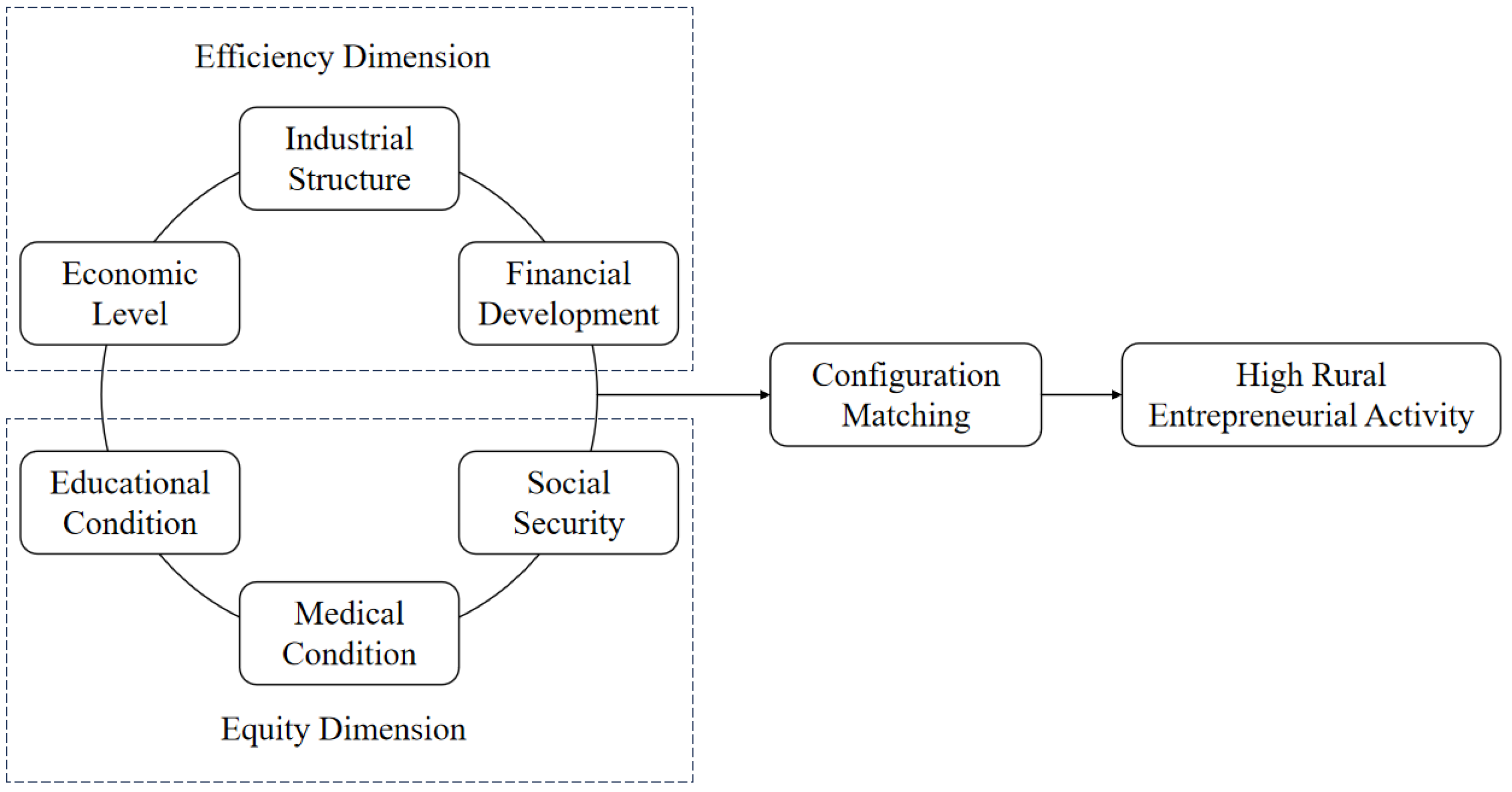

4.4. Interpretation of Configuration Results for Achieving High Rural Entrepreneurial Activity

This study conducted a configurational analysis with high rural entrepreneurial activity as the dependent variable, resulting in configurations C1, C2, C3, and C4. Among these, the raw consistency of all four configurations exceeded 0.8, with a solution consistency of 0.829, indicating that each of the four configurations and their collective set constitutes sufficient conditions for explaining high rural entrepreneurial activity. Additionally, the raw coverage of each configuration in

Table 4 represents the proportion of cases that can be explained by that configuration. It is important to note that some cases can also be explained by other configurations simultaneously. Therefore, the unique coverage refers to the extent to which a single configuration explains the cases after excluding those shared with other configurations.

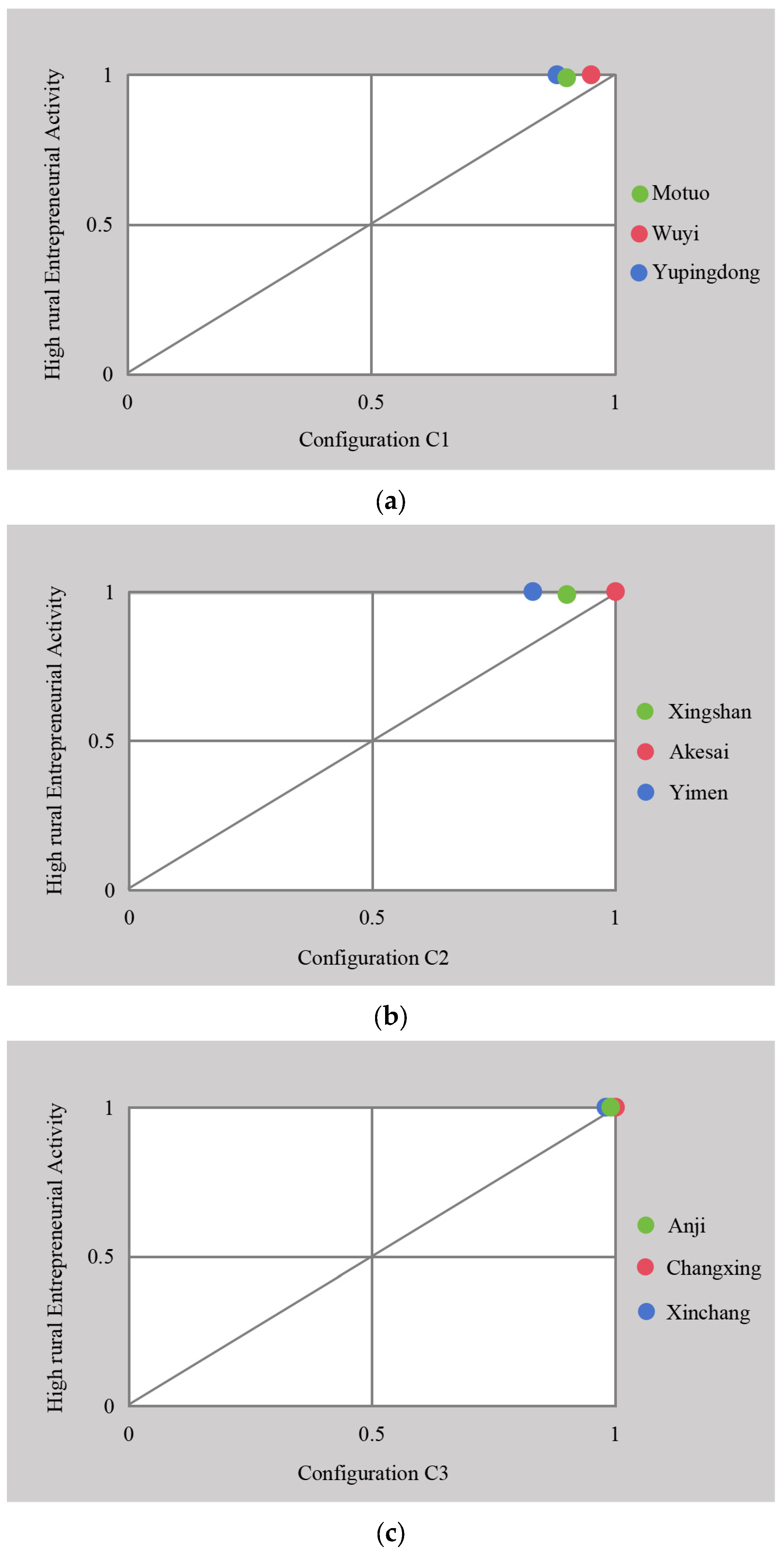

Table 4 shows that the solution coverage is 0.338, indicating that the four configurations explain 33.8% of the 982 cases. Furthermore, this study has mapped typical case diagrams for the four configurations, as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the fit between the theoretical configurations and empirical cases. Each subplot (a–d) displays typical cases for configurations C1 to C4, respectively. Among them, the

X-axis represents the membership degree of a case in the set of antecedents represented by this configuration. For example, for C1, the value of the

X-axis indicates the membership degree of the case in the configuration C1, and if the value is 1, it indicates that the case belongs to configuration C1 completely. The value of the

Y-axis indicates the membership degree of the case in the outcome set, that is, the high rural entrepreneurial activity. If the value is 1, it indicates that the case belongs to the high rural entrepreneurial activity completely. Cases positioned in the upper-right corner, which exhibit high membership in both the solution and the outcome, are considered strong typical cases for that configurational path.

The “finance and healthcare-driven” type (C1). The raw coverage of this configuration is 0.199, and its unique coverage is 0.046, indicating that nearly 20% of cases can be explained by this configuration. The core mechanism for the configuration to achieve high rural entrepreneurship activity is the efficiency dimension creates capital and market conditions, and the fair dimension guarantees human capital and risk buffers, and these co-act to form a virtuous cycle. In the efficiency dimension, a higher economic level means that the region has a strong consumption capacity and can provide entrepreneurs with a broader market space and business opportunities; while financial development can transform economic advantages into available entrepreneurial capital by providing more flexible credit products and financial support, helping entrepreneurs transform market opportunities into entrepreneurial actions. In the equity dimension, a perfect medical condition provides a relatively stable human capital guarantee for entrepreneurial activities by protecting the physical health of entrepreneurs and labor [

36], reducing the risk of entrepreneurship interruption. At the same time, sufficient social security is used as a marginal condition to reduce the risk of entrepreneurial failure by ensuring the basic living standards of entrepreneurs, thereby ensuring the ability of entrepreneurs to seize entrepreneurial opportunities. The synergistic mechanism between efficiency and equity lies in the fact that the market and financial opportunities created by economic and financial conditions need to rely on entrepreneurial abilities and willingness stimulated by medical and social security to be effectively utilized. On the contrary, the enhanced entrepreneurial ability of medical and social security also requires broad business opportunities to truly transform into entrepreneurial actions. The two systems play a role in rural entrepreneurial activity through the interactive logic of “opportunity creation-enhancement of ability”.

Typical cases of Configuration C1 include Wuyi County, Motuo County, and Yuping Dong Autonomous County, as shown in

Figure 2a. Taking Motuo County as an example, the county achieved a regional gross domestic product (GDP) of 852 million yuan in 2021, providing a solid market foundation for entrepreneurial activities. Meanwhile, as the sole financial institution in Medog County, the Medog County Branch of the Agricultural Bank of China established a financial services team to provide mobile financial services in rural areas. Through inclusive financial products such as Taxpayer e-Loan, it provided adequate financial support to small and medium-sized enterprises, helping to address the financing difficulties faced by local entrepreneurs. The Social Security Center of the County’s Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security has achieved a 99% social security card coverage rate and a 99% pension insurance participation rate, providing adequate protection for entrepreneurs to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Additionally, under the support of targeted medical assistance policies, the new Motuo County Tibetan Hospital was completed and put into use in 2021, featuring a 600-square-meter Tibetan medicine preventive healthcare specialty clinic and inpatient department, providing stable human capital conditions for entrepreneurial activities. As a result, returning entrepreneurs like the sisters Cirenlazhen have been able to engage in diverse entrepreneurial activities under the supportive conditions provided by Motuo County.

The “Industry and Education Balance” type (C2). The raw coverage of configuration C2 is 0.200 and the unique coverage is 0.020, indicating that 20% of cases can be explained by this configuration. The core mechanism for achieving high rural entrepreneurship activity is that the efficiency dimension element provides a broad business space, and the fair dimension element provides intelligence and risk buffers. The two together form a virtuous cycle of “opportunity-ability”. In the efficiency dimension, a higher economic level can provide a solid market foundation and consumption potential for entrepreneurial activities. A reasonable industrial structure means that the local existing industries are more inclined towards the tertiary industry, which will help the region form a relatively complete industrial chain and supporting facilities. This can not only lower the threshold for entrepreneurship, but also create entrepreneurial opportunities in logistics, e-commerce and other fields [

59]. In the equity dimension, perfect educational conditions can provide favorable support for entrepreneurs to accumulate entrepreneurial knowledge and skills, especially to cultivate technical workers and service personnel that match the needs of the tertiary industry, achieving a supply-demand balance between industrial demand and educational supply. At the same time, perfect social security can alleviate entrepreneurs’ concerns about entrepreneurial failure and enhance their willingness to take risks, so they are more willing to accumulate wealth by carrying out entrepreneurial activities. The synergistic mechanism between efficiency and equity lies in that the entrepreneurial opportunities provided by the efficiency dimension elements are highly dependent on the intellectual and social security provided by the fair dimension, so that they can be effectively identified and utilized; and the continuous optimization of the education and social security system is also inseparable from the economic and industrial foundation provided by the efficiency dimension. These factors form a dynamic balance between efficiency and equity, which helps entrepreneurs in rural areas fully utilize their own abilities and thus transform entrepreneurial opportunities into entrepreneurial actions.

Typical cases of the configuration C2 include Aksai Kazakh Autonomous County, Xingshan County, and Yimen County, as shown in

Figure 2b. Taking Yimen County as an example, the county’s GDP increased from 4.73 billion yuan in 2012 to 15.38 billion yuan in 2021, with its ranking among the 129 counties and cities in Yunnan Province improving from 64th to 50th, providing favorable conditions for the development of entrepreneurial activities. Additionally, Yimen County has established a modern industrial system encompassing tourism and culture, biopharmaceuticals, modern logistics, construction and real estate, and new energy, with a focus on promoting the integrated development of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries. As a result, Yimen County has achieved synergistic development between modern services and traditional services such as wholesale, retail, accommodation, and catering. From 2012 to 2021, the added value of the tertiary industry quadrupled, both extending the industrial chain and enriching entrepreneurial opportunities. Furthermore, Yimen County launched the expansion and renovation project of Yimen No. 1 High School on 9 March 2021, aiming to enhance educational capacity and address the lag in basic education. In terms of infrastructure and other support measures, Yimen County has invested 58.9 billion yuan over the past decade to implement 1395 key projects, with major infrastructure projects such as the Wuyi Expressway completed and put into use, and the rural road paving rate reaching 82%. All these achievements have collectively created favorable conditions for promoting entrepreneurial activities.

The “Financial and Educational Synergy” type (C3). The raw coverage of configuration C3 is 0.222, and the unique coverage is 0.026, indicating that 22.2% of cases can be explained by this configuration. The core mechanism for achieving high rural entrepreneurship activity lies in the fact that the market and capital foundation constructed by the efficiency dimension, the intellectual support and risk buffer provided by the fair dimension, jointly act on the rural entrepreneurship activity, especially the deep coordination between finance and education. In the efficiency dimension, a higher economic level supports entrepreneurial activities by increasing market capacity, while financial development transforms the economic foundation into diversified financial tools and credit supply, effectively reducing the financing constraints faced by entrepreneurs by providing financial support, and helping business opportunities to transform into implementable entrepreneurial projects. In the equity dimension, educational condition not only improves entrepreneurs’ key abilities, such as opportunity identification and management, and operational capabilities by improving the quality of regional human capital, but also provides high-quality talents. Social security, which is a marginal condition, strengthens entrepreneurs’ psychological sense of security and entrepreneurial desire by providing entrepreneurs with basic living security. The synergistic mechanism of efficiency and equity is prominently reflected in the coupling effect of finance and education. On the one hand, financial development provides financial support for the human capital formed by education to realize its entrepreneurial ambitions, and on the other hand, education provides entrepreneurial entities with professional capabilities for the allocation of financial resources. The two form a benign interaction on a solid economic basis, and social security guarantees the risk resistance of this path in this process, thereby forming a dynamic balance between efficiency and equity as a whole to stimulate the vitality of rural entrepreneurship.

Typical examples of Configuration 3 include Changxing County, Anji County, and Xinchang County, as shown in

Figure 2c. Taking Xinchang County as an example, the county’s comprehensive strength continued to improve steadily in 2021, with a total GDP of 51.74 billion yuan and a total retail sales of consumer goods of 18.274 billion yuan. The recovery and warming of the consumer market have facilitated entrepreneurial activities. Additionally, under the backdrop of the establishment of the “Financial Support for Rural Prosperity Alliance” by the Shaoxing Banking and Insurance Regulatory Bureau, Xinchang County actively promoted the “government-bank-insurance-enterprise” cooperation model. This model organizes villages or industries into units, with one financial institution taking the lead and others participating, forming a closely connected and efficient financial collaboration to support agricultural and rural prosperity, thereby facilitating the development of relevant market entities. Furthermore, in terms of educational condition, Xinchang County has actively increased investment in hardware facilities, improved educational conditions through optimized resource allocation, and constructed, renovated, or expanded schools. It has also deeply implemented the theory of selective education in compulsory education and implemented humanities-oriented education in high school education, continuously providing high-quality talent for entrepreneurial projects. Building on this foundation, Xinchang County has also actively tilted its fiscal and tax policies toward innovation and entrepreneurship. Since 2019, it has established a 300-million-yuan industrial fund, providing robust policy support for mass entrepreneurship and innovation, significantly reducing the cost of entrepreneurial failure. These conditions have collectively facilitated Xinchang County’s transformation from a small mountainous county in Zhejiang Province into an innovative county.

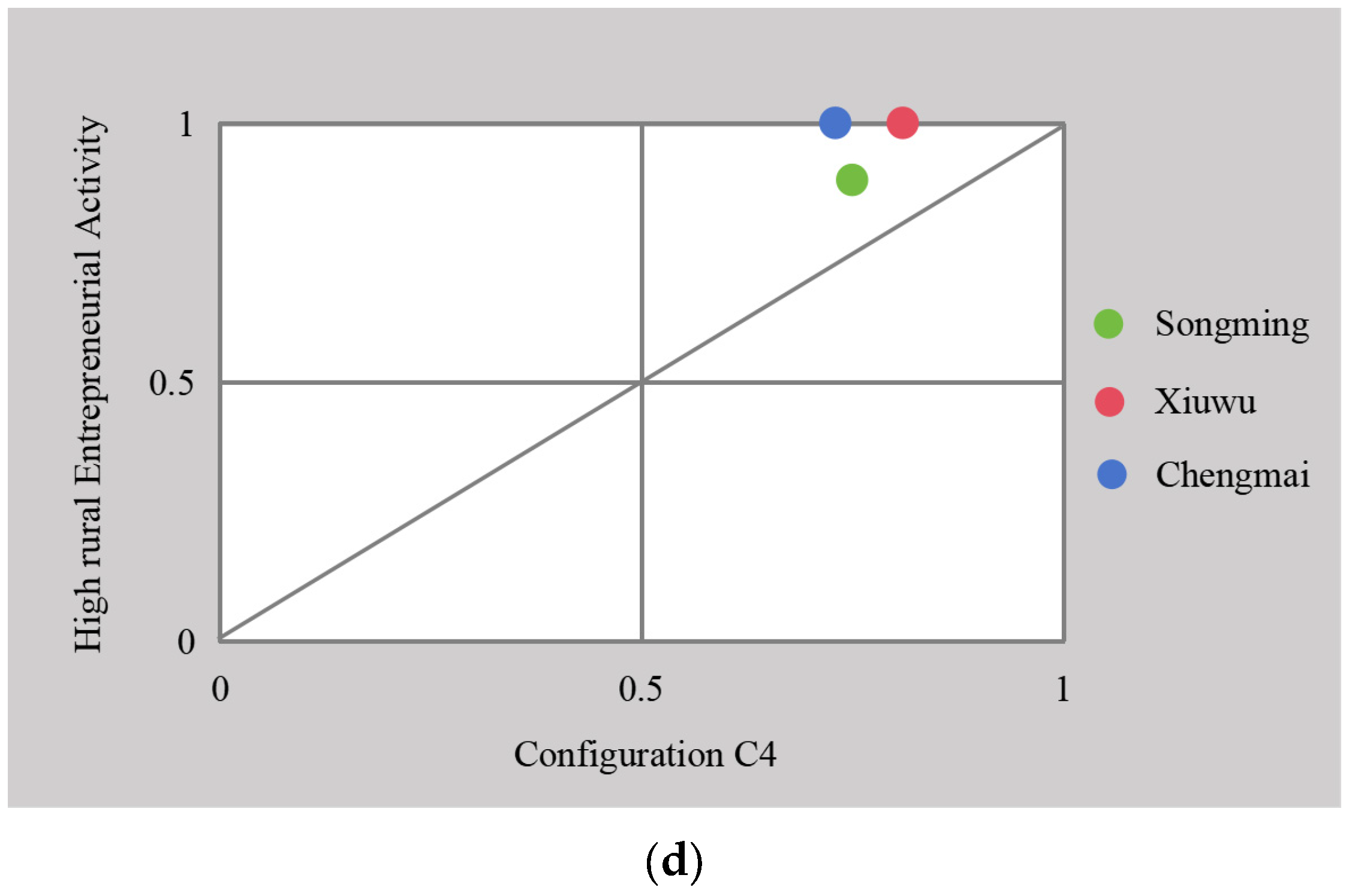

The “Industry and Healthcare Support” type (C4). The raw coverage of configuration C4 is 0.091, and the unique coverage is 0.025, indicating that 9.1% of cases can be explained by this configuration. The explanatory power of this configuration is at a lower level compared to the other three configurations, but this does not mean that the configuration is not typical. The unique feature of this configuration is that, in the absence of financial development, the linkage and complementation of efficiency and equity can be built to build a feasible, high rural entrepreneurial activity realization path. In the efficiency dimension, a higher economic level provides a market foundation, while a reasonable industrial structure enriches entrepreneurial opportunities by improving the industrial chain, helping entrepreneurial activities to obtain support in raw materials, logistics, and other aspects more easily. In the equity dimension, a perfect medical condition provides relatively stable human capital, making entrepreneurs more willing to continue to invest in entrepreneurial activities. As marginal conditions, educational conditions, and medical conditions form the pillar of human resources, improving the comprehensive quality of entrepreneurs and labor, and forming a fair support system for education and medical conditions to empower entrepreneurial capabilities. The synergistic mechanism of efficiency and equity plays a special role in this configuration. Despite the lack of financial development, the market foundation provided by the efficiency dimension can still be deeply integrated with the human resources guaranteed by the fair dimension, helping entrepreneurs make full use of informal financing methods such as acquaintance credit, and convert their own funds and social networks into entrepreneurial capital. At the same time, the combined effect of education and medical condition ensures that entrepreneurs in rural areas have the quality of grasping entrepreneurial opportunities, make up for the shortcomings of financial services, and ultimately achieve high rural entrepreneurial activity.

Typical examples of Configuration 4 include Xiuwu County, Chengmai County, and Congming County, as shown in

Figure 2d. Taking Xiuwu County as an example, as one of the first national pilot zones for all-round tourism, the county has proposed a new concept of “leading all-round tourism with all-round aesthetics”, using the homestay industry to drive the integrated development of agriculture, health and wellness, and education and research industries, thereby promoting the integrated development of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries in rural areas. Additionally, the county achieved a regional GDP of 15.41 billion yuan in 2021, providing a solid market foundation for the aforementioned industries and lowering the barriers to entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the county medical insurance bureau has established medical insurance service stations in towns such as Zhouzhuang and Qixian in Xiuwu County, actively delegating administrative authority to the village, significantly reducing health risks for farmers and entrepreneurs, and ensuring a stable supply of labor. Furthermore, Xiuwu County has focused on controlling dropout rates, rotating rural teachers, and leveraging “Internet + Education” to ensure that dropout students from poverty-stricken families remain at a dynamic zero level, continuously improving the educational capacity and teaching quality of rural schools, and ensuring a stable output of basic human resources. Based on this, Xiuwu County’s economic foundation, industrial structure, and educational condition have formed a powerful driving force for rural entrepreneurial activity, while also addressing the shortcomings in financial development.