Theoretical Analysis of Dynamic Effects of Supply Chain Concentration on Inventory Management Performance: A System Dynamics Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How can the limitations of traditional static research be mitigated to permit a dynamic analysis of the impact of the SCC on IMP?

- (2)

- Do linear growth and random demand models yield identical relationships between the SCC and the IMP? If not, what are the differences?

- (3)

- How can the integration of life-cycle stages be used to reveal the differences in the impact of the SCC on the IMP across different enterprise development stages?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supply Chain Concentration

2.2. Inventory Management Performance

2.3. The Association of SCC with IMP

3. Methodology

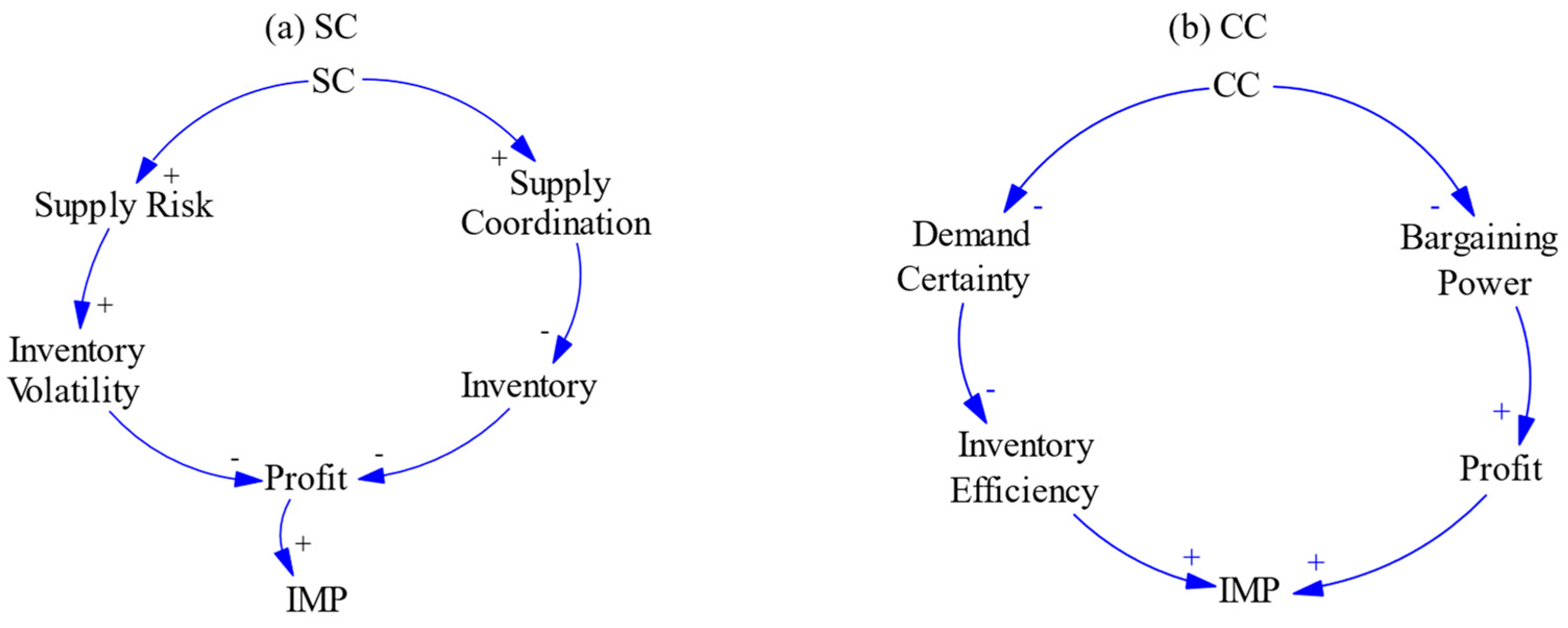

3.1. Analysis Methods for Influence Path of SCC on IMP

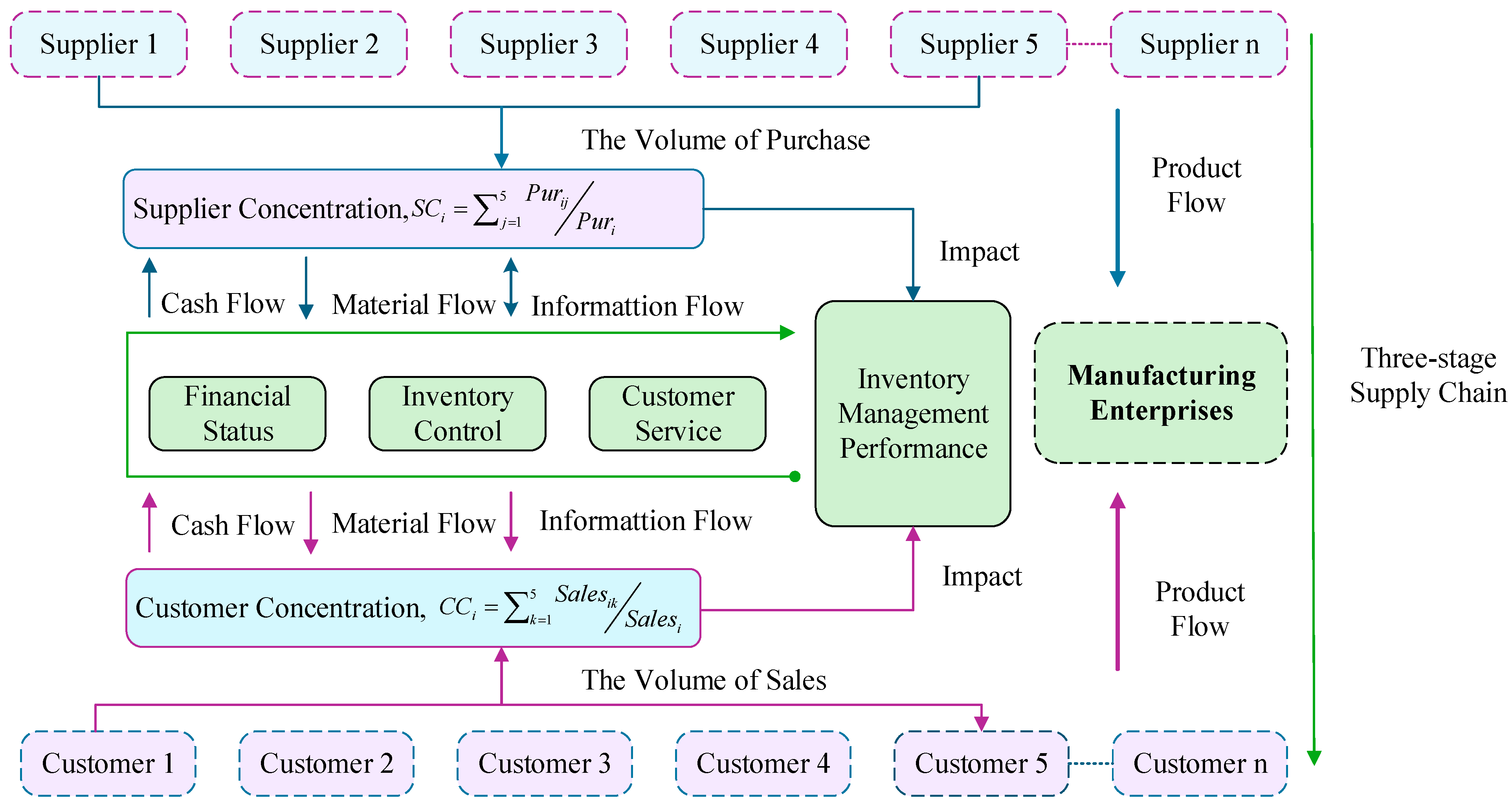

3.1.1. Quantifying the SCC

3.1.2. Quantifying the IMP

3.1.3. Interaction Between SCC and IMP

3.2. Construction of System Dynamics Model

3.2.1. Fundamental Assumptions

- (1)

- The model is treated as one kind of product converted from one kind of raw materials. The multiple materials situations can be decomposed into multi-BOMs and multi-sourcing strategies. The model is considered to be a product that is converted out of a single type of raw material. By this simplification, we can easily isolate the effects of SCC on inventory management without complicating the relationships with interactions with the multi-product, which can confound causal relationships. The multi-product situation would also be resolved in future research through the breakdown of the latter into multi-BOMs and multi-sourcing [38].

- (2)

- The possible decrease in demand can be avoided by early warnings and adjustable production strategies. It is assumed that the demand for products in the market will grow consistently with time. This assumption is differentiated by the trends in historical demands of the furniture producing business and guarantees model stability. It allows the simulation to replicate the effects of the SCC on IMP in normal operation conditions, and the effect of the sudden market shocks is not considered. In extended studies, a scenario analysis of the demand change can be implemented [24].

- (3)

- The model fails to consider such extreme situations as natural calamities or epidemics. It is concerned with the study of normal operation conditions and inherent feedback requirements between the SCC and IMP. Stochastic modeling would entail additional inclusion of extreme events, which are not within the borders of the current study [28].

- (4)

- The manufacturing enterprise communicates with upstream raw material suppliers and downstream customers, and the whole chain has a three-stage structure. The supply chain is presented in the form of a three-stage system, which includes upstream suppliers, manufacturers and downstream customers. Such a structure is reminiscent of the common countenance in the target industry, permitting the model to capture the major details and material and financial shifts and retain computational triviality. It also maintains the crucial feedback processes that are needed to investigate the coevolutionary processes between the SCC and IMP [39].

- (5)

- There is no significant regulatory or contractual anomaly in the operation of all enterprises and supply chain partners. The first assumption is that the modeled relationships will imply typical patterns of operations; the results of the simulation are more generalized in the framework of the manufacturing sphere [18].

- (6)

- The initial conditions of the system variables, such as a level of inventory, work-in-process and total business, are established through the historical data of the chosen Chinese manufacturers. This makes the model begin with real-world conditions and enables the findings to be produced by observations to be empirically checked against the results [11].

3.2.2. Model Parameters

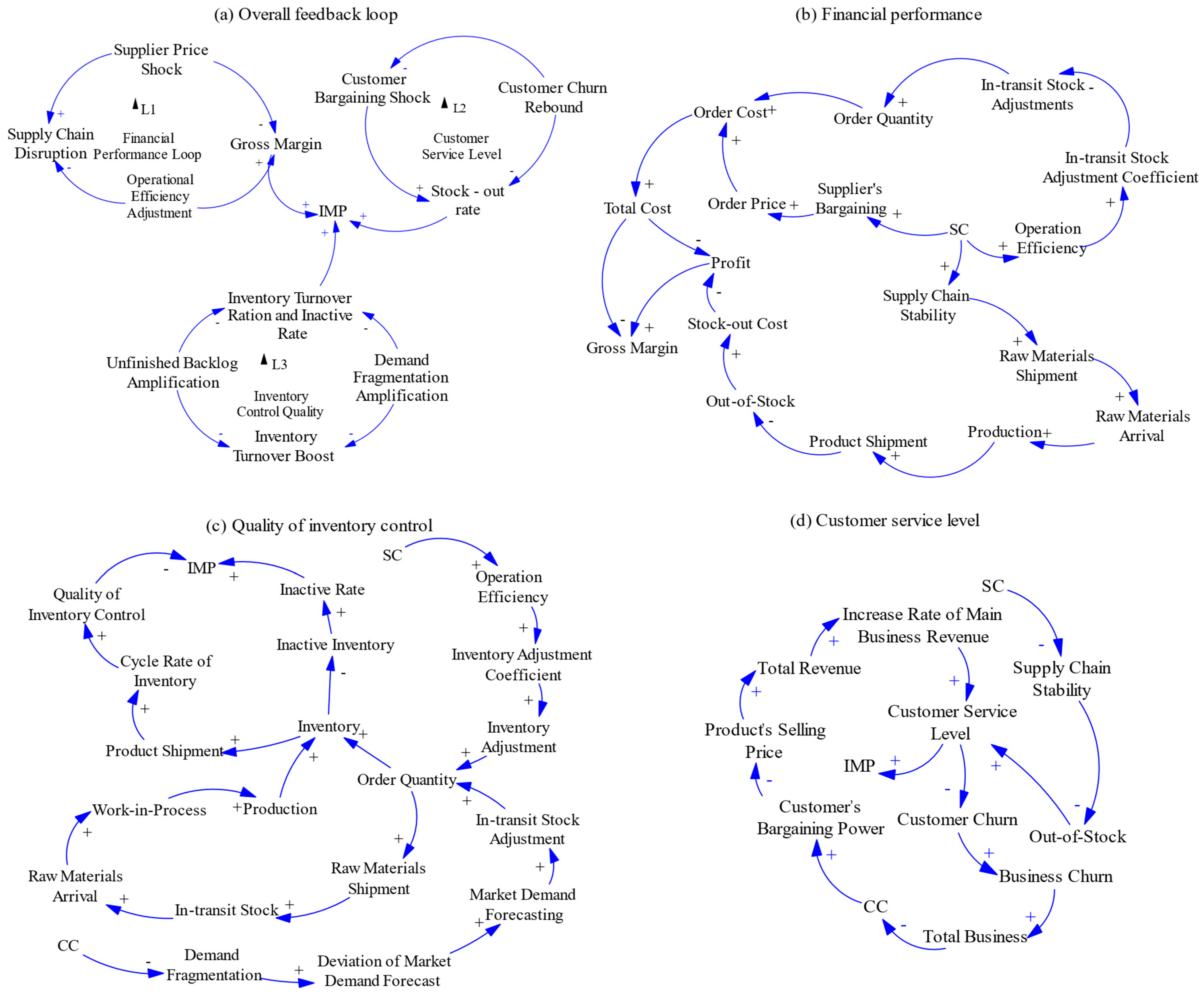

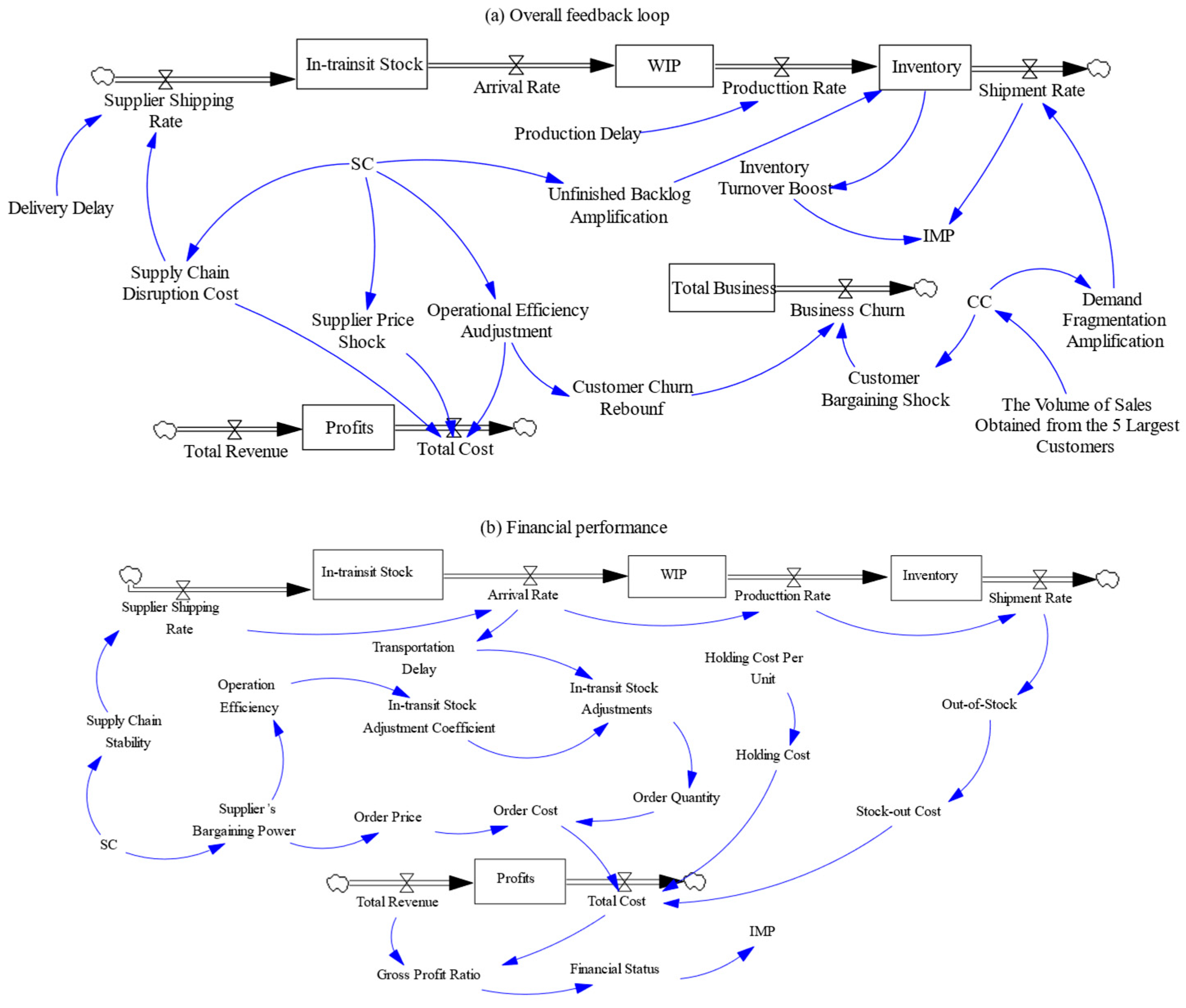

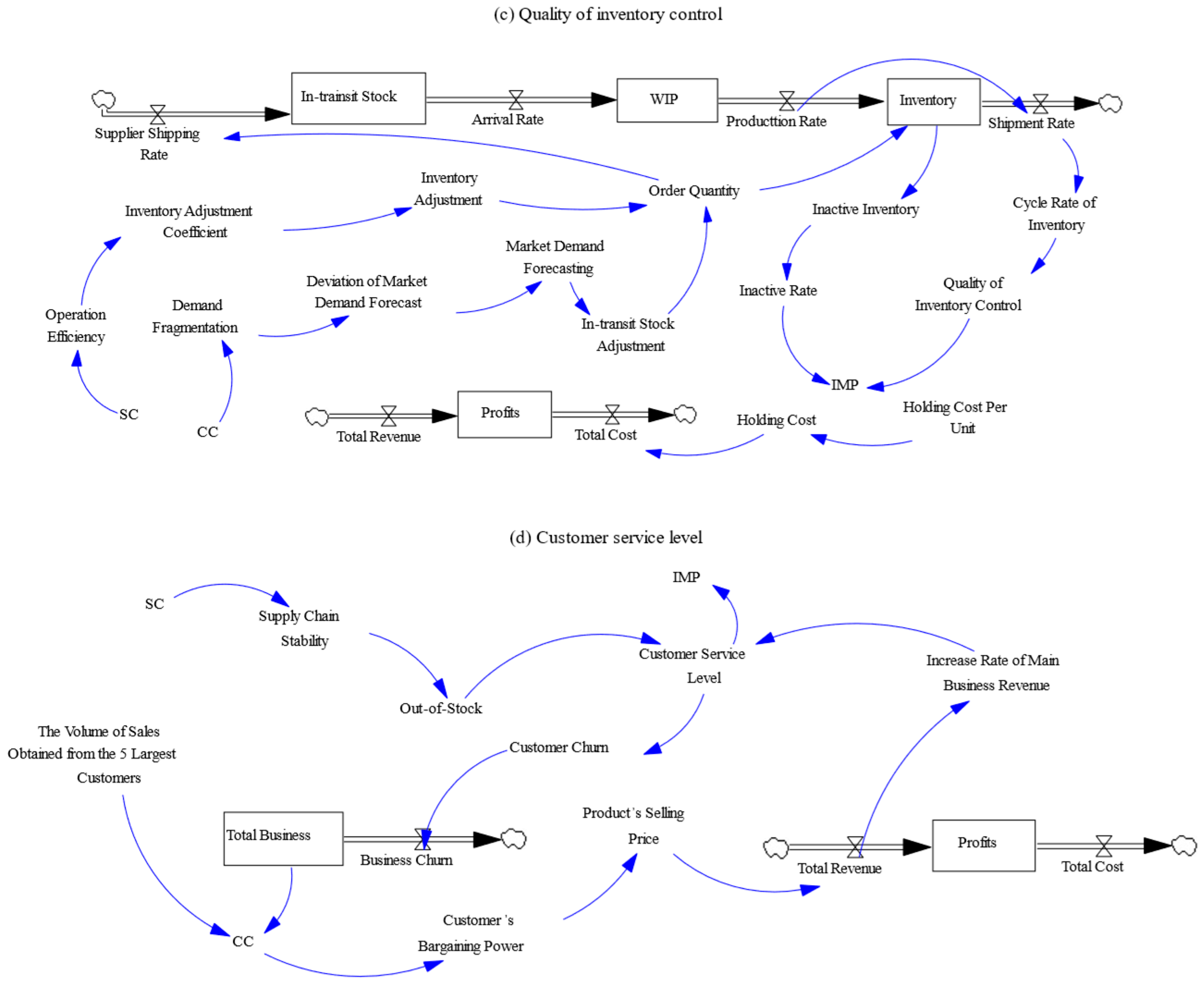

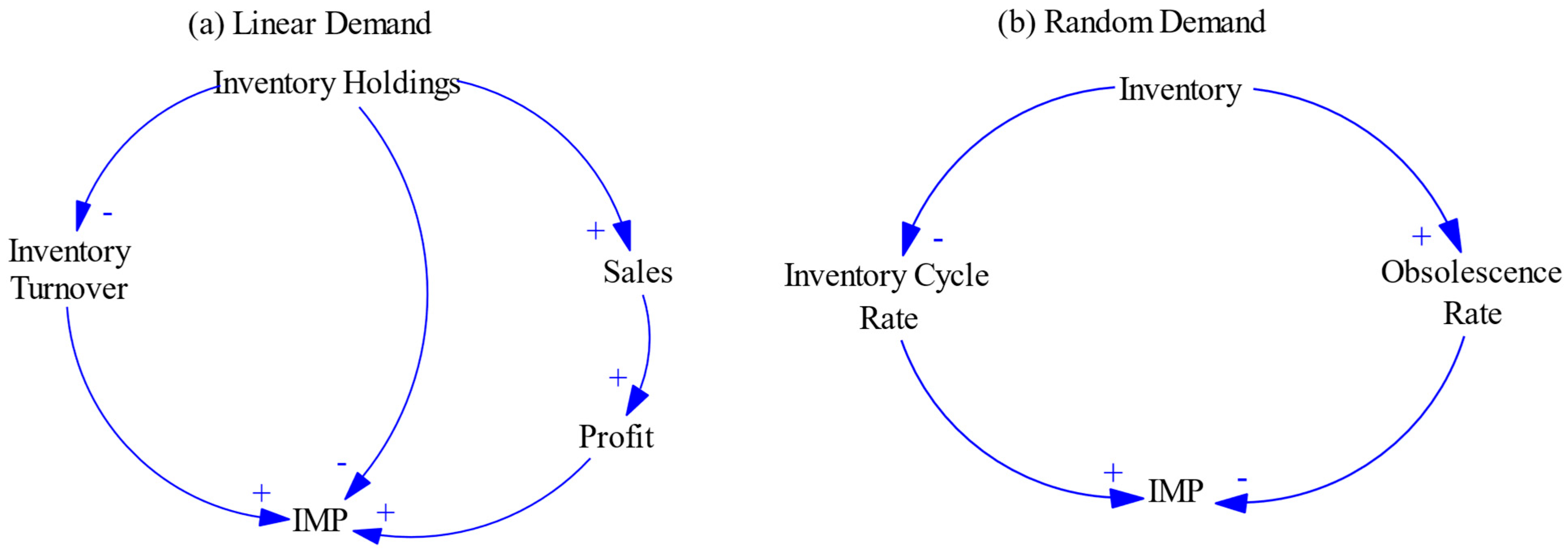

3.2.3. Causal Loop Diagram and Stock and Flow Diagram

3.2.4. Main Equations

4. SD Model Validation

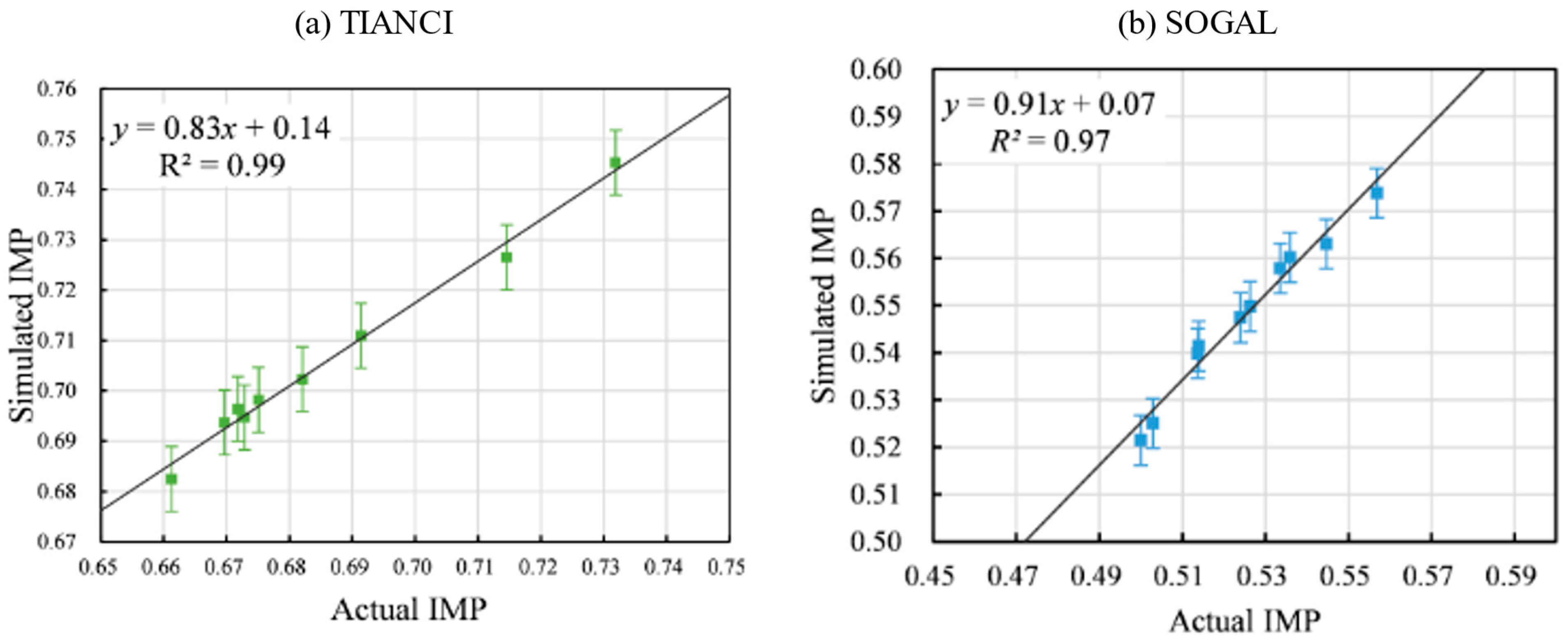

4.1. Model Validation Under Linear Growth Demand Pattern

4.2. Model Validation Under Random Demand Pattern

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

5.1. Simulation of Basic Scenario

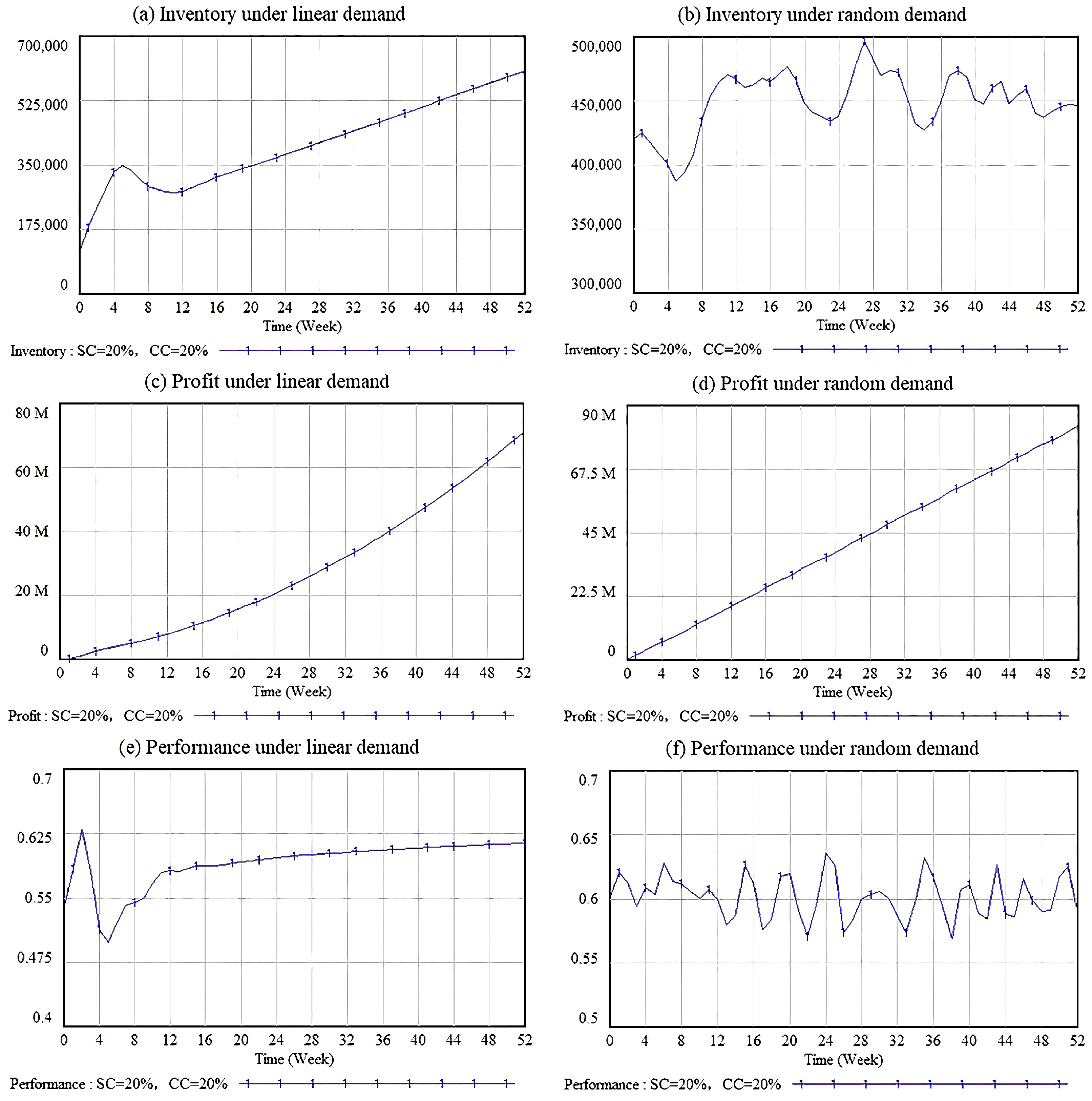

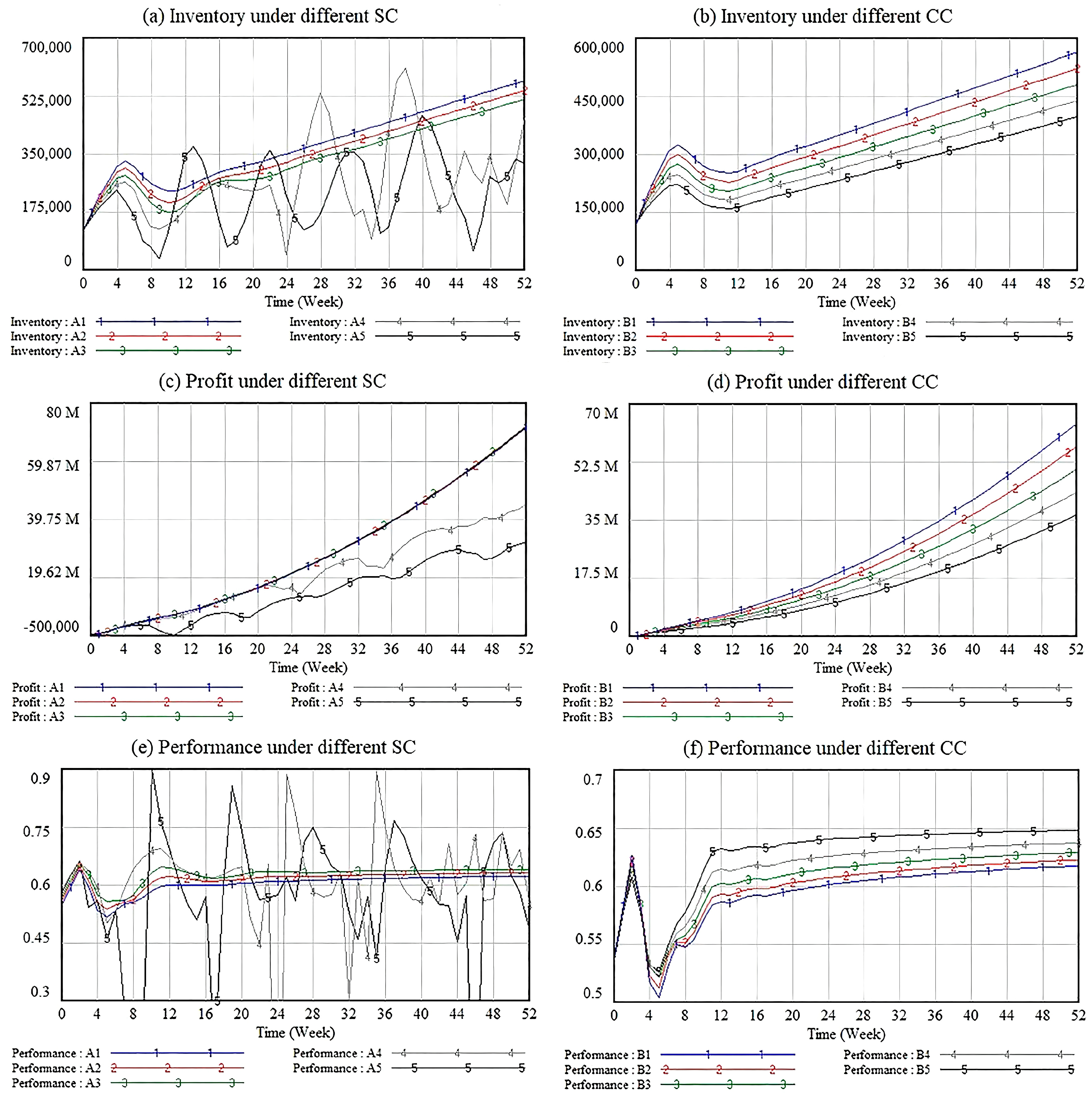

5.1.1. Simulation of Basic Scenario Under Linear Growth Demand Pattern

5.1.2. Simulation of Basic Scenario Under Random Demand Pattern

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

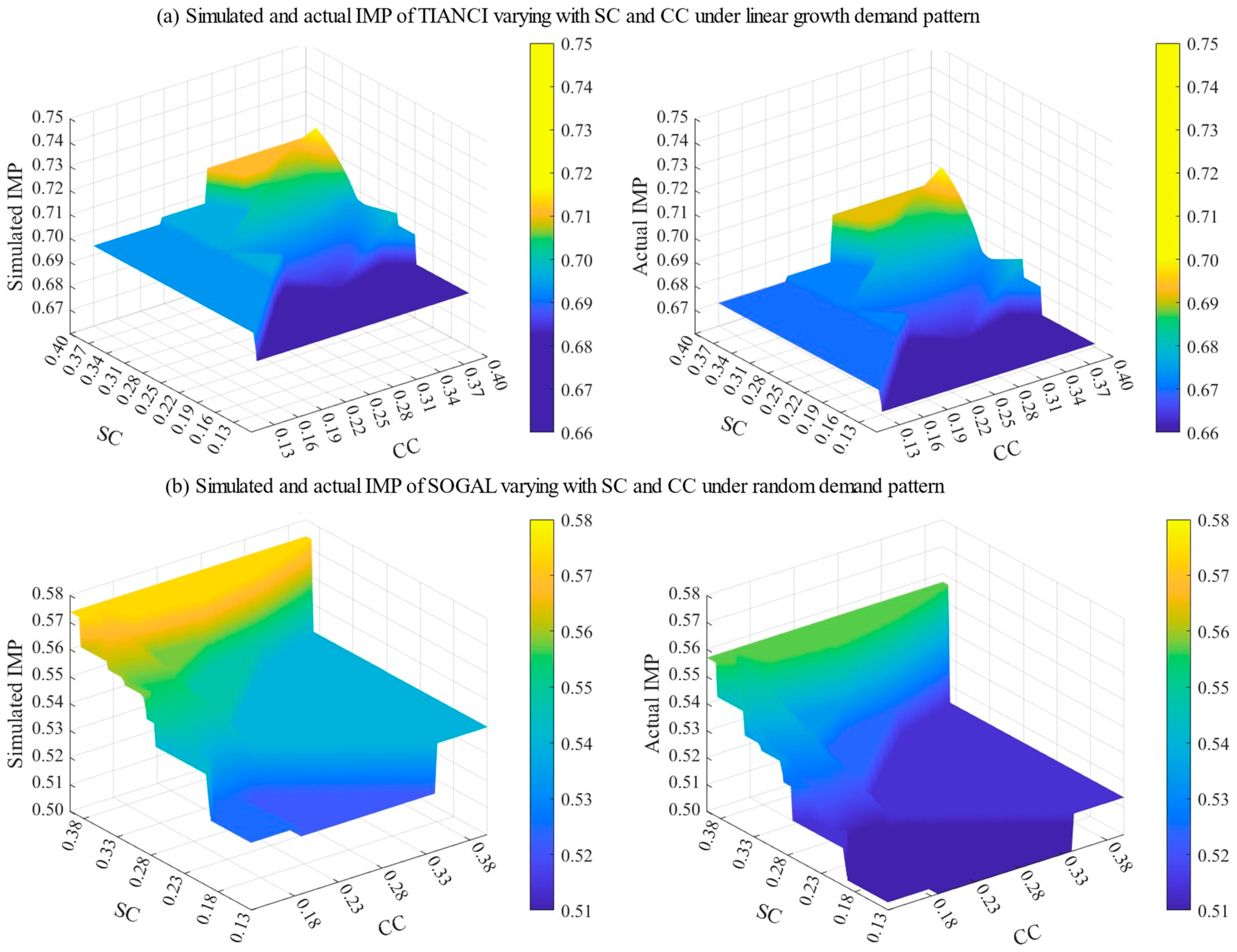

5.2.1. Sensitivity Analysis of the Model Under Linear Growth Demand

5.2.2. Sensitivity Analysis of the Model Under Random Demand

6. Conclusions and Future Work

6.1. Main Results Summary and Implications

6.2. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMP | Inventory Management Performance |

| SCC | Supply Chain Concentration |

| SC | Supplier Concentration |

| CC | Customer Concentration |

| OM | Operations Management |

| SD | System Dynamics |

| CLD | Causal Loop Diagram |

Appendix A. Contains Detailed Causal Pathways, Including

Appendix B

| Year | SC (%) | CC (%) | Sales Volume (t) | Total Production (t) | Total Inventory (t) | Total Cost (M CNY) | Total Revenue (M CNY) | Cost of Raw Material (M CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 30.89 | 22.83 | 36,911 | 37,416 | 2762 | 399.56 | 596.05 | 317.03 |

| 2014 | 30.32 | 21.28 | 52,448 | 53,389 | 3894 | 497.83 | 705.68 | 399.27 |

| 2015 | 21.60 | 30.05 | 66,953 | 67,306 | 4247 | 652.40 | 945.80 | 526.93 |

| 2016 | 39.31 | 37.76 | 89,033 | 88,586 | 3801 | 1106.64 | 1837.24 | 930.15 |

| 2017 | 33.31 | 37.74 | 105,138 | 105,934 | 4597 | 1359.62 | 2057.30 | 1133.96 |

| 2018 | 31.56 | 38.38 | 125,037 | 125,968 | 5527 | 1574.01 | 2079.84 | 1304.66 |

| 2019 | 31.56 | 41.99 | 153,105 | 153,463 | 5885 | 2048.29 | 2754.58 | 1557.09 |

| 2020 | 37.14 | 43.47 | 191,083 | 194,272 | 9074 | 2678.49 | 4119.04 | 1939.10 |

| 2021 | 33.89 | 66.89 | 321,548 | 322,686 | 10,210 | 7210.68 | 11,090.80 | 5971.82 |

| 2022 | 36.86 | 70.82 | 324,573 | 439,146 | 15,124 | 8032.78 | 11,327.54 | 6583.73 |

Appendix C

| Month | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales(t) | Sales(t) | Sales(t) | Sales(t) | Sales(t) | Sales(t) | Sales(t) | Sales(t) | |

| Jan. | 1059.87 | 1784.21 | 1874.30 | 2613.23 | 2982.94 | 2402.92 | 4391.86 | 3200.73 |

| Feb. | 1096.41 | 1839.96 | 2132.83 | 3146.36 | 3386.04 | 3019.88 | 5840.72 | 4723.69 |

| Mar. | 1498.43 | 1951.48 | 2455.98 | 2980.30 | 3708.52 | 2695.17 | 4859.72 | 12,736.27 |

| Apr. | 1303.30 | 1987.71 | 2792.78 | 3141.36 | 3657.69 | 4804.77 | 5970.64 | 9374.27 |

| May. | 1403.55 | 2282.19 | 2934.79 | 3141.36 | 4906.04 | 5250.57 | 6886.27 | 6783.59 |

| Jun. | 2305.84 | 3092.00 | 3739.49 | 3850.69 | 3919.84 | 6455.89 | 7802.73 | 7432.78 |

| Jul. | 1961.68 | 2287.91 | 2996.87 | 3315.17 | 4079.15 | 5030.72 | 7798.06 | 12,437.27 |

| Aug. | 1961.68 | 2815.88 | 2956.10 | 3370.79 | 4328.05 | 5900.43 | 9154.25 | 8759.21 |

| Sep. | 2615.58 | 3695.85 | 4240.47 | 4438.77 | 5420.43 | 6122.13 | 11,301.54 | 12,971.43 |

| Oct. | 1991.13 | 2303.69 | 2650.00 | 3445.89 | 4276.73 | 6515.52 | 10,967.00 | 8437.26 |

| Nov. | 2062.24 | 2779.11 | 2498.32 | 3691.19 | 4745.41 | 6999.78 | 14,334.82 | 7495.23 |

| Dec. | 3057.80 | 2858.52 | 3774.24 | 4543.90 | 5624.19 | 8496.59 | 17,875.35 | 18,433.51 |

Appendix D

| Month | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||||

| Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | |

| 1 | 684,307 | −22.51 | 1,021,564 | −16.73 | 1,302,836 | −27.79 | 1,863,178 | −22.86 | 2,126,073 | −27.42 |

| 2 | 716,728 | −18.84 | 1,057,217 | −13.82 | 1,415,427 | −21.55 | 2,008,215 | −16.86 | 2,371,389 | −19.04 |

| 3 | 843,929 | −4.43 | 1,190,163 | −2.99 | 1,721,030 | −4.61 | 2,431,056 | 0.65 | 2,815,294 | −3.89 |

| 4 | 847,963 | −3.98 | 1,178,008 | −3.98 | 1,729,073 | −4.16 | 2,303,869 | −4.62 | 2,675,114 | −8.67 |

| 5 | 904,753 | 2.45 | 1,255,327 | 2.32 | 1,849,706 | 2.53 | 2,453,370 | 1.57 | 2,862,021 | −2.29 |

| 6 | 999,972 | 13.24 | 1,304,997 | 6.37 | 2,026,634 | 12.33 | 2,769,106 | 14.64 | 3,235,836 | 10.47 |

| 7 | 894,291 | 1.27 | 1,203,187 | −1.93 | 1,809,495 | 0.30 | 2,497,997 | 3.42 | 2,885,384 | −1.50 |

| 8 | 950,859 | 7.67 | 1,295,724 | 5.62 | 1,954,254 | 8.32 | 2,506,922 | 3.79 | 2,850,339 | −2.69 |

| 9 | 935,878 | 5.98 | 1,284,797 | 4.73 | 1,938,170 | 7.43 | 2,704,397 | 11.96 | 3,224,154 | 10.07 |

| 10 | 1,044,394 | 18.27 | 1,418,640 | 15.64 | 2,219,647 | 23.03 | 2,928,648 | 21.25 | 3,247,518 | 10.87 |

| 11 | 870,24 | −1.46 | 1,237,293 | 0.85 | 1,793,410 | −0.59 | 2,153,253 | −10.85 | 3,235,836 | 10.47 |

| 12 | 903,798 | 2.34 | 1,274,837 | 3.91 | 1,889,917 | 4.75 | 2,365,232 | −2.08 | 3,621,333 | 23.63 |

| Month | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||

| Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | Sales (m2) | Fluctuation (%) | |

| 1 | 2,661,402 | −21.78 | 583,611 | −24.58 | 527,543 | −31.30 | 701,328 | −23.58 | 420,584 | −25.31 |

| 2 | 2,836,494 | −16.64 | 621,263 | −19.72 | 286,708 | −62.66 | 746,784 | −18.63 | 455,722 | −19.07 |

| 3 | 3,116,642 | −8.40 | 743,633 | −3.90 | 602,087 | −21.59 | 876,660 | −4.48 | 542,346 | −3.69 |

| 4 | 3,046,605 | −10.46 | 673,035 | −13.03 | 659,429 | −14.13 | 818,216 | −10.85 | 538,448 | −4.38 |

| 5 | 3,221,697 | −5.32 | 710,687 | −8.16 | 768,378 | 0.06 | 863,672 | −5.9 | 578,585 | 2.75 |

| 6 | 3,729,465 | 9.61 | 866,003 | 11.91 | 911,732 | 18.73 | 1,045,498 | 13.92 | 649,170 | 15.28 |

| 7 | 3,344,262 | −1.72 | 767,166 | −0.86 | 785,580 | 2.30 | 896,141 | −2.36 | 564,488 | 0.25 |

| 8 | 3,291,734 | −3.26 | 757,752 | −2.08 | 797,049 | 3.80 | 889,647 | −3.07 | 601,378 | 6.80 |

| 9 | 3,589,391 | 5.49 | 837,764 | 8.26 | 900,264 | 17.24 | 980,560 | 6.84 | 601,175 | 6.76 |

| 10 | 3,729,465 | 9.61 | 818,937 | 5.83 | 900,264 | 17.24 | 967,572 | 5.42 | 664,277 | 17.97 |

| 11 | 3,869,539 | 13.72 | 908,362 | 17.38 | 963,340 | 25.45 | 1,084,460 | 18.16 | 548,497 | −2.59 |

| 12 | 4,394,815 | 29.16 | 997,786 | 28.94 | 1,112,428 | 44.87 | 1,142,904 | 24.53 | 592,584 | 5.23 |

Appendix E

| Year | SC (%) | CC (%) | Production (m2) | Sales Volume (m2) | Inventory (m2) | Total Cost (M CNY) | Total Revenue (M CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 33.85 | 14.48 | 6,772,283 | 6,757,273 | 164,791 | 789.6 | 1212.6 |

| 2013 | 39.40 | 15.80 | 10,692,317 | 10,597,093 | 260,015 | 1117.72 | 1772.10 |

| 2014 | 35.45 | 13.44 | 14,685,988 | 14,721,709 | 224,294 | 1474.49 | 2346.27 |

| 2015 | 32.96 | 14.97 | 21,739,578 | 21,649,596 | 314,275 | 1980.34 | 3176.23 |

| 2016 | 27.45 | 18.07 | 28,952,782 | 28,985,242 | 281,816 | 2862.84 | 4506.14 |

| 2017 | 23.79 | 21.19 | 35,143,109 | 35,150,290 | 274,635 | 3787.62 | 6114.50 |

| 2018 | 21.88 | 19.80 | 40,859,530 | 40,831,511 | 302,654 | 4540.28 | 7266.52 |

| 2019 | 23.26 | 14.82 | 40,248,720 | 40,239,321 | 312,054 | 4802.75 | 7644.39 |

| 2020 | 21.73 | 16.66 | 40,093,594 | 39,930,806 | 474,842 | 5280.79 | 8316.72 |

| 2021 | 27.57 | 17.52 | 48,062,245 | 47,724,912 | 812,176 | 6922.51 | 10,343.15 |

| 2022 | 23.08 | 13.39 | 4,704,729 | 46,963,515 | 895,952 | 9910.97 | 11,222.58 |

References

- Ameh, B. Advancing national security and economic prosperity through resilient and technology driven supply chains. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 24, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăbîrcă, A.I.; Radu, V.; Cozorici, A.N.; Tanase, L.C.; Radu, F. Professional Determinants in ESG Reporting for Sustainable Financial Assessment. Systems 2025, 13, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport 2023: Towards a Green and Just Transition; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://unctad.org/rmt2023 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- ECB. Geopolitical Fragmentation and Its Impact on Global Trade and Supply Chains. ECB Econ. Bull. 2023, 7, 2839. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/html/eb202307.en.html (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Ahmadini, A.A.H.; Modibbo, U.M.; Shaikh, A.A. Multi-objective optimization modelling of sustainable green supply chain in inventory and production management. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5129–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çömez-Dolgan, N.; Moussawi-Haidar, L.; Jaber, M.Y. A buyer-vendor system with untimely delivery costs: Traditional coordination vs. VMI with consignment stock. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 154, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maly, L.O.; Avinadav, T. Smart allocation of a developer’s spending on product quality and non-salary employee benefits in a supply chain of apps. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2023, 10, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, C.; Jin, H.; Swanson, R.D.; Waller, M.A.; Williams, B.D. The impact of key retail accounts on supplier performance: A collaborative perspective of resource dependency theory. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao Jeihoonian, M.; Kazemi Zanjani, M.; Gendreau, M. Dynamic reverse supply chain network design under uncertainty: Mathematical modeling and solution algorithm. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 29, 3161–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhu, X. Lean inventory and ESG performance: An inverted U-shaped relationship. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 36, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalin, F.; Pang, G.; Maioli, S.; Cao, T. Inventories and the concentration of suppliers and customers: Evidence from the Chinese manufacturing sector. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, B.K.; Patatoukas, P.N. Customer-base concentration and inventory efficiencies: Evidence from the manufacturing sector. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2016, 25, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, M.; Cachon, G.P. Drivers of finished-goods inventory in the U.S. automobile industry. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, D.; Wempe, W.F.; Zacharia, Z.G. Concentrated supply chain membership and financial performance: Chain- and firm-level perspectives. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CATL. Study on the Profit Model of Power Battery Enterprises: CATL’s Customer Concentration Analysis; Report; CATL: Ningde, China, 2021; Available online: https://www.catl.com/static/upload/file/20220421/2021AnnualReport.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Johnson, W.C.; Kang, J.K.; Yi, S. The certification role of large customers in the new issues market. Financ. Manag. 2020, 39, 1425–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patatoukas, P.N. Customer-base concentration: Implications for firm performance and capital markets. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zou, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Does a firm’s supplier concentration affect its cash holding? Econ. Model. 2020, 90, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Fan, R. Customer concentration and corporate innovation: Evidence from China. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 54, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Li, J.J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, L. The delicate equilibrium: Unveiling the curvilinear nexus between supply concentration and organizational resilience. Br. J. Manag. 2024, 35, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerasoponpong, S.; Sopadang, A. Decision support system for adaptive sourcing and inventory management in small and medium-sized enterprises. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Zhu, P.C.; Xiao, W.L.; Lin, Y.-T. Centrality and supplier performance: The moderate role of resource dependence. Oper. Manag. Res. 2021, 14, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braglia, M.; Frosolini, M.; Gallo, M. SMED enhanced with 5-whys analysis to improve setup-reduction programs: The SWAN approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 90, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Y. Solving inventory management problems through deep reinforcement learning. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2022, 31, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ye, Y.; Shi, Z. Optimization of Semi-Finished Inventory Management in Process Manufacturing: A Multi-Period Delayed Production Model. Systems 2025, 13, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Na, J.; Kim, B. Strategic effects of supply chain inventories on sales performance. Eng. Manag. J. 2020, 32, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, A.; Corlu, C.G. Simulation of inventory systems with unknown input models: A data-driven approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 5826–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.Z.; Zhang, D.Q.; Sun, Y.M.; Guan, Z.M. A CVaR-based robust optimization model for retailers’ inventory under supply and demand uncertainty. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 12, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tao, Q.; Feng, Q.; Sun, Y. Supplier concentration and firm risk-taking: Transaction cost perspective. J. Financ. Res. 2024, 133, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbrook-Johnson, P.; Penn, A.S. System Dynamics. In Systems Mapping; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Zhang, Q.A. Multicriteria decision making method based on intuitionistic fuzzy weighted entropy. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, J. Manufacturer’s vertical integration strategies in a three-tier supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 135, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, F.; Schoenherr, T.; Gong, Y.; Chen, L. Cross-border e-commerce firms as supply chain integrators: The management of three flows. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tang, X.; Liu, H.; Gu, J. The impact of supply chain concentration on integration and business performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 257, 108781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Xu, J.; Han, Y. A proprietary component manufacturer’s global supply chain design: The impacts of tax and organizational structure. Omega 2023, 115, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Renko, H.; Denoo, L.; Janakiraman, R. A knowledge-based view of managing dependence on a key customer: Survival and growth outcomes for young firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H. Synchronized production and maintenance scheduling for turnover reliability. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.J.M.; Rao, A.N.; Krishnanand, L. Manufacturer performance modelling using system dynamics approach. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 33, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwik, P.; Hellström, D. Successful competence development for retail professionals: Investigation of key mechanisms in informal learning. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2023, 51, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencent News. Reasons for the Price Increase of Storage IC Chips and the Latest Market Forecast. Tencent News. 12 October 2023. Available online: https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20231012A07C5O00 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens AG. Digital Enterprise Case Study: Amberg Plant; Siemens AG: Munich, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://techorange.com/2023/04/19/siemens-amberg/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Inditex Group. Annual Report 2023; Inditex: Arteixo, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://static.inditex.com/annual_report_2023/en/Inditex_Group_Annual_Accounts_2023.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Dell Technologies. Supply Chain Sustainability Report; Dell Technologies: Round Rock, TX, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.delltechnologies.com/asset/de-at/solutions/business-solutions/briefs-summaries/delltechnologies-fy23-supply-chain-sustainability-summary.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Tencent Cloud. How P&G Uses EDI to Achieve Supply-Chain Integration. Tencent Developer Community. 18 August 2021. Available online: https://cloud.tencent.com/developer/article/1864228 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Aljuhmani, A.I.; Alomari, M.A. Inventory Turnover and Firm Profitability: A Saudi Arabian Manufacturing Sector Perspective. Processes 2023, 11, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SiTime Corporation. Annual Report 2022; SiTime Corporation: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.sgpjbg.com/baogao/564042.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Shanghui Certified Public Accountants (Special General Partnership). Reply to the Second Round of Review Inquiries Regarding the Initial Public Offering and Listing on the Growth Enterprise Market of Shandong SanYuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Updated with 2021 Semi-Annual Report Data); Sina Finance: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: https://vip.stock.finance.sina.com.cn/corp/view/vCB_AllBulletinDetail.php?id=7575845 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Fonseca, L.; José Carlos, S.Á.; Lima, V. Evaluating the synergy between lean practices and sustainability in supply chains: A conceptual framework for supplier assessment. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davizón, Y.A.; Hernández-Santos, C.; de la Cruz, N.; Garcia-Andrade, R.; Ramirez, A.F.; Hernández, A.; Tobías-Macías, F.F.; Rincón, E.; Reyes, A.-M.; Smith, E.D. Mathematical Methods for Inventory Management in Dynamic Supply Chains. Systems 2025, 13, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enterprise’s Name | Gross Margin | Inventory Depreciation Provision | Inventory Turnover | Cycle Rate | Inactive Rate | Market Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOGAL | 0.3307 | 40,210,628.80 | 30.2517 | 20.1049 | 0.1209 | 0.0129 |

| HOLIKE | 0.3452 | 16,056,027.83 | 12.0302 | 7.7923 | 0.1805 | 0.0041 |

| SPOZO | 0.3311 | 0.00 | 11.4506 | 7.4518 | 0.1452 | 0.0077 |

| OPPEIN | 0.3137 | 0.00 | 19.6944 | 12.9854 | 0.0877 | 0.0255 |

| ZBOM | 0.3734 | 6,971,308.96 | 7.0999 | 4.3548 | 0.2132 | 0.0061 |

| GOLDEN | 0.2923 | 1,193,666.88 | 48.7439 | 34.3038 | 0.0358 | 0.0042 |

| PIANO | 0.3374 | 39,128,824.52 | 2.9235 | 2.2827 | 0.3439 | 0.0022 |

| OLO | 0.4132 | 1,193,666.88 | 7.2071 | 4.1045 | 0.2201 | 0.0022 |

| DEEGO | 0.3233 | 7,286,961.84 | 4.0262 | 2.6962 | 0.3101 | 0.0016 |

| Constants | Symbols | Values | Units | Bibliographic Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier Concentration | Simulation Settings | Dmnl | [18] | |

| Customer Concentration | Simulation Settings | Dmnl | [17] | |

| Initial In-Transit Inventory | 100,000 | Pcs | [27] | |

| Initial Work in Process | 50,000 | Pcs | [27] | |

| Initial Inventory | 120,000 | Pcs | [27] | |

| Linear Initial Demand | 75,000 | Pcs | [27] | |

| Set-Up Order Cost | 100 | Dmnl | [23] | |

| Holding Cost Per Unit | 0.32 | Dmnl | [27] | |

| Delivery Delay | 1 | week | [6] | |

| Transportation Delay | 2 | week | [23] | |

| Production Delay | 1 | week | [23] | |

| Thresholds for Supply Chain Stability | 0.1 | Dmnl | [9] | |

| Raw Material Benchmark Prices | 9 | Dmnl | [23] | |

| Demand Forecast Benchmark | 1 | Dmnl | [27] | |

| Maximum Price of Raw Materials | 9.5 | Dmnl | [23] | |

| Lowest Price for Raw Materials | 8.3 | Dmnl | [23] | |

| Product Benchmark Price | 18.5 | Dmnl | [11] | |

| Maximum Price of the Product | 20 | Dmnl | [17] | |

| Lowest Price for the Product | 17.5 | Dmnl | [17] | |

| Customer Churn Threshold | 0.9 | Dmnl | [36] | |

| Customer Churn | 0.5 | Dmnl | [36] | |

| Proportion of the Financial Performance | 0.3 | Dmnl | [11] | |

| Proportion of Inventory Control | 0.4 | Dmnl | [8] | |

| Proportion of Customer Service | 0.3 | Dmnl | [8] | |

| Impact Factor of SCC | 0.38 | Dmnl | [9] | |

| Impact Factor of Operational Efficiency | 1.125 | Dmnl | [8] | |

| Inventory Adjustments Coefficient | 1 | Dmnl | [11] | |

| Distributed Demand Coefficient | 0.2 | Dmnl | [9] |

| The Type of Variable | Variables | Symbols | Equations | Serial Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | In-Transit Stock | (6) | ||

| Work In Process | (7) | |||

| Inventory | (8) | |||

| Profits | (9) | |||

| Total Business | (10) | |||

| Rate | Raw Materials Shipment | (11) | ||

| Raw Materials Arrival | (12) | |||

| Production | (13) | |||

| Product Shipment | ) | (14) | ||

| Total Cost | (15) | |||

| Total Revenue | (16) | |||

| Business Churn | (17) | |||

| Auxiliary | Suppliers’ Bargaining Power | (18) | ||

| Customers’ Bargaining Power | Pcb | (19) | ||

| Order Price | (20) | |||

| Selling Price Per Unit | (21) | |||

| Order Quantity | (22) | |||

| Order Cost | (23) | |||

| Holding Cost | (24) | |||

| Stock-Out Cost | (25) | |||

| Cycle Rate of Inventory | (26) | |||

| Customer Churn | (27) | |||

| Stock-Out Rate | (28) | |||

| Inventory Management Performance | (29) | |||

| Operation Efficiency | (30) | |||

| In-Transit Stock Adjustment | (31) | |||

| In-Transit Stock Adjustment Coefficient | (32) | |||

| Inventory Adjustment | (33) | |||

| Market Demand Forecasting | (34) | |||

| Deviation of the Market Demand Forecast | (35) | |||

| Demand Fragmentation | (36) | |||

| Linear Demand | (37) | |||

| Random Demand | (38) | |||

| Financial Performance | (39) | |||

| Inactive Rate | (40) | |||

| Increase Rate of Main Business Revenue | (41) | |||

| Inventory Control | (42) | |||

| Customer Service | (43) | |||

| Out-of-Stock | (44) | |||

| Inactive Inventory | ) | (45) | ||

| Supply Chain Stability | Scs | (46) |

| Year | SC (%) | CC (%) | Raw Material Cost Per Unit (CNY) | Selling Price Per Unit (CNY) | Product Cost Per Unit (CNY) | Initial Demand (ton) | Added Demand (ton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 30.89 | 22.83 | 8473.18 | 16,148.55 | 10,678.93 | 630.00 | 3.44 |

| 2014 | 30.32 | 21.28 | 7287.50 | 13,454.96 | 9324.50 | 770.71 | 9.85 |

| 2015 | 21.60 | 30.05 | 7827.37 | 14,126.50 | 9693.11 | 899.70 | 15.18 |

| 2016 | 39.31 | 37.76 | 10,500.02 | 20,635.68 | 12,492.39 | 1284.46 | 16.12 |

| 2017 | 33.31 | 37.74 | 10,704.31 | 19,567.56 | 12,834.61 | 1492.77 | 20.94 |

| 2018 | 31.56 | 38.38 | 10,357.13 | 16,633.85 | 12,495.43 | 2078.14 | 13.24 |

| 2019 | 31.56 | 41.99 | 10,146.35 | 17,991.49 | 13,347.21 | 2380.79 | 21.94 |

| 2020 | 37.14 | 43.47 | 9981.36 | 21,556.31 | 13,787.31 | 2067.24 | 64.18 |

| 2021 | 33.89 | 66.89 | 18,506.59 | 34,491.90 | 22,345.81 | 3642.09 | 98.59 |

| 2022 | 36.86 | 70.82 | 17,432.73 | 34,853.66 | 22,757.43 | 3465.73 | 87.46 |

| Year | Simulated Value | Year | Simulated Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 0.6964 | 2018 | 0.6947 |

| 2014 | 0.6937 | 2019 | 0.6982 |

| 2015 | 0.6825 | 2020 | 0.7265 |

| 2016 | 0.7109 | 2021 | 0.7453 |

| 2017 | 0.7023 | 2022 | 0.7396 |

| Year | SC (%) | CC (%) | IMP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Value | Simulated Value | Relative Error | |||

| 2013 | 30.89 | 22.83 | 0.6718 | 0.6964 | 0.0366 |

| 2014 | 30.32 | 21.28 | 0.6697 | 0.6937 | 0.0358 |

| 2015 | 21.60 | 30.05 | 0.6613 | 0.6825 | 0.0321 |

| 2016 | 39.31 | 37.76 | 0.6914 | 0.7109 | 0.0282 |

| 2017 | 33.31 | 37.74 | 0.6821 | 0.7023 | 0.0296 |

| 2018 | 31.56 | 38.38 | 0.6729 | 0.6947 | 0.0324 |

| 2019 | 31.56 | 41.99 | 0.6751 | 0.6982 | 0.0342 |

| 2020 | 37.14 | 43.47 | 0.7146 | 0.7265 | 0.0167 |

| 2021 | 33.89 | 66.89 | 0.7319 | 0.7453 | 0.0183 |

| 2022 | 36.86 | 70.82 | 0.7239 | 0.7396 | 0.0217 |

| Year | SC (%) | CC (%) | Order Price (CNY) | Selling Price Per Unit (CNY) | Average Demand (m2) | Maximum Demand (m2) | Minimum Demand (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 0.394 | 0.158 | 104.53 | 167.22 | 373,836 | 469,274 | 327,479 |

| 2014 | 0.354 | 0.134 | 100.40 | 159.37 | 397,737 | 473,997 | 337,758 |

| 2015 | 0.329 | 0.149 | 91.09 | 146.71 | 416,338 | 484,284 | 340,523 |

| 2016 | 0.274 | 0.180 | 98.87 | 155.46 | 557,408 | 660,819 | 421,209 |

| 2017 | 0.237 | 0.211 | 107.77 | 173.95 | 675,967 | 895,512 | 534,418 |

| 2018 | 0.218 | 0.198 | 111.11 | 177.96 | 785,221 | 1,051,149 | 636,552 |

| 2019 | 0.232 | 0.148 | 119.32 | 189.97 | 773,833 | 997,886 | 583,669 |

| 2020 | 0.217 | 0.166 | 131.71 | 208.27 | 767,900 | 1,120,094 | 286,708 |

| 2021 | 0.276 | 0.175 | 144.03 | 216.72 | 917,787 | 1,142,904 | 701,328 |

| 2022 | 0.231 | 0.132 | 139.27 | 225.31 | 872,473 | 1,097,427 | 694,737 |

| Year | Simulated Value | Year | Simulated Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 0.5738 | 2018 | 0.5214 |

| 2014 | 0.5630 | 2019 | 0.5414 |

| 2015 | 0.5579 | 2020 | 0.5250 |

| 2016 | 0.5474 | 2021 | 0.5498 |

| 2017 | 0.5398 | 2022 | 0.5387 |

| Year | SC (%) | CC (%) | IMP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Value | Simulated Value | Relative Error | |||

| 2013 | 39.40 | 15.80 | 0.5569 | 0.5738 | 0.0303 |

| 2014 | 35.45 | 13.44 | 0.5447 | 0.5630 | 0.0336 |

| 2015 | 32.96 | 14.97 | 0.5336 | 0.5579 | 0.0455 |

| 2016 | 27.45 | 18.07 | 0.5240 | 0.5474 | 0.0446 |

| 2017 | 23.79 | 21.19 | 0.5137 | 0.5398 | 0.0509 |

| 2018 | 21.88 | 19.80 | 0.5000 | 0.5214 | 0.0429 |

| 2019 | 23.26 | 14.82 | 0.5140 | 0.5414 | 0.0534 |

| 2020 | 21.73 | 16.66 | 0.5029 | 0.5250 | 0.0440 |

| 2021 | 27.57 | 17.52 | 0.5263 | 0.5498 | 0.0447 |

| 2022 | 23.08 | 13.39 | 0.5172 | 0.5390 | 0.0422 |

| Enterprise’s Name | Supplier Concentration (%) | Customer Concentration (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SOGAL | 21.37 | 11.97 |

| OPPEIN | 14.63 | 4.06 |

| ZBOM | 16.87 | 10.54 |

| GOLDEN | 19.89 | 7.00 |

| HOLIKE | 16.84 | 34.02 |

| Simulation Scenarios | Scheme | SC (%) | CC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Scenario | Base | 20 | 20 |

| Scenarios for Different Levels of SC | A1 | 30 | 20 |

| A2 | 40 | 20 | |

| A3 | 50 | 20 | |

| A4 | 60 | 20 | |

| A5 | 70 | 20 | |

| Scenarios for Different Levels of CC | B1 | 20 | 30 |

| B2 | 20 | 40 | |

| B3 | 20 | 50 | |

| B4 | 20 | 60 | |

| B5 | 20 | 70 | |

| Scenarios for Different Levels of SCC | C1 | 30 | 20 |

| C2 | 20 | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Zheng, X.; Gao, S. Theoretical Analysis of Dynamic Effects of Supply Chain Concentration on Inventory Management Performance: A System Dynamics Approach. Systems 2025, 13, 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121084

Zhang X, Liu M, Zheng X, Gao S. Theoretical Analysis of Dynamic Effects of Supply Chain Concentration on Inventory Management Performance: A System Dynamics Approach. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121084

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaoyue, Meiling Liu, Xuke Zheng, and Shan Gao. 2025. "Theoretical Analysis of Dynamic Effects of Supply Chain Concentration on Inventory Management Performance: A System Dynamics Approach" Systems 13, no. 12: 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121084

APA StyleZhang, X., Liu, M., Zheng, X., & Gao, S. (2025). Theoretical Analysis of Dynamic Effects of Supply Chain Concentration on Inventory Management Performance: A System Dynamics Approach. Systems, 13(12), 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121084