Abstract

Driven by government subsidies and advertising revenue, air taxis present an innovative solution to alleviate traffic congestion and are poised for growth. However, at their current stage of development, air taxi companies primarily operate short-distance routes within cities and rarely offer intercity services. Moreover, as a new mode of transportation, air taxis experience low levels of consumer trust at present. This study, grounded in the Hotelling model, examines differentiated decision-making scenarios between two competing air taxi service providers. It systematically analyzes how service expansion (specifically, the introduction of intercity services) and advertising strategies affect pricing, market share, and profits. Furthermore, it explores optimal decision-making patterns under external disturbances, providing theoretical support for service providers formulating operational strategies. We constructed a differentiated decision-making game model to simulate competition between Service Provider 1 (which does not offer intercity services but may advertise) and Service Provider 2 (which advertises but may choose whether to offer intercity services). By comparing game equilibrium outcomes under different decision combinations, we identify threshold conditions for key variables (e.g., additional price for intercity services and the advertising discount coefficient). The model is further expanded to incorporate external disturbance factors, allowing for analysis of how such environments influence the profitability of each decision pattern. Research has revealed that 1. offering intercity services can increase a provider’s optimal price and market share, but only if the “additional price for intercity services exceeds the threshold”; 2. both providers choosing advertising services is the optimal strategy, but if the advertising discount coefficient exceeds a reasonable range, it will intensify vicious competition. Therefore, it must be controlled within the optimal threshold to avoid adverse effects; 3. under external disturbance conditions, service providers prefer models that do not involve intercity services, and the “both parties advertise (NTX)” combination is more optimal. If intercity services are necessary, disturbance risks must be carefully assessed, or flexible cost and operational strategies should be implemented to hedge against negative impacts.

1. Introduction

Currently, the issue of traffic congestion in China’s megacities and large cities is spreading from morning and evening rush hours to around the clock. Commuting time keeps increasing, the supply and demand for road resources remain imbalanced, and the efficiency of emergency transportation is low. According to the “2024 Commuting Monitoring Report for Major Chinese Cities,” the average one-way commute time in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou reaches 47.2 min, 44.8 min, and 41.5 min, respectively, with an increase of over 8% compared with 2020. More than 12% of commuters spend over an hour on a one-way trip, which is equivalent to “losing” nearly 25 working days annually to commuting [1]. Take Shenzhen as an example. In 2024, the city’s motor vehicle ownership exceeded 4.2 million, but the total length of urban roads was only approximately 7000 km. These numbers equate to over 600 motor vehicles per kilometer of road—twice the internationally recognized “congestion warning threshold” (300 vehicles per kilometer). During morning and evening rush hours, the average speed of major roads such as Beihuan Avenue and Shennan Avenue often falls below 15 km/h, even slower than the speed of cycling [2]. Data from the emergency department of a hospital in Hangzhou in 2023 showed that 19% of ambulance delays were due to traffic congestion. Among these cases, the longest delay lasted 28 min, which directly affected the treatment efficiency for critically ill patients. Similar situations have been frequently recorded in emergency rescue statistics from cities such as Chengdu and Wuhan [3].

To address the worsening urban traffic congestion and meet the surging demand for efficient travel, urban air taxis (UAT) powered by electric vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) technology have emerged as a transformative solution. Unlike traditional ground transportation, UATs achieve VTOL through designs such as multiple rotors or compound wings, eliminating the need for large-scale runways. They can utilize urban rooftops, open spaces, and similar areas as take-off and landing sites, thereby leveraging low-altitude airspace to avoid traffic congestion and provide increased flexibility and time efficiency for urban and intercity travel [4]. Take the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as an example. This country faces severe traffic congestion and long distances between major cities, creating an urgent need to develop urban air mobility. China’s SDAT Technology (Shanghai Shiji Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) has partnered with UAE-based enterprises; the aircraft model it developed can carry five passengers and reach a cruising speed of 260 km/h [1]. In China, the helicopter passenger route launched between Shanghai and Kunshan serves as a valuable pilot initiative. Shanghai is actively advancing the low-altitude economy and is expected to introduce more advanced UATs in the future. Bookings can be made in advance through channels such as the Kunshan Terminal. Operators also fully consider interfering factors like air traffic control and adverse weather to ensure travel safety and efficiency. UATs are bringing new possibilities for alleviating traffic congestion and enhancing travel efficiency.

The development of the air taxi industry is also driven by two key synergistic forces: government subsidy policies and the emerging advertising economy. On the one hand, government subsidies effectively reduce the travel cost burden for citizens, lower market entry barriers, and accelerate the promotion and application of air taxi services [5]. On the other hand, air taxis, characterized by their novelty and high visibility, hold significant advertising value. This value not only opens up new marketing channels for advertisers but also enables air taxi operators to reinvest advertising revenue into service optimization (e.g., expanding fleet size and enhancing passenger experience), forming a sustainable business cycle [6].

However, the commercialization and long-term sustainable development of air taxis still face numerous critical challenges. For example, the current air taxi service in Shenzhen operates only about 10 flights per day, highlighting the urgent need to increase service capacity while ensuring service quality. For air taxi operators, two core issues are particularly prominent: pricing strategy and service innovation. Excessively high prices will suppress market demand, whereas excessively low prices may lead to operational losses because of substantial fixed costs (e.g., aircraft procurement, maintenance, and airspace usage fees). Additionally, how to meet diverse travel needs, such as business travel, emergency transportation, and leisure travel, and continuously improve user experience remain unresolved challenges for operators.

Especially in a duopoly market structure, air taxi operators face complex strategic trade-offs: whether to expand into intercity services, whether to invest in advertising, and how to respond to external disruptions (e.g., extreme weather, policy adjustments, or fluctuations in energy prices). These decisions not only affect the operators’ own market share and profitability but also reshape the competitive landscape of the entire industry.

Against this backdrop, this study aims to explore the optimal strategic choices of air taxi operators in a duopoly context. By incorporating government subsidies and advertising mechanisms into the theoretical analysis framework, this study addresses the following three core research questions:

- In a duopoly market, should air taxi operators offer additional intercity services? If so, how should the optimal premium for such services be determined?

- For the emerging air taxi industry, is advertising investment a viable strategy? If viable, how does the advertising discount coefficient affect the profits of the operators and their competitors? What is the optimal discount coefficient?

- What effect do external disruptions have on air taxi operators? How should operators mitigate these effects?

To answer these questions, this study constructs a duopoly competition model based on the Hotelling linear market model [7]. Two air taxi service providers (Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2) are considered: one provider does not plan to offer intercity services at all, whereas the other retains the option to do so. Service Provider S2 consistently invests in advertising, whereas Service Provider S1 decides whether to invest in advertising. Based on this setup, four pricing and service strategy models are analyzed:

•NO mode (Service Provider S2 does not offer intercity services; S1 does not engage in advertising): Neither Service Provider S1 nor S2 offers intercity services; S2 invests in advertising, but S1 does not.

•NT mode (Service Provider S2 does not offer intercity services; S1 engages in advertising): Neither Service Provider S1 nor S2 offers intercity services; S1 and S2 invest in advertising.

•GO mode (Service provider S2 offers intercity services; S1 does not engage in advertising): Service Provider S1 does not offer intercity services, but S2 does; S1 does not invest in advertising, but S2 does.

•GT mode (Service provider S2 offers intercity services; S1 engages in advertising): Service Provider S1 does not offer intercity services, but S2 does; S1 and S2 invest in advertising.

In addition, an extended model considering the effect of external disruptions is included. Equilibrium solutions under each mode are derived, and the influence of different service modes on the equilibrium results is examined. Furthermore, this study investigates how, in the context of government subsidies, air taxi service providers’ innovative service strategies (offering intercity services), additional prices for such services, advertising investment and intensity, and external disturbance factors affect the strategy choices of the providers and their competitors. Several interesting conclusions are drawn:

First, in the duopoly competitive market of air taxi service providers, one provider may choose to offer intercity services. By doing so, it can increase its optimal price and market share, thereby achieving higher profits. If a service provider chooses to offer intercity services, the profits of both providers increase as the additional price for such services rises. However, the provider must ensure that this additional price exceeds a critical threshold—only then will its profit from providing intercity services surpass that from not providing them.

Second, in the same market structure, the advertising discount coefficient of one provider exerts a significant competitive effect on the other’s profit. Furthermore, competitors’ advertising strategies have a strong moderating effect on a provider’s own profit. If the other provider also invests in advertising, the marginal effect of its advertising discount coefficient on its own profit increases. When a service provider chooses to invest in advertising, an optimal threshold exists for its advertising discount coefficient—it should be neither too high nor too low. At this threshold, the profit difference between conducting advertising and not conducting advertising is maximized.

Third, under a disturbed environment, service providers should prioritize modes that do not involve intercity services. The mode with mutual advertising promotion (the NTX mode) performs more optimally under such conditions. If providers decide to offer intercity services, they must carefully assess disturbance risks or adopt flexible cost and operational strategies to offset negative effects.

Compared with existing studies in the field of air taxis, this study makes the following contributions:

- (1)

- It introduces two synergistic driving forces—government subsidies and the advertising economy—into the study of duopoly air taxi markets, expanding the dimensions of strategic choice analysis. Previous studies have mostly focused on the technical feasibility of air taxi or the behavior of a single market entity, lacking a unified theoretical framework that accounts for interactions between multiple variables.

- (2)

- It examines differentiated pricing and service strategy decisions of duopoly air taxi service providers. Using the Hotelling linear market model, the study designs four strategy models and an extended model considering external disturbances. Key variables, such as intercity service premium and advertising discount coefficient, are incorporated. Traditional applications of the Hotelling model tend to emphasize price competition alone, without aligning with the diverse service types and frequent external disturbances present in the air taxi industry.

- (3)

- Most of the existing literature on air taxi strategy remains qualitative and disconnected from the industry’s transition from technical feasibility to commercial sustainability. By contrast, this study quantitatively derives key insights, including the critical value for the optimal intercity service premium, the two-way competitive effect of the advertising discount coefficient, and its optimal threshold. It also proposes sustainable strategies for managing external disturbances, filling the gap between quantitative research with practical decision-making in this field.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature, and Section 3 elaborates on model assumptions and the symbol system. Section 4 systematically analyzes the equilibrium solutions under different strategies in the basic and extended models; Section 5 compares these equilibrium solutions in a non-disturbed context. Section 6 provides numerical analysis and management implications, and Section 7 summarizes the research findings. Detailed proofs are provided in the Appendix A.

2. Literature Review

This paper primarily covers research in three areas: (1) research on Hotelling model; (2) research on the low-altitude economy; (3) research on duopoly competition; and (4) research on advertising strategies. In this section, we review the relevant research in each field.

2.1. Research on Hotelling Model

Grau-Climent conducted numerical simulations of Hotelling games with elastic demand [8]. The implemented simulation techniques enabled monitoring the correctness of analytical solutions when available—such as in monopoly models—and explored scenarios where analytical solutions were unavailable or difficult to find. Atewamba constructed an empirical Hotelling model incorporating technological progress and population-dependent extraction costs, empirically testing whether the model’s assumptions and predictions aligned with patterns observed in the data [9]. Esteves and Carballo-Cruz extend the classical Hotelling model by addressing two key constraints: the assumption of perfectly inelastic demand and the exclusion of quantity-related transportation costs [10]. They find that equilibrium prices and profits increase as stores become more differentiated, bridging a significant gap in the spatial competition literature. Our findings indicate that, consistent with the classical Hotelling model, prices and profits increase with store differentiation, bridging a significant gap in the spatial competition literature. Esteves and Shuai leverage the Hotelling model to assess the impact of firms’ ability to charge personalized prices on profits and welfare in markets where consumer demand is sensitive to price changes [11].

2.2. Research on the Low-Altitude Economy

In the field of the low-altitude economy, current academic research mainly focuses on the application of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). For instance, through research, Zhou found that high-energy-density fuel cells are more competitive than UAV batteries and internal combustion engines in terms of weight, cruising performance, and carbon footprint. The carbon offsets generated during the UAV’s operation phase can effectively reduce the lifecycle carbon footprint of UAVs. Further implementation of policies, standards, and regulations regarding UAV safety, data privacy, regulatory rules, and ground infrastructure is required to promote the role of UAVs in enabling a sustainable low-altitude economy within sustainable and smart cities [12]. Tan et al. reviewed the current status and research progress of UAVs, as well as their policy impacts on the low-altitude economy. They analyzed the key technologies of UAVs and interpreted their roles and implementation mechanisms in scenarios such as urban carbon reduction, renewable energy assessment, and pollution monitoring and source tracing [13]. Li and Zeng proposed the KESO autonomous positioning method for drones, providing a reference for drone positioning in urban environments under the low-altitude economy [14]. Li and Du developed an iterative algorithm to study the dynamic optimization of eVTOL (electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing) reserves at charging stations and total costs under fluctuating order surges and charging constraints. To optimize costs, they proposed strategies such as multi-cycle decentralized scheduling or low-frequency centralized decision-making. Their findings revealed that cost parameters and demand characteristics collectively shape the incremental decision-making of eVTOL and their economic performance [15]. Wang Y demonstrated that UAVs can improve resource utilization efficiency in precision agriculture [16]. Fan et al. proposed the integration of social radar and social vision based on the critical role of intelligent vehicles in advancing the low-altitude economy, aiming to deliver more efficient and safer services for this sector [17]. In terms of the future low-altitude intelligent transportation system, Huang et al. proposed a framework for a future low-altitude intelligent transportation (LAIT) system based on the hierarchical architecture of cyber–physical systems (CPS), providing potential solutions for urban air transportation. They comprehensively discussed the current status, challenges, and future development prospects of LAIT from three key perspectives: system architecture, infrastructure, and key technologies [18].

2.3. Research on Duopoly Competition

Research on duopoly competition focuses on multiple dimensions. Wang Yao conducted an analysis using the Hotelling model and found essential differences between the “series duopoly model” and “parallel duopoly model”: the series model may have lower profits than a monopoly due to the “double marginalization effect”, while the parallel model reduces prices and increases traffic flow through price competition [19]. Zhao et al. explored the complex dynamics of demand uncertainty in duopolies within the framework of the “carbon emission trading mechanism” and studied the complexity of adjusting the dynamic evolution path of competitive strategies between the two entities [20]. Fanti examined the relationship between market competition and corporate tax evasion in a duopoly with differentiated products under the Bertrand and Cournot conjectures [21]. Chen et al. focus on differentiated duopolies involving both domestic and foreign firms in the trade sector, analyzing the effects of product differentiation and productivity variance on equilibrium outcomes. They find that differentiated products and tariffs exert differing impacts on relevant entities and that the optimal tariff requires determination based on parameters and the specific duopoly model [22]. Kuang et al. pointed out that in the case of road delay hours, the series model may reverse its profit disadvantage [23]. The impact of government policies on duopoly competition has also been thoroughly explored. In the field of environmental regulation, the implementation of emission taxes can change the stability of oligopoly equilibrium. Gori’s research shows that the optimal tax rate should be lower than the marginal social damage cost of emissions, so as to balance the efficiency of market competition and the goal of pollution control. In addition, the literature on platform competition emphasizes the role of “multi-homing behavior” in promoting matching efficiency [24]. Overall, research on duopoly competition focuses on the interaction between market structure, user behavior, and policy intervention, providing a theoretical framework for understanding the competitive dynamics of the modern transportation service market.

2.4. Research on Advertising Strategies

Numerous scholars argue that online advertising placement is a crucial factor influencing brand reputation, and increasing advertising investment can enhance brand reputation [25]. Among them, Jorgensen holds that advertising placement exerts a positive impact on brands [26]. Thomas suggests that advertising spillover effects occur when the local advertising level is higher or lower than the locally optimal advertising level due to the influence of other markets or individuals on mass advertising decisions [27]. Aust and Buscher studied cooperative advertising, pricing strategies, and whether competing retailers cooperate with each other. They found that cooperation between the two retailers is more beneficial to manufacturers but offers no benefits to the retailers themselves [28]. Pricing strategies are closely associated with advertising placement. Bi et al. explored the relationship between advertising and financing decisions in online supply chains, and pointed out that advertising can reduce risks and is always beneficial; electronic platforms are willing to support retailers only when retailers determine the advertising level [29]. Sayadi and Makui analyzed the advertising decisions made by retailers and manufacturers for offline retail and online channels, respectively. They demonstrated that factors such as the price difference between the product’s online price (set by the manufacturer) and wholesale price, advertising effectiveness, and advertising costs all have a significant impact on advertising decisions in the equilibrium state [30].

3. Problem Description and Assumptions

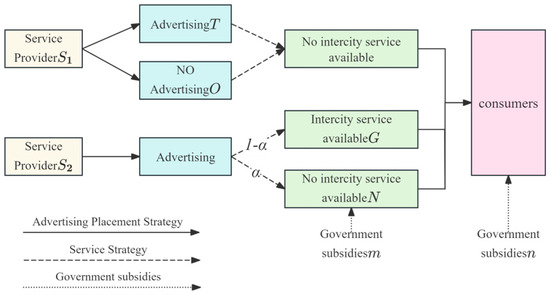

This paper constructs a duopoly market consisting of two air taxi service providers (Provider S1 and Provider S2): one provider completely disregards offering intercity services, while the other considers providing them. Simultaneously, Provider S2 continuously invests in advertising campaigns, whereas Provider S1 deliberates whether to engage in advertising (as illustrated in Figure 1 and Table 1). The objective of each provider is to determine service pricing that maximizes profits [31]. For example, the domestic air taxi duopoly represented by EHang Intelligent (Guangzhou EHang Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) (focusing on local services, not yet involved in intercity services, and with strong advertising efforts) and Shihui Technology (planning intercity services, with relatively lagging advertising) competes for market share through differentiation strategies to achieve profit maximization.

Figure 1.

Market structure.

Table 1.

Strategy differences visualization table.

Service Provider: Assume the leftmost position 0 represents Service Provider 1, with price P1 and unit cost C1; the rightmost position 1 represents Service Provider 2 [32], price P2, unit cost C2 (C1=C2) [33,34]. Service Provider 1 only offers intracity transportation services, not intercity services, while Service Provider 2 can provide intercity services. When Service Provider 2 offers intercity services at price P2s, it incurs additional cost kP2s, where k is the cost coefficient for intercity services provided by Service Provider 2, and , generating additional utility V0 [35].

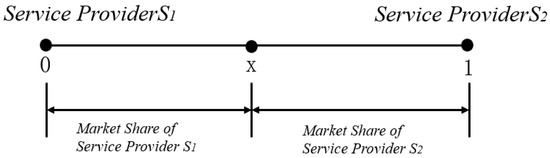

Consumer: Assume consumers are uniformly distributed between two service providers. Starting from point x, consumers choose one service provider between Provider 1 and Provider 2, as shown in Figure 2. Provider 1’s market share is distributed in , while Provider 2’s market share is distributed in . The transportation cost for consumers to reach a service provider is proportional to the distance from the provider, with a unit transportation cost of t. If traveling from Provider 1, the transportation cost is tx; if traveling from Provider 2, the transportation cost is t(1−x) [36,37]. This Hotelling linear model is widely used to characterize price competition among firms under horizontal differentiation, as seen in studies by Li [38], Xu and Huang [39], and Wang et al. [40]. Assume consumers’ maximum willingness to pay for both providers is V and that willingness to pay V is sufficiently large.

Figure 2.

Duopoly market.

Government Subsidies: As the low-altitude economy remains in its nascent stage, public awareness and trust in this sector remain low. Consumers require considerable time to embrace and trust air taxi as a novel mode of transportation. To enhance economic, cultural, and personnel exchanges between regions, promote coordinated regional development, and accelerate the growth of the low-altitude economy industry, the government will provide subsidies to enterprises offering intercity services at a fixed rate of m, [41]. For instance, Zhuhai’s Measures to Support High-Quality Development of the Low-Altitude Economy grants a subsidy of CNY 300 per flight to low-altitude economy enterprises that establish and commercially operate (public ticketing) approved eVTOL passenger intercity routes within Zhuhai. Simultaneously, to encourage enterprises, institutions, and citizens to use air taxis, the government provides consumer cost subsidies at a rate of n, . For instance, Shenzhen’s Pingshan District introduced a fixed-route helicopter subsidy policy in 2024, reducing air commuting costs to CNY 980 per person. Furthermore, Longgang District subsidizes public-benefit “air taxi” routes. Taking the Galaxy Twin Towers to Bao’an International Airport as an example, chartered flights under government subsidies are significantly below market rates, costing only CNY 6800.

Advertising Placement: As an innovative transportation mode, air taxis face low consumer recognition and trust in this new travel option. To establish a positive brand image and enhance consumer utility, service providers will choose to advertise to increase perceived value and expand market demand [42,43]. At this stage, service providers may choose to advertise or refrain from advertising. If advertising is employed and includes coupons, this is defined as the advertising discount coefficient . Regarding advertising intensity , referring to research by Aust and Buscher [29], since the marginal cost of advertising investment increases continuously, the cost of advertising placement is assumed to be [44]. For specific parameters, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Symbol definitions.

Government subsidies alleviate the initial financial pressure on air taxi companies by covering their R&D, operational, and partial marketing costs. This enables them to invest in advertising campaigns with the necessary resources and confidence, effectively underpinning these promotional efforts. Meanwhile, corporate advertising translates the cost savings and compliance benefits from subsidies into tangible value for users—such as “lower fares thanks to subsidies” and “Compliant companies are more reliable”. This approach rapidly builds market awareness for air taxis as a new transportation option, attracting consumers. Simultaneously, it provides feedback on user needs to guide government adjustments in subsidy allocation (e.g., shifting from fare subsidies to helipad construction subsidies), making subsidies more precise and efficient, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of government subsidies. This creates a virtuous cycle. Therefore, this paper integrates government subsidies with advertising campaigns to explore optimal strategies for maximizing corporate profits, considering the industry’s initial characteristics of high costs, low trust, and weak demand.

4. Model Developments and Analysis

4.1. The Model

This paper constructs a duopoly market consisting of two air taxi service providers (Provider S1 and Provider S2). Considering whether to engage in advertising campaigns and whether to offer intercity services, the market is divided into four distinct strategies.

4.1.1. Mode NO

In this scenario, neither Service Provider S1 nor Service Provider S2 offers intercity services, so the enterprise receives no government subsidies. However, the government continues to subsidize consumers as usual. Since Service Provider S2 runs advertisements, its consumers receive an advertising discount, while S1’s consumers do not. Both service providers adjust their prices to maximize their respective profits. Consumers deriving final utility from receiving services at point x from either service provider on either end experience identical utility; that is

At this point, the market demand for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 can be obtained as follows:

At this point, the profit functions for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 are, respectively,

Based on the optimality conditions and , we obtain the following:

Proposition 1.

Equilibrium Outcomes under NO Mode:

- (1)

- The optimal price and demand are

- (2)

- The optimal profit function for Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 is

For specific evidence, see the Appendix A.1.

From Proposition 1, we derive the following:

Corollary 1.

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- The optimal prices for Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 are influenced by government subsidies, advertising discount coefficients, unit costs, and transportation unit costs. Both Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2’s optimal prices increase as the government subsidy ratio n to consumers rises. Service Provider 1’s optimal price is inversely proportional to Service Provider 2’s advertising discount coefficient, while Service Provider 2’s optimal price is directly proportional to its advertising discount coefficient. The optimal prices for both Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 are directly proportional to their unit costs C and transportation unit costs t. This indicates that since Service Provider 2 runs advertising campaigns while Service Provider 1 does not, Service Provider 2’s optimal price increases based on its rising advertising discount coefficient, while Service Provider 1’s optimal price decreases based on Service Provider 2’s increasing advertising discount coefficient.

From a management perspective, service providers should design differentiated pricing strategies based on their cost structure (C, t) while comprehensively considering competitors’ strategic behaviors and the policy environment. This approach aims to identify the optimal pricing that balances profit objectives with market competitiveness.

- (3)

- Advertising campaigns by air taxi service providers increase market demand. When neither provider offers intercity services but Provider 1 refrains from advertising while Provider 2 runs promotional campaigns, Provider 2 will capture a larger market share than Provider 1.

This also demonstrates that advertising by air taxi service providers is not merely “spending money to buy traffic.” Instead, it addresses pain points in their emerging market. Advertising may directly drive short-term order growth by expanding potential user reach, building trust, lowering trial barriers, activating latent demand through scenario-based marketing, and boosting conversion rates with conversion tools. Simultaneously, this short-term demand growth will in turn support “infrastructure improvements” and “reduced operational costs,” laying the groundwork for long-term demand expansion.

- (4)

- When , .

This inference indicates that when a service provider chooses to run advertisements at a low cost, the profits achievable exceed those without advertising. Specifically, under certain conditions, the profit

of service provider S2 after advertising exceeds the profit

when no advertising is provided.

This inference does not merely suggest that advertising is beneficial but emphasizes that advertising must be deeply integrated with cost control and meet specific market conditions to achieve profit growth. For businesses, it is crucial to clarify their advertising decision-making logic—shifting from “whether to advertise” to “how to convert advertising into profit.” By combining “advertising with low costs,” companies can transform this into a sustainable profit advantage, avoiding the pitfalls of blind marketing or mere cost compression.

- (5)

- When , ; when , > 0, .

The above analysis indicates that for Service Provider 1, when competitor Service Provider 2 chooses to engage in advertising campaigns with a small advertising discount coefficient, Service Provider 1’s profit will be lower than when the competitor does not advertise. Conversely, when the competitor’s advertising discount coefficient is large, Service Provider 1’s profit will be higher than when the competitor does not advertise. That is, under certain conditions, the optimal profit

achieved after the competitor launches advertising campaigns will exceed the profit

achieved without advertising.

4.1.2. Mode NT

In this scenario, neither Service Provider S1 nor Service Provider S2 offers intercity services, so the company receives no government subsidies. However, the government provides regular subsidies to consumers. Since both S1 and S2 engage in advertising campaigns, consumers of both S1 and S2 receive an advertising discount. Given the fixed and close partnership between Service Provider S2 and its advertising collaborators, this paper sets . Both service providers adjust their service prices to maximize their own profits. Consumers derive equal final utility from receiving services at either end of the spectrum from Service Providers S1 and S2 at point x.

At this time, the market demand for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 is as follows:

The profit functions for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 are, respectively,

Based on the optimality conditions and , we obtain the following:

Proposition 2.

Equilibrium Outcomes under Mode NT:

- (1)

- The optimal price and demand are

- (2)

- The optimal profit function for Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 is

The proof is the same as above.

From Proposition 2, we derive the following:

Corollary 2.

- (1)

- ; .

- (2)

- The optimal prices of Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 are directly proportional to the government subsidy ratio n to consumers. When the government subsidy to consumers increases, the prices charged by service providers also rise. Service Provider 1’s optimal price is directly proportional to its advertising discount coefficient and inversely proportional to Service Provider 2’s advertising discount coefficient. Meanwhile, Service Provider 2’s optimal price is inversely proportional to Service Provider 1’s advertising discount coefficient and directly proportional to its own advertising discount coefficient.

This indicates that when Service Provider 1 increases its advertising expenditure, its service pricing rises accordingly. Conversely, Service Provider 2 lowers its pricing. This occurs because Service Provider 1’s advertising activities exert competitive pressure on Service Provider 2, causing the latter’s market share to decline. Consequently, Service Provider 2 reduces its prices to enhance its competitive advantage.

4.1.3. Mode GO

In this scenario, Service Provider S2 offers intercity services, so the government provides S2 with a subsidy at a rate of m while also subsidizing consumers as usual. Since Service Provider S2 runs advertisements, its consumers receive an advertising discount, whereas S1’s consumers do not. Both service providers adjust their prices to maximize their respective profits. Consumers deriving services from either provider at point x experience identical final utility, meaning

At this time, the market demand for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 is as follows:

The profit functions for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 are, respectively,

Based on the optimality conditions and , we obtain the following:

Proposition 3.

Equilibrium Outcomes under Mode GO:

- (1)

- The optimal price and demand are

- (2)

- The optimal profit function for Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 is

The proof is the same as above.

From Proposition 3, we derive the following:

Corollary 3.

The optimal price for Service Providers 1 and 2 is directly proportional to the unit transportation cost t and inversely proportional to the government subsidy ratio; the optimal price for Service Provider 2 is directly proportional to its advertising discount coefficient. Service Provider 1’s optimal price is inversely proportional to the additional utility V0 provided to consumers by Service Provider 2’s intercity services, while Service Provider 2’s optimal price is directly proportional to the additional utility V0 provided to consumers by its own intercity services. This implies that when Service Provider 2 offers intercity services, it gains a competitive advantage over Service Provider 1, prompting Service Provider 1 to moderately lower its price.

4.1.4. Mode GT

In this scenario, Service Provider S2 offers intercity services, so the government provides S2 with a subsidy at a rate of m while also subsidizing consumers as usual. Since both Service Providers S1 and S2 engage in advertising campaigns, consumers of both S1 and S2 receive an advertising discount. The two service providers adjust their service prices to maximize their respective profits. Consumers receiving services from either provider at point x experience identical final utility, meaning

At this time, the market demand for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 is as follows:

The profit functions for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 are, respectively,

Based on the optimality conditions and , we obtain the following:

Proposition 4.

Equilibrium Outcomes under Mode GT:

- (1)

- The optimal price and demand are

- (2)

- The optimal profit function for Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 is

The proof is the same as above.

From Proposition 4, we derive the following:

Corollary 4.

Service Provider 2’s optimal price is directly proportional to its advertising discount coefficient and the additional utility provided to consumers through intercity services, while it is inversely proportional to Service Provider 1’s advertising discount coefficient. Both Service Providers 1 and 2’s optimal prices are inversely proportional to the government subsidy ratio m.

This indicates that when Service Provider 1 also engages in advertising, Service Provider 2 should adjust its optimal pricing downward to account for competitive pressures while emphasizing the additional utility it delivers to consumers. Government subsidies to Service Provider 2 for intercity services will lower its optimal price, thereby attracting more consumers.

4.2. External Disturbance (GX)

Due to the complex operational environment of air taxis, they are susceptible to uncontrollable external factors such as extreme weather, sudden policy adjustments, and fuel price fluctuations. These factors directly impact consumer travel preferences or service providers’ operational costs. In 2023, Shenzhen suspended all low-altitude transportation for three days due to Typhoon Sura, resulting in daily losses exceeding CNY one million for service providers. Without accounting for such disturbances, the model would overestimate market stability. This paper defines disturbance factors as a random variable M, which follows a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance ( [45,46]. Since this component will be expanded across the four base models, the following section details only the calculation process for the most complex fourth model, GTX (considering external disturbance in GT mode). The optimal results for the NOX (considering external disturbance in NO mode), NTX (considering external disturbance in NT mode), and GOX (considering external disturbance in GO mode) models are presented directly.

The optimal solutions under four modes are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Optimal solutions for four modes under external disturbances.

5. Comparative Analysis

By solving the four non-perturbation modes above, Table 4 summarizes the optimal equilibrium strategies for each mode, yielding the following conclusions:

Table 4.

Optimal solutions for four models.

Lemma 1.

The optimal pricing prioritization for Service Provider 1, , is

Lemma 2.

The optimal pricing prioritization for Service Provider 2 is

.

Lemma 3.

The demand prioritization for Service Provider 1,

, is

Lemma 4.

The demand prioritization for Service Provider 2,

, is

It can be seen from this that for Service Provider 1, launching advertising campaigns will increase its optimal price, and its market demand will also be higher than when no advertising is conducted. When Service Provider 2 offers intercity services and the additional price (P2s) of such services is below a certain threshold, both its optimal price and market demand will be enhanced.

For Service Provider 2, the launch of advertising campaigns by Service Provider 1 will instead lead to a decrease in its (Service Provider 2’s) optimal price, and its market demand will also be eroded by Service Provider 1. If Service Provider 1 also conducts advertising campaigns, Service Provider 2 can further expand its market demand by offering intercity services, but it is necessary to ensure that the additional price of its intercity services is higher than a certain critical value.

6. Simulation

The above results are basically derived through mathematical model deduction. In this section, numerical examples are used to further compare and analyze the changes in profits under different decision-making modes of the four basic models and external disturbance models in a duopoly competition environment.

Based on the existing assumptions and parameter value ranges, the relevant parameters in this paper are assumed as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Parameter settings.

6.1. Profit Changes of Service Providers Under Different Modes

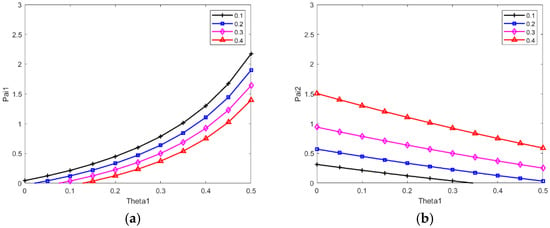

Under the NT mode, a simulation analysis was performed on the advertising discount coefficient () of Service Provider 2 with different values ( = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4). The changes in the profits of Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 as varies are shown in Figure 3a and Figure 3b, respectively.

Figure 3.

The impact of and on the profit of service providers: (a) Service Provider 1; (b) Service Provider 2.

As can be seen from Figure 3a, the competitive effect of θ2 on π1 is significant. Under the same value of θ1, when the advertising discount coefficient θ2 of Service Provider 2 increases, the profit π1 of Service Provider 1 shows a downward trend. Meanwhile, it can be observed that the marginal impact of θ1 is strengthened: regardless of the value of θ2, π1 increases as θ1 rises, indicating a positive correlation between the profit π1 of Service Provider 1 and its own advertising discount coefficient θ1. Furthermore, the slope of the curve is constantly increasing, which means that for each unit change in θ1, the increment brought to profit π1 grows—namely, the marginal impact of θ1 on profit π1 intensifies. This also suggests that in the current oligopolistic market context, when Service Provider 1 increases its own advertising discount coefficient θ1, it not only boosts its profit, but also the magnitude of this profit growth will become larger as θ1 further increases.

As can be seen from Figure 3b, the profit π2 of Service Provider 2 is negatively correlated with the advertising discount coefficient θ1 of Service Provider 1: as θ1 increases, π2 shows a downward trend. In other words, when Service Provider 1 increases its own advertising discount coefficient, the profit of Service Provider 2 will decrease. Moreover, when the advertising discount coefficient θ1 of Service Provider 1 is the same, the larger the advertising discount coefficient θ2 of Service Provider 2 itself, the higher its profit. This means that appropriately increasing its own advertising discount efforts is beneficial for Service Provider 2 to boost its profit and can alleviate the profit loss caused by Service Provider 1 increasing its advertising discount coefficient.

In an oligopolistic market, the advertising discount coefficient of a service provider directly affects its profit, and the advertising strategy of competitors exerts a significant moderating effect on its own profit. Service providers need to dynamically adjust their advertising discounts based on the competitive intensity of their counterparts to balance the advertising costs and the competition for market share, thereby achieving profit maximization.

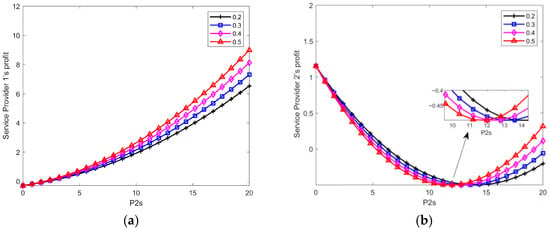

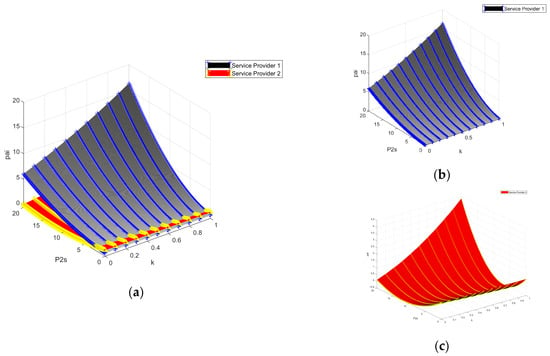

Under the GT mode, a simulation analysis was conducted on the additional cost coefficient (k) of intercity services provided by Service Provider 2 with different values (k = 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5). The changes in the profits of Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 as P2s varies are shown in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively.

Figure 4.

The impact of k and P2s on the profit of service providers: (a) Service Provider 1; (b) Service Provider 2.

As can be seen from Figure 4a, an increase in the intercity service price (P2s) of Service Provider 2 will drive the growth of Service Provider 1’s profit (π1), indicating that the price increase in Service Provider 2 has a positive effect on boosting Service Provider 1’s profit. The larger the additional cost coefficient (k) of Service Provider 2, the higher the profit of Service Provider 1 at the same P2s level. In other words, the higher the additional cost of Service Provider 2, the more conducive it is for Service Provider 1 to obtain higher profits. This may be because when Service Provider 2 faces higher costs, its pricing is restricted and its market competitiveness declines, leaving more profit space for Service Provider 1.

Figure 4b generally shows a U-shaped trend in Service Provider 2’s profit, where the profit first decreases and then increases. When P2s is at a relatively low level, Service Provider 2’s profit decreases as P2s rises; after P2s reaches a certain value, the profit increases with the growth of P2s. Moreover, at the same P2s level, the smaller the k value, the relatively higher the profit of Service Provider 2. This indicates that Service Provider 2’s profit does not change monotonically with P2s. In the stage where P2s is low, raising the price will reduce profits—this may be because the price increase leads to a decline in demand, and the reduction in revenue exceeds the savings in costs. When P2s exceeds a certain value, price increases can drive profit growth, which suggests that demand is less sensitive to price changes at this point. Such service demand is a type of high-end demand, which will not decrease due to price increases, and price hikes can increase revenue. Additionally, the smaller the additional cost coefficient (k), the higher the profit of Service Provider 2 at the same P2s level. This shows that the lower the additional cost of Service Provider 2, the stronger its profitability; cost advantages enable it to have greater advantages in market pricing and profit generation.

6.2. Impact of Different Modes on the Profit Difference Between Service Providers

Under the GO and NO modes, Service Provider 1 does not launch advertising campaigns, while Service Provider 2 conducts advertising. Specifically, Service Provider 2 does not offer intercity services under the NO mode but provides intercity services under the GO mode. Based on these two models, we analyze two types of profit differences: first, the profit difference of Service Provider 2 between offering and not offering intercity services and second, the profit difference between Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 under the two modes.

Under the GT and NT modes, both Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 launch advertising campaigns. Service Provider 2 does not offer intercity services under the NT mode, whereas it provides intercity services under the GT mode. Based on these two models, we examine two categories of profit differences: on one hand, the profit difference of Service Provider 2 when it offers intercity services versus when it does not, and on the other hand, the profit difference between Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 under the two modes.

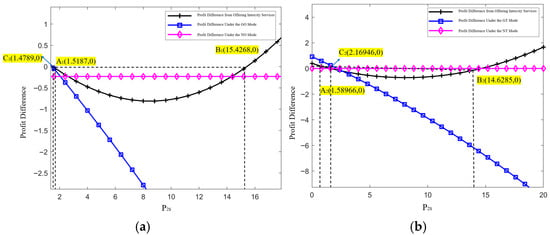

As can be seen from Figure 5a, the profit difference of Service Provider 2 between offering and not offering intercity services shows a trend of first decreasing and then increasing, and there is a segment where this profit difference is less than zero. This indicates that there exists a P2s range in which Service Provider 2 should not adopt the corresponding P2s pricing strategy when offering intercity services. Specifically, P2s values within the range (1.5187, 15.4268) will prevent Service Provider 2 from gaining higher profits even when it offers intercity services; instead, such P2s values will increase its input costs. Under the NO mode, since Service Provider 2 does not provide intercity services, its profit difference does not change with P2s. Under the GO mode, the profit difference between Service Provider 2 and Service Provider 1 shows a continuous downward trend, shifting from greater than zero to less than zero as P2s increases. Due to the complexity of the parameters, specific parameter values are substituted here, and the critical value of P2s at which the service providers’ profit difference is zero is calculated as 1.4789. This means that when P2s is less than 1.4789, Service Provider 2’s profit is higher than that of Service Provider 1, and offering intercity services can bring more revenue; however, when P2s is greater than 1.4789, Service Provider 2’s profit is lower than that of Service Provider 1, and offering intercity services fails to yield corresponding revenue returns.

Figure 5.

The impact of P2s on the profit difference between service providers under different models: (a) NO and GO modes; (b) NT and GT modes.

Observing Figure 5b, it is found that under the GT and NT modes, the variation trends of two types of profit differences—namely, the profit difference of Service Provider 2 between offering and not offering intercity services and the profit difference between the two service providers under the two modes—are highly similar to those under the GO and NO modes. This further confirms that when Service Provider 2 chooses to offer intercity services, it must reasonably set the additional price (P2s) for intercity services to maximize its own profits to the greatest extent.

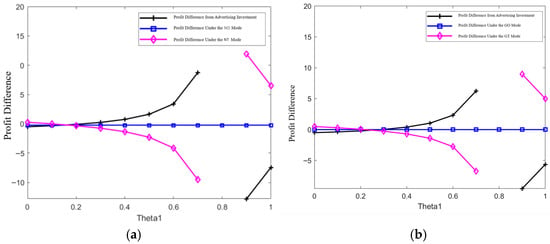

Under the NO and NT modes, neither Service Provider 1 nor Service Provider 2 offers intercity services. Specifically, under the NO mode, Service Provider 1 does not launch advertising campaigns while Service Provider 2 conducts advertising; under the NT mode, both service providers carry out advertising. At this point, the only difference between the two modes lies in whether Service Provider 1 conducts advertising. Under the GO and GT modes, Service Provider 2 offers intercity services. Specifically, under the GO mode, Service Provider 1 does not launch advertising campaigns but Service Provider 2 does; under the GT mode, both service providers implement advertising. Here, the distinction between the two modes also lies in whether Service Provider 1 conducts advertising. Therefore, both Figure 6a,b analyze and compare the changes in profit difference with the advertising discount coefficient (θ1) of Service Provider 1. It can be seen that the trends in the two figures are similar, with the only difference being that Service Provider 2 offers intercity services in one scenario (the GO and GT modes) but not in the other (the NO and NT modes).

Figure 6.

The impact of θ1 on the profit difference between service providers: (a) NO and NT modes; (b) GO and GT modes.

It can be observed that the profit difference of Service Provider 1 between conducting and not conducting advertising is greater than zero and shows an upward trend when θ1 is within a certain lower range; however, when θ1 becomes excessively large, this profit difference will be less than zero. This indicates that when Service Provider 1 conducts advertising, it should set its advertising discount coefficient (θ1) at an appropriate level—neither too high nor too low—to generate higher profits. Under the NO and GO modes, Service Provider 1 does not conduct advertising, so its profit difference is not affected by θ1.

6.3. Impact of Different Modes on Service Providers’ Profits

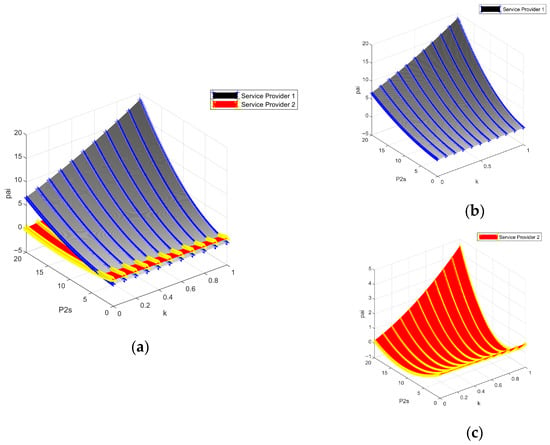

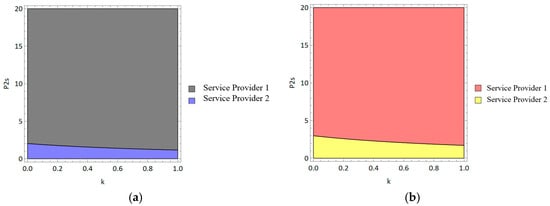

As can be seen from the figures below, Figure 7 and Figure 8 provide three-dimensional stereoscopic views, which help visualize the strategy response to parameter changes. Figure 9 shows a plan view for more intuitive understanding of the optimal strategy, when Service Provider 2 offers intercity services, the additional price (P2s) and additional cost coefficient (k) exert an impact on the profits of the two service providers. It is observed that under both modes, the profit of Service Provider 1 shows an upward trend as the additional price (P2s) increases, while the profit of Service Provider 2 exhibits a fluctuating trend of first decreasing and then increasing. However, the overall profit under the GT mode is higher than that under the GO mode. This indicates that when a service provider chooses to offer intercity services, it must comprehensively consider multiple influencing factors—such as the formulation of the additional price for intercity services, the control of relevant costs, and competitors’ service strategies—to ensure the maximization of its own interests.

Figure 7.

(a–c) Impact of k and P2s on service providers’ profits under the GO mode.

Figure 8.

(a–c) Impact of k and P2s on service providers’ profits under the GT mode.

Figure 9.

Optimal profit distribution under (a) the GO mode and (b) the GT mode.

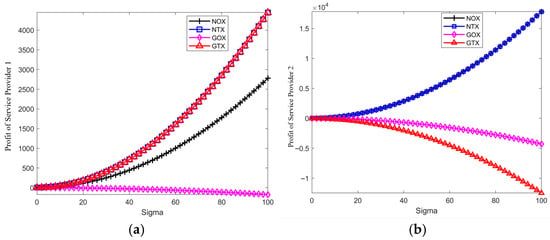

6.4. Impact of External Disturbances on Profits

As can be seen from Figure 10a, under the GOX mode, Service Provider 1’s profit remains close to zero at all times. This indicates that the external disturbance variance (σ) has almost no impact on Service Provider 1’s profit—under this mode, Service Provider 1 has extremely weak profitability and is barely affected by disturbances (it may also have little profit margin in the first place). Under the NOX and NTX modes, profit increases as σ rises, with the profit under NTX being consistently higher than that under NOX. This shows that when “neither party offers intercity services”, mutual advertising promotion (the NTX mode) is more conducive to Service Provider 1’s profitability than advertising solely by Service Provider 2 (the NOX mode). Furthermore, the greater the external disturbance, the more significant the profit growth of Service Provider 1 under both modes. This may be due to advertising promotion or changes in the market environment, which enable Service Provider 1 to expand its profits through disturbances when there is no competition from intercity services. Under the GTX mode, profit rises rapidly as σ increases and is much higher than that under other modes. This suggests that in the mode where “Service Provider 1 does not offer intercity services, while Service Provider 2 does, and both parties conduct advertising”, the greater the external disturbance variance (σ), the more remarkable the profit growth of Service Provider 1. This mode may be the most beneficial to Service Provider 1’s profitability due to factors such as the coordination between intercity services and advertising promotion, as well as demand adaptation under market disturbances—making disturbances a driver of profit growth.

Figure 10.

Impact of σ on service provider profit under the external disturbance mode: (a) Service Provider 1; (b) Service Provider 2.

As can be seen from Figure 10b, under the NOX and NTX modes, Service Provider 2’s profit increases with the rise in σ and the growth rate is significant. This indicates that the greater the external disturbance, the more conducive it is to Service Provider 2’s profitability. The combination of advertising promotion and market disturbances may have expanded profit channels and amplified profit margins. Under the GOX mode, Service Provider 2’s profit shows a slight negative fluctuation as σ increases, which suggests that external disturbances put pressure on its profit, yet the change in pressure is not significant. This may be attributed to the investment in intercity services or the characteristics of demand under market disturbances, resulting in difficulties in profitability and weak sensitivity to disturbances. Under the GTX mode, Service Provider 2’s profit declines rapidly with the increase in σ. This means that in the mode where “Service Provider 1 does not offer intercity services while Service Provider 2 does and both parties conduct advertising”, the greater the external disturbance, the more severe the profit loss of Service Provider 2. This could be due to the mismatch between intercity service costs, advertising investment, and market demand under disturbances, leading to a significant erosion of profits.

Based on this, a comparative analysis reveals the following insights: In terms of business model adaptability, modes without intercity services (NOX, NTX) are more adaptable to market environments with external disturbances, as they can leverage disturbances to expand profits. In contrast, modes with intercity services (GOX, GTX) suffer greater negative impacts from disturbances and face higher profit risks. In terms of the value of advertising strategies, when intercity services are not offered (NOX vs. NTX), mutual advertising promotion (NTX) can strengthen the positive effects of disturbances and boost profits. This indicates that advertising synergy can amplify market opportunities under stable business models. When intercity services are provided (GOX vs. GTX), although advertising brings traffic dividends to Service Provider 1, it fails to reverse the declining trend of Service Provider 2’s intercity business. In other words, the “rescue” effect of advertising on highly sensitive businesses is limited. In terms of market correlation effects: Even when business types differ (e.g., Service Provider 1 does not engage in intercity services while Service Provider 2 does), profits still change in a correlated manner under market disturbances (both decline under the GOX mode). This suggests that there are correlations in demand, resources, and other aspects among businesses within the industry, and strategy formulation must take into account the transmission effects of the overall market.

7. Conclusions and Future Research

7.1. Conclusions

Based on the Hotelling model, this study focuses on the duopoly market of air taxi service providers. Specifically, Service Provider S2, which consistently conducts advertising, decides whether to offer intercity services, whereas Service Provider S1, which does not offer intercity services, decides whether to launch advertising. Through model analysis, this study examines the profit changes of service providers after launching advertising or offering intercity services, the differences between the two providers after adding new services, and the effects of their different service strategies. In addition, through numerical examples, this study analyzes strategy selection regarding intercity services and advertising and identifies optimal pricing ranges for additional charges and feasible cost control ranges when providing intercity services. On the basis of this analysis, the following key conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- In a duopoly competitive market, one air taxi service provider can choose to offer intercity services. Doing so allows it to increase its optimal price and market share, thereby achieving higher profits.

- (2)

- If a service provider chooses to offer intercity services, the profits of both providers increase as the additional price for such services rises. However, the provider that offers intercity services must ensure that the additional price exceeds a critical threshold so that the profit from providing the services is higher than that from not providing them.

- (3)

- The advertising discount coefficient of one provider has a significant competitive effect on the profit of the other, and the competitor’s advertising strategy exerts a significant moderating effect on its own profit. If both providers launches advertising, the marginal effect of the advertising discount coefficient on each provider’s profit increases.

- (4)

- When a service provider chooses to conduct advertising, an optimal threshold exists for its advertising discount coefficient—it should be neither too high nor too low. At this threshold, the profit difference between conducting advertising and not conducting advertising is maximized.

- (5)

- In a disturbed environment, service providers should prioritize modes that do not involve intercity services. In particular, the mode with mutual advertising promotion (NTX mode) is more optimal under such conditions. If intercity services are offered, service providers must carefully assess disturbance risks or adopt flexible cost and operation strategies to offset negative effects.

From a management perspective, in the duopoly competitive landscape, air taxi service providers should build competitive advantages through differentiated strategic positioning. When offering intercity services, they must set the additional price reasonably and ensure it exceeds the critical threshold to achieve higher profits. In terms of advertising strategies, they should account for synergies or differences between their own and competitors’ approaches and identify the optimal threshold for the advertising discount coefficient. In the face of disturbances, service providers should prioritize modes that exclude intercity services and include mutual advertising. If intercity services are adopted, service providers must establish a sound risk assessment system and flexible response strategies. They should also recognize that market competition is a dynamic game process. Service providers must integrate short-term decisions with long-term planning, continuously monitor competitors’ strategy adjustments, and optimize their own strategies in a timely manner to maintain a competitive advantage and achieve profit maximization.

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study assumes that Service Provider S1 does not offer intercity services, resulting in a relatively static model. In real-world duopoly competition, Service Provider S1 may dynamically adjust its decisions in response to market feedback. This static assumption deviates from actual dynamic competitive environments and fails to fully capture the interactive evolution of business strategies. For instance, it does not account for scenarios where Service Provider S1 alters its strategy upon recognizing the potential of the intercity service market. Second, the study does not differentiate between user preferences for intercity services and advertising (e.g., differing demands between business and individual users). Instead, it assumes a homogeneous market demand. In reality, distinct decision-making logics across user segments affect the effectiveness of service strategies. The author will conduct more in-depth research on this subject in subsequent studies.

Author Contributions

H.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology. J.Z.: Formal analysis, conceptualization, validation, writing—original draft, project administration, formal analysis, validation, writing—review and editing. Z.W.: Supervision, resources, writing—review and editing. X.Y.: Validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project “Research on Online Advertising Placement Strategies Under Uncertain Environmental Disturbances” (72401249); Yangzhou University School of Business 2024 Graduate Practical Innovation Project “Research on Financing Solutions for Jinhai High-Tech from a Supply Chain Finance Perspective” (SXYJSCX202428); Yangzhou University School of Business 2025 Graduate Practical Innovation Project “Research on Financing Solutions for Agricultural Enterprises from a Supply Chain Perspective: A Case Study of Shandong Baolaililai” (SXYSJCX202540); and Jiangsu Province Graduate Research and Practice Innovation Plan Project (SJCX25_2241).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Proof of the Optimal Solution of the GTX Model.

On the basis of the model where Service Provider 2 offers intercity services and both Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 engage in advertising, the impact of external disturbance factors is taken into account. At this point,

The market demand for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 is as follows:

Assume that the demand of Service Provider 2 conforms to the linear inverse demand function .

Then the demand of Service Provider 1 is .

At this point, the market demand for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 is as follows:

The profit functions for Service Provider S1 and Service Provider S2 are, respectively,

Based on the optimality conditions and , we obtain the following:

The equilibrium results under the GTX mode are provided:

- (1)

- The optimal price and demand are

- (2)

- The optimal profit function for Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2 is

- (3)

- Let . By rearranging the profit functions of Service Provider 1 and Service Provider 2, we obtain

□

Appendix A.2

Proof of Corollary 1.

- (1)

- Since , ; thus, .

Since > 0, < 0; then, < 0; thus, .

- (2)

- Since ; ;

Since < 0, .

- (3)

- Since , .

- (4)

- When neither Service Provider 1 nor Service Provider 2 offers services or conducts advertising, within the Hotelling linear model, .

When , > 0; thus, .

- (5)

- When neither Service Provider 1 nor Service Provider 2 conducts advertising, within the Hotelling linear model, .

When < , < 0; thus, . When > , > 0; thus, . □

Proof of Corollary 2.

- (1)

- Since , , ; thus, > 0, > 0, and . Since , < 0; thus, < 0 and .Since , ; thus, < 0; therefore, , , and .

- (2)

- , since ; thus, > 0, and therefore . , since ; thus, > 0 and therefore .

□

Proof of Corollary 3.

□

Proof of Corollary 4.

□

Appendix A.3

Proof of Lemma 1.

when

; thus, .

When

□

Proof of Lemma 2.

, < 0; thus, .

< 0; thus, . □

Proof of Lemma 3.

; thus, .

When

> 0, > 0; that is, ; when

< 0, < 0; that is, . □

Proof of Lemma 4.

; thus, .

When

When

□

References

- Available online: https://www.planning.org.cn/news/view?id=16083 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Available online: https://hznews.hangzhou.com.cn/chengshi/content/2023-01/05/content_8440758_0.htm (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Available online: https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20250717A041PX00 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Wang, M.K.; Diepolder, J.; Zhang, S.G.; Söpper, M.; Holzapfel, F. Trajectory optimization-based maneuverability assessment of eVTOL aircraft. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, J.; Ai, Y. The impact of government green subsidies on stock price crash risk. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 107573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dwivedi, R.; Mariani, M.M.; Islam, T. Investigating the effect of advertising irritation on digital advertising effectiveness: A moderated mediation model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issouani, E.M.; Bertail, P.; Gautherat, E. Exponential bounds for regularized Hotelling’s T2 statistic in high dimension. J. Multivar. Anal. 2024, 203, 105342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Climent, J.; Garcia-Perez, L.; Losada, J.C.; Alonso-Sanz, R. Simulation of the Hotelling-Smithies game: Hotelling was not so wrong. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 112, 106513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atewamba, C.; Nkuiya, B. Testing the Assumptions and Predictions of the Hotelling Model. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 66, 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, R.B.; Carballo-Cruz, F. A general framework for retailer competition under elastic demand and quantity-dependent transport costs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 87, 104358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, R.B.; Shuai, J. Personalized pricing with a price sensitive demand. Econ. Lett. 2022, 213, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.K. Unmanned aerial vehicles based low-altitude economy with lifecycle techno-economic-environmental analysis for sustainable and smart cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 499, 145050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.J.; Guo, Z.L.; Yan, J.Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Advancing low-carbon smart cities: Leveraging UAVs-enabled low-altitude economy principles and innovations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 222, 115942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.E.; Zeng, Q.H.; Shao, C.; Zhuo, P.; Li, B.W.; Sun, K.C. UAV Localization Method with Keypoints on the Edges of Semantic Objects for Low-Altitude Economy. Drones 2025, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. eVTOL Dispatch Cost Optimization Under Time-Varying Low-Altitude Delivery Demand. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ran, D. China’s low-altitude economy needs to grow with more caution. Nature 2025, 638, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.L.; Wang, X.X.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Lv, C.; Yu, H.; Ma, J.; Wang, F.Y. Social Radars for Social Vision of Intelligent Vehicles: A New Direction for Vehicle Research and Development. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 4244–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Q.; Fang, S.F.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Low-altitude intelligent transportation: System architecture, infrastructure, and key technologies. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; Zheng, S.; Shang, W.-L.; Wang, K. Bike-sharing duopoly competition under government regulation. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Jin, S.; Jiang, H. Complex dynamics of dual oligopoly demand uncertainty under carbon emission trading mechanism. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 179, 114435. [Google Scholar]

- Fanti, L.; Buccella, D. Tax evasion and competition in a differentiated duopoly. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2021, 48, 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Xie, X.R.; Sun, C.Q.; Lin, L.; Liu, J.L. Optimal trade policy and welfare in a differentiated duopoly. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 3019–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Lian, Z.; Lien, J.W.; Zheng, J. Serial and parallel duopoly competition in multi-segment transportation routes. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 133, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, L.; Sodini, M. Price competition in a nonlinear differentiated duopoly. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2017, 104, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboubi, S. Incentive mechanisms for price and advertising coordination in dynamic marketing channels. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 2281–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, S.; Taboubi, S.; Zaccour, G. Cooperative advertising in a marketing channel. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2001, 110, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. Spillovers from Mass Advertising: An Identification Strategy. Mark. Sci. 2020, 39, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, G.; Buscher, U. Cooperative advertising models in supply chain management: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 234, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.B.; Liu, Y.H.; Wang, P.F. Financing an online newsvendor with considering the impact of advertising strategy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7205–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, M.K.; Makui, A. Optimal advertising decisions for promoting retail and online channels in a dynamic framework. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2014, 21, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, G.G.; Wei, T.; Hu, S. Customer Perceived Value- and Risk-Aware Multiserver Configuration for Profit Maximization. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2020, 31, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Stability in competition. Econ. J. 1929, 39, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Su, X. Omnichannel retail operations with buy online and pickup in store. Manag. Sci. 2016, 63, 2478–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Ni, D.B.; Li, K.W. Competition between manufacturers and sharing economy platforms: An owner base and sharing utility perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 234, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Wu, D.J. Platform competition under network effects: Piggybacking and optimal subsidization. Inf. Syst. Res. 2021, 32, 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.G., Jr.; Parker, G.; Tan, B. Platform performance investment in the presence of network externalities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Narasimhan, C.; Zhang, Z.J. Consumer heterogeneity and competitive price-matching guarantees. Mark. Sci. 2001, 20, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J. Product and service innovation with customer recognition. Decis. Sci. 2024, 55, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Avgerinos, E.; Feng, G.; Chu, F. Dual-channel competition: The role of quality improvement and price-matching. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 3705–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Feng, H.; Feng, N. Which is better for competing firms with quality increasing: Behavior-based price discrimination or uniform pricing? Omega 2023, 118, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, A. Impact of government subsidies on total factor productivity of energy storage enterprises under dual-carbon targets. Energy Policy 2024, 187, 114046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.J.; Srinivasan, K. Pricing and persuasive advertising in a differentiated market. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, K. The economic analysis of advertising. In Handbook of Industrial Organization; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 1701–1844. [Google Scholar]

- De Giovanni, P. Quality improvement vs. advertising support: Which strategy works better for a manufacturer? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 208, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, D.; Kalić, M. Modeling the selection of airline net-work structure in a competitive environment. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 66, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barla, P.; Constantatos, C. Airline network structure under demand uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2000, 36, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).