Digital Technology Integration in Risk Management of Human–Robot Collaboration Within Intelligent Construction—A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To analyze the current applications of digital technologies: identifying key technology types, use patterns, and effectiveness in HRC risk management.

- (2)

- To construct a digital technology system framework: mapping out the synergistic relationships among different technologies in HRC risk management.

- (3)

- To identify core challenges and future directions: including technical, managerial, and ethical issues, and to propose pathways for future development.

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Result

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis Result

3.2.1. Annual Publications and Journal Distribution

3.2.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence

3.3. Systematic Literature Review Result

3.3.1. Digital Technology and Integration

- (1)

- MMA Technology

- (2)

- AI Learning Technology

- (3)

- Digital Twins

- (4)

- Augmented Reality

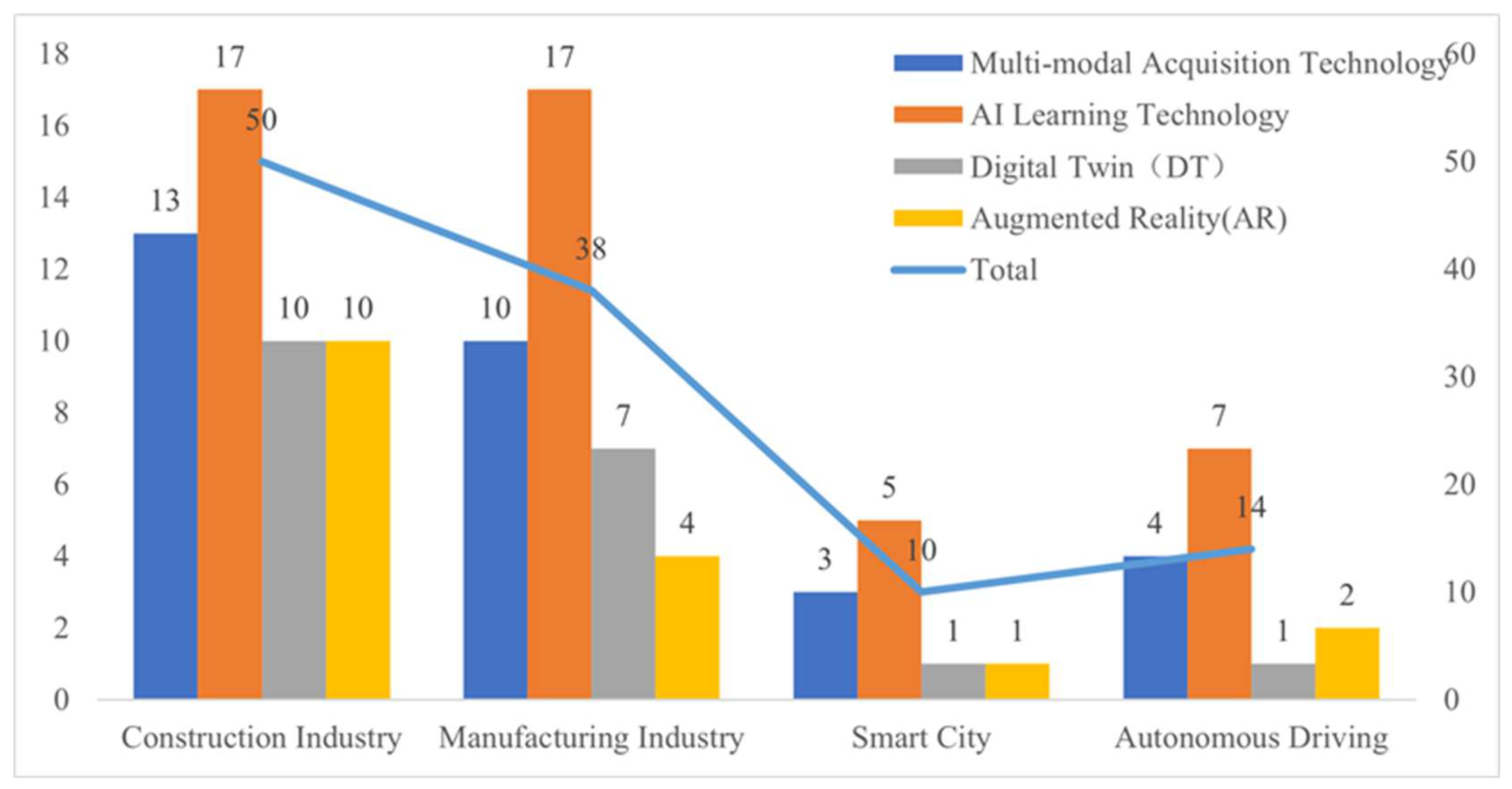

3.3.2. Application Domains

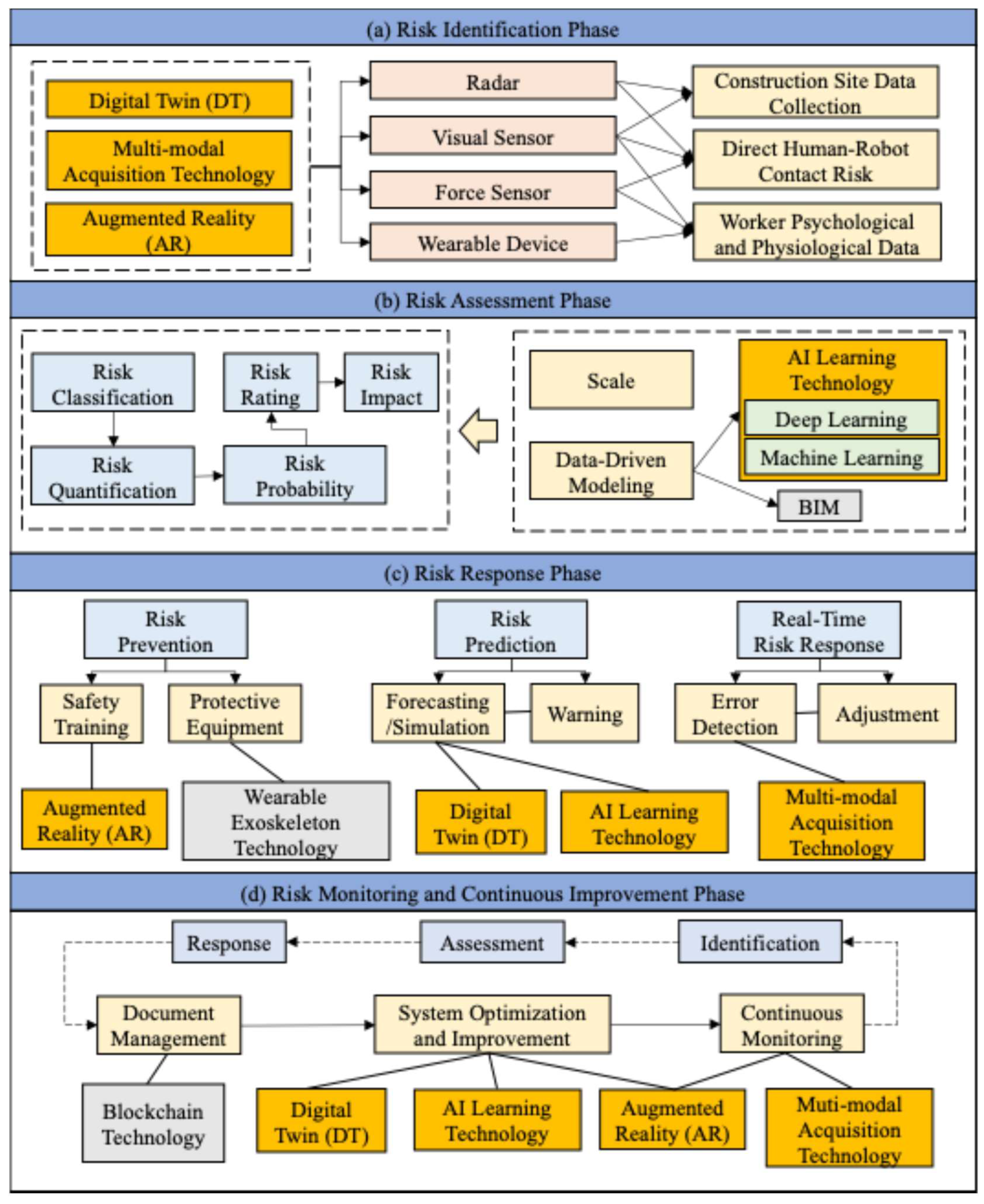

3.3.3. Risk Management and Processes

- (1)

- Risk Identification

- (2)

- Risk Assessment

- (3)

- Risk Response

- (4)

- Risk Monitoring and Continuous Improvement

4. Discussion and Future Research

4.1. Risk Identification

4.2. Risk Assessment

4.3. Risk Response

4.4. Risk Monitoring and Continuous Improvement

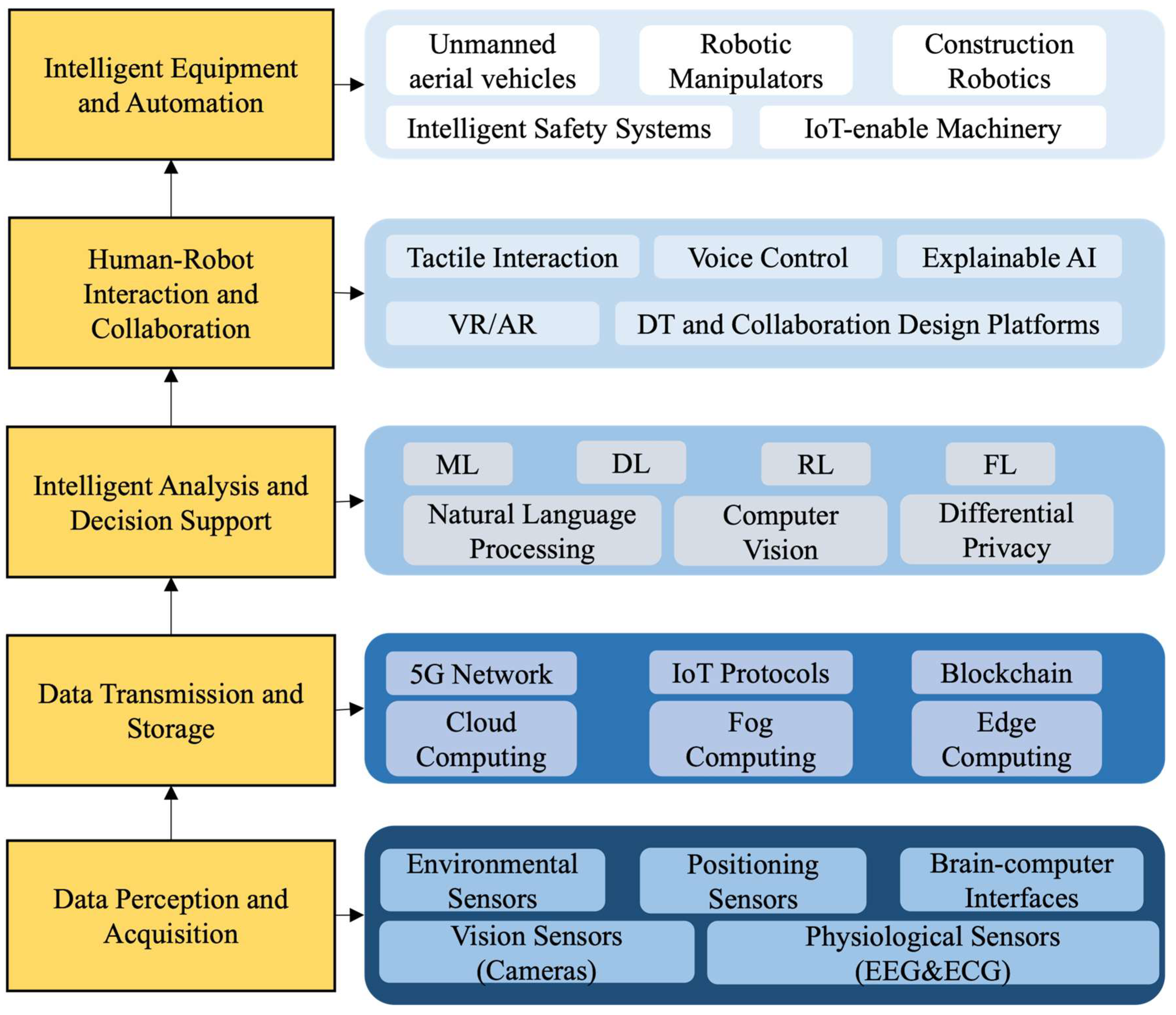

4.5. Towards an Integrated Digital Approach to HRC

- (1)

- Human-Centered Research: Trust and Acceptance: Enhance transparency through user-friendly interfaces and quantify human trust levels to improve worker acceptance and system reliability in HRC.

- (2)

- Robot-Level Research: Multi-Modal Data Fusion: Solve multi-source heterogeneous data fusion challenges by establishing unified standards and optimizing algorithms for improved efficiency and accuracy of intelligent analysis.

- (3)

- System-Level Research: Privacy, Ethics, and Risk Management: Address privacy concerns through encryption and anonymization while ensuring AI fairness and regulatory compliance in construction data management. Transform risk management from experience-dependent to data-driven through automated learning, real-time monitoring, and intelligent feedback mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sacks, R.; Lee, G.; Burdi, L.; Bolpagni, M. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Designers, Engineers, Contractors, and Facility Managers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Parlikad, A.K.; Woodall, P.; Don Ranasinghe, G.; Xie, X.; Liang, Z.; Konstantinou, E.; Heaton, J.; Schooling, J. Developing a Digital Twin at Building and City Levels: Case Study of West Cambridge Campus. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 19 December 2024. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cfoi.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Dufoe, D.; Trueblood, A.; Brooks, R.D.; Harris, W.; Stacks, C.D. Construction Worker Injuries, Overdoses, and Suicides. 1 April 2025. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/208935 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Teizer, J.; Allread, B.S.; Fullerton, C.E.; Hinze, J. Autonomous pro-active real-time construction worker and equipment operator proximity safety alert system. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Matthews, J.; Zhou, J. Is it just too good to be true? Unearthing the benefits of disruptive technology. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschert, S.; Rosen, R. Digital Twin—The Simulation Aspect. In Mechatronic Futures: Challenges and Solutions for Mechatronic Systems and Their Designers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yi, W.; Chi, H.-L.; Wang, X.; Chan, A.P. A critical review of virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) applications in construction safety. Autom. Constr. 2018, 86, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhou, T.; Du, J.; Li, N. Human motion prediction for intelligent construction: A review. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Habibnezhad, M.; Jebelli, H. Brain-computer interface for hands-free teleoperation of construction robots. Autom. Constr. 2021, 123, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teizer, J.; Cheng, T.; Fang, Y. Location tracking and data visualization technology to advance construction ironworkers’ education and training in safety and productivity. Autom. Constr. 2013, 35, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei Chadegani, A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ale Ebrahim, N. A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of science and scopus databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, M.; Al Mudawi, N.; Alabduallah, B.I.; Jalal, A.; Kim, W. A Multimodal IoT-Based Locomotion Classification System Using Features Engineering and Recursive Neural Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Du, P.; Lin, C.; Wang, X.; Li, E.; Xue, Z.; Bai, X. A Hybrid Attention-Aware Fusion Network (HAFNet) for Building Extraction from High-Resolution Imagery and LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, M.; Boucher, F.; Mengeot, P.; Garone, E. Experimental validation of a constrained control architecture for a multirobot bricklayer system. Mechatronics 2024, 98, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, C.P.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Z. Design and development of robotic collaborative system for automated construction of reciprocal frame structures. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 39, 1550–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, K. TrustFSDV: Framework for Building and Maintaining Trust in Self-Driving Vehicles. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 82814–82833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Sheng, W.; Liu, M. A Human–Robot Collaborative System for Robust Three-Dimensional Mapping. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 2358–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsten, O.; Martens, M.H. How can humans understand their automated cars? HMI principles, problems and solutions. Cogn. Technol. Work 2019, 21, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, H.; Pakbaz, A.; Jang, Y.; Jeong, I. Analyzing Trust Dynamics in Human–Robot Collaboration through Psychophysiological Responses in an Immersive Virtual Construction Environment. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2024, 38, 04024017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, A.F.; Klakegg, O.J. Human resilience and cultural change in the construction industry: Communication and relationships in a time of enforced adaptation. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1287483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ma, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Wen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Luo, G.; Xie, G.; Sun, C. A framework and method for Human-Robot cooperative safe control based on digital twin. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Liu, D.; Lin, Q.; Ling, G. Multi-Modal Human Action Recognition With Sub-Action Exploiting and Class-Privacy Preserved Collaborative Representation Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 39920–39933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsag, L.; Stipancic, T.; Koren, L. Towards a Safe Human–Robot Collaboration Using Information on Human Worker Activity. Sensors 2023, 23, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Aryal, A.; Awada, M.; Bergés, M.; Billington, S.L.; Boric-Lubecke, O.; Ghahramani, A.; Heydarian, A.; Jazizadeh, F.; et al. Ten questions concerning human-building interaction research for improving the quality of life. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, T.; Sergi, I.; Motroni, A.; Buffi, A.; Nepa, P.; Pirozzi, M.; Catarinucci, L.; Colella, R.; Chietera, F.P.; Patrono, L. An IoT-Aware Smart System Exploiting the Electromagnetic Behavior of UHF-RFID Tags to Improve Worker Safety in Outdoor Environments. Electronics 2022, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Delhi, S.K.V. Construction 4.0: What we know and where we are headed? J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 526–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Gao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wibranek, B.; Li, S. FedHIP: Federated learning for privacy-preserving human intention prediction in human-robot collaborative assembly tasks. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 60, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Gu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, Z. Automatic assembly of prefabricated components based on vision-guided robot. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Böhme, L.F.; Valenzuela-Astudillo, E. Mixed Reality for Safe and Reliable Human-Robot Collaboration in Timber Frame Construction. Buildings 2023, 13, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, M.; Sastry, H.; Dewangan, B.K.; Rahmani, M.K.I.; Bhatia, S.; Muzaffar, A.W.; Bivi, M.A. Intruder Detection in VANET Data Streams Using Federated Learning for Smart City Environments. Electronics 2023, 12, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, M.; Pavlovskyi, Y.; Schulenburg, E.; Traganos, K.; Ahmadi, S.; Regulin, D.; Lee, D.; Saenz, J. Novel Approach Using Risk Analysis Component to Continuously Update Collaborative Robotics Applications in the Smart, Connected Factory Model. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, S.; Castronovo, F.; Akhavian, R. Analysis of the Synergistic Effect of Data Analytics and Technology Trends in the AEC/FM Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 146, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswaran, M.; Inkulu, A.K.; Tamilarasan, K.; Bahubalendruni, M.R.; Jaideep, R.; Faris, M.S.; Jacob, N. Optimal layout planning for human robot collaborative assembly systems and visualization through immersive technologies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y. Digital twins for hand gesture-guided human-robot collaboration systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 238, 2060–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, M. Human–Robot Collaboration and Lean Waste Elimination: Conceptual Analogies and Practical Synergies in Industrialized Construction. Buildings 2022, 12, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Yan, F.; Ma, Y.; Shen, W. A novel intelligent manufacturing mode with human-cyber-physical collaboration and fusion in the non-ferrous metal industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 119, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis Dornelles, J.; Ayala, N.F.; Frank, A.G. Smart Working in Industry 4.0: How digital technologies enhance manufacturing workers’ activities. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, C.; Blume, L.B. Theorizing architectural research and practice in the metaverse: The meta-context of virtual community engagement. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Arch. Res. 2025, 19, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.C.R.; Alves, R.G.L.; Cardoso, S.P.L.; Neto, H.M.M. How Has Gamification in the Production Sector Been Developed in the Manufacturing and Construction Workplaces? Buildings 2023, 13, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Murphy, R.; Lee, S.; Ahn, C.R. Delegation or Collaboration: Understanding Different Construction Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Robotization. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04021084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ojha, A.; Shayesteh, S.; Jebelli, H.; Lee, S. Human-centric robotic manipulation in construction: Generative adversarial networks based physiological computing mechanism to enable robots to perceive workers’ cognitive load. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 50, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, Q.; Ye, Y.; Du, E.J. Embodied AI for dexterity-capable construction Robots: DEXBOT framework. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Kwon, J.H.; Kim, J.; Won, S.; Hong, D. Wearable Extra Robotic Limb System With a Constant-Orientation Mechanism for the Handling of Construction Material. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 153952–153964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, A.; Balasubramanian, G. Deep convolutional neural network object net model based cognitive digital twin for trust in human–robot collaborative manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 5141–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Khan, M.; Mehmood, O.; Dou, Q.; Bateman, C.; Magee, D.R.; Cohn, A.G. Web-based visualisation for look-ahead ground imaging in tunnel boring machines. Autom. Constr. 2019, 105, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochovski, P.; Stankovski, V. Supporting smart construction with dependable edge computing infrastructures and applica-tions. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, J.C.; Menassa, C.C.; Kamar, V.R. Interactive and Immersive Process-Level Digital Twin for Collaborative Human-Robot Construction Work. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2021, 35, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.O.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, W. Multiuser Virtual Reality-Enabled Collaborative Heavy Lift Planning in Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, D.-I.; Kang, K.-I.; Cho, H. Genetic algorithm-based steel erection planning model for a construction automation system. Autom. Constr. 2012, 24, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.F.; Leonardo, M.H.; Aurélio, M.; Andre, M.L.M. A Robotic Cognitive Architecture for Slope and Dam Inspections. Sensors 2020, 20, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, I.; Samaha, J.; Ryu, J.; Harik, R. Safety 4.0: Harnessing computer vision for advanced industrial protection. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 41, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Liu, Y.; Shayesteh, S.; Jebelli, H.; Sitzabee, W.E. Affordable Multiagent Robotic System for Same-Level Fall Hazard Detection in Indoor Construction Environments. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2022, 37, 04022042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zheng, P.; Lee, C.K.M. A Vision-Based Human Digital Twin Modeling Approach for Adaptive Human–Robot Collaboration. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleke, A.G.; Bi, L.; Fei, W. EMG-Based 3D Hand Motor Intention Prediction for Information Transfer from Human to Robot. Sensors 2021, 21, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, É.; Kilgus, D.; Landry, A.; Hmedan, B.; Pellier, D.; Fiorino, H.; Jeoffrion, C. The Impacts of Human-Cobot Collaboration on Perceived Cognitive Load and Usability during an Industrial Task: An Exploratory Experiment. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 2022, 10, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, T.; Chen, Z.; Ming, X. Application of Industrial Internet for Equipment Asset Management in Social Digitalization Platform Based on System Engineering Using Fuzzy DEMATEL-TOPSIS. Machines 2022, 10, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandín, R.; Abrishami, S. Information traceability platforms for asset data lifecycle: Blockchain-based technologies. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 10, 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polenghi, A.; Cattaneo, L.; Macchi, M. A framework for fault detection and diagnostics of articulated collaborative robots based on hybrid series modelling of Artificial Intelligence algorithms. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 1929–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Pendao, C.; Moreira, A. Real-World Deployment of Low-Cost Indoor Positioning Systems for Industrial Applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 5386–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vann, W.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, Q.; Du, E. Enabling automated facility maintenance from articulated robot Collision-Free designs. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 55, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-J.; Lee, T.-L. Designing a digital-twin based dashboard system for a flexible assembly line. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 196, 110491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, Y.I.; Alqahtani, F.K.; Bin Mahmoud, A.A. Developing a Comprehensive Smart City Rating System: Case of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04024012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Lim, S.O.; Yang, H.S. Collaborative occupancy reasoning in visual sensor network for scalable smart video surveillance. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2010, 56, 1997–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, Y.; Yu, H.; Kang, J.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Niyato, D. Data Heterogeneity-Robust Federated Learning via Group Client Selection in Industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 17844–17857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhou, H.; Fu, R.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y. Driver’s trust assessment based on situational awareness under hu-man-machine collaboration driving. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 145, 110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Han, Y.; Li, W.; Ye, X.; Yuan, Q. A Takeover Risk Assessment Approach Based on an Improved ANP-XGBoost Algorithm for Human–Machine Driven Vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 48379–48387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.N.-N.; Pham, L.H.; Nguyen, H.-H.; Tran, T.H.-P.; Jeon, H.-J.; Jeon, J.W. Universal Detection-Based Driving Assistance Using a Mono Camera With Jetson Devices. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 59400–59412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelechava, B.; American National Standards Institute. ISO 45001 Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems. 12 March 2019. Available online: https://blog.ansi.org/ansi/iso-45001-2018-occupational-health-safety-management-systems/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Askarpour, M.; Mandrioli, D.; Rossi, M.; Vicentini, F. Formal model of human erroneous behavior for safety analysis in col-laborative robotics. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 57, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, U.D.S.; Kulatunga, U.; Abdeen, F.N.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Tennakoon, M. Application of building information modelling for fire hazard management in high-rise buildings: An investigation in Sri Lanka. Intell. Build. Int. 2022, 14, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. AI Risk Management Framework. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 26 January 2023. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ding, L.; Zhou, C. Development of web-based system for safety risk early warning in urban metro construction. Autom. Constr. 2013, 34, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, H.; Wu, D. Human–Robot collaboration in construction: Robot design, perception and Interaction, and task allocation and execution. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Abu Raed, A.; Peng, Y.; Pottgiesser, U.; Verbree, E.; van Oosterom, P. How digital technologies have been applied for architectural heritage risk management: A systemic literature review from 2014 to 2024. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Aidi, A.; Haron, N.; Bakar, N. Intelligent Construction Risk Management Through Transfer Learning: Trends, Chal-lenges, and Future Strategies. Artif. Intell. Evol. 2024, 6, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, B.; Li, R.; Wan, Y. Research on the Intelligent Construction and Development of Bridge Engineering Safety Management. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 565, 03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, T.D.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the implications of digitisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Comput. Ind. 2016, 83, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, O.; Siebert, X.; Mahmoudi, S.A. Comparison Analysis of Multimodal Fusion for Dangerous Action Recognition in Railway Construction Sites. Electronics 2024, 13, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, Z.; Duan, G.; Wang, D.; Meng, Q.; Sun, Y. DMU-Net: A Dual-Stream Multi-Scale U-Net Network Using Multi-Dimensional Spatial Information for Urban Building Extraction. Sensors 2023, 23, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Persello, C.; Li, M.; Stein, A. Building use and mixed-use classification with a transformer-based network fusing satellite images and geospatial textual information. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 297, 113767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, M.; Stewart, I.; Horawalavithana, S.; Kvinge, H.; Emerson, T.; Thompson, S.E.; Pazdernik, K. Generalist multimodal ai: A review of architectures, challenges and opportunities. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.05496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes-Cubides, A.S.; Jradi, M. A review of building digital twins to improve energy efficiency in the building operational stage. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, M.-F.F.; Leung, W.-Y.J.; Chan, W.-M.D. A Data-driven approach to identify-quantify-analyse construction risk for hong kong nec projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Tang, L.C.M.; Wen, Y. An Innovative Construction Site Safety Assessment Solution Based on the Integration of Bayesian Network and Analytic Hierarchy Process. Buildings 2023, 13, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Brilakis, I.; Pikas, E.; Xie, H.S.; Girolami, M. Construction with digital twin information systems. Data-Centric Eng. 2020, 1, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Menassa, C.C.; Kamat, V.R. From BIM to digital twins: A systematic review of the evolution of intelligent building representations in the AEC-FM industry. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, R.; Mehta, N.B.; Singh, C. Modeling and Analysis of Latencies in Multi-User, Multi-RAT Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Symposium on QoS and Security for Wireless and Mobile Networks, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 October–2 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanekulla, P. Real-Time Risk Assessment in Insurance: A Deep Learning Approach to Predictive Modeling. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chenya, L.; Aminudin, E.; Mohd, S.; Yap, L.S. Intelligent Risk Management in Construction Projects: Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2022, 19, 72936–72954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Liu, B.; Shen, W. Development of an Evaluation System for Intelligent Construction Using System Dynamics Modeling. Buildings 2024, 14, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, Q.; Fu, C.; Zhang, G.; He, Y.; Li, W. Development and Engineering Application of Intelligent Management and Control Platform for the Shield Tunneling Construction Close to Risk Sources. J. Intell. Constr. 2024, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| A: Intelligent Construction | “Intelligent construction” “Smart construction” “Digital construction” “Automated construction” “Construction 4.0” “Industry 4.0 in construction” |

| B: Human–Robot Collaboration | “Human-machine collaboration” “Human-robot collaboration” “HRC,” “collaborative robots” “robots,” “man-machine interaction” “Construction robots” “Building robots” |

| C: Risk Management | “Safety management” “Worker safety” “Occupational safety” “Risk management” “Safety risks” “Construction safety” |

| Search Strings | TS = (((construct* OR build*) OR (intelligent* OR smart OR digital OR automat*)) AND ((human OR (machine* OR robot*)) AND collaborate*) AND (safe* OR risk* OR health* OR hazard* OR accident*)) |

| No. | Keyword | Frequency | Total Link Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | computer science | 69 | 66 |

| 2 | telecommunications | 27 | 26 |

| 3 | collaboration | 17 | 16 |

| 4 | digital twin | 16 | 16 |

| 5 | deep learning | 16 | 14 |

| 6 | framework | 14 | 14 |

| 7 | human-robot collaboration | 14 | 14 |

| 8 | management | 14 | 14 |

| 9 | system | 14 | 14 |

| 10 | construction | 13 | 13 |

| 11 | machine learning | 12 | 12 |

| 12 | model | 13 | 12 |

| 13 | design | 11 | 11 |

| 14 | federated learning | 11 | 11 |

| 15 | physics | 12 | 11 |

| 16 | materials science | 11 | 10 |

| 17 | safety | 10 | 10 |

| 18 | security | 10 | 10 |

| 19 | artificial intelligence | 9 | 9 |

| 20 | instruments & instrumentation | 13 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, X.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Kang, W.; Xiahou, X. Digital Technology Integration in Risk Management of Human–Robot Collaboration Within Intelligent Construction—A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Systems 2025, 13, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110974

Ding X, Xu Y, Zheng M, Kang W, Xiahou X. Digital Technology Integration in Risk Management of Human–Robot Collaboration Within Intelligent Construction—A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Systems. 2025; 13(11):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110974

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Xingyuan, Yinshuang Xu, Min Zheng, Weide Kang, and Xiaer Xiahou. 2025. "Digital Technology Integration in Risk Management of Human–Robot Collaboration Within Intelligent Construction—A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions" Systems 13, no. 11: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110974

APA StyleDing, X., Xu, Y., Zheng, M., Kang, W., & Xiahou, X. (2025). Digital Technology Integration in Risk Management of Human–Robot Collaboration Within Intelligent Construction—A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Systems, 13(11), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110974