1. Introduction

The ongoing global bifurcation makes global supply chain design critically important [

1]. In configuring their supplier networks, firms face a key trade-off. Global sourcing improves efficiency by accessing more suppliers [

2]. However, geographical dispersion introduces coordination complexity and exposure to risks [

3]. These risks are amplified by heightened external environmental uncertainty [

4].

Existing literature has primarily explored the “why” behind global sourcing. For example, it shows how geopolitical pressures drive firms to find new partner locations [

5,

6]. However, the question of “how” firms implement global supplier network remains underexplored. Internal capabilities enable firms to pursue geographic expansion, particularly in volatile conditions. This study argues that digitalization is one such essential capability. Prior research confirms that digitalization of enterprises strengthens dyadic buyer-supplier relationships. For instance, it helps control partner opportunism [

7]. Yet, it remains unclear whether digitalization enables firms to manage a geographically dispersed network. It is also unclear how external environmental uncertainty influences this process.

To address this gap, our study has two main objectives. First, we investigate how the digitalization of enterprises influences the geographic scope of their global supplier networks. Second, we examine how external environmental uncertainty moderates this relationship. By answering these questions, we shift the focus from why firms globalize to how they achieve it. We also expand digitalization’s role from managing single relationships to designing entire networks.

From the perspective of resource dependence theory (RDT) [

8], firms face internal resource constraints and must engage in external exchanges to acquire critical resources. This requires them to manage their dependence on external resource providers [

9,

10]. In global supply chains, where firms transact with suppliers across the world, the configuration of a global supplier network serves as a key strategic response to such dependency.

Guided by this logic, we argue that the digitalization of enterprises strengthens their ability to manage external dependencies, thereby facilitating the development of a more geographically dispersed global supplier network. This occurs through two main mechanisms. First, improved digitalization helps firms identify and evaluate potential suppliers worldwide with lower search costs and less information asymmetry [

11]. By reducing these traditional barriers, firms gain access to a broader range of viable partners. This alleviates the risks of relying heavily on any single external entity. In effect, digitalization enables firms to build a broader and more diversified dependency portfolio, which helps mitigate power imbalances with individual suppliers [

12].

Second, digitalization enhances a firm’s ability to govern and monitor [

13] a geographically scattered supplier network. It increases supply chain transparency [

14], lowers oversight costs, and accelerates response to disruptions [

15]. By reducing the risks and complexities of managing distant partners, digitalization provides the confidence for firms to manage a wider array of external dependencies across more countries. This strengthened governance turns the theoretical benefits of global sourcing into a manageable reality.

This study empirically examines how digitalization shapes the geographic scope of global supplier networks, using a sample of Chinese listed companies. Our sample selection is guided by three key considerations. First, Chinese firms are deeply embedded in global supply chains and serve as pivotal nodes within them [

16]. Their strategic decisions are therefore critical to understanding the evolution of global production networks. Second, the digitalization of Chinese listed companies remains ongoing and highly heterogeneous. The substantial variation in adoption levels and progress across firms offers rich, natural variation for robust hypothesis testing [

17,

18]. Third, Chinese firms currently operate in an environment marked by significant external uncertainties, such as geopolitical tensions and supply chain disruptions [

19,

20]. This context offers a unique opportunity to examine how digitalization helps firms manage global supplier networks precisely under such challenging conditions.

Using panel data from 2510 Chinese listed companies spanning 2011 to 2023, our analysis confirms a positive relationship between the digitalization of enterprises and the geographic scope of their global suppliers. We further show that this effect is stronger in contexts of higher external environmental uncertainty. A nuanced finding reveals that process-technology-oriented digitalization is the primary driver behind this strategic reconfiguration of supplier networks.

This study proposes a new geographic and network perspective for digital supply chain management. We innovatively demonstrate how digitalization allows firms to design their supplier network’s geographic distribution. This approach moves beyond traditional dyadic relationship management. We also examine how these capabilities enhance strategic resilience amid external uncertainties. This reveals the critical role of digitalization in managing global supply chain risks.

This study makes several key contributions to the literature. First, it shows that digitalization does more than improve dyadic buyer-supplier relationships [

12,

18]; it fundamentally shapes the geographic scope of a firm’s global supplier network. This shifts scholarly attention from operational efficiency at the relationship level to strategic design at the network level. Second, the study conceptualizes the geographic diversification of supplier networks as a distinct strategy for managing external dependencies. While traditional RDT applications focus on structural strategies such as mergers or partnerships [

21,

22], we demonstrate that digitalization offers firms a viable alternative: using geographic dispersion to mitigate dependence and build resilience. Third, in an era of growing geopolitical tensions and supply chain disruptions [

23,

24], this study highlights digitalization as a key mechanism that helps firms balance the classic trade-off between efficiency and security. It shows that digitalization supports sophisticated management of dispersed networks, enabling firms to pursue optimal global supplier configurations even in highly volatile environments.

This paper proceeds in five sequential sections. Following this introduction, we systematically develop our theoretical framework and research hypotheses. Next, we detail the research design, including data sources, variable measurement, and empirical models. We then present and interpret the empirical findings. The final section synthesizes the core contributions, discusses theoretical and practical implications, acknowledges limitations, and proposes directions for further scholarly inquiry.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Resource Dependence and the Global Supplier Network

Rooted in the seminal work of Pfeffer and Salancik [

8], RDT posits a fundamental premise: no organization is self-sufficient. To survive and thrive, firms must obtain essential resources from their external environment [

22], including physical inputs, financial capital, and informational assets, which are not available internally. This necessary reliance on external resources creates interdependence and power asymmetries [

10,

25]. Since the behavior and interests of external actors may not align with those of the focal firm, such dependencies introduce substantial uncertainty and risk [

8]. Therefore, according to RDT, a firm’s core strategic challenge lies in effectively managing and mitigating the constraints and uncertainties that stem from these external resource dependencies [

26,

27].

Suppliers serve as a primary source of external resources [

28,

29], delivering essential raw materials, components, technologies, and services. As a result, the supplier-buyer relationship represents a critical domain for strategic management [

30,

31]. When the resources provided by suppliers are critical and difficult to replace, firms become dependent on them.

Prior research has identified various strategies for managing partner dependence. These approaches can be broadly categorized into two types. The first involves absorbing constraints by adapting and restructuring existing relationships [

32,

33]. For example, firms may establish long-term strategic alliances, exercise control through equity ownership or board interlocks, or pursue vertical integration by acquiring suppliers. The second type focuses on distributing dependence risks through developing alternative relationships [

34]. Rather than relying on a single source, firms can proactively cultivate new partnerships to strengthen supply chain resilience.

While valuable, these traditional strategies primarily address specific, dyadic relationships. They often overlook the broader, network-level perspective through which a firm can design its overall supplier portfolio.

This study examines a distinct, geography-based strategy for managing external dependence in a globalized context. We argue that beyond modifying relationships with individual suppliers, firms can manage dependence by strategically designing the geographic distribution of their supplier network [

35]. This approach is unique in two main aspects. First, it represents a shift from dyadic to network-level management. Instead of focusing solely on individual supplier relationships, firms can view external suppliers as nodes within a global network and manage the configuration of the network as a whole. Second, it introduces a geographic dimension to dependence management. Firms can leverage geographic dispersion to mitigate systemic risks. Suppliers from different countries or regions often offer diverse comparative advantages, allowing firms to access a broader range of heterogeneous resources [

36]. At the same time, maintaining alternative suppliers across different locations enhances resilience against region-specific disruptions, such as geopolitical tensions [

6]. Thus, a geographically dispersed supplier network serves as a key strategic tool for managing external resource dependence and strengthening strategic autonomy.

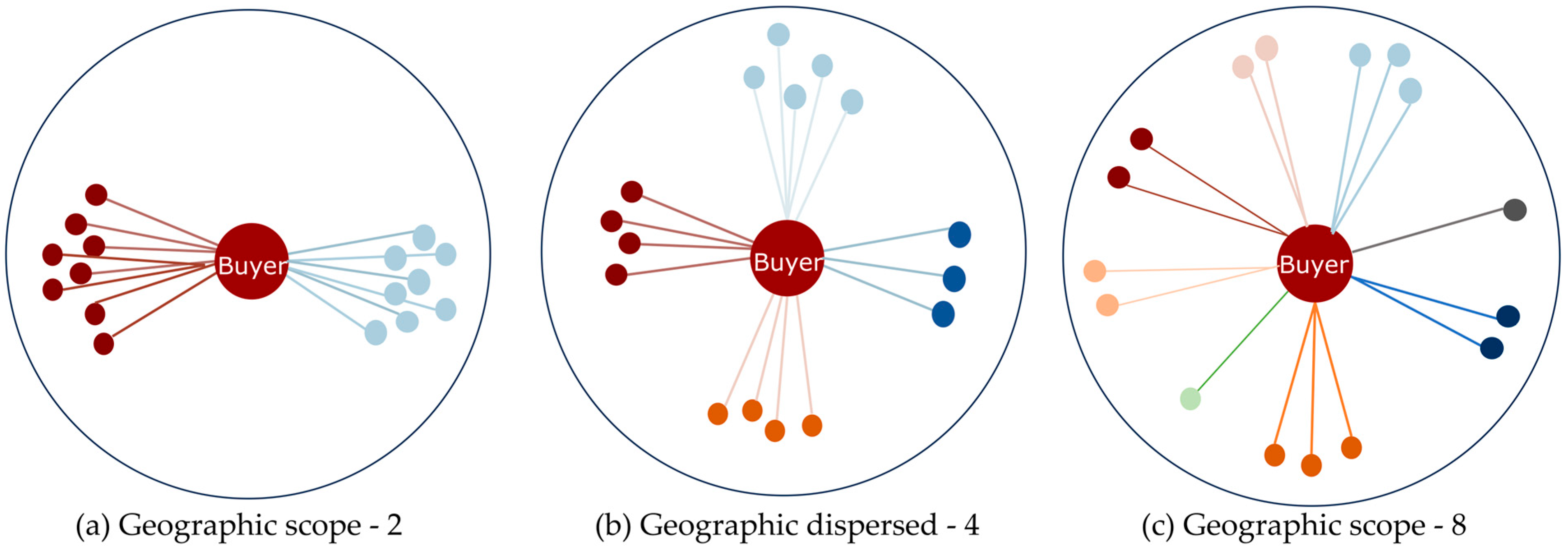

Existing research has extensively examined the motivations for supplier diversification, but has given less attention to the organizational capabilities needed to implement a geographically dispersed strategy. As shown in

Figure 1, where the central node represents the focal firm and surrounding nodes represent suppliers (with colors indicating geographic regions), the progression from panel (a) to (c) illustrates a trend toward greater geographic dispersion.

This expansion, however, raises coordination, monitoring, and governance costs in transnational management. Although geographically complex networks bring clear benefits [

37], a firm’s ability to manage such complexity is critical. This study contends that digitalization serves as a key enabler, allowing firms to effectively govern broader and more complex global supplier networks and thereby supporting expansion into more countries and regions.

2.2. The Impact of Digitalization on Global Supplier Geographic Scope

Digitalization has been defined from multiple perspectives in existing literature. Some studies focus on technology adoption, viewing it as the implementation of digital tools like blockchain, AI, and cloud computing [

38]. Others emphasize business process transformation, considering it as the use of digital technologies to improve efficiency and reshape operations [

13,

39]. Stage models further clarify this concept by differentiating three levels: digitization (converting analog to digital), digitalization (enhancing processes digitally), and digital transformation (fundamentally changing business models) [

40].

Building on these views, this study defines the digitalization of enterprises as their overall capability to acquire, integrate, and use digital technologies. This capability helps firms optimize internal operations and strengthen external collaboration, forming the foundation for managing complex global supplier networks.

Existing research has widely explored how digitalization strengthens dyadic supply chain relationships. Two primary mechanisms explain this effect: improved operational efficiency and enhanced relational governance [

13,

14]. Studies indicate that technologies such as IoT, big data, and blockchain help firms share information more effectively, adjust production plans in a timely manner, and monitor partner behavior with greater accuracy. These improvements contribute to increased supply chain flexibility. Additionally, digitalization has been shown to reduce opportunistic behavior and foster closer collaboration between firms and their established partners [

7,

31].

However, this predominant focus on dyadic relationships has overlooked a key strategic aspect: how digitalization shapes the macro-configuration of entire supplier networks. While prior research effectively shows how digitalization optimizes existing one-to-one relationships, it rarely examines how it enables firms to strategically redesign their one-to-many network architecture. We argue that the strategic value of digitalization lies not only in optimizing operations, but also in empowering firms to reshape their global footprint. This capability allows firms to better manage external dependencies through structural reconfiguration rather than relational adjustment alone.

The impact of digitalization on the geographic distribution of global suppliers operates through two key mechanisms. First, digitalization enhances a firm’s ability to identify and connect with suitable resource providers worldwide [

41]. While firms may theoretically seek optimal suppliers globally, this requires effective search capabilities. Digital tools enable firms to locate and engage more distant partners. For example, using big data analytics and AI-driven procurement platforms, firms can efficiently identify, evaluate, and authenticate potential suppliers across borders, overcoming traditional geographic constraints. By setting parameters for cost, technical capability, and quality, firms can achieve optimal matches and build more geographically dispersed supplier networks. Thus, digitalization reduces information asymmetry [

11] and expands the firm’s ability to establish supply relationships across broader geographic areas.

Second, digitalization strengthens a firm’s ability to manage geographically dispersed resource dependencies. Establishing a global supplier network exposes firms to more complex environments, requiring adaptation to diverse geographic and institutional contexts [

42]. Digitalization helps reduce the costs of coordinating geographically scattered suppliers. For example, digital collaboration platforms [

43] standardize communication processes between upstream and downstream partners, enabling efficient daily coordination across regions. Moreover, digital technologies enhance supply chain transparency [

14]. Technologies such as IoT, ERP, and blockchain enable real-time visibility into order status, inventory levels, and logistics trajectories, effectively overcoming the supervisory challenges posed by distance. Finally, digital tools help firms respond better to region-specific risks. Predictive analytics and monitoring systems can identify potential disruptions, offering early warnings to support global supplier decision-making [

44].

In summary, digitalization enhances a firm’s capacity to establish more advantageous resource dependencies while simultaneously improving its ability to manage complex, long-distance dependencies. This means it enables firms to operate geographically dispersed global supplier networks more effectively, encouraging expansion into wider geographic regions. Hence, we hypothesize:

H1. The digitalization of enterprises is positively associated with the geographic scope of their global supplier networks.

2.3. The Moderating Role of External Environmental Uncertainty

The preceding arguments establish that digitalization empowers firms to manage the complexities of a geographically dispersed supplier network. Building on this foundation, we introduce a crucial contingency: external environmental uncertainty. We contend that the strategic value of digitalization in enabling global sourcing becomes more evident under high volatility.

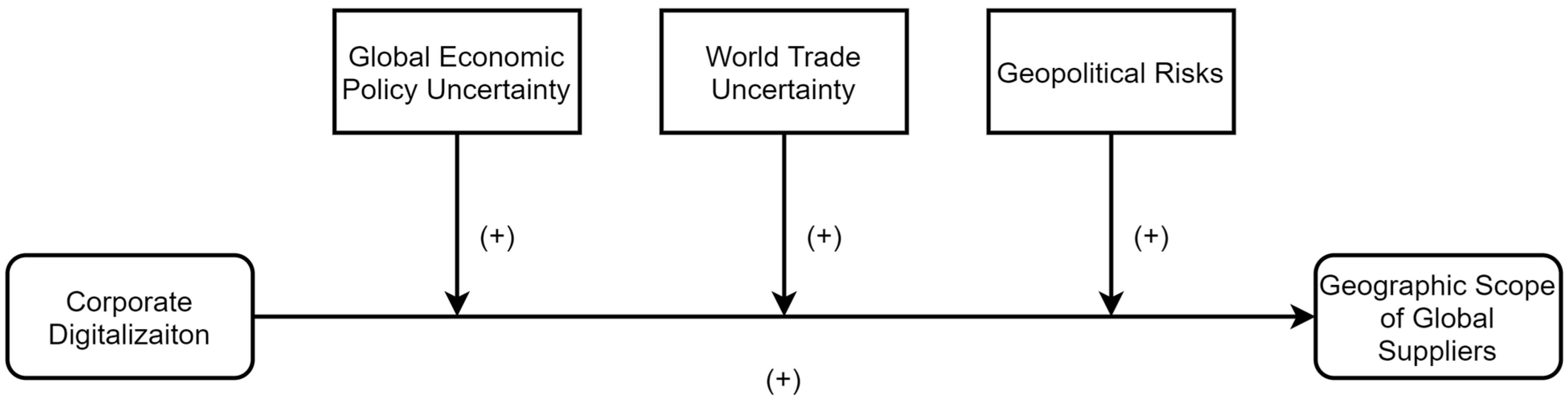

Accordingly, we examine three salient types of uncertainty: global economic policy uncertainty, world trade uncertainty, and geopolitical risk. We propose that each of these factors strengthens the relationship between digitalization and supplier geographic dispersion by enhancing the value of digital capabilities.

As shown in

Table 1, these three dimensions of uncertainty operate through distinct mechanisms. Economic policy uncertainty affects operational costs through policy-induced volatility [

45,

46]. World trade uncertainty influences market access through disruptions in trade flows [

4]. Geopolitical risk threatens supply continuity via physical and political disruptions [

24,

47]. Together, these interrelated dimensions illustrate how digitalization becomes especially vital in helping firms navigate uncertain external environments.

2.3.1. Global Economic Policy Uncertainty

Global economic policy uncertainty (GEPU) refers to ambiguities in future fiscal, regulatory, and monetary policies across major economies [

45,

48]. This uncertainty can suddenly reduce the efficiency of established supply routes. In such an environment, characterized by unpredictable tax regimes and volatile exchange rates, the ability to digitally search for and evaluate a broad range of suppliers becomes crucial.

Firms can use data analytics to continuously scan for suppliers in countries with more stable policies and shift sourcing accordingly. This digital agility allows them to treat their global supplier network as a dynamic portfolio, strategically reducing dependence on regions with high policy volatility [

4,

51]. As a result, the value of digital search capabilities increases significantly when firms face frequent policy shocks.

Furthermore, heightened economic policy uncertainty amplifies the value of digital governance mechanisms in managing global supplier relationships. While digital search helps identify alternative suppliers, effective coordination becomes crucial when policies become volatile. Digitalization facilitates real-time information sharing [

52] and collaborative planning with suppliers [

53] across different jurisdictions. This allows firms to quickly adjust production schedules and inventory management in response to policy changes. Such coordination ensures that geographic dispersion does not become a disadvantage during periods of policy instability. Hence, we hypothesize:

H2. Global economic policy uncertainty positively moderates the relationship between digitalization and the geographic scope of global suppliers, strengthening this relationship when GEPU is higher.

2.3.2. World Trade Uncertainty

World Trade Uncertainty (WTU) refers to volatility in international trade flows caused by tariff changes, shipping disruptions, and evolving trade policies [

20,

50]. Strategically, such uncertainty can directly disrupt established buyer-supplier relationships. For example, new trade policies may force firms to cut existing international supply links and consider reshoring production [

4,

54].

In response, firms often turn to strategies such as friendshoring to balance efficiency and security [

6]. In this context, digitalization plays a critical role. They help firms efficiently identify, evaluate, and match with suitable suppliers in new regions, while also assessing local trade policies and potential risks. When WTU is low, firms have little incentive to expand their supplier networks geographically, as disruption risks remain limited. However, as WTU increases, the motivation to use digital tools for supplier diversification grows significantly.

At the operational level, WTU can disrupt the cross-border flow of information, goods, and capital. This increases the complexity of managing a geographically dispersed supplier network. In such situations, digital technologies become vital tools for maintaining coordination and operational continuity [

31,

55]. For example, cloud-based platforms and IoT-enabled systems help firms sustain real-time communication and collaborative planning with suppliers across regions. These tools facilitate logistics rerouting, production adjustments, and delay mitigation, without requiring firms to reshore operations or reduce geographic presence.

Therefore, under high WTU, digitalization delivers a dual benefit: it enables strategic reconfiguration of the supplier network while strengthening operational resilience. We thus hypothesize:

H3. World trade uncertainty positively moderates the relationship between digitalization and the geographic scope of global suppliers, such that the relationship is stronger when WTU is higher.

2.3.3. Geopolitical Risk

Geopolitical risk (GPR) refers to the potential for international conflicts, diplomatic tensions, or territorial disputes to disrupt global economic activities [

24,

47]. Unlike other forms of uncertainty, GPR often entails direct governmental intervention, mandatory decoupling policies, or even complete severance of supply relationships between specific countries.

In this context, firms face strong pressure to geographically diversify their supplier base away from high-risk regions. Digital capabilities become crucial in enabling firms to rapidly identify, evaluate, and qualify alternative suppliers in politically stable regions [

56]. When GPR is low, firms may lack sufficient motivation to expand their global supplier network. However, as GPR intensifies to moderate levels, the strategic value of digital search and matching capabilities grows significantly. In such cases, geographic dispersion becomes a vital risk mitigation strategy, rather than simply a means to improve efficiency [

57].

Furthermore, digitalization help maintain operational continuity during geopolitical disruptions. Tools such as cloud-based collaboration platforms, encrypted communication systems, and blockchain-enabled tracking [

58,

59] allow firms to sustain real-time coordination with globally dispersed suppliers, even when political tensions restrict traditional communication channels. This digital connectivity ensures that geographic diversification does not compromise coordination efficiency. As a result, firms can effectively respond to geopolitical disruptions without having to localize their supply chains entirely.

However, digitalization may not be effective under all levels of geopolitical risk. In extreme cases, such as economic sanctions [

60] or war, digital capabilities can be overridden. Governments may force companies to decouple their supply chains. In these situations, firms must restructure regardless of their digital strength. This means that at very high levels of GPR, the effect of digitalization may be attenuated as its role is superseded by political mandates. We therefore suggest a more precise view: GPR strengthens the link between digitalization and geographic dispersion only up to a point. Beyond that point, the effect may fade. Thus, we hypothesize:

H4. Geopolitical Risk positively moderates the relationship between digitalization and the geographic scope of global suppliers within moderate ranges of GPR; however, this moderating effect may attenuate under high GPR conditions.

In summary, the three types of uncertainty examined—GEPU, WTU, and GPR—each strengthen the value of digitalization. This makes the creation and management of a globally dispersed supplier network both more feasible and strategically necessary. The overall conceptual framework of this study is shown in

Figure 2.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the key variables. On average, the firms in our sample maintain suppliers in 1.94 countries. The digitalization index shoes considerable variation, with values ranging from 21.98 to 64.95, indicating substantial heterogeneity in digital maturity across firms. The three moderating variables—GEPU, WTU, and GPR—have minimum values of zero. By construction, these values correspond to firms that source exclusively from domestic suppliers and therefore have no exposure to international uncertainty.

Table 3 reports the correlation matrix. As expected, GEPU and GPR show a relatively high correlation, consistent with the frequent co-occurrence of geopolitical risks and economic policy uncertainty. However, since these variables are included into separate regression models, this correlation does not raise multicollinearity concerns in our estimations. To mitigate concerns regarding multicollinearity, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The maximum VIF observed in our models is below 7, and the mean VIF is 2.12. As all values are well below the conventional threshold of 10, multicollinearity does not significantly affect our results.

4.1. Main Effects of Digitalization

Table 4 presents the baseline regression results examining the relationship between digitalization and supplier geographic scope. Column (1) reports a positive and statistically significant coefficient for digitalization alone (coef. = 0.0251,

p < 0.01), providing initial support for Hypothesis 1.

Column (2) introduces control variables to strengthen the model specification. Column (3) adds year fixed effects to control for common temporal shocks. Column (4) includes both firm and year fixed effects, representing our most rigorous specification that accounts for unobserved time-invariant firm characteristics and aggregate time trends.

The digitalization coefficient remains positive and statistically significant across all specifications, demonstrating robust support for Hypothesis 1. This consistent pattern confirms that greater digitalization is associated with wider geographic dispersion of suppliers.

The model’s explanatory power shows a notable progression. The Adjusted R2 increases substantially from 0.0810 in Column (3) to 0.6849 in Column (4). This significant improvement occurs because the firm fixed effects effectively account for time-invariant firm characteristics that shape supplier network decisions. These characteristics encompass a range of inherent organizational traits such as corporate culture and management philosophy. Such traits systematically influence how firms configure their global supply base.

Regarding the control variables, the results reveal several notable patterns consistent with theoretical expectations. The significantly negative coefficient for state ownership indicates that state-owned enterprises tend to maintain more geographically concentrated supplier networks. This aligns with the view that SOEs often prioritize domestic supply chain security and are more deeply embedded in local institutional environments, reducing their incentive for global diversification. In contrast, firm size shows a positive and significant relationship with geographic dispersion. This suggests that larger firms, with their greater resources and organizational capabilities, are better equipped to manage the complexities of extensive global supplier networks.

4.2. Analysis of Endogeneity Issues

We address potential endogeneity concerns through three identification strategies: first, we employ an instrumental variable approach to mitigate reverse causality; second, we include additional control variables to alleviate omitted variable bias; and third, we implement propensity score matching to account for sample selection bias.

4.2.1. Instrumental Variable Approach

This section addresses potential endogeneity concerns, particularly reverse causality. One possible issue is that firms with more globally dispersed supplier networks might have greater opportunities to develop digital capabilities. To mitigate this concern, we employ two identification strategies.

First, we lag all independent and control variables by one period to reduce simultaneity bias. As shown in Column (1) of

Table 5, the coefficient on the lagged digitalization variable remains positive and statistically significant, consistent with our baseline results.

Second, we use an instrumental variable (IV) approach to strengthen causal inference. We construct two instruments to address potential endogeneity. The first instrument is the one-period lagged digitalization measure (digitalization_1). The second instrument, IV_distance*city, draws on Babina et al. [

75], who argue that access to digital talent drives digital capability development. We calculate the geographic distance between a firm’s headquarters and top-tier Chinese science and engineering universities, identified through official disciplinary assessments. This distance is then multiplied by the number of other firms in the same city.

The logic is that greater distance from talent sources, combined with stronger local competition for skilled workers, limits a firm’s ability to hire digital specialists. This constraint negatively correlates with the firm’s digitalization level.

The IV_distance*city instrument satisfies the exclusion restriction due to the exogenous nature of its components and their theorized channel of influence. The spatial distribution of universities is historically predetermined and unrelated to contemporary firm decisions, while city-wide firm count reflects general economic activity rather than supply chain-specific factors. Although these geographic and economic conditions might indirectly correlate with firm performance, their primary theoretical pathway to influencing supplier geographic dispersion is through constraining digital talent supply. It is this developed digitalization, not the instrument itself, that directly enables firms to identify, manage, and coordinate with geographically dispersed suppliers.

The IV estimation results appear in Columns (2) and (3) of

Table 5. The first-stage results in Column (2) show a statistically significant positive relationship between lagged digitalization and current digitalization, and a significant negative relationship between IV_distance*city and digitalization. Both findings align with theoretical expectations. In the second stage (Column 3), the instrumented digitalization measure continues to show a positive and significant effect on the geographic scope of global suppliers. This supports our main hypothesis.

Post-estimation tests confirm the strength of our instruments. The Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic (p = 0.0000) rejects under identification, and the Wald F statistic of 337.062—well above the 10% Stock-Yogo critical value of 19.93—rules out weak instrument concerns. The nonsignificant Hansen J statistic (p = 0.2159) supports the validity of the overidentifying restrictions.

Together, these results validate the strength and exogeneity of our instruments. They provide credible evidence that digitalization promotes geographic dispersion in global supplier networks.

4.2.2. Controlling for Omitted Variables

We perform two robustness checks to address potential omitted variable bias. First, we introduce additional control variables that could affect global sourcing strategies. Specifically, we account for a firm’s innovation intensity and financial health, as these factors may directly influence its capacity to reconfigure global supplier networks. These include a firm’s innovation intensity, measured as R&D expenditure divided by operating revenue, and its financial constraints, captured by the Kaplan–Zingales (KZ) index. Firms with greater R&D commitment may possess stronger technological capabilities that facilitate managing dispersed partners, while financially constrained firms likely face greater challenges in undertaking the upfront investments required for global supply chain expansion. After including these controls, the digitalization coefficient remains positive and statistically significant, as shown in Column (4) of

Table 5.

Second, we include both industry and province fixed effects. This approach controls for unobserved factors related to a firm’s industry and regional context. Industry needs determine the strategic imperative for geographic dispersion, while regional conditions determine its practical feasibility. This interaction between sectoral requirements and locational constraints collectively shapes firms’ supplier configuration decisions. As Column (5) of

Table 5 shows, the positive relationship between digitalization and supplier geographic dispersion remains significant, confirming our main finding.

Across both tests, the digitalization coefficient shows remarkable stability in both magnitude and statistical significance. This consistency reinforces our main finding that digitalization promotes geographic dispersion of suppliers, while demonstrating the robustness of this relationship to alternative model specifications.

4.2.3. Propensity Score Matching Analysis

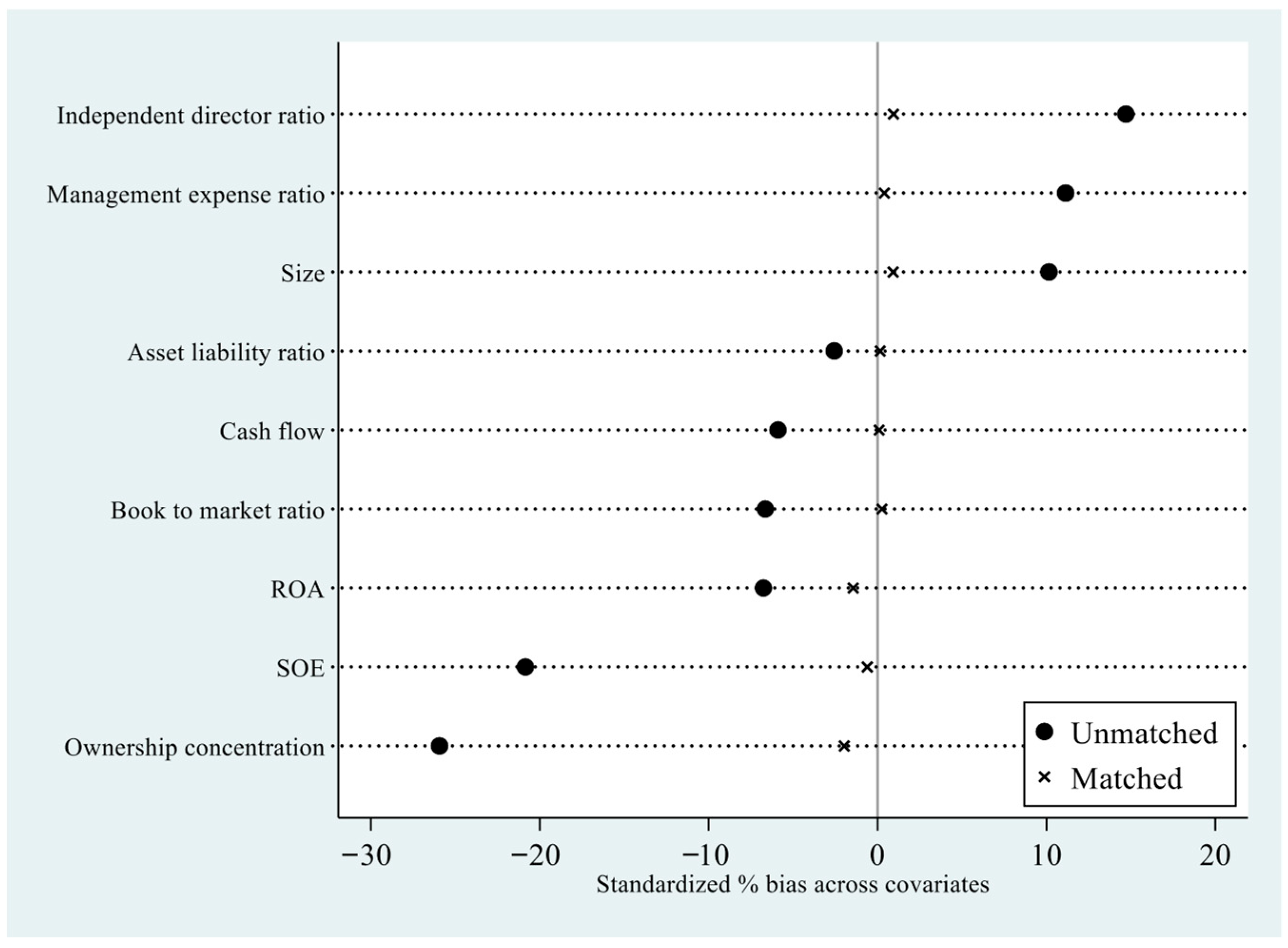

We address potential sample selection bias using Propensity Score Matching (PSM). Firms with above-median digitalization form the treatment group; those below-median form the control group. We estimate propensity scores through kernel matching, using our core control variables. The matching variables include state ownership, firm size, profitability, leverage, management expense ratio, growth opportunities, corporate governance, ownership concentration, and cash flow. These variables capture the key firm characteristics that may jointly influence digitalization adoption and global supplier configuration.

We rigorously assess matching quality through multiple balance checks. Multiple tests verify the matching quality. As

Figure 3 shows, standardized differences for all covariates are below 2% after matching.

t-tests in

Table 6 show no significant inter-group differences. The Pseudo R

2 decreases to 0.000, and the joint significance test yields an insignificant result (

p = 0.949). We re-estimate our model on this matched sample. As Column (6) of

Table 5 shows, the effect of digitalization remains positive and statistically significant. This confirms our main finding is robust to sample selection concerns.

4.3. Robustness of the Main Findings

We perform a series of robustness checks to validate our main findings. These tests use different model specifications, variable measurements, and sample compositions. Results appear in

Table 7.

First, we estimate a Poisson model. This approach better suits the count-based nature of our dependent variable. As Column (1) shows, the digitalization effect remains positive and significant. This confirms our finding is robust to the choice of model.

Second, we test an alternative measure of digitalization. This check addresses potential measurement bias. We follow Wu et al. [

76], and create a new index based on digital-related terms textual analysis in annual reports. As Column (2) shows, the positive effect remains significant. This confirms our result is not tied to one specific measurement method.

Third, we employ three alternative measures of supplier geographic scope.

The first measure is the entropy-based geographic dispersion index. Following established methodology [

77], we calculate this index as:

where

represents the proportion of a firm’s suppliers located in country

. This metric captures the uniformity of supplier distribution across locations. A higher value indicates greater dispersion. Results in Column 3 of

Table 7 remain consistent with our main findings.

The second measure is the inverse HHI. We compute this measure as:

where

again denotes the proportion of suppliers in country

. This metric reflects the degree of dispersion across countries. The result, shown in Column 4 of

Table 7, continues to support our hypothesis.

The third measure is the total geographic distance. This measure sums the distances from China to each country where the firm maintains suppliers. It directly captures the spatial spread of the supplier network. As shown in Column 5 of

Table 7, the significant positive effect persists, confirming the robustness of our findings across different dispersion metrics.

Finally, we test our results using different sample compositions. In Column (6), we remove firms with suppliers in only one country. This ensures our findings are not driven by firms with no geographic variation in their supply base. In Column (7), we exclude firms in the financial industry and the computer, communication, and other electronic equipment manufacturing sector. Financial firms often follow different location strategies, while tech firms typically have different digitalization patterns. Removing them addresses this concern. In Column (8), we drop post-2019 data. This reduces potential bias from COVID-19 impacts on global supply chains.

Across all these samples, digitalization maintains a positive and significant link with supplier dispersion. This confirms our finding holds under various sample conditions.

4.4. The Moderating Role of External Uncertainty

This section presents the empirical tests for Hypotheses 2–4, which posit that external environmental uncertainty amplifies the positive effect of digitalization. The regression results are reported in

Table 8.

Table 8 presents the moderating effect estimates for GEPU, WTU, and GPR in columns (1) through (3), respectively. Across all three models, the interaction terms between digitalization and uncertainty measures are positive and statistically significant. This consistent pattern strongly supports our hypotheses, indicating that the positive effect of digitalization on supplier geographic dispersion intensifies under heightened external uncertainty. These findings align with our theoretical argument: digitalization becomes particularly valuable for managing external resource dependencies when firms operate in volatile and unpredictable environments.

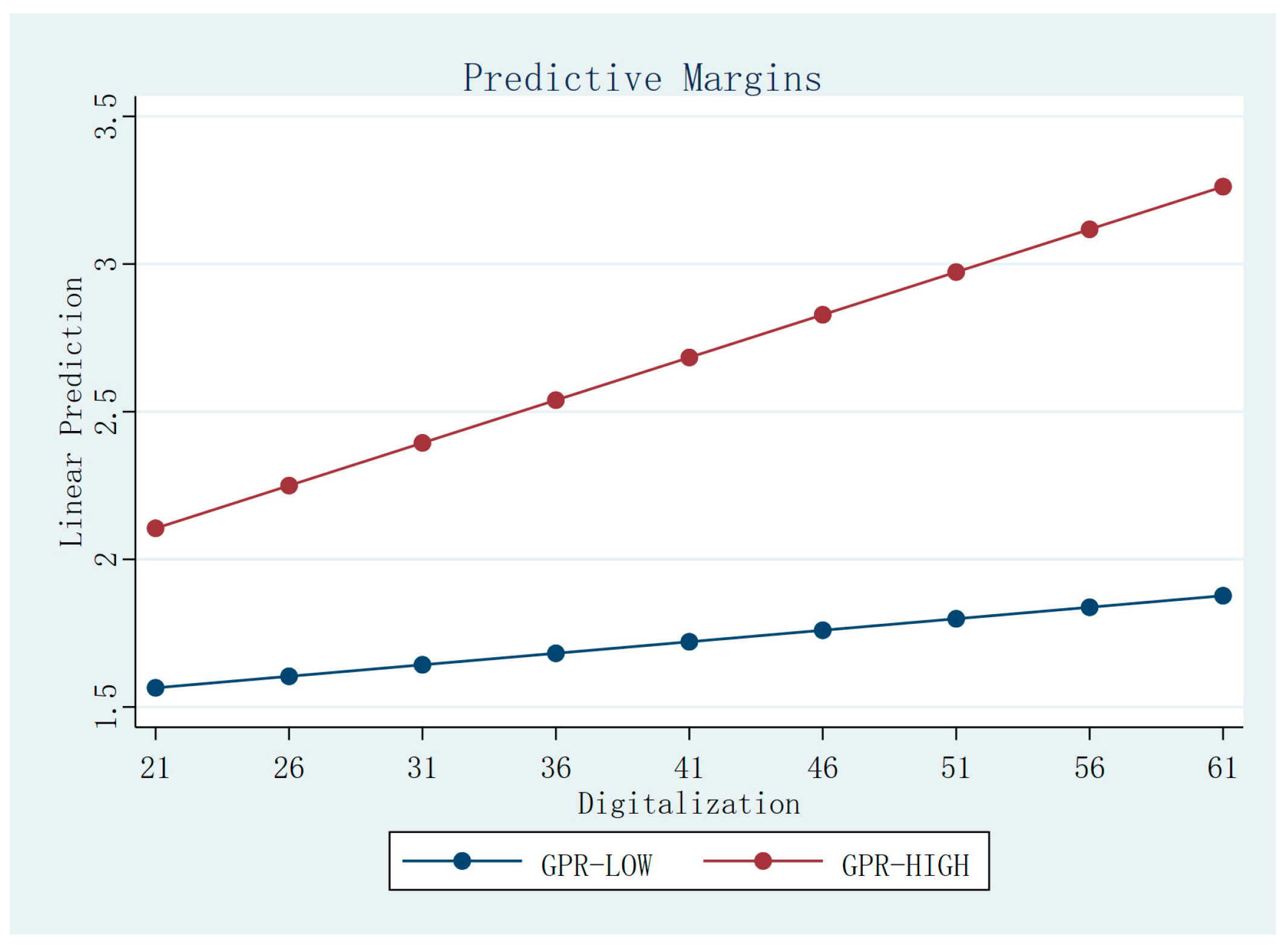

To further examine the moderating role of GPR, we split the sample into two periods based on its intensity. As shown in Columns (4) and (5), the average GPR index is significantly lower in 2011–2018 than in 2019–2023. The moderating effect of GPR is positive and significant in the earlier period (Column 4), but becomes insignificant in the later period (Column 5). This divergence supports a more nuanced view: the enabling role of digitalization is effective within a certain range of GPR, yet may diminish when geopolitical risk escalates to higher levels.

To help interpret these interaction effects, we plot the predictive margins in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. In these figures, the red line shows the relationship between digitalization and supplier dispersion under high environmental uncertainty, while the blue line shows the relationship under low uncertainty.

A clear pattern emerges across all three figures: the red line has a noticeably steeper slope than the blue line. This visual evidence confirms that the effect of digitalization on geographic dispersion is stronger when uncertainty is high. These graphs provide intuitive support for the moderating role of external uncertainty.

4.5. Extending the Research: Dimensions of Digitalization and Directions of Expansion

4.5.1. Heterogeneous Effects Across Digitalization Dimensions

Our study proposes that digitalization promotes global supplier dispersion by enhancing a firm’s ability to manage external resource dependencies. To examine this mechanism, we analyze three distinct dimensions of digital application captured in a composite index: (1) Process innovation, reflected in automated workflows such as smart manufacturing; (2) Technological innovation, involving the adoption of foundational technologies such as 5G and digital twins; (3) Business model innovation, manifested through digital-driven products, services, or value propositions.

These indices are constructed using data from the CSMAR database, which calculates the frequency of relevant keywords in corporate annual reports. Example keywords include “digital twin” and “5G” for technological innovation, “smart manufacturing” for process innovation, and “smart healthcare” for business model innovation. We hypothesize that among these dimensions, supplier search and governance capabilities are most directly enhanced through innovations in process and technology.

The empirical results in

Table 9 reveal an informative pattern. While process innovation demonstrates a significant positive effect on geographic scope, technological and business model innovations show statistically insignificant impacts when examined separately. However, the combined effect of technological and process innovation emerges as positive and significant. The significance of process innovation, particularly when coupled with technological infrastructure, aligns with its direct role in revolutionizing supply chain operations.

Digitized processes, such as automated supplier screening and integrated logistics platforms, directly lower the costs and complexities of identifying potential suppliers across regions and managing ongoing relationships across distances. Technologies like cloud computing and big data analytics provide the essential infrastructure that enables these process improvements, creating a synergistic effect that makes global supplier networks operationally feasible and economically viable.

In contrast, the non-significance of business model innovation reinforces that the mechanism operates primarily through operational efficiencies rather than strategic repositioning. Business model innovation may redefine how a firm creates value but does not inherently provide the operational tools needed to identify and manage suppliers across diverse geographic locations. While potentially transformative in other strategic dimensions, these innovations lack the direct operational linkage required to overcome the tangible challenges of managing physical distance and coordinating across global supply bases.

4.5.2. Geographic Composition of the Supplier Network

Our main analysis shows that digitalization broadens the overall geographic scope of supplier networks. This subsection examines where that expansion occurs. We use the CEPII geographic classification to analyze supplier distribution across five regions: Africa, Asia, Europe, America, and the Pacific. Results in

Table 8 (Columns 5–9) show a clear pattern. Digitalization significantly increases supplier counts in Asia, Europe, and America. It does not significantly affect counts in Africa or the Pacific.

This pattern refines our main hypothesis. Asia, Europe, and America represent the world’s most established manufacturing and consumer markets. Entering these regions demands advanced digital capabilities. Firms must navigate complex ecosystems, meet high standards, and manage sophisticated logistics. In contrast, Africa and the Pacific often present different sourcing opportunities such as resource extraction and lower-cost labor. In such contexts, the specific search and coordination capabilities enhanced by digitalization are less critical. Overall, digitalization helps firms build presence in complex, established markets rather than uniformly scattering suppliers worldwide.

5. Discussion

This study examines how corporate digitalization influences the geographic scope of firms’ global supplier networks. While RDT has traditionally emphasized structural responses like merges and joint ventures to manage dependencies [

10], our findings reveal digitalization as a fundamentally different type of organizational capability. This study shifts the theoretical focus from structural solutions to include operational capabilities as core means of dependence management.

Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies strongly supports this view. We find digitalization significantly expands supplier network geographic scope, with this relationship being systematically moderated by external uncertainty. Specifically, when economic policy uncertainty, trade uncertainty, or geopolitical risk increases, firms demonstrate stronger motivation to manage their supplier relationships through digital means. This finding connects two distinct types of dependence in RDT, demonstrating how environmental dependence directly strengthens partner dependence management.

Our analysis further reveals that process and technological innovations drive this geographic expansion. This suggests digital capabilities prove most valuable in core operational activities that underpin supplier management.

Finally, we introduce a network-level perspective to dependence management. While traditional RDT research typically examines single dyadic relationships, our findings show firms can manage their entire supplier portfolio as an integrated system. By strategically configuring the geographic composition of their supplier network—particularly through expansion into established markets like Asia, Europe, and America—firms gain more effective control over their external dependencies. This redefines the unit of analysis in dependence management from individual relationships to the overall network structure.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study makes several key theoretical contributions that extend the boundaries of RDT, supply chain management, and digitalization literature.

First, our findings advance resource dependence theory by revealing a new strategic approach to dependency management [

8]. While traditional RDT applications in supply chains emphasize dyadic relationships [

10,

78], we demonstrate how digitalization enables firms to manage dependencies through supplier network architecture. Specifically, we conceptualize the geographic scope of a firm’s entire supplier network as a proactive mechanism for managing external dependence. Our empirical results confirm that digitalization helps firms disperse suppliers across multiple countries. We also find that external uncertainty strengthens this motivation, thereby linking environmental dependence with partner dependence in RDT. Together, these insights provide a more systemic understanding of how modern firms manage dependencies through digital capabilities.

Second, our study shifts the focus of global supplier network research from consequences to antecedents. While existing work extensively documents outcomes—such as effects on innovation and performance [

37,

64]—less is known about the capabilities that enable firms to configure these networks in the first place. We identify digitalization as a key enabler, demonstrating its role through a dual mechanism: it reduces the costs and information barriers of global supplier search, while simultaneously enhancing the firm’s ability to manage dispersed networks by lowering coordination and monitoring costs. In this way, we reframe digitalization not as a mere optimization tool, but as a foundational capability that unlocks the strategic option of geographic dispersion.

Third, our study broadens the understanding of digitalization. While prior research has compellingly demonstrated how digitalization improves internal outcomes such as innovation and ESG performance [

79], and enhances bilateral supply chain relationships [

7], we extend this perspective to a macro-strategic level. Specifically, we show that digitalization enables firms to expand the geographic scope of their overall supplier network and this effect intensifies under uncertain conditions. This finding reveals a more strategic and systemic role for digitalization: it empowers firms not merely to operate efficiently within existing networks, but to proactively reconfigure their global resource dependence landscape.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings provide practical guidance for managers.

First, digitalization is a key investment for global supply chain development. Firms seeking global expansion can use digital tools to find and connect with suitable suppliers worldwide. This helps them build strategic supplier networks beyond geographic limits. For firms already in global networks, digitalization improves transparency and coordination across their supplier base [

7,

80]. This turns a widespread network from a challenge into a manageable advantage.

Second, managers should adopt a network-level perspective in supply chain design. While individual supplier relationships are important, executives must also consider the overall architecture of their supplier network [

28,

37]. Our findings show that building a geographically diversified network helps reduce concentration risk and decreases over-reliance on specific regions or suppliers. This approach strengthens a firm’s strategic independence.

Finally, digitalization offers a way to manage uncertainty. As geopolitical tensions and supply chain disruptions increase, firms are turning to strategies like friend-shoring and diversification [

6]. These transitions can be costly. However, our research shows that digitalization helps reduce these costs. Developing digital capabilities is therefore not just about operational improvement but also a strategic necessity. It allows firms to adapt their global supplier networks with greater agility and confidence in a volatile environment.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest valuable directions for future research.

First, our sample focuses on Chinese listed companies. While important in global supply chains, their strategic choices may not represent all firms. Companies in developed markets or those less globalized may show different patterns due to varying institutional environments. Future studies could examine firms from different countries to build a more universal theory.

Second, our data may not capture all supplier relationships. Although we focus on geographic distribution, this could still affect results. Future research could use detailed case studies of firms that fully disclose their supplier lists to better understand network structures.

Third, our analysis is largely static. We study the scope of supplier networks but not how they change over time. Future work could use longitudinal or case methods to trace how firms actually build their global networks, including the sequence, timing, and reasons behind each expansion step. This would shed light on the real strategic choices firms face.

In summary, this study shows how digitalization helps firms expand their global supplier networks. Theoretically, it extends resource dependence theory by highlighting network-level strategies; advances supply chain research by identifying digitalization as a key driver; and broadens digitalization studies by showing its role in shaping global networks. For managers, it offers guidance on using digitalization to build resilient supply chains in an uncertain world.