Abstract

Business model innovation represents a critical pathway for firms to create value and enhance competitiveness, yet innovation processes are frequently constrained by resource limitations. To explore the determinants of business model innovation, we developed a theoretical framework examining the influence mechanism of resource bricolage on business model innovation, introducing digital transformation as a mediating variable and entrepreneurship as a moderating variable. We conducted an empirical study by surveying 263 entrepreneurs across China. Using Model 59 in the PROCESS macro for SPSS, we performed conditional process analysis, revealing that both resource bricolage and digital transformation positively influence business model innovation, and resource bricolage facilitates digital transformation. Furthermore, digital transformation partially mediates the relationship between resource bricolage and business model innovation, while entrepreneurship positively moderates the relationships among resource bricolage, digital transformation, and business model innovation, with higher levels of entrepreneurship demonstrating stronger moderating effects. Our findings suggest that organizations pursuing business model innovation must consider the integrated effects of multiple factors within a systems perspective.

1. Introduction

The business model epitomizes an enterprise’s value proposition, value creation, and value capture approaches and is closely connected to corporate strategy and innovation management [1]. Developing a successful business model alone is insufficient to ensure competitive advantage, as competitors can easily imitate its fundamental elements once implemented. In today’s intense market competition, enterprises must rely on business model innovation to obtain enduring competitive advantages [2,3] and achieve strategic objectives and performance growth [4]. The triggering conditions for business model innovation include changes in external marketing environments and consumer demands, the introduction of new technologies and deepening digitalization [5], and internal factors such as entrepreneurial spirit, knowledge management dynamic capabilities [6], organizational structure, and corporate culture modifications [7]. These triggering factors can transform into driving forces for business model innovation or, if mismanaged, become barriers to innovation.

This study is particularly relevant in the Chinese context, where the government has implemented a series of policies to accelerate digital transformation and innovation. The ‘Digital China Construction Overall Layout Plan’ (2024) and “Made in China 2025” set ambitious goals for digitalization, aiming to establish comprehensive digital infrastructure by 2025 and position China among global leaders in digitalization by 2035. This plan emphasizes the development of digital infrastructure (such as 5G networks and computing centers) and incorporates digitalization performance into official evaluation mechanisms. Additionally, China has strengthened intellectual property protection through amendments to the Patent Law and introduced data protection regulations, including the Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law. In 2025, the emergence of the Chinese open-source AI model DeepSeek marked a notable shift in digital awareness, with government, enterprises, and the general public all showing increased recognition of digital transformation’s significance. These institutional arrangements, coupled with tax incentives and subsidies for innovative enterprises, create a distinctive environment for business model innovation and digital transformation in China.

The resource-based view indicates that business model innovation requires support from multiple types of resources, as enterprises are heterogeneous collections of resources [8]. Both new ventures and established enterprises face resource constraints, though in different ways. New ventures often struggle to acquire external resources [9], while established enterprises may have formed path dependencies in their innovation processes despite possessing diverse resources [10]. In both cases, resource bricolage—utilizing and creatively reconfiguring existing resources—becomes essential for realizing corporate strategy [11]. Digital transformation provides an advantageous opportunity for enterprise innovation, particularly under the influence of COVID-19 [12]. Business model innovation does not necessarily require new technologies, but new technologies typically can serve as catalysts for business model innovation [13].

Digital transformation is a highly complex, company-wide endeavor, and the integration and utilization of new digital technologies constitute one of the greatest challenges currently facing enterprises [12]. Rather than depending on a single condition, successful transformation emerges from the interplay between environmental uncertainty and resource coordination. Enterprises that effectively engage in resource bricolage—rebuilding, integrating, and utilizing available resources—can facilitate smoother digital transformation [13]. Digital technologies amplify dynamic capabilities, enabling entrepreneurs to more efficiently leverage their abilities to realize business objectives [14].

Resource bricolage, business model innovation, and digital transformation all fall within the domain of corporate entrepreneurship [15], which involves inherent risks and requires transformational leadership [16]. Some enterprises have established Chief Digital Officers (CDOs) to promote enterprise resource integration, strengthen digital transformation, and accelerate business model innovation [17,18,19]. Existing qualitative research examines entrepreneurship in digital contexts [20,21] and highlights the need for alignment between entrepreneurial activities and environmental changes [22]. While entrepreneurial bricolage has been studied in various contexts [9,23,24], its specific role in facilitating digital transformation remains underexplored. The current literature also predominantly examines bricolage and business model innovation at the organizational level, neglecting the crucial micro-level practices that shape these processes [25]. The influence of middle and lower-level managers’ bricolage activities on business model innovation, though potentially significant, remains understudied in digital transformation contexts.

While previous studies have examined business model innovation as a mediator between entrepreneurial bricolage and sustainable performance [26], there remains a significant gap in empirical research investigating digital transformation’s mediating role between resource bricolage and business model innovation. A critical limitation in the existing literature is the lack of empirical attention to how entrepreneurial orientation contingently affects the resource bricolage–digital transformation–business model innovation pathway. Though research acknowledges entrepreneurship’s importance [10,27], few studies examine how varying levels of entrepreneurship moderate these relationships. Another significant research gap concerns the contextual limitations of current studies. Most research on bricolage and business model innovation has been conducted in Western contexts or focused on startups [28,29], leaving a substantial knowledge void in understanding how these processes unfold in established organizations operating in diverse institutional environments, particularly during strategic digital transformation initiatives.

Drawing upon the identified research gaps, this study develops an integrated theoretical framework examining how resource bricolage influences business model innovation. We employ conditional process analysis methodology, positioning digital transformation as a mediating variable and entrepreneurship as a boundary condition. Specifically, our moderated mediation model investigates the following: (1) the direct effect of resource bricolage on business model innovation; (2) the mediating role of digital transformation in this relationship; and (3) the moderating influence of entrepreneurship on both direct and indirect pathways. We empirically test this framework using data collected through structured questionnaires from enterprises engaged in digital transformation initiatives.

This research advances the literature in three significant ways. First, it extends resource-based theory by elucidating how organizations can strategically deploy resource bricolage to overcome constraints during digital transformation. Second, by examining digital transformation as a mediating mechanism, this study illuminates the dynamic process underlying successful innovation in resource-constrained environments. Third, through investigating entrepreneurship as a boundary condition, we identify when and how resource bricolage most effectively facilitates business model innovation. Collectively, these contributions enhance understanding of how enterprises navigate resource constraints to achieve innovation in an increasingly digital business landscape while offering evidence-based recommendations for managerial practice.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, develops theoretical hypotheses, and presents the conceptual framework. Section 3 details our methodological approach, including data collection procedures and scale development. Section 4 reports empirical findings from hypothesis testing. Finally, Section 5 discusses theoretical contributions and managerial implications alongside limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Resource Bricolage and Business Model Innovation

A business model can be conceptualized as a mechanism that creates and delivers value to customers and partners through collaborative and economic activities, ensuring organizational connections with external stakeholders [1]. Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) illustrated business model components and innovation processes through their business model canvas framework, which comprises nine building blocks: customer segments, value propositions, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partnerships, and cost structure [30]. Scholars define business models and business model innovation differently based on their perspectives. Foss and Saebi (2016) conceptualized business model innovation as designed, novel, and non-trivial changes to key elements of a company’s business model and/or the architecture connecting these elements [7].

Business model innovation aims to satisfy overlooked market needs, introduce new technologies, products, and services, improve or disrupt existing markets through enhanced business models, and create entirely new markets [30]. Such innovation necessitates new approaches to connecting market elements and product markets, articulating value propositions for revenue generation—processes requiring supplementary resources in the form of new knowledge, skills, and capabilities [3]. Business model innovation may involve innovating one or multiple elements and their relationships, introducing entirely new business models, or fundamentally reconstructing existing ones. While business models and their innovations cannot be directly captured and identified, they can be analyzed through frameworks centered on corporate value propositions, incorporating elements such as internal and external relationships, core competencies, profit models, and business processes [31].

Bricolage refers to utilizing available resources to accomplish tasks. From an entrepreneurial resource perspective, resource bricolage involves integrating available resources to address new problems and develop opportunities, describing how entrepreneurs combine resources to create value [11,32,33]. This conceptualization extends the resource-based view (RBV) by emphasizing not merely the possession of valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources but also the entrepreneurial capacity to reconfigure and repurpose existing resources in novel ways. While traditional RBV focuses on resource heterogeneity as a source of competitive advantage, bricolage theory highlights the importance of resource orchestration and improvisation, particularly under constraints.

Resource bricolage encompasses “making do”, “overcoming resource constraints”, and “improvisation”-concepts reflecting entrepreneurial resource characteristics from different angles. Resource bricolage theory reveals mechanisms for realizing entrepreneurial resource value while considering how entrepreneurial resource decisions are influenced by social, environmental, and institutional contexts [34], further refining resource-based theory.

The scope of resource bricolage encompasses all enterprise resources, including physical inputs, labor skills, customer/market assets, and institutional and regulatory environments, with similar resource requirements across different enterprises. Li et al. (2019) categorized manufacturing enterprise resources into five types: technological, human, financial, physical, and reputational resources, and proposed four resource integration categories based on business model core elements: value proposition, external relationships, business processes, and profit models [35]. Enterprises integrating heterogeneous resources create different combinations that facilitate value creation and drive business model innovation.

Resource bricolage not only alters the utilization of available resources but emphasizes a resource management logic [36] consistent with ambidextrous innovation—exploitative and exploratory innovation [37]. Exploitative resource bricolage emphasizes utilizing existing resources within established cognitive and behavioral patterns to minimize trial-and-error costs and meet minimum entrepreneurial resource requirements. Exploratory resource bricolage examines existing resource attributes and values from new perspectives, focusing on discovering novel applications for current resources [38].

Beyond structural adaptation of resources, bricolage also involves cultural and symbolic dimensions critical to innovation. As Battistella et al. (2012) demonstrate through their meaning strategy framework, value creation depends not only on resource reorganization but also on the ability to attribute new meanings to business models [39]. Several specific mechanisms explain how resource bricolage enables business model innovation. First, resource bricolage facilitates the development of novel value propositions by encouraging firms to repurpose existing resources in unconventional ways. Witell et al. (2017) demonstrated that firms engaging in bricolage developed innovative service offerings by recombining existing resources, resulting in unique value propositions that competitors could not easily replicate [28]. Second, a bricolage mentality fosters creative problem-solving approaches that overcome rigid business model thinking. As Guo et al. (2016) empirically established, entrepreneurs who practiced bricolage demonstrated greater flexibility in redesigning business processes and revenue models when facing market uncertainties [40]. Third, resource bricolage enables firms to experiment with business model configurations at lower costs. Senyard et al. (2014) found that resource-constrained ventures employing bricolage techniques could test multiple business model variations without substantial resource commitments, accelerating the innovation process [24].

While some scholars suggest that excessive resource bricolage might lead to suboptimal business models [41], the preponderance of evidence suggests a positive relationship. For instance, Fisher’s (2012) comparative study of effectuation, causation, and bricolage revealed that bricolage-oriented firms were more likely to implement significant business model changes when facing resource constraints compared to those using causation approaches [42]. This positive association appears particularly robust in dynamic environments where resource limitations are common and traditional business models face disruption [43].

The objects of resource bricolage often constitute critical elements needed for business model innovation, enabling enterprises to break free from the constraints of prior resource utilization experiences. Through bricolage, organizations creatively reconstruct available resources to develop new value propositions, collaboration methods, and transaction models, ultimately forming new business models that may range from incremental improvements to radical reconfigurations. Based on this theoretical foundation and empirical evidence, we hypothesize:

H1:

Resource bricolage has a positive effect on business model innovation.

2.2. Resource Bricolage and Digital Transformation

Based on a comprehensive literature review, Vial (2019) defines digital transformation as a process aimed at improving entities by triggering significant changes in their properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies [44]. Digital transformation represents an ongoing strategic renewal process that leverages advancements in digital technologies to build capabilities for updating or replacing organizational business models, collaboration methods, and culture [21]. Verhoef et al. (2021) categorize digital transformation into three stages: digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation [45]. This process begins with digital technology, integrates it with organizational elements, and ultimately serves customers.

Through interviews with executives, Kane (2019) summarizes the digital transformation process of enterprises into three stages: early-stage, developing, and maturing companies [46]. He points out that the technological challenges enterprises face are fundamentally concerned with whether technologies are appropriately utilized. The digital transformation process requires support from tangible resources, intangible resources, and human skills [47]. Li (2020) suggests that in the rapidly changing digital economy, only one or two winners will remain in each niche market [20], at which point some enterprises may consider achieving dynamic, sustainable advantage temporarily through combinations of continually developing temporary advantages.

Research on Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises engaged in cross-border e-commerce demonstrates how entrepreneurs leverage third-party platforms to implement changes in management models and resource approaches, driving enterprise digital transformation [48]. Through resource bricolage, enterprises can overcome limitations, exercise improvisational capabilities, and enable simultaneous planning and execution during digital transformation [49].

A key mechanism linking resource bricolage to digital transformation is the ability to repurpose existing resources for digital initiatives without requiring significant new investments. Resource bricolage enables firms to experiment with digital technologies in low-risk ways, combining available technological and non-technological resources to create innovative digital solutions [10]. This approach is particularly valuable in the early stages of digital transformation when uncertainty is high, and resources may be limited.

Empirical evidence supports this relationship. For instance, [27] found that SMEs successfully navigating digital transformation frequently employed bricolage techniques to compensate for resource limitations, reconfiguring existing capabilities for digital contexts. Similarly, Nylén and Holmström (2015) [50] documented how media organizations undergoing digital transformation relied on bricolage to repurpose existing content, technologies, and competencies when creating digital platforms.

However, the relationship between resource bricolage and digital transformation is not without complexities. Some scholars caution that the improvisational nature of bricolage may lead to fragmented digital initiatives, as it typically involves working with what’s available rather than following a strategic plan. This may result in initiatives that are not fully aligned with long-term strategic goals [51]. In their study of new ventures, Li and Yu (2023) distinguished between defensive and creative improvisation, finding that both affect venture performance but through different bricolage mechanisms [51]. Nevertheless, when operating under resource constraints, the ability to leverage bricolage for digital transformation appears to offer significant advantages over traditional resource acquisition strategies, particularly when transformation speed is critical [52].

H2:

Resource bricolage has a positive effect on digital transformation.

2.3. Digital Transformation and Business Model Innovation

Digital transformation reduces dependence on physical elements. Innovation in new business models is primarily based on the adoption of digital infrastructure, reflecting the dematerialization characteristics of processes [53]. The diverse forms of digital technology have become a fundamental element in daily life [54]. Early research focused on how IT strategy evolved from business-level strategy to commercial strategy and how to acquire resources for creating and capturing value in digital enterprise strategy. The operational aspect of digitalization is product innovation, which redefines products, changes business models or generates new business logic [55]. Based on understanding digital innovation, entrepreneurs should avoid the misconception of being obsessed with digital technology. This is because technology by itself has no single objective value; mediocre technology applied to a great business model may be more valuable than great technology exploited by a mediocre business model.

Digital transformation supports enterprises in adopting new methods of value creation and capture, new exchange mechanisms and transaction architectures, and new cross-boundary organizational forms. The application of digitalization significantly reduces transaction costs of information collection, communication, and control activities, optimizes existing processes, and improves the overall efficiency and quality of products and services, leading to the disruption of established business models and the formation of new ones [56]. The mechanism by which digital transformation influences business model innovation is a question that enterprises must consider, as it can reduce path dependence in the enterprise innovation process.

Path dependence may cause established business models to become inertial and eroded over time. However, if enterprises directly engage in radical, disruptive innovation, they may face high risks and low feasibility. In such scenarios, enterprises can consider using digital transformation for incremental innovation, expanding, modifying, or terminating existing business activities. Zhang Z. et al. (2022) suggest that as the degree of enterprise digital transformation deepens, enterprises reorganize resources needed for business model innovation, promote internal process transformation [57], and thereby achieve integration of R&D, production, and marketing processes. Their empirical study verified that digital transformation is a key influencing factor for enterprises to maintain competitive advantage and achieve business model innovation. Once digital transformation alters a company’s business model, the company is likely to pursue various strategies to improve its performance [58].

H3:

Digital transformation has a positive effect on business model innovation.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Digital Transformation

In the digital economy era, the barriers to enterprise resource bricolage have been significantly reduced. The openness, traceability, and accessibility of data have gradually rendered obsolete the traditional approach of hiding advantageous resources through information asymmetry. Digital transformation breaks the spatial limitations of resources, making the scope and content of resource bricolage more extensive. Digital transformation can build, update, or replace organizational business models and collaboration methods, forming unique enterprise advantages. Successful digital transformation changes the mindset at employee, leadership, and organizational levels, generating a more agile, tolerant, experimental, and collaborative culture within the enterprise [46] and providing direction for enterprise development.

When enterprises decide to conduct business differently in the digital world, they invest time, energy, and resources in the right places, subsequently utilizing resource bricolage to repeatedly experiment and drive processes forward. Based on the three key capabilities of digital transformation—de-coupling, disintermediation, and driving generativity [59]—reasonable resource bricolage can encourage enterprises to reshape how they create, deliver, and capture value, promoting the realization of value propositions and achieving business model innovation goals.

To more fully understand this mediating relationship, it is important to examine the theoretical foundations connecting these constructs. Resource bricolage represents a starting point for innovation under constraints, where enterprises manage the available resources in novel ways [9]. However, the path from bricolage to business model innovation is not necessarily direct or complete without transformation mechanisms. Digital transformation provides these mechanisms by enhancing how bricolage-derived solutions can be scaled, integrated, and commercialized.

Digital transformation amplifies the effects of resource bricolage by providing technological platforms that extend the reach and impact of recombined resources. While resource bricolage may generate novel solutions, digital transformation provides the architectural foundation that allows these solutions to be systematically integrated into new business models. In the context of business model innovation, the incorporation of tools like social media or big data is often motivated by a company’s strategic objectives and its desire to align with innovative-related motivations [60]. Digital transformation provides the dynamic capabilities needed to sustain and evolve bricolage-derived innovations over time. These capabilities allow firms to recognize when bricolage solutions have broader potential, mobilize resources to capitalize on this potential, and reconfigure organizational structures to accommodate new business models.

H4:

Digital transformation acts as a partial mediator between resource bricolage and business model innovation.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship has always played a vital role in organizational and economic growth, representing a shared belief among entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship is a process of organizational renewal, encompassing two dimensions: innovation and risk-taking and strategic renewal. It is influenced by internal and external environments and corporate strategy, ultimately affecting firm performance. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) consider entrepreneurship to be an important characteristic of high-performing companies [61]. They define entrepreneurship as the new entry, while entrepreneurial orientation describes how new entry occurs, distinguishing five characteristic dimensions of entrepreneurship: autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness.

This moderation operates through three key mechanisms. First, entrepreneurship amplifies the effectiveness of resource bricolage for digital transformation by encouraging creative resource combinations and fostering resilience when facing technological challenges. Digital transformation brings new opportunities for enterprises but also introduces technological challenges [62]. According to the Dynamic Capability Theory, digital transformation weakens resistance but enhances recovery capacity in firms. Enterprises must continuously adapt to new technologies and resolve technical difficulties. Entrepreneurship helps enterprises better address these challenges because it emphasizes innovation, experimentation, and rapid learning. Entrepreneurs use their networks in new ways during bricolage processes, resulting in more resources and redeployment opportunities for developing new products, markets, and operational efficiencies.

Second, entrepreneurship enhances how digital transformation capabilities translate into business model innovations by promoting experimentation and reducing fear of failure during business model reconfiguration [63]. The process of digital transformation resembles a journey, with management and culture being the most prominent obstacles. Therefore, digital transformation requires both technology and a clear organizational vision driven by leaders with dynamic management capabilities. Entrepreneurship needs to be transmitted from top management to all employees, avoiding the phenomenon where middle managers and employees become barriers to innovation [64]. With advancing digital transformation, the CDO role has emerged to implement transformation activities and drive organizational change, breaking existing operating logic and acting as institutional entrepreneurs who help reconfigure resource bases and enhance resource bricolage capabilities.

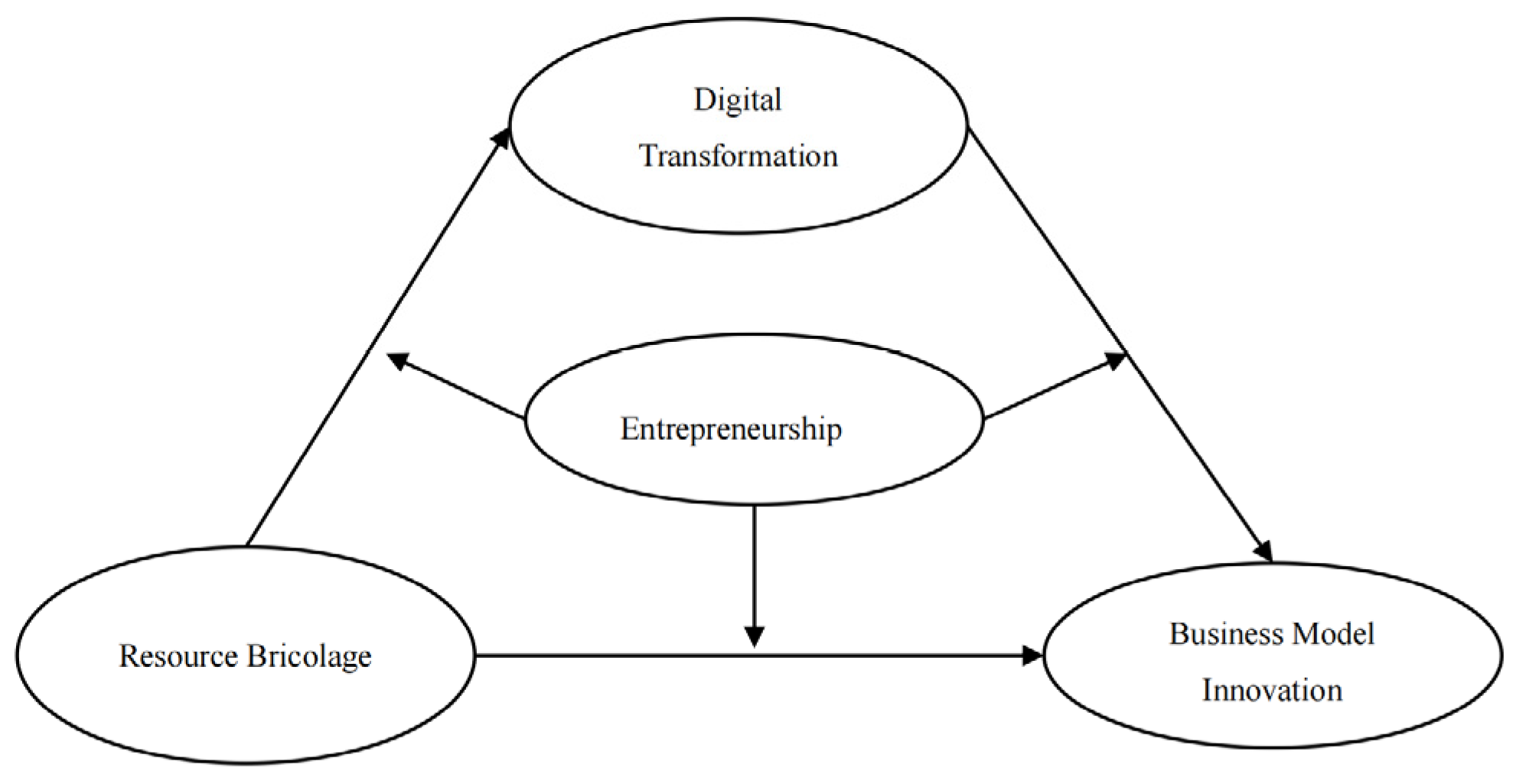

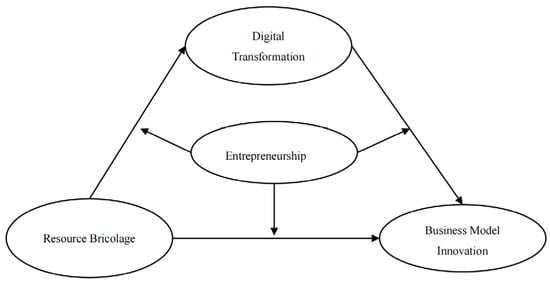

Third, entrepreneurship strengthens the direct relationship between resource bricolage and business model innovation by providing the strategic vision needed to align improvised resource solutions with overarching business model objectives. Entrepreneurship possesses adaptability, supporting enterprises in conducting interactive and supportive innovation under resource-constrained environments, thereby generating sustainable competitive advantages. Entrepreneurs create new products, processes, or new markets. Entrepreneurs must often make decisions in highly uncertain, high-risk, different digital technology [65] and time-pressured environments, necessitating structured thinking, engagement in bricolage, implementation, and cognitive adaptation [66]. The conceptual framework presented in Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical foundation and key components of this study.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

H5a:

Entrepreneurship can positively moderate the relationship between resource bricolage and digital transformation.

H5b:

Entrepreneurship can positively moderate the relationship between digital transformation and business model innovation.

H5c:

Entrepreneurship can positively moderate the relationship between resource bricolage and business model innovation.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

We collected data through a survey questionnaire targeting Chinese enterprises that had implemented digital transformation and business model innovation initiatives. The specific respondents were middle and senior management personnel.

3.1.1. Questionnaire Development and Translation Process

Since some scales were originally in English but the actual survey participants were Chinese-speaking, the questionnaire items underwent a translation and back-translation process following [67]’s approach to ensure conceptual equivalence. We engaged bilingual researchers to translate the scales and resolve any discrepancies through discussion.

To address potential legal concerns, we invited legal professionals to review the questionnaire to avoid issues related to corporate privacy or other unintended problems. The questionnaire items primarily focused on enterprise conditions and did not involve personal information about the managers, which indirectly increased respondents’ willingness to participate.

3.1.2. Data Collection

The questionnaire development followed a two-stage validation process. First, we conducted a pilot test with 15 managers from various industries to assess item clarity, relevance, and cultural appropriateness. Based on their feedback, we made minor wording adjustments to improve comprehension while maintaining the conceptual integrity of the original scales. Their responses were included in the final dataset after confirming the questionnaire’s validity.

Subsequently, we commissioned Credamo, a professional Chinese survey firm, to collect additional data using the validated questionnaire. The survey was administered online through Credamo’s secured platform, ensuring respondent anonymity and data security. Participants were recruited from Credamo’s national business panel through stratified random sampling to ensure representation across different industries and company sizes. After a two-month distribution process, we combined our initial 15 pilot responses with 248 valid questionnaires collected by Credamo, yielding a total of 263 valid questionnaires for analysis. These were selected from an initial pool of approximately 350 responses after removing incomplete responses, and those that failed attention check questions.

The industries represented by the surveyed managers included traditional manufacturing (64, 24.33%), traditional services (85, 32.32%), high-tech industries (56, 21.29%), commercial and distribution businesses (42, 15.97%), and others (16, 6.08%). For further statistical details, please refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 263).

3.2. Measures

Data were collected through a structured questionnaire comprised of demographic information and scales. The questionnaire began with demographic items collecting information about respondents’ organizations (industry sector, company size measured by number of employees, and organizational age) and respondent position. These demographic variables served as control variables in our analysis. The main body of the questionnaire consisted of four multi-item constructs: (1) Resource Bricolage (independent variable), (2) Digital Transformation (mediating variable), (3) Business Model Innovation (dependent variable), and (4) Entrepreneurship (moderating variable). Each construct contained multiple indicator items to ensure a comprehensive measurement of the underlying theoretical dimensions. All items employed a seven-point Likert response format ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

In total, the questionnaire comprised 32 measurement items across the four main constructs, in addition to the demographic questions. The specific operationalization and measurement development for each construct are detailed below.

Resource Bricolage (Independent Variable, hereafter RB): Drawing from Feng et al. (2020) [68] and Senyard et al. (2014) [24], we developed eight items for measurement. Sample items include “When facing new challenges, our company is confident in finding viable solutions using existing organizational resources” and “Compared to other enterprises, our company can leverage existing resources to address more challenges”.

Business Model Innovation (Dependent Variable, hereafter BMI): This study adapted established scales [30,57] to develop nine measurement items. Sample items include “In the past 3 years, we have developed new products or services” and “In the past 3 years, we have identified and served new markets and customer segments”. The items covered nine factors related to business model innovation: products or services, markets and customer segments, resources and capabilities, core processes and activities, strategic business partners, customer relationships, channels, cost structure, and revenue streams.

Digital Transformation (Mediating Variable, hereafter DT): This scale was developed by synthesizing multiple perspectives, resulting in six items [69,70]. Sample items include “In the past 3 years, our company has adopted digital technologies to transform and upgrade existing products, services, and processes” and “In the past 3 years, our company has comprehensively promoted digital design, manufacturing, and management”.

Entrepreneurship (Moderating Variable, hereafter ES): Centered on innovation and incorporating proactiveness and risk-taking dimensions [71,72], this construct was measured using nine items. Sample items include “We emphasize research and development, technology leadership, and innovation” and “We implement significant product or service changes to gain a competitive advantage”.

Following comparable research, we selected organizational size (number of employees), organizational age, and industry as control variables [69,73]. These variables frequently influence innovation processes and outcomes in entrepreneurial contexts and were included to isolate the effects of our focal constructs.

For data analysis, we used SPSS 26.0 for descriptive statistics, reliability analysis, and correlation analysis. AMOS 24.0 was employed for confirmatory factor analysis to assess measurement validity. For hypothesis testing, we utilized Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 59) in SPSS to conduct conditional process analysis examining both mediation and moderation effects simultaneously.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

To assess the reliability of our measurement results, we first conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using SPSS 26.0 to examine the factor structure. The EFA confirmed our expected four-factor solution, with each item loading primarily on its intended construct. Subsequently, we performed reliability analyses in SPSS to obtain Cronbach’s α values for each construct. We then conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 24.0 to obtain factor loadings and assess model fit. The factor loadings reported represent the range (minimum to maximum) of standardized loadings for each construct’s items in the final measurement model.

Prior to conducting factor analysis, we assessed data suitability through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. The KMO value was 0.942, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.6, and Bartlett’s Test yielded significant results (χ2 = 6013.466, df = 496, p < 0.001), confirming that our data were appropriate for factor analysis.

To assess the reliability and validity of our measurement results, we conducted comprehensive analyses for the four key variables: Resource Bricolage (RB), Digital Transformation (DT), Business Model Innovation (BMI), and Entrepreneurship (ES). As shown in Table 2, all constructs demonstrated excellent reliability with Cronbach’s α values ranging from 0.912 to 0.940 and composite reliability (CR) values between 0.914 and 0.941, well above the recommended threshold of 0.7. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs exceeded the 0.5 threshold (ranging from 0.583 to 0.666), and factor loadings were all above or approaching 0.7 (ranging from 0.695 to 0.871), indicating strong convergent validity and high internal consistency of the measurement scales.

Table 2.

Reliability and Validity Assessment.

We assessed discriminant validity using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio analysis, as presented in Table 3 and Table 4. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was satisfied as the square root of each construct’s AVE (diagonal elements in Table 3) exceeded its correlation with other constructs. Additionally, all HTMT ratios were well below the conservative threshold of 0.85, with values ranging from 0.271 to 0.654, providing further evidence of good discriminant validity between all construct pairs.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion for Discriminant Validity.

Table 4.

HTMT Analysis.

To examine potential common method bias, we implemented both procedural and statistical remedies. Following [74], we employed Harman’s single-factor test, which revealed that the first factor explained 36.115% of the variance, substantially below the 40% threshold. This indicates that common method bias is not a significant concern in our study.

As shown in Table 5, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS to further assess the distinctiveness of our constructs. We compared four different measurement models: a one-factor model combining all constructs, two alternative nested models (two-factor and three-factor), and our hypothesized four-factor model. The four-factor model demonstrated excellent fit indices: χ2/df = 1.362, RMSEA = 0.037, SRMR = 0.048, CFI = 0.972, NFI = 0.901, TLI = 0.969, IFI = 0.972, and NNFI = 0.969. These indicators were all within recommended ranges and substantially superior to those of alternative models, confirming both the construct validity of our measurement scales and good discriminant validity among the four variables.

Table 5.

Overall fit indices of the measurement model.

The one-factor model (χ2/df = 7.385, RMSEA = 0.156, SRMR = 0.163, CFI = 0.491) showed poor fit, as did the two-factor model (χ2/df = 5.868, RMSEA = 0.136, SRMR = 0.166, CFI = 0.613). The three-factor model showed improved but still inadequate fit (χ2/df = 3.162, RMSEA = 0.091, SRMR = 0.112, CFI = 0.829). The significant improvement in fit indices from the one-factor model to our hypothesized four-factor model provides additional evidence against common method bias and supports the distinctiveness of our constructs.

To address potential concerns about multicollinearity among predictor variables, we conducted variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis and tolerance tests. All VIF values were well below the conservative threshold of 5, ranging from 1.106 to 1.261, and all tolerance values exceeded 0.7 (ranging from 0.793 to 0.904), substantially above the critical threshold of 0.1. These results indicate that multicollinearity is not a significant concern in our model.

Additionally, our regression model demonstrated good fit (F(3,259) = 64.002, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.426, Adjusted R2 = 0.419) with a Durbin–Watson statistic of 2.114, close to the ideal value of 2, suggesting no significant autocorrelation in the residuals. These diagnostic statistics, combined with our previous confirmatory factor analyses comparing alternative model specifications, provide robust evidence for the reliability and validity of our measurement model and analytical approach.

4.2. Hypotheses Test

Table 6 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for all variables in this study. As shown in Table 6, Resource Bricolage (RB) demonstrates significant positive correlations with both Digital Transformation (DT) (r = 0.418, p < 0.001) and Business Model Innovation (BMI) (r = 0.464, p < 0.001). Additionally, Digital Transformation exhibits a significant positive correlation with Business Model Innovation (r = 0.602, p < 0.001). Entrepreneurship (ES) is positively correlated with Resource Bricolage (r = 0.275, p < 0.001), Digital Transformation (r = 0.243, p < 0.001), and Business Model Innovation (r = 0.278, p < 0.001). These preliminary results provide initial support for several of our hypotheses and suggest that proceeding with further hypothesis testing is warranted.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics and correlations (N = 263).

Among the control variables, only firm age shows a significant negative correlation with Resource Bricolage (r = −0.134, p < 0.05), suggesting that younger firms may engage in more resource bricolage behaviors. Neither the number of employees nor industries demonstrates significant relationships with our key variables of interest.

The correlation matrix indicates significant positive associations among our key variables, providing preliminary support for the proposed relationships in our theoretical framework. Notably, the moderate correlations (ranging from 0.243 to 0.602) among the main constructs suggest meaningful relationships while still confirming their distinctiveness, which aligns with the discriminant validity established in our confirmatory factor analysis. These preliminary results justify proceeding with more sophisticated analytical techniques to test our mediation and moderation hypotheses.

4.2.1. Mediation Effect

According to our research model framework, we conducted conditional process analysis to verify mediation and moderation effects [75]. We used the SPSS macro PROCESS to examine the mediating role of digital transformation and the moderating effect of entrepreneurship in the relationship between resource bricolage and business model innovation, employing the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method to test multiple mediation and moderation models.

We examined three regression models to establish the mediation pathway:

As shown in Table 7, Model 1 reveals that RB significantly and positively influences BMI (β = 0.470, t = 8.433, p < 0.001), providing support for H1.

Table 7.

The test result of the Digital Transformation mediation effect.

Model 2 demonstrates that RB significantly predicts DT (β = 0.423, t = 7.449, p < 0.001), supporting H2. In Model 3, we find that DT significantly predicts BMI (β = 0.499, t = 9.449, p < 0.001), while the direct effect of RB on BMI remains significant but diminished (β = 0.259, t = 4.888, p < 0.001). This supports H3 and indicates a partial mediation effect. The inclusion of DT increases the explained variance in BMI from 21.7% to 41.9%.

Further bootstrap analysis confirms a significant indirect effect of RB on BMI through DT (0.211, 95% Boot CI = [0.146, 0.281]), accounting for 44.853% of the total effect. The direct effect remains significant (0.259, 95% Boot CI = [0.155, 0.363]), representing 55.147% of the total effect. These findings support H4, demonstrating that Digital Transformation partially mediates the relationship between resource bricolage and business model innovation.

4.2.2. A Moderated Mediation Model

Building upon our mediation analysis, we further examined the moderating role of Entrepreneurship throughout the entire mediation process using PROCESS Model 59 [76]. Hypotheses H5a, H5b, and H5c proposed that Entrepreneurship would moderate the relationships between RB and DT, DT and BMI, and RB and BMI, respectively. As shown in Table 8, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis by sequentially incorporating control variables, independent variables, mediating variables, and moderating variables.

Table 8.

The test result of A Moderated Mediation Model (ES as a moderator).

The results indicate that RB positively predicts DT (β = 0.450, p < 0.001), and this relationship is significantly moderated by ES (β = 0.350, p < 0.001), supporting H5a. Regarding H5b, DT positively influences BMI (β = 0.338, p < 0.001), and this relationship is significantly moderated by Entrepreneurship (β = 0.189, p < 0.001). This confirms our hypothesis that ES strengthens the impact of DT on BMI.

For H5c, RB positively affects BMI (β = 0.252, p < 0.001), and this direct relationship is also significantly moderated by Entrepreneurship (β = 0.226, p < 0.001). This finding supports our hypothesis that entrepreneurship enhances the direct effect of resource bricolage on business model innovation. The overall model demonstrates R2 = 0.567 for BMI and R2 = 0.372 for DT.

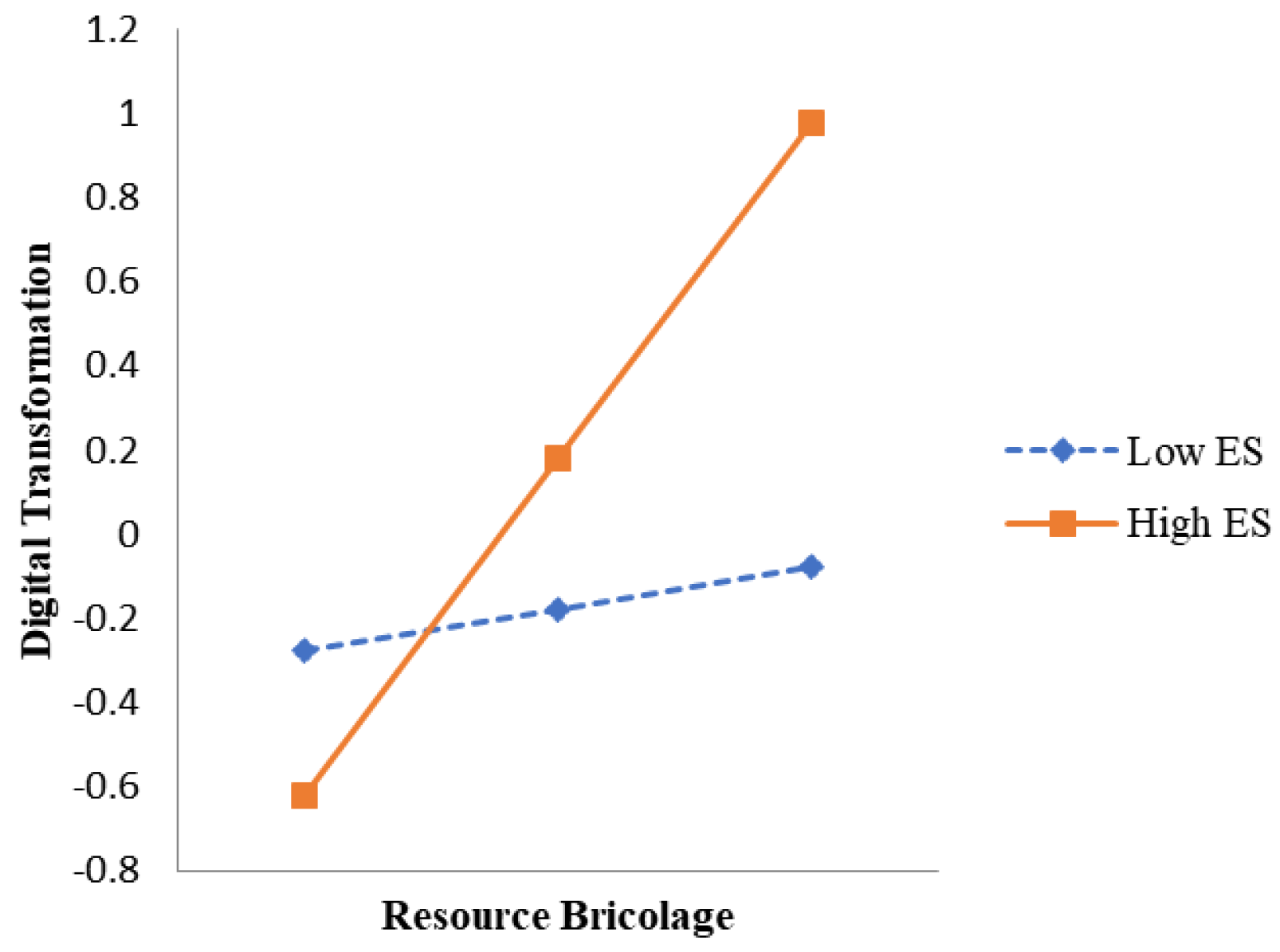

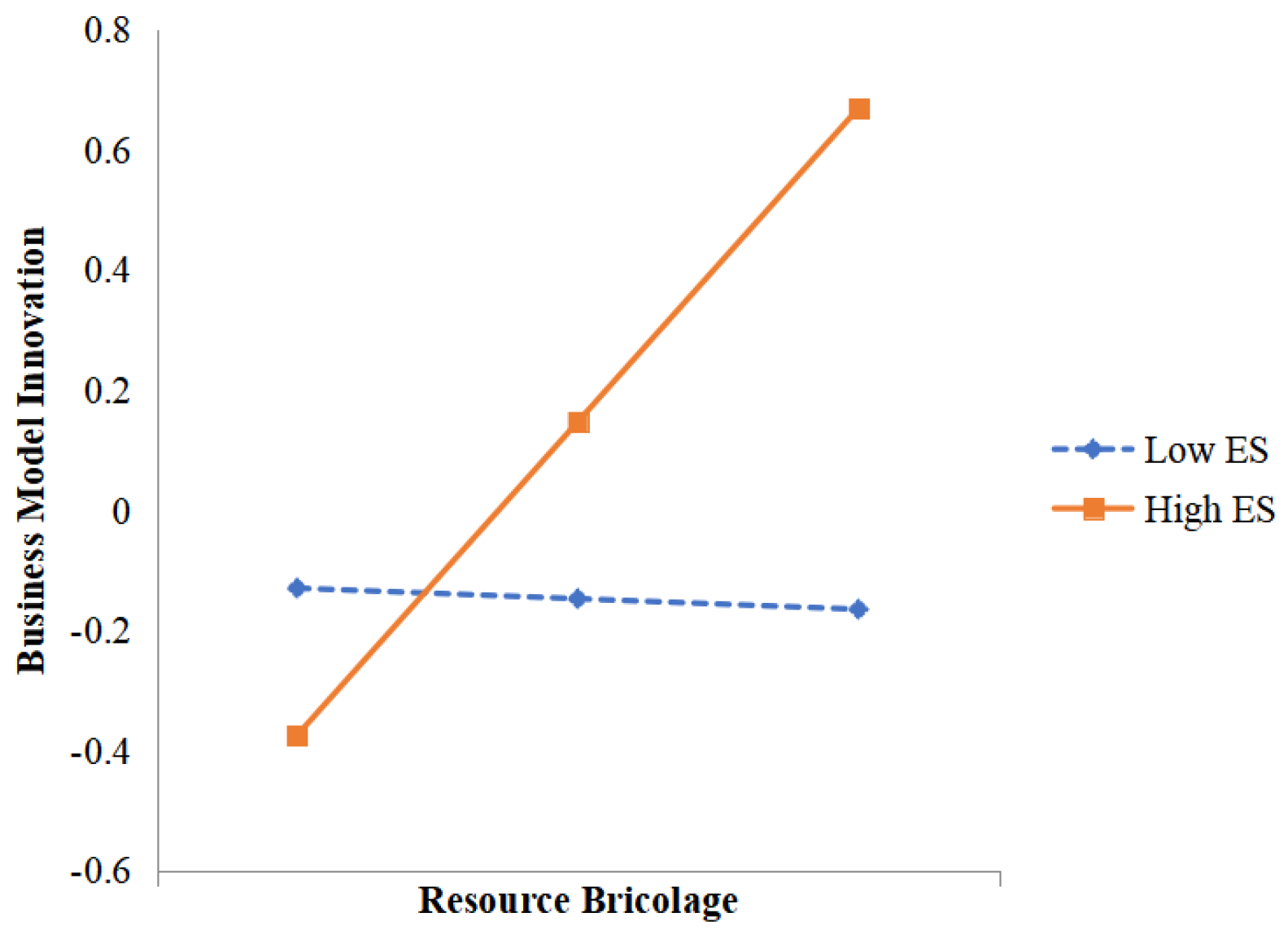

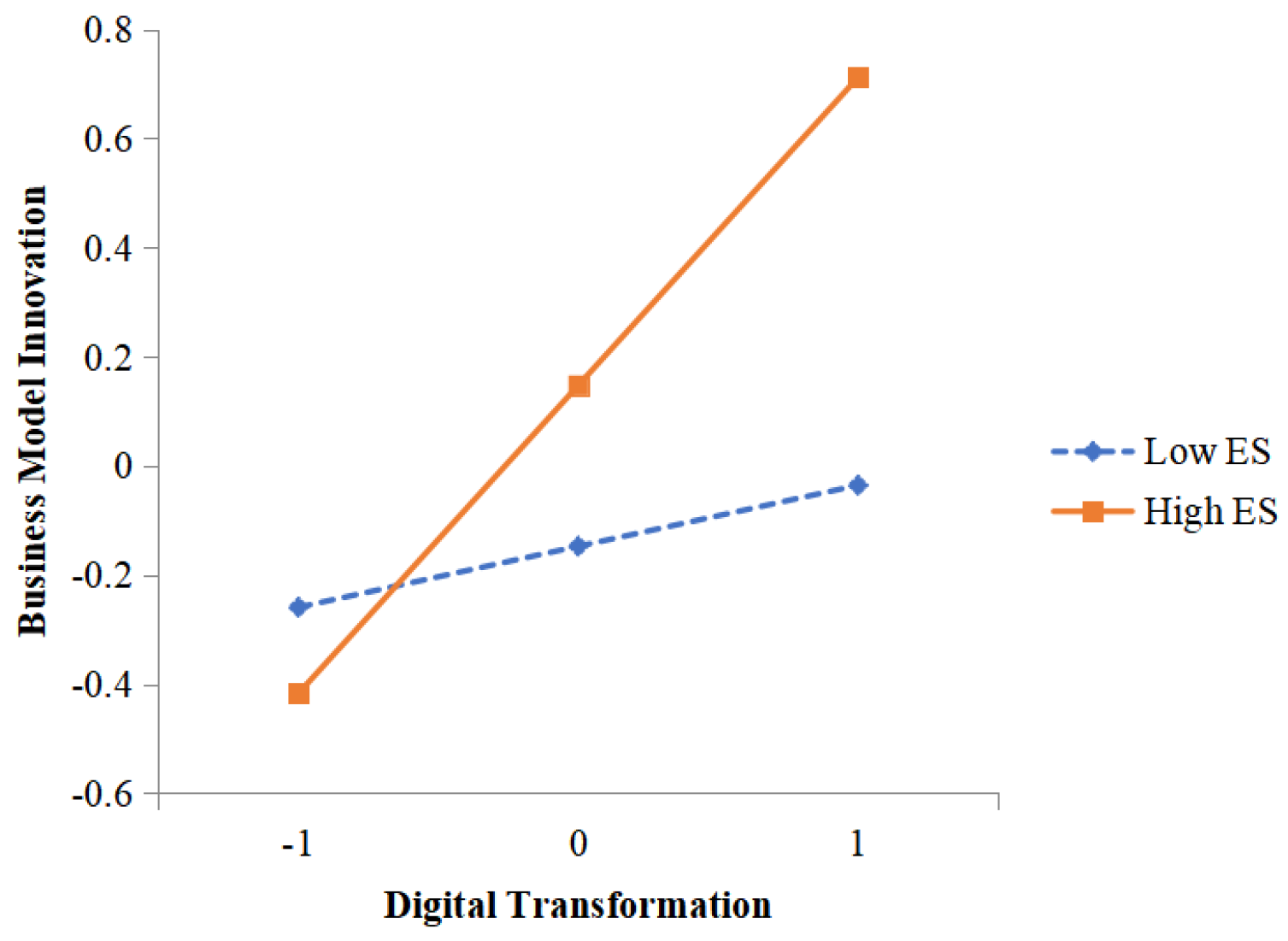

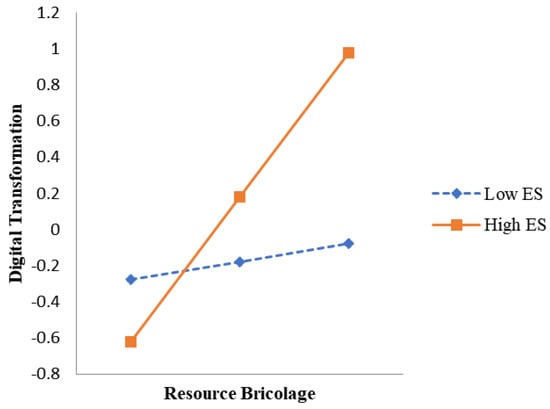

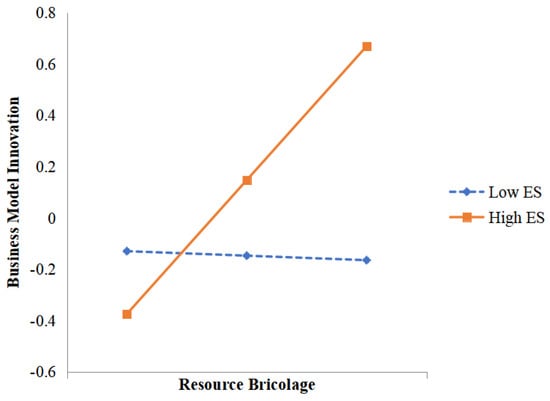

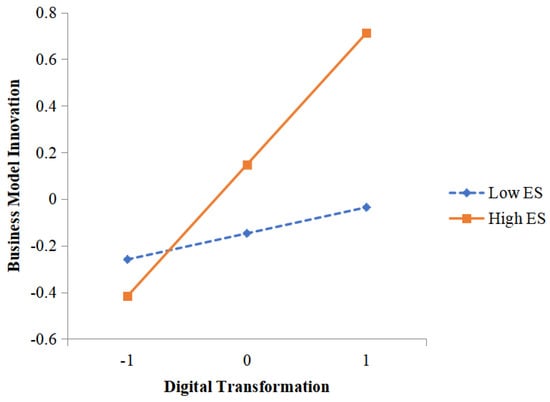

To further examine these interaction effects, we conducted simple slope analyses at different levels of Entrepreneurship: low (1 SD below the mean), mean, and high (1 SD above the mean). As shown in Figure 2, the effect of RB on DT was significant in the high ES condition (β = 0.886, p < 0.001) but non-significant in the low ES condition (β = 0.014, p > 0.05). Figure 3 shows that the effect of RB on BMI was significant in the high ES condition (β = 0.535, p < 0.001) but non-significant in the low ES condition (β = −0.030, p > 0.05). Similarly, Figure 4 demonstrates that the effect of DT on BMI was significant in the high ES condition (β = 0.574, p < 0.001) but non-significant in the low ES condition (β = 0.102, p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

ES moderates the RB—DT relationship.

Figure 3.

ES moderates the RB—BMI relationship.

Figure 4.

ES moderates the DT—BMI relationship.

While our control variables (firm size, age, and industry) did not show significant effects, this suggests the universality of these relationships across different organizational contexts, underscoring the strategic importance of this dual capability development approach for firms seeking business model innovation.

As shown in Table 9 and Table 10, the conditional process analysis results demonstrate the moderating effect of Entrepreneurship. Table 9 presents the conditional direct effects of resource bricolage on business model innovation (RB—BMI); Table 10 presents the conditional indirect effects through digital transformation (RB—DT—BMI). The results indicate that at low levels of Entrepreneurship (-1SD), both the direct effect (−0.030, p > 0.05) and the indirect effect (0.001, 95% CI [−0.021, 0.023]) were non-significant. At high levels of entrepreneurship (+1SD), both the direct effect (0.535, p < 0.001) and the indirect effect (0.509, 95% CI [0.364, 0.681]) were significant. The significant moderation effects observed at both the direct and indirect paths, combined with the pronounced differences in effect sizes between low and high entrepreneurship conditions, provide support for H5d, confirming the moderated mediation hypothesis.

Table 9.

Conditional Direct Effect of Resource Bricolage on Business Model Innovation.

Table 10.

Conditional Indirect Effect of Resource Bricolage on Business Model Innovation through Digital Transformation.

5. Discussion

This study examines how resource bricolage influences business model innovation, with digital transformation as a mediating variable and entrepreneurship as a moderating variable. Through a quantitative analysis of 263 valid survey responses from entrepreneurs and employing conditional process analysis via Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 59), our research yields several significant empirical findings that contribute to the extant literature. Empirical evidence provides substantial support for our theoretical framework, thereby addressing critical gaps in the existing body of knowledge while extending theory in the domains of resource bricolage, digital transformation, and business model innovation. The following discussion systematically examines each hypothesis, reflects on its theoretical implications, and develops research propositions that advance scholarly understanding of entrepreneurial resource utilization in contemporary business environments.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, resource bricolage positively facilitates business model innovation. Business model innovation may involve either creating entirely new products and services or improving existing ones, but both approaches require resource support. Resource bricolage, as a dynamic capability, enables firms to creatively reconfigure and recombine existing resources, activating idle or overlooked assets while improving resource utilization efficiency. When managers break existing resource utilization patterns and engage in resource bricolage, they can approach existing resources from new perspectives, activate idle or abandoned resources, and improve resource utilization efficiency. Firms that systematically develop resource bricolage capabilities can overcome resource constraints to achieve business model innovation by (a) reconfiguring existing resource combinations, (b) activating previously overlooked resources, and (c) improving resource utilization efficiency across organizational boundaries.

The scope of resources involved in business model innovation encompasses the entire process, including both abstract organizational resources and operational resources. The abstract organizational resources include knowledge, networks, and routines. This comprehensive view underscores the versatility of resource bricolage in supporting both incremental and radical innovation in business models. By systematically developing bricolage capabilities, firms can achieve a broader reconfiguration of their resource portfolios, allowing them to adapt to changing market demands and seize new opportunities for innovation. These findings provide empirical evidence for the theoretical assertion that firms adept at recombining existing resources in novel ways are better positioned to innovate their business models, particularly in contexts characterized by resource limitations or uncertainty.

The integration of resource bricolage with the RBV offers a significant theoretical contribution. The RBV posits that competitive advantage arises from the possession and effective deployment of valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources [77]. Specifically, resource bricolage enables firms to activate overlooked resources, improve efficiency across organizational processes, and reconfigure existing resource combinations to address evolving challenges. These findings position resource bricolage not merely as a coping mechanism for resource scarcity but as a proactive and strategic capability that aligns with the RBV framework [39]. By leveraging both tangible and intangible resources, firms can innovate their business models and sustain competitive advantages, thus providing robust support for the hypothesis.

Second, digital transformation mediates the relationship between resource bricolage and business model innovation.

Digital transformation represents a critical pathway through which resource bricolage contributes to innovative business models. However, digital transformation is not instantaneously achieved but requires institutional, cultural, and resource support. Senior executives, such as CDOs, need to employ resource bricolage to gather resources from all departments for new digital initiatives while integrating these initiatives with existing organizational functions [19]. This process not only optimizes resource utilization but also provides the institutional and cultural foundations necessary to sustain digital transformation in dynamic environments.

The digital transformation itself exerts a dual effect on business model innovation. On the one hand, it restructures corporate processes by streamlining operations, enhancing efficiency, and fostering the development of unique organizational capabilities. On the other hand, it enables firms to reimagine customer engagement and value delivery by integrating and simplifying channels to reach customer segments while tailoring offerings to meet emerging demands. These transformations allow firms to achieve the dual goals of increasing revenue and reducing costs, thereby driving innovative business models.

The research, conducted in the context of China, provides a unique perspective on how firms leverage resource bricolage to achieve digital transformation and, subsequently, innovate their business models. In China, the rapid pace of technological advancement, coupled with government-led digital initiatives such as “Made in China 2025”, has accelerated the adoption of digital transformation across industries. However, this rapid development also brings unique challenges that influence the effectiveness of digital transformation efforts and their impact on business model innovation. The competitive pressures of China’s fast-evolving market amplify these challenges. Many firms adopt digital transformation as a survival strategy, driven by the need to keep pace with rapidly changing consumer demands and technological trends. However, this reactive approach often leads to fragmented or short-term digital initiatives that fail to deliver long-term strategic value [62]. These challenges highlight the importance of resource bricolage as a strategic capability. By creatively mobilizing and reconfiguring resources, firms can overcome these constraints, bridge capability gaps, and develop a cohesive digital transformation strategy that supports sustainable innovation.

Digital transformation’s dual role as a mediator and a direct driver of business model innovation underscores its importance as a dynamic and evolving process. It requires a delicate balance between leveraging existing organizational strengths and embracing disruptive change [78]. From a practical perspective, this indicates that firms pursuing business model innovation should develop capabilities in both domains rather than viewing digital transformation as a substitute for fundamental resource recombination skills. By integrating resource bricolage with digital transformation, firms can align their innovation strategies with the demands of a rapidly evolving economic environment, ultimately achieving sustained competitive advantage.

Third, entrepreneurship significantly moderates these relationships, which represents one of our key theoretical contributions. Specifically, entrepreneurship strengthens the direct effect of resource bricolage on business model innovation, as well as its indirect effect through digital transformation. Similarly, the positive influence of resource bricolage on digital transformation and the influence of digital transformation on business model innovation are both amplified by high levels of entrepreneurship. This moderating effect underscores the importance of entrepreneurial orientation in enabling firms to navigate uncertainty, leverage resources effectively, and drive innovation.

Any organizational decision-making and implementation process tests entrepreneurial spirit. Entrepreneurs must engage in structured thinking in highly uncertain and risky environments, conduct resource bricolage, make quick decisions, and ultimately drive product and service innovation and market entry [66]. Managers with high entrepreneurial orientation clarify organizational vision and can leverage their abilities and resources to help firms overcome resource constraints and path dependencies. When facing limitations, they seek business model innovation directions, break through internal cultural and institutional constraints, form competitive advantages through resource bricolage actions, leverage digital transformation opportunities to achieve innovation and realize business model and process innovations. In contrast, managers with low entrepreneurial orientation may hinder these processes, failing to promote strategic changes and innovation or even disrupting business model innovation through ineffective resource allocation and integration.

The moderating role of entrepreneurship is particularly salient in the context of Chinese enterprises, where cultural and institutional characteristics influence resource integration, digital transformation, and innovation processes. First, China’s collectivist culture and hierarchical organizational structures create a unique environment where entrepreneurial leaders are more likely to inspire cooperation and support for resource reallocation. In state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and firms with policy backgrounds, entrepreneurial leadership can facilitate resource integration and digital transformation over time [78]. These types of firms often occupy key resources and enjoy access to government subsidies and policy support, which further enhances their ability to innovate.

Second, influenced by pragmatism, Chinese entrepreneurs tend to seize opportunities presented by digital transformation and resource abundance. The rapid digitalization of the Chinese economy presents a significant opportunity for entrepreneurial managers to capitalize on emerging technologies, integrate resources, and drive business model innovation. In this context, the role of entrepreneurship is amplified, as no pragmatic entrepreneur would overlook the potential benefits of leveraging digital transformation for competitive advantage.

Third, Chinese culture’s gradual approach to change highlights the necessity of strong entrepreneurial leadership to foster disruptive business model innovations. Without entrepreneurial managers to challenge entrenched routines and drive strategic change, firms are unlikely to achieve the level of resource integration and digital transformation required to support radical innovation. As evidenced in the moderating effect diagrams, firms with high levels of entrepreneurial orientation exhibit a more pronounced amplification mechanism, demonstrating that entrepreneurship is vital for translating resource bricolage and digital transformation into business model innovations.

5.2. Practical Implications

For both startups and established companies, pursuing business model innovation represents a critical pathway for corporate expansion, technological advancement, and wealth creation. Having recognized the importance of high-level entrepreneurship, organizations must consider how to maximize its effects. Business model innovation and digital transformation require an environment that actively fosters innovation through company-wide efforts. Organizations need to select experienced and capable managers, such as CDOs, to drive organizational change and innovation while providing ongoing support to these leaders. These managers must be provided with the necessary resources and authority to execute strategies effectively. These selected managers are not expected to personally engage in digital technology implementation but rather to drive corporate transformation and innovation through their leadership qualities. By fostering a culture of innovation and implementing strategic management choices, organizations can establish a solid foundation for entrepreneurship and innovation, aligning themselves with the ever-changing modern business environment. We are not suggesting that companies must introduce managers with special titles but rather recommending that organizations recognize the importance of entrepreneurship, formulate corresponding strategies, and leverage resources and technology to achieve innovation objectives.

The entrepreneurial spirit is no longer exclusively characteristic of entrepreneurs or managers. Organizations must emphasize the importance of employees as they operate on the front lines of resource utilization and innovation. This includes offering training programs to enhance employees’ technical capabilities and creativity. Companies need to cultivate employee skills and innovative mindsets that align with organizational resources and the pace of business model innovation. Managers should lead employees in collaborative efforts to implement entrepreneurial spirit throughout the organization, explore innovation opportunities, and fully leverage policy support, affordable resources, and social capital to better implement resource bricolage, complete digital transformation, and achieve business model innovation. Organizations should also create continuous learning platforms where employees can share knowledge and collaborate on innovation projects.

A key step in effectively utilizing resource integration is conducting comprehensive audits and strategically aligning tangible and intangible resources. This includes physical assets, financial resources, and the intellectual capital of leaders and employees. Leaders with strategic vision and decision-making capabilities are critical resources for driving successful innovation. Similarly, employees’ tacit knowledge, creativity, and willingness to engage in innovation practices are invaluable assets. Organizations should regularly conduct resource audits to identify and organize these resources, understanding their strengths and limitations. By effectively integrating these resources, companies can create synergies that enhance their digital transformation and business model innovation capabilities. This requires careful planning and execution to ensure optimal resource utilization and avoid inefficiencies or waste.

Organizations need to reasonably select entrepreneurial activities based on their resource endowments, a principle earlier scholars have articulated [26]. Digital transformation’s potential to change markets is often more extensive than standalone product innovation, as it reshapes and disrupts business processes, sales channels, supply chains, and entire business models. Against this backdrop, organizations need to embrace this transformation approach, leveraging digital transformation to empower continuous competitive capability.

In this process, companies can either develop digital technologies through their own efforts or consider relying on established third-party platforms [79]. These platforms offer numerous mature case studies and experiences, understand market rules intimately, and often serve as market rule-makers themselves. Organizations, especially SMEs, can pay corresponding fees to rely on these platforms to access external resources and digital technologies aligned with their specific circumstances, thereby achieving business model innovation. Looking ahead to 2025, the adoption of open-source models presents significant opportunities. These models provide companies with access to cutting-edge technologies and collaborative platforms that accelerate digital transformation. Additionally, these models facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration across organizational boundaries, creating a rich ecosystem for innovation.

Sustained entrepreneurship requires not only internal efforts but also external support, particularly from government policies [80]. Companies should actively seek and apply for national and local projects that support innovation and entrepreneurship. These programs often provide financial subsidies, tax incentives, and access to professional resources, which can significantly enhance entrepreneurial activities. When companies achieve significant results through these programs, they should also share their experiences and best practices with the broader community. This not only enhances the company’s reputation but also contributes to the overall advancement of the industry. By leveraging policy support and external resources, companies can create a sustainable entrepreneurial environment, driving long-term growth and competitiveness.

Finally, policymakers can play a vital role in fostering entrepreneurship and digital transformation by promoting digital infrastructure development, providing technical support, and offering training programs. These efforts can help entrepreneurs better utilize digital technologies and enhance their entrepreneurial activities, ultimately contributing to broader economic and technological advancement.

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

First, the underlying mechanism we explored is complex and represents just one perspective on business model innovation. Future research could investigate additional antecedents of business model innovation from different theoretical perspectives, including institutional theory, dynamic capabilities view, or network theory. Scholars might also explore alternative influence paths for the variables selected in this study, such as examining whether entrepreneurship might serve as a mediator rather than a moderator in different contexts.

Second, our sampling approach targeted entrepreneurs involved in digital transformation and business model innovation without strictly limiting participants by region or industry sector. This potentially introduces heterogeneity that may obscure industry-specific or regional effects. Future research could narrow the sample characteristics to specific industries or geographical contexts to produce more targeted conclusions with stronger contextual validity.

Third, our cross-sectional design limits causal inferences about the relationships observed. Longitudinal studies could provide stronger evidence regarding the temporal sequence of resource bricolage, digital transformation, and business model innovation, particularly as digital transformation typically unfolds over extended periods. Case studies or mixed-method approaches might also yield richer insights into how these processes evolve over time.

Fourth, our measurement approach relied on self-reported data from entrepreneurs, which may introduce common method bias despite our procedural remedies. Future studies might triangulate findings using objective performance metrics or multi-source data, including perspectives from different organizational stakeholders.

Fifth, our study conducted a survey focused exclusively on Chinese enterprises. While the theoretical framework proposed in this research has potential applicability across global business contexts, future research should undertake cross-cultural and cross-regional comparative studies to provide more comprehensive data. Such international comparisons would test the generalizability of our findings and potentially identify cultural or institutional contingencies affecting the relationships among resource bricolage, digital transformation, and business model innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W., Z.Z. and D.C.; Methodology, Z.Z. and D.C.; Software, X.W. and Z.Z.; Formal analysis, X.W. and Z.Z.; Investigation, X.W.; Resources, D.C.; Writing—original draft, X.W. and Z.Z.; Writing—review & editing, D.C.; Supervision, D.C.; Project administration, D.C.; Funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hulunbuir University Doctoral Fund, grant number 2024BSJJ10. The APC was funded by the same fund.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velu, C. Business Model Innovation and Third-Party Alliance on the Survival of New Firms. Technovation 2015, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Naqshbandi, M.M.; Farooq, R. Business Model Innovation: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2020, 12, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øiestad, S.; Bugge, M.M. Digitisation of Publishing: Exploration Based on Existing Business Models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 83, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezger, F. Toward a Capability-Based Conceptualization of Business Model Innovation: Insights from an Explorative Study. RD Manag. 2014, 44, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go? J. Manag. 2016, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Busenitz, L.W. The Entrepreneurship of Resource-Based Theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Making That Which Is Old New Again: Entrepreneurial Bricolage. In Babson Kauffman Entrepreneurship Research Conference (BKERC); Babson College: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Wiesböck, F. Options for Formulating a Digital Transformation Strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Tian, Z. Environmental Uncertainty, Resource Orchestration and Digital Transformation: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodor, S.; Aránega, A.Y.; Ramadani, V. Impact of Digitalization and Innovation in Women’s Entrepreneurial Orientation on Sustainable Start-up Intention. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B.; Hisrich, R.D. Intrapreneurship: Construct Refinement and Cross-Cultural Validation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 495–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Verbeke, A.; Yuan, W. CEO Transformational Leadership and Corporate Entrepreneurship in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2021, 17, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Klarner, P.; Hess, T. How Do Chief Digital Officers Pursue Digital Transformation Activities? The Role of Organization Design Parameters. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Hess, T. How Chief Digital Officers Promote the Digital Transformation of Their Companies. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tumbas, S.; Berente, N.; Brocke, J.V. Digital Innovation and Institutional Entrepreneurship: Chief Digital Officer Perspectives of Their Emerging Role. J. Inf. Technol. Inf. Technol. 2018, 33, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Leading Digital Transformation: Three Emerging Approaches for Managing the Transition. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation: An Ongoing Process of Strategic Renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, X.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, D. The Emergence of Organization Entrepreneurship in the Digital Age: Grounded Theory Analysis Based on Multiple Cases. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2021, 38, 92–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Baker, T.; Senyard, J.M. A Measure of Entrepreneurial Bricolage Behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyard, J.; Baker, T.; Steffens, P.; Davidsson, P. Bricolage as a Path to Innovativeness for Resource-Constrained New Firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Vale, G.; Collin-Lachaud, I.; Lecocq, X. Micro-Level Practices of Bricolage during Business Model Innovation Process: The Case of Digital Transformation towards Omni-Channel Retailing. Scand. J. Manag. 2021, 37, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Entrepreneurial Bricolage, Business Model Innovation, and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Performance of Digital Entrepreneurial Ventures: The Moderating Effect of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Empowerment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Palmer, C.; Kailer, N.; Kallinger, F.L.; Spitzer, J. Digital Entrepreneurship: A Research Agenda on New Business Models for the Twenty-First Century. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 25, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witell, L.; Gebauer, H.; Jaakkola, E.; Hammedi, W.; Patricio, L.; Perks, H. A Bricolage Perspective on Service Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, C.; Karna, A.; Sailer, M. Business Model Adaptation for Emerging Markets: A Case Study of a German Automobile Manufacturer in India. RD Manag. 2016, 46, 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 0-470-87641-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barquet, A.P.B.; de Oliveira, M.G.; Amigo, C.R.; Cunha, V.P.; Rozenfeld, H. Employing the Business Model Concept to Support the Adoption of Product–Service Systems (PSS). Ind. Mark. Manag. Models—Explor. Value Driv. Role Mark. 2013, 42, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Miner, A.S.; Eesley, D.T. Improvising Firms: Bricolage, Account Giving and Improvisational Competencies in the Founding Process. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T. Resources in Play: Bricolage in the Toy Store(y). J. Bus. Ventur. Narrat. 2007, 22, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Xie, S. A Review of Studies of Value Creation of Entrepreneurial Resources from a Bricolage Perspective and Future Prospects. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2013, 35, 14–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, L.; Li, Q. Business Model Innovation of Servitization of the Manufacturing Industry:A Resource-Based Perspective. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 40, 74–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Sha, Z.; Sun, R. Market Orientation, Resource Bricolage and Business Model Innovation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 40, 113–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Chun, D. The Effect of Knowledge Sharing on Ambidextrous Innovation: Triadic Intellectual Capital as a Mediator. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ming, H.; Pang, D. The Study on the Inhibition and Its Immune Mechanism of Path Dependence on the Corporate Digital Entrepreneurship. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2022, 39, 91–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella, C.; Biotto, G.; De Toni, A.F. From Design Driven Innovation to Meaning Strategy. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 718–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Su, Z.; Ahlstrom, D. Business Model Innovation: The Effects of Exploratory Orientation, Opportunity Recognition, and Entrepreneurial Bricolage in an Emerging Economy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.M.; Campbell, B.A. Inventor Bricolage and Firm Technology Research and Development. RD Manag. 2009, 39, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G. Effectuation, Causation, and Bricolage: A Behavioral Comparison of Emerging Theories in Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1019–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Zhao, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. How Bricolage Drives Corporate Entrepreneurship: The Roles of Opportunity Identification and Learning Orientation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 35, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. Rev. Issue 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Qi Dong, J.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G. The Technology Fallacy: How People Are the Real Key to Digital Transformation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2019, 62, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.; Demi, S.; Magrini, A.; Marzi, G.; Papa, A. Exploring the Impact of Big Data Analytics Capabilities on Business Model Innovation: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]