Systems Thinking and Human Resource Management in Healthcare: A Scoping Review of Core Applications Across Health System Levels

Abstract

1. Background

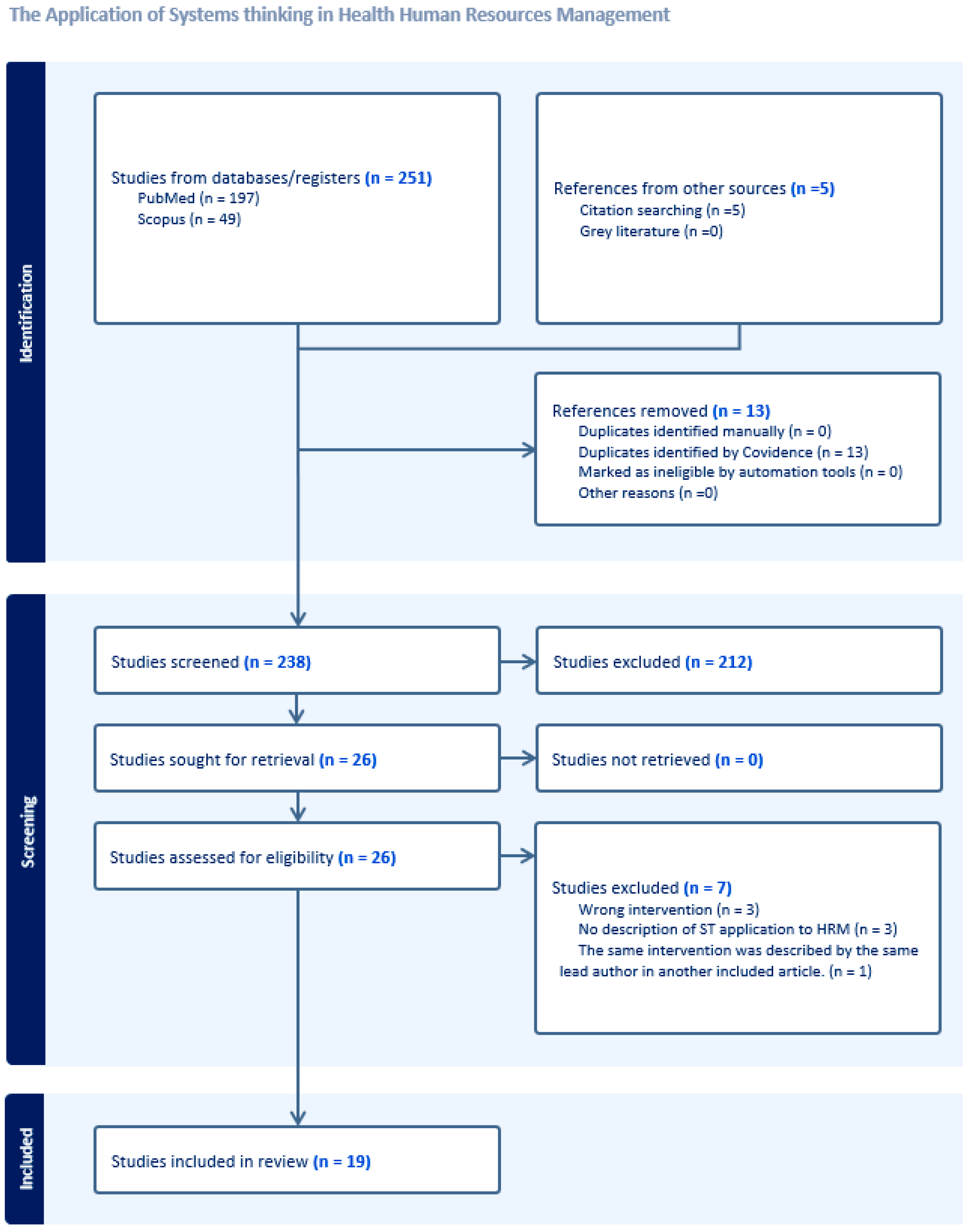

2. Methods

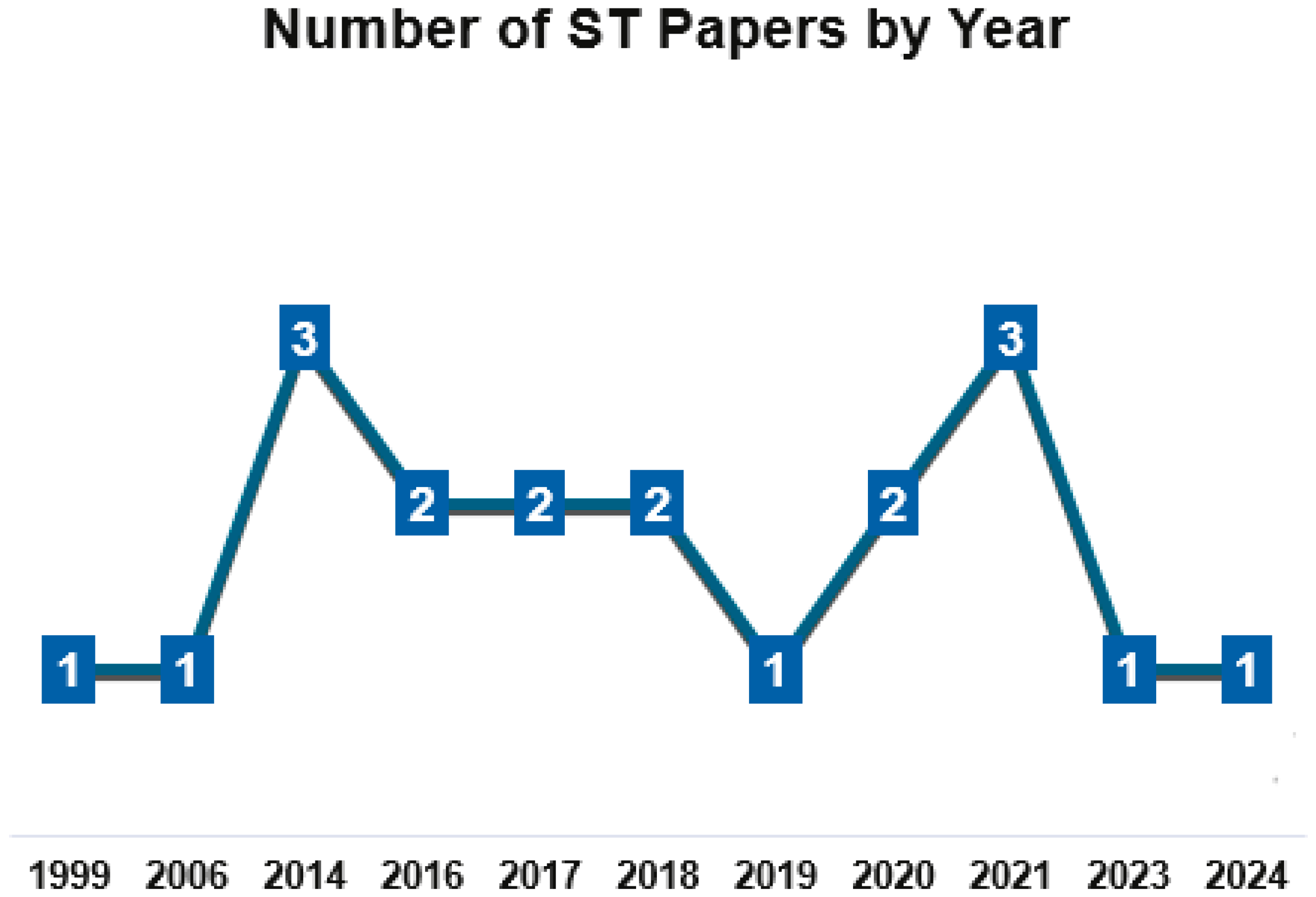

3. Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Mapping Relationships and Feedback Loops

4.2. Identifying Leverage Points for HR Interventions

4.3. Emergency Care

4.4. Community Health and Healthcare Access

4.5. Leadership and Workforce Development

5. Conclusions

- Building ST literacy through professional development and leadership training that emphasizes systems awareness and reflexive learning.

- Embedding participatory modeling within HR planning to align mental models across stakeholders and promote shared decision-making.

- Embedding ST in workforce evaluation frameworks to enable ongoing monitoring of interdependencies among policies, staffing, and service delivery outcomes.

- Supporting longitudinal research that examines how systems-oriented HRM approaches influence retention, motivation, and service quality over time.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thelen, J.; Fruchtman, C.S.; Bilal, M.; Gabaake, K.; Iqbal, S.; Keakabetse, T.; Kwamie, A.; Mokalake, E.; Mupara, L.M.; Seitio-Kgokgwe, O.; et al. Development of the Systems Thinking for Health Actions framework: A literature review and a case study. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e010191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Savigny, D.; Adam, T. (Eds.) Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. In Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rusoja, E.; Haynie, D.; Sievers, J.; Mustafee, N.; Nelson, F.; Reynolds, M.; Sarriot, E.; Swanson, R.C.; Williams, B. Thinking about complexity in health: A systematic review of the key systems thinking and complexity ideas in health. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trochim, W.M.; Cabrera, D.A.; Milstein, B.; Gallagher, R.S.; Leischow, S.J. Practical challenges of systems thinking and modeling in public health. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J.; Goff, M.; Rusoja, E.; Hanson, C.; Swanson, R.C. The application of systems thinking concepts, methods, and tools to global health practices: An analysis of case studies. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C.; Sambo, L.G. Health systems research and critical systems thinking: The case for partnership. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalla, A.D.G.; Bahr, R.R.R.; El-Sayed, A.A.I. Exploring the hidden synergy between system thinking and patient safety competencies among critical care nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.D.; Wade, J.P. A definition of systems thinking: A systems approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 44, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Lakhani, A. Using systems thinking methodologies to address health care complexities and evidence implementation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 20, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Anderson, D.E.; Rossow, C.C. Health Systems Thinking; Jones and Bartlett: Sudbury, MA, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D. Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems Theory. In The Science of Synthesis; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, D.H. The application of systems thinking in health: Why use systems thinking? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, H. Introduction to system thinking and causal loop diagrams. In Department of Chemical Engineering; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nuis, J.W.; Peters, P.; Blomme, R.; Kievit, H. Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, M.; Ryan, G. Distributing HRM responsibilities: A classification of organizations. Pers. Rev. 2006, 35, 618–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health Who.int. World Health Organization. 2006. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241563176 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Bourgeault, I.L.; Chamberland-Rowe, C.; Simkin, S.; Slade, S. A Proposed Vision to Enhance CIHI’s Contribution to More Data Driven and Evidence-Informed Health Workforce Planning in Canada; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zukowski, N.; Davidson, S.; Yates, M.J. Systems approaches to population health in Canada: How have they been applied, and what are the insights and future implications for practice? Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, N.R.; Wankar, A.; Arya, S.K. Feedback system in healthcare: The why, what and how. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebcir, M. Health Care Management: The Contribution of Systems Thinking; University of Hertfordshire: Hatfield, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.C.; Cattaneo, A.; Bradley, E. Rethinking health systems strengthening: Key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, K.; Martin, A.; Jackson, C.; Wright, T. Using systems thinking to identify workforce enablers for a whole systems approach to urgent and emergency care delivery: A multiple case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, C.; Prowse, J.; McVey, L.; Elshehaly, M.; Neagu, D.; Montague, J.; Alvarado, N.; Tissiman, C.; O’Connell, K.; Eyers, E.; et al. Strategic workforce planning in health and social care—An international perspective: A scoping review. Health Policy 2023, 132, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management Covidence. 2020. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Agyepong, I.A.; Aryeetey, G.C.; Nonvignon, J. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: Provider payment and service supply behaviour and incentives in the Ghana National health insurance scheme—A systems approach. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Zoeram, A.; Pooya, A.; Naji-Azimi, Z.; Vafaee-Najar, A. Simulation of quality death spirals based on human resources dynamics. Inquiry 2019, 56, 46958019837430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensberg, M.; Allender, S.; Sacks, G. Building a systems thinking prevention workforce. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, R.; Tomoaia-Cotisel, A.; Semwanga, A.R.; Binyaruka, P.; Chalabi, Z.; Blanchet, K.; Singh, N.S.; Maiba, J.; Borghi, J. Understanding the maternal and child health system response to payment for performance in Tanzania using a causal loop diagram approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvani, H.; Majdzadeh, R.; Khedmati Morasae, E.; Doshmangir, L. Analysis of Iranian health workforce emigration based on a system dynamics approach: A study protocol. Glob. Health Action 2024, 17, 2370095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leerapan, B.; Teekasap, P.; Urwannachotima, N.; Jaichuen, W.; Chiangchaisakulthai, K.; Udomaksorn, K.; Meeyai, A.; Noree, T.; Sawaengdee, K. dynamics modelling of health workforce planning to address future challenges of Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembani, M.; de Pinho, H.; Delobelle, P.; Zarowsky, C.; Mathole, T.; Ager, A. Understanding key drivers of performance in the provision of maternal health services in eastern cape, South Africa: A systems analysis using group model building. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.C.; O’Meara, P. Community paramedicine through multiple stakeholder lenses using a modified soft systems methodology. Australas. J. Paramed. 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paina, L.; Bennett, S.; Ssengooba, F. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: Exploring dual practice and its management in Kampala, Uganda. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.K.; Rawashdah, F.; Al-Ali, N.; Abu Al Rub, R.; Fawad, M.; Al Amire, K.; Al-Maaitah, R.; Ratnayake, R. Integrating community health volunteers into non-communicable disease management among Syrian refugees in Jordan: A causal loop analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, N.S.; Marchal, B.; Devadasan, N.; Kegels, G.; Criel, B. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: A realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers in Tumkur, India. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pype, P.; Mertens, F.; Helewaut, F.; Krystallidou, D. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: Understanding team behaviour through team members’ perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbock, C.; Krafft, T.; Sommer, A.; Beumer, C.; Beckers, S.K.; Thate, S.; Kaminski, J.; Ziemann, A. Systems thinking methods: A worked example of supporting emergency medical services decision-makers to prioritize and contextually analyse potential interventions and their implementation. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renmans, D.; Holvoet, N.; Criel, B. Combining theory-driven evaluation and causal loop diagramming for opening the “black box” of an intervention in the health sector: A case of performance-based financing in Western Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, G.; Dost, A.; Townshend, J.; Turner, H. Using system dynamics to help develop and implement policies and programmes in health care in England. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1999, 15, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenenberger, L.K.; Bayer, S.; Ansah, J.P.; Matchar, D.B.; Mohanavalli, R.L.; Lam, S.S.; Ong, M.E. Emergency department crowding in Singapore: Insights from a systems thinking approach. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 2050312116671953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Mills, A. Challenges for gatekeeping: A qualitative systems analysis of a pilot in rural China. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, T.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Nurses Physicians Allied health professionals | Non-healthcare workforce |

| Type of design | Quantitative Qualitative Mixed methods | |

| Language | English | Articles not in English |

| Year of publication | Articles published after 1999–December 2024 | Studies published before 1999 |

| Setting/context | Hospitals Emergency departments Public health settings Healthcare clinics Existing or past public health interventions Existing or past public health promotion programs (e.g., obesity prevention, tobacco control, maternal and child health) | Academia Education Research |

| Intervention | Health human resources management | Specific diseases management Drugs and medicine supply chain Specific treatment management Health information technologies and infrastructure Database management |

| Outcomes | Retention Healthcare human resources management | Improved healthcare infrastructure Improved specific disease management |

| Study characteristics | Systematic reviews Scoping reviews Rapid reviews Narrative reviews Case studies Interventions Applications Evaluations | Letters to editors Guidelines Study protocols Expert opinions |

| Author(s), Year | Level of ST Application | Country and Level of Application | Study Aim(s) | Type of Healthcare Setting | Study Design | Context | Types of ST Tools | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agyepong et al., 2014 [27] | Macro | Ghana–National | Examine why policies fail, identify unintended effects, show ST value, advocate for capacity building | Healthcare services—Public | Case study | Analysis of Additional Duty Hours Allowance policy | Soft Systems Modelling (SSM)—Stakeholder mapping, causal loop diagrams (CLDs) | The study used ST to demonstrate how seemingly isolated decisions, such as raising salaries for doctors at the Military Hospital, can trigger a cascade of intended and unintended consequences, including escalating wage bills, a series of strikes by health workers, disrupted healthcare services, and a loss of trust between the government and healthcare workers. The authors argued that a prospective ST approach, involving stakeholder analysis and anticipation of unintended consequences, could have led to a smoother and more effective policy implementation process. |

| Alizadeh-Zoeram et al., 2019 [28] | Meso | Iran–Facility | Simulate HR capacity model for quality improvement | Eye hospital clinic—not specified | Case study | Focus on unintended consequences of quality initiatives | Hard Systems Modelling (HSM)—System dynamics modeling, CLDs, stock and flow diagrams | The study highlighted how workforce constraints forced healthcare providers to cut corners by reducing service time, which, in turn, led to increased error rates. Efforts to address these challenges through hiring new staff initially resulted in lower productivity, as less experienced employees required time to develop their skills. To explore potential solutions, two policy interventions were tested. Reducing patient intake effectively lowered workload and improved service quality, while increasing human resources expanded capacity but required an adjustment period for new staff to gain experience. ST demonstrated that well-intended reforms could produce counterintuitive negative effects, underscoring the importance of strategic workforce planning. The study demonstrated how ST, through system dynamics modeling, can be a valuable tool for understanding the complex dynamics of healthcare delivery and informing health HR planning. |

| Bensberg et al., 2020 [29] | Macro | Australia–Regional | Explore capacity building for ST in prevention workforce | Public health | Qualitative | Healthy Together Victoria (HTV) intervention | SSM—Workforce framework, CLDs | The findings demonstrated that a ST approach can provide valuable insights into the complexities of building capacity for ST. By applying a systems lens, the researchers were able to: (1) identify the multiple interacting factors that contributed to or hindered the development of a ST workforce within HTV; (2) understand the dynamic relationships between these factors and how they influenced capacity building; (3) emphasize the importance of a holistic and long-term approach to capacity building that addresses both individual and organizational elements; and (4) develop recommendations for future interventions to promote ST in health promotion and other fields. Authors noted that a prevalent reductionist mindset was a barrier to ST adoption. |

| Cassidy et al., 2021 [30] | Macro | Tanzania–National | Develop CLDs for Payment for Performance (P4P) impacts on maternal and child health (MCH) | MCH services—Public | Qualitative | P4P program | SSM—CLDs, stakeholder dialogue | The study identified three core mechanisms affecting provider achievement of P4P targets: (1) changes in the supply of services (health worker motivation, drug and medical supplies availability, facility infrastructure); (2) changes in facility reporting (accuracy and timeliness of data reporting, risk of misreporting); (3) changes in demand for services (community perceptions, care-seeking behaviors, outreach, medicine availability). The CLDs identified several catalytic variables that impact multiple outcomes: drug and medical supply availability, staffing levels, and supervision quality. Recommendations included incentivizing key stakeholders (community health workers, health facility governing committees), addressing systemic challenges (drug shortages, inadequate staffing) and strengthening supportive supervision. The study concluded that ST, through the use of CLDs, can provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of P4P programs and inform the design of more effective interventions |

| Keyvani et al., 2024 [31] | Macro | Iran–National | Analyze policy interventions for health worker emigration | National health workforce—Public | Mixed methods | Emigration of health professionals | HSM—System dynamics model integrating realist review, interviews, scenario testing | SD model demonstrated interconnections between demographic, economic, and system factors driving emigration; tested policies to strengthen retention. |

| Leerapan et al., 2021 [32] | Macro | Thailand–National | Analyze supply-demand mismatches in workforce | Hospital services—Public | Case study | Workforce shortage under Universal Health Coverage (UHC) | HSM—Group model building, CLDs, stock and flow diagram, SD simulation | The simulation modeling revealed that hospital utilization created a self-reinforcing cycle of rising demand for hospital services and a persistent shortage of healthcare providers. Additionally, hospital-based care was not well-suited to effectively address the future needs of aging populations and the increasing prevalence of chronic illnesses. Shifting focus toward professions that deliver primary, intermediate, long-term, palliative, and end-of-life care could be a more effective approach. SD modeling confirmed that adapting care models to evolving health needs could serve as a high-impact strategy for workforce planning, though challenging to implement in the short term. The study underscores the value of systems thinking in planning Thailand’s health workforce and provides relevant insights for other LMICs facing similar issues. |

| Lebcir, 2006 [21] | Macro | Georgia–National | Illustrate policy resistance in family medicine reform | Family medicine—Public | Case study | Georgian health reform | HSM—SD modeling of feedback loops | The study’s analysis of the Georgian healthcare reform case and broader discussion of Systems Thinking offer several key insights and arguments: (1) healthcare systems are highly dynamic and complex; (2) policy resistance is a common problem in healthcare management; and (3) the failure to adopt systemic approaches contributes to policy resistance and suboptimal outcomes in healthcare. The analysis of the Georgian healthcare reform case illustrated how multiple factors, including physician training, licensing procedures, facility availability, and financial resources, intertwine to influence the provision of family medicine. Applying a systems-based approach in this context can help policymakers identify potential bottlenecks, anticipate unintended consequences of interventions, and design more effective reform strategies. |

| Lembani et al., 2018 [33] | Macro | South Africa–Regional | Identify factors affecting maternal health delivery | Maternal health—Public | Case study | Rural district in Eastern Cape | SSM—Group model building, semi-structured interviews, interrelationship diagrams (IRDs), CLDs | Stakeholders examined the complex connections among factors contributing to poor maternal health outcomes and identified feedback loops that perpetuated these challenges. They proposed strategies for sustainable improvement, highlighting the significant influence of leadership on overall system performance. Leadership was linked to multiple factors and feedback loops, particularly staff motivation and capacity building. Staff motivation, in turn, affected the quality of care, which influenced patient attendance and subsequently impacted workload. Without addressing workload, patient wait times, and satisfaction, the benefits of enhanced leadership and staff support on staff competence and attitudes would be limited. Understanding these interrelationships is essential for developing effective solutions, particularly in chronically underperforming health systems. Systems modeling through group model building offers a structured approach to help stakeholders identify and leverage existing resources within a dysfunctional system to improve overall performance. |

| Manley et al., 2016 [23] | Meso | UK–Facility/Trust | Identify workforce enablers for whole-systems urgent care | Urgent & emergency care—Public | Multiple case study | Five hospitals, community trust, ambulance trust | SSM—Whole-systems framing, analysis of inter- connections and feedback loops | Key findings centered around three primary workforce enablers crucial for the successful implementation of a ‘whole systems’ approach: (1) clinical systems leadership: This concept emerged critical need, advocating for leadership driven by individuals with clinical expertise and credibility; (2) integrated career and competency framework: This framework promotes a more integrated and flexible career path, facilitates the identification of skills gaps, informs learning and development needs, and aids supervision and mentorship across different contexts; (3) facilitators of work-based learning: The study highlighted the importance of workplace mentors and supervisors who can facilitate learning and development holistically, integrating the system’s overall goals and meeting the diverse learning needs of multidisciplinary teams |

| Martin & O’Meara, 2020 [34] | Macro | Australia–Regional | Explore community paramedicine (CP) perspectives | Rural CP services—Public | Qualitative | Rural underserved areas | Modified SSM, participatory workshop | The study concluded that active stakeholder participation and engagement were essential for the successful development and implementation of CP programs in rural Australia. This included ensuring that all stakeholders had a clear understanding of CP, its potential benefits, and the roles and responsibilities of community paramedics. The study highlighted the importance of addressing potential barriers such as resistance to change, funding constraints, and organizational culture to create a supportive environment for CP to thrive. |

| Paina et al., 2014 [35] | Meso | Uganda–Facility | Understand dual practice evolution and management | Urban facilities—Public | Multiple case study | Kampala, Uganda | HSM—CLDs, Vensim PLE Plus software (2012) | The study described the evolution of dual practices and revealed the drivers of dual practices and local management practices. It also provided insights that future health sector reforms in Uganda, such as health insurance and performance-based contracts, should have considered the role of dual practice and anticipated potential unintended consequences. It showed that restrictive policies without addressing low salaries led to unintended workforce shortages in the public sector. |

| Parmar et al., 2021 [36] | Macro | Jordan–International | Integrate community health volunteers (CHVs) for refugee non-communicable disease (NCD) care | Refugee health—Public | Qualitative | Syrian refugees in Jordan | SSM—Participatory workshop, CLDs | The study highlighted the critical role of systems thinking in understanding and addressing the complex challenges of providing healthcare in humanitarian settings. By applying tools like CLDs and engaging a range of stakeholders, the study identified: (1) key challenges facing Syrian refugees with non-communicable diseases; (2) potential community health volunteer programs to address these challenges; and (3) key factors for successful implementation. |

| Prashanth et al., 2014 [37] | Macro | India–Regional | Study capacity building in district health systems | Maternal health—Public | Mixed-methods realist | Tumkur, Karnataka | SSM—Complex adaptive systems approach, multipolar framework | The study emphasized that capacity-building initiatives should have considered the existing relationships between internal factors (individual and organizational) and external factors (policy and the socio-political environment) of the organizations they aimed to support. Program planners needed to focus on identifying opportunities to create beneficial alignments between these factors during the design and implementation stages. Recognizing that local health systems might have differed in their internal configurations, capacity-building programs needed to accommodate the possibility of change occurring through multiple pathways |

| Pype et al., 2018 [38] | Micro | Belgium–Unit | Explore team interactions in workplace learning | Palliative care—Public | Qualitative | Home care teams | SSM—Complex adaptive systems lens, interviews | The study, which focused on palliative home care teams in Belgium, found that healthcare teams could be effectively understood as CAS. The analysis of interviews with nurses, community nurses, and general practitioners revealed key insights into how their interactions shaped team behavior and workplace learning. The study highlighted workplace learning as a key emergent behavior arising from the interactions within these healthcare teams. As team members collaborated and exchanged information, they developed new skills and adapted their practices |

| Rehbock et al., 2023 [39] | Macro | Germany–Regional | Address rising emergency medical services (EMS) demand | Emergency services—Public | Case study | Oldenburg, Lower Saxony | SSM—CLDs, best intervention variables, intervention analysis | The study found that rising EMS demand was a complex issue influenced by numerous factors, including those related to hospitals and other medical services, patients, EMS staff, the prehospital EMS system itself, and a ‘silo mentality’ that could hinder collaboration between different parts of the healthcare system. Based on the analysis of BIVs and their connections to the key issue, the researchers suggested prioritizing interventions such as a standardized structured triage tool. The study highlighted the value of a systems thinking approach, particularly the use of causal loop diagrams, for understanding complex healthcare challenges and informing the development and implementation of effective interventions |

| Renmans et al., 2017 [40] | Macro | Uganda–Regional | Evaluate performance-based financing (PBF) mechanisms with CLDs | Private not-for-profit (PNFP) health centers—Private | Case study | Western Uganda | SSM—Theory-driven evaluation, CLDs | Researchers identified three important hypotheses: “success to the successful”, “growth and underinvestment”, and the “supervision conundrum”. The first hypothesis means that the initial investment in the facility will lead to an improvement of the work environment and consequently of the quality score of the facility, which will lead to more funds and an even better work environment. The second hypothesis relates to the fact that an increased number of patients puts extra pressure on the work environment (e.g., the available space) and the health workers (increased workload) which may bring down the quality if not compensated with new investments. The final hypothesis highlights the danger of adding an extra verification task to the job description of the supervisors. |

| Royston et al., 1999 [41] | Macro | UK–Regional | Enhance emergency care policy design | Emergency care—Public | Review | England’s National Health Service (NHS) | HSM—SD modeling | The study emphasized key conceptual and methodological considerations for effectively utilizing system dynamics modeling: (1) distinguishing between ‘solution-oriented’ and ‘learning-oriented’ modeling approaches; (2) underscoring the importance of stakeholder engagement in the modeling process; and (3) advocating for a balanced approach that combined group learning with ‘backroom’ technical work. |

| Schoenenberger et al., 2016 [42] | Micro | Singapore–Unit | Analyze emergency department (ED) crowding drivers | Emergency care—Public | Case study | ED department, Singapore | SSM—CLDs, path analysis | The researchers used CLD to analyze the potential impact of three different policies: (1) Introduction of geriatric emergency medicine; (2) Expansion of ED staff training; and (3) Implementation of enhanced primary care. The path analysis, a method for analyzing causal relationships within the CLD, revealed that the first two policies have potential unintended consequences that could worsen ED crowding. The study found that enhancing primary care was the only policy without apparent negative side effects. |

| Xu et al., 2017 [43] | Macro | China–Regional | Examine gatekeeping pilot impacts | Primary care, hospitals—Public | Mixed-methods qualitative | Two rural townships | SSM—CLDs, health system blocks, policy analysis | The study identified reinforcing feedback loops that hindered the gatekeeping program: (1) Vicious cycles in primary care: Limited clinical experience, inadequate equipment, and restricted pharmaceuticals weakened primary care capacity, reducing patient trust and driving more patients to hospitals, further undermining primary care; (2) Human resource sustainability: A shift toward public health services and declining patient visits made primary care jobs less attractive, complicating doctor recruitment and retention; and (3) Hospital dominance: Hospitals’ superior infrastructure, salaries, and career prospects reinforced patient preference for hospital care, further weakening primary care. Using ST through CLD, the study highlighted unintended policy consequences such as the restriction of service functions at primary care facilities and the impact of performance evaluations focused on public health services, on the motivation, competence, and retention of primary care doctors. It also showed how hospital dominance siphoned human resources from primary care, exacerbating the gatekeeping program’s challenges. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Babysheva, V.; Neiterman, E.; Bigelow, P.; Yessis, J. Systems Thinking and Human Resource Management in Healthcare: A Scoping Review of Core Applications Across Health System Levels. Systems 2025, 13, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111001

Babysheva V, Neiterman E, Bigelow P, Yessis J. Systems Thinking and Human Resource Management in Healthcare: A Scoping Review of Core Applications Across Health System Levels. Systems. 2025; 13(11):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111001

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabysheva, Victoria, Elena Neiterman, Philip Bigelow, and Jennifer Yessis. 2025. "Systems Thinking and Human Resource Management in Healthcare: A Scoping Review of Core Applications Across Health System Levels" Systems 13, no. 11: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111001

APA StyleBabysheva, V., Neiterman, E., Bigelow, P., & Yessis, J. (2025). Systems Thinking and Human Resource Management in Healthcare: A Scoping Review of Core Applications Across Health System Levels. Systems, 13(11), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13111001