The Impact of the “Inclusion of Rehabilitation Services in Basic Medical Insurance” Policy on the Utilization of Rehabilitation Services and Household Healthcare Expenditure Among Older Adults with Disabilities: Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

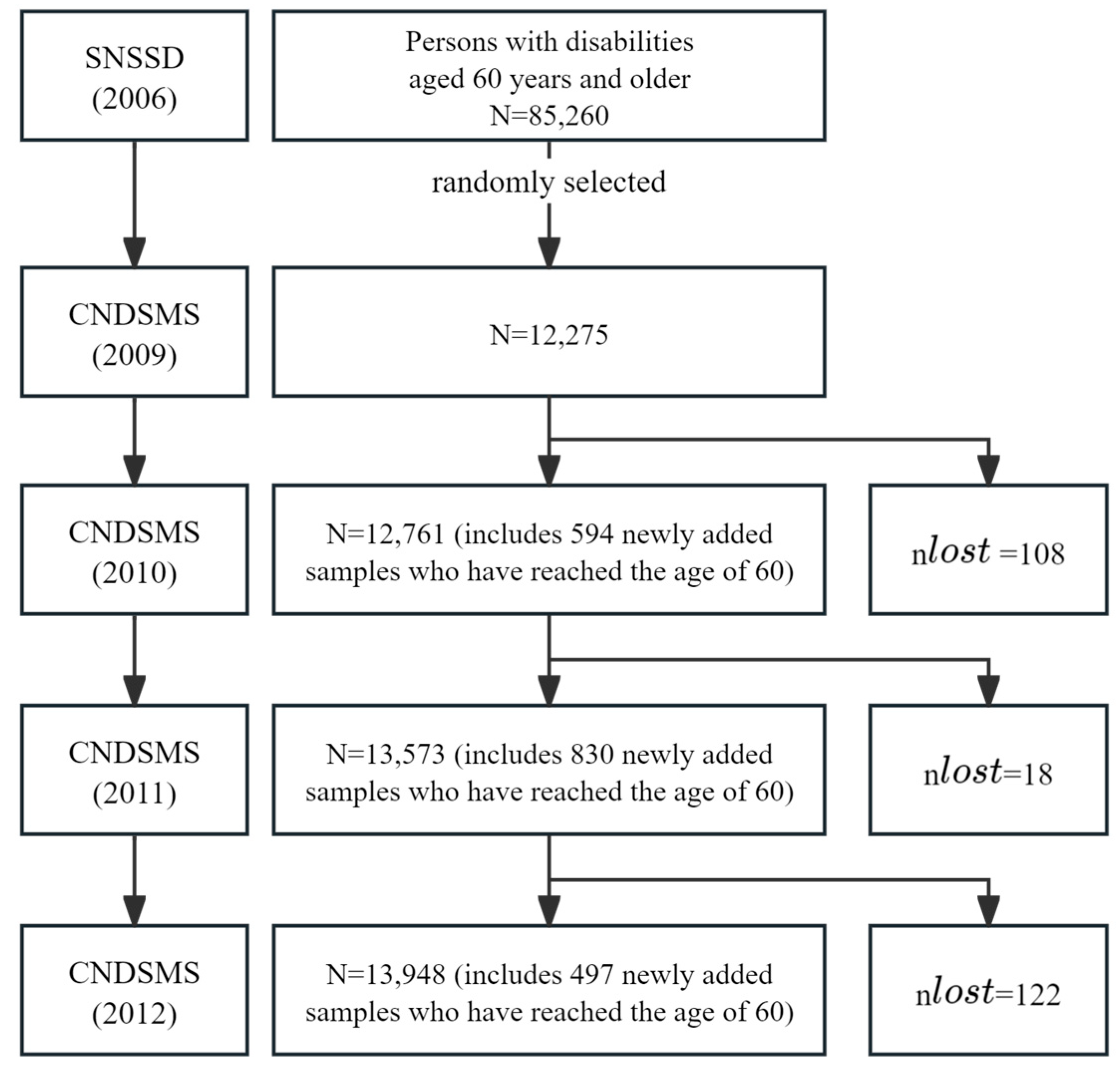

2.1. Data Source

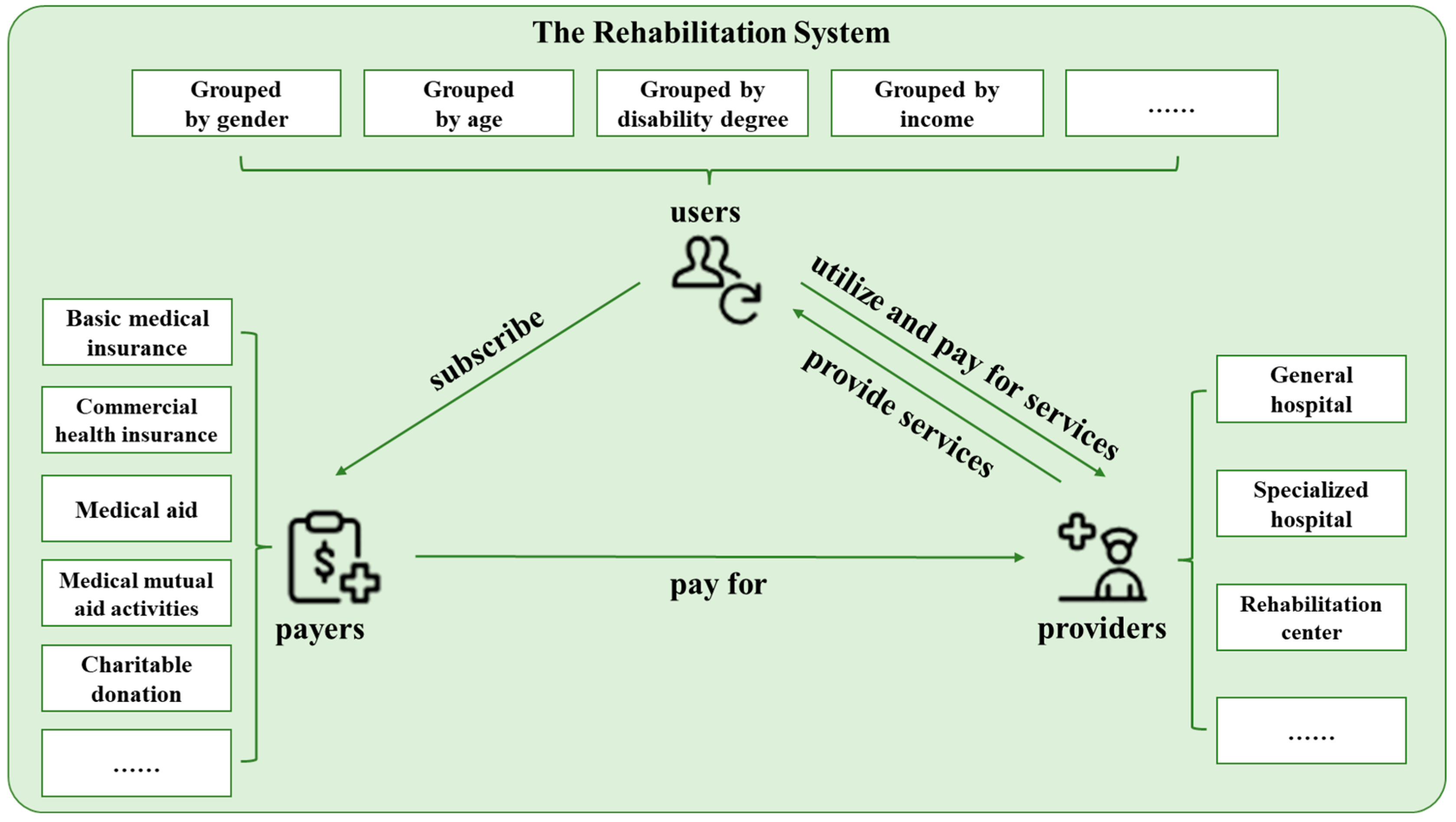

2.2. Core Concepts

2.2.1. Disability

2.2.2. Rehabilitation and Utilization of Rehabilitation Services

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Heckman Two-Stage Method

2.4.2. Difference in Differences (DIDs) Method

2.4.3. Baron and Kenny’s Three-Step Mediation Effect Method

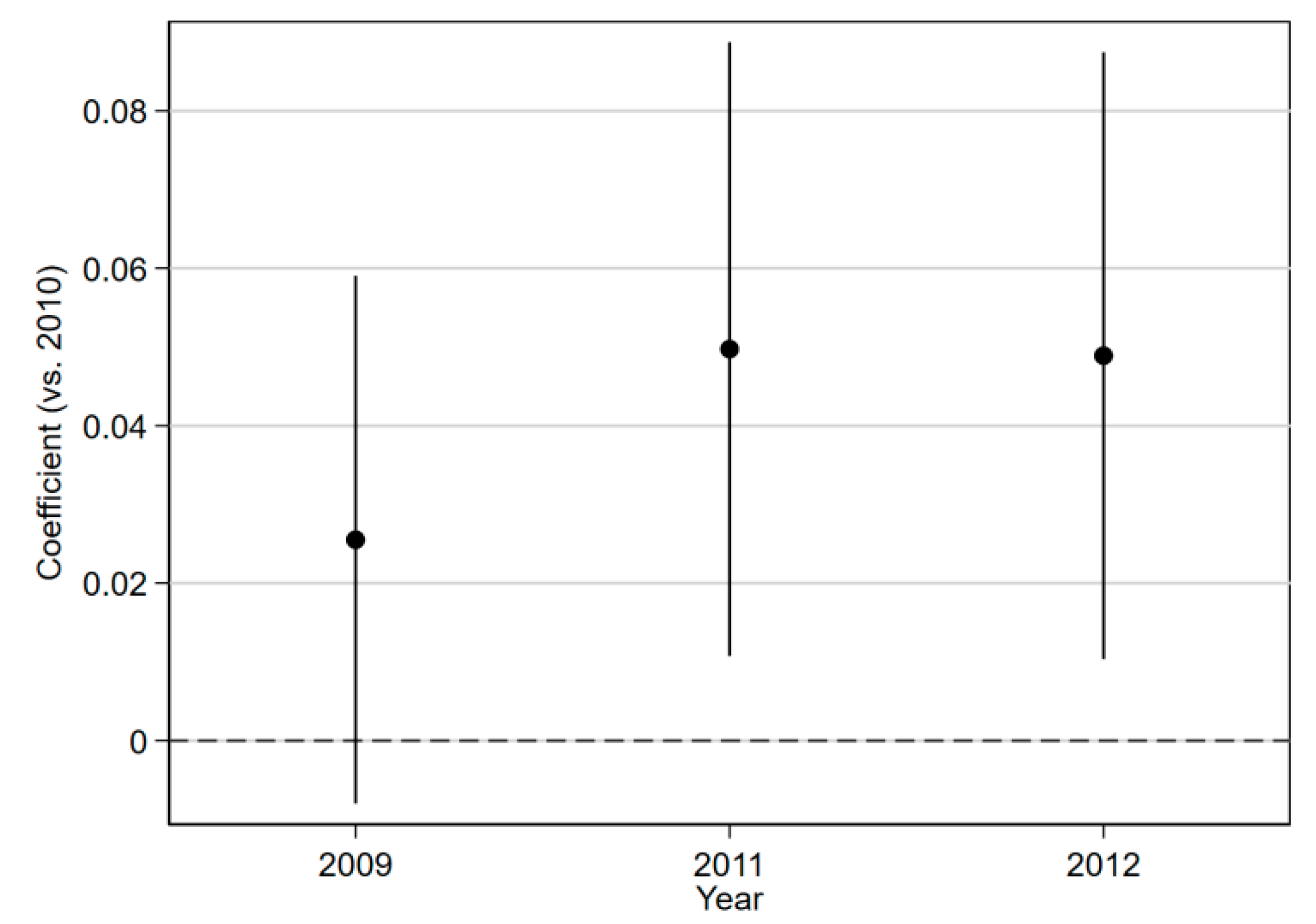

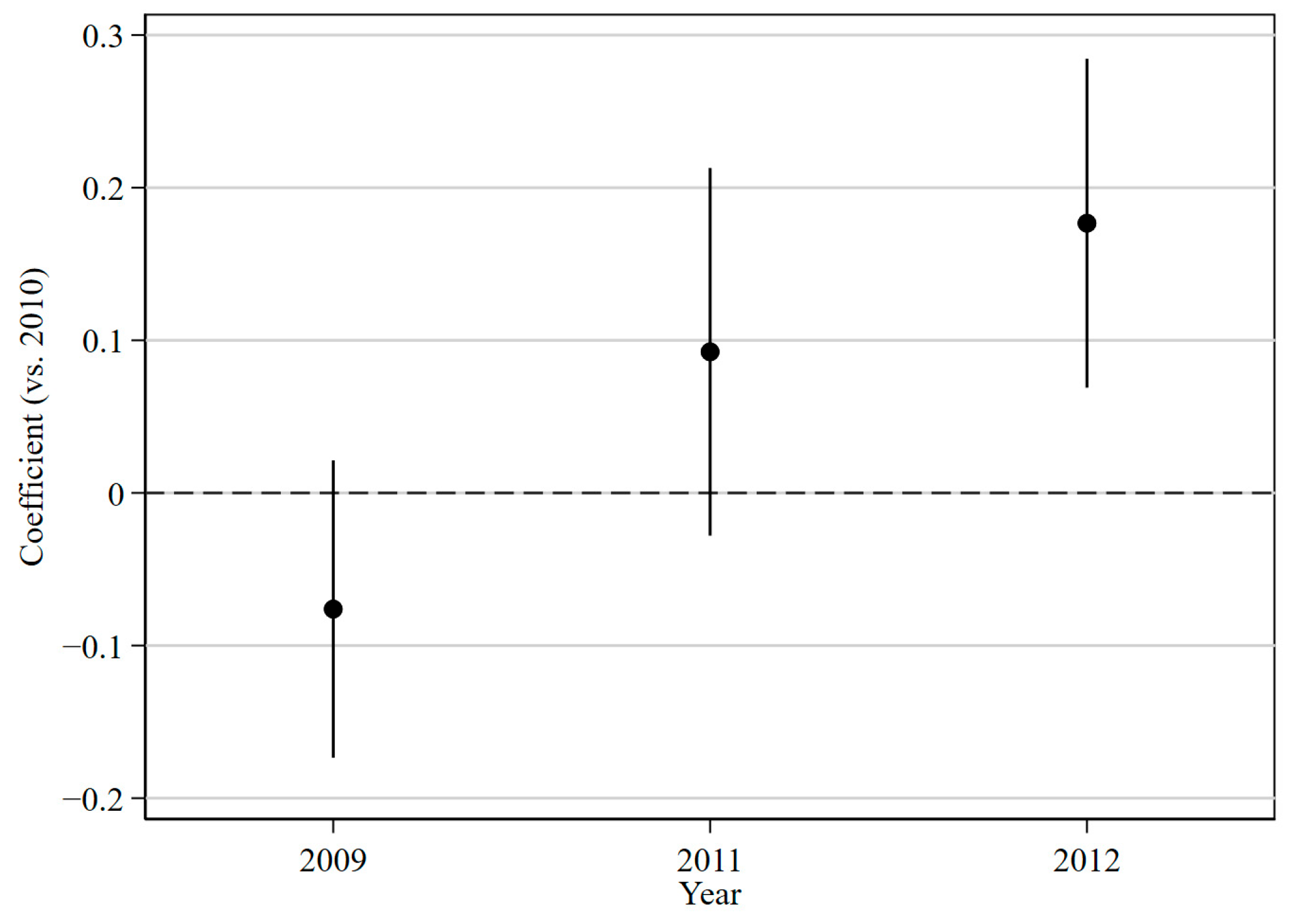

2.4.4. Event-Study Method

3. Results

3.1. Utilization Rates of Rehabilitation Services for Older Adults with Disabilities in the Experimental and Control Groups from 2009 to 2012

3.2. Impact of the Rehabilitation Coverage Policy on the Utilization of Rehabilitation Services by Older Adults with Disabilities

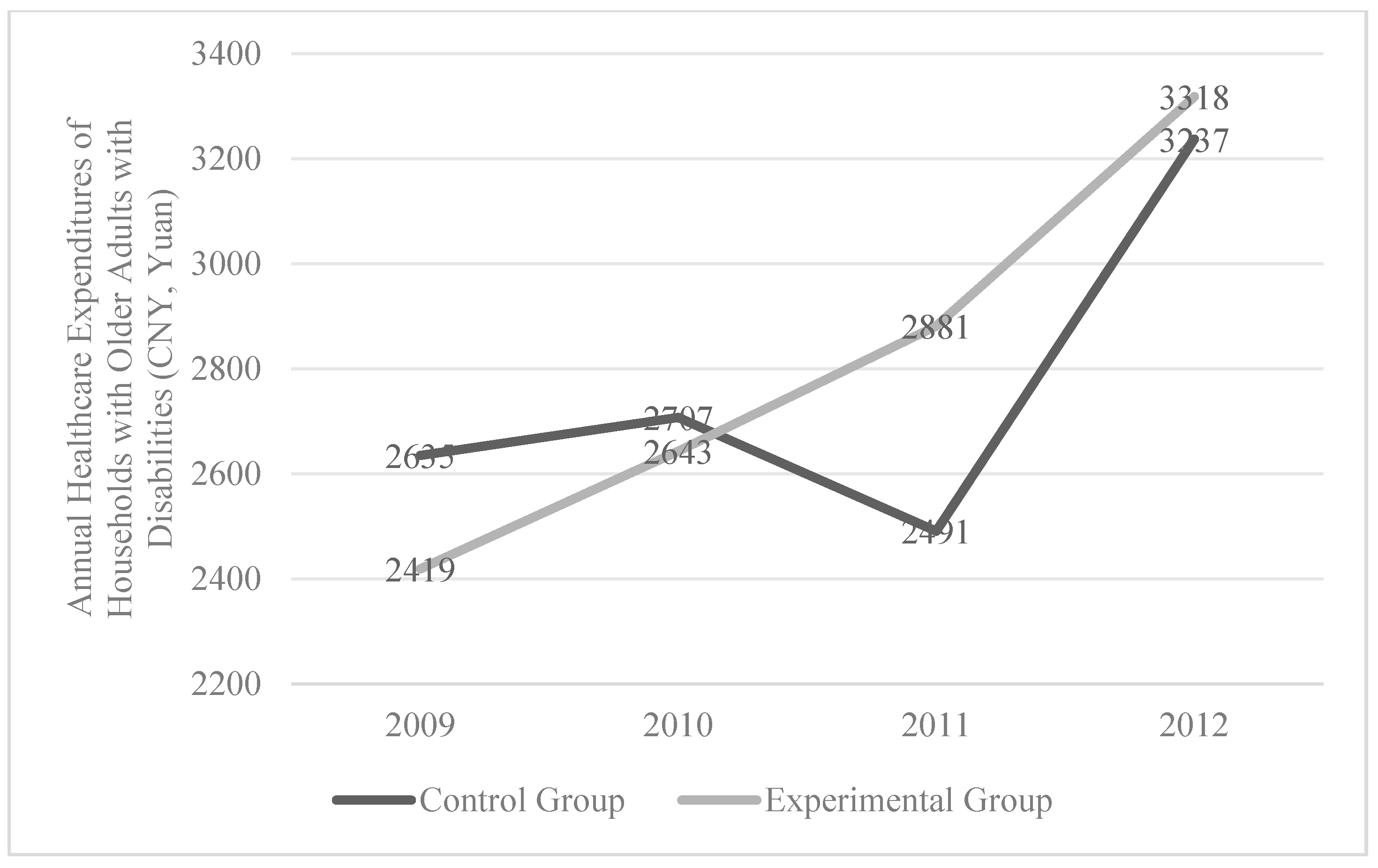

3.3. Annual Healthcare Expenditures for Households with Older Adults with Disabilities in the Experimental and Control Groups, 2009–2012

3.4. Impact of the Rehabilitation Coverage Policy on Annual Household Healthcare Expenditures and the Mediating Effect of Rehabilitation Service Utilization

3.5. Parallel Trend Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effectiveness of the Rehabilitation Coverage Policy in Promoting Rehabilitation Service Utilization Among Older Adults with Disabilities and Structural Differences Across Demographics

4.2. The Effectiveness of the Rehabilitation Coverage Policy in Promoting Household Healthcare Expenditures for Older Adults with Disabilities and Structural Differences Across Demographics

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, Z.; Guo, J.; Li, L.; Liang, P.; Wu, X.; Chen, D.; Sun, H.; Wang, G.; Zheng, J.; Shi, X.; et al. WHO Rehabilitation in Health System: Background, Framework and Approach, Contents and Implementation. Chin. J. Rehabil. Theory Pract. 2020, 26, 16–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Su, B.; Zheng, X. Trends and challenges for population and health during population aging—China, 2015–2050. CCDC Weekly 2021, 3, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, A.; Freeman, R. Western Europe, health systems of. In International Encyclopedia of Public Health; Quah, S.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 408–416. ISBN 978-0-12-803708-9. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, W.; Willer, R. From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. China Releases the Main Data Bulletin of the Second National Sampling Survey of Disabled Persons. 2007. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2007-05/28/content_628517.htm (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hu, H. The impact of Urban Residents’ Medical Insurance on health service utilization—Policy effect and robustness test. J. Zhong Univ. Econ. Law. 2012, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. National Action Plan for Disability Prevention (2021–2025). 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2022/content_5669420.htm (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Gimigliano, F.; Negrini, S. The World Health Organization “Rehabilitation 2030: A call for action”. Eur. J. Phys. Rehab. Med. 2017, 53, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieza, A.; Causey, K.; Kamenov, K.; Hanson, S.W.; Chatterji, S.; Vos, T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; Nakao, H.; Yahata, Y.; Imai, H. In-depth descriptive analysis of trends in prevalence of long-term care in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2008, 8, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, H.; Mikami, Y.; Kuroda, R.; Asaeda, M.; Kawasaki, T.; Kouda, K.; Nishimura, Y.; Ohkawa, H.; Uenishi, H.; Shimokawa, T.; et al. Rehabilitation in the long-term care insurance domain: A scoping review. Health Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijas, V.A.; Hrzic, K.M.; Neculhueque, X.Z.; Sabariego, C. Improving access to and coverage of rehabilitation services through the implementation of rehabilitation in primary health care: A case study from Chile. Health Syst. Reform. 2023, 9, 2242114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Castillo-Laborde, C.; Landry, M.D. Health-related rehabilitation services: Assessing the global supply of and need for human resources. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Skempes, D.; Bickenbach, J. Legal and regulatory approaches to rehabilitation planning: A concise overview of current laws and policies addressing access to rehabilitation in five European countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.; Cieza, A. Strengthening health systems to provide rehabilitation services. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M. Insurance coverage, long-term care utilization, and health outcomes. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2023, 24, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Fattah, R.A.; Susilo, D.; Satrya, A.; Haemmerli, M.; Kosen, S.; Novitasari, D.; Puteri, G.C.; Adawiyah, E.; Hayen, Y.; et al. Determinants of healthcare utilization under the Indonesian national health insurance system: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.Q.; Gao, Y.T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.Y.; Zhou, L.S. Understanding care needs of older adults with disabilities: A scoping review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 18, 2331–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, R.; Blümel, M.; Knieps, F.; Bärnighausen, T. Statutory health insurance in Germany: A health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. Lancet 2017, 390, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachani, A.M.; Bentley, J.A.; Kautsar, H.; Neill, R.; Trujillo, A.J. Suggesting global insights to local challenges: Expanding financing of rehabilitation services in low- and middle-income countries. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1305033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Health financing and integration of urban and rural residents′ basic medical insurance systems in China. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Ning, N.; Gao, L.; Shan, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Perceptions of the benefits of the basic medical insurance system among the insured: A mixed-methods study in a northern city of China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1043153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Fu, H.; Jian, W.; Liu, J.; Pan, J.; Xu, D.; Yang, H.; Zhai, T. Universal health coverage in China part 1: Progress and gaps. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e1025–e1034. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(23)00254-2/fulltext (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Cui, N.; Guo, B.; Zhang, L. Association between health insurance programs and rehabilitation services utilisation among people with disabilities: Evidence from China. Public Health 2024, 232, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Study on Socioeconomic Risk Factors of Severe Mental Disability in Chinese Population. Ph.D. Thesis, Peking University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Guo, C.; Luo, Y.; Wen, X.; Salas, J.I.; Chen, G.; Zheng, X. Trends in rehabilitation services use in Chinese children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities: 2007–2013. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2408–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, X. Relationship Between Utilization Status of Rehabilitation Services and Socioeconomic Position Among the Elderly with Physical Disabilities. Med. Soc. 2023, 36, 6–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 26341-2010; Classification and Grading Criteria of Disability. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2011. Available online: http://files.anshan.gov.cn/files/ueditor/ASSCL/jsp/upload/file/20230815/1692067790671006554.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2011).

- Huang, X.; Yan, T. Rehabilitation Medicine; People’s Health Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. General Rehabilitation Medicine: Theoretical and Clinical Practice Exploration; China Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X. Heckman Two-stage Analysis on the R&D Investment Behavior of Enterprises—An Empirical Study Based on the Panel Data of Chinese Industrial Enterprises. J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 05, 85–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Qiao, H. Impact of the Adjustment of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme on the Utilization of Health Services by Rural Residents. Chin. J. Public Health 2021, 37, 1389–1393. Available online: https://www.zgggws.com/en/article/doi/10.11847/zgggws1128757 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Hu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Medical Insurance’s Impacts on Elders’ Health Service Utilization: Based on the Counterfactual Estimation of the Propensity Score Matching. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2012, 02, 57–66+111–112. Available online: https://zgrkkx.ajcass.com/Magazine/Show/33991 (accessed on 1 April 2012).

- Hu, H.; Luan, W.; Li, J. Medical Insurance, Health Services Utilization and Excessive Demands for Medical Services—The Impact of Medical Insurance on Utilization of Health Service of the Elderly. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2015, 37, 4–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Li, H.; Yang, F. A Scoping Review of the Impact of Medical Insurance Enrollment Location on the Health Service Utilization and Health Status of the Migrants Population in China and Its Countermeasures. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2022, 39, 666–671+720. (In Chinese). Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zgwssygl202209006 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Chen, R.; Zhang, L.; Fang, Y. Effects of urban and rural resident basic medical insurance on healthcare utilization inequality in China. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1605521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Lei, X.; Liu, G. Does medical insurance promote health—Empirical analysis based on basic medical insurance for urban residents in China. Econ. Res. J. 2013, 39, 130–142+156. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Uneven Access to Health Services Drives Life Expectancy Gaps. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/zh/news/item/04-04-2019-uneven-access-to-health-services-drives-life-expectancy-gaps-who (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Hooyman, N.R. Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, H. The Orientation and Significance of Confucian Gender Culture for Women. Open Access Libr. J. 2023, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G. Dilemmas and paths of male participation in family care under the universal two-child policy. J Shenzhen Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 114–122. Available online: https://xb.szu.edu.cn/CN/abstract/abstract578.shtml (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. Socioemotional selectivity theory: The role of perceived endings in human motivation. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Niu, Y. Positivity Effect in Older Adults Occurred in the Late Time Window. In Proceedings of the 90th Anniversary Conference of the Chinese Psychological Society and the 14th National Psychology Academic Conference, Xi’an, China, 21 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meishan News Network. Why Don’t Elderly People Like to Go to the Hospital. 2024. Available online: https://www.mshw.net/wstt/202001/t20200119_469034.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Babik, I.; Gardner, E.S. Factors affecting the perception of disability: A developmental perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 702166. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, V.Y.; Karan, A.; Mahal, A. State health insurance and out-of-pocket health expenditures in Andhra Pradesh, India. Int. J. Health Care Financ. Econ. 2012, 12, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.; Conover, E. Effects of subsidized health insurance on newborn health in a developing country. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2013, 61, 633–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal Lobato, N.; Carpio, M.; Klein, T. IZA DP No. 8213: The Effects of Access to Health Insurance for Informally Employed Individuals in Peru. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2649928 (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Levine, D.; Polimeni, R.; Ramage, I. Insuring health or insuring wealth? An experimental evaluation of health insurance in rural Cambodia. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 119, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P.K. Impacts of insurance expansion on health cost, health access, and health behaviors: Evidence from the medicaid expansion in the US. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2021, 21, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Lu, Z. Health shock, medical insurance and financial asset allocation: Evidence from CHFS in China. Health Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemayehu, Y.K.; Dessie, E.; Medhin, G.; Birhanu, N.; Hotchkiss, D.R.; Teklu, A.M.; Kiros, M. The impact of community-based health insurance on health service utilization and financial risk protection in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, X. The impact of long-term care insurance on household expenditures of the elderly: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X. The poverty prevention effects of health insurance: Evidence from China’s basic medical insurance program. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1576146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ma, X.; Zhan, P. Effects of the Resident Basic Medical Insurance reform on household consumption in China. China World Econ. 2024, 32, 96–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.; Mwale, M.; Qattan, A. Health insurance and out-of-pocket expenditure on health and medicine: Heterogeneities along income. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 638035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X. Rehabilitation service utilization and its associated factors among the elderly with disability in China. Chin. J. Health Policy 2022, 15, 31–39. Available online: http://journal.healthpolicy.cn/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=20220505&flag=1 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Callander, E.J.; Fox, H.; Lindsay, D. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in Australia: Trends, inequalities and the impact on household living standards in a high-income country with a universal health care system. Health Econ. Rev. 2019, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mohanty, I.; Zhai, T.; Chai, P.; Niyonsenga, T. Catastrophic health expenditure and its association with socioeconomic status in China: Evidence from the 2011-2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z. Who took away the dividends of healthcare reform. China Health Insur. 2015, 6, 23–24. (In Chinese). Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zgylbx201506010 (accessed on 26 July 2015).

- Zhou, L. The medical security for disadvantaged groups needs to clarify what the problem is and what the answer is. China Health Insur. 2015, 6, 24–25. (In Chinese). Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zgylbx201506011 (accessed on 26 July 2015).

- Huang, W. Insurance policy and Chinese-style poverty alleviation: Experience, dilemma and path optimization. Manag. World 2019, 35, 135–150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tao, J. Study on Poverty Reduction Effect and Path Optimization of Inclined Medical Insurance Poverty Alleviation Policy. Soc. Secur. Stud. 2020, 4, 10–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| All | |

| Utilization of Rehabilitation Services | |

| No | 41,939 (79.80) |

| Yes | 10,618 (20.20) |

| Existence of Annual Household Healthcare Expenditure | |

| No | 1394 (2.65) |

| Yes | 51,163 (97.35) |

| Annual Household Healthcare Expenditure (CNY, Yuan) * | 2831.15 ± 4472.08 (min: 0; max: 29,600) |

| Treatment | |

| Not affected | 3084 (5.87) |

| Affected | 49,473 (94.13) |

| Post | |

| Before | 25,036 (47.64) |

| After | 27,521 (52.36) |

| Disability Type | |

| Visual disability | 10,814 (20.58) |

| Hearing disability | 18,679 (35.54) |

| Speech disability | 520 (0.99) |

| Physical disability | 13,420 (25.53) |

| Intellectual disability | 904 (1.72) |

| Mental disability | 2287 (4.35) |

| Multiple disability | 5933 (11.29) |

| Disability Degree | |

| Mild | 28,250 (53.75) |

| Moderate to severe | 24,307 (46.25) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 24,832 (47.25) |

| Female | 27,725 (52.75) |

| Age | |

| 60–69 years | 18,525 (36.49) |

| 70 years and above | 32,248 (63.51) |

| Marital Status | |

| Without spouse | 21,239 (40.41) |

| With spouse | 31,318 (59.59) |

| Education Level | |

| Attended school | 26,954 (51.29) |

| Otherwise | 25,603 (48.71) |

| Annual Per Capita Household Income (CNY, Yuan) * | 8475.83 ± 8596.57 (min: 0; max: 145,200) |

| Income Level | |

| Low level | 17,499 (33.30) |

| Middle level | 17,536 (33.37) |

| High level | 17,522 (33.34) |

| Region | |

| East | 20,565 (39.13) |

| Central | 14,830 (28.22) |

| West | 17,162 (32.65) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 37,682 (71.70) |

| Urban | 14,875 (28.30) |

| Group | Utilization Rate of Rehabilitation Services for Older Adults with Disabilities (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Overall Mean | ||

| Overall | Control Group | 12.81 | 18.79 | 13.77 | 27.17 | 18.14 |

| Experimental Group | 13.64 | 18.42 | 18.84 | 29.30 | 20.05 | |

| Male | Control Group | 14.25 | 18.04 | 10.83 | 26.81 | 17.48 |

| Experimental Group | 14.42 | 18.35 | 18.38 | 29.38 | 20.13 | |

| Female | Control Group | 11.64 | 19.38 | 16.25 | 27.58 | 18.71 |

| Experimental Group | 12.95 | 18.48 | 19.25 | 29.22 | 19.98 | |

| Mild Disability | Control Group | 12.38 | 19.30 | 14.29 | 24.84 | 17.70 |

| Experimental Group | 13.78 | 18.55 | 18.85 | 28.34 | 19.88 | |

| Moderate-to-Severe Disability | Control Group | 13.32 | 18.21 | 13.17 | 30.11 | 18.70 |

| Experimental Group | 13.48 | 18.26 | 18.81 | 30.40 | 20.24 | |

| Younger Age Group | Control Group | 13.90 | 17.50 | 11.90 | 28.11 | 17.85 |

| Experimental Group | 15.11 | 18.69 | 18.78 | 29.43 | 20.50 | |

| Middle-Aged and Older Age Group | Control Group | 12.52 | 19.58 | 14.96 | 26.31 | 18.34 |

| Experimental Group | 12.79 | 18.37 | 18.88 | 29.16 | 19.80 | |

| Group. | OR | S.E. | z | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1.349 * | 0.185 | 2.18 | 1.031~1.766 |

| Female | 1.183 | 0.227 | 0.88 | 0.812~1.723 |

| Male | 1.530 * | 0.303 | 2.14 | 1.037~2.256 |

| Younger Age | 1.416 | 0.373 | 1.32 | 0.846~3.372 |

| Older Age | 1.423 * | 0.247 | 2.03 | 1.012~2.000 |

| Mild Disability | 1.444 * | 0.270 | 1.97 | 1.002~2.083 |

| Moderate-to-Severe Disability | 1.241 | 0.253 | 1.06 | 0.833~1.850 |

| Control Variables | Controlled | |||

| Individual Fixed Effects | Controlled | |||

| Time Fixed Effects | Controlled | |||

| Group | Mean Annual Healthcare Expenditures for Households with Older Adults with Disabilities (CNY, Yuan) | Overall Growth Rate (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Overall Mean | |||

| Overall | Control Group | 2635 | 2707 | 2491 | 3237 | 2768 | 22.85 |

| Experimental Group | 2419 | 2643 | 2881 | 3318 | 2815 | 37.16 | |

| Low Income Level | Control Group | 526 | 802 | 627 | 1190 | 786 | 126.24 |

| Experimental Group | 1001 | 1010 | 1174 | 1282 | 1117 | 28.07 | |

| Middle Income Level | Control Group | 1813 | 1618 | 2280 | 2279 | 1998 | 25.70 |

| Experimental Group | 1871 | 2133 | 2262 | 2560 | 2207 | 36.83 | |

| High Income Level | Control Group | 4407 | 4758 | 4024 | 5238 | 4607 | 18.86 |

| Experimental Group | 4481 | 4843 | 5235 | 6185 | 5186 | 38.03 | |

| Estimation Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Variable | S.E. | t | 95% CI | S.E. | t | 95% CI | ||

| All | 0.214 ** | 0.055 | 3.90 | 0.106~0.321 | 0.185 ** | 0.039 | 4.72 | 0.108~0.261 | |

| 1.549 ** | 0.403 | 3.84 | 0.759~2.339 | ||||||

| Low-Income | 0.194 | 0.129 | 1.51 | −0.058~0.446 | 0.141 | 0.086 | 1.65 | −0.026~0.309 | |

| −1.490 * | 0.613 | −2.43 | −2.691~−0.289 | ||||||

| Middle-Income | −0.051 | 0.115 | −0.44 | −0.276~0.175 | 0.156 | 0.084 | 1.85 | −0.009~0.321 | |

| −2.165 | 1.365 | −1.59 | −4.841~0.510 | ||||||

| High-Income | 0.181 * | 0.092 | 1.97 | 0.001~0.361 | 0.137 * | 0.067 | 2.04 | 0.005~0.270 | |

| 0.927 | 1.555 | 0.60 | −2.121~3.974 | ||||||

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled | |||||||

| Individual Fixed Effects | Controlled | Controlled | |||||||

| Time Fixed Effects | Controlled | Controlled | |||||||

| Dependent Variable Coefficient c | Coefficient a | Upper Coefficient c’, Lower Coefficient b | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | S.E. | t | 95% CI | S.E. | t | 95% CI | S.E. | t | 95% CI | |||

| Independent Variable | 0.214 ** | 0.055 | 3.90 | 0.106~ 0.321 | 0.299 * | 0.137 | 2.18 | 0.030~ 0.569 | 0.177 ** | 0.039 | 4.52 | 0.100~ 0.253 |

| Mediator Variable | 0.136 ** | 0.014 | 10.01 | 0.109~ 0.162 | ||||||||

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | |||||||||

| Individual Fixed Effects | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | |||||||||

| Time Fixed Effects | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, S.; Liang, W. The Impact of the “Inclusion of Rehabilitation Services in Basic Medical Insurance” Policy on the Utilization of Rehabilitation Services and Household Healthcare Expenditure Among Older Adults with Disabilities: Evidence from China. Systems 2025, 13, 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090812

Wang Y, Tan L, Zhang X, Yan X, Wang L, Yan C, Zhang Y, Wang T, Wang S, Liang W. The Impact of the “Inclusion of Rehabilitation Services in Basic Medical Insurance” Policy on the Utilization of Rehabilitation Services and Household Healthcare Expenditure Among Older Adults with Disabilities: Evidence from China. Systems. 2025; 13(9):812. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090812

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yiran, Lu Tan, Xiaodong Zhang, Xiaoqian Yan, Le Wang, Chenyu Yan, Yichunzi Zhang, Tianran Wang, Sijiu Wang, and Wannian Liang. 2025. "The Impact of the “Inclusion of Rehabilitation Services in Basic Medical Insurance” Policy on the Utilization of Rehabilitation Services and Household Healthcare Expenditure Among Older Adults with Disabilities: Evidence from China" Systems 13, no. 9: 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090812

APA StyleWang, Y., Tan, L., Zhang, X., Yan, X., Wang, L., Yan, C., Zhang, Y., Wang, T., Wang, S., & Liang, W. (2025). The Impact of the “Inclusion of Rehabilitation Services in Basic Medical Insurance” Policy on the Utilization of Rehabilitation Services and Household Healthcare Expenditure Among Older Adults with Disabilities: Evidence from China. Systems, 13(9), 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090812