Abstract

This study explores the influence of team communication (TC) and shared mental models (SMMs) on entrepreneurial team efficacy (ETE) within the context of Chinese higher education, introducing a dual-path model to reconcile the discrepancy between policy expectations and practical outcomes in entrepreneurship education. Utilizing partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) on data from 475 university-based questionnaires from March to May in 2024 in China, the research reveals that structured internal communication significantly enhances the alignment of learning goals, teammate cognition, and activity synchronization, thereby fostering SMMs as a pivotal psychological infrastructure. The findings indicate that shared learning goals and cognitive convergence are primary drivers of task performance, whereas coordinated activity states are more influential in strengthening relational cohesion. The study challenges the conventional “communication frequency–efficacy paradox” by demonstrating distinct pathways through which internal and external communication mechanisms differentiated impact task and relational outcomes. Additionally, demographic analyses highlight that team maturity and age diversity positively correlate with task efficacy, while gender and disciplinary heterogeneity show no significant association. Theoretically, this research advances the understanding of team collaboration dynamics and contextualizes Western entrepreneurship theories within China’s collectivist framework. Practically, it provides robust, evidence-based strategies for refining communication protocols and enhancing both collaborative efficiency and innovation in entrepreneurial education settings.

1. Introduction

Amid a century of unprecedented technological disruption, youth employment has crystallized as a critical global socioeconomic challenge [1,2]. Structural unemployment is particularly pronounced in emerging economies, especially in countries where education systems are expanding rapidly without matching labor market absorption capacities [3]. In recent years, China’s higher education system has witnessed remarkable expansion, with the number of graduates from regular universities climbing from 7.49 million in 2015 to 11.58 million in 2023 [4]. Despite this growth, the youth unemployment rate has consistently exceeded 20% [5]. Against this backdrop, entrepreneurship education has been elevated to a national strategic priority [3,6]. However, a significant gap remains between policy aspirations and practical achievements. While entrepreneurship course coverage has improved, embarking on an entrepreneurial journey entails a significant incidence of failure [7]. Thus, Chinese college students exhibit low levels of intention to start businesses, and the entrepreneurial team efficacy (ETE) index among Chinese students trails in a low level compared to their European and American counterparts [8].

This paradox may stem from the unique generational attributes of China’s new-wave entrepreneurs. As “Millennials” (born 1995–2010) shaped by the One-Child Policy, their developmental trajectories are marked by three structural tensions: (i) only child syndrome engendering collaborative capital deficits, with experimental evidence showing lower conflict resolution capacity in team tasks compared to non-only child peers [9]; (ii) digital nativity manifested through 5 h daily screen time [10], where overreliance on asynchronous tools (e.g., WeChat) erodes nonverbal cue interpretation critical for co-located collaboration; and (iii) a predisposition for risk-aversion, with most Chinese graduates prioritizing job security over entrepreneurial ventures [11], fundamentally clashing with the collective risk-taking imperative inherent in startup ecosystems.

While entrepreneurship education is globally recognized as a key solution to youth employment challenges, existing research exhibits significant theoretical gaps in understanding team collaboration mechanisms. Most studies focus on individual entrepreneurial skills (e.g., business planning, financing strategies) and course coverage improvements [12,13,14], neglecting the inherently team-driven complexity of innovation. This limitation is particularly pronounced in non-Western contexts, where Western individualistic entrepreneurship theories (e.g., Minniti’s opportunity recognition model) fail to explain how cultural conflicts, such as “face” and decision transparency, suppress team efficacy in collectivist settings like China. Furthermore, research on team cognitive synergy mechanisms remains underdeveloped, with insufficient exploration of the dynamic interplay between communication architectures and shared mental models, as well as the disruptive impact of digital natives’ generational traits on traditional collaboration frameworks.

This study investigates the impact of team communication (TC) and shared mental models (SMMs) on ETE within the context of Chinese university entrepreneurship education. Drawing on valid questionnaire data from 475 university-based entrepreneurial teams in China, we employ partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to delineate the mechanisms through which team communication influences SMMs and subsequently enhances ETE. The analysis demonstrates that structured internal communication significantly strengthens the alignment of learning goals, teammate cognition, and activity synchronization, thereby catalyzing SMM formation—a critical psychological infrastructure mediating team outcome. These SMM components differentially predict effectiveness: shared learning goals and cognitive convergence predominantly drive task performance, while coordinated activity states more substantially enhance relational cohesion. Mediation pathways reveal internal communication’s superior indirect effect on task outcomes versus external communication’s relational emphasis. Demographic analyses identify developmental trajectories, with team maturity and age diversity positively associated with task efficacy, while gender composition and disciplinary heterogeneity prove non-significant. This study makes three primary contributions to the extant literature.

First, in theoretical advancement, we develop a novel framework integrating team communication with SMMs, establishing communication’s pivotal role in shaping collective cognition. While prior scholarship predominantly emphasizes individual-level entrepreneurial skill cultivation and curriculum coverage [12,13], our framework elucidates the complex dynamics of team collaboration, particularly its innovative dimensions in entrepreneurial contexts. By delineating the logical interdependence between communicative processes and cognitive synchronization, this research provides novel theoretical insights into team coordination mechanisms.

Second, we re-conceptualize the contingent transmission pathways of team communication strategies. Addressing the persistent “communication frequency–efficacy paradox” in team interaction [15,16], our study transcends conventional linear assumptions by demonstrating differential impact pathways: internal communication predominantly enhances task execution through cognitive calibration mechanisms, whereas external communication fortifies team cohesion via relational network reinforcement. This dual-path model establishes topological rationale for designing hybrid virtual–physical communication strategies in digital-era entrepreneurship education, revealing the asymmetric efficacy of structured communication in achieving cognitive alignment versus relational maintenance.

Finally, our findings yield concrete strategic implications for optimizing innovation pedagogy. The empirically validated interdependence between communicative patterns and shared mental models provides actionable guidance for Chinese higher education policymakers and practitioners. Specifically, we propose evidence-based interventions for cultivating structured communication protocols and institutionalizing cognitive synchronization processes, thereby enhancing both collaborative efficiency and innovative capacity in team-based entrepreneurial learning environments. This tripartite contribution bridges critical theoretical gaps while offering pragmatic solutions tailored to China’s distinctive educational ecosystem.

The subsequent sections are structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical evolution of team communication and shared mental models in entrepreneurial education, identifies research gaps, and proposes hypotheses. Section 3 details the research methodology, including participant selection, instrument validation, data collection, and analysis strategies. Section 4 presents empirical results, assessing the measurement model’s reliability and validity and testing hypotheses through structural equation modeling to reveal how team communication affects entrepreneurial team efficacy via shared mental models. Section 5 discusses findings, theoretical contributions, and practical implications, proposes educational interventions, addresses study limitations, and suggests future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background

Entrepreneurship, functioning as a core engine of economic growth and societal innovation, is fundamentally characterized by value fission achieved through resource recombination and opportunity creation [17]. Against the backdrop of global economic digitalization, entrepreneurial activities have not only catalyzed emergent technologies and industrial paradigms [18] but also emerged as a strategic countermeasure to structural unemployment worldwide, owing to their capacity to generate employment, optimize resource allocation, and stimulate regional economic vitality [19]. In China, the accelerated implementation of the “Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation” policy has further elevated entrepreneurship to a pivotal role in higher education reform. However, a striking implementation gap persists: while entrepreneurship course coverage in universities has reached 82.5% [20], the actual youth entrepreneurship rate remains stagnant at 2.8%. This dissonance underscores an adaptive crisis between conventional pedagogical frameworks and the complexities of contemporary entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Entrepreneurship education research has evolved through three major paradigms: individual skill orientation [6], curriculum optimization [12], and policy effectiveness evaluation [21]. There is now a consensus that entrepreneurship education must transcend mere business knowledge transmission and instead construct a three-dimensional capability system that encompasses opportunity identification [22], risk-taking [23], and resource integration [24]. Cross-national comparative studies have revealed a significant positive correlation between the maturity of university entrepreneurship ecosystems and regional innovation indices [25], while individual attitudes toward entrepreneurship have been found to be a key moderating variable in responding to educational interventions [26]. However, two major theoretical gaps persist in the existing literature: First, there is an overemphasis on linear individual skill acquisition at the micro level, such as business plan drafting, while the inherent complexity of teamwork in entrepreneurial behavior is overlooked [27]. Second, the “opportunity-resource” model, constructed based on Western individualistic cultures (such as the Minniti theory), struggles to explain the mediating role of team cognitive synergy mechanisms [28] in ETE.

2.1. Team Communication (TC), Shared Mental Models (SMMs), and Entrepreneurial Team Efficacy (ETE)

2.1.1. Team Communication (TC) and Shared Mental Models (SMMs)

TC, a core mechanism for information, idea, and emotion exchange in entrepreneurial teams, comprises two key dimensions: team internal communication (ITC) and team external communication (TEC). ITC involves team members sharing information and ideas openly and effectively, expressing diverse opinions and feedback, and ensuring all members can participate in decision-making and be seriously considered. This mechanism not only facilitates information flow but also deepens mutual understanding and trust, laying the foundation for SMMs [29,30]. TEC, on the other hand, refers to the team’s interaction with external teams, experts, and resources, including information acquisition, feedback integration, and resource coordination [31,32].

SMMs represent the collective psychological framework and cognitive structure among team members. They reveal the shared nature of implicit cognition and provide deep insights into enhancing team effectiveness [33,34]. SMMs encompass task-related and team-related content: the former includes learning willingness sharing (LWS) and task understanding sharing (TUS), while the latter involves teammate cognitive sharing (TCS) and active state sharing (ASS). These constructs collectively drive team performance and innovation outcomes [35]. Research indicates that team communication is critical for forming SMMs. Effective communication fosters information sharing and cognitive consistency among team members, thereby enhancing collaboration efficiency and capability [29,30].

ITC, as a core mechanism for exchanging information, ideas, and emotions, has a significantly positive impact on promoting shared learning willingness, shared task understanding, shared teammate cognition, and shared activity state awareness among team members. Specifically, effective ITC can stimulate members’ motivation to learn, enhance their in-depth understanding of team tasks, promote mutual recognition of members’ traits, and improve synchronized awareness of activity status. These shared constructs are not only key aspects of improving team effectiveness but are also interrelated and jointly influential on the team’s overall performance and the realization of innovation outcomes. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

- H1a: ITC has a positive impact on LWS.

- H1b: ITC has a positive impact on TUS.

- H1c: ITC has a positive impact on TCS.

- H1d: ITC has a positive impact on ASS.

TEC, namely interactions between students and individuals outside the campus, may also enhance LWS, TUS, TCS, and ASS among team members. Specifically, TEC can bring new perspectives and knowledge to team members, sparking their interest in learning and thereby strengthening LWS within the team. At the same time, interactions with external experts help team members understand tasks from a broader perspective and form a shared understanding of tasks. Additionally, TEC promotes members’ understanding and recognition of teammates’ traits by showcasing team diversity and individual differences, thereby enhancing TCS. Finally, TEC makes team members more sensitive to industry trends and changes in the external environment, which aids in shared understanding of activity status and allows for timely adjustments to work pace and direction. In summary, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

- H1e: TEC has a positive impact on LWS.

- H1f: TEC has a positive impact on TUS.

- H1g: TEC has a positive impact on TCS.

- H1h: TEC has a positive impact on ASS.

2.1.2. Shared Mental Models (SMMs) and Entrepreneurial Team Efficacy (ETE)

The construct of ETE remains multifaceted in academic discourse. Cooney (2004) conceptualizes it as “the tangible outcomes of a team’s pursuit of predefined objectives”, [36] measurable through three dimensions: (1) task accomplishment, (2) member satisfaction, and (3) the team’s capacity for sustained collaboration. Expanding this perspective, Cole et al. (2013) argue that team effectiveness should integrate performance outcomes, attitudinal alignment, and behavioral outputs [37]. Contemporary scholarship further distinguishes between task effectiveness (goal-centric achievements) and contextual effectiveness (emergent qualities like cohesion and adaptive norms) to capture both direct and indirect contributions to organizational success [38,39]. Aligning with China’s pedagogical emphasis on collaborative innovation in entrepreneurship education, this study defines team effectiveness as “the collective achievements derived from coordinated efforts among members to fulfill practice-oriented learning objectives”. Given the unique cultural and educational priorities of Chinese higher education—where team cohesion and individual growth are institutionalized as dual drivers of long-term success—we operationalize effectiveness through two dimensions:

- (1)

- Team Task Effectiveness (TTE):

The degree to which teams meet or exceed predefined standards in executing innovation projects, assessed through

Task completion rates.

Operational efficiency (e.g., time/resource optimization).

Output quality (e.g., prototype viability, business plan rigor).

- (2)

- Team Relationship Effectiveness (TRE):

The social emotional infrastructure enabling sustained collaboration, measured via

Member satisfaction indices.

Individual skill development trajectories.

Willingness to engage in future joint ventures.

On the one hand, SMMs may positively influence TTE. LWS can stimulate team knowledge accumulation and innovation, thereby enhancing the team’s ability to complete tasks. TUS, which refers to a common grasp of the task’s nature and implementation methods among team members, helps clarify goals and devise effective strategies, improving team work efficiency and the quality of outcomes. TCS, involving an understanding of individual team members’ characteristics, can build trust and foster effective communication, boosting team collaboration efficiency. ASS, which is the collective awareness of task progress and work rhythm among team members, helps maintain team synchronization and allows for timely work adjustments, reducing confusion during task execution. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H1i: LWS has a positive impact on TTE.

- H1j: TUS has a positive impact on TTE.

- H1k: TECS has a positive impact on TTE.

- H1l: ASS has a positive impact on TTE.

On the other hand, SMMs may significantly enhance TRE. LWS boosts team cohesion and member satisfaction, fostering a positive attitude toward learning and growth. TUS aligns team members’ perceptions of goals, reducing conflicts and solidifying team stability. TCS builds trust through mutual understanding of members’ traits, optimizing task allocation and enhancing emotional support. ASS minimizes uncertainty and anxiety by keeping members informed about progress, thereby strengthening confidence and collaborative intent. These elements collectively elevate TRE by promoting harmonious interactions and emotional bonds within the team. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H1m: LWS positively impacts TRE.

- H1n: TUS positively impacts TRE.

- H1o: TCS positively impacts TRE.

- H1p: ASS positively impacts TRE.

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Team Communication (TC)

Given the complexity of the impact of TC on ETE, the single-path hypothesis, while revealing the direct effects of internal team communication (ITC) on the dimensions of shared mental models (learning willingness sharing (LWS), task understanding sharing (TUS), teammate cognition sharing (TCS), and activity status sharing (ASS)), as well as the direct effects of these SMM dimensions on team task effectiveness (TTE) and team relationship effectiveness (TRE), fails to adequately explain how ITC indirectly affects TTE and TRE through these SMM dimensions. Therefore, integrating the single-path hypotheses proposed in this paper (H1a-H1d and H1i-H1p), the following mediating effect hypotheses are proposed:

- H2a: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through LWS (based on H1a and H1i).

- H2b: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through TUS (based on H1b and H1j).

- H2c: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through TCS (based on H1c and H1k).

- H2d: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through ASS (based on H1d and H1l).

- H2e: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through LWS (based on H1a and H1m).

- H2f: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through TUS (based on H1b and H1n).

- H2g: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through TCS (based on H1c and H1o).

- H2h: ITC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through ASS (based on H1d and H1p).

Additionally, TEC, as a critical means of interaction between the team and its external environment, can bring new information, knowledge, and resources to the team, thereby influencing shared mental models and overall team effectiveness. According to the single-path hypothesis, TEC has varying degrees of impact on learning willingness sharing (LWS), task understanding sharing (TUS), teammate cognition sharing (TCS), and activity status sharing (ASS) (H1e-H1h), and these dimensions of shared mental models further influence team task effectiveness (TTE) and team relationship effectiveness (TRE) (H1i–H1p). Therefore, integrating the single-path hypotheses (H1e–H1h and H1i–H1p), the following mediating effect hypotheses are proposed:

- H2i: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through LWS (based on H1e and H1i).

- H2j: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through TUS (based on H1f and H1j).

- H2k: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through TCS (based on H1g and H1k).

- H2l: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TTE through ASS (based on H1h and H1l).

- H2m: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through LWS (based on H1e and H1m).

- H2n: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through TUS (based on H1f and H1n).

- H2o: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through TCS (based on H1g and H1o).

- H2p: TEC has a positive indirect effect on TRE through ASS (based on H1h and H1p).

2.3. The Total Effect Hypotheses

Based on the comprehensive impact of TC on ETE, and integrating the results of the single-path and mediating effect hypotheses, the following overall effect hypotheses are proposed:

- H3a: ITC has a positive overall effect on TTE (based on H1i–H1l and H2a–H2d).

- H3b: ITC has a positive overall effect on TRE (based on H1m–H1p and H2e–H2h).

- H3c: TEC has a positive overall effect on TTE (based on H1i–H1l and H2i–H2l).

- H3d: TEC has a positive overall effect on TRE (based on H1m–H1p and H2m–H2p).

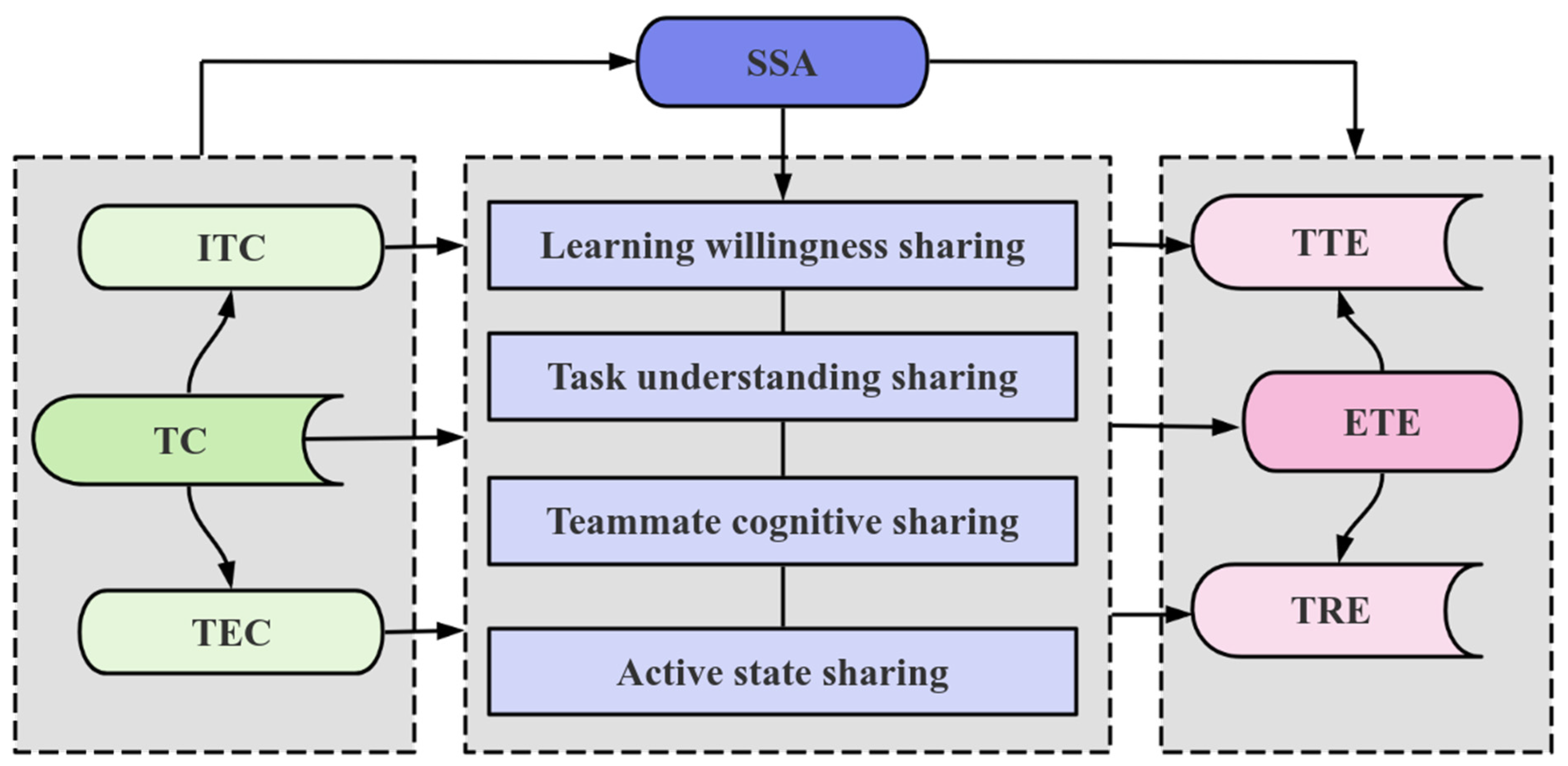

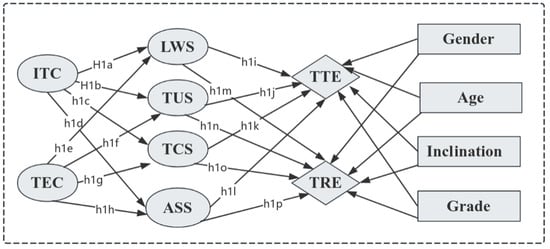

Figure 1 delineates the structural relationships among the core constructs of this study.

Figure 1.

The structural relationships among the core constructs.

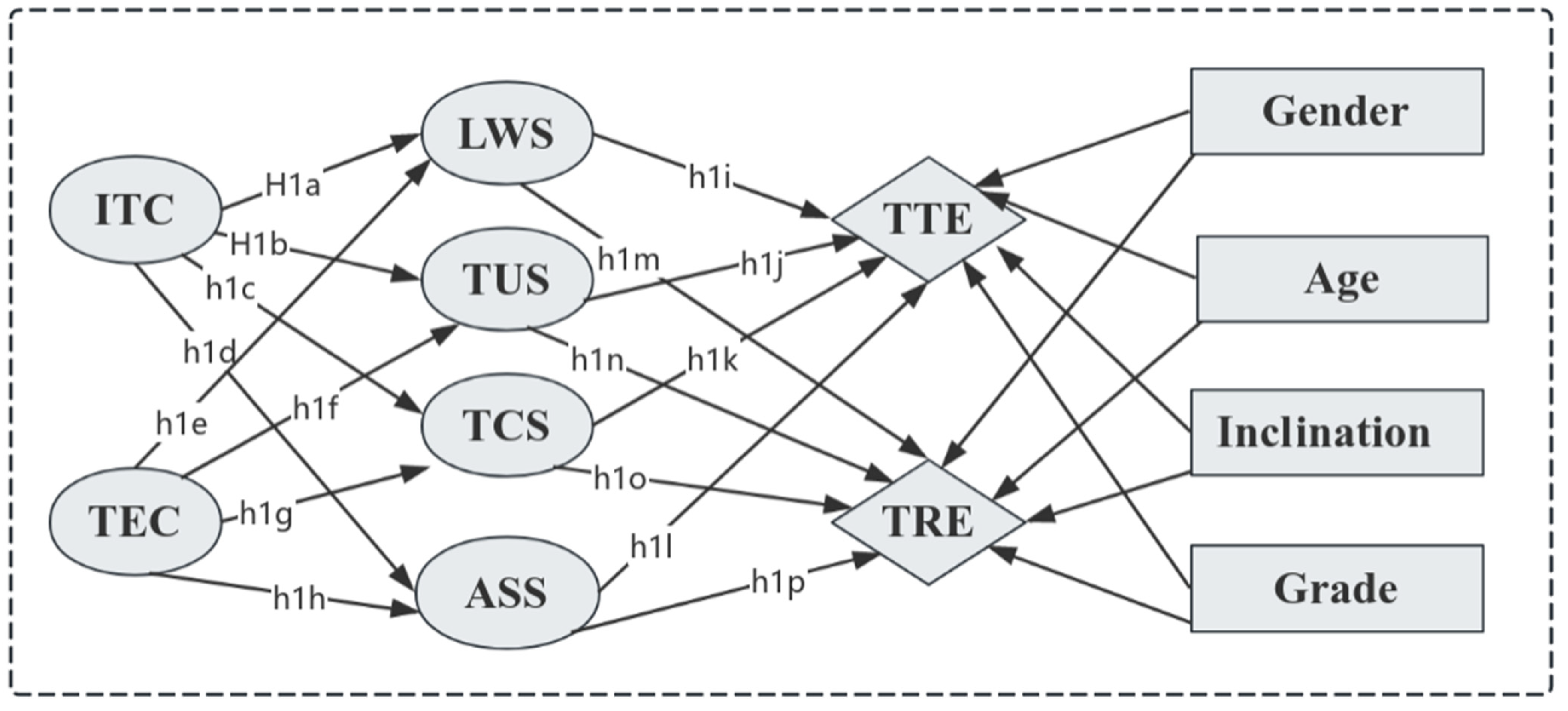

This study intends to conduct empirical research on Chinese college students’ participation in entrepreneurship education. Specifically, it aims to investigate the relevant circumstances and collect data to examine the effects of team communication and shared mental models on team effectiveness, as well as to evaluate the moderating role of demographic characteristics. Based on the research objectives and hypotheses outlined earlier, eight core constructs were identified: intra-team communication (ITC), team external communication (TEC), learning willingness sharing (LWS), task understanding sharing (TUS), teammate cognitive sharing (TCS), active state sharing (ASS), team task effectiveness (TTE), and team relationship effectiveness (TRE). Additionally, four demographic characteristics were incorporated into the research framework, designed based on the unique attributes of college students: gender (coded as 0 for male and 1 for female), age, academic inclination (coded as 0 for humanities/social sciences and 1 for natural sciences), and grade. The conceptual model of this study is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The conceptual model of this study.

3. Methodology

This study employs partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to address its dual requirements of modeling complex theoretical nexuses and managing inherent measurement constraints. The methodology’s superiority over conventional techniques (e.g., ANOVA, regression) lies in its capacity to simultaneously estimate hierarchical mediation effects through integrated path modeling, thereby mitigating sequential testing biases [40]. PLS-SEM proves particularly apt for operationalizing latent constructs with reflective–formative measurement models, a critical feature given this study’s reliance on perceptual variables requiring robust psychometric validation [41]. Its component-based algorithm explicitly accounts for measurement error through iterative weight optimization, addressing a fundamental limitation of covariance-based SEM approaches [40]. The technique’s nonparametric characteristics and predictive orientation further ensure analytical rigor under conditions of non-normal data distributions and moderate sample sizes, aligning with contemporary methodological standards for exploratory social science research.

3.1. Participants

This study targets third- and fourth-year undergraduates, graduate students, and recent alumni from Shandong University’s School of Economics and Management, selected based on their minimum three-year exposure to systematic entrepreneurship education. The target population comprised 4269 eligible candidates, with a statistically determined minimum sample of 356 participants calculated using Thompson’s (2012) power analysis formula. Through a convenience sampling methodology, we secured 475 valid responses—a sample size exceeding psychometric requirements for structural equation modeling applications [42]. Following Kline’s (2005) psychometric guidelines, this sample-to-parameter ratio (N = 475 vs. 32 measurement items) satisfies the recommended 10:1 threshold for ensuring model stability and statistical power [43]. Participant demographics and educational backgrounds are systematically detailed in Table 1, maintaining methodological transparency regarding sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Participants’ profiles.

3.2. Measurement

This study operationalizes entrepreneurial team efficacy (ETE) through eight core constructs (see Appendix A) and systematically measures performance outcomes and their antecedents. The measurement framework includes internal team communication (ITC), which assesses the frequency of information exchange among team members; external team communication (TEC), which evaluates the team’s ability to obtain resources from external stakeholders; learning willingness sharing (LWS), which captures the enthusiasm for knowledge dissemination; task understanding sharing (TUS), which measures the clarity of goal alignment; teammate cognitive sharing (TCS), which assesses mutual awareness of capabilities; activity status sharing (ASS), which tracks the transparency of task progress; team task efficacy (TTE), which evaluates the quality of goal achievement; and team relationship efficacy (TRE), which examines the dynamics of trust-building and conflict resolution. The scales are primarily derived from existing validated instruments in the fields of team communication and entrepreneurship education. To adapt to the context of Chinese higher education, the research team localized the scales through pilot testing and expert consultation, making them more suitable for the Chinese educational environment and easier for the research subjects to understand. The adjusted scales passed reliability (Cronbach’s α) and validity tests (including convergent and discriminant validity), ensuring their applicability and reliability in this study.

3.3. Data Collection and Procedures

The annual entrepreneurship competition for college students, organized by China’s Ministry of Education, is a key platform for fostering innovation and business acumen among youth. Our research team from Shandong University’s School of Economics and Management participated in this competition, leveraging the event to engage with teams from across the nation. During the competition, we highlighted the purpose and importance of our study to other participating teams. With their consent and support, we invited them to take part in a questionnaire survey designed by our team to gather data for our research. The survey, accessible via a QR code or a URL https://www.wjx.cn/vm/egdRYia.aspx# (accessed on 20 March 2025), was designed to be completed electronically. To boost participation and data quality, we offered cash rewards and encouraged participants to forward the survey to others, enhancing our sample size and representativeness. Prior to the main survey, a pilot test with 61 participants ensured the measurement tool’s clarity. Subsequent psychometric refinements addressed minor item overlaps. After obtaining ethical approval, we collected data from March to May 2024 through encrypted online forms, using snowball sampling via student networks (WeChat/QQ). We gathered 521 responses, of which 475 were valid (a 91.17% efficiency rate), meeting the threshold for structural equation modeling.

3.4. Data Analysis

The SmartPLS 3.0 software was employed for data analysis using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method. PLS-SEM was chosen over covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) for several reasons: (i) the study is exploratory in nature; (ii) the relationships among variables are complex, involving multiple latent constructs; (iii) PLS-SEM does not impose strict assumptions on the data distribution; and (iv) the method is suitable for testing mediating effects within the proposed theoretical framework [40].

PLS-SEM consists of two components: the inner model and the outer model. The inner model, similar to traditional regression analysis, is used to examine the causal relationships among latent variables. The relationships between variables can be interpreted as

In the above equation, β0j is a constant matrix; βqj represents the general path coefficient matrix between the exogenous variable (also known as the explanatory variable) εq and the endogenous variable εj; and ξj is the error term matrix.

The outer model focuses on the relationship between observed indicators and latent variables. The relationship coefficient between indicators and variables is called the factor loading, which can be expressed as

Here, wpi represents the factor loading matrix for each indicator on its respective latent variable εi, and the error term ζpi represents the unconsidered potential random part of the measured indicator.

Following the two-stage procedure proposed by Hair et al. [40], the analysis process was divided into two stages. The first stage focused on the measurement model (outer model), rigorously assessing the reliability and validity of the constructs [40]. This included evaluating key indicators such as Cronbach’s α, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and factor loadings to ensure the robustness of the measurement model. The second stage concentrated on the structural model (inner model), which examined the hypothesized relationships among latent variables, covering direct effects, mediating effects, and total effects. To address potential common method bias, complete collinearity statistics were calculated, and all variance inflation factors (VIF) in the inner model were below the threshold of 3.3 [44], confirming the absence of multicollinearity issues.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

The model assessment focuses on the measurement models to assess the convergent validity of the construct. It includes two types of indices: reliability and validity. For the reliability assessment, Cronbach’s Alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) are employed. Cronbach’s Alpha measures the consistency and reliability of observed variables for a latent variable, with values ranging from 0 to 1. Values between 0.7 and 0.8 indicate moderate reliability, while values between 0.8 and 0.9 suggest high reliability [45]. CR, a stricter measure that accounts for both the correlations and variances of observed variables, is considered acceptable when values reach 0.7 or higher [40]. Moreover, validity assessment is conducted using average variance extracted (AVE), factor loadings, and the Fornell–Larcker criterion. AVE measures the variance in observed variables explained by a latent variable, with ideal values exceeding 0.5, though values between 0.36 and 0.5 are also deemed acceptable [46]. Factor loadings, which reflect the contribution of observed variables to a latent variable, are considered valid when they exceed 0.5 [47]. The Fornell–Larcker criterion ensures discriminant validity by confirming that the square root of the AVE for each construct is greater than its correlations with other constructs.

Table 2 presents the reliability and validity assessment results of the scales used in this study, clearly indicating that all indices have met the recommended thresholds.

Table 2.

Convergent validity and reliability.

Moreover, the assessment of discriminant validity, conducted via the Fornell–Larcker criterion, revealed that the square roots of the AVE for each construct (diagonal values in Table 3) exceeded all corresponding off-diagonal correlations within their respective rows and columns. This finding robustly supports the discriminant validity of the measurement model, confirming that each latent construct is empirically distinct and captures unique variance unshared by other constructs in the framework [40].

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

To rigorously evaluate convergent and discriminant validity, cross-loadings were meticulously scrutinized. Following Radomir (2013), an indicator meets the cross-loading criterion if its factor loading on its purported latent variable markedly exceeds all cross-loadings on other variables [48]. As depicted in Table 3, all indicators satisfy this criterion, with the highest loading on their respective latent variables highlighted in bold italics. This substantiates the measurement model’s validity and reliability. Moreover, the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct, presented in Table 4, further corroborate discriminant validity by exceeding the shared variance with other constructs. Collectively, these analyses furnish a robust foundation for subsequent structural equation modeling, affirming that the measures accurately capture their intended constructs while minimizing overlap with others.

Table 4.

Loading and cross loadings.

4.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

In this section, the evaluation of the inner model structure centers on corroborating the relationships among latent variables as illustrated in Figure 2, along with the empirical assessment of the theoretical hypotheses posited in this study. This process specifically includes the examination of direct path hypotheses, mediating effect hypotheses, total effect hypotheses, and the impact of demographic characteristics on ETE.

4.2.1. Single-Path Hypothesis Test

The examination of direct path hypotheses aims to validate the direct impacts of ITC and TEC on various facets of SMMs, specifically LWS, TUS, TCS, and ASS. It further investigates how these shared mental models influence TTE and TRE. As shown in Table 5, the findings largely support the single-path hypotheses, uncovering the direct mechanisms through which team communication impacts team effectiveness.

Table 5.

Single-path hypothesis test results.

The findings in Table 5 shed light on the differential impacts of team internal communication (ITC) and external communication (TEC) on the dimensions of SMMs. Notably, ITC significantly boosts learning willingness sharing (LWS) (, p < 0.001), aligning with the principle that knowledge sharing kindles learning motivation. This structured ITC fosters an environment ripe for collaborative dynamics. ITC also strongly influences teammate cognitive sharing (TCS) (, p < 0.001), highlighting its role in building mutual awareness of team competencies, which is crucial for effective task allocation. Moreover, ITC significantly enhances activity state sharing (ASS) (, p < 0.001), underscoring how transparent communication reduces uncertainty and amplifies collaborative efficiency. However, the negative link between ITC and task understanding sharing (TUS) (0.109, p < 0.05) cautions against communication overload or misalignment, which can muddle task objectives. This suggests that entrepreneurial educators should craft communication protocols that balance dialogue with clarity.

Moreover, the distinct dimensions of SMMs exhibit divergent impacts on TTE and TRE. LWS significantly elevates TTE (, p < 0.001), underscoring its role as a catalyst for enhancing team innovation and execution. This finding corroborates the theoretical assumption that knowledge accumulation and innovation are central drivers of task effectiveness in entrepreneurial education. Similarly, TCS positively influences TTE (, p < 0.01), highlighting how awareness of teammates’ capabilities optimizes task allocation and execution efficiency. In contrast, TUS and ASS show no significant impact on TTE (p > 0.05), suggesting their primary role lies in facilitating collaboration processes rather than directly determining task outcomes. Regarding TRE, ASS demonstrates a strong positive effect (, p < 0.001), indicating that transparent awareness of task progress significantly strengthens emotional support and collaborative intent among team members. This aligns with the entrepreneurial education principle that transparent communication fosters trust and cohesion. Teammate TCS also positively influences TRE (, p < 0.05), as understanding teammates’ attributes enhances trust and relational bonds. Conversely, LWS and TUS show no significant impact on TRE (p > 0.05), likely because these dimensions are more closely tied to task execution than to relationship dynamics. These results emphasize the dual nature of SMMs in driving both task-oriented and relationship-oriented ETE.

4.2.2. Mediating Effect Hypothesis Test

This section explores the mediating roles of LWS, TUS, TCS, and ASS between TC and ETE. As shown in Table 6, the results support the proposed mediating hypotheses in our study, underscoring SMMs as bridging the gap between team communication and team effectiveness.

Table 6.

Mediating effect hypothesis test results.

Table 6 reveals the mediating effect of team communication (ITC and TEC) on ETE, confirming the bridging role of shared mental models. Specifically, LES significantly mediates the indirect effect of internal communication on task efficacy (TTE) (, t = 4.411, p < 0.001), indicating that stimulating members’ learning motivation can effectively enhance the team’s innovation ability and execution. Moreover, LWS also has a significant impact on TTE through external communication (, t = 2.622, p < 0.01), verifying the role of external resource introduction in promoting shared learning willingness. TCS also shows significance in the indirect effects of ITC and TEC on TTE (, t = 2.657, p < 0.01 and , t = 2.62, p < 0.05), further illustrating that optimizing the cognition of teammates’ abilities improves task allocation and execution efficiency. ASS significantly enhances TRE, with the indirect effect of ITC through ASS on TRE being , t = 4.967, p < 0.001, and the indirect effect of TEC through ASS being , t = 3.199, p < 0.001, indicating that transparent communication significantly improves team trust and willingness to collaborate. In contrast, TUS does not show a significant mediating effect in all paths (p > 0.05), which may be because TUS acts more on the team collaboration process rather than directly determining task or relationship efficacy.

This result provides a new theoretical perspective on team collaboration mechanisms in entrepreneurship education, breaking through the linear assumption of the traditional “communication frequency–efficacy paradox” and proposing a “dual-path model of internal collaboration and external interaction”. In practical terms, the results indicate that educators can enhance shared learning willingness and teammate cognitive sharing, thereby strengthening task efficacy, by establishing structured communication mechanisms such as regular meetings and interactions with external experts. Meanwhile, by enhancing activity status sharing to promote team trust and collaborative willingness, relationship efficacy can be improved. This dual-pronged strategy can effectively balance task execution and relationship maintenance, providing systematic support for team collaboration in entrepreneurship education.

4.2.3. Total Effect Hypothesis Test

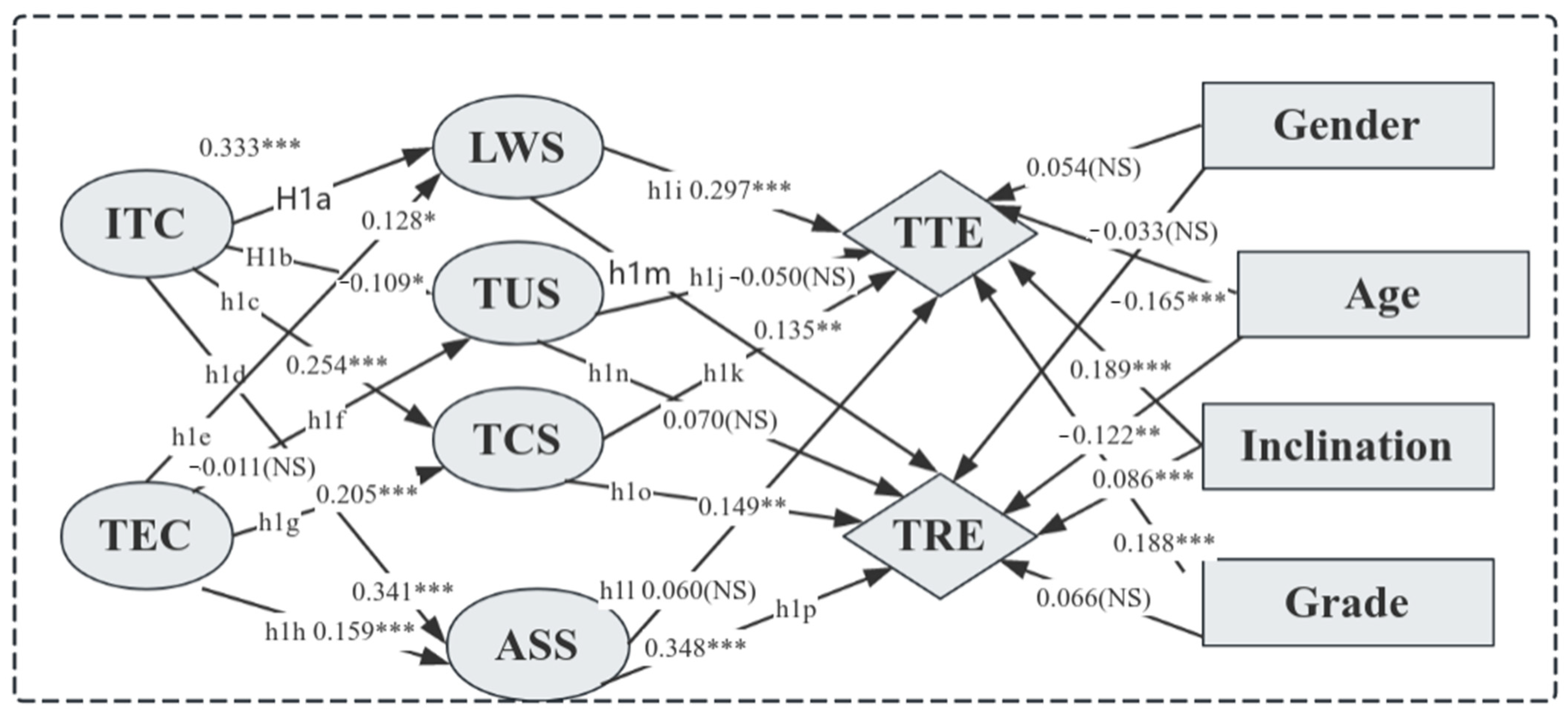

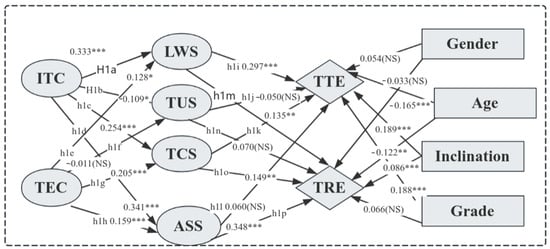

This section examines the overall impact of internal team communication (ITC) and external team communication (TEC) on team task efficacy (TTE) and team relationship efficacy (TRE). As shown in Table 7 and Figure 3, the results support the hypothesis of overall effects, confirming that team communication operates through multiple pathways and mechanisms to collectively influence team efficacy. These findings underscore the critical role of team communication in enhancing both task and relationship outcomes, thereby emphasizing its importance in driving team effectiveness.

Table 7.

Total effect hypothesis test results.

Figure 3.

The test results of the constructs’ relationship in this study. Notes: *** p < 0.001.** p < 0.01.* p < 0.05 “NS” means no significant effect.

The findings in Table 7 validate the central role of team communication in entrepreneurship education and introduce a “dual-path model of internal collaboration and external interaction”, offering a novel theoretical lens to understand how team communication collectively influences team efficacy through multiple pathways. Specifically, ITC significantly enhances TTE by fostering LWS and TCS (, p < 0.001). This indicates that ITC, by clarifying task objectives and optimizing resource allocation, strengthens the team’s innovation and execution capabilities. These results suggest that educators should employ structured communication mechanisms, such as regular meetings and task breakdowns, to strengthen internal collaboration. Concurrently, TEC significantly boosts TRE by introducing external resources and perspectives (, p < 0.001). TEC, by facilitating interactions with external experts, not only brings in new knowledge and skills but also enhances trust and collaborative motivation among team members. These results imply that educators should incorporate external resources, such as industry mentors and cross-team interactions, to optimize relationship efficacy.

Further analysis reveals that ITC primarily elevates task effectiveness through cognitive synergy mechanisms like LWS and TCS, while TEC enhances relationship effectiveness through relational network reinforcement mechanisms like ASS. This dual-path model provides a systematic framework for team collaboration mechanisms in entrepreneurship education, suggesting that educators should select communication strategies according to efficacy objectives. In practical terms, these results indicate that educators can balance task execution and relationship maintenance by implementing structured communication mechanisms and introducing external resources, thereby maximizing team effectiveness. This approach not only offers valuable insights for optimizing team collaboration mechanisms in entrepreneurship education but also provides a theoretical basis for designing efficient team collaboration strategies.

4.2.4. The Impact of Demographic Characteristics on TTE and TRE

Table 8 reveals a negative correlation between student age and TTE, indicating potential challenges for older students in enhancing TTE. Paradoxically, student grade level positively impacts TTE, conflicting with age’s influence. This discrepancy likely arises from distinct psychological and behavioral traits associated with age and grade. Older students, constrained by entrenched cognitive patterns, may exhibit reduced flexibility in adapting to novel tasks or innovative approaches, thereby hindering TTE. In contrast, senior students, equipped with richer teamwork experience and domain-specific knowledge, excel in coordinating team dynamics and resource utilization, leading to improved task performance and output quality. Their deeper understanding of team goals and organizational culture also heightens commitment and engagement, further elevating TTE. Thus, though age and grade are correlated, their impacts on TTE stem from distinct mechanisms. Age also negatively correlates with TRE, as older students, rigid in their ideas and communication styles, may impede team coordination and cohesion. Conversely, academic inclination positively correlates with TRE, with natural science students demonstrating stronger relationship-building capabilities. This likely reflects the systematic and logical training inherent in natural science education, which enhances problem-solving and adaptability, fostering cooperation and mutual understanding.

Table 8.

The impact of demographic characteristics on TTE and TRE.

This section synthesizes the empirical findings on team communication architectures and shared mental models within entrepreneurial education. Key results confirm the dual-path model of internal collaboration and external interaction, revealing that intra-team communication (ITC) enhances task effectiveness (TTE) primarily through shared learning willingness (LWS) and teammate cognitive sharing (TCS), while external communication (TEC) boosts relationship effectiveness (TRE) predominantly via activity status sharing (ASS). Notably, demographic factors like age and academic year exert divergent influences: age negatively correlates with both TTE and TRE, potentially due to rigid cognitive patterns, whereas seniority positively impacts TTE through accumulated experience and deeper cultural understanding. Academic inclination also positively correlates with TRE, highlighting natural science students’ superior relationship-building capabilities attributed to systematic training. These insights underscore the need for tailored educational strategies, such as innovative task design for older students and interdisciplinary collaborations to leverage diverse academic strengths. The results, visualized in Figure 3, collectively emphasize the importance of balancing task execution and relationship maintenance to optimize team effectiveness in entrepreneurship education.

5. Conclusions, Discussion, and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of entrepreneurial team efficacy (ETE) by empirically validating a dual-path model that integrates team communication (TC) and shared mental models (SMMs) within China’s higher education context. Key findings reveal that internal team communication (ITC) significantly enhances task effectiveness (TTE) through shared learning willingness (LWS, = 0.333, p < 0.001) and teammate cognitive sharing (TCS, = 0.254, p < 0.001). However, the negative association of ITC with task understanding sharing (TUS, = −0.109, p < 0.05) underscores the risk of communication overload in misaligning task objectives. External team communication (TEC) primarily bolsters relationship effectiveness (TRE) via activity status sharing (ASS, = 0.348, p < 0.001), demonstrating its role in fostering trust and cohesion through external resource integration. Demographic factors exert divergent impacts: age negatively correlates with both TTE ( = −0.165, p < 0.001) and TRE ( = −0.122, p < 0.01), likely due to cognitive rigidity, while academic seniority enhances TTE ( = 0.188, p < 0.001) through accumulated collaborative experience.

Theoretically, this research bridges critical gaps in entrepreneurial pedagogy by establishing SMMs as mediators between TC and ETE, challenging the linear assumptions of the “communication frequency–efficacy paradox”. It proposes a dual-path framework where ITC and TEC differentially optimize task execution (cognitive calibration) and relational cohesion (network reinforcement), respectively. Additionally, it contextualizes Western theories (e.g., Minniti’s opportunity recognition) to address cultural specificities in collectivist settings, such as “face” dynamics and decision transparency in Chinese teams. These findings underscore the importance of structured communication strategies in entrepreneurship education, highlighting the need to balance task execution and relationship maintenance to foster collaboration in entrepreneurial teams. The results collectively emphasize the value of tailored educational interventions that address the unique psychological and behavioral mechanisms influencing ETE.

5.2. Discussion

This study reveals that structured internal communication significantly enhances the alignment of learning goals, teammate cognition, and activity synchronization, thereby fostering the formation of shared mental models. This echoes prior studies that emphasize the importance of internal communication in boosting team collaboration and cognition. For instance, Tkalac et al. (2021) [32] also indicate that effective internal communication can promote information sharing and cognitive consistency among team members, thereby improving team collaboration efficiency.

Nevertheless, this research goes further by presenting a dual-path model that distinguishes the impact pathways of internal and external communication on task and relational outcomes. This finding contrasts with the traditional “communication frequency–efficacy paradox”. Our results indicate that internal communication primarily enhances task execution through cognitive calibration, while external communication strengthens team cohesion through relational network reinforcement. This offers fresh insight into the complex dynamics of team communication.

5.3. Policy Implications

To address the youth unemployment crisis and enhance entrepreneurial education outcomes, policymakers and educators should prioritize structured communication protocols and implement targeted strategies.

- (1)

- Enhancing Communication Training and Channels

Internal Communication Training: Universities should integrate internal team communication (ITC) training into entrepreneurial education curricula, focusing on regular team debriefings and role-based feedback loops to strengthen shared learning willingness (LWS) and teammate cognitive sharing (TCS), ensuring alignment between communication intensity and task clarity.

External Communication Channels: Education authorities should collaborate with industry associations to establish mentorship platforms connecting universities and enterprises. These platforms should provide access to experienced entrepreneurial mentors and facilitate cross-university innovation hubs to enhance activity status sharing (ASS) and external resource utilization.

- (2)

- Tailored Interventions for Different Demographic Groups

Strategies for Senior Students: Universities should customize entrepreneurial education courses for senior students, incorporating advanced modules on complex project management and team leadership. Additionally, specialized incubation funds should be established to support senior student entrepreneurial projects, leveraging their accumulated collaborative experience to optimize knowledge transfer and task coordination.

Strategies for Junior Students: For junior students, universities should design courses that focus on innovative thinking and basic team collaboration skills, incorporating immersive learning modules such as simulated entrepreneurial games. Mentorship programs should also be established to provide personalized guidance and support for junior students.

- (3)

- Promoting Interdisciplinary Team Collaboration

Interdisciplinary Team Formation and Incentives: Universities should encourage the formation of interdisciplinary entrepreneurial teams and provide incentives such as cash rewards and priority access to resources for outstanding teams. Interdisciplinary practice bases should also be established to support these teams.

Interdisciplinary Curriculum and Faculty Development: universities should develop interdisciplinary entrepreneurial courses and strengthen faculty training in this area to provide robust support for interdisciplinary team collaboration.

- (4)

- Improving Policy Support and Evaluation Mechanisms

Policy Integration and Resource Allocation: The development of shared mental models (SMMs) should be incorporated into the “Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation” policy framework, with a clear mandate for universities to allocate a portion of entrepreneurial coursework to team cognition synchronization exercises. Education authorities should provide funding support for universities actively implementing these training programs.

Effectiveness Evaluation and Dynamic Adjustment: A comprehensive evaluation mechanism should be established to assess the implementation of entrepreneurial education in universities, focusing on key indicators such as team communication and team efficacy. Based on the assessment results, policies should be dynamically adjusted to ensure their effectiveness in driving entrepreneurial education development and addressing youth unemployment.

5.4. Limitation and Future Work

This study offers novel insights into TC and SMMs in entrepreneurial education, yet several limitations warrant attention. Sample constraints arise from data collection limited to a single university (Shandong University), which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Future research should expand to diverse regions, including coastal and inland provinces, to capture socioeconomic heterogeneity. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of the study, relying on PLS-SEM analyses, precludes causal inferences. Longitudinal or experimental designs, such as pre–post intervention studies, could better capture the dynamic maturation processes of entrepreneurial teams. Furthermore, the findings are rooted in China’s collectivist context, suggesting that comparative studies in individualistic cultures (e.g., the U.S. or Germany) could test the universality of the dual-path model. Finally, while reflective–formative constructs were validated, future research should incorporate objective metrics, such as venture success rates and investor evaluations, to triangulate perceptual data and enhance measurement robustness.

Future research directions could further advance this field. Studies could explore the efficacy of digital tools, such as AI-driven collaboration platforms, in addressing generational challenges like overreliance on screen time. Additionally, gender dynamics warrant deeper investigation, as nonsignificant findings (β = 0.054, p > 0.05 for TTE) suggest unexplored cultural nuances in mixed-gender teams. Finally, neurocognitive experiments, such as fMRI scans during team tasks, could map the neural correlates of SMM formation, offering a biological foundation for understanding team cognition processes. These directions promise to enrich theoretical frameworks and provide actionable insights for enhancing entrepreneurial education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F. and S.W.; methodology, S.W.; software, S.F.; validation, W.M. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, S.F.; investigation, S.F.; resources, W.M.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, S.W.; project administration, S.W.; funding acquisition, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the University-level Research Project of Wenzhou University of Technology (Number: ky202404) and is supported by the Doctoral Research Initiation Fund Project: A Study on the Strategies of Enhancing College Students’ Participation in Environmental Protection through Ecological Civilization Education in Universities in the Bijie Area (Project Number: BSLB-202424).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Items Included in Questionnaire

| Latent Variables | Definition | Items | Measurement Items | Source |

| ITC | Refers to the interactive process where team members, in the context of entrepreneurial and innovative activities, frequently share relevant information and ideas through open and effective communication methods. They actively express diverse opinions and feedback, ensuring every member has the opportunity to participate in decision-making and have their views seriously considered. This communication mechanism also facilitates the swift and efficient resolution of issues and advancement of projects. | ITC1 | Our team members frequently share information and ideas related to entrepreneurship and innovation. | [49] |

| ITC2 | Within the team, members are willing to openly express their differing opinions and feedback on entrepreneurial projects. | |||

| ITC3 | Team members have the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes for innovation and entrepreneurship, and their opinions are taken into account. | |||

| ITC4 | Our team’s communication style helps to quickly and effectively solve problems and advance project progress. | |||

| TEC | Refers to the team’s communication capabilities and practices in entrepreneurial and innovative activities. This includes actively acquiring information and knowledge from other teams, engaging in effective interactions, promptly integrating external feedback for project improvement and innovation, and effectively coordinating and utilizing various resources in external team communication to support entrepreneurial activities. | TEC1 | Our team actively seeks information and knowledge about entrepreneurship and innovation from other teams. | [32] |

| TEC2 | Team members often interact effectively with other entrepreneurial and innovative teams. | |||

| TEC3 | Our team can promptly integrate feedback from other entrepreneurial and innovative teams and apply it to the improvement and innovation of our projects. | |||

| TEC4 | When communicating with external teams, the team can effectively coordinate and utilize various resources to support entrepreneurial activities. | |||

| LWS | Refers to the initiative of team members to share learning resources they have acquired, such as books, articles, online courses, etc., and actively share personal knowledge and experience to promote the growth of other members in the team during entrepreneurial and innovative activities. | LWS1 | Team members are willing to share entrepreneurial and innovation-related learning resources they have obtained, such as books, articles, online courses, etc. | [50,51] |

| LWS2 | Team members actively share their knowledge and experience to help other team members learn and grow. | |||

| LWS3 | The team encourages mutual learning among members, providing the necessary time and space to promote knowledge sharing. | |||

| LWS4 | The team encourages members to try new methods and ideas, even if these attempts may not succeed immediately. | |||

| TUS | Refers to the process in entrepreneurial and innovative projects where team members form a clear consensus on the project’s objectives and expected outcomes. Each member understands their role and specific responsibilities within the project. They have a thorough and consistent understanding of the tasks assigned to them and ensure all members maintain an updated understanding of the project’s status by promptly sharing progress and feedback. | TUS1 | Team members have a clear consensus on the objectives and expected outcomes of entrepreneurial and innovative projects. | [52] |

| TUS2 | Team members are clear about their roles and specific responsibilities within the project. | |||

| TUS3 | Team members have a thorough and consistent understanding of the tasks assigned to them. | |||

| TUS4 | Team members promptly share project progress and feedback to ensure all members have an updated understanding of the project status. | |||

| TCS | Refers to the understanding within the team of each member’s professional capabilities and skills, considering these in task allocation to ensure the right fit. Members actively share their work styles and preferences to promote team collaboration and coordination. | TCS1 | Team members have a clear understanding of each other’s professional capabilities and skills, which is considered in task allocation. | [53] |

| TCS2 | Team members regularly share their work styles and preferences to better collaborate and coordinate work. | |||

| TCS3 | The team encourages members to share ideas and creativity, taking everyone’s contributions seriously. | |||

| TCS4 | The team effectively utilizes each member’s individual strengths in projects and tasks. | |||

| ASS | Refers to the practice where team members actively update the progress of tasks they are responsible for, ensuring transparency and timeliness of internal team information. When facing challenges, members proactively share issues and seek collective solutions. They also share information and opportunities regarding resources or support with other team members to foster resource sharing and collaboration. | ASS1 | Team members frequently update the progress of tasks they are responsible for to ensure transparency of internal team information. | [54] |

| ASS2 | When team members encounter challenges, they proactively share and seek collective solutions from the team. | |||

| ASS3 | Team members share information and opportunities regarding resources or support with other team members. | |||

| ASS4 | Team members have a clear understanding of each other’s work status and the overall collaborative dynamics of the team. | |||

| TTE | Refers to the team’s ability to not only continuously complete tasks and ensure the quality of results meets or exceeds set standards but also to effectively manage and utilize time and resources for efficient task completion. Additionally, the team regularly produces innovative ideas and solutions, demonstrating strong innovation capabilities. | TTE1 | Our team consistently meets or exceeds predetermined standards in the quality of tasks completed for entrepreneurial and innovative projects. | [55] |

| TTE2 | The team effectively manages time and resources to efficiently complete assigned tasks. | |||

| TTE3 | The team regularly produces innovative ideas and solutions in the process of entrepreneurship and innovation. | |||

| TTE4 | Team members have a common understanding of project goals and work consistently towards these objectives. | |||

| TRE | Refers to the establishment of mutual trust, open communication, conflict resolution capabilities, and support for innovation and attempts among team members. These factors collectively affect the team’s cohesion and effectiveness. | TRE1 | There is a high level of trust among team members, which helps us remain united in the face of challenges. | [56] |

| TRE2 | Team members engage in open and honest communication, even when discussing sensitive or difficult topics. | |||

| TRE3 | Our team can effectively resolve conflicts among members and learn and grow from them. | |||

| TRE4 | The team creates an atmosphere that supports and encourages innovation and attempts, even in the face of failure. |

References

- Fakih, A.; Haimoun, N.; Kassem, M. Youth Unemployment, Gender and Institutions During Transition: Evidence from the Arab Spring. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileshi, M.; Jemal, K.; Feyisa, B.W. Determinants of school dropouts and the impact on youth unemployment: Evidence from Ethiopia. Econ. Syst. 2024, 48, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Xiong, W. Is entrepreneurship a remedy for Chinese university graduates’ unemployment under the massification of higher education? A case study of young entrepreneurs in Shenzhen. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 84, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liang, J.; Wu, B. Labor Market Experience and Returns to College Education in Fast-Growing Economies. J. Hum. Resour. 2025, 60, 289–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, N.D.A.R. China National Bureau of Statistics responds to the Rising Youth Unemployment Rate: Targeted Assistance Will Be Provided. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/jyysr/jysrsbxf/202305/t20230530_1356762.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Chen, N.; Shabbir, M.S. Social entrepreneurship education landscape mapping: A bibliometric analysis and analysis of empirical research. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2025, 23, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi-Puertas, M.A.; Agirre-Aramburu, I.; López-Pérez, S. Navigating the student entrepreneurial journey: Dynamics and interplay of resourceful and innovative behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174, 114524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Y.; Mao, T.; Deng, S.; Li, Y. Entrepreneurship education stimulates entrepreneurial intention of college students in China: A dual-pathway model. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2025, 23, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, N.L.; Thomas, K.; Dyer, B.; Rea, J.; Bardi, A. The values of only-children: Power and benevolence in the spotlight. J. Res. Pers. 2021, 92, 104096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, R.; Hua, H.; Yang, Q.; Yang, D.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Ma, F.; Huang, L.; et al. Association between the pattern of mobile phone use and sleep quality in Northeast China college students. Sleep. Breath. 2021, 25, 2259–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Mok, K.H. The COVID-19 pandemic and post-graduation outcomes: Evidence from Chinese elite universities. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 124, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, D.; Freund, R.; Novella, R. Entrepreneurial skills training for online freelancing: Experimental evidence from Haiti. Econ. Lett. 2023, 232, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnali, M.; Orakci, Ş.; Khalili, T. Fostering creative thinking skills to burst the effect of emotional intelligence on entrepreneurial skills. Think. Ski. Creat. 2023, 47, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, N.; Ali, S.; Shaheen, I. Navigating the entrepreneurial landscape: The interplay of government support and self-efficacy in entrepreneurial education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liang, L. How does response to work communication impact employees’ collaborative performance? A view of the social connectivity paradox. Inform. Manag. Amster 2024, 61, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, C.S. Entrepreneurs’ Positive Social Identity Development Through Initiated Intra-and Intergroup (Non) Accommodative Communication. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2023, 50114774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.C.; Kuckertz, E.A. Complexity in Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Technology Research: Empirical and Theoretical Approaches. Applications of Emergent and Neglected Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F.; Moriano, J.A. Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, W. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2022/2023 Global Report: Adapting to a “New Normal”. Available online: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/84402/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Bai, C.; Jia, R.; Li, H.; Wang, X. Entrepreneurial Reluctance: Talent and Firm Creation in China. Econ. J. 2025, 135, 964–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlayer, C.; Timm, J.; Halberstadt, J. Navigating the dimensions of criticality: Exploring reflective processes in critical entrepreneurship education. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. R. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. Entrepreneurial intention among engineering students: The role of entrepreneurship education. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 24, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Webb, J.W.; Franklin, R.J. Understanding the Manifestation of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Nonprofit Context. Am. J. Small Bus. 2011, 35, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdellah, Y.; Diani, A. The Entrepreneurial University Wheel: A University Ecosystem Framework for Developing Countries. J. Dev. Entrep. 2025, 30, 2550005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, H.; Saa’Din, I.; Ithnin, H.S.; Rakiman, U.S. Entrepreneurial Intention among Non-Business Students: The Role of Entrepreneurship Education, Interest and University Support. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Social. Sci. 2022, 12, 2825–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathisen, J.; Arnulf, J.K. Competing mindsets in entrepreneurship: The cost of doubt. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2013, 11, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon-Bowers, J.; Salas, E.; Converse, S. Cognitive psychology and team training: Training shared mental models and complex systems. Hum. Factors Soc. Bull. 1991, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Iyasere, C.A.; Wing, J.; Martel, J.N.; Healy, M.G.; Park, Y.S.; Finn, K.M. Effect of Increased Interprofessional Familiarity on Team Performance, Communication, and Psychological Safety on Inpatient Medical Teams: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiferes, J.; Bisantz, A.M. The impact of team characteristics and context on team communication: An integrative literature review. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 68, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, D.G.; Caldwell, D.F. Bridging the Boundary: External Activity and Performance in Organizational Teams. Admin Sci. Quart. 1992, 37, 634–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkalac Verčič, A.; Sinčić Ćorić, D.; Pološki Vokić, N. Measuring internal communication satisfaction: Validating the internal communication satisfaction questionnaire. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2021, 26, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, L.L.; Wilson, J.M.; Wholey, D.R. Cognitive divergence and shared mental models in software development project teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimoski, R.; Mohammed, S. Team mental model: Construct or metaphor? J. Manag. 1994, 20, 403–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.J.; Jiang, R.; Tsai, J.C.; Klein, G. Shared mental models in multi-team systems: Improving enterprise system implementation. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2023, 16, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, R. Empowered self-management and the design of work teams. Pers. Rev. 2004, 33, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.S.; Carter, M.Z.; Zhang, Z. Leader-Team Congruence in Power Distance Values and Team Effectiveness: The Mediating Role of Procedural Justice Climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljac-Samardzic, M.; Doekhie, K.D.; van Wijngaarden, J.D.H. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: A systematic review of the past decade. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, L.L.; de Jong, B.A.; Schouten, M.E.; Dannals, J.E. Why and When Hierarchy Impacts Team Effectiveness: A Meta-Analytic Integration. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Hamburg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qadasi, N.; Zhang, G.; Al-Jubari, I.; Al-Awlaqi, M.A.; Aamer, A.M. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial behaviour: Do self-efficacy and attitude matter? Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.K. Sampling; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, A.A. Cronbach’s Alpha: Review of Limitations and Associated Recommendations. J. Psychol. Afr. 2010, 20, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monecke, A.; Leisch, F. semPLS: Structural Equation Modeling Using Partial Least Squares. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomir, L. State of the Art in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): Methodological Extensions and Applications in the Social Sciences and Beyond; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.Y. Model of Virtual Leadership, Intra-team Communication and Job Performance Among School Leaders in Malaysia. Procedia Social. Behav. Sci. 2015, 186, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencsik, A.; Molnar, P.; Juhasz, T.; Machova, R. Relationship Between Knowledge Sharing Willingness and Life Goals of Generation Z. In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM 2018), Padua, Italy, 6–7 September 2018; Academic Conferences International Limited: Parish, UK, 2018; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Deng, D. Effect of Interns’ Learning Willingness on Mentors’ Knowledge-sharing Behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llahana, S.; Yuen, K.C.J. Development and validation of a novel treatment adherence, satisfaction and knowledge questionnaire (TASK-Q) for adult patients with hypothalamic-pituitary disorders. Pituitary 2024, 27, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chong, L.; Kotovsky, K.; Cagan, J. Trust in an AI versus a Human teammate: The effects of teammate identity and performance on Human-AI cooperation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, L.; Halbeisen, G.; Braks, K.; Huber, T.J.; Paslakis, G. The State Urge to be Physically Active-Questionnaire (SUPA-Q): Development and validation of a state measure of activity urges in patients with eating disorders. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarare, A.; Hansson, J.; Fossum, B.; Fürst, C.J.; Lundh Hagelin, C. Team type, team maturity and team effectiveness in specialist palliative home care: An exploratory questionnaire study. J. Interprof Care 2019, 33, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somech, A.; Desivilya, H.S.; Lidogoster, H. Team conflict management and team effectiveness: The effects of task interdependence and team identification. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).