1. Introduction

The circular economy (CE) is increasingly recognized as a strategic framework for sustainable business, yet limited research has examined how its operationalization, particularly through circular economy practices (CEPs) and procurement strategies (PS), influences organizational competitiveness (OC) [

1] CEPs aim to minimize waste and maximize resource efficiency through activities such as recycling, reuse, and redesign [

2,

3]. In parallel, procurement strategies, which govern how organizations source, select, and manage resources, are critical to achieving long-term competitive advantage [

4]. Although these two domains are individually well-studied, their combined impact on competitiveness and the organizational conditions that enable this relationship remain underexplored.

Understanding how organizations can integrate CEPs and PS to enhance OC is increasingly important in light of growing resource constraints and regulatory pressures. Yet, current research often overlooks the mediating and moderating mechanisms that shape these relationships. This study considers several contextual factors, such as organizational culture (OCL) [

5], stakeholder pressure (SP) [

6], resource availability (RA) [

7], innovation (IN) [

8], and industry characteristics (ICs) [

9], all of which can influence how CEPs and PS contribute to OC. These variables, although acknowledged in prior literature, have not been broadly examined within a unified framework.

This paper takes a theory-informed, exploratory approach with the aim of investigating perceived interrelations between CEPs, PS, and OC, along with the contextual factors that may mediate or moderate these relationships. The study focuses on the perceptions of management students, who, though not yet active executives, represent future decision-makers and bring informed, forward-looking perspectives. Their insights reflect emerging managerial values shaped by sustainability education, making them a relevant population for an early-stage exploration of strategic sustainability mindsets [

10].

Specifically, the paper investigates whether PS can moderate or mediate the relationship between CEPs and OC. It is hypothesized that organizations that adopt strategic procurement approaches can more effectively leverage CEPs to achieve competitive advantage. It is also proposed that PS act as a mediating channel through which CEPs affect competitiveness. Furthermore, it is examined how OC, SP, RA, IN, and ICs interact with these core relationships.

Overall, this study contributes to the relatively underexplored intersection of circular economy and procurement by providing a conceptual foundation and an empirically grounded, exploratory analysis of their combined influence on organizational competitiveness. By examining how future managers perceive the strategic roles of circular economy practices and procurement strategies, the research sheds light on how various organizational and environmental factors may shape these dynamics. In doing so, the study offers both theoretical groundwork and practical insights for organizations aiming to embed sustainability more effectively into their strategic agendas.

The structure of the paper is as follows. We begin with a literature review, synthesizing current knowledge on CEPs, PS, OC, and the contextual variables included in our model. The paper then presents the conceptual framework and research hypotheses, followed by the Methodology section detailing the sample, data collection procedures, and analytical techniques. The Results section outlines the empirical findings, including tests of moderation and mediation. In the Discussion, these findings are interpreted, and their theoretical and managerial significance is reflected on. Finally, the paper ends with concluding implications for practice and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Given the number of interrelated constructs and hypotheses explored, this section is structured into focused subsections aligned with each theoretical variable and proposed relationship.

2.1. Circular Economy Practices

CEPs refer to the degree to which organizations adopt strategies aimed at minimizing waste and resource depletion by maximizing resource efficiency, reducing emissions, and promoting sustainable production and consumption [

11]. These kinds of practices align with a circular economic model that prioritizes value retention through activities such as recycling, reuse, remanufacturing, and the development of closed-loop supply chains.

A growing body of literature highlights the benefits of CEPs for organizational performance, particularly in terms of environmental sustainability, cost savings, and innovation [

12,

13,

14]. Through reducing waste and optimizing resource use, organizations can not only lower operational costs, but also improve strategic flexibility and resilience [

15,

16]. Importantly, the adoption of CEPs aligns with rising consumer demand for environmentally responsible products and services, providing new market opportunities and reinforcing brand value [

17].

Empirical studies reinforce this positive link between CEPs and OC. For instance, Korhonen et al. [

18] found that circular economy practices contribute to improved resource efficiency and reduced costs while enhancing brand reputation. Boons and Lüdeke-Freund [

19] observed that CEPs can open up new market segments, increase customer loyalty, and foster innovation. Similarly, Rizos et al. [

20] reported that firms leveraging CEPs tend to reduce their reliance on scarce resources and improve environmental performance, ultimately strengthening their competitive positioning.

Taken together, the literature suggests that CEPs contribute to OC by driving efficiency, fostering innovation, developing new markets, and enhancing sustainability performance [

21]. Based on these insights, we hypothesized as follows:

H1. Circular economy practices have a positive impact on organizational competitiveness.

2.2. Procurement Strategies

PS refers to the strategic approach organizations use to source, select, negotiate, and manage suppliers and contracts to achieve performance and competitiveness goals. Common approaches include strategic sourcing, supplier collaboration, and supply chain risk management. Research consistently highlights that PS can play an engaging role in enhancing competitiveness by reducing costs, fostering innovation, and strengthening supplier relationships [

1,

22].

While this study focuses on organizational procurement strategies in a general context, it is important to distinguish circular procurement in the private sector from circular public procurement (CPP), which has gained significant momentum in recent years, particularly within the European Union. CPP refers to the integration of circular economy principles into public purchasing decisions, often supported by policy frameworks such as the EU Green Deal and regulatory instruments such as ISO 14001 or Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Notable efforts in this domain include the CE PRINCE project and the European Commission’s CPP guidelines, which emphasize standardization, traceability, and sustainability throughout the supply chain [

23,

24]. While CPP operates under different institutional pressures compared to private procurement, it demonstrates how procurement in both sectors is increasingly leveraged to advance circular economy objectives.

Procurement also serves as a lever for sustainable development by promoting environmentally and socially responsible suppliers and products, as organizations can align their sourcing decisions with broader sustainability objectives [

25]. Effective procurement strategies thus contribute not only to operational efficiency, but also to brand reputation, stakeholder satisfaction, and innovation capacity [

26,

27].

Early foundational work by Monczka et al. [

28] demonstrated that procurement can serve as a source of competitive advantage through cost savings, quality improvements, and supplier innovation. More recent studies further support this view. Pal et al. [

29] found that supplier integration and collaborative procurement enhance supply chain performance, which in turn strengthens OC. Sustainable procurement, in particular, has been linked to improved financial outcomes, reduced risks, and increased stakeholder engagement [

30,

31,

32].

In sum, the literature affirms that procurement, especially when aligned with sustainability principles, is a strategic function that contributes meaningfully to competitive advantage. Building on these findings, we hypothesized as follows:

H2. Procurement strategies have a positive impact on organizational competitiveness.

2.3. Moderating Role of Procurement Strategies

While extensive research highlights the individual contributions of CEPs and PS to organizational performance, fewer studies have examined how these two dimensions interact, particularly in terms of how procurement strategies may moderate the effect of CEPs on OC.

Although direct empirical studies on this moderating relationship are limited, related findings provide a base for hypothesizing such an effect. For instance, Úbeda et al. [

33] emphasize that organizations employing procurement as a strategic tool generally achieve superior performance outcomes. Similarly, Van Opstal and Borms [

34] found a positive link between the adoption of circular economy practices and firm performance in Flemish companies, reinforcing the relevance of CEPs in strategic contexts.

The combined insights from these studies suggest that organizations with well-developed PS may be better positioned to harness the benefits of CEPs. PS can enhance the implementation of circular economy practices by enabling better supplier alignment, innovation diffusion, and efficient resource sourcing. Therefore, procurement may act as a facilitating factor that amplifies the impact of CEPs on competitiveness. Based on this rationale, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3. Procurement strategies moderate the relationship between circular economy practices and organizational competitiveness.

2.4. Mediating Role of Procurement Strategies

Although limited direct research addresses the mediating role of PS in the relationship between CEPs and OC, the existing studies offer important theoretical and empirical insights. Procurement is increasingly recognized not only as an enabler of sustainability, but also as a vehicle through which circular economy practices can translate into tangible performance outcomes.

Research shows that when CEPs are embedded into procurement activities, often referred to as circular procurement, organizations tend to achieve a range of economic, environmental, and social benefits. These include cost savings, waste reduction, improved resource efficiency, and enhanced stakeholder engagement [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Such outcomes can, in turn, contribute to competitive advantage.

Additionally, Zhu et al. [

39] offered more direct evidence by demonstrating that sustainable procurement mediates the relationship between environmental practices and firm performance. Their findings suggest that the positive effects of CEPs are amplified when supported by procurement practices aligned with sustainability goals.

This body of work implies that procurement can act as a critical conduit through which circular economy practices affect competitiveness. It enables organizations to operationalize CEP effectively, translating sustainability intent into competitive outcomes. Based on these insights, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H4. The relationship between circular economy practices and organizational competitiveness is mediated by procurement strategies.

2.5. Mediating Role of Organizational Culture

OCL encompasses the shared values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that shape how decisions are made and practices are implemented within an organization. A positive culture can encourage ethical behavior, employee engagement, and innovation, all factors that are critical for organizational success and sustainability.

Numerous studies highlight the significant role OCL plays in shaping sustainability-related behaviors, including the adoption of CEPs [

40]. A culture that supports sustainability can improve employee motivation and engagement, which in turn enhance competitiveness [

41].

Foundational work by Schein [

42] and subsequent studies [

43,

44] emphasize that culture acts as a baseline element for strategic alignment. A strong culture of innovation and continuous improvement has been positively associated with organizational performance and adaptability [

45,

46]. Specific to CEPs, Dey et al. [

47] identified supportive OCL as a key enabler in small and medium-sized enterprises across Europe. Similarly, Dangelico and Pujari [

48] found that a culture prioritizing environmental responsibility promotes the integration of circular economy practices, thereby contributing to competitive advantage.

Overall, the literature suggests that OCL plays a mediating role by shaping how CEPs are embraced and transformed into strategic outcomes. Based on this, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H5. Organizational culture mediates the relationship between circular economy practices and organizational competitiveness.

2.6. Moderating Role of Stakeholder Pressure

SP refers to the influence exerted by individuals or groups with a vested interest in an organization’s operations and outcomes, including customers, suppliers, employees, investors, communities, and regulators. Higher levels of stakeholder pressure can motivate organizations to adopt more sustainable and responsible practices, ultimately improving their competitiveness.

The existing research identifies SP as a key driver behind the adoption of CEPs and sustainable PS [

49,

50]. This pressure can take many forms, including regulatory requirements, market competition, and evolving societal expectations [

51]. Perceptions of an organization’s sustainability efforts by its stakeholders can significantly affect its reputation and, in turn, its competitive standing [

52].

Additional studies confirm that SP positively influences organizational outcomes across multiple dimensions, such as environmental stewardship, social sustainability, and innovation [

53,

54]. Organizations facing greater stakeholder scrutiny are more likely to implement PS that emphasize sustainability, such as ethical sourcing, supplier diversity, and environmentally responsible purchasing [

55]. This external pressure may also influence internal organizational values and drive a deeper cultural commitment to sustainability [

40].

Taken together, these findings suggest that SP can act as a contextual force that shapes how PS are formulated and how effectively they contribute to OC. Therefore, we hypothesized as follows:

H6. Stakeholder pressure moderates the relationship between procurement strategies and organizational competitiveness.

2.7. Moderating Role of Resource Availability

RA refers to the extent to which an organization has access to and control over the financial, physical, human, and technological resources necessary to implement its strategies and achieve its objectives. The availability of such resources has an effect on an organization’s capacity to adopt sustainable practices and maintain competitiveness in dynamic market environments.

Multiple studies suggest that RA plays a critical role in enabling organizations to pursue sustainability initiatives, including CEPs and innovative procurement strategies [

56,

57,

58]. Access to sufficient resources supports investments in new technologies, research and development, and employee training, all key levers for improving environmental performance and gaining a competitive edge.

RA has long been regarded as a determinant of strategic and operational performance, particularly in the face of environmental uncertainty [

59,

60]. Empirical evidence links higher levels of available resources to improved innovation, market share, and profitability [

61]. Kristoffersen et al. [

62], for example, found that firms with strong resource bases are more likely to adopt circular business models, which in turn enhance their competitive advantage.

Moreover, access to resources can facilitate the development of an OCL that is supportive of sustainability. Prior research highlights that resource-rich firms are more likely to cultivate positive attitudes toward environmental practices and implement circular strategies effectively [

37,

63,

64].

Taken together, these insights suggest that RA may condition the effectiveness of CEPs in driving OC. Accordingly, we hypothesized as follows:

H7. Resource availability moderates the relationship between circular economy practices and organizational competitiveness.

2.8. Mediating Role of Innovation

IN refers to the development or enhancement of products, services, processes, or business models that deliver new or improved value to customers and stakeholders. It is widely recognized as a driver of OC, enabling firms to differentiate themselves, reduce costs, respond to market changes, and improve sustainability performance [

65,

66].

IN supports the adoption of CEPs and sustainable procurement by generating opportunities for resource efficiency, waste reduction, and value creation [

17]. It also allows organizations to adapt to technological advancements, evolving customer needs, and regulatory shifts while opening new markets and collaborations [

67,

68,

69].

Within the procurement domain, IN plays a non-negligible role. Research shows that innovative procurement strategies, such as supplier collaboration, strategic sourcing, and early supplier involvement, enhance organizational performance and competitiveness [

70,

71]. These can lead to better supplier relationships, higher product quality, and cost savings, which collectively strengthen competitive positioning.

Moreover, IN has been found to mediate broader organizational relationships. Witjes and Lozano [

72] suggested that innovation in procurement can foster a sustainability-oriented organizational culture, which subsequently enhances competitiveness. Similarly, Ahi and Searcy [

73] highlighted that innovative procurement strategies help build a culture of innovation, which is positively associated with organizational performance.

These findings indicate that IN may act as a mechanism through which PS translate into competitive advantage, particularly in the context of sustainability. Based on this, we hypothesized as follows:

H8. Innovation mediates the relationship between procurement strategies and organizational competitiveness.

2.9. Moderating Role of Industry Characteristics

ICs refer to the structural and contextual features of the environment in which an organization operates, including market structure, competitive intensity, technological advancements, legal frameworks, and customer preferences. These characteristics shape the strategic choices available to firms and influence both their capacity to adopt sustainable practices and their ability to remain competitive [

74].

ICs are widely recognized as critical determinants of OC, as they define the opportunities and constraints that firms face. In highly competitive industries, characterized by low entry barriers and intense rivalry, organizations are often pressured to innovate, reduce costs, and differentiate themselves [

74]. These dynamics can both encourage and necessitate the adoption of circular economy practices and sustainable procurement strategies.

Empirical evidence supports this view, as Hojnik and Ruzzier [

75] found that firms operating in more competitive industries are more likely to adopt CEP. Similarly, Lieder and Rashid [

76] show that stringent regulatory environments increase the likelihood of circular economy adoption, as firms seek to comply with evolving legal standards while gaining a strategic edge.

Industry context also shapes perceived enablers and barriers to sustainability adoption. Factors such as customer demand for green products, government incentives, and the availability of recycling infrastructure play a significant role in determining the feasibility and attractiveness of circular strategies [

77,

78].

Together, these insights suggest that ICs may moderate the effectiveness of CEPs in enhancing OC. Accordingly, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H9. Industry characteristics moderate the relationship between circular economy practices and organizational competitiveness.

The existing literature extensively highlights the individual contributions of CEPs and PS to OC, particularly in relation to environmental sustainability, cost efficiency, and innovation. However, less is known about how these two strategic dimensions interact and potentially reinforce each other in shaping competitive outcomes. Specifically, the moderating and mediating roles of PS in the CEPs–OC relationship remain empirically underexplored, leaving a gap in understanding their combined strategic value.

Moreover, although prior studies acknowledge the relevance of contextual factors such as OCL, SP, RA, IN, and ICs, the complex interrelationships between these variables, and how they influence the effectiveness of CEPs and PS, have not been fully addressed. As a result, a more integrative approach is needed to capture the multifaceted dynamics that drive sustainable competitiveness.

This study sought to address these gaps by conducting an exploratory empirical investigation into the perceived interplay between CEPs, PS, and the contextual factors mentioned above. In doing so, it aimed to develop an initial, perception-based framework for understanding how organizations might leverage circular economy practices and procurement strategies to enhance competitiveness in a sustainability-driven business landscape. The inclusion of multiple mediating and moderating variables is supported by established theoretical frameworks. For instance, OCL and IN represent internal capabilities emphasized by the resource-based view, while SP and ICs reflect environmental contingencies highlighted in institutional and contingency theories. RA bridges internal and external contexts, representing the capacity to act upon sustainability ambitions. Together, these variables form a holistic framework for understanding how CEPs and PS influence OC under varying organizational conditions.

2.10. Conceptual Framework

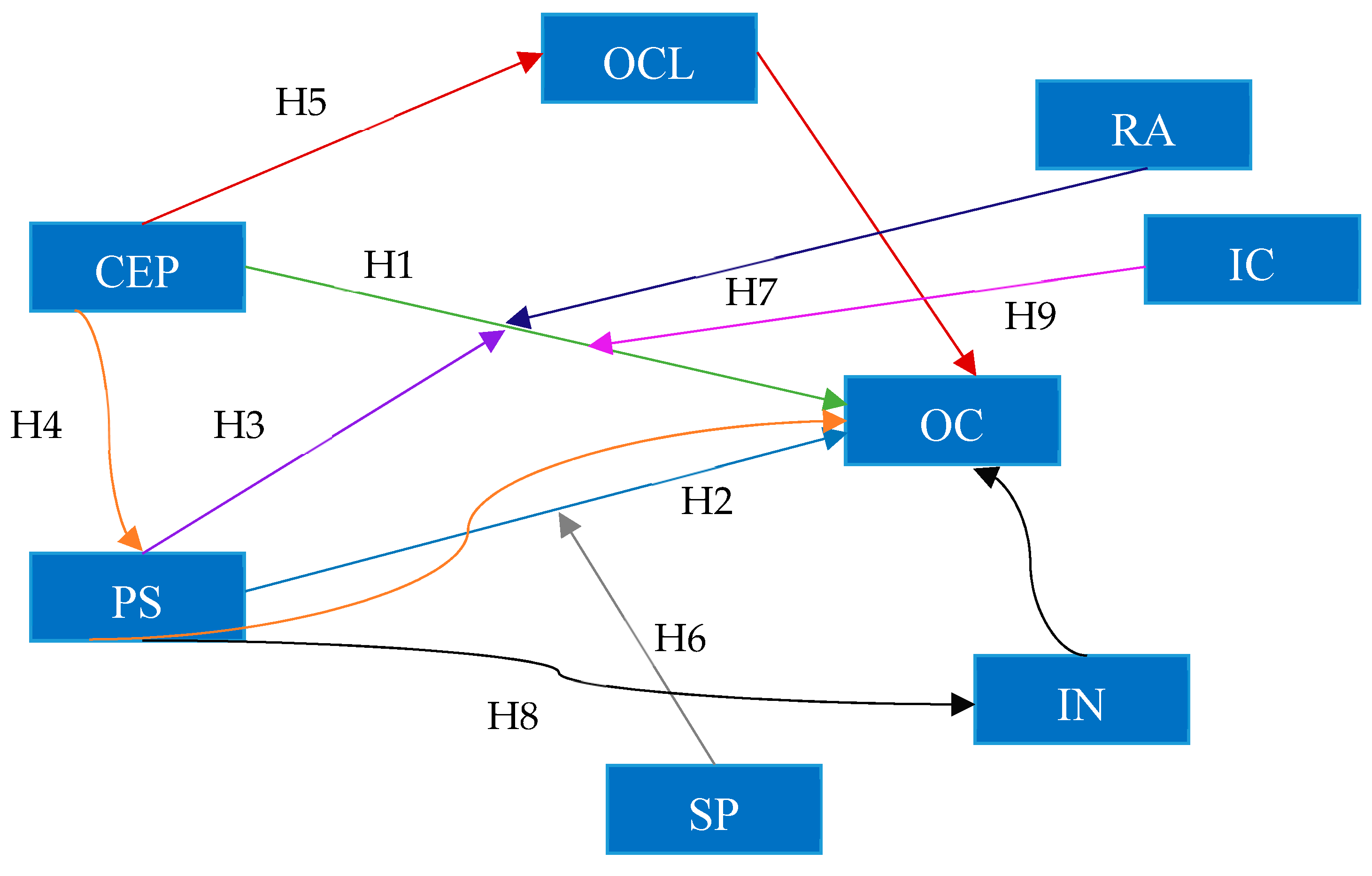

The conceptual framework guiding this study, illustrated in

Figure 1, outlines the core variables and their hypothesized relationships: CEPs, PS, and OC, along with five contextual factors—OCL, SP, RA, IN, and ICs.

Hypotheses H1 and H2 posit direct positive effects of CEPs and PS on OC, reflecting their strategic role in enhancing competitiveness. H3 introduces PS as a moderator of the CEPs–OC relationship, suggesting that the effectiveness of CEPs in driving competitiveness is amplified when supported by robust PS. H4 further positions PS as a mediator in this relationship, indicating that CEPs indirectly enhance OC through their influence on PS.

H5 proposes that OCL mediates the CEPs–OC relationship, emphasizing that a culture supportive of sustainability facilitates the translation of circular economy practices into competitive outcomes. H6 posits that SP moderates the PS–OC relationship, with higher stakeholder demands strengthening the strategic value of procurement.

H7 suggests that RA moderates the CEPs–OC relationship, enabling or constraining the implementation of circular economy practices. H8 positions IN as a mediator between PS and OC, highlighting the role of innovative procurement in generating competitive advantage. Lastly, H9 introduces ICs as a moderator in the CEPs–OC relationship, acknowledging that sector-specific dynamics influence the strategic impact of circular economy practices.

Together, these hypotheses form an integrated model for understanding how CEPs and PS, shaped by internal and external factors, interact to drive OC.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Participant Selection

This research adopts a quantitative and exploratory design created to examine emerging perceptual patterns in the interrelationships between CEPs, PS, and OC. Given the study’s objective of mapping conceptual interconnections and identifying potential pathways of influence, a cross-sectional survey was deemed suitable for this early-stage investigation.

Participants were drawn using a purposive sampling strategy to ensure disciplinary relevance. The inclusion criteria involved enrollment in accredited management programs. The final sample consisted of 568 valid responses, which exceeds the minimum sample size recommendations for structural and factorial analyses [

79], especially for exploratory purposes. The entire sample was drawn from the Bucharest University of Economic Studies (ASE), Romania, offering a localized perspective on sustainability and strategic management practices. The demographic structure of the sample was diverse: approximately 49% were enrolled in Bachelor’s programs, 47% were Master’s students, and 4% were doctoral candidates. The majority of the respondents (ca. 82%) were aged between 18 and 24, followed by 11% between 25 and 34, 5% between 35 and 44, and 2% aged 45 or older. In terms of gender, 57% identified as female, 41% as male, and 2% preferred not to disclose or identified outside the binary.

The focus on management students as respondents reflects the future-oriented and exploratory nature of the research. Management students, particularly those at the undergraduate and graduate levels, are increasingly exposed to sustainability-oriented curricula and are likely to shape the strategic decisions of organizations in the near future. Their perceptions, while not reflective of current managerial experience, offer valuable insight into emerging attitudes and strategic thinking around CEPs and PS. Thus, the study sought not to generalize findings to the current firm-level performance, but to explore theoretical relationships as perceived by tomorrow’s decision-makers.

3.2. Data Collection

Data was collected from March to June 2023 using a self-administered online questionnaire (Google Forms). Prior to the launch, the survey instrument was reviewed by academic experts to ensure content relevance, clarity, and construct alignment. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants, and anonymity was strictly maintained.

The questionnaire was developed using a combination of established and adapted scales, with items tailored to capture perceptions related to CEPs, PS, OC, and contextual moderators. A five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was employed to measure agreement with each item. While the constructs measured beliefs and perceptions rather than behaviors, this aligns with the exploratory and perception-based nature of the research.

To minimize response bias, several ex-ante procedural remedies were applied, such as ensuring anonymity, varying item phrasing, and clarifying that there were no right or wrong answers. Nevertheless, potential limitations inherent to perceptual data were acknowledged and are discussed later in the paper.

3.3. Common Method Bias

Given the reliance on self-reported data collected via a single method, common method bias (CMB) was tested using Harman’s single-factor test [

80]. The first factor accounted for 32.10% of the total variance, below the conservative 50% threshold [

81], indicating no dominant factor. However, consistently with the recent literature calling for more robust procedures [

82], we recognize that Harman’s test alone is insufficient. This limitation is acknowledged in our Discussion, and future research directions propose more diverse data sources to improve construct robustness.

3.4. Research Variables and Measurement

The variables used in this study were operationalized based on an extensive literature review, supported by discussions with academic and practitioner stakeholders to ensure practical relevance. Although some constructs were adapted, they retained theoretical alignment with their original definitions.

A full description of each variable, including its abbreviation, questionnaire items, conceptual definition, and original references, is provided in

Appendix A (

Table A1). Given the exploratory aim, the instrument was not intended for confirmatory measurement invariance but was instead designed to detect emerging patterns and directional relationships that may inform future theory development.

3.5. Statistical Procedures

All analyses were conducted using JASP version 0.17.3.0 [

83]. The statistical process began with descriptive analysis to establish baseline characteristics of the dataset. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to uncover latent structures between the items, employing Promax rotation and the minimum residual (MINRES) method for its suitability with perceptual data and non-normal distributions.

Reliability was assessed via Cronbach’s alpha, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was followed to validate the factor structure. Although not the primary objective, CFA was conducted to preliminarily assess the structural coherence of the constructs. This combination allowed for internal consistency checks while reinforcing the legitimacy of the adapted constructs. Correlation matrices and linear regression models were used to test direct relationships (H1–H2), while interaction terms and mediation analysis (delta method) were employed to assess moderation (H3; H6; H7; H9) and mediation (H4; H5; H8). Overall, this methodological design reflects the exploratory character of the study: theory-driven, but perceptually grounded, with the goal of generating new conceptual linkages that warrant future confirmatory research in practitioner contexts.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the eight key variables in this study. All constructs were modelled based on 568 valid responses, with no missing values. The mean scores ranged from 3.942 (PS) to 4.185 (IN), suggesting generally positive respondent perceptions across the constructs. The standard deviations ranged from 0.643 (SP) to 0.710 (CEPs), indicating moderate variability in responses. All the variables had a common maximum value of 5.000, reflecting the upper end of the Likert scale used.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To evaluate the dimensionality and construct validity of the measurement items, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using the minimum residual (MINRES) extraction and Promax rotation. Promax, an oblique rotation method, was selected due to the expected correlations between the latent constructs [

84], while MINRES was chosen for its robustness and minimal reliance on distributional assumptions.

The EFA results are presented in

Table 2. For each construct, eigenvalues exceeded the Kaiser criterion of 1.0 [

85], supporting unidimensionality. The variance explained for each construct surpassed the commonly accepted threshold of 30% [

86], with IN accounting for over 50% of the variance. Factor loadings across all the constructs ranged between 0.425 and 0.763, well above the 0.4–0.5 cutoff suggested by Stevens [

87], confirming strong item–construct relationships.

The uniqueness values ranged from 0.417 to 0.819. While slightly elevated for a few items in the PS and SP constructs, these values remained within an acceptable range and suggested that the extracted latent factors captured a substantial proportion of the variance in item responses [

89]. Taken together, these EFA results support the construct validity of the eight latent variables and justify their inclusion in further reliability testing, CFA, and structural modeling.

Overall, the robustness of these EFA outcomes—validated by eigenvalues, factor loadings, proportion of variance, uniqueness values, chi-squared test, and rotation method—provides satisfactory empirical support for the constructs under investigation.

4.3. Reliability Analysis

Internal consistency of the scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. All the constructs exceeded the recommended reliability threshold of 0.70 [

90], indicating acceptable-to-strong internal consistency across the measures: CEPs = 0.770, PS = 0.719, OC = 0.725, OCL = 0.796, SP = 0.732, RA = 0.800, IN = 0.831, ICs = 0.811. These coefficients lend credibility to subsequent analyses, ensuring consistent measurement across the sample.

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In the analysis, a CFA using the ML estimator was performed to investigate the relationships between eight variables: CEPs, PS, OC, OCL, SP, RA, IN, and ICs. The CFA provided substantial insights into the underlying factor structures of these variables. The models in all the cases yielded a significant chi-squared test with

p < 0.001, suggesting an acceptable fit of the models to the data [

91]. The factor loadings for each indicator were also highly significant (

p < 0.001), and the factor variances were fixed at 1.000 [

92]. Additionally, the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) values for each construct further supported the models’ adequacy: CEPs (0.931), PS (0.940), OC (0.915), OCL (0.994), SP (0.905), RA (0.990), IN (0.970), and ICs (0.951) (Hu & Bentler 1999) [

88]. The residual variances were significant for all the indicators, reinforcing the models’ robustness.

Specifically, the ML-estimated indicators for each variable showed the following ranges: CEP indicators ranged from 0.512 to 0.768, PS—from 0.468 to 0.647, OC—from 0.528 to 0.604, OCL—from 0.490 to 0.725, SP—from 0.445 to 0.618, RA—from 0.549 to 0.681, IN—from 0.577 to 0.643, and IC—from 0.593 to 0.699. The strong statistical evidence from both the chi-squared tests and the TLI values suggests that the hypothesized models fit the data well and accurately reflect the distinct constructs represented by each variable [

93].

Going further, all the Pearson correlations were statistically significant at the 0.001 level. Some notable relationships include a strong positive correlation between IN and RA (r = 0.750) and between PS and SP (r = 0.649). The

p-values confirm the significance of these correlations, illustrating a consistent pattern of relationships among the variables.

Table 3 presents the results for the assessment of convergent and discriminant validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all the constructs was above the recommended threshold of 0.5 [

94], indicating good convergent validity. For discriminant validity, the AVE for each construct should be greater than its corresponding maximum shared variance (MSV) and average shared variance (ASV) values [

95]. In our results, all the constructs met this criterion, indicating good discriminant validity. Therefore, we did not detect convergent or discriminant validity issues.

Table 4 presents a broad view of the linear regression analysis for OC under hypotheses H1 and H2. The model shows a significant fit, with R

2 = 0.429 and adjusted R

2 = 0.427, indicating that approximately 42.7% of the variability in OC is explained by the predictors CEPs and PS. The RMSE of 0.508 signifies accuracy in predicting OC. In the coefficient section, both CEPs and PS were shown to contribute significantly to the model, with the

p-values less than 0.001. The positive standardized coefficients (0.185 for CEPs and 0.514 for PS) highlight their positive relationship with OC.

4.5. Moderation Analysis

The moderation analysis was performed using linear regression models that incorporated interaction terms.

Table 5 represents the model summary, ANOVA, and the coefficients of the key interactions for the linear regression analysis conducted for hypotheses H3, H6, H7, and H9. The table summarizes the correlation coefficient (R), the coefficient of determination (R

2), the adjusted coefficient of determination (Adjusted R

2), the root mean square error (RMSE), the sum of squares for regression, the mean square for regression, the F-statistic for regression, the

p-value for regression, and the key interaction coefficients for each hypothesis.

The table provides a concise summary of the linear regression analyses performed. In particular, interaction terms such as CEPs*PS, SP*PS, RA*CEPs, and ICs*CEPs were found to be significant in the respective hypotheses. The models show a substantial variation explained (R2 values), indicating reasonable fits to the data.

The interaction between CEPs and PS was significant (p < 0.05), with a coefficient of 0.091. This suggests that the effect of CEPs on the dependent variable was moderated by PS. In other words, the relationship between CEPs and the outcome changes depending on the value of PS.

The interaction between SP and PS was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), with a coefficient of 0.074. This means that although there was an observable effect, it did not provide robust evidence that the effect of SP on the dependent variable was moderated by PS within the dataset.

The interaction between RA and CEPs was significant (p < 0.05), with a coefficient of 0.096. This indicates that the effect of RA on the dependent variable was moderated by CEPs. The relationship between RA and the outcome variable changes depending on the CEP value.

The interaction between ICs and CEPs was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), with a coefficient of 0.059. This means that there was no compelling evidence to suggest that the effect of ICs on the dependent variable is moderated by CEPs within the dataset.

4.6. Mediation Analysis

To ensure the robustness and reliability of our findings, the mediation analysis model underwent a validation process. Firstly, the delta method was applied to calculate robust standard errors, confirming the appropriateness of the model’s error structure. The calculated standard errors ranged from 0.025 to 0.041, indicating a reasonable level of estimation precision [

96]. Additionally, normal theory confidence intervals were generated for each path to provide an additional layer of certainty regarding the stability of the estimates. All confidence intervals for direct, indirect, and total effects excluded zero, reinforcing the statistical significance and reliability of these paths [

97].

The maximum likelihood (ML) estimator was chosen as the most appropriate technique for estimating the model parameters. This approach is widely recognized for its consistency and efficiency in handling complex mediation models [

98].

To affirm the statistical significance of each path in the model, z-values and corresponding

p-values were closely examined. Each pathway had a z-value greater than the critical threshold of 1.96 for a two-sided test, and the

p-values were all below 0.05, substantiating the statistical significance of the relationships between the variables [

99].

The confidence intervals for all the estimated paths were scrutinized to ensure that they did not contain zero, thereby confirming the effects’ significance. This analysis lent further credence to the robustness of the model [

100].

Table 6 summarizes the results of the mediation analysis for hypotheses H4, H5, and H8, including direct, indirect, and total effects, along with residual covariances and path coefficients. The analysis revealed a significant direct positive effect of CEPs on OC (estimate = 0.090,

p-value = 0.030). This finding corroborates the theoretical assumption that alterations in CEPs would directly correspond with changes in OC, thereby supporting the part of the hypothesis that posits a direct connection between these variables.

Furthermore, the study revealed substantial indirect effects. CEPs exerted an influence on OC through PS (estimate = 0.257, p < 0.001), which could support hypothesis H4 if it pertains to this pathway. For hypothesis H5, the indirect effect of CEPs on OC through OCL was significant (estimate = 0.164, p < 0.001). The total effect of CEPs on OC was discerned to be positive and substantial (estimate = 0.511, p < 0.001), incorporating aspects likely related to both hypotheses H4 and H5.

For hypothesis H8, the direct positive effect of PS on OC was detected (estimate = 0.450, p < 0.001), supporting the direct component of this hypothesis. The indirect effect from PS to OC through IN was found to be significant (estimate = 0.204, p < 0.001), suggesting a mediated relationship and strengthening the indirect aspect of H8 if it is related to this connection. The total effect of PS on OC, with both direct and mediated paths, was determined to be positive and highly significant (estimate = 0.654, p < 0.001), substantiating the full scope of hypothesis H8.

5. Discussion

In today’s sustainability-driven economy, the intersection of CEPs, PS, and OC is becoming increasingly strategic. This study contributes to this evolving field not only by confirming prior findings, but also by offering novel insights into the moderating and mediating mechanisms that shape these relationships.

Consistent with hypotheses H1 and H2, both CEPs and PS were found to significantly and positively influence OC. These results reinforce previous research [

1,

12,

22], while also validating the relevance of sustainable practices and strategic sourcing in fostering organizational advantage.

The study’s moderation and mediation analyses offer new theoretical contributions by revealing how the effects of CEPs and PS are contingent upon other factors. For instance, the moderation effect of PS on the CEPs–OC relationship (H3) underscores the idea that procurement is not only a direct driver of competitiveness, but also a strategic amplifier of sustainability initiatives. This interaction appears to be most relevant in contexts where procurement strategies are well-integrated with organizational innovation efforts and sustainability planning. In such environments, circular practices may be more easily translated into tangible performance outcomes due to greater supplier alignment and resource orchestration. Conversely, in less strategically developed procurement settings, the benefits of circular practices may be diluted. Therefore, insights suggest that organizational capabilities, such as procurement maturity and innovation readiness, may further condition the strength of this interaction—an avenue that future research could explore using multi-group or conditional process modeling. Similarly, the moderating effect of resource availability (H7) supports the view that organizations with greater access to financial, technological, or human resources are better positioned to benefit from CEPs—a finding aligned with resource-based and contingency perspectives.

The mediation effect of innovation (H8) confirms that PS contributes to OC indirectly through enhanced innovation capabilities. This finding echoes the literature linking green procurement to innovation [

101] and emphasizes that sustainability and competitiveness are increasingly intertwined through strategic creativity [

102].

In contrast, the non-significant moderation effect of industry characteristics (H9) diverges from earlier studies suggesting sectoral influence [

75]. A possible explanation lies in the uneven institutional or regulatory pressure across industries. Some sectors may lack the incentives or frameworks to support circular transitions. This result invites future studies to examine how policy environments or competitive intensity condition the CEPs–OC link.

The non-significant moderation of SP (H6) also raises questions. While prior research [

49] identified stakeholder influence as a powerful driver of sustainable sourcing, our findings suggest that the effect may not always be direct or linear. It is possible that stakeholder demands operate through other organizational levers, such as culture or strategic orientation, thus offering a rich avenue for further exploration.

Organizational culture (H5), on the other hand, emerged as a key mediator, reinforcing the idea that sustainability outcomes hinge not only on external practices, but also on internal belief systems and values [

43]. Leaders seeking to implement CEPs must thus align procurement and innovation initiatives with a culture that embraces long-term responsibility.

In summary, this study extends prior work by demonstrating that CEPs and PS do not operate in isolation. Their impact on competitiveness is shaped by contextual moderators such as RA and OCL, and transmitted through IN. Therefore, our research not only validated the established theories, but also contributed novel insights, establishing the significance of our work in shaping the evolving discourse on sustainability, procurement, and competitiveness. These exploratory findings should be interpreted as indicative of potential theoretical patterns, rather than conclusive evidence of causal relationships.

5.1. Managerial Implications

This research provides potential actionable insights for practitioners. First, managers should view circular economy initiatives not only as environmentally necessary, but also as strategic levers for competitiveness. Initiatives such as waste reduction, product reuse, and sustainable sourcing should be integrated into procurement policies and innovation planning. Second, procurement should be elevated from a functional to a strategic role, focusing on supplier collaboration, sustainable criteria, and innovation partnerships. Our exploratory findings suggest that organizations aligning procurement with sustainability may achieve improved performance outcomes. Third, RA plays a critical role in implementing CEPs. Managers in resource-constrained environments should consider phased or incremental approaches to circular transitions, while policymakers might support such firms with incentives or infrastructure. Fourth, managers should actively cultivate a sustainability-oriented culture. This involves setting values, offering training, rewarding sustainable behavior, and integrating ESG goals into performance metrics. As shown in our study, culture is not peripheral, but is a core enabler of CEP success. Finally, IN may be viewed as a bridge between procurement and competitiveness. Organizations should invest in R&D, encourage experimentation, and create internal systems that support the flow of sustainable ideas across departments.

Moreover, the exploratory findings suggest that organizations aligning procurement with sustainability may achieve improved performance outcomes. While the primary focus of this research is on business organizations, many of these insights are also applicable to public administration, particularly in areas such as sustainable procurement, innovation policy, and resource management, where public-sector decisions significantly shape systemic outcomes.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions and Directions for Future Research

As an exploratory study, this research offers initial empirical insight into highlighting the interdependencies between CEPs, PS, and OC, areas that have been studied independently but rarely in combination. By testing multiple mediators and moderators, the study adds nuance to our understanding of how sustainable practices influence competitiveness.

The non-significant interaction between industry characteristics and CEPs challenges prior assumptions and suggests that external pressures alone may not dictate sustainability adoption. Future studies could investigate this further across different regulatory environments, particularly through comparative or longitudinal research.

Our findings regarding stakeholder pressure also point to a need for new models that account for indirect or delayed stakeholder influence. This could involve examining how stakeholder expectations become embedded in organizational routines or value systems over time.

Resource availability emerged as both a theoretical and practical enabler of circular economy practices. Future research might explore how firms can overcome resource constraints, perhaps through partnerships, outsourcing, or digital technologies.

Additionally, a notable avenue for future investigation lies in exploring the gap between legislation and practice. Although circular economy and sustainable procurement are increasingly embedded in national and EU-level regulations, implementation often varies across sectors and organizational types. Understanding how organizations interpret and act upon such legislation could reveal critical barriers to effective circular transitions.

Finally, we encourage scholars to adopt interdisciplinary and systems-based perspectives, integrating insights from environmental science, organizational psychology, and strategic management to better reflect the complexity of sustainability transitions in contemporary organizations.

5.3. Limitations

This study offers exploratory insights into the perceived relationships between circular economy practices, procurement strategies, and organizational competitiveness. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the use of a cross-sectional survey limits causal inference. Second, data were collected from management students, whose perceptions, while informed by relevant education, do not reflect managerial experience. Moreover, since all the participants were enrolled in a Romanian university, the cultural and institutional context may further limit the generalizability of findings. This choice aligns with the study’s exploratory objective, but limits generalizability. Third, the reliance on self-reported data raises concerns about common method bias. Although statistical tests indicated no dominant factor, more robust designs, such as multi-source or longitudinal approaches, are recommended for future studies. Lastly, while construct development was grounded in the literature and expert input, further validation is needed, particularly for use with practitioner samples. Future research should aim to validate these findings in cross-cultural settings to account for potential regional differences in sustainability perceptions and strategic orientation.

Despite these limitations, the study serves as a conceptual foundation for future empirical research with managerial populations and alternative data sources.