Abstract

Research on the effects of digital transformation in micro and small enterprises (MSEs) is growing, yet remains underdeveloped, particularly in the context of emerging economies. While previous studies highlight the performance benefits of digital readiness, they often overlook how sector-specific challenges influence these outcomes. This study investigates the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance among MSEs in Bhutan, with a focus on the moderating roles of internal (operational) and external (supply chain) issues. Drawing on data from 217 survey responses collected from firm owners and operators, this study compares tourism and non-tourism sectors to reveal sectoral asymmetries in digital transformation outcomes. The results show that digital readiness is positively associated with firm performance across both sectors. However, the strength of this relationship is differentially moderated by contextual challenges: external issues negatively moderate the digital readiness–performance link in the tourism sector, while internal issues play a similar moderating role in the non-tourism sector. Additionally, firms in the tourism sector report higher levels of both digital performance and satisfaction with digitalization than their non-tourism counterparts. These findings contribute to the Diffusion of Innovation Theory by emphasizing the contingent and asymmetric nature of digital adoption effects across industry sectors. This study offers practical implications for managers and policymakers by underscoring the need for sector-sensitive digital strategies and support mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in digital technologies have transformed how businesses operate, offering opportunities for enhanced efficiency, competitiveness, and value creation [1,2]. Global corporations such as Amazon, Alibaba, and Siemens have successfully leveraged digital transformation to optimize operations, enhance customer experiences, and drive innovation at scale [3,4]. These cases demonstrate that strategic investments in digital infrastructure and data-driven decision-making can lead to sustained competitive advantage [5,6].

Digital transformation offers companies the potential to create efficiency, competitiveness, and new market opportunities. For micro and small enterprises (MSEs), it becomes an important means of securing competitiveness through operational optimization and cost reduction [7]. By leveraging digital technologies, MSEs can maximize efficiency across various operational areas such as online marketing, customer data analytics, and real-time communication [8]. Moreover, even with limited resources, MSEs can access global markets and reach new customer bases through digital platforms [9]. Digital transformation also plays a significant role in enabling the development of innovative products and services, enhancing the value of businesses, and improving customer experiences [7]. Thus, digital transformation is an essential element for small enterprises to secure competitiveness, adapt to rapidly changing markets, and achieve sustainable growth [10,11].

Existing studies primarily focus on the impact of digital transformation on firm performance and economic growth, with many research efforts centered around large enterprises. These studies often explain how digital technologies enhance the efficiency and competitiveness of large firms [12,13]. In particular, studies focusing on developed countries predominantly explore the effects of digitalization on GDP growth and industrial innovation, with a large number of case studies based on advanced digital infrastructure and resources [14,15]. However, research on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) remains relatively limited, particularly regarding the impact of digital transformation on firm performance in developing countries [16,17]. In recent years, there has been an increasing body of research on the adoption of digital technologies by SMEs in developing countries, emphasizing improvements in productivity, cost reduction, and customer service [8,16]. However, studies that address the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance or consider industry-specific differences are still lacking.

Many MSEs in developing countries are still in the early stages of digital transformation and are unable to fully utilize digital technologies due to lack of access to infrastructure and resources. For instance, in developing regions such as the APEC area, MSEs face challenges related to insufficient technical capabilities and limited resources in adopting digital tools, which hampers improvements in business performance [8,17,18]. Studies on digital transformation in developing countries, such as Bhutan, are relatively scarce, and there is a lack of in-depth analysis on industry-specific digital readiness and the social impacts of digital transformation.

Bhutan, while undergoing digital transformation, has MSEs that are still lacking digital readiness, making it difficult for them to compete in the global market. As a country with distinct digital infrastructure and resource constraints, Bhutan provides an ideal case for analyzing the impact of digital transformation on the productivity and economic competitiveness of MSEs. The tourism industry in Bhutan, through its connection to global markets, further emphasizes the importance of digital transformation and provides a favorable environment for studying the relationship between digital readiness and business performance. In this context, this study selects Bhutan as the subject for examining the adoption of digital technologies (digital readiness) and its impact on business performance.

This study is grounded in Rogers’ [19] Diffusion of Innovation Theory, which focuses on the process through which digital innovations spread within society, analyzing the contextual challenges—especially the internal (operational constraints) and external (supply chain disruptions) issues that influence the relationship between digital readiness and business performance. Additionally, the study applies Resource Dependence Theory and Dynamic Capabilities Theory to explain how firms manage external resources and utilize internal capabilities to adopt digital technologies and ensure successful digital transformation, while also responding to rapidly changing markets. The research specifically examines how internal and external challenges that affect the relationship between digital readiness and business performance vary between the tourism and non-tourism sectors.

Furthermore, this study provides empirical evidence on how digital transformation contributes to enhancing a firm’s competitiveness. Through examining the effects of digital readiness and both external and internal issues on firm performance, the study offers strategic insights for managers and policymakers on the successful implementation of digital technology adoption. It also emphasizes the importance of tailored policies and support measures that account for sector-specific differences in digital readiness, providing practical approaches for MSEs in developing countries to effectively drive digital transformation.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and develops hypotheses, Section 3 describes the methodology, Section 4 presents the results, Section 5 discusses the research findings and contributions, and Section 6 outlines the limitations of the study and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Each construct, theory, and factor supporting the foundation of the paper is addressed in a separate sub-section.

2.1. Value Creation Through Digitalization: Cases from Small and Developing Economies

Digitalization plays a crucial role in enhancing business performance and competitiveness. Particularly in micro and small enterprises (MSEs), digitalization has become an essential element for value creation in small economies. Afuah [6] defines value creation as the improvement of both financial and non-financial performance of firms, typically measured through key performance indicators (KPIs). Zott and Amit [20,21] further argue that value creation occurs through the introduction of new products or services, the development of alternative marketing and distribution channels, and increased efficiency that reduces costs while enhancing value for customers and partners. Moreover, maintaining strong relationships with suppliers and customers is also essential, as it facilitates value creation through complementarities across products, services, and channels.

The integration of digital technologies into core business processes is increasingly critical for effective value creation. Husted and Allen [22] emphasize the importance of collaborative engagement among stakeholders, especially in resource-constrained environments. In particular, MSEs in developing economies, which face infrastructural, financial, and human resource constraints, can leverage digital tools such as big data analytics, the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence (AI) to better align operations with evolving consumer needs and market trends.

Dynamic Capabilities Theory explains that digitalization strengthens a firm’s dynamic capabilities, enabling it to adapt to market changes. Teece [3] asserts that digital readiness enhances a firm’s technical and operational capabilities, allowing it to respond rapidly to changing market conditions. In this context, the process of strengthening dynamic capabilities through digital readiness plays a critical role in enabling MSEs to adapt more effectively to market changes and pursue innovation.

In developing economies like Bhutan, the potential for digitalization is significant, particularly in sectors such as tourism, agriculture, and handicrafts [23,24]. However, challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and technological limitations hinder full adoption. Dynamic Capabilities Theory suggests that digital readiness enhances MSEs’ internal capabilities, enabling them to maintain competitiveness and adapt to market conditions. In Bhutan, digitalization strengthens dynamic capabilities, playing a critical role in improving competitiveness and market access.

Additionally, social media and digital platforms provide MSEs with low-cost channels for customer engagement, market intelligence, and participation in broader innovation ecosystems. Biggemann et al. [25] highlight the strategic role of marketing and resource management in value creation in competitive environments. This is especially important for MSEs facing increasing globalization and competitive pressure from larger firms [26]. Through digitalization, the ability to leverage internal and networked resources provides firms with an advantage, enabling them to capture emerging opportunities and respond to external threats [3].

While opportunities for digitalization remain significant in developing economies like Bhutan, adoption is constrained by regional, industrial, and technological limitations. However, digitalization remains key to enabling firms to enhance competitiveness, improve market accessibility, and secure sustainability [23,24]. Studies on digitalization in Bhutan emphasize the importance of integrating digital technologies into the region’s economic context and highlight the significance of digital innovation for connecting with the global economy [17,18].

2.2. Digital Readiness: An Analysis Through the Diffusion of Innovation Theory

Digital readiness refers to a firm’s ability to effectively adopt, implement, and benefit from digital technologies in response to changing environmental and market conditions. While the early concept of technological readiness focused primarily on hardware capacity, automation potential, and linear process upgrades [27], digital readiness requires dynamic capabilities such as data utilization, platform integration, agility, and digital leadership, which are essential for competing in rapidly evolving digital ecosystems [1].

According to the Diffusion of Innovation Theory [19], the adoption of new technologies varies according to the adopter categories, including innovators, early adopters, and laggards, with each group demonstrating different characteristics and attitudes. This theory provides a useful framework for understanding how digital technologies are adopted and spread within organizations and industries. In the digital age, however, the timing of adoption is no longer the only important factor; the ability to effectively integrate and scale these technologies within the organization is of paramount importance. Firms with high digital readiness not only adopt technology but also leverage it effectively to create business value.

Digital technologies, due to their modularity, scalability, and network effects, require firms to build new competencies that extend beyond mere technological adoption. Specifically, for micro and small enterprises (MSEs), capabilities such as real-time data processing, customer interaction via digital platforms, and the ability to reconfigure operations in response to rapidly changing market demands are critical. Firms with higher digital readiness are more likely to use existing resources to drive innovation and create value [2]. Digital readiness is a technical and strategic condition for competitiveness, particularly in resource-constrained environments such as Bhutan.

Digital readiness varies significantly across industries, particularly between tourism-related MSEs and non-tourism-related MSEs. These differences are rooted in factors such as operational models, market orientation, and customer engagement requirements. Tourism-related MSEs are inherently outward-facing and internationally connected, serving foreign customers and managing a wide array of digital interactions, including online reservation systems, digital payment systems, and real-time communication with global suppliers and service aggregators [23,28,29]. These firms operate under Bhutan’s “high-value, low-impact” tourism policy, which demands high service quality, international standards, and seamless coordination across logistics, accommodations, dining, and transportation. Consequently, digital tools are not merely optional but essential to maintaining competitiveness and operational functionality.

In contrast, non-tourism MSEs tend to be domestically focused, with localized operations, familiar customer bases, and relatively simple transactions. As a result, many of these firms rely on basic technologies, such as text messaging or informal digital channels, with less need for integrated systems or real-time data exchange [30,31]. Existing studies emphasize that digital adoption in such firms is constrained by low perceived utility, lack of technical skills, and infrastructure gaps [30,31].

2.3. Supply Chain and Operational Issues Related to Digitalization: Contingency Theory

The adoption and implementation of digital technologies in micro and small enterprises (MSEs) are influenced by both internal and external environments. Digital readiness serves as a crucial variable for translating into firm performance, and the challenges encountered in this process significantly affect how firms adopt and utilize digital technologies. Contingency Theory [32] explains how external environments and internal operational capabilities impact an organization’s strategic decisions and structure. According to this theory, organizations must appropriately respond to changing environments, and the success of digitalization depends on the interaction between environmental factors and internal capabilities.

Internal issues (operational issues) and external issues (supply chain issues) play a vital role in the process through which digital readiness translates into firm performance. Internal issues refer to the resources and capabilities required to effectively adopt and implement digital technologies within an organization. In particular, small firms often face challenges in adopting and realizing digital technologies due to limited resources and human capital. Studies by Omrani et al. [33], Shahadat et al. [34], and Zhang, Xu and Ma [11] suggest that if there is a lack of systems, managerial expertise, and digital capabilities within the firm, the success of digitalization may be limited. Contingency Theory [32] argues that such internal capability deficits act as moderators in the relationship between digital readiness and performance. In other words, internal structural weaknesses or resource constraints may prevent effective digital implementation and hinder performance outcomes.

External issues pertain to challenges arising from supply chain relationships and interactions with partners. MSEs often face challenges related to digital system integration with external suppliers or regulatory constraints. According to research by Ben Slimane et al. [35] and Vial [2], issues such as lack of system compatibility with external suppliers and supply chain digital integration problems can impact the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. Contingency Theory suggests that if the external environment does not align with the firm’s digital strategy, the positive effects of high digital readiness may not translate into performance improvements. In particular, in smaller markets like Bhutan, external supply chain issues and infrastructure limitations may inhibit digital technology adoption. These external challenges play a critical role in enabling firms to successfully execute digital strategies, making them essential factors for the success of digitalization.

Ultimately, Contingency Theory explains how the conditions for digital readiness to translate into firm performance are moderated by both external and internal factors. Firms must adjust their digital strategies not only based on their internal capabilities but also by considering the external environment, particularly the supply chain and partnerships. Through this process, digital technologies can maximize their effectiveness. Donaldson [32] argues that each organization must choose and implement the digital strategy that best fits its needs to adapt to the changing market environment. Therefore, digital readiness significantly influences the success of digital transformation strategies based on both external environmental factors and internal resources and capabilities.

2.4. Satisfaction: Service-Dominant Logic

Customer satisfaction is closely linked to firm performance, with a substantial body of literature suggesting that improvements in organizational performance often lead to enhanced customer experiences. From both marketing and operations perspectives, superior firm performance is reflected in efficiency, innovation, service quality, and responsiveness, all of which can significantly enhance customer value perception, thereby driving higher satisfaction levels [36,37,38]. When firms streamline processes, reduce service errors, and deliver products or experiences that meet or exceed customer expectations, customers are more likely to respond positively and maintain loyalty.

Service-Dominant Logic [39] posits that the value of service provision is co-created through interactions with customers. This concept is particularly useful for explaining the effects of digitalization in terms of customer experience. In service-oriented industries like tourism, the relationship between firm performance and customer satisfaction is even more pronounced. Tourism-related firms emphasize intangible value propositions such as hotel service quality, personalized services, and reliability. Research indicates that the financial and operational performance of tourism businesses—such as timely service delivery, digital responsiveness, and seamless customer interaction—are closely linked to satisfaction and revisit intentions [40,41]. The adoption of digital tools serves as a performance-enhancing factor by enabling real-time service delivery, transparency, and empowering customers [42,43].

In non-tourism sectors like retail and agriculture, firm performance indicators also play a crucial role in determining customer satisfaction. Product quality, order fulfillment accuracy, and post-sale service are key factors that influence customer satisfaction [44,45]. While customer expectations may differ across industries, the underlying principle remains consistent: firms that perform better operationally and strategically are more capable of delivering superior customer value.

In small economies like Bhutan, customer satisfaction can vary depending on the differences in digital readiness and firm performance. Firms in the tourism industry, exposed to international markets and highly dependent on digital systems for customer interactions, may feel greater pressure to translate performance into tangible customer value. In contrast, non-tourism MSEs operate in more informal, feedback-driven environments, where the relationship between performance and satisfaction may be weakened unless actively managed through service innovation or localized engagement strategies. Therefore, understanding the influence of firm performance on customer satisfaction is crucial for evaluating the outcomes of digital transformation [46]. This not only provides a measurable endpoint for value creation but also emphasizes the importance of aligning operational and strategic performance improvements with customer-centric objectives.

2.5. Hypotheses

Digital readiness refers to a firm’s ability to effectively adopt digital technologies and generate performance outcomes, acting as a critical determinant of firm success regardless of industry or national context. Digital tools enable process automation, enhanced customer engagement, efficient resource allocation, and data-driven decision-making, which are essential for firms to adapt to changing market demands [1,47]. Firms with high digital readiness are better equipped to rapidly adapt to external environments and secure sustained competitive advantage. According to Dynamic Capabilities Theory [3], firms that sense digital opportunities and integrate them into their internal processes are more likely to experience performance improvements. Additionally, Diffusion of Innovation Theory [19] explains that firm performance varies depending on the speed of technology adoption and the characteristics of adopters, emphasizing that technology adoption is not limited to the timing of adoption but also depends on how well the technology is integrated and scaled. Firms with high digital readiness can quickly adapt to market changes and strengthen their competitive position, particularly innovators and early adopters who leverage digital readiness to gain a favorable competitive edge.

Digital readiness can vary across industries. In the tourism sector, where firms target international customers, digital readiness plays a crucial role in global marketing, reservation systems, and customer communication [28,48]. Its integration with global platforms is essential, and digital tools enable firms to maintain competitiveness and improve market accessibility. In contrast, non-tourism industries primarily target local markets, and digital readiness is important for improving operational efficiency, such as inventory management, supply chain optimization, and customer communication [49]. Despite these differences, digital readiness positively influences firm performance in both sectors.

H1a.

In the tourism industry, digital readiness is positively associated with firm performance.

H1b.

In the non-tourism industry, digital readiness is positively associated with firm performance.

In developing countries, tourism-related MSEs operate within a highly interconnected external-dependent ecosystem. They must coordinate real-time interactions with booking sites, international clients, and cross-border logistics providers, with essential reliance on integration with global platforms. In such environments, external issues can pose significant obstacles to maximizing a firm’s digital readiness. For example, problems such as supplier technology mismatches, unstable internet infrastructure, and lack of integration with global platforms can have a profound impact on service continuity and value delivery. For tourism industry MSEs, even with high digital readiness, if external environmental constraints are present, the expected performance improvements may not be realized or may be limited [28,48].

According to Contingency Theory, even if a firm strengthens its internal capabilities through digital readiness, performance improvements may still be limited if external environmental conditions are unfavorable. Specifically, in the tourism industry, while firms can efficiently perform tasks such as booking management, customer communication, and global marketing through the adoption of digital technologies, external environmental issues—particularly supply chain challenges—can hinder their performance. For instance, if internet infrastructure is unstable or if system integration with suppliers is not smooth, improvements in efficiency or customer service using digital technologies may be difficult to achieve. Therefore, even with high digital readiness, if the external environment is unfavorable, the anticipated performance improvements may not materialize or may be constrained, with external (supply chain) issues weakening the positive effects of digital readiness on firm performance [39].

H2a.

In the tourism industry, external (supply chain) issues negatively moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance, such that the positive effect of digital readiness on performance decreases when external issues are high.

Non-tourism MSEs typically operate within localized supply chains, with relatively fewer customer interactions and lower utilization of digital technologies. These firms are less dependent on external supply chain issues, which means that as digital readiness increases, the likelihood of performance improvement also increases in a more linear manner. In other words, because they are less affected by external factors such as supply chain issues, higher digital readiness naturally leads to improved firm performance.

This explanation is further clarified through Contingency Theory. According to this theory, a firm’s performance depends on the degree of dependence on the external environment. Firms like non-tourism MSEs, which have low dependence on external factors, are less influenced by external issues affecting performance. Therefore, in non-tourism industries, higher digital readiness leads to more clear and direct improvements in firm performance. In other words, external supply chain issues do not disrupt the relationship between digital readiness and performance, and higher digital readiness directly impacts performance enhancement.

H2b.

In the non-tourism industry, external (supply chain) issues do not significantly moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance.

Small tourism enterprises (MSEs) actively adopt digital tools for customer interaction (e.g., reservation systems, communication apps). These tools require relatively simple infrastructure and have low demands on internal operations. When firms in the tourism industry leverage digital readiness to quickly adapt to the external environment and maintain competitiveness in the global market, internal operational issues (e.g., resource shortages, technological gaps) may not have a significant impact. This can be explained by Dynamic Capabilities Theory. According to this theory, firms can rapidly adapt to external changes and restructure internal resources and operational processes to enhance performance through the use of digital technologies [3]. In the tourism sector, when digital readiness is high, internal issues play a relatively less important role in responding to changes in the external environment. Furthermore, firms can compensate for internal shortcomings through outsourcing or partnerships, meaning that the higher the digital readiness, the fewer the limitations on performance improvement.

H3a.

In the tourism industry, internal (operational) issues do not significantly moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance.

Non-tourism MSEs (such as retail, agriculture, and small-scale manufacturing) generally operate within localized supply chains and primarily target domestic markets. These firms typically have limited customer interaction and lower utilization of digital technologies. In the non-tourism sector, higher digital readiness leads to greater reliance on internal operations (e.g., production, inventory management, customer communication), making the lack of internal capabilities a significant factor affecting firm performance. If firms lack internal resources or have low digital literacy, they may not be able to effectively utilize digital technologies, hindering performance improvements [34,50].

In this context, the Resource-Based View (RBV) is useful. RBV suggests that the resources and capabilities a firm possesses are key determinants of competitive advantage [5]. In non-tourism MSEs, if internal resources are insufficient or not utilized efficiently, even high digital readiness may be insufficient to drive performance improvement. For example, low digital literacy, technical limitations, and inefficiencies in resource allocation can hinder the effective use of digital readiness, limiting performance enhancement. These internal issues can become significant barriers for non-tourism MSEs in their efforts to grow and innovate [33,34].

H3b.

In the non-tourism industry, internal (operational) issues negatively moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance, such that the positive effect of digital readiness on performance decreases when internal issues are high.

Digital readiness is closely linked to firm performance, with successful firms positioned advantageously to consistently deliver high-quality value to their customers [47]. In particular, firms with high digital readiness can improve interactions with customers, provide personalized services, and, through this, enhance customer satisfaction, ultimately driving firm performance [1].

According to Service-Dominant Logic (SDL), customer satisfaction is determined by the value co-created through interactions between the customer and the firm [39]. In particular, in the tourism industry, offering personalized services and utilizing digital tools to improve reservation management, global marketing, and other operations is essential. Firms with high digital readiness can provide efficient services that align with rapidly changing market demands, which is a key factor in enhancing customer satisfaction [48]. As customer satisfaction increases, customer loyalty improves, which leads to better firm performance. For example, digital reservation systems, real-time communication, and personalized services exceed customer expectations, leading to higher satisfaction and increased intentions to revisit. This ultimately enhances the performance of tourism enterprises [51].

In non-tourism sectors, higher digital readiness improves operational efficiency and customer communication, naturally leading to increased customer satisfaction. The Resource-Based View (RBV) suggests that firms can create a competitive advantage by efficiently utilizing internal resources [5]. When digital resources—such as IT infrastructure, data utilization, and digital literacy—are leveraged to improve customer service, customer trust and satisfaction increase. Non-tourism MSEs can enhance customer satisfaction by meeting customer needs and improving product consistency, delivery times, and after-sales services through digital tools [30]. In particular, when digital readiness is high, customers experience products or services more efficiently, which leads to positive outcomes. Firms with high digital readiness can increase customer satisfaction, and as a result, their performance improves [34].

Therefore, the higher the digital readiness, the better firms perform in interactions with customers, leading to increased customer satisfaction and, ultimately, enhanced firm performance.

H4a.

In the tourism industry, firm performance is positively associated with customer satisfaction.

H4b.

In the non-tourism industry, firm performance is positively associated with customer satisfaction.

2.6. Research Framework

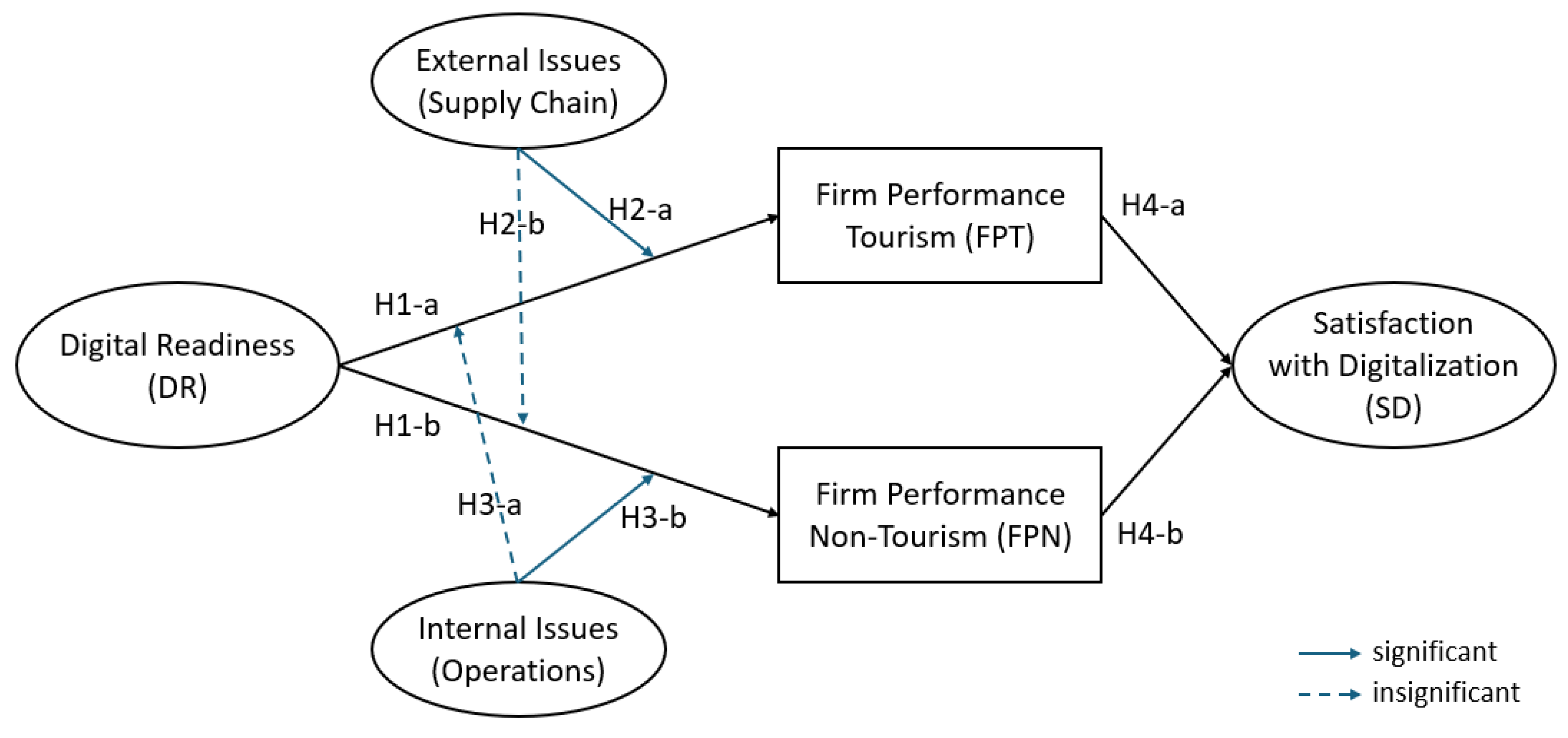

To guide the empirical investigation and provide a structured overview of the hypothesized relationships, a conceptual research framework is presented in Figure 1. This framework is grounded in the Diffusion of Innovation Theory [19] and resource-based perspectives [5], and it highlights the role of digital readiness as a central predictor of firm performance and customer satisfaction across both tourism and non-tourism MSE sectors.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Crucially, the model incorporates external supply chain issues and internal operational issues [11,33] as moderating variables that may influence the strength of the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. The framework places particular emphasis on examining the asymmetric moderating effects of these contextual barriers across sectors [35]. Specifically, it seeks to explore whether external issues play a more pronounced moderating role in the tourism sector—where firms are outward-facing and network-dependent—while internal issues have a stronger moderating impact in the non-tourism sector, where performance is more internally driven.

This structured framework supports a comparative understanding of how digital transformation impacts firm outcomes differently depending on both organizational readiness and sector-specific contextual constraints.

3. Methodology

To test the hypotheses, a series of statistical analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between Digital Readiness (DR) and Firm Performance in the tourism sector (FPT) and the non-tourism sector (FPN). Additionally, a comparative analysis was performed to assess the differences in value creation and customer satisfaction between the two sectors. Moderation analysis was used to test the effects of internal operational issues and external supply chain issues on the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. For the purposes of this study, firms with more than 20 employees were classified as medium-sized and were excluded from the analysis, focusing the study exclusively on micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in Bhutan.

3.1. Data Collection

Data were collected through an online survey disseminated via a QR code posted on the popular and accessible Chinese social media platform WeChat. The survey was hosted on the Wen Juan Xing platform, which was also used to collect the data. Due to the nature of social media-based distribution, a snowball sampling effect may have occurred, leading to a concentration of the sample within specific networks or groups [52]. This characteristic may impose limitations on the representativeness of the sample, potentially affecting the generalizability of the study’s findings. To ensure data quality, the IP addresses of respondents were tracked to prevent duplicate submissions from the same user. A total of 223 responses were received, and after screening for completeness and validity, 6 responses were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 217 valid responses.

3.2. Survey Instrument

The survey instrument used in this study was adapted from previously validated questionnaires in related research domains. The construct for Digital Readiness (DR) and the firm performance measures for both the tourism (FPT) and non-tourism (FPN) sectors were based on key performance indicators (KPIs) drawn from the work of Khan et al. [53], Ho et al. [54], Bressolles and Lang [49], Okudan et al. [55]. Internal operational issues were measured using items adapted from Saryamto and Saryatmo and Sukhotu [56], Haddud and Khare [10], and Creazza et al. [57]. External supply chain issues were measured using scales developed by Choi et al. [58], Queiroz, Pereira, Telles and Machado [4], and Luthra and Mangla [59]. Items for customer satisfaction with digitalization efforts were drawn from Alazab, Alhyari, Awajan, and Abdallah [14], Pai et al. [60], Sanusi and Roostika [61], Chen, Miraz, Gazi, Rahaman, Habib, and Hossain [51], and Fettermann, Cavalcante, Almeida, and Tortorella [47].

3.3. Sampling

Demographic details of the final sample are summarized in Table 1. The sample consisted of 217 micro and small enterprises (MSEs). Firm age was distributed as follows: less than 2 years (63 firms), 2–5 years (63 firms), 6–10 years (60 firms), and more than 10 years (31 firms). This indicated a relatively young firm population. Firm size was split between micro enterprises (1–9 employees, n = 111) and small enterprises (10–20 employees, n = 106). No medium-sized firms (21+ employees) were included in the sample. Sector distribution included 90 tourism-related firms (41.5%) and 127 non-tourism firms (58.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of the multi-item scales used in the survey. Following Pallant [62], a Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.7 is acceptable, while values above 0.8 are considered preferable. As shown in Table 2, all constructs demonstrated excellent reliability, with alpha values exceeding 0.9, indicating strong internal consistency and justifying further statistical analysis.

Table 2.

Cronbach test results.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the core constructs used in this study. The mean score for Digital Readiness (DR) was 4.31 (SD = 1.93), indicating that firms generally perceive themselves as moderately digitally prepared. Operations and supply chain challenges had mean values of 4.17 (SD = 2.33) and 1.96 (SD = 1.47), respectively, suggesting greater perceived difficulty in managing internal operational issues than external supply chain constraints. The average score for Firm Performance (FP) was 3.43 (SD = 2.06), while Satisfaction with Digitalization (SD) averaged 3.52 (SD = 2.06), reflecting a moderately positive perception of digital outcomes among the sampled firms.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of core study variables.

4. Results

4.1. The Direct Effect of Digital Readiness on Firm Performance Across Industries

A simple linear regression was conducted to examine the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. For the tourism sector, the results indicated that digital readiness has a significant positive effect on firm performance, F(1, 88) = 6.23, p = 0.014. The model explained 6.6% of the variance in firm performance. The coefficient of digital readiness was 0.43, suggesting that a one-unit increase in digital readiness is associated with a 0.43-unit increase in firm performance. Therefore, Hypothesis H1a was supported (Table 4).

Table 4.

The effect of digital readiness on firm performance in the tourism industry.

For the non-tourism sector, the results also showed a significant positive effect, F(1, 125) = 25.68, p < 0.001, with the model explaining 17% of the variance in firm performance. The coefficient of digital readiness was 0.34, indicating that a one-unit increase in digital readiness corresponds to a 0.34-unit increase in firm performance. Therefore, Hypothesis H1b was supported (Table 5).

Table 5.

The effect of digital readiness on firm performance in the non-tourism industry.

4.2. (Non-)Tourism Industry—External (Supply Chain) Issues

A moderation analysis is conducted in Table 6 to examine the moderating effect of external issues (EX) on the relationship between digital readiness (DR) and firm performance (FP).

Table 6.

The moderating effect of external issues (supply chain) on the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance in the tourism industry.

In the tourism industry, the overall model was statistically significant, F(3, 86) = 237.60, p < 0.001, explaining 89.23% of the variance in firm performance. The interaction between external issues and digital readiness was significant (B = −0.69, p < 0.001), suggesting that external issues significantly moderated the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. This implies that as external issues increase, the positive effect of digital readiness on firm performance is weakened. Therefore, Hypothesis H2a was empirically supported.

In the non-tourism industry, the overall model was statistically significant, F(3, 123) = 10.31, p < 0.001, explaining 20.09% of the variance in firm performance (Table 7). However, the interaction term between digital readiness and external issues was not statistically significant (B = −0.40, p = 0.250), indicating that external issues did not significantly moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. Therefore, Hypothesis H2b was supported.

Table 7.

The moderating effect of external issues on the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance in the non-tourism industry.

4.3. (Non-)Tourism Industry—Internal (Operational) Issues

A moderation analysis was conducted to investigate the moderating effect of internal issues (IN) on the relationship between digital readiness (DR) and firm performance (FP) in the tourism industry. The overall model was not statistically significant, F(3, 86) = 2.15, p = 0.0997, explaining only 6.98% of the variance in firm performance. More importantly, the interaction term between digital readiness and internal issues was also not statistically significant (B = −0.29, p = 0.746), indicating that internal issues do not significantly moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance. Therefore, Hypothesis H3a was supported (Table 8).

Table 8.

The moderating effect of internal issues on the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance in tourism industry.

A moderation analysis was conducted to examine the moderating effect of internal (operational) issues (IN) on the relationship between digital readiness (DR) and firm performance (FP) in the non-tourism industry. The overall model was statistically significant, F(3, 123) = 197.47, p < 0.001, explaining 82.81% of the variance in firm performance. Importantly, the interaction term between digital readiness and internal issues was statistically significant and negative (B = −0.35, p = 0.002), indicating that internal issues significantly and negatively moderated the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance.

This result suggests that as internal issues increase—such as lack of skilled labor, inefficient processes, or limited internal digital capacity—the positive effect of digital readiness on firm performance diminishes. Therefore, Hypothesis H3b was supported (Table 9).

Table 9.

The moderating effect of internal issues on the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance in the non-tourism industry.

4.4. The Impact of Firm Performance on Customer Satisfaction Across Industries

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between firm performance and satisfaction with digitalization in the tourism industry. The results revealed a statistically significant and positive association, F(1, 88) = 290.96, p < 0.001, with the model explaining 76.8% of the variance in satisfaction with digitalization. The unstandardized coefficient for firm performance was 0.64, indicating that a one-unit increase in firm performance is associated with a 0.64-unit increase in satisfaction with digitalization. The standardized beta coefficient (β = 0.88) further suggests a strong positive effect.

This finding aligns with Service-Dominant Logic (SDL), which posits that value is co-created through interactions between customers and firms, and that digitalization can enhance customer experience and satisfaction. Specifically, in the tourism industry, the strong positive relationship between firm performance and satisfaction with digitalization can be viewed as empirical support for SDL theory. Therefore, Hypothesis H4a is supported (Table 10).

Table 10.

The effect of firm performance on satisfaction with digitalization in the tourism industry.

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between firm performance and satisfaction with digitalization in the non-tourism industry. The results revealed a strong and statistically significant positive relationship, F(1, 125) = 531.49, p < 0.001, with the model explaining 81% of the variance in satisfaction with digitalization. The unstandardized coefficient for firm performance was 0.85, indicating that a one-unit increase in firm performance is associated with a 0.85-unit increase in satisfaction with digitalization. The standardized beta coefficient (β = 0.90) demonstrates a very strong effect size.

This finding supports the predictions made through the Resource-Based View (RBV). RBV posits that internal resources—such as IT infrastructure, data utilization capabilities, and digital literacy—play a critical role in generating competitive advantage and improving firm performance [5]. In the non-tourism sector, firms with higher digital readiness are able to leverage these internal resources effectively, resulting in improved performance and, consequently, greater satisfaction with digitalization. Firms with high digital readiness can enhance operational efficiency and customer service, leading to better overall performance and increased customer satisfaction, which aligns with the expectations of RBV.

Therefore, Hypothesis H4b was empirically supported, confirming that firms with higher digital readiness positively impact both performance improvement and increased customer satisfaction, as predicted by RBV (Table 11).

Table 11.

The effect of firm performance on satisfaction with digitalization in the non-tourism industry.

5. Robustness Check

5.1. Multi-Group SEM Analysis Across Industry Contexts1

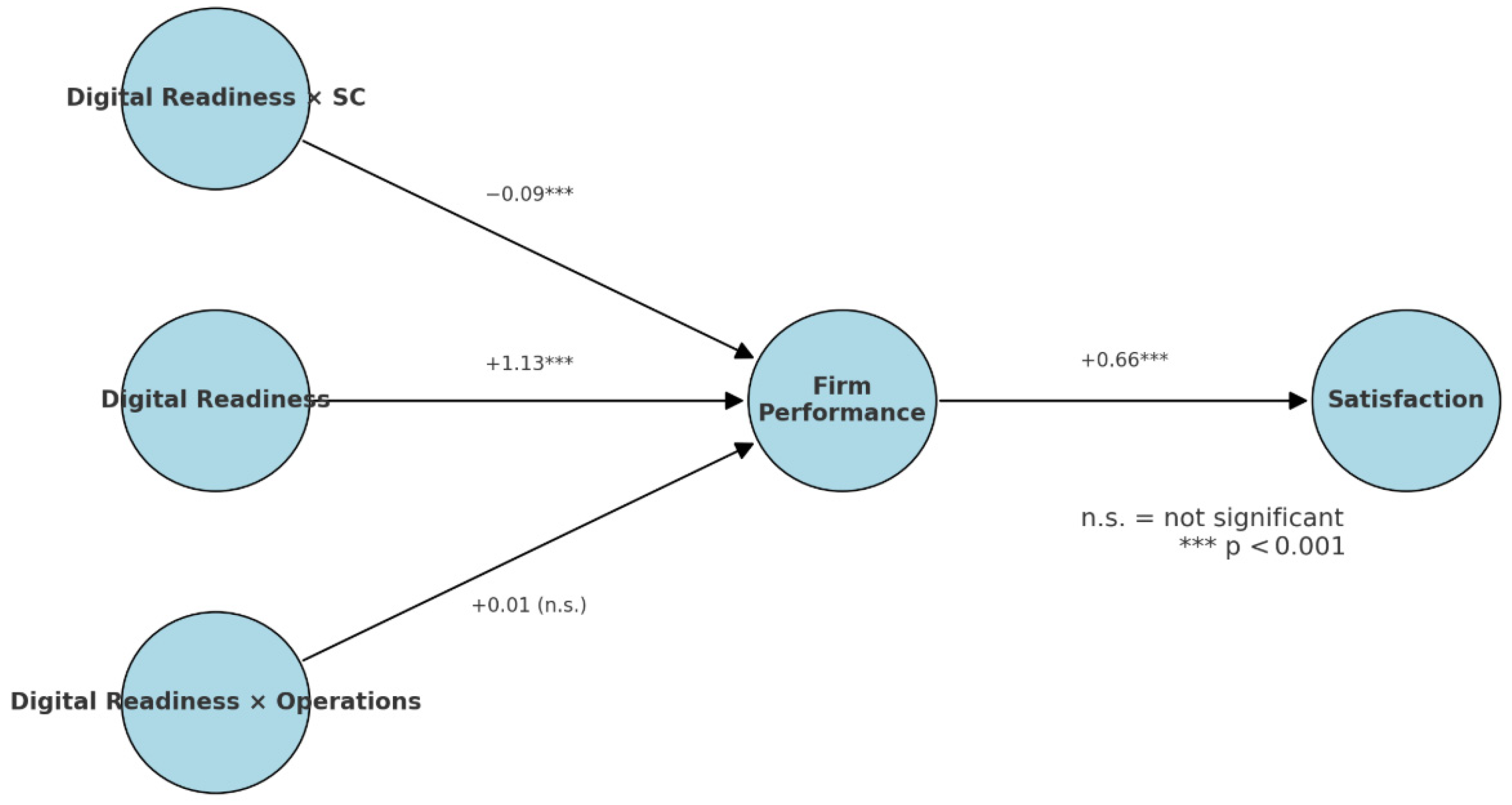

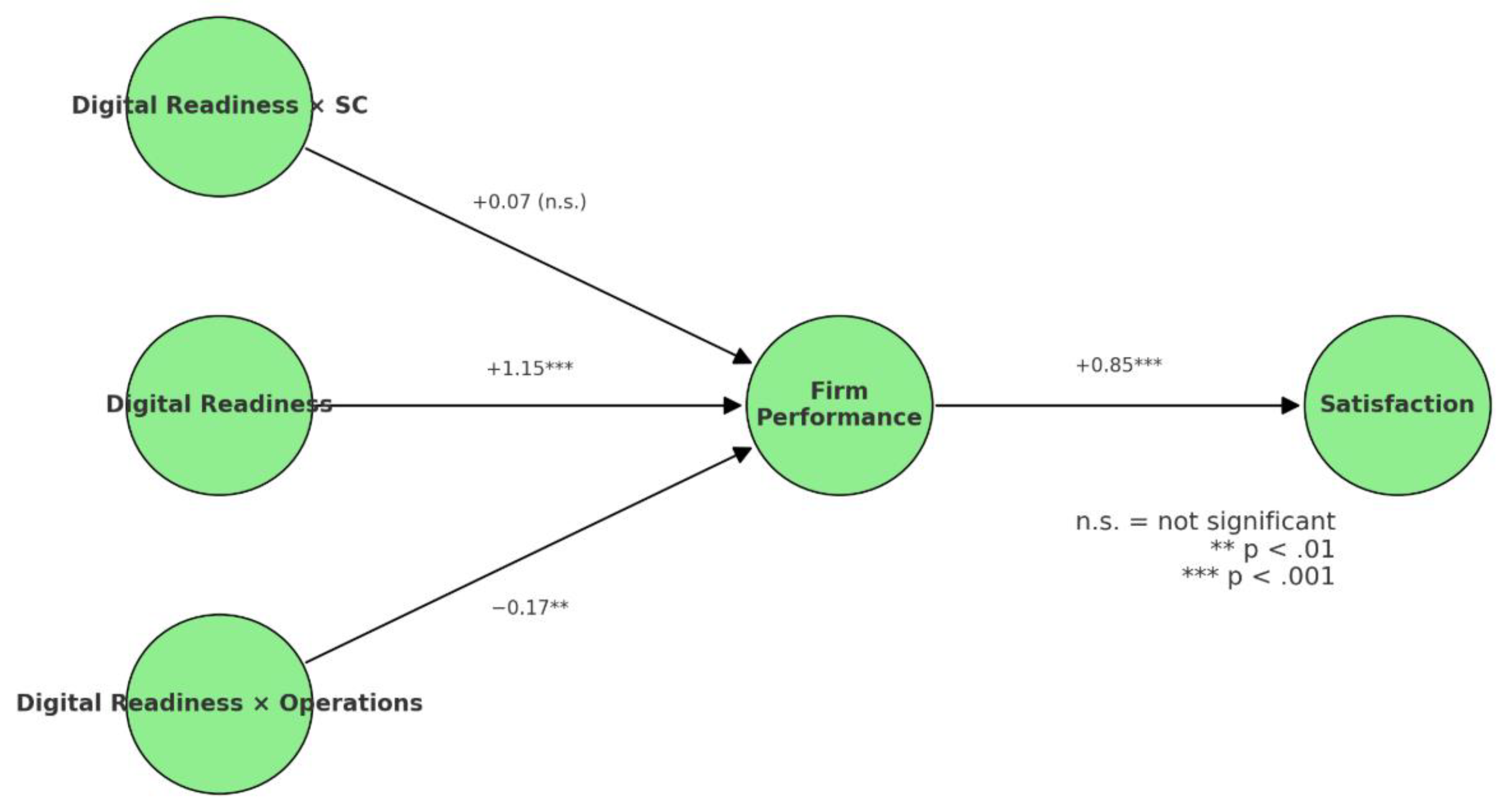

Based on the SEM results presented in Table 12, the proposed hypotheses were evaluated across two industry contexts—tourism and non-tourism micro and small enterprises (MSEs)—within the specified research framework. The analysis examined four hypotheses (H1–H4), focusing on the direct effect of digital readiness (DR) on firm performance (FP), the moderating effects of supply chain and internal operational issues, and the downstream influence of FP on satisfaction with digitalization (SD).

Table 12.

Multi-group SEM results for hypothesis testing in tourism and non-tourism MSEs.

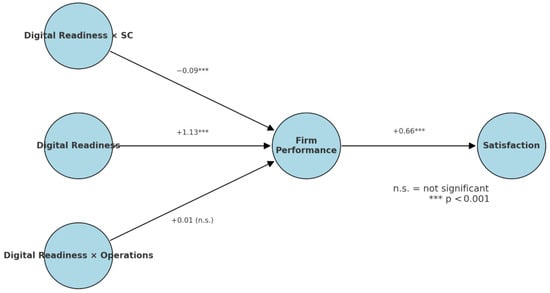

In the tourism sector, the results strongly support H1a, revealing that DR has a significant positive effect on FP (Estimate = 1.1297, p < 0.001). H2a is also supported, indicating that external (supply chain) issues significantly attenuate the positive influence of DR on FP (Estimate = –0.0909, p < 0.001). In contrast, H3a is not supported, as the interaction between DR and internal (operational) issues was not statistically significant (p = 0.427), suggesting no meaningful moderating effect. H4a is supported, with FP exerting a significant positive impact on SD (Estimate = 0.6644, p < 0.001).

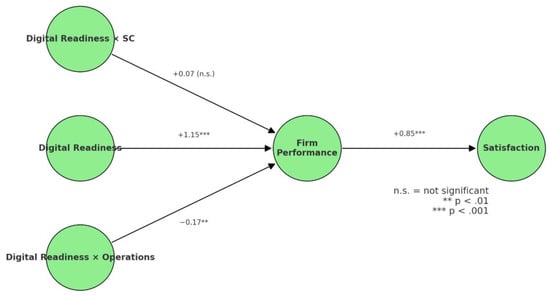

For the non-tourism group, the pattern is similar in some respects. H1b is supported, as DR significantly enhances FP (Estimate = 1.1485, p < 0.001). H2b, however, is not supported; the moderating effect of supply chain issues was not statistically significant (p = 0.101). H3b is supported, demonstrating that internal operational challenges significantly weaken the DR–FP relationship (Estimate = –0.1657, p < 0.001). H4b is again supported, showing that stronger firm performance leads to higher satisfaction with digitalization (Estimate = 0.8512, p < 0.001).

Overall, these findings affirm the positive role of digital readiness in improving firm performance across both sectors. However, they also highlight sector-specific differences in how internal and external contextual factors shape the effectiveness of digital initiatives. The consistent and significant impact of firm performance on digital satisfaction further underscores the critical link between digital capability, operational effectiveness, and perceived value in digital transformation.

Figure 2 visualizes the structural equation modeling (SEM) results for micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in the tourism industry. The model confirms that digital readiness has a significant positive effect on firm performance (H1a), and this relationship is negatively moderated by external (supply chain) issues (H2a). Internal (operational) issues do not significantly moderate the relationship (H3a). Furthermore, firm performance has a strong positive impact on satisfaction with digitalization (H4a).

Figure 2.

SEM results for tourism industry.

Figure 3 presents the SEM results for MSEs operating in non-tourism sectors. Digital readiness also significantly enhances firm performance (H1b). Unlike the tourism sector, external (supply chain) issues do not significantly moderate this relationship (H2b), whereas internal (operational) issues negatively moderate the effect (H3b). Similarly to tourism, firm performance strongly predicts satisfaction with digitalization (H4b).

Figure 3.

SEM results for Non-Tourism industry.

5.2. Comparing Tourism and Non-Tourism Sectors

To further explore differences between industry sectors, two independent-sample t-tests were conducted to compare firm performance and satisfaction with digitalization between tourism and non-tourism companies. These additional results emphasize the marked differences in both firm performance and satisfaction outcomes between tourism and non-tourism MSEs, underscoring the sectoral asymmetry in the digital transformation experience.

First, a comparison of firm performance revealed significant differences between the two sectors. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (F = 9.16, p = 0.003); thus, a Welch-adjusted t-test was employed. The results showed that tourism companies reported significantly higher levels of firm performance than non-tourism companies, t(174.04) = 16.85, p < 0.001. The mean difference was 3.16 (95% CI [2.79, 3.53]), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.38), suggesting substantial practical significance. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 13.

Table 13.

The descriptive statistics for firm performance by industry.

Levene’s test showed that the assumption of equal variances was met (F = 1.32, p = 0.252). The results indicated a statistically significant difference, with tourism companies reporting notably higher satisfaction levels, t(215) = 22.22, p < 0.001. The mean difference was 3.45 (95% CI [3.14, 3.75]), with a very large effect size (Cohen’s d = 3.06), highlighting strong practical implications. Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 14.

Table 14.

The descriptive statistics for satisfaction with digitalization by industry.

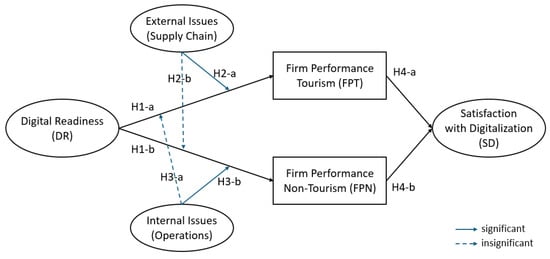

6. Summary of Hypothesis Testing

Table 15 summarizes the results of hypothesis testing. While the majority of hypotheses were empirically supported across both tourism and non-tourism sectors, H2b and H3a were not supported, highlighting subtle contextual differences in how digital readiness contributes to firm performance.

Table 15.

Summary of hypothesis testing.

H2b hypothesized that external (supply chain) issues would not significantly moderate the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance in non-tourism industries. Although the observed interaction effect was in the expected direction, it did not reach statistical significance. A plausible explanation is that even traditionally localized non-tourism sectors such as retail, logistics, and personal services are increasingly integrating digital platforms, vendor networks, and mobile payment systems. As such, their operational performance may be more susceptible to external disruptions—such as poor internet infrastructure or platform incompatibility—than previously assumed.

In contrast, H3a proposed that internal (operational) issues would not significantly moderate the digital readiness–performance relationship in the tourism sector. The analysis revealed a small but statistically insignificant interaction effect. This result may reflect heterogeneity among tourism MSEs. While many firms leverage external platforms (e.g., booking and review systems) and can mitigate internal shortcomings through outsourcing or lightweight digital tools, others—particularly smaller or less digitally mature firms—may still be hindered by internal resource constraints, such as lack of skilled personnel or inadequate internal workflows. This variation could dilute the anticipated moderating effect.

Together, these findings suggest that while digital readiness remains a robust predictor of firm performance, its effectiveness may vary depending on the degree of digital integration and operational dependencies within each sector. Future research should examine sector-specific contingencies and firm-level digital maturity in greater depth to refine our understanding of these moderating dynamics.

7. Discussion

This study empirically investigates the impact of digital readiness on firm performance and customer satisfaction in micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in Bhutan, with a focus on comparing the tourism and non-tourism industries. The findings indicate that digital readiness provides clear benefits for MSEs, but these benefits are highly dependent on the industrial context and environment [1,47].

Digital readiness positively influenced firm performance in both the tourism and non-tourism industries [5]. In the tourism industry, where there is high reliance on global markets, digital readiness leads to greater performance, and digitalization acts as a key driver of competitiveness [28,48]. In the non-tourism industry, while digital readiness also impacts performance, the effect is more pronounced in the context of a domestic market [30,31].

Furthermore, the moderating effects of contextual challenges revealed sector-specific asymmetries. In the tourism industry, external supply chain issues, particularly the lack of integration with global supply chains, weakened the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance [39]. This suggests that in the tourism industry, which relies on interactions with global networks, external supply chain issues have a greater impact on firm performance [28]. In contrast, in the non-tourism industry, external issues had less of an impact, and internal operational issues were a key factor negatively moderating the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance [34]. This reflects that in the non-tourism industry, where reliance on domestic markets is higher, internal capabilities play a more significant role in influencing firm performance [5].

Firm performance showed a strong positive relationship with satisfaction with digitalization in both industries. This suggests that digital readiness plays a critical role in converting performance into improved customer satisfaction, enhancing competitiveness [47]. In the tourism industry, digitalization plays a significant role in improving customer experience and satisfaction, which is empirically supported by Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) theory [39]. In the non-tourism industry, digitalization also plays a key role in enhancing customer satisfaction, and the Resource-Based View (RBV) explains how firm performance impacts customer satisfaction [5].

These findings highlight that digital readiness provides significant benefits to MSEs, but these benefits are heavily dependent on industry-specific constraints. In the tourism industry, digital strategies to address external supply chain issues are crucial, while in the non-tourism industry, strategies for addressing internal operational issues are necessary. Therefore, differentiating digital strategies based on industry needs is critical, as this will be a key strategic direction for firms to maximize digital readiness and maintain competitiveness in the market [3].

7.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study empirically analyzes the role of digital readiness in the digital transformation and MSE environment and explores the relationship between firm performance and customer satisfaction. It specifically demonstrates that digital readiness acts as a crucial variable in predicting firm performance in both the tourism and non-tourism industries, contributing to the development of Dynamic Capabilities Theory and the Resource-Based View (RBV). While previous studies have largely focused on large corporations and developed economies, this study confirms how digital readiness functions as a strategic asset that helps secure a competitive advantage in the resource-constrained MSE environment [3,5,12,13].

This study expands the understanding of how digital readiness can create competitive advantages in MSEs. Compared to previous research, it makes an important contribution by empirically illustrating how digital readiness enhances the dynamic capabilities of MSEs. Contingency Theory and RBV empirically reveal the asymmetric moderating effects of internal and external issues on the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance, explaining how digital transformation can vary across different industrial contexts [32]. This study found that, in the tourism industry, external supply chain issues significantly weaken the relationship between digital readiness and firm performance, while in the non-tourism industry, internal operational issues have a greater impact, highlighting the importance of sector-specific challenges [28,39]. It provides theoretical insights into the strategic use of digital readiness based on each industry’s characteristics, emphasizing the sector-specific context that differentiates this study from previous research.

Furthermore, Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) explains that digital readiness plays a key role in strengthening the relationship between customer satisfaction and firm performance. This study empirically confirms that digital readiness improves customer experience, enhances satisfaction, and leads to better firm performance [39]. By showing the important role of digital readiness in improving customer-centric services and digital experiences, it provides a new contribution to strengthening the link between customer satisfaction and firm performance.

Finally, this study emphasizes the importance of digital transformation in developing countries by empirically analyzing its impact on MSEs in contexts such as Bhutan. It shows that digital readiness plays a key role in enhancing competitiveness and improving market accessibility, contributing significantly to enabling global market access and achieving sustainable growth. Theoretical contributions are made by showing how digital technology adoption is crucial for global market access and sustainable growth [1]. This study provides valuable theoretical insights into how digital transformation in Bhutan can make significant strategic contributions to MSEs in developing countries.

7.2. Practical Contributions

This study provides valuable practical insights for managers and digital experts of MSEs in developing countries, especially in the tourism and non-tourism industries. The empirical findings emphasize that digital readiness plays a key role in enhancing firm performance, showing how digital technology adoption can improve competitiveness and operational efficiency. It was confirmed that even with limited resources, investments in systems like reservation platforms, e-payment solutions, inventory management software, and customer communication technologies can significantly improve operational efficiency, responsiveness, and competitiveness [47].

It is also important to note that the benefits of digital transformation are not equally evident across industries. The tourism sector, which is highly reliant on external factors, requires strong capabilities in managing external connections such as supply chain integration, platform linkages, and international service delivery. Policymakers can address these external barriers by enhancing policies that support cooperation with global platforms and digital infrastructure. For example, international standardization and ensuring technical compatibility for linking with digital payment systems are crucial. Additionally, policies to strengthen digital infrastructure and technical support are needed to help tourism MSEs gain competitiveness in the global market [28].

On the other hand, non-tourism MSEs face more prominent internal barriers, making policies aimed at strengthening internal capabilities critical. For instance, offering training programs to improve digital literacy, providing technical support networks, and conducting process improvement workshops can help strengthen internal capacities. Furthermore, technical consultation and infrastructure investment are needed to maximize the use of digital tools specialized for the non-tourism sector [5]. Policymakers must focus on building digital infrastructure and technical support networks to address the lack of technical resources for non-tourism MSEs.

Incentives linked to performance are necessary to promote digital adoption. Performance-based incentives such as tax benefits, subsidies, or digital certifications can drive digital adoption among small businesses. Since the strong relationship between digital readiness and firm performance was demonstrated in this study, such incentives can bring both economic benefits and improved customer experiences, helping businesses adopt digital technologies and improve customer-centric services [3].

Finally, the importance of continuous monitoring and evaluation of digital initiatives is emphasized. By tracking outcomes and challenges across industries, policymakers can fine-tune support mechanisms and analyze the effectiveness of digital transformation. Through accurate data analysis, the efficient allocation of resources and fair support for digital transformation can be ensured. Policymakers can play an important role in fostering an inclusive and sustainable digital transformation for MSEs through this approach.

7.3. Policy Implications

The practical implications derived from this study provide clear guidance for governments, development agencies, and digital economy advocates in promoting digital transformation. The policy approach to support digital transformation should be differentiated according to the characteristics of each industry, as this directly influences the digital readiness and performance improvement of each industry.

For the tourism industry, the policy implications emphasize the importance of strengthening digital infrastructure that supports digital connectivity, seamless payment processing, and international service provision. Governments can enhance the digital readiness and resilience of the tourism industry by increasing public investment in digital infrastructure and providing subsidies for integration with global platforms. This would enable digital technologies to strengthen the international competitiveness of the tourism industry and facilitate smoother access to global markets [28].

For non-tourism MSEs, strengthening internal capabilities is crucial. Programs such as digital literacy education, technical support, and process improvement workshops play an essential role in overcoming internal barriers. Collaboration with industry associations, local education providers, and technology vendors can be key in strengthening internal capabilities. Policymakers can enhance digital readiness by offering digital education programs and technical advisory support [3].

Furthermore, performance-linked incentives to promote digital adoption are needed. Tax benefits, subsidies, or digital certification are examples of performance-based incentives that can stimulate digital adoption among small firms. Since the strong relationship between digital readiness and firm performance has been proven in this study, such incentives can have a dual effect of enhancing economic benefits and improving customer experience. These incentives would contribute to providing firms with the foundation to adopt digital technologies and improve customer-centric service [47].

Moreover, it is crucial to monitor and evaluate digital initiatives continuously. By tracking outcomes and identifying challenges across industries, policymakers can refine support mechanisms and ensure the effective allocation of resources. A data-driven approach is vital for ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently and that support for digital transformation is fair and equitable. Policymakers can play a significant role in promoting a comprehensive and sustainable digital transformation for MSEs by ensuring the effective distribution of resources and equitable support [1].

Finally, recent studies emphasize the importance of digital transformation in achieving sustainable business practices. Zhong et al. [63] highlight how digital transformation strategies, particularly in the energy sector, can play a key role in promoting sustainable practices. Their research provides valuable insights into how small businesses in developing economies like Bhutan can leverage digital tools to align business objectives with sustainability goals.

7.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study provides valuable insights into the relationship between digital readiness, firm performance, and customer satisfaction in Bhutan’s MSEs, but it has several limitations.

The first limitation is the cross-sectional design, which restricts the establishment of causal relationships. While the relationships identified in this study are statistically significant, they represent a snapshot in time, and as digital maturity progresses or external environments change, these relationships may evolve. Future research should adopt longitudinal studies to track how digital transformation develops over time.

The second limitation concerns bias due to self-reporting. Responses on firm performance, operational issues, and satisfaction may be influenced by perceptual bias or social desirability bias. To overcome this, future research should incorporate objective financial indicators or operational data and cross-analyze survey data with interviews or financial records to increase the reliability and validity of the data. While this study analyzed the relationship between digital readiness and performance using subjective survey data, adding objective data would strengthen the validity of the research.

Third, while this study compares the tourism and non-tourism industries, there may be additional diversity within each industry. For example, considering the differences between domestic tourism and international tourism, or between agriculture and retail, would provide a more detailed explanation of the differences between industries. Future research should explore the patterns of digitalization and challenges in more depth through industry segmentation.

Fourth, this study used snowball sampling to collect data, which may limit the representativeness of the sample. Future research should consider using random sampling or a larger sample size to draw more generalized conclusions.

Finally, Bhutan offers a relatively under-researched context for digital transformation studies, and there may be limitations when applying the results of this study to other developing or developed countries. Future research should delve deeper into how digital transformation manifests differently across countries and industries and understand the contextual constraints. This would expand the framework of existing research and provide more generalizable results.

Additionally, future research should explore how digital readiness applies differently across the characteristics of firms, such as firm size and industry type. For example, investigating how the relationship between digital readiness and performance may vary between micro-enterprises and small enterprises could reveal the need for tailored strategies for digital transformation. Research proposing differentiated approaches based on firm size or industry characteristics will be crucial in contributing to the successful implementation of digital transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.J. and J.M.K.; methodology, J.Y.J.; software, J.Y.J.; validation, J.Y.J., R.K.M. and J.M.K.; formal analysis, J.Y.J.; investigation, J.Y.J.; resources, J.Y.J.; data curation, J.Y.J. and R.K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.J. and J.M.K.; writing—review and editing, R.K.M.; visualization, J.Y.J.; supervision, J.Y.J.; project administration, J.Y.J.; funding acquisition, J.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Due to space constraints, we do not report the full results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). However, all items loaded significantly and strongly onto their respective constructs, with standardized factor loadings above 1.0 and z-values significant at p < 0.001. Residual variances were within acceptable ranges. These results confirm convergent validity and support the adequacy of the measurement model. |

References

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. In Managing Digital Transformation, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range planning 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Pereira, S.C.F.; Telles, R.; Machado, M.C. Industry 4.0 and digital supply chain capabilities: A framework for understanding digitalisation challenges and opportunities. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 1761–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A. Strategic Innovation: New Game Strategies for Competitive Advantage; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, I.C.; Queiroz, G.A.; Junior, P.N.A.; de Sousa, T.B.; Yushimito, W.F.; Pereira, J. Sustainable digital transformation in small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A review on performance. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deku, W.A.; Wang, J.; Preko, A.K. Digital marketing and small and medium-sized enterprises’ business performance in emerging markets. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 18, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How smart, connected products are transforming competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Haddud, A.; Khare, A. Digitalizing supply chains potential benefits and impact on lean operations. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2020, 11, 731–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L. Research on successful factors and influencing mechanism of the digital transformation in SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysokińska, Z. A review of the impact of the digital transformation on the global and European economy. Comp. Econ. Research. Cent. East. Eur. 2021, 24, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mićić, L. Digital transformation and its influence on GDP. Econ.-Innov. Econ. Res. J. 2017, 5, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazab, M.; Alhyari, S.; Awajan, A.; Abdallah, A.B. Blockchain technology in supply chain management: An empirical study of the factors affecting user adoption/acceptance. Clust. Comput. 2021, 24, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.K.; Wang, J.; Brooks, W.; Angel, V. Digital transformation and socio-economic development in emerging economies: A multinational analysis. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Arancibia, J.; Hochstetter-Diez, J.; Bustamante-Mora, A.; Sepúlveda-Cuevas, S.; Albayay, I.; Arango-López, J. Navigating digital transformation and technology adoption: A literature review from small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanti, T.; Kom, S.; MM, M.; Nuraini, R.; Apol Pribadi, S. A comparative analysis review of digital transformation stage in developing countries. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2023, 16, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, H. Digital transformation, development and productivity in developing countries: Is artificial intelligence a curse or a blessing? Rev. Econ. Political Sci. 2022, 7, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed; Free Press: Tampa, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business model design and the performance of entrepreneurial firms. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. The fit between product market strategy and business model: Implications for firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B. Strategic corporate social responsibility and value creation among large firms: Lessons from the Spanish experience. Long Range planning 2007, 40, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, A. Digital Transformation for a Sustainable Bhutan. Druk. J. 2020, 6, 17–27. Available online: https://drukjournal.bt/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Digital-Transformation-for-a-Sustainable-Bhutan.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Tobgye, S. Digital Transformation in Bhutan: Culture, Workforce and Training; Queensland University of Technology: Brisbane City, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Biggemann, S.; Williams, M.; Kro, G. Building in sustainability, social responsibility and value co-creation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaev, A.; Lenny Koh, S.; Szamosi, L.T. The cluster approach and SME competitiveness: A review. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2007, 18, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. Technology Readiness Index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 2, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Formica, S.; O’leary, J.T. Searching for the future: Challenges faced by destination marketing organizations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Bule, L.; Petrovska, K. Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises: Aspects of public support. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L. The Contingency Theory of Organizations; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Omrani, N.; Rejeb, N.; Maalaoui, A.; Dabić, M.; Kraus, S. Drivers of digital transformation in SMEs. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 5030–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahadat, M.H.; Nekmahmud, M.; Ebrahimi, P.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Digital technology adoption in SMEs: What technological, environmental and organizational factors influence in emerging countries? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023, 09721509221137199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slimane, S.; Coeurderoy, R.; Mhenni, H. Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises: A systematic literature review and an integrative framework. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2022, 52, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D.R. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F. Investigating structural relationships between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for air passengers: Evidence from Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Gursoy, D. Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L.; Whang, S. Winning the last mile of e-commerce. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2001, 42, 54–62. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/winning-the-last-mile-of-ecommerce/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Lam, S.Y.; Shankar, V.; Erramilli, M.K.; Murthy, B. Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: An illustration from a business-to-business service context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Henard, D.H. Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]