2.2. State-of-the-Art

In this section, the State-of-the-Art related to virtual assistants is explored within the NAIA framework, focusing on user support across different types of interaction, whether through text, avatars, or other modalities, and examining how these assistants perform within their respective contexts.

First of all, the study presented in [

18] presented AIIA (Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Intelligent Assistant), a virtual teaching assistant (VirtualTA) designed for personalized and adaptive learning in higher education. The system integrates GPT-3.5 for natural language processing, OpenAI embeddings, and Whisper + pyannote for transcription and speaker diarization of recorded lectures. Built with a NodeJS backend, PostgreSQL, React, and Canvas LMS integration, AIIA provides a wide range of student services: flashcards, automated quiz generation and grading, coding sandbox execution, summarization, and context-aware conversations. For instructors, it supports auto-evaluation of assignments, homework detection, and automated question generation. Evaluations demonstrated the system’s potential to reduce cognitive load, improve engagement, and support both students and instructors. Future directions include adaptive learning algorithms, multimodal integration, gamification, and ethical safeguards.

The research presented in [

19] proposed DataliVR, a virtual reality (VR) application designed to improve data literacy education for university students. The system integrates immersive VR scenes with a ChatGPT-powered virtual avatar with speech-to-speech (Whisper) and text-to-speech (Oculus Voice SDK) for conversational assistance. The chatbot improved user experience and usability but unexpectedly led to slightly lower learning performance, likely due to distraction or reliance on assistance. The work highlights the promise of VR+LLM integration for education but stresses the need for careful design to balance guidance with self-directed learning.

The study in [

20] introduced EverydAI, a multimodal virtual assistant that supports everyday decision-making in cooking, fashion, and fitness. The system integrates GPT-4o mini for language reasining, YOLO + Roboflow for real-time object detection, augmented reality, 3D avatar (Ready Player Me + Mixamo), voice interaction (Web Speech API + ElevenLabs), web scraping, image generation, and deployment on AWS with Flask and Three.js. Users interact via text, voice, or avatars to receive personalized, context-aware recommendations based on the available resources (ingredients, clothing, equipment). The assistant effectively reduced decision fatigue and improved task efficiency.

Work developed in [

21] proposed a Virtual Twin framework that integrates 3D avatar generation, real-time voice cloning, and conversational AI to enhance virtual meeting experiences. The system employs Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) + Triplane neural representations for photorealistic avatars, Tacotron-2 + WaveRNN for natural voice cloning, and a context-aware LLaMA 3.1 Instruct 8B model (fine-tuned on the AMI Meeting Corpus) for coherent, multi-turn dialogue. User feedback indicated the system is 85% more engaging than conventional assistants. Limitations remain in gesture fluidity, including latency and data privacy. The framework has applications in business, education, and healthcare, aiming to provide more immersive, human-like virtual collaboration.

Reference [

22] introduced HIVA, a holographic 3D voice assistant to improve human–computer interaction in higher education. HIVA uses a Pepper’s Ghost-style pseudo-holographic projection combined with an animated 3D mascot and Russian-language NLP models for natural dialogue. The assistant provides information about admissions, departments, fees, student life, and university services, functioning as an alternative to website or staff inquiries. Its architecture integrates speech-to-text, suggestion classification (Multinomial Naïve Bayes), short-answer subsystems, and a Telegram chatbot. HIVA has been deployed since July 2021, handling over 7000 user requests, with NLP classification accuracy ranging from 74–97%. Future work focuses on expanding datasets and enhancing speech recognition for noisy conditions.

The study in [

23] proposed a 3D avatar-based voice assistant powered by large language models (LLMs) to enhance human–computer interaction beyond traditional assistants like Alexa. The system integrates speech recognition, emotion analysis, intent classification, text-to-speech, and Unity-based 3D avatar rendering. Results show a 40% rise in task completion and a 25% reduction in user frustration, confirming improved engagement through natural language dialogue and a lifelike 3D avatar. Future directions include adding gesture/emotion recognition, multimodal interactions, and AR integration for richer experiences.

Reference [

24] proposed MAGI, a system of embodied AI-guided interactive digital teachers that combines large language models (LLMs) with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and 3D avatars to improve educational accessibility and engagement. MAGI introduces a hybrid RAG paradigm that organizes educational content into a hierarchical tree structure for accurate knowledge retrieval, mitigating LLM hallucinations. The system pipeline integrates Llama 3.8 B as the backbone LLM and a text-to-speech (TTS) module. A web interface allows learners to interact with customizable 3D avatars. MAGI shows promise in bridging educational gaps and providing high-quality, personalized digital teaching experiences at scale.

The research presented in [

25] shows ELLMA-T, a GPT-4-powered embodied conversational agent implemented in VRChat to support English language learning through situated, immersive interactions. The system integrates Whisper speech-to-text, OpenAI TTS, Unity avatars, and OSC-based animation control for real-time dialogue, role-play, and adaptive scaffolding. ELLMA-T generates contextual role-play scenarios (supermarket, café, interview) and provides verbal + textual feedback.

Reference [

26] introduced a speech-to-speech AI tutor framework that integrates noise reduction, Whisper ASR, Llama3 8B Instruct LLM, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), Piper-TTS, and Wav2Lip avatar into a fully edge-deployed system running on AI PCs. The system supports dynamic conversational learning with an animated avatar while ensuring low-latency, multimodal interaction. Results highlight effective integration across modules, with strengths in response accuracy and avatar throughput, though latency optimization remains a challenge.

The research in [

27] developed UBOT, a virtual assistant that achieved significant improvements in institutional response times. The system implements Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology to provide contextually relevant responses using institution-specific information, demonstrating the effectiveness of domain-focused AI systems in educational settings.

The development of domain-specific virtual assistants across various sectors has provided crucial insights into role-based specialization approaches. In museum environments, DEUSENS HYPERXPERIENCE SL [

28] developed the Alice Assistant, emphasizing natural communication through Speech-To-Text technology and digital avatar delivery. The system creates intuitive visitor interactions through voice-based communication and focuses on enhancing museum experiences.

The work in [

29] addressed an intelligent conversational agent for museum environments using Google Cloud Speech-To-Text, RASA for Natural Language Understanding, and SitePal for avatar-based speech synthesis. Their implementation demonstrates the technical integration of speech processing with avatar animation systems.

The research in [

30] created a context-aware virtual assistant designed to adapt across various usage scenarios while maintaining natural dialogues. The system demonstrates versatility in handling multiple domains without requiring specialized configurations for different use cases.

The contribution in [

31] on the ALICE Chatbot demonstrated how a single assistant architecture could handle multiple specialized knowledge domains (tourism, healthcare, sports) while maintaining a consistent user experience through visual representation. Their implementation maintains a consistent user experience through visual representation across different domains.

Several implementations demonstrated the importance of extending virtual assistants beyond conversational interaction to functional automation. Garibay Ornelas [

32] implemented a virtual assistant for a Mexican airline operating through WhatsApp and web interfaces, specifically addressing customer service bottlenecks through automated interactions.

The research [

33] developed healthcare-focused digital avatar systems for patient follow-up care and appointment management. The system demonstrates role-specific functionalities in healthcare contexts, focusing on scheduling and communication capabilities.

The contribution in [

34] is an AI-based hospital assistant that improves patient information access, addressing critical delays in healthcare settings by providing timely responses about medical processes and patient status updates. Their focus centers on reducing information access delays and improving patient information accessibility.

The study in [

35] implemented a tourism-focused virtual assistant that enhances visitor experiences by providing precise information about operating hours, local events, points of interest, and gastronomy options. The system demonstrates success in domain-specific information delivery.

The work in [

36] developed Edith, a university-focused virtual assistant using IBM Watson Assistant that efficiently resolves academic process queries across multiple interfaces. The system demonstrates multi-interface deployment capabilities and focuses on streamlining university-related information delivery for students and faculty.

The research in [

37] proposed a Computer Vision-enhanced virtual assistant for higher education students in specialized disciplines. Their system integrates visual processing capabilities to provide specialized support that extends beyond traditional text-based interactions.

The authors in [

38] implemented an AI assistant supporting engineering students’ thesis development with specialized tools for enhancing research methodology. Their system combines conversational AI with specialized academic functions.

The [

39] developed an AI-powered career guidance system that analyzes prospective students’ profiles to recommend suitable higher education paths. This work demonstrated the value of personalized AI assistance in academic contexts.

The research in [

40] proposed an AI-based instructor for motor skill learning in virtual co-embodiment, demonstrating that virtual instructors can effectively replace human instructors while maintaining or improving learning efficiency. Their research validated the potential for AI-driven personalized instruction.

Recent advances in knowledge-enhanced conversational systems provided crucial insights for NAIA’s information processing capabilities. Mlouk and Jiang [

41] developed KBot, a chatbot leveraging knowledge graphs and machine learning to improve natural language understanding over linked data. The system provides multilingual query support and demonstrates improved accuracy through structured knowledge integration.

Finally, the reference [

42] developed AIDA-Bot, which integrates knowledge graphs to improve natural understanding within the scholarly domain. The system demonstrates the capability to answer natural language queries about research papers, authors, and scientific conferences, focusing specifically on academic research assistance.

Table 1 lists all the studies mentioned above, summarizing all the main characteristics such as work, impact, and area.

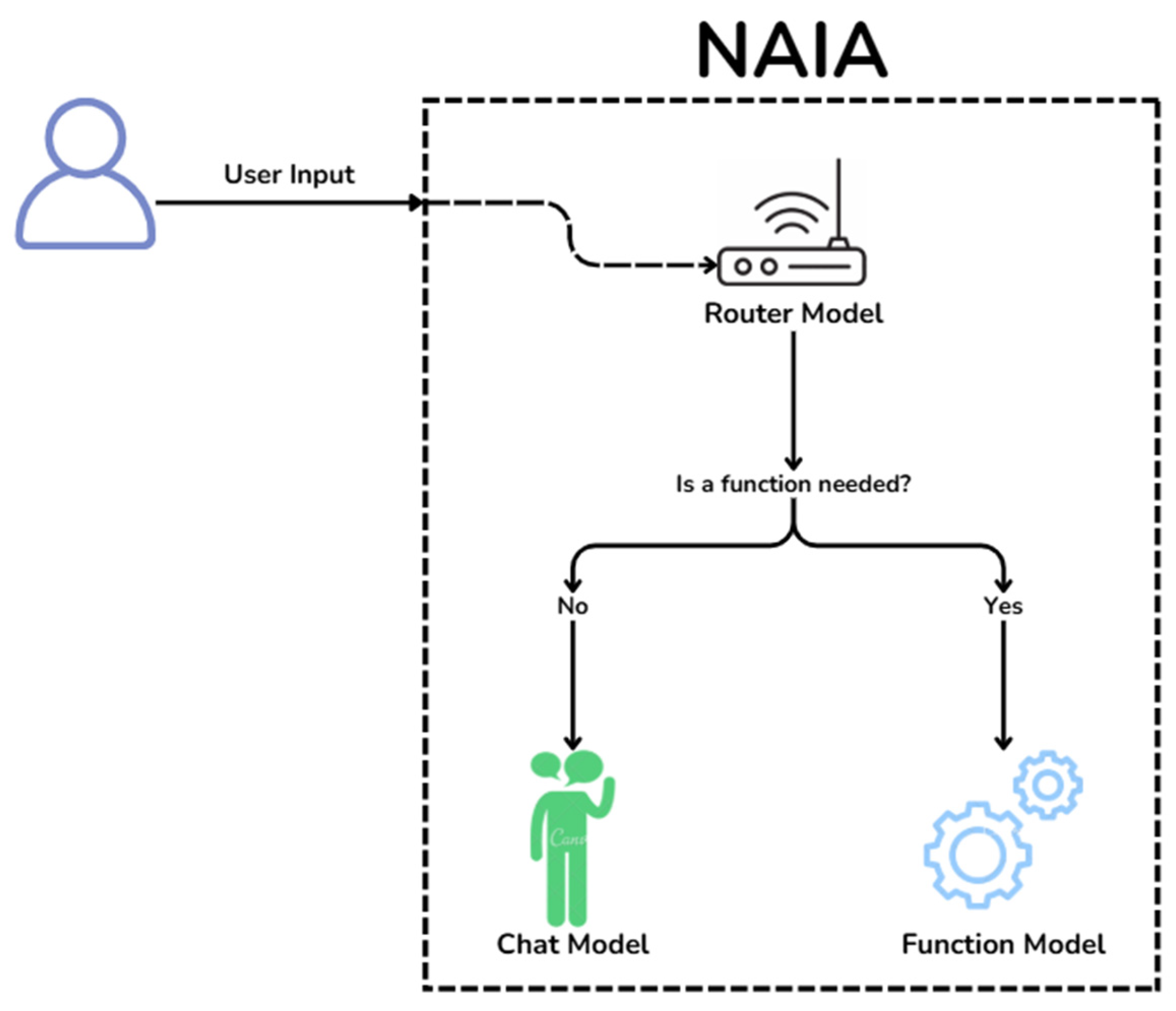

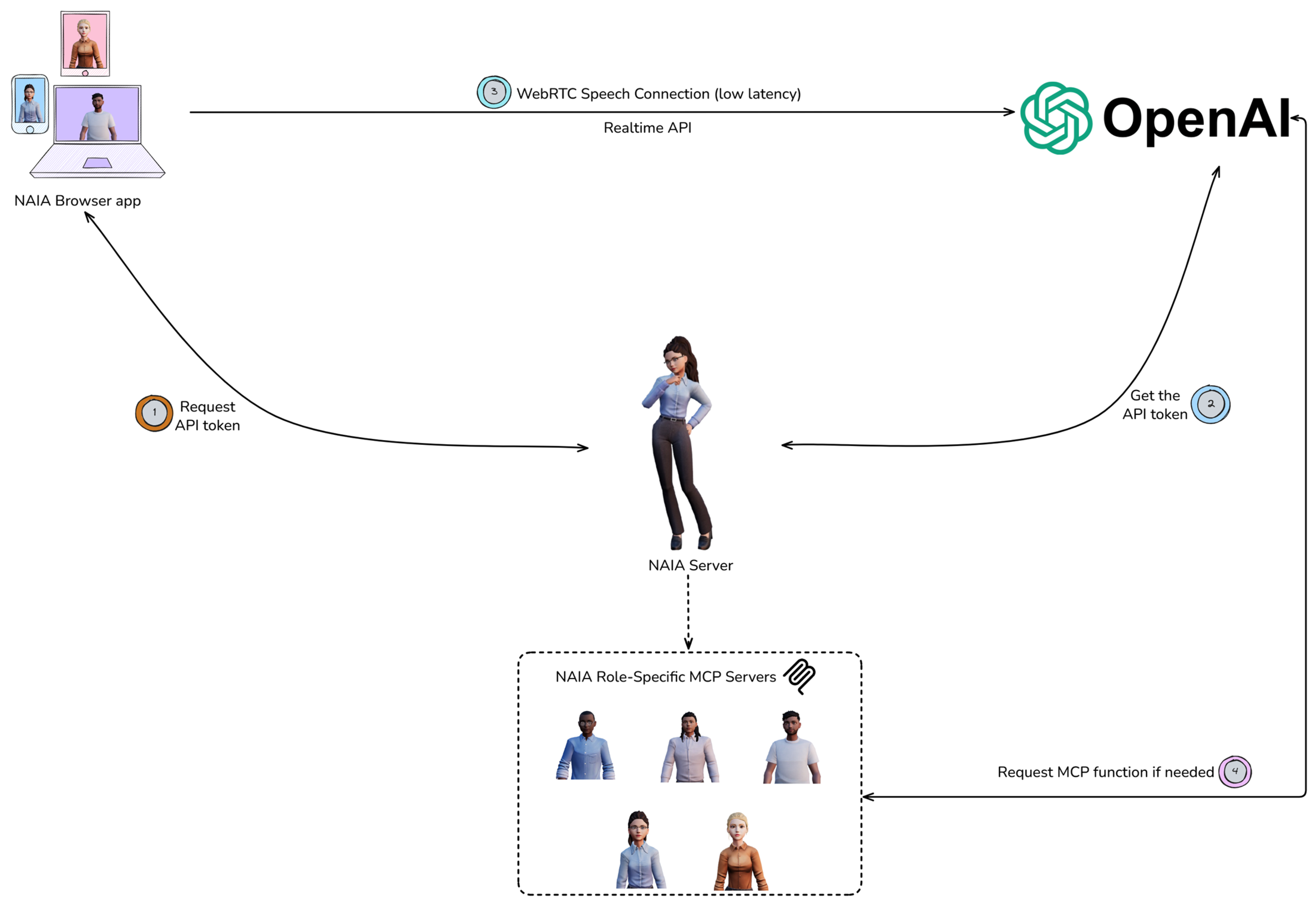

To complement the tabular overview of the reviewed systems, a concise visual comparison is introduced in

Figure 2. This representation groups a selected subset of assistants according to their main interaction channels and underlying technological capabilities, providing a clearer perspective on how different approaches relate to one another and how NAIA is positioned within this landscape.

The visualization highlights the diversity of technological directions explored across recent virtual assistant platforms. Several systems combine multiple interaction channels such as voice, avatar-based interfaces, VR or AR environments, computer vision analysis, or structured knowledge sources, which reflects a broader trend toward increasingly multimodal and context-aware solutions. Although these assistants originate from distinct application categories, including education, tourism, healthcare, and knowledge management, they share a common interest in integrating richer modes of interaction with more capable reasoning mechanisms. Within this landscape, NAIA aligns with the direction observed in current developments and distinguishes itself through its simultaneous support for text, voice, and avatar-based interaction, together with retrieval augmented access to institutional information and full integration with university systems. This configuration positions NAIA as a comprehensive academic platform built upon the same technological tendencies identified across the reviewed work.