Abstract

In construction, a large focus is placed on preventative safety measures to help mitigate workplace hazards. Traditionally, less focus is placed on communication strategies that address organizational risks should a major safety failure occur. Organizations can be exposed to financial, legal, and reputational risks following worksite fatalities. A crisis communication plan that considers incident attribution, organizational continuity, internal and external stakeholders, and messaging for short-term and long-term communications can help manage those risks. This study aimed to identify the extent that safety failures impact the financial, legal, and reputational aspects of a construction organization and the role of crisis communication planning in mitigating those risks. Through a survey of industry leaders, the perception of organizational impact was measured and compared to previous research. The results of this study indicate financial burdens are perceived as the most significant impact on organizations compared to legal and reputational consequences. The findings also show leaders agree crisis communication plans are useful in mitigating organizational risk. However, the results of this study highlighted numerous contradictions within the previous literature, which are areas for further education in the construction industry. To improve crisis management and communication planning, impacts of worksite fatalities should further evaluate indirect costs, legal repercussions, and the effects of stakeholder attribution on organizational reputation. There should be increased education on the purpose and functionality of crisis communication plans and a broader focus on response methods throughout the life cycle of a crisis to help mitigate organizational risks.

1. Introduction

Construction is one of the leading industries in accidents and fatalities. In the United States, it ranks highest in number of annual fatal work injuries and has the third highest fatal work injury rate of any industry [1]. Fatalities can have detrimental impacts on organizations and personnel. These impacts need to be managed effectively to reduce additional harm to people and allow opportunity for organizational recovery.

An organizational crisis is defined as an unexpected, low probability, high impact event that requires rapid decision making and can cause severe consequences to human life and organizational value [2,3,4]. Construction safety accidents and fatalities are considered crisis events as they have a significant impact on the health and safety of the workforce and create severe consequences for organizations. Research has shown that crisis communication practices are successful in mitigating organizational risk when crises do occur [3,4,5,6,7]. Yet, it has been found that construction organizations are typically ill-prepared for crisis events, including worksite fatalities, and lack comprehensive crisis communication plans [8,9]. This is important because preparation, response, and recovery from a crisis are critical in minimizing loss, continuing organizational functions, and resuming normal operations [10]. If not handled properly, crises can become larger disasters, threatening organizational success and continuity. Advanced planning for crisis can better prepare organizations for unexpected and high impact events through proactive response methods. In times of uncertainty, crisis management can help drive focus on organizational recovery, while maintaining important reputational assets with stakeholders [8].

In construction, a large focus has been placed on preventive safety measures, with the general belief that effective hazard and risk management can eliminate safety failures. Even research on the topic is typically dedicated to preventative methods while fostering improved safety measures, focusing on immediate incident circumstances and causes [7,11]. Yet, safety accidents throughout the industry continue to occur at one of the highest rates of any industry [1]. Little attention has been placed on understanding how construction organizations need to deal with a crisis and the pattern of events that evolve in response to a crisis event [9]. This means construction organizations have one of the highest rates of accidents, but as an industry, lack effective planning and resource allocation when safety failures occur. In construction, hazards and accidents are expected, therefore it is advantageous for organizations to forecast, prepare and allocate resources to minimize overall damage to organizational stability [12]. Effective crisis management is crucial as “80% of unprepared companies go out of business within two years of suffering a major crisis” [9] (p. 60). As a result, crisis communication plans should be a standard, integrated part of safety planning and utilized to help mitigate organizational risk following crisis events.

It is impossible to predict when a crisis may happen, who will be involved, and how long it will last. It is also impossible to know the impacts of a crisis event until it happens. To plan for crises and mitigate risks in advance, retrospective data and systematic literature reviews are critical navigational tools. Studying past safety failures, impacts, and key takeaways is a highly effective method to improve organizational learning without having to experience the trials firsthand. Comprehensive studies on construction fatalities and the role of crisis communication strategies can be used throughout the construction industry to identify hidden patterns, knowledge gaps, and facilitate better workplace safety. Organizational leaders should utilize this study and past research on fatalities and crisis communication strategies to help build a response frameworks that supports organizational resilience and recovery after a crisis event.

To help facilitate this knowledge, this study aims to identify the extent that worksite fatalities impact the financial, legal, and reputational aspects of a construction organization. This study also aims to determine the effectiveness of crisis communication plans in mitigating these risks. Based on the current literature, it is expected that organizations are negatively impacted legally, reputationally, and financially following a fatality event. It is also expected a majority of construction organizations do not have a comprehensive crisis communication plan in place prior to a fatality event.

2. Literature Review—Impacts of Worksite Fatalities

In construction, abundant safety hazards from production processes and labor-intensive activities create environments where accidents can have severe impacts on the workforce through injury, disability, and death [13,14]. Fatalities and accidents pose risks to organizational continuity as safety failures can lead to financial, reputational, and legal implications for construction organizations [8,14,15]. While the severity of these impacts may vary across organizations, each should be considered a risk following a safety failure and mitigated to prevent additional damage to the organization.

2.1. Financial Implications

Safety failures can have a significant impact on the financial health of a company. Previous research has shown workplace injuries and illness create increased costs for employers, victims, and society as a whole [10,12,14,16,17]. These costs can be incurred through direct costs like medical expenses, cost overruns due to project delays, and penalties from regulatory agencies. The costs can also be incurred through indirect costs like increased insurance premiums, lost labor, and workers’ compensation. While financial impacts may be the most recognizable and easiest to quantify following a safety failure, construction organizations may not appreciate the magnitude of these costs, especially the hidden or indirect costs that have been estimated to be four times higher than direct costs [12,16]. These costs can be detrimental to the bottom line, long-term profit, and overall success of an organization.

2.2. Legal Implications

Construction is a highly litigious industry [18]. Litigation fees, compensation and court settlements can result in substantial costs for organizations and can continue to carry cost burdens over time. Major injuries and fatalities increase the risk of legal and regulatory penalties on organizations and the people involved [10]. The burden of these costs can be detrimental to construction organizations that typically operate in high-cost and low-margin conditions.

In addition to litigation costs, legal activity can threaten an organization’s reputation and legitimacy, reduce productivity, reduce liquidity, and increase turnover [19]. Compared to financial losses, these negative consequences are more difficult to quantify, but are equally as substantial to organizational longevity. Beyond financial implications, reputation, productivity, and employee retention are all critical constructs to organizational success and can be threatened as a result of safety failures.

2.3. Reputational Implications

Safety failures can threaten company reputation including brand image and dissatisfaction among stakeholders [15,20]. The associated costs and damages to reputation can cause large disruptions in organizational production and success. The literature has shown major injuries or fatalities can impact an organization’s safety record, brand image, legitimacy, and competitive advantage [10,12,20,21].

Reputation is an interesting element when it comes to organizational impact because the reputation of a company is not something controlled by the organization itself, but rather how the organization is perceived by its stakeholders [22]. Among financial, legal, and reputational impacts, reputation may be the most difficult to quantify and control following a safety failure. A threatened reputation can disrupt how the public evaluates, perceives, and interacts with an organization [23]. While the impact to an organization may not be immediate or a direct financial loss, negative organizational perceptions can lead to employee dissatisfaction, reduced legitimacy, loss of external relationships, and negative word of mouth [8]. Over time, this could have a significant effect on employee retention and production, stakeholder participation and the ability to secure future work.

2.4. Role of Crisis Communication in Mitigating Organizational Impacts

Safety failures, and specifically fatal events in construction, are preventable crises [8]. These types of crisis events can be a critical test of organizational resilience and its ability to continue operations during a sudden and significant disruption [24]. The way an organization manages and communicates a crisis situation shapes the social construct of the company and influences future interactions with stakeholders [25]. When crises threaten organizations, the need for effective communication increases [26]. Weak crisis response can lead to stakeholder blame, regulatory scrutiny, and operational inefficiencies. It can also erode safety culture, reducing employee attitudes toward safety and creating uncertainty and trust [27,28].

Resilient organizations with strong crisis management programs are better suited to keep their core competencies intact and reconfigure organizational resources quickly for recovery [24,29]. Organizations prepared with crisis communication plans can respond swiftly with clear messaging, corrective actions, and regulatory cooperation. The most effective plans contain verbal, visual, and written communication between stakeholders and an organization with the goal of reducing concern, promoting recovery, managing perceptions, restoring legitimacy and confidence, generating support, and restoring confidence [3,6]. Optimal communication plans identify applicable stakeholders, consider internal and external messaging strategies, and plan for short-term and long-term communication in order to reduce organizational damage [8]. Integrating effective crisis management with strong safety programs and corporate resilience creates a holistic approach to help ensure organizations are better equipped to effectively manage crises, maintain compliance, and safeguard their long-term stability.

A review of the current construction communication literature identified the need for crisis communication within the construction industry [7,9,30,31], but the development of crisis communication methodologies has been lacking [9]. The industry places a large emphasis on preventative safety procedures but preparation for the risks and implications that can occur following a safety failure are limited [9]. While organizational crisis communication plans may be lacking, not all emergency response processes are absent. Many construction organizations do include emergency action plans or emergency response procedures as part of their safety management systems.

2.5. Crisis Communication Plan Versus Emergency Action Plan

In construction, the creation and implementation of an emergency action plan is a standard element in safety planning. A typical emergency action plan will outline a set of procedures that workers should follow in case of emergency including evacuation processes, notification of emergency services, and the roles and responsibilities of employees during a crisis event. The plan is typically an immediate response to a site-specific emergency. Often times, emergency action plans are collapsed with crisis communication plans. Defining emergency action plans in the context of construction is difficult. There is no standard definition or regulation as to what is included and most of the existing literature has not addressed the differentiation with strategic crisis communication plans. The purpose and function of emergency actions plans are ambiguous in a sense that the meanings can differ from other industries where emergency action plans are used.

This study defines emergency action plans as a site specific standard operating procedure to be used following an emergency event, inclusive of the communication and execution of stop work, evacuation routes, notification of emergency services, accident investigation, and government reporting. Emergency action plans are localized and focus on immediate emergency response procedures intended to protect employees and prevent imminent danger. Unlike emergency action plans that are focused on immediate exigency, crisis communication plans emphasize short- and long-term communications with stakeholders and aim to protect all aspects of the business.

There is a difference in concept and functionality between construction crisis communication plans and emergency action plans. A crisis communication plan is the communication between stakeholders and the organization throughout the life of the crisis event, with the intent of mitigating organizational harm and promoting recovery. It extends beyond immediate emergency response and focuses on the continuity of the organization. A crisis communication plan encompasses an organizational strategy that includes consideration of incident attribution, organizational continuity, internal and external stakeholders, and messaging for short-term and long-term communications. This should include long-term planning inclusive of preparation, prevention, containment, recovery and learning to help recover critical functions and resume normal business practices following a crisis event [9,20,32].

While the emergency action plan is an important part of incident response, it does not fully encompass all components of a well-conceived organizational crisis communication plan to mitigate long-term risks. A crisis communication plan provides a more wholistic approach for organizational recovery following an emergency event. The differentiation between an emergency action plan and a crisis communication plan is imperative in defining the role of crisis communication strategies in mitigating organizational damage outside standard emergency response procedures.

3. Methods

To identify the impact of worksite fatalities on organizations and evaluate if crisis communication strategies are relevant to mitigate risks, data were collected via industry survey. The survey was distributed and completed by participants digitally. Survey responses were compiled via QuestionPro, a computer-based survey and analytics software. A comparative analysis was then conducted to cross reference categorized quantitative data and identify trends and relationships amongst the reported impacts, organizational size, and effectiveness of a crisis communication plan. Thematic analysis was then used to evaluate the qualitative data results from the comment sections. The quantitative results were compared with commentary provided throughout the survey by the research team to better understand the summation of the survey responses.

Prior to distribution, the survey was approved by Arizona State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure ethical research and protect participant rights and welfare. It sampled construction organizations in North America that experienced a workplace fatality in the last 20 years. The distribution groups were identified based on contacts and agencies that were familiar to the research team. The groups included members of the Roofing Alliance, the Beavers Charitable Trust, and the Arizona Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA). Members of these organizations were emailed and asked to participate in the survey. Any participation was voluntary and anonymous.

It was requested only C-level employees complete the survey. High level executives were presumed to have adequate knowledge of the financial, reputational, and legal aspects of an organization to complete the survey.

Fatal events can result in litigation and have potential for privacy requests from the victims and their families. One barrier to effective fatality research is the emotional, sensitive, and contentious nature of the crisis. Information about the crisis event is often guarded, seen as confidential, and a source of power in potential negotiations [30]. It was assumed C-level executives would have the authority and ability to provide company information while maintaining legal or privacy restrictions. By limiting the survey respondents, it was understood the results may hinder perspective diversity. However, it was assumed upper management and ownership could offer more insight into wholistic organizational impacts compared to frontline workers and mid-level management.

3.1. Organizational Characteristics

The survey included 21 total questions divided into three sections provided in Table 1. The survey was primarily structured with dichotomous yes/no questions. This was intended to keep the survey quick and simple to complete, while also providing straightforward data. Questions regarding organizational gross revenue, number of employees and estimated costs that were not reasonably answered with dichotomous questions were employed using a Likert scale and ranges of values. This provided a wider range of data to evaluate fatality impacts based on organizational size and costs. Each question had a response section that allowed respondents to write in additional or clarifying comments. The first section provided characteristics of the responding organization including the title of the person completing the survey and organizational size based on gross revenue and number of employees.

Table 1.

Survey sections and research questions.

3.2. Impacts of a Fatality

The second section of the survey focused on the impacts of a fatality as these events tend to have the greatest impact on an organization. First, it confirmed the organization experienced a fatal event in the last 20 years. Participants were then asked to estimate any direct and indirect costs associated with financial, legal, and reputational consequences from the fatal event.

As part of the survey, respondents’ perceptions of financial, legal, and reputational impacts were measured to try and quantify the impact of each risk. The study aimed to identify if one impact was more severe than another. This information collection was intended to help organizations navigate the best areas for focus and resources during crisis planning.

3.3. Organizational Crisis Planning

The third section of the survey aimed to identify the extent of organizational crisis planning for a fatal event. Respondents were asked if their organization had a crisis communication plan in place, and the components of that plan prior to the fatal incident. Additionally, the survey questioned if leaders believed crisis communication planning helped mitigate legal, financial, and reputational damage caused from the fatality. Survey participants were given an opportunity to share their organization’s crisis communication plan to supplement survey results. This offered an opportunity for the research group to review the plans and better define crisis communication plans in construction.

4. Results

Following survey distribution, a total of 26 completed surveys across three distribution groups were recorded. There were six unfinished surveys, and nine organizations noted they had experienced an onsite fatality in the last 20 years.

4.1. Section One—Characteristics of Participating Organizations

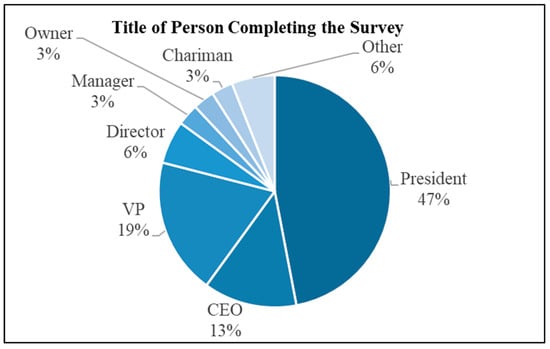

The first section of the survey provided characteristics of the participating organizations and the associated representative. A majority of the respondents, 84%, were C-level executives or above. Most of the responding organizations would be considered small to mid-size construction organizations grossing under $1 billion per year with less than 500 employees [33]. Complete organizational characteristic results are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the organizations—respondent titles. n = 26.

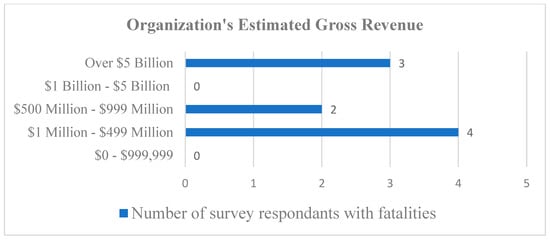

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the organizations with fatalities—estimated gross revenue. n = 9.

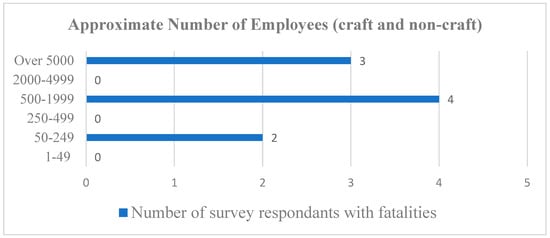

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the organizations with fatalities—approximate number of employees (craft and non-craft) in the organization. n = 9.

The results indicate 6% of participants were company owners or chairman, 79% were upper management (CEO, president, or VP), 9% of participants were mid-level management (director, manager), and 6% responded with “other”.

To help make comparisons in crisis communication planning across the construction industry, it was determined organizational size should be considered. Smaller organizations with limited staffing and resources may be less likely to have robust safety and crisis communication plans compared to larger organizations with dedicated teams and resources [34]. Research has shown that smaller organizations have a larger burden when it comes to meeting health and safety regulations. With limited resources, smaller groups aren’t able to take advantage of the economies of scale to meet safety standards, much less create comprehensive crisis communication plans [35]. Research has also shown that workers in smaller organizations are at greater risk of fatal accidents [35], which makes crisis communication planning even more important. Fatality impacts can have a larger burden on organizations with smaller revenue margins and more restricted resources. To help evaluate impact data based on organizational size, estimated gross revenue and number of employees were captured.

Of the 26 organizations that completed the survey, 73% were mid-size grossing between $1 million and $499 million per year, with another 8% grossing between $500 million and $999 million. Only 4% were small business with under $1 million in gross revenue and 15% were large organizations with over $1 billion in gross revenue. Of the nine organizations that experienced a fatality, four grossed between $1 million and $499 million per year, two grossed between $500 million and $999 million and three grossed over $5 billion as shown in Figure 2.

To further understand crisis communication planning based on organizational size, the approximate total number of employees, both craft and non-craft was requested. Of the 26 organizations that completed the survey, the majority, 46%, had between 50 and 249 employees. 19% had less than 50 employees, 4% had between 250 and 499 employees, and 19% had between 500 and 1999 employees. Twelve percent of respondents said they had over 5000 employees.

Of the nine organizations that experienced a fatality, two had between 50 and 249 employees, four had between 500 and 1999 employees and three had over 5000 employees as shown in Figure 3. Based on the data provided from this test group, the likelihood of a fatality is not reserved for smaller organizations, but rather organizations of all sizes were exposed to fatality risks, with the most fatalities occurring in mid-sized organizations with 500 to 1999 employees, and grossing $1 million to $499 million.

Evaluating the number of employees was helpful in differentiating the types of construction organizations and their associated risks from a fatality. General contractors that utilize subcontractor workers may have a smaller number of employees with direct safety risks. If a fatality occurs on a jobsite, there could be variable organizational risk depending on the employment status of the employee (whether employed by the subcontractor or general contractor). A fatal event with a subcontractor employee may influence the subcontractor organization directly, but have limited impacts to the general contractor.

4.2. Section Two—Fatality Impacts

The second section of the survey focused on the financial, legal and reputational impacts of a fatality event. The number of respondents for each question in this section varied. Of the nine respondents that noted they had experienced a fatality; some answered each question using the dichotomous or Likert scale multiple-choice options and others opted to use the write-in option to clarify their response. For consistency, only the multiple-choice answers were used in the data analysis. Percentages were calculated based on the total number of yes/no or Likert scale responses per question. Any write in answers were captured as a subjective response and reviewed as participant comments outlined later in the research.

4.2.1. Financial Impacts

When asked if the organization was impacted financially by the fatality event, 86% responded “yes”. For further financial insight, participants were asked to estimate the direct and indirect costs associated with the fatality as shown in Table 2. Direct cost estimates ranged equally across respondents from $1 to $999,999 with 25% noting they were uncertain of the amount but agreed there were direct costs to the organization. Similarly, 37.5% of respondents noted they were uncertain of the indirect costs, with another 37.5% estimating indirect costs between $500,000 and $999,999.

Table 2.

Organizational financial impacts with estimated direct and indirect costs. n = 8.

To help evaluate financial impacts following a fatality a cross examination of organizational size based on gross revenue and number of employees was used. Based on the data provided, there was not a clear relationship between direct costs, indirect costs and organizational size.

Comparing direct cost estimates to gross revenue, there was not a direct relationship between organizational size and the financial impacts following a fatality. There was also not a direct relationship between estimated direct and indirect costs and the number of employees as shown in Table 2. Direct cost estimates were split between all organizational size as shown in Table 3. In fact, one of the smallest organizations ($1 million–$499 million and 50–249 employees) estimated direct costs in the lowest cost bracket ($1–$99,999), and one organization, the same size, estimated direct costs to be in the highest recorded cost bracket ($500,000–$999,999).

Table 3.

Comparisons of company sized based on gross revenue and number of employees with estimated direct and indirect costs.

In evaluating indirect costs and organizational size, three of the five respondents estimated indirect costs between $500,000 and $999,999, but there was no direct relationship between indirect costs and organizational size based on gross revenue or number of employees. Results are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. One of the smallest organizations ($1 million–$499 million and 50–249 employees) estimated direct costs in the lowest cost bracket ($1–$99,999), and one organization the same size estimated indirect costs to be in the highest recorded cost bracket ($500,000–$999,999).

Table 4.

Comparisons of company sized based on gross revenue and number of employees with legal and reputational impacts.

Table 5.

Comparisons of legal and reputational impacts and estimated direct and indirect costs.

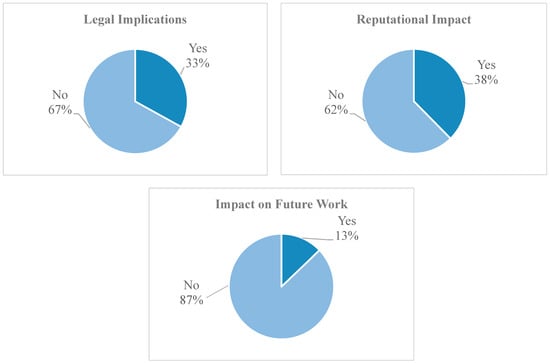

4.2.2. Legal and Reputational Impacts

To help identify the legal and reputational impacts of a fatal event, respondents were asked if the organization faced legal and reputational implications; 67% and 63% responded “no” respectively. When asked if the fatality event impacted the ability for the organization to secure future work, the majority, 88%, also responded “no”. Legal and reputational responses are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Identifying legal and reputational impacts following a fatality. From top to bottom: did the organization face legal implications (n = 9); reputational impacts (n = 8); an impact on the ability to secure future work (n = 8).

A cross examination of organizational size based on gross revenue and number of employees was used again to evaluate legal and reputational impacts. Based on the data provided, there was not a clear relationship between legal impacts, reputational impacts or the ability to secure future work, and organizational size.

As summarized in Table 4, organizational size was not a factor in whether fatalities resulted in legal or reputational impacts. The three organizations that said they experienced legal consequences were split in company size based on number of employees (50–249, 500–1999 and over 5000), and varied significantly in organizational size based on gross revenue ($1 million–$499 million and over $5 billion). The three organizations that said they experienced reputational impacts were also split over company size based on gross revenue ($1 million–$499 million, $500 million–$999 million, and over $5 billion) and number of employees (500–1999 and over 5000). Only one organization said there was an impact in the ability to secure future work. There was not a clear connection between organizational size based on the limited data sets in this study.

The data were evaluated to see if there was a relationship between legal or reputational impacts and estimated costs. Results are summarized in Table 5. Again, there was not a clear connection between those that experienced legal or reputational damage and a higher cost estimate. Some of the highest cost estimates, over $500,000, were not impacted by legal consequences, while others in the same cost estimate category did have legal impacts. Some of the organizations that estimated costs between $100,00–$499,000 also claimed to have had reputational impacts, while others did not. All but one organization did not see an impact in securing future work. A direct connection could not be made between future work and estimated costs of a fatality.

4.3. Section Three–Fatality Crisis Planning

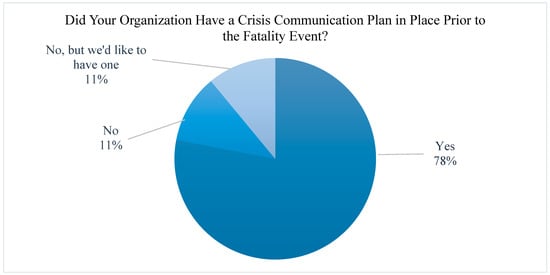

Section three of the survey turned focus to evaluating the presence and effectiveness of crisis communications for a fatality event as summarized in Figure 5. Participants were asked if their organization had a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatality event. It was specifically noted for the purpose of this study that a crisis communication plan is not the same as an emergency action plan, although the two can be related. A crisis communication plan was defined as a preventative action plan used to mitigate financial, legal, and reputational impacts that threaten organizational survival during crisis events. Immediate incident work stoppage, notification of emergency services, accident investigation, and government reporting were assumed to be part of the emergency action plan, not an organizational crisis communication plan. In response, 78% respondents said they had a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatality and 100% of those that had a plan in place prior to the fatality say it was well executed and helped mitigate legal, financial, and reputational damage.

Figure 5.

Crisis communication plan effectiveness—organizational plan prior to fatality. n = 9.

To further understand the impact of crisis communication planning and execution, gross revenue and the number of employees were compared to the number of organizations that had a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatal event. The organizations that did have crisis communication plans in place were split amongst the gross revenue categories and number of employees, as shown in Table 6. Of the two organizations that said they did not have a crisis plan in place, one grossed between $1 million and $499 million. The other grossed between $500 million and $999 million. Both organizations said they had 500–1999 employees. From the data provided, there was not a clear indication that organizational size was a contributing factor in the creation or execution of a crisis communication plan.

Table 6.

Comparisons of company sized based on gross revenue and number of employees with the creation of a crisis communication plan prior to the fatal event.

The data were also evaluated to see if there was a relationship between those that had a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatality, and the resulting financial, legal and reputational impacts. Of the seven organizations that had a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatality, direct costs, legal implications and reputational impacts were varied without a clear relationship between crisis planning and organizational impacts as shown in Table 7. Of the two organizations that said they did not have a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatal event, one claimed they did not face any financial, legal or reputational impacts. The other had one of the most severe results, with indications of direct and indirect cost burdens, financial impacts, and reputational impacts, including the inability to secure future work.

Table 7.

Evaluation of organizational impacts compared to organizations with a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatality.

4.4. Communication Plan Effectiveness

One expectation for this research was a majority of construction organizations would not have a comprehensive crisis communication plan in place prior to a fatality event. Due to that expectation, it seemed necessary to gauge organizational perceptions of advance crisis communication and organizational planning related to safety failures. Participants were asked if they thought advanced communication planning would help mitigate organizational risks associated with a fatal event: 57% agreed that it would. To help understand if fatal events have driven further crisis communication improvements, participants were asked if their organization implemented a new crisis communication strategy or planning following the fatality incident. 63% responded “no”.

Having not found a clear relationship between crisis planning and organizational impacts, the question then became, how effective were the crisis communication plans in mitigating organizational harm? In evaluating crisis communication plan effectiveness, participants were asked questions regarding legal, financial, and reputational risks, consideration of stakeholders, and the timeline of the plan. All of these elements have been identified as important components to an effective crisis communication strategy following a safety failure [8].

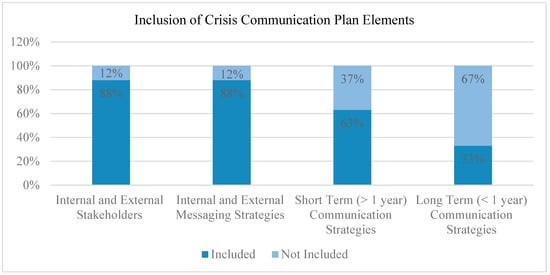

As illustrated in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Crisis communication plan effectiveness—inclusiveness of crisis communication plan elements.

- Eighty eight percent of respondents said their crisis communication plan identified internal and external stakeholders.

- Sixty three percent said their plan identified short-term communication strategies and thirty three percent identified long-term strategies.

4.5. Survey Comments

Workplace safety failures are unique scenarios and the complexities of a fatality impact organizations differently. Construction is a multidisciplinary industry and the impacts of a safety failure may affect multiple levels of an organization and worksite. In consideration of the many variables that effect an organization and its members, the survey permitted a space for voluntary comments following each question. The comments, insights, opinions, and additional details provided are beneficial as supplemental information to the multiple-choice structure of the survey questions. The relevant comments are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Participant comments, insights, opinions, and additional details.

A trend throughout the participant comments was that people within the organization and jobsite were highly impacted. Many of the comments allude to the fact that a fatality has a significant impact on organizations and the workforce, even if it is not quantified. Impacts like morale and grief are difficult to quantify, but are equally important when evaluating the effects on productivity and organizational success. The provided comments also reinforce the need for internal and external messaging strategies. The people on site were noted as being impacted the most significantly, but that does not necessarily mean internal employees. Subcontractors, joint venture partners, industry peers and partners are also impacted and should be considered in communication strategies.

Another theme within the comments was the impact to production. Reduced production and employee turnover were not directly measured in this study, but should be a consideration for future work as both aspects do have indirect costs and potential reputation impacts on an organization. Another noteworthy consideration was the relationship between general contractor and subcontractor following a fatal event and the impact to each organization. Two participants noted their fatality event was associated with a subcontractor. This study did not differentiate impacts to general contractor versus subcontractor organizations. Future work should make this differentiation and re-evaluate the scale of organizational impact to each type of organization.

In addition to general comments, participants were asked to share their company’s crisis communication plan. In total, two plans were submitted. Following a review of the plans, it was determined that one of the plans was an emergency action plan that addressed immediate incident work stoppage, notification of emergency services, accident investigation, and government reporting. It was not a comprehensive crisis communication plan that addressed short- and long-term strategy, impacted stakeholder groups, or applicable messaging. Rather, it outlined the communication and notification responsibilities of appointed representatives within the organization. The number of provided crisis communication plans was not sufficient enough to draw conclusions pertinent to the study. The two plans provided did not provide a large enough sample size to determine how crisis communication plans are currently utilized as a risk mitigation tool throughout the construction industry.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify the extent that safety failures impact construction organizations and the role of crisis communication planning in mitigating those risks. It is important to note the results of this study were measured by subjective perceptions. The way people feel about their organization and the subsequent consequences of a fatal event may not portray a true representation of the results and risks that were present for the organization itself. The survey results did provide valuable insight into the estimated costs of a worksite fatality and the perception of legal and reputational impacts. Comments throughout the survey offered additional context and observations into how organizations were affected by a fatality and the role of crisis communication in response and recovery. The data provided were useful in identifying how fatalities are perceived to impact an organization, but the subjectivity of the results produced inconsistencies with previous research. These contradictions, based on survey results are considered key findings of this study and are evaluated in the next sections.

5.1. Financial Implications

Survey results confirmed worksite fatalities do have a financial impact on construction organizations. The amount of direct and indirect costs varied across organizations and there was not a clear indicator of costs based on organizational size. In comparison to legal and reputational impacts, the results suggest financial impacts were the most severe organizational consequence following a fatal event.

An interesting finding from the cost results was most organizations estimated the direct costs to be similar to indirect costs. This contradicts previous research that has estimated the indirect costs of a fatality to be up to four times more than direct costs [12,16]. Of the five organizations that provided estimates for both direct costs and indirect costs, only one estimated indirect cost to be higher. This contradiction could be a result of organizations not recognizing or accounting for the full extent of indirect costs following a fatality. As one respondent noted “although dollar amounts were not necessarily tracked, a fatality has a huge impact on the project’s employees and their ability to recover and return to a productive state…”. The respondent in this case acknowledged indirect costs of lost production and employee recovery were not accounted for.

Direct costs like medical expenses, cost overruns, and regulatory penalties are easily tracked and have a direct effect on the bottom line. These costs can be directly attributed to the fatal event. Indirect costs on the other hand may not be well recognized and could be masked amongst other organizational factors. It was clear from multiple survey comments that the people or employees were significantly impacted following a fatal event. As one respondent noted, “Several people quit and others are emotionally affected. Production on the job is impacted for weeks”. The provided commentary suggests that employee emotions and reactions to the fatality caused changes in production, morale, and retention. It is feasible organizations did not quantify or account for reduced employee production or hiring new employees as an associated cost of the fatality. While all costs eventually impact the bottom line, indirect costs could be carried out over longer amounts of time, making it harder to identify and directly connect to a fatal event. As a result, the magnitude of indirect costs associated with a fatal event was likely under estimated in this study.

5.2. Legal Implications

Compared to the financial impacts, legal risks appeared to be less significant, but still a relevant threat to organizations following a fatality. With one third of respondents noting they faced legal consequences; the results suggest safety failures can occur without legal repercussion. While this may be accurate, previous research has indicated litigation can have detrimental impacts on organizations [36], especially following a safety failure. The lower attribution of legal consequences reported in this study could be due to the organizational structure of the construction project, or perhaps organizational longevity following the fatal event.

Two of the organizations that stated they did not face legal consequences following the fatality also noted in the comment section that the fatality happened to a project subcontractor rather than a direct employee of their organization. This is noteworthy as the impacts, and specifically the legal impacts, of the fatality may not carry through all project participants. If legal action was taken by family members or stakeholders against the employer of the deceased, the impacts would have likely been isolated to the employer. Any litigation consequences from the fatality may not encompass the general contractor or project participants, whereas financial and reputational impacts may have a larger effect on all project participants.

Another reason legal implications may be underreported in this study is the organizational longevity of the responding organizations. It is recognized that the participating organizations in this study are still operational, and did not face ceased operations or significant restructuring due to legal, financial, or reputational pressures. Organizations that have discontinued operations, such as Hultgren Construction [37], or DBi Services [38], following a fatal event are not represented in this study. Inclusion of organizations that are both operational and non-operational following a fatality would likely produce much different results regarding the impact of litigation and subsequent consequences.

5.3. Reputational Implications

Contrary to research expectations, a majority of respondents said the fatality did not impact the reputation of their organization and they were still able to secure work. This suggests reputational implications following a fatality are minimal. But given past research and literature on the topic, it seems improbable that there were no reputational impacts following a fatal event. Reputational implications have been well identified in the crisis management literature as a risk [10,12,15,20,21]. The implications of reputational damage seem to be overlooked in this case.

As seen in the commentary section, fatal events have a significant impact on the people within the organization and at the job site. The emotional toll, morale, and loss of production as described, surely come with altered perceptions of the work, safety culture, and organizations involved. While not all perceptions are assumed to be negative, the crisis response and subsequent actions taken on behalf of the organization do have an influence on stakeholder perceptions and attributions [8,21].

The conflict between respondent perceptions of reputational impacts and previous research dedicated to crisis impacts suggests construction leaders do not understand the complexity of organizational reputation and stakeholder attribution. Organizational leaders may not understand reputations are driven by public perception and how that affects an organization over time. This is an area for opportunity and education within the construction industry. Organizational leaders need to be aware of internal and external stakeholder perceptions before and after a crisis event. Without a systematic assessment of reputational changes, there is no clear indication of how organizational reputation has changed. There is also no clear understanding if the organization is at risk of disassociated stakeholders or the opportunity to secure future work.

Other aspects that may have contributed to conflicting results regarding reputational damage are the format and context of the survey provided. When responding on the Likert scale, company leaders were likely reporting impacts based on financial or economic burden as those are the most common metrics to quantify and translate to organizational loss. The subjective comments were more focused on organizational climate and culture, which are more difficult impacts to quantify. Similar to other results, it is likely the reputational impacts of the fatality were underrepresented and could be masked by other business factors.

There are a variety of factors that could blind company leaders to reputational changes. One factor is the business cycle. In construction, interest rates and economic drivers shape the demand for construction contracts. In accordance with supply and demand patterns, if the demand for construction is high, the reputational impact of an organization may have no bearing on securing work. When there is more demand than there is supply, reputations and the legitimacy of the company can have less influence in the competitive market. Whereas during slower periods, when competition is high, the safety record and reputation of the company may have more influence on the ability to secure work. Obtaining contracts can be more selective where reputation plays a larger role in project selection and partnerships.

A similar sentiment can be illustrated through employment recruiting and retention. When unemployment rates are low and recruiting is more competitive, the reputation and health of an organization may play a larger role in recruiting and retention efforts as employees can be more selective of their employer. If unemployment rates are high and there is demand to increase the workforce, potential employees may be less selective of employers and therefore reputation may have less of an effect on recruiting capabilities. It is possible in this study there are long-term reputational impacts to the organizations that have not yet been seen by organizational leadership.

5.4. Impact Perceptions Versus Reality

The disparity between perceptions and the reality of organizational impacts is an area that requires additional analysis outside the scope of this research but is worth discussion given the contradictions presented in this study. The way individuals perceive risk, and the subsequent consequences is inherently subjective and shaped by cultural, social, and political influences, leading to discrepancies between perception and reality [8,39,40]. These cognitive biases affect how people recall past events and assess organizational risks, creating gaps in understanding. Furthermore, emotional responses to crises can distort these perceptions, making it difficult for respondents to provide rational and unbiased evaluations of impacts [9].

Ignorance of vulnerability could be another critical factor influencing misperceptions of risk and the impacts of fatalities. The construction industry often operates under a culture of managerial invincibility and fatalism, assuming that preventative safety measures alone can eliminate uncertainty and risk [7,9]. This overconfidence and diverted attention away from building resilience results in a failure to recognize inherent vulnerabilities, leaving organizations unprepared for unexpected crises. Even when risks are acknowledged, a lack of dedicated resources toward crisis management hinders the ability to effectively analyze the totality of crisis events. Research has shown that crisis planning and response in construction remains rudimentary, fragmented, and underfunded, preventing organizations from fully understanding the long-term implications [8,9]. The failure to invest in crisis management and a reliance on preventative measures only exacerbates industry-wide vulnerabilities, leaving room for educational improvement across the industry.

5.5. Role of Crisis Communication

Contrary to expected results, a majority of respondents claim they had an effective crisis communication plan that helped mitigate risk. One hundred percent of those with a crisis communication plan in place prior to the fatal event agreed that the advanced planning helped mitigate legal, financial, and reputational damage. This was a significant finding from the research because the overall sentiment from survey respondents was crisis communication plans were effective in mitigating damage.

However, the study identified gaps in what respondents considered a crisis communication plan. Effective crisis plans contain communications that consider internal and external stakeholders and plan for communications throughout the crisis life cycle. While a majority of organizations stated stakeholders were considered in their crisis communication plan, short- and long-term communication strategies were not predominantly included in crisis plans. Sixty seven percent of the organizations that experienced a fatality lacked a long-term communication strategy. This is an important aspect to consider in crisis communication planning because the impacts of an incident do not cease immediately. To protect the organization from additional damage, communications with internal and external stakeholders should continue as investigations, findings, and further information is exposed, or as long as the incident continues to pose risk to the organization.

The short- and long-term strategies are also an important differentiation between crisis communication plans and emergency action plans. Emergency action plans address the immediate response following an emergency event. More extended planning is required to continue mitigating organizational risks as investigations and potential legal disturbances affect the organization.

In looking at survey responses and comparing the provided crisis communication plans, the results indicate clear gaps in crucial components and it seems there is a misconception of the functionality. Crisis communication plans are not clearly differentiated from emergency action plans in construction practice or the literature. Without a clear differentiation, it is likely that crisis communication plans were misrepresented throughout this study.

A broader understanding of emergency action plans and crisis communication plans is needed to best support construction organizations following a crisis event like a fatality. To help facilitate this understanding, clarifications on concept and functionality are needed. As a result, it seems imperative to offer a well-defined distinction between emergency action plans and crisis communication plans. Emergency action plans are localized standard operating procedures used to outline processes, roles, and responsibilities immediately following an emergency event. The purpose of the plan is to respond to immediate emergency needs and protect employees from imminent threat. An example of a construction emergency action plan is included in Appendix A. A crisis communication plan is the communication between stakeholders and the organization throughout the life of a crisis. The purpose of the plan is to mitigate organizational harm and promote recovery. It should be designed to address risks associated with operations and protect all aspects of the business. An example crisis communication plan is included in Appendix B. While emergency action plans can be a part of the crisis communication plan, the functionality is different. Emergency action plans should be used as a response tool when an emergency occurs. Crisis communication requires proactive planning and consideration of stakeholder attribution in both immediate response and long-term recovery. The results from this study indicate there is still room for improvement in further mitigating risks through communication strategy and planning in construction.

6. Conclusions

In construction, major injuries and fatalities are a threat to organizations and personnel. The industry has placed a large focus on preventative safety measures and management systems to help mitigate these risks, but accidents continue to occur. In the event of a fatality, research has shown that construction organizations lack effective crisis communication practices. To help improve the effectiveness of response methods and organizational continuity following major safety failures, this study aimed to identify the extent that financial, reputational, and legal consequences impact an organization following a fatal event. The study also evaluated the role of crisis communication planning in mitigating those risks. Through a survey of industry leaders, the perception of organizational impact was measured and compared to previous research. The results of this study highlighted numerous contradictions with the previous literature, which point to misunderstandings of crisis communications and the impacts of worksite fatalities throughout the construction industry. The contradictions in this case, are the major contributions of this study.

In evaluating financial burdens, the indirect costs of a fatality seem to be underrepresented in survey responses. Commentary noted that many of the impacts to people, production and morale were not accounted for in estimated costs, and compared to the past literature on the topic, reported indirect costs were lower than anticipated. While financial burdens were shown to be the most severe impact of a fatal event, the overall costs to the organization are likely underestimated and not fully comprehended as a consequence of the fatality.

It also seems likely the legal implications of a fatality were underrepresented in the study. Most organizations claimed they did not face legal implications following a fatal event. The organizational structure of project participants and organizational longevity of the responding organizations could be contributing factors as to why legal implications had a lower impact for survey participants. But legal implications should not be dismissed. The financial and reputational burdens that threatened organizations following safety failures can be detrimental and should not be underrated.

In evaluating reputational impacts on an organization, it seems likely construction leaders do not have a full understanding of reputational complexity. The crisis literature has shown organizational reputations can be negatively affected following a construction accident, yet most of the respondents in the survey stated their organization did not face reputational implications. This seems improbable given past research. It is more likely organizational leaders do not have a complete understanding of stakeholder attribution following the fatal event or the reputational effects are masked by other business factors. The reputation of a company is the perception of the publics and as organizational circumstances change, so can the reputation. Company leaders should be in-tune with internal and external perceptions of the organization before and after crisis events to truly understand changes that may disrupt operational success.

In evaluating the effectiveness of crisis communication plans, the consensus among respondents was advanced planning helped mitigate organizational risks. While it seemed there was an understanding that crisis communications can help in organizational recovery, a comprehensive understanding of critical components of a crisis communication plan seemed to be lacking. The consideration of stakeholder attribution and long-term strategic messaging are components that should be included in a crisis communication plan, but were lacking in this study. Crisis communication plans are likely collapsed with emergency action plans in practice. As a result, a differentiation between the two communication concepts was defined. Increased education and a better understanding of the function and concept of crisis communication plans will allow for more effective preparation and response methods following a fatal event.

Overall, the contradictions showcased in this study illustrate crisis communication is an area for organizational learning in the construction industry. A deeper evaluation of the impacts of worksite fatalities should be conducted with consideration of extensive indirect costs, legal repercussions, and the effects of stakeholder attribution on organizational reputation. There should be increased education on the purpose and functionality of crisis communication plans and a broader focus on response methods throughout the life cycle of a crisis to help mitigate organizational risks.

7. Practical Applications

Findings from this study should be used and considered in organizational communication and emergency response planning. While costs seemed to have the largest organizational impacts, the risk of reputational and legal damage should also be addressed through advanced communication planning. Organizational leaders should also be aware that personal perceptions of fatalities and the associated impacts on the organization may not accurately represent the extent of organizational impact. Leaders should have a heightened awareness of internal and external perceptions of the organization over time.

The consensus in this study aligns with past research that crisis communication and advance communication planning is beneficial to mitigating risks. However, organizations need to differentiate between crisis communication plans and emergency action plans to best prepare for crisis events. Comprehensive crisis plans should consider stakeholders, strategic messaging, short- and long-term strategies, in addition to the immediate emergency response procedures.

8. Limitations and Future Work

Although this study provides important contributions toward emerging crisis planning in construction, it is recognized there are limitations that must be addressed. First, the sample size was smaller compared to other research studies and may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Research and data collection related to fatalities faces unique obstacles. People who have had to emotionally or physically cope with a traumatic event can be challenging to obtain responses from about the event. Additionally, privacy, confidentiality, and organizational information concerns present barriers to data collection. Small sample sizes are continuously a challenge with research related to death [41].

Second, it is recognized that the results from this research may be susceptible to bias. The survey participants were voluntary and targeted based on their membership in an industry association. It is acknowledged that the participants may represent more “responsible” companies and distort the representation of the construction industry as a whole. Additionally, participating representatives may have expressed a form of bias when answering questions to persuade a more positive image of their own organization. While survey results were anonymous, discussions of safety failures, specifically fatalities, and subsequent organizational failure can be difficult to address. Personal bias may have been present as a protective mechanism and results may not accurately represent the full scale of organizational impact. Additionally, some of the conclusions drawn from this study are based on respondent’s perceptions and not concrete, objective organizational data.

Third, the survey participants were members of active construction companies following a fatal event. Any organizations that faced terminal damages or ceased operations due to legal, reputational, or financial pressures were not included in the survey results. This limits the impact results to a threshold that did not extend past organizational capacity. The results are likely skewed and do not represent the significance of impacts that could result in ceased operations.

Future work should build upon the results of this study and improve the data by further investigating the factors that impact organizations following crisis events. Research should include collection of objective organizational data following a fatal event from a larger sample size to help strengthen the validity of the subjective measures provided in this study. Rather than a survey, it may be beneficial to explore public sources like litigation results, OSHA reports, or publicly traded company financial statements to reduce personal bias and subjectivity.

Future work would also benefit from interviews of multiple stakeholder groups impacted by a fatality to provide a diverse perception and give a more wholistic view of reputational consequence, the effects of morale, and employee retention. Interviews could target internal employees, project partners, shareholders, industry competitors, suppliers, and the public. It would also be worthwhile to evaluate other high-risk industries such as mining, manufacturing, and oil and gas to compare crisis impacts across multiple industries.

This study suggests organizational leaders may not be fully aware of external stakeholder attributions and the reputational impacts of a fatality. An evaluation of how internal perceptions diverge from external stakeholder views would help illustrate the significance of stakeholder attribution and its implication to crisis management planning. It would also be beneficial to understand how construction companies are systematically measuring reputational damage, if at all.

Lastly, the construction industry could benefit from an analysis of the potential impacts of emerging technologies and artificial intelligence on construction safety management systems and crisis response. The use of technology advances can provide more effective risk perception and more accurate safety measures, enhancing the effectiveness of monitoring and early warning signs [42]. The use of emerging technologies may offer opportunities to close the gaps in individualized risk perception and formulate crisis response plans with less resources than previously required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H. and A.L.; methodology, M.N. and K.P; validation, K.H. and M.N.; formal analysis, K.H.; investigation, K.H.; resources, K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H.; writing—review and editing, M.N., K.P. and A.L.; visualization, K.H.; supervision, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to the Roofing Alliance, the Beavers Charitable Trust, and the Arizona Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association and their members for the support and contributions to this research. The involvement and insight on behalf of the participating construction organizations is highly appreciated, especially considering fatalities in the work place can be a sensitive topic and difficult to revisit.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Example Emergency Action Plan

Appendix A.1. Emergency Action Plan

The purpose of this plan is to provide an Emergency Action Plan (EAP) specific to each job site. It is intended to guide employees and project partners in responding to environmental, health and safety emergencies. In times of emergency, it is important to maintain control of the site and coordinate appropriate responses in a timely and efficient manner. Processes and procedures should be followed to reduce additional harm to people, equipment, and the organization.

Appendix A.2. Action Plan

Appendix A.2.1. Phase 1—Preparation

- Appoint members of the Emergency Action Plan Response Team (EAPRT). This team should include:

- ○

- Site Manager;

- ○

- Site Safety Manager;

- ○

- Emergency Response Coordinator;

- ○

- Muster Point Coordinator;

- ○

- Incident Administrator;

- ○

- Site Security;

- ○

- Site Medical Staff.

- The emergency action plan should be communicated to all site personnel prior to their first day of work.

- An emergency drill should be conducted at each project site at least every six months with support from local emergency response groups.

Appendix A.2.2. Phase 2—Incident Response & Responsibilities

- Initial Incident Respondent Responsibilities

- ○

- Call 911;

- ○

- Notify site manager.

- Site Manager Responsibilities

- ○

- Activate EAP and notify members of the EAPRT;

- ○

- Suspend work as required;

- ○

- Notify project owners and partners as required;

- ○

- Inform all site personnel of communication procedures;

- ▪

- Yes. Only appointed spokespersons will communicate with the media and external stakeholders;

- ○

- Only when safe to do so, release personnel from muster points or evacuation areas;

- ○

- Only when safe to do so, communicate the resumption of construction operations to site personnel, owners, and project partners.

Appendix A.2.3. Site Safety Manager Responsibilities

- Evacuate all persons from areas with dangerous conditions and immediate threats or hazards;

- Provide immediate safety instructions including:

- ○

- Evacuation routes and requirements;

- ○

- Restricted areas;

- ○

- Any additional exposures or hazards;

- Report incident to OSHA within 24 h;

- Report incident to additional regulatory agencies as required.

Appendix A.2.4. Emergency Response Coordinator

- Notify emergency services. Provide the following information:

- ○

- Your name;

- ○

- Site location and access points;

- ○

- Nature of the emergency;

- ○

- Any known injuries and the severity if known;

- Ensure site access for emergency vehicles;

- Communicate with emergency services throughout incident response;

- Serve as command center liaison and main point of contact for all response units until the emergency is mitigated.

Appendix A.2.5. Muster Point Coordinator

- Account for all personnel and visitors;

- Communicate head counts to Site Manager and identify any missing individuals;

- Communicate direction and evacuation information to site personnel;

- Do not allow personnel to leave muster points until directed to do so by Site Manager.

Appendix A.2.6. Incident Administrator

- Send emergency alert to site personnel via push notification;

- Notify corporate Crisis Management Team;

- Identify victims and witnesses;

- Secure witnesses and keep them separate from one another;

- Obtain written witness statements as soon as possible;

- Preserve the scene to aid in authority investigations;

- Identify any personnel that will require drug/ alcohol testing as required;

- Once safe to do so, take photos of incident area.

Appendix A.2.7. Site Security

- Secure the project site;

- Protect the site from public access;

- Keep ingress and egress access points clear for emergency vehicles;

- Allocate holding area outside the perimeter of the site for media/ external stakeholders as required.

Appendix A.2.8. Site Medical Staff

- Administer first aid and CPR as required—only if safe to do so;

- Stabilize any injured personnel until first responders arrive on site—only if safe to do so;

- Appoint company representatives to accompany any person sent to the hospital. Appointed persons should be medically trained and able to obtain work place related injury updates from medical staff.

Appendix A.3. Additional Resources

Appendix A.3.1. Local Emergency Contacts

- 911;

- Local Fire Department—address and phone number;

- Local Police Department—address and phone number;

- Nearest hospital—address and phone number;

- Local poison control center—address and phone number.

Appendix A.3.2. Emergency and Incident Communication

Unapproved comments and statements can inadvertently solidify our organization’s position in an incident. Employee comments and statements, verbal and written (email/text) can be used in legal proceedings, and may impact the future legal and reputational status of the organization. It is important that only approved statements are shared by authorized company representatives. Employees should not engage with external sources, media representatives, or social media platforms regarding incident information or details.

Appendix A.3.3. Maps

- Site map/project logistics plan;

- Map of emergency resources including but not limited to:

- ○

- AED;

- ○

- Fire extinguishers;

- ○

- First aid kits;

- ○

- Spill kits;

- ○

- Eye wash stations;

- ○

- Fire hydrants;

- Map of emergency locations including but not limited to:

- ○

- Evacuation routes;

- ○

- First responder access points;

- ○

- Muster points;

- ○

- Incident command center;

- ○

- Medical treatment centers.

Appendix B. Example Crisis Communication Plan

Appendix B.1. Major Injury or Fatality—Crisis Communication Plan

A well-developed crisis communication plan is critical for managing a construction site in the event of an emergency. By maintaining clear communication and coordination, the impact of the crisis can be minimized, and the safety of all involved can be maximized. This plan should be reviewed regularly, practiced through drills, and adapted to meet the evolving needs of each job site.

Unapproved comments and statements can inadvertently solidify our organization’s position in an incident. Employee comments and statements, verbal and written (email/text) can be used in legal proceedings, and may impact the future legal and reputational status of the organization. It is important that only approved statements are shared by authorized company representatives. Employees should not engage with external sources, media representatives, or social media platforms regarding incident information or details.

Examples of When to Initiate This Plan

- Worker(s) fatality;

- Major injury to worker(s).

Appendix B.2. Action Plan

Appendix B.2.1. Phase 1—Pre-Crisis

- Appoint a Crisis Management Team (CMT) that will be responsible for executing this plan. The CMT should include members from the following departments at a minimum:

- ○

- Legal;

- ○

- Human Resources (HR);

- ○

- Public Relations (PR);

- ○

- Executive Leadership;

- ○

- Site Project Manager;

- ○

- Site Safety Manager;

- ○

- Subject Matter Experts (SME);

- Site and executive management to identify project stakeholders that will require communications during a crisis event. See example stakeholder list in additional resources.

- Site and executive management to evaluate company reputation and legitimacy every 12 months to anticipate any negative public attribution that may arise during a crisis event.

- Site management to implement crisis training at worksite.

- Safety department to facilitate crisis/emergency drill every 6 months.

- Create emergency action plan including appointment of site spokespersons and calling tree/ emergency contact list.

Appendix B.2.2. Phase 2—Stabilize and Immediate Response

- Call 911.

- Initiate emergency action procedures as outlined in the site-specific Emergency Action Plan including:

- ○

- Suspend work and secure site;

- ○

- Notify emergency services;

- ○

- Notify members of CMT;

- ○

- Provide immediate safety instructions;

- Identify victims.

- ○

- Do not make speculations of a fatality. Only a trained professional can make a legal pronouncement of death. Victim status should not be shared by anyone outside of the CMT and will only be communicated once confirmed by legal representatives and next of kin have been notified.

- ○

- Due to privacy concerns, personnel impacted by the event will not be named before the family has been fully notified and will only be named if deemed necessary by the CMT.

- Any person sent to the hospital should be accompanied by a company representative that is trained and able to obtain workplace related injury updates from medical staff.

- Site appointed spokesperson to provide immediate incident information and communication protocols to worksite employees.

Appendix B.2.3. Phase 3—Internal and External Communication

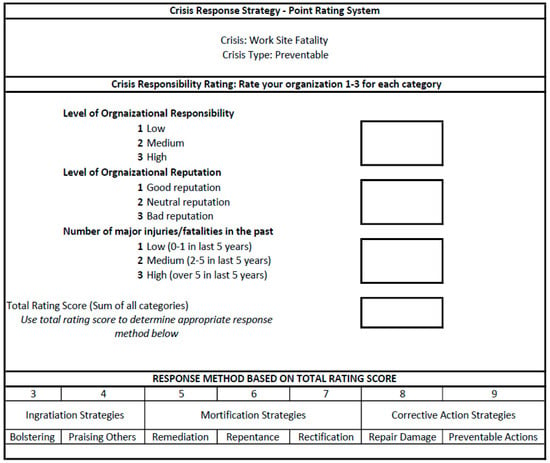

- CMT will meet and determine communication strategy based on known incident information and perceived attribution to ensure transparency and consistency. See additional references for crisis response rating example.

- Appointed CMT spokesperson will conduct victim notifications in person and communicate directly with victim families.

- CEO will provide incident information and talking points to internal employees.

- Site project manager will provide incident information to project partners, owners, and subcontractors.

- Site safety manager to provide incident information and documentation to regulatory agencies.

- HR to initiate on site employee assistance and grief support. Resources will be communicated to all internal employees and site partners.

- HR will provide internal contact person to help coordinate family wishes and avoid direct contact between employees and victim families.

Appendix B.2.4. Phase 4—External/Media/Public Communication

- PR team will provide incident information to media and field all inquiries. Only dedicated PR spokespersons are permitted to speak to media representatives.

- PR team will communicate incident and investigation information to special interest groups, unions, non-project customers, suppliers and other stakeholders as required.

Appendix B.2.5. Phase 5—Recovery and Continued Communication

- CEO will provide incident and investigation updates to internal employees as the situation develops. Talking points will be provided if deemed necessary.

- PR team will provide investigation and event details to external stakeholders and media contacts as required.

- CEO and PR team will communicate additional details as needed. This may include but is not limited to:

- ○

- Rectification measures or corrective actions;

- ○

- Production schedules;

- ○

- Operational delays;

- ○

- Investigation results;

- ○

- Information required for legal or regulatory compliance.

- CMT to consider memorialization or tribute as appropriate based on circumstances and organizational attribution.

Appendix B.2.6. Phase 6—Evaluation and Improvement

- CMT to evaluate the effectiveness of the crisis communication strategy 1 month, 6 months and 12 months after the fatal event. With the help of site representatives, the team should identify successes, failures, and improvement opportunities. Crisis plan to be adjusted based on learnings.

- Crisis communication plan to be re-evaluated every 5 years at minimum.

- Provide additional training as required.

Appendix B.3. Additional Resources

Table A1.