Measuring Corporate Resilience Using Dynamic Factor Analysis: Evidence from Listed Companies in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Research Design

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Research Design

2.2.1. Indicators System

2.2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.3. Data Sources

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Results of Variability

3.2. Validity Analysis

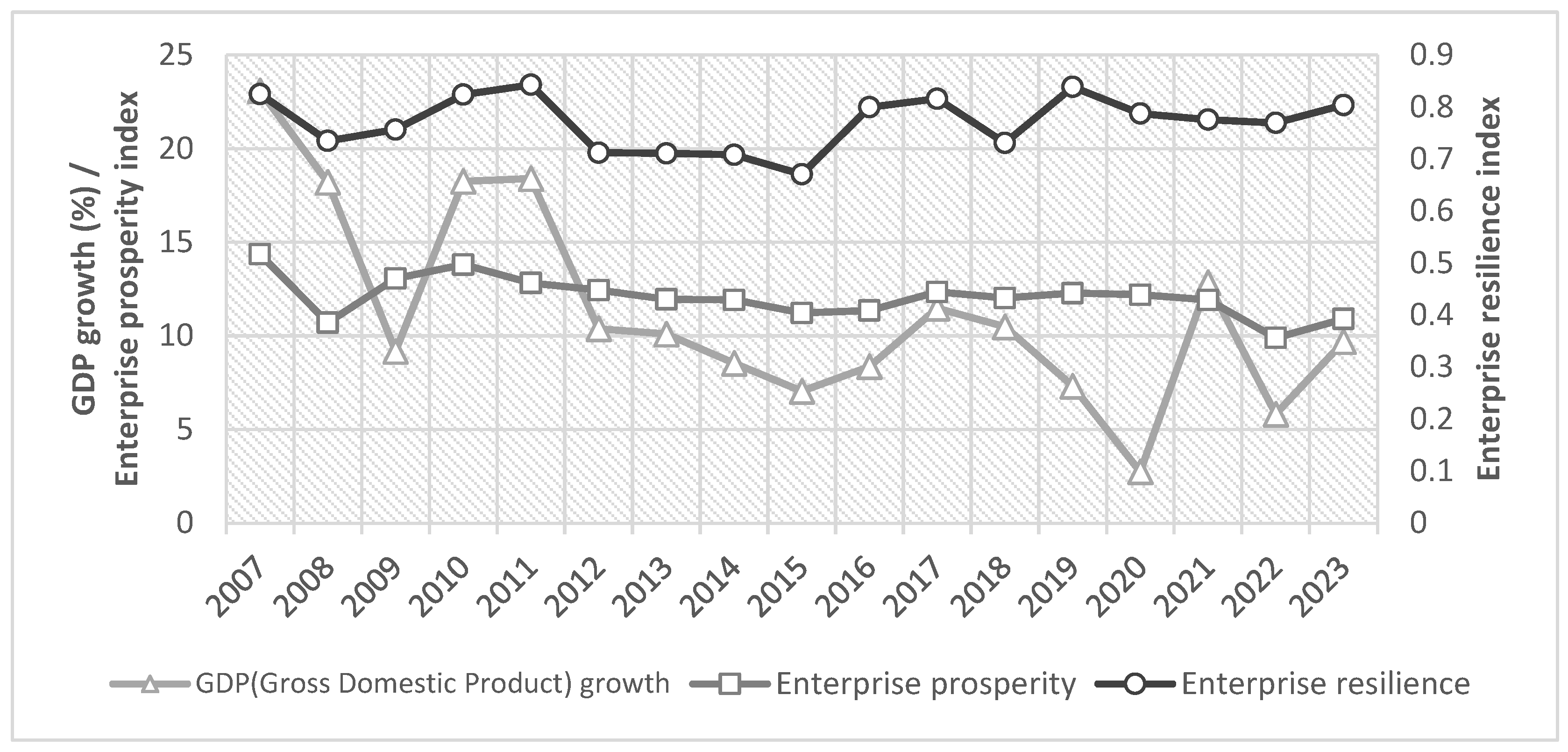

3.2.1. Comparison with Realistic Indicators

3.2.2. Comparative Testing with Existing Corporate Resilience Indicators

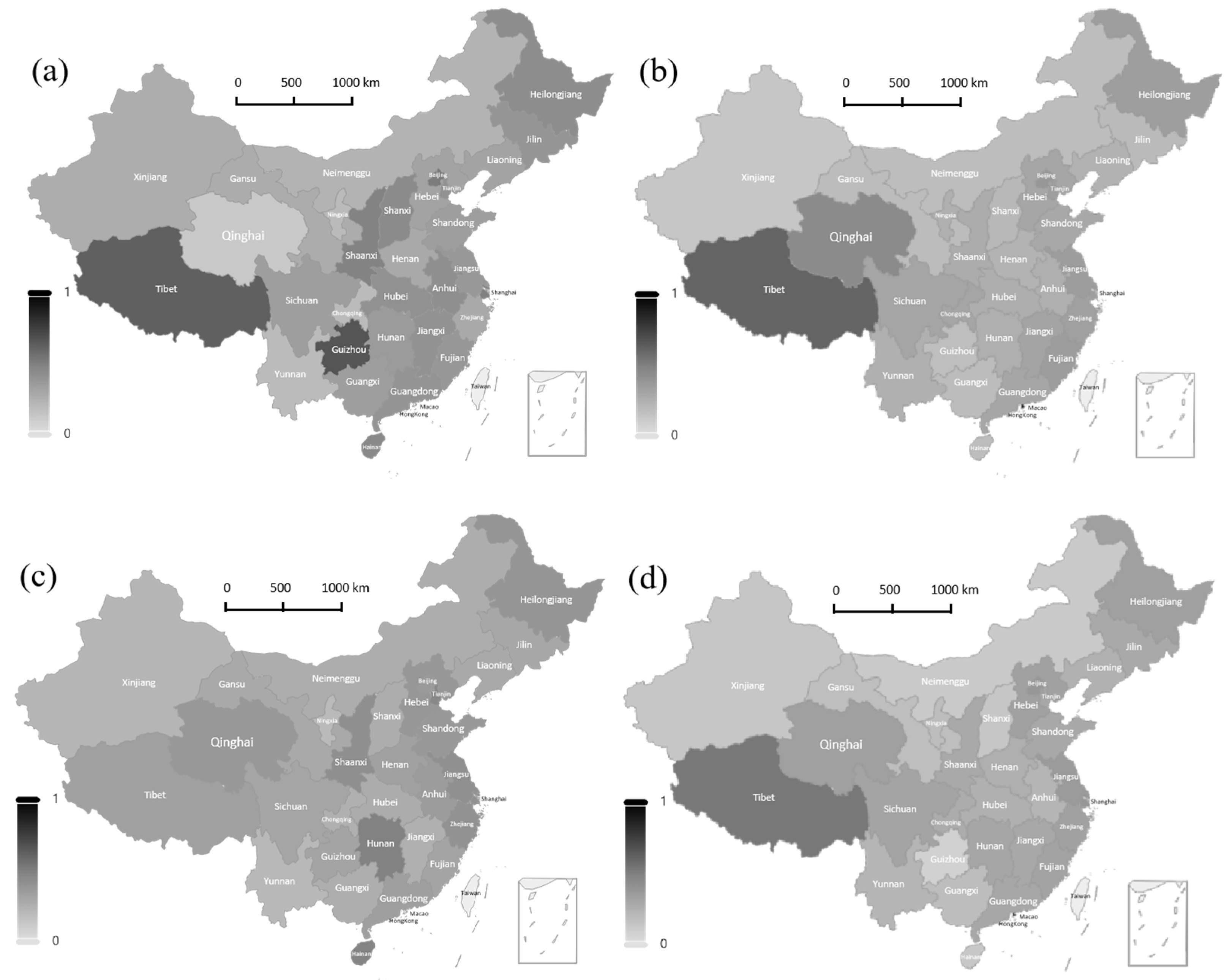

3.3. Character Analysis

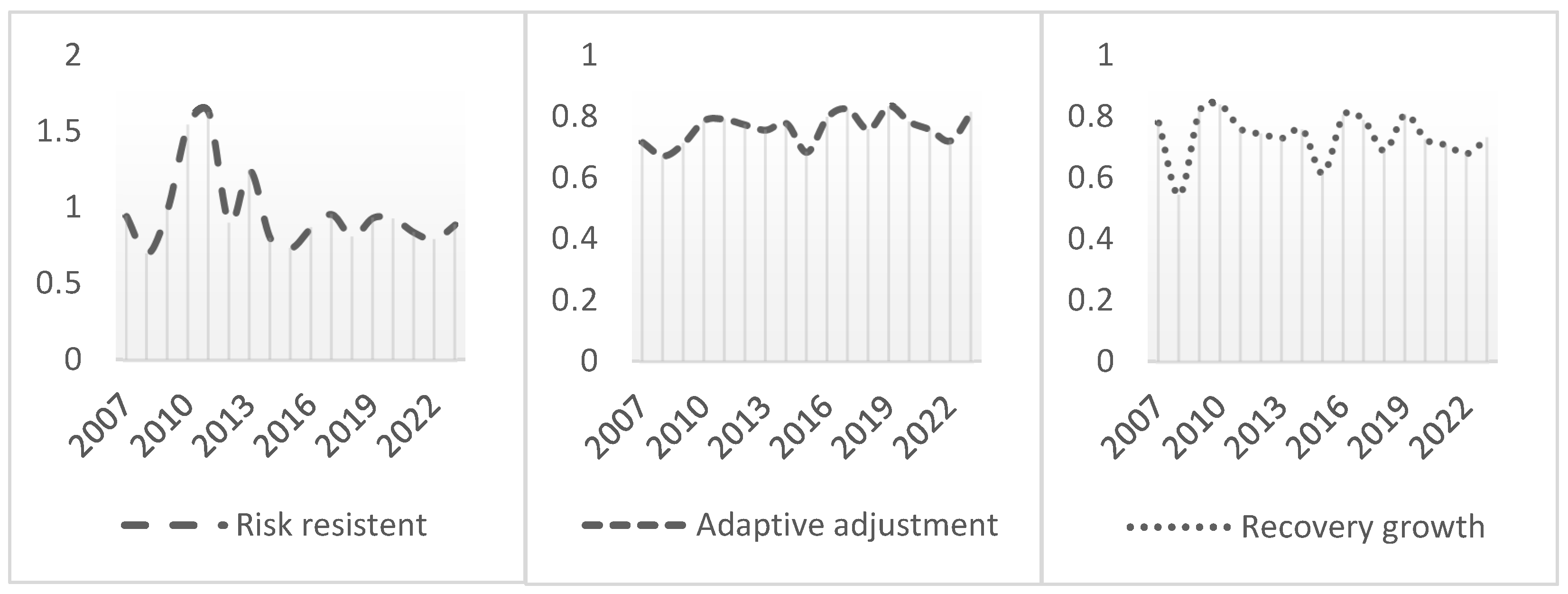

3.3.1. Trend Analysis of Corporate Resilience

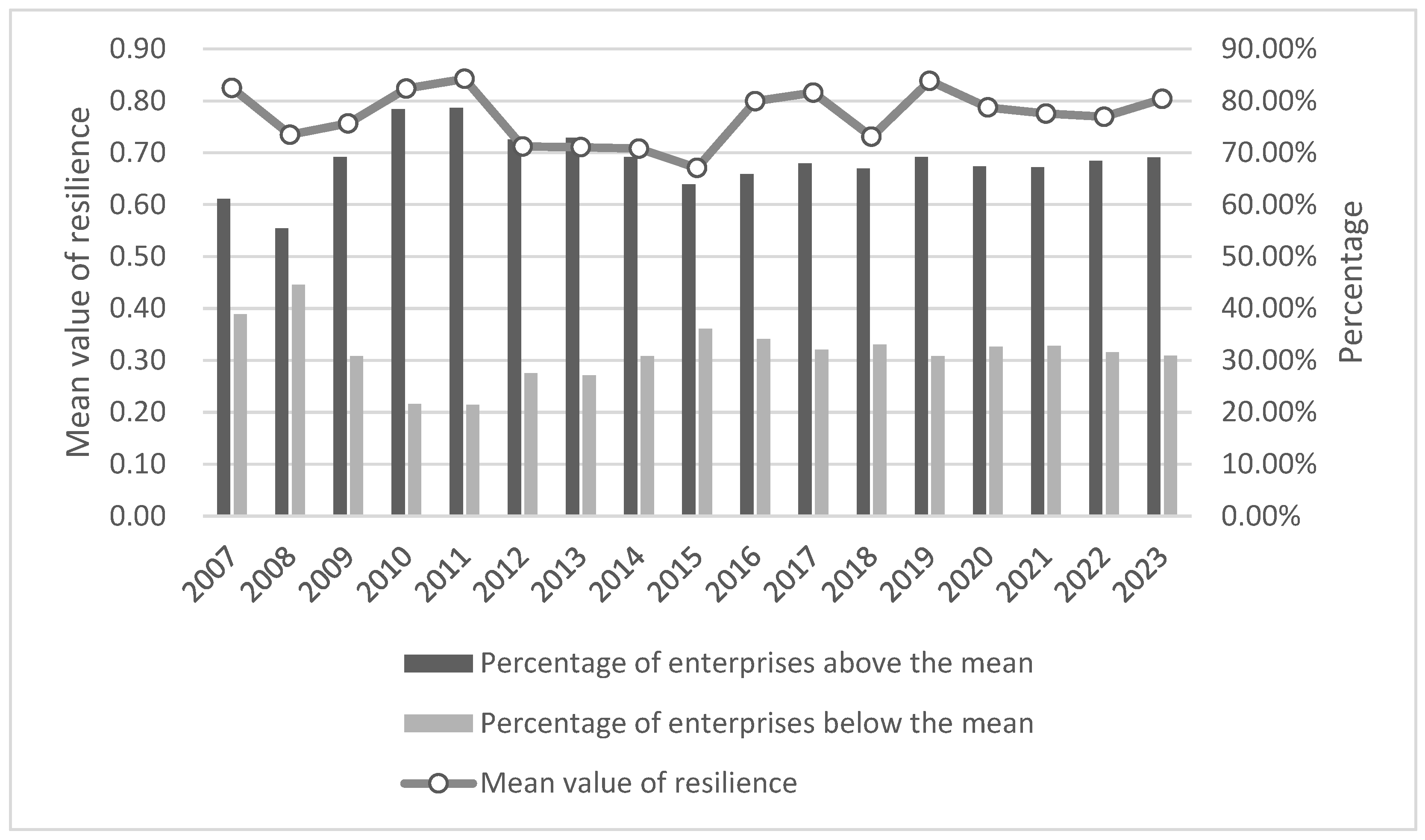

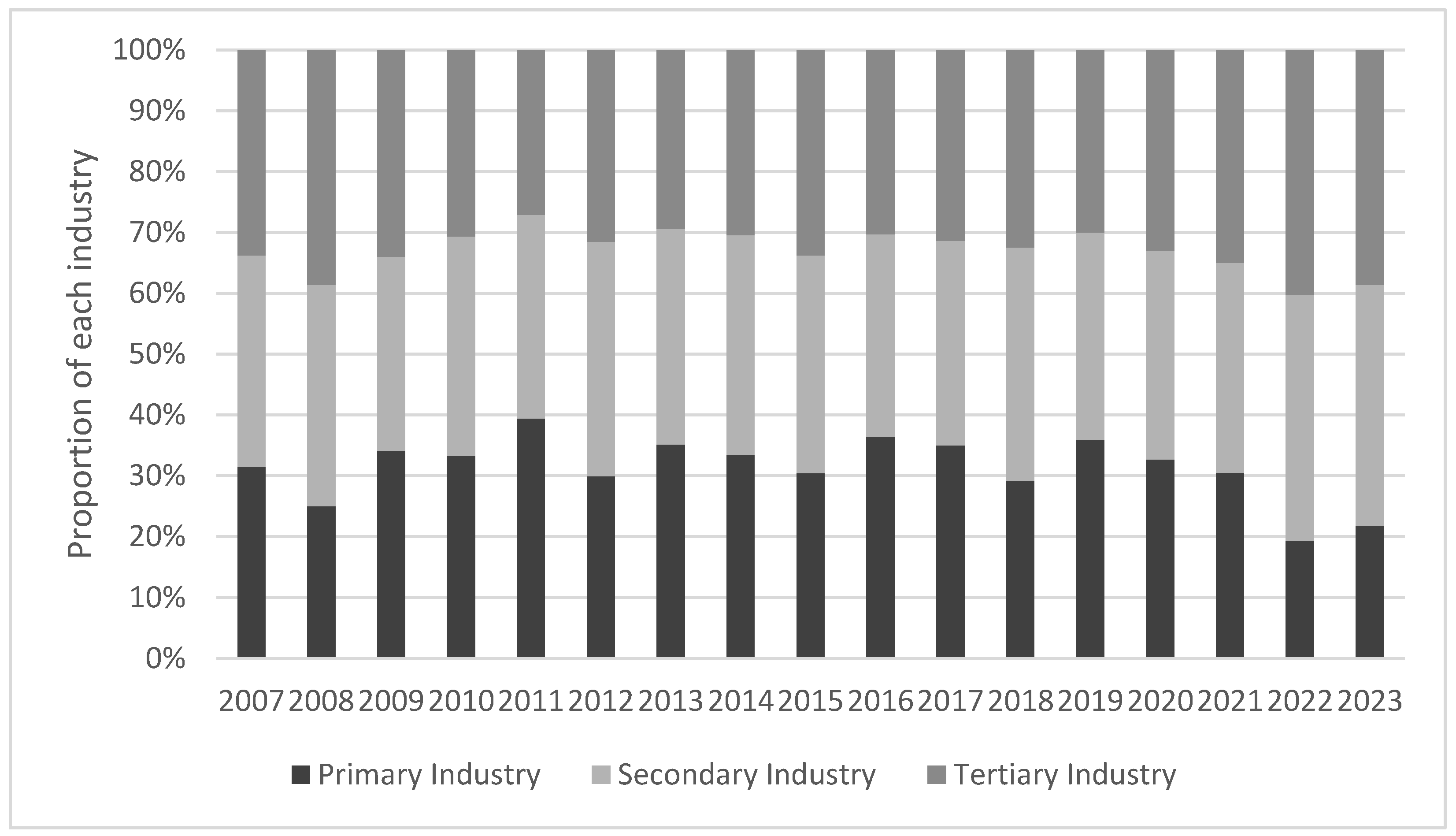

3.3.2. Distributional Analysis of Low-Resilience Enterprises

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Recommendations

4.3. Discussion and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.P.; Peng, J.; Huang, X.F. Export Experience and Firms’ OFDI. Econ. Rev. 2024, 2, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.L.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, J.Q. The Spatiotemporal Convergence and Divergence, Heterogeneous Differentiation Characteristics of Economic Resilience in China: Identification Based on a Markov Switching Mixed-Frequency Dynamic Factor Model. J. Manag. World 2024, 40, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlenbrach, R.; Rageth, K.; Stulz, R.M. How Valuable Is Financial Flexibility When Revenue Stops? Evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 34, 5474–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhu, Z.Y. Exploratory Innovation and Firm Resilience—Evidence from NEEQ Listed Companies. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, S.J. The Impact of Digital Transformation on Firm Resilience: Evidence From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.M.; Zhao, L.; Chen, W.Z. A Study on the Mechanism and Effect of Heterogeneity Characteristics of Senior Management Teams in Listed Companies on Organisational Resilience. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 43, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M.; Bansal, P.; Yang, Y. Bouncing Back: Building Resilience Through Social and Environmental Practices in the Context of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.F.; Song, X.X.; Dou, B. The Value of Digitalization in Times of Crisis: Evidence of Corporate Resilience. Financ. Trade Econ. 2022, 43, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.V.; Vargo, J.; Seville, E. Developing a Tool to Measure and Compare Organizations’ Resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2013, 14, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ling, Y.P.; Zhang, J.C.; Lu, J.F. How Does Digital Transformation Affect Firm’s Resilience? An Ambidexterous Innovation View. J. Technol. Econ. 2022, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.E.; Teng, X.Y. The Connotation, Dimensions and Measurement of Organizational Resilience. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2021, 38, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.N.; Cui, D.F. Evaluation Index System and Quantitative Analysis of Corporate resilience. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2023, 42, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Li, Y. The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Organizational Resilience on Product Cost Advantage of Manufacturing Enterprises. China Bus. Mark. 2024, 38, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological Resilience—In Theory and Application. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Barnes, G.; Perz, S.; Schmink, M.; Sieving, K.E.; Southworth, J.; Binford, M.; Holt, R.D.; Stickler, C.; Van Holt, T. An Exploratory Framework for the Empirical Measurement of Resilience. Ecosystems 2005, 8, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Long, J.; Ling, Y.P.; Jiang, L. Thriving Against the Odds: A Review and Outlook on Corporate Resilience Research. Manag. Mod. 2021, 41, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.H.; Liu, D.; Qu, H.S. Research on Factors of the Survival of Backdoor-listed Companies. J. Yanbian Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2020, 53, 85–92+142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tan, S.Q. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Resilience Innovation. Enterp. Econ. 2022, 41, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Levine, R.; Lin, C.; Xie, W. Corporate Immunity to the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 141, 802–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guo, T.M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q.Y. Research on the Impact of Internal Control on Organizational Resilience—Based on the Perspective of Corporation Lifecycle. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.J.; Hu, H.G.; Zhang, S.S.; Sun, L. Supply Chain Digitalization and Firm Performance: Mechanism and Empirical Evidence. Bus. Manag. J. 2023, 45, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, Y.; Feng, T.; He, J.; Dong, Z. Research on the Relationship Between Structural Characteristics of Corporate Social Networks and Risk-Taking Levels: Evidence from China. Systems 2025, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, F. Unlocking Corporate Sustainability: The Transformative Role of Digital–Green Fusion in Driving Sustainable Development Performance. Systems 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Rodriguez-Espindola, O.; Dey, P.; Budhwar, P. Blockchain Technology Adoption for Managing Risks in Operations and Supply Chain Management: Evidence from the UK. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 539–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, S.A.; Rozanova, T.P.; Bezpalov, V.V.; Fedyunin, D.V. Supply Chain Management and Risk Management in an Environment of Stochastic Uncertainty (Retail). Risks 2021, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Ali, A.; Khattak, M.S.; Arfeen, M.I.; Chaudhary, M.A.I.; Syed, A. Strategic Flexibility and Organizational Performance: Mediating Role of Innovation. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231181432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhong, J.Y. Effect of Corporate Governance on Digital Transformation. Enterp. Econ. 2023, 42, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.W.; Zhang, L.L.; Wang, C. Digital Transformation and Corporate Resilience: Empirical Evidence from Chinese A-Share Listed Corporations. Reform 2024, 5, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.J.; Xia, Y.X.; Xue, L.D. Construction, Measurement and Testing of Corporate resilience Index: Based on Data from A-Share Listed Companies. Sci. Decis. Mak. 2024, 3, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mgammal, M.; Al-Matari, E. Dataset of Companies’ Profitability, Government Debt, Financial Statements’ Key Indicators and Earnings in an Emerging Market: Developing a Panel and Time Series Database of Value-Added Tax Rate Increase Impacts. F1000Research 2023, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Li, Y. The Double-edged Sword Effect of Organizational Resilience on ESG Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2852–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Cai, C. Comprehensive Evaluation of High-Quality Development in China Based on Multi-Level Factor Analysis. Stat. Decis. 2022, 38, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, A.; Mazzitelli, A. Dynamic Factor Analysis with STATA. In Proceedings of the 2nd Italian Stata Users Group Meeting, Milano, Italy, 10 October 2005; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.; Hu, Y. Prediction on Chinese Business Climate Index and Entrepreneur Confidence Index. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks: An Analysis of the Exogenous COVID-19 Market Crash. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, Q.R. A Time-varying Estimation and Decomposition of the Long-term Trend on China‘s Economic Growth. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2022, 39, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, X.D. Corporate Governance and Stock Price Stability in the Market Crisis: Based on Empirical Evidence from the 2015Stock Market Crash. Macroeconomics 2021, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Thurasamy, R. Bridging Big Data Analytics Capability and Competitive Advantage in China’s Agribusiness: The Mediator of Absorptive Capacity. Systems 2025, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Dong, H.; Farzaneh, H.; Geng, Y.; Reddington, C.L. Uncovering the Overcapacity Feature of China’s Industry and the Environmental & Health Co-Benefits from de-Capacity. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Ran, L.J. Domestic Circulation and Industrial Chain Resilience. J. Beijing Technol. Bus. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, S.-H.; Shi, H. Exploring the Spatial Agglomeration Characteristics and Determinants of Strategic Emerging Industries: Evidence from 12,979 Industrial Enterprises in China. Systems 2025, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.M. Inter-regional Industrial Transfer and Regional Economic Gap. Econ. Surv. 2021, 38, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Duan, D.; Feng, Z. The Impact of New Quality Productive Forces on the High-Quality Development of China’s Foreign Trade. Systems 2025, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Causality | Indicator | Calculation Method | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Resistance Capability | Financial Stability | Current Ratio | Current Assets/Current Liabilities | + |

| Quick Ratio | (Current Assets − Inventories)/Current Liabilities | + | ||

| Cash Ratio | Ending Balance of Cash and Cash Equivalents/Current Liabilities | + | ||

| Retained Earnings Ratio | Ending Retained Earnings/Ending Total Assets | + | ||

| Market Stability | Individual Stock Lerner Index | (Operating Revenues − Operating Costs − Selling Expenses − Administrative Expenses)/Operating Revenues | + | |

| Stock Price Growth Margin | (Highest Stock Price during the Year − Lowest Stock Price during the Year)/Highest Stock Price during the Year | + | ||

| Stock Price Volatility | Standard Deviation of Month-End Stock Earnings during the Year | + | ||

| Risk Prevention | Equity to Debt Ratio | Total Owners’ Equity/Total Liabilities | + | |

| Financial Leverage | (Net Income + Income Tax Expense + Finance Cost + Depreciation of Fixed Assets, Depreciation of Oil and Gas Assets, Depreciation of Producing Biological Assets + Amortization of Intangible Assets + Amortization of Long-Term Amortization Expenses)/(Net Income + Income Tax Expense + Finance Cost) | − | ||

| Operating Leverage | (Net Income + Income Tax Expense + Finance Cost)/(Net Income + Income Tax Expense) | − | ||

| Balance Sheet Ratio | Total Liabilities/Total Assets | − | ||

| Adaptive Adjustment Capacity | Resource Allocation | Financial Expense Ratio | Financial Expenses/Operating Income | − |

| Administrative Expense Ratio | Administrative Expenses/Operating Income | − | ||

| Return on Investment | Investment Income/(Long-Term Equity Investments at the End of the Period + Held-to-Maturity Investments at the End of the Period + Financial Assets Held for Trading at the End of the Period + Available-for-Sale Financial Assets at the End of the Period + Derivative Financial Assets at the End of the Period) | + | ||

| Environmental Adaptability | Downstream Bargaining Power | Cash Received From the Sale of Goods and Rendering of Services/Operating Income | + | |

| Upstream Bargaining Power | Cash Paid for Purchases of Goods and Receiving of Services/Cost of Main Operations | + | ||

| Relative Bargaining Power in the Industrial Chain | Accounts Payable/Accounts Receivable | + | ||

| Customer Concentration | Ratio of Sales from Top Five Customers to Total Annual Sales | - | ||

| Supplier Concentration | Ratio of Purchases from Top Five Suppliers to Total Annual Purchases | − | ||

| Governance Structure | Average Age of Executives | Total Age/Number of Executives | + | |

| Average Reported Compensation of Executives | Total Executive Compensation/Number of Executives | + | ||

| Average Compensation of Employees | (Compensation Payable for the Current Year − Compensation Payable for the Previous Year + “Cash Paid To and On Behalf of Employees” in the Statement of Cash Flows − Total Annual Remuneration of Directors and Supervisors)/Number of Employees Other Than Management | + | ||

| Number of Shareholder Meetings | Number of General Meetings of Shareholders in a Year | + | ||

| Recovery Growth Capacity | Profitability | Net Operating Margin | Net Profit/Operating Income | + |

| Cash to Total Profit Ratio | (Net Cash Flows from Operating Activities)/(Total Profit) | + | ||

| Cost–Expense Margin | Total Profit/(Operating Costs + Taxes and Surcharges + Selling Expenses + Administrative Expenses + Financial Expenses + R&D Expenses) | + | ||

| Recovery Speed | Accounts Receivable Turnover | Operating Income/Accounts Receivable Ending Balance | + | |

| Accounts Payable Turnover | Operating Costs/Accounts Payable Closing Balance | − | ||

| Fixed Asset Turnover | Operating Income/Net Fixed Assets Ending Balance | + | ||

| Inventory Turnover | Operating Costs/Inventory Ending Balance | + | ||

| Working Capital Turnover | Operating Income/Working Capital | + | ||

| Growth Potential | Return on Net Assets | Net Profit/Shareholders’ Equity | + | |

| Growth Rate of Total Assets | (Total Assets at the End of the Period − Total Assets at the Beginning of the Period)/Total Assets at the Beginning of the Period | + | ||

| Sustainable Growth Rate | (Net Income/Total Owners’ Equity Closing Balance of the Period) × [1 − Pre-Tax Dividend per Share/(Current Value of Net Income/Current Value of Paid-in Capital Closing Balance of the Period)]/(1 − Numerator a) | + | ||

| Capital Preservation and Appreciation Ratio | (Closing Value of Total Owners’ Equity for the Period − Opening Value of Total Owners’ Equity for the Period)/Opening Value of Total Owners’ Equity for the Period | + |

| Risk Resistance | Adaptive Adjustment | Recovery Growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues | Variability | Eigenvalues | Variability | Eigenvalues | Variability |

| 3.396 | 37.728 | 1.696 | 24.227 | 6.747 | 51.901 |

| 3.219 | 35.753 | 1.254 | 17.912 | 1.813 | 13.948 |

| 0.993 | 11.036 | 1.218 | 17.393 | 1.071 | 8.237 |

| 0.582 | 6.460 | 1.059 | 15.128 | 0.990 | 7.619 |

| 0.480 | 5.329 | 0.751 | 10.730 | 0.933 | 7.179 |

| 0.199 | 1.320 | 0.718 | 10.251 | 0.573 | 4.406 |

| Principal Component | Eigenvalues | Variability | Cumulative Variability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.362 | 80.249 | 80.249 |

| 2 | 0.479 | 16.266 | 96.514 |

| 3 | 0.103 | 3.486 | 100.000 |

| Crisis Event | Group | t − 1 | t | t + 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Crisis | Low | 196 | 0.1727 | 201 | 0.1577 | 203 | 0.1350 |

| High | 196 | 0.2381 | 201 | 0.2312 | 203 | 0.3552 | |

| T-value | T = 2.4311 ** | T = 2.2696 ** | T = 2.8554 *** | ||||

| Stock Market Crash | Low | 215 | 0.1336 | 224 | 0.1065 | 245 | 0.1684 |

| High | 215 | 0.2244 | 224 | 0.2121 | 245 | 0.2048 | |

| T-value | T = 3.8202 *** | T = 2.5056 ** | T = 1.2721 | ||||

| Trade Conflict | Low | 274 | 0.1600 | 279 | 0.2004 | 296 | 0.2174 |

| High | 274 | 0.2818 | 279 | 0.2793 | 296 | 0.3538 | |

| T-value | T = 4.9572 *** | T = 2.9407 *** | T = 2.8879 *** | ||||

| COVID-19 | Low | 296 | 0.2174 | 324 | 0.2046 | 360 | 0.3166 |

| High | 296 | 0.3538 | 324 | 0.3526 | 360 | 0.4753 | |

| T-value | T = 2.8879 *** | T = 3.4611 *** | T = 3.3848 *** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheng, C.; Li, J. Measuring Corporate Resilience Using Dynamic Factor Analysis: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Systems 2025, 13, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070575

Sheng C, Li J. Measuring Corporate Resilience Using Dynamic Factor Analysis: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Systems. 2025; 13(7):575. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070575

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheng, Chunguang, and Jingyan Li. 2025. "Measuring Corporate Resilience Using Dynamic Factor Analysis: Evidence from Listed Companies in China" Systems 13, no. 7: 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070575

APA StyleSheng, C., & Li, J. (2025). Measuring Corporate Resilience Using Dynamic Factor Analysis: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Systems, 13(7), 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070575