Dimensions of Institutional Technologies and Its Role in Convergence of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and International Marketing: Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How do institutional technology dimensions enable or challenge the convergence of international marketing and sustainable supply chain management?

- RQ2: How does the convergence of international marketing and sustainable supply chain management impact institutional technology dimensions?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions

2.2. Litertrure Gap

2.2.1. The Network Theory

2.2.2. Transaction Cost Theory

2.2.3. Network Theory and Transaction Cost Theory—The Comparative Analysis

2.2.4. Concluding the Literature Review

2.3. Research Gap

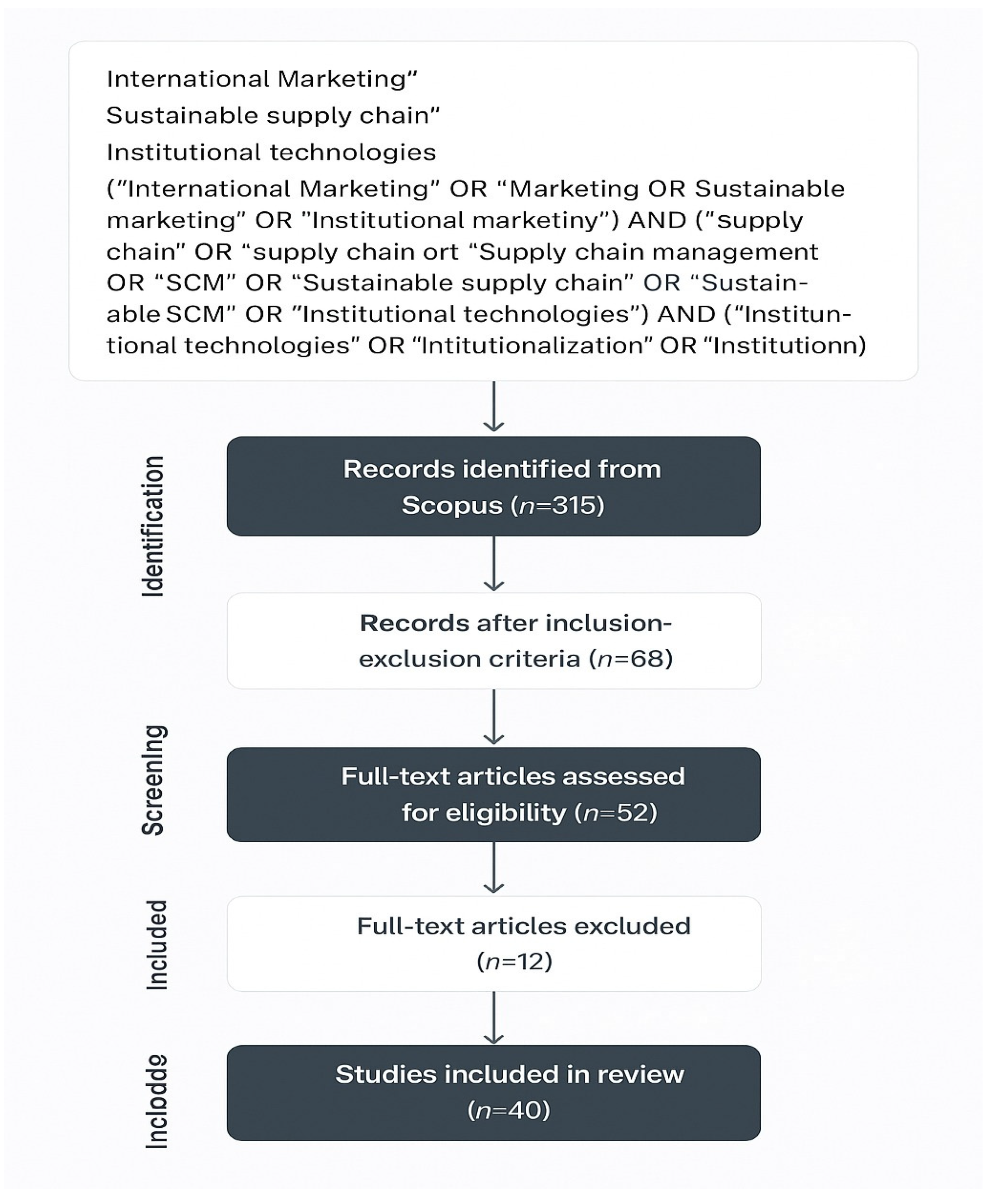

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Critical Realism

3.2. Thematic Approach

3.3. Data Collection

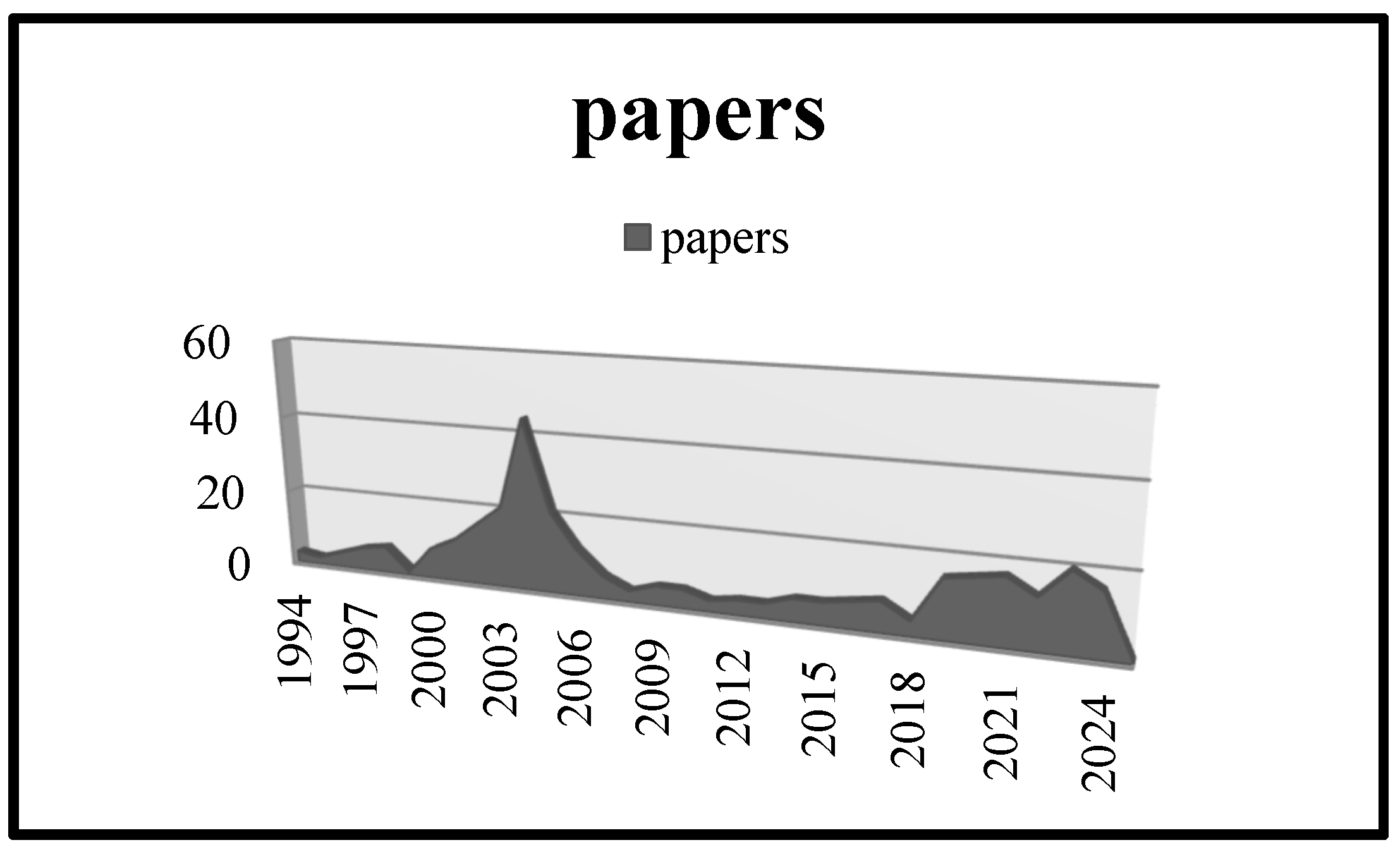

3.4. Descriptive Analysis

4. Results and Findings of SLR

4.1. Systematic Review

4.1.1. International Marketing

4.1.2. Sustainable Supply Chain Management

4.1.3. Convergence and Application of IT

4.1.4. Convergence and Business Model Innovation

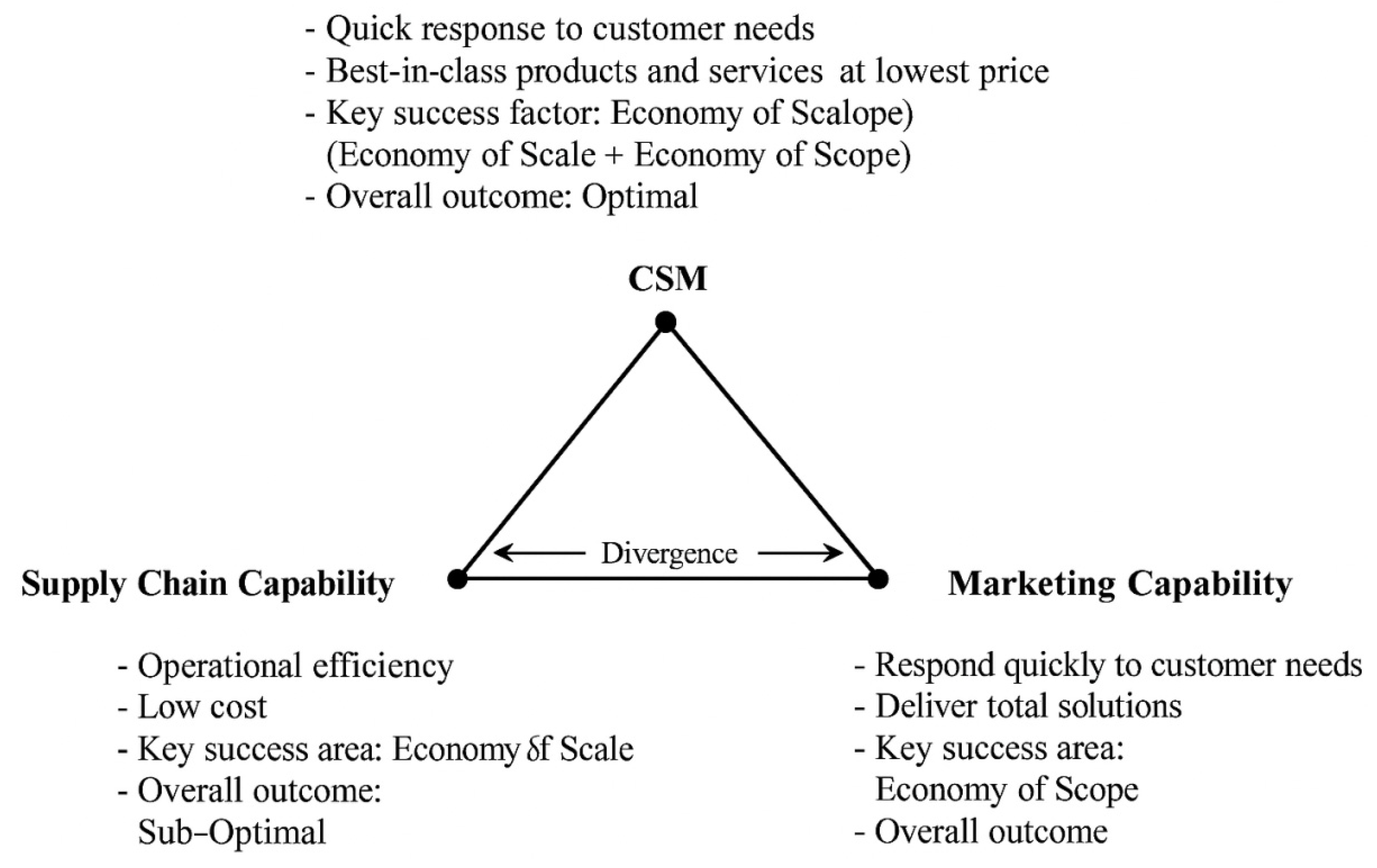

4.1.5. Convergence and Shift in Focus

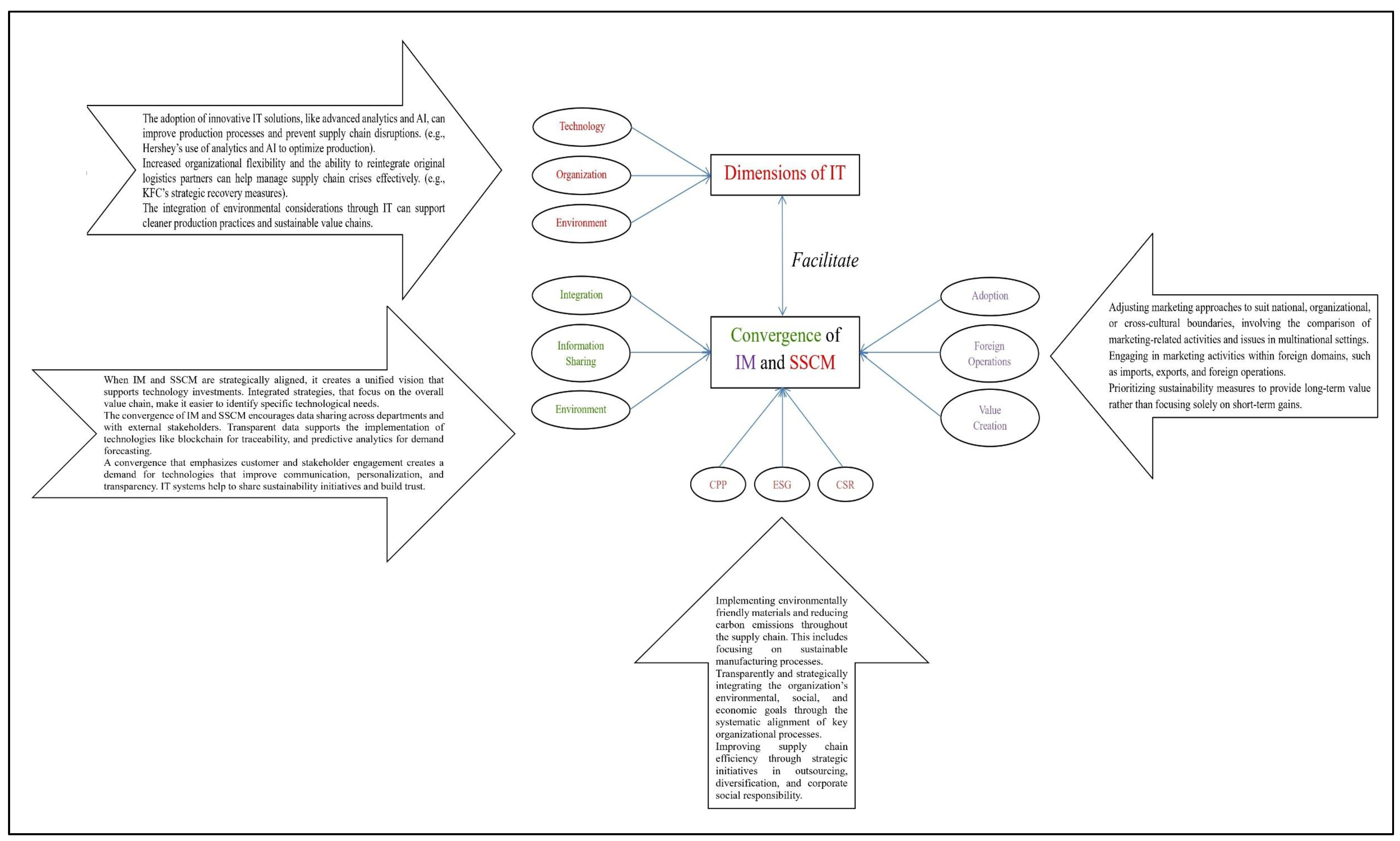

4.2. Finding of Systematic Review

represents the 1st order themes,

represents the 1st order themes,  represents the 2nd order themes, and

represents the 2nd order themes, and  represents the aggregate dimensions. Red indicates dimensions of IT, green indicates convergence dimensions, purple represents IM dimensions, and brown indicates SSCM dimensions.

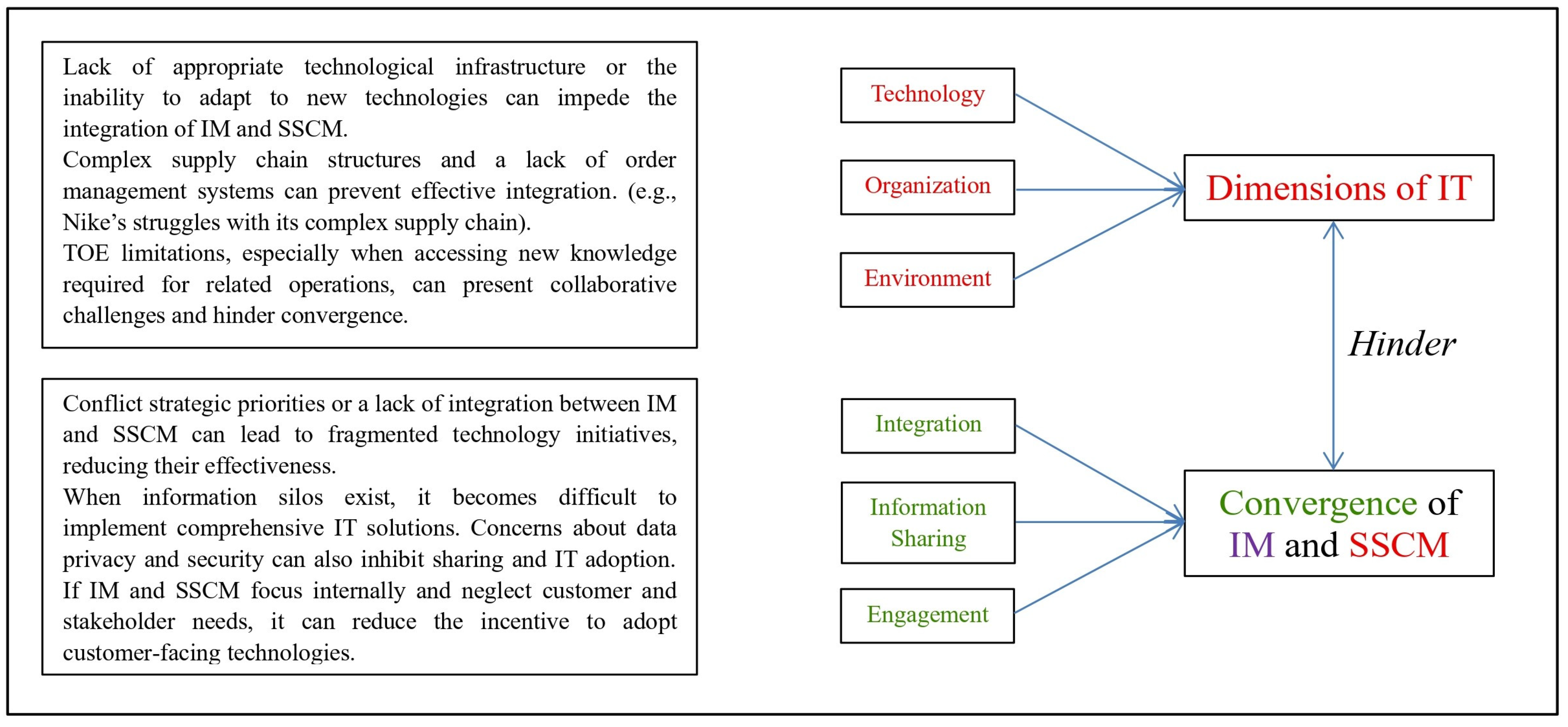

represents the aggregate dimensions. Red indicates dimensions of IT, green indicates convergence dimensions, purple represents IM dimensions, and brown indicates SSCM dimensions.4.2.1. Dimensions of Institutional Technologies

4.2.2. Dimension of Convergence

5. Conclusions

5.1. Future Research Agenda

5.2. Theoretical and Managerial Contribution

5.3. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.; Filieri, R. Institutional forces, leapfrogging effects, and innovation status: Evidence from the adoption of a continuously evolving technology in small organizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janin Rivolin, U. Planning Systems as Institutional Technologies: A Proposed Conceptualization and the Implications for Comparison. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Chhikara, R.; Agrawal, G.; Rathi, R.; Arya, Y. Sustainable marketing mix and supply chain integration: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koberg, E.; Longoni, A. A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management in global supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.M.O.; Hendry, L.C.; Silva, M.E.; Bossle, M.B.; Antonialli, L.M. Sustainable supply chain management in a global context: The perspective of emerging economy suppliers. RAUSP Manag. J. 2023, 58, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saththasivam, G.; Fernando, Y. Integrated Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Current Practices and Future Direction. In Supply Chain and Logistics Management: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 2061–2072. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/integrated-sustainable-supply-chain-management/239369 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Chen, L.; Jia, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z. The relationship between supply chain integration and sustainability performance: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 1388–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Ubillos, J.; Camino-Beldarrain, V.; Intxaurburu-Clemente, G.; Velasco-Balmaseda, E. Industry 4.0 and potential for reshoring: A typology of technology profiles of manufacturing firms. Comput. Ind. 2023, 148, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, S. Top 10: Worst Supply Chain Disasters in History. 2021. Available online: https://supplychaindigital.com/supply-chain-risk-management/top-10-worst-supply-chain-disasters-history (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Villena, V.H.; Gioia, D.A. A More Sustainable Supply Chain. 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/03/a-more-sustainable-supply-chain (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Bag, S.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, S.; Sivarajah, U. Role of technological dimensions of green supply chain management practices on firm performance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. A review on sustainable supply chain network design: Dimensions, paradigms, concepts, framework and future directions. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Cheng, T.C.E. Institutional isomorphism and the adoption of information technology for supply chain management. Comput. Ind. 2006, 57, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimissa, O.; Kangarani-Farahani, A.; Molla-Alizadeh-Zavardehi, S. Evaluation of sustainable supply chain management performance: Dimensions and aspects. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, S.; Piprani, A.Z.; Ellahi, R.M.; Nguyen, D.N.; Le, T.M.; Nazir, S. Industry 4.0 technologies and circular economy synergies: Enhancing corporate sustainability through sustainable supply chain integration and flexibility. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebea. The Great KFC Chicken Shortage 2018—The Economics, Business and Enterprise Association (EBEA). 2018. Available online: https://ebea.org.uk/archive/the-great-kfc-chicken-shortage-2018 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- ADEC Innovations. How Does Nike’s Supply Chain Work? ADEC Innovations. 2020. Available online: https://www.adec-innovations.com/blogs/how-does-nikes-supply-chain-work/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Garland, M. Inside Hershey’s $1B Push to Boost Its Supply Chain Capacity. Supply Chain Dive. 2023. Available online: https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/inside-hersheys-1b-push-to-boost-its-supply-chain-capacity/691799/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Awa, H.O.; Ukoha, O.; Emecheta, B.C. Using T-O-E theoretical framework to study the adoption of ERP solution. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1196571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Moon, H.C. Investigating the Impact of Industry 4.0 Technology through a TOE-Based Innovation Model. Systems 2023, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelariu, C.; Bello, D.C.; Gilliland, D.I. Institutional antecedents and performance consequences of influence strategies in export channels to Eastern European transitional economies. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceipek, R.; Hautz, J.; Mayer, M.C.; Matzler, K. Technological Diversification: A Systematic Review of Antecedents, Outcomes and Moderating Effects. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 466–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, M. Home and away: The use of institutional and non-institutional technologies to support learning and teaching. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2015, 24, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Khajuria, A.; Arora, S.; King, D.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. The impact of mobile technology on teamwork and communication in hospitals: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlbjørn, J.S.; de Haas, H.; Munksgaard, K.B. Exploring supply chain innovation. Logist. Res. 2011, 3, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerman, O.; Dědková, J. Marketing Innovations in Industry 4.0 and Their Impacts on Current Enterprises. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visnjic, I.; Wiengarten, F.; Neely, A. Only the Brave: Product Innovation, Service Business Model Innovation, and Their Impact on Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, B.; Di Maria, E.; Cygler, J. Do clusters matter for foreign subsidiaries in the Era of industry 4.0? The case of the aviation valley in Poland. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, T. Price convergence and fundamentals in asset markets with bankruptcy risk: An experiment. Int. J. Behav. Account. Finance 2015, 5, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Maghsoudi, M.; Shokouhyar, S. The convergence of IoT and sustainability in global supply chains: Patterns, trends, and future directions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 197, 110631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. A Market Convergence Prediction Framework Based on a Supply Chain Knowledge Graph. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Companies. Available online: https://www.bollettinoadapt.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/How-Smart-Connected-Products-Are-Transforming-Companies.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Mugoni, E.; Kanyepe, J.; Tukuta, M. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices (SSCMPS) and environmental performance: A systematic review. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Hatton, M.R.; Wu, C.; Chen, X. Sustainable supply chain management: Continuing evolution and future directions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 50, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Washispack, S. Mapping the Path Forward for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Review of Reviews. J. Bus. Logist. 2018, 39, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarian, E.; Ijadi, B.; Zare, A.; Majava, J. Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Industrial Practices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, S.; Sakka, G.; Apoorva. Cross-disciplinary issues in international marketing: A systematic literature review on international marketing and ethical issues. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 38, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Hulland, J.; Shaw, J.D.; Gaur, A.; Czinkota, M.R.; Christofi, M. Guest editorial: Systematic literature reviews in international marketing: From the past to the future and beyond. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, S. Objectives, Challenges, and the Way Forward. J. Int. Mark. 2014, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A. From the Editor in Chief. J. Int. Mark. 2008, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Aloysius, J.A. Supply chain transparency and willingness-to-pay for refurbished products. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 797–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjanor-Doku, C.; Ellis, F.Y.; Affum-Osei, E. Environmental performance: A systematic review of literature and directions for future studies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 32, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. On the importance of sustainable human resource management for the adoption of sustainable development goals. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiborn, C.A.; Butler, J.B.; Massoud, M.F. Environmental reporting: Toward enhanced information quality. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Khan, N.R.; Jhanjhi, N.Z. Convergence of Industry 4.0 and Supply Chain Sustainability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/book/convergence-industry-supply-chain-sustainability/327463 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Sun, J.; Sarfraz, M.; Khawaja, K.F.; Abdullah, M.I. Sustainable Supply Chain Strategy and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Mediated and Moderated Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 895482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K. Convergence Supports Transition to Sustainable Agriculture-Press Release-Convergence News | Convergence. 2024. Available online: https://www.convergence.finance/news/3tPCzaIRKRk4eyH8N5yicR/view (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Bloemer, A.; Minner, S. Unveiling the supply chain: The interaction of sustainability, transparency and digital technologies. In Environmentally Responsible Supply Chains in an Era of Digital Transformation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 141–164. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781803920207/book-part-9781803920207-13.xml (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- DeAngelis, S.F. Supply Chain Risk Management: Dealing with Length & Depth | Supply Chain Minded. 2016. Available online: https://supplychainminded.com/supply-chain-risk-management-dealing-length-depth/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Gimenez, C.; Ventura, E. Logistics-production, logistics-marketing and external integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, P.M. Convergence of Supply Chain Management and Marketing (CSM): A Value Enhancing Strategy in Retail Industry; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1573383 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Zhong, J.; Jia, F.; Chen, X.; Hong, Y.; Yu, Y. Internal and external collaboration and supply chain performance: A fit approach. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.Y.; Tang, C.S. (Eds.) Handbook of Information Exchange in Supply Chain Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 5, Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-32441-8 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Rejeb, A.; Keogh, J.G.; Treiblmaier, H. How Blockchain Technology Can Benefit Marketing: Six Pending Research Areas. Front. Blockchain 2020, 3, 500660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J. Moving beyond Dyadic Ties: A Network Theory of Stakeholder Influences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Krikke, H.; Caniëls, M.C.J. Supply chain integration: Value creation through managing inter-organizational learning. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbe-Costes, N.; Lechaptois, L.; Spring, M. “The map is not the territory”: A boundary objects perspective on supply chain mapping. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1475–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Bryde, D.J. A field-level examination of the adoption of sustainable procurement in the social housing sector. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 982–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J. The Power of and in Stakeholder Networks. In Stakeholder Management; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2017; pp. 101–122. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/s2514-175920170000005/full/html (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Cox, A. Power, value and supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 1999, 4, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W.; Loewenstein, J.; Nigam, A. How Streams of Communication Reproduce and Change Institutional Logics: The Role of Categories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The structuration of socio-technical regimes—Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, G.; Pilbeam, C.; Wilding, R. Nestlé Nespresso AAA sustainable quality program: An investigation into the governance dynamics in a multi-stakeholder supply chain network. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, C.; Schleper, M.C.; Weilenmann, J.; Wagner, S.M. Extending the supply chain visibility boundary: Utilizing stakeholders for identifying supply chain sustainability risks. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Ferro, C.; Hogevold, N.; Padin, C.; Varela, J.C.S. Developing a theory of focal company business sustainability efforts in connection with supply chain stakeholders. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2018, 23, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilro, R.G.; da Cunha, J.F. An exploratory study of Western firms’ failure in the Chinese market: A network theory perspective. J. Chin. Econ. Foreign Trade Stud. 2021, 14, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, C.A.; Durrieu, F. Patterns of international marketing strategy. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 38, 1532–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-F. Understanding the determinants of electronic supply chain management system adoption: Using the technology–organization–environment framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, A. Network structure and innovation: The leveraging of a dual network as a distinctive relational capability. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasti, M.; Mokhtarzadeh, N.G.; Jafarpanah, I. Networking capability: A systematic review of literature and future research agenda. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 37, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. J. Law Econ. 1979, 22, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiblein, M.J. The Choice of Organizational Governance Form and Performance: Predictions from Transaction Cost, Resource-based, and Real Options Theories. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 937–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIvor, R. How the transaction cost and resource-based theories of the firm inform outsourcing evaluation. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, E.A.; Zhao, H.; Ahia, B.N.K. Blockchain technology prospects in transforming Ghana’s economy: A phenomenon-based approach. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2022, 29, 348–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, F.D.; Heinrich, C.J.; Saussier, S.; Shiva, M. Navigating contract renegotiations with sustainability at the helm: Societal benefits and transaction costs. J. Strateg. Contract. Negot. 2023, 7, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, G. The role of asset specificity in the vertical integration decision. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1994, 23, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucio Maia, J.; Lamon Cerra, A.; Gomes Alves Filho, A. Exploring variables of transaction costs in Brazilian automotive supply chains. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketokivi, M.; Mahoney, J.T. Transaction Cost Economics as a Theory of Supply Chain Efficiency. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 1011–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, F.; Seamans, R.; Tadelis, S. Transaction cost economics in the digital economy: A research agenda. Strateg. Organ. 2024, 23, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, A. Reassessing the fundamentals and beyond: Ronald Coase, the transaction cost and resource-based theories of the firm and the institutional structure of production. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, K.D.; Nakos, G. SME Entry Mode Choice and Performance: A Transaction Cost Perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, D.; Zanarone, G.; Ghosh, M. Contracting to (dis)incentivize? An integrative transaction-cost approach on how contracts govern specific investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 1528–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer-Heydenrych, C.F.; Struweg, I. The influence of transaction cost variables on e-buyer satisfaction and loyalty: An e-business-to-consumer retailer context. J. Econ. Financ. Sci. 2021, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, V.K.; Corey, E.R.; Cespedes, F. Transaction Cost Theory: Inferences from Clinical Field Research on Downstream Vertical Integration. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, B.; Sandvik, K.; Haugland, S.A. Antecedents of vertical integration: Transaction cost economics and resource-based explanations. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2009, 15, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Winter, S.G. The co-evolution of capabilities and transaction costs: Explaining the institutional structure of production. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.A.; Ali, M.Y.; Julian, C.C. Antecedents and consequences of SME importers’ relationship with foreign suppliers: A transaction cost approach. In Research Handbook on Export Marketing; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 185–202. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/edcoll/9781781954386/9781781954386.00013.xml (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Saha, P.; Talapatra, S.; Belal, H.M.; Jackson, V. Unleashing the Potential of the TQM and Industry 4.0 to Achieve Sustainability Performance in the Context of a Developing Country. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2022, 23, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, K. Transaction cost theory—Explaining entry mode choices. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2014, 14, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutinelli, M.; Piscitello, L. The entry mode choice of MNEs: An evolutionary approach. Res. Policy 1998, 27, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.; Brailly, J.; Purseigle, F. Strategic outsourcing and precision agriculture: Towards a silent reorganization of agricultural production in France? In Proceedings of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA) Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–5 January 2020; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02942720 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Xiong, M.N.; Wang, T.; Zhao, P. How cultural distance affects the formation of international strategic alliance—An explanation of the transaction costs theory. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2022, 13, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakanov, V.V.; Inshakova, A.O.; Dolinskaya, V.V. Information Society, Digital Economy and Law. In Ubiquitous Computing and the Internet of Things: Prerequisites for the Development of ICT; Popkova, E.G., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahbodi, A.; Zhang, Y.; Watson, G. Sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies: Trade-offs between environmental and cost performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehans, J. Transaction Costs. In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichosz, M.; Goldsby, T.J.; Knemeyer, A.M.; Taylor, D.F. Innovation in logistics outsourcing relationship—In the search of customer satisfaction. LogForum 2017, 13, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, D.W. Transaction costs and competition policy. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2020, 73, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, N.J.; Overbeck, J.R. The social alignment theory of power: Predicting associative and dissociative behavior in hierarchies. Res. Organ. Behav. 2022, 42, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W.; Pozner, J.-E.; Milner, D. Varieties of Political Capital and Power in Organizations: A Review and Integrative Framework. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction cost economics and business administration. Scand. J. Manag. 2005, 21, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, I.R.P.; Hennart, J.-F.; Silverman, B.S.; Ertug, G. Transaction Cost Theory: Past Progress, Current Challenges, and Suggestions for the Future. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 111–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernek-Marszałek, K. Social embeddedness and its benefits for cooperation in a tourism destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, S.; Jin, Y.H.; Fawcett, A.; Bernardes, E. Technological game changers: Convergence, hype, and evolving supply chain design. Production 2018, 28, e20180002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. The Application of Transaction Cost Theory in Supply Chain Management. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3216–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfamy, R.M. Supply Management: A Transaction Cost Economics Framework. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2012, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A. Transaction cost theory: Past, present and future. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Seuring, S.; Beske, P. Sustainable supply chain management and inter-organizational resources: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Mattsson, L.-G. Interorganizational Relations in Industrial Systems: A Network Approach. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1987, 17, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morisse, M.; Horlach, B.; Kappenberg, W.; Petrikina, J.; Robel, F.; Steffens, F. Trust in Network Organizations—A Literature Review on Emergent and Evolving Behavior in Network Organizations. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 4578–4587. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Outsourcing: Transaction cost economics and supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2008, 44, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolze, H.J.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Thornton, L.; Brusco, M.J.; Flint, D.J. Supply chain and marketing integration: Tension in frontline social networks. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 54, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Namdar, J. Generative artificial intelligence in supply chain and operations management: A capability-based framework for analysis and implementation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 6120–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Le, X.C.; Vu, T.H.L. An Extended Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) Framework for Online Retailing Utilization in Digital Transformation: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci, N.; Morgan, R.E. International servitization: Theoretical roots, research gaps and implications. Int. Mark. Rev. 2023, 40, 338–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachroni, A.; Heracleous, L.; Paroutis, S. Organizational Ambidexterity Through the Lens of Paradox Theory: Building a Novel Research Agenda. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2015, 51, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, V.J.; Perez, A.G.; Vrontis, D.; Bedford, D. Viewpoint: Digital resilience, new business models and international entrepreneurship in the era of knowledge-economy. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 1401–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagheb, M.Z.; Ghasemi, B.; Nourbakhsh, S.K. Factors affecting purchase intention of foreign food products: An empirical study in the Iranian context. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1485–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Examining the Dynamics of Entrepreneurial Knowledge and Firm Performance: A Longitudinal Study of Start-ups in Emerging Markets. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 2549–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinda, K.; Wakibi, A. Cultivating sustainability practices through intellectual capital: A qualitative inquiry of medium and large manufacturing firms within an emerging economy. J. Intellect. Cap. 2025, 26, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Sana, S.S.; Banerjee, P. Pricing Strategy and Risk-Averse Flexibility in Sustainable Supply Chain: A Dual-Channel Logistics Process Under Reward Contracts and Demand Uncertainty. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2024, 25, 733–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalih, M.; Chang, C.-H. Enhancing Sustainability in Halal Supply Chain: A Framework for Aligning with ESG and SDGs. In Building Climate Neutral Economies Through Digital Business and Green Skills; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 335–364. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/enhancing-sustainability-in-halal-supply-chain/355389 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Jiang, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, J. Toward Environmental Efficiency: Analyzing the Impact of Green Innovation Initiatives in Enterprises. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2025, 46, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.I.; Mahmood, S.; Khalid, A. Transforming manufacturing sector: Bibliometric insight on ESG performance for green revolution. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Lee, H.-H.; Lim, S. The Effects of Green SCM Implementation on Business Performance in SMEs: A Longitudinal Study in Electronics Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bangwal, D. An assessment of sustainable supply chain initiatives in Indian automobile industry using PPS method. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 9703–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Li, S.; Capaldo, A. Why and how do suppliers develop environmental management capabilities in response to buyer-led development initiatives? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2024, 29, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.; Liu, J.; Ali, E. Incorporating sustainability in organizational strategy: A framework for enhancing sustainable knowledge management and green innovation. Kybernetes 2024, 54, 2363–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Joseph, C.; Adenan, N.Z.C. A systematic literature review approach to explore the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and sustainable supply chain management. Middle East J. Manag. 2024, 11, 539–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Bhutta, M.K.; Sarfraz, M. Green business in the digital age: Sustainable performance in an era of technological advancement and leadership transformation. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 32168–32187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Modgil, S.; Gupta, S. ESG and supply chain finance to manage risk among value chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 471, 143373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadabada, P.K. Analyzing the Impact of ESG Integration and FinTech Innovations on Green Finance: A Comparative Case Studies Approach. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloet, M.; Samson, D. Knowledge and Innovation Management to Support Supply Chain Innovation and Sustainability Practices. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermiatin, F.R.; Handayati, Y.; Perdana, T.; Wardhana, D. Creating Food Value Chain Transformations through Regional Food Hubs: A Review Article. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, T.-F.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Han, Z.-X. Sustainable Partnership: Operational Condition Analysis for Brand Value Co-Creation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; Mention, A.-L. Exploring the food value chain using open innovation: A bibliometric review of the literature. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 1810–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Chahine, J.; Halawi, A. Triple bottom line sustainability and Innovation 5.0 management through the lens of Industry 5.0, Society 5.0 and Digitized Value Chain 5.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xie, G.; Tian, Y. The Influence Mechanism of Strategic Partnership on Enterprise Performance: Exploring the Chain Mediating Role of Information Sharing and Supply Chain Flexibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroson, E.V.; Chowdhury, S.; Mangla, S.K.; Dey, P.K. Unearthing the interplay between organisational resources, knowledge and industry 4.0 analytical decision support tools to achieve sustainability and supply chain wellbeing. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 342, 1321–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Beard, N.; Clegg, T.; Weight, E. The visible body and the invisible organization: Information asymmetry and college athletics data. Big Data Soc. 2023, 10, 20539517231179196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, T.R.; Anderson, W.P.; Song, Y. Rise of Megalopolis as a Mega Knowledge Region: Interactions of Innovations in Transport, Information, Production, and Organizations. In Regional Science Matters: Studies Dedicated to Walter Isard; Nijkamp, P., Rose, A., Kourtit, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, A.D.; Balcell, M.P. Connecting the grids: A review of blockchain governance in distributed energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Nedović-Budić, Z. Transitions of spatial planning in Ireland: Moving from a localised to a strategic national and regional approach. Plan. Pract. Res. 2020, 38, 639–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J.; Mutch, A.; Willcocks, L. Critical Realism in Information Systems Research. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2013, 37, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Saxena, D.; Wall, P.J. The role of information and communications technology in refugee entrepreneurship: A critical realist case study. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 88, e12195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, D.; Engström, A. Using critical realism and abduction to navigate theory and data in operations and supply chain management research. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davvetas, V.; Halkias, G. Global and local brand stereotypes: Formation, content transfer, and impact. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 675–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, A.A.; Chen, Y.; Abrar, M.; Kumar, N.; Razzaq, A. Impact of perceived brand localness and globalness on brand authenticity to predict brand attitude: A cross-cultural Asian perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 34, 1524–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, K.; Schoenmueller, V.; Bruhn, M. Authenticity in branding—Exploring antecedents and consequences of brand authenticity. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayla, J.; Arnould, E.J. A Cultural Approach to Branding in the Global Marketplace. J. Int. Mark. 2008, 16, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. Global Versus Local Consumer Culture: Theory, Measurement, and Future Research Directions. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. Global Brand Building and Management in the Digital Age. J. Int. Mark. 2020, 28, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.; Jevons, C. Global branding and strategic CSR: An overview of three types of complexity. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, B.F.; Bonilla, S.H.; Silva, I.R.; Almeida, C.M.V.B. Cleaner production practices in a medium size gold-plated jewelry company in Brazil: When little changes make the difference. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar da Silva, P.; Cardoso de Oliveira Neto, G.; Ferreira Correia, J.M.; Pujol Tucci, H.N. Evaluation of economic, environmental and operational performance of the adoption of cleaner production: Survey in large textile industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmani, N.; Benhida, K.; Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Elfezazi, S.; Jauhar, S.K. Smart circular product design strategies towards eco-effective production systems: A lean eco-design industry 4.0 framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, A.; Pache, A.-C. Research on Corporate Philanthropy: A Review and Assessment. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 126, 343–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shao, Y.; Han, X.; Chang, H.-L. A road towards ecological development in China: The nexus between green investment, natural resources, green technology innovation, and economic growth. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Ponce, P.; Yu, Z.; Golpîra, H.; Mathew, M. Environmental technology and wastewater treatment: Strategies to achieve environmental sustainability. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.A.; Kersten, W. Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Trendafilova, S. CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, P.; McGuire, M.; Neighbour, G. Eco-design practice in the context of a structured design process: An interdisciplinary empirical study of UK manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 39, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, B.d.S.; Scavarda, L.F.; Gusmão Caiado, R.G.; Santos, R.S.; de Mattos Nascimento, D.L. Corporate social responsibility and circular economy integration framework within sustainable supply chain management: Building blocks for industry 5.0. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.; Guo, C.Q.; Van Luu, B. Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; He, J.; Li, Y. Media spotlight, corporate sustainability and the cost of debt. Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 3989–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D.; Pagell, M. The association between supply chain structure and transparency: A large-scale empirical study. J. Oper. Manag. 2021, 67, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancak, I.E. Change management in sustainability transformation: A model for business organizations. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, J. From servant to driving force: Transforming the role of the supply chain in McDonald’s The Netherlands. J. Supply Chain Manag. Logist. Procure. 2020, 3, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Matsuyama, K. Internal supply chain structure design: A multiple case study of Japanese manufacturers. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 24, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, K.E.; Spalanzani, A. Developing collaborative competencies within supply chains. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2009, 8, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Linden, G. Business models, value capture, and the digital enterprise. J. Organ. Des. 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidpour, H.; Shahrokhi, M.; Bernard, A. A multi-objective programming approach, integrated into the TOPSIS method, in order to optimize product design: In three-dimensional concurrent engineering. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 64, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.; Chiang, A.H.; Sambamurthy, V.; Setia, P. Lean vs. Agile Supply Chain: The Effect of IT Architectures on Supply Chain Capabilities and Performance. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P.; Krapfel, R. Collaboration and Competition in Buyer-Supplier Relations: The Role of Information in Supply Chain and e-Procurement Impacted Relationships; Spotts, H.E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Levine, C.H. An Interorganizational Analysis of Power, Conflict, and Settlements in Public Sector Collective Bargaining. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2014, 70, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.M.; Greenwood, K. Visualizing CSR: A visual framing analysis of US multinational companies. J. Mark. Commun. 2013, 21, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmola, G.A.; Kumar, V. A strategic model for attracting and retaining environmentally conscious customers in E-retail. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Antony, R.; Sharma, A.; Daim, T. Can smart supply chain bring agility and resilience for enhanced sustainable business performance? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 36, 501–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, A.M.; Sheeja Ran, S. Enhancing supply chain management with deep learning and machine learning techniques: A review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tliche, Y.; Taghipour, A.; Canel-Depitre, B. An improved forecasting approach to reduce inventory levels in decentralized supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 287, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Sorooshian, S.; Adeleke, A.Q. Green and low carbon matters: A systematic review of the past, today, and future on sustainability supply chain management practices among manufacturing industry. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, S.; Lilhore, U.K.; Simaiya, S.; Radulescu, M.; Belascu, L. Improving efficiency and sustainability via supply chain optimization through CNNs and BiLSTM. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, P.M. Convergence of Supply Chain and Marketing (CSM) for Building Competitive Advantages; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindley, C.; Oxborrow, L. Aligning the sustainable supply chain to green marketing needs: A case study. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wan, Y. A Study of Cross-Border E-Commerce Supply Chain Research Rrends: Based on Knowledge Mapping and Literature Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC), Chongqing, China, 24–26 May 2024; pp. 1944–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaran, S. Maximizing Operational Efficiency: Utilizing Blockchain for Comprehensive Tracking and Visibility throughout the Supply Chain. Int. J. Supply Chain Logist. 2024, 8, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.R. Sustainable Food Revolution: The industry 5.0-Permission Marketing Convergence. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Arts Sci. Technol. 2024, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, L.; Trivellato, B.; Martini, M.; Marafioti, E. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals Through Collaborative Innovation: Evidence from Four European Initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 1075–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Carlos Fernandez de Arroyabe, J.; Sena, V.; Gupta, S. Stakeholder diversity and collaborative innovation: Integrating the resource-based view with stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellram, L.M.; Ueltschy Murfield, M.L. Supply chain management in industrial marketing–Relationships matter. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 79, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, S. Balancing Marketing Technology and IT at a Fortune 500 Firm. Chief Marketing Technologist. 2013. Available online: https://chiefmartec.com/2013/01/balancing-marketing-technology-and-it-at-a-fortune-500/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Golia, N. Nationwide CMO: ‘I Have Double-Digit Million Dollars in IT Projects’. Insurance & Technology. 2013. Available online: https://www.insurancetech.com/management-strategies/nationwide-cmo-i-have-double-digit-milli/240150821 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Maltoni, V. Companies that Have Managed the Convergence of IT and Marketing Well. Conversation Agent-Valeria Maltoni. 2014. Available online: https://www.conversationagent.com/2013/08/companies-that-have-managed-the-convergence-of-it-and-marketing-well.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Shahzad, S.K.; Masudin, I.; Zulfikarijah, F.; Nasyiah, T.; Restuputri, D.P. The effect of supply chain integration, management commitment, and sustainable supply chain practices on non-profit organizations performance using SEM-FsQCA: Evidence from Afghanistan. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.-H. Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.; Bajaba, S. The role of supply chain resilience and absorptive capacity in the relationship between marketing–supply chain management alignment and firm performance: A moderated-mediation analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 38, 1545–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hbr. Why Procurement and Supply Chain Functions Need to Converge-SPONSOR CONTENT FROM GEP. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021. Available online: https://hbr.org/sponsored/2021/10/why-procurement-and-supply-chain-functions-need-to-converge (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Tornatzky, L.; Fleischer, M. The Process of Technology Innovation; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Masekwana, F.; Jokonya, O. Factors affecting the adoption of RFID in the food supply chain: A systematic literature review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 8, 1497585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menanno, M.; Savino, M.M.; Accorsi, R. Digitalization of Fresh Chestnut Fruit Supply Chain through RFID: Evidence, Benefits and Managerial Implications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stream of Literature | Query | Justification of Generating Queries |

|---|---|---|

| International Marketing | “International Marketing” | The term directly reflects the field of research that aims to identify the ideas, methods and challenges of marketing at the international level. It provides the basis for effectively collecting specific and relevant literature related to international marketing. |

| Sustainable supply chain management | “Sustainable supply chain” | Exploring the terminology related to sustainable supply chains is essential to highlight the literature related to supply chain management practices as per sustainability principles. It helps to understand the concept of a sustainable supply chain and explore research on it. |

| Institutional technologies | “Institutional technologies” | This search query is designed to search the literature in the field of institutional technologies, examining the nature, role and impact of these technologies. Thus, it provides a direct and comprehensive approach to exploring the literature related to institutional technologies. |

| Convergence | (“International Marketing” OR “Marketing” OR “Sustainable marketing” OR “Institutional marketing”) AND (“supply chain” OR “Supply chain management” OR “SCM” OR “Sustainable supply chain” OR “Sustainable SCM” OR “Sustainable institution”) AND (“Institutional technologies” OR “Institutional technologies” OR “Institutionalization” OR “Institution”) | This complex query is designed to explore the convergence between them by simultaneously combining the topics of International Marketing, Sustainable Supply Chain and Institutional Technologies. This is helpful in finding the literature on the intersection of the three fields and clarifying the relationship between them. |

| Factors | Dimension | Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Marketing | Adaptation Foreign operation Value creation | Business model innovation Restructuring Competitive advantage | Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci & Morgan [116]; Papachroni et al. [117]; Sadeghi et al. [118]; Sagheb et al. [119]; Y. Chen [120] |

| Sustainable supply chain | Cleaner production process ESG CSR | Eco-friendly production Environment, social, governance Ethics | Alinda & Wakibi [121]; Barman et al. [122]; Ghalih & Chang [123]; Jiang et al. [124]; K. I. Khan et al. [125]; Kim et al. [126]; Kumar & Bangwal [127]; Qiao et al. [128]; Rasheed et al. [129]; Said et al. [130]; Sun et al. [131] |

| Convergence | Integration Information sharing Engagement | Value chain Department alignment Transparency Data structure Stakeholder | Agrawal et al. [132]; Dadabada [133]; Gloet & Samson [134]; Hermiatin et al. [135]; Hsiung et al. [136]; Misra & Mention [137]; Mouazen et al. [138]; Yang et al. [139]; Yaroson et al. [140] |

| Institutional technologies | Technology Organization Environment | Innovation Flexibility Restructuring Environment | Greene et al. [141]; Lakshmanan et al. [142]; Valdivia & Balcell [143]; Williams & Nedović-Budić [144] |

| Journals | Articles |

|---|---|

| Supply Chain Management | 21 |

| International Journal of Production Economics | 5 |

| Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing | 5 |

| Sustainability (Switzerland) | 5 |

| Journal of Operations Management | 4 |

| Markets, Marketing and Developing Countries: Where we stand and where we are Heading | 4 |

| Article Title | Citation Count |

|---|---|

| A multi-theoretic perspective on trust and power in strategic supply chains | 496 |

| Defining the concept of supply chain quality management and its relevance to academic and industrial practice | 393 |

| A transaction cost approach to supply chain management | 295 |

| Empirical analysis of supplier selection and involvement, customer satisfaction, and firm performance | 246 |

| Farmers’ markets: Consuming local rural produce farmers’ markets: Local rural produce | 226 |

| Organizational learning as a strategic resource in supply management | 224 |

| “Measuring the immeasurable”—Measuring and improving performance in the supply chain | 202 |

| The antecedent role of quality, information sharing and supply chain proximity on strategic alliance formation and performance | 201 |

| Firms | Key Person | Designation | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kimberly-Clark | Mayur Gupta | Global Head of Marketing Technology | It is a gradual mindset shift, an effort to strike a balance between the rigor, process and focus on standardization, scale and globalization of an IT organization and the need for agility, nimbleness, and innovation of marketing technology to deliver excellence for our consumers. |

| Nationwide | Matt Jauchius | EVP and CMO | The IT and the marketing people are aligned almost all the time on advanced and emerging applications. We actually don’t get in one another’s way on things like that—what gets in the way is boring things like funding, swinging into the change process, and legacy systems. We have a strict policy that if you want to interface with IT and get funding for something, you have to go through the marketing technologist. |

| Examples | Incident | IT Bottleneck | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supply chain failure of KFC (2018) | KFC UK changed its logistics provider from Bidvest to DHL in 2018, resulting in the supply chain system being disrupted. The new provider’s central warehouse and technology infrastructure were not compatible with KFC’s existing operational systems. | Attempts to adopt new logistics technology (such as IoT sensors and blockchain traceability) in the integration process created inconsistencies with older data management systems, resulting in data incompatibility and real-time monitoring failure. | Only 266 of the 870 restaurants were able to operate, causing financial losses and severe damage to the brand’s reputation. |

| Technical complexities in Nike’s supply chain | Nike introduces AI and advanced analytics to diversify its supply chain and improve CSR. | Difficulties in synchronizing international marketing data (such as cultural preferences and environmental standards) with new technology platforms in the supply chain (such as blockchain) limited the effective use of technology. | Production costs increased by 15% due to non-complete integration of technology. |

| Failure of Hershey’s AI integration | Hershey introduced AI and advanced analytics to prevent supply chain disruptions. | The structural inconsistency of data between marketing and supply chain databases made training AI models difficult, resulting in inaccurate predictions | 30% of supply chain decisions proved to be wrong, reducing productivity by 20% |

| Future Research Questions |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.N.; Shao, Z. Dimensions of Institutional Technologies and Its Role in Convergence of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and International Marketing: Systematic Literature Review. Systems 2025, 13, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070502

Khan MN, Shao Z. Dimensions of Institutional Technologies and Its Role in Convergence of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and International Marketing: Systematic Literature Review. Systems. 2025; 13(7):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070502

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Nafees, and Zhen Shao. 2025. "Dimensions of Institutional Technologies and Its Role in Convergence of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and International Marketing: Systematic Literature Review" Systems 13, no. 7: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070502

APA StyleKhan, M. N., & Shao, Z. (2025). Dimensions of Institutional Technologies and Its Role in Convergence of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and International Marketing: Systematic Literature Review. Systems, 13(7), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13070502