Abstract

It is reasonable to argue that researching imagery experiences requires substantial use of conceptual modeling. Cognitive architectures have been used to explain cognitive phenomena like perception, action, and information gathering, and to model them in computational solutions. However, the question arises: Is there a lack of cognitive architectures or models that represent relational and classificatory knowledge of imagery experiences? This systematic review defines the concepts of cognitive architecture and cognitive model and examines how recent research relates the concepts to imagery experiences. A concept token research methodology is applied in search of keywords and key phrases that signify occurrences of targeted concepts. The methodology is viewed as a way to define a research area based on the concept of mental imagery and other related concepts that expand this area. The results demonstrate a significant and steady upward trend in publications from the research area in the last few years. The concepts of mental imagery and motor imagery emerged as the most regularly discussed, while others, such as imagery experiences, sensorimotor, mental model and active vision, were addressed rather rarely and thus represent new avenues for investigation.

1. Introduction

Conceptual modeling is a process that involves representing and organizing knowledge in a form that allows easier analysis, explanation, and theorization. It can be claimed that conceptual models may be designed to represent knowledge from any domain. However, specific areas of knowledge that involve concepts that lack precise definitions may also have insufficient conceptual models or techniques for modeling. Moreover, if a relatively new field, such as computational cognitive science, demands such concepts, the challenge to formulate and apply models becomes even greater. Classifying imagery experiences may be the next challenge that science must address in order to research consciousness. If conceptual models of imagery experience types are demanded by computational researchers, are there useful frameworks and solid understandings that modern science can offer?

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, cognitive architectures were established as a research instrument for studying and explaining mental imagery [1,2,3,4,5]. At that time, there were already earlier studies that presented the idea of applying the concept of mental imagery in modeling cognitive systems [6,7,8], but they were limited in number and only one of them explicitly discussed the concept of a cognitive architecture [6]. Since the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the research topic has expanded, which is why the year 2009 was chosen as the cutoff year for considering articles as recent.

In the meantime, right before the beginning of the new millennium, imagery experiences have been related to consciousness. In the year of 1999, an article was published that coins mental imagery as “a basic building block of all consciousness” [9]. Even though it is reasonable to argue that conscious experiences can be measured based on the vividness of mental imagery, in 2009 the conception of conscious mental imagery was dissociated from conceptual representations [10]. Nevertheless, consciousness and mental imagery are concepts that give rise to debates in cognitive science and demand classifications as “everyone agrees that the experience of imagery exists and that any adequate theory of imagery must ultimately be able to account for it” [11].

1.1. Rationale

Basal directions were provided for initial scientific works that separately link mental imagery to cognitive architectures and consciousness. Usually, these two research paths do not cross and are followed by different scientists. One of the groups use experimental evidence on imagery to inspire, design, and support their cognitive architecture models, while the other works towards evaluating, classifying, and explaining imagery in human subjects. Based on this judgment, it can be said that the problem of understanding consciousness merits scientific attention.

1.1.1. Consciousness and Imagery

Explaining consciousness as a continuous stream of discrete experiences [12] allows us the possibility to theorize on what a conscious experience is, and how it is formed in terms of human memory [13,14]. Furthermore, conscious experiences are now tightly associated with visual imagery experiences [15,16,17]. A clear dichotomic classification of the latter was coined by David Marks in his work on the Action Cycle Theory [18]. He defines perceptual imagery as a subjective experience that occurs when there is a “stimulation of the retinae with light” and mental imagery as a quasi-perceptual experience that occurs “in the absence of the relevant object” [18]. These definitions have been applied in a theoretical approach, which formulates an imagery experience type as a discrete conscious experience that occurs in a single iteration of the cognitive cycle [19,20,21]. This approach is related to several previously presented comprehensions of cognition as a continuous stream of rapidly occurring experiences. They are found in works related to Neisser’s Perceptual Cycle Model [22], the Action Cycle Theory [18] and the cognitive cycle as explained by the Global Workspace Theory [23]. A specific low-level formulation of the consecutive processes in the cognitive cycle has been provided and simulated via the LIDA cognitive architecture [12]. This formulation was later adopted in designing a cognitive test that measures the timing of the human cognitive cycle [24]. All of these works suggest that mental imagery can be considered as discrete experiences of consciousness.

Based on the reasoning in the previous paragraph, classifying imagery experiences could represent a path toward explaining consciousness. Furthermore, if relationships among imagery experience types are identified, it may become possible to predict how individuals experience the world. Currently, science provides methodologies for classifying imagery experiences. One such approach involves determining three common aspects of imagery: (1) cognitive, (2) imagery use, and (3) clinical aspects, which are derived from the application demands in clinical psychology [25]. Another methodology for classification comprises characteristics of vividness of mental imagery [26]. These two ways of classifying imagery have a goal in common; they aim at providing directions for verbally evaluating imagery as experienced by subjects. The other available methodology is directed towards classifying imagery in scientific research and is focused on the conceptual characteristics of mental imagery [27]. It includes not only visual imagery experiences but also multisensory imagery. Moreover, the framework by Macfie, Hay, and Rodgers includes emotion as a modality of imagery and imagination as an imagery process [27]. With the goal of including many research studies, this methodology provides general characteristics of imageries.

The methodologies for imagery classification provided by modern science are broad and do not present a specific map of related imagery types. The demand for a general comprehensive model of imagery experience types directs the research attention towards studying cognitive architectures and cognitive conceptual modeling. The model of the Action Cycle Theory [18] and the General Internal Model of Attention [19] can be considered as attempts to more precisely and comprehensively define types of imagery experiences. However, it can be claimed that they lack solid neuroscientific evidence, and thus further research is demanded before they can be adopted by other scientists for general use.

1.1.2. Defining the Concepts of Cognitive Architecture and the Cognitive Model

To investigate whether there is a lack of cognitive architectures or cognitive models that explain and organize knowledge related to imagery experiences, it is first necessary to establish solid definitions of the two concepts. A cognitive architecture is by itself a cognitive model but there is a particular difference that is going to be addressed in this work. The purpose for designing a cognitive architecture is usually to conduct computational operations via its modules. Whether the higher goal is to simulate and explain human cognition or develop artificial intelligence (AI) methods, a cognitive architecture provides organized concepts that can be used to perform computations involving related elements, such as neural networks or graph-based structures [5,28,29]. Others apply the concepts as sequentially connected system components, which are responsible for conducting their own dedicated computations [30]. On this basis, it is reasonable to formulate the following definitions:

- A cognitive architecture is a conceptual model that is a cognitive system design, implementable in a machine for achieving computations that, at some degree, replicate cognition.

- A cognitive model is a conceptual model that explains relations between cognitive concepts such as processes, memory, and experiences. A cognitive model and its components aim to explain cognition as fully as possible.

A cognitive architecture can by itself be a cognitive model, when it is claimed that its computations aim to most realistically reproduce cognitive phenomena. Conversely, a cognitive architecture might aim to provide AI solutions for specific problems without necessarily mimicking human cognitive processes. On the other hand, the concept of a cognitive model is a more general term, used by scientists in fields such as cognitive, social, and experimental psychology to explain phenomena observed in subjects.

1.1.3. The Research Area

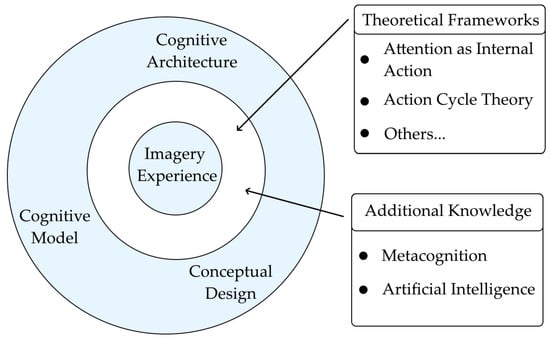

The group of concepts related to imagery experiences, including mental and motor imagery as well as body schema [31] and others (all of them fully described in Section 2), is central to this study. The concepts of cognitive architecture and cognitive model need to be linked with the central concepts in order to expand the research area. This definition is conceptually represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The defined research area based on the concept of imagery experience. The gap between the central concept group and the three peripheral concepts represents the knowledge needed to expand the research area. It can be filled with theoretical frameworks, research approaches, or scientific evidence linking the periphery to the central group. The classical distinction defined in this study between a cognitive architecture and a cognitive model is the directionality of the cognitive architecture toward computational application. In contrast, a cognitive model is an approach for explaining real-life cognitive experiences and processes. The conceptual design of cognitive architectures and models represents an additional peripheral orientation of the research area.

To expand the research area based on the imagery experience concept group, the gap between the periphery and the center needs to be filled. Studies that integrate more of the targeted concepts could provide this “gap knowledge” and serve a linking role. Such knowledge would be of benefit for those who strive to find new ways to design and apply new models of cognition in computational cognition, cognitive computation, clinical psychology or other fields.

If studies are found that include some or all of the three concepts—cognitive architecture, cognitive model, and conceptual design together with some occurrences of imagery experience concepts—it would be possible to claim that one or more solid theoretical frameworks already exist to expand the research area. These frameworks could then be identified as the ways in which scientific teams can expand and enrich the research area.

Additional concepts related to the topics of metacognition and artificial intelligence (fully specified in Section 2) can also serve a linking role. Their appearances in the eligible studies can further provide insight on how well these fields are connected to the understanding of imagery experiences. Ideas for cognitive architectures inspired by metacognition already exist, but they do not discuss the concept of imagery [32].

1.2. Objectives

This work has the main objective of identifying a research area based on concept appearances in scientific texts. A concept is claimed to have an N amount of occurrences in a text based on concept tokens that were defined as corresponding to the concept. The sum of the concept token occurrences is equal to N. By following this simple idea, a minimum required number of occurrences was set for targeted concepts that are considered to define the research area. This is further clarified in Section 2 where the targeted concepts and their corresponding concept tokens are presented.

The first research goal of this work is to find scientific works that provide knowledge of classifications, relations, and influences of imagery experiences that are integrated into a conceptual model. The latter might be a cognitive architecture or a cognitive model and is considered as the product of conceptual design. Based on the applied systematic review methodology, it could be claimed that the targeted research area discusses both imagery experiences and conceptual models if the concept occurrences in the scientific papers pass the inclusion and exclusion criteria. That is why an effort was made to define strict criteria. On the other hand, this specific combination of terms is considered quite rare and thus the criteria shall not be too strict. The concepts occurring together in a single text are viewed as the factor that identifies the research area. The combined appearance of a pair of concepts in a single text is the minimum desired outcome of this research. The more targeted concepts appear together, the greater the fulfillment of this research goal.

The second research goal is to identify how many (and to what degree) of the eligible works discuss the concepts of metacognition and artificial intelligence. The criteria for the separate articles are not going to demand a minimum occurrence count of the concepts corresponding to these topics. Extracting data on these two concepts is intended to indicate whether the research area addresses the topics. If it is found that it does not, then it would be plausible to claim that metacognition and artificial intelligence are loosely related to conceptual modeling of imagery experiences.

The third research goal is to explore and review formulated theoretical frameworks that could be employed in designing conceptual models that depict knowledge about imagery experiences. The frameworks should be based on or consider the understanding of the cognitive cycle [12,18,22,24]. This demands that the understanding of consecutive cognitive experiences is integrated in the framework. For this reason, the term “imagery experience” is more precise than just “mental imagery” even though the latter is a lot more common in the scientific texts. If the concept tokens related to imagery experience are found to appear in scientific papers, but their occurrence count is not big, it can be claimed that the area needs more research that covers the imagery experience concept. On the other hand, if mental imagery is often discussed in the text, but cognitive architectures and cognitive models are not, it would then be possible to state that there is a non-investigated area that demands the research of imagery experience types, relations, and influences, which are all factors related to knowledge stored in a conceptual model.

2. Methods

The research methodology applied in this systematic review has proven useful for investigating models of metacognition across different scientific fields [19]. It can be summarized as searching for keywords and key phrases in scientific texts that meet predefined criteria. These criteria combine rules requiring a specific number of keyword occurrences in each paper with additional conditions, such as the earliest publication year.

The research methodology requires scientists to define concepts, each of which is represented by key-term texts, referred to as concept tokens. A single occurrence of each of the latter also represents an occurrence of its corresponding concept in the scientific text. For example, the concept of imagery experience is defined as corresponding to the concept tokens: “imagery experience”, “mental imagery” and others (all of the definitions are presented in a table further below). The count of token occurrences adds to the total count of concept occurrence in the text. For example, if “imagery experience” occurs three times and “mental imagery” two times, then the total occurrence of the concept in the text is counted as five. In this way, the strictness of the exclusion criteria can be easily adjusted to satisfy the research demands. The concepts and their concept tokens defined and investigated in this research are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The researched concepts and their corresponding concept tokens that were searched in the scientific texts. A concept occurrence is viewed as an appearance of strings in the text of the identified studies. These strings are the concept tokens defined as corresponding to the concept.

An important note is that the concept occurrences are searched in the entire content of the published work, including the title, abstract, main text, and references. While it could be argued that words in the references might not be covered in the main body of the text, even a single occurrence in a reference indicates a direct relation to that specific concept. This fully defines a concept occurrence in a published work and presents a way of thinking of it as knowledge that can be searched and found in a text. This might be disapproved of by some scientists, which is why it was decided that works that have few concept occurrences in the references shall be addressed in the Discussion Section.

Providing evidence for the existence of the research area remains a fundamental goal of this work. Selected studies are those that discuss concepts expressing imagery experiences, as this represents the central concept of the research area (Figure 1). However, evidence is defined as the coexistence of two or more peripheral concepts within a single study. After grouping articles based on the co-occurrence of peripheral concepts, a synthesis can be conducted to identify the common ideas and themes represented in these groups.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Due to the search strategy, counting all concept tokens in a single scientific text takes considerable time. That is why, during the screening phase, only the tokens of the Cognition concept were counted. A minimum occurrence count of the concept was set as part of the inclusion criterion. This way, if an article has less than the specified minimum amount, it was excluded before the eligibility phase of the study selection flow.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

In order to be included in the analysis, a publication needs to comply with the two groups of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria (first group) are applied during the screening phase of the study selection flow. They can be quickly applied, as they relate to the study’s general characteristics and only the cognition concept was counted as follows:

- The publication can only be an article, a conference paper or a book chapter;

- If it is a book chapter, only one chapter of the whole book can be included;

- The year of publication must be 2009 or after;

- The publication must have a digital object identifier (DOI) supported by the International DOI Foundation (https://www.doi.org/);

- The publication must include at least four occurrences of the cognition concept.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria strictly define the research area and are naturally applied during the eligibility phase of the PRISMA flow. Several adjustments have been made during the research in order to achieve a strict and yet inclusive study analysis. During the eligibility phase, the following exclusion criteria are applied.

- The text is excluded if it has less than two occurrences of the total amount of the following concepts: cognitive model, cognitive architecture, and conceptual design.

- If the text has only 1 occurrence of the total amount of cognitive model, cognitive architecture, and conceptual design, it must have at least 30 occurrences of the concept token “model”.

- The text is excluded if it has no occurrences of the concept of imagery experience.

The reason behind the second conditional criterion is that some studies discuss imagery together with the term “model” but are still referring to conceptual models, and not to mathematical models, for example. Nevertheless, it was demanded that if such records are found, they should be more thoroughly analyzed. By satisfying these criteria, the publication is considered to fall under the research area of this systematic review. The investigation of the occurrence counts of the metacognition and the artificial intelligence concepts was demanded as additional research information and their concept tokens were not included in any criteria.

2.2. Search Strategy and Data Collection

The Scopus database was the main source for gathering studies. The official website for searching (with the advanced search option) was used by applying queries with the AND operator. Initially the following combinations were applied in the Scopus database:

- ALL (“cognitive architecture”) AND ALL (“imagery experience”);

- ALL (“cognitive architecture”) AND ALL (“mental imagery”);

- ALL (“cognitive model”) AND ALL (“mental imagery”);

- ALL (“conceptual design”) AND ALL (“mental imagery”).

Because of the fact that few studies were found with the more specific concept tokens, more broad ones, like “conceptual” and “imagery” were applied to identify more studies in the Scopus database:

- ALL (“conceptual”) AND ALL (“imagery”) AND ALL (“cognitive”);

- ALL (“cognitive”) AND ALL (“model”) AND ALL (“imagery”).

Google Scholar was also used to find some studies but most of its relevant results were already provided by the Scopus database. Around twenty studies were found via the platform that had relevant keywords, but they were excluded in the screening phase as they were missing a DOI link. The following search texts were applied in Google Scholar:

- “cognitive model and imagery”;

- “conceptual design of imagery”;

- “cognitive architectures and imagery”.

The Microsoft Excel software (version 2510) was used to collect the studies in a spreadsheet file that was shared online with the team. Before adding a study to the spreadsheet, its general characteristics were checked and the occurrences of the concept of cognition (see inclusion criteria Section 1.1.1).

After the studies were collected in the spreadsheet by the team members, the eligibility phase was started. Occurrences of concept tokens were manually counted; the search bar in the browser shows the count of the provided text. The team members copy the concept token from each of the columns in the spreadsheet and paste it in the search bar of the browser. It was important to download and open the searchable PDF file of the study, so as not to count peripheral occurrences on the journal’s website such as the ones from related articles and other sections. The occurrences count of each concept token was stored in its corresponding cell. A separate cell for each concept was placed that calculates the total amount of all the tokens corresponding to the concept. See the Data Availability Statement for a public link to the spreadsheet file for more details. Finally, records that did not satisfy the exclusion criteria were removed from the spreadsheet.

Chart.js, https://www.chartjs.org/ (accessed on 17 November 2025), was used to present some of the produced analysis data. The Microsoft’s Paint.NET application was used for editing some of the charts and presenting the conceptual understandings of the research area. The functionalities of the Microsoft Excel application allowed extracting knowledge into tables by creating separate sheets based on the collected data. All of the generated tables are publicly accessible via the link provided in the Data Availability Statement at the end of this article.

2.3. Potential Errors

This research methodology is easily applicable and allows fast collection of records, but it has some potential problems. The search for concept tokens includes the reference list of the study as well. This may lead to a false positive in keywords identification if only one occurrence is found for a concept. To increase the clarity over the actual degree of discussion of the concepts in the studies, it was decided that texts that have one occurrence of the concept shall be extracted in a separate sheet and shall be addressed in the Results Section. The exclusion criteria allow texts that have only one occurrence of the imagery experience concept to be included. This is because there was a need for more studies to be included in the analysis, and this specific combination of concepts does not appear regularly in the texts.

3. Results

Initially, around 150 records were identified via the search methods presented in Section 2.2. Queries with more specific concept tokens such as “imagery experience” and “cognitive architecture” produced very few results. That is why broader concepts were applied (see Section 3.2) to identify more studies. A decent number of studies were found on the Google Scholar platform, but they were either published before the demanded year (2009) or they did not have a DOI link. The study selection phases are depicted in the flow chart in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study selection flow diagram. Screening was applied to the identified studies using the inclusion criteria, resulting in approximately 75 studies. In the next phase, concept occurrences were counted, and the exclusion criteria were applied. Ultimately, five studies were considered marginally eligible due to few mentions of the specified concepts.

No restrictions were set on the scientific fields; studies from cognitive science, social science, computer science, and other disciplines were included. There were also no restrictions on article types; reviews and experiments were included.

3.1. Study Characteristics

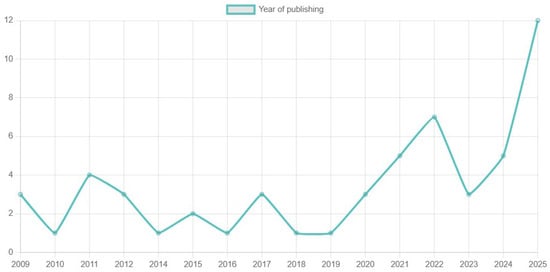

At the end of the eligibility phase, 55 works were stored in the results file. At the time of this research, no further articles meeting the criteria were found. As a first step, the publishing rate was analyzed, which formed the plot presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Counts of the researched articles published per year. It is observed that the number of publications has increased in the last five years.

Curiously, there is a big leap in publications observed in the year 2025 (the year of conducting this research). The publication rate has grown significantly, with a major increase in 2020, and has remained at a minimum of three publications annually (Figure 3). This strongly suggests that there would be more articles in the defined research area. To identify the trends and the emerging topics in the research area, an initial step is to analyze the occurrence rate of the peripheral concepts (see Figure 1)

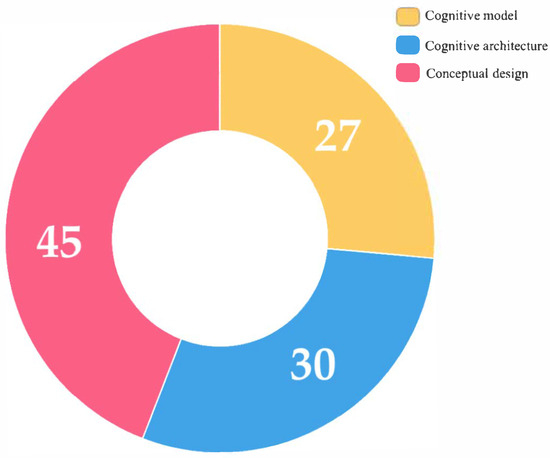

3.1.1. Occurrences of Cognitive Model, Cognitive Architecture, and Conceptual Design

The three defined concepts—cognitive model, cognitive architecture, and conceptual design—were explored by analyzing the count of articles that make any mention of them. This led to the creation of the chart presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Chart showing amount of articles that separately have at least one mention of the following concepts: cognitive model, cognitive architecture and conceptual design.

It is important to note that the numbers in the sectors (Figure 4) present the count of articles that have at least one occurrence of the concept. This means that counted articles may have only a single occurrence of a single concept token and thus it can be claimed that the article does not strongly discuss the concept. That is why an additional analysis was made to investigate the average occurrence count of the concept. The publicly available spreadsheet file contains three sheets, each representing the analysis of the three concepts. Within the sheets, each article is placed alongside the occurrence count of the researched concept. Table 2 presents the total number of the concept occurrences and the mean per scientific text.

Table 2.

Total and average occurrences of the concepts in the articles that were researched. The concept of conceptual design appears in most articles, but its average occurrence is lower than that of the two other peripheral concepts.

It is observed in Table 2 that the concept of conceptual design, although appearing in most of the studies, has the smallest mean (M = 8.15, SD = 9.87). Of the 44 articles, 5 have one occurrence of the conceptual design concept. Of the 27 studies of the cognitive model group, 8 had one occurrence. The articles that showed the highest occurrence count of this specific concept discussed the motor–cognitive model [33,34,35,36]. The work by Sima and Freksa, which shows 17 occurrences—a comparatively high number in the group—discusses an interesting idea of computational cognitive modeling of mental imagery [37]. This makes it tightly related to the aims of the theory of AIA, although it does not strongly address the concept of cognitive architecture, as it shows only three occurrences of the concept token “cognitive system”.

The group of the cognitive architecture concept presents the highest mean, suggesting that if the concept is discussed in the scientific text, it will have a high number of occurrences in them. It can be said that the concept of cognitive architecture is quite specific and, when discussed, is usually the main topic of the article; it often even appears as part of the title of the work [1,2,3,5,19,38,39,40]. The concept was defined as corresponding to the “cognitive system”, “system model”, and “neural architecture” tokens, but it was decided that an analysis should be performed specifically for the “cognitive architecture” concept token. Also included in the results spreadsheet file, the data analyzed shows a higher mean (M = 14.45, SD = 12.68) from a total of 318 occurrences.

Another way to investigate the trends in the research area is to find articles that include combinations of concept occurrences. The targeted studies were organized in groups depending on how many of the target concepts occur together in the texts. This approach formed four groups of papers that include the following concepts:

- Cognitive model and cognitive architecture;

- Cognitive model and conceptual design;

- Cognitive architecture and conceptual design;

- The three of them occurring together.

An analysis of the initially collected data was performed, and the articles were organized in correspondence to the four groups defined above. The results are presented below together with the references corresponding to the studies, as follows:

- Group 1: 17 articles [1,2,3,4,5,19,20,24,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44];

- Group 2: 23 articles [1,2,3,4,19,20,24,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50];

- Group 3: 24 articles [1,2,3,4,19,20,24,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58];

- Group 4: 14 articles [1,2,3,4,19,20,33,36,38,39,41,42,43,53].

It is shown that 26% of the articles (Group 4) include all three of the targeted concepts. The concept of conceptual design occurs together with the other two concepts at the highest rate (Group 2 and Group 3). All four groups show percentage values below 50%, indicating that the concepts do not commonly occur together in scientific texts from the research area.

3.1.2. Occurrences of the Imagery Concepts

The concept tokens that were recognized as corresponding to the concept of Imagery Experience (see Table 1) are ten and some of them might be considered significantly different. For example, mental imagery does not have the same meaning as perceptual imagery (see definitions of perceptual imagery and mental imagery Section 1.1.1). However, different scientists discuss imagery in various ways and focus on different applications of the concept. This work aims to explain imagery experiences as conscious experiences. At the same time, mental imagery, perceptual imagery, active vision, and the other targeted concept tokens can all be recognized as experiences of consciousness. Table 3 shows the imagery concept tokens presented in ranked order, based on the amount of articles in which they occur.

Table 3.

The results on occurrences of the imagery concept tokens. All of these tokens correspond to the central concept of imagery experience, though they can also be considered as individual concepts. Among them, mental imagery and motor imagery are the most frequently discussed in the research.

With a meaning related to specific applications, the concept tokens can be regarded as sub-concepts of the central concept of imagery experience. Three groups were defined based on the number of articles in which the concepts occur. It is certain that mental imagery and motor imagery are the ones that are most frequently discussed in the research area. Sensorimotor appears to be a decently discussed aspect of imagery as well, though its representation is notably lower compared to the two dominant terms (Table 3). It is also observed to be an emerging topic in the research, as most of the articles that discuss it were published only in recent years [31,48,50,57,59]. An interesting idea is associated with the concept of a distinctive concept, or the process of introjecting imagery for creating alignment mental images and sensorimotor potentialities [50]. The “imagery experience” concept token presents the central understanding of the research area (Figure 1). It is moderately presented throughout the articles but has few occurrences (Table 3). The representatives of this specific aspect of the imagery concept are works on cognitive architectures [19,20,24], research approaches in cognitive science [27,43,47,60,61,62].

The third group—the rare tokens—indicates that the research area has topics that need more discussion. A representative of the concept of active vision is the article by Mirolli, Ferrauto, and Nolfi [44]. In it, they present a system for categorization of images that is inspired by human active vision. The study was published in the year 2010, which puts it on the verge of inclusion, given the inclusion criteria (minimum year of publication: 2009). The only other article that includes the concept toke “active vision” also presents an idea for artificial modeling inspired by human cognitive phenomena [37]. They mention the token only once but discuss it in terms of enactive theory and direct the reader towards their ideas of visuo-spatial mental imagery. At the same time, the other rare token—"mental model”—is strongly related to spatial imagery. It occurs in seven articles, but only two of them discuss it thoroughly [2,3]. Interestingly, in both of them, the authors present functions of their cognitive architectures (Soar [3] and Casimir [2]) and discuss mental imagery in detail.

The concept of body schema has the most token occurrences from the rare tokens. However, there is a single article that focuses on the concept, and its text shows 48 occurrences of the token [31], which means that 82% of the concept occurrences are found in it. The other study that considerably applies the body schema term (five occurrences) is the one that presents the “introjecting” process [50]. Both of these studies also apply the “sensorimotor” token as well [31,50] and are considerably newer studies.

3.1.3. Metacognition and Artificial Intelligence in the Research Area

The concepts of metacognition and AI have been added in the investigation in order to provide an understanding of how the research area is related to them. In 23 studies (42% of the total), artificial intelligence is mentioned at least once. On the other hand, only 11 studies mention metacognition, and in 7 of them the concept appears only once. There is an article that makes no mention of metacognition, but discusses self-regulation with mental imagery [63], which is in itself a concept associated with metacognition. Three articles discuss metacognition in greater depth [19,20,56] and one mentions it a few times [24], accounting for 7% of the total articles. This strongly suggests that there is a limited research focus on the concept.

As expected, the concept of AI occurs more frequently than metacognition. It was observed that a high number of articles show co-occurrence of the concepts AI and cognitive architecture (18 out of 23). Only 4 articles show any occurrences of the AI concept without any reference to cognitive architecture. The following three studies were selected as they best represent cases of co-occurrence of the concept:

- Integrating imagery into a cognitive architecture for artificially recreating cognition [39];

- Cognitive robotics and mental imagery [4];

- Classifications of social scenarios via EEG signals and artificial agents [57].

3.1.4. Other Topics in the Research Area

The research methodology applied in this study allows the definition of a research area via specific basal concepts. While different concepts can be investigated, only those used to form the criteria define the research area. If cognitive model, cognitive architecture, and conceptual design were the only concepts used to form the criteria, the research area would probably be considerably wider. However, the concept of imagery experience sets some limitations, which leads to less articles discussing all or some of the targeted concepts together. There is still a variety of topics discussed in the articles that passed the defined research criteria. The distinctive topics are sports [56,64], hallucinations [60], emotions [65], aphantasia [66], cognitive penetration [67], mental health [68,69], story understanding [70], reading [62], visual–tactile evaluation [71], augmented reality [72], and product design [73]. The articles covering these topics focused heavily on mental imagery but narrowly satisfied the defined exclusion criteria (Section 2.1).

Many articles in the research area discuss motor imagery [36,47,59,61,74], which is tightly related to electroencephalography (EEG) measurement studies. This is confirmed by the articles that link mental imagery to brain states via EEG devices [75,76,77]. These studies aim to classify mental imagery, which was also discussed in an article that presents a framework for understanding mental imagery [27].

3.2. Addressing Concept Occurrence Bias

To decrease bias regarding the concept occurrences in the text, this section presents records that have occurrences of given concept tokens only in their reference lists. This analysis was conducted on the imagery concept tokens as they correspond to the central concept of the research area (Figure 1).

Embodied cognition, or more precisely, its concept token, was not regularly found in the eligible articles (8 out of 55). Moreover, in three of the records, the concept emerged only in the reference list [43,52,53]. The indicators are the same for the “body schema” concept token. Only one out of the six shows a significant amount of 48 occurrences [31] simply because it mainly discusses body schema in cognitive agents. The other five have only one mention of the token and four of them include it in the reference list. The concept of sensorimotor is more regularly discussed in the research here; 16 out of 55 articles show occurrences of it. However, in five of them, the concept token appears only in the reference list.

The token of “active perception” occurred only in three studies [4,37,44] and in the one discussing cognitive robotics [4], it is in the reference list. Similarly, the “active vision” token appeared only in two articles [37,44], which also included “active perception”. Generally speaking, these concepts are either discussed in an article dedicated to them or appear in the reference list.

3.3. Marginally Eligible Studies

Originating from the understanding of the research area (Figure 1), articles can be on the verge of inclusion either because they contain very few occurrences of the peripheral concepts (cognitive model, cognitive architecture, and conceptual design) or of the central concept group (imagery experience). The two categories of articles that are just within the boundaries of the research area adhere to the following criteria:

- Have a very low frequency of tokens corresponding to the central concept (imagery experience) [55,67,68];

- Have a very low frequency of tokens corresponding to the peripheral concepts (cognitive model, cognitive architecture and conceptual design) [59,64,67].

This makes a total of five records that are marginally eligible. It is important to note that a scientific work falls within the research area only if it presents a significant occurrence amount of both the peripheral and the central concept groups. Defined in this way, the results indicate that 55 articles belong to the research area, but 50 are considered as representable of it.

4. Discussion

By observing the publication rate, it can be claimed that the defined research area has recently gained interest (Figure 3). However, less than 30% of the scientific texts show occurrences of all three expanding concepts (Table 1) together. This means that the research area can be solidified if more studies discuss conceptual design of cognitive models that can be used as cognitive architectures, which allow the conduction of cognitive simulations of mental imagery. Formulating classifications of mental imagery types [18,26,27,77] by viewing them as imagery experience types [18,24] would provide solid approaches for explaining consciousness, learning, and imagination. Systems for cognitive monitoring, learning, and decision support would be capable of prompting the user toward “performing” thoughts that lead to beneficial results. Derived from the Attention as Internal Action theory, such thoughts can be seen as result of internal decision making based on triggering information coming from the external [24] or internal environment [19].

4.1. Common Patterns

The frequency of concept occurrences was used as a measure to indicate the relative emphasis of specific ideas within the research area. However, a deeper analysis is required to determine how the leading concepts in the field coexist and what subsidiary topics are associated with them. If similar understandings and applications are identified across different studies, an integrative framework could be solidified. It was decided that the different applications of imagery should be investigated based on the four groups of concept co-occurrences (Section 3.1.1).

Group 1, in which the concepts of cognitive architecture and cognitive model coexist, shows a common topic. Several articles discuss imagery as an element of spatial knowledge and suggest that rational agents enhanced with such information can solve more complex problems [1,2,3,4]. These articles also share the view that internal representations can improve the problem-solving abilities of rational agents [36,37,38]. The cognitive architectures that represent these ideas in the research area are Casimir [2] and Soar [3]. The ACT-R architecture is said to have perceptual-level representations [3], but these representations are rather associated with the external environment and are not a form of mental imagery. The computational approach for diagrammatic imagination DRS [38] appears to be applicable in this area, as it links symbolic and spatial representations. The study also presents the idea that the ACT-R can also integrate internal representations for problem solving [38]. Overall, studies in this group are inspired by imagery experiences and focus on presenting designs of cognitive architectures for problem solving. They fall within the computational field and propose ways to integrate knowledge from human cognition into artificial agents. This supports the foundational understanding in Section 1.1.2 that a cognitive architecture is associated with computational solutions designed to be implemented in machines for problem solving.

Group 2 represents articles with co-occurrences of the concepts of cognitive model and conceptual design (Section 3.1.1). A common idea shared among these studies is that mental imagery functions as an operator that establishes an internal simulator for the agent [33,34,45,47,48,50]. This sub-area is associated with clinical psychology and psychotherapy [46], neuroscience [34], experimental psychology [24,33], and language science [50]. This implies that Group 2 is associated with the human-oriented aspects of the research area.

Group 3 includes works that represent the concepts of conceptual design and cognitive architectures. Most of the papers treat mental simulation as a mechanism for conducting planning creativity. Conceptual design is viewed as an activity that produces internal representations that allow the agent to test motor actions before execution [51,53,54,58]. As a product of design, a simulation turns out to be the bridge between conceptual and perceptual processes [58]. Additionally, planning, predictive modeling, and anticipation are embedded in the text and are recognized as metacognitive processes [56]. On the other hand, the articles in Group 3 share the common focus on computational systems for conceptual thinking [37,39,40,41].

In general, the research area can be divided into two sub-areas with their representative studies:

- Cognitive architectures as mechanisms that incorporate imagery for problem solving and action simulation [1,2,3,4,36,37,38,39,40,41,53];

- Cognitive models as a research frameworks and tools for explaining imagery experiences [19,24,33,34,46,47,50].

4.2. Future Directions

If a single general classification model is solidified and supported by neuropsychological research, many scientists could use it as an underpinning to explore diverse applications in cognitive computation. Different theoretical frameworks would be subsumed under the aegis of a comprehensive Imagery Experience Theory and thus would provide applications in different technological endeavors such as electroencephalography (EEG) investigations for evaluating mental imagery [76,77] and the simulation of learning [21] and cognitive evaluation [24]. The following directions were identified for works in the research area:

- Researching neuroscientific evidence for the establishment of imagery experience types;

- Conducting experimental investigations for building relations between action and imagery experiences;

- Designing cognitive architectures for imagery experience types and applying them for various purposes.

The solidified understanding of the two concepts as sub-areas in the research area allows a clear perspective for future goals. Both computationally oriented cognitive architectures and cognitive models for the explanation of cognitive experiences can be targeted for establishing imagery experience types based on neuroscientific evidence. The conduction of experimental investigations is more closely associated with the sub-area of cognitive models, as it requires researchers to explain actual cognitive experiences. Designing cognitive architectures that can be applied for various purposes, such as complex problem solving [2,3], cognitive monitoring [24], reproducing diagrammatic imagination [38], and others, is a goal direction that can draw inspiration from solidified cognitive models and cognitive architectures. If experimental evidence and neuroscientific studies lead to a general comprehensive model of imagery experiences [18], cognitive architectures that aim at simulating cognition would have a scientific foundation and would provide further evidence through the simulations conducted with them.

The question about consciousness has always generated inquiries that can be investigated in different ways. The fields of cognitive computation and computational cognition are both new pathways for explaining consciousness. If neuroscientific evidence presents models of imagery experience types, these fields would develop by providing new social and cognitive technologies for education. Decision support systems would be more attuned to invisible human experiences and would better support these decisions. In general, understanding consciousness simply means understanding ourselves. That is why metacognition is considered a key to explaining conscious experiences and the thoughtful methods through which humans can improve their own selves.

Based on the results from this work, a new research alley remains dimly investigated; the classification of metacognitive imagery experiences [19]. If new ways are found to prompt a subject to experience such cognitive phenomena, novel methods for faster and more beneficial learning would be provided via digital tools [78]. Furthermore, such prompts would be applicable in developing the so-called “meta-imagery” [56], which would improve athlete performance.

4.3. Applicable Theoretical Frameworks

A requirement was set for this work to provide directions for researchers in different fields who aim to define models of imagery experience types. That is why this section discusses general theoretical frameworks that can be applied for different purposes.

4.3.1. Framework for Conceptual Viewpoints of Mental Imagery

If a research team aims to investigate the research area, the framework for understanding mental imagery is an applicable choice [27]. In the context of the framework, a mental image is comprehended as an experience, which has the purpose of being implementable in different fields. This comprehension is not limited only to the visual modality of imagery, but includes the other sensory modalities as well. The framework has found some application in product design [73] and provides three perspectives for conceptualization of imagery in research, as follows:

- Modality: visual, multisensory, and emotion.

- Process: The relation between cognitive processes, memory, imagination and intentions.

- The dimension of abilities: vividness [26].

4.3.2. Action Cycle Theory

The Action Cycle theory of perception and mental imagery is a promising framework that can be applied to explain types of imagery experiences [18]. It describes six types of imagery experiences as modules in a system that are supported with neuroscientific evidence from studies on the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum, and the hippocampus [79,80]. Some of the modules are linked to some of the others, which provides knowledge of how each influences the others. Most of them are reciprocal; they have an influence on and can be influenced by their neighbor. The distinctive knowledge in the system is that goals that are based on an experience of affect are not influenced by the Schemata module. The latter represents a type of imagery, during which a personality experiences a sensorimotor template or other mental models that reflect “commonalities across multiple experiences of objects and actions” [18].

The Action Cycle Theory has been applied to explain conscious experiences and vividness of an imagery [17]. Additionally, it has been used as a scientific support to explain the occurrence of crisis phenomena [20]. Also, it has been used as underpinning in the development of cognitive architectures [21,24].

Generally, the following characteristics were extracted for the Action Cycle Theory framework:

- It provides six types of imagery experiences supported with neuroscientific evidence.

- The model provides knowledge of relations of influence between the imagery types.

- The theoretical framework hypothesizes other modalities but is primarily oriented toward the visual modality of an imagery.

- Separately, the six types are not limited to being either visual perceptual or visual mental imagery.

- There are no restrictions on which imagery experience type can or cannot be conscious or subconscious/unconscious.

4.3.3. Attention as Internal Action Theory

The other theoretical framework that can be used by researchers for the purpose of designing models of related imagery experiences is the theory of Attention as Internal Action [24]. The theory is based on a theoretical approach that combines the formulation of the cognitive cycle, as explained by the Global Workspace Theory [12,23] and the Action Cycle Theory [18]. However, it proposes an additional phase—the internal decision making phase—in the cognitive cycle iteration that occurs at the start of the originally defined conscious phase [12,23]. A conscious experience is explained as a phenomenon of two consecutive occurrences [24]:

- Internal decision making: The internal agent is deciding between the information entities that were formed in the unconscious phase by the unconscious automatic processes.

- Conscious imagery experience: The internal agent executes the so-called internal action, which is a form of a conscious observation of the information provided by the unconscious automatic processes.

Because of the manner in which these two occurrences were explained—in terms of communication between the automatic unconscious processes and the internal agent—the Two-cause Internal Conjunction is defined [24]. This approach can be used by researchers to explain conscious and unconscious imagery experience types without being restricted to the ones defined in the existing models of the theory. The researchers in the theory have the ultimate goal to design and support with scientific evidence a General Internal Model of Attention [19]. There are already some versions of the GIMA cognitive architecture [19,21,24], which defines types of imagery experiences, by using the model of the Action Cycle Theory as support. However, not all of the relations between the components (the imagery types) have solid scientific support. Nevertheless, future researchers that use the theoretical framework can extend the GIMA model by providing more scientific evidence.

Investigators can apply the framework to research imagery experience types of metacognition. The theory of Attention as Internal Action provides a foundational explanation of metacognitive experiences [81,82], which is supported by the metacognitive model of planning, monitoring, and evaluation [83]. A systematic review on studies from educational science, learning, cognitive computation, and other disciplines have solidified the model in terms of the theory [19].

The theoretical framework provides applications for measuring and computationally reproducing the human cognitive cycle [24]. A foundation was established that explains how the perceptual and motor imagery experience types are related to the continuous flow of sensory information. Additionally, the Discrete Motor Execution hypothesis was formulated to investigate the theory’s explanation on how a motor imagery produces voluntary motor actions [24]. The cognitive test design applied in examining the hypothesis can be used by researchers to study imagery experiences defined within the time frames of the cognitive cycle.

4.3.4. Comparison of Applicable Frameworks

This systematic review provided results that support a growing research area focused on integrating imagery into models inspired by human cognition. These models often represent either human or artificial agents and are applied for various purposes, such as problem solving, simulating future states and actions, and explaining cognitive experiences. The central research focus in this area is to classify imagery experience types and integrate them into models. Three frameworks were discussed, as they were found to be applicable for such purposes: the Conceptual Viewpoints of Mental Imagery (CVMI) [27], the Action Cycle Theory (ACT) [18], and the theory of Attention as Internal Action (AIA) [24]. To guide researchers in choosing the framework that best fits their needs, Table 4 presents comparative characteristics.

Table 4.

Comparative characteristics that aim to direct researchers to select the framework that best fits their goals. The abbreviations correspond to Conceptual Viewpoints of Mental Imagery (CVMI), the Action Cycle Theory (ACT), the theory of Attention as Internal Action (AIA), and the General Internal Model of Attention (GIMA). The CVMI framework is generally oriented toward classifying and structuring knowledge about the nature of imagery. In contrast, the ACT and AIA theories are based on ideas about consciousness, the cognitive cycle, and decision making.

An important note is that the CVMI framework provides three general types of mental imagery which gives researchers the freedom to specify their own subtypes [27]. The ACT framework defines six imagery experience types, with the distinctive modules of Affect, Goal, and Other’s Actions [18]. In contrast, the AIA framework aims at higher type specification and links imagery experiences to memory processes [24]. The ACT’s six modules of imagery are fully defined and supported with neuroscientific evidence. On the other hand, the causal relationships between the modules have yet to be hypothesized and require further research [18]. The CVMI model is based on solid research and is fully specified. It includes three general types of imagery, while the GIMA architecture presents seven imagery experience types [19]. Some of these types, such as perceptual and motor internal actions and the three types of metacognitive experiences, have experimental [24] and reviewed [19] evidence. However, the GIMA still requires external validation.

4.4. Limitations and Characteristics of the Research Approach

This systematic review followed the PRISMA 2020 reporting guideline [84] (see Supplementary Materials for more details). The approach used in this work for identifying concepts based on corresponding tokens is a relatively new methodology and is considered unconventional. The research included counting concept occurrences in the reference list for faster data collection. This is a weakness of the methodology, which is why the additional analysis presented in Section 3.2 was conducted. Another limitation is that the researcher needs a preliminary understanding of the concepts to define the text tokens that best correspond to a concept. If different text tokens such as “mathematical model” and “conceptual model” are defined to correspond to “model”, the resulting research area becomes too broad. Represented by fifty studies (Figure 2), the research area is considered to exist; however, different research methodologies can be used, and the one applied in this work is only a suggestion.

The methodology is applied as a way to identify research patterns based on the co-occurrence of concept tokens extracted from full scientific texts. This approach can be related to geographical mapping techniques such as bibliometric concept maps; however, some differences exist. In this methodology, a concept is tightly related to different specified textual representations. For example, the approach may differentiate between two concepts of “model”: one represented by “mathematical model” and the other by “conceptual model”. This allows researchers to define a concept more strictly and, at the same time, search its occurrences and map them to other concepts.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a significant rise in interest in the research area defined by the applied research methods. The year 2025 appears to mark the beginning of a new expansion in research. It is expected that more scientific texts will be published presenting conceptual designs of cognitive models and cognitive architectures of mental imagery. The distinction between human-oriented cognitive models and a computationally directed cognitive architecture was solidified, outlining several common topics. Practical applications of the models in the research area were identified, such as integrating imagery into artificial agents for problem solving, exploring of imagery in terms of conscious experiences, and evaluating and simulating mental states. Applicable theoretical frameworks and research approaches were presented to help bridge the gap between the imagery experience concepts and research on cognitive models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13121051/s1: The sample for the bibliometric and content analysis was selected in accordance with the principles recommended for Systematic Literature Reviews—PRISMA [84].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.U. and G.T.; methodology, T.U. and G.T.; software, T.U.; validation, T.U.; formal analysis, T.U. and M.S.; investigation, T.U., M.S. and G.T.; resources, T.U.; data curation, T.U.; writing—original draft preparation, T.U.; writing—review and editing, T.U. and G.T.; visualization, T.U.; supervision, G.T.; project administration, G.T.; funding acquisition, G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the scientific research project No. KΠ-06-ΠH77/6 “Exploring methods for cognitive development with a digital simulator game by developing artificial intelligence and neurofeedback systems”, under the contract KΠ-06-ΠH77/6 with the National Science Fund, supported by the Ministry of Education and Science in Bulgaria.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results can be found at https://hramlight.tu-sofia.bg/data/research_data/reviewing_the_need_for_designing_conceptual_models.xlsx (accessed on 17 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lathrop, S.D.; Laird, J.E. Extending Cognitive Architectures with Mental Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Artificial General Intelligence (2009), Arlington, VA, USA, 6–9 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis, H.; Barkowsky, T. Casimir: An Architecture for Mental Spatial Knowledge Processing. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2011, 3, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lathrop, S.D.; Wintermute, S.; Laird, J.E. Exploring the Functional Advantages of Spatial and Visual Cognition from an Architectural Perspective. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2011, 3, 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, J.E. Toward Cognitive Robotics. In Proceedings of the SPIE—Unmanned Systems Technology XI, Orlando, FL, USA, 14—17 April 2009; Gerhart, G.R., Gage, D.W., Shoemaker, C.M., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2009; p. 73320Z. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom Paul, S. Mental Imagery in a Graphical Cognitive Architecture. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, J.E.; Newell, A.; Rosenbloom, P.S. SOAR: An Architecture for General Intelligence. Artif. Intell. 1987, 33, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, D.D. Image and Brain: The Resolution of the Imagery Debate. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 1222–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosslyn, S.M.; Thompson, W.L.; Ganis, G. The Case for Mental Imagery; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-19-517908-8. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, D.F. Consciousness, Mental Imagery and Action. Br. J. Psychol. 1999, 90, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecher, D.; Van Dantzig, S.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Concepts Are Not Represented by Conscious Imagery. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2009, 16, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. Look Again: Phenomenology and Mental Imagery. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2007, 6, 137–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madl, T.; Baars, B.J.; Franklin, S. The Timing of the Cognitive Cycle. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J. The Contribution of Working Memory to Conscious Experience. In Working Memory in Perspective; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baars, B.J.; Franklin, S. How Conscious Experience and Working Memory Interact. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xue, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhang, D. Association of Visual Conscious Experience Vividness with Human Cardiopulmonary Function. Stress Brain 2023, 3, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulfaro, A.A.; Robinson, A.K.; Carlson, T.A. Properties of Imagined Experience across Visual, Auditory, and Other Sensory Modalities. Conscious. Cogn. 2024, 117, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, D.F. I Am Conscious, Therefore, I Am: Imagery, Affect, Action, and a General Theory of Behavior. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.F. The Action Cycle Theory of Perception and Mental Imagery. Vision 2023, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukov, T.; Tsochev, G. Reviewing a Model of Metacognition for Application in Cognitive Architecture Design. Systems 2025, 13, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsochev, G.; Ukov, T. Explaining Crisis Situations via a Cognitive Model of Attention. Systems 2024, 12, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukov, T.G. Cognitive Monitoring of Learning as Experience Via a Semiotic Framework for System Models. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5081756 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Plant, K.L.; Stanton, N.A. The Process of Processing: Exploring the Validity of Neisser’s Perceptual Cycle Model with Accounts from Critical Decision-Making in the Cockpit. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, B.J. The Global Workspace Theory of Consciousness: Predictions and Results. In The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ukov, T.; Tsochev, G.; Yoshinov, R. A Monitoring System for Measuring the Cognitive Cycle via a Continuous Reaction Time Task. Systems 2025, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.G.; Deeprose, C.; Wallace-Hadrill, S.M.A.; Heyes, S.B.; Holmes, E.A. Assessing Mental Imagery in Clinical Psychology: A Review of Imagery Measures and a Guiding Framework. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.F. Phenomenological Studies of Visual Mental Imagery: A Review and Synthesis of Historical Datasets. Vision 2023, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfie, R.L.; Hay, L.A.; Rodgers, P. A Framework for Understanding Mental Imagery in Design Cognition Research. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, G.; Yuji, E.; Costa, P.; Simões, A.; Gudwin, R.; Colombini, E. A General Framework for Reinforcement Learning in Cognitive Architectures. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2025, 91, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sychev, O. Combining Neural Networks and Symbolic Inference in a Hybrid Cognitive Architecture. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 190, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.; Madl, T.; D’Mello, S.; Snaider, J. LIDA: A Systems-Level Architecture for Cognition, Emotion, and Learning. IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev. 2014, 6, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morasso, P.; Mohan, V. The Body Schema: Neural Simulation for Covert and Overt Actions of Embodied Cognitive Agents. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 19, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Alavi, Z.; Dannenhauer, D.; Eyorokon, V.; Munoz-Avila, H.; Perlis, D. MIDCA: A Metacognitive, Integrated Dual-Cycle Architecture for Self-Regulated Autonomy. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2016, 3712–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, S.; Baran, M. The Motor-Cognitive Model of Motor Imagery: Evidence from Timing Errors in Simulated Reaching and Grasping. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2017, 43, 1359–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, M.; Glover, S. TMS over Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Affects the Timing of Motor Imagery but Not Overt Action: Further Support for the Motor-Cognitive Model. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 437, 114125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, S.; Bibby, E.; Tuomi, E. Executive Functions in Motor Imagery: Support for the Motor-Cognitive Model over the Functional Equivalence Model. Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A.J.; Boe, S.G. Imagining the Way Forward: A Review of Contemporary Motor Imagery Theory. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1033493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, J.F.; Freksa, C. Towards Computational Cognitive Modeling of Mental Imagery: The Attention-Based Quantification Theory. Künstl. Intell. 2012, 26, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, B.; Banerjee, B.; Kurup, U.; Lele, O. Augmenting Cognitive Architectures to Support Diagrammatic Imagination. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2011, 3, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintermute, S. Imagery in Cognitive Architecture: Representation and Control at Multiple Levels of Abstraction. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2012, 19, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, J. Towards Visual-Symbolic Integration in the Soar Cognitive Architecture. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2025, 91, 101353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, P.S. Extending Mental Imagery in Sigma. In Artificial General Intelligence; Bach, J., Goertzel, B., Iklé, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7716, pp. 272–281. ISBN 978-3-642-35505-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schack, T.; Essig, K.; Frank, C.; Koester, D. Mental Representation and Motor Imagery Training. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, P.; Frank, C.; Kunde, W. Why Motor Imagery Is Not Really Motoric: Towards a Re-Conceptualization in Terms of Effect-Based Action Control. Psychol. Res. 2024, 88, 1790–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirolli, M.; Ferrauto, T.; Nolfi, S. Categorisation through Evidence Accumulation in an Active Vision System. Connect. Sci. 2010, 22, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, S.E. Mental Imagery in the Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: Past, Present, and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2021, 14, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, F.; Werthmann, J.; Paetsch, A.; Bär, H.E.; Heise, M.; Bruijniks, S.J.E. Prospective Mental Imagery in Depression: Impact on Reward Processing and Reward-Motivated Behaviour. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2021, 3, e3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.M.; Scott, M.W.; Jin, R.; Ma, M.; Kraeutner, S.N.; Hodges, N.J. Evidence for the Dependence of Visual and Kinesthetic Motor Imagery on Isolated Visual and Motor Practice. Conscious. Cogn. 2025, 127, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Caenegem, E.E.; Moreno-Verdú, M.; Waltzing, B.M.; Hamoline, G.; McAteer, S.M.; Frahm, L.; Hardwick, R.M. Multisensory Approach in Mental Imagery: ALE Meta-Analyses Comparing Motor, Visual and Auditory Imagery. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 167, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, L.; Duffy, A.H.B.; McTeague, C.; Pidgeon, L.M.; Vuletic, T.; Grealy, M. A Systematic Review of Protocol Studies on Conceptual Design Cognition: Design as Search and Exploration. Des. Sci. 2017, 3, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, M.; Schneider, S.M.; Fisher, V.J. “Introjecting” Imagery: A Process Model of How Minds and Bodies Are Co-Enacted. Lang. Sci. 2024, 102, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruffi, L.; Küssner, M.B. A Review of Music-Evoked Visual Mental Imagery: Conceptual Issues, Relation to Emotion, and Functional Outcome. Psychomusicol. Music Mind Brain 2019, 29, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, R.S.; Krishna, A. A Review of Sensory Imagery for Consumer Psychology. J. Consum. Psychol. 2022, 32, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, D.; Beetz, M.; Sandini, G. Prospection in Cognition: The Case for Joint Episodic-Procedural Memory in Cognitive Robotics. Front. Robot. AI 2015, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, H.; Moran, A. Does Motor Simulation Theory Explain the Cognitive Mechanisms Underlying Motor Imagery? A Critical Review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrusci, L.; Dabaghi, K.; D’Urso, S.; Sciarrone, F. AI4Design: A Generative AI-Based System to Improve Creativity in Design–A Field Evaluation. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, T.E.; Igou, E.R.; Campbell, M.J.; Moran, A.P.; Matthews, J. Metacognition and Action: A New Pathway to Understanding Social and Cognitive Aspects of Expertise in Sport. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Menassa, C.C.; Kamat, V.R. Siamese Network with Dual Attention for EEG-Driven Social Learning: Bridging the Human-Robot Gap in Long-Tail Autonomous Driving. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, Á.; Pető-Plaszkó, O.; Verebélyi, L.; Gombos, F.; Winkler, I.; Kovács, I. Neurodiversity in Mental Simulation: Conceptual but Not Visual Imagery Priming Modulates Perception across the Imagery Vividness Spectrum. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, R.; Reiner, M. Shared Mechanisms Underlie Mental Imagery and Motor Planning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulfaro, A.A.; Robinson, A.K.; Carlson, T.A. Modelling Perception as a Hierarchical Competition Differentiates Imagined, Veridical, and Hallucinated Percepts. Neurosci. Conscious. 2023, 2023, niad018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A.; O’Shea, H. Motor Imagery Practice and Cognitive Processes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.T.; Schwitzgebel, E. The Experience of Reading. Conscious. Cogn. 2018, 62, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, N.; Cameron, L.D.; Maki, J.; Carter, C.R.; Liu, Y.; Dart, H.; Bowen, D.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Waters, E.A. Mental Imagery-based Self-regulation: Effects on Physical Activity Behaviour and Its Cognitive and Affective Precursors over Time. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.K.; Lovell, G. The Influence of Experience upon Imagery Perspectives in Adolescent Sport Performers. J. Imag. Res. Sport Phys. Act. 2011, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieja, J.M.; Zaleskiewicz, T.; Gasiorowska, A. Mental Imagery Shapes Emotions in People’s Decisions Related to Risk Taking. Cognition 2025, 257, 106082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkvist, A. Aphantasia: In Search of a Theory. Mind Lang. 2023, 38, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnston, D.C. Cognitive Penetration and the Cognition–Perception Interface. Synthese 2017, 194, 3645–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel-Santos, M.A.; Rodríguez-Macías, J.C. Integral Definition and Conceptual Model of Mental Health: Proposal from a Systematic Review of Different Paradigms. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 978804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.; Halldorsson, B.; Creswell, C. Mental Imagery in Social Anxiety in Children and Young People: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigelow, E.; Scarafoni, D.; Schubert, L.; Wilson, A. On the Need for Imagistic Modeling in Story Understanding. Biol. Inspired Cogn. Arch. 2015, 11, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Wang, W. Perceptual Imagery of Soft Sofa Fabrics Based on Visual-Tactile Evaluation. BioResources 2024, 19, 8427–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhan, V.K.; Tam, L.T.; Dung, H.T.; Vu, N.T. A Conceptual Model for Studying the Immersive Mobile Augmented Reality Application-Enhanced Experience. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, E.; Hay, L. Do You See What I See? Exploring Vividness of Visual Mental Imagery in Product Design Ideation. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Toyokawa, K.; Zheng, T.; Shimba, K.; Kotani, K.; Jimbo, Y. Object-Centered Control of Brain-Computer Interface Systems in Three-Dimensional Spaces Using an Intuitive Motor Imagery Paradigm. Adv. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 14, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olza, A.; Soto, D.; Santana, R. Domain Adaptation-Enhanced Searchlight: Enabling Classification of Brain States from Visual Perception to Mental Imagery. Brain Inform. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postepski, F.; Wojcik, G.M.; Wrobel, K.; Kawiak, A.; Zemla, K.; Sedek, G. Recurrent and Convolutional Neural Networks in Classification of EEG Signal for Guided Imagery and Mental Workload Detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Huang, M.; Feng, Y. MBBi-TCNet: Multi-Branch Bi-Directional Temporal Convolutional Network for EEG Classification of Mental Imagery. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2025, 111, 108381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braad, E.; Degens, N.; Barendregt, W.; IJsselsteijn, W. Improving Metacognition through Self-Explication in a Digital Self-Regulated Learning Tool. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 2063–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M. Control of Mental Activities by Internal Models in the Cerebellum. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisman, J.; Buzsáki, G.; Eichenbaum, H.; Nadel, L.; Ranganath, C.; Redish, A.D. Viewpoints: How the Hippocampus Contributes to Memory, Navigation and Cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A. The Role of Metacognitive Experiences in the Learning Process. Psicothema 2009, 21, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, N. A Case Study of an Ignored Facet: Metacognitive Experiences. E-Kafkas J. Educ. Res. 2024, 11, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.D.; Sebesta, A.J.; Dunlosky, J. Fostering Metacognition to Support Student Learning and Performance. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, fe3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]