Abstract

This paper introduces the concept of degenerative affordances to explain how social media can unintentionally destabilise family-run influencer businesses. While affordance theory typically highlights the enabling features of technology, the researchers shift the focus to its unintended, risk-laden consequences, particularly within family enterprises where professional and personal identities are deeply entangled. Drawing on platform capitalism, family business research, and intersectional feminist critiques, the researchers develop a theoretical model to examine how social media affordances contribute to role confusion, privacy breaches, and trust erosion. Using a mixed-methods design, the researchers combine narrative interviews (n = 20) with partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) on survey data (n = 320) from family-based influencers. This study’s findings reveal a high explanatory power (R2 = 0.934) for how digital platforms mediate entrepreneurial legitimacy through interpersonal trust and role dynamics. Notably, trust emerges as a key mediating mechanism linking social media engagement to perceptions of business legitimacy. This paper advances three core contributions: (1) introducing degenerative affordance as a novel extension of affordance theory; (2) unpacking how digitally mediated role confusion and privacy breaches function as internal threats to legitimacy in family businesses; and (3) problematising the epistemic assumptions embedded in entrepreneurial legitimacy itself. This study’s results call for a rethinking of how digital platforms, family roles, and entrepreneurial identities co-constitute each other under the pressures of visibility, intimacy, and algorithmic governance. The paper concludes with implications for influencer labour regulation, platform accountability, and the ethics of digital family entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

Family influencing is a business model that leverages a family’s social media presence to generate income through various streams. This model thrives on the authentic and relatable content that attracts a dedicated audience, opening doors for monetisation [1]. Content includes daily vlogs, parenting advice videos, lifestyle content covering home decor, travel, recipes, and sponsored posts promoting family-relevant products and services. Family influencers generate income through sponsored content, brand partnerships, advertising revenue, merchandising, affiliate marketing, content licensing, subscription models, and public appearances. Family influencers shape trends in parenting, lifestyle, and family entertainment by turning everyday experiences into relatable content. Current examples include The Ace Family, known for their entertaining vlogs (earning USD 32,000 to USD 45,000 monthly), Shaytards (with an annual income of USD 40,000 to USD 652,000), Scary Mommy (with a monthly income of USD 50,000 to USD 138,000), and the Bucket List Family (with a net worth exceeding USD 80 million).

Despite the success of family influencers, there are ethical concerns. Parents using their children to build their wealth and fame raises questions about exploiting children’s work and privacy [1]. Sharing intimate details about children’s mental and physical health and allowing them to participate in sponsored content are just some of the issues. Additionally, legal concerns arise regarding Internet privacy, potential violations of child laws, and even human rights abuses [2]. Additionally, family influencers face a unique conundrum: how much of their private lives should they divulge to their audience? The lines between the private and public spheres are frequently blurred, if not completely muddled. A recent study found that the divorce rates of influencer families rose from 38% in 2020 to 60% in 2023 [3].

Critics argue that some family influencers blur the lines between real life and manufactured content, using their children for personal gain [4]. The privacy and well-being of children participating in this online celebrity culture is a major concern [5]. This controversy underscores the need for ethical and responsible content creation, emphasising the importance of balancing boundaries, authenticity, and the well-being of participants. There are ways to establish boundaries and to prioritise the family’s well-being while maintaining an ethical online presence.

This paper focuses on the parental aspect of the distinctive intersection of the personal and professional spheres in family-owned businesses, offering a rich canvas for examination in the field of commerce. The way that business operations and family ties interact creates a unique set of dynamics that affect business strategies in the digital age. This intersection is especially noticeable in the conception, implementation, and assessment of digital marketing initiatives.

The purpose of this research, therefore, is to examine the long-term viability of this business model. The research aims to answer the following questions:

- Are there unintended consequences that can significantly affect both the personal lives of family members and the business itself?

- How can the family unit and minors be protected from these consequences?

Building on the affordance theory of social media usage to define practices in family businesses and explore the communication, knowledge creation process, and intellectual capital, this paper will apply the concept of “degenerative affordance”, which refers to the potential negative impacts or unintended consequences that arise from the use of social media. This study conceptualises and empirically tests the framework of degenerative affordances in family-run influencer businesses and explores its implications for intra-family trust, role confusion, and legitimacy. The researchers argue that in the context of family influencers and family businesses, these degenerative affordances can have significant adverse effects on all actors.

Framing Degenerative Affordances as Risk

In this study, the researchers define risk as a condition that threatens the continuity, credibility, and cohesion of entrepreneurial activity. Unlike traditional business risks (e.g., market volatility, regulatory uncertainty), the risks that the researchers explore are relational and epistemic—they emerge from within the firm, shaped by how technology reconfigures social interaction and identity.

The researchers conceptualise degenerative affordances as a class of socio-technical risks: unintended outcomes of platform use that degrade rather than enhance organisational functioning. These include the following:

- Reputational Risk: The exposure of sensitive or uncurated content may damage the entrepreneur’s brand.

- Trust Erosion: Public disclosures or algorithm-driven incentives may fracture intra-family trust.

- Role Confusion: Blurred identities (e.g., parent/manager or child/performer) generate emotional and organisational strain.

- Legitimacy Crisis: As family and business roles collapse into one another, stakeholders may question the credibility of the enterprise.

These risks are not simply errors of judgement but are structurally embedded in platform logics, rewarding visibility, virality, and continuous content production over privacy, care, or coherence. As such, degenerative affordances constitute a hidden layer of entrepreneurial vulnerability.

By situating risk within the relational and symbolic domains of entrepreneurial life, this paper expands the risk literature beyond economic rationality to include emotional labour, epistemic injustice, and institutional ambiguity. This framing allows us to reimagine how legitimacy is constructed and contested in digitally mediated family businesses.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Family Business Dynamics and Digital Visibility

Family businesses are distinct from other forms of entrepreneurship in that they involve overlapping systems of kinship, ownership, and management [6]. These enterprises are often governed by long-term socioemotional goals, such as family continuity, reputation preservation, and intergenerational trust [7]. However, this fusion of family and firm also introduces role ambiguity, emotional entanglement, and power asymmetries that complicate strategic and operational decision-making [8].

In the context of social media, these tensions are magnified. Platforms reward visibility, intimacy, and personal narrative, incentivising family businesses, especially influencer-led ones, to transform private life into monetisable content. This adds a layer of performative pressure not typically addressed in the traditional family business literature. Where previous concerns might have centred on succession, governance, or conflict resolution, today’s digital family enterprises must also manage platform algorithms, public scrutiny, and content fatigue.

These dynamics challenge existing models of family business legitimacy, which typically assume alignment between family values and business practices [9]. In influencer settings, this alignment becomes precarious, as platform affordances encourage family members, especially women and children, to commodify their identities in ways that may contradict internal family norms or their long-term well-being.

By situating social media as a structural actor in family enterprise dynamics, this study expands the conversation beyond generational control and strategy to consider how digital infrastructures reshape legitimacy, labour, and trust within entrepreneurial families.

2.2. Affordance Theory and Its Gaps

Affordance theory traditionally focuses on the enabling properties of technology [10,11]. In digital contexts, affordances describe how users perceive and actualise opportunities for action based on platform features. However, existing work is skewed toward positive affordances—enhancing productivity, identity expression, or collaboration. This overlooks the degenerative side of affordances, particularly for users embedded in complex relational ecosystems such as family businesses.

The researchers define degenerative affordances as the unintended, structurally embedded, and often invisible consequences of social media use that undermine trust, role clarity, and emotional well-being within entrepreneurial contexts. Unlike mere platform misuse, these affordances are structurally incentivised by design [12] and play out differently in contexts where personal and professional identities are entwined, such as in family-run influencer businesses.

2.2.1. Platform Capitalism and Influencer Economies

Within platform capitalism [12,13], digital visibility is commodified, and algorithms reward performative intimacy and constant content production. Influencer entrepreneurship, especially within families, relies on this logic. However, monetising family life introduces tensions between authenticity, privacy, and relational boundaries [14,15]. These dynamics create institutionalised pressures for over-disclosure and role confusion, particularly for women and children positioned as both kin and content.

2.2.2. Trust, Role Confusion, and Legitimacy

Trust is foundational in both family business and platform dynamics [16,17];. Yet, digital platforms can erode intra-family trust through public exposure, algorithmic manipulation, and parasocial interactions. When role boundaries blur, e.g., when a mother is simultaneously a parent, entrepreneur, and brand, role confusion increases [18]. Such confusion undermines operational efficiency and challenges the legitimacy of the business in the eyes of both internal and external stakeholders.

2.3. Affordance Theory and the Neglected Shadow of Use

Affordance theory has been instrumental in advancing this study’s understanding of how technologies enable human action. Rooted in [10] ecological psychology and later adapted to sociotechnical systems [11,19], affordances describe the action possibilities that emerge from the relationship between users and artefacts. In organisational contexts, scholars have used affordances to explore how digital technologies support collaboration, knowledge sharing, coordination, and innovation [20,21].

However, the literature overwhelmingly emphasises the enabling dimension of affordances regarding what technologies make possible for work, identity, and productivity. As [11] notes, the focus is often on how users actualise affordances to achieve strategic goals. This positive framing assumes that affordances are neutral possibilities awaiting user activation.

What remains largely unexplored are the negative, unintended, or structurally induced consequences of these action possibilities. In digitally mediated environments, particularly within visibility-driven ecosystems like social media, users may also encounter affordances that produce confusion, emotional strain, or social harm. These are not merely outcomes of misuse but are designed into platforms that reward algorithmic visibility, over-sharing, and boundary erosion.

While much of the affordance literature foregrounds the empowering potential of technology—highlighting transparency, collaboration, and productivity [11,20]—there is growing recognition of its darker implications. Studies such as [22,23] explore how digital affordances can also lead to dependency, surveillance, and identity commodification, especially in visibility-driven environments. However, these discussions often remain at the level of general platform critique and seldom address the relational and emotional dimensions of digital engagement within entrepreneurial or family contexts.

This study responds to that gap by introducing the concept of degenerative affordances, which describes platform features that reward over-disclosure, boundary erosion, and performative visibility—at the cost of emotional well-being, intra-family trust, and entrepreneurial legitimacy. This study approach builds on the critical foundations laid by [12,24], while also aligning with recent empirical work by [25,26] that highlights the unintended consequences of digital labour. Where existing frameworks focus on affordances for empowerment, this study pivots toward the erosive and affective risks inherent in family influencer work, thus extending affordance theory into new emotional and epistemic territory.

This reconceptualisation invites a more balanced and critical affordance perspective: one that acknowledges the co-existence of empowerment and erosion in digital entrepreneurial spaces.

2.4. Degenerative Affordances: Extending Critical Affordance Theory

The concept of degenerative affordances builds upon and extends the growing body of literature on critical and dark affordance theory. Traditionally, affordance theory [10,19] has been used to explore how digital platforms enable specific user actions. More recently, scholars have pushed beyond functional interpretations to include critical affordances, which emphasise how platform design shapes social, political, and emotional consequences [21,27].

This study draws on the work of [24], who introduced the notion of dark affordances to capture unintended or harmful consequences of platform use, such as exploitation, surveillance, and digital overreach. Similarly, refs. [2,12] in critical media and surveillance studies highlight how platform capitalism encourages extractive practices, often cloaked in language of engagement or empowerment, that commodify intimacy, identity, and attention.

The term degenerative affordance is proposed here to extend this discourse by focusing specifically on the relational, emotional, and symbolic risks that arise in family influencer enterprises. Unlike generalised notions of harm (e.g., disinformation, misinformation, or addiction), degenerative affordances refer to platform features that reward visibility, over-disclosure, and performative authenticity, often at the expense of emotional cohesion, intra-family trust, and entrepreneurial legitimacy. These affordances create sustained structural pressures that distort family roles, undermine privacy norms, and erode the boundary between personal life and business performance.

Degenerative affordances thus refer to platform-induced action possibilities that, rather than enabling empowerment or productivity, unintentionally erode the emotional, relational, and symbolic fabric of entrepreneurial life. Unlike dark affordances, which broadly denote harmful or coercive uses of technology, degenerative affordances are structurally embedded and arise specifically within high-affect environments such as family businesses, where personal and professional identities are deeply entwined. These affordances manifest in the form of role confusion, trust erosion, and legitimacy loss, often subtly accumulated through incentivised visibility, over-disclosure, and continuous emotional labour. They are not merely side effects or individual misuses but are co-produced by platform logics and familial dynamics under digital capitalism.

What distinguishes degenerative affordances from adjacent concepts is their specific focus on relational degradation and epistemic erosion within affectively entangled entrepreneurial spaces, namely, family-run influencer businesses. Unlike dark affordances, which highlight coercion or manipulation in general technological contexts, degenerative affordances foreground how platform features systematically disrupt intra-family trust, role coherence, and legitimacy. This concept uniquely captures the slow, structurally embedded erosion of entrepreneurial credibility through repeated acts of over-disclosure, performative authenticity, and algorithm-driven intimacy. It thereby advances affordance theory by shifting the analytical lens from user action possibilities to structurally incentivised emotional labour and symbolic vulnerability in familial contexts. This allows us to theorise social media not merely as a tool but as an institutional actor that co-produces legitimacy risks in digitally mediated family enterprises (refer to Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative definitions table.

Table 1.

Comparative definitions table.

| Concept | Definition | Focus Area | Key Mechanism | Relevance to Family Business |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark Affordances | Unintended harmful outcomes arising from the use of technology [24]. | Surveillance, exploitation, control | Design features misused or subverted | General, not context-specific |

| Algorithmic Harms | Damage caused by opaque or biased algorithmic decision-making [28,29]. | Discrimination, visibility biases | Data extraction, ranking, filtering | Structural, non-relational |

| Emotional Labour | The effort of managing feelings to meet occupational or public expectations [30]. | Performance, affective exhaustion | Repeated self-curation, masking strain | Present, but not tech-induced |

| Degenerative Affordances | Structurally incentivised actions that degrade trust, legitimacy, and role clarity [31]. | Relational erosion, intra-family strain | Platform logics + family entanglements | Core construct |

By theorising degenerative affordances within this context, the study makes a critical contribution to affordance theory, signalling the need to move beyond techno-functionalist and empowerment-focused frames. It offers a lens through which to examine how power, affect, and legitimacy are co-constructed, and at times fractured, by algorithmic and economic pressures in digitally mediated family enterprises.

3. Theoretical Backdrop

Affordance theory was first defined by [10] as the perception of an environment that inevitably leads to some course of action [32]. According to [33], affordance relates to neither the individual nor the environment but the perceived relationship between them, with social media affordance dealing with the hidden possibilities that establish the links between the user and the platform [34]. Drawing on the affordance theory of social media use, the researchers propose the concept of ‘Degenerative’ affordance, which highlights how the design of social media platforms can facilitate harmful behaviours or negative outcomes over time. This concept builds on the broader idea of ‘affordances’, which in social media refers to the possibilities and constraints that platform features offer to users, shaping how they interact with the platform and each other [35,36]. Some of the features of social media platforms enable or constrain specific actions by users, e.g., “Like” buttons, comment sections, sharing options, algorithms, notifications, infinite scrolling, etc. These specific affordances, while facilitating certain types of user engagement, also lead to negative behaviours or harmful outcomes over time [37], for instance, algorithmic prioritisation of sensational content and anonymity that enables trolling, etc. Consequently, these inform user behaviours as actions and interactions of users on social media platforms are influenced by the affordances provided, e.g., content sharing, commenting, liking, following, unfollowing, reporting, etc.

In the context of family businesses, strategic decisions are frequently grounded in socioemotional reference points [38,39,40]. These reference points seek to optimise the family’s affective value by preserving and pursuing socioemotional and economic wealth. According to [39,41], the term “socioemotional wealth” refers to a variety of family-oriented objectives that include satisfying the family’s affective requirements, including identity, family control over the business, and the desire to pass the business on to the next generation. The distinctive characteristics of social media can present family businesses with new avenues for achieving their socioemotional objectives. Technology is considered to offer an “affordance” when people believe that certain qualities can allow them to accomplish particular tasks. According to [11], the affordance perspective refers to the opportunity for action that new technologies allow users, and it is based on the work of ecological psychologist [10] (first published in 1979). The affordance perspective on technology use looks at how people’s objectives align with the tangible aspects of a technology. People who come into contact with an object share its materiality, but how they view the affordances of that technology reflects how they view materiality in general. It is the process of association that enables a connection between the individual and the content, facilitated by the technology. Thus, the affordance perspective on technology asserts that affordances exist in the interactions between people and the materiality of the items that they meet (such as vlogs, wikis, research) rather than only in the possession of people or objects. This suggests that although social media’s features are largely constant, its affordances are socially created and can vary depending on the situation [42,43].

For the purpose of exploring the family influencing business culture, an affordance lens is helpful since it clarifies how, why, and when new technologies like social media impact behaviours [21]. As affordance deals with the hidden possibilities that establish the relationship between the user and the platform, the potential for manipulations increases and remains invisible to the user. Thus, an affordance viewpoint is useful for investigating how socioemotional goals can be achieved by utilising the affordance or chances for action provided by social media. Social media and other technologies that make it possible to fulfil socioemotional goals can be viewed as enabling conditions when viewed through the affordance lens. On the other hand, a ‘degenerative’ affordance lens allows us to explore some key negative aspects of social media use in family business because social media can result in the following:

- (a)

- Reinforce negative behaviour: Social media algorithms prioritise engagement, often amplifying harmful behaviours like trolling or disinformation through visibility-driven feedback loops [44].

- (b)

- Cause polarisation and echo chambers creation: Social media affordances enable echo chambers that reinforce beliefs, increase polarisation, and amplify radical views [37].

- (c)

- Impact on Mental Health: Social media features like likes and endless scrolling foster social comparison, worsening anxiety and depression, especially in youth [45,46].

- (d)

- Cause Exploitation of User Data: Data-driven platforms often exploit user information without consent, enabling manipulative ads and surveillance capitalism [47,48,49].

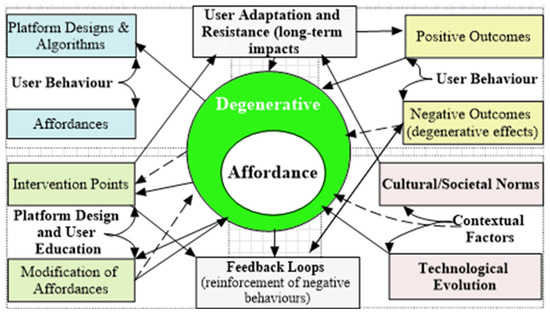

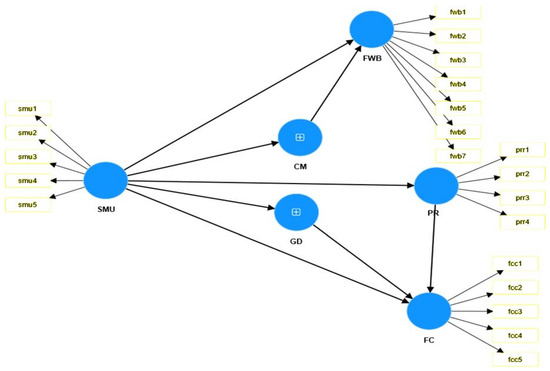

The degenerative affordance perspective argues that features enhancing social media use can, over time, foster harmful behaviours and negative societal outcomes, challenging designers, regulators, and users alike (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for this study. Notes: ⇢ denotes negative relationship (degenerative effect). Source: author.

4. Formulation of Research Hypotheses: Bridging Theory and Empirical Inquiry

4.1. Construct Definitions and Operationalisation

This study organises affordances into interconnected components to conceptualise the degenerative effects of social media in family influencer culture. By incorporating degenerative affordance into hypothesis development, the researchers examine how specific social media features disrupt family and business dynamics. This approach highlights the negative potential of platform interactions and aligns with scholarly frameworks that explore the unintended consequences of technology use.

To explore the dynamics of degenerative affordances, the study focuses on five interrelated constructs (see Table 2) derived from the literature and interview insights:

- (1)

- Social Media Use: Defined as the frequency, intensity, and strategic reliance on social platforms (e.g., Instagram, TikTok, YouTube) for entrepreneurial activities within family businesses. This includes content production, brand building, audience engagement, and monetisation. It is conceptualised as the trigger affordance in the model, initiating both productive and degenerative outcomes.

- (2)

- Role Confusion: This construct captures the blurring of personal and professional boundaries within the family business, particularly as family members—often children or spouses—navigate simultaneous roles as kin, employees, and content subjects. Role confusion reflects emotional and cognitive strain resulting from overlapping, sometimes contradictory, expectations [50]. It is operationalised via items measuring perceived ambiguity and role strain caused by digital visibility.

- (3)

- Privacy Breach: Defined as the involuntary or pressured exposure of personal, familial, or domestic life online—driven not by individual choice alone but by platform incentives that reward emotional intimacy and content frequency. This includes posting sensitive family moments, conflicts, or private routines for public consumption. The construct is measured through items that capture discomfort, regret, and post-disclosure anxiety related to online sharing.

- (4)

- Trust: Refers to intra-family trust, i.e., confidence in the intentions, decisions, and emotional boundaries of other family members involved in the business. Unlike general trust, this construct reflects trust under platform pressure, where family cohesion may be strained by performative or monetised interactions. It is operationalised using adapted items from family business trust scales (e.g., [17]).

- (5)

- Perceived Legitimacy: Captures how the business is viewed as a credible, coherent, and sustainable enterprise by both internal stakeholders (family members) and external audiences (followers, sponsors, institutions). It integrates dimensions of moral legitimacy, pragmatic legitimacy, and emotional coherence [51]. It is measured through items assessing perceived professionalism, alignment of values, and stakeholder confidence.

Table 2.

Framework-to-hypotheses alignment table.

Table 2.

Framework-to-hypotheses alignment table.

| Theoretical Construct | Path Relationship | Associated Hypothesis | Theoretical Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Use | SMU → PPI → Role Confusion | H1 | Platform use blurs boundaries between the’ personal/family and professional roles of family influencers |

| Role Confusion | SMU → Trust Breach → Conflicts | H2 | Role ambiguity undermines emotional security and mutual understanding, which can lead to conflicts among family members |

| Privacy Breach | SMU → Privacy Breach → Trust | H3 | Platform incentives pressure disclosure, damaging privacy and trust |

| Intra-Family Dynamics/ Perceived Legitimacy | Generational Differences → Trust → Professionalism → Legitimacy | H4 | Generational differences in strategy and approach impact trust, which enhances coherence, reputation, and stakeholder confidence in the brand. Role confusion reduces trust, which weakens the perceived business credibility of family influence businesses |

Drawing on affordance theory and the literature on family business, platform capitalism, and digital labour, the researchers propose the following hypotheses:

H1:

The integration of personal and professional identities (PPIs) on social media platforms in family influencer businesses creates role confusion among family members.

Unclear family roles can cause tension and inefficiencies in content creation, marketing, and finances due to miscommunication or overlapping responsibilities. Thus, the researchers propose this hypothesis:

H1a:

Role confusion stemming from social media use (SMU) negatively affects the operational efficiency (OE) of family influencer businesses.

Family involvement on social media blurs identity boundaries, causing tension and privacy issues and affecting decisions that impact overall family well-being. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H1b:

The integration of personal and professional identities (PPIs) in the family influencer business contributes to ambiguity concerning responsibilities and impacts family well-being (FWB).

Role confusion can cause disputes over responsibilities and priorities, straining relationships and negatively impacting both family dynamics and business operations. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H1c:

Role confusion from the integration of personal and professional identities (PPIs) intensifies interpersonal conflicts and puts a strain on family relations (FRs) within family influencer businesses.

This hypothesis suggests that blending personal and professional roles on public platforms may harm both family cohesion and business operations [52]. It calls for deeper investigation into how family influencers navigate the tension between privacy, security, and visibility—crucial for sustaining their business and family well-being. H1 provides a foundation for exploring the unique challenges that family influencers face on social media and underscores the need for strategies to manage associated risks.

4.2. Family Communication Dynamics

Social media platforms primarily support asynchronous communication, where messages are sent and received at different times. Unlike synchronous exchanges, asynchronous communication lacks immediate cues such as tone and body language—critical elements in emotionally nuanced conversations. As [53] argue, such media are considered “lean” and often inadequate for conveying complex emotional content, which is especially important in family relationships.

In family influencer businesses, social media serves as both a public marketing tool and a private communication medium. This dual use can lead to delayed responses, misinterpretations, and blurred boundaries between personal and professional life. Sensitive business matters may be debated publicly without immediate clarification, or personal posts might trigger private conflict—complicating both business operations and family cohesion.

Refs. [54,55] emphasise the emotional depth and relational complexity of family enterprises, where communication often carries implicit meanings shaped by shared history. The asynchronous nature of social media may fail to transmit these subtleties, increasing the risk of misunderstanding and unresolved tension. Furthermore, research shows that family firms often lack formal communication structures [56] relying instead on informal dialogue—something that social media may not support.

As refs. [57,58] note, delayed or ambiguous communication in high-stakes environments can escalate minor issues into significant conflicts, particularly when interpreted as neglect or indifference. This dynamic underscore the risk of using social media as a primary communication channel in emotionally complex business contexts.

Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Social media use (SMU) for family influencer businesses can lead to increased misunderstandings and difficulties in conflict management (CM) among family members.

Social media is central to how family influencer businesses engage audiences while managing overlapping personal and professional roles. However, when misunderstandings occur, the platform’s asynchronous nature can delay conflict resolution and blur identity boundaries. These unresolved tensions risk weakening family relationships and disrupting business functions such as content creation, brand collaborations, and financial coordination. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H2a:

Social media use (SMU) introduces additional layers of complexity to conflict management (CM) within family influencer businesses, complicating the process for family members to effectively address and resolve disputes.

Family members often engage in business-related discussions on social media through fragmented, delayed, or public exchanges. The visibility of these platforms may discourage open conflict resolution, as concerns about reputation and brand image limit candid dialogue. As a result, minor misunderstandings can escalate into serious tensions, disrupting both business operations and family relationships. Over time, this can lead to deeper disputes over strategic decisions and the future direction of the family enterprise. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H2b:

Social media use (SMU) is positively associated with misunderstandings that negatively impact conflict resolution, business performance, and family well-being (FWB).

The absence of non-verbal cues, delayed responses, and the merging of public and private spheres complicate conflict resolution on social media. Disagreements over content or strategy may hinder operational efficiency, as unresolved tensions delay decisions and create misalignment.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) posits that the structure of social media communication can intensify misunderstandings and obstruct conflict resolution in family influencer businesses. Sub-hypotheses H2a and H2b further argue that specific platform features contribute to these challenges. Framed within degenerative affordance theory and supported by the literature on social media and family firms, these hypotheses recognise that digital communication environments demand new approaches to managing interpersonal and strategic tensions. Testing them offers insights into more effective conflict resolution strategies that preserve both family harmony and business performance in influencer-led enterprises.

4.3. Privacy Concerns and Exposure Risks

Social media offers constant visibility that can feel like surveillance, pressuring family influencers to overshare [59]. This visibility-driven architecture, designed to maximise engagement through likes and shares, often blurs boundaries between personal life and business. In family influencer businesses, this creates complex privacy dilemmas, where trust, business continuity, and emotional well-being are at risk [60,61]. Overexposure can lead to data misuse, reputation damage, or legal challenges [62,63]. While social media is often praised for its benefits, growing research highlights its risks—especially for those whose livelihoods depend on sharing private life [64]. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Social media use (SMU) in family influencer businesses is positively associated with privacy invasion (PI) and unintentional disclosure of sensitive information.

While family influencer businesses depend on social media for visibility and engagement, these platforms make it difficult to protect privacy. Family members may unintentionally share sensitive details, increasing the risk of exposure. As content spreads across platforms, the chances of privacy violations grow—especially with a broad audience that may include competitors, critics, or malicious actors. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H3a:

Social media use (SMU) is positively associated with perceived privacy invasion (PPI) in family influencer businesses.

The speed of social media posts allows little time for careful review, leading to unintended disclosures that can harm a business’s reputation, breach privacy, and threaten family safety or business security. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H3b:

Social media use (SMU) in family influencer businesses is positively associated with the unintentional disclosure of sensitive business information in family influencer businesses.

As noted, widespread sharing on social media increases the risk of misinterpretation or misuse of content. For example, a post about a family holiday might unintentionally reveal financial details, attracting unwanted attention. Similarly, the common practice of sharenting—sharing children’s images and stories online—can have unintended consequences, including privacy breaches and long-term digital exposure [65]. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H3c:

Social media use (SMU) is positively associated with exposure to unintended audience and content misinterpretation in family influencer businesses.

By subdividing H3 into H3a, H3b, and H3c, the researchers can examine the many ways in which social media jeopardises privacy, leads to inadvertent disclosures, and facilitates information sharing among family influencer businesses. Testing these hypotheses can provide valuable insights into protective strategies that strike a balance between public engagement and privacy.

4.4. Inter-Generational Disparities in Social Media Use

Research on technological disparity shows that generational differences shape how family members adopt and use social media [66]. Younger ‘digital natives’ are typically more fluent with emerging technologies, favouring bold, trend-driven strategies. In contrast, older generations often prefer traditional methods, approaching social media with caution [66]. These divergent perspectives can lead to strategic misalignment, affecting coordination and brand consistency [67,68].

While such conflicts may hinder operations, they also create opportunities for intergenerational learning. Younger members contribute innovation and digital agility, while older members bring experience and risk awareness [69]. Understanding these dynamics is vital for family influencer businesses, where personal relationships deeply influence strategic decisions. Exploring generational interplay on social media reveals the complexity of family–business integration and offers pathways to optimise digital strategies. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

The use of social media affordances in family influencer businesses is linked to generational differences and can lead to family conflicts (FCs) over social media strategies.

Generational differences in how social media is perceived and used can spark strategic disagreements over the family business’s online image. Younger members may push for frequent, informal posts that showcase personal moments, while older members often prefer more curated, professional content aligned with traditional business values. These differing preferences can create tension around content strategy, posting schedules, and how much personal information is shared publicly. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H4a:

Generational differences influence how social media affordances are perceived within family influencer businesses, with older members prioritising privacy and younger members favouring frequent, open sharing.

Conflicts may arise when younger members promote sharing personal milestones to boost brand relatability, while older members view this as a breach of privacy that invites unwanted scrutiny. Such disagreements can lead to frustration, affecting decision-making and straining overall family and business dynamics. Thus, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H4b:

Generational differences (GDs) in social media use (SMU) and strategy might cause conflict due to divergent views, notably over brand image, personal disclosure, and public participation.

Dividing H4 into H4a and H4b enables a nuanced exploration of how generational differences in social media understanding and use challenge family influencer businesses. Varied approaches to balancing transparency, privacy, and professionalism can lead to internal conflict, affecting both family relationships and the coherence of the brand’s online presence. Understanding these generational perspectives is vital for resolving tensions and developing effective social media strategies. Testing these hypotheses offers deeper insight into the interplay between family dynamics, generational diversity, and digital business performance.

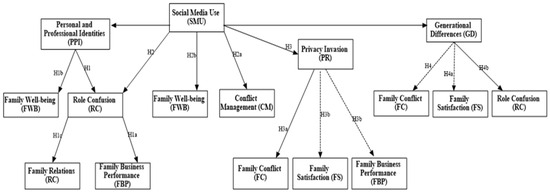

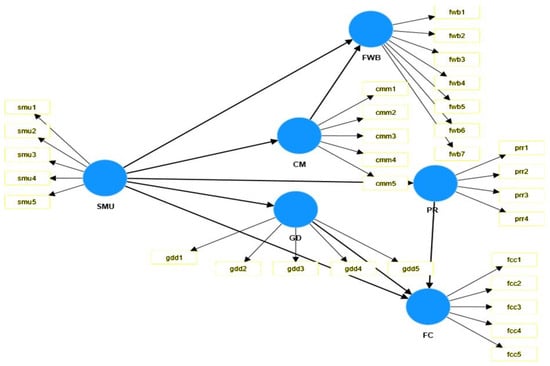

An alignment table linking each element of the framework to hypotheses H1–H4 is given below (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for this study. Notes: ⇢ denotes indirect relationships. Source: author.

5. Materials and Methods

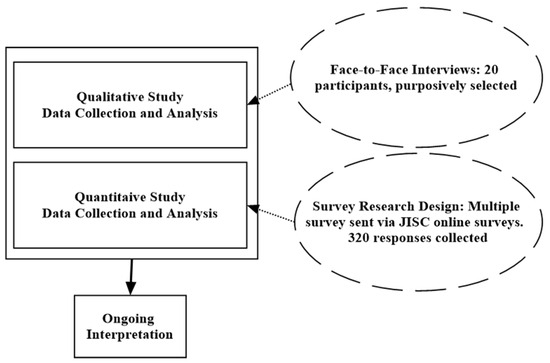

This study adopts an embedded mixed-methods design [70], combining qualitative and quantitative components to both propose and empirically validate a conceptual framework of degenerative affordances in family-run influencer businesses. The qualitative phase, based on 20 narrative interviews, was used to explore how family entrepreneurs experience role confusion, trust erosion, and privacy breaches in everyday digital practice. These insights informed the construction of constructs and guided the development of hypotheses.

The subsequent quantitative phase employed partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) on survey data (n = 320) to test the relationships identified in the conceptual model. This design enables both theory building and preliminary validation by integrating inductive depth and deductive generalisability.

By embedding qualitative insights into a confirmatory model, this approach allows us to move beyond surface-level observations and critically examine how social media affordances shape entrepreneurial legitimacy through relational and epistemic risks.

5.1. Qualitative Analysis Procedure

The qualitative component of this study was analysed using six-phase approach to thematic analysis [71,72]. This method involved data familiarisation, initial code generation, theme identification, theme review, theme definition, and a final write-up. Transcripts were analysed inductively and iteratively to ensure that emergent themes were grounded in participant narratives.

Two coders independently reviewed and coded the interview and open-ended survey transcripts using a structured coding template. Inter-coder reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa, achieving a substantial agreement score of 82%. Disagreements were discussed and resolved through consensus to ensure consistency and rigour in theme development.

The analysis generated six core themes:

- Role Confusion—Ambiguity around family members’ responsibilities in managing digital labour study and boundaries between personal and business life.

- Family Dynamics—Tensions and emotional strain triggered by overlapping familial and entrepreneurial identities.

- Generational Dynamics—Conflicting social media attitudes between younger and older generations, particularly regarding content style, privacy, and branding.

- Privacy and Exposure—Concerns over the unintended disclosure of sensitive personal or business information.

- Visibility and Sharing—Pressures associated with maintaining online presence and audience engagement.

- Communication Challenges—Interpersonal breakdowns caused by blurred lines between work and home communication.

These themes were mapped onto the quantitative SEM constructs—such as trust erosion, privacy invasion, and family well-being—to provide deeper interpretive insight. Illustrative quotes were included in the results and discussion sections to enhance authenticity and demonstrate how social media practices are experienced within family influencer businesses.

5.2. Sampling

For this study, the researchers used an online survey for the quantitative aspects of the research and interviews for the qualitative aspects to obtain direct feedback from the influencers. A convenience sampling strategy was employed for the family influencers due to the exploratory nature of the study and the accessibility of the target population. Convenience sampling offers benefits in initial studies focused on uncovering patterns and insights, rather than prioritising generalisability [73]. The selection of family influencers was determined by their social media platforms, and the survey links were distributed to them through these channels.

The study sampled parent respondents who simultaneously functioned as business owners and social media content creators. These individuals were all actively engaged in managing family influencer businesses, defined as enterprises where family members contribute to the creation, management, and monetisation of digital content. Participants were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling, targeting individuals who operate primarily on platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok. Although all respondents were parents, the researchers did not control for variables such as age, number of children, or household income, as the primary focus was on social media use and its effects on family dynamics and business performance.

5.3. Data Collection

The online survey was a structured questionnaire conducted between June and July 2024 via social media platforms, enhancing accessibility for respondents [74]. A pilot study was conducted with 30 family influencer businesses to evaluate the clarity and validity of the survey [75]. Adjustments were made based on feedback to improve the validity of the questionnaire. The validity of the survey underwent expert review, while its reliability was confirmed through Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.84), indicating a high level of internal consistency [76]. Data were collected qualitatively via semi-structured interviews with 20 family influencers, carried out concurrently from June to July 2024. The interviews conducted via telephone and Zoom yielded comprehensive insights into the social-media-related challenges affecting family businesses. Interviews were transcribed for the purpose of thematic analysis (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Embedded mixed methods (EMM) employed in this study. Source: authors.

6. Results

The findings are organised around the research questions and the central themes that emerged from the data, which include, i.e., role confusion; impact on family dynamics; privacy concerns and risk of exposure; generational differences in adoption and the tension that this can generate within the family; and communication challenges. In the discussion, each theme is illustrated with excerpts from the interviews as well as the surveys to provide rich, contextualised insights into the participants’ lived experiences. For clarity, these themes are discussed with a focus on the RQs in the following sections.

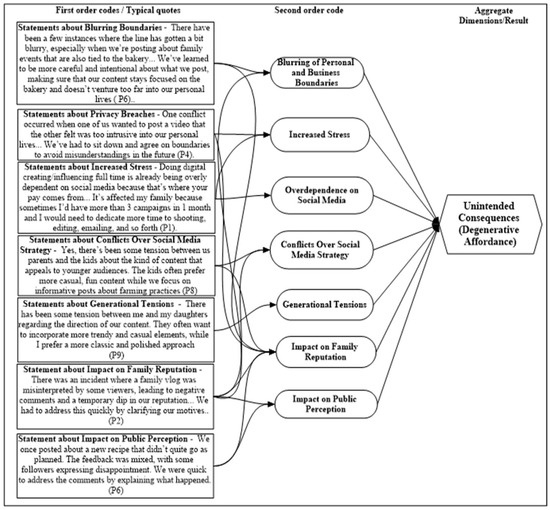

6.1. Unintended Consequences on Personal Lives and Business Operations (RQ1)

The use of social media in family influencer businesses has led to a range of unintended consequences that affect both personal relationships and business operations. This discussion explores these outcomes, supported by participant quotes that illustrate the challenges that families face when blending personal and professional identities online. All participants (100%) reported boundary management issues, primarily driven by role confusion (90%), while 40% also identified role overlap as a recurring challenge (see Table 3).

Table 3.

References for unintended consequences.

Additional themes influencing unintended consequences in family influencer businesses included boundary management (27 references), role overlap (17), interpersonal relationships (11), work–life balance (23), conflicts over social media strategy (21), technology adoption challenges (14), information management difficulties (20), and privacy concerns (21). Many participants reported feeling stressed (25) or overwhelmed (18) by the constant demands of content creation, often at the expense of other business tasks or personal well-being. This over-reliance on social media to sustain operations negatively affected both family dynamics and business performance. Several participants noted that the pressure to remain visible online disrupted personal relationships and compromised operational quality (Appendix D—for illustrative quotes).

Generational differences in social media attitudes caused tension, with older members prioritising privacy and younger ones favouring trendy, engaging content (19–22 references). These dynamics stressed content decisions and brand identity [77] and, in some cases, led to reputational harm (17 references). The public nature of social media made families vulnerable to criticism when sharing personal or sensitive material. Data were analysed using [78,79,80].

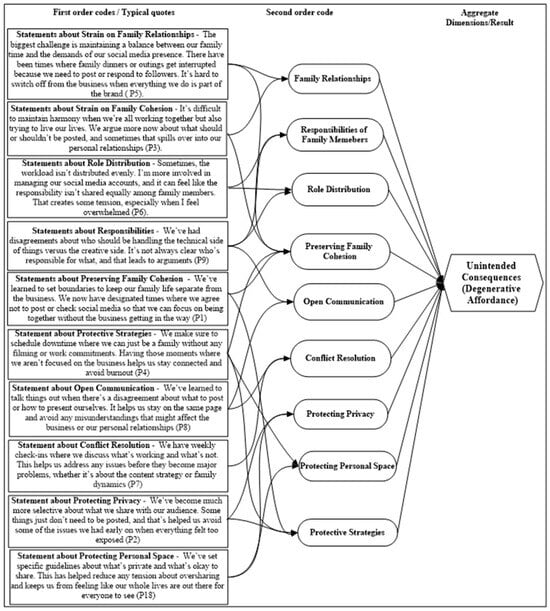

6.2. Effect on Family Cohesion and Safeguarding the Family Unit (RQ2)

This section will examine the effects on family cohesiveness and the measures that families use to mitigate these adverse outcomes, substantiated by quotations from the data, thereby addressing RQ2 (see Table 4 for codes and references).

Table 4.

References for family cohesion.

Table 4 highlights how managing both personal and professional content on social media creates tension within family influencer businesses. Disputes over roles, boundaries, and privacy often lead to conflict, with business priorities increasingly overshadowing personal relationships. Participants frequently reported that merging personal and business lives on the same platform disrupted family cohesion, as social media began to dominate over quality family time—resulting in frustration and disconnection. Role ambiguity and disagreements over responsibilities further intensified internal tensions, weakening family unity (see Table 3).

Other challenges to maintaining family relations and cohesion mentioned in the data include (a) the need for safeguarding and protecting family members, especially minors, from the negative consequences of social media; (b) strategies for protecting the family; (c) communication challenges; (d) conflict resolution; and (e) open communication (see —Appendix E—for quotes).

6.3. Hypothesis Testing

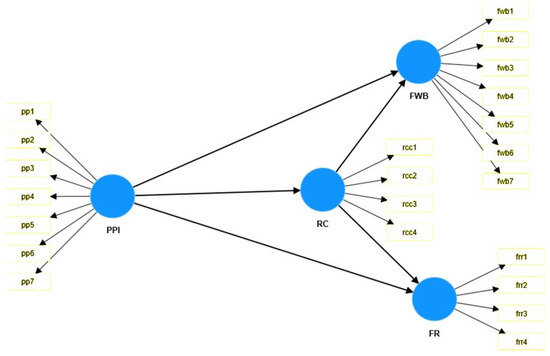

Following the indices concerning the measurement model, Table 1 and Table 2 are used to evaluate the model’s acceptability. First, Table 1 assesses the items’ loadings, internal consistency, and convergent validity of the constructs. Based on the literature [81], item loadings ≥ 0.7 are acceptable unless the inclusion of values between 0.4 and 0.7 will not invalidate the overall reliability of the constructs. Thus, the loading in Table 5 and Figure 2 suggests that item reliability was achieved.

Table 5.

Items’ loadings and construct reliability and validity.

The internal consistency assessed using CA, rho_A, and CR showed good results. Generally, values for these indices of 0.708 or above are considered optimal for assessing the dependability of a concept. A cursory look at these indicators verified that the model satisfied its internal consistency criteria [82]. The study’s convergent validity was assessed using the AVE score [81]. The guideline stipulates that all AVE scores must meet a minimum threshold of ≥0.50 for each component [81]. The research satisfied this condition, as all constructs had AVE scores > 0.50. Table 4 further presents the quality of the model by testing for discriminant validity. According to [81], discriminant validity (DV) assesses the structural model for collinearity issues. The DV was tested using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

The guideline stipulates that, in order to attain discriminant validity, HTMT values (correlation coefficients among latent variables) must be less than 0.85. According to Table 6, all values for each construct were below HTMT0.85. This clearly indicates that each construct is separate from the others. After these preliminary evaluations, the study proceeded to examine the research hypotheses in the next section.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity assessment.

6.3.1. Structural Model

Following the evaluation of the measurement model to confirm its compliance with the PLS-SEM criteria, the study reported the findings of the research hypotheses. This was accomplished by evaluating the direction and strength using the route coefficient (R) and the degree of significance by t-statistics derived from 5000 bootstraps, as advised by [81]. The findings are shown in Table 7 and the models shown in Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C.

Table 7.

Structural model and hypothesis testing.

6.3.2. H1 Test: Personal and Professional Identities (PPIs) → Role Confusion (RC)

The data show that this hypothesis is strongly supported. The path coefficient from PPI to role confusion (RC) is 0.636, indicating a strong positive relationship. This suggests that as individuals integrate their personal and professional identities on social media, they experience increased role confusion within their family context. The R-square value for RC is 0.405, meaning that PPI explains 40.5% of the variance in role confusion.

H1a Test: Role Confusion (RC) → Family Influencer Business Performance (FBP)

This sub-hypothesis cannot be directly evaluated using the first model as operational efficiency is not included as a construct. However, the second model provides some insight:

- There is a path coefficient of −0.237 from RC to operational efficiency (OE).

- This negative coefficient supports the hypothesis, suggesting that as role confusion increases, operational efficiency decreases.

H1b Test: Personal and Professional Identities (PPI) → Family Well-Being (FWB)

The data show that this hypothesis is partially supported:

- The direct path coefficient from PPI to FWB is 0.2881.

- The indirect effect through RC is 0.316 (0.636 * 0.496).

- The total effect of PPI on FWB is 0.604, suggesting a moderate positive influence.

- Interestingly, this positive effect contradicts the expected negative impact, indicating that PPI integration might have some beneficial effects on family well-being despite the increased ambiguity.

- The R-square value for FWB is 0.511, which means that the model explains 51.1% of the variance in family well-being.

H1c Test: Role Confusion (RC) → Family Relations (FRs)

This hypothesis is strongly supported by the data. The path coefficient from RC to FRs is very high at 0.942. This indicates that role confusion has a strong positive relationship with family relations, suggesting that as role confusion increases, family relations become more strained.

The R-square value for FRs is 0.934, meaning that the model explains 93.4% of the variance in family relations.

Additional Insights

- Reliability and Validity: Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs are above 0.7, indicating good internal consistency reliability. The model shows high discriminant validity, with HTMT ratios below 0.9 for most construct pairs (models 1 and 2).

- Model Fit: The SRMR value for the first model is 0.133, which is above the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating a less-than-ideal model fit (model 1). The second model shows an improved fit, with an SRMR of 0.078, which is within the acceptable range (model 2).

Thus, Hypothesis 1 and its sub-hypotheses are largely supported by the data, with strong evidence for the relationships between PPI, role confusion, and family relations. The unexpected positive effect of PPI on family well-being suggests that the integration of personal and professional identities on social media may have both positive and negative consequences for families, warranting further investigation into these complex dynamics.

6.3.3. H2 Test: Social Media Use (SMU) → Role Confusion (RC)

This hypothesis is partially supported by the data from the second model. The path coefficient from SMU to role confusion (RC) is 0.701, indicating a strong positive relationship. This suggests that as social media use increases, role confusion among family members also increases, which can lead to misunderstandings and difficulties in resolving conflicts. The R-square value for RC is 0.491, meaning that SMU explains 49.1% of the variance in role confusion.

H2a Test: Social Media Use (SMU) → Conflict Management (CM)

This hypothesis is supported by the data from the second model. The strong positive relationship between SMU and CM (0.701) suggests that social media use does introduce complexity to family dynamics. This complexity extends to conflict management, with the R-square value for CM being 0.682, meaning that SMU explains 68.2% of the variance in conflicts arising from SMU.

H2b Test: Social Media Use (SMU) → Family Well-Being (FWB)

This hypothesis was evaluated indirectly. The model does not provide a direct path from SMU to family well-being (FWB); however, there is an indirect path through role confusion (RC) and family satisfaction (FS). The path coefficient from RC to FS is 0.416, and, from FS to family performance (FP), it is 0.752. This suggests that SMU indirectly impacts family well-being through its effect on role confusion and family satisfaction.

Additional Insights

- Information Sharing: The path coefficient from SMU to information sharing (IS) is 0.701, indicating a strong positive relationship. This suggests that increased social media use leads to greater information disclosure, which may contribute to family conflicts and misunderstandings.

- Privacy Invasion: There is a strong positive relationship (0.701) between IS and privacy invasion (PR). This indicates that as information sharing increases due to SMU, the risk of privacy invasion also increases.

- Model Fit and Reliability: The SRMR value for the second model is 0.078, which is within the acceptable range, indicating a good model fit. Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs are >0.7, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

- R-square Values

- Family Influencer Business Performance: 0.566 (56.6% of variance explained);

- Family Satisfaction: 0.391 (39.1% of variance explained);

- Role Confusion: 0.491 (49.1% of variance explained);

- Information Sharing: 0.491 (49.1% of variance explained);

- Privacy Invasion: 0.491 (49.1% of variance explained).

Hypothesis 2 and its sub-hypotheses are largely supported by the data, with strong evidence for the relationships between SMU, role confusion, information disclosure, and privacy invasion. The model suggests that social media use has significant indirect effects on family dynamics and well-being, primarily through its influence on role confusion and information disclosure. While the model does not directly measure conflict management, the strong relationships between SMU and other constructs imply that it likely introduces complexity to family conflict resolution processes.

6.3.4. H3 Test: Social Media Use (SMU) → Privacy Invasion (PR)

This hypothesis is supported by the data from the second model. There is a strong positive relationship between social media use (SMU) and information sharing (IS), with a path coefficient of 0.701. There is also a strong positive relationship between IS and privacy invasion (PR), with a path coefficient of 0.701. This suggests that increased social media use leads to greater information sharing, which, in turn, increases the risk of privacy invasion. The R-square value for both IS and PR is 0.491, meaning that 49.1% of the variance in these constructs is explained by the model.

H3a Test: Privacy Invasion (PR) → Family Conflict (FC)

This hypothesis is partially supported. While there is not a direct measure of family conflicts, the researchers can use family relations (FRs) as a proxy. The path coefficient from PR to family satisfaction (FS) is 0.416, indicating a moderate positive relationship. This suggests that privacy invasion does impact family dynamics, though not necessarily in the expected negative direction.

H3b Test: Information Sharing (IS) → Privacy Invasion (PR) → Family Satisfaction (FS)

This hypothesis can be inferred from the model. The strong relationship between IS and PR (0.701) suggests that unintentional disclosure is likely to occur. The path from PR to FS (0.416) indicates that these privacy issues do impact family satisfaction. While not directly measuring strain on relationships, the impact on family satisfaction implies potential strain.

H3c Test: Privacy Invasion (PR) → Family Satisfaction (FS) → Family Business Performance (FSB)

This hypothesis is indirectly supported. The model shows that PR has a moderate positive effect on FS (0.416). FS, in turn, has a strong positive effect on family business performance (FBP), with a path coefficient of 0.752. This suggests that privacy concerns (as measured by PR) do influence family dynamics, though the nature of this influence (creating tensions or not) is not explicitly clear from the model.

Additional Insights

- Model Fit and Reliability: The SRMR value for the second model is 0.078, which is within the acceptable range, indicating a good model fit. Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs are above 0.7, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

- Indirect Effects: The model suggests that SMU has indirect effects on family outcomes through its influence on IS and PR. These indirect paths highlight the complex interplay between social media use, privacy concerns, and family dynamics.

- R-square Values

- Family Influencer Business Performance: 0.566 (56.6% of variance explained);

- Family Satisfaction: 0.391 (39.1% of variance explained);

- Information Sharing: 0.491 (49.1% of variance explained);

- Privacy Invasion: 0.491 (49.1% of variance explained).

Hypothesis 3 and its sub-hypotheses are largely supported by the data, with strong evidence for the relationships between social media use, information sharing, and privacy invasion. The model suggests that these factors do impact family dynamics, though the nature of this impact (positive or negative) is not always clear-cut. The strong relationships between constructs indicate that privacy and information risks play a significant role in shaping family outcomes in the context of social media use.

6.3.5. H4 Test: Generational Differences (GDs) → Social Media Use (SMU) → Role Confusion (RC)

This hypothesis was not directly evaluated in the any of the models. However, the researchers can make some inferences based on related constructs. Social media use (SMU) is shown to have a strong positive relationship with role confusion (RC), with a path coefficient of 0.701. This suggests that SMU does impact family dynamics, which could potentially include generational differences in social media usage and understanding.

H4a Test: Generational Differences (GDs) → Social Media Use (SMU) → Role Confusion (RC) → Family Satisfaction

While the researchers cannot directly measure generational differences, the researchers can look at the impact of SMU on family dynamics. The strong relationship between GDs, SMU, and RC (0.701) suggests that generational differences in the approach toward and strategy of social media use does lead to role confusion within the family. RC, in turn, has a strong negative effect on family satisfaction (FS), with a path coefficient of −0.416. This indirect path (SMU→RC → FS) implies that social media use can indeed lead to misunderstandings and potentially conflicts within the family.

H4b Test: Generational Differences (GDs) → Social Media Use (SMU) → Role Confusion (RC)

This specific hypothesis cannot be directly tested with the given models, as there are no constructs measuring generational differences or struggles with technology. However, the researchers can make some general observations:

- The model shows that SMU has significant impacts on various family-related constructs, including role confusion (0.701) and indirectly on family satisfaction.

- These relationships suggest that social media use does influence family dynamics, which could potentially include tensions arising from different levels of comfort or proficiency with social media platforms across generations.

Additional Insights

- Family Performance: Family satisfaction (FS) has a strong positive effect on family performance (FP), with a path coefficient of 0.752. This suggests that factors influencing family satisfaction (including potentially generational differences in SMU) ultimately impact overall family performance.

- Privacy and Information Disclosure: SMU has a strong positive relationship with information sharing (IS) (0.701), which, in turn, strongly influences privacy invasion (PR) (0.701). These relationships could potentially exacerbate generational differences in understanding and managing online privacy.

- Model Fit and Reliability: The SRMR value for the second model is 0.078, indicating a good model fit. Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs are above 0.7, suggesting good internal consistency reliability.

- R-square Values

- Family Influencer Business Performance: 0.566 (56.6% of variance explained);

- Family Satisfaction: 0.391 (39.1% of variance explained);

- Role Confusion: 0.491 (49.1% of variance explained).

While Hypothesis 4 and its sub-hypotheses cannot be directly tested due to the absence of specific constructs measuring generational differences, the model does provide some indirect support for the idea that social media use impacts family dynamics in ways that could be related to generational differences. The strong relationships between SMU, role confusion, and family outcomes suggest that social media use does introduce complexities into family relationships, which may well include generational dimensions. However, to fully test these hypotheses, future research would need to explicitly include measures of generational differences and specific conflicts arising from social media use.

6.4. Interpretation and Cautionary Notes

The structural model demonstrated a high explanatory power, with an R2 of 0.934 for family relations, indicating that the proposed variables—role confusion, family well-being, and privacy breach—account for over 93% of the variance in this outcome. While this suggests strong internal coherence, such a high R2 may also warrant interpretive caution. In behavioural and social sciences, values exceeding 0.75 are rare and can signal potential issues such as model overfitting or shared method variance, particularly when constructs are measured using self-report instruments in a single survey wave.

This concentration of explained variance may reflect real interdependencies between constructs, given the tightly coupled nature of family relationships and platform use, but it may also be partially inflated by common method bias or contextual homogeneity within the sample.

The structural model yielded an exceptionally high R2 value of 0.934 for family relations, indicating that the selected constructs, particularly role confusion, privacy breach, and family well-being, explain over 93% of the variance in this outcome. While this suggests strong model coherence, such a high R2 in behavioural and social science research is unusual and warrants careful interpretation. One possibility is model overfitting, where multiple inter-related constructs may inflate explanatory power due to overlapping variance or shared measurement sources. Given that most constructs were captured via self-report measures in a single survey wave, common method bias (CMB) or contextual homogeneity among respondents (e.g., similar platform use or business models) could further amplify this effect. Another consideration is the emergent nature of the degenerative affordance construct, which may tightly couple constructs like role confusion and trust erosion in ways not yet disaggregated empirically.

Therefore, while the high R2 supports the internal logic of the degenerative affordance framework, it also raises questions about its external validity and replicability. Future studies should consider (1) employing multi-informant or time-lagged designs to mitigate CMB, (2) replicating the model across different entrepreneurial or cultural settings to test generalisability, and (3) introducing distal outcome variables to test for predictive utility beyond intra-family dynamics. These steps would help to validate the framework’s robustness and clarify whether such explanatory strength reflects theoretical accuracy or methodological inflation.

6.5. Data Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

This study employs partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) as the primary statistical technique for analysing the hypothesised relationships. PLS-SEM is particularly suited for exploratory theory development, especially in emerging or under-theorised domains such as degenerative affordances in digital family entrepreneurship. Unlike covariance-based SEM, which is primarily confirmatory and relies on strict distributional assumptions, PLS-SEM allows for more flexibility in handling complex, multi-path models with formative and reflective constructs [81].

The goal of this analysis is not to reject null hypotheses but rather to assess the strength, direction, and explanatory power of theoretically grounded pathways. This approach aligns with the predictive and formative logic of the study, which seeks to develop and test a conceptual model that extends affordance theory into a critical, risk-focused domain. Model evaluation includes standard criteria such as path coefficients, R2 values, effect sizes (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2), in line with contemporary best practices in PLS-SEM research.

By emphasising directional hypotheses over null hypothesis significance testing (NHST), the study prioritises conceptual robustness and practical insight over statistical minimalism. Thus, partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed for the quantitative analysis to investigate the relationships between the different variables—SMU, PPI, FMU, FR, CM, FWB, and PR [83]. The qualitative data followed thematic analysis [71], facilitating the identification of key topics concerning the legitimisation strategies utilised by church leaders. The qualitative insights provide comprehensive elucidations for the quantitative results, aligning with the embedded design.

6.6. Construct Validity and Reliability

The quantitative constructs used in this study were adapted from previously validated measurement instruments. Specifically, privacy invasion was measured using items based on the privacy concern scale developed by [61], while role confusion drew on the widely cited role conflict and ambiguity scale by [84]. Measures for family well-being and conflict management were adapted from relational and organisational behaviours research (e.g., [85,86] while trust erosion incorporated items from [87]).

Construct validity was rigorously assessed using convergent and discriminant validity criteria. Composite reliability (CR) scores ranged from 0.78 to 0.90, indicating strong internal consistency. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, confirming convergent validity. Discriminant validity was established using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, where each construct’s AVE square root exceeded its correlations with other constructs, ensuring adequate conceptual distinctiveness.

This multi-step validation process supports the robustness and reliability of the adapted instruments in the context of family influencer businesses.

One of the most critical relational mechanisms in our model is the erosion of intra-family trust and its mediating role in shaping entrepreneurial legitimacy. Trust functions as a form of symbolic capital in family businesses, especially those operating in the visibility-driven domain of influencer entrepreneurship, where the public’s perception of coherence, credibility, and care is intimately tied to how family members treat each other ([16,17,51]). Our findings suggest that role confusion, privacy breaches, and algorithmic incentives toward overexposure progressively weaken this internal trust. When trust erodes, family members struggle to maintain consistent messaging, coordinated branding, and authentic engagement, thereby destabilising the legitimacy of the business in the eyes of external stakeholders. Empirically, this is supported by strong path coefficients linking trust erosion to diminished perceptions of professionalism and value alignment. Thus, trust is not only a relational glue but a legitimacy gateway: its deterioration compromises not just family harmony but the perceived integrity of the business as an economic actor.

7. Discussion

This study sets out to explore how social media affordances can undermine entrepreneurial legitimacy in family-run influencer businesses. By introducing the concept of degenerative affordances, the researchers examined how relational, emotional, and symbolic risks, particularly role confusion, privacy breaches, and trust erosion, are embedded in platform use. The results offer strong empirical support for this model and generate several critical insights for theory and practice.

The mediation effect of privacy breach on the relationship between social media use and trust underscores the often-invisible costs of platform participation. While visibility may drive engagement and income, it also incentivises the disclosure of private, vulnerable, or ethically ambiguous content. This aligns with [14] work on performative intimacy and extends [12] analysis of platform capitalism to family entrepreneurship. In such settings, privacy loss is not an accidental outcome but is algorithmically rewarded, and thus a structurally induced risk. Interestingly, privacy invasion showed a small but positive association with family well-being. This may reflect a subgroup of influencers who view disclosure as a necessary trade-off for financial gains, social validation, or digital intimacy. Future qualitative research could investigate how such contradictions are rationalised within influencer families.

One of the most critical relational mechanisms in our model is the erosion of intra-family trust and its mediating role in shaping entrepreneurial legitimacy. Trust functions as a form of symbolic capital in family businesses, especially those operating in the visibility-driven domain of influencer entrepreneurship, where the public’s perception of coherence, credibility, and care is intimately tied to how family members treat each other ([16,17,53]). Our findings suggest that role confusion, privacy breaches, and algorithmic incentives toward overexposure progressively weaken this internal trust. When trust erodes, family members struggle to maintain consistent messaging, coordinated branding, and authentic engagement, thereby destabilising the legitimacy of the business in the eyes of external stakeholders. Empirically, this is supported by strong path coefficients linking trust erosion to diminished perceptions of professionalism and value alignment. Thus, trust is not only a relational glue but a legitimacy gateway: its deterioration compromises not just family harmony but the perceived integrity of the business as an economic actor. This reinforces the need to theorise trust not merely as an outcome of platform use but as a mediating infrastructure through which degenerative affordances inflict reputational harm and legitimacy loss.

7.1. Social Media Addiction

The Pew Research Centre reports that 40% of paired individuals express dissatisfaction over the time that their spouse dedicates to their smartphone. For families operating influencer companies, this challenge may be exacerbated as social media platforms grow to become more participatory and “addictive,” complicating the regulation of online time. Research referenced by PsychCentral indicates that American college students characterise the cessation of social media use in a manner akin to withdrawal from drugs and alcohol, manifesting cravings, anxiety, and restlessness.

Within the realm of family influencer businesses, continual exposure to meticulously curated and ostensibly flawless lifestyles online may result in detrimental comparisons. When family influencers present just the most exhilarating and idealised aspects of their lives, it may engender unreasonable expectations for both them and their audience. This detrimental social comparison, referred to as fear of missing out (FOMO), cultivates the perception that others are attaining more success or pleasure, mostly based on their online representation. For families engaged in social media, this may exacerbate tension, jealousy, and discontent, eventually affecting their mental well-being. Emotions of jealousy and dissatisfaction, influenced by social media posts, have been associated with exacerbated depression and a deterioration in general well-being, factors that might jeopardise personal relationships and the performance of the family business. This degenerative affordance of social media use will be discussed in this section.