Abstract

Declining fertility and population aging intensify labor shortages, making women’s reemployment after caregiving a policy priority. Using Taiwan as a case study, this study develops a real-time public opinion analysis system to complement delayed surveys and capture emerging barriers in labor-market reintegration. Drawing on 2022–2024 social media posts, the system applies sentiment co.mputing, clustering, and algorithmic attention to map four phases: withdrawal, intention, search, and reintegration. Findings show that younger women stress flexibility and childcare, while older returnees prioritize skill renewal and confidence rebuilding; sectoral variation supports life-cycle and clockspeed theories. Policy recommendations emphasize subsidies, training, quotas, and street-level implementation. Beyond technical contributions, the study embeds digital transformation (DT) into labor governance, showing a shift from as-is retrospective surveys to to-be-real-time monitoring. This transformation enhances policy agility, inclusiveness, and alignment with citizens’ lived experiences. The system thus functions as both a tool for rapid intervention and a DT-driven theoretical lens extending reemployment scholarship, offering transferable insights for aging societies.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

According to the United Nations (UN) [1], slowing population growth has become a global trend. It has been predicted that a quarter of all countries, including Taiwan, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Thailand, and mainland China, will experience negative population growth from 2024 onward. As a result, although approximately 30% of countries and regions (such as Taiwan, China, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia) were still benefiting from a demographic dividend in 2024, Taiwan’s share of working-age residents (aged 15–64) is projected to drop below two-thirds of the total population by 2028. The Republic of Korea (2030), Thailand (2033), China (2037), Vietnam (2040), Singapore (2041), and Indonesia (2045) are likewise expected to see their demographic dividends vanish within the next 20 years.

Over the past half-century, the share of the global population aged 65 and above has nearly doubled, rising from 5.5% in 1974 to 10.3% in 2024. Japan, Italy, Spain, France, and Germany have all become super-aged societies, with more than 20% of their populations aged 65 and above. Although European countries currently exhibit some of the world’s highest aging rates, Asia-Pacific nations are projected to overtake Europe in the coming decades. According to the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) [2], the Asia-Pacific population aged 65 and above will grow from approximately 503 million in 2024 to approximately 996 million by 2050—almost doubling over 25 years. Taiwan is also expected to see its share of elderly individuals exceed 20% in 2025, joining the ranks of super-aged societies.

This analysis shows that many countries are now grappling with a demographic transformation marked by both low fertility and rapid population aging, which in turn has produced labor shortages and other challenges associated with an aging society. Beyond artificial intelligence (AI)-driven smart manufacturing and more relaxed migrant-worker policies, actively mobilizing female labor has become a major focus in recent years [3,4,5,6]. However, reports from UN Women and the International Labor Organization (ILO) demonstrate that the feminization of unpaid domestic work has exacted a heavy toll on women [7,8,9], leading to economic dependence, old-age poverty, and social isolation. In most countries, “household work”—especially childcare and eldercare—is still viewed as a woman’s natural calling, and caregiving is seen as the centerpiece of women’s lives. Because women are stereotypically thought to be gentle, meticulous, patient, and empathic, they are automatically assigned the caregiver role, making female family members the default domestic workforce. For women, employment and household duties are not mutually exclusive but must be balanced: women seek both professional achievement and fulfillment of their maternal and domestic responsibilities. By contrast, although men likewise perceive a conflict between work and housework, domestic chores rarely impede their career progress [10]. Moreover, Hernando [11] found that women spend nearly three times as many hours as men on unpaid care and domestic work. This unequal burden substantially undermines married women’s opportunities to engage in economic and social activities, often resulting in temporary or even permanent career interruptions. Women in many societies continue to experience a persistent “double burden”: they are simultaneously expected to remain the primary caregivers within the household and are, at the same time, perceived as unreliable employees following career interruptions.

Prior scholarship has largely relied on retrospective surveys and official statistics to investigate these dynamics. Although such approaches provide valuable insights, they are inherently limited in temporal sensitivity and fail to capture the evolving stigmatization and gendered perceptions that accompany women’s reemployment trajectories. This gap underscores a critical research question: how can governments detect, in real time, the barriers and needs that shape women’s reemployment outcomes at the very moment they emerge?

In recent years, the concept of digital transformation (DT) has gained increasing attention in both business and public governance. DT is widely defined as the fundamental and ongoing process of leveraging digital technologies to reshape organizational processes, governance models, and value-creation mechanisms [12]. In contrast to incremental digitization or automation, DT represents a paradigm shift: it enables institutions to move from static, retrospective, and fragmented modes of information collection (as-is) toward dynamic, real-time, and integrated systems of decision support (to-be). This transition generates value by improving policy agility, transparency, and responsiveness, ensuring that governments can act proactively rather than reactively in addressing emerging societal challenges [13].

For labor-market governance, the relevance of DT is particularly pronounced. Traditional approaches to women’s reemployment—such as household surveys and administrative records—offer only delayed signals, limiting governments’ ability to respond to evolving stigmas, barriers, and opportunities. By contrast, DT-enabled systems such as real-time public opinion analysis transform dispersed online discourse into actionable policy intelligence. This transformation not only strengthens evidence-based policymaking but also creates new value for society: it empowers policymakers to design stage-specific interventions, detect discrimination patterns early, and tailor support for different demographic groups. Thus, situating women’s reemployment research within the broader DT framework highlights both the methodological innovation of this study and its contribution to the ongoing transformation of labor governance.

To address this research gap, the primary objective of this study is to develop a real-time public opinion analysis system, using the case of women’s reemployment in Taiwan, with a particular focus on those who have withdrawn from the labor market due to family-related factors. By utilizing algorithmic attention and sentiment computing, in addition to applying text categorization and clustering, this system aggregates online articles from Taiwanese social media that discuss similar events into tens of thousands of distinct “topics.” Using AI models, the system effectively and consistently identifies the major themes of discussion related to women’s reemployment. Subsequently, these themes are categorized based on the various challenges and situations encountered by these women in their career development. The study conducts public opinion text analysis to summarize the opportunities and challenges encountered by women before, during, and after returning to the workforce. It also explores the reemployment opportunities for women of childbearing age and older women, along with their expectations and needs regarding work–family balance measures. Importantly, the difficulties women encounter in reentering the labor market are multidimensional. They involve skill mismatches and adaptive capacity, psychological resources such as confidence and self-efficacy, and structural conditions across industries. Traditional survey instruments often struggle to capture these dynamics in a timely manner, leaving policymakers with delayed signals. To overcome this limitation, the real-time opinion analysis system developed in this study is designed to detect evolving barriers and opportunities as they occur. Beyond its technical function, the system also provides an empirical foundation for examining these challenges through established theoretical perspectives. Specifically, the competency-based view explains how women’s employability is shaped by bundles of skills and adaptive career behaviors [14,15,16,17,18]; self-efficacy theory illuminates how perceptions of confidence and anxiety influence persistence in career reentry [19]; and industry life-cycle theory clarifies why sectors operating at different clockspeeds vary in their receptivity toward returning women [4,20,21,22,23]. Through this design, the study positions the system not only as a methodological innovation but also as a tool for empirically testing and refining related theories of women’s reemployment.

1.2. Marriage, Childbearing, and Labor Force Participation Among Women in Taiwan

With marriage, pregnancy, and childbirth, women’s patterns of formal employment often undergo significant changes, leading to what is known as “job transitions.” Through such transitions, women seek to maintain continuous labor force participation. A common feature of these job transitions is the need for flexible working hours, which serve as a critical buffer mechanism that enables married women to remain in the labor market, albeit often in roles that no longer constitute the primary source of household income. After the period when the care needs of young children are the most pressing, women’s caregiving responsibilities tend to decrease, thereby increasing the likelihood of their reentry into the labor force. At this stage, women may undergo another round of job transition, aiming to shift from atypical or informal employment with relatively poor working conditions to more stable, full-time formal employment [24,25,26].

However, international data comparisons (as shown in Table 1) reveal that, although Taiwan’s female labor force participation rate (LFPR) once exhibited an “M-shaped” pattern similar to that observed in neighboring Asian countries such as Japan and the Republic of Korea, as well as in major Western economies prior to the 1990s, recent trends have diverged. Owing to changes in industrial and family structures, the LFPR of Taiwanese women now peaks at nearly 90% in the 25–29 age group (89.0% in 2023) and subsequently declines with age, without a second peak. This diverges from the “M-shaped” trajectory and indicates a downward trend that becomes particularly pronounced after the age of 50, with participation rates significantly lower than those in major Western countries as well as regional peers such as Japan, Singapore, the Republic of Korea, and Hong Kong. In 2023, the LFPR of middle-aged and older women (aged 45 and above) in Taiwan was 36.3%—slightly higher than in Italy but lower than in all other listed countries and regions. In particular, for women aged 45–64, Taiwan’s LFPR was 55.1%—substantially lower than those of major Western countries and also below those of Japan (76.9%), Singapore (70.3%), the Republic of Korea (65.5%), and Hong Kong (59.9%). These figures highlight a common pattern in Taiwan, where women often experience career interruptions during marriage and child-rearing stages and face significant challenges when attempting to reenter the workforce.

Table 1.

Female labor force participation rate by age group in major countries or regions.

Furthermore, time-series data analysis (as shown in Table 2) reveals that, although the implementation of gender-equal and family-friendly workplaces in Taiwan has steadily improved, the overall LFPR has only increased modestly, namely from 50.46% in 2013 to 51.82% in 2023—a growth of 1.36 percentage points. In contrast, the LFPR for women with a spouse or cohabiting partner slightly declined from 49.43% in 2013 to 49.34% in 2023—a decrease of 0.09 percentage points. In terms of marital status, in 2023, the LFPR for never-married women was 66.76%, which was 6.19 percentage points lower than that of never-married men (72.95%). For women with a spouse or cohabiting partner, the LFPR was 49.34%, which was 15.78 percentage points lower than that of their male counterparts (65.12%). Among divorced, separated, or widowed women, the LFPR was only 30.18%, significantly lower (21.78 percentage points) than that of men in the same category (51.96%).

Further analysis based on marital status and reasons for not being in the labor force (as shown in Table 3) indicates that, for both never-married men and women, the primary reason for not participating in the labor force was “studying or preparing for further education,” accounting for 86.59% and 80.27%, respectively. In all other marital categories, the most cited reason among men was “old age,” with rates of 55.08% (married or cohabiting), 39.42% (divorced or separated), and 45.76% (widowed). For women, however, “engaged in housework” was the most frequently reported reason, with rates of 62.25% (married or cohabiting), 38.70% (divorced or separated), and 56.02% (widowed). In addition, among women with a spouse or cohabiting partner, 14.52% cited “the need to care for children under 12” as their reason for not seeking employment; this was significantly higher than the corresponding figure for men (1.23%).

These findings suggest that Taiwanese women who are married or have family responsibilities are often expected to serve as the primary caregivers within the household. This contributes to a “discontinuous career pattern” in which women’s labor force participation is frequently interrupted [27]. After exiting the workforce, their willingness and ability to reenter employment are often constrained by persistent gender stereotypes, further reinforcing their marginalization and instability in the labor market. Situating this study within Taiwan’s demographic and labor force dynamics not only addresses an urgent national policy issue but also generates insights transferable to other societies experiencing fertility decline and labor shortages.

Table 2.

Labor force participation rate by marital status and gender in Taiwan.

Table 2.

Labor force participation rate by marital status and gender in Taiwan.

| Year | Male | Female | Gender Gap (Male–Female) (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Never Married | Married, Spouse Present, or Cohabiting | Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | Average | Never Married | Married, Spouse Present, or Cohabiting | Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | Average | Never Married | Married, Spouse Present, or Cohabiting | Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | |

| 2013 | 66.74 | 62.26 | 71.57 | 52.67 | 50.46 | 60.40 | 49.43 | 30.89 | 16.28 | 1.86 | 22.14 | 21.78 |

| 2014 | 66.78 | 63.02 | 71.23 | 53.16 | 50.64 | 60.68 | 49.78 | 30.21 | 16.14 | 2.34 | 21.45 | 22.95 |

| 2015 | 66.91 | 64.30 | 70.57 | 53.86 | 50.74 | 61.52 | 49.68 | 29.18 | 16.17 | 2.78 | 20.89 | 24.68 |

| 2016 | 67.05 | 65.91 | 69.79 | 53.80 | 50.80 | 62.05 | 49.17 | 29.81 | 16.25 | 3.86 | 20.62 | 23.99 |

| 2017 | 67.13 | 67.22 | 69.00 | 53.79 | 50.92 | 62.83 | 49.11 | 29.52 | 16.21 | 4.39 | 19.89 | 24.27 |

| 2018 | 67.24 | 68.51 | 68.28 | 54.01 | 51.14 | 63.56 | 49.27 | 28.96 | 16.10 | 4.95 | 19.01 | 25.05 |

| 2019 | 67.34 | 69.80 | 67.51 | 54.51 | 51.39 | 64.21 | 49.24 | 29.35 | 15.95 | 5.59 | 18.27 | 25.16 |

| 2020 | 67.24 | 70.79 | 66.78 | 53.48 | 51.41 | 64.67 | 49.25 | 29.94 | 15.83 | 6.12 | 17.53 | 23.54 |

| 2021 | 66.93 | 70.93 | 66.18 | 52.90 | 51.49 | 65.56 | 49.08 | 29.98 | 15.44 | 5.37 | 17.10 | 22.92 |

| 2022 | 67.14 | 72.15 | 65.66 | 53.48 | 51.61 | 66.41 | 49.00 | 30.06 | 15.53 | 5.74 | 16.66 | 23.42 |

| 2023 | 67.05 | 72.95 | 65.12 | 51.96 | 51.82 | 66.76 | 49.34 | 30.18 | 15.23 | 6.19 | 15.78 | 21.78 |

| Change in percentage points compared to 2013 | 0.31 | 10.69 | −6.45 | −0.71 | 1.36 | 6.36 | −0.09 | −0.71 | - | - | - | - |

Source: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (2024a) [28]. Unit: %.

Table 3.

Reasons for not working of persons aged 15–64 who are not in the labor force (May 2024).

Table 3.

Reasons for not working of persons aged 15–64 who are not in the labor force (May 2024).

| Total | Getting Married or Giving Birth | Enough Family Income, No Need to Work | Responsible for Taking Care of Children Aged Under 12 | Responsible for Taking Care of Older Family Aged 65 and Over | Responsible for Taking Care of Disabled Family | House- Keeping | Has Disabilities | Ill Health, Wound, or Illness (Not Disabled) | Attending Schools or Preparing to Take Entrance Exams | Waiting for Conscription | Helping with Family Business | Elderly (Including Retired Persons, Must Be Aged 50 and Over) | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 100.00 | - | 11.70 | 0.42 | 3.17 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 7.49 | 52.89 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 22.21 | 0.34 |

| Never married | 100.00 | - | 3.10 | - | 2.23 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 4.27 | 86.59 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 2.63 | 0.29 |

| Married, spouse present, or cohabiting | 100.00 | - | 26.80 | 1.23 | 3.88 | 0.53 | 1.52 | 0.36 | 10.12 | - | - | - | 55.08 | 0.48 |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | - | 26.76 | 0.53 | 3.73 | 0.43 | 1.43 | 0.34 | 10.07 | - | - | - | 56.20 | 0.52 |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | - | 36.35 | 41.35 | - | - | 1.79 | 0.86 | 9.71 | - | - | - | 9.94 | - |

| No children | 100.00 | - | 24.09 | - | 8.02 | 2.49 | 3.04 | 0.62 | 11.11 | - | - | - | 50.63 | - |

| Divorced or separated | 100.00 | - | 14.48 | 0.28 | 9.92 | 6.08 | 0.14 | 2.10 | 27.58 | - | - | - | 39.42 | - |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | - | 14.81 | - | 9.68 | 7.01 | 0.16 | 2.08 | 25.66 | - | - | - | 40.60 | - |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | - | 47.76 | 50.75 | - | - | - | - | 1.49 | - | - | - | - | - |

| No children | 100.00 | - | 10.79 | - | 11.95 | - | - | 2.31 | 41.87 | - | - | - | 33.09 | - |

| Widowed | 100.00 | - | 23.03 | - | 5.07 | 2.34 | 1.37 | 0.12 | 22.31 | - | - | - | 45.76 | - |

| Female | 100.00 | 0.20 | 7.93 | 8.27 | 4.02 | 0.62 | 39.24 | 1.25 | 2.70 | 29.04 | - | 0.08 | 5.80 | 0.85 |

| Never married | 100.00 | 0.01 | 4.69 | 0.17 | 4.31 | 0.28 | 2.10 | 2.36 | 2.18 | 80.27 | - | 0.03 | 3.21 | 0.41 |

| Married, spouse present, or cohabiting | 100.00 | 0.36 | 8.72 | 14.52 | 3.79 | 0.78 | 62.25 | 0.31 | 2.03 | 0.25 | - | 0.13 | 5.78 | 1.09 |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | 0.04 | 9.47 | 6.99 | 4.08 | 0.90 | 68.34 | 0.33 | 1.86 | 0.08 | - | 0.12 | 6.57 | 1.21 |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 88.12 | - | - | 7.97 | - | 0.52 | 1.81 | - | 0.24 | - | - |

| No children | 100.00 | 4.75 | 12.11 | - | 6.10 | 0.32 | 63.68 | 0.56 | 7.69 | - | - | - | 3.64 | 1.16 |

| Divorced or separated | 100.00 | - | 19.91 | 2.63 | 6.26 | 1.38 | 38.70 | 3.05 | 9.78 | - | - | - | 17.63 | 0.66 |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | - | 19.99 | 1.55 | 5.90 | 1.55 | 41.46 | 2.20 | 8.12 | - | - | - | 18.49 | 0.74 |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | - | - | 100.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No children | 100.00 | - | 21.76 | - | 10.36 | - | 18.45 | 11.23 | 26.17 | - | - | - | 12.04 | - |

| Widowed | 100.00 | - | 12.01 | 0.66 | 1.92 | 0.70 | 56.02 | 2.27 | 8.71 | - | - | - | 16.06 | 1.64 |

Source: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (2024b) [29]. Unit: %.

1.3. Research Objectives

Building on the theoretical perspectives and the contextual significance of Taiwan, this study aims to design and evaluate a real-time public opinion analysis system that captures women’s reemployment challenges and provides timely insights for policymaking. Beyond its methodological innovation, the system also embodies the logic of digital transformation (DT) in public governance, as it shifts from as-is reliance on retrospective surveys to a to-be state of real-time, data-driven intelligence. By leveraging DT principles, the study highlights how digital technologies can not only enhance the efficiency of information collection but also generate public value by enabling governments to anticipate needs, detect emerging stigmas, and deliver more responsive interventions.

Guided by this framework, three research questions (RQ) are proposed:

- RQ1: To what extent can real-time public opinion analysis, as a DT-enabled approach, complement traditional surveys in detecting barriers and opportunities in women’s reemployment, thereby enabling governments to respond more swiftly and proactively?

- RQ2: How do motivations, obstacles, and self-perceptions vary across demographic groups (e.g., younger versus middle-aged and older returnees), and in what ways do these patterns explain the competency-based and self-efficacy perspectives within a digitally transformed governance framework?

- RQ3: How do industry characteristics shape the possibilities for women’s reemployment, and how can industry life-cycle theory account for sectoral differences when integrated with DT-driven evidence from real-time opinion monitoring?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theories Related to Women’s Reemployment: Motivations, Barriers, Competencies, and Industry Dynamics

2.1.1. Motivations of Women Returning to the Workforce

Women’s decisions to reenter the workforce are not solely driven by the completion of family responsibilities or the emergence of economic necessity. Rather, they are shaped by a complex interplay of motivations, including career development, self-identity reconstruction, social participation, and financial considerations. The following three theoretical perspectives help explain the driving logic behind women’s reemployment:

- (1)

- Women’s Career Development Theory

Traditional career development theories, such as Super’s career stage theory [30], are largely centered on the linear career paths typical of men, often overlooking the interruptions and reentry processes that women face during marriage and childbearing stages. More recent research on women’s careers highlights that women’s career trajectories are often “nonlinear” or “discontinuous” but still involve long-term planning and goal-setting [31,32].

This theory posits that women, at different stages of life (such as marriage and childbearing, children’s independence, and parental aging), reassess the meaning of work in relation to their self-worth. This reassessment may generate motivation to reenter the workforce, which is viewed as a continuation or reconstruction of their career. Therefore, the desire for reemployment among women is closely linked to their individual life cycle.

- (2)

- Economic Incentives and Family Labor Supply Theory

According to neoclassical economics and Becker’s theory of the household economy [33], an individual’s labor force participation is the outcome of rational economic calculations within the family, including wage incentives, opportunity costs, and the division of labor within the household. When the demand for dual-income households increases, childcare expenses decrease, or a woman’s potential income rises, women’s motivation to reenter the workforce correspondingly increases.

- (3)

- Self-Efficacy and Agency Theory

According to Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy [19], an individual’s willingness to take action—such as reentering the workforce—is closely related to their confidence in achieving success. When women receive external support and opportunities for skill enhancement, their self-perception of being capable of performing well in the workplace is strengthened. This increased self-efficacy makes it more likely that intention will be translated into actual behavior [34].

Accordingly, women’s return to the workforce is shaped by career goals, family-related economic decisions, and psychological readiness. It is not merely a response to financial needs or caregiving completion; rather, it is a strategic process involving identity, life-stage reflection, and cost–benefit analysis. Career development theory shows that women reassess work across nonlinear paths; economic theory highlights shifting household incentives; and self-efficacy theory emphasizes confidence and support. Together, these perspectives reveal that reemployment reflects both personal motivations and external conditions.

2.1.2. Barriers Women Face When Reentering the Workforce

- (1)

- Reemployment Discrimination or Career Gap Bias

Women who attempt to reenter the workforce after an extended absence often face what is known as the “resume gap bias.” Employers may assume that their skills are outdated or that they lack commitment. They may even view such women as “low-productivity, high-risk” employees simply because of the gap in their employment history. As a result, these women frequently experience implicit discrimination during interviews, hiring decisions, and salary negotiations. Women reentering the workforce thus face a double burden of bias—one that stems from their gender and the career interruption itself [35].

- (2)

- Work–Family Conflict and Policy Gap

The lack of institutional support, such as flexible working hours, remote work options, on-ramp policies for returning after parental leave, and accessible childcare services, constitutes a major structural barrier to women’s successful reemployment. Even when women possess both the willingness and the capability to rejoin the workforce, the absence of supportive policies and workplace cultures often leaves them marginalized and excluded from meaningful employment opportunities [36,37].

- (3)

- Absent Fatherhood and Gendered Care Responsibility

Although women’s participation in the labor market is widely accepted in contemporary society, the underlying structure that assigns primary caregiving responsibilities to women remains largely unchallenged. Most childcare and eldercare policies still operate on implicit assumptions of female responsibility, placing a dual burden on women as caregivers and as workers. In contrast, fathers’ involvement in caregiving tends to be symbolic rather than substantive, with their actual participation often minimal or absent. This perspective highlights that the barriers to women’s reemployment are not solely workplace-related but are also deeply rooted in the unequal gender division of labor within the family, which reinforces and intensifies external structural disadvantages [38].

- (4)

- Internalized Gender Norms and Self-Devaluation Theory

Women who have long navigated male-dominated workplace cultures, frequently encountering gender bias, family role pressures, and systemic exclusion, often begin to internalize societal underestimations of their abilities and roles. This internalization can lead to self-deprecating beliefs such as “I’m not qualified,” “I’m out of touch,” or “I can’t compete with younger workers.” Furthermore, prolonged exposure to gender-unequal social and workplace environments may cause women to adopt implicit beliefs such as “motherhood should come first” or “women are less competent than men at work,” thereby placing self-imposed limitations on their job seeking and career planning. For example, women may perceive themselves as lacking in skills, unworthy of personal investment, or too old to compete with younger generations. These internalized beliefs can discourage even capable women from reentering the workforce or lead to hesitation and withdrawal during job applications, interviews, and self-promotion efforts. This is not merely a psychological issue but a reflection of the deeper structural effects of gender socialization. Internalized gender frameworks suppress women’s confidence and agency in pursuing reemployment, causing them to retreat or delay action, even when external conditions are favorable [39].

In sum, women reentering the workforce often face resume gap bias, with employers perceiving them as less capable due to career interruptions. Structural barriers, such as limited flexible work options and inadequate childcare support, further hinder their return. Deep-rooted gender norms assign caregiving roles primarily to women, reinforcing the double burden of work and family. In addition, prolonged exposure to biased environments can lead women to internalize self-doubt and undervalue their abilities, discouraging job-seeking efforts. These challenges reflect not only workplace discrimination but also systemic gender inequality within both the labor market and family structures.

2.1.3. Competency-Based View of Women’s Reemployment

The competency-based view (CBV) conceptualizes reemployment success as a function of competency bundles—observable and measurable sets of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) that enable effective performance across contexts [14,15,16]. Rather than treating women’s labor-market reintegration as a binary outcome, CBV emphasizes which configurations of competencies predict successful reentry for different demographic groups (e.g., childbearing-age versus middle-aged and older returnees). This perspective is particularly relevant for nonlinear careers, as competencies can be preserved, recombined, or re-acquired despite employment interruptions. Within this framework, three elements are pivotal to second-career transitions: (i) human capital refresh (e.g., digital, customer-facing, and care-related skills); (ii) identity work (reframing caregiving experience as transferable competencies); and (iii) adaptive career behaviors (proactive learning, networking, and flexible role crafting).

Beyond technical skills, scholars have highlighted the role of psychosocial resources such as self-efficacy, confidence, and motivation in sustaining employability and career resilience [40,41]. Recent studies further extend CBV to emerging forms of work, showing that employers and employees alike stress the importance of future-oriented competencies in non-standard employment [17], while global literature reviews emphasize the growing demand for future-ready skills in rapidly changing labor markets [18].

Building on this tradition, the present study applies CBV to women’s reemployment, arguing that employability is shaped not by single attributes but by integrated bundles of competencies that span technical abilities, adaptability, identity reconstruction, and psychological resources.

2.1.4. Industry Heterogeneity and Life-Cycle/Clockspeed Theory

Industry life-cycle theory explains how sectors evolve from fluid to mature stages, shifting required capabilities and patterns of competition [20,21]. Complementarily, clockspeed captures the pace of change in products, processes, and skills [22]. Low-clockspeed industries such as care, retail, and hospitality exhibit slower skill decay and greater tolerance for flexible work, making them more inclusive for women returning after career breaks [4,23]. In contrast, high-clockspeed sectors like technology accelerate skill obsolescence and demand continuous tenure, thereby heightening reentry barriers. This perspective underscores that women’s reemployment outcomes are deeply contingent on sectoral dynamics rather than uniform across the labor market.

2.2. Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis Systems and Digital Transformation in Policy Innovation

The growing role of public opinion analysis in governance and social research has driven the development of increasingly sophisticated systems capable of extracting meaningful insights from vast volumes of online discourse. From the perspective of digital transformation (DT), such systems illustrate how governments can transition from as-is reliance on retrospective surveys to to-be models of real-time, data-driven governance that enhance transparency, agility, and responsiveness [12,13,42,43]. By embedding digital technologies into the policy cycle, DT enables not only technical advances but also fundamental shifts in governance logic, redefining how states detect, interpret, and address emerging societal challenges.

Jin and Xu [44] emphasized that conventional opinion analysis platforms often lack thematic depth, as they focus on either macro-industry or general online events. To address this, they proposed an event-based public opinion system that employs multidimensional analysis and association rule mining to uncover hidden social relationships, enabling governments and organizations to better understand public concerns around specific issues. This approach exemplifies how DT reframes governance by creating structured intelligence from dispersed information.

Liu et al. [45] demonstrated the power of real-time sentiment tracking during the COVID-19 pandemic. By collecting data from Chinese platforms such as Weibo and WeChat, their study captured emotional trends and topic shifts over time, revealing how public sentiment interacted dynamically with policy responses and social behavior. Their use of thematic clustering and influence detection algorithms highlighted how real-world events and online discourse are deeply interconnected. In a DT perspective, such real-time sensing represents a paradigmatic move toward to-be governance models that adapt policies in step with societal sentiment.

In addition, topic evolution and predictive modeling in online sentiment have advanced. Liu et al. [46] introduced a parallel intelligence framework based on latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and cellular automata to iteratively track and forecast public opinion trends. By adapting keyword models to changing user behavior, their method provides a technical foundation for responsive governance informed by real-time discourse. This aligns with DT’s emphasis on adaptive learning and algorithmic feedback loops as mechanisms for value creation in governance.

The emotional and psychological dimensions of public opinion were further explored by Feng et al. [47], who examined reactions to AI technologies such as ChatGPT and Sora. Their study combined co-occurrence network analysis, DLUT emotion ontology, and psycholinguistic tools (LIWC) to capture subtle changes in public attitudes, from early optimism to concerns over ethics and labor. This approach underscores the need for nuanced emotional analysis in policy-sensitive areas and, within a DT framework, highlights how governments must account for evolving public values when designing interventions.

In the context of public health communication, Sha and Li [48] addressed the limitations of traditional deep learning sentiment models when applied to fragmented, short-form social media texts. They proposed a pretrained BiLSTM model enhanced with attention mechanisms, which improved accuracy in detecting sentiment within complex public health discourse. Their work illustrates how DT enables methodological innovation by integrating advanced computational tools into governance processes.

Finally, Arora et al. [49] discussed the broader application of AI in e-governance. AI-driven tools such as natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning were shown to support evidence-based policymaking by revealing public concerns, optimizing service delivery, and enabling responsive policy interventions. Their work reinforces the DT perspective that digital technologies are not merely technical enablers but transformative forces reshaping public value creation.

Taken together, the reviewed literature demonstrates how real-time public opinion and sentiment analysis systems, when situated within a digital transformation framework, provide both methodological advancements and governance innovations. These systems move beyond technical improvements in topic modeling, emotional ontology, and deep learning to represent a broader transformation of governance itself. By enabling governments to detect emerging issues earlier, design adaptive policies, and create socially responsive interventions, such systems exemplify the to-be state of DT-enabled governance, thereby advancing the frontier of policy innovation.

3. Development of a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan

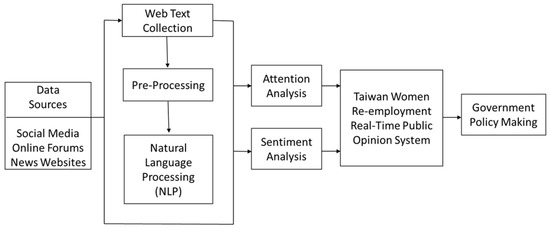

The main purpose of this study is to develop a real-time public opinion analysis system focused on women’s reemployment in Taiwan. This system centers on the collection of online public opinion data related to the “public’s concerns and discussion topics about women returning to the workforce.” Furthermore, it develops an algorithmic attention model [50] and a sentiment computing model [51] to analyze such data. Using the concept of clustering (text categorization and clustering), the system groups together online posts discussing similar events, forming tens of thousands of “topics.” Through AI-based models, the system can efficiently and reliably extract major discussion themes regarding women’s reemployment. These themes help identify when and why women leave the labor market, as well as the triggers, considerations, and challenges they face when returning to work. By gathering and analyzing real-time public opinion, the system provides valuable insights for the government to adjust relevant policies in a timely manner, such that they are more aligned with current social realities and actual needs. The system architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System architecture diagram of the real-time public opinion analysis system for women’s reemployment in Taiwan.

3.1. Public Opinion Data Positioning

Online public opinion often contains rich firsthand information. This study collects relevant cases and user-generated content to better understand the career challenges faced by women returning to the workforce. These include women’s reemployment experiences, the attitudes of employers, and public perceptions of related situations. The analysis focuses on the following topics:

- Job-seeking contexts and needs: The practical needs and experiences of women reentering the workforce, their efforts to balance family and work, and the challenges encountered during the job search process.

- Labor market constraints: Discussions related to the demand, opportunities, and limitations in the labor market for women reentering the workforce.

- Job-seeking advice and direction: Suggestions and guidance shared by online users regarding career directions for women returning to work.

- Policy and support systems: Public discussions on the support provided by government and nongovernmental organizations, including opinions and expectations regarding relevant policies, resources, and training programs.

By analyzing abundant and diverse forum content, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of public perspectives and lived experiences related to the reemployment challenges faced by women. These insights are further refined through big data aggregation techniques to inform responsive and evidence-based policymaking.

3.2. Public Opinion Data Analysis

3.2.1. Thematic Data Extraction and Filtering

This study utilizes the Po! Online Public Opinion and Social Media Database developed by DSIGroup [52] to retrospectively collect and filter public opinion data from 2022 to 2024. By applying the constructive thematic step-by-step filtering method1 proposed by Naeem et al. [53], a thematic database is constructed through iterative and editable keyword combinations and comprehensive noise-reduction techniques. This ensures that the extracted texts are truly relevant to the research topic and accurately reflect media and public discourse under the defined analytical framework.

The initial stage involves broad data collection using general topic-related keywords (e.g., “reemployment” + “women/mothers”), followed by refinement using the employment and job-seeking lexicon developed by Zheng et al. [54]. The final filtering focuses on issues commonly encountered by women returning to the workforce, such as job requirements, working hours, skill demands, and concerns related to work–family conflict.

3.2.2. Thematic Data Analysis

This study employs a self-developed algorithmic attention model and sentiment computing model to analyze each filtered text. The analysis involves word segmentation and tokenization, along with statistical assessment of text volume, data source channels, authorship, the frequency of positive and negative sentiment terms, and the proximity of key terms. These processes generate evaluative metrics such as “volume and salience of key opinion topics” and “influence and sentiment polarity analysis.”

Once the dynamic and quantitative dimensions of online public opinion are initially captured, further topic-focused analysis is conducted. This includes qualitative convergence techniques such as examining “positive and negative opinion narratives” and “keyword cloud trends.” These steps facilitate a deeper interpretation of the issues receiving attention from various perspectives and track how online discourse evolves. Ultimately, the study synthesizes and interprets the findings to identify the key opportunities and challenges that women encounter in different stages of reentering the workforce—before, during, and after reemployment.

3.3. Features and Capabilities of the Public Opinion Database

3.3.1. Web Crawling Technology

The web-based public opinion and social media database developed by DSIGroup [52] operates continuously 24 h a day, with web scraping performed every five minutes. Covering over 30,297 online platforms, the system collects more than one million pieces of public opinion data daily, enabling real-time monitoring of trends and changes in discussions concerning women returning to the workforce.

3.3.2. Sources of Textual Data

The data collection scope encompasses over 30,297 key internet nodes across Taiwan, including major online news platforms, social media sites, video and question-and-answer (Q&A) platforms, discussion forums, and blogs, thereby capturing publicly available web-based public opinion data. These sources can be broadly categorized into three types: news media, social media, and discussion forums.

Prominent and frequently referenced social media platforms include public Facebook fan pages with over 10,000 followers and high topical engagement, such as those managed by major job banks, the Ministry of Labor’s “Taiwan Jobs” portal, and well-known women’s foundations. Common and significant news media sources include the online channels of cable and terrestrial TV stations, digital versions of traditional print media, native digital news outlets, and media with official affiliations. Notable discussion forums in Taiwan include PTT’s job and salary boards, workplace discussion forums, major online bulletin boards, parenting communities, and platforms popular among Taiwanese university students, such as Dcard’s job and career sections. Drawing data from a diverse range of sources that reflect different user demographics facilitates a more meaningful interpretation of public opinion trends.

As of 2024, the DSIGroup [52] database has accumulated over 350 million web-scraped records, 8.4 billion pieces of enriched analytical data, and more than 2.17 million entries in its Chinese lexicon.

3.3.3. Cluster Analysis

This study employs the concept of “clustering” (text categorization and clustering) to group articles discussing the same event into tens of thousands of “topics.” Using AI models, these clusters are analyzed to effectively and consistently identify key themes related to women’s reemployment. Discussions are further categorized based on the specific challenges or circumstances faced by women reentering the workforce, offering a valuable reference for data interpretation.

3.4. Public Opinion Computation Models

Traditional public opinion volume analysis often analyzes each main text individually and then aggregates volume and sentiment scores to form a thematic sentiment and volume assessment [50,51]. However, such approaches overlook key dimensions, including the intensity and motivation of interactions between main posts and user comments, the relative influence of individual texts within the broader corpus over the same period, and the stance conveyed by sentiment in context. The computational models adopted in this study provide sentiment and volume indicators with the following characteristics:

- Standardization: The relative discussion intensity of different texts and topics across the internet is presented through standardized scores calculated against all texts from the same period.

- Grading: Volume and sentiment indicators are categorized into levels for easier interpretation and clearer implications for policy management.

3.4.1. Attention-Based Model

Since interaction behaviors vary across different media sources, direct comparison is difficult. Therefore, an integrated scoring system is required to assess the degree of user attention received by each main post. To calculate the attention score, an attention model is established based on user interaction types across different media platforms. These interaction types include views, likes, replies, shares, clicks, and comments. Each type of interaction is weighted by its motivational strength, with parameters calibrated through the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) proposed by Saaty [55].

To address the wide variance in raw scores, a logarithmic transformation is first applied. The transformed scores are normalized using the min–max normalization method [56], and they are subsequently categorized based on a scale of 1 to 10. A lower attention score indicates that the post received limited views or interaction from users, whereas a higher score reflects greater user engagement and visibility.

3.4.2. Sentiment Analysis Model

To compute sentiment scores, this study first establishes lexicons of positive and negative sentiment words as well as domain-specific vocabularies to identify emotionally expressive language. Following this, classification algorithms such as support vector machine (SVM), naïve Bayes (NB), and k-nearest neighbors (KNN) are applied. Using NLP, an integrated emotion computation model is constructed [57,58], trained using both supervised and unsupervised learning methods.

After standardization and grading, sentiment scores range from −10 to 10, with 10 indicating the most positive sentiment, 0 indicating neutral sentiment, and −10 indicating the most negative sentiment.

During sentiment analysis, the machine learning model assigns intensity levels to both positive and negative classes. In the NLP-based approach, dictionaries of opinion expressions, including words, phrases, and emoticons, are used for sentiment classification. The process involves (1) preprocessing the input text (e.g., normalization and part-of-speech tagging), (2) identifying opinion expressions and assigning corresponding sentiment scores, and (3) applying algorithms to generate an aggregated sentiment score for the entire text.

Validation tests show that the model achieves an accuracy rate of up to 98.3% in interpreting the emotional polarity of publicly available texts.

4. Analyzing Online Discourse on Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan

4.1. Overview of Social Media Discussions

This study focuses on analyzing online public opinion related to Taiwanese citizens’ discussions and concerns regarding women returning to the workforce after a career interruption. The analysis includes themes such as the timing and reasons behind women’s withdrawal from the labor market, as well as the motivations, considerations, and circumstances surrounding their decision to seek reemployment. The aim is to gain a deeper understanding of the concrete problems and challenges faced by women during the workforce reentry process.

To extract relevant data, a keyword-based filtering approach is employed. Keywords targeting the intended demographic include terms such as “women,” “female,” “mother,” “auntie,” “wife,” and “lady,” while terms associated with employment status include “reemployment,” “job seeking,” “looking for a job,” “parental leave,” “career break,” and “returning to work.” A structured topic-filtering method is applied to eliminate noise and isolate texts with high relevance to reemployment among women. After refinement, a total of 1833 social media texts are retained for subsequent analysis.

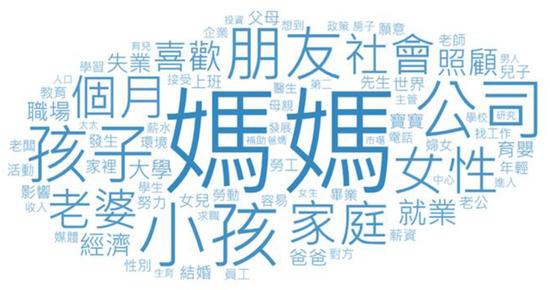

Among the thematic keywords appearing frequently in the data are “mother,” “child,” “kids,” “family,” and “caregiving.” These results highlight that a significant portion of the discussion revolves around the challenges women face in balancing family responsibilities with their efforts to return to the workforce. The keyword cloud of public opinion is shown in Figure 2 (in Chinese).

Figure 2.

Keyword word cloud from public opinion analysis in this study (in Chinese). Note: Chinese words are shown as extracted from Taiwanese online data to reflect original language use.

Many articles contain keywords such as “mother,” “child,” and “kids,” indicating that the challenge of balancing family and work is one of the core themes in public discourse. Women are often required to find an equilibrium between their familial roles and workplace responsibilities, particularly when it comes to returning to the labor market while caring for their children and households. Keywords such as “mother,” “wife,” and “family” highlight the continued significance of traditional family roles in Taiwanese society. These roles create added pressure for women, who must navigate the conflict between familial obligations and professional ambitions.

Furthermore, frequently appearing keywords such as “employment,” “company,” “economy,” “salary,” and “income” suggest a strong public concern among Taiwanese women about the financial pressures of maintaining a family life. This is especially evident in discussions about the need to increase household income. In addition, policy-related keywords such as “policy,” “subsidy,” and “parental care” reflect public expectations for stronger government support in childcare and employment-related measures.

Moreover, keywords such as “marriage,” “husband,” and “father” indicate that marriage and gender-based division of labor remain critical issues affecting women reentering the workforce in Taiwan. Although both spouses are eligible to apply for parental leave subsidies, traditional gender roles within marriage often result in women bearing a disproportionate share of the responsibility. As women return to work, they not only face professional challenges but also continue to shoulder the bulk of unpaid domestic labor. A husband’s attitude toward his wife’s employment can significantly influence a woman’s reemployment decisions and actions.

4.2. Volume Analysis of Social Media Discussions

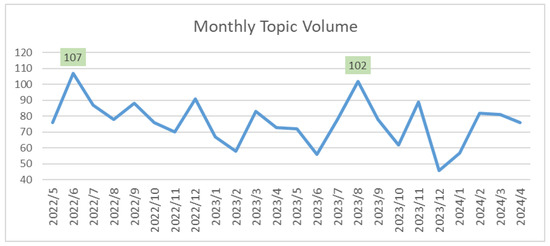

Analysis of monthly discussion volume trends reveals noticeable peaks in June 2022 and August 2023. During these periods, highly engaged posts featured topics such as the struggle to balance family and work as well as reflections on whether to have children. In addition, heated discussions on workplace attitudes toward women of childbearing age emerged, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 4.

Figure 3.

Monthly discussion volume on the issue of women’s reemployment in Taiwan.

Table 4.

Key articles from peak months on the issue of women’s reemployment in Taiwan.

4.3. Framework for Analyzing Social Media Discussions

This study employs a timeline-based phase analysis to systematically understand the workplace experiences of women in Taiwan, tracing their journey from temporarily leaving the workforce to reentering employment. Women go through distinct stages during this journey, each with unique challenges and needs. This framework helps systematically identify the specific issues faced by women at each stage, capturing their sentiments and public opinion dynamics over time and further revealing their key concerns and difficulties.

By analyzing different phases, the framework also aids in assessing the impact of existing policies on women’s workforce reentry and identifies shortcomings in the implementation of policies that aim to promote reemployment for women.

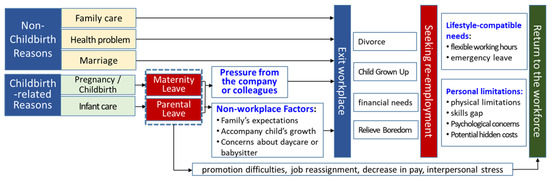

After consolidating the public opinion data, the study summarizes a social discussion analysis framework captioned “key considerations at each stage of women’s exit from and return to the workforce,” as illustrated in Figure 4. This framework is divided into three main processes: What reasons lead professional women to exit the workforce? At what time do thoughts of reemployment arise? What expectations and challenges are encountered during the process of returning to work?

Figure 4.

Public opinion analysis framework for key considerations at each stage of women’s exit from and return to the workforce.

4.4. Public Opinion Analysis of Women Returning to the Workforce

4.4.1. Common Reasons for Women Leaving the Workforce

- (1)

- Non-Childbirth Reasons

According to Taiwan’s public discussions, having family members who require long-term care is one of the major reasons women are forced to leave the workforce. Netizens shared their personal experiences of having to frequently accompany family members to medical treatments, which made it difficult for them to balance work and family and ultimately led them to resign.

Women’s own health conditions comprise another key factor. Some netizens mentioned that their health deteriorated after childbirth or illness, requiring extended recovery or treatment. This prevented them from continuing to work, prompting them to temporarily leave the workforce.

Marriage and family expectations also significantly influence women’s decisions to exit the workforce. For example, some netizens shared that they resigned due to requests from their parents-in-law or husbands to assist with family businesses or household chores; others mentioned reaching a mutual agreement with their spouses to focus on unpaid domestic work and become full-time homemakers.

- (2)

- Childbirth-Related Reasons

- A.

- Unfriendly Leave Policies

Some netizens reported encountering difficulties and unfair treatment when applying for maternity or parental leave without pay. For instance, they faced unfriendly attitudes from employers during pregnancy, such as difficulties obtaining leave for prenatal checkups or being forced to work even during unstable pregnancies, ultimately leading them to resign. Such hostile environments created both overt and covert pressures, along with a strong sense of insecurity.

Some companies pressured employees applying for parental leave to resign directly. Netizens shared experiences of being told that applying for parental leave was equivalent to resigning, with some even being required to sign resignation documents. In other cases, excessively long approval processes for parental leave left women or their spouses without timely access to needed leave during childcare or recovery periods.

Furthermore, some netizens stated that they gave up better job opportunities or career advancement because they were concerned about unfriendly leave policies at new companies, fearing that these workplaces would not accommodate their childcare needs.

- B.

- Pressure from Companies or Colleagues

Some women were laid off after their parental leave ended. Netizens shared experiences of returning to work after parental leave, only to be told that their positions were no longer available, forcing them to resign. Others mentioned receiving layoff notices within a week after childbirth, under the pretext of company downsizing, leaving them to cope with job loss stress at a time when they should have been focused on recovering and caring for their newborns.

In addition, netizens recounted experiences of workplace cold-shouldering and stigmatization. Supervisors sometimes became indifferent after learning about employees’ pregnancies or parental leave applications, with some even spreading negative rumors about them. Such actions severely impacted women’s work environments and mental health. For example, one netizen mentioned feeling neglected during her pregnancy by her supervisor, who deemed her incapable of properly handling work duties; this caused significant stress and fatigue, ultimately leading her to resign.

Employers also encounter challenges when employees apply for maternity or parental leave. Smaller businesses, in particular, often rely on other staff to temporarily fill these positions, which increases workloads and affects overall efficiency. Furthermore, companies may face difficulties with role reassignments and staff transitions. In many cases, companies prefer replacement employees who can quickly adapt and perform well to ensure business continuity and efficiency. However, if replacement workers excel, employers may prefer to retain them in the position to avoid further disruptions, posing a dilemma on whether to reinstate the original employees. Thus, companies must carefully balance protecting employees’ rights with maintaining normal operations.

- C.

- Decision to Pursue Full-Time Childcare

After childbirth, some women choose to leave the workforce to become full-time caregivers. This choice is influenced by various factors, such as family expectations, the lack of suitable childcare services, or simply a desire to personally care for their children.

Family expectations play a significant role in such decisions. Many women decide to resign after childbirth due to pressure or expectations from husbands or elders. Netizens shared experiences of resigning to care for their children under the influence of their spouses or parents-in-law.

Concerns about childcare services or nannies are also key reasons behind some women exiting the workforce. A number of netizens expressed distrust toward external caregivers, which prompted them to take on full-time childcare responsibilities.

In addition, many mothers believe that time spent with their children is fleeting and irreplaceable. Netizens shared that they did not want to miss out on their children’s formative years, choosing instead to stay at home and focus on full-time caregiving.

4.4.2. Challenges Faced by Women Returning to Their Original Workplaces

Pregnancy and childbirth have a significant impact on women’s workplace resources and career development. Even after returning to their original workplaces following maternity or parental leave, women often face challenges such as negative impacts on performance evaluations, limited promotion opportunities, and the risk of layoffs or job reassignment.

After their maternity or parental leave, some women find that their original positions have been reassigned or replaced. Netizens shared experiences of being unable to return to their previous roles despite successfully applying for parental leave. Others mentioned that, upon applying for parental leave, their supervisors warned them that they might face job reassignment or even termination after their leave, causing them significant stress and anxiety.

Moreover, companies tend to avoid assigning important tasks to employees who are about to take extended leave. Netizens shared that, during pregnancy, they were told they would no longer be assigned new projects and were only given supporting tasks because their supervisors were concerned about incomplete handovers. Although such arrangements may help ensure short-term operational stability, they can negatively affect employees’ long-term career development.

During pregnancy or after maternity leave, women’s performance evaluations and promotion opportunities are often impacted. Some netizens mentioned that, even though they did not take parental leave—and even worked during their postpartum confinement period—their performance ratings were still the lowest despite having the best work results, simply because male supervisors believed, “You were absent during part of your pregnancy or maternity leave.” This shows that women’s work performance can be unfairly assessed, even if their leave periods had no actual impact on their job output. Others noted that taking maternity or parental leave directly affected their performance evaluations, company bonuses, and profit-sharing because of reduced attendance days; this highlights the structural barriers women face in the workplace due to childbirth.

From the employers’ perspective, arranging substitute staff for employees on parental leave often involves balancing costs and efficiency. For small enterprises, the cost of hiring temporary replacements can be high. If they hire new employees during the leave period, managing the return of the original employees becomes a new challenge. As one netizen put it, “Parental leave is awkward by nature. You’re gone for six months or a year—whether the company should hire someone else or not becomes a troublesome issue.” Thus, companies are often caught in a dilemma: trying to protect the rights of the original employees while ensuring proper arrangements for replacement workers.

In addition, companies worry that employees returning from maternity or parental leave may face skill degradation or require time to readapt to their jobs. For instance, one netizen stated, “I’d rather not train a colleague who is about to take maternity leave—who knows how much she’ll remember six months later?” Others pointed out that the main reason women face career stagnation after childbirth is because they are unable to work overtime at will or must frequently take emergency leave to care for sick children. Consequently, over time, companies may become reluctant to assign them important tasks.

4.4.3. Motivations of Women Returning to the Workforce

According to discussions among Taiwanese netizens, financial pressure is a major motivation driving women to return to the workforce. Some women found that relying solely on the income of their husbands was insufficient to support the family, prompting them to seek employment. Others mentioned that the loss of financial support following divorce forced them to reenter the job market.

Furthermore, when their children grow older and become more independent, women often have more time and energy, leading them to consider returning to work. Full-time mothers who have spent long periods at home caring for their children may also gradually begin to feel bored and seek employment as a way to keep themselves occupied or to achieve personal fulfillment and foster self-worth.

4.4.4. Job-Seeking Situations for Women Returning to the Workforce

- (1)

- Women of Childbearing Age

According to discussions among Taiwanese netizens, women of childbearing age tend to have higher expectations and demands regarding “work–family balance” measures when reentering the workforce. They hope their jobs can accommodate their family lifestyle, with children’s needs being the top priority. Commonly expected conditions include the following:

- A.

- Leaving Work on Time

As these women need to pick up and drop off their children from school, they prefer fixed working hours and jobs that allow them to leave on time, with minimal or no overtime.

- B.

- Ability to Take Emergency Leave

These women seek jobs that will allow them to take sudden leave for unexpected situations, such as receiving a call from a daycare center about a sick child.

- C.

- Flexible Working Hours, Shifts, or Part-Time Options

Part-time and flexible jobs are popular choices among women of childbearing age, as these positions offer greater flexibility to meet family needs.

- D.

- Proximity to Home

These women prefer jobs located near their homes, with convenient commutes, to save time and better balance work and family responsibilities.

- (2)

- Older Women

According to Taiwanese netizens, middle-aged and older women face more constraints when seeking to return to the workforce and often encounter different challenges compared to women of childbearing age. As older women are approaching retirement age, companies are generally reluctant to invest in long-term training for them, making their “job-readiness” a crucial factor for reemployment. Common challenges include the following:

- A.

- Age and Physical Limitations

Due to age and limited physical stamina, it is often difficult for middle-aged and older women to take on physically demanding or long-hour jobs. Thus, they must look for positions that match their physical capacity.

- B.

- License and Skill Requirements

Many jobs require specific licenses or skills, and some middle-aged and older women may face difficulties in securing employment due to a lack of such qualifications.

- C.

- Psychological Concerns

Long absences from the workforce or repeated setbacks in job hunting can lead to low self-confidence among middle-aged and older women. Overcoming these psychological barriers is essential for actively facing job-seeking challenges.

- D.

- Potential Cost Concerns

Companies may worry about the potential costs of hiring these women, such as the possibility of frequent leave to care for children or family members or concerns that the employee may retire just a few years after being hired.

4.4.5. The Impact of Family Planning on Job Seeking

The potential costs associated with employees’ “family planning” can affect all female job seekers and career changers, even those who are not returning to the workforce after a career break. During the job-seeking process, women often face questions about their reproductive plans and encounter potential discrimination, which may negatively impact their career development and job stability.

Taiwanese netizens mentioned that, during job interviews after marriage, interviewers were often highly concerned about their plans for having children. Common questions included when they planned to have children and who would take care of the child. In some cases, interviewers even explicitly stated that employees could not take sudden leave for child-related emergencies in the future.

In the comments section, some netizens admitted that, if they were hiring managers, they would also tend to avoid hiring married women who have not yet had children, as these employees might apply for two years of parental leave shortly after reaching the required length of service and leave the hiring managers struggling to explain the situation to their superiors.

4.4.6. Advantages of Women Returning to the Workforce

According to Taiwanese netizens, many companies actually appreciate the qualities of women returning to the workforce. For example, working mothers tend to highly value job stability due to their family responsibilities, making them less likely to change jobs easily. In addition, mothers with children often possess strong time management skills, enabling them to complete tasks efficiently within limited working hours.

If these women have other family members who can assist with childcare, it further reduces employers’ concerns about potential leave requests due to family issues. Companies that recognize these strengths and offer appropriate support and flexible work arrangements are more likely to retain such talented employees.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the complex and nonlinear trajectories that women in Taiwan face when reentering the labor market after caregiving or career interruptions. By leveraging a real-time public opinion analysis system, the study moves beyond the delayed and static nature of traditional surveys to capture evolving dynamics in stigma, motivations, and institutional barriers. This methodological innovation not only enriches empirical understanding but also provides a theoretical bridge linking digital trace data to related women’s reemployment theories.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, the results support the competency-based view, showing that women’s reemployment success depends on bundles of competencies and adaptive behaviors rather than a binary employed/unemployed distinction. Younger women emphasize flexibility and childcare support, while middle-aged and older returnees prioritize skill renewal and signaling competence. This aligns with the notion that employability is multidimensional and contingent on life stage.

Second, the findings advance self-efficacy theory by demonstrating how online discourse reflects fluctuations in confidence, anxiety, and self-doubt. Expressions of optimism and supportive narratives strengthen efficacy beliefs, whereas stigmatizing comments exacerbate withdrawal. This underscores the role of psychological resources in sustaining job-search persistence and highlights the importance of interventions that rebuild self-confidence.

Third, the evidence validates industry life-cycle/clockspeed theory, showing that low-clockspeed industries such as care, retail, and hospitality are more receptive to career returnees, while high-clockspeed sectors such as fast-cycle technology amplify skill obsolescence and penalize discontinuous careers. This theoretical framing challenges the assumption of homogeneous labor demand and points toward sector-sensitive employment strategies.

Beyond the competency-based, self-efficacy, and industry life-cycle perspectives, this study also advances the discourse on digital transformation (DT) in public governance. By contrasting the as-is condition—policy reliance on retrospective surveys—with the to-be state—real-time digital trace monitoring—the study demonstrates how DT embodies both transformation and value creation. Transformation occurs as labor-market monitoring shifts from static, lagged, and fragmented information to dynamic, continuous, and integrative intelligence. Value is generated through enhanced policy agility, improved inclusiveness for marginalized groups, and greater alignment between institutional responses and citizens’ lived experiences.

From a theoretical standpoint, embedding DT into women’s reemployment research illustrates how digital technologies can reshape not only the tools but also the governance logic of policy interventions. As highlighted by Vial [12] and Mergel et al. [13], DT is not simply technological adoption but a paradigmatic shift that redefines the way organizations sense, interpret, and respond to societal needs. This study contributes to that perspective by showing how DT-enabled systems convert dispersed online discourse into structured signals that can guide stage-specific and sector-sensitive labor strategies. In doing so, it extends DT theory into the domain of labor policy innovation, providing a transferable model for other demographic and employment challenges.

5.2. Policy Implications

From a policy perspective, the integration of Kingdon’s multiple-streams framework [59] is essential. The problem stream (women’s reemployment gaps), political stream (demographic pressures such as declining fertility), and policy stream (real-time opinion monitoring) converge to create a policy window for institutional reform. By providing algorithmic alerts, the system enables street-level bureaucracies—including employment service centers, labor bureaus, and vocational training institutes—to detect emerging issues earlier and respond with timely interventions.

At a strategic level, the findings emphasize the importance of adopting a balanced and integrated policy mix rather than relying on isolated measures. Specifically, three interdependent directions should guide reform:

- Economic incentives, which can reduce employer risk and encourage sustained retention.

- Capacity-building initiatives, which enhance women’s skills, adaptability, and self-efficacy.

- Regulatory frameworks, which institutionalize fairness and normalize flexible work arrangements.

These principles establish the foundation for concrete recommendations, which are elaborated in the Conclusion and Recommendations section.

5.3. Broader Contributions and Limitations

Methodologically, this study demonstrates how digital governance tools can transform fragmented online discourse into structured policy intelligence, providing both timeliness and granularity that traditional surveys lack.

Theoretically, it shows how digital trace monitoring can test, extend, and refine related women’s reemployment theories, thereby advancing scholarly debates in labor-market reintegration.

Practically, it provides transferable lessons for other aging societies and labor contexts where women’s employment is a critical issue.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, it primarily relies on public social media data from Taiwan, which, while effective in capturing real-time public opinion, may underrepresent groups affected by the digital divide—such as women who seldom use the internet or digital tools—thereby limiting the inclusiveness of the findings. Second, discourse analysis reflects perceptions and narratives rather than objective employment outcomes, requiring triangulation with administrative records or survey data for validation. Finally, the generalizability of the results is shaped by Taiwan’s cultural and institutional context, and future research should extend cross-nationally to test broader applicability. These limitations, however, also highlight avenues for future inquiry, such as integrating multiple data sources and conducting cross-cultural validation.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study developed a real-time public opinion analysis system to address women’s reemployment challenges in Taiwan. By leveraging natural language processing, sentiment computing, and clustering, the system transforms fragmented online discourse into structured policy intelligence. The results demonstrate that women’s reemployment trajectories are nonlinear, shaped by caregiving responsibilities, demographic stage, and industry dynamics. Importantly, the system serves not only as a technical tool but also as a theory-driven framework that extends related theories of women’s reemployment and advances the discourse on digital transformation (DT) in labor governance.

6.1. Responses to Research Questions and Theoretical Contributions

This study set out to address a critical research gap by examining how real-time digital trace data can illuminate the challenges and opportunities of women’s reemployment in Taiwan. To this end, three research questions were posed, each anchored in established theoretical perspectives. The findings not only provide empirical answers but also extend the competency-based, self-efficacy, and industry life-cycle frameworks in meaningful ways, while embedding DT as a paradigmatic shift that reshapes governance logic.

- RQ1: Real-time opinion analysis complements traditional surveys by capturing stigma, self-doubt, and conditional optimism earlier and more dynamically, enabling governments to respond more swiftly with stage-specific interventions.

- RQ2: Differences across demographic groups—flexibility and childcare for younger women versus skill renewal and confidence rebuilding for middle-aged and older returnees—explain both the competency-based view and self-efficacy theory in the context of nonlinear career reentry.

- RQ3: Sectoral variation validates industry life-cycle/clockspeed theory: low-clockspeed sectors absorb returnees more readily, while high-clockspeed sectors exacerbate barriers through rapid skill obsolescence and continuous tenure requirements.

Beyond these, the findings also highlight that DT enables governments to move from an as-is reliance on retrospective surveys toward a to-be state of real-time, integrative monitoring, thereby creating both transformation and public value.

Together, these findings establish the dual role of the system as both a scholarly mechanism linking digital trace data to theory and a policy instrument for rapid and differentiated interventions.

6.2. Summary of Research Findings

The empirical analysis reveals several urgent challenges and insights that extend both policy understanding and theoretical debates.

- Untapped female labor potential remains significant, yet systemic barriers—such as stigma, inadequate childcare, and inflexible work arrangements—continue to reduce reemployment. This underscores the gap between latent workforce supply and institutional readiness.

- Obstacles intensify with age, generating a structural segmentation between younger women, who demand flexibility and childcare, and middle-aged and older returnees, who emphasize skill renewal and confidence rebuilding. This life-stage divide illustrates how reemployment outcomes vary by competency bundles and efficacy beliefs.

- Institutional and cultural biases reinforce exclusion. Caregiving stereotypes, career-break stigma, and inconsistent parental-leave practices intersect to magnify barriers. These findings demonstrate how discourse-level stigma translates into diminished self-efficacy and constrained labor-market behavior.

- Group-specific needs are pronounced. Younger women seek conditional participation opportunities tied to family support, while middle-aged and older returnees stress re-skilling, signaling, and psychological reinforcement. This aligns with the competency-based and self-efficacy frameworks by showing how resource needs vary across demographic cohorts.

- Industry characteristics shape reemployment pathways. Online narratives point to relatively inclusive reentry in low-clockspeed sectors (care, retail, hospitality) and more rigid exclusion in high-clockspeed industries (technology), validating life-cycle and clockspeed theory.