Coupling Mechanisms in Digital Transformation Systems: A TOE-Based Multi-Level Study of MNE Subsidiary Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. The Direct Effect of HQ Digital Transformation on Foreign Subsidiaries Performance

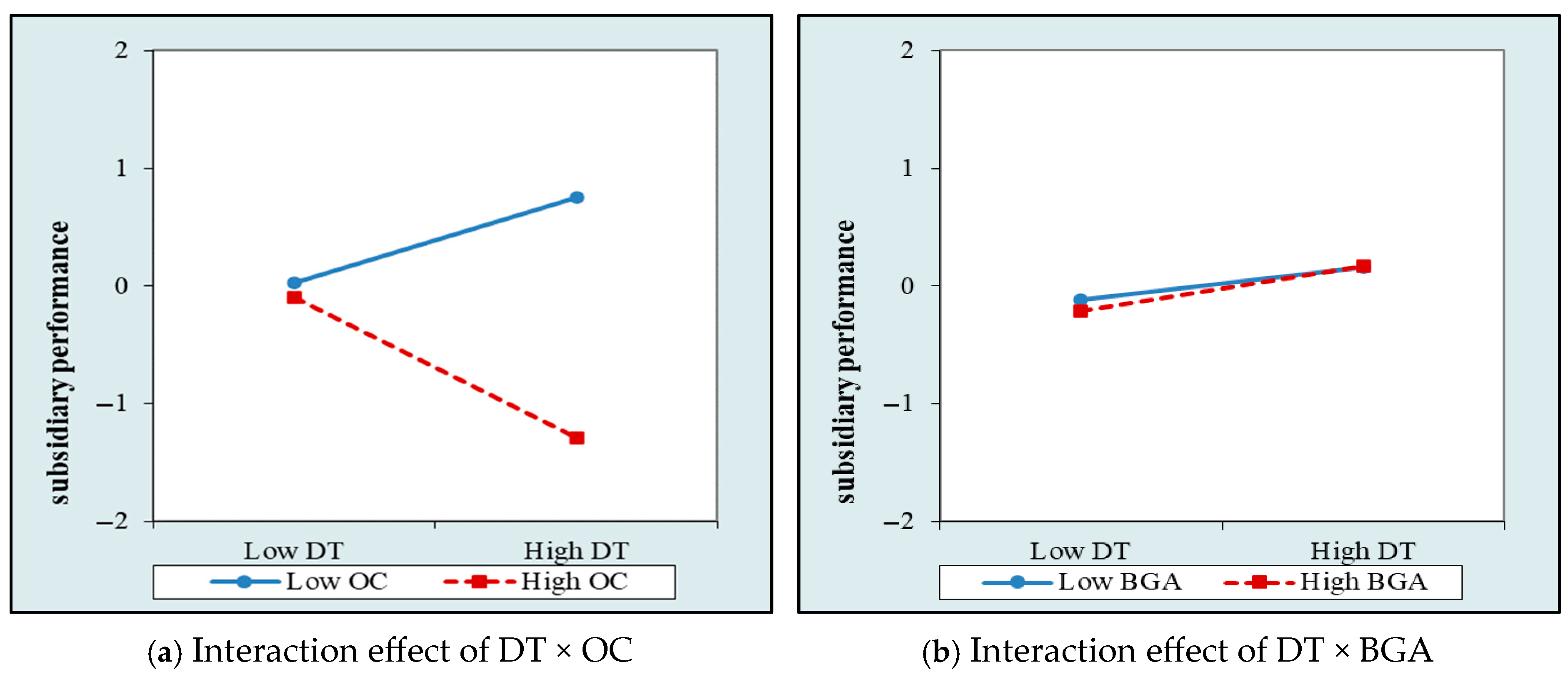

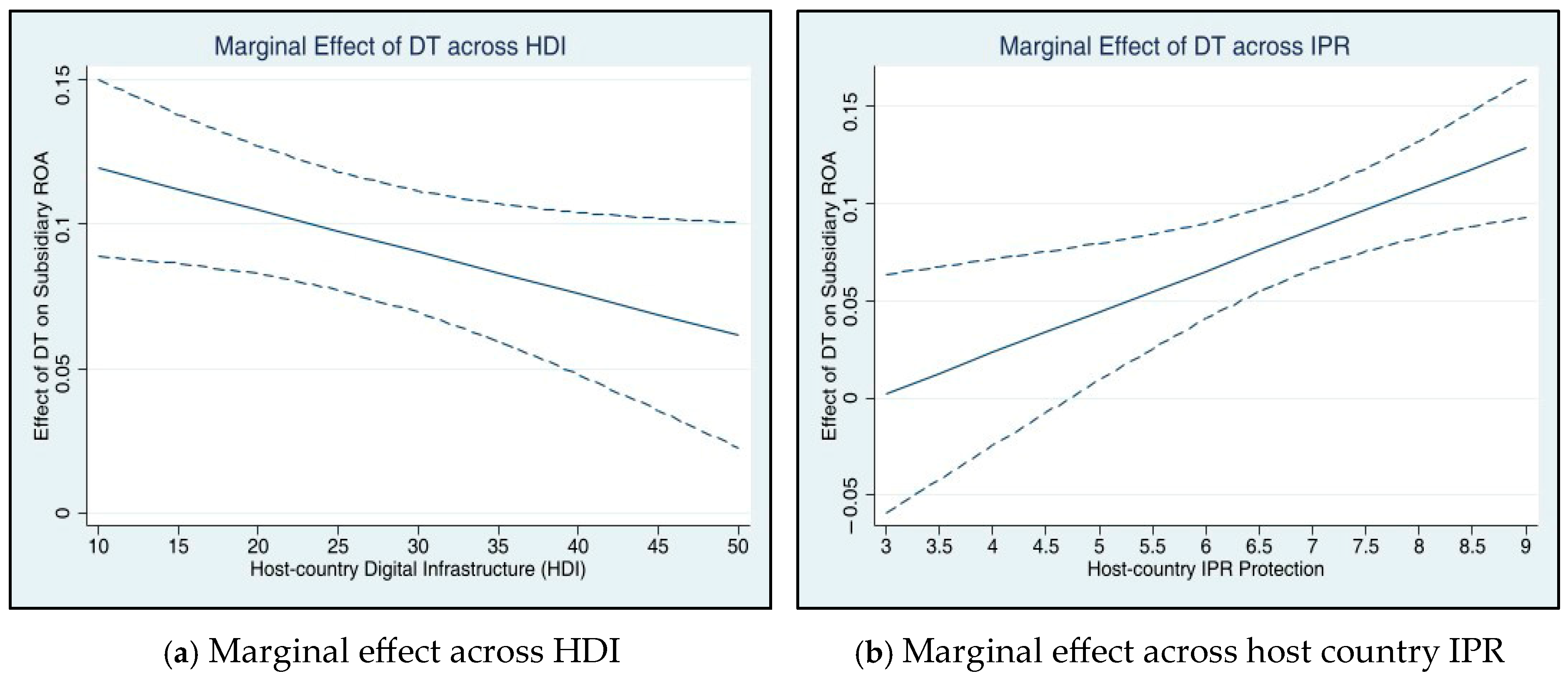

2.2.2. The Moderating Role of Organizational Factors: Over Control and Business Groups

2.2.3. The Moderating Role of Environmental Factors: Host Country Digital Infrastructure (HDI) and IPR

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Moderator Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Regression Model

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis Testing Results

4.2. Robustness Checks

4.3. Endogeneity Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Developed Countries (33) | Developing Countries (43) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Norway | Argentina | Nepal |

| Austria | Poland | Bolivia | Republic of Nigeria |

| Belgium | Portugal | Brazil | Oman |

| Brunei Darussalam | Singapore | Chile | Pakistan |

| Bulgaria | Slovakia | Colombia | Peru |

| Canada | Spain | Republic of (Congo) | Philippines |

| Cyprus | Sweden | Cote d’Ivoire | Romania |

| Czech Republic | Switzerland | Croatia | Russia |

| Denmark | United Arab Emirates | Egypt | Rwanda |

| Finland | United Kingdom | Ethiopia | Saudi Arabia |

| France | United States | Ghana | Senegal |

| Germany | India | Serbia | |

| Hungary | Indonesia | South Africa | |

| Ireland | Iran | Sri Lanka | |

| Israel | Kazakhstan | Thailand | |

| Italy | Kenya | Turkey | |

| Japan | Malaysia | Uganda | |

| Korea, Rep. | Mali | Ukraine | |

| Luxembourg | Mauritania | Vietnam | |

| Malta | Mauritius | Zambia | |

| Netherlands | Mexico | Zimbabwe | |

| New Zealand | Morocco |

| Variable | Measurement | Source (Period) |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | ||

| Subsidiary performance (ROA) | The ratio of net profits divided by the total assets of an MNE subsidiary. | Corporate annual reports (2011–2021) |

| Independent variables: | ||

| HQ Digital Transformation (DT) | The log-transformed frequency count of keywords related to digital transformation (foundational technologies and practical applications) from corporate annual reports, obtained through text analysis. | Corporate annual reports (2011–2021) |

| Moderator variables: | ||

| HQ Overcontrol (OC) | The difference between the ultimate owner’s control rights and cash flow rights. | CSMAR Database (2011–2021) |

| Business Group Affiliation (BGA) | A dummy variable, coded 1 if the company’s ultimate owner is part of a corporate group, and 0 otherwise. | OSIRIS database, company websites, and media reports (2011–2021) |

| Host-country Digital Infrastructure (HDI) | The number of fixed broadband Internet subscribers per 100 people in the host country. | World Bank database (2011–2021) |

| Intellectual Property Rights Protection (IPR) | The International Property Rights Index (IPRI). | Property Rights Alliance (PRA) (2011–2021) |

| Control variables: | ||

| Entry Mode (EM) | A dummy variable; 1 if the parent company owns 100% of the subsidiary (wholly owned), and 0 otherwise (joint venture). | Corporate annual reports, CSMAR Database (2011–2021) |

| Subsidiary’s Age (SAGE) | The number of years from the subsidiary’s establishment to the observation year. | Corporate annual reports, CSMAR Database (2011–2021) |

| HQ’s age (HAGE) | The number of years since the HQ was established | Corporate annual reports (2011–2021) |

| Subsidiary size (SS) | The natural logarithm of the subsidiary’s total assets | Corporate annual reports (2011–2021) |

| HQ’s size (HS) | The natural logarithm of the number of employees in the HQ | Corporate annual reports (2011–2021) |

| HQ’s profitability (HP) | Net income of the HQ | Corporate annual reports (2011–2021) |

| HQ’s debt ratio (HDR) | The ratio of the HQ’s total debt to total assets | CSMAR Database (2011–2021) |

| HQ’s current ratio (HCR) | Current assets divided by current liabilities of the HQ | CSMAR Database (2011–2021) |

| Host country market potential (HMP) | GDP growth rate of the host country | World Bank Database (2011–2021) |

| Formal institutional distance (FID) | Kogut and Singh index based on home–host country institutional differences | World Governance Indicators (WGI) (2011–2021) |

References

- He, Q.; Meadows, M.; Angwin, D.; Gomes, E.; Child, J. Strategic Alliance Research in the Era of Digital Transformation: Perspectives on Future Research. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 589–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Qi Dong, J.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, D.; Arnold, C.; Voigt, K.-I. The Influence of the Industrial Internet of Things on Business Models of Established Manufacturing Companies–A Business Level Perspective. Technovation 2017, 68, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Choi, B.; Jiménez, A. Early Evidence on How Industry 4.0 Reshapes MNEs’ Global Value Chains: The Role of Value Creation versus Value Capturing by Headquarters and Foreign Subsidiaries. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 599–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Dhar, V. Editorial—Big Data, Data Science, and Analytics: The Opportunity and Challenge for IS Research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tung, R.L. A Multipolar Geo-Strategy for International Business. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2025, 56, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Mardani, A. Does Digital Transformation Improve the Firm’s Performance? From the Perspective of Digitalization Paradox and Managerial Myopia. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 163, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Tao, C. Can Digital Transformation Promote Enterprise Performance? —From the Perspective of Public Policy and Innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Knight, G. The Born Global Firm: An Entrepreneurial and Capabilities Perspective on Early and Rapid Internationalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Chang, M.; Zeng, Y. The Influence of Digitalization on SMEs’ OFDI in Emerging Countries. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 177, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciabuschi, F.; Dellestrand, H.; Martín, O.M. Internal Embeddedness, Headquarters Involvement, and Innovation Importance in Multinational Enterprises. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1612–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure. Rochester Studies in Economics and Policy Issues. In Economics Social Institutions; Brunner, K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979; Volume 1, pp. 163–231. ISBN 978-94-009-9259-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, N.; Garicano, L.; Sadun, R.; Reenen, J.V. The Distinct Effects of Information Technology and Communication Technology on Firm Organization. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2859–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Meng, Y.; Feng, B.; Chen, Z. Digital Transformation and the Allocation of Decision-Making Rights within Business Groups–Empirical Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 179, 114715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Rivkin, J.W. Estimating the Performance Effects of Business Groups in Emerging Markets. Strat. Mgmt. J. 2001, 22, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Meng, M.; Li, G. Impact of Digital Finance on the Asset Allocation of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises in China: Mediating Role of Financing Constraints. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konara, P.; Batsakis, G.; Shirodkar, V. “Distance” in Intellectual Property Protection and MNEs’ Foreign Subsidiary Innovation Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2022, 39, 534–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, B.; Niu, T. The Dynamic Effects of Learning: Host Country Experience and International Joint Venture Termination. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.A.; Chowdhury, F.; Hechavarría, D.M.; Muralidharan, E.; Pathak, S.; Lam, Y.T. Digitalization, Institutions and New Venture Internationalization. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goold, M.; Campbell, A.; Alexander, M. Corporate Strategy and Parenting Theory. Long Range Plan. 1998, 31, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, J.D.; Weick, K.E. Loosely Coupled Systems: A Reconceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Xu, G. Headquarters-Subsidiary Relationship and Foreign Subsidiary Innovation in Emerging Multinationals: A Loose Coupling Perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 2024, 64, 1021–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Nell, P.C.; Hoenen, A.K. Understanding Agency Problems in Headquarters-Subsidiary Relationships in Multinational Corporations: A Contextualized Model. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2611–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, B.; Chakravarty, D.; Dau, L.A.; Beamish, P.W. Multinational Enterprise Parent-Subsidiary Governance and Survival. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.-M.; Dahms, S. Ownership Strategy and Foreign Affiliate Performance in Multinational Family Business Groups: A Double-Edged Sword. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Mudambi, R.; Pedersen, T. Subsidiary Power: Loaned or Owned? The Lenses of Agency Theory and Resource Dependence Theory. Glob. Strategy J. 2019, 9, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Parenting Advantage and Equity Control-Performance Relationships: The Asymmetric Effect of Institutional Distance. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2025. ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Goodell, J.W.; Piljak, V.; Vulanovic, M. Subsidiary Financing Choices: The Roles of Institutional Distances from Home Countries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Luo, Y. Toward a Loose Coupling View of Digital Globalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1646–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K.R.; Zámborský, P.; Ranta, M.; Salo, J. Digitalization, Internationalization, and Firm Performance: A Resource-Orchestration Perspective on New OLI Advantages. Int. Bus. Rev. 2023, 32, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Mudambi, R.; Yoo, Y. Digitalization and Globalization in a Turbulent World: Centrifugal and Centripetal Forces. Glob. Strategy J. 2021, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D. Digital Transformation, Sustainability, and Purpose in the Multinational Enterprise. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. New OLI Advantages in Digital Globalization. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.J.; Rocha, Á. Strategic Knowledge Management in the Digital Age: JBR Special Issue Editorial. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, N.; Alessandri, T.; Bart, Y.; Herstein, R. The Impact of Digitalization on Internationalization from an Internalization Theory Lens. Long Range Plann. 2024, 57, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kim, C.; Miceli, K.A. The Emergence of New Knowledge: The Case of zero-reference Patents. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2021, 15, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banalieva, E.R.; Dhanaraj, C. Internalization Theory for the Digital Economy. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Moran, P. Bad for Practice: A Critique of the Transaction Cost Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 13–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-P. Social Control or Bureaucratic Control? -The Effects of the Control Mechanisms on the Subsidiary Performance. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2021, 26, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.; Ning, L.; Beatson, S. Productivity Performance in Chinese Business Groups: The Positive and Negative Impacts of Business Group Affiliation. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2011, 9, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective- on Learning and Innovation. In Strategic Learning in a Knowledge Economy; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-08-051788-9. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Pedersen, T. Transferring Knowledge in MNCs: The Role of Sources of Subsidiary Knowledge and Organizational Context. J. Int. Manag. 2002, 8, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-De-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. Corporate Ownership Around the World. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 471–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.-P.; Schwarz, G.M. A Multilevel Analysis of the Performance Implications of Excess Control in Business Groups. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.H.; Xiao, Z. Abdullah Internal Pyramid Structure, Judicial Efficiency, Firm-Level Governance and Dividend Policy. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 83, 764–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K. Emerging Market Business Groups, Foreign Intermediaries, and Corporate Governance. In Concentrated Corporate Ownership; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; pp. 265–294. [Google Scholar]

- Fuad, M.; Sinha, A.K. Entry-Timing, Business Groups and Early-Mover Advantage within Industry Merger Waves in Emerging Markets: A Study of Indian Firms. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 919–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.R.; Grøgaard, B.; Björkman, I. Navigating MNE Control and Coordination: A Critical Review and Directions for Future Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 1599–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Kai Ming Au, A.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Leveraging Technology-Driven Applications to Promote Sustainability in the Shipping Industry: The Impact of Digitalization on Corporate Social Responsibility. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 176, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.-J.B.; Kim, D.; Lien, Y.-C.; Ro, S. The Moderating Effect of Virtual Integration on Intergenerational Governance and Relationship Performance in International Customer–Supplier Relationships. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020, 37, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Yang, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, D. Business Group Affiliation and Corporate Digital Transformation. Econ. Model. 2025, 147, 107068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changwony, F.K.; Kyiu, A.K. Business Strategies and Corruption in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Impact of Business Group Affiliation, External Auditing, and International Standards Certification. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing Innovation Management Research in a Digital World. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, T.J. Upgrading Strategies for the Digital Economy. Glob. Strategy J. 2021, 11, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital Affordances, Spatial Affordances, and the Genesis of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.E.; Li, J.; Brouthers, K.D.; “Bryan” Jean, R.-J. International Business in the Digital Age: Global Strategies in a World of National Institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, B.; Götz, M.; Tarka, P. Foreign Subsidiaries as Vehicles of Industry 4.0: The Case of Foreign Subsidiaries in a Post-Transition Economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Filatotchev, I.; Gospel, H.; Jackson, G. An Organizational Approach to Comparative Corporate Governance: Costs, Contingencies, and Complementarities. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Li, T.; Liesch, P.W. Performance Shortfalls and Outward Foreign Direct Investment by MNE Subsidiaries: Evidence from China. Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, D.; Little, S. From Imitation to Innovation: The Evolution of R&D Capabilities and Learning Processes in the Indian Pharmaceutical Industry. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 19, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. Conducting R&D in Countries with Weak Intellectual Property Rights Protection. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branstetter, L.; Fisman, R.; Foley, C.F. Do Stronger Intellectual Property Rights Increase International Technology Transfer? Empirical Evidence from U.S.; Firm-Level Data; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; p. w11516. [Google Scholar]

- Papanastassiou, M.; Pearce, R.; Zanfei, A. Changing Perspectives on the Internationalization of R&D and Innovation by Multinational Enterprises: A Review of the Literature. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 623–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N.; Gusenbauer, M.; Hatak, I.; Fink, M.; Meyer, K.E. Innovation Offshoring, Institutional Context and Innovation Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, F.; Yang, Y.; Gaur, A.S. Firm-Specific Intangible Assets and Subsidiary Profitability: The Moderating Role of Distance, Ownership Strategy and Subsidiary Experience. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Ramaswamy, K. An Empirical Examination of the Form of the Relationship Between Multinationality and Performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palich, L.E.; Cardinal, L.B.; Miller, C.C. Curvilinearity in the Diversification-Performance Linkage: An Examination of over Three Decades of Research. Strat. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, C.; Mayer, M.C.J.; Hautz, J.; Matzler, K. International and Product Diversification: Which Strategy Suits Family Managers? Glob. Strategy J. 2018, 8, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Enterprise Digital Transformation and Capital Market Performance: Empirical Evidence from Stock Liquidity. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144+10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, D.W.; Wan, W.P.; Xu, Y. Alternative Governance and Corporate Financial Fraud in Transition Economies: Evidence From China. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 2685–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Oh, C.H.; Lee, J.Y. The Effect of Host Country Internet Infrastructure on Foreign Expansion of Korean MNCs. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2017, 23, 396–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukharskyy, B. A Tale of Two Property Rights: Knowledge, Physical Assets, and Multinational Firm Boundaries. J. Int. Econ. 2020, 122, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirodkar, V.; Konara, P. Institutional Distance and Foreign Subsidiary Performance in Emerging Markets: Moderating Effects of Ownership Strategy and Host-Country Experience. Manag. Int. Rev. 2017, 57, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, S.; Gubbi, S.R.; Kunst, V.E.; Beugelsdijk, S. Business Group Affiliation and Foreign Subsidiary Performance. Glob. Strategy J. 2019, 9, 595–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Li, W.H.; De Sisto, M.; Gu, J. What Types of Top Management Teams’ Experience Matter to the Relationship between Political Hazards and Foreign Subsidiary Performance? J. Int. Manag. 2020, 26, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konara, P.; Shirodkar, V. Regulatory Institutional Distance and MNCs’ Subsidiary Performance: Climbing up Vs. Climbing Down the Institutional Ladder. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Chen, H.; Caskey, D. Local Conditions, Entry Timing, and Foreign Subsidiary Performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Singh, H. The Effect of National Culture on the Choice of Entry Mode. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 19, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, V.; Nieto, M.J. The Effect of the Magnitude and Direction of Institutional Distance on the Choice of International Entry Modes. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, L.; Lu, J.; Lioliou, E. Does Learning at Home and from Abroad Boost the Foreign Subsidiary Performance of Emerging Economy Multinational Enterprises? Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.X.; Ogasavara, M.H. The Impact of Institutional Distance and Experiential Knowledge on the Internationalization Speed of Japanese MNEs. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021, 20, 549–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, J.; Bader, B.; Deller, J. Cross-Border Knowledge Transfer in the Digital Age: The Final Curtain Call for Long-Term International Assignments? J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 61, 1792–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, A.; Fleury, M.T.L.; Oliveira, L.; Leao, P. Going Digital EMNEs: The Role of Digital Maturity Capability. Int. Bus. Rev. 2024, 33, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Vega, H.; Tell, F. Technology Strategy and MNE Subsidiary Upgrading in Emerging Markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 167, 120709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ROA | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 2 DT | 0.102 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 3 HDI | 0.117 *** | 0.066 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 4 IPR | 0.124 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.781 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 5 OC | 0.016 | −0.022 | 0.030 ** | 0.021 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 6 BGA | −0.067 *** | −0.146 *** | −0.134 *** | −0.086 *** | 0.262 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 7 EM | −0.069 *** | 0.021 | 0.115 *** | 0.106 *** | −0.025 * | −0.072 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 8 SAGE | −0.010 | 0.058 *** | 0.034 ** | 0.051 *** | 0.013 | 0.165 *** | 0.063 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 9 HAGE | −0.084 *** | 0.075 *** | −0.033 ** | −0.046 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.211 *** | −0.053 *** | 0.230 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 10 SS | 0.015 | 0.047 *** | 0.023 * | 0.021 | 0.113 *** | 0.148 *** | −0.092 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.169 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 11 HS | 0.008 | 0.039 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.073 *** | 0.118 *** | 0.328 *** | −0.027 ** | 0.179 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.301 *** | 1 | |||||

| 12 HP | 0.029 ** | −0.018 | 0.015 | −0.000 | −0.005 | −0.087 *** | 0.044 *** | −0.146 *** | −0.072 *** | −0.100 *** | 0.019 | 1 | ||||

| 13 HDR | 0.005 | −0.063 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.058 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.303 *** | −0.102 *** | 0.097 *** | 0.147 *** | 0.284 *** | 0.413 *** | −0.364 *** | 1 | |||

| 14 HCR | 0.017 | 0.069 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.086 *** | −0.099 *** | −0.257 *** | 0.073 *** | −0.132 *** | −0.182 *** | −0.226 *** | −0.401 *** | 0.321 *** | −0.779 *** | 1 | ||

| 15 FID | 0.120 *** | −0.028 ** | 0.749 *** | 0.868 *** | 0.016 | −0.036 *** | 0.078 *** | 0.003 | −0.149 *** | 0.004 | −0.060 *** | −0.012 | −0.044 *** | 0.074 *** | 1 | |

| 16 HMP | −0.009 | −0.103 *** | −0.355 *** | −0.230 *** | −0.014 | 0.072 *** | −0.035 *** | −0.065 *** | −0.122 *** | −0.031 ** | 0.028 ** | 0.019 | 0.046 *** | −0.055 *** | −0.151 *** | 1 |

| Mean | 0.74 | 1.23 | 26.86 | 7.14 | 4.08 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 3.2 | 16.76 | 18.01 | 7.94 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 2.24 | 3.8 | 1.85 |

| S.D. | 0.889 | 1.242 | 12.558 | 1.279 | 7.043 | 0.493 | 0.447 | 3.107 | 5.46 | 2.502 | 1.078 | 0.053 | 0.183 | 1.593 | 1.379 | 2.954 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | |||||||

| EM | −0.111 *** | −0.113 *** | −0.114 *** | −0.114 *** | −0.113 *** | −0.114 *** | −0.116 *** |

| (0.029) | (0.028) | (−0.028) | (−0.028) | (−0.028) | −0.028 | (0.028) | |

| SAGE | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (−0.004) | (−0.004 | (−0.004 | (−0.004 | (0.004) | |

| HAGE | −0.066 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.055 *** | −0.054 *** | −0.058 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.052 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (−0.003) | (−0.003) | (−0.003 | (−0.003) | (0.003) | |

| SS | 0.028 * | 0.028 * | 0.030 * | 0.027 * | 0.029 * | 0.027 * | 0.032 ** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (−0.006) | (−0.006) | (−0.006) | (−0.006) | (0.006) | |

| HS | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.007 |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (−0.013) | (−0.013) | (−0.013) | (−0.013) | (0.013) | |

| HP | 0.027 * | 0.037 ** | 0.036 ** | 0.035 ** | 0.036 ** | 0.037 ** | 0.032 ** |

| (0.252) | (0.251) | (−0.25) | (−0.252) | (−0.251) | (−0.251) | (0.251) | |

| HDR | 0.046 * | 0.052 ** | 0.054 ** | 0.061 *** | 0.051 ** | 0.052 ** | 0.061 *** |

| (0.116) | (0.115) | (−0.115) | (−0.115) | (−0.115) | (−0.115) | (0.114) | |

| HCR | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (−0.012) | (−0.012) | (−0.012) | (−0.012) | (0.012) | |

| FID | −0.013 | 0.007 | −0.004 | −0.014 | −0.004 | 0.041 | 0.011 |

| (0.068) | (0.068) | (−0.068) | (−0.068) | (−0.07 | (−0.069) | (0.070) | |

| HMP | 0.050 * | 0.049 * | 0.046 * | 0.049 * | 0.048 * | 0.048 * | 0.045 * |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (−0.008) | (−0.008) | (−0.008) | (−0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Independent variables | |||||||

| DT | 0.130 *** | 0.129 *** | 0.100 *** | 0.133 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.081 *** | |

| (0.010) | (−0.01) | (−0.013) | (−0.01) | (−0.01) | (0.013) | ||

| Moderator variables | |||||||

| OC | −0.009 | 0.001 | |||||

| (−0.002) | (−0.002) | ||||||

| BGA | −0.042 *** | −0.043 *** | |||||

| (−0.028) | (−0.029) | ||||||

| HDI | 0.086 | 0.147 | |||||

| (−0.007) | −0.007) | ||||||

| IPR | −0.096 | −0.069 | |||||

| (−0.064) | (−0.066) | ||||||

| Interactions | |||||||

| DT × OC | −0.055 *** | −0.066 *** | |||||

| (−0.002) | (−0.002) | ||||||

| DT × BGA | 0.042 ** | 0.059 *** | |||||

| (−0.021) | (−0.022) | ||||||

| DT × HDI | −0.024 ** | −0.108 *** | |||||

| (−0.001) | (−0.001) | ||||||

| DT × IPR | 0.036 *** | 0.122 *** | |||||

| (−0.007) | (−0.012) | ||||||

| Model fit | |||||||

| R2 | 0.083 | 0.097 | 0.100 | 0.099 | 0.097 | 0.098 | 0.110 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.067 | 0.081 | 0.083 | 0.083 | 0.081 | 0.082 | 0.092 |

| F-value | 9.464 | 15.325 | 14.406 | 14.486 | 13.948 | 13.192 | 13.326 |

| Obs. | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | |||||||

| EM | −0.111 *** | −0.112 *** | −0.112 *** | −0.113 *** | −0.113 *** | −0.115 *** | −0.115 ** |

| (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| SAGE | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| HAGE | −0.066 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.061 *** | −0.056 *** | −0.054 ** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| SS | 0.028 * | 0.031 ** | 0.032 ** | 0.030 * | 0.033 ** | 0.031 ** | 0.036 * |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| HS | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.010 | 0.008 |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| HP | 0.027 * | 0.034 ** | 0.034 ** | 0.034 ** | 0.033 ** | 0.031 ** | 0.027 * |

| (0.252) | (0.252) | (0.252) | (0.252) | (0.252) | (0.254) | (0.254) | |

| HDR | 0.046 * | 0.051 ** | 0.051 ** | 0.050 ** | 0.054 ** | 0.062 *** | 0.068 ** |

| (0.116) | (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.115) | |

| HCR | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.014 |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| FID | −0.013 | −0.018 | −0.011 | −0.019 | −0.020 | −0.037 | −0.041 |

| (0.068) | (0.068) | (0.069) | (0.068) | (0.068) | (0.068) | (0.069) | |

| HMP | 0.050 * | 0.046 * | 0.042 | 0.048 * | 0.045 * | 0.047 * | 0.040 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Independent variables | |||||||

| DTI | 0.078 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.072 *** | 0.020 | −0.003 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Moderator variables | |||||||

| OC | (0.006) | 0.005 | |||||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | ||||||

| BGA | −0.050 *** | −0.054 *** | |||||

| (0.028) | (0.029) | ||||||

| HDI | 0.084 | 0.077 | |||||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | ||||||

| IPR | (0.103) | (0.110) | |||||

| (0.064) | (0.066) | ||||||

| Interactions | |||||||

| DTI × HDI | −0.047 *** | −0.065 *** | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||

| DTI × IPR | 0.084 *** | 0.100 *** | |||||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | ||||||

| DTI × HDI | −0.024 ** | −0.091 *** | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||

| DTI×IPR | 0.022 * | 0.099 *** | |||||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||||||

| Model fit | |||||||

| R2 | 0.083 | 0.088 | 0.090 | 0.094 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.101 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.067 | 0.072 | 0.073 | 0.077 | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.084 |

| F-value | 9.464 | 11.246 | 10.454 | 12.277 | 10.482 | 9.658 | 11.127 |

| Obs. | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 | 5543.000 |

| Panel A: 2SLS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | First Stage (1) Digital | Second Stage (2) ROA |

| Digital | 0.190 *** (0.023) | |

| IV | 0.801 *** (0.017) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM | 619.80 *** | |

| Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald FCragg–Donald Wald F | 2334.46 *** 1649.94 *** [16.38] | |

| Anderson-Rubin Wald | 74.08 *** | |

| Observations | 5543 | 5543 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Rong, D. Coupling Mechanisms in Digital Transformation Systems: A TOE-Based Multi-Level Study of MNE Subsidiary Performance. Systems 2025, 13, 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090763

Liu L, Wang L, Rong D. Coupling Mechanisms in Digital Transformation Systems: A TOE-Based Multi-Level Study of MNE Subsidiary Performance. Systems. 2025; 13(9):763. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090763

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lu, Lei Wang, and Dan Rong. 2025. "Coupling Mechanisms in Digital Transformation Systems: A TOE-Based Multi-Level Study of MNE Subsidiary Performance" Systems 13, no. 9: 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090763

APA StyleLiu, L., Wang, L., & Rong, D. (2025). Coupling Mechanisms in Digital Transformation Systems: A TOE-Based Multi-Level Study of MNE Subsidiary Performance. Systems, 13(9), 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090763