Abstract

Cybersecurity threats increasingly originate from human actions within organizations, emphasizing the need to understand behavioral factors behind non-compliance with information security policies (ISPs). Despite the presence of formal security policies, insider threats—whether accidental or intentional—remain a major vulnerability. This study addresses the gap in behavioral cybersecurity research by developing an integrated conceptual model that draws upon Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT), Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explore ISP compliance. The research aims to identify key cognitive, motivational, and behavioral factors that shape employees’ intentions and actual compliance with ISPs. The model examines seven independent variables of perceived severity: perceived vulnerability, rewards, punishment, attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, with intention serving as a mediating variable and actual ISP compliance as the outcome. A quantitative approach was used, collecting data via an online survey from 302 employees across the public and private sectors. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with SmartPLS software (v.4.1.1.2) analyzed the complex relationships among variables, testing the proposed model. The findings reveal that perceived severity, punishment, attitude toward behavior, and perceived behavioral control, significantly and positively, influence employees’ intentions to comply with information security policies. Conversely, perceived vulnerability, rewards, and subjective norms do not show a significant effect on compliance intentions. Moreover, the intention to comply strongly predicts actual compliance behavior, thus confirming its key role as a mediator linking cognitive, motivational, and behavioral factors to real security practices. This study offers an original contribution by uniting three well-established theories into a single explanatory model and provides actionable insights for designing effective, psychologically informed interventions to enhance ISP adherence and reduce insider risks.

1. Introduction

Cybersecurity incidents are continually on the rise, putting pressure on organizations to contain such risks. The risks posed by cybersecurity are serious, causing substantial financial loss [1], reputation damage [2], and distrust in work productivity. A report by Verizon [3] indicates that 74% of cybersecurity breaches involve humans. In fact, insider threats are considered to be the biggest concern in the cybersecurity context [4]. An organization may face security incidents due to basic errors, misuse of system privileges and social engineering [3], lack of knowledge [5], and negligence [6]. Moreover, employees with system privileges are the most common threat to organizations [7], making detection and dealing with such threats very sophisticated.

Of course, not all security incidents are caused externally; many of them happen internally, for two reasons. First, there is a lack of knowledge, as employees are not familiar with security policies and procedures, resulting in a limited understanding of what needs to be performed to comply with the information security policy (ISP) and a lack of awareness of the consequences of such actions [8], for example, mistakenly leaking confidential information. Secondly, some employees intentionally bypass security policies and procedures without any motivation to harm the organization’s information resources [9]. This can be attributed to many reasons, such as speeding up the work process. Those actions occur because the employees do not comply with the ISP, which could be a powerful tool to minimize cybersecurity threats, specifically from insiders. Nevertheless, having the most sophisticated security policy is not enough, as a single user’s careless action can cause tremendous damage [10].

While current research lacks sufficient investigation into psychological and behavioral factors that explain employee non-compliance with ISPs [11,12,13,14], particularly when non-compliance occurs unintentionally [14], several studies have applied behavioral lenses to ISP compliance. For example, ref. [15] investigates fear appeals to drive protection motivation; ref. [16] examines self-efficacy and normative influences on compliance behavior in controlled settings, and refs. [17,18] test phishing-avoidance behavior. These efforts focus on intentions or one-off interventions, without addressing how unintentional mistakes and automatic responses drive policy breaches and rarely measure actual user behavior. The majority of current models concentrate on technological controls [19] or general awareness campaigns [20,21], without delivering a comprehensive understanding of the cognitive, motivational, and social factors that influence behavior [22]. The absence of this gap reduces the effectiveness of compliance programs and makes organizations vulnerable to insider threats even when there are formal policies. By fully integrating TPB, PMT, and OCT, our model offers a comprehensive account for both deliberate reasoning and automatic influences on ISP compliance.

Our integrated conceptual model is aimed at explaining employee compliance with ISPs through behavioral analysis. The model draws upon elements from Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT), Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to provide a multi-dimensional view of employee behavior. Each theory highlights a distinct aspect of ISP compliance. First, TPB captures the cognitive-intentional processes by which attitudes, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control shape individuals’ compliance intentions [16,23]. Next, PMT provides a threat assessment lens that shows how, for example, perceived severity and vulnerability generate motivation to protect organizational assets [17,24] while OCT completes these views by explaining how external elements, such as rewards and punishment, reinforce or deter compliance behavior [15,25,26]. By mapping TPB to the formation of compliance intention, PMT to the underlying motivational triggers, and OCT to the impact of consequences on behavior, we ensure that each theory addresses a specific dimension. Whilst integrating three theories adds complexity, we hold that this structured mapping maintains conceptual clarity and avoids overlap. Moreover, this integrated approach reflects established information systems security research. For example, ref. [16] successfully integrates TPB and PMT to explain ISP compliance intentions, and [15] incorporate protection motivation and reinforcement strategies to predict actual behavior. In doing so, they show that multi-theory frameworks provide a more comprehensive explanation of ISP compliance behavior.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information Security Policy Compliance

Various deterrence strategies regarding information security and individuals’ compliance with ISPs have been investigated to deter individuals’ risky behavior. The main emphasis of previous research focused on punishment methods. Research indicates that punishment serves as a deterrence method to achieve employee ISP compliance. The method requires organizations to enforce compliance through strict security policies that restrict individual violations. The solution to ISP violations requires stronger enforcement of ISPs. Ref. [27] proposed the implementation of sanctions as a solution.

Research studies have proposed shaming techniques as a deterrent method to enhance security policy compliance among individuals in order to reduce ISP violations [28]. Ref. [29] conducted a survey to determine the effectiveness of punishment as a deterrent method in UK businesses, despite its legitimacy or illegitimacy. The surveyed organizations revealed that shaming techniques were used by 15% of them and disciplinary action was taken by 42% to prevent human errors. The perceived severity of sanctions plays a role in ISP compliance [30,31]. Ref. [32] showed that security policy violations increase when punishment methods are not used.

The punishment method provides several advantages, yet it produces significant negative consequences and it has been criticized by some as being too harsh. Harris and Furnell [28] argued that the harm caused by shaming could be greater than any potential benefits for future compliance (p. 18). The lack of knowledge among employees [33] can also lead to ISP violations. Therefore, using the punishment approach could damage the relationship between an organization and its employees.

The rewards approach serves as a contrasting strategy to boost individual adherence with ISPs. According to [34], this approach in information systems security (ISS) refers to “tangible or intangible compensation that an organization gives to an individual in return for compliance with the requirements of the ISP” (p. 531). The main objective of this method is to provide rewards that will maintain the individual’s ongoing compliance. Moreover, ref. [34] pointed out that the rewards positively affect individuals’ compliance. The European Union Agency for Network and Information Security recommends using rewards as a motivational factor to ensure individuals’ compliance [7]. Ref. [35] argued that the rewards approach can serve as a control strategy to shape individuals’ behaviors.

Considering the above, there is debate about which approaches are most effective at containing non-compliance. Some researchers argue that the benefits of using the rewards approach as a deterrent can go beyond reducing non-compliance actions by improving individuals’ self-motivation to adhere to ISPs. While there have been few studies on this approach to cybersecurity compliance [32], it has been strongly critiqued by some. Notably, in a systematic literature review, ref. [11] found that, while deterrence methods have an effective impact on containing non-compliance, using the rewards approach as a deterrence method is insignificant in influencing individuals’ behavior. Moreover, others uncovered that financial and/or verbal rewards have a limited impact on individuals’ motivation to comply with the ISP [36].

Some researchers recommend combining the approaches to bring non-compliant individuals into line. For instance, ref. [34] found that sanctions and rewards in combination can help motivate individuals’ ISP adherence. However, despite the benefits of combining approaches, the punishment approach tends to attract organizations’ interest.

Regarding non-compliance, the actions of non-compliant individuals can be categorized into two main types: intentional and unintentional [37]. On the one hand, intentional actions occur when individuals deliberately bypass the security protocol by not complying with the ISP to complete their daily work more quickly or facilitate a security attack. On the other hand, unintentional actions refer to those violating ISPs without intending to do so. Acknowledging the risk of non-compliance, scholarly works have consistently investigated methods aimed at increasing compliance [27,32], with a systematic literature review by [11] emphasizing the need to focus on this aspect. Given the ongoing debate regarding punishment versus reward in ISP compliance, clearly, further investigation is merited.

2.2. Theoretical Background

2.2.1. Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT)

Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT) was founded by Skinner; it has been adopted in many research fields including psychology, marketing, and others. Conditioning is “the strengthening of behavior which results from reinforcement” [25]. Skinner believed behavior is influenced when it is associated with a new stimulus, and argued that behaviors, in general, are significantly changed by consequences, which can be punishers or reinforcers [25]. That is, according to [25], punishment and reinforcement can be either positive or negative. Punishment aims to decrease undesirable behaviors, while reinforcement increases the probability of the desired behavior being performed. Skinner claimed that behavior can be influenced by introducing four types of operant conditioning: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. To demonstrate the power of conditioning behaviors, ref. [25] exemplified this by stating, “If the gambling establishment cannot persuade a patron to turn over money with no return, it may achieve the same effect by returning part of the patron’s money on a variable-ratio schedule” (p. 397). While OCT was first developed and tested on animals in the lab, it has been tested on humans too. In this regard, it has been tested on prisoners’ behavior [38], language learning in humans [39], and human addiction behavior [40].

OCT has received little attention in information systems security literature, yet it could provide new insights by examining the reward-and-punishment approach using conditioning techniques to ensure compliance through new perspectives. In sum, we believe that adding the condition perspective to ISP compliance could help gain new insights and a deeper understanding of the critical phenomenon.

In this study, the “Rewards” variable functions as a proxy for the “Reinforcement” variable, because of the conceptual similarities between these constructs, which researchers have identified in existing ISP compliance studies. Rewards are often implemented as incentives for compliance and are a key form of reinforcement in the context of organizational behavior. Research (e.g., [20,34]) has shown that security policies should be reinforced through rewards, which include recognition incentives and positive feedback, to achieve compliance. Multiple research studies (e.g., [20,34]) have demonstrated that reinforcement strategies that include rewards play a crucial role in achieving security policy compliance. In this study, rewards are defined as organizational reinforcement systems that affect employee policy compliance. The research methodology follows established protocols to validate and ensure the reliability of measurements regarding compliance behavior.

Punishment, here, is defined through a basic framework that treats both positive and negative forms as equivalent. This approach follows previous studies in information security and organizational behavior, which have defined punishment as any consequence that aims to prevent undesirable actions. Refs. [26,41] treated it as a single construct that included sanctions to deter security violations. Ref. [34] highlighted that punishment severity and likelihood act as deterrents but did not specify which types were the most effective. Ref. [42] also supported the idea that both positive and negative punishments reduce non-compliance, justifying their combination into a unified construct. The unified perspective shows how employees usually view all forms of punishment as having negative consequences. Adopting a general approach to punishment enhances the model’s applicability and effectively captures its deterrent effect on ISP violations.

In the extant literature on information systems security and organizational behavior, many studies explicitly combine positive and negative reinforcement and punishment into two single factors: rewards and punishments [26,34,41]. To capture how consequences influence behavior, we followed this established and theoretically supported approach, which emphasizes the functional outcome (i.e., increasing or decreasing behavior), rather than the specific mechanism of stimulus change [43,44]. As noted by [45], distinguishing between positive and negative forms can create conceptual confusion without adding explanatory value. By merging them, we focused on the presence or absence of deterrence or reinforcement, aligning with the core principle of OCT, while maintaining theoretical clarity.

OCT is relevant to this study owing to its strength in explaining behavior through the consequences of actions, utilizing conditioning methods of reward and punishment. Yet, it has its limitations in understanding the human cognitive aspect. For example, ref. [46] argues that intrinsic motivation, defined as an internal drive, considerably impacts human behavior, which is an aspect that is not fully considered by OCT. Therefore, there is a need to extend OCT by adding more variables to capture that important dimension, as obtaining a comprehensive understanding is important. Clearly, people’s cognitive elements heavily influence their compliance decisions. Previous research has emphasized the importance of the cognitive aspect [15,47]. Theoretically, Information Processing Theory (IPT) emphasizes that humans actively process information, formulate judgments, and make decisions based on their interpretation [48,49]. Social Learning Theory (SLT) explains that learning occurs through cognitive processes that enable people to understand and choose actions based on observed behaviors [50]. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) supports this idea by holding that human behavior results from both external reinforcement and observational learning processes [51].

2.2.2. Protection Motivation Theory (PMT)

In the context of compliance with ISPs, the human cognitive aspect refers to evaluating the potential threats if they are not followed [20]. Ref. [34] highlighted that the cognitivist aspect involves how individuals understand security risks and their recognition of the importance of ISPs. In order to capture that important dimension (cognitive aspect), we adopted the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). This is a widely recognized theory utilized in relation to exploring ways to motivate individuals to safeguard themselves against perceived threats. It mainly emphasizes how people evaluate threats and respond via cognitive aspects labeled as threat and coping appraisal. The former has two primary elements: perceived severity and perceived vulnerability [17]. It involves assessing both aspects of a threat, while coping appraisal plays a crucial role within PMT; a cognitive process [24]. This highlights that human cognition influences decision-making and behavior in response to specific situations.

Threat and coping appraisal contribute to the creation of the intention to comply with ISPs. However, an intention to comply does not always ensure actual behavior. Hence, it mediates the relationship between the independent (punishment, perceived vulnerability) and dependent variables (compliance with ISP). Numerous studies have indicated that intention plays a crucial role in determining actual behavior [16,23]

2.2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

Incorporating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [23] in addition to Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT) and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) benefits the current investigation. Behavioral science uses the TPB as one of its most commonly applied models to forecast and analyze human conduct. The model demonstrates strong utility in explaining compliance-related behaviors in relation to the health and environmental responsibility and cybersecurity domains [16,26]. The inclusion of TPB within this study’s conceptual framework enables us to analyze both psychological and social factors that affect employee ISP compliance.

The TPB holds that an individual’s planned action toward a behavior stands as the closest predictor of actual behavioral execution. The three essential factors that determine intention are attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) [23]. The constructs offer a systematic approach to study both what people think about ISP compliance and how social pressure and perceived control affect their actions [16,20,26].

Attitude refers to the extent to which an employee perceives following the organization’s security policy as positive or negative. The outcomes of compliance are perceived by the organization as reduced risk, organizational recognition, or operational efficiency. The model can evaluate employee policy adherence through attitude, which OCT and PMT do not measure fully [16,26,34].

Second, subjective norms represent the perceived social pressure to engage or not in ISP-compliant behavior. The norms in organizational settings are determined by supervisors, coworkers, and organizational culture. An employee may follow the ISP not because of reinforcement or fear of punishment, but rather, because others in the workplace expect it. Subjective norms introduce an essential social element, which extends the individual-oriented PMT framework and the consequence-oriented OCT framework [16,20,26].

Third, PBC is the individual’s perception of their ability to comply with the ISP even when faced with obstacles. It is conceptually similar to self-efficacy in PMT’s coping appraisal [23], but its role in TPB is more comprehensive, encompassing both internal and external control factors (e.g., knowledge, technical barriers, policy clarity). The PMT model fails to capture employee compliance with ISPs, because employees may have good intentions, but struggle to meet requirements owing to unclear instructions or technical barriers or excessive work demands. The addition of PBC helps in better understanding actual compliance behavior [16,20,26].

The integration of TPB enhances the pathway through which cognitive factors influence behavioral results. The model already includes intention to comply with ISPs as a mediating variable. The framework has received empirical support in ISP contexts. For instance, ref. [16] combined TPB and PMT and found that the constructs of the former significantly predicted employees’ intentions to follow security guidelines. Ref. [26] also showed the usefulness of TPB in assessing compliance with security policies, and that attitude and subjective norms are important predictors of behavioral intention.

The TPB model can be integrated with OCT and PMT without any theoretical contradictions. It extends the latter two by examining motivational and normative and control-related cognitions that influence intention formation. Employees base their actions on multiple factors, including their beliefs and the expectations of others as well as their confidence in performing specific behaviors. The addition of TPB enhances both the explanatory capabilities and predictive accuracy of our model.

In sum, to understand the full range of factors influencing ISP compliance, we draw upon the three complementary theories explained above. OCT explains how external consequences (rewards and punishments) shape behavior through reinforcement and deterrence [25]. PMT specifies how threat appraisal (perceived severity and vulnerability) triggers protection motivation [17]. Finally, TPB includes the social cognitive dimension through attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC, which we use to extend PMT’s coping appraisal (self-efficacy and response efficacy), given its empirical and conceptual similarity [23].

In addition, the literature consistently finds no significant positive relationship between perceived response cost (a factor in the coping appraisal component) and intention to comply with ISPs [52,53,54]. Some studies even report that perceived response cost has no influence on ISP compliance [55], which suggests it plays a limited role in the explanatory model. Therefore, excluding PMT’s separate coping appraisal constructs avoids redundancy, prevents overlap, and aligns with established practice [16]. In fact, PMT addresses why employees feel compelled to act (threat appraisal), TPB concerns whether they feel able and socially expected to comply, and OCT pertains to how consequences encourage or discourage compliance.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

2.3.1. The Relationship Between Perceived Severity and Intention to Comply with ISPs

Perceived severity refers to the individual’s belief about the seriousness of the consequences that could result from non-compliance with information security policy. When an individual believes that the outcomes of their non-compliant behavior are severe, they are more likely to be motivated to comply with ISPs [56]. This concept is rooted in PMT, which posits that perceived severity is a key factor that influences intention behavior [17]. In the context of ISP compliance, perceived severity is vital in shaping individual motivation to comply with ISPs [57,58]. In fact, several studies have confirmed the significant positive relationship between perceived severity and individuals’ intention to comply. For example, ref. [20] pointed out that perceived severity significantly influences individual intention to comply with ISPs. In addition, ref. [59] shows that employees’ exposure to serious information security threats leads to a stronger protective action, supporting the role of the perceived severity in shaping intention to comply with ISPs. Recent empirical evidence on the banking sector applying PMT highlights that perceived severity remains a significant predictor of individuals’ intention to comply with ISPs [52]. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Perceived severity positively influences the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.2. The Relationship Between Perceived Vulnerability and Intention to Comply with ISPs

Perceived vulnerability refers to the individual’s belief about the negative outcomes they are likely to experience if they do not follow ISPs. When individuals believe that they could be exposed to potential risk, they are more likely to engage in protective actions [17]. In the context of ISP compliance, the related literature shows that the perceived vulnerability decreases the individual’s intention to perform non-compliant behavior [55,60]. Empirical evidence shows that when individuals believe that their organization is vulnerable to security risk, their intention to protect their information systems increases as well as their ISP compliance [61]. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H2.

Perceived vulnerability positively influences the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.3. The Relationship Between Rewards and Intention to Comply with ISPs

Rewards are an important factor designed to influence individuals’ behavior and encourage them to follow ISP [34,57]. They are often used to reinforce desired behavior by increasing the motivation. Ref. [62] conducted an experimental study to examine the impact of receiving rewards on the employees’ compliance with ISPs and the results showed that these significantly improved compliance behavior. Moreover, a recent systematic review in 2025 focusing on compliance with ISPs analyzed studies published between 2001 and 2023 and found that rewards have a very effective impact on individual behavior toward complying with ISPs [14]. Together, these findings show that rewards can effectively influence individuals’ motivations to adhere to ISPs. Hence, the following is hypothesized:

H3.

Rewards positively influence the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.4. The Relationship Between Punishment and Intention to Comply with ISPs

Punishment is a deterrence mechanism used to influence an individual’s intention to adhere to ISPs. It has been found to be a significant factor in reducing unethical behavior [61]. Previous research has shown that applying real deterrence actions, such as disciplinary measures, can increase fear of consequences, which, therefore, reduces the non-compliant intention behavior toward violating ISPs [35]. Based on the findings of studies [28,32], punishment has been shown to play a significant role in reducing non-compliant behavior. This supports the core assumption of Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT) regarding the critical role of disciplinary consequences in influencing adherence to ISPs. Taken together, the following is hypothesized:

H4.

Punishment positively influences the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.5. The Relationship Between Attitude and Intention to Comply with ISPs

In information security, attitude reflects an individual’s overall evaluation of the importance of complying with an ISP. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), individuals who hold positive attitudes toward a given behavior are more likely to form a strong intention to perform that behavior. Several studies have supported this relationship in the context of ISP compliance [16,20,34]. For example, ref. [14] has identified individuals’ attitudes as a key factor influencing their intention to comply with ISPs. Similarly, ref. [34] surveyed 464 employees and found that favorable attitudes toward ISPs were strongly associated with higher compliance intentions. Ref. [16] found that among 124 managers and IT professionals, those with more positive attitudes toward security policy compliance reported stronger intentions to follow ISPs. This is also consistent with the findings from [20], which showed that in Finland, positive attitudes toward ISPs significantly enhanced the intention to comply. Overall, these findings suggest the importance of attitudes in the ISP compliance. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H5.

Attitudes positively influence the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.6. The Relationship Between Subjective Norms and Intention to Comply with ISPs

According to TPB, subjective norms refer to an individual’s perception of social pressure from colleagues or managers, which positively affects their intentions [23]. In an organizational context, when employees believe that their colleagues and managers expect them to follow security rules, their intention to comply increases [63]. Ref. [64] surveyed 120 employees and found that subjective norms had a direct and positive effect on intentions to perform a secure behavior. In prior studies [16,20,34], subjective norms emerged as a strong predictor of compliance intention. Taken together, we hypothesize the following:

H6.

Subjective norms positively influence the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.7. The Relationship Between Perceived Behavioral Control and Intention to Comply with ISPs

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) has a strong influence on the behavioral intention toward complying with ISPs. In TPB, PBC is a core component that reflects an individual’s belief in their ability to perform the desired behavior [23]. When individuals have the necessary skills to follow ISPs, their intention to comply increases, because they feel capable of preventing potential risks. Prior studies support this relationship and consistently find that higher PBC is associated with stronger compliance intentions [33,51,65]. Thus, it is hypothesized that

H7.

Perceived Behavioral Control positively influences the individual’s intention to comply with an ISP.

2.3.8. The Relationship Between Intention to Comply with ISP and Actual Compliance Behavior with ISPs

According to the ISP compliance literature, intentional behavior is a vital factor that predicts individuals’ actual behavior [11,16,18,23]. Ref. [34] observed a strong relationship between the employees’ intentions to comply with ISPs and their self-reported compliance behaviors. Put differently, when individuals recognize the importance of complying with an ISP, this forms a strong intention that increases the likelihood of actual behavior. Taken together, the following is hypothesized:

H8.

Intention to comply with an ISP positively influences the individual’s actual compliance behavior.

2.4. Conceptual Model

Organizations operating in today’s digital environment are experiencing growing cybersecurity threats, which mostly originate from human factors inside their organizations, rather than external attacks [3]. Information assets face substantial risks to their confidentiality, integrity, and availability, because of insider threats, which include both deliberate and accidental actions [7]. The human factor continues to represent a major security risk, because most data breaches stem from human mistakes and non-adherence to information security policies [1]. The existence of well-structured ISPs does not guarantee consistent employee compliance, which indicates that understanding and influencing human behavior is key to improving organizational cybersecurity.

Drawing on this challenge, in the present study, an integrated conceptual model that combines Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT), Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is proposed. The integrated framework enables a comprehensive analysis of employee compliance behavior with ISPs through behavioral reinforcement mechanisms, cognitive threat perceptions, and motivational–intentional factors.

From the perspective of OCT, employee behavior changes through consequences that include reinforcement and punishment [25]. These mechanisms influence behavior by increasing the likelihood of desirable actions and discouraging non-compliant ones. These external stimuli are effective to some extent, but they do not fully explain why employees choose to comply or not comply with ISPs.

The model includes internal cognitive aspects of compliance behavior through PMT components, which focus on information security threat severity and vulnerability [17]. These variables show how employees cognitively appraise potential threats, which in turn affect their motivation to engage in protective behaviors. Security policies receive higher compliance from employees when they perceive both severe consequences for non-compliance and direct personal risk from such consequences.

However, behavior exists beyond the influence of fear and conditioning alone. The Theory of Planned Behavior [23] offers a motivational perspective that examines how people’s attitudes, their perceptions of social expectations, and their sense of control over their actions influence their behavior. An individual’s assessment of ISP compliance through their attitude toward the behavior indicates whether they view ISP compliance as positive or negative. Subjective norms refer to the perceived expectations of important referent groups, such as supervisors or coworkers, which can significantly influence behavior in organizational settings. Perceived behavioral control pertains to how individuals evaluate their freedom to follow ISPs through their access to resources, their understanding of policy, and their self-assurance in following the policy.

The proposed model uses the intention to follow ISPs as a mediating variable that connects essential predictors to actual compliance behavior. Research based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) has shown that intention serves as a powerful predictor of actual behavior [16,23]. The formation of behavioral intentions occurs through conditioning and cognitive appraisals, yet the actual execution of these intentions depends on the intensity and definition of the intention.

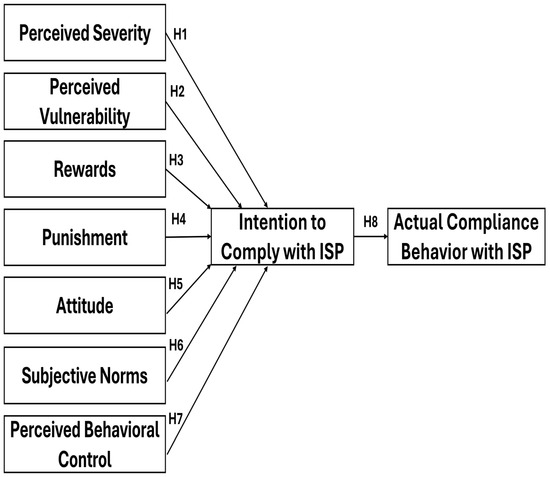

The study uses actual employee compliance with ISPs as its dependent variable, because it shows how well employees follow organizational security standards. Security behavior requires both the execution of established protocols and best practices as well as the reporting of any observed suspicious activities. The research fills an important gap in the existing literature through its development of a complete ISP compliance model, which combines behavioral, cognitive, and motivational perspectives. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The research examines how seven independent factors, including perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, rewards and punishment, attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, affect employee intentions to follow information security policies (ISPs). How employee intentions regarding ISP compliance transform into actual ISP-related behaviors is probed.

The research design used quantitative methods through a questionnaire, which drew from validated measurement tools. An online platform was used to distribute the questionnaire, enabling data collection from various demographic groups. The digital format made participation easier for respondents, which probably led to better response rates and more accurate results. SmartPLS software was utilized to perform data analysis and hypothesis testing through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for studying complex relationships between the study variables. SEM was used because it enables researchers to analyze multiple variables in complex relationships, simultaneously.

3.2. Research Instrument

The research instrument consists of four main sections focusing on different components of the conceptual model. The first gathered personal and demographic information from respondents, including gender, education level, age, job experience, and employment sector. These variables provided essential contextual information to understand how ISPs are followed by employees.

The second section evaluated the seven independent variables of the study. Perceived severity represents how much people think non-compliance would result in severe consequences, and perceived vulnerability shows their belief about encountering information security threats. Rewards and punishment examine respondents’ views on the benefits of compliance and the anticipated severity and likelihood of penalties for non-compliance. The Attitude toward the Behavior Scale evaluates employee perceptions of ISP compliance through their positive or negative reactions to such behavior. Subjective norms evaluate perceived social pressure to comply, and perceived behavioral control assesses individuals’ beliefs about their capability to follow security policies effectively. The instrument used to measure all constructs included multiple items that were adapted from previously validated instruments in the literature to ensure its reliability and validity.

The third section of the questionnaire focuses on the mediating variable—individuals’ intention to comply with ISPs. The section contains items that evaluate the extent to which respondents have developed plans or intentions to execute their organization’s information security policies. The evaluation of intention functions as an essential method to analyze motivational processes that influence behavioral actions, particularly for planned activities, such as ISP compliance.

The final section of the questionnaire assesses the dependent variable, which consists of actual compliance behavior with ISPs. The items in this section measure the extent to which individuals follow their organization’s security policies when performing their duties. The items assess both the rate and reliability of compliance-related actions.

Measurement items from validated sources were used to guarantee both reliability and validity. The perceived severity (PS) items originated from [26], and the perceived vulnerability (PV) items were modified from [57,66]. Items from refs. [20,34] were used to measure rewards (R) and items from [26] to measure punishment (P). The items for attitude (A) were taken from [20,66], and those for subjective norms (SNs) were adapted from [26]. The PBC items stem from [66], while Int was assessed through items from [26,34]. For the assessment of actual compliance behavior with the ISP (Act), items from [20] were utilized. The survey contained 46 items that assessed the independent variables, mediating variables, and dependent variables through a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5) to enable quantitative data analysis. Please see Appendix A for more information about the measurement items.

3.3. Sample and Data Collection

We used a purposive sampling strategy to recruit employees who were expected to comply with their organization’s information security policies. To reach eligible respondents across multiple sectors, the research team contacted organizational members (HR managers, IT/security coordinators, and department heads) from participating organizations and asked them to distribute an online survey link to employees who (a) used organizational information systems and (b) were subject to formal ISPs. The HR managers, IT/security coordinators, and department heads forwarded the invitation by email and through internal work-messaging channels (e.g., WhatsApp groups used for staff communication).

Approximately 500 individuals were invited to participate in the survey. Participation was entirely voluntary, and no financial or material incentives were offered. The motivation to participate likely stemmed from personal or professional interest in cybersecurity and information security policy, as well as collegial support from professional contacts. Out of those contacted, 302 valid responses were received, resulting in an estimated response rate of 60.4%. Ref. [67] states that Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) needs at least 200 cases to produce reliable results. The sample size exceeded the minimum requirement, which supports the validity of the SEM analysis. Although this sampling method supports access to relevant respondents, we acknowledge the potential for self-selection and selection bias. These limitations are addressed in the Section 5 and Section 7 of this study.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

To ensure alignment with standard research ethics, the study followed appropriate ethical procedures during data collection. Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants prior to their participation. The online questionnaire included a dedicated section that clearly explained the study’s purpose, procedures, voluntary nature, data usage, confidentiality assurances, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participants provided consent by selecting an “Agree” option before proceeding; those who declined were redirected away from the survey. All participants were legal adults capable of giving consent without third-party involvement. Data collection took place in May 2025 under the supervision of the principal investigator and co-researchers. All responses were collected anonymously, and no personally identifiable information was requested or stored. Additionally, participants had the opportunity to contact the research team with any questions before providing consent. The study did not involve vulnerable populations and offered no financial or material incentives to ensure voluntariness and neutrality of responses.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

The demographic profile of the study participants reveals a nearly even distribution between genders (53.0% male and 47.0% female). The majority had advanced educational backgrounds, with 37.7% holding a bachelor’s degree. Participants’ ages covered a wide range, with most in 41–50 (30.5%) and 31–40 (28.1%) age groups. Regarding job experience, 44% had 5–10 years, 35.1% more than 10 years, and 20.9% less than 5 years. The sample was also nearly equally split between the private (48.0%) and public (52.0%) sectors. This diversity creates a well-balanced dataset and enhances the validity of studying behaviors influenced by cognitive, behavioral, and motivational factors. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile.

4.2. Measurement Model

The research depended on SmartPLS as its primary software tool to validate the measurement model through Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The SmartPLS framework allows researchers to evaluate the relationships between latent constructs and observed variables by performing factor loading calculations. Items that achieved loadings of 0.70 or higher were maintained, because this threshold demonstrates strong indicator reliability and confirms that each item effectively represents the underlying construct, as recommended by [67]. The final measurement model demonstrated high levels of accuracy, validity, and dependability, which established a solid base for subsequent structural analysis.

The PLS-SEM method allows researchers to analyze reflective and formative constructs, which makes it appropriate for testing hypotheses in complex theoretical models. The PLS-SEM algorithm output shows the factor loadings for most of the items were more than 0.70, with only four items being removed due to low loading.

The standard PLS-SEM guidelines state that items with low loadings function as weak indicators of their respective latent constructs, which can negatively affect both reliability and validity of the measurement model. The removal of these items became necessary to enhance model fit and preserve unidimensional measurement for each construct [68].

In addition to using established items from prior research, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using the PLS-SEM approach in SmartPLS to evaluate the measurement model’s validity and reliability. Convergent validity was assessed through outer loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), all of which met the recommended thresholds. Discriminant validity was confirmed using the HTMT (Heterotrait/Monotrait) ratio, with all values falling below the recommended cutoff of 0.85. Moreover, to evaluate the overall model fit, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), d_ULS, d_G, Chi-square, and Normed Fit Index (NFI) were examined. The SRMR value (0.073) along with other fit indices indicate an acceptable model fit, consistent with guidelines for PLS-based CFA. These steps collectively confirm that the measurement model is statistically robust and theoretically sound.

4.3. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

4.3.1. Convergent Validity

The measurement model validation results in Table 2 confirm the reliability and validity of the constructs used in this study. All constructs achieved acceptable values for Cronbach’s alpha (≥0.70), as recommended by [68,69], indicating strong internal consistency. The measurement items demonstrated reliability given that their composite reliability values surpassed 0.70 for all constructs. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for each construct were above 0.50, thus demonstrating adequate convergent validity.

Table 2.

Measurement Model Validation Summary.

The retained items showed outer loadings above 0.70, which indicates strong relationships between them and their corresponding constructs. All inner VIF values were below the critical value of 3, as recommended by [70,71,72], which indicates no multicollinearity issues among the constructs. The results showed that the measurement model was both statistically sound and theoretically robust and could be used for the subsequent structural model analysis.

4.3.2. Discriminant Validity

The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to assess discriminant validity, as shown in Table 3. The square roots of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct are shown on the diagonal (in bold) and are all greater than the off-diagonal correlations with other constructs. This shows that each construct has more variance in common with its own items than with those of other constructs, thus confirming adequate discriminant validity for all variables in the study.

Table 3.

Discriminant Validity Assessment using the Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

The assessment of discriminant validity appears in Table 4 through the Heterotrait/Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The HTMT values in Table 4 are below 0.85, which demonstrates that each construct maintains its distinctness from others [68].

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity Assessment using the Heterotrait/Monotrait Ratio.

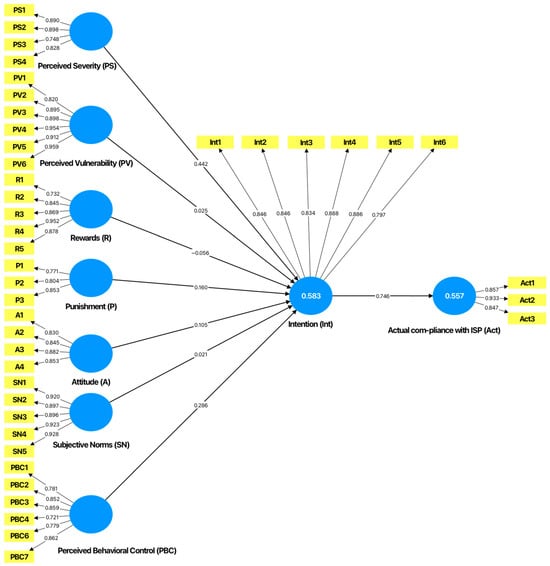

4.4. Structural Model

The structural model results (Figure 2) explain 58.3% of the variance in intention and 55.7% in actual compliance, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating Protection Motivation Theory, Operant Conditioning Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior in explaining ISP compliance behavior within the Saudi organizational context.

Figure 2.

Path Coefficient Results.

Table 5 presents the model fit summary comparing the saturated model and the modified estimated model using key fit indices. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values for both models are below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating an acceptable fit (0.068 for the saturated model and 0.073 for the modified model). The discrepancy measures (d_ULS and d_G) and Chi-square values are slightly higher in the modified model, suggesting a marginal increase in model discrepancy. Additionally, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) shows a minor decrease from 0.817 in the saturated model to 0.812 in the modified model. Overall, while the modified estimated model exhibits a slight decline in fit compared to the saturated model, its values remain within acceptable limits, thus supporting its adequacy.

Table 5.

Fit Summary.

Table 6 presents the results of hypothesis testing for the proposed structural model, highlighting the strength and significance of relationships between the independent variables and the mediating or dependent ones. The key metrics include path coefficients, sample mean (M), standard deviation (STDEV), T-statistics, p-values, and the final decision on whether each hypothesis is supported.

Table 6.

Path Coefficients and Hypothesis Testing Results.

The results indicate that several predictors have a statistically significant impact on the intention to comply with ISPs. Perceived severity (PS) stands out with a high path coefficient of 0.442 and a T-statistic of 8.931 (p < 0.001), thus indicating that employees who perceive serious consequences for non-compliance are more motivated to comply. In contrast, perceived vulnerability (coefficient = 0.025; T = 0.510; p = 0.610), rewards (coefficient = 0.056; T = 1.046; p = 0.296), and subjective norms (coefficient = 0.021; T = 0.532; p = 0.595) did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that employees’ perceived likelihood of being personally affected by a security threat, expectations of rewards, or social pressure may not meaningfully influence their intention to comply in this context. Punishment had a smaller but significant effect (coefficient = 0.160; T = 3.094; p = 0.002), thereby supporting the role of operant conditioning in encouraging policy adherence. Attitude toward ISP compliance showed a significant impact (coefficient = 0.105; T = 2.660; p = 0.008), thus indicating that a more positive attitude contributes to compliance intentions. Similarly, perceived behavioral control had a stronger effect (coefficient = 0.286; T = 4.613; p < 0.001), suggesting that employees who feel confident and capable are more likely to follow security policies.

Finally, the intention to comply with ISPs exhibited a strong and statistically significant relationship with actual compliance behavior (coefficient = 0.746; T = 20.975; p = 0.000), thereby confirming its crucial mediating role. Overall, the findings support most of the proposed hypotheses, particularly those rooted in Protection Motivation Theory (perceived severity), Operant Conditioning Theory (punishment), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (attitude, perceived behavioral control, and intention). However, the non-significant effects of perceived vulnerability, rewards, and subjective norms suggest these factors may be less influential in predicting ISP compliance within this organizational and cultural setting.

The study includes R-square and adjusted R-square values for two essential variables, which are Intention to Comply with information security policies (ISPs) and Actual Compliance Behavior with ISPs, as shown in Table 7. The statistical indicators help in understanding how well the proposed conceptual model, which combines Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT), Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), explains the variability in these two outcomes.

Table 7.

Overview of R-square and R-square Adjusted Values.

The R-square value for the variable Intention to Comply with ISPs stands at 0.583. Hence, the seven independent variables in the model explain 58.3% of the variance in employees’ intention to comply with security policies through their effects on perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, rewards, punishment, attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. The adjusted R-square value is slightly lower at 0.574, thus indicating that after correcting for the number of predictors in the model, 57.4% of the variance remains explained.

The relatively high explanatory power indicates that the integrated model provides a strong framework for understanding the cognitive, motivational, and behavioral factors influencing employees’ intentions to comply with ISPs.

The R-square value for Actual Compliance Behavior with ISP is 0.557 and the adjusted R-square is 0.555. Hence, the model explains 55.7% of the variance in employees’ actual secure behavior. The R-square and adjusted R-square values show a small difference of 0.002, which indicates that the model fits the data well and does not suffer from overfitting or irrelevant predictors.

Overall, the study’s main argument receives support from these values, whereby OCT, PMT, and TPB integration provides a complete and efficient model for understanding both compliance intentions and actual compliance actions.

5. Discussion

For this study, the factors influencing employees’ compliance with information security policies (ISPs) in Saudi Arabia were investigated by integrating factors from the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The research results have revealed which elements most affect employee intentions to follow ISPs and how these intentions affect their actual compliance actions. Each theory contributes distinct conceptual dimensions: PMT emphasizes cognitive threat appraisal, capturing how individuals assess severity and vulnerability; OCT highlights behavioral reinforcement mechanisms, focusing on how rewards and punishments shape compliance through conditioning; and TPB introduces motivational and social cognitive constructs, particularly attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. These constructs do not overlap conceptually, but rather, address different mechanisms that influence compliance behavior, cognitive appraisal (PMT), consequence-based behavior (OCT), and intention formation via beliefs and norms (TPB).

To minimize the risk of conceptual redundancy and multicollinearity, the study carefully mapped constructs to each theory based on established definitions and ensured they remained theoretically distinct. This is further supported by the measurement model’s strong discriminant validity (see Table 3) and acceptable VIF values (see Table 2), which confirm the absence of multicollinearity. Thus, the integration strengthens the model by combining the explanatory power of each framework: PMT explains why individuals feel motivated to protect, OCT explains how consequences shape behavior, and TPB explains how intentions are formed and translated into action. The combination provides a theoretically grounded and empirically testable model that reflects the multifaceted nature of ISP compliance.

The research supports Hypothesis 1 by showing that ISP compliance intention is positively related to perceived severity, thus being in line with previous studies by [20,52,73,74,75,76,77]. Specifically, the findings indicate that Saudi Arabian employees will follow information security policies when they believe non-compliance will result in serious consequences, such as data breaches, disciplinary action, and/or reputational damage. The Saudi context matches this approach, because organizations in Saudi Arabia maintain strict hierarchical structures, and employees fear both disciplinary sanctions and job loss. The emphasis on digital transformation and cybersecurity in Saudi Vision 2030 creates significant pressure on organizations to prevent security breaches. The increased employee awareness of potential harm to both organizations and individuals makes employees perceive harm as being more severe, which drives them to comply.

Hypothesis 2 was not supported, because no meaningful connection between perceived vulnerability and ISP compliance intention emerged. Hence, the research results differ from [16,20,75,77]. The survey results indicate Saudi employees do not perceive themselves as vulnerable to cyber threats, despite their recognition of their severity. The belief that IT departments should handle all security responsibilities might cause employees to feel less responsible for their own protection. Employees may think that their role in cybersecurity is minimal, particularly in larger or government-affiliated organizations, where responsibilities are highly compartmentalized. This detachment reduces the psychological impact of vulnerability on individual behavior. Thus, while employees understand that breaches are harmful, they may not see themselves as likely targets or contributors to those breaches.

Hypothesis 3 was not upheld, because no meaningful connection between rewards and ISP compliance intentions was discovered. The findings of this study are in line with previous work by [20] and differ from [78]. The Saudi work culture demands rule compliance as an organizational duty, rather than an accomplishment. So, employees lack motivation to perform mandatory tasks through external rewards. Moreover, if reward systems are unclear, inconsistently applied, or perceived as insincere, their impact may be minimal. Employees may view information security compliance as part of their job responsibilities, not something to be rewarded. Hence, the cultural and organizational environment reduces the motivational power of rewards as a behavioral control mechanism in cybersecurity.

The research findings support Hypothesis 4 by showing that ISP compliance intention is positively related to punishment, which is in line with the work of [78] and differs from that of [26]. The outcome matches OCT and fits the Saudi Arabian organizational culture, which values discipline. The fear of disciplinary action, including warnings, demotion, and termination, serves as a powerful discouragement for employees to follow the rules. The rules in Saudi organizations, particularly in public institutions and large corporations, are strictly enforced, and employees are expected to follow organizational policies. The fear of facing consequences for violating ISPs plays a major role in determining the willingness to follow rules. This finding shows how formal authority and top–down enforcement can influence behavior.

The research outcomes support Hypothesis 5 by showing that ISP compliance intention is positively related to attitude, which is in line with previous studies by [16,20,34,65,77,79,80,81,82]. Attitude encompasses how employees feel about the usefulness, importance, and personal relevance of ISP compliance. The employees in Saudi Arabia tend to see it as a professional and national requirement, because the country has made progress in digital literacy and cybersecurity awareness through national initiatives (e.g., Vision 2030’s cybersecurity focus). The level of data protection understanding among employees, together with their belief in policy legitimacy, determines their positive attitudes, which leads to stronger compliance intentions.

The study findings failed to validate Hypothesis 6, because no meaningful connection between subjective norms and ISP compliance intention emerged, which differs from [16,65,77,80,83]. This outcome stands in contrast to expectations, most likely because Saudi Arabia operates as a collectivist society, where social norms usually determine how people behave. The practice of information security compliance exists mainly as personal responsibility (e.g., password management and email protocol adherence), which peers cannot easily monitor or enforce. The persuasive power of subjective norms becomes diminished when there is no established culture of peer accountability and no visible role modeling. The study results indicate that organizations need to establish a visible security culture through leadership participation and peer support to maximize the impact of social norms.

The research findings support Hypothesis 7 by showing that ISP compliance intention is positively related with perceived behavioral control, which is in line with previous studies by [16,52,77,84]. The concept of perceived behavioral control refers to whether employees believe they possess the necessary resources, skills, and authority to implement policies. The Saudi context supports employee empowerment through expanded training opportunities and technological adoption at public and private levels, which leads to better compliance intentions among employees who receive sufficient knowledge and organizational backing. The research findings show that organizations should continue their investment in cybersecurity training and awareness programs and user-friendly security systems to boost employee compliance confidence.

Hypothesis 8 is strongly supported by the outcomes, which demonstrates a positive relationship between intention to comply with ISPs and actual compliance behavior. The findings of this study are in line with previous research by [76]. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, intention is the most immediate antecedent of behavior, and this holds true in the Saudi context. Once employees form a strong intention to comply—whether due to perceived severity, attitude, or fear of punishment—they are highly likely to act on that intention. In Saudi Arabia, where compliance with workplace expectations is generally high due to cultural respect for authority and structured management systems, the intention–behavior gap is minimal. This means that initiatives aiming to influence employee intentions (e.g., training, awareness campaigns, leadership communication) can have a direct and measurable impact on actual security behavior.

The results show that, in Saudi Arabia, ISP compliance is driven by perceived severity, punishment, attitude, perceived behavioral control, and intention. On the other hand, perceived vulnerability, rewards, and subjective norms did not have significant influence, most likely due to cultural, organizational, and behavioral dynamics specific to the Saudi context. Organizations need to focus on educational and enforcement strategies that develop intention and confidence, while making non-compliance serious and policies clear and actionable. Policymakers and managers should implement these findings into national cybersecurity initiatives and organizational training programs to enhance overall the compliance culture.

While this study attributes the limited impact of subjective norms and rewards to Saudi Arabia’s collectivist and hierarchical cultural context, we acknowledge that these claims are inferential and not directly measured through cultural assessment tools. The interpretation is grounded in well-established cultural frameworks (e.g., Hofstede’s dimensions) and consistent with prior cybersecurity behavior studies conducted in high-power-distance societies. Although Saudi Arabia’s collectivist culture values group harmony and authority [85,86], the lack of visible peer accountability and leadership involvement in information security may weaken the influence of subjective norms on compliance. Because many security practices are personal and private, organizations must build a strong, culturally aligned security culture with active peer and leadership support to enhance compliance intentions. However, we recognize the absence of qualitative data or direct cultural metrics limits the empirical strength of this explanation. Future research is encouraged to incorporate qualitative interviews, focus groups, or comparative cross-cultural designs to more rigorously explore how cultural attitudes toward authority, compliance, and incentives shape security behavior. Including such methods would enhance the cultural validity and generalizability of findings, particularly when interpreting the role of social norms and motivational drivers across different organizational environments.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The research provides a significant theoretical advancement through its combination of Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT) with Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explain employee compliance with ISPs in Saudi organizations. The results confirm that the TPB framework effectively predicts information security behavior in Saudi Arabia. They demonstrate that actual compliance is heavily influenced by attitude and perceived behavioral control and intention, which confirms that individual cognition plays a crucial role in determining behavior. The perception of ISP compliance as reasonable, important, and within their skillset makes employees more likely to intend to comply and eventually act in accordance with ISP standards. This supports the TPB’s focus on psychological readiness and personal efficacy as factors that influence behavioral outcomes.

The study has benefited from PMT as an additional theoretical framework. The findings show that perceived severity has a substantial impact on compliance intention, but perceived vulnerability does not. The data indicate Saudi Arabian employees respond more to organizational productivity and profitability and data integrity consequences than to abstract risk exposure or personal vulnerability. This outcome refines PMT by indicating that certain cognitive appraisals—especially those linked to organizational outcomes—may carry more weight in collectivist, authority-oriented cultures than in individualist ones.

Furthermore, the study highlights the nuanced role of OCT. While punishment was found to be a significant predictor of compliance intention, rewards did not have a notable impact. This finding has theoretical implications for reinforcement theory, as applied in collectivist societies, like Saudi Arabia. It suggests that negative reinforcement (i.e., avoiding punishment or disciplinary consequences) is a stronger driver of security behavior than positive reinforcement (e.g., rewards, bonuses, recognition). This may be due to cultural factors, such as high power distance and emphasis on rule adherence over individual incentive-seeking behavior. As such, our study findings raise the need for a more context-sensitive understanding of how external motivators interact with internal behavioral intentions.

These theoretical findings align with prior research. For example, ref. [24] found that perceived severity significantly influences compliance, while perceived vulnerability tends to be underestimated. Similarly, ref. [87] showed that punishment is more effective than reward in shaping compliant behavior, especially in rule-oriented environments.

Moreover, the non-significance of subjective norms in shaping compliance intentions challenges one of TPB’s core assumptions. That is, in the Saudi context—where compliance may be seen more as a duty than a socially negotiated behavior—the pressure or opinions of peers or managers may not significantly influence compliance decisions. The current situation requires a review of how security compliance models handle subjective norms in work environments that have strong hierarchical structures or authority-based systems. These theoretical findings align with and extend prior research emphasizing the importance of context in shaping security compliance behavior. For instance, ref. [24] found that perceived severity significantly influences compliance, whereas perceived vulnerability is often underestimated, mirroring our results. Moreover, ref. [87] demonstrated that punishment tends to be a more effective deterrent than rewards, particularly in rule-bound organizational cultures, thus supporting our OCT-related findings.

The non-significance of subjective norms in this study challenges a key assumption of TPB. That is, while TPB suggests that social pressure influences behavioral intention, our findings suggest otherwise in hierarchical, authority-driven contexts, such as Saudi Arabia. This is consistent with the authors of [42], who argued that in high-power-distance cultures, formal authority can override peer influence. Such evidence reinforces the need to contextualize behavioral models like TPB to account for cultural variations.

Additionally, our findings on the predictive role of attitude and perceived behavioral control are consistent with those of [16,20], which found these factors central to compliance across diverse organizational settings. By comparing our results with these prior studies, this research refines existing theoretical frameworks and highlights the importance of culturally tailored approaches to modeling security behavior. Taken together, these insights provide a more culturally grounded extension of PMT, TPB, and OCT by demonstrating which mechanisms translate effectively across contexts, and which require adjustment in high-power-distance, collectivist environments.

6.2. Practical Implications

While the theoretical contributions offer model refinement and cultural insights, the following practical implications provide targeted, actionable strategies grounded in statistically significant findings. This study provides more specific, evidence-based guidance for practitioners and policymakers aiming to improve ISP compliance in Saudi organizations and similar cultural settings. Unlike general recommendations, these practical implications are directly informed by statistically significant findings from the model.

The research findings provide Saudi organizations with practical knowledge to improve their employees’ adherence with ISPs. They reveal that perceived behavioral control together with attitude demonstrates the most significant impact on compliance behavior. The importance of enabling and empowering employees with the skills, resources, and confidence needed to follow ISP guidelines is highlighted. Organizations should prioritize practical training programs that enhance employees’ competence in applying security protocols, using system tools, and interpreting ISP requirements. The process of simplifying policy language together with step-by-step guidance can help non-technical employees to feel more in control of their work.

In addition, this study has provided evidence that organizations should focus on the serious effects of non-compliance on profitability, productivity, and data integrity to achieve better compliance results. Security awareness campaigns should present ISP adherence as a fundamental organizational stability and reputation factor, because perceived severity directly affects intention. Real-world security breaches with their financial or reputational consequences should be used as examples to make these messages more relevant and pressing for employees.

The lack of perceived vulnerability influence shows that fear-based appeals about potential cyberattacks will not be effective in Saudi Arabia unless they are personalized or localized. Security education needs to shift its focus from theoretical threats to demonstrating how compliance impacts both personal job responsibilities and departmental ethical standards and national initiatives, such as Vision 2030, which promotes digital security as a fundamental economic development pillar.

The statistical significance of punishment highlights the need for well-defined disciplinary frameworks to reinforce accountability. These may include structured penalties for repeated non-compliance, formal warnings, and/or restrictions of access. Consistent enforcement reinforces employee accountability and enhances perceived consequences of non-compliance.

However, it is essential that practical recommendations align closely with the study’s empirical results. For example, it was found that rewards did not significantly influence employees’ compliance intentions. While rewards are often suggested in the literature (e.g., 34), in this context, their effect appears to be culturally limited. Therefore, organizations should avoid relying heavily on incentive-based strategies.

The negligible impact of subjective norms suggests that compliance should not rely solely on managerial or peer pressure. Instead, security strategies should align with formal leadership authority, role clarity, and institutional expectations. Leaders should lead by example, but the focus should be on clear, top–down communication and accountability, rather than social persuasion. This indicates that efforts, such as peer-driven awareness campaigns or informal influence strategies, are unlikely to succeed in this context unless tied to formal authority structures. Leadership behavior and institutional enforcement appear to carry greater influence than social norms.

To strengthen practice further, future interventions should emphasize those factors shown to be statistically significant: improving employee attitudes toward ISP through awareness of its value, providing hands-on resources to enhance perceived behavioral control, and creating a visible, fair system of enforcement. These actions are not only supported by this study, but are also echoed in the work of [20,26,30], who found enforcement, empowerment, and risk awareness to be critical behavioral levers. Aligning practice with evidence ensures that compliance programs are both culturally effective and behaviorally sound.

Overall, this study offers Saudi organizations a culturally grounded and evidence-based framework for enhancing ISP compliance by strengthening employee attitudes and behavioral control, enforcing consistent disciplinary measures, and deprioritizing less effective approaches, such as social influence and incentive-based strategies.

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Despite the valuable insights offered by this study, several limitations must be acknowledged, which also provide opportunities for future research. First, the research involved employing a cross-sectional design. Future studies could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to better capture the dynamic evolution of compliance intentions and behaviors over time, especially in response to organizational interventions or cybersecurity incidents.

Second, this study relied entirely on self-reported data collected through online questionnaires, which may be subject to social desirability bias or self-perception inaccuracies. Participants may have overstated their compliance behavior or underreported violations due to fear of judgment, even when anonymity was ensured. Future research needs to include behavioral data, such as system logs, phishing simulation responses, and supervisor evaluations, to validate self-reported behavior and improve the robustness of findings.

Third, the integration of Operant Conditioning Theory (OCT), Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provides a comprehensive framework, but the model does not account for all relevant psychological and contextual variables that may influence ISP compliance. The study did not involve examining individual differences, including personality traits, moral reasoning, risk tolerance, and organizational commitment. Future research should expand upon the model by adding other theories and additional mediating and moderating variables, such as psychological constructs, organizational culture, leadership style, and industry type, as potential moderators.

Fourth, the study’s findings may not be generalizable, because the research was conducted in a specific geographic and cultural setting. The sample consisted of employees from Saudi Arabia, where cultural values may influence how individuals respond to rewards, punishments, and authority-driven policies. As such, these findings may not fully apply to countries with more individualistic cultures. Future research should test the proposed model in diverse cultural settings to validate its cross-cultural applicability and explore how cultural dimensions interact with behavioral drivers of ISP compliance.

In addition, item removal improved model fit, but may have led to overfitting the sample. Future studies should use larger, randomized samples and apply cross-validation techniques to improve generalizability and ensure model stability. Moreover, the study did not account for participants’ industry domains or geographic locations within Saudi Arabia. As the research focused on general employee behavior toward information security policies, the absence of these variables limits the ability to explore potential sector-specific or regional patterns. Future research should incorporate these demographic dimensions to allow for more targeted and context-specific recommendations.

While cultural influence is briefly mentioned in the discussion, future studies should engage more directly with cultural frameworks, such as Hofstede’s dimensions, to assess how cultural orientation moderates behavioral constructs in ISP compliance. Comparative research across nations would help determine whether the results are culture-specific or more broadly applicable. The cultural context of Saudi Arabia, characterized by high power distance and collectivism, may have shaped responses, particularly regarding subjective norms and rewards. These traits can explain the limited effect of social influence, as individuals may respond more to authority than peer norms. This insight should be further explored in future research.

The use of purposive sampling and online recruitment may have introduced self-selection bias, thus limiting representativeness. Future research could employ random sampling to improve external validity. Moreover, for the study, positive and negative forms of punishment were combined into a single construct, and “rewards” were used as a proxy for reinforcement without distinguishing between positive and negative types. While this approach is consistent with prior studies, it may obscure the nuanced effects of specific types of conditioning. Future researchers could disaggregate these constructs and explore whether different combinations of reinforcement and punishment have differential effects on various employee segments.