1. Introduction

Since the last century, Systems Engineering (SE) approaches have been developed based on Systems Theory for the systematic development of complex solutions [

1]. SE comprises ways of thinking, and processes and methods for analysing problems and considering the demands of various stakeholders. It supports informed and traceable decision-making and the holistic development and evaluation of technical solutions, including the incorporation of known reference systems [

2]. In addition to processes and methods, Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) approaches have also been investigated for several years using targeted digital models to support specific tasks during development [

3]. The digital models range from semi-formal models in the early development phases to formal models for detailed specifications and analyses [

4,

5]. The models should be built according to systemic concepts. Explanations on these systemic concepts can be found, for example, in [

6,

7]. A systematic approach and targeted modelling are particularly important for civil engineering systems, such as bridges and buildings, which must be regularly assessed and maintained over long periods of time in changing conditions.

A reassessment of structural capacity is necessary to ensure the safety and sustainability of the ageing infrastructure. Conventional structural reassessment methods include deterministic design checks, visual inspections, and Finite Element (FE) simulations [

8]. These methods, while useful, often lack the ability to incorporate real-time condition data and account for evolving damage states. A large number of existing structures, such as bridges, buildings, and offshore platforms, were constructed following old codes and design practices, whose assumptions may have been invalidated due to ageing, traffic increase, environmental changes, etc. [

9]. The capacity estimation of the current infrastructure is uncertain because of several influences, such as degradation, material variability, and model assumptions [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Reliability analysis has long served as a framework for decision-making in this context [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

In line with the developments towards the ‘intelligent bridge’ [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], many engineering structures will, in future, be equipped with networked real-time monitoring systems more comprehensively than before. An engineering structure and sensor system form a unit as a so-called ‘intelligent structure’, which independently analyses the collected data and converts it into information about the existing system states. Digital Twins leverage this data to update numerical models and simulate structural behaviour under varying conditions [

24]. The integrated use of Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) in structural models allows for an understanding of actual in-service behaviour and enables updates to model parameters, such as stiffness and capacity, based on observed conditions. In this context, the structural model refers to the numerical or analytical representation of the structure, whereas the design model refers to the code-based framework (e.g., Eurocode) that defines the verification format and target safety levels used to determine design points. By processing SHM data through a model-updating scheme, e.g., Bayesian inference, the reassessment can move from assumption-based safety to observation-informed reliability.

Bayesian inference has emerged as a key method for updating structural state estimation using SHM data [

25]. By continuously incorporating sensor measurements, Bayesian updating enables the refinement of model parameters and reduces uncertainty in structural predictions. Several studies have demonstrated improved predictive accuracy in fatigue damage prognosis [

26] and structural reliability updating [

27]. Based on this foundation, a novel approach has been proposed to reassess structural capacity reserves by re-examining the partial safety factor related to model uncertainty, using SHM-integrated model updating schemes [

28,

29,

30].

A major challenge in structural reassessment and the subsequent compliance with specifications from, for example, the Eurocode, is that the process requires several models (e.g., update model, structural model, and design model) with different instances of the parameters. Therefore, a formalised MBSE perspective can be beneficial for the effective integration of multidisciplinary models and decision-making processes in Digital Twin frameworks. Some approaches for the systematic development of Digital Twins using MBSE are known in different fields [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. In this contribution, MBSE is intended to become an integral part of the Digital Twin and should support decision-making in structural reassessment. While prior research has demonstrated the benefits of SHM, Bayesian inference, and Digital Twin technologies, the incorporation of MBSE into structural reassessment can enable a more holistic and systematic investigation. Within the scope of this study, it is examined how MBSE approaches can support the planning and organisation of reassessing structural capacities through the integration of SHM data. The proposed MBSE-SHM integration provides a scalable, adaptive, and data-driven approach for structural reassessment, which can ultimately contribute to enhancing the reliability, maintainability, and sustainability of critical infrastructure.

The objective of this contribution is to examine the support for SHM and Bayesian updating through MBSE and to discuss initial concepts for integration. The concept is realised as a prototype and discussed using a concrete example from civil engineering. The summary explains the need for further research.

2. Fundamentals and State of the Art

2.1. Reassessment in the Context of Calibration of Design Values

Reliability is a basic performance requirement in the design assessment of any structural system. It indicates the capacity of a structure to perform its intended function under design conditions throughout its service life. Structural reliability is based on the interaction between the intrinsic resistance of the structure and material, and the effects of actions brought upon the structure. These interactions have traditionally been modelled stochastically and account for the uncertainties, both in resistance and in loading. A basic requirement of design is that the resistances of a system should purposely outweigh the effect of actions, to a limit such that the probability of failure remains below an accepted threshold [

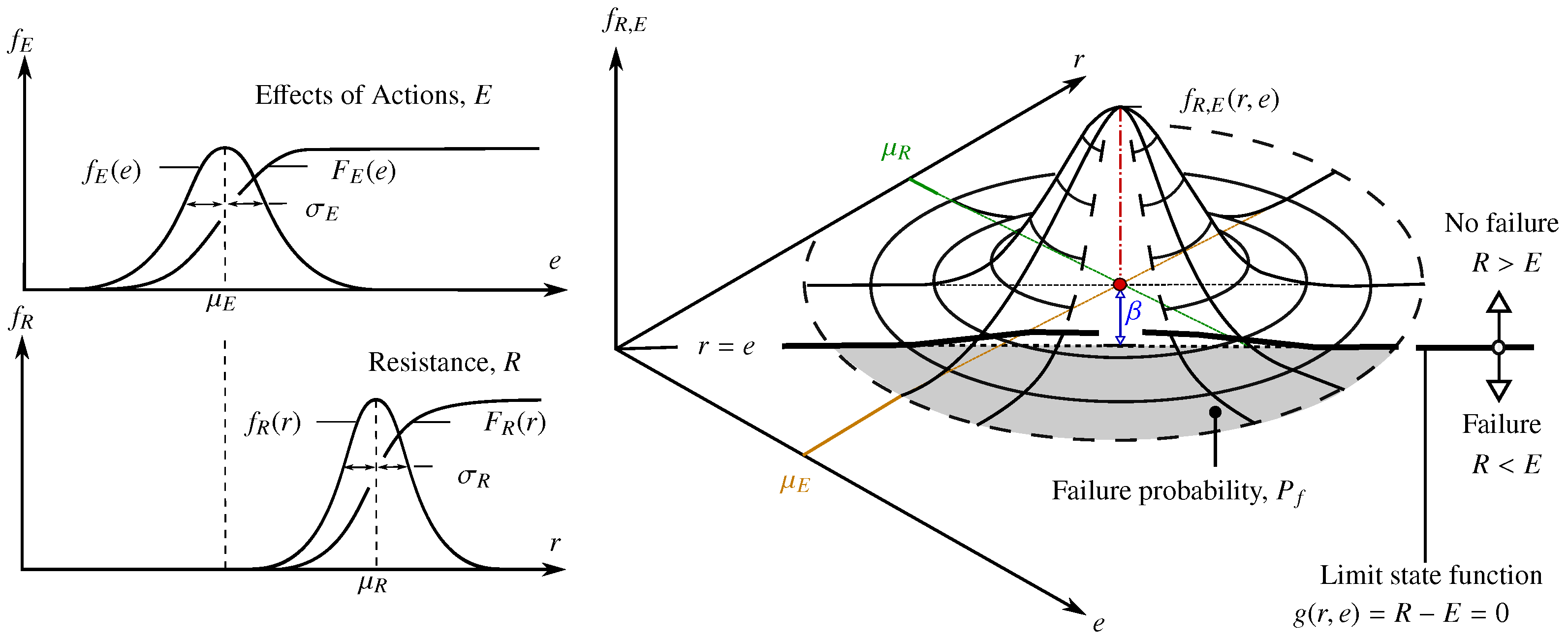

37]. This relationship has been traditionally explained through a limit state function:

where

R is the structural resistance as a function of material or system parameters, and

E is the effect of applied actions. Both

R and

E are considered random variables, generally represented with probability distributions and the statistical parameters

and

, respectively.

Figure 1 visualises both the marginal and joint probability densities of

R and

E [

28,

29,

38]. The joint probability distribution is defined as

In this study,

R and

E are assumed to be statistically independent, which is a common assumption in structural reliability analysis, as load effects and resistances typically arise from distinct physical sources. The failure domain is identified as the region where

, and the corresponding failure probability

is calculated as the integral over this domain, which serves as a quantitative measure of structural safety. To facilitate probabilistic assessment, the system model is often transformed into standard normal space. Within this space, the shortest distance from the origin to the limit state surface

defines the reliability index

. This index serves as the basis for structural reliability, the failure probability being related to it by

where

is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. The reliability index is supported by the sensitivity factors

and

, which describe how the uncertainty on the resistance and the action affect the system reliability. The associated design point values are given by

This reliability formulation provides the fundamental framework for quantifying structural performance under uncertainty. While the detailed derivation and the role of sensitivity factors (

) are well established in the literature, only the key definitions are retained here to maintain focus on the integration of reliability assessment within the broader MBSE framework.

2.2. Structural Health Monitoring, Digital Twin, and Model Updating

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) and Digital Twin technologies play a key role in reassessing ageing structures as they allow real-time data to be fed into a model. SHM involves the process of monitoring long-term structural change, as measured by changes in strain, displacement, velocity, or acceleration, using an array of suitably distributed sensors. These data assist in reasoning about the in-service performance of the structure and therefore form an essential basis for model updating. The concept of SHM is further extended with the introduction of a Digital Twin, which essentially depicts the physical structure in the virtual model as it becomes updated with the arrival of new data. The model represents the as-is of the system and is used to dynamically forecast, simulate, and act. For structural reassessment, the Digital Twin serves as a live counterpart of the structural assets that integrate data from monitoring systems and provide feedback to the revised performance or reliability models [

39,

40].

One of the central applications of the Digital Twin is model updating, a method whereby the computational replica of the structure is adjusted to actual behaviour. This is particularly important when parameters of stiffness, damage, or degradation are uncertain or time-dependent. Model updating frameworks generally consider the (unknown) parameters of interest, which are denoted hereafter as

, being uncertain and updatable from measured data

d such as the strain field value at different sensors. Bayesian updating is one structured approach to combine knowledge of parameters with new sensor data (among many others). Based on Bayes’ theorem [

25,

41,

42], the posterior probability distribution of parameter vector

given the observations

d is expressed as

, where

is the prior distribution representing the state of knowledge (or belief) before an analysis,

is the likelihood function, and

is the posterior distribution, representing the knowledge (belief) about the parameters after integrating data. The updated distribution, known as the posterior distribution, is a function representing the improved knowledge about the condition of the system. Here, the estimation error is regarded as a sum of model and measurement imprecision, usually assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution. Although the form of the mathematical solution may depend on the structural model and configuration of sensors, the posterior distribution represents the system information with a statistically consistent approach.

Crucially, the model updating is not restricted to the framework of Bayesian inference. Other approaches, such as Kalman filtering [

43,

44], system identification [

45,

46], and data assimilation methods [

47], can also be employed depending on the model complexity, sensor resolution, and available computational resources. Whether implemented directly or indirectly, the objective of these techniques is to modify system parameters and model states such that the virtual representation of the structure more closely approximates its physical counterpart.

2.3. Application of Reassessing Structural Capacity Incorporating SHM

The general principles of reassessing structural integrity using SHM information were outlined in earlier work by Chowdhury and Kraus [

28,

29,

30]. Following the proposed development, let us recall the structural system—a rail bridge—whose strain response is monitored at selected sensor locations. Uncertainties in the geometric and material properties are modelled in the form of random variables characterised by statistical distributions. Simulated samples of these parameters are used to calculate the variability of the bending stiffness

as a relevant property. The resulting distribution of

is estimated using model selection criteria such as AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) to select the best-fitting probability distribution among several candidates and define the prior distribution

for Bayesian updating. The strain data obtained from the structural model was synthesised with noise and served as the measurement response of a structure in service. This data takes on the role of probability in the Bayesian formulation, which was used to estimate the updated stiffness values according to the observed responses. Details on Bayesian model updating in the context of this application can be found in [

28,

29,

30].

The effectiveness of the updating process is influenced by the configuration of the measurement system. Both the number of sensors and their spatial distribution play a decisive role in how well the structural condition can be derived. A sparse arrangement of sensors can lead to incomplete or distorted estimates, while denser configurations generally improve accuracy; however, at a higher cost and with greater complexity. In addition, the level of inherent noise in the sensor signals significantly affects the reliability of the measured response. Higher noise levels can obscure the actual structural behaviour and lead to incorrect conclusions if not properly accounted for. To address this issue, measurement uncertainties are explicitly modelled, enabling sensitivity analyses for different sensor arrangements and noise intensities. This provides insights into how the monitoring configuration affects the accuracy of parameter updates and supports the determination of minimum sensor requirements for reliable assessment. Ultimately, understanding these influences helps guide the development of efficient and effective SHM systems tailored to the requirements of decision-making under uncertainty.

A conceptually simplified flowchart, shown in

Figure 2, summarises the most important aspects of the process. In the first block of the

Structural Model, the structure is modelled (numerical/analytical) with its nominal design characteristics, the resistance (R) is defined according to the design (e.g., yield strength of material), and the effects of the action (E) are estimated based on the probable action scenario. The structure is then instrumented with various sensor layouts in the

Measuring System Model such that the measurements can be obtained under operating conditions. The measurement data is transferred to the

Update Model, where a mathematical model updating (e.g., Bayesian inference) can be used to reassess the bending stiffness in order to estimate the actual or as-is behaviour of the structure. In the following

Design Model block, the updated structural condition is evaluated using a semi-probabilistic framework with reassessed reliability index

, which supports refined decision-making regarding structural performance and safety. This integrated methodology provides a systematic approach to reducing epistemic uncertainty and improving confidence in structural assessment by combining model-based design with measurement-based updates.

2.4. Describing Systems Based on Characteristics and Properties

For the classification of the different parameters of the structures (e.g., for describing the geometry, materials, and resistance) used for reassessment and SHM (see

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2), a structured approach for describing technical systems using systemic concepts should be used.

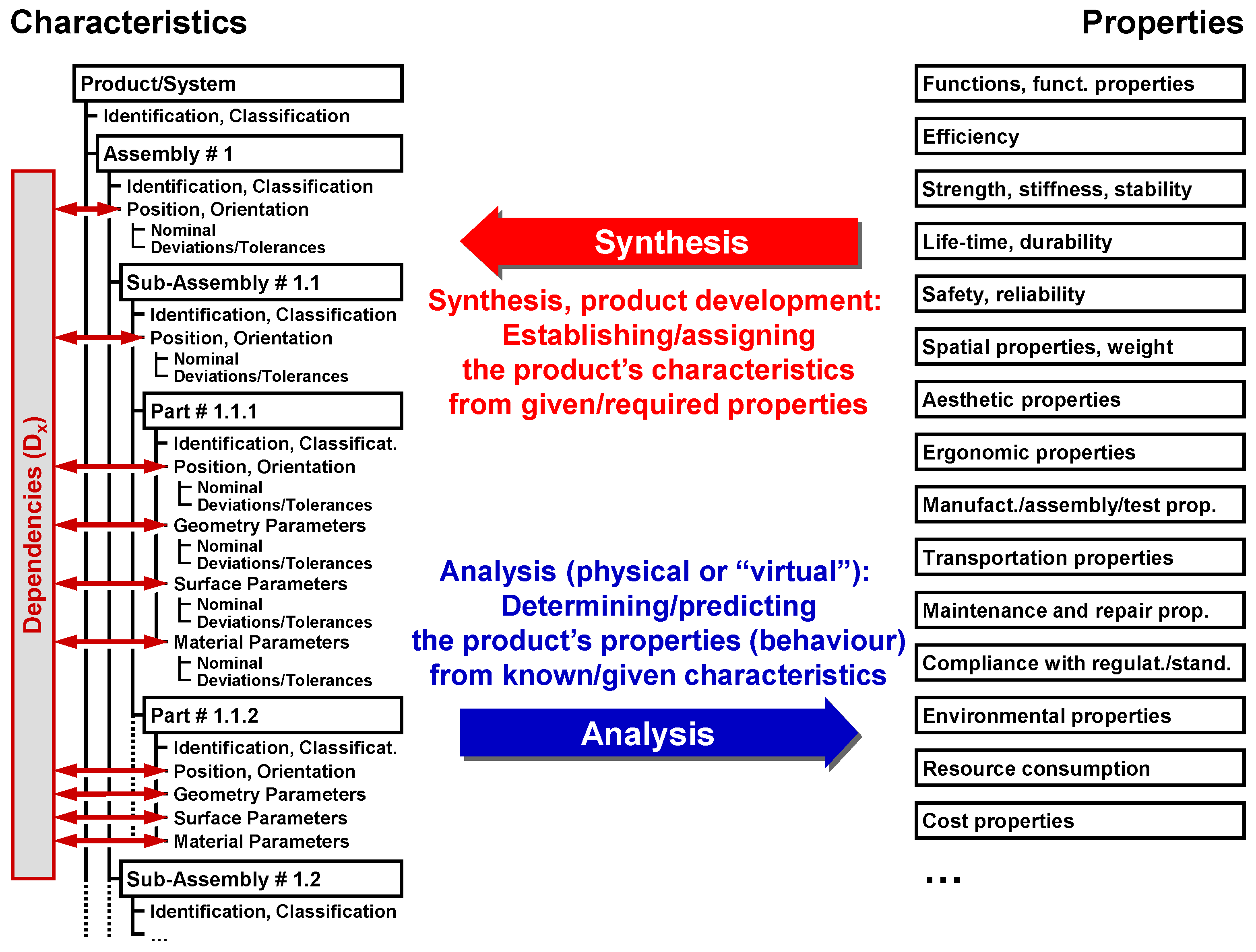

Weber has introduced the so-called CPM (Characteristics–Properties modelling) approach as the basis for the systematic description of technical systems [

48] (see also

Figure 3). The CPM approach is based on the preliminary work of various authors [

49,

50,

51]. This approach describes technical systems in terms of

characteristics (

) that can be directly influenced during development and

properties (

). On the one hand, properties describe the stakeholders’ requirements (e.g., the necessary loading capacity of a bridge or its service life) as required properties and on the other hand, the properties that are actually realised on the basis of the characteristics and external influences as as-is properties. Every system has to fulfil numerous properties, some of which may be in conflict with each other (costs vs. service life, etc.). As a result, many compromises have to be made during development.

For the effective management of civil infrastructure systems, it is significant to evaluate existing structural capacity for operational and environmental uncertainties. This problem can be effectively conceptualised from a systemic design perspective using the CPM approach, where

characteristics (

) refer to the physical and design-defining parameters of the civil infrastructure, such as geometry, material, and boundary conditions that parametrise the structure and that can be updated against inspection or monitoring data. The

properties (

) signify structural behaviours—such as strain or displacement response. External conditions (

) (these are not shown in

Figure 3) describe factors such as load collectives or environmental exposure.

The CPM approach is complemented by the PDD (Property-Driven Development) approach, which describes development as an iterative process of synthesis and analysis between the required as well as as-is properties and the characteristics [

48].

The relationships in the CPM approach are mathematically formalised in the reassessment framework through the inclusion of measured performance outcomes and prior structural models. Measurement data , collected from different sensor configurations (), are used to characterise uncertain structural properties, such as strain or displacement amplitudes. These properties are represented as amended attributes and are linked to characteristics through structural mechanics or empirical models. Based on uncertain model parameters, a prior distribution can be established over quantities such as material degradation rates or stiffness reductions. This prior is updated by the likelihood , resulting in the posterior distribution through Bayes’ theorem. This iterative inference process reflects the PDD aspect, where differences in observed properties are exploited to iteratively refine inferences about internal structural characteristics. Within the Bayesian framework, sensor data from multiple configurations () are explicitly incorporated by modelling the uncertainty in measurements . The noise and error propagation from sensors is captured within the likelihood function . This noise can either be assumed to follow known distributions (e.g., Gaussian, uniform) or be derived from prior calibration data for the specific sensor types. In cases involving heterogeneous sensor types or configurations, the noise model is adapted to account for differences in measurement precision, accuracy, and resolution.

The proposed reassessment strongly depends on the number of sensors () and their arrangement in the structural system. Although more sensors generally provide more data points, and all contribute to shaping the posterior distribution of structural properties, there remains a trade-off due to redundancy and correlations in the data. Sensors must be strategically located to yield the most informative data about the structure—specifically in areas most likely to experience significant stress. From the CPM/PDD perspective, sensors enable the determination of as-is properties () and based on this, a refinement of characteristics () associated with properties (), thereby enriching the knowledge base in a way that is meaningful for both analysis and synthesis operations.

Furthermore, determining whether the structural performance satisfies code-suggested reliability targets can be framed as an inference process. In this approach, the updated properties are evaluated through the posterior distribution of system parameters and compared against threshold values () to be met. If deviations are identified, revised characteristic values or appropriate measures (e.g., retrofitting) can be recommended. This cyclic synthesis–analysis loop, where uncertainty propagates from characteristics to properties bidirectionally, positions the CPM/PDD framework as a beneficial principle for structural reassessment under reliability constraints. The Bayesian updating framework, in conjunction with the CPM/PDD model, provides a robust mechanism for incorporating these uncertainties into the decision-making process, ensuring that the structural capacity is reassessed with the most accurate and reliable information available.

2.5. MBSE for Structural Reassessment

SE approaches support the development of complex systems by providing a structured framework of processes and methods, as well as encouraging systemic thinking that supports both holistic and specific perspectives [

1,

53]. MBSE is the targeted extension of SE through the use of task-specific models. Examples of tasks include determining requirements, decomposing system requirements and identifying relevant properties (see CPM approach in

Section 2.4, etc.) [

54,

55]. Additionally, MBSE models can serve as the basis for further derived models that support activities throughout the development process [

56,

57]. The integration of MBSE and simulation models is particularly important here [

58,

59]. The modelling language ensures that the models specified are both understandable and applicable to all relevant stakeholders. The Systems Modelling Language (SysML, published by the Object Management Group (OMG), see also [

60,

61]) is used worldwide as a standard modelling language for modelling different systems. The SysML uses principles from Systems Theory and describes systems in terms of different elements and their relationships. Specific views are available for creating and utilising the elements and relations [

62,

63]. System Theory states that every system can consist of several sub-systems and that a system can be integrated into superordinate systems [

6].

Figure 4 shows an example of a bridge that is integrated into a superordinate system (so-called system context). The context of this system comprises the environment of the bridge and includes other systems, such as other structures or natural elements (e.g., the ground), as well as users. The bridge itself consists of several sub-systems, such as the piers and the sensors required for monitoring.

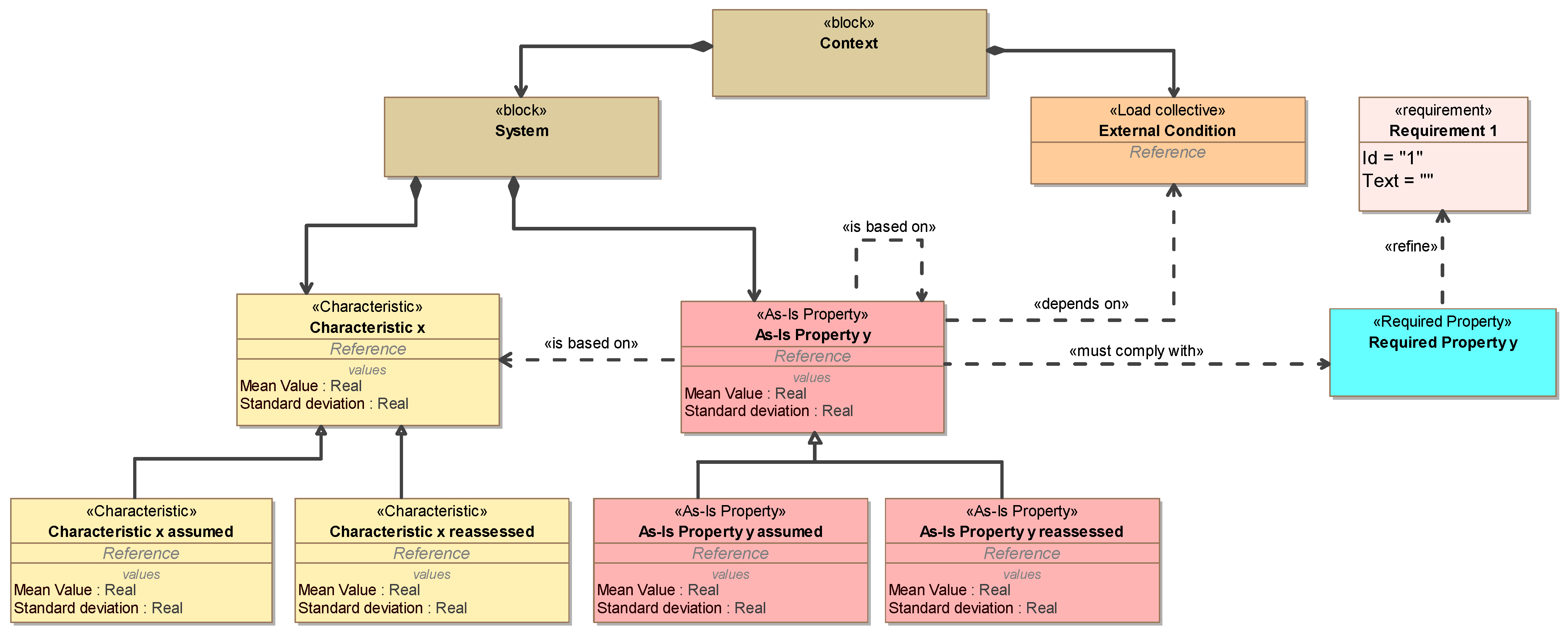

MBSE models can be extended to enable their targeted use for specific tasks. SysML models are based on metamodels that can be extended using so-called stereotypes [

63] (see also

Figure 5). This enables the creation of task- and problem-specific or domain-specific language metamodels. In addition to the modelling language, various modelling frameworks exist for specific purposes. For example, MagicGrid [

64] or SPES [

65] can be used for the development of technical systems.

MBSE approaches, especially those based on SysML, provide a systematic, structured framework for modelling and analysis. The CPM approach includes supplementary classifications for describing technical systems, in particular with a clear distinction between characteristics and as-is as well as required properties. Together, CPM/PDD and MBSE can provide a foundation for systematically supporting structural reassessment. This contribution therefore examines the combination of CPM/PDD for describing characteristics and properties, as well as iterative analysis and synthesis processes with MBSE for modelling the associated elements and their relationships, and approaches to structural reassessment.

Alternative approaches to MSBE modelling, particularly with the integration of simulations, would be possible, for example, on the basis of the Object Process Methodology (OPM) specified in the ISO 19450 standard (see e.g., [

66]). With a focus on modelling as the basis for communication between different stakeholders, this contribution follows the MBSE approach.

3. Motivation for Integrating MBSE in Structural Reassessment

The discussions in the previous sections have provided the theoretical and methodological background of reliability evaluation, model updating, and system characterisation for structural reassessment, as well as relevant aspects from the state of the art. Based upon this foundation, the current section provides the basis and rationale for incorporating these components into an MBSE framework.

The framework described in

Section 2.3 provides a systematic way of updating the structural capacity of civil engineering structures, which involves analytical modelling, stochastic parameter sampling, and Bayesian inference based on measurement data. However, with the increasing complexity of structural systems, in both construction scale and modelling capability, and with the higher dependability on monitoring data for lifecycle decisions, managing the process individually may lead to challenges in handling transparency and traceability in the work process and integration of the process within the global system lifecycle aspect. This is especially relevant for civil engineering projects in which multiple stakeholders, such as design engineers, monitoring specialists, asset owners, and regulatory bodies, operate with different tools, terminologies, and information needs throughout several decades of service life. As the structural assessment matures toward multi-physics and multi-scale evaluations, including fatigue and creep, crack initiation and propagation, and traffic-induced variability and environmental ageing, the models used within such tools become increasingly complex. To cope with this complexity, using, e.g., spreadsheets, scripts, or simulation tools, throughout the lifetime of the structure, quickly becomes unfeasible.

A main objective of MBSE is to address such challenges by offering a unified framework that organises relevant modelling aspects—ranging from the decision of structural type to maintenance based on SHM—into an interconnected system model. This includes analytical models, sensor configurations, uncertainty characterisations, and decision logic. Probabilistic information can also be integrated into the system model repository in MBSE models (e.g., via mean values and standard deviations as parameters of model elements), enabling systematic planning of SHM-based system updates using conventional model calibration or advanced Bayesian inference. However, detailed models are more appropriate for analysing probability information, especially in conjunction with appropriate visualisation.

While MBSE is widely adopted in other engineering disciplines [

67,

68,

69], combining MBSE with the structural reassessment of structures opens up new possibilities. Conventional health monitoring typically relies on historical data alone. SHM and the rise of Digital Twin technologies have recently come along to narrow this gap. MBSE can help in modelling the relevant characteristics, properties (e.g., degradation resistance, and resilience) and external conditions (e.g., excitation magnitude) as well as their relationships. Additionally, MBSE can support the planning of parameter updates using (federated) modelling to holistically combine as-is sensor data with structural models and design model, supporting dynamic updates of performance expectations based on material deterioration, environmental exposure, and operational stresses over time.

MBSE can support lifecycle traceability through the system model because revised properties as remaining capacity (e.g., bending stiffness, and allowable crack length) from track measurements propagates in an organised manner through associated models, such as predictions of load effect or design safety factors. Furthermore, MBSE can enable modular complexity management: various modelling problems, such as geometry, load models, Bayesian inference, and safety calibration, are modelled as separate but interacting sub-systems. This modularity allows engineers to adjust or extend one component, for example, sensor placement or uncertainty modelling, without compromising the overall model integrity. Through the system model representations and standardised modelling languages (e.g., SysML), MBSE can support effective communication across domains. This transits the whole assessment from local fragmented analysis to global system integration.

Furthermore, utilisation of the MBSE model can aid the transition to Digital Twins. Digital Twin becomes an ‘intelligent structure’ as a computer model, constantly updated with new observations and allowing for the prediction of structure behaviour, risk-informed decisions, and predictive maintenance planning [

22]. For instance, upon integrating the new bending stiffness into the MBSE, this can be used to feed back to subsequent design recalibration, life extension strategies, or interventions. Moreover, MBSE can also facilitate cross-disciplinary cooperation by facilitating common understanding through formal charts, requirement structures, and interdependency models (which is another way of bridging the structural engineer, data analyst, asset owner, and regulatory gaps). The formalisation ensures that each party can access the information they need at the required level of detail, and increases coordination and eliminates uncertainty.

Thus, MBSE can play a role in augmenting and scaling the existing analytical and probabilistic tools as an underlying infrastructure that links model-based design, measurement-informed updating, and system-level decision-making in a lifecycle-oriented manner. MBSE can therefore be seen as a natural and essential follow-on in the evolution of structural reassessment in data-rich and model-centric engineering environments.

4. MBSE-Supported Reassessment

As described in the previous sections, MBSE should support in managing the increasing complexity of structural reassessment. On the one hand, a systematic approach should be used when planning structural assessment measures and when reassessing the relevant properties and characteristics of structures (see

Section 4.1). The systematic approach is intended to guide the execution of the necessary steps for structural reassessment, including the interaction of the individual models and the documentation of decisions. On the other hand, MBSE is intended to provide support in the form of metamodel-based modelling to represent the relevant information on required and as-is properties, characteristics, measurements, etc., as well as their relationships in a comprehensible manner (see

Section 4.2). Both aspects, systematic approach and modelling the relevant information, can be represented and linked in one MBSE system model. This enables a holistic and traceable description.

In MBSE models, not all data from the detailed models, such as the design model, structural model, model update (Bayesian), measurement models, etc., should be stored redundantly. This would overload the MBSE models and is not beneficial to the objective of having a single source of truth due to redundancy. In addition, the tools for the detailed models often provide suitable visualisations for the content in the models. MBSE, therefore, does not replace the existing detailed models; rather, it adds a system model at a supplementary system level for planning and organisation to the existing detailed models (see

Figure 6). The detailed model parameters and measurement data are also exchanged directly between the different detailed models. As with the utilisation of MBSE for mechatronic system development, relevant—mostly more abstract—model parameters and data from the measurement are transferred to the system models for planning and organisation. This is illustrated in the schematic illustration in

Figure 6 by the different interactions.

4.1. Systematic Approach Using MBSE

Several MBSE methods already exist today (see also [

65,

70,

71]). These methods support the development of technical solutions based on the requirements (including required properties) and the analysis of the solutions with regard to the requirements. Since the objective and boundary conditions for structural reassessment differ from existing MBSE approaches, a different method is required. In structural reassessment as a basis for comparing as-is reliability properties with the reliability required by the design code, the structure already exists. This implies that assumed characteristics and properties are already available. The systematic approach must enable a comparison with the reliability specifications in the design code based on the available assumed as-is properties, including their uncertainties. If the necessary reliability cannot be ensured with the available assumed as-is properties, a reassessment must be planned. For this purpose, a monitoring system may be applied to the structure, providing productive measurement data for assessing the structural behaviour (see

Section 2.3). Based on the reassessment, the relevant as-is properties for determining reliability may subsequently be recalculated and compared with the requirements in the design code.

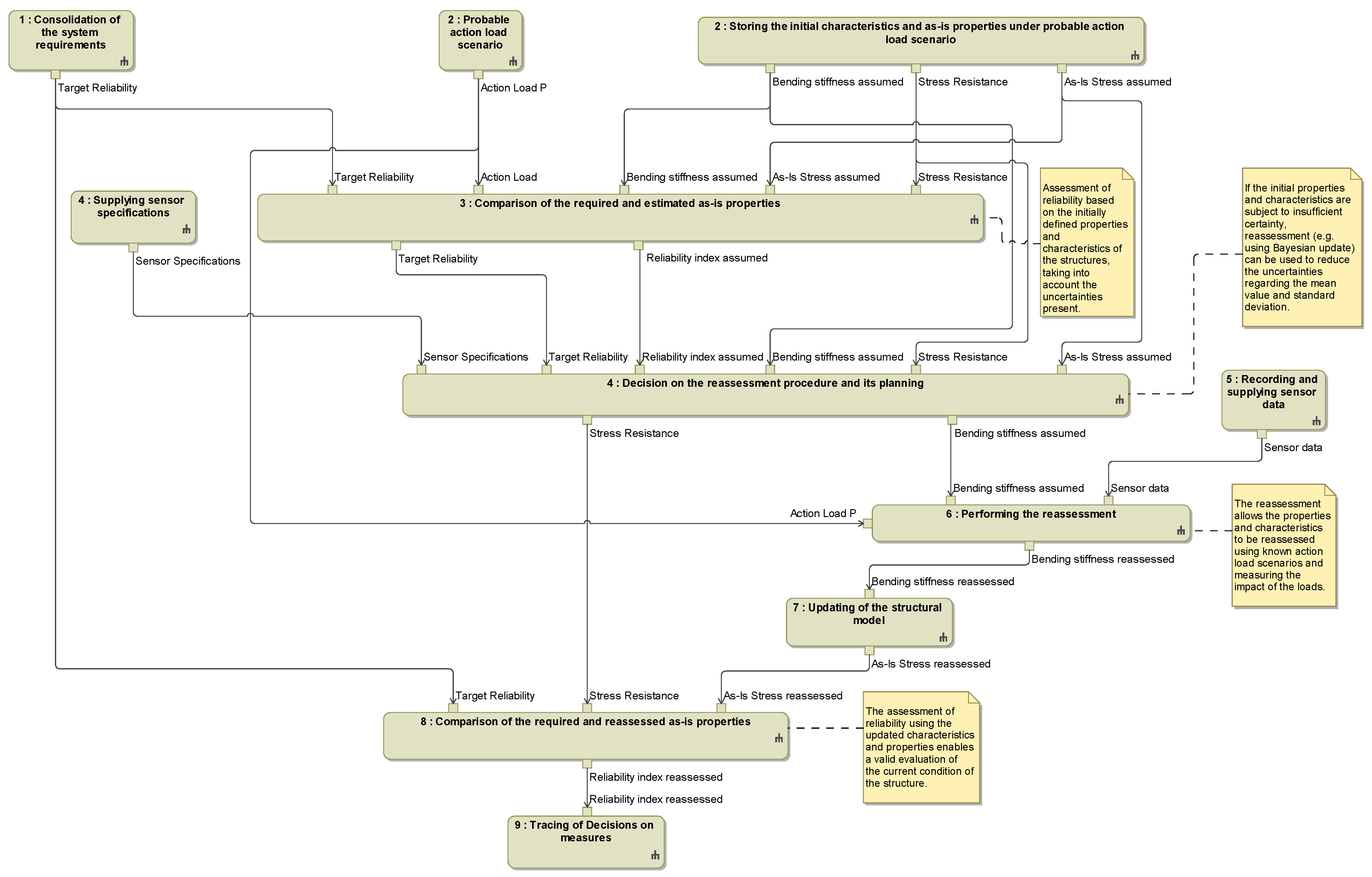

The following paragraph explains the individual steps of the MBSE-supported method proposed here. The steps of this method are shown in

Figure 7 (schematic illustration) and Figure 12 (implementation in the MBSE model). The requirements for the structure form the starting point. The requirements could originate from different stakeholders (regulatory bodies, asset owners, etc.) and reference sources (e.g., design code) and must be consolidated (step 1). In step 2, to prepare for the reassessment and the necessary measurement, the load is assumed, which in a later step serves as the basis for setting up suitable sensor systems to monitor the structural behavior. In addition, the probabilistic characteristics and as-is properties (marked as “assumed” in

Figure 8) can be derived from the initial structural models (also step 2). The comparison of the required and assumed as-is properties (step 3), including the available probability distribution, forms the basis for the decision on the overall reassessment procedure and its systematic planning (step 4). Some steps, such as step 4, involve several models (see

Figure 7). The integration of detailed parameters in conjunction with the visualisation in the structural and design model, together with the higher-level description and visualisation of relationships in the MBSE model, could, for example, support decision-making.

During the planning of the reassessment, the procedure is defined—within the context of this paper, using Bayesian inference—along with the specification of the required measurements, sensor types, and their respective locations. The necessary specifications are required from the Measuring System Model for planning the reassessment. These are also marked as step 4 in

Figure 7, as they contribute to this step. The sensor data is recorded (step 5), which is required for the reassessment. The results from the measurements are processed using the Bayesian update model to recalculate the statistical distribution of the characteristics and properties (step 6). The results are fed back into the structural and system models by supplementing the estimated properties and characteristics with the newly reassessed ones (step 7).

The comparison of the reassessed as-is properties with the required properties forms the basis for deriving measures (step 8). As described in [

28,

29,

30], a sufficiently low failure probability must be achieved for a structure to be considered safe. In the semi-probabilistic approach of the Eurocode, this requirement is represented by a target reliability index, which typically corresponds to the annual or lifetime failure probabilities that are considered acceptable for a given consequence class [

37]. If updated information about the properties and actual characteristics results in a reliability index that is significantly below this target value, the structure is classified as high risk. In this context, ‘high risk’ corresponds to situations where excessive uncertainties—for example, due to degradation mechanisms, reduced material strength, or increased variability of load effects—lead to a posterior reliability index that no longer meets the minimum safety margin implied by the design model. Excessive uncertainty may relate to unusually large standard deviations of key parameters (e.g., stiffness, and remaining cross-section capacity), broad a posteriori probability distributions, or a significant shift of the mean value of the updated resistance towards the limit state. This situation was clearly illustrated in the study of the riveted steel railway bridge in [

30]. Due to corrosion-induced cross-section loss and accumulated fatigue damage, the updated resistance distribution showed both a reduced mean value and increased dispersion. In combination with the variability of the load effects, this resulted in a posterior reliability index that was below the target value specified in the Eurocode framework. In such cases, the high-risk result indicated by the reliability assessment serves as a trigger for reassessment, targeted inspection or intervention measures. MBSE models can be used to describe the various instances of properties and characteristics and their relationship with the results of the reassessment (see

Section 4.2).

Figure 7 shows a simplified step 9 for documenting and tracing the decisions.

4.2. Template for the System Model

The systematic approach in

Section 4.1 is supported by a system model based on a metamodel. For this purpose, the system model is included at a supplementary system level to organise and federate the detailed models, as shown in

Figure 6.

In order to enable unambiguous and traceable modelling, a metamodel for elements and relations was created using a SysML profile. The metamodel was initially implemented as a template (see

Figure 8) so that specific models can be created based on the template. The template for the system model is explained in more detail below.

The system model must contain the relevant characteristics, as-is and required properties, including probability information and the relationships (traces) between these elements. Several concepts from the SysML are used to create the system model. SysML offers the option of creating specific model elements and relationships using stereotypes. Relevant parameters can be added to the stereotypes, as in the context of this paper for describing the probability information and the reference. For the system model supporting the reassessment process, this applies to model elements such as the as-is and required properties, the characteristics, and the elements of the reassessment. In addition, specific relationships are required for the systematic approach, such as “must comply with” or “is based on”.

In SysML models, views are used to present and modify elements and their relationships. These views are dynamic and adapt to changes in the model. In addition, further specific views can be created based on the elements and relationships (see, for example, the Relation Map in Figure 10). Please note that the Relation Map only shows elements and their relationships for selected types of relationships (see legend in Figure 10).

Another concept used in SysML is inheritance via generalisation relationships. This means that all inherited elements receive the properties of the source element. However, specific instances can also be created. This concept is used for instances of characteristics and as-is properties with assumed and reassessed values.

As described, the MBSE model should be introduced at a supplementary system level in order to orchestrate relevant parameters across the detailed models. In addition to the exchange of data between the detailed models, it must also be possible to exchange data between the MBSE model and the detailed models. Several approaches exist for this purpose. These include direct model couplings (e.g., via the Cameo Simulation Toolkit) or references between the models. For the investigations in this paper, references (see “Reference” in

Figure 8) representing the parameter names have been used so far. Direct model couplings are planned for future activities.

5. Application of the MBSE Approach for Reassessing Structural Capacity Incorporating SHM

The method described in

Section 4.1 and the template described in

Section 4.2 were used for the structural reassessment of the bridge explained in

Section 2.3. The modelling of the method and the model of the bridge derived from the template form two linked aspects in the MBSE model, which are intended to support both the planning and the guidance for the execution of the structural reassessment.

The MBSE model contains model elements for describing the different instances of the characteristics and properties (assumed and reassessed) of the bridge (see

Figure 9). These include the mean values and standard deviations of the characteristics and properties. The type ‘real’ was used for the values of the properties and characteristics in

Figure 9. For the purpose of simplification, no specific data types with units were assigned in the figure. To evaluate the bridge regarding structural performance and safety, the “Target Reliability Index” is required based on the design code [

37]. This must be compared with the actual reliability described by the “Reliability Index” in order to evaluate the bridge. Since the assumed properties and characteristics are initially available, the “Reliability Index” is based on the “As-Is Stress Assumed”. This depends, among other things, on the “Bending stiffness assumed”, which in turn depends on the “Cross-section” and “Young’s modulus”. After reassessment, the respective “reassessed” properties can be used. The dependencies between the properties and characteristics are described in the MBSE model via relationships. Further views can be created based on the relationships to describe the dependencies between properties and characteristics, making them clearly understandable (see

Figure 10). In addition to the specification of the bridge elements, the coupling of the sensors and the introduction of load into the bridge are also specified. To ensure traceability, the same model elements are used to model the bridge, including its properties and characteristics, and to describe the coupling of the sensors and the loads acting on the bridge, and are represented in the relevant diagrams (see for example

Figure 9). Dividing the information across several diagrams reduces visual complexity and enables problem-specific views. The diagrams for the coupling of the sensors are therefore not included in this paper.

The detailed values for the properties and characteristics come from the various models (structural model, design model, etc.). Within the scope of this work, the relationship between the parameters in the MSBE and the detailed models was initially established via name references (the name of relevant parameters from the detailed models is included in the MBSE model as a reference). One reference is shown in

Figure 9. For future work, a direct coupling (e.g., by directly calling a scripted structural model and design model from the SysML model) is also planned.

The MBSE model thus encompasses the relevant parameters and their relationships (presented in a deliberately simplified form in the paper) and can therefore support the decision on the necessary reassessment (see step 4 in

Figure 7). It is important that the MBSE model is used to supplement the decision, especially since the relationships between the parameters are clearly visualised. Detailed models, especially the structural model and design models, are always necessary for decision-making. In the MBSE model, the decision can be documented in conjunction with the parameters used for the decision.

The reassessment requires measurements which would be obtained from the real action load. For the railway bridge examined in [

28,

29,

30], this corresponds to several train passages with different masses, occurring at speeds of up to 120 km/h and at different frequencies. To ensure the traceability of the action load determination, use case diagrams and activity diagrams can be used in the MBSE model to describe the details of the scenarios (see

Figure 11). For the present use case, the scenario is simple, as the trains travel over the bridge at a known frequency. However, the loading scenarios are significantly complex for other structures.

In addition, the MBSE model includes the method description with the relevant characteristics and properties of the bridge, specifications from the design code, and the measurement data (see

Figure 12). Different models (structural model, design model, etc.) are required for the individual method steps. The model parameters are linked to the steps of the method so that it is easy to navigate between the different aspects. For the purpose of comprehensibility, the individual steps are provided with notes on the objective of each step. SysML provides corresponding nodes in the activity diagram for describing decisions (these are not included in the figures in the paper). In addition, the decision nodes can be further documented.

6. Conclusions

In the context of civil engineering, it is important to reassess the characteristics and properties of structures in order to evaluate the status of structures and derive appropriate measures to ensure their reliability. The use of real as-is data from structures through methods such as SHM provides an important basis for this. The consideration of uncertainties, the demand for traceability of decisions, the efficient utilisation of different simulation models and tools, and the necessary involvement of multiple stakeholders require systematic approaches and suitable, holistic modelling of structures. The paper proposes the coupling of Bayesian updating and SHM, based on the work of Chowdhury and Kraus [

28,

29,

30], with MBSE approaches, taking into account the modelling guidelines of the CPM approach. MBSE modelling provides an additional modelling layer that serves to orchestrate the individual detailed models. Within the MBSE models, the relevant characteristics and properties, including their instances and relations, are represented in abstract form. This enables a holistic view and analysis of the structures and plans for reassessment. The representation, which is based on SHM data and used for model updating routines, can support decisions throughout the lifecycle, for example, in maintenance planning, safety reviews, or capacity reassessments. MBSE can support data-based and traceable decision-making throughout the entire system lifecycle by linking and coordinating the parameters in the existing models with the real structural data.

The MBSE model must be coupled with relevant detailed models such that the appropriate parameters can be mapped and updated. In this contribution, this was initially conducted in a simplified manner using name references. In future activities, direct coupling via interfaces is also planned.

The approach was examined in this contribution using an idealised bridge. In order to be able to make valid statements about the usefulness and transferability, further structures must be examined and studies with several users must be carried out in future work.

Future work should also examine how models already in use today—including MBSE models—can be further utilised for Bayesian updating and SHM during the initial development of the bridge. Other open questions concern the handling of large amounts of data based on measurements taken on larger structures, additional views in MBSE tailored to the needs of different stakeholders, version management, and the integration of other domains in civil engineering. In addition, the use of SysML v2 will be investigated.