and financial analysts, whose valuation models often lack the granularity to incorporate them. Second, institutional incentives are misaligned; financial markets often prioritize short-term operational expenditure (OpEx) efficiencies—rewarded by metrics like PUE—over long-term capital expenditure (CapEx) resilience, which protects against future, unpriced liabilities. Finally, the prevalent risk frameworks themselves, including IAMs and many ESG rating systems, suffer from a granularity deficit, preventing them from capturing the nonlinear, component-level failure points where risk materializes. Furthermore, the physical reality is likely more severe than our ideal model suggests. As demonstrated in

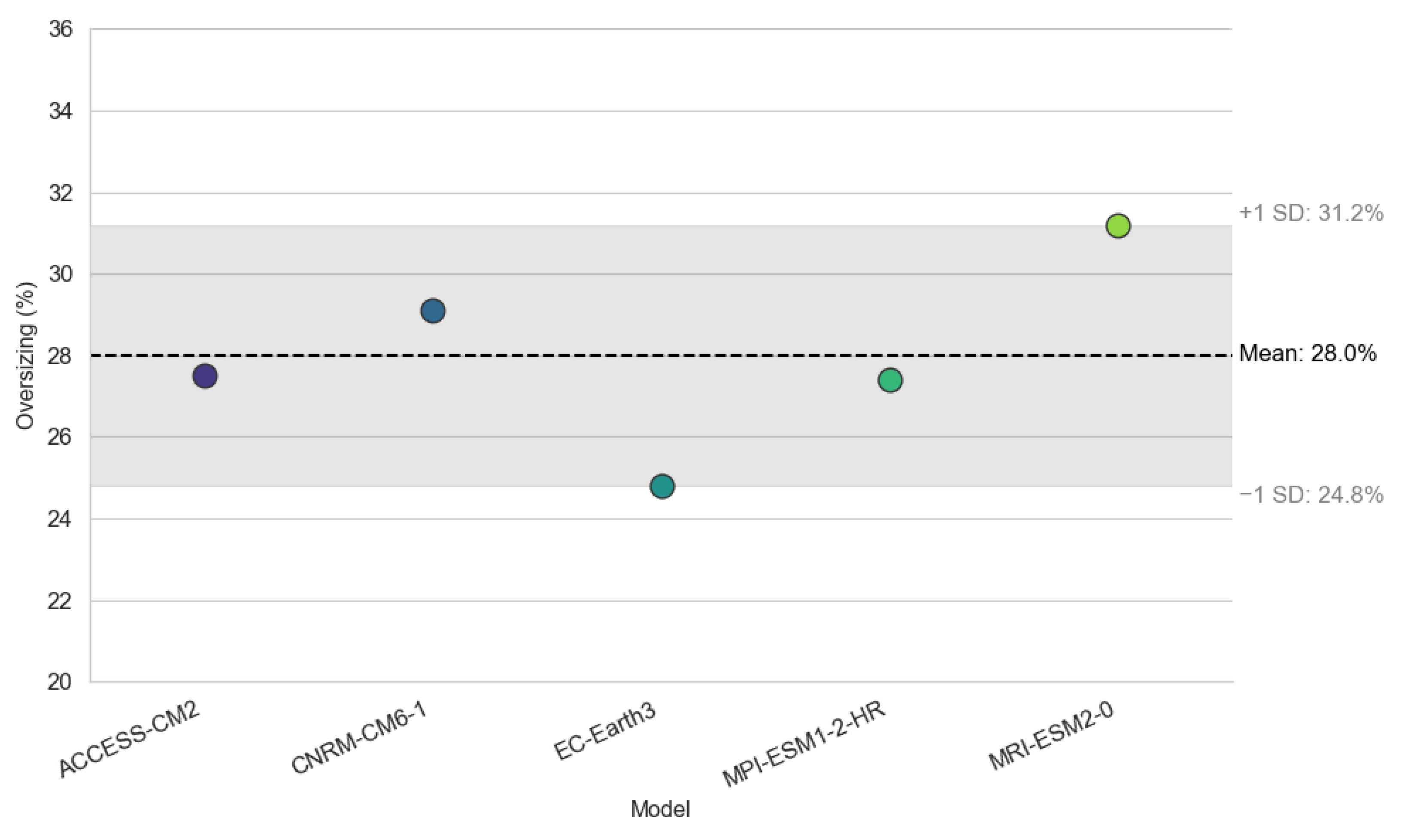

Section 4.5, standard in-service performance degradation amplifies the Adaptation Gap from 19.7% for new assets to a more realistic, albeit simplified, estimate of 28.7% for existing assets. This evidence indicates that although the liability for a new asset is 19.7%, the actual, unaccounted liability for an aging asset is significantly higher, likely within the 25–30% range.

This systemic mispricing is perpetuated by a phenomenon of

“Operational Blindness”—an institutional and behavioral tendency to focus on manageable, linear operational metrics while ignoring complex, non-linear capital threats. This is driven by three intersecting forces. First, Path Dependency on institutionally embedded metrics like PUE creates a narrow focus on operational efficiency. This focus is exploited by a Principal-Agent Problem, where asset developers are incentivized to minimize upfront construction costs, thereby transferring the long-term physical liability to future owners and operators. Finally, these issues are cemented by Cognitive Bias, as decision-makers favor the familiarity of optimizing linear OpEx over the complexity of pricing long-tail CapEx risks. Together, these forces create a self-reinforcing cycle that institutionalizes the neglect of systemic physical risk. This dynamic was empirically observed during recent heatwaves, where major data centers in London and Texas experienced outages despite their high efficiency ratings, demonstrating that OpEx-focused metrics provided a poor proxy for CapEx resilience [

57,

58].

5.2. A New Blueprint for Valuation: Integrating the Adaptation Gap

The quantification of the Adaptation Gap furnishes an actionable, physics-grounded metric that can be seamlessly incorporated into conventional asset valuation procedures. Our research advances the call for physics-based infrastructure modeling [

9,

20,

33] by translating a physical performance threshold into a specific financial liability. Our central proposal is that appraisers and investment analysts modify the Replacement Cost (RC) methodology. Currently, the RC approach appraises an asset based on the cost to replace it with a “modern equivalent.” Our analysis reveals that the concept of a “modern equivalent” is itself obsolete if founded on historical climate data. Calculating a premium based on a high-warming scenario is therefore an essential corrective measure. This method aligns with established risk management principles for critical systems [

59,

60] and with regulatory frameworks like the UK Climate Projections (UKCPs), which use high-emissions scenarios as resilience benchmarks [

43].

The practical superiority of this physics-first framework resides in its specificity and actionability, which sharply contrasts with the abstract outputs produced by conventional risk assessment tools.

Table 3 provides a direct comparison between the results of the Adaptation Gap framework and those of leading ESG ratings and Integrated Assessment Models, thereby illustrating the “granularity deficit” that undermines the efficacy of such top-down methodologies.

Table 3 demonstrates that conventional tools are incapable of accurately pricing the specific, non-linear failure points where financial risk materializes. Our framework transforms an abstract physical risk into a precise, auditable capital liability. This transition from qualitative signaling to quantitative pricing is crucial for accurately valuing real assets in a non-stationary climate. Accordingly, we propose a four-step climate-corrected valuation methodology. This approach rests on two key assumptions: (1) the standard Replacement Cost (RC) is based on current market costs for like-for-like replacement, and (2) the ‘Physics Premium’ is scenario-dependent. For conservative resilience planning, we apply the premium derived from the high-impact SSP5-8.5 scenario. First, the Climate-Corrected Replacement Cost should be determined by calculating the standard Replacement Cost (RC) for the Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (MEP) systems [

23,

61]. Subsequently, the Physics Premium (e.g., +19.7%) is applied to this standard RC, resulting in the true, climate-adjusted cost of constructing a resilient, future-proofed asset. The Adaptation Gap, defined as the difference between the Climate-Adjusted RC and the standard RC, is characterized as a deferred liability. This amount signifies the capital liability that must be deducted from the asset’s current appraised value. As detailed in

Appendix A.5, this four-step methodology translates an abstract physical risk into a specific, auditable line item within a valuation report. We present this as a conceptual framework intended for integration into standard valuation procedures. Its widespread adoption, however, is likely to be facilitated by regulatory guidance from financial or appraisal standard-setting agencies. This approach provides a pragmatic method to directly incorporate climate science into financial due diligence, thereby influencing areas such as loan-to-value calculations and insurance underwriting [

62,

63].

5.3. Broader Implications: From Private Liability to Public Mandate

While this valuation framework serves as a crucial instrument for private capital, the systemic nature of the Adaptation Gap indicates that market forces alone are insufficient to guarantee the resilience of vital infrastructure. The continuity of digital services constitutes a fundamental element of economic and social stability. The recognition that assets constructed to existing engineering standards are already ‘pre-stranded’ directly challenges the adequacy of these standards.

The acknowledgment of this liability has significant implications for capital markets. An industry-wide acknowledgment of the Adaptation Gap could prompt a systemic re-evaluation of infrastructure assets, differentiating resilient from vulnerable portfolios. In regions experiencing high warming, this unpriced liability risks rendering new developments, built to inadequate standards, uninsurable against business interruptions [

55,

56] and consequently, uninvestable. Such potential market disruption driven by private capital re-pricing highlights the inadequacy of current public standards.

The presence of this quantifiable private liability necessitates a reassessment of public policies concerning national building codes and infrastructure resilience standards. It provides a compelling rationale for regulators to require the disclosure of the Adaptation Gap for critical infrastructure assets, thereby providing investors with decision-useful, forward-looking information presently absent from financial reports. For directors and fiduciaries, neglecting this foreseeable liability may soon be regarded as a breach of their duty of care, introducing a new dimension of climate-related legal and regulatory risks. However, establishing a public mandate faces considerable implementation challenges, including the need to revise national building codes, standardize regional climate projections for engineering design, and address industry inertia.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the predominant linear and efficiency-based frameworks for evaluating physical climate risk are insufficient for critical infrastructure. By integrating high-fidelity climate science with deterministic engineering and cost modeling, we have shown that the principal financial threat from extreme heat is not operational but capital in nature. Engineering a new data center to maintain fault tolerance requires a 19.7% (95% CI: 16.5–22.9%) Adaptation Gap premium, a figure that rises to 28.7% for aging assets, representing a significant, unbooked liability on the balance sheets of investors and operators.

The core theoretical and practical contribution of this work is the translation of abstract physical risks into a tangible, auditable capital liability. This moves the field from probabilistic risk assessment to deterministic boundary analysis and provides a blueprint for a new standard of climate-adjusted valuation, enabling investors to distinguish between resilient and “pre-stranded” assets.

While this study establishes a robust physics-first framework, its limitations delineate a clear trajectory for future research. First, the 19.7% premium is derived from the thermal failure pathway of chilled-water architectures in humid-subtropical climates (using Istanbul as a proxy, this study relies heavily on a single Tier III archetype); it should not be extrapolated uncritically to air-cooled systems in arid regions or liquid-cooling architectures without further validation. Second, the empirical cost model should be calibrated with regional data beyond Turkey to improve global generalizability. Third, the specific quantitative failure thresholds are based on an empirically calibrated but fixed IT load profile; variations in operational intensity or cooling system configuration would alter these results and warrant further study. Finally, future iterations should integrate dynamic degradation models to simulate the ‘as-operated’ performance cliff with greater fidelity.

The final implication of this research is a definitive directive for climate finance. The “Thermodynamic Cliff” is not a risk to be managed but a physical boundary to be priced. By acknowledging this boundary, the financial community can transition from retrospective signaling to prospective, physics-grounded valuation.