Mapping the Dynamics Behind Breakthrough Innovations in China’s Energy Sector: The Evolution of Research Foci and Collaborative Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolutionary Trajectory of Innovations in the Energy Field

2.2. Role of Collaboration in Innovation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Research Focus Trajectory Analysis

3.3. CN Analysis

4. Results

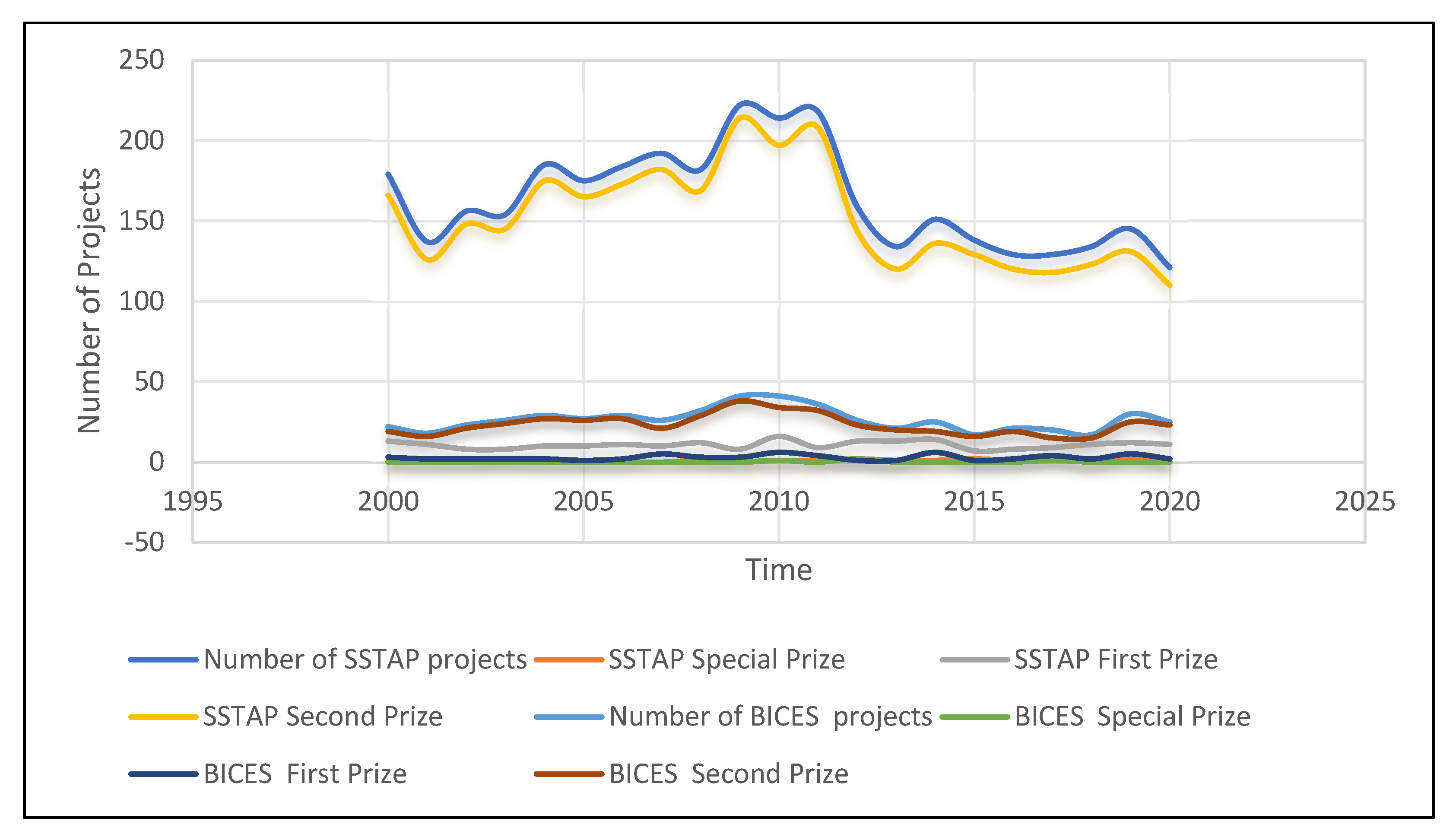

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

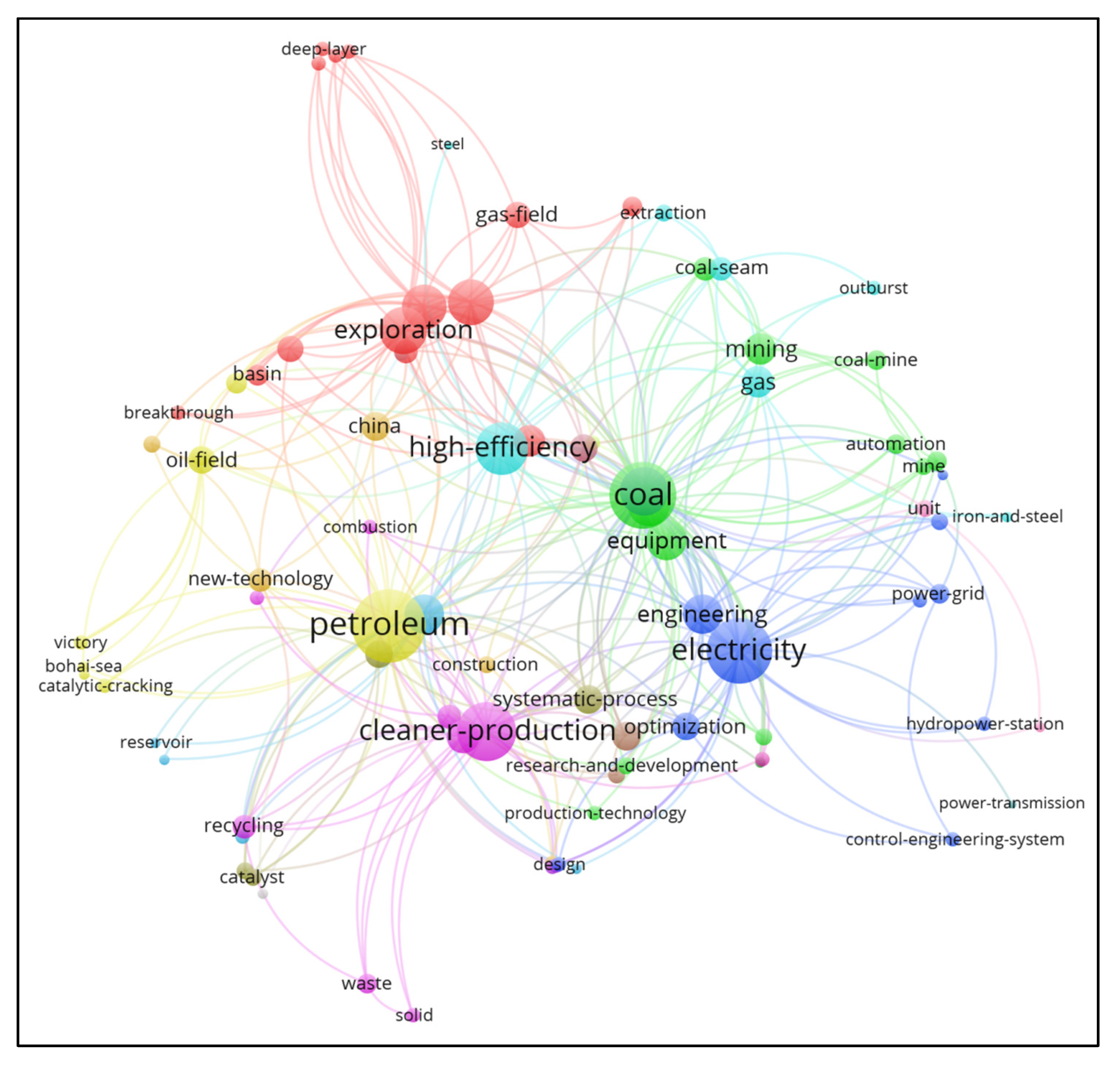

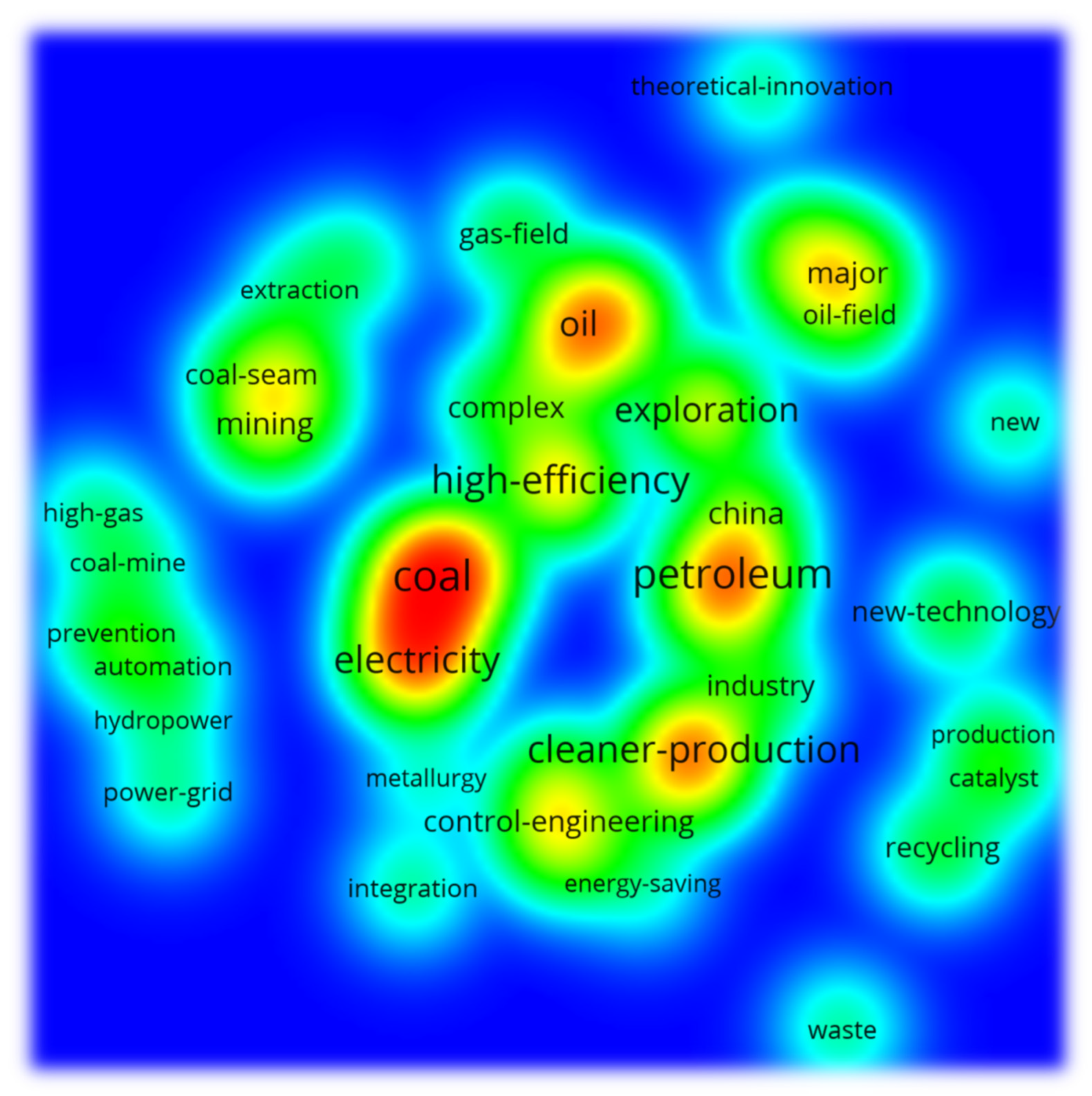

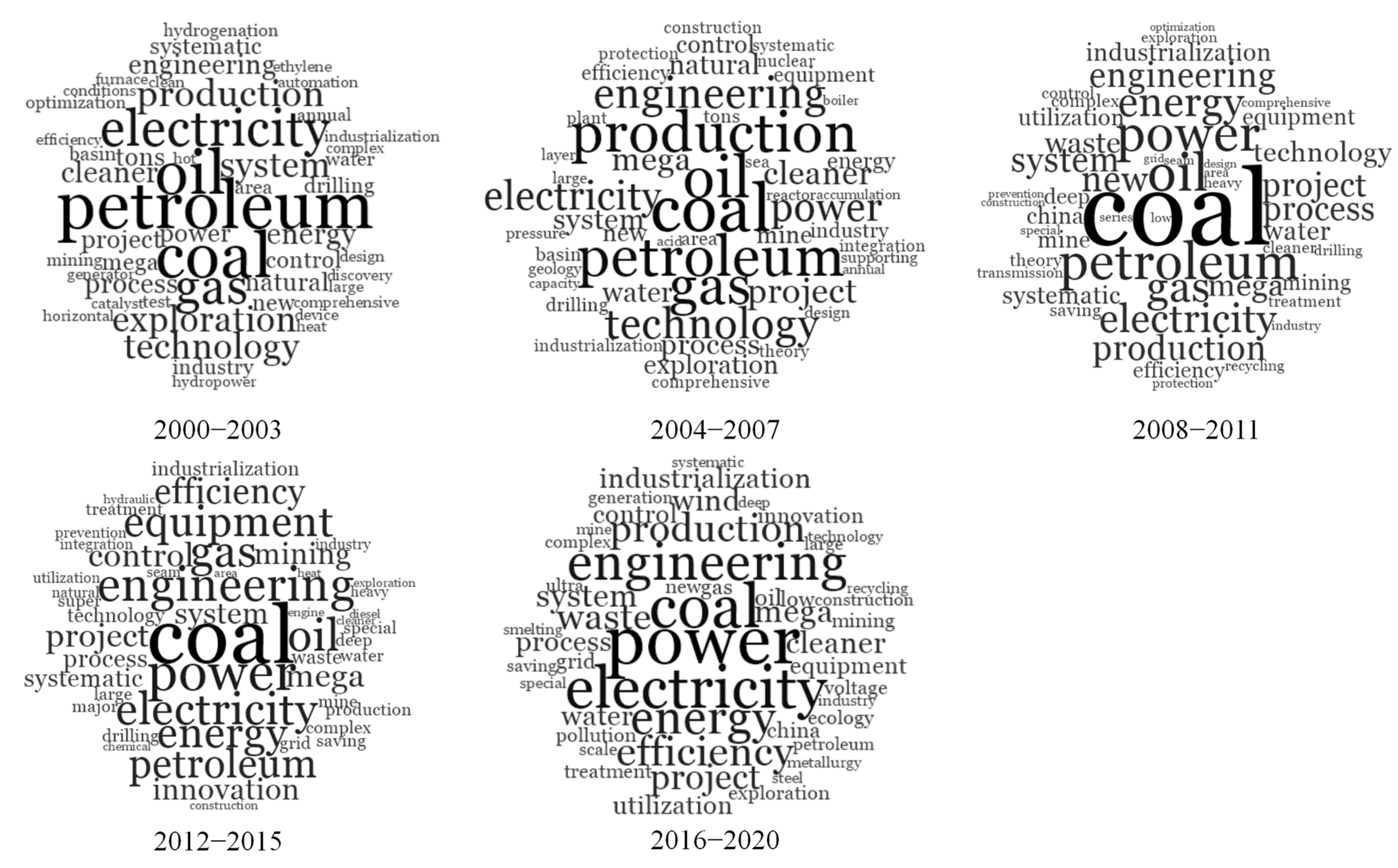

4.2. Evolution of Research Foci in BICES

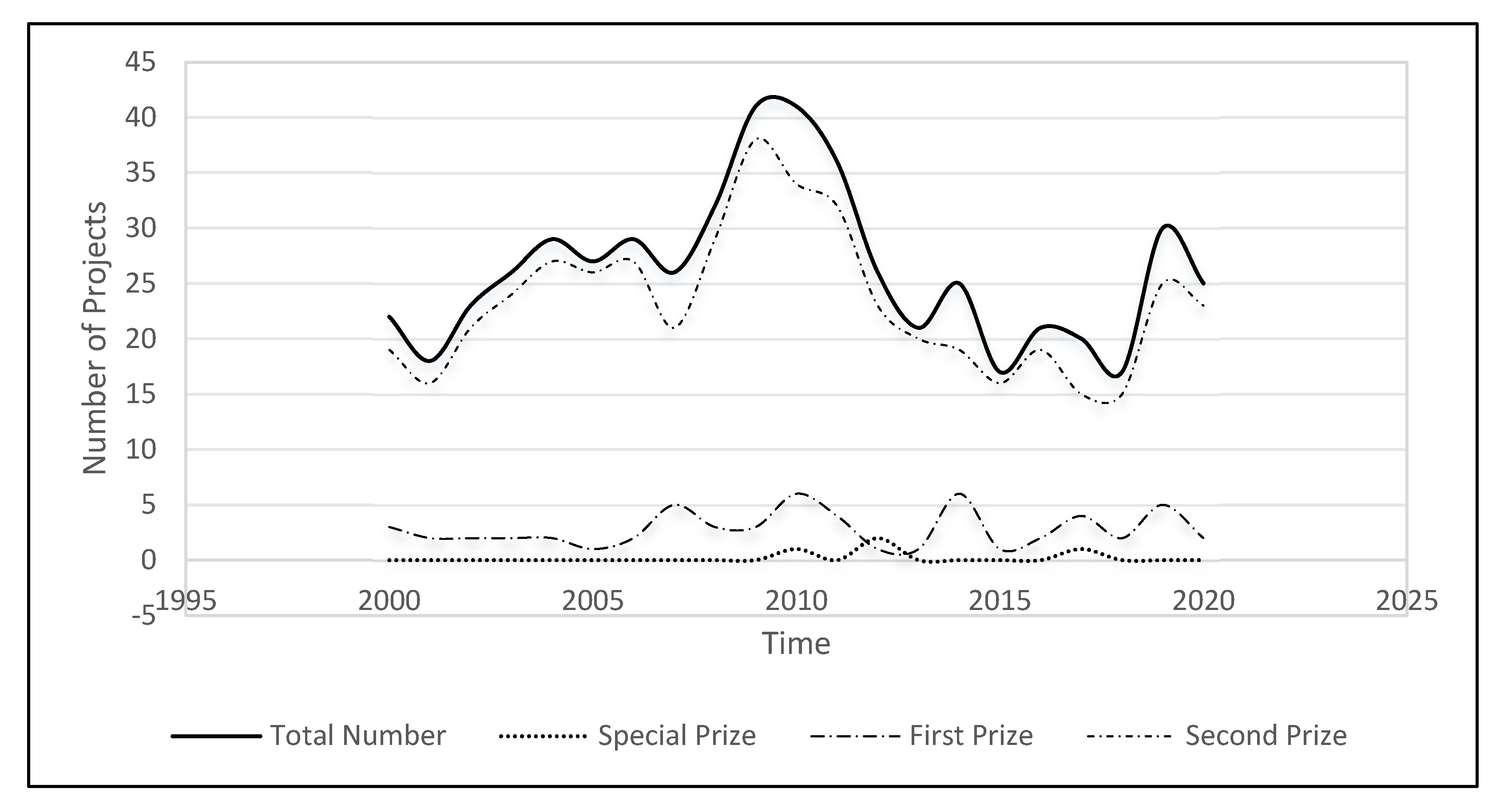

4.2.1. General Characteristics of Research Foci in BICES

4.2.2. Evolving Research Foci of BICES

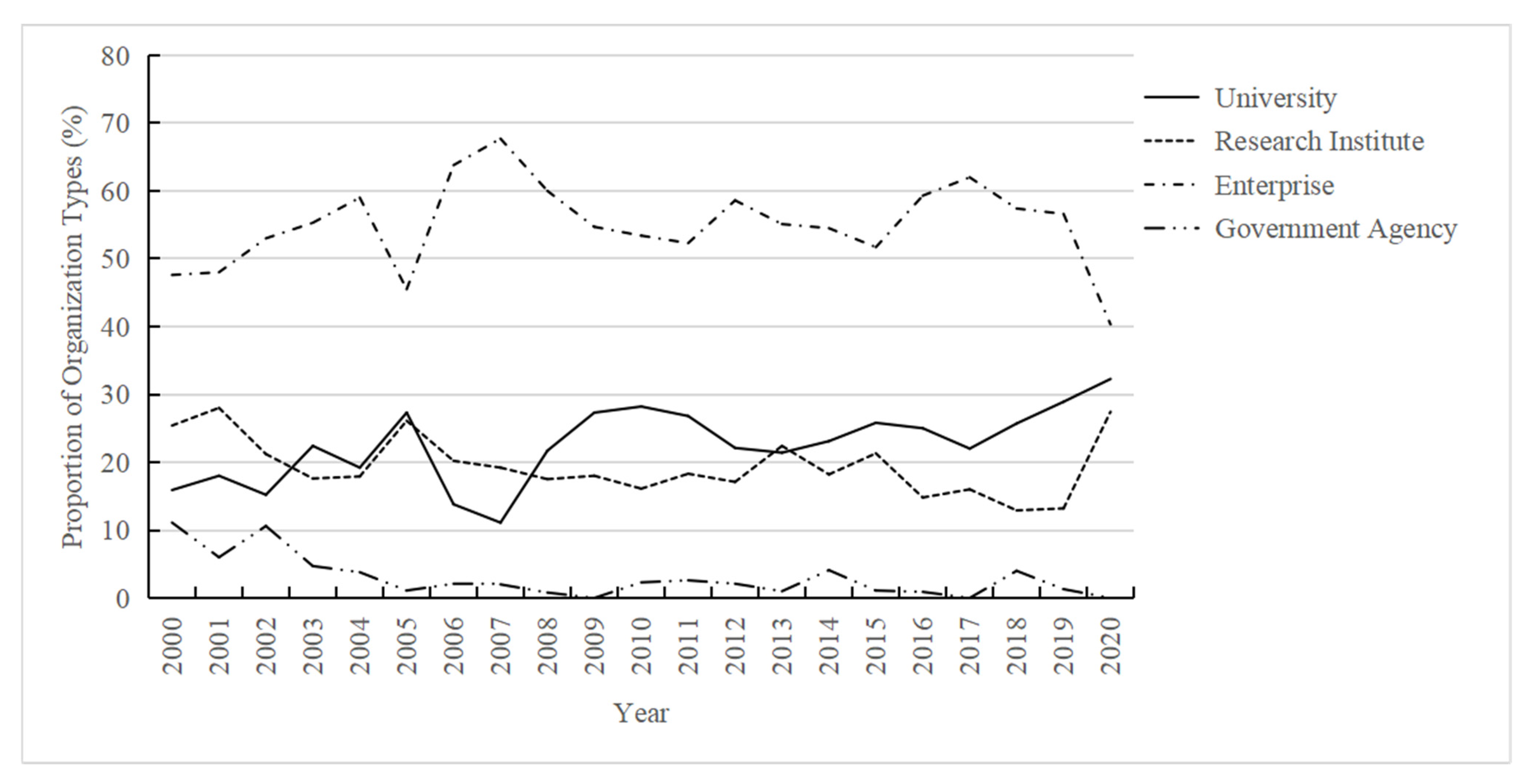

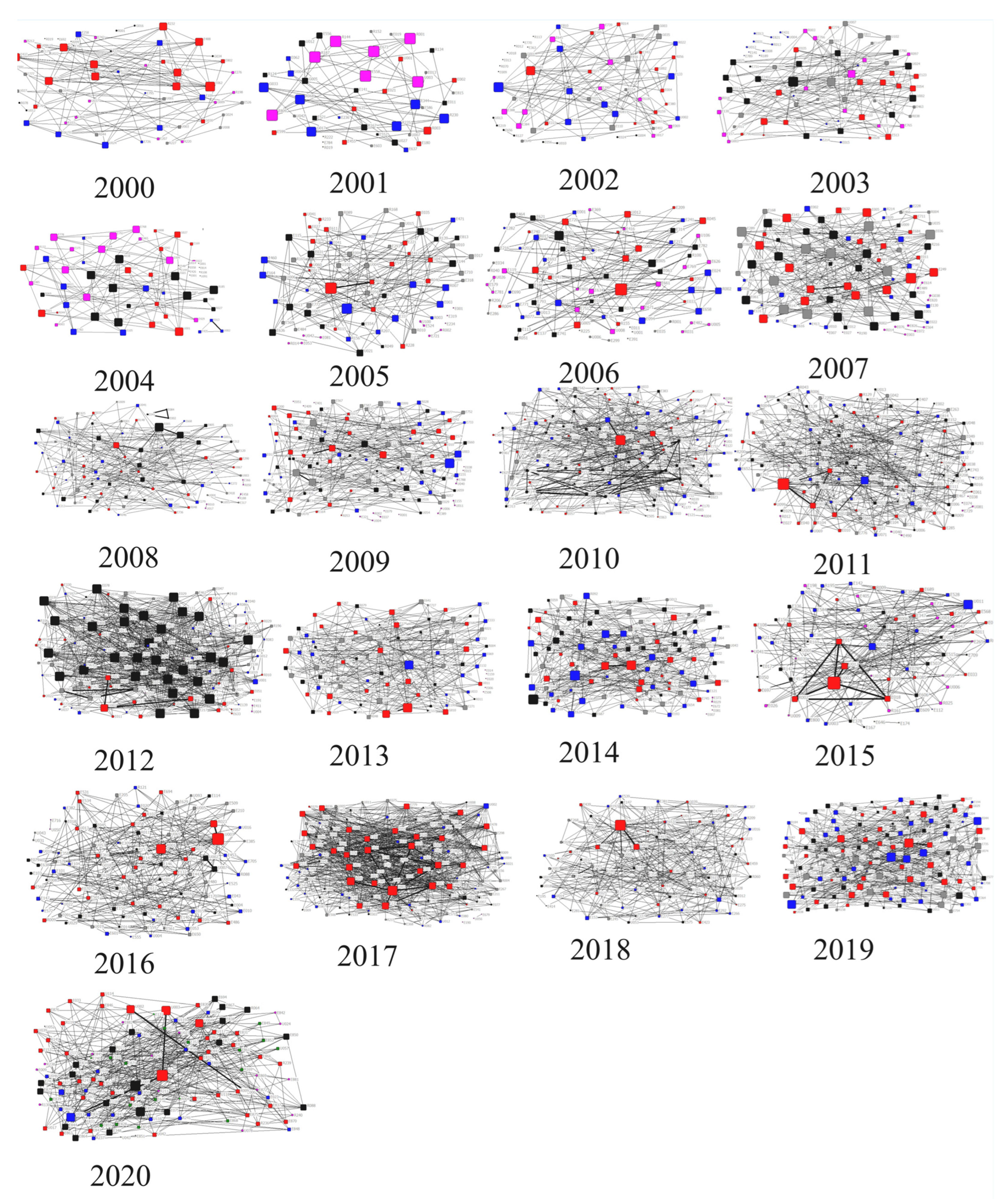

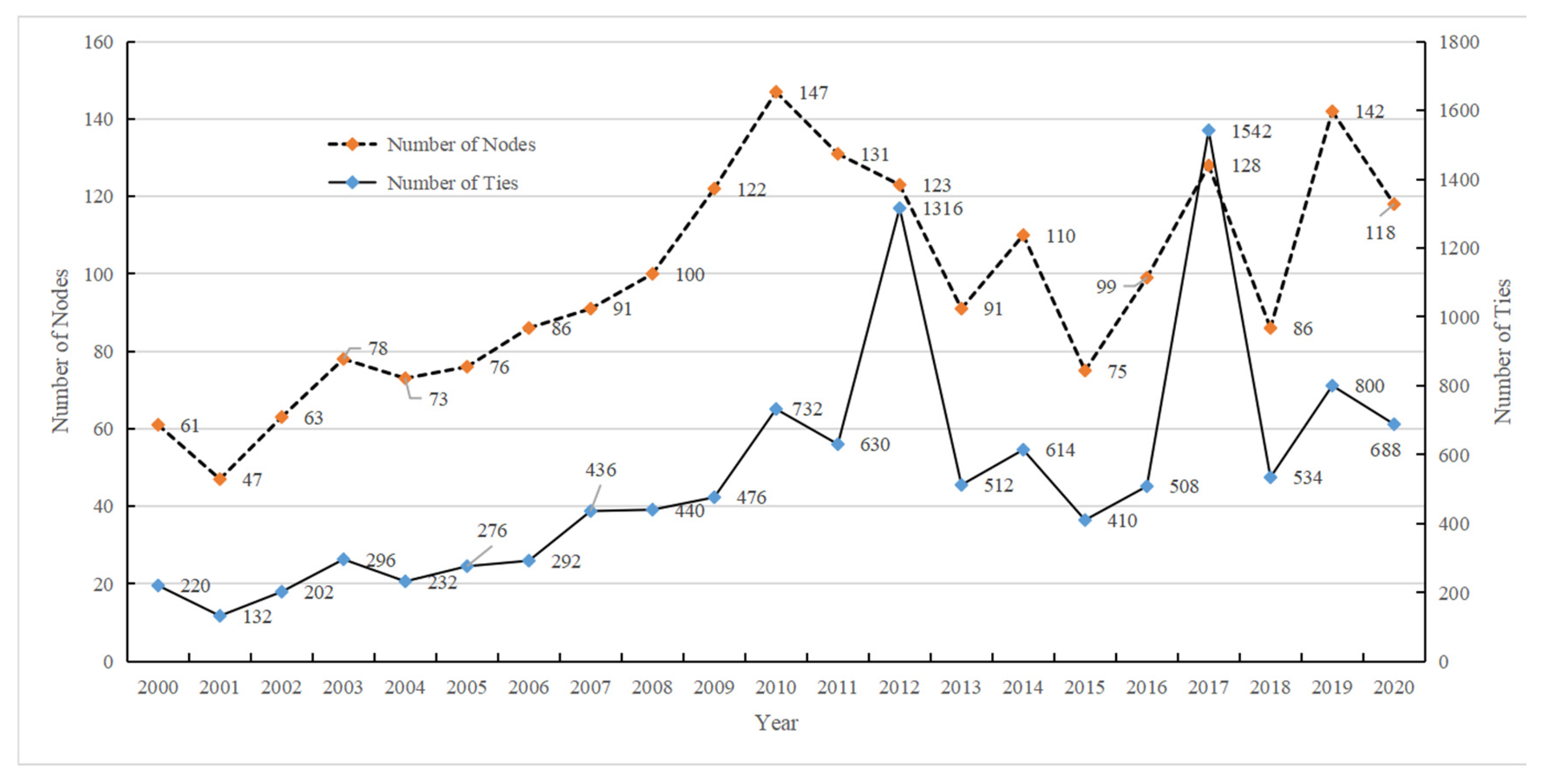

4.3. CN Evolution of BICES Projects

4.3.1. Characteristics of Organizations Participating in BICES Projects

4.3.2. Visualization of CNs from 2000 to 2020

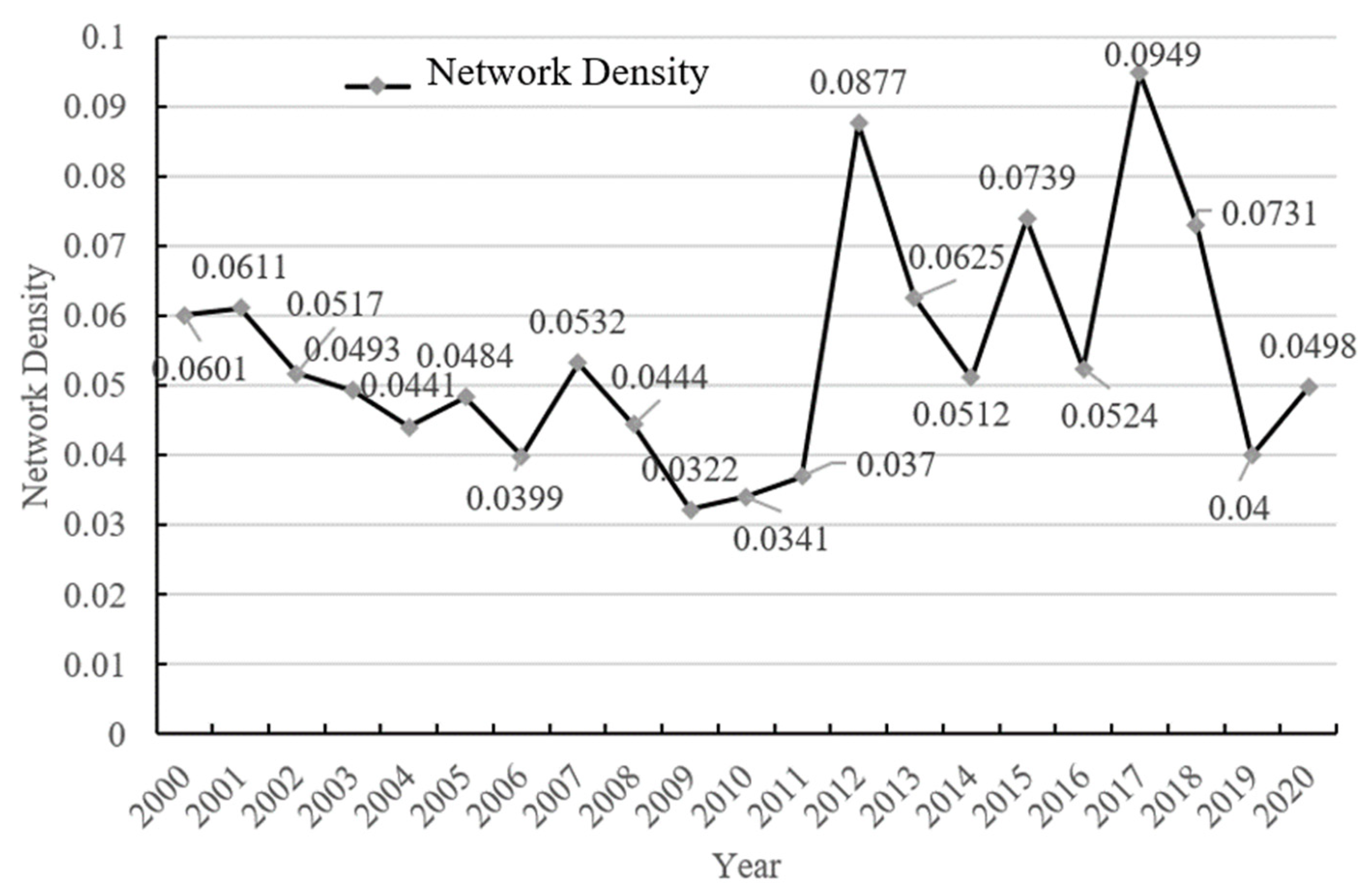

4.3.3. Network Characteristics and Key Nodes of CNs

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications of Research Focus Evolution

5.2. Implications of CNs for BICES

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSTAP | State Science and Technology Advancement Prize |

| BICES | Breakthrough innovations in China’s energy sector |

| LLM | Large language model |

| SNA | Social network analysis |

| CN | Collaboration network |

| SOE | State-owned enterprise |

| PE | Private enterprises |

References

- Grubler, A.; Wilson, C. Energy Technology Innovation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- da Paz, L.R.L.; da Silva, N.F.; Rosa, L.P. The paradigm of sustainability in the Brazilian energy sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 1558–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolo’, G. Exploring sustainable development goals reporting practices: From symbolic to substantive approaches—Evidence from the energy sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1799–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, A.D.; Holdren, J.P. Assessing the global energy innovation system: Some key issues. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubler, A.; Aguayo, F.; Gallagher, K.; Hekkert, M.P.; Jiang, K.; Mytelka, L.; Neij, L.; Nemet, G.; Wilson, C. Policies for the Energy Technology Innovation System (ETIS); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W.; Zhao, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Q. Energy technological progress, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions: Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadon, L.D.; Holdren, J.P. Policy for Energy-Technology Innovation. In Acting in Time on Energy Policy; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 89–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bañales-López, S.; Norberg-Bohm, V. Public policy for energy technology innovation: A historical analysis of fluidized bed combustion development in the USA. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Huang, P.; Wang, X. Innovation performance and influencing factors of low-carbon technological innovation under the global value chain: A case of Chinese manufacturing industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 111, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Min, J. Dynamic trends and regional differences of economic effects of ultra-high-voltage transmission projects. Energy Econ. 2024, 138, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capponi, G.; Martinelli, A.; Nuvolari, A. Breakthrough innovations and where to find them. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Vanden, K.; Jefferson, G.H.; Jingkui, M.; Jianyi, X. Technology development and energy productivity in China. Energy Econ. 2006, 28, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Energy, Environment and Economic Transformation in China; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Gallagher, K.S.; Myslikova, Z.; Narassimhan, E.; Bhandary, R.R.; Huang, P. From fossil to low carbon: The evolution of global public energy innovation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G. Energy levels and co-evolution of product innovation in supply chain clusters. In Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Business Technology and Strategy, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29–30 September 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Dai, J.; Wei, H.; Lu, Q. Understanding technological innovation and evolution of energy storage in China: Spatial differentiation of innovations in lithium-ion battery industry. J. Energy Storage 2023, 66, 107307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, S. Patterns of technological innovation and evolution in the energy sector: A patent-based approach. Energy Policy 2013, 59, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, G.C. Sustaining breakthrough innovation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2009, 52, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.J. Controlled Nuclear Fusion: Status and Outlook: Besides plasma confinement, technological and environmental factors are essential. Science 1971, 172, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.; Yang, X.; Xu, J. Energy price and cost induced innovation: Evidence from China. Energy 2020, 192, 116586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Rodan, S.; Fruin, M.; Xu, X. Knowledge networks, collaboration networks, and exploratory innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 484–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Zuo, J.; Hu, W.; Nie, Q.; Lei, H. Who drives green innovations? Characteristics and policy implications for green building collaborative innovation networks in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiyan, D.; Ahmed, K.; Nanere, M. Life cycle, competitive strategy, continuous innovation and firm performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.S. Limits to leapfrogging in energy technologies? Evidence from the Chinese automobile industry. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Bohm, V. The Role of Government in Energy Technology Innovation: Insights for Government Policy in the Energy Sector; Energy Technology Innovation Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; Working Paper; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Anadon, L.; Bunn, M.G.; Chan, M.; Jones, C.A.; Kempener, R.; Chan, G.A.; Lee, A.; Logar, N.J.; Narayanamurti, V. (Eds.) Transforming U.S. Energy Innovation; Energy Technology Innovation Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Plakitkin, Y.A.; Tick, A.; Plakitkina, L.S.; Dyachenko, K.I. Global Energy Trajectories: Innovation-Driven Pathways to Future Development. Energies 2025, 18, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alvarado, M.; Rodríguez-Salazar, A.; Torres-Huerta, A.; Gutiérrez-Galicia, F.; Hernández-Alvarado, L.; Domínguez-Crespo, M. The evolution of biocomposites in renewable energy: An integrated review of research trends, patent activity, and technological innovation (2004–2024). Fuel 2026, 404, 136225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Q.; Rauta, T.; Keskikuru, J.; Haverinen, J.; Ruuskanen, P. Innovations in energy harvesting: A survey of low-power technologies and their potential. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 671–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awamleh, H.K.; Omoush, M.M.; Ahmed, R.T.; Assaf, N.; Alqudah, M.Z.; Samara, H. Innovation in energy management: Mapping knowledge development and technological change. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Tomoda, Y. Competing incremental and breakthrough innovation in a model of product evolution. J. Econ. 2018, 123, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ren, F.; Ju, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Exploring the role of digital transformation and breakthrough innovation in enhanced performance of energy enterprises: Fresh evidence for achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhu, J. The role of renewable energy technological innovation on climate change: Empirical evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beise, M.; Stahl, H. Public research and industrial innovations in Germany. Res. Policy 1999, 28, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zhou, T.; Wang, C. New energy vehicle innovation network, innovation resources agglomeration externalities and energy efficiency: Navigating industry chain innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, Z.; Mao, J.; Ma, Y.; Liang, Z. Exploring the effect of city-level collaboration and knowledge networks on innovation: Evidence from energy conservation field. J. Informetr. 2021, 15, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Gerged, A.M.; Kuzey, C.; Karaman, A.S. Corporate innovation capacity, national innovation setting, and renewable energy use. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 205, 123459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badi, S.M.; Pryke, S.D. Assessing the quality of collaboration towards the achievement of Sustainable Energy Innovation in PFI school projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2015, 8, 408–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, D. A review of clean energy innovation and technology transfer in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Li, Y.K.; Taylor, J.E.; Zhong, J. Characteristics and Evolution of Innovative Collaboration Networks in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction: Study of National Prize-Winning Projects in China. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloundou, T.; Manning, S.; Mishkin, P.; Rock, D. GPTs are GPTs: Labor market impact potential of LLMs. Science 2024, 384, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.; Everett, M.; Freeman, L.C. UCINET 6 for Windows Software for Social Network Analysis; Analytic Technologies, Inc.: Harvard, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman, S.; Lin, A. China’s Renewable Energy Law and its impact on renewable power in China: Progress, challenges and recommendations for improving implementation. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosens, J.; Kåberger, T.; Wang, Y. China’s next renewable energy revolution: Goals and mechanisms in the 13th Five Year Plan for energy. Energy Sci. Eng. 2017, 5, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, D.; Yang, S. Social Network Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Pandey, K.K.; Kumar, A.; Naz, F.; Luthra, S. Drivers, barriers and practices of net zero economy: An exploratory knowledge based supply chain multi-stakeholder perspective framework. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 16, 1059–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwen, F.; Huiru, Z.; Sen, G. An analysis on the low-carbon benefits of smart grid of China. Phys. Procedia 2012, 24, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Feng, X.; Jin, Z. Sustainable development of China’s smart energy industry based on artificial intelligence and low-carbon economy. Energy Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxon, T.J.; Gross, R.; Chase, A.; Howes, J.; Arnall, A.; Anderson, D. UK innovation systems for new and renewable energy technologies: Drivers, barriers and systems failures. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 2123–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobos, P.H.; Erickson, J.D.; Drennen, T.E. Technological learning and renewable energy costs: Implications for US renewable energy policy. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Organization Code | Frequency | Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | U002 | 63 | China University of Petroleum |

| 2 | U001 | 62 | China University of Mining and Technology |

| 3 | U003 | 36 | Tsinghua University |

| 4 | R001 | 22 | China Electric Power Research Institute |

| 5 | U004 | 20 | Zhejiang University |

| 6 | U005 | 19 | Tianjin University |

| 7 | R002 | 16 | Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration & Development |

| 8 | E001 | 14 | Daqing Oilfield of CNPC |

| 9 | U006 | 14 | Xi’an Jiaotong University |

| 10 | E002 | 13 | Sinopec Engineering Incorporation |

| 11 | U007 | 13 | China University of Geosciences |

| 12 | U012 | 13 | Southwest Petroleum University |

| 13 | R003 | 12 | Sinopec Research Institute of Petroleum Processing |

| 14 | R005 | 12 | China Electric Power Research Institute |

| 15 | U013 | 12 | North China Electric Power University |

| 16 | R004 | 10 | Sinopec Petroleum Exploration and Production Research Institute |

| 17 | U010 | 10 | East China University of Science and Technology |

| 18 | U008 | 10 | Shandong University of Science and Technology |

| 19 | U011 | 10 | Huazhong University of Science and Technology |

| 20 | U009 | 10 | University of Science and Technology Beijing |

| Rank | Ranked by Betweenness Centrality | Organization Name | Ranked by Degree Centrality | Organization Name | Ranked by Closeness Centrality | Organization Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | U017 | Chongqing University | U003 | Tsinghua University | U017 | Chongqing University |

| 2 | U002 | China University of Petroleum | R005 | China Electric Power Research Institute | U003 | Tsinghua University |

| 3 | U011 | Huazhong University of Science and Technology | U002 | China University of Petroleum | E135 | China Power Engineering Consulting Group Southwest Electric Power Design Institute Co., Ltd. |

| 4 | U003 | Tsinghua University | R001 | China Southern Power Grid CSG Electric Power Research Institute | U013 | North China Electric Power University |

| 5 | U001 | China University of Mining and Technology | E135 | China Power Engineering Consulting Group Southwest Electric Power Design Institute Co., Ltd. | U002 | China University of Petroleum |

| Rank | Degree Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | Closeness Centrality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | R | E | G | U | R | E | G | U | R | E | G | |

| Top 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Top 20 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 0 |

| Top 30 | 6 | 5 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 19 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, T.; Guan, J.; Luo, T. Mapping the Dynamics Behind Breakthrough Innovations in China’s Energy Sector: The Evolution of Research Foci and Collaborative Networks. Systems 2025, 13, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110996

Yu T, Guan J, Luo T. Mapping the Dynamics Behind Breakthrough Innovations in China’s Energy Sector: The Evolution of Research Foci and Collaborative Networks. Systems. 2025; 13(11):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110996

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Tao, Junfeng Guan, and Ting Luo. 2025. "Mapping the Dynamics Behind Breakthrough Innovations in China’s Energy Sector: The Evolution of Research Foci and Collaborative Networks" Systems 13, no. 11: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110996

APA StyleYu, T., Guan, J., & Luo, T. (2025). Mapping the Dynamics Behind Breakthrough Innovations in China’s Energy Sector: The Evolution of Research Foci and Collaborative Networks. Systems, 13(11), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110996