Abstract

Global refugee flows’ increasing scale and complexity pose significant challenges to national education systems. Turkey, hosting one of the largest populations of refugees and individuals under temporary protection, faces unique pressures in ensuring equitable educational access for refugee students. Addressing these challenges requires a shift from linear, fragmented interventions toward holistic, systemic approaches. This study applies a Community-Based System Dynamics (CBSD) methodology to explore the systemic barriers affecting refugee students’ participation in education. Through structured Group Model Building workshops involving teachers, administrators, and Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) representatives, a causal loop diagram (CLD) was collaboratively developed to capture the feedback mechanisms and interdependencies sustaining educational inequalities. Five thematic subsystems emerged: language and academic integration, economic and family dynamics, psychosocial health and trauma, institutional access and legal barriers, and social cohesion and discrimination. The analysis reveals how structural constraints, social dynamics, and individual behaviors interact to perpetuate exclusion or facilitate integration. This study identifies critical feedback loops and leverage points and provides actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to design sustainable, systems-informed interventions. Our findings emphasize the importance of participatory modeling in addressing complex societal challenges and contribute to advancing systems thinking in refugee education.

1. Introduction

The scale and complexity of global refugee flows have intensified over the past two decades, posing unprecedented challenges to host countries’ social systems, particularly education [1,2]. According to the UNHCR, over 70 million individuals are forcibly displaced worldwide, with Turkey hosting one of the largest refugee populations, including approximately 3.6 million registered Syrians under temporary protection [1]. Refugee children represent a significant proportion of this demographic, highlighting the critical need to ensure their access to quality education.

In Turkey, the educational integration of refugee students has evolved from segregated structures, such as Temporary Education Centers (TECs), to full inclusion in the national public education system [3,4]. While this policy shift demonstrates a commitment to inclusive education, substantial barriers remain. Refugee students encounter systemic challenges including language barriers, socio-economic hardships, cultural dissonance, and psychosocial vulnerabilities [5,6]. Infrastructure limitations, teacher shortages, and resource constraints further complicate the landscape [7].

Traditional policy responses primarily rely on linear, short-term interventions for immediate access and basic integration [7]. However, such approaches often fail to account for the dynamic, interdependent nature of refugee students’ challenges. Research in complex systems suggests that linear solutions applied to non-linear, feedback-rich systems frequently produce unintended consequences [8].

Systems thinking offers an alternative approach by focusing on the interdependencies and feedback structures that sustain systemic issues [9]. In education, system dynamics modeling (SDM) has proven helpful in uncovering the underlying mechanisms that perpetuate inequalities and hinder reform [10,11]. Community-Based System Dynamics (CBSD), a participatory extension of system dynamics, enables stakeholders to construct causal models collaboratively, enhancing the validity and relevance of findings through lived experiences [12].

This study expands the use of causal loop diagram (CLD) methods—previously applied in domains such as education [13], health policy [14], urban mobility [15], and climate-adaptive ecosystem strategies [16]—into the context of refugee inclusion. It demonstrates the methodological flexibility and contextual adaptability of participatory SDM for addressing complex social system interventions.

Building on these insights, this study applies a CBSD approach to investigate the systemic barriers affecting refugee students’ participation in the Turkish education system. By engaging frontline stakeholders—teachers, administrators, and education practitioners—this study aims to co-create a dynamic model that identifies critical feedback loops and leverage points for sustainable interventions. This approach reveals the issue’s structural complexity and offers practical pathways toward fostering more equitable and resilient educational systems for refugee populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Theoretical Framework

This study employed a qualitative, participatory research design grounded in CBSD methodology. CBSD, as articulated by Hovmand [12] and further developed in later studies (e.g., [17,18]), integrates systems thinking principles with participatory modeling processes. These processes enable diverse stakeholders to collaboratively construct causal models of complex social problems, such as refugee education systems.

The CBSD approach draws on system dynamics foundations [8,19] but emphasizes democratic knowledge co-production, allowing diverse stakeholders to contribute to model building through structured Group Model Building (GMB) scripts [12,20]. This method is particularly suited to analyzing refugee education systems, which are characterized by feedback-rich, non-linear dynamics involving multiple interdependent factors such as language acquisition, socio-economic hardship, psychosocial adaptation, institutional capacity, and social cohesion. These systems often operate under conditions of instability and complexity, where interactions between personal, institutional, and policy-level factors create reinforcing and balancing feedback loops, exhibit delayed effects and path dependencies, and amplify feedback structures—thus making linear or siloed policy responses ineffective [21,22].

Given the complexity of refugee education challenges and the inadequacy of linear policy approaches, a systems approach was deemed appropriate [2,6,23]. CBSD enables a shift from top-down diagnostics to bottom-up, stakeholder-informed model development, facilitating the identification of systemic feedback loops and leverage points for intervention. In line with recent studies that utilized CLD-based SDM for policy planning and decision-making in complex systems [16,24], this study adopts a similar approach to map the interdependencies affecting refugee students’ participation in education.

2.2. Participant Selection and Study Context

This study was conducted in Turkey, which currently hosts one of the largest refugee populations, predominantly Syrian nationals under temporary protection. Refugee children represent approximately 50% of this population, creating substantial pressures on the national education system [1,7]. Educational challenges for refugee students are further exacerbated by linguistic barriers, socio-economic vulnerabilities, and systemic resource limitations [5,6].

Participants were selected through purposive sampling, a strategy widely used in qualitative research to ensure the inclusion of individuals with relevant experience and insights [25]. The sample consisted of 18 stakeholders, including the following:

- School administrators (n = 5);

- Teachers (n = 7);

- NGO representatives working in refugee education (n = 4);

- Refugee education coordinators and local policy practitioners (n = 2).

Participants were drawn from provinces with high refugee density to ensure contextual relevance and variability in experiences. Eligibility criteria included the following: (a) direct involvement in refugee education initiatives; (b) a minimum of two years of professional experience; and (c) willingness to engage in participatory, systems thinking processes.

The diverse composition of the sample aimed to capture a broad range of perspectives across different organizational levels and sectors involved in refugee education. Before participation, all individuals received detailed information about the study objectives and procedures and provided informed consent.

Although the initial design of this study aimed to include refugee students and their parents as direct participants, these groups ultimately did not participate. Invitations were extended through intermediary contacts; however, most families expressed reluctance due to limited Turkish language proficiency, discomfort in formal workshop settings, and perceived vulnerability. While their inclusion was ethically and methodologically valued, no coercion or repeated solicitation was applied, by voluntary participation principles. As a result, this study prioritized the insights of educators, school administrators, policy practitioners, and NGO representatives who directly interact with refugee students in the educational ecosystem.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

The data collection process was embedded within a CBSD workshop framework and followed established GMB principles [12,20]. The workshop was held in Gaziantep, Turkey, in February 2025, during the mid-term school break, allowing full-day participation. Participants were selected from three provinces with high refugee student populations—Şanlıurfa, Gaziantep, and Hatay. While the workshop was conducted in Gaziantep, participant composition reflected a broader geographic scope. Several participants, though currently employed in educational institutions across different provinces, were originally from Gaziantep and had returned to the city during the school break. This scheduling not only ensured logistical feasibility but also enabled the incorporation of diverse regional perspectives within a single workshop setting.

To recruit participants with firsthand experience in refugee student integration, the research team defined initial selection criteria focused on institutional role (e.g., school administrators, teachers, NGO representatives, and policy practitioners) and direct involvement with refugee education. These criteria were shared with trusted local contacts, who facilitated participant identification using a snowball sampling strategy. This approach allowed for the targeted inclusion of relevant stakeholders while preserving the participatory integrity of the CBSD process.

The two-day workshop provided sufficient time for collaborative model construction and data elicitation from diverse stakeholders. Participants engaged in a structured series of facilitated activities (e.g., reference mode negotiation, variable elicitation, causal mapping, and action idea generation), described in detail in Section 2.4.

Data were collected through multiple sources to ensure richness and triangulation, including field notes, photographs, participant transcripts, and finalized causal loop diagrams. All materials were anonymized and securely stored according to ethical protocols.

2.4. Group Model Building Scripts

The sessions followed established CBSD facilitation scripts, as outlined in foundational works on Group Model Building [12,18,20], which were adapted to the specific context of refugee education in Turkey. This study’s GMB process followed a structured sequence of six scripts adapted from established CBSD protocols [12,18,20]. These scripts were designed to progressively guide participants through system conceptualization, causal structure development, and intervention design. The overall flow of the CBSD workshop—from stakeholder engagement to model building and prioritization—is summarized in Figure 1.

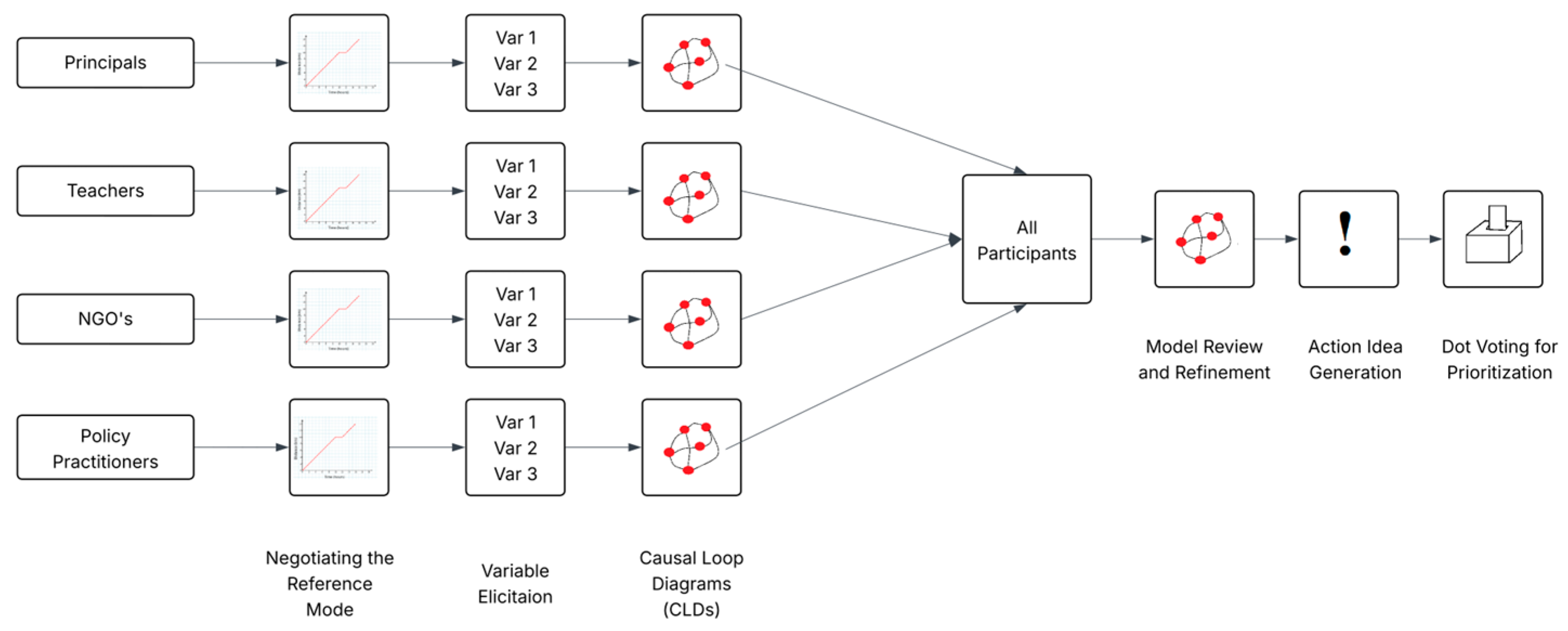

Figure 1.

Process overview: structured flow of the CBSD workshop, from stakeholder engagement to system modeling and intervention design.

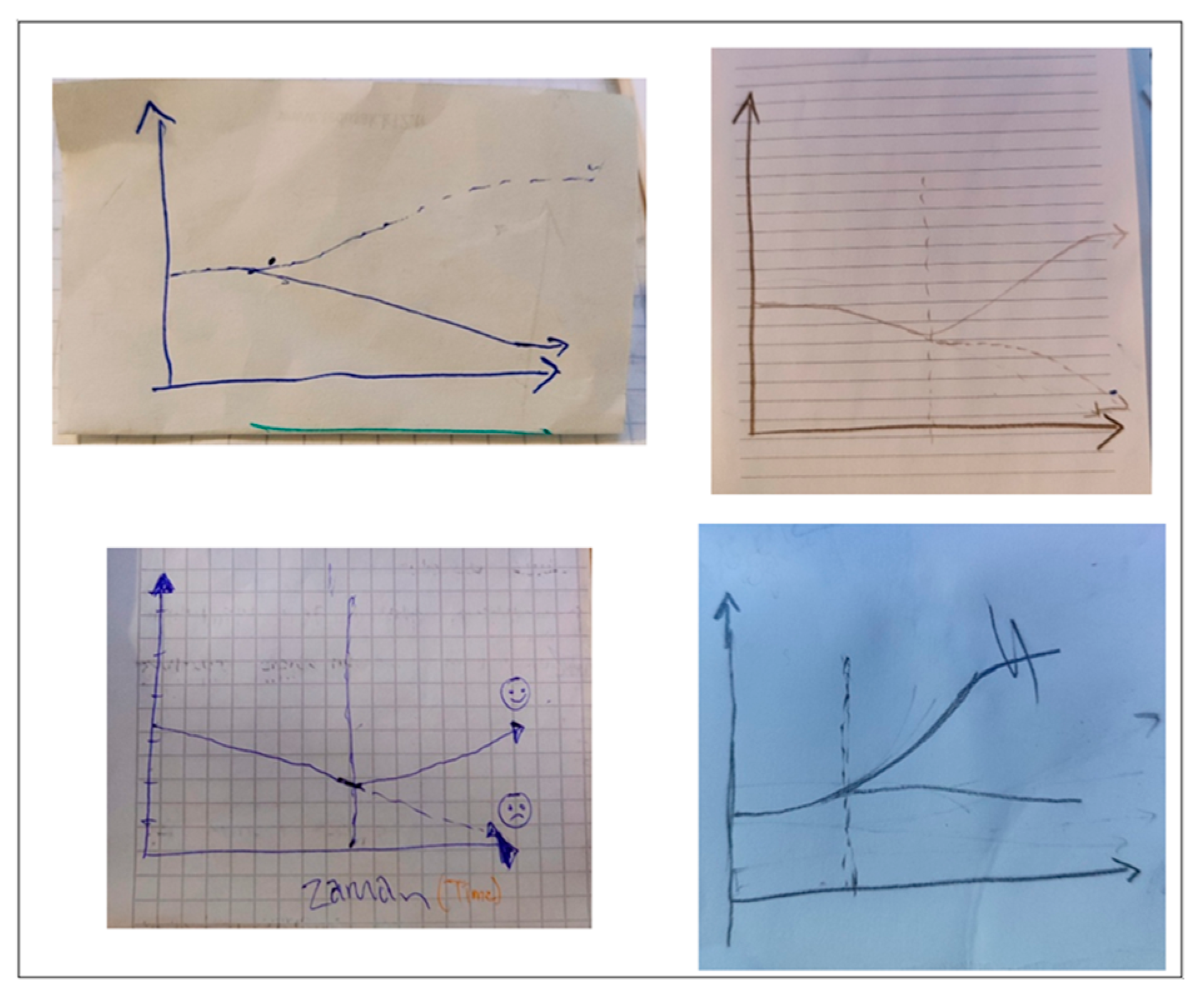

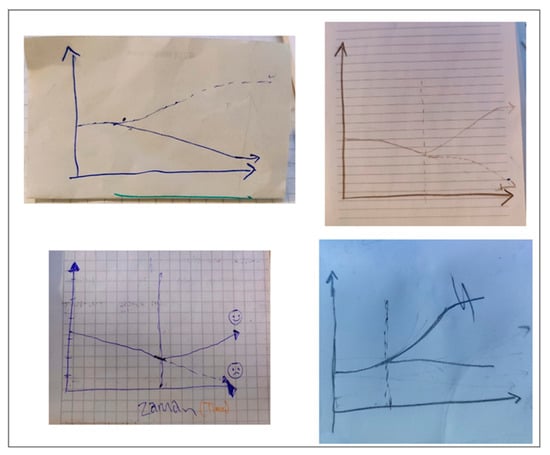

The process began with the Negotiation of a Reference Mode, in which stakeholder groups (school principals, teachers, NGO representatives, and policy practitioners) developed time-based graphs to depict their perceptions of how refugee students’ educational participation had evolved in the past and might unfold in the future. Each group created two trajectories: one representing a hopeful future and another expressing feared outcomes. This activity facilitated the surfacing of mental models and supported the establishment of a shared understanding of system dynamics. The resulting visualizations are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Stakeholder groups developed reference mode graphs to illustrate historical trends and anticipated trajectories (hopeful and feared) of refugee students’ educational participation in Turkey.

Following this, participants engaged in variable elicitation, identifying key factors that influence or are influenced by refugee students’ school participation. The researcher assisted in clustering similar variables and ensuring conceptual clarity to reduce redundancy and overlap [10]. However, to maintain methodological rigor and minimize researcher bias, the facilitation was deliberately non-directive. The researcher’s role was limited to prompting clarification and supporting participant dialog, without making interpretive decisions on behalf of the group.

For example, during the elicitation process, participants from different backgrounds proposed terms such as “economic hardship,” “low income,” and “poverty.” The facilitator asked, “Do these refer to the same concept in your context?” prompting a discussion among the participants. The group then agreed on a shared term that reflected their collective understanding of the concept. In this way, the process prioritized participant ownership while preserving conceptual clarity.

Before initiating the construction of a causal loop diagram (CLD), participants were introduced to the basic principles of systems thinking, feedback loops, and CLDs through a structured orientation session. This session included visual examples, simplified diagrams, and interactive discussions to ensure a shared understanding of core concepts. Since most participants were unfamiliar with CLDs prior to the workshop, the researcher and facilitators provided iterative, real-time guidance throughout the process, supporting participants in identifying causal connections, interpreting polarity, and organizing variables in a meaningful way. However, the researcher maintained a facilitative role, encouraging participants to generate and justify the linkages based on their lived experiences and domain expertise rather than imposing predefined structures.

Next, each group constructed its initial CLD using the elicited variables. These diagrams visualized causal linkages and feedback loops, allowing stakeholders to articulate how interdependencies function across different domains.

In the Model Review and Refinement stage, the researcher synthesized the individual CLDs into a single integrated diagram. Participants reviewed this consolidated model with the researcher, offering feedback and proposing additions to ensure validity and completeness.

Subsequently, in the Action Idea Generation phase, participants identified leverage points within the system and proposed practical interventions. These ideas were noted independently and annotated directly on the CLD to illustrate their connection to specific feedback loops.

The final activity involved Dot Voting for Prioritization, during which participants evaluated intervention ideas based on perceived impact and feasibility. The outcome was a prioritized list of actionable strategies that informed the policy implications of this study.

Overall, this iterative and participatory GMB process enabled the construction of a shared system model that reflected the structural complexity of refugee education and stakeholders’ lived experiences. Although this study was conducted by a single researcher, the participatory integrity of the GMB process was carefully preserved. All modeling activities were guided by established CBSD facilitation scripts and performed in real-time with stakeholders during interactive workshops. The development of CLDs—including variable selection, causal linkage formation, and loop articulation—was co-constructed through structured dialogs. Furthermore, preliminary model versions were shared with participants for feedback and refinement, ensuring collective ownership of the system structure. This study’s modeling process was inherently collaborative, grounded in participant contributions, and reflective of diverse stakeholder insights.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data analysis process adopted in this study was grounded in a qualitative, interpretive framework, aligning with established practices in participatory system dynamics research [26,27]. The analysis was conducted at two complementary levels to capture the system’s structural features and participants’ narrative perspectives.

(1) CLD Synthesis and Structural Analysis

Initially, causal loop diagrams generated by individual stakeholder groups were synthesized into a consolidated system model. This synthesis involved identifying shared variables, harmonizing feedback loops, and resolving inconsistencies in causal logic. Structural analysis techniques—such as polarity mapping and the classification of feedback loops as reinforcing (R) or balancing (B)—were applied to elucidate system behavior patterns [8,27]. Participants frequently highlighted that key system behaviors, such as language acquisition, trauma recovery, and institutional adaptation, evolve over extended periods rather than yielding immediate outcomes. These processes were thus interpreted as implicit time delays within the causal structure. Although not graphically denoted in the CLDs, these delays were acknowledged and incorporated into the interpretation of system dynamics.

(2) Thematic Analysis of Participant Discussions

Workshop transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis using an inductive coding approach [28]. This allowed for the emergence of themes related to systemic barriers, leverage points, stakeholder experiences, and contextual nuances. The themes were then cross-referenced with the structural components of the CLDs to establish coherence between narrative insights and model architecture. This triangulation process enhanced the analytical rigor and validity of the findings by ensuring that qualitative interpretations were firmly grounded in the system structure.

Throughout the analysis, iterative validation was performed through targeted member checking, conducted in two phases. First, preliminary causal loop diagrams (CLDs) were shared with participants at the end of the workshop sessions to obtain immediate feedback on structure and content. Participants were encouraged to highlight missing variables, clarify causal links, and suggest revisions to better reflect their perspectives.

Second, during the post-workshop phase, a subset of participants representing key stakeholder categories—school administrators, teachers, NGO representatives, and policy practitioners—was contacted for follow-up validation via video conferencing. Priority was given to participants residing in urban centers, as they had more stable internet access and adequate technical infrastructure to participate in remote sessions.

In contrast, several participants working in rural schools lacked the necessary equipment or connectivity, which limited their ability to engage in online review. This purposive selection ensured both thematic representation and practical feasibility. The selected group provided additional feedback on the thematic coding and the synthesized system model, contributing to the overall credibility, inclusivity, and shared ownership of the findings.

2.6. Trustworthiness, Reliability, and Ethical Considerations

Ensuring the trustworthiness and transparency of the research process in participatory methodologies, such as CBSD, is paramount. Given CBSD’s collaborative nature and its reliance on stakeholder engagement, particular attention was paid to establishing a respectful, inclusive, and credible environment throughout this study. The researcher employed multiple strategies to enhance the rigor and reliability of the findings.

Triangulation across data sources was employed to strengthen analytical validity. Data were collected through diverse means, including transcriptions of group discussions, the researcher’s field notes, workshop-generated diagrams, and visual artifacts. This multi-source approach allowed for cross-validation of insights and a more nuanced understanding of systemic structures.

Member checking was systematically integrated into the model development process. The researcher presented interim versions of the CLDs to participants for review, critique, and refinement. This iterative validation ensured that the evolving system representations remained grounded in stakeholders’ lived experiences and contextual knowledge.

Meticulous documentation maintained process transparency. The researcher documented all modeling decisions, including variable identification, loop construction, and feedback revisions, to ensure traceability.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Social Sciences and Humanities Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Uşak University (Decision No: 2025-206), in accordance with national and international research ethics standards. All participants were fully informed of the study’s objectives and procedures and advised of their right to withdraw at any time. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before engagement.

All identifying information was removed from transcripts and diagrams to ensure participant confidentiality and data security. Data were securely stored and used exclusively for research purposes.

By adhering to these principles of transparency, inclusivity, and ethical rigor, this study remained faithful to CBSD’s foundational values. It ensured the integrity and credibility of both the process and the outcomes.

3. Results

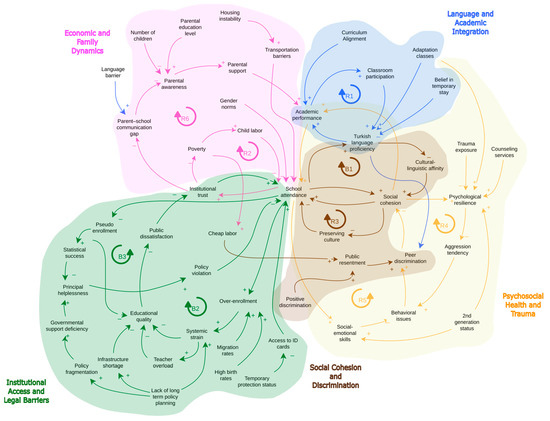

This study utilized a CBSD approach to explore the complex interactions that shape refugee students’ participation in education. The group model-building process identified five major thematic structures, each composed of interconnected causal loops that either reinforce existing challenges or generate balancing mechanisms. These themes reflect the multi-layered nature of the refugee education system, encompassing linguistic, socio-economic, psychological, institutional, and sociocultural dimensions.

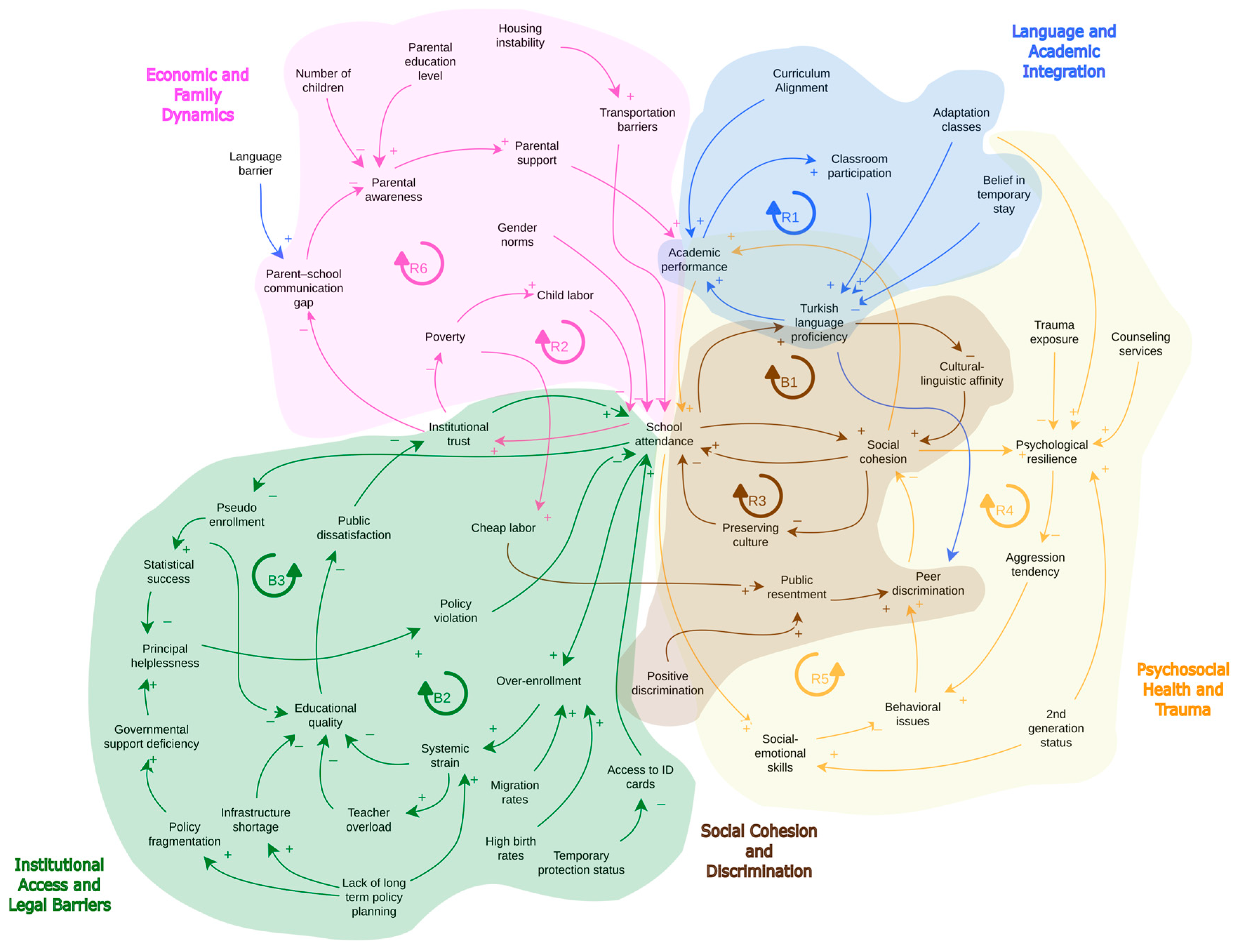

The consolidated causal loop diagram (Figure 3) synthesizes these themes into a single visual model, illustrating the dynamic relationships among key variables. Arrows with positive polarity (+) represent reinforcing relationships, while negative polarity (−) indicates balancing or inverse effects. Reinforcing loops (R) describe feedback mechanisms that amplify trends over time, whereas balancing loops (B) indicate stabilizing forces within the system.

Figure 3.

Synthesized causal loop diagram illustrating systemic dynamics of refugee students’ educational participation.

3.1. Language and Academic Integration

This theme reveals a reinforcing loop (R1) where increased Turkish Language Proficiency enhances Academic Performance, increasing Classroom Participation, further contributing to language development. This positive feedback loop supports refugee students’ integration into the education system. However, deficiencies in language proficiency can reverse this loop, leading to academic failure and an increased risk of dropout. The effects of language acquisition on academic participation do not emerge immediately, as language learning is a time-intensive process involving gradual skill development.

Several exogenous variables influence the functioning of this mechanism. A strong Language Barrier hampers students’ initial engagement with the system, while a lack of Curriculum Alignment limits access to academic content even when language proficiency improves. Adaptation Classes facilitate positive entry into the loop by supporting early language development. Additionally, families’ Belief in Temporary Stay may reduce students’ investment in language learning, negatively affecting their integration process.

These findings indicate that language proficiency is key to refugee students’ academic achievement and classroom participation. The system dynamics suggest that early and sustained language support can have long-term effects on educational continuity.

3.2. Economic and Family Dynamics

This theme identifies two reinforcing loops (R2 and R6) illustrating how economic hardship and family dynamics impact educational participation. In the first loop (R2), increased Poverty leads to higher levels of Child Labor, resulting in lower School Attendance. Reduced attendance weakens families’ institutional trust, further deepening poverty and reinforcing the cycle.

The second loop (R6) shows how a Language Barrier contributes to a Parent–School Communication Gap, diminishing Parental Awareness and reducing Parental Support. Lower parental support negatively affects Academic Performance and School Attendance, weakening institutional trust and expanding the communication gap.

Various exogenous factors affect the intensity of these loops, including Parental Education Level, Number of Children, Housing Instability, Transportation Barriers, and Gender Norms. These factors collectively shape the patterns of school engagement among refugee students.

The findings demonstrate that economic conditions and family dynamics are critical determinants of refugee students’ access to education, highlighting the importance of targeted interventions to enhance educational continuity.

3.3. Psychosocial Health and Trauma

This theme captures two opposing reinforcing loops (R4 and R5) that illustrate the emotional and social dynamics affecting refugee students. The first loop (R4) shows that Trauma Exposure reduces Psychological Resilience, which increases Aggression Tendency and leads to more Behavioral Issues. Elevated behavioral problems foster Peer Discrimination, further weakening Social Cohesion and diminishing psychological resilience, creating a negative spiral. Recovery from trauma requires sustained interventions and time, indicating a significant delay between exposure and psychosocial stabilization.

In contrast, the second loop (R5) depicts a positive cycle where improvements in Social–Emotional Skills reduce behavioral issues and peer discrimination, enhancing Social Cohesion. Increased cohesion positively influences Academic Performance and raises School Attendance, further supporting the development of social–emotional competencies.

Several exogenous variables influence the dynamics within these loops. Counseling and Psychological Support Services play a critical role in moderating the effects of trauma and promoting positive development. In addition, 2nd Generation Status—indicating whether students were born in Turkey or arrived very young—positively impacts Social–Emotional Skills development and Psychological Resilience, facilitating smoother integration into the school environment.

The findings highlight that emotional and social support mechanisms and generational factors are crucial for maintaining refugee students’ educational engagement.

3.4. Institutional Access and Legal Barriers

This theme identifies two balancing loops (B2 and B3) that reveal refugee students’ structural constraints in accessing education. The first loop (B2) shows that higher Migration Rates lead to Over-enrollment, which increases Systemic Strain and reduces Educational Quality. Declining quality fuels Public Dissatisfaction, weakening Trust in Education and lowering School Attendance. Reduced attendance alleviates over-enrollment pressures, creating a balancing dynamic that stabilizes the system at the cost of educational access and equity. The degradation of academic quality and institutional trust often unfolds gradually, resulting in delayed but cumulative impacts on system functioning.

The second loop (B3) illustrates how Governmental Support Deficiency contributes to Principal Helplessness, prompting passive administrative strategies. School principals, facing resource constraints and administrative pressure, may indirectly reduce enrollment figures not through direct data manipulation, but by practices such as misinforming families about registration deadlines, neglecting follow-up on absentee students, or allowing absent students to pass grades without adequate attendance. These practices maintain the appearance of regular school functioning while reducing real attendance pressures, temporarily alleviating the burden on school administrators, and creating a hidden equilibrium that masks systemic challenges.

Several exogenous variables intensify the dynamics within these loops. Temporary Protection Status complicates school registration processes, limiting students’ formal access to education. Access to ID Cards is essential for enrollment; many refugee students remain outside the system without proper identification. Migration Rates and High Birth Rates increase the volume of students requiring services, exacerbating overcrowding. Teacher Overload and Infrastructure Shortages degrade the learning environment even when students are formally enrolled. Policy Fragmentation and Lack of Long-Term Policy Planning contribute to inconsistent regional practices, further undermining system stability.

The findings demonstrate that refugee students’ equitable access to education is constrained by structural and administrative challenges, with school-level coping mechanisms contributing to maintaining an illusory stability rather than addressing systemic problems.

3.5. Social Cohesion and Discrimination

This theme reveals one reinforcing loop (R3) and one balancing loop (B1) that illustrate the dynamics of cultural integration and social exclusion among refugee students. The reinforcing loop (R3) shows that a strong Commitment to Preserving Culture can reduce School Attendance. Lower attendance weakens social cohesion, strengthening the tendency to preserve cultural identity outside the school environment and reinforcing isolation. Social integration and changes in peer acceptance evolve slowly over time, reflecting delayed effects of language proficiency and cultural adaptation.

In contrast, the balancing loop (B1) highlights how Cultural–Linguistic Affinity promotes Social Cohesion, enhances School Attendance, and improves Turkish Language Proficiency. As language proficiency increases, perceived cultural–linguistic differences diminish, reducing the initial affinity and balancing the system. This dynamic is mainly observable in regions where the local language and culture are closer to those of refugee communities, facilitating initial integration.

Several exogenous variables influence these dynamics. Access to Cheap Labor Markets draws refugee families into informal employment sectors, reducing educational participation opportunities. Favorable Discrimination Policies—such as access to health services and social support—aim to enhance refugees’ living conditions but trigger Public Resentment, leading to increased discrimination. This societal tension spills into schools, intensifying peer exclusion and weakening student social cohesion.

The findings suggest that both individual behaviors and broader societal factors play critical roles in shaping refugee students’ educational participation through their impacts on social cohesion and cultural integration.

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretations

This study employed a CBSD approach, engaging a diverse group of teachers, school administrators, migration specialists, and policy practitioners to co-construct a systemic understanding of the barriers affecting refugee students’ participation in education. The participatory nature of the process not only enhanced the contextual validity of the findings but also ensured that the causal loops reflected both lived experiences and institutional realities.

The analysis revealed a complex system of reinforcing and balancing feedback loops across five thematic areas: language and academic integration, economic and family dynamics, psychosocial health and trauma, institutional access and legal barriers, and social cohesion and discrimination. Although analytically distinct, these subsystems were tightly interconnected, demonstrating how structural barriers, social dynamics, and individual behaviors interacted to sustain educational exclusion or promote integration.

Notably, the system exhibited self-limiting dynamics under strain [8,19], where dropout and disengagement functioned both as individual-level failures and as systemic pressure relief mechanisms [29]. Moreover, ghost enrollment and pseudo-stability suggest that institutional responses often prioritize the appearance of functionality over addressing deep-rooted inequities—a classic example of goal displacement under conditions of systemic overload [9,30,31].

These system-wide patterns highlight how fragmented policy environments and eroded institutional trust amplify educational inequities [32,33,34]. Additionally, broader social theories help explain the interplay of structural and psychological dimensions in refugee education systems. For instance, Economic Threat Theory [35] posits that dominant groups may perceive minority populations as economic competitors, fostering prejudice and exclusionary practices. This is evident in how public resentment towards refugee access to services, including education, feeds into school-based discrimination and peer exclusion.

Acculturation Theory [36] offers an additional lens for interpreting findings, such as reinforcing loop R3, where strong cultural preservation tendencies among refugee communities can hinder school attendance and integration. When communities favor separation over integration, social cohesion declines, reinforcing social isolation and exclusion. These theoretical perspectives clarify how perceived economic competition and cultural distance interact with institutional mechanisms, shaping the dynamics of marginalization within the education system.

By leveraging the insights gained through the CBSD process, this study offers a multi-level, empirically grounded understanding of the systemic forces that shape refugee education outcomes. It offers a robust foundation for designing targeted, context-sensitive policy interventions.

4.2. Thematic Discussion

4.2.1. Rethinking Language as a Systemic Lever for Educational Integration

Language proficiency was a pivotal factor that influenced the academic engagement and social inclusion of refugee students. The reinforcing loop identified in this study illustrated how Turkish language proficiency improved academic performance and enhanced classroom participation, thereby accelerating language development. However, the lack of early language support initiated a negative spiral of disengagement and academic failure.

Initially, individualized language support mechanisms were employed, such as separate language courses, in-service language training for teachers, and interpreter services. However, these strategies proved unsustainable at scale due to high financial and operational burdens. Consequently, adaptation classes were introduced as a cost-effective collective solution. While these classes facilitated initial integration, they did not fully address the diverse linguistic needs of students. This reflected a shift from deeper systemic solutions to more manageable but limited interventions. The transition represents a classic example of the Shifting the Burden system archetype [9].

Language barriers not only affected academic outcomes but also peer relationships. Consistent with Cummins’ theory of academic language proficiency, students’ success in language-dependent subjects such as literature, history, and social studies was significantly hindered [37]. In contrast, they managed better in subjects like mathematics and science, where language demands were lower. Teachers—especially those working in urban public schools with high refugee student density—reported that refugee students were able to participate more effectively in these subjects despite limited language skills.

A critical challenge also arose in fulfilling homework and classroom responsibilities. Language barriers made it more difficult for students to understand and complete assignments. Many students lacked familial support at home, as their parents were often not proficient in Turkish. Combined with large family sizes and unstable housing conditions, these circumstances—especially noted in southeastern provinces like Şanlıurfa and Gaziantep—led to further difficulties in academic engagement. This “homework gap” is known to widen achievement disparities over time [38,39].

Another significant and nationally relevant barrier is the mismatch between the standardized Turkish curriculum and the prior educational backgrounds of refugee students. The Turkish curriculum was perceived as more challenging and conceptually different from students’ prior schooling experiences, which increased cognitive load and complicated academic adaptation. Research indicates that curriculum mismatch can hinder the educational integration and success of refugee students [30,40]. The cognitive demands of a curriculum unfamiliar in structure and content exacerbate the challenges already posed by language barriers [41].

CBSD sessions also revealed that teacher support often served as a buffer against these challenges. Early intervention programs and culturally responsive teaching practices were identified as critical leverage points for disrupting negative feedback loops and fostering sustainable educational engagement.

Overall, the findings underscore that language proficiency is not a standalone skill but a linchpin that connects academic success, social inclusion, and psychological resilience. Addressing language barriers and curriculum mismatches through systemic support structures yields compound benefits, enhancing both individual and systemic educational outcomes.

4.2.2. Intergenerational Poverty, Family Roles, and Educational Trade-Offs

Economic hardship and family dynamics emerged as central factors that shaped refugee students’ educational participation. The reinforcing loops identified in this study revealed how poverty increased child labor, which reduced school attendance and undermined institutional trust [32], thereby perpetuating a cycle of educational exclusion.

The role of socioeconomic conditions in educational engagement is well-documented in the literature. Coleman’s seminal report emphasizes that parental education is one of the strongest predictors of children’s academic outcomes [42]. In refugee contexts across Turkey, families often face multiple disadvantages, including low parental education levels, large family sizes, and housing instability, all of which impair school participation [43,44,45,46].

Family size dilutes parental attention and resources, a phenomenon described by the Resource Dilution Theory [43]. Large families must distribute limited financial and emotional resources among more children, decreasing per-child investment in education. This dynamic aligned with CBSD findings, where participants noted that parents with many children in southeastern provinces like Şanlıurfa and Hatay often prioritized immediate economic contributions over long-term educational goals.

CBSD participants—particularly teachers and school principals—further highlighted that parents were often disconnected from the educational process. Due to low educational backgrounds, large family size, and lack of Turkish language skills, many parents did not attend school meetings or participate in parent engagement activities. Teachers frequently observed that such parents, particularly in districts with high refugee density, struggled to understand the expectations and requirements of the Turkish education system and were thus unable to support their children’s learning at home. While this disconnection was locally observed, it also reflects broader national trends in parent–school communication with refugee communities. This lack of involvement, rooted in both structural and linguistic barriers, exacerbated the cycle of disengagement.

Transportation barriers played a critical role. Refugee families, particularly those experiencing housing instability, faced significant challenges in accessing schools located far from affordable housing areas. Consistent with Dryden–Peterson [2] and the GEM Report [30], transportation costs and infrastructure limitations continue to be substantial obstacles to consistent school attendance. This challenge, frequently reported by CBSD participants and confirmed by national reports, is not unique to specific provinces but represents a structural issue across Turkey’s urban and peri-urban areas. The centralized planning structure of the Turkish education system means that such infrastructural issues—though locally experienced—are embedded within national policy and budgetary constraints.

A crucial additional dynamic involved gender norms and economic pressures. CBSD participants reported that due to cultural and religious traditions, some families preferred early marriage or assigned domestic labor roles to girls rather than prioritizing their education. Even among families without strong traditional norms, economic hardship led to educational investments being directed toward sons rather than daughters. These dynamics were commonly observed in low-income communities across different provinces. This reflects broader patterns where gender roles and financial constraints shape educational inequalities [30,47]. Limited resources reinforce a preference for investing in boys’ education, thereby deepening gender disparities.

These factors created a complex web of reinforcing disadvantages, making school attendance precarious for refugee students. Addressing these issues requires multifaceted interventions, including financial support programs, transportation subsidies, and community engagement initiatives that target parental involvement and awareness. Such interventions must be designed with attention to both local contextual variation and national structural constraints, acknowledging the shared and place-specific nature of the educational barriers faced by refugee families in Turkey.

4.2.3. Trauma-Driven Feedbacks and the Limits of Resilience

Psychosocial health and trauma emerged as significant themes influencing refugee students’ educational engagement. The reinforcing loops identified in this study revealed how trauma exposure diminished psychological resilience, increased aggression tendency, and fostered behavioral issues, which in turn escalated peer discrimination and weakened social cohesion, thereby perpetuating cycles of disengagement.

The link between trauma and educational outcomes is well established in the literature. Masten’s work on resilience theory highlights that psychological resilience is a key protective factor in maintaining academic engagement despite adverse experiences [48]. However, traumatic experiences, particularly those related to forced migration, often undermine this resilience. This is consistent with findings from Sirin and Rogers–Sirin, who demonstrate that trauma exposure among refugee students correlates with lower school connectedness and increased risk of behavioral problems [49].

CBSD participants, particularly teachers and school administrators, emphasized that trauma manifested differently among students. Some students exhibited withdrawal behaviors, becoming increasingly socially isolated and reluctant to engage with peers or educators. Others formed peer groups primarily composed of fellow refugee students and exhibited rule-breaking behaviors and disciplinary issues when in groups. Several participants noted that these behaviors were more pronounced in public schools located in urban districts with high concentrations of refugee enrollment, especially in regions such as southeastern Turkey. While individual students often remained passive or reserved, group dynamics appeared to embolden oppositional behavior and increase incidents of rule violations, making classroom management significantly more challenging.

These observations align with the General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency [50], which suggests that social stressors can lead to either internalizing problems like withdrawal or externalizing behaviors such as aggression and deviance. They also resonate with findings on deviant peer clustering in refugee populations [49], particularly under conditions of social marginalization and limited institutional support.

This study also identified a positive reinforcing loop where enhanced social–emotional skills mitigated behavioral issues and promoted social cohesion, leading to improved academic performance and increased school attendance. Consistent with national trends and prior studies, research on the effectiveness of school counseling [51] and trauma-informed school counseling [52], CBSD participants emphasized the importance of providing targeted psychological support services to refugee students.

Moreover, generational differences played a role. Second-generation refugee students, born in Turkey or who had arrived at a very young age, often exhibited higher levels of resilience and social–emotional competence than first-generation students. This generational effect indicated that acculturation and reduced trauma exposure contributed positively to educational engagement—a finding aligned with Berry’s Acculturation Theory [36].

These findings, while grounded in participants’ local experiences across provinces like Gaziantep, Şanlıurfa, and Hatay, reflect broader systemic patterns embedded in Turkey’s centralized education system. National policies on school counseling and student support appear insufficiently adapted to the specific needs of refugee populations, especially in resource-constrained areas. This underscores the necessity for context-sensitive but centrally coordinated reforms in mental health provision within the education system. Addressing trauma-related barriers is not merely a supportive measure but a structural necessity for fostering equitable educational outcomes.

4.2.4. Administrative Coping and the Illusion of Access

Institutional access and legal barriers were identified as significant systemic factors influencing refugee students’ participation in education. The balancing loops (B2 and B3) revealed in this study demonstrated how migration and high birth rates contributed to over-enrollment, increased systemic strain, and a decline in educational quality. Decreased quality eroded institutional trust [32], which lowered school attendance and created a self-limiting dynamic of academic disengagement.

From a broader perspective, Turkey’s nationwide challenges—such as high population density, financial constraints, and an already overburdened education system—have compounded the effects of mass migration. Rather than implementing structural reforms, the system appeared to settle into a fragile equilibrium marked by pseudo-stability [30] and self-reinforcing decay [9], tolerating dysfunction while failing to address root causes.

Structural impediments—including the bureaucratic hurdles of Temporary Protection Status and limited access to ID cards—further complicated school registration, reinforcing exclusionary dynamics [1,2]. Additionally, persistent teacher shortages and inadequate infrastructure continued to weaken the system’s capacity to accommodate new students [46,53].

CBSD participants—particularly school administrators and teachers from southeastern provinces—strongly emphasized the systemic consequences of poorly planned, short-term integration policies. Echoing national-level findings [7,30], they noted that incoherent policy responses not only strained local school environments but also led to goal displacement, wherein the emphasis shifted from meaningful educational inclusion to preserving statistical indicators [31]. Although these accounts reflected provincial realities, they also highlighted structural problems rooted in Turkey’s highly centralized education governance. In this system, top–down policies often fail to reflect the differentiated needs of local contexts, leading to uniform solutions that intensify, rather than alleviate, systemic pressures across regions.

Long-term strategic planning was widely regarded as a missing component. Participants described how schools, left without adequate state support, resorted to improvised and localized coping mechanisms. This pattern resembled adaptive governance [54], wherein dysfunction is tolerated rather than rectified. Such practices reflect institutional inertia [55] and a growing tolerance for dysfunction [56], where the system resists transformative change despite evident degradation.

Incrementalism [57] characterized many of the implemented reforms—small-scale adjustments that failed to address structural inequalities. Consequently, practices such as pseudo-enrollment and ghost student documentation persisted, masking system failure beneath a facade of stability [30].

Moreover, consistent with Strain Theory in Educational Systems [58], the compounded workload faced by teachers in under-resourced settings intensified burnout and further undermined educational quality. Delayed policy adaptations [8,19] left pressing needs unmet, while prolonged exposure to dysfunction led to normalized tolerance of failure [59]. Ultimately, dropout emerged as a hidden systemic release valve [29], relieving institutional pressure at the cost of equitable access.

These findings collectively call for comprehensive and future-oriented policy reforms that address both structural barriers and governance inefficiencies to ensure sustainable educational inclusion for refugee students across all regions.

4.2.5. Between Belonging and Exclusion: Cultural Tensions in School Settings

Social cohesion and discrimination emerged as critical themes influencing refugee students’ educational experiences. The reinforcing loop (R3) identified in this study illustrated that a strong commitment to preserving culture led to lower school attendance and weakened social cohesion, reinforcing isolation among refugee students. Many families avoided sending their children to school to prevent the loss of Arabic language skills and cultural identity. However, their efforts to preserve culture occurred within the broader context of Turkish society, making complete cultural isolation challenging.

CBSD participants—particularly teachers and school administrators—highlighted a striking pattern in regions with high cultural–linguistic affinity, such as southeastern Turkey, where Kurdish and Arab communities reside. In these localities, refugee students reportedly adapted more smoothly to school environments, supported by linguistic and cultural similarities. However, as students progressed through the Turkish national education system, a centralized and standardized structure, they experienced gradual cultural shifts. The initial proximity that facilitated integration ultimately gave way to cultural transformation—a dynamic balancing process shaped by systemic norms beyond local variation.

The perceived cultural distance between groups plays a central role in shaping acculturation processes. Reduced distance facilitates adaptation and accelerates cultural change [36]. Refugee families’ ambivalence toward formal education reflected a tension between maintaining cultural identity and adjusting to national assimilation pressures embedded in curricula, language, and school norms.

Social exclusion and peer discrimination were also recurring concerns. Teachers consistently reported that such exclusion undermined students’ sense of belonging and school connectedness, leading to disengagement. Language barriers intensified this exclusion, whereas initial cultural affinity sometimes served as a buffer [60,61,62,63]. While many of these dynamics were grounded in regional experience, they were seen as representative of broader societal patterns reinforced through national education discourse and public sentiment.

Economic tensions further exacerbated these dynamics. Refugee families, often concentrated in low-wage labor markets, were perceived as economic competitors. Additionally, positive discrimination policies—such as preferential access to healthcare and financial aid—reportedly fueled public resentment in disadvantaged host communities. As several teachers noted, these sentiments were transmitted intergenerationally from parents to children and manifested as peer-level exclusion within schools.

Taken together, these findings underscore the need for inclusive education policies that promote language acquisition without cultural erasure, actively combat discrimination, and foster cross-cultural understanding. Enhancing social cohesion in schools—especially in demographically diverse regions—requires systemic responses that account for both localized tensions and nationally embedded structural inequities.

4.3. System-Wide Insights

The CBSD process and the causal loop diagram collectively revealed a complex, tightly interconnected system shaping refugee students’ educational participation. Although the themes were analyzed individually, the system exhibited significant cross-theme interactions, creating feedback-rich dynamics that complicated straightforward interventions.

One critical insight was the interdependence between Language Proficiency, Curriculum Demands, Social Cohesion, and Academic Performance. Language barriers and curriculum mismatch jointly increased cognitive load, particularly in language-heavy subjects, while limited familial support exacerbated homework gaps. These dynamics hindered academic success and amplified social isolation and disengagement. Improved language skills, however, enhanced educational outcomes and accelerated cultural assimilation, creating tensions within refugee families prioritizing cultural preservation.

Economic dynamics further entangled this system. Poverty, child labor, large family size, and parental disengagement reinforced educational exclusion. Gender norms and economic pressures disproportionately affected girls’ educational access, leading to early marriage, domestic labor, or preference for boys’ schooling. Systemic resource constraints such as teacher shortages and infrastructure limitations exacerbated institutional strain. These conditions eroded Institutional Trust and created a fragile pseudo-stability where dropout functioned as a silent mechanism for systemic pressure relief [29].

Administrative practices, such as pseudo-enrollment and ghost students, masked underlying dysfunctions, illustrating a Shifting the Burden archetype [9]. Rather than addressing root causes such as legal barriers, resource inequalities, and policy incoherence, the system adapted through short-term coping strategies that delayed necessary structural reforms.

Regional variability also played a role. In areas with high Cultural–Linguistic Affinity, refugee students adapted more easily to school environments. Nevertheless, the overarching structure of the national education system remained a powerful agent of cultural change, gradually reshaping students’ identities.

Finally, systemic inertia and delays in policy adaptation [8,19] ensured that educational reforms lagged behind demographic and social shifts, while tolerance for dysfunction normalized inequalities [59]. These findings highlight that refugee students’ academic challenges were not isolated incidents but manifestations of deeper systemic imbalances that require holistic, multi-dimensional interventions.

4.4. Between Humanitarian Concern and Structural Fatigue: Stakeholder Reflections

While CBSD participants represented diverse roles—including teachers, school administrators, policy practitioners, and NGO representatives—their perspectives revealed both role-specific emphases and a shared underlying sentiment regarding the long-term future of refugee students in Turkey.

Teachers predominantly highlighted the instructional burden posed by language barriers, expressing frustration over teaching in classrooms where many students lacked functional proficiency in the Turkish language. Their concerns centered on classroom management difficulties, widening achievement gaps, and the emotional toll of trying to address diverse needs without adequate institutional support.

School administrators, although less directly involved with students, emphasized the pressure on school infrastructure, issues of overcrowding, and complaints from local parents who blamed refugee students for the decline in educational quality. They frequently described feeling caught between institutional responsibilities and community dissatisfaction.

Policy practitioners primarily focused on systemic planning challenges. They noted that legal ambiguities, inconsistent policy implementation, and the lack of sustainable resource allocation limited the effectiveness of integration efforts. They also acknowledged that many national-level strategies were reactive rather than proactive, contributing to pseudo-stability rather than long-term solutions. As also emphasized by policy practitioners, concerns about the sustainability of refugee integration have been echoed in recent international reports. According to the 2024 Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP), host communities in Turkey are experiencing increasing pressure due to underfunded services, infrastructure deficiencies, and demographic imbalances in areas where refugee populations outnumber local residents [64]. These conditions have led to growing public resentment and social tensions, particularly in underserved regions, prompting calls for long-term and durable solutions, including responsibility sharing and options for voluntary, informed return [64]. Similarly, the UNHCR 2024 Global Trends Report highlights that Turkey continues to host one of the world’s largest refugee populations yet still faces limited international burden-sharing and structural support, which exacerbate its vulnerabilities amid economic and political instability [1].

While advocating for inclusive support mechanisms, NGO representatives presented a more nuanced perspective on community dynamics. They reported that local resentment had intensified over time, particularly in areas where refugee populations had grown to outnumber local residents. Combined with poorly managed integration processes, this demographic imbalance was said to fuel fears among host communities that refugees could permanently reshape the cultural and socioeconomic fabric of Turkish society. Additionally, concerns were raised that, if exclusionary school experiences were not addressed, youth marginalization could increase and lead to potential social unrest.

Despite differences in focus, participants across all groups shared a widespread perception that Turkey has been largely left to manage the refugee crisis on its own. This perceived abandonment has compounded local concerns about resource scarcity, policy fatigue, and sociocultural tensions. Many stakeholders noted that better-resourced refugees had migrated to Europe or North America, leaving Turkey with a disproportionately vulnerable population. Participants consistently expressed, both implicitly during formal sessions and more explicitly in informal and candid conversations, that the situation would be more manageable if the refugee population were eventually repatriated. While recognizing the legitimacy of displacement and expressing empathy for refugee experiences, they also questioned the long-term viability of continued integration. These concerns reflect the dual pressures of humanitarian responsibility and structural overload, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable, internationally coordinated interventions in refugee education and integration.

4.5. Policy and Practice Implications

The system-wide analysis highlights deeply embedded challenges in the educational participation of refugee students that require realistic, context-sensitive, and multi-phase interventions. Building upon Meadows’ leverage points framework [65] and considering Turkey’s current economic and political conditions, we propose the following targeted strategies:

(1) Short-Term Interventions (Quick Gains)

- Expand Language Support Programs: Increase access to adaptation classes, early language intervention, and bilingual instructional materials to mitigate initial academic and social barriers.

- Enhance Teacher Training: Provide in-service training on culturally responsive pedagogy and trauma-informed practices.

- Homework Support Systems: Establish after-school homework clubs and peer mentoring programs to address the homework gap.

- Social Awareness Campaigns: Launch public awareness initiatives to combat xenophobia and discrimination, emphasizing that neglecting refugee youth today may lead to greater societal risks in the future.

(2) Medium-Term Interventions (Structural Adjustments)

- Institutional Capacity Building with International Support: Strengthen educational infrastructure and address teacher shortages through external funding mechanisms, international cooperation, and development aid. Encourage countries that expect Turkey to host refugees to share the responsibility by opening migration pathways or increasing financial support.

- Curriculum Adaptation and Flexibility: Adjust the curriculum to accommodate the needs of refugee students, reducing cognitive load and bridging prior educational gaps.

- Gender-Sensitive Education Policies: Implement initiatives to promote girls’ education and counteract cultural biases.

(3) Long-Term Interventions (Systemic Reforms)

- Strategic Planning with Global Cooperation: Develop a comprehensive, long-term national refugee education strategy supported financially and politically by international actors.

- Voluntary Repatriation Programs: Work with international organizations to develop secure and dignified return programs for refugees who wish to return to their countries of origin.

- Inclusive Education System Reform: Transform the education system to be more inclusive and capable of managing diversity.

- Monitoring and Accountability Mechanisms: Establish robust systems to track the educational progress of refugee students and ensure transparency in policy outcomes.

Implementing these interventions will require Turkey to leverage international partnerships and distribute the refugee management burden more equitably across global actors, moving beyond unilateral national efforts toward a more collaborative, sustainable solution.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study, while offering a comprehensive system dynamics analysis of refugee students’ educational participation, is not without limitations. First, the findings are based on a CBSD process that, while rich in contextual insights, inherently reflects the perceptions and experiences of a selected group of teachers, administrators, and policy practitioners. Broader stakeholder inclusion—such as students and parents—could further enrich the model.

Second, the SDM developed is qualitative and causal. As noted in the article, this study was intentionally designed as a qualitative analysis due to the lack of robust quantitative data. Although causal loop diagrams effectively reveal system structures and feedback mechanisms, they cannot provide predictive simulations without empirical parameterization. Future research could integrate empirical datasets and develop hybrid models combining system dynamics with agent-based simulations or stock-and-flow structures to validate and simulate the dynamics identified.

Third, the study’s findings are context-bound, shaped by the specific socio-economic and political conditions encountered by participants across the selected provinces in Turkey. While many mechanisms identified in this study may be generalizable, significant cultural and policy differences not only across countries but also within countries, particularly between central and peripheral regions, limit the direct applicability of findings. In the case of Turkey, for example, the centralized nature of educational governance coexists with considerable regional variation in sociocultural dynamics and institutional capacity. Therefore, comparative studies across and within national contexts are essential to generate more nuanced insights into how refugee education systems function under varying structural and cultural conditions.

Finally, this study does not extensively address the long-term psychological and socio-emotional impacts of protracted displacement on students’ educational trajectories. Future research should integrate longitudinal designs to assess how early educational experiences influence long-term academic, social, and occupational outcomes for refugee youth.

Addressing these limitations would enhance the robustness of future SDMs and provide more profound, actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive system dynamics analysis of refugee students’ multifaceted barriers to accessing and succeeding in the Turkish education system. Using a CBSD approach, the research engaged teachers, school administrators, NGO representatives, and policy practitioners in a collaborative model-building process to capture the interrelated structures shaping educational outcomes.

The resulting causal loop diagrams revealed complex configurations of reinforcing and balancing feedback loops across five thematic domains: language proficiency, economic and family dynamics, psychosocial health, institutional access, and social cohesion. These loops illustrate how systemic inequalities and fragmented policy responses interact with local-level implementation challenges, often compounding disadvantages for refugee learners over time.

Notably, this study found that educational barriers are not merely technical or logistical but are deeply embedded in cultural expectations, structural economic strain, and institutional constraints. Issues such as curriculum mismatch, gendered schooling norms, limited access to formal registration, and institutional overload create interdependent patterns of exclusion that resist linear policy solutions.

Significantly, several system behaviors—such as language acquisition, trauma recovery, and erosion of institutional trust—unfold over extended periods, signaling implicit time delays. These temporal dynamics highlight the need for long-term, adaptive policy frameworks that anticipate delayed outcomes and support sustained intervention, rather than short-term, fragmented efforts.

This research emphasizes that refugee education should not be treated as an isolated policy domain but as an integral component of national education and social systems. Addressing these issues requires holistic, multi-level interventions and robust international cooperation to ensure equitable, inclusive, and sustainable educational opportunities for refugee youth.

By shedding light on the systemic complexities shaping refugee students’ educational experiences, this study aims to contribute to more informed policy design, foster a more profound understanding among practitioners, and ultimately support the development of educational environments where all students, regardless of background, can thrive.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical and confidentiality restrictions but may be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to sincerely thank all participants in the CBSD workshops, including teachers, school administrators, NGO representatives, and policy practitioners, for their valuable time, insights, and contributions. Their lived experiences and professional perspectives were essential in shaping the systemic understanding presented in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBSD | Community-Based System Dynamics |

| SDM | system dynamics modeling |

| CLD | causal loop diagram |

| GMB | Group Model Building |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| GEM Report | Global Education Monitoring Report |

| R | reinforcing loop |

| B | balancing loop |

| 3RP | Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan |

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR Education Report 2024: Refugee Education: Five Years on from the Launch of the 2030 Refugee Education Strategy; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-92-1-106751-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden-Peterson, S. The Educational Experiences of Refugee Children in Countries of First Asylum; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aras, B.; Yasun, S. The Educational Opportunities and Challenges of Syrian Refugee Students in Turkey: Temporary Education Centers and Beyond; IPC: İstanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Erden, O. The Effect of Local Discourses Adapted by Teachers on Syrian Child Refugees’ Schooling Experiences in Turkey. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H.; Kaya, Y. The Educational Needs of and Barriers Faced by Syrian Refugee Students in Turkey: A Qualitative Case Study. Intercult. Educ. 2017, 28, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, M.R.J.; Keskiner, E.; Schneider, J.; Lelie, F.; Ghaeminia, S. No Lost Generation? Education for Refugee Children: A Comparison between Sweden, Germany, The Netherlands and Turkey. In The Integration of Migrants and Refugees: An EUI Forum on Migration, Citizenship and Demography; Bauuböck, R., Tripkovic, M., Eds.; EUI: Florence, Italy, 2017; pp. 62–79. ISBN 978-92-9084-460-0. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: Factors That Shape Well-Being; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Ed.; OECD Reviews of Migrant Education; OECD: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-92-64-20090-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; Nachdr; Irwin/McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-07-238915-9. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, 2nd ed.; Doubleday/Currency: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.C.; Oliva, R. The Greater Whole: Towards a Synthesis of System Dynamics and Soft Systems Methodology. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 107, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, K.E.; Cavana, R.Y. Systems Thinking, System Dynamics: Managing Change and Complexity, 2nd ed.; repr.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Rosedale, MD, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-877371-03-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand, P.S. Community Based System Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4614-8762-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Wang, L.; Goh, J.; Shen, W.; Richardson, J.; Yan, X. Towards Understanding the Causal Relationships in Proliferating SD Education—A System Dynamics Group Modelling Approach in China. Systems 2023, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Badrinath, P.; Lacey, P.; Harwood, C.; Gray, A.; Turner, P.; Springer, D. Use of System Dynamics Modelling for Evidence-Based Decision Making in Public Health Practice. Systems 2023, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams Esfandabadi, Z.; Ranjbari, M. Exploring Carsharing Diffusion Challenges through Systems Thinking and Causal Loop Diagrams. Systems 2023, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi, M.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O.; Giffin, A.L.; Mackey, B. Evaluating Coral Reef Ecosystem Services Outcomes from Climate Change Adaptation Strategies Using Integrative System Dynamics. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.C.; Husemann, E. System Dynamics Mapping of Acute Patient Flows. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2008, 59, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D.F.; Vennix, J.A.M.; Richardson, G.P.; Rouwette, E.A.J.A. Group Model Building: Problem Structuring, Policy Simulation and Decision Support. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2007, 58, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.W. (Ed.) Industrial Dynamics; Reprint of First Ed. 1961; Martino Publ: Mansfield Centre, CT, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-61427-533-6. [Google Scholar]

- Vennix, J.A.M. Group Model Building: Facilitating Team Learning Using System Dynamics; J. Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-471-95355-5. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Sidhu, R.K. Supporting Refugee Students in Schools: What Constitutes Inclusive Education? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2012, 16, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinson, H.; Arnot, M. Sociology of Education and the Wasteland of Refugee Education Research. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2007, 28, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, M.; Garnett, S.G.; Bruckner, E. Urban Refugee Education: Strengthening Policies and Practices for Access, Quality and Inclusion; Policy Report; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaboulian Zare, S.; Alipour, M.; Hafezi, M.; Stewart, R.A.; Rahman, A. Examining Wind Energy Deployment Pathways in Complex Macro-Economic and Political Settings Using a Fuzzy Cognitive Map-Based Method. Energy 2022, 238, 121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7619-1971-1. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Andersen, D.L. Collecting and Analyzing Qualitative Data for System Dynamics: Methods and Models. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2003, 19, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.P. Reflections on the Foundations of System Dynamics. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2011, 27, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumberger, R.W. Dropping Out: Why Students Drop Out of High School and What Can Be Done About It; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-674-06316-7. [Google Scholar]

- Global Education Monitoring Report Team. Global Education Monitoring Report 2019: Migration, Displacement and Education—Building Bridges, Not Walls; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 978-92-3-100283-0. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Bureaucratic Structure and Personality. Soc. Forces 1940, 18, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.S.; Schneider, B.L. Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement; The Rose Series in Sociology; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-61044-096-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, 4th ed.; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-8077-4765-0. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, M.I. New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7914-8143-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, W.G.; Stephan, C.W. Predicting Prejudice. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1996, 20, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Bilingualism and Minority-Language Children; Language and Literacy Series; OISE Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1981; ISBN 978-0-7744-0239-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H.; Robinson, J.C.; Patall, E.A. Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987–2003. Rev. Educ. Res. 2006, 76, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Homework Purposes Reported by Secondary School Students: A Multilevel Analysis. J. Educ. Res. 2010, 103, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.W.; Jacobs, J.; Schramm, S.; Splittgerber, F. School Transitions: Beginning of the End or a New Beginning? Int. J. Educ. Res. 2000, 33, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Equality of Educational Opportunity. Equity Excell. Educ. 1968, 6, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. Family Size and Achievement; Studies in Demography; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-520-33059-7. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, D.B. When Bigger Is Not Better: Family Size, Parental Resources, and Children’s Educational Performance. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; European Commission. Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023: Settling In; Indicators of Immigrant Integration; OECD: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-94177-9. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. International Migration Outlook 2023; International Migration Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-85670-7. [Google Scholar]

- Unterhalter, E. Global Inequality, Capabilities, Social Justice: The Millennium Development Goal for Gender Equality in Education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2005, 25, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-1-4625-5766-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin, S.; Rogers-Sirin, L. The Educational and Mental Health Needs of Syrian Refugee Children; MPI: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.; Dimmitt, C. School Counseling and Student Outcomes: Summary of Six Statewide Studies. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2012, 16, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]