Abstract

This study examined the relationship between residential environment satisfaction, neighbor relations, and the intention of continuous residence. Previous research has not comprehensively analyzed the combined effects of these factors. Accordingly, this study investigated the influence of residential environment satisfaction on the intention of continuous residence and analyzed the mediating role of neighbor relations. Residential environments were categorized into commercial facilities, medical facilities, childcare/educational facilities, and cultural facilities. Respondents aged 20 years and above were selected from Innovation Cities where public institution relocation had been completed. Data were collected from 1606 participants through an online survey. Hypotheses were tested using mediation analysis. The results showed that residential environment satisfaction positively influenced the intention of continuous residence, with satisfaction with medical facilities having the strongest effect. In addition, neighbor relations had both direct and indirect positive effects on the intention of continuous residence, underscoring their importance in encouraging residents to remain. In many developing countries where the private market is less developed, state-owned enterprises play a crucial role in the national economy, and development is often concentrated around their locations. In the long term, relocating public institutions could serve as a strategy to address regional disparities. The findings of this study thus offer important policy implications.

1. Introduction

To mitigate regional disparities between the capital and non-capital areas and to promote balanced national development, the Korean government implemented a policy of relocating public sector institutions to non-capital regions [1,2]. The policy was first discussed in 2005, with relocation occurring between 2012 and 2019. In total, 176 public institutions were designated for relocation; following the consolidation of institutions 153 were moved either individually or to newly established Innovation Cities [3].

The effectiveness of this relocation policy has received mixed evaluations. On one hand, studies indicate that it significantly increased local tax revenues and per capita gross regional domestic product (GRDP) in the Innovation Cities [4]. Conversely, research on population dispersion suggests that while the policy had some dispersal effects until the mid-2010s, these have since diminished or plateaued. Even if relocated employees and their families settled in the region, ongoing outmigration by other residents would imply that the policy’s objectives have not been fully achieved [5,6]. Therefore, the continuous residence of local residents is a critical measure for evaluating the policy’s success.

Residents typically prefer to meet their needs and interests within their local area. When these needs are met, they are more likely to reside in the community long-term [7,8,9]. In academic terms, the intention of continuous residence relates to the concept of “settlement”. Lee et al. [8] defined residential intention as “a person’s will to remain in a given community”, and Lim [10] described it as “the willingness to continue residing in a community, based on physical and psychological satisfaction with the residential environment”.

The policy of relocating public institutions is grounded in the Framework Act on Balanced National Development, which identifies balanced development as its ultimate goal. Sustaining the local populations is a fundamental condition for achieving this aim [3]. While the initial focus was on facilitating the settlement of relocated employees and their families, this group represents only 2–3% of the total population in most regions [6]. Strengthening the intention of continuous residence among the broader population of Innovation Cities is essential to realizing the policy’s long-term objectives.

Previous studies have highlighted residential environment satisfaction, neighbor relations, and sociodemographic variables as key determinants of long-term residence. Satisfaction with the residential environment tends to increase the likelihood of settlement [11,12,13,14,15], and stronger neighbor relations are generally associated with greater local satisfaction [16,17]. However, these factors have often been treated as independent variables, without examining possible causal relationships between them. It is plausible that a high level of residential environment satisfaction fosters stronger neighbor relations [18,19,20], which in turn influence the intention to remain. This highlights the need for an integrated analytical framework in which neighbor relations are considered as a mediating variable between residential environment satisfaction and intention of continuous residence.

Against this background, the present study addresses two research questions: (1) How does satisfaction with the residential environment affect the intention of continuous residence among residents in Innovation Cities? (2) Does satisfaction with neighbor relations mediate this relationship? For the analysis, residential environment satisfaction was divided into four factor categories: commercial facilities, medical facilities, childcare/educational facilities, and cultural facilities. The mediating role of neighbor relations was examined using Baron and Kenny’s [21] mediation analysis approach. The study employed an online survey of residents of nine Innovation Cities, excluding Jeju due to its relatively small-scale relocation of public institutions. Because perceptions of the same infrastructure can vary among individuals, the use of a subjective, survey-based evaluation was deemed both meaningful and appropriate.

Finally, it is worth noting that the widening gap between large metropolitan cities and smaller cities is a global phenomenon [22,23,24]. In response, governments in countries such as the United Kingdom and France have implemented decentralization measures, including the relocation of public institutions, to counter the overconcentration of resources in major cities [25,26,27]. In this context, the findings of this study offer relevant implications for others considering public sector relocation as a means of promoting regional equity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: Innovation Cities

This study focuses on Innovation Cities in Korea where the relocation of public institutions has been completed. These planned cities were developed as part of a national strategy to reduce regional disparities between the capital and non-capital areas by relocating public institutions. Policy discussion began in 2005, and the actual relocation took place between 2012 and 2019 [4].

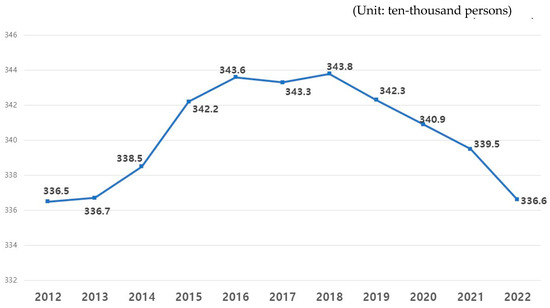

Two main reasons guided the selection of Innovation Cities as the study area. First, as the direct product of the relocation policy, these cities are appropriate for assessing the policy’s long-term effects, particularly in terms of residents’ intention to remain. Second, although population levels increased after the relocation of public institutions, many of these cities have experienced a continuous decline in population since around 2018, when the relocation process was completed (Figure 1). In contrast, Table 1 shows that the populations of both the nationwide and Seoul Capital Area have been declining since around 2020. This indicates that, although the overall population has been on a downward trend, the population decline has progressed relatively more rapidly in the Innovation Cities. This trend raises important questions about the relationship between residential environments and long-term residential intention. Accordingly, this study identifies the factors influencing continuous residence and derives policy implications for population retention in Innovation Cities.

Figure 1.

Population changes in Innovation Cities (Source: 2012–2022 Population Census by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety [28], https://jumin.mois.go.kr/#, accessed on 1 August 2025).

Table 1.

Comparison of population changes: Nationwide, Seoul Capital Area, Innovation Cities. (Unit: ten-thousand persons).

On the other hand, a more detailed examination of Innovation Cities reveals the following. While promoting the relocation of public institutions, the government simultaneously devised plans for the establishment of Innovation Cities. Innovation Cities were designated primarily in non-metropolitan areas. In the process of selecting the regions, the government considered each area’s level of development and strategic industries [3]. Innovation cities are intended to play a significant role in fostering regional development by collaborating with private enterprises in each respective area. There are 10 Innovation Cities, including Busan, Daegu, Gwangju/Jeonnam, Ulsan, Gangwon, Chungbuk, Jeonbuk, Gyeongbuk, Gyeongnam, and Jeju, and the specific details are presented in Table 2. In this study, Jeju was excluded due to its relatively limited scale of institutional relocation.

Table 2.

Overview of public institutions relocation to Innovation cities.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis Framework

This study considered satisfaction with the residential environments as a primary factor affecting the intention of continuous residence. Specifically, it examines the effect of residential environment satisfaction on intention of continuous residence and evaluates whether neighbor relations significantly mediate this relationship.

2.2.1. Effect of Residential Environment Satisfaction on Intention of Continuous Residence

Previous research consistently reports that satisfaction with the residential environment positively influences the intention of continuous residence [30,31]. During the planning and development of Innovation Cities, improvements to residential environments were implemented alongside the relocation of public institutions. For many residents, these improvements are the most tangible benefit of the policy [3,32,33].

The literature indicates that specific aspects of the residential environment can significantly shape intention of continuous residence. For example, some studies found that satisfaction with educational and commercial facilities positively influenced community satisfaction [12,13,14]. Lee [34] emphasized the importance of housing and infrastructure, while Ahmadiani [11] highlighted cultural and transportation facilities. Although not always directly examined, some studies suggest that satisfaction with the residential environment can enhance place attachment. Song and Yim [35], for example, demonstrated a causal link between satisfaction with various facilities, including commercial facilities, medical, transportation, cultural/sports facilities, and place attachment. Based on the premise that the intention of continuous residence can be shaped primarily by place attachment, these analytical results enhance the validity of this study.

Drawing on these findings, this study identifies four dimensions of residential environment satisfaction—commercial facilities, medical facilities, childcare/educational facilities, and cultural facilities—as key predictors of the intention of continuous residence. It should be noted that, whereas the residential environment is often conceptualized in the academic literature as encompassing housing itself, this study specifically focused on the external residential environment.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Satisfaction with the residential environment satisfaction in terms of (a) commercial facilities, (b) medical facilities, (c) childcare/educational facilities, and (d) cultural facilities, positively affects the intention of continuous residence among residents in Innovation Cities.

2.2.2. Mediating Effect of Neighbor Relations

Some studies suggest that neighbor relations may mediate the relationship between residential environment satisfaction and the intention of continuous residence. According to Lewicka [16], higher satisfaction with the residential environment leads to more frequent use of local spaces, increasing interpersonal interaction and trust among residents. This process enhances community satisfaction and, ultimately, intention of continuous residence. Empirical studies have treated neighbor relations both as a dependent variable influenced by the residential environment satisfaction [18,19,20] and as an independent variable affecting intention of continuous residence [14,16,17]. If both relationships are valid, neighbor relations can be considered a mediating factor between residential environment satisfaction and intention of continuous residence.

First, studies linking residential environment satisfaction and neighbor relations emphasize that the physical environment provides key venues for interaction. “Third places” such as parks and cafes, distinct from home and work, serve as spaces for relaxation and community-building, facilitating both formal and informal interactions [18]. Specifically, some studies observed that shared community spaces promote frequent interaction among residents, and studies of walkable neighborhoods confirm that pedestrian-friendly environments strengthen neighbor relations [19,20]. These findings support the premise that satisfaction with the physical environment fosters stronger neighbor relations, a principle often used in urban planning strategies that incorporate community anchor spaces [36,37].

Second, research on the link between neighbor relations and the intention of continuous residence has consistently emphasized the role of social bonds in increasing community satisfaction and place attachment. Scopelliti and Tiberio [17], for example, found that individuals with strong social ties to their hometowns displayed greater emotional attachment. Özkan and Yilmaz [14] reported similar findings, noting that participation in formal and informal social activities positively influenced place attachment. Lewicka [16] further argued that satisfaction with neighbor relations transforms “space” into a “meaningful place”, enhancing community satisfaction.

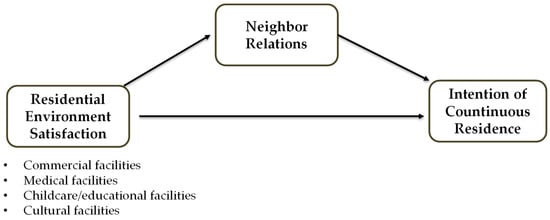

These studies suggest that even if the residential environment does not directly influence the intention of continuous residence, it may do so indirectly through its effect on neighbor relations. Furthermore, the presence of this mediating pathway may strengthen the overall effect of residential environment satisfaction on intention of continuous residence. Figure 2 shows the relationship between main factors.

Figure 2.

Research Model.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Neighbor relations mediate the relationship between residential environment satisfaction, specifically, satisfaction with (a) commercial facilities, (b) medical facilities, (c) childcare/educational facilities, and (d) cultural facilities, and the intention of continuous residence.

2.3. Measures

The questionnaire was developed by reviewing previous literature and revising items to suit the context of this study. Responses to all items were measured using a four-point Likert scale of very dissatisfied (1), dissatisfied (2), satisfied (3), and very satisfied (4). First, the intention of continuous residence was measured with a single item assessing the respondent’s willingness to remain in their current location [33]. The specific questionnaire item stated, ‘I intend to remain in my current residential area on a continuous basis’.

Next, residential environmental satisfaction was divided into four subdimensions and was based on the related studies [35,38,39,40].

Commercial facilities: satisfaction with convenience stores, restaurants, and large-scale supermarkets.

Medical facilities: satisfaction with local clinics, dental clinics, pharmacies, and general hospitals.

Childcare/educational facilities: satisfaction with elementary schools, middle and high schools, kindergartens, and other educational institutions.

Cultural facilities: satisfaction with performance venues, movie theaters, and public libraries.

Finally, neighbor relations were measured with three items: frequency of conversations with neighbors, level of acquaintance with neighbors, and trust in neighbors [41].

In addition, previous studies highlight the importance of controlling for residential factors (housing tenure, length of residence, number of household members, and regional size) and demographical factors (gender, age, and monthly household income) when analyzing the intention of continuous residence [42,43,44]. These variables were therefore included as control variables.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected through an online survey of residents in Innovation Cities. The target sample size was set at 1500 respondents, with approximately 166–167 individuals from each of the nine regions. This quota sampling method was used to minimize bias from population disparities across regions. For example, while Busan has approximately 640,000 residents, Gwangju/Jeonnam has only about 97,000; without stratification, smaller cities could be underrepresented. Within each region, the samples were further stratified by age distribution to enhance representativeness. A screening question was used to verify residency before participants received the survey link by email. Progress was monitored to ensure quota fulfillment by both region and age group.

The survey was conducted from 4 September to 11 September 2023, yielding 1606 valid responses. Sample characteristics are shown in Table 3. Of the respondents, 707 were male (44.0%) and 899 were female (56.0%). The largest age group was 60 years and older (539 respondents, 33.6%). The most common monthly household income category was above 6 million KRW (397 respondents, 24.7%). Two-person households (457 respondents, 28.5%) were almost as common as households with four or more members (466 respondents, 29.0%). Homeowners (1176 respondents, 73.2%) outnumbered renters (430 respondents, 26.8%). The largest group by length of residence had lived in their homes for 15–30 years (442 respondents, 27.5%). Most respondents resided in non-metropolitan areas (1060 respondents, 66.0%).

Table 3.

Sample characteristics.

2.5. Analytical Method

Data from the online survey were analyzed in three main steps using SPSS v.23 (Table 4):

Table 4.

Analytic method.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA): Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was performed to assess the construct. Reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha tested the internal consistency of each construct.

Descriptive and correlation analysis: Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine relationships between key factors and to check for multicollinearity.

Mediation analysis: Following the three-step approach by Baron and Kenny [21]:

Model 1: The independent variable (X) must significantly predict the dependent variable (Y).

Model 2: X significantly influences the mediator (M).

Model 3: When X and M are both included, M must significantly predict Y and the coefficient for X (B31) must be smaller than in Model 1 (B11).

To test the significance of indirect effects, a bootstrapping method was applied using PROCESS Macro v3.3 with 5000 resamples and 90% confidence intervals (CIs). An indirect effect was considered significant if the CI did not include zero.

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Reliability

Because some constructs in this study consisted of multiple items, EFA and reliability testing were conducted to validate residential environment satisfaction and neighbor relations (Table 5). Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was applied to the 17 items. The analysis extracted five distinct factors, each with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0 and factor loadings above 0.5, indicating satisfactory construct validity [45]. The internal consistency of each factor was assessed using Cronbach’s α. All five factors recorded Cronbach’s α values above the generally accepted threshold of 0.6 [45], confirming adequate reliability.

Table 5.

Exploratory factor analysis and reliability results.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for the main variables are reported in Table 6. Among the subcomponents of residential environment satisfaction, satisfaction with commercial facilities had the highest mean (M = 2.89), followed by satisfaction with medical facilities and childcare/educational facilities (both M = 2.74). Satisfaction with cultural facilities was the lowest (M = 2.51).

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between factors.

The mean score for neighbor relations was 2.20, the lowest among all variables, while the intention of continuous residence recorded the highest mean (M = 2.95). Pearson correlation analysis indicated that all variables were significantly and positively correlated at the 1% level. Notably, no correlation coefficients exceeded 0.7, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a concern and that the constructs were empirically distinct.

3.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of residential environment satisfaction on the intention of continuous residence, with particular focus on the mediating role of neighbor relations. Following the procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny [21], the mediation analysis incorporated the following control variables: gender, age, length of residence, number of household members, monthly household income, housing tenure, and regional size.

For Hypothesis 1, it was proposed that residential environment satisfaction would positively influence the intention of continuous residence. This was tested in Model 1 (Table 7). Before hypothesis testing, the explanatory power of the model was examined, with the coefficient of determination (R2) found to be 0.144 (14.4%). Although no absolute standard exists for R2, in the social sciences, where survey data are predominantly used, values exceeding 0.13 are generally considered acceptable. Furthermore, examination of multicollinearity revealed that all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.015 to 1.852, which are well below the commonly accepted threshold of 10, indicating no multicollinearity concerns [46].

Table 7.

Mediating effect analysis.

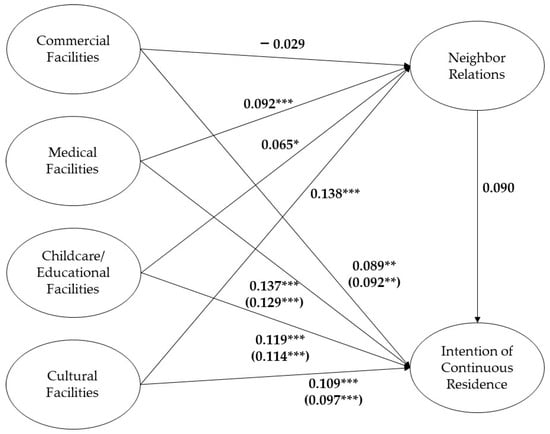

The results indicate that satisfaction with commercial facilities (B = 0.089, p < 0.05), medical facilities (B = 0.139, p < 0.01), childcare/educational facilities (B = 0.119, p < 0.01), and cultural facilities (B = 0.109, p < 0.01)—all subcomponents of residential environment satisfaction—had significant positive effects on the intention of continuous residence. In other words, higher satisfaction with these aspects of the residential environment was associated with stronger intention to remain. These findings support Hypothesis 1. Among these predictors, satisfaction with medical facilities exerted the greatest influence, followed by childcare/educational facilities, and cultural facilities, as reflected in the size of their regression coefficients. Previous studies similarly highlight the importance of physical residential infrastructure, particularly medical and cultural facilities, in shaping residents’ satisfaction and their intention to remain in the area. Among the control variables, age (B = 0.002, p < 0.1), length of residence (B = 0.000, p < 0.01), and monthly household income (B = 0.048, p < 0.01) were significant predictors of the intention of continuous residence. Specifically, older individuals, those with longer periods of residence, and households with higher incomes were more likely to express intention to continue living in their current location.

For Hypothesis 2, it was proposed that satisfaction with neighbor relations would mediate the relationship between residential environmental satisfaction and the intention of continuous residence. Mediation analysis was conducted in accordance with the steps proposed by Baron and Kenny [21]. As confirmed in Model 1, all subcomponents of residential environmental satisfaction had a significant effect on the intention of continuous residence.

The results for Model 2 (Table 7) show that the explanatory power of the model was 13.4% (R2 = 0.134), with VIF values again ranging from 1.015 to 1.852, indicating no multicollinearity. Satisfaction with medical facilities (B = 0.092, p < 0.01), childcare/educational facilities (B = 0.065, p < 0.1), and cultural facilities (B = 0.138, p < 0.01) had statistically significant positive effects on neighbor relations, while satisfaction with commercial facilities did not. Among these, satisfaction with cultural facilities exerted the strongest influence. These findings align with Anchor Facility Theory, which posits that cultural facilities serve as key anchor institutions in a community [36,37]. Greater satisfaction with such facilities may encourage more frequent use, thereby fostering social interaction and stronger neighbor relations.

In Model 3, both residential environment satisfaction and neighbor relations were included as predictors of the intention of continuous residence. The explanatory power of this model was 15.0%, and the VIF values ranged from 1.018 to 1.856, again indicating no multicollinearity. Neighbor relations (B = 0.090, p < 0.01) had a statistically significant positive effect on the intention of continuous residence. Furthermore, the regression coefficients for satisfaction with medical facilities (B = 0.129, p < 0.01), childcare/educational facilities (B = 0.114, p < 0.01), and cultural facilities (B = 0.114, p < 0.01) were smaller in Model 3 compared with Model 1, consistent with the presence of partial mediation. These results suggest that neighbor relations mediate the effects of satisfaction with medical, childcare/educational, and cultural facilities on the intention of continuous residence. These analysis results from Model 2 and 3 provide partial support for Hypothesis 2.

To further test the significance of the mediation, bootstrapping was employed (Table 8). Following Preacher et al. [47], mediation is deemed statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect does not include zero. The bootstrapping results confirmed significant indirect effects of neighbor relations in the relationships involving satisfaction with medical facilities, childcare/educational facilities, and cultural facilities, but not in the relationship involving commercial facilities. Specifically, the indirect effects were 0.008 for medical facilities, 0.005 for childcare/educational facilities, and 0.012 for cultural facilities, with the largest indirect effect observed for cultural facilities. This underscores the role of cultural facilities in fostering social connectedness, which in turn contributes to residents’ intention of continuous residence. Finally, the relationships among the variables are presented in Figure 3.

Table 8.

Statistical significance of the indirect effects (bootstrap analysis).

Figure 3.

Relationships among variables. Note. a(a’): a-Total effect, a’-Direct Effect, * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

This study examined the factors influencing residents’ intention to continue residing in Innovation Cities following the relocation of public institutions. The findings offer several important implications.

First, residential environment satisfaction was found to have a significant and positive effect on the intention of continuous residence. This suggests that when individual needs are met within the residential environment, residents are more inclined to remain in the current region [8]. These findings are consistent with previous research that identifies the physical quality of the residential environment as a key determinant of long-term settlement. For example, previous studies have shown that the availability and accessibility of community facilities significantly influence decisions to reside continuously [12,13,14]. Therefore, improving residential environments is essential for enhancing long-term settlement in Innovation Cities. Policy initiatives should reflect local needs and actively incorporate resident feedback in the planning and execution of improvement projects. Among the four subcomponents analyzed in this study, satisfaction with medical facilities had the strongest influence on the intention of continuous residence. This result is particularly relevant for non-metropolitan regions in Korea, where limited access to healthcare often compels residents to seek services in the capital region [48].

Second, the study confirmed the mediating role of neighbor relations between certain dimensions of residential satisfaction and the intention of continuous residence. This distinguishes the current study from previous research by integrating a social dimension into the analysis framework. Specifically, the pathway “residential environment satisfaction → neighbor relations → intention of continuous residence” was statistically significant. This has two notable implications. Firstly, neighbor relations directly influence the intention of continuous residence: residents who are more satisfied with interactions and relationships in their neighborhood are more likely to stay. This aligns with prior studies identifying neighborhood-based social capital as a driver of long-term settlement residence [14,16,17]. Secondly, neighbor relations strengthen the effect of residential environmental satisfaction on settlement intention, meaning the positive impact of a satisfactory physical environment is amplified when strong neighbor relations are present.

The mediation analysis further revealed that among the subcomponents of residential environment satisfaction, cultural facilities had the strongest indirect effect through neighbor relations. This result may be attributed to their role as community anchor facilities, such as libraries and performance venues, that provide spaces for interaction and social engagement. Previous studies indicate that such facilities enhance community cohesion by increasing opportunities for contact and communication [36,37]. Consequently, high satisfaction with cultural facilities can promote their use, which fosters stronger neighbor relations and, in turn, reinforces the intention to remain in the community.

Taken together, these results indicate that neighbor relations exert both direct and indirect effects on the intention of continuous residence, underscoring the importance of considering both physical and social dimensions of the residential environment in policy-making. Given that the relocation of public institutions often triggers an influx of new residents and the construction of large-scale housing developments, fostering social cohesion becomes crucial. Some studies have suggested that the development of social capital—built on relationships and trust among residents—can play an important role in shaping their intention of continuous residence. In other words, residents tend to exhibit a higher intention to remain in areas where interpersonal trust is well established [16,49]. Local governments should therefore implement community engagement programs and invest in social infrastructure that facilitates neighborly interaction and integration.

Additionally, this study compared how the factors influencing the intention of continuous residence differ between metropolitan and non-metropolitan Innovation Cities (Appendix A). In fact, Innovation Cities include both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, which differ in their levels of development. This implies that residents’ perceptions of residential environment and neighbor relations may also vary between the two types of regions. The analysis results revealed that, in metropolitan Innovation Cities, cultural facilities had the greatest impact on the intention of continuous residence, whereas in non-metropolitan Innovation Cities, childcare/educational facilities exerted the strongest influence. These findings provide policy implications, suggesting the need for differentiated approaches based on the scale of the regions.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the factors influencing residents’ intention of continuous residence in Innovation Cities where public institution relocation has been completed. An online survey was conducted with residents of areas receiving relocated institutions, and empirical analysis was applied to the collected data. Specifically, the study assessed the impact of residential environment satisfaction on intention of continuous residence and tested the mediating role of neighbor relations. This study was situated in the context of significant government investment aimed at improving residential conditions.

This study offers the following contributions. First, it provides an empirical evaluation of a major policy intervention. Regional disparities remain one of the most pressing challenges in Korean society [50], and relocating public institutions to non-metropolitan areas has been among the strongest strategies to address this imbalance [3]. This study assesses whether such initiatives can contribute to mitigating population decline in these regions. Second, unlike most previous studies, this study examines intention of continuous residence among native residents of Innovation Cities. Previous studies have focused on policy performance indicators, such as changes in GRDP, local tax revenues, and business establishments, or on whether relocated employees and their families settle in the region [6,32]. However, the continued residence of long-term local inhabitants is also a critical criterion for evaluating relocation policy effectiveness.

The findings are also relevant beyond Korea. In many developing countries with less mature private sectors, state-owned enterprises play a critical role in driving national economic growth [51,52,53]. As in the Korean case, geographic concentration of these enterprises can exacerbate regional inequalities. Relocating public enterprises can therefore be considered as a potential strategy for balanced regional development, representing a common stage in national development [54]. Drawing from Korea’s experience, this study highlights key considerations for designing and implementing relocation policies, offering insights for other countries where the public sector remains dominant.

Finally, certain limitations should be noted. First, the survey was conducted among residents of selected Innovation Cities, not all residents nationwide. Although certain regional characteristics were taken into account during the data collection process, limitations in representativeness may still exist. This raises the possibility that the characteristics of specific groups may have been disproportionately reflected in the analytical data. Thus, future studies should employ larger and more representative samples, as well as longitudinal data, to capture changes in satisfaction and settlement intentions over time. Second, it is necessary to complement the survey results by conducting further analyses based on objective data, such as actual population mobility statistics and regional infrastructure information. Third, there is a need to consider a broader set of determinants affecting the intention of continuous residence. For example, Wen et al. [55] analyzed the factors influencing the intention of continuous residence in China. Their findings revealed that city economic level, public service capacity, and environmental quality were significant determinants. This suggests that, in addition to medical and cultural facilities identified in this study, various other factors may also affect the intention of continuous residence, and future research should take these factors into consideration.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to researchers’ private property.

Acknowledgments

This study conducted its analysis based on data collected during a research project carried out at the Korea Institute of Public Finance (KIPF). The authors would like to express their gratitude to the KIPF for its support in facilitating the data collection process. Moreover, the authors want to thank the editors and the reviewers for their constructive comments that helped improve the quality of the current paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Determinants of intention of continuous residence: regional comparison.

Table A1.

Determinants of intention of continuous residence: regional comparison.

| Metropolitan Cities | Non-Metropolitan Cities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (S.E.) | β | B (S.E.) | β | |

| (Constant) | 1.242 (0.203) | 1.304 (0.182) | ||

| Gender (ref. female) | 0.059 (0.049) | 0.047 | −0.083 (0.047) | −0.053 * |

| Age | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.054 | 0.000 (0.002) | 0.007 |

| Length of residence | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.032 | 0.001 (0.000) | 0.151 *** |

| Number of household members | −0.006 (0.026) | −0.011 | −0.015 (0.022) | −0.022 |

| Monthly household income | 0.002 (0.017) | 0.004 | 0.072 (0.015) | 0.151 *** |

| Housing tenure (ref. renters) | 0.155 (0.062) | 0.110 ** | −0.023 (0.055) | −0.013 |

| Commercial facilities | 0.130 (0.053) | 0.126 ** | 0.076 (0.050) | 0.056 |

| Medical facilities | 0.158 (0.055) | 0.155 *** | 0.116 (0.046) | 0.095 ** |

| Childcare/educational facilities | 0.021 (0.056) | 0.019 | 0.164 (0.054) | 0.119 *** |

| Cultural facilities | 0.153 (0.046) | 0.164 *** | 0.067 (0.044) | 0.058 |

| Neighbor relations | 0.065 (0.040) | 0.067 | 0.100 (0.036) | 0.085 *** |

| R2 | 0.194 | 0.142 | ||

| F | 11.668 *** | 16.883 *** | ||

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

References

- Jung, H. Relocation of Public Institutions and Local Public Finance: Evidence from South Korea. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2024, 90, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Lee, J.; Koo, J.H. The Influx of Youth as an Effect of the New Town Development Policy through Relocation of Public Institutions: Focusing on Differences between Large and Medium/Small-City Location Types. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 968–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). White Paper on the Relocation of Public Institutions and the Construction of Innovation Cities, 2003–2015; MOLIT: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2016. (In Korean)

- Kim, J. A Study on the Economic Impact of Public Sector Relocation and Innovative City Development. J. Local Gov. Stud. 2022, 26, 119–145. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Min, S.; Kim, E.; Seo, Y. Evaluation of 15 Years of Innovation City Achievements and Future Development Strategies; National Land Policy Brief; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements (KRIHS): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2020. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Y. Effects and Policy Directions of the Relocation of Public Institutions; KDI Policy Forum, No. 283; Korea Development Institute (KDI): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Alemu, L.S.; Berhanu, W.; Sokkido, D.L. Determinants of residential adjustment intentions: Insights from low-cost condominium housing in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1565545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, H.; Jung, W. An analysis on the factors to affect the settlement consciousness of inhabitants. Korean Assoc. Policy Stud. 2004, 13, 147–167. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Mashio, T. Relationship between Subjective Well-Being and the Intention to Reside in a Specific Region: A Case Study in Wajima City, Ishikawa Prefecture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. A Study on the Perception of Urban Satisfaction and the Consciousness of Inhabitant in Seoul -Focusing on the Satisfaction of Living Environment and Urban Risk. J. Real Estate Stud. 2015, 62, 107–120. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadiani, M.; Ferreira, S. Environmental amenities and quality of life across the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Manca, S. Healthy Residential Environments for the Elderly. In International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life; Fleury-Bahi, G., Pol, E., Navarro, O., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijlenburg, R. Teaching urban facility management, global citizenship and livability. Facilities 2020, 38, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, D.G.; Yilmaz, S. The effects of physical and social attributes of place on place attachment: A case study on Trabzon urban squares. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. Residential Satisfaction, Moving Intention and Moving Behaviours: A Study of Redeveloped Neighbourhoods in Inner-City Beijing. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Tiberio, L. Homesickness in University Students: The Role of Multiple Place Attachment. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.; Kerr, J.; Rosenberg, D.; King, A. Healthy Aging and Where You Live: Community Design Relationship with Physical Activity and Body Weight in Older Americans. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7 (Suppl. S1), S82–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H.; Hur, M. The Relationship between Walkability and Neighborhood Social Environment: The Importance of Physical and Perceived Walkability. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 62, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H. Pedestrian environments and sense of community. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2002, 21, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, P.A.; Jara-Figueroa, C.; Petralia, S.G.; Steijn, M.P.A.; Rigby, D.L.; Hidalgo, C.A. Complex Economic Activities Concentrate in Large Cities. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganong, P.; Shoag, D. Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined? J. Urban Econ. 2017, 102, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J. French Public Agencies Relocation Policy. J. Local Gov. Stud. 2006, 9, 171–189. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Faggio, G. Relocation of Public Sector Workers: Evaluating a Place-Based Policy. J. Urban Econ. 2019, 111, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.N.; Bradley, D.; Hodgson, C.; Alderman, N.; Richardson, R. Relocation, Relocation, Relocation: Assessing the Case for Public Sector Dispersal. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety. 2012–2022 Population Census in Innovation Cities. Available online: https://jumin.mois.go.kr/# (accessed on 1 August 2025). (In Korean)

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Innovation Cuty Development Promotion Team. Available online: https://innocity.molit.go.kr (accessed on 10 September 2025). (In Korean)

- He, L.; Wang, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H.; Lu, J. Psychological Needs and Social Comparison: A Dual Analysis of the Life Satisfaction of Local Workers with Agricultural Hukou. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Gao, T.; Young, R.F. How does residents’ satisfaction with community services influence quality of life (QOL) outcomes? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2008, 3, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Kim, J.; Ha, S.; Hyun, T.; Kim, G. Analysis of Regional Development Effects of the Relocation of Public Institutions and Strategies for Maximization; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements (KRIHS): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2015. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, O.K.; Kang, E.T.; Ma, K.R. A Study on the Impact of the Urban Decline on the Subjective Well-being of Residents. J. Korean Reg. Sci. Assoc. 2019, 35, 33–47. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y. Relationship between Public Service Satisfaction and Intention of Continuous Residence of Younger Generations in Rural Areas: The Case of Jeonbuk, Korea. Land 2021, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Yim, S.K. Theoretical Exploration of Social Sustainability for the Qualitative Development of Cities. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2015, 50, 677–694. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Clopton, A.W.; Finch, B.L. Re-Conceptualizing Social Anchors in Community Development: Utilizing Social Anchor Theory to Create Social Capital’s Third Dimension. Community Dev. 2011, 42, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifried, C.; Clopton, A.W. An Alternative View of Public Subsidy and Sport Facilities through Social Anchor Theory. City Cult. Soc. 2013, 4, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Walle, S.; Kampen, J.; Bouckaert, G. Deep Impact for High Impact Agencies?: Assessing the Role of Bureaucratic Encounters in Evaluations of Government. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2005, 28, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, G.G. Pieces of a puzzle: Linking government performance, Citizen satisfaction, and trust. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2007, 30, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Laegried, P. Trust in government: The relative importance of service satisfaction, political factors, and demography. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2005, 28, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Jeong, M.G. Residential environmental satisfaction, social capital, and place attachment: The case of Seoul, Korea. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.L.; Hwang, J. Indigenous Places and the Making of Undocumented Status in Mexico-US Migration. Int. Migr. Rev. 2019, 53, 1032–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra, P.; Massey, D.S. Processes of Internal and International Migration from Chitwan, Nepal. Int. Migr. Rev. 2009, 43, 621–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Andersen, B. Why do people wish to stay or move in high-density cities? Long-term residential intentions in compact urban environments. Cities 2024, 147, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Lim, J.H. SPSS 24 Manual; JypHyunJae Publishing Co.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.H. Easyflow Regression Analysis; Hannarae Publishing, Co.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Sohn, M.; Choi, M. Unmet Healthcare Needs and the Local Extinction Index: An Analysis of Regional Disparities Impacting South Korea’s Older Adults. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1423108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolever, C. A Contextual Approach to Neighborhood Attachment. Urban Stud. 1992, 29, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ishiro, T. Regional Economic Analysis of Major Areas in South Korea: Using 2005–2010–2015 Multi-Regional Input–Output Tables. Econ. Struct. 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. State-Owned Enterprises in the Development Process; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Listing State-Owned Enterprises in Emerging and Developing Economies: Lessons from 30 Years of Success and Failure; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alfred, G. Nhema. Privatisation of Public Enterprises in Developing Countries: Case for State Ownership When Private Sector Is Weak. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 242–250. Available online: https://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_5_No_9_September_2015/26.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Xu, Y.; Lozhnikova, A.; Kichko, N. Outward relocation of central state-owned enterprises headquarters: Impact on local tax base and economy. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, L. Intercity mobility pattern and settlement intention: Evidence from China. Comput. Urban Sci. 2022, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).