Abstract

Urgency and severity of climate change impacts have become increasingly prominent, making the enhancement of corporate climate risk disclosure (CCRD) a shared demand among regulators, investors, and the general public. From the perspective of irrational behavioral traits, this paper utilizes a sample of A-share-listed companies in China from 2008 to 2022 to empirically examine the impact of executives’ overseas experiences on CCRD and its underlying mechanisms. To measure firm-level climate risk disclosure, we employ machine learning-based textual analysis techniques and match the constructed disclosure indicators with firms’ financial data. The results demonstrate that executives with overseas experience significantly enhance the level of CCRD, and this effect remains consistent after a series of robustness tests. This effect operates through the dual paths of “climate attention allocation enhancement” and “management myopia mitigation”. Moreover, the positive impact of overseas experience is more pronounced among firms in climate-sensitive industries and regions with lower climate awareness. A further analysis of executive overseas experience characteristics shows that executives with experience in developed economies and those with international educational backgrounds exhibit a stronger influence in promoting CCRD. Additionally, an investigation into the economic consequences demonstrates that executives with overseas experiences not only improve firms’ ESG performances but also help reduce ESG rating discrepancies, reinforcing the beneficial role of overseas exposure in corporate governance. The findings not only provided micro-level empirical evidence for the effectiveness of talent recruitment policies in emerging economies but also yielded critical policy implications for regulatory bodies to refine climate disclosure frameworks and enable enterprises to leverage opportunities in low-carbon transition.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the frequent occurrence of extreme climate events, including heatwaves, torrential rainfall and flooding, and cold spells, has exerted substantial impacts on natural ecosystems while progressively extending into economic systems [1]. According to Global Risks Report 2020, the number of climate-related natural disasters surged from 4212 incidents in the period of 1980–1999 to 7348 in 2000–2019. Meanwhile, the economic losses attributable to these disasters nearly doubled, rising from $1.63 trillion in 1980–1999 to $2.97 trillion in 2000–2019 [2]. Therefore, the urgency and severity of climate change impacts are becoming increasingly evident, underscoring the critical importance of managing climate risks, seizing transition opportunities, and facilitating climate-friendly investment and financing for sustainable development. Against this backdrop, capital markets are witnessing a growing demand for standardized and transparent climate risk information. Enhancing corporate climate risk disclosures (CCRD) has thus emerged as a shared priority among regulators, investors, and the broader public [3].

CCRD represents a strategic decision-making process that entails multiple challenges, including high integration costs, inconsistent standards, managerial inertia, and long implementation cycles [4]. Effective CCRD not only requires firms to possess sufficient resource endowments but also demands that executives exhibit an entrepreneurial spirit in exploring innovative disclosure practices. As the central drivers of corporate strategy, executives function as the “neural hub” in climate-related information production [5], and their characteristics profoundly shape CCRD behavior. However, the existing literature has paid relatively little attention to the impact of executive attributes on CCRD.

This study examined the role of executives’ overseas experiences in shaping CCRD, motivated by the following considerations. First, as emerging economies continue to grow and implement talent attraction policies, the influx of overseas-experienced professionals has become increasingly prominent [6]. Investigating the impact of executives’ overseas experience on CCRD provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of talent recruitment policies in developing economies and the role of returnee executives in facilitating green and low-carbon transitions. Second, emerging economies have traditionally pursued extensive growth models, often placing less emphasis on environmental protection and climate-related issues. In contrast, developed economies, such as EU countries and the United States, have established relatively sophisticated and operational climate risk disclosure frameworks [7]. This “disclosure practice gap” may imprint distinct cognitive patterns and value orientations on executives with overseas experience, subsequently influencing corporate behavior. Thus, examining this phenomenon offers a promising avenue for understanding the relationship between executives’ global exposure and climate risk disclosure practices. Third, research on the impact of executive heterogeneity on CCRD remains underdeveloped. Analyzing the role of executives’ overseas experiences in climate risk disclosure not only enriches the literature on executive decision-making but also provides theoretical guidance for corporate governance and disclosure policy formulation.

In light of the above analysis, this study utilized a sample of A-share-listed companies in China from 2008 to 2022 to empirically examine the impact of executives’ overseas experiences on CCRD and its underlying mechanisms. This research may contribute to the existent literature in three aspects: Firstly, it pioneers a novel perspective by investigating the irrational behavioral traits of executives in climate risk disclosure decisions. While existing research predominantly examines determinants through corporate characteristics and conventional managerial attributes under rational actor paradigms [4], our work bridges psychological, sociological, and managerial theories. Grounded in upper echelons theory and imprinting theory, we analyzed how the institutional “imprints” formed by cross-border disparities in climate disclosure practices systematically influence overseas-experienced executives’ decision-making processes. This approach significantly extends the theoretical boundaries of climate disclosure research beyond traditional economic frameworks.

Secondly, the research substantially advances understanding of the economic consequences of executive global mobility. Prior studies emphasized overseas experiences’ impacts on innovation [8] and financial disclosure [9], while largely neglecting non-financial disclosures. As returnee executives constitute an increasingly critical demographic in corporate leadership, our identification of dual mechanisms—enhanced climate attention allocation and reduced managerial myopia—provides seminal evidence about how transnational human capital reshapes strategic environmental disclosures. This not only complements the leadership characteristic literature but also responds to urgent calls for ESG-related governance research.

Thirdly, the findings offer policy-relevant insights for emerging countries’ sustainable development agendas. By demonstrating that returnee executives significantly improve climate disclosure quality and ESG performance, we established an empirical foundation for synergizing high-skilled immigration policies with environmental governance. Our heterogeneity analysis further specified that optimal policy effectiveness requires a differentiated utilization of returnees with Western educational/professional imprints and strategic allocation of global talent in corporate governance structures. These evidence-based recommendations provide actionable pathways for leveraging human capital globalization to accelerate low-carbon transitions.

2. Institution Background, Literature Review, and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Institution Background

The global economic landscape has witnessed a paradigm shift in corporate accountability, with escalating climate volatility, labor disputes, and governance failures propelling Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations to the forefront of regulatory and market priorities. ESG disclosure has emerged as a critical mechanism for climate risk identification, green finance mobilization, and corporate decarbonization strategies, constituting an indispensable component of global net-zero transitions [10]. This institutional evolution has been accelerated through multilateral standardization efforts, notably under United Nations’ frameworks, as systematically cataloged in Table 1. Transatlantic leadership in disclosure maturity is evident, with EU and US standards constituting 72% of globally adopted frameworks. Within ESG architectures, climate disclosures—the environmental (E) pillar—have progressed from elementary greenhouse gas accounting to integrated systems assessing organizational climate resilience. The synergistic adoption of CDP, CDSB, and TCFD standards has established an interconnected ecosystem, achieving 60% TCFD-aligned disclosure rates among Western firms by 2021 versus 36% in Asia-Pacific counterparts [11].

Table 1.

Institutional evolution of major ESG/climate disclosure frameworks.

With the progressive standardization of global climate risk disclosure frameworks and enhanced corporate reporting practices, climate risk information has become deeply integrated into professional workflows and societal systems. This integration establishes critical data infrastructure for multiple stakeholders: investors conducting climate risk assessments, financial regulators analyzing systemic climate-related financial vulnerabilities, occupational safety authorities mitigating workforce exposure to climate hazards, and enterprises identifying climate-resilient business opportunities. Concurrently, the evolving operational demands underscore the imperative for climate change education reform. UNESCO advocates for mainstreaming climate education as a core curricular component across nations, proposing the comprehensive integration of climate-related knowledge systems, technical competencies, value orientations, and behavioral frameworks into multi-disciplinary learning ecosystems. This transformative educational paradigm aims to cultivate three-dimensional climate citizenship: enhancing public climate literacy, empowering youth with carbon-neutral lifestyle decision-making capabilities, and nurturing next-generation climate solution innovators.

Developed economies have initiated systemic reforms in climate education. For example, Canada’s nationwide pilot since 2016 exemplifies this trend, where 10 model schools have embedded climate action competencies across curricula. This pedagogical architecture equips learners with adaptive capacities for climate uncertainty mitigation. In contrast, emerging economies prioritize economic expansion and employment stabilization, resulting in divergent ESG implementation trajectories. As the largest emerging economy, China’s ESG disclosure standards exhibit delayed development characterized by fragmented frameworks and non-uniform metrics across different sectors. Simultaneously, corporate entities demonstrate dual deficiencies in climate governance literacy: an insufficient conceptual understanding of ESG reporting obligations coupled with a limited technical capacity for implementation, particularly manifesting in a suboptimal disclosure quality of climate risk information. This institutional gap extends to the educational domain, where climate-focused curricula in compulsory education systems and science popularization initiatives lag significantly behind international benchmarks, while failing to leverage education’s crucial role in cultivating nationwide climate literacy and enhancing public sensitivity to environmental challenges.

Demographic shifts present new leverage points for China’s climate governance. Accelerated by robust economic growth and preferential talent policies, the country is experiencing an unprecedented reverse brain drain. The Global Talent Mobility and Governance Report quantifies this transition, positioning China as Asia’s emerging talent hub with expanding cohorts of returnee professionals [12]. Crucially, executives with international exposure carry institutional knowledge of advanced climate disclosure practices. Their experiential learning undergoes cognitive internalization processes, creating distinctive professional imprints that translate into enhanced corporate climate risk management architectures. This human capital transformation may catalyze qualitative leaps in Chinese enterprises’ climate governance capabilities through three transmission mechanisms: operational knowledge transfer, organizational practice hybridization, and disclosure paradigm innovation. Consequently, executives with overseas experience develop distinctive professional imprinting through sustained engagement with advanced climate disclosure practices.

2.2. Related Literature

2.2.1. Economic Consequences of Executives’ Overseas Experiences

Scholarly investigations into executives with overseas exposure predominantly draw upon imprint theory and upper echelons theory [13]. These studies emphasized three core advantages arising from the cross-border mobility of managerial talent: enhanced human capital, diversified value systems, and expanded social networks. From a human capital perspective, executives with overseas experience demonstrate superior professional competencies that help mitigate managerial myopia and foster technological innovation [14]. Their exposure to divergent value systems cultivates distinctive cognitive frameworks characterized by heightened individualism and risk tolerance. Comparative analyses reveal that internationally experienced executives outperform their domestic counterparts in cross-cultural communication competencies, a critical factor in overcoming transnational merger barriers and improving overseas acquisition performance [15]. Furthermore, the compensation structure implications were examined by Conyon et al. [16], who documented that overseas exposure reduces executives’ egalitarian values while strengthening individualistic tendencies, consequently widening intra-firm pay disparities. Corporate social responsibility outcomes are positively influenced through executives’ immersion in Western CSR frameworks, as demonstrated by Zhang et al. [17] through improved CSR implementation metrics.

On the other hand, Granovetter’s [18] embeddedness theory provided the foundation for understanding how multinational experiences shape executives’ social capital. Dai et al. [19] identified distinctive entrepreneurial advantages among returnee executives, particularly their ability to leverage international networks for opportunity identification and business expansion. Moreover, Hao et al. [20] proposed a dual-network advantage framework: returnee executives effectively bridge domestic and international networks, creating synergistic effects that significantly boost technological innovation performance. This bicultural networking capability enables simultaneous access to localized knowledge bases and global innovation frontiers.

2.2.2. Determinants of Corporate Climate Risk Disclosure (CCRD)

The existing literature identified institutional environments and organizational characteristics as primary determinants of CCRD. From an institutional perspective, Li and Yao [21] revealed how Confucian culture, as an informal institution, enhances CCRD through reputation building, agency conflict mitigation, and environmental accountability reinforcement. Organizational determinants encompass firm size [22], decarbonization performance [23], financial health [24], and institutional ownership structures, particularly foreign institutional holdings [3]. In terms of internal drivers, Hampton and Li [25] argued that firm financial structure characteristics such as asset strength, profitability, and operating cash flow are significantly associated with climate risk disclosure behaviors. Corporate governance mechanisms significantly influence CCRD outcomes. Song and Xian [26] demonstrated that institutional investors’ site visits curb managerial opportunism in climate information withholding. Although executive influence remains underexplored, Daradkeh et al. [4] identified managerial ability as a critical factor, where high-ability executives exhibit greater propensity for long-term climate adaptation investments and associated disclosures.

The current literature predominantly followed a macro-to-micro analytical paradigm, emphasizing external institutional forces and internal organizational attributes. However, limited attention has been paid to the central decision-makers of disclosure practices: corporate executives. The singular focus on managerial ability remains confined to rational actor paradigms under agency theory, neglecting the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of executive decision-making. Emerging interdisciplinary research integrating upper echelons theory, imprinting theory, and behavioral finance provides compelling evidence that executives operate under bounded rationality, with their prior experiences fundamentally shaping cognitive schemas, value orientations, and decision-making heuristics [27]. Nevertheless, few studies applied upper echelons or imprinting theory to examine how managerial heterogeneity influences climate risk disclosure. By analyzing overseas experience as a formative imprinting event, this study transcends the rational-actor paradigm, offering novel insights into the cognitive drivers of corporate climate transparency.

2.3. Hypotheses’ Development

2.3.1. Executives’ Overseas Experiences and Corporate Climate Risk Disclosure

Building on Hambrick and Mason’s premise that “organizations reflect the values and cognitive frames of their top managers”, we posited that executives’ international experiences systematically influence their attention allocation and prioritization of climate-related risks. Unlike traditional economics, which assumes managerial homogeneity and perfect rationality, upper echelons theory emphasizes that executives’ backgrounds (e.g., education, career paths, international exposure) create distinct cognitive schemas. These schemas, in turn, affect how they interpret strategic issues like climate risk [28]. Complementing this, imprinting theory explains the enduring effects of early career experiences on decision-making patterns. As Marquis and Tilcsik [29] noted, “imprints formed during sensitive periods of professional development persist over time, shaping later behaviors”. Executives exposed to stringent climate regulations or sustainability-focused corporate cultures during their international assignments develop a lasting cognitive imprint. This imprinting mechanism not only enhances their technical understanding of climate risk quantification (e.g., TCFD frameworks) but also reduces myopic tendencies by fostering long-term strategic orientations [30].

From the perspective of knowledge and technical expertise, imprinting theory explains how prolonged engagement with advanced climate governance systems in developed economies leaves enduring cognitive imprints on executives. During their overseas assignments, these individuals internalize technical frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and EU sustainability reporting standards. This process creates a reservoir of specialized human capital that persists beyond their international tenure. When repatriated, executives draw upon these imprinted skills to decode complex disclosure requirements, accurately assess enterprise-specific climate risks, and implement globally aligned reporting practices [31]. The reduced compliance costs associated with this expertise, as posited by the upper echelons theory, enable managers to reallocate cognitive resources toward strategic disclosure optimization rather than procedural adherence [32].

In the domain of management philosophy, the upper echelons theory clarifies how overseas experiences reconfigure executives’ cognitive schemas regarding corporate competitiveness. Exposure to stakeholder-centric governance models prevalent in Western markets—where climate transparency is increasingly tied to market access and investor trust—cultivates an international strategic vision. Executives imprinted with these norms come to view climate disclosure not merely as a regulatory obligation but as a mechanism for enhancing global legitimacy and innovation signaling [33]. This philosophical shift, rooted in imprinting theory’s emphasis on formative professional experiences, drives the institutionalization of climate accountability within corporate agendas. For instance, returnee executives often champion the adoption of Science-Based Targets (SBTs) or circular economy principles, reflecting a synthesis of imprinted sustainability values and upper echelon strategic prioritization [34].

The resource and network dimension further demonstrates the theories’ complementary roles. Imprinting theory accounts for the enduring social capital acquired through international collaborations—relationships with ESG auditors, sustainability consultants, and transnational policymakers. These networks provide ongoing access to emerging standards like the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), enabling executives to anticipate regulatory shifts proactively [35]. Simultaneously, the upper echelons theory illuminates how such networks influence attention structures at the highest organizational levels [36]. Executives embedded in global sustainability communities disproportionately allocate boardroom discussions and budgetary resources to climate risk mitigation, effectively transforming external network advantages into internal governance priorities. Based on the above analysis, this study proposed Hypothesis H1.

Hypothesis H1:

Executives’ overseas experiences improve corporate climate risk disclosure.

2.3.2. Executives’ Overseas Experiences, Climate Attention Allocation, and CCRD

Executive attention is constrained by personal and firm resources and tends to focus on high-value or legitimacy issues [37]. Under the premise of limited rationality, attention allocation can reflect management’s perceptions and judgements about the firm’s strategic direction, core values, and priorities, which include deciding which issues to focus on, how much resources to allocate to them, and which issues to prioritize. Executives with overseas experience often exhibit a high level of concern for environmental issues and climate risks. Specifically, on the one hand, overseas experiences reshape executives’ cognitive frameworks, enhancing their sensitivity to climate-related topics [9]. Renowned overseas universities, particularly those that accord significant importance to corporate social responsibility and sustainability education, facilitate this process through the provision of relevant courses and extensive case studies. Executives thereby experience a notable improvement in their awareness and sensitivity to climate issues, leading to a proactive allocation of greater attention to climate-related matters in their corporate management. On the other hand, overseas experience serves as a key “imprinting event” that shapes executives’ long-term perceptions of climate risk. Drawing upon the stigma theory, executives encounter varied concepts of social responsibility and develop an understanding of the expectations of diverse cultures and markets concerning corporate behaviors. This enables executives to adopt a multifaceted perspective when confronted with climate-related issues and to maintain standards of corporate ethics and responsibility in diverse environments. When management pays high attention to climate issues, it will be more proactive in collecting and organizing information related to corporate climate risk and disclosing it comprehensively and accurately to stakeholders, so as to enhance the transparency of corporate response to climate risk, shape a good corporate image, and promote sustainable corporate development. Based on the above analysis, we proposed Hypothesis H2.

Hypothesis H2:

Executive overseas experience promotes corporate climate risk disclosure by increasing the allocation of management attention to climate.

2.3.3. Executives’ Overseas Experiences, Management Myopia, and Corporate Climate Risk Disclosure

In corporate operations, the decision-making perspective of management has a profound impact on corporate behavior, with decisions regarding the disclosure of climate risk information being influenced by managerial myopia. From a global market insight perspective, executives with overseas experience have direct exposure to diversified business ecosystems, industry development models, and macroeconomic trends. This enables them to view corporate development from a longer-term, more comprehensive, and forward-thinking perspective. When confronted with uncertain risks, overseas experience shapes executives’ risk-taking capabilities through cross-cultural adaptation, assisting managers in balancing the relationship between risk aversion and long-term profitability, and mitigating the avoidance mindset towards the “high-investment, long-cycle” characteristics of corporate decisions. In terms of reputational signaling, executives who have been immersed in the global business environment for a long time are acutely aware of the legitimacy that international stakeholders expect from corporate climate responsibility [38]. In order to circumvent the consequences of “reputational sanctions” and to compete for “green reputational capital”, returnee executives will proactively mitigate their myopia, opting instead to employ highly transparent climate disclosures to convey “credible commitments” to the global market. Therefore, when confronted with climate risks, management, out of consideration for the company’s long-term development, may mitigate the short-sightedness and promote the proactive disclosure of high-quality climate risk information [39]. This is to adapt to the global market’s requirements for corporate environmental responsibility, thereby laying a solid foundation for the company’s long-term development. Based on the above analysis, we proposed Hypothesis H3.

Hypothesis H3:

Executive overseas experience promotes corporate climate risk disclosure by mitigating management myopia.

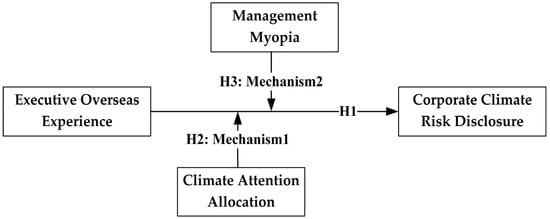

The theoretical derivation and hypothetical relationships of this research are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research framework.

3. Data, Variables, and Method

3.1. Data Source and Sample Selection

To mitigate the potential confounding effects of accounting standard changes, our study examined A-share-listed firms in China from 2008 to 2022. Our study period began in 2008 to align with the launch of China’s “Thousand Talents Plan”, a pivotal national strategy to reverse the “brain drain” by incentivizing overseas-educated professionals to return to China. This policy triggered a marked increase in returnee executives. Starting in 2008 allowed us to capture the formative phase of this talent influx and its long-term imprinting effects on corporate governance. Also, the study period ended in 2022 due to limitations in data availability.

Following established empirical conventions in corporate finance research, we implemented rigorous sample selection criteria: (1) excluding financial and insurance sector firms due to their unique regulatory environment and reporting requirements; (2) removing Special Treatment (ST) and *ST firms with abnormal financial conditions; and (3) eliminating observations with missing critical variables. This systematic filtration process yielded a final sample of 8266 firm-year observations.

The study drew on multiple authoritative data sources to ensure measurement validity. Executive team characteristics and corporate financial data were sourced from the CSMAR and Wind databases. To capture climate risk disclosure levels, we manually collected and coded information from corporate social responsibility reports, with ESG/sustainability reports serving supplementary roles, employing content analysis techniques consistent with the recent ESG literature. To avoid the interference of extreme values, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1 and 99% levels in this study.

3.2. Definition of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Climate Risk Disclosure

Our methodology began with the construction of a robust lexicon for climate risk disclosure, grounded in cross-language validation and machine learning advancements. Drawing on the foundational work of Sautner et al. [40] as well as Song & Xian [26], we adopted their machine learning-derived English keyword set as the initial seed words. To adapt these terms to Chinese financial contexts, we implemented a triple-translation protocol using Google Translate, DeepL Translate, and CNKI Translation Assistant, three industry-standard tools. This multi-tool approach mitigated translation bias and ensured semantic fidelity. The translated terms underwent a rigorous three-phase screening process: first, eliminating words with meanings inconsistent with climate risk (e.g., general environmental terms); second, resolving ambiguities through a contextual analysis of 500 randomly sampled ESG reports; and third, cross-validating results with a panel of five sustainability reporting experts, achieving strong inter-rater reliability. This process yielded 48 Chinese seed words spanning three dimensions of climate risk—physical risks, transition risks, and stakeholder adaptation.

To address the limitations of traditional dictionary-based and supervised methods in semantic expansion, we employed a dual machine learning architecture. The primary expansion leveraged Word2Vec [41], which generated contextualized word vectors based on the surrounding text, effectively capturing semantic relationships through cosine similarity. This approach overcame the sparse representation problem inherent in Chinese financial texts while minimizing human subjectivity. Using a skip-gram model with a window size of 5 and 300-dimensional embeddings, we expanded the seed set to 120 contextually relevant terms, filtering out low-similarity candidates (<0.65 cosine similarity) to reduce noise. To further enhance semantic sensitivity, we augmented this with ELMO [42], a deep neural network model that addresses polysemy by generating context-dependent embeddings. The composite disclosure metric was calculated as the normalized ratio of climate-related terms to total report word count, scaled by 120 to preserve cross-firm comparability.

Validation tests confirmed the robustness of our approach. Cross-model consistency checks revealed high overlap between Word2Vec and ELMO lexicons (Jaccard similarity index = 0.83), with coefficient stability in key models (Δβ < 10%). External benchmarking against Sautner et al.’s [41] machine-learning dictionary showed 70% term overlap, while alignment with CDP Climate Disclosure Scores for 120 matched firms demonstrated strong correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.68, p < 0.01). Empirical validation further stratified firms into terciles based on disclosure scores. Notably, 65% of firms designated as “ESG Leaders” in the 2019 China Listed Companies ESG Report fell into the high-disclosure group (Group C), with zero false positives in the low-disclosure tier (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.003). The detailed construction process of the climate risk information disclosure variable can be found in Appendix A.

Based on established taxonomies and definitions from reputable sources such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy, the list of climate risk-related words in Table 2 reflects three conceptual dimensions of climate risk exposure: (1) Physical risks: These are risks resulting from climate change that can be event-driven (acute) or longer-term shifts (chronic) in climate patterns. Acute physical risks refer to those that are event-driven, including the increased severity of extreme weather events, such as cyclones, hurricanes, or floods. Chronic physical risks refer to longer-term shifts in climate patterns (e.g., sustained higher temperatures) that may cause sea level rise or chronic heatwaves. Examples in the table include “storm surge” and “water resources”, which are directly impacted by these acute and chronic changes. (2) Transition risks: These risks arise from the process of adjustment towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy. Transitioning to a lower-carbon economy may entail extensive policy, legal, technology, and market changes to address mitigation and adaptation requirements related to climate change. Examples include “carbon tax” and “renewable energy”, which are directly related to the policy and technological shifts required for this transition. (3) Stakeholder adaptation: This category encompasses the actions and strategies adopted by various stakeholders to adapt to the effects of climate change. It includes efforts by governments, businesses, and communities to enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability to both physical and transition risks. Examples include “circular economy” and “green finance”.

Table 2.

Climate risk-related vocabulary.

To further validate the effectiveness of our climate risk disclosure metric, we conducted industry-level benchmarking against established high-carbon sectors identified in the climate transition risk literature. Drawing on the Dutch Central Bank’s framework for transition-sensitive industries (fossil energy production/logistics, power generation, heavy industry, transportation, and agriculture) and China’s official classification of 13 high-carbon industries (petrochemicals, chemicals, construction materials, steel, nonferrous metals, etc.), we calculated industry-averaged climate risk disclosure scores using the methodology. As shown in Table 3, the results aligned closely with theoretical expectations about sectoral exposure to climate transition risks.

Table 3.

Industry-averaged climate risk disclosure scores.

The Water Conservancy, Environment, and Public Infrastructure Management sector exhibited the highest average disclosure intensity (0.726), reflecting heightened climate risk awareness in infrastructure sectors vulnerable to physical risks like extreme weather and flooding. Electricity, Heat, Gas, and Water Production/Supply—a core transition-risk sector—ranked second (0.667), consistent with the Dutch Central Bank’s identification of power generation as systemically exposed to decarbonization pressures. Notably, Manufacturing (0.572) and Mining (0.411), both classified as high-carbon industries under China’s industrial taxonomy, demonstrated significantly elevated disclosure levels compared to low-carbon sectors like Wholesale/Retail (0.134) and Information Technology (0.107). This pattern robustly validated our measurement approach: industries facing acute transition risks (e.g., energy-intensive manufacturing, mining) or physical risks (e.g., water/environmental infrastructure) systematically disclose more climate risk information. The Scientific Research/Technical Services sector’s relatively high score (0.449) further corroborated this logic, as these firms often engage in climate-related R&D activities requiring proactive risk communication. Conversely, sectors with lower climate exposure—Education (0.072), Real Estate (0.069), and Health/Social Work (0.067)—clustered at the bottom of the ranking. These results proved the validity of the climate risk disclosure indicator for this paper.

3.2.2. Independent Variable: Executives’ Overseas Experiences

Drawing on the research of Huang et al. [43], this study incorporated the board of directors, the supervisory board, and senior management into the scope of executives. It defined the indicators of executive overseas experiences using three variables: a dummy variable indicating whether the executive team had members with overseas experience (Dum overs), the natural logarithm of the number of executives with overseas experience in the executive team (Sum overs), and the proportion of executives with overseas experience (Rate overs).

3.2.3. Control Variables

Our empirical specification incorporated a comprehensive set of control variables to mitigate potential estimation bias. We systematically accounted for: (1) firm size (Size), (2) leverage (Lev), (3) state-owned enterprise status (SOE), (4) revenue growth rate (Growth), (5) return on total assets (ROA), (6) board size (Board), (7) proportion of independent directors (Indep), (8) CEO–Chair duality (Dual), (9) largest shareholder ownership (Top1), (10) managerial shareholding (Mshare), and (11) firm age (FirmAge). The regression models further absorbed year fixed effects (Year) and industry fixed effects (Industry). Detailed variable definitions and measurement methodologies are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Measurement of variables.

3.3. Model Specification

This study designed the following model (1) to examine the impact of executive overseas experience on corporate climate risk information disclosure:

In the model, the left-hand side represents the climate risk information disclosure level (Disclosureit) of firm i in period t, while the right-hand side includes the executives’ overseas experiences (Overseait) and control variables (Controlsit) in period t. The executives’ overseas experiences (Overseait) specifically comprise three variables: a dummy variable indicating whether there are executives with overseas experience (Dum oversit), the number of executives with overseas experience (Sum oversit), and the proportion of executives with overseas experience (Rate oversit). The regression models further absorbed year fixed effects (Yeart) and industry fixed effects (Industryi). The represents the standard error, which was clustered at the industry level in this study. This study focused on the estimated coefficient . If was significantly greater than 0, it supported the research hypothesis of this study, that is, executive overseas experience will significantly enhance the level of corporate climate risk information disclosure.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics of the main variables. As shown in Table 5, for the variable of corporate climate risk disclosure (Disclosure), the mean, standard deviation, minimum, median, and maximum values were 0.551, 0.355, 0.000, 0.481, and 1.886, respectively. The mean value of the variable indicating whether the firm had executives with overseas experience (Dum overs) was 0.247, suggesting that approximately 25% of the firms in the sample had executives with overseas experience. The descriptive statistics of the other variables were all within a reasonable range and will not be repeated here.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Baseline Results

Table 6 presents the regression results of the impact of executive overseas experience on corporate climate risk disclosure. It can be observed that the coefficients for Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were 0.031, 0.031, and 0.127, respectively, all significant at the 1% level. This indicates that executive overseas experience contributed to enhancing the level of corporate climate risk disclosure, supporting the research hypothesis of this study. In economic terms, taking Column (1) as an example, the coefficient of Dum overs was 0.031, which means that the presence of executives with overseas experience was associated with an average increase of 0.031 in the level of corporate climate risk disclosure. As shown in Table 5, the average value of corporate climate risk disclosure level in the full sample was 0.551. The ratio of the two values was approximately 5.63% (=0.031/0.551), indicating that the impact of executive overseas experience on corporate climate risk disclosure had a certain degree of economic significance.

Table 6.

Baseline results.

4.3. Robustness Checks

4.3.1. IV-2SLS Estimation

To mitigate potential endogeneity bias from omitted variables and reverse causality, we implemented a quasi-experimental design using a plausibly exogenous variation from China’s missionary college legacy. Drawing on Chen & Ma’s [44] archival reconstruction, we constructed a historical instrumental variable: IV MissionaryCollege, a dummy variable indicating whether a prefecture hosted at least one Western-style university established by Christian missionaries before 1920. The rationale was as follows: On the one hand, this variable was historical data from a century ago and did not directly affect corporate climate risk disclosure, thus meeting the exogeneity requirement. On the other hand, in regions where Christian missionaries established universities, the local people were earlier exposed to Western culture, making them more likely to develop overseas and return to serve in local listed companies. Therefore, the IV was closely related to the explanatory variable and was not affected by corporate climate risk information disclosure, making it a suitable instrumental variable.

The first-stage regression results in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 7 show that the coefficient of the IV MissionaryCollege was significantly positive at least at the 5% level, indicating that, in regions where Christian-founded Western-style universities were established, local corporate executives were more likely to have overseas experience, which was in line with theoretical expectations. The second-stage regression results in Columns (4)–(6) of Table 7 show that the coefficients of Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were 1.570, 0.968, and 2.784, respectively, all significantly positive at least at the 10% level. This indicated that, after controlling for potential endogeneity issues using the instrumental variable method, the benchmark regression conclusion that executive overseas experience promotes corporate climate risk information disclosure remained robust.

Table 7.

Robustness checks: IV-2SLS regression.

4.3.2. Tobit Model Test

Given the censored nature of climate risk disclosure data (left-censored at 0, right-censored at theoretical maximum disclosure scores), we employed a Tobit model to address boundary effects and potential attenuation bias in OLS estimates. The test results are presented in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 8. The coefficients for Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were 0.031, 0.030, and 0.126, respectively, all significantly positive at the 1% level. This indicates that, after changing the estimation model, the baseline results remained unchanged.

Table 8.

Robustness checks: Tobit model tests and lagging independent variables.

4.3.3. Lagging Independent Variables by One Period

The impact of overseas executives on corporate climate risk disclosure may have a lagged effect, and the lagged independent variables can mitigate potential reverse causality issues. Based on this, this study lagged independent variables by one period for a robustness test. The test results are shown in Columns (4)–(6) of Table 8. The coefficients for Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were all significantly positive at the 1% level, and the baseline regression results still held.

4.3.4. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

To rigorously address potential selection bias arising from systematic differences in firm characteristics, we implemented a dual-strategy propensity score matching (PSM) framework following the causal identification protocol of Rosenbaum & Rubin [45]. Recognizing the limitations of conventional matching approaches—where pooled matching may induce temporal mismatch and period-by-period matching risks control group instability [46,47]—we adopted a conservative design combining both strategies to enhance robustness. Specifically, all the control variables in Model (1) were used as matching variables, and the nearest-neighbor 1:1 method was employed to match the control group for the treatment group samples. The regression test was then conducted on the matched sample, and the results are shown in Table 9. Columns (1)–(3) present the regression results after nearest-neighbor 1:1 matching under the mixed matching strategy, and it can be found that the coefficients of Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were all significantly positive at the 1% level. Columns (4)–(6) show the regression results after the nearest-neighbor 1:1 matching under the period-by-period matching strategy, with the coefficients of Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs being 0.039, 0.034, and 0.135, respectively, all significantly positive at the 1% level. The above results indicate that, after controlling for sample selection bias, the baseline results in Table 6 still held.

Table 9.

Robustness check: propensity score matching.

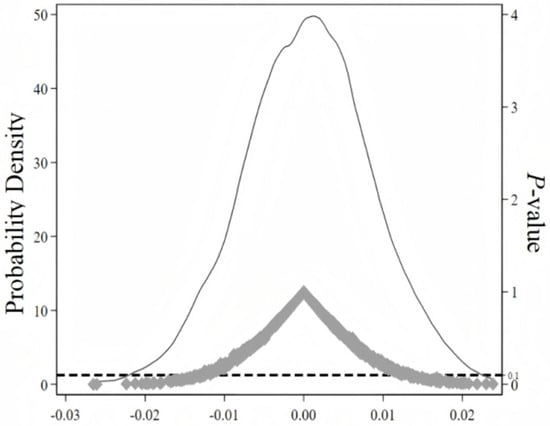

4.3.5. Placebo Test

To rigorously address unobserved confounding factors, we implemented a large-scale placebo falsification test based on counterfactual executive assignment. We generated a synthetic treatment variable False Oversea by randomly reassigning foreign experience indicators across the sample while preserving the original treatment prevalence. This randomization process was iterated 1000 times with stratified resampling to ensure population representativeness. Figure 2 reports the distribution of the regression coefficient values estimated based on False Oversea. It can be seen from Figure 2 that the regression coefficients of False Oversea basically followed a normal distribution centered at zero. Furthermore, according to the scatter plot of the p-values of the 1000 estimated coefficients, the p-values of most False Oversea coefficient estimates were greater than 0.1, and the true estimated value in the baseline regression of this study was in the obvious outlier part. The above results once again indicate that the baseline results in Table 6 were robust.

Figure 2.

Placebo test.

4.4. Further Analyses

4.4.1. Causal Mechanism Identification

We posited that executives with overseas experience enhance corporate climate risk disclosure through dual cognitive channels: (1) Climate Attention Allocation and (2) Managerial Myopia Mitigation. Based on this, this study designed Model (2) to test the two pathways:

This study selected two sets of mediator variables (Mediator): The first set of variables was the firm’s attention allocation to climate-related issues (Attention). It is specifically defined as the proportion of the total number of climate-related words in the management’s discussion and analysis (MD&A). Specifically, drawing on the research of Jung & Song [48] and Lei et al. [49], climate- and environment-related keywords were identified and standardized by the total number of words. The second set of variables was management myopia (Myopia). It was specifically defined as the proportion of the total number of “short-term horizon” words to the total number of words in the MD&A, multiplied by 100 [50,51]. The higher the value was, the higher was the degree of management myopia. The specific measurement methods of mediator variables can be found in Appendix B and Appendix C.

Table 10, Columns (1)–(3), present the mediation test results based on “climate-related attention allocation”. The coefficients for Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were 0.008, 0.005, and 0.018, respectively, all significantly positive at least at the 5% level. This indicated that overseas experience helps enhance executives’ attention allocation to climate-related issues, supporting the pathway “Executive Overseas Experience→(Increase) Management’s Attention to Climate-related Issues→(Promote) Corporate Climate Risk Disclosure”. Columns (4)–(6) of Table 10 report the test results for the “management myopia” mechanism. The coefficients for Dum overs, Sum overs, and Rate overs were significantly negative at least at the 10% level, indicating that overseas experience helps reduce management myopia, thereby improving corporate climate risk information disclosure. This confirmed the theoretical mechanism “Executive Overseas Experience→(Alleviate) Management Myopia→(Promote) Corporate Climate Risk Disclosure”.

Table 10.

Mechanism test results.

4.4.2. Treatment Effect Heterogeneity

- (1)

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Firm Characteristics

William [52] posited that a core principle in understanding the impacts of climate change is to distinguish between controlled and uncontrolled systems. A controlled system is one that can take reasonable measures to ensure the effective and sustainable use of resources, while an uncontrolled system operates largely without human intervention. Most economic activities fall into the category of fully controlled systems. However, agricultural firms, as well as those in coal and non-ferrous metal mining and real estate, belong to partially controlled systems. These are more sensitive to abnormal climate shocks and find it difficult to avoid the impacts of climate change, thus having a higher degree of climate sensitivity. Therefore, for firms with high climate sensitivity, the management may prefer to reduce climate risk information disclosure to avoid the adverse effects of climate information disclosure on stock prices, thus achieving a strategic avoidance of career-related risks. At this point, overseas experience can directly correct the short-sighted behavior of the management, increase climate-adaptive investments in the firm, and enhance the disclosure of climate risk information.

Based on this, this study expected that the positive impact of executive overseas experience on climate risk disclosure was more pronounced for firms with high climate sensitivity. To test this inference, this study constructed a dummy variable Ind for firm climate sensitivity. Ind was set to 1 if the firm belonged to the agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, coal and non-ferrous metal mining, or real estate industries and 0 otherwise. The interaction terms of Oversea and Ind were included in Model (1) for empirical testing. The results are shown in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 11. The coefficients of Ind × Dum overs, Ind × Sum overs, and Ind × Rate overs were 0.100, 0.109, and 0.289, respectively, all significantly positive at the 1% level. This indicated that the positive impact of executive overseas experience on climate risk disclosure was more evident for firms with high climate sensitivity.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity analysis: firm characteristics.

On the other hand, legitimacy theory holds that engaging in behaviors or activities consistent with the social norms and value concepts of the society in which a firm operates is a fundamental prerequisite for the firm’s survival, development, and resource acquisition [53]. Therefore, when climate awareness in a region is high, firms may increase their attention to climate issues and proactively enhance climate risk information disclosure to strategically avoid external pressures, thereby reducing the room for the impact of executive overseas experience on the firm’s attention to climate issues. Conversely, when the climate awareness in a region is low, executive overseas experience can significantly increase the firm’s attention to climate issues, thereby promoting climate risk information disclosure.

Based on this, this study expected that if overseas experience promotes corporate climate risk disclosure by enhancing executives’ attention to climate issues, then the positive impact of executive overseas experience on corporate climate risk disclosure is more pronounced when climate awareness in a region is low. Following the research of Wang et al. [54], the Baidu search index for “climate change” and “climate risk” was used as a proxy indicator for public climate awareness. If this index was above the median of the sample year-industry, the dummy variable Climate was set to 1; otherwise, it was set to 0. Climate and the interaction term Climate × Oversea were added to Model (1) for testing. The results in Columns (4)–(6) of Table 11 show that the coefficients of Climate × Dum overs, Climate × Sum overs, and Climate × Rate overs were significantly negative at least at the 10% level. This indicated that the lower public climate awareness was, the more evident the role of executive overseas experience was in promoting corporate climate risk disclosure, which was in line with the theoretical expectation.

- (2)

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Executive Overseas Experience Characteristics

Global ESG (Environment, Social, and Governance) frameworks exhibit significant institutional divergence, with developed economies pioneering rigorous disclosure regimes that contrast sharply with the growth-oriented priorities of emerging markets. The US established early environmental reporting mandates through SEC Regulation S-K (1934), later expanding to holistic ESG metrics—a regulatory trajectory documented by Coffee [55] as critical for investor protection. Concurrently, the EU institutionalized sustainability governance via its 2014 Non-Financial Reporting Directive, subsequently strengthened by the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation [56], creating a disclosure ecosystem that penalizes non-compliance through capital market sanctions. Therefore, when executives have overseas experience in European countries or the United States, they are more likely to be exposed to cutting-edge climate risk disclosure practices, thereby strengthening the impact of executive overseas experience on corporate climate risk disclosure.

To test the impact of executives’ overseas experience in Europe and the US, this study constructed a dummy variable EA, which was set to 1 if the executive had experience in European countries or the United States and 0 otherwise. EA and the interaction term EA × Oversea were included in Model (1) for testing. The results are shown in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 12. The coefficients of EA × Dum overs, EA × Sum overs, and EA × Rate overs were 0.055, 0.050, and 0.148, respectively, all significantly positive at the 1% and 5% levels. This indicated that executives’ overseas experiences in Europe or the United States was more conducive to enhancing corporate climate risk information disclosure.

Table 12.

Heterogeneity analysis: executive overseas experience characteristics.

Furthermore, different overseas experiences of executives may have different impacts on corporate climate risk disclosure. This part further examined the impact of executives’ overseas study or work experiences. Compared with overseas work experience, individuals with overseas study experience were more likely to accept diverse values and systematically learn professional knowledge and skills from abroad, thereby strengthening the impact of overseas experience [57,58]. In particular, the United States and EU countries are committed to implementing climate change education, which further strengthens the impact of overseas study experience on the climate awareness of returning executives. For example, since 2013, 19 states and the District of Columbia in the United States have adopted the Next Generation Science Standards, requiring teachers to teach the facts of human-caused climate change starting from middle school.

Therefore, this study constructed a dummy variable Education, which was set to 1 if the executive had an overseas educational background and 0 otherwise. Education and the interaction term Education × Oversea were included in Model (1) for testing. The results are shown in Columns (4)–(6) of Table 12. The coefficients of Education × Dum overs, Education × Sum overs, and Education × Rate overs were 0.033, 0.040, and 0.137, respectively, all significantly positive at the 10% level. This indicated that, compared with overseas work experience, executives’ overseas education experiences were more conducive to enhancing corporate climate risk disclosure.

4.4.3. Economic Consequence: Climate Risk Disclosure and ESG Performance

Drawing on information asymmetry theory, firms possess informational advantages over rating agencies in ESG evaluations, as public disclosures serve as the primary data source for external assessments [59,60]. Enhanced climate risk disclosures mitigate information gaps by providing incremental, verifiable data to capital markets, which not only signals managerial commitment to sustainability but also reduces subjective interpretation by rating agencies, thereby compressing ESG rating divergence. To test these dual channels, we estimated the following model (3):

where ESG represents the firm’s ESG performance, measured by the annual average of Huazheng ESG ratings and ESGU represents the firm’s ESG rating divergence. Following the research of Avramov et al. [61], it was calculated based on the ESG ratings of listed companies by Huazheng, Bloomberg, SD Ratings, Menglang, and FTSE Russell to measure the firm-level ESG rating discrepancy. The definitions of the other variables are consistent with Model (1).

The results of Model (3) are shown in Table 13. It can be seen that in Column (1), the coefficient of Disclosure is 0.098, significant at the 1% level, indicating that climate risk disclosure helps to improve the firm’s ESG rating. Column (2) presents the test results of the economic consequences based on ESG rating divergence. The coefficient of Disclosure was significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that while executive overseas experience enhances corporate climate risk disclosure, it provides incremental information to rating agencies, thereby reducing the firm’s ESG rating divergence.

Table 13.

Economic consequence: climate risk disclosure and ESG performance.

5. Discussion

While this study contributes to understanding the role of executives’ overseas experiences in shaping corporate climate risk disclosure, several limitations merit acknowledgment and possible alternative interpretations of the findings also need discussion.

First, the analysis relied exclusively on publicly available ESG, sustainability, and CSR reports, which may not fully capture informal internal discussions or unreported climate risk management practices within firms. Although we employed a rigorous text analysis to identify climate-related terminology, potential greenwashing biases—where firms overstate their climate commitments—could influence the accuracy of disclosure measurements. Future research might triangulate quantitative disclosure indices with qualitative data, such as executive interviews or internal documents, to provide a more comprehensive view of corporate climate strategies.

Second, while our machine learning-based approach effectively processes large textual datasets, it may overlook context-specific nuances in Chinese regulatory language or industry-specific terminology. Additionally, although we addressed endogeneity through instrumental variables and lagged specifications, alternative explanations for the observed associations should be considered. For instance, firms with preexisting commitments to transparency and sustainability may be more inclined to hire executives with overseas experience, potentially driving the positive relationship between overseas experience and climate risk disclosure.

Finally, while our findings supported the hypothesis that executives’ overseas experiences enhance corporate climate risk disclosure through cognitive mechanisms such as increased climate attention and reduced managerial myopia, alternative explanations may also account for the findings, which constitutes another limitation of this study: First, it is possible that the observed relationship was not entirely causal but rather reflected underlying firm characteristics. For example, companies with stronger ESG awareness or international strategic orientation may be more inclined to both adopt advanced disclosure practices and recruit executives with overseas backgrounds. In this case, overseas experience served more as a signal of a firm-level ESG commitment than a direct driver of disclosure behavior. Second, regional institutional environments may confound the relationship. Firms located in more developed, environmentally progressive regions (e.g., first-tier cities) are more likely to face stronger climate regulations and social expectations, which could lead them to both improve climate disclosure and attract globally experienced executives. Thus, local policy contexts may simultaneously influence both variables. Finally, while we identified two primary mechanisms—climate attention allocation and managerial myopia mitigation—it is plausible that additional mechanisms, such as stakeholder pressure responsiveness and reputational signaling, also play a role. Future research should aim to disentangle these intertwined channels through richer datasets (e.g., surveys, interviews) or quasi-experimental approaches to validate whether overseas experience exerts an independent effect on disclosure.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Climate risk disclosure is a critical strategic practice for corporations to respond to global climate governance and low-carbon transition, and executives’ overseas experiences profoundly affect their decision-making direction. This study empirically examines the impact and mechanism of executives’ overseas experiences on corporate climate risk disclosure using a sample of Chinese A-share-listed firms from 2008 to 2022. The study finds that, first, executive overseas experience significantly enhances CCRD, and this effect remains consistent after a series of robustness tests. Second, mechanism analyses show that executives’ overseas experiences promote disclosure through the dual paths of “climate attention allocation enhancement” and “management myopia mitigation”. Third, the heterogeneity analysis shows that, in industries with high climate sensitivity and regions with low public awareness of climate, the promotion of climate disclosure is more pronounced by executives’ overseas experiences; meanwhile, executives with European and American experiences or an overseas education background have more prominent demonstration effects on climate governance. Additionally, an investigation into the economic consequences demonstrates that executives with overseas experience not only improve firms’ ESG performances but also help reduce ESG rating discrepancies, reinforcing the beneficial role of overseas exposure in corporate governance.

6.2. Implications

Based on the above analyses, this paper proposes the following insights:

(1) Government level: Our findings underscore the critical role of policymakers in fostering climate transparency by leveraging the dual mechanisms of attention reconfiguration and myopia mitigation. To enhance climate attention allocation, governments should prioritize talent-centric policies that incentivize the recruitment of executives with international sustainability experience. These individuals bring imprinted cognitive frameworks from advanced climate governance systems, enabling the diffusion of global best practices such as standardized reporting protocols. Simultaneously, regulatory reforms should mandate the disclosure of board-level climate discussions, translating managerial attention into measurable metrics. To counteract short-termism, long-term accountability mechanisms—such as requiring multi-year climate transition plans tied to executive compensation—should be institutionalized. Such policies embed intergenerational equity into governance, leveraging the enduring effects of imprinting to shift organizational priorities from immediate financial returns to sustained climate resilience.

(2) Enterprise level: Firms must strategically integrate overseas-experienced leaders into decision-making structures to operationalize the mediating pathways of attention prioritization and myopia reduction. Executives with international exposure possess technical fluency in global disclosure standards, reducing compliance costs and enabling resource reallocation toward strategic risk mitigation. To institutionalize climate attention, companies should adopt analytical tools to quantify climate-related discourse in internal communications, creating benchmarks for tracking cognitive shifts. Concurrently, governance structures must be redesigned to mitigate managerial short-termism. Linking executive incentives to multi-year climate targets anchors decision-making in long-term value creation, while training programs on scenario analysis foster a forward-looking orientation. By harmonizing talent-driven cognitive shifts with system-level accountability, firms transform climate disclosure from a procedural task into a strategic imperative that aligns with global sustainability trajectories.

(3) Social level: The broader societal ecosystem amplifies climate transparency by reinforcing attention amplification and peer-driven accountability. Media and academic partnerships can develop transparency rankings that highlight leaders and laggards, leveraging public scrutiny to pressure firms into prioritizing climate risks. Industry associations should spearhead sector-specific disclosure norms through collaborative coalitions, fostering competitive imprinting effects where peer benchmarks drive widespread adoption of best practices. Additionally, multi-stakeholder initiatives involving investors and NGOs can institutionalize long-termism by empowering shareholders to vote on climate transition plans. These efforts create a self-reinforcing cycle: external stakeholder pressures reshape internal priorities, while peer-learning platforms reduce the costs and uncertainties associated with disclosure innovation. Collectively, such mechanisms operationalize the theoretical interplay between attention reconfiguration and myopia mitigation, embedding climate accountability into the fabric of organizational and industrial practice.

Author Contributions

Methodology, W.L.; software, W.L.; validation, W.L.; investigation, W.L.; data curation, W.L.; writing—original draft, X.Z., W.L. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., W.L., W.W., A.H. and H.L.; supervision, A.H.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. L2124032); National Social Science Fund Later Funding Project of China (Nos. 18FGL019, 21FGLB017); Jiangsu Province Social Science Fund Major Project (No. BR2024006); and 2024 Jiangsu Provincial Basic Research Program (Social Science Research) (No.22ZDA005). The APC was funded by University of Bath Institutional Open Access Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendix A. Measurement of Climate Risk Disclosure

This study employed a “seed words+Word2Vec semantic expansion” approach to quantify firm-level climate risk disclosure. Following established text analysis protocols in financial research [62], we measured disclosure intensity using the ratio of climate-related terms to total words in corporate ESG/social responsibility/sustainability reports, rather than raw term counts. This normalization controlled for document length heterogeneity while preserving cross-firm comparability.

Appendix A.1. Seed Word Selection

To construct the initial vocabulary set for climate change risk disclosure, this study referred to the initial vocabulary set of firm-level climate risk disclosure identified by Sautner et al. [40] using machine learning keyword algorithms. Then, three authoritative translation tools in the industry, Google Translate, DeepL Translate, and CNKI Translation Assistant, were used to translate and identify each English word, resulting in multiple Chinese translation results for each English word. This study followed the practice of Lin & Wu [63] and Tian et al. [64] to screen the translation results as follows: First, words with obviously inconsistent meanings with climate change were eliminated. Second, words with ambiguous meanings were re-confirmed through a detailed comparison and reading of the text. Third, this study conducted cross-validation of the translation results and invited industry experts to review and provide feedback, further screening and supplementing the results. Ultimately, 48 initial seed words related to firm-level climate change information were formed.

Appendix A.2. Semantic Expansion via Machine Learning

Current methods for similar word set expansion mainly include the dictionary method and the supervised machine-learning method, both of which have notable limitations. The dictionary method struggles to accurately identify the specific context of a text. As a result, the retrieved words often fail to comprehensively and effectively represent the text’s content [62]. Moreover, there is currently no well-defined Chinese dictionary specifically for climate risk, and there are no dedicated phrases for this concept. Creating a new dictionary from the ground up proved to be extremely challenging and is highly susceptible to human subjective judgment errors [65]. On the other hand, the supervised machine-learning method requires labor-intensive and subjective manual coding and word discrimination, which can introduce significant biases in the final word set [66].

To address these issues, we adopted the natural language learning model Word2Vec proposed by Mikolov et al. [41]. This model ingeniously generates multi-dimensional vectors for text vocabulary based on the surrounding context. These vectors form a word vector space, where a smaller cosine distance between vectors indicates a higher semantic correlation. Word2Vec not only overcomes the curse of dimensionality in sparse vector representation but also bridges the context gap in Chinese vocabulary, providing a more accurate reflection of semantic similarity.

Using the Word2Vec online word expansion tool, we expanded the seed word set. The resulting similar words were highly compatible with the context of Chinese financial texts, effectively avoiding the subjectivity of manually defined word lists. We then sorted the expanded words according to their similarity degrees. Eventually, based on the expansion results, we obtained the top 120 most similar words that broadly represent corporate climate risk disclosure. Subsequently, we calculated the total corporate climate risk disclosure indicator (Disclosure) by multiplying the proportion of the total number of climate risk disclosure words in the corporate ESG/social responsibility/sustainability reports by 120. A higher indicator value implies a more comprehensive climate risk disclosure by the firm.

In addition to Word2Vec, considering the semantic recognition limitations of this model, we further employed the more advanced ELMO algorithm based on the LSTM deep neural network for similar word expansion [42]. This allowed us to recalculate alternative indicators of firm climate risk disclosure, facilitating robustness testing.

Appendix A.3. Validation Tests

The deep-learning similar word method used in this study, based on the Wengou financial text database, was rigorously tested for reliability and validity. During the construction of the keyword list, we extensively referenced the existing literature. When compared with the climate change keyword dictionary derived from the machine-learning algorithm in Sautner et al. [40], the coincidence rate exceeded 70%.

Furthermore, we selected 20 enterprises with the highest environmental disclosure scores in the “2019 China Listed Companies ESG Research Report”. Since the environmental disclosure scores within the ESG framework can, to a certain extent, reflect the degree of corporate climate risk disclosure, we matched these enterprises with our research samples. We then sorted the climate risk disclosure indicators of the samples from lowest to highest and divided them into three groups: Group A for low-disclosure firms, Group B for medium-disclosure firms, and Group C for high-disclosure firms.

The results showed that all 20 selected firms were distributed in the medium- and high-disclosure groups (≥Group B), with 13 firms (65%) in the high-disclosure group (Group C). This compelling evidence strongly validated the effectiveness of the climate risk disclosure indicator proposed in this study.

Appendix B. Measurement of Managerial Myopia

On the basis of Brochet et al. [67], through text analysis and machine-learning techniques, we determined the Chinese “short-term horizon” word set and then constructed a managerial myopia index using the dictionary-based method. We validated that this index effectively captured the inherent myopic traits of managers through methods such as actual comparison, internal consistency reliability testing, differential analysis, and economic consequence testing. Through variance decomposition testing, we further ruled out the possibility that the index reflected myopia driven by external pressures.

Appendix B.1. Determining the Seed Word Set

Drawing on the English “short-term horizon” word set in Brochet et al. [67] and the idea of constructing text indicators in Li [68], we read 500 MD&A corpora to understand the characteristics of Chinese text information. We formulated a seed word set related to the “short-term horizon” in Chinese MD&A, which consisted of two major categories: direct and indirect. The direct category included “within days”, “as soon as possible”, “immediately”, and “right away”. The indirect category included “opportunity”, “occasion”, “pressure”, and “test”.

Appendix B.2. Semantic Expansion via Machine Learning

For the same concept or thing, expressers often use multiple semantically similar words for description. Therefore, it was necessary to expand the seed word set with similar words. The Word2Vec machine-learning technology proposed by Mikolov et al. [40] is a milestone achievement in this field in recent years. Essentially, Word2Vec is a neural-network-based Word Embedding method. It represents words as multi-dimensional vectors based on the semantic information of the context and calculates the semantic similarity between words by computing the similarity between vectors. Specifically, this study used the CBOW (Continuous Bag-of-Words Model) in Word2Vec to train the Chinese annual financial report corpus:

Here, C represents the corpus, w represents the center word, and Content(w) represents the context of the center word. The basic idea of the CBOW model is to predict the probability of the current word based on the context. By maximizing the above-mentioned objective function, the Word2Vec word vector corresponding to the center word can be finally obtained. Subsequently, similar words of a word can be obtained by calculating the vector similarity. The model is trained based on a massive amount of financial texts, and the recommended similar words are more suitable for the financial text context, effectively avoiding the subjectivity of artificially defined word lists and the weak correlation of general synonym–antonym tools.

Table A1.

Exemplary Word2Vec semantic similarity outputs: top 10 ranked terms.

Table A1.

Exemplary Word2Vec semantic similarity outputs: top 10 ranked terms.

| Seed Term | Contextual Synonyms | Contextual Similarity Score |

|---|---|---|

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | At the earliest (“尽早”) | 0.861 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | At an early date (“早日”) | 0.771 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Expedite (“抓紧”) | 0.532 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Without delay (“及早”) | 0.517 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Strive for (“力争”) | 0.469 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Full effort (“全力”) | 0.467 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Do one’s best (“尽力”) | 0.457 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Immediately (“立即”) | 0.451 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Endeavor (“争取”) | 0.438 |

| As soon as possible (“尽快”) | Intensify efforts (“加紧”) | 0.438 |

Note: similarity scores derived from Word2Vec embeddings trained on a corpus of 12,000+ Chinese ESG/social responsibility/sustainability reports (2015–2022). The domain-specific training ensures semantic relationships reflect ecological and governance disclosure contexts rather than general business language.

Appendix B.3. Screening the Expanded Word Set and Determining the Managerial Myopia Word Set

We eliminated words in the expanded word set that did not represent the short-term horizon and words that were noisy in the annual reports. Meanwhile, we invited three experts from industry and academia and compared MD&A text samples to verify the indicator word set. The final word set contained 43 “short-term horizon” words.

Table A2.

Managerial myopia measurement: seed terms and domain-expanded vocabulary.

Table A2.

Managerial myopia measurement: seed terms and domain-expanded vocabulary.

| Category | Terms |

|---|---|

| Seed Word Set | Within days (“天内”), within a few months (“数月”), within the year (“年内”), as soon as possible (“尽快”), immediately (“立刻”), right away (“马上”) (directly expressed); opportunity (“契机”), occasion (“之际”), pressure (“压力”), test (“考验”) (indirectly expressed) (a total of 10 words). |

| Expanded Word Set | Within a day (“日内”), within a few days (数天“”), immediately (“随即”), right away (“即刻”), in (“在即”), at the latest (“最晚”), at the latest (“最迟”), at the critical moment (“关头”), coincide with (“恰逢”), before it comes (“未临之际”), the day before yesterday (“前日”), just in time (“适逢”), encounter (“遇上”), just in time (“正逢”), when (“之时”), difficulty (“难度”), dilemma (“困境”), severe test (“严峻考验”), double pressure (“双重压力”), inflation pressure (“通胀压力”), upward pressure (“上涨压力”), should do as soon as possible (“应尽快”), as early as possible (“尽早”), early (“早日”), as soon as possible (“及早”), at the time (“时值”), opportunity (“时机”), when it comes (“到来之际”), financial pressure (“财务压力”), environmental pressure (“环境压力”), many difficulties (“诸多困难”), financing pressure (“融资压力”), repayment pressure (“还款压力”) (a total of 33 words) |

Appendix B.4. Calculating the Managerial Myopia Index

Based on the dictionary-based method, we calculated the proportion of the total word frequency of “short-term horizon” words in the total word frequency of MD&A and then multiplied it by 100 to obtain the managerial myopia index. The larger the value of this index is, the more myopic the manager is.

Appendix C. Measurement of Climate Attention