Developing a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan: A Digital Transformation Approach to Policy Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

1.2. Marriage, Childbearing, and Labor Force Participation Among Women in Taiwan

| Year | Male | Female | Gender Gap (Male–Female) (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Never Married | Married, Spouse Present, or Cohabiting | Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | Average | Never Married | Married, Spouse Present, or Cohabiting | Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | Average | Never Married | Married, Spouse Present, or Cohabiting | Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | |

| 2013 | 66.74 | 62.26 | 71.57 | 52.67 | 50.46 | 60.40 | 49.43 | 30.89 | 16.28 | 1.86 | 22.14 | 21.78 |

| 2014 | 66.78 | 63.02 | 71.23 | 53.16 | 50.64 | 60.68 | 49.78 | 30.21 | 16.14 | 2.34 | 21.45 | 22.95 |

| 2015 | 66.91 | 64.30 | 70.57 | 53.86 | 50.74 | 61.52 | 49.68 | 29.18 | 16.17 | 2.78 | 20.89 | 24.68 |

| 2016 | 67.05 | 65.91 | 69.79 | 53.80 | 50.80 | 62.05 | 49.17 | 29.81 | 16.25 | 3.86 | 20.62 | 23.99 |

| 2017 | 67.13 | 67.22 | 69.00 | 53.79 | 50.92 | 62.83 | 49.11 | 29.52 | 16.21 | 4.39 | 19.89 | 24.27 |

| 2018 | 67.24 | 68.51 | 68.28 | 54.01 | 51.14 | 63.56 | 49.27 | 28.96 | 16.10 | 4.95 | 19.01 | 25.05 |

| 2019 | 67.34 | 69.80 | 67.51 | 54.51 | 51.39 | 64.21 | 49.24 | 29.35 | 15.95 | 5.59 | 18.27 | 25.16 |

| 2020 | 67.24 | 70.79 | 66.78 | 53.48 | 51.41 | 64.67 | 49.25 | 29.94 | 15.83 | 6.12 | 17.53 | 23.54 |

| 2021 | 66.93 | 70.93 | 66.18 | 52.90 | 51.49 | 65.56 | 49.08 | 29.98 | 15.44 | 5.37 | 17.10 | 22.92 |

| 2022 | 67.14 | 72.15 | 65.66 | 53.48 | 51.61 | 66.41 | 49.00 | 30.06 | 15.53 | 5.74 | 16.66 | 23.42 |

| 2023 | 67.05 | 72.95 | 65.12 | 51.96 | 51.82 | 66.76 | 49.34 | 30.18 | 15.23 | 6.19 | 15.78 | 21.78 |

| Change in percentage points compared to 2013 | 0.31 | 10.69 | −6.45 | −0.71 | 1.36 | 6.36 | −0.09 | −0.71 | - | - | - | - |

| Total | Getting Married or Giving Birth | Enough Family Income, No Need to Work | Responsible for Taking Care of Children Aged Under 12 | Responsible for Taking Care of Older Family Aged 65 and Over | Responsible for Taking Care of Disabled Family | House- Keeping | Has Disabilities | Ill Health, Wound, or Illness (Not Disabled) | Attending Schools or Preparing to Take Entrance Exams | Waiting for Conscription | Helping with Family Business | Elderly (Including Retired Persons, Must Be Aged 50 and Over) | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 100.00 | - | 11.70 | 0.42 | 3.17 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 7.49 | 52.89 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 22.21 | 0.34 |

| Never married | 100.00 | - | 3.10 | - | 2.23 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 4.27 | 86.59 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 2.63 | 0.29 |

| Married, spouse present, or cohabiting | 100.00 | - | 26.80 | 1.23 | 3.88 | 0.53 | 1.52 | 0.36 | 10.12 | - | - | - | 55.08 | 0.48 |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | - | 26.76 | 0.53 | 3.73 | 0.43 | 1.43 | 0.34 | 10.07 | - | - | - | 56.20 | 0.52 |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | - | 36.35 | 41.35 | - | - | 1.79 | 0.86 | 9.71 | - | - | - | 9.94 | - |

| No children | 100.00 | - | 24.09 | - | 8.02 | 2.49 | 3.04 | 0.62 | 11.11 | - | - | - | 50.63 | - |

| Divorced or separated | 100.00 | - | 14.48 | 0.28 | 9.92 | 6.08 | 0.14 | 2.10 | 27.58 | - | - | - | 39.42 | - |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | - | 14.81 | - | 9.68 | 7.01 | 0.16 | 2.08 | 25.66 | - | - | - | 40.60 | - |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | - | 47.76 | 50.75 | - | - | - | - | 1.49 | - | - | - | - | - |

| No children | 100.00 | - | 10.79 | - | 11.95 | - | - | 2.31 | 41.87 | - | - | - | 33.09 | - |

| Widowed | 100.00 | - | 23.03 | - | 5.07 | 2.34 | 1.37 | 0.12 | 22.31 | - | - | - | 45.76 | - |

| Female | 100.00 | 0.20 | 7.93 | 8.27 | 4.02 | 0.62 | 39.24 | 1.25 | 2.70 | 29.04 | - | 0.08 | 5.80 | 0.85 |

| Never married | 100.00 | 0.01 | 4.69 | 0.17 | 4.31 | 0.28 | 2.10 | 2.36 | 2.18 | 80.27 | - | 0.03 | 3.21 | 0.41 |

| Married, spouse present, or cohabiting | 100.00 | 0.36 | 8.72 | 14.52 | 3.79 | 0.78 | 62.25 | 0.31 | 2.03 | 0.25 | - | 0.13 | 5.78 | 1.09 |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | 0.04 | 9.47 | 6.99 | 4.08 | 0.90 | 68.34 | 0.33 | 1.86 | 0.08 | - | 0.12 | 6.57 | 1.21 |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 88.12 | - | - | 7.97 | - | 0.52 | 1.81 | - | 0.24 | - | - |

| No children | 100.00 | 4.75 | 12.11 | - | 6.10 | 0.32 | 63.68 | 0.56 | 7.69 | - | - | - | 3.64 | 1.16 |

| Divorced or separated | 100.00 | - | 19.91 | 2.63 | 6.26 | 1.38 | 38.70 | 3.05 | 9.78 | - | - | - | 17.63 | 0.66 |

| Children all aged 6 years and over | 100.00 | - | 19.99 | 1.55 | 5.90 | 1.55 | 41.46 | 2.20 | 8.12 | - | - | - | 18.49 | 0.74 |

| With children aged under 6 years | 100.00 | - | - | 100.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No children | 100.00 | - | 21.76 | - | 10.36 | - | 18.45 | 11.23 | 26.17 | - | - | - | 12.04 | - |

| Widowed | 100.00 | - | 12.01 | 0.66 | 1.92 | 0.70 | 56.02 | 2.27 | 8.71 | - | - | - | 16.06 | 1.64 |

1.3. Research Objectives

- RQ1: To what extent can real-time public opinion analysis, as a DT-enabled approach, complement traditional surveys in detecting barriers and opportunities in women’s reemployment, thereby enabling governments to respond more swiftly and proactively?

- RQ2: How do motivations, obstacles, and self-perceptions vary across demographic groups (e.g., younger versus middle-aged and older returnees), and in what ways do these patterns explain the competency-based and self-efficacy perspectives within a digitally transformed governance framework?

- RQ3: How do industry characteristics shape the possibilities for women’s reemployment, and how can industry life-cycle theory account for sectoral differences when integrated with DT-driven evidence from real-time opinion monitoring?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theories Related to Women’s Reemployment: Motivations, Barriers, Competencies, and Industry Dynamics

2.1.1. Motivations of Women Returning to the Workforce

- (1)

- Women’s Career Development Theory

- (2)

- Economic Incentives and Family Labor Supply Theory

- (3)

- Self-Efficacy and Agency Theory

2.1.2. Barriers Women Face When Reentering the Workforce

- (1)

- Reemployment Discrimination or Career Gap Bias

- (2)

- Work–Family Conflict and Policy Gap

- (3)

- Absent Fatherhood and Gendered Care Responsibility

- (4)

- Internalized Gender Norms and Self-Devaluation Theory

2.1.3. Competency-Based View of Women’s Reemployment

2.1.4. Industry Heterogeneity and Life-Cycle/Clockspeed Theory

2.2. Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis Systems and Digital Transformation in Policy Innovation

3. Development of a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan

3.1. Public Opinion Data Positioning

- Job-seeking contexts and needs: The practical needs and experiences of women reentering the workforce, their efforts to balance family and work, and the challenges encountered during the job search process.

- Labor market constraints: Discussions related to the demand, opportunities, and limitations in the labor market for women reentering the workforce.

- Job-seeking advice and direction: Suggestions and guidance shared by online users regarding career directions for women returning to work.

- Policy and support systems: Public discussions on the support provided by government and nongovernmental organizations, including opinions and expectations regarding relevant policies, resources, and training programs.

3.2. Public Opinion Data Analysis

3.2.1. Thematic Data Extraction and Filtering

3.2.2. Thematic Data Analysis

3.3. Features and Capabilities of the Public Opinion Database

3.3.1. Web Crawling Technology

3.3.2. Sources of Textual Data

3.3.3. Cluster Analysis

3.4. Public Opinion Computation Models

- Standardization: The relative discussion intensity of different texts and topics across the internet is presented through standardized scores calculated against all texts from the same period.

- Grading: Volume and sentiment indicators are categorized into levels for easier interpretation and clearer implications for policy management.

3.4.1. Attention-Based Model

3.4.2. Sentiment Analysis Model

4. Analyzing Online Discourse on Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan

4.1. Overview of Social Media Discussions

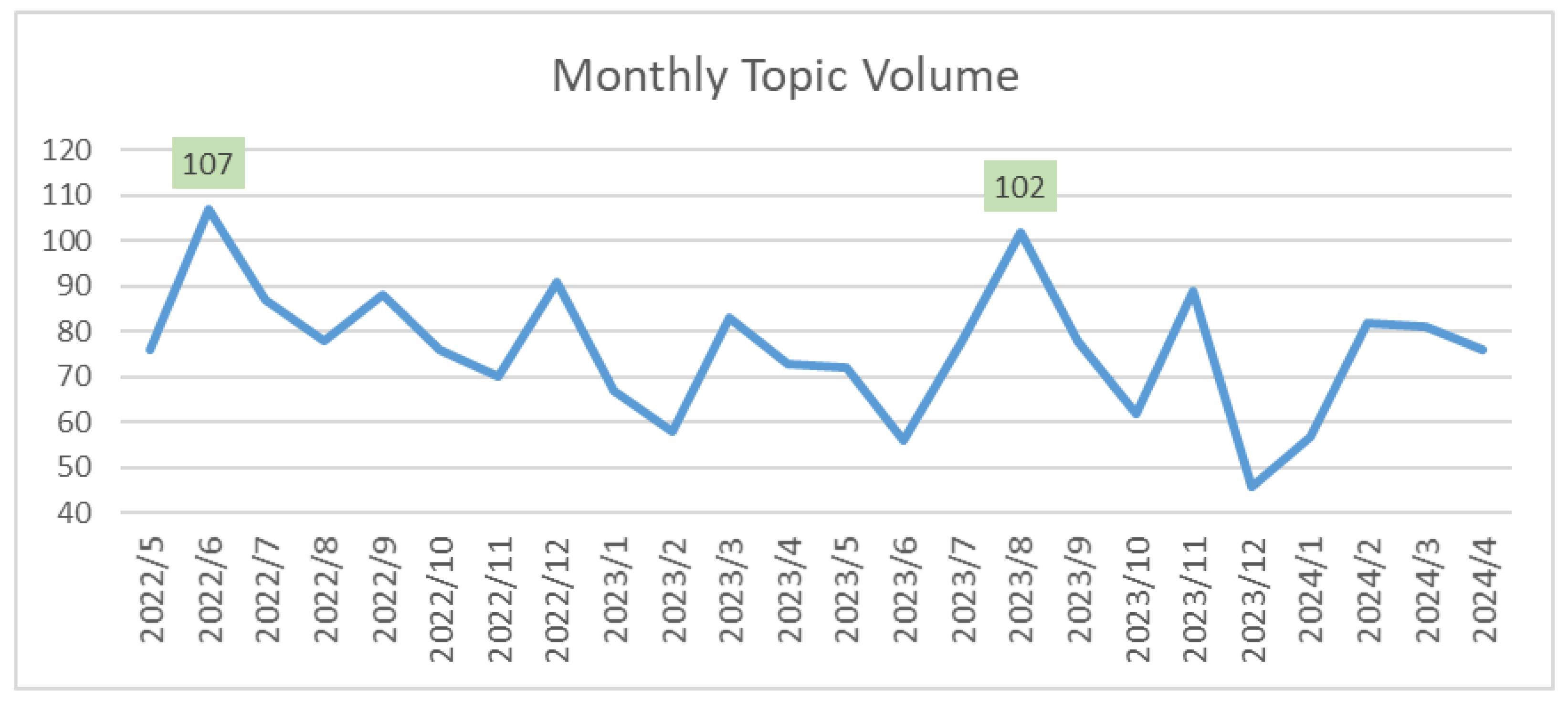

4.2. Volume Analysis of Social Media Discussions

4.3. Framework for Analyzing Social Media Discussions

4.4. Public Opinion Analysis of Women Returning to the Workforce

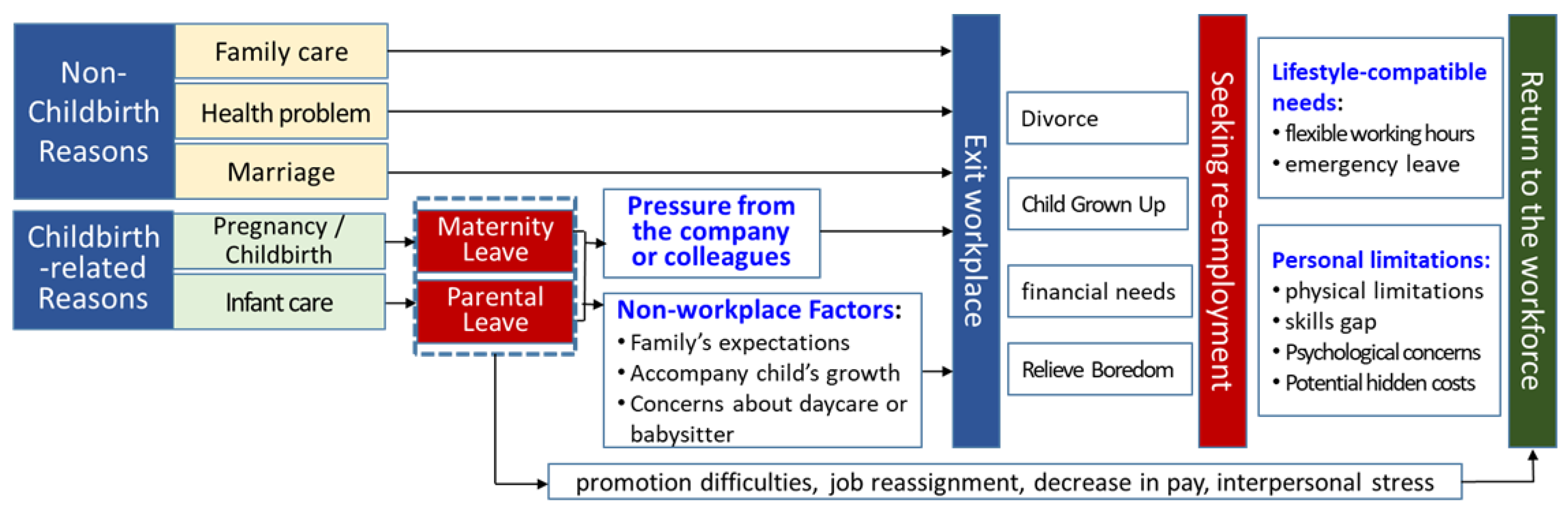

4.4.1. Common Reasons for Women Leaving the Workforce

- (1)

- Non-Childbirth Reasons

- (2)

- Childbirth-Related Reasons

- A.

- Unfriendly Leave Policies

- B.

- Pressure from Companies or Colleagues

- C.

- Decision to Pursue Full-Time Childcare

4.4.2. Challenges Faced by Women Returning to Their Original Workplaces

4.4.3. Motivations of Women Returning to the Workforce

4.4.4. Job-Seeking Situations for Women Returning to the Workforce

- (1)

- Women of Childbearing Age

- A.

- Leaving Work on Time

- B.

- Ability to Take Emergency Leave

- C.

- Flexible Working Hours, Shifts, or Part-Time Options

- D.

- Proximity to Home

- (2)

- Older Women

- A.

- Age and Physical Limitations

- B.

- License and Skill Requirements

- C.

- Psychological Concerns

- D.

- Potential Cost Concerns

4.4.5. The Impact of Family Planning on Job Seeking

4.4.6. Advantages of Women Returning to the Workforce

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Policy Implications

- Economic incentives, which can reduce employer risk and encourage sustained retention.

- Capacity-building initiatives, which enhance women’s skills, adaptability, and self-efficacy.

- Regulatory frameworks, which institutionalize fairness and normalize flexible work arrangements.

5.3. Broader Contributions and Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Responses to Research Questions and Theoretical Contributions

- RQ1: Real-time opinion analysis complements traditional surveys by capturing stigma, self-doubt, and conditional optimism earlier and more dynamically, enabling governments to respond more swiftly with stage-specific interventions.

- RQ2: Differences across demographic groups—flexibility and childcare for younger women versus skill renewal and confidence rebuilding for middle-aged and older returnees—explain both the competency-based view and self-efficacy theory in the context of nonlinear career reentry.

- RQ3: Sectoral variation validates industry life-cycle/clockspeed theory: low-clockspeed sectors absorb returnees more readily, while high-clockspeed sectors exacerbate barriers through rapid skill obsolescence and continuous tenure requirements.

6.2. Summary of Research Findings

- Untapped female labor potential remains significant, yet systemic barriers—such as stigma, inadequate childcare, and inflexible work arrangements—continue to reduce reemployment. This underscores the gap between latent workforce supply and institutional readiness.

- Obstacles intensify with age, generating a structural segmentation between younger women, who demand flexibility and childcare, and middle-aged and older returnees, who emphasize skill renewal and confidence rebuilding. This life-stage divide illustrates how reemployment outcomes vary by competency bundles and efficacy beliefs.

- Institutional and cultural biases reinforce exclusion. Caregiving stereotypes, career-break stigma, and inconsistent parental-leave practices intersect to magnify barriers. These findings demonstrate how discourse-level stigma translates into diminished self-efficacy and constrained labor-market behavior.

- Group-specific needs are pronounced. Younger women seek conditional participation opportunities tied to family support, while middle-aged and older returnees stress re-skilling, signaling, and psychological reinforcement. This aligns with the competency-based and self-efficacy frameworks by showing how resource needs vary across demographic cohorts.

- Industry characteristics shape reemployment pathways. Online narratives point to relatively inclusive reentry in low-clockspeed sectors (care, retail, hospitality) and more rigid exclusion in high-clockspeed industries (technology), validating life-cycle and clockspeed theory.

- Normative demands for fairness and gender role redefinition persist. Across posts, women consistently call for balanced work–family arrangements and the dismantling of stereotypes. This illustrates not only unmet policy needs but also emerging social expectations that governments must address.

- In addition to these empirical insights, a further finding is that DT-enabled monitoring allows policymakers to capture these dynamics in real time, transforming fragmented online discourse into structured signals that can guide stage-specific and sector-sensitive interventions.

6.3. Policy Recommendations

6.4. Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This method involves creating separate sub-databases based on different dimensions, allowing keywords to be added or excluded at any point during the thematic review process. Finally, a comprehensive review is conducted to identify and eliminate irrelevant or noisy themes. The advantage of this approach is that it avoids the need to retrieve the entire dataset again whenever keywords are modified, thus saving time and improving filtering efficiency. |

References

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. 2024 Revision of World Population Prospects; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Committee on Social Development. Demographic Trends and Intergenerational Relations in Asia and the Pacific; Eighth Session; UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Card, D.; Kluve, J.; Weber, A. What works? A meta-analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2018, 16, 894–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Hong, K.J. Factors related to career interruption and re-employment of women in human health and social work activities sector: Comparison with other industry sectors. Nurs. Open 2022, 10, 2656–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, M.; Chen, Q.; Honda, J.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Q. The Role of Structural Fiscal Policy on Female Labor Force Participation in OECD Countries; IMF Working Papers; The International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Volume 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-J. Global trends in promoting female labor force participation and the implications for policy development in Taiwan. Taiwan Labor Q. 2025, 82, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women Viet Nam Country Office. Unpaid Care and Domestic Work: Issues and Suggestions for Viet Nam; UN Women: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charmes, J. The Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. In An Analysis of Time Use Data Based on the Latest World Compilation of Time-Use Surveys; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Impact of Care Responsibilities on Women’s Labour Force Participation; International Labour Organization Statistical Brief; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Altuzarra, A.; Gálvez-Gálvez, C.; González-Flores, A. Economic development and female labour force participation: The case of European Union countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, R.C. Unpaid Care and Domestic Work: Counting the Costs; APEC Policy Support Unit Policy Brief No. 43; APEC Policy Support Unit: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C. Testing for competence rather than for “intelligence”. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, S.M. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Competencies in the 21st century. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Bąk-Grabowska, D. Developing future competencies of people employed in non-standard forms of employment: Employers’ and employees’ perspective. Pers. Rev. 2024, 53, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowska, J.; Lemieszkiewicz-Sosnowska, K. Future-ready workforce: A 2023–2024 literature review of essential skills and competencies for the labor market. Entrep. Educ. 2025, 21, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1997, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepper, S. Industry life cycles. Ind. Corp. Change 1997, 6, 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utterback, J.M.; Abernathy, W.J. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega 1975, 3, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gort, M.; Klepper, S. Time paths in the diffusion of product innovations. Econ. J. 1982, 92, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, L. Imbalances between supply and demand: Recent causes of labour shortages in advanced economies. In ILO Working Paper 115; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, C.; Richardson, J.; Boiarintseva, G. All of work? All of life? Reconceptualising work-life balance for the 21st century. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Spotlight on SDG 8: The Impact of Marriage and Children on Labour Market Participation; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Return to the Labour Market After Parental Leave: A Gender Analysis; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, X.; Wang, J. Women’s career interruptions: An integrative review. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. 2023 Yearbook of Manpower Survey Statistics; Executive Yuan: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024.

- Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. 2024 Report on the Manpower Utilization Survey; Executive Yuan: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024.

- Super, D.E. Vocational development theory: Persons, positions, and processes. In Perspectives on Vocational Development; Whiteley, J.M., Resnikoff, A., Eds.; American Personnel and Guidance Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1972; pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, N.E. Women’s career development. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 253–277. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.D.; Lent, R.W. Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. A Treatise on the Family; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Adamovic, M. When ethnic discrimination in recruitment is likely to occur and how to reduce it: Applying a contingency perspective to review resume studies. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J. Work-life balance: An integrative review. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauner, C.; Wöhrmann, A.M.; Frank, K.; Michel, A. Health and work-life balance across types of work schedules: A latent class analysis. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 81, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, P.; Brooks, R. Caregiving fathers and the negotiation of crossroads: Journeys of continuity and change. Br. J. Sociol. 2023, 74, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarntzen, L.; Derks, B.; van Steenbergen, E.; van der Lippe, T. When work–family guilt becomes a women’s issue: Internalized gender stereotypes predict high guilt in working mothers but low guilt in working fathers. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 62, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J.; Ashforth, B.E. Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijde, C.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. A competence-based and multidimensional operationalization of employability. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giest, S.; McBride, K.; Nikiforova, A.; Sikder, S.K. Digital & data-driven transformations in governance: A landscape review. Data Policy 2025, 7, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.J.; Xu, Y.M. The design of public opinion analysis system based on topic events. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 926–930, 2233–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, L.; Jia, X.; Qi, H.; Yu, S.; Wang, X. Public opinion analysis on novel coronavirus pneumonia and interaction with event evolution in real world. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2021, 8, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y. Iteratively tracking hot topics on public opinion based on parallel intelligence. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2023, 7, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Yu, L. From ChatGPT to Sora: Analyzing public opinions and attitudes on generative artificial intelligence in social media. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 14485–14498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, M.; Li, Z. Sentiment analysis of public opinion on public health events based on deep learning. In Innovative Technologies for Printing, Packaging and Digital Media; Song, H., Xu, M., Yang, L., Zhang, L., Yan, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 1144. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A.; Gupta, M.; Mehmi, S.; Khanna, T.; Chopra, G.; Kaur, R.; Vats, P. Towards intelligent governance: The role of AI in policymaking and decision support for e-governance. In Information Systems for Intelligent Systems; In, C.S., Londhe, N.S., Bhatt, N., Kitsing, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 379. [Google Scholar]

- Masters-Wheele, C. Algorithmic attention systems and writing-as-content. Comput. Compos. 2024, 73, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S. Affective computing: Research advances and future challenges. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 121, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DSIGroup. Po! Internet Public Opinion and Social Media Database; DSIGroup: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-X.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Kao, H.-J. Data collection and analysis of college graduates employment monitoring. J. Labor Occup. Saf. Health 2023, 31, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytic hierarchy process: A new approach to deal with fuzziness in architecture. Archit. Sci. Rev. 1982, 25, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, G.; Güzeller, C.O.; Eser, M.T. The effect of the normalization method used in different sample sizes on the success of artificial neural network model. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2019, 6, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.K.; Kory, J. A review and meta-analysis of multimodal affect detection systems. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2015, 47, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Bajpai, R.; Hussain, A. A review of affective computing: From unimodal analysis to multimodal fusion. Inf. Fusion 2017, 37, 98–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd ed.; HarperCollins College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| Taiwan | Republic of Korea | Singapore | Hong Kong | Japan | United States | Canada | France | German | Italy | United Kingdom | Norway | Denmark | Sweden | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total average | 51.8 | 55.6 | 62.6 | 52.2 | 54.8 | 57.3 | 61.6 | 52.8 | 56.6 | 41.5 | 58.9 | 62.1 | 59.5 | 72.8 |

| Age 15~19 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 15.1 | 7.5 | 22.8 | 37.4 | 51.7 | 16.8 | 28.0 | 5.3 | 42.9 | 59.3 | 53.6 | 44.8 |

| Age 20~24 | 58.4 | 53.4 | 56.5 | 52.0 | 76.6 | 70.1 | 76.9 | 64.7 | 72.0 | 38.0 | 70.5 | 73.3 | 76.5 | 70.2 |

| Age 25~29 | 89.0 | 78.3 | 90.7 | 85.3 | 88.2 | 77.9 | 85.5 | 83.8 | 82.0 | 63.4 | 83.5 | 87.1 | 81.4 | 87.2 |

| Age 30~34 | 88.1 | 73.4 | 90.8 | 81.3 | 82.6 | 78.4 | 85.7 | 83.8 | 81.4 | 70.6 | 83.6 | 85.7 | 81.5 | 88.3 |

| Age 35~39 | 84.4 | 66.5 | 87.9 | 78.1 | 80.1 | 77.6 | 85.2 | 83.3 | 81.9 | 71.4 | 82.4 | 85.9 | 85.8 | 90.7 |

| Age 40~44 | 79.3 | 66.0 | 84.6 | 75.5 | 82.1 | 77.3 | 86.9 | 84.8 | 84.8 | 72.3 | 82.9 | 84.2 | 85.3 | 91.9 |

| Age 45~49 | 77.0 | 68.7 | 82.3 | 73.3 | 83.2 | 77.9 | 85.5 | 86.8 | 86.4 | 72.4 | 84.4 | 82.5 | 86.7 | 93.1 |

| Age 50~54 | 66.3 | 70.3 | 75.5 | 69.1 | 80.7 | 75.2 | 84.1 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 68.2 | 81.0 | 76.8 | 86.5 | 90.5 |

| Age 55~59 | 47.7 | 67.8 | 66.6 | 59.7 | 76.4 | 68.4 | 73.7 | 78.6 | 81.3 | 60.5 | 72.0 | 74.5 | 81.3 | 87.1 |

| Age 60~64 | 28.1 | 55.2 | 55.2 | 37.6 | 65.3 | 52.5 | 52.6 | 41.6 | 63.4 | 37.3 | 51.1 | 66.8 | 62.0 | 70.2 |

| ≥Age 65 | 6.4 | 30.6 | 23.2 | 8.4 | 18.7 | 16.0 | 11.2 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 6.5 | 16.6 |

| Age 15~29 | 57.1 | 51.6 | 60.0 | 54.4 | 64.4 | 63.7 | 72.5 | 54.1 | 62.6 | 35.8 | 67.9 | 73.8 | 71.3 | 67.8 |

| Age15~24 | 35.8 | 33.8 | 36.2 | 31.1 | 51.3 | 55.9 | 65.1 | 40.0 | 51.5 | 21.6 | 58.9 | 66.4 | 65.6 | 57.1 |

| Age 30~44 | 83.5 | 68.5 | 87.7 | 78.1 | 81.6 | 77.8 | 85.9 | 84.0 | 82.7 | 71.5 | 83.0 | 85.3 | 84.1 | 90.2 |

| ≥Age 45 | 36.3 | 52.0 | 52.7 | 40.1 | 45.3 | 45.4 | 46.2 | 40.5 | 45.3 | 34.0 | 45.1 | 46.9 | 45.8 | 65.1 |

| Age 45~64 | 55.1 | 65.5 | 70.3 | 59.9 | 76.9 | 68.2 | 73.4 | 73.0 | 78.4 | 60.0 | 72.5 | 75.4 | 79.4 | 85.6 |

| Date | Topics | Attention Score | Emotion Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 June 2022 | Re: [Mood] If I could live my life again, I wouldn’t have children | 7 | −5 |

| 10 June 2022 | [News] Kaohsiung Restaurant’s “Hiring dishwashing auntie” job Ad suspected of employment discrimination | 7 | 0 |

| 11 June 2022 | [Celebration] My husband says it’s okay even if I don’t work | 7 | −6 |

| 13 June 2022 | Re: [Discussion] Why don’t young people want to get married and have children anymore? | 6 | 8 |

| 4 August 2023 | [Baby] Should I continue using daycare? | 7 | −2 |

| 7 August 2023 | [Question] Helping auntie find employment opportunities for the elders | 6 | 9 |

| 9 August 2023 | [Chat] Will taking parental leave affect my career? | 7 | −5 |

| 17 August 2023 | [Pregnancy] I didn’t feel that the workplace was friendly to pregnant women | 7 | 0 |

| 24 August 2023 | [Baby] Petition to extend parental Leave until the child reaches four years old | 6 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsiao, C.-H.; Lin, K.-J.; Lee, Y.-T.; Lin, S.-T.; Chen, L.-P. Developing a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan: A Digital Transformation Approach to Policy Innovation. Systems 2025, 13, 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110952

Hsiao C-H, Lin K-J, Lee Y-T, Lin S-T, Chen L-P. Developing a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan: A Digital Transformation Approach to Policy Innovation. Systems. 2025; 13(11):952. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110952

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsiao, Chin-Hui, Kuo-Jung Lin, Yu-Ting Lee, Shih-Teng Lin, and Li-Ping Chen. 2025. "Developing a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan: A Digital Transformation Approach to Policy Innovation" Systems 13, no. 11: 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110952

APA StyleHsiao, C.-H., Lin, K.-J., Lee, Y.-T., Lin, S.-T., & Chen, L.-P. (2025). Developing a Real-Time Public Opinion Analysis System for Women’s Reemployment in Taiwan: A Digital Transformation Approach to Policy Innovation. Systems, 13(11), 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13110952