A Decoupling-Fusion System for Financial Fraud Detection: Operationalizing Causal–Temporal Asynchrony in Multimodal Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fraud Drivers and Fraud Typologies

2.2. Structured Data and Static Fraud Analytics

2.3. Temporal Modeling of Fraud Evolution

2.4. Unstructured Data Mining and Multimodal Fusion Strategies

2.5. CTA Positioning and Research Gap

3. Methodology and System Design

3.1. Theoretical Cornerstone

- Motive signals are chronic, span multiple periods, and appear in longitudinal sequences that reflect an evolutionary process.

- Action signals are acute, concentrated in a single year, and appear as cross-sectional snapshots that reflect abnormal configurations.

3.2. Feature Dimension Construction

3.2.1. Chronic Dimension: Quantifying Motive

- (1)

- Financial Dynamic Features ()

- First, 33 classic ratios spanning profitability, solvency, operating efficiency, cash-flow quality, growth, and cross-statement consistency are calculated as baselines and included as a benchmark subset. An expanded pool is generated from the three financial statements by removing line items with missingness , collapsing perfectly redundant series, and forming one ratio for each remaining unordered item pair (the item with the larger sample mean over available observations is used as the denominator; ties follow a fixed ordering rule). Observations with zero or missing denominators (or missing numerators) are treated as missing, and ratios with missingness are discarded, yielding 2356 candidate ratios. Here, and are panel-level missingness cutoffs (including NaNs induced by zero denominators), and we set to retain at least 70% coverage. Robust standardization and Min–Max scaling are applied for numerical stability and unified feature scales in downstream learning.

- Second, Point-Biserial Correlation is used as an effect-size filter (), a moderate-to-strong effect-size cutoff, to prioritize ratios with stronger, economically meaningful label relevance while avoiding overly aggressive pruning of potentially informative, non-traditional ratios. XGBoost then ranks the remaining candidates by Gain to capture nonlinear predictive utility, and RFE-CV is subsequently applied to the XGBoost-ranked candidate set to determine the final subset, fixing as a representation–efficiency trade-off; since , this also permits a lossless reshaping for spatial configuration learning without padding or truncation.

- (2)

- Textual Dynamic Features ()

- First, a hybrid lexicon is constructed by merging the Loughran–McDonald finance categories as a theoretical anchor, localized Chinese finance lexicons from China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS), and an audit red-flag list curated from auditing standards and enforcement cases. Candidate terms are consolidated via de-duplication and synonym/variant unification to obtain a fixed keyword/category inventory. FinBERT-Chinese is further employed for data-driven topic/keyword mining to supplement this inventory; only terms not covered by existing dictionaries and judged economically relevant are retained and added to the final topical keyword list.

- Second, MD&A texts are denoised and standardized to ensure stable feature extraction, including removing non-content artifacts (e.g., HTML/XML markup, embedded tables, and duplicated boilerplate) and normalizing whitespace and full-/half-width characters. To preserve syntactic cues, punctuation is not removed but only standardized in form. Texts are then segmented into sentences based on Chinese sentence-ending punctuation, which supports the computation of style/readability proxies and narrative-focus markers.

3.2.2. Acute Dimension: Characterization of Action

- (1)

- Financial Static Features ()

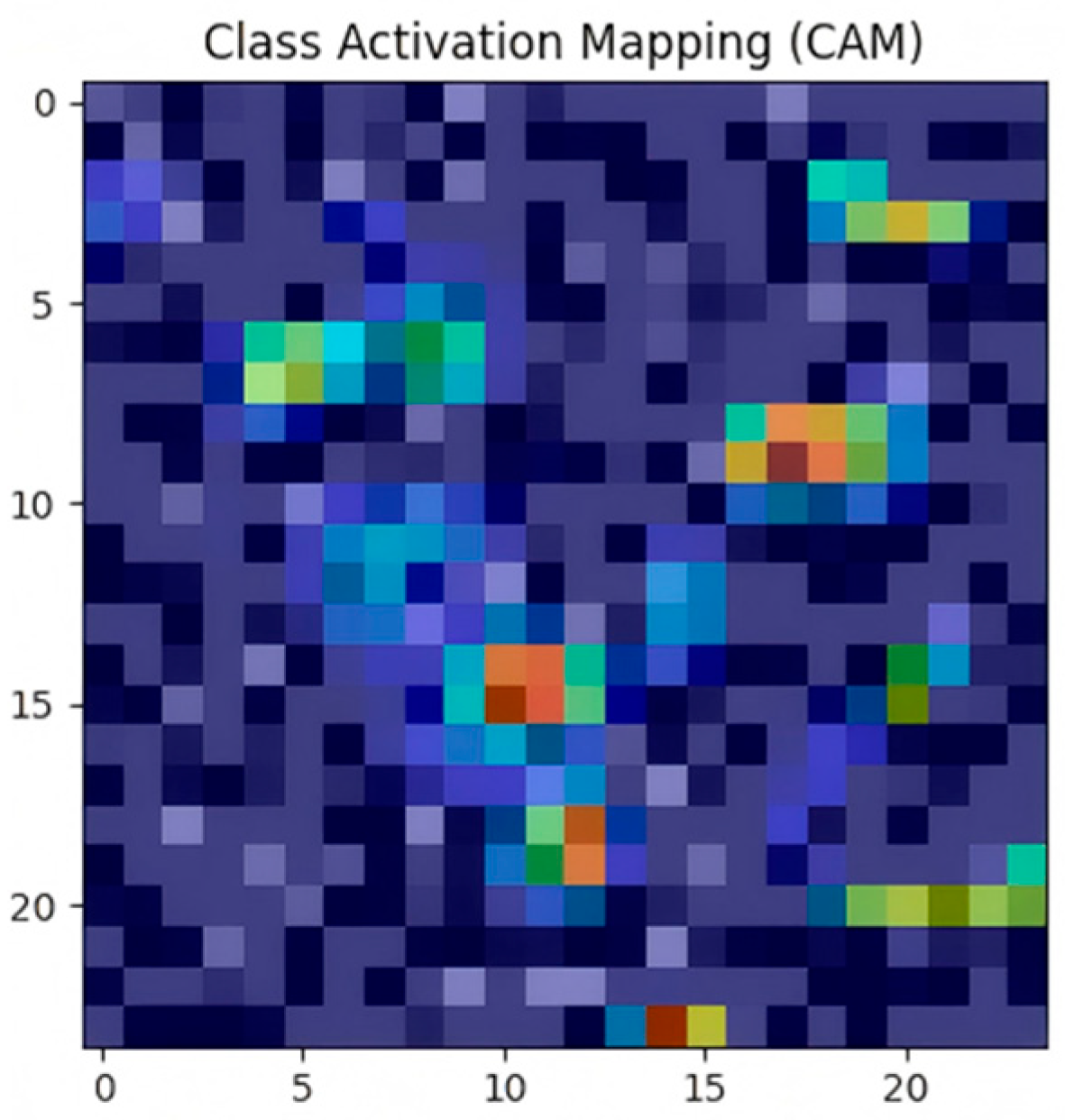

- First, a fixed one-to-one ratio–pixel assignment is learned on the training firm-year panel by computing pairwise Pearson correlations () and minimizing a correlation–distance energy:where is the Euclidean distance on the grid. The minimization is implemented via a Monte-Carlo–style randomized swap search: a random initialization is iteratively refined by swapping two pixels and accepting the swap only if decreases; the search stops when no accepted swap occurs for consecutive proposals (). The resulting layout is then fixed and reused across all firms and years. Thus, each ratio is assigned to a unique and invariant pixel location, i.e., the same ratio always occupies the same pixel across all firms/years and in the test set. Correlations are computed on the training panel using all available pairwise-complete observations for each ratio pair.

- Second, each ratio value is mapped to pixel intensity by:where and are computed from available observations in the training panel; denotes the ratio assigned to pixel ; missing ratios (including NaNs induced by zero denominators) are assigned a neutral gray value . To avoid information leakage, correlation statistics, layout learning, and normalization statistics are fitted on the training split (or within each training fold) and then applied to the held-out test set.

- (2)

- Non-Financial Static Features ()

- First, sixteen non-financial indicators from (such as ownership structure and macro pressure) are imaged and upsampled. They are selected based on pressure theory [32] and information asymmetry theory [33], extracted from three perspectives: macroeconomic environment (external pressure), industry and capital market (competitive pressure), and corporate internal governance (internal opportunity). As shown in Table 3, they aim to capture the structural context in which fraud can occur.

- Second, to obtain a fixed and reproducible mapping, the 16 indicators are arranged into a fixed seed matrix following the Table 3 order, so that indicators from the same perspective occupy adjacent cells. Each indicator is mapped to intensity using training-panel statistics (the same normalization/missing-value rule as in Equation (2)), with missing values assigned a neutral gray level. The seed matrix is then upsampled to by nearest-neighbor replication (each seed cell expanded to a block), which provides sufficient spatial support for convolution without introducing new information.

- (3)

- Textual Static Features ()

- The extraction process of text features for this vector is the same as for .

3.2.3. Operational Alignment Between CTA Constructs and Features

3.3. Overall Architecture Implementation

3.3.1. Motive Identification Module: Chronic Channel

- Financial LSTM Channel (): Input . This channel is specialized in modeling long-range dependencies in financial indicators, such as sustained declines in profitability or gradual increases in the asset-liability ratio.

- Textual LSTM Channel (): Input . This channel focuses on modeling the evolution of managerial narrative strategies. For example, the model can learn a hidden trend of declining readability indices coupled with rising uncertainty frequencies year after year.

3.3.2. Action Identification Module: Acute Channel

- Financial CNN Channel (): Input . Leveraging the local receptive capability of a CNN, this channel captures synergistic anomaly patterns among financial indicators that a flattened vector cannot express, such as a local region where ROE and accounts receivable turnover pixels show extreme brightness simultaneously.

- Non-Financial CNN Channel (): Input . This channel independently analyzes anomalous combinations of structural background features, such as corporate governance and macroeconomic pressure, to provide evidence for the existence of fraud opportunities.

- Textual FNN Channel (): Input . FNN directly learns which specific keywords (such as related-party transaction frequency) or sentiments (such as negative sentiment score) constitute acute fraud warning signals.

3.3.3. Decision Integration Mechanism: Resolving the Identification Paradox

4. Experiments and Results

- (1)

- Empirical existence of the identification paradox: Do single static or single dynamic models exhibit clear performance asymmetry when identifying acute and chronic fraud patterns?

- (2)

- Superiority of the Decoupling-Fusion Identification Paradigm: Does the DF-FraudNet framework proposed in this study achieve statistically significant gains over traditional shallow models, single-paradigm deep models, and alternative naive fusion architectures?

- (3)

- Coherence between theory and decisions: Are the model’s gains grounded in economically interpretable features that align with established theory?

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset and Sample Processing

- Fraud Samples (Positive Class): Strictly defined as company-year observations marked in the CSMAR violation database for one of the seven core financial fraud behaviors (“fictitious profits”, “fictitious assets”, “false records”, “delayed disclosure”, “major omissions”, “untrue disclosures”, and “fraudulent listing”).

- Non-Fraud Samples (Negative Class): To mitigate potential contamination by “False Negatives,” a two-stage cleansing strategy is adopted. First, we remove all ST, *ST, non-standard audit opinions, and cases with non-financial violations to secure the baseline quality of the negative class. Second, we apply a conservative cross-check combining Benford’s law (for numeric manipulation) and Isolation Forest (for high-dimensional structural anomalies) to flag “gray samples” (risk flags, not labels) only when both criteria are met; these flags are used only within each training fold for feature screening and are not removed from training/validation/test evaluation sets.

- Chronic Feature Representation ( to ): a five-year financial sequence and a five-year textual feature sequence .

- Acute Feature Representation (): a grayscale image of financial ratios , a grayscale image of non-financial indicators , and a textual vector .

4.1.2. Experimental Environment and Model Configuration

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.4. Baseline Model Setup

- Purpose: Compare deep representation learning with feature-engineering paradigms.

- Models: Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), XGBoost.

- Purpose: Provide the core empirical test of the identification paradox by contrasting static recognition (CNN) with dynamic recognition (LSTM) and by assessing the standalone predictive value of each modality.

- Models: CNN-Fin (, acute financial images), LSTM-Fin (, chronic financial sequences), FNN-Text (, acute textual vectors), LSTM-Text (, chronic textual sequences).

- Purpose: Test whether the decision-level fusion in this study is structurally superior to naive early fusion and feature-level fusion variants.

- Models: MM-MLP (early fusion, static), MM-LSTM (early fusion, temporal), DF-FraudNet (F) (feature-level fusion variant).

- Purpose: Quantify the performance of our “gray-box” interpretable text features against a “black-box” pretrained language model.

- Model: FinBERT (text only).

4.1.5. Ablation Study Setup

- Variants: w/o Chronic Module (removes the chronic LSTM module); w/o Acute Module (removes the acute CNN-FNN module).

- Variants: w/o Financial Ratios (remove financial ratios); w/o Non-Financial Ratios (remove non-financial ratios); w/o Textual Features (remove textual features).

- Variants: CNN→FNN (replaces CNN with FNN for the acute branch, using flattened vectors), DualCNN→SingleCNN (combines financial and non-financial features into one image), DF-FraudNet () (holds constant at 0.5 during both training and inference).

- Variants: (larger acute convolutional kernels, replacing with in the acute CNNs, with stride 1 and same padding); (wider fusion head); (higher dropout in fusion heads); (smaller chronic hidden sizes). All other settings are unchanged.

- Variant: w/o SMOTE (trained on the original imbalanced training data, with all other settings unchanged).

4.2. Results and Analysis

4.2.1. Empirical Test of the Identification Paradox: Asymmetry Across Paradigms

4.2.2. Overall Performance Comparison: Superiority of DF-FraudNet

4.2.3. Ablation Study: Contribution of Internal Components

4.2.4. XAI Analysis: Decision Logic and Theoretical Coherence

4.2.5. Experimental Conclusion and Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Managerial Implications

5.2.3. Ethical Risks and Regulatory Implications

5.3. Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, F.; Lin, D.; Hu, L.; He, S.; Cao, Z. The Spillover Effect of Corporate Frauds and Stock Price Crash Risk. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Neu, K.; Rahaman, A.S.; Saxton, G.D.; Neu, D. Tone at the Top, Corporate Irresponsibility and the Enron Emails. Accounting Audit. Account. J. 2024, 37, 336–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, R. The Luckin Coffee Scandal and Short Selling Attacks. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2022, 34, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achakzai, M.A.K.; Juan, P. Detecting financial statement fraud using dynamic ensemble machine learning. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 89, 1057–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daoud, K.I.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A. Robust AI for Financial Fraud Detection in the GCC: A Hybrid Framework for Imbalance, Drift, and Adversarial Threats. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forough, J.; Momtazi, S. Ensemble of deep sequential models for credit card fraud detection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 99, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, G.; Yan, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, M. Time-aware attention-based gated network for credit card fraud detection by extracting transactional behaviors. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P.; Abedin, M.Z.; Sivarajah, U. Fraud Detection in Mobile Payment Systems using an XGBoost-based Framework. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 1985–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, T. Bankruptcy prediction using imaged financial ratios and convolutional neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 117, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D.R. Other People’s Money: A Study in the Social Psychology of Embezzlement; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.C.W.; Yuan, H. Earnings Management and Capital Resource Allocation: Evidence from China’s Accounting-Based Regulation of Rights Issues. Contemp. Account. Res. 2004, 21, 557–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierstaker, J.; Brink, W.D.; Khatoon, S.; Thorne, L. Academic Fraud and Remote Evaluation of Accounting Students: An Application of the Fraud Triangle. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 195, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D.M.; DeZoort, F.T.; Hermanson, D.R. The effect of alternative fraud model use on auditors’ fraud risk judgments. J. Account. Public Policy 2015, 34, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.E.; Rezaee, Z.; Riley, R.A.; Velury, U.K. Financial statement fraud: Insights from the academic literature. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2008, 27, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpoff, J.M.; Lee, D.S.; Martin, G.S. The Cost to Firms of Cooking the Books. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2008, 43, 581–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneish, M.D. The Detection of Earnings Manipulation. Financ. Anal. J. 1999, 55, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rtayli, N.; Enneya, N. Enhanced credit card fraud detection based on SVM-recursive feature elimination and hyper-parameters optimization. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2020, 55, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Cao, X.; Pu, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Khan, A.T.; Francis, A.; Li, S. Fraud detection in capital markets: A novel machine learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 231, 120760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Wang, K. Efficient fraud detection using deep boosting decision trees. Decis. Support Syst. 2023, 175, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, F.; Chen, T.; Pan, L.; Beliakov, G.; Wu, J. A Brief Survey of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for E-Commerce Research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 2188–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, W.; Gadsden, S.A.; Yawney, J. Financial Fraud: A Review of Anomaly Detection Techniques and Recent Advances. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 193, 116429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Annual Report Readability, Current Earnings, and Earnings Persistence. J. Account. Econ. 2008, 45, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T.; McDonald, B. When Is a Liability Not a Liability? Textual Analysis, Dictionaries, and 10-Ks. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Mickovic, A. Accounting Fraud Detection Using Contextual Language Learning. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2024, 53, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.-P. Multimodal Machine Learning: A Survey and Taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craja, P.; Kim, A.; Lessmann, S. Deep learning for detecting financial statement fraud. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 139, 113421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Padliansyah, R.; Lu, Y.-H.; Liu, W.-R. Bankruptcy prediction: Integration of convolutional neural networks and explainable artificial intelligence techniques. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2025, 56, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravisankar, P.; Ravi, V.; Rao, G.R.; Bose, I. Detection of financial statement fraud and feature selection using data mining techniques. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 1969, 37, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Friedman, N. Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Net profit/Shareholders’ equity | Inventories/Cost of goods sold |

| Current assets/Current liabilities | Sales revenue/Total assets |

| Total liabilities/Operating costs | Net profit/Total assets |

| Operating cash flow/Net profit | Operating profit/Non-operating expenses |

| Total assets/Shareholders’ equity | Total liabilities/Total assets |

| Operating cash flow/Current liabilities | Net fixed assets/Construction in progress (net) |

| Net profit/Sales revenue | Long-term liabilities/Shareholders’ equity |

| Operating profit/Non-operating income | Sales revenue/Average accounts receivable |

| Other receivables/Total assets | Net cash flow from operating activities/Operating revenue |

| Operating revenue/Inventories | Operating profit/Interest expense |

| Category | Feature Name | Category | Feature Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sentiment & Tone (5) | Negative sentiment frequency | Core topical keywords (29) | “performance commitment” term frequency |

| Positive sentiment frequency | “non-standard audit opinion” term frequency | ||

| Uncertainty term frequency | “qualified audit opinion” term frequency | ||

| Litigation term frequency | “asset impairment” term frequency | ||

| Sentiment balance (Pos-Neg) | “goodwill impairment” term frequency | ||

| Core topical keywords (29) | “risk” term frequency | “provision for bad debts” term frequency | |

| “uncertainty” term frequency | “inventory write-down” term frequency | ||

| “liabilities” term frequency | “revenue recognition” term frequency | ||

| “restructuring” term frequency | “financial restructuring” term frequency | ||

| “risk exposure” term frequency | Linguistic style & readability (5) | Text readability index | |

| “decline” term frequency | Text length | ||

| “recession” term frequency | Average sentence length | ||

| “accounting” term frequency | Numeral ratio | ||

| “transparency” term frequency | Hedging/Modal term frequency | ||

| “integrity” term frequency | Temporal focus & narrative (10) | Past tense frequency | |

| “compliance” term frequency | Future tense—planning frequency | ||

| “disclosure” term frequency | Future tense—forecasting frequency | ||

| “audit” term frequency | Future tense—outlook frequency | ||

| “governance” term frequency | Temporal focus balance | ||

| “board of directors” term frequency | Internal attribution frequency | ||

| “management turnover” term frequency | External—macro frequency | ||

| “related-party transactions” term frequency | External—policy/industry frequency | ||

| “related parties” term frequency | External—market frequency | ||

| “guarantees” term frequency | Attribution balance | ||

| “pledge” term frequency |

| Category | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Macroeconomic environment | Unemployment rate = number of unemployed/labor force |

| GDP growth rate = (current GDP − previous GDP)/previous GDP | |

| Tax revenue growth rate = (current tax revenue − previous tax revenue)/previous tax revenue | |

| Interest rate level = interest paid/principal | |

| Growth rate of fraud-penalty amount = (current fraud-penalty amount − previous fraud-penalty amount)/previous fraud-penalty amount | |

| Corporate governance structure | Independent-director ratio = number of independent directors/total number of board members |

| Largest-shareholder ownership ratio = shares held by the largest shareholder/total shares outstanding | |

| Management ownership ratio = shares held by management/total shares outstanding | |

| Board-size ratio = number of board members/total employees | |

| Executive compensation to net profit ratio = total executive compensation/net profit | |

| Shareholding concentration = total shares held by top 10 shareholders/total shares outstanding | |

| Employee turnover rate = number of departing employees/total employees | |

| Industry & capital market | Industry concentration ratio = market share of top firms/total industry market share |

| Deviation between actual performance and market expectations = (actual performance − market expectations)/market expectations | |

| Stock-price volatility = standard deviation of daily closing-price changes/average stock price | |

| Deviation from industry-average financial indicator = (firm’s financial ratio − industry average financial ratio)/industry average financial ratio |

| Module | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Missingness filtering | (line-item), (ratio); |

| Preprocessing | RobustScaler (median/IQR) + MinMaxScaler |

| Point-biserial | Point-biserial effect-size filter: |

| XGBoost | gbtree; , , , , , , , ; ; |

| RFE-CV | ; 5-fold CV; ; |

| Module | Component | Core Architecture/Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Module | ||

| Chronic Module | ||

| Decision Fusion |

| Category | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Objective & imbalance | Binary classification; BCEWithLogitsLoss. SMOTE (train only). |

| Optimization & schedule | AdamW, lr , weight decay ; ReduceLROnPlateau (monitor: val AUPRC; factor 0.5; patience 3; min lr ). The fusion weight is optimized end-to-end jointly with all trainable parameters. |

| Training protocol & regularization | Batch size 256; max epochs 80; early stopping on val AUPRC (patience 10), restoring best checkpoint. Dropout (Table 5); L2 regularization via weight decay (); gradient clipping (max norm 1.0). |

| Computational cost & resources | Single-GPU training on RTX 4060 Ti (16 GB) (Windows 11; PyTorch 2.2.1); no distributed training. Typical wall-clock runtime under early stopping is min/fold ( min for 5-fold CV), and inference latency is ms/sample (batch dependent). |

| Category | Model | Accuracy (μ ± σ) | Precision (μ ± σ) | Recall (μ ± σ) | F1 Score (μ ± σ) | AUC (μ ± σ; 95% CI) | AUPRC (μ ± σ; 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | LR | 0.870 ± 0.0052 | 0.800 ± 0.0143 | 0.690 ± 0.0161 | 0.741 ± 0.0124 | 0.880 ± 0.0082 [0.870, 0.890] | 0.564 ± 0.0314 [0.525, 0.603] |

| RF | 0.889 ± 0.0041 | 0.835 ± 0.0127 | 0.725 ± 0.0142 | 0.776 ± 0.0109 | 0.905 ± 0.0064 [0.897, 0.913] | 0.635 ± 0.0261 [0.603, 0.667] | |

| XGBoost | 0.904 ± 0.0034 | 0.855 ± 0.0115 | 0.765 ± 0.0131 | 0.807 ± 0.0102 | 0.921 ± 0.0051 [0.915, 0.927] | 0.684 ± 0.0227 [0.656, 0.712] | |

| Group 2 | CNN-Fin | 0.898 ± 0.0040 | 0.845 ± 0.0123 | 0.748 ± 0.0134 | 0.794 ± 0.0101 | 0.914 ± 0.0062 [0.906, 0.922] | 0.662 ± 0.0274 [0.628, 0.696] |

| LSTM-Fin | 0.921 ± 0.0031 | 0.880 ± 0.0110 | 0.820 ± 0.0120 | 0.849 ± 0.0092 | 0.938 ± 0.0049 [0.932, 0.944] | 0.740 ± 0.0206 [0.714, 0.766] | |

| FNN-Text | 0.854 ± 0.0062 | 0.775 ± 0.0174 | 0.645 ± 0.0193 | 0.704 ± 0.0151 | 0.862 ± 0.0103 [0.849, 0.875] | 0.518 ± 0.0422 [0.466, 0.570] | |

| LSTM-Text | 0.865 ± 0.0055 | 0.792 ± 0.0162 | 0.670 ± 0.0184 | 0.726 ± 0.0140 | 0.878 ± 0.0091 [0.867, 0.889] | 0.559 ± 0.0387 [0.511, 0.607] | |

| Group 3 | MM-MLP | 0.918 ± 0.0030 | 0.876 ± 0.0104 | 0.810 ± 0.0114 | 0.842 ± 0.0090 | 0.935 ± 0.0058 [0.928, 0.942] | 0.730 ± 0.0212 [0.704, 0.756] |

| MM-LSTM | 0.932 ± 0.0027 | 0.895 ± 0.0101 | 0.840 ± 0.0110 | 0.867 ± 0.0085 | 0.948 ± 0.0048 [0.942, 0.954] | 0.775 ± 0.0190 [0.751, 0.799] | |

| DF-Fraud Net (F) | 0.948 ± 0.0023 | 0.914 ± 0.0083 | 0.900 ± 0.0092 | 0.907 ± 0.0072 | 0.962 ± 0.0038 [0.957, 0.967] | 0.827 ± 0.0156 [0.808, 0.846] | |

| Group 4 | FinBERT | 0.901 ± 0.0044 | 0.852 ± 0.0136 | 0.760 ± 0.0151 | 0.803 ± 0.0120 | 0.915 ± 0.0081 [0.905, 0.925] | 0.665 ± 0.0293 [0.629, 0.701] |

| Proposed model | DF-FraudNet | 0.956 ± 0.0024 | 0.927 ± 0.0076 | 0.935 ± 0.0083 | 0.931 ± 0.0064 | 0.967 ± 0.0037 [0.962, 0.972] | 0.847 ± 0.0148 [0.829, 0.865] |

| Model Paradigm | Acute Fraud Identification | Chronic Fraud Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Action Identification Module (CNN-Fin) | 0.928 [0.915, 0.940] | 0.905 [0.889, 0.919] |

| Motive Identification Module (LSTM-Fin) | 0.902 [0.885, 0.916] | 0.952 [0.944, 0.959] |

| Category | Variant | Accuracy (μ ± σ) | F1 Score (μ ± σ) | AUPRC (μ ± σ; 95% CI) | AUC (μ ± σ; 95% CI) | ΔAUC | p_Holm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | w/o Chronic module | 0.940 ± 0.0041 | 0.905 ± 0.0110 | 0.778 ± 0.0330 [0.737, 0.819] | 0.949 ± 0.0080 [0.939, 0.959] | −0.018 | 0.0209 | −3.25 |

| w/o Acute module | 0.949 ± 0.0036 | 0.920 ± 0.0100 | 0.800 ± 0.0300 [0.763, 0.837] | 0.955 ± 0.0070 [0.946, 0.964] | −0.012 | 0.0468 | −2.55 | |

| Group B | w/o Financial ratios | 0.913 ± 0.0068 | 0.857 ± 0.0170 | 0.656 ± 0.0450 [0.600, 0.712] | 0.912 ± 0.0120 [0.897, 0.927] | −0.055 | 0.0021 | −6.00 |

| w/o Non-financial ratios | 0.952 ± 0.0037 | 0.926 ± 0.0100 | 0.804 ± 0.0280 [0.769, 0.839] | 0.956 ± 0.0070 [0.947, 0.965] | −0.011 | 0.0688 | −2.15 | |

| w/o Text features | 0.948 ± 0.0042 | 0.919 ± 0.0110 | 0.812 ± 0.0320 [0.772, 0.852] | 0.958 ± 0.0080 [0.948, 0.968] | −0.009 | 0.0844 | −1.95 | |

| Group C | CNN→FNN | 0.946 ± 0.0040 | 0.914 ± 0.0110 | 0.800 ± 0.0310 [0.762, 0.839] | 0.955 ± 0.0070 [0.946, 0.964] | −0.012 | 0.0565 | −2.35 |

| DualCNN→SingleCNN | 0.949 ± 0.0038 | 0.918 ± 0.0100 | 0.815 ± 0.0290 [0.779, 0.851] | 0.959 ± 0.0070 [0.950, 0.968] | −0.008 | 0.1041 | −1.75 | |

| DF-FraudNet () | 0.953 ± 0.0030 | 0.927 ± 0.0090 | 0.831 ± 0.0250 [0.800, 0.862] | 0.963 ± 0.0060 [0.956, 0.970] | −0.004 | 0.3323 | −1.12 | |

| Group D | 0.955 ± 0.0028 | 0.930 ± 0.0080 | 0.842 ± 0.0210 [0.816, 0.868] | 0.965 ± 0.0050 [0.959, 0.971] | −0.002 | 0.4034 | −0.85 | |

| 0.956 ± 0.0024 | 0.931 ± 0.0080 | 0.848 ± 0.0190 [0.824, 0.872] | 0.967 ± 0.0050 [0.961, 0.973] | +0.000 | 1.0000 | +0.00 | ||

| 0.955 ± 0.0030 | 0.930 ± 0.0090 | 0.841 ± 0.0220 [0.814, 0.868] | 0.965 ± 0.0050 [0.959, 0.971] | −0.002 | 0.4034 | −0.75 | ||

| 0.954 ± 0.0032 | 0.928 ± 0.0090 | 0.838 ± 0.0240 [0.808, 0.868] | 0.964 ± 0.0060 [0.957, 0.971] | −0.003 | 0.4034 | −0.95 | ||

| Proposed model | DF-FraudNet | 0.956 ± 0.0024 | 0.931 ± 0.0064 | 0.847 ± 0.0148 [0.829, 0.865] | 0.967 ± 0.0037 [0.962, 0.972] | - | - | - |

| Category | Variant | Accuracy [95% CI] | Precision [95% CI] | Recall [95% CI] | F1 Score [95% CI] | AUC [95% CI] | AUPRC [95% CI] | FPR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group E | w/o SMOTE | 0.958 [0.956, 0.961] | 0.950 [0.943, 0.957] | 0.860 [0.849, 0.869] | 0.903 [0.894, 0.910] | 0.963 [0.958, 0.966] | 0.800 [0.784, 0.812] | 0.0057 [0.0048, 0.0066] |

| Proposed model | DF-FraudNet | 0.956 [0.953, 0.958] | 0.927 [0.920, 0.934] | 0.935 [0.927, 0.943] | 0.931 [0.925, 0.937] | 0.967 [0.962, 0.971] | 0.847 [0.833, 0.862] | 0.0092 [0.0080, 0.0106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Qin, Z.; Dong, J.; Li, S. A Decoupling-Fusion System for Financial Fraud Detection: Operationalizing Causal–Temporal Asynchrony in Multimodal Data. Systems 2026, 14, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010025

Li W, Liu X, Li Z, Qin Z, Dong J, Li S. A Decoupling-Fusion System for Financial Fraud Detection: Operationalizing Causal–Temporal Asynchrony in Multimodal Data. Systems. 2026; 14(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenjuan, Xinghua Liu, Ziyi Li, Zulei Qin, Jinxian Dong, and Shugang Li. 2026. "A Decoupling-Fusion System for Financial Fraud Detection: Operationalizing Causal–Temporal Asynchrony in Multimodal Data" Systems 14, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010025

APA StyleLi, W., Liu, X., Li, Z., Qin, Z., Dong, J., & Li, S. (2026). A Decoupling-Fusion System for Financial Fraud Detection: Operationalizing Causal–Temporal Asynchrony in Multimodal Data. Systems, 14(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010025