Abstract

This study examines the factors that lead students to consider or avoid a career in sales, focusing on behaviors and preferences during the transition period following the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Conducted in 2021, the study captures how the pandemic has changed traditional aspects of sales work, such as face-to-face interaction, and explores the lasting impact of these changes on young professionals. A sample of 671 business and engineering students participated in an online survey; data analysis was performed by using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (SEM-PLS). Results show that intrinsic and social motivations enhance the perceived attractiveness of a sales career, which, in turn, impacts career intentions. Although empathy and COVID-19-related fears lack a direct effect on the intention to pursue a sales career, digital skills reinforce the connection between job attractiveness and career intentions in a digital-centric environment, having a moderating role. These findings emphasize the evolving nature of sales careers, highlighting the need to align career development strategies with young people’s intrinsic motivation and digital competencies. This study adds to the understanding of motivational factors in sales career decisions and offers valuable insights for employers seeking to attract motivated talent in a shifting industry landscape.

1. Introduction

Career choice is an important decision for every human being because the quality of everyone’s life depends on this choice [1]. Understanding the factors that drive career choice is crucial, not only for individuals but also for employers who rely on a motivated, skilled workforce. Although significant research has addressed the various influences on career choice, there are studies that still conclude that a career in sales is not attractive enough for young people [2,3]. The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed traditional sales practices. Face-to-face interaction is giving way to virtual communication and digitized processes [4,5]. These changes necessitate a re-examination of how intrinsic motivators (e.g., personal success) and extrinsic factors (e.g., financial incentives) interact with social influences (e.g., mentorship) to influence students’ attitudes toward sales careers. The focus of this study is on intrinsic and social motivators, and extrinsic motivators, such as financial incentives, are not part of the scope of this analysis.

This study fills this gap by examining the factors that influence students to pursue or avoid a career in sales. It offers insights into how employers can better attract and retain young talent in a changing, digitized sales landscape. By focusing on these current challenges, the study offers both theoretical advances and actionable recommendations for practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated digital transformation across industries and heightened people’s concerns about their personal safety, factors that may have fundamentally changed the attractiveness of sales careers. Yet the literature on how these changes impact career motivation, particularly among younger generations, still has much room for growth. Research suggests that members of Generation Z bring different values and priorities to the workplace than previous generations [6]. While sales professionals have historically been viewed as primarily motivated by money [7], other studies suggest that career choice is a complex process influenced by both internal and external factors [8]. Nevertheless, there is little empirical research on whether these intrinsic motivators, such as personal achievement, affiliation, or power, might influence the attractiveness of a sales career for today’s youth. However, rather than proposing an inventory of factors that influence career choice, we propose an approach based on a motivational model that has the potential to explain career choice decisions in general. The model we will use in the following is McClelland’s Three Needs Theory.

McClelland’s model states that people exhibit different behaviors based on three important needs or motives—achievement, power, and affiliation—which they satisfy through interaction with their environment. People can be categorized into different personality types depending on which of the three needs dominates their personality. All people have all three motives (needs) but to varying degrees. According to this model, people in an organization should be assigned different work tasks depending on their dominant needs [9]. The three dominant needs are as follows:

Dominant need for achievement: these organizational members are suited to relatively difficult projects with achievable but challenging goals. They need to receive frequent feedback. Even if money is not the most important motivator, it is an effective form of feedback if it is linked to clear measures of success. Dominant need for affiliation: These employees work best in a collaborative environment where a sense of belonging is a source of fulfillment for them. Dominant need for power: In certain contexts, they may be allowed to direct the work and efforts of other colleagues. A comprehensive understanding of motivational factors is critical to effectively managing sales teams and attracting young talent to a sales career. As French and Emerson [10] point out, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to rewards will not meet the diverse motivational needs of employees.

By exploring how these needs influence students’ perceptions of a career in sales, this study offers new insights into the intrinsic motivations that may influence career decisions in this field. Considering the impact of digitalization on the role of the salesperson and the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 crisis, we also examine two additional factors that may influence students’ career intentions: digital skills and health-related anxiety.

The predictive power of various models to explain career intentions has been examined in different contexts. For example, Moore and Burrus [11] examined 11th and 12th-grade students’ intentions to choose careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields using variables related to mathematics knowledge, vocational interests, conscientiousness, and specific Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) variables.

To this end, this study aims to answer three key research questions: (a) How do dominant personal needs (achievement, power, and affiliation) influence the perceived attractiveness of a sales career and the intention to pursue it? (b) Do digital skills strengthen the link between the perceived attractiveness of a sales career and the intention to work in sales? (c) Does the fear of health crises (e.g., COVID-19) influence the intention to work in sales?

To answer these questions, the article is organized as follows: a literature review and hypothesis development section, an overview of the research design and data collection methods, a results and discussion section, and a concluding section outlining the practical implications. This study thus contributes to the understanding of motivational dynamics in sales career choice and provides actionable insights for employers seeking to attract and retain talent in a rapidly evolving field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1.1. The Relationship Between Intrinsic Motivation and the Attractiveness of a Sales Career

In addition to demographic changes in motivations, sales activities themselves are also changing, with the focus shifting to service and customer-centric approaches [12]. In this context, people who want to work in sales need to be confident in themselves that they have skills and can apply them at a high professional [7] so that a job in sales allows them to use the skills. Amongst the more recent trends in career orientation, what [13] calls a “protean career” also stands out, i.e., the need to have responsibility and control over one’s career, as well as the need to make career decisions and evaluate career success based on personal values [14]. Presumably, a career in sales is perceived as a way to exercise control over one’s professional abilities, which is consistent with these new trends. When intrinsic motivation is aligned with one’s values and goals, it can lead to a sense of importance and professional success [15]. These aspects are consistent with the need for achievement in McClelland’s model, which leads us to analyze intrinsic motives (professional achievement, control over one’s work, importance, etc.) as a factor in choosing a career in sales. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

There is a direct positive relationship between intrinsic reasons to work in sales and the attractiveness of a career in sales.

Given the increasing importance of sales activity for business success [16], companies began to focus on customer relationship management (CRM), which required a redefinition of the salesperson’s job description. They were looking for employees with emotional intelligence [17], who were familiar with new technologies [18], who were well-trained, motivated, and customer-oriented [19], and who provided customers with high-quality service primarily through persuasion and refrained from aggressive sales techniques [20]. All of these aspects suggest that the reasons that drive people to pursue a career in sales include developed social skills, emotional intelligence, the ability to influence people and effectively manage customer decisions and stressful situations. These aspects are in line with McClelland’s model, which emphasizes the need for affiliation and power, the latter being understood as the ability to positively influence situations and people. Since these motivations have to do with social interaction, we believe it is justified to formulate the following hypothesis:

H2.

There is a direct positive relationship between the social reasons to work in sales and the attractiveness of a career in sales.

2.1.2. The Attractiveness of a Sales Job and the Intention to Work in Sales

Previous research has shown that some people are attracted to jobs that offer challenges or put them under pressure [21]. Along these lines, Handley et al. [16] showed that the students they researched described a job in sales through “excitement” and Karakaya et al. [22] suggest that perceptions of the characteristics of a sales job influence the intention to work in sales. The attractiveness of a job can then be assessed through the lens of the need for achievement as well as the need for affiliation or power, as described by McClelland. Continuing this investigation, we want to highlight the relationship between the attractiveness of a sales career and the intention to work in sales and propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

There is a direct positive relationship between the attractiveness of a career in sales and the intention to work in sales.

2.1.3. The Role of Social Influences and Empathy in Increasing the Intention to Pursue a Career in Sales

In this study, ‘social influences’ refer to the immediate social circle, such as peers, family, and mentors, whose opinions and actions shape career decisions. The need to belong is characteristic of all people, but as McClelland shows, it varies from person to person, with people being more or less motivated to form social bonds and be accepted by others. Because of this need, people may be interested in the opinions of people they want to be like, thus strengthening their sense of belonging. The role of opinion leaders in today’s society is increasing, and many young people make their decisions based on what they hear about them. In relation to a career in sales, research highlights that such interpersonal influences significantly impact young people’s career choices. Spillan et al. [23] showed that students who have family members who work in sales have a better opinion of a career in this field. Similarly, Little et al. [24] showed that students who experience a positive attitude toward a career in sales in conversations with their parents are more likely to be interested in such a career. Based on these findings, we hypothesize the following:

H4.

There is a direct positive relationship between the opinions and actions of peers, family, and mentors (social influences) toward a career in sales and an individual’s intention to work in sales.

Empathy plays a central role in social interactions and organizational performance, especially in professions that focus on human relationships, such as sales. Leary et al. [25] developed the Need to Belong Scale (NTBS) to assess the desire for acceptance and belonging. Although it does not directly measure the desire for social contact, such as extraversion and affiliation motivation, it nevertheless reflects this need. Gastal and Pilati [26] adapted and validated the scale in Brazil and found that a need for affiliation is associated with a high level of empathy. In the field of sales, empathy enables salespeople to better understand customer needs, thereby increasing customer value [27,28] and promoting customer-centric approaches [29]. Empathy facilitates key behaviors like active listening and adaptive selling, which strengthen customer relationships and improve business outcomes [30]. Delpechitre et al. [31] emphasize that empathy plays a moderating role in the process of value co-creation, fostering customer trust and loyalty.

Empathy is also considered a catalyst for prosocial behavior, as it influences a person’s intention to help or cooperate [30]. In organizational contexts, this ability to understand and respond to the needs of others makes professions with a strong relational component, such as sales, more attractive to potential employees. Zhu et al. [32] emphasize that empathy elicited through communication can positively influence a person’s intention to respond positively, highlighting the potential of empathy as a motivational factor for career decisions.

The dual nature of empathy is also noteworthy. Supramaniam et al. [33] categorize empathy into two key dimensions: cognitive empathy (the ability to understand the thoughts and emotions of others) and affective empathy (the ability to empathize with the emotions of others and mediate emotional responses). Both forms of empathy have been shown to positively influence salespeople’s competence and customer focus, reinforcing the idea that empathy is an important asset for sales professionals.

Building on this theoretical foundation, we hypothesize the following:

H5.

There is a direct positive relationship between empathy and the intention to work in sales.

2.1.4. Fear of COVID-19 and the Intention to Work in Sales: The Mediating Role of a Physical Distancing Behaviour

Numerous studies have shown that COVID-19 has had a major impact on sales strategies and processes [4,34,35], as face-to-face interaction between salespeople and customers has been abandoned and virtual interaction has become widespread [4,36].

These changes were also supported by employees who began to prioritize their health and re-evaluate their goals related to income and job performance [37]. This evidence suggests that the pandemic has had a significant impact on career intentions and goals [38]. In the context of the COVID-19 health crisis, frontline workers were particularly affected by the fear of contracting the virus, as they perceived a high risk of infection due to frequent interactions with various clients, and this fear is responsible for feelings such as tension and nervousness [39,40]. Some studies show that not only people who have been working during the pandemic revised their career goals, but that the pandemic has led to real career crises and contributed to an increase in students’ anxiety about careers and inappropriate career choices [41].

On another level, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a heightened sense of nostalgia in people, triggered by experiences related to isolation, social distancing, insecurity, and anxiety [42]. Although nostalgia is sometimes seen as a regressive emotion, it can serve as a coping mechanism and provide people with a sense of comfort, direction, and hope. In the post-pandemic context, this state of nostalgia could influence perceptions of occupations that involve close contact with the public, such as sales, where direct physical contact was once common but is now perceived as a potential risk [43]. The article by Ybema [44] supports the idea that nostalgia is not just a backward-looking emotion but a tool for coping with the present. Therefore, the fear of COVID-19 can be interpreted as part of a broader nostalgic longing for a “safe” time that leads people to avoid personal tasks such as selling.

In light of the above, and considering that sales activity involves sustained interaction with customers, we hypothesize the following:

H6.

There is a direct negative relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and the intention to work in sales.

After the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the global COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, one of the measures to slow the spread of the virus was physical distancing [45]. Nevertheless, adherence to this rule during the pandemic was not linear and varied from person to person, with some people adhering to it more than others [46]. Unver et al. [47] developed the Physical Distancing Behavior Scale, which includes 39 items on attitudes, perceived control, self-efficacy, subjective norms, and environmental constraints, among other factors that explain adherence to the physical distancing rule. Subjective and moral norms have good potential to predict distancing behavior [48], but it has been shown that people’s behavior can also be strongly influenced by their perception of risk [49]. For example, people who perceived the risk of infection with COVID-19 as high were more likely to follow the rules set by the WHO [50]. The same idea was also explored by Versteegt et al. [51], who emphasized the role of threat and moralization in the adoption of physical distancing behavior. Based on these general records, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H7.

There is a direct positive relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and the willingness to adopt a certain behavior (physical distancing) in sales activity during the pandemic.

Before COVID-19, sales primarily involved direct human interaction, though online sales existed [52]. Post-crisis, health safety, and distancing have become vital for individual protection [53]. Van Schaik et al. [54] differentiated between observing distancing behaviors (an aspect found in most studies) and understanding the motivations behind them. Hedayati et al. [55] found that perceptions of disease severity and personal vulnerability significantly influenced the adoption of preventive behaviors. In addition, Grano et al. [56] found that individuals’ expectations of self-protection as an effective response influence the adoption of behaviors. Thus, those confidently practicing distancing believe it effectively mitigates the virus threat. Conversely, salespeople often exhibit higher insecurity and neuroticism, mainly due to job characteristics [57], which may amplify their fear of illness. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8.

There is a direct negative relationship between the willingness to adopt certain behaviors (physical distancing) in sales during the pandemic and the intention to work in sales.

The previous analyses show that the greater the fear of COVID-19, the lower the intention to work in sales and the greater the willingness to physically distance oneself. On the other hand, the higher the willingness to distance oneself physically, the lower the intention to work in sales. Based on these hypotheses, we want to find out whether, in addition to the direct influence on the intention to work in sales, the willingness to physically distance oneself also plays a mediating role between the fear of COVID-19 and the intention to work in sales. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H8a.

Willingness to adopt a certain behavior (physical distancing) in sales during the pandemic mediates the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and intention to work in sales.

2.1.5. The Moderating Role of Digital Skills

Digital skills are crucial in today’s sales environment, where technology increasingly shapes sales activities [35]. People with advanced digital skills can use digital marketing tools, CRM, and social media platforms to optimize sales performance [34]. As a result, the attractiveness of sales careers is expected to increase as these skills enable individuals to be more effective and achieve better results, contributing to a positive perception of the field.

The decision to focus on digital skills as a moderating variable is due to the significant changes that took place in sales roles during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The widespread shift to virtual sales processes and the growing reliance on digital platforms such as video conferencing tools and CRM systems have highlighted the crucial role of digital skills in modern sales careers [58,59,60]. As organizations increasingly adopt hybrid working models and digital communication becomes the norm, the ability to use these tools has become a key differentiator for career success [59]. Unlike other potential moderators, such as career counseling or institutional support, digital skills have a more direct and immediate impact on an individual’s ability to adapt to these changing work environments, making them a relevant and timely variable to examine in the context of sales careers.

According to McClelland’s motivation theory [9], those with a strong need for achievement are driven to meet personal goals, and sales offer measurable outcomes that attract competitive individuals seeking professional satisfaction [61]. If these individuals have digital skills, it is expected that they will be better able to realize their potential, which increases the attractiveness of the career and, implicitly, the intention to work in this field. In contrast, the need for affiliation is fulfilled through customer interactions and teamwork, which digital capabilities can enhance by facilitating communication and collaboration, further increasing career appeal [31]. The need for power also draws individuals to sales, as it offers opportunities to influence customer decisions [62]. Thus, possessing digital skills can amplify this influence, making sales even more attractive. We hypothesize that the impact of sales career attractiveness on the intention to enter this field is strengthened by digital skills. Consequently, we hypothesize the following:

H9.

Digital skills moderate the relationship between the attractiveness of a career in sales and the intention to work in sales.

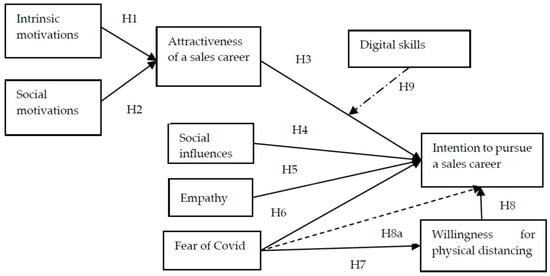

The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model. Note: Black line: direct effect; Dash dot line: mediating effect; Long dash dot line: moderating effect.

2.2. Data Collection

To test the hypotheses, an online survey was conducted in April 2021 among students from business or engineering universities in Romania on their perceptions of a sales career in the business-to-business sector. The dataset reflects behavior and attitudes in the post-COVID-19 transition phase and captures shifts in motivational priorities influenced by health concerns and accelerated digitalization in the sales industry. Respondents were informed about the research purpose and the confidentiality of their responses.

Nine latent variables were defined, which were measured using Likert scales (from 1—totally disagree to 5—totally agree) and the semantic differential scale (from 1—not at all to 5—to a great extent) and constructed on the basis of the literature (Table 1). All latent variables are reflective in nature. Attempts were made to avoid complex or ambiguous items [63]. The questions of the questionnaire were discussed with several experts from the academic field to ensure face validity [64]. In addition, a pretest was conducted with 20 students to identify possible errors, confusing answers, and difficulties in understanding the questions [65].

A snowball sampling method was used to select respondents, allowing members of rare populations to be identified through referrals [64]. The use of a probabilistic sampling method was difficult to implement due to the access restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as direct recruitment was difficult to achieve. To reduce this disadvantage, Memon et al. [66] recommend determining the sample size using a power analysis that considers the dependent variable with the largest number of predictors and uses as parameters: the effect size, the statistical power, and the significance level. In the current study, the minimum sample size calculated with G*Power 3.1 is 166 with a mean effect size f2 = 0.15, a power of 0.95, and a significance level of 0.05. Since our sample comprises 671 respondents, we can assume that the sample size is adequate.

Regarding the structure of the sample, 84.65% are undergraduate students while 15.35% are master’s students, 51.27% have a business specialization and 48.73% have a technical specialization, 9.99% work in sales, 35.02% work in another field while 54.99% do not work, 50.37% are men, and 49.63% are women.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

The data analysis was performed using the structural equation modeling approach based on partial least squares, carried out with Smart-PLS 4.0 software [67]. Reliability measures were calculated to evaluate the measurement model: Cronbach Alpha (α) and composite reliability (rho_c). The data meet the requirements for good reliability, as all values fulfill the threshold criterion of 0.7 [68]. The convergent validity of the construct is proven, as the average variance extracted (AVE) is above the cut-off value of 0.5, and the factor loadings exceed the recommended threshold value of 0.7 [69] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurement constructs reliability and validity.

Table 1.

Measurement constructs reliability and validity.

| Latent Variable and Indicators | Indicator Loadings |

|---|---|

| Intrinsic motivations (IM) (adapted from McClelland [9]; Pullins [70]; Cravens et al. [71]) | |

| α = 0.862; rho_c = 0.907; AVE = 0.709; VIF = 2.318 | |

| If I had a job selling to companies (in the business-to-business market), that would appeal to me because: | |

| I can utilize my skills | 0.874 |

| I have a high degree of control over my professional activity | 0.794 |

| It allows me to utilize my knowledge | 0.884 |

| I feel responsible (as other companies are dependent on me) | 0.813 |

| Social motivations (SM) (adapted from McClelland [9]; Moberg and Leasher [72]) | |

| α = 0.764; rho_c = 0.864; AVE = 0.680; VIF = 1.646 | |

| If I had a job selling to companies (in the business-to-business market), that would appeal to me because: | |

| I have to convince customers/negotiate with customers | 0.839 |

| I have to deal with a lot of people | 0.877 |

| I have to work in the field | 0.753 |

| Attractiveness of a sales career (ASC) (adapted from Handley et al. [16], Mahlamäki et al. [73]) | |

| α = 0.928; rho_c = 0.948; AVE = 0.821; VIF = 3.656 | |

| A career in sales is exciting | 0.902 |

| I find a career in sales interesting | 0.906 |

| A career in sales is enjoyable | 0.902 |

| A career in sales offers exciting challenges | 0.915 |

| Digital skills (DS) (adapted from Alt and Raichel [74]; Hartmann and Lussier [75]) α = 0.795; rho_c = 0.879; AVE = 0.709; VIF = 1.760 | |

| I can communicate via video platforms (Zoom, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams) | 0.793 |

| I can easily create a presentation on video platforms | 0.898 |

| I have no fear of contact when communicating via video platforms if I have to open the camera | 0.833 |

| Empathy (E) (adapted from McBane [76]; Limbu et al. [77]) | |

| α = 0.843; rho_c = 0.888; AVE = 0.613; VIF = 1.787 | |

| Before I make a decision, I try to understand the point of view of those who disagree with me | 0.819 |

| I consider myself a person who is very attentive to the problems of others | 0.835 |

| Before I criticize someone, I try to put myself in their shoes and imagine how they would feel | 0.757 |

| I often show compassion for people who are less fortunate than me | 0.703 |

| Sometimes I try to understand my friends better by imagining how certain aspects are seen from their point of view. | 0.793 |

| Social influences (SI) (adapted from Dalci and Ozyapici [78]; Adya and Kaiser [79]) | |

| α = 0.801; rho_c = 0.870; AVE = 0.626; VIF = 1.740 | |

| I have friends who work in sales, and they made me want to work in this field | 0.794 |

| Press interviews with business-to-business specialists made me think about a career in sales | 0.823 |

| Posts from public figures on social media got me excited about such a career | 0.815 |

| I have relatives who work in sales and influenced me to pursue such a career | 0.730 |

| Fear of COVID-19 (FC) (adapted from Ahorsu et al. [80]; Martínez-Lorca [81]) | |

| α = 0.851; rho_c = 0.895; AVE = 0.681; VIF = 2.081 | |

| I am generally afraid of COVID-19 | 0.879 |

| I feel uncomfortable when I think about COVID-19 | 0.896 |

| I feel physically impaired when I think about COVID-19 | 0.744 |

| When I see news and stories about COVID-19 on social media, I get anxious and fearful | 0.772 |

| Willingness for physical distancing (WPD) (adapted from Pfattheicher et al. [82]) | |

| α = 0.813; rho_c = 0.886; AVE = 0.721; VIF = 1.908 | |

| I would be more afraid of direct contact with customers | 0.874 |

| I would use the telephone more when communicating with customers | 0.872 |

| I would make more use of video communication platforms | 0.799 |

| Intention to pursue a sales career (ISC) (adapted from Handley et al. [16]; Peltier et al. [83]) | |

| α = 0.921; rho_c = 0.950; AVE = 0.865; VIF = 3.908 | |

| I am determined to work in sales | 0.941 |

| The probability of having a job in sales is high | 0.900 |

| I have seriously considered working in sales | 0.948 |

To assess the discriminant validity of the model, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) matrix (Table 2) was determined, which estimates the inter-construct correlations [84]. As all values are below the cut-off level of 0.9 [85], the model fulfills the conditions for discriminant validity.

Table 2.

The heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) matrix.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) does not exceed the threshold of 5, which demonstrates the model is not affected by collinearity [86]. Taking all these measures into account, it can be concluded that the constructs are robust.

3.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

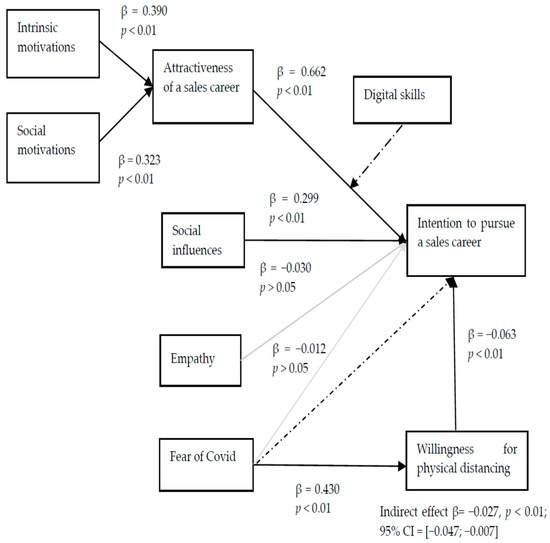

In order to test the hypotheses, a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples was carried out, whereby the direct, indirect, and moderating effects were evaluated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The structural model. Note: Black full line-supported hypothesis for direct effect; Gray full line-unsupported hypothesis for direct effect; Long dash dot line-supported hypothesis for moderating effect; Dash dot line-supported hypothesis for mediating effect; CI—Confidence interval.

Table 3 shows the direct effects of the variables considered in the model.

Table 3.

Test of the direct effects.

There is a direct positive relationship between intrinsic motivations and the attractiveness to work in sales, with a medium strength (β = 0.390, p < 0.01). The more people are motivated to control their work life, utilize their skills, and take on more responsibility, the more they are attracted to pursue a career in sales, thus supporting hypothesis H1.

The attractiveness of a sales career is also influenced by social motivations. Since people are more socially oriented to interact with other people and work outside the office, they are more attracted to pursue a career in sales. As the path coefficient is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.323, p < 0.01), this leads to the acceptance of hypothesis H2.

The attractiveness of a career in sales, described as interesting, exciting, or enjoyable, leads to an increase in the intention to pursue this type of career. The strength of this relationship is high and statistically significant (β = 0.662, p < 0.01), leading to the acceptance of hypothesis H3.

The current study proves the influence of family, peers, social media, or business-to-business experts in pursuing a sales career (β = 0.299, p < 0.01), leading to the acceptance of hypothesis H4.

Empathy does not influence the intention to work as a salesperson (β = −0.030, p > 0.05) in business-to-business as the relationship between the two variables is not statistically significant, thus not supporting hypothesis H5. Therefore, the ability to care about others, understand their differing opinions, or empathize with them when they are criticized does not increase the propensity to pursue a career in sales.

There is no statistically significant relationship between fear of COVID-19 and the intention to pursue a career in sales (β = −0.012, p > 0.05), which does not support hypothesis H6. Even if people are afraid of COVID-19, fear that manifests itself through negative physical and psychological reactions, this fear is not strong enough to influence the intention to work as a sales representative in the business-to-business sector.

In a healthy crisis, the fear of contracting COVID-19 positively influences the willingness to adopt a distancing behavior in sales activities (β = 0.430, p < 0.01). The more people are afraid of catching the virus, the more they tend to avoid direct contact with the customer and use telephone or video platforms to a greater extent. Hypothesis H7 is therefore supported.

The willingness to distance oneself physically has a negative impact on the intention to pursue a sales career in the business-to-business market. The more people tend to avoid direct contact during a health crisis, the less determined they are to pursue a career in sales. The strength of this relationship is weak but statistically significant (β = −0.063, p < 0.01), leading to the acceptance of hypothesis H8.

As regards the relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and the intention to pursue a sales career, the direct effect is not significant (β= −0.012, p > 0.5) (Table 2), and the indirect effect is significant (β= −0.027, p < 0.01) (Table 4), so there is indirect-only mediation [87]. Since the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect [−0.047; −0.007] do not contain a zero value, it can be concluded that the indirect effect is statistically significant [69], which supports hypothesis H8a. Fear of COVID-19, therefore, has no direct influence on the intention to work in sales but an indirect negative influence, which is mediated by the willingness to distance oneself. The greater the fear of COVID-19, the lower the students’ interest in a career in sales if they tend to display distancing behavior because they are afraid of direct interaction with customers.

Table 4.

Indirect effect.

Since digital skills change the strength of the relationship between the attractiveness of a sales career and the intention to pursue a career in this field, it is considered a moderator variable [69]. Therefore, a high level of digital skills increases the intensity of the relationship between the attractiveness of a career in sales and the intention to work in this field. This effect is weak (β = 0.055) but statistically significant (p < 0.01), so hypothesis H9 is accepted (Table 5). It can be concluded that the positive effect of the attractiveness of a career in sales on the intention to work in this field is stronger if the person benefits from better-developed digital skills. The effect size of the moderation (f2 = 0.012) can be estimated as medium [69].

Table 5.

The moderating effect.

The coefficient of determination R2 for the variable intention to pursue a career in sales is 0.72. The model, therefore, has moderate to high explanatory power [69], with 72% of the variation in the intention to pursue a career in sales explained by the endogenous variables included in the model. To assess the goodness of fit of the model, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was determined to be SRMR = 0.071, which is below the cut-off value of 0.08 [69]. The predictive power of the model is demonstrated by the Q2predict values for the exogenous variables as follows: Q2ASC = 0.421, Q2ISC = 0.449, Q2WPD = 0.180. Considering that all values are higher than 0, it follows that the exogenous variables have predictive relevance for the endogenous ones [69].

4. Discussion

The main objective of this research was to analyze the intention of students to pursue a sales career in the business-to-business sector under special conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic with physically distanced behavior and orientation towards digital communication. The combination of general factors influencing salespeople’s behavior with specific factors characteristic of health-related crises has not been extensively addressed in the academic literature. The present paper brings together social, individual, and environmental factors that influence students in choosing a sales profession in the business-to-business sector.

The findings emphasized the complex role of motivations in young people’s decision to pursue a career in sales, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (or any other crisis involving risks of direct human-to-human contact) and the growing importance of digital skills. First, our findings support the idea that intrinsic motivation—achieving personal goals and feeling in control of one’s work—significantly increases the perceived attractiveness of a career in sales. The alignment of individual values with the goals associated with the sales role underlines the relevance of intrinsic factors in career decisions and marks a shift away from the traditional focus on financial incentives [7]. This result suggests that the meaningful aspects and personal satisfaction offered by this field should be emphasized in order to encourage more young people to choose a particular profession. This is in line with the protean career model and emphasizes the idea that today’s workforce, especially the younger generations, seek roles that align with their personal and professional identity [14]. This finding supports the overarching goal of the research, which aims to identify the factors that determine career intentions and suggests that personal satisfaction and the desire for personal growth can directly influence career choice.

In addition, social motivation also contributes significantly to the attractiveness of a sales career. This highlights the finding that young people are not only focused on individual achievement but also desire connection and collaboration with others [88]. Furthermore, the role of social influences—particularly family and social environment [23]—is very important for positive perceptions of sales careers. Young people may be more inclined to pursue career paths that are recommended to them by their social networks (a finding consistent with Arief et al. [89]), especially if they are successful in such careers. The results thus coincide with studies that emphasize the key role of parents in career choice in general [90] or in specific areas [78,79], the role of friends [78], or social media [91]. In this way, social support has a significant impact on career intentions. This result is important for the general purpose of the study as it confirms the idea that career decisions are not only influenced by personal motives but also by social factors. This finding suggests that the individual’s family and social networks should be included to encourage interest in certain careers.

These findings are consistent with those of Miao, Evans, and Zou [92], who claim that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations influence salespeople’s performance. Moreover, individuals who are motivated by intrinsic rewards tend to be more adaptive sellers, which enables them to effectively adapt to customers’ needs [93]. The fact that intrinsic motivations are more pronounced in salespeople than extrinsic motivations is a peculiarity of Western cultures, which are considered achievement-oriented, as opposed to Eastern cultures, which are considered relationship-oriented [72].

The COVID-19 pandemic posed major challenges for employees in adapting their activities to the restrictions imposed by the authorities. For salespeople, these restrictions were felt with greater emphasis as face-to-face meetings are more effective when it comes to persuading and closing deals. The direct influence of fear of COVID-19 on the intention to work in sales was found to be insignificant. These findings are partially in line with Tuan [94], who claims that the resilience of business-to-business salespeople during the COVID-19 pandemic is influenced by the sales management’s crisis communication on aspects of the company’s crisis policy (e.g., social distancing). In the current study, the willingness to physically distance serves as a mediator. The propensity for greater distancing correlates with a lower intention to pursue a career in sales, suggesting an indirect pathway through which health concerns limit traditional sales interactions.

Empathy is a variable that is mentioned in a number of articles in the field of sales force effectiveness. Many of them claim a positive influence on the performance of salespeople [30], on their customer orientation [95], or on customer trust and satisfaction with the salesperson [96]. Contrary to expectations, empathic personality traits had no effect on the likelihood that students would choose a career in sales. One possible reason why empathy had no impact on career intentions could be related to the increasingly digital nature of sales work. Face-to-face interactions are limited, and empathy, which is an essential element of face-to-face interactions, may no longer have the same impact on perceptions of the attractiveness of a career in sales. The results are consistent with Dawson et al. [97] and McBane [76], who claim that there is not a positive direct relationship between salespeople’s empathy and their sales performance. Furthermore, Lamont and Lundstrom [98] state that in business-to-business, empathy negatively affects salesperson performance, i.e., a successful industrial salesperson is “not overly sensitive or perceptive to the reactions and feelings of others” (p. 525). This finding raises questions about the traditional view of sales roles that rely heavily on empathy and understanding. It may suggest that today’s view of selling has changed to focus less on emotional relationships and more on transactional skills and results.

Furthermore, our findings highlight the critical role of digital capabilities. As sales increasingly shift to digital platforms, potential employees with strong digital skills find the role of salesperson more attractive, indicating an alignment with a digital sales model.

Although the data collection took place in 2021, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on career intentions is still relevant in the post-pandemic era. The pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation in sales, prompting companies to rapidly adopt digital technologies to maintain operations and customer relationships. This phenomenon has led to a significant shift in the way sales interactions are conducted, moving away from face-to-face meetings to digital platforms and virtual communication. According to a McKinsey report [58], companies have accelerated the digitization of customer interactions and internal processes three to four years earlier than expected.

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of flexibility and adaptability in the workplace. Many companies have introduced hybrid working models, combining remote working with physical presence in the office to meet the needs of employees and maintain productivity. A study by Willis Towers Watson [59] highlights that a proactive hybrid working strategy allows employers to rethink how and where work is done, focusing on the employee experience, which can increase engagement and productivity.

The pandemic has also accelerated the digital transformation of the economy, prompting businesses to rapidly adopt digital technologies to maintain operations and customer relationships. According to a report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the pandemic has led to a significant increase in e-commerce and an acceleration of digital transformation [60].

In addition, the pandemic has prompted companies to rethink their sales strategies and shift from face-to-face meetings to virtual sales and digital self-service platforms. This shift has been well received by customers. They demand that these new forms of interaction remain in place for the long term and are likely to reward providers that implement them well [99].

In conclusion, the results obtained show that internal motivations, social influences, and the perception of career attractiveness play a decisive role in career intention. Furthermore, the results underline the importance of contextual influences, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on career decisions. These results provide a clear answer to the main research question and show that both personal and contextual factors influence the decision to pursue a career in a particular field.

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Practical Implications

Using McClelland’s three needs theory, the study creates a framework for understanding the intrinsic and social motivators that might attract young people to a career in sales, as well as the alignment of personal values and professional goals that contribute to the attractiveness of working in this field. The fact that empathy had no significant impact on career intentions is a valuable finding as it shows that other factors can outweigh emotional abilities. This finding paves the way for future research on the influence of empathy in sales careers and, more generally, in digital environments.

Furthermore, the analysis points to the changing context of the sales profession, characterized by digital skills and changing methods of customer interaction that have emerged as a result of the pandemic. The research suggests that while the fear of COVID-19 indirectly influences career intentions through distancing behavior, it does not directly influence the willingness to pursue a career in sales.

Remarkably, the moderating effect of digital skills emphasizes that these skills could strengthen the association between career attractiveness and intention to work in sales.

Our model has high explanatory power, as the coefficient of determination is 0.72, with the greatest influence on the intention to pursue a sales career belonging to the attractiveness of a sales career (β = 0.662). Similarly, Inks and Avila [100] explained high school students’ intention to pursue a B2B sales career by considering variables such as perception of the sales profession, sales knowledge, and perception of salespeople. The results show a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.3, which is much lower than that of the present study.

These findings could have several implications. For example, the study provides employers with new arguments for a new approach to vocational training that focuses not only on technical skills in sales but also emphasizes the development of intrinsic qualities such as emotional intelligence and social skills [101]. These skills can be crucial in creating a positive sales environment that leads to personal success and better interaction with customers, drawing them into a relationship of trust that is necessary for the value co-creation process [31]. Sales organizations should also make a compelling case that the work environment provides opportunities for performance, collaboration, and personal development. Given recent changes in the public perception of health safety, organizations should effectively communicate preventative health measures and integrate digital tools to facilitate this.

Furthermore, the inclusion of digital skills should become a mandatory part of sales training programs, as research suggests that mastery of digital tools increases the attractiveness of sales roles and the intention to fill them. This is in line with current digitalization trends across all industries. Furthermore, digital skills, or at least the desire to develop them, could become a benchmark for recruitment and selection programs, which could increase their effectiveness and significantly reduce the costs associated with sloppy hiring. Future research should also explore how characteristics of digital sales activities (such as the use of online platforms and asymmetric interactions) influence the relevance of empathy.

The findings suggest that educational institutions and career counselors should consider developing programs that match individual motivations with career opportunities in sales. This can help young people understand the benefits and rewards associated with a career in sales, counteracting historical preconceptions about the attractiveness of a career in sales.

With the same goal of breaking down preconceptions about sales careers, the findings suggest that companies could benefit from partnering with academic and business influencers who can positively influence students’ perceptions of sales careers. Given the role that family plays in young people’s perceptions, schools could also initiate meetings with parent organizations (especially in high schools) to talk about their children’s career options, including sales.

The study has some limitations. For example, the survey was conducted using a non-probabilistic sampling method with students from business and technical universities. Although these appear to be the largest nurseries in the field, there is a possibility that the generalizability of the results to other contexts or demographic groups is limited. Future studies could extend the sample to other educational institutions. Furthermore, the study did not capture how motivational factors and career intentions develop after graduation. This would require a longitudinal study to confirm or not the findings of this research.

While extrinsic motivators are undoubtedly important in the context of career decisions, they are beyond the scope of the present analysis. Future research could further investigate the influence of financial incentives and other extrinsic motivators on career intentions in sales to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence career choice.

Similarly, although digital skills were selected as a key moderating variable in this study, other potential moderators, such as career counseling and institutional support, may also influence students’ career intentions. These variables have the potential to influence students’ perceptions of the attractiveness of a sales career by providing guidance, mentorship, and access to information, all of which can influence career-related decisions. Future research could examine the influence of these moderators to further deepen theoretical and practical understanding of sales career decisions.

The results of hypotheses H8 and H8a show that although the relationships between fear of COVID-19 and the desire for physical distancing are supported by statistical data, the coefficients associated with these relationships are below 0.1. This suggests that the practical impact of these variables is limited. However, given the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, these results are theoretically relevant as they show that the effects of pandemic-related perceptions on career decisions are present, albeit small. Therefore, these findings contribute to the literature by providing empirical evidence of the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on career intentions, a direction that has only been partially explored in previous research.

Despite these limitations, we believe that their identification serves primarily to highlight new research directions that should be based on these findings and does not detract from the value of the insights gained about the factors that influence young people’s interest in sales careers in the context of today’s challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-E.Ț. and D.-M.V.; methodology, D.-M.V.; formal analysis, D.-M.V. and L.-D.A.; investigation, C.-E.Ț. and V.D.; data curation, D.-M.V.; writing-original draft preparation, C.-E.Ț., D.-M.V., L.-D.A. and V.D.; writing-review and editing, C.-E.Ț. and V.D.; visualization, V.D.; supervision, C.-E.Ț. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available by request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ab Hamid, S.N.; Rosli, N.; Abdul Hamid, R.; Che Wel, C.A. The influence of job characteristics toward intention to pursue sales career mediated by feelings. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 953645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballestra, L.V.; Cardinali, S.; Palanga, P.; Pacelli, G. The Changing Role of Salespeople and the Unchanging Feeling toward Selling: Implications for the HEI Programs. J. Mark. Educ. 2017, 39, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconescu, V. What is the perception of economics students about a career in sales. Cactus Tour. J. 2019, 1, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti, M.; Sharma, A.; Rangarajan, D.; Cardinali, S.; Cedrola, E. Understanding the enduring shifts in sales strategy and processes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2024, 39, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesalaga, R.; Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; López-Tenorio, P.J. Drivers of business-to-business sales success and the role of digitalization after COVID-19 disruptions. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2024, 39, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusainova, R.; De Jong, A.; Lee, N.; Marshall, G.W.; Rudd, J.M. (Re)defining salesperson motivation: Current status, main challenges, and research directions. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2018, 38, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, V.; Hughes, D.E.; Wang, H. More than money: Establishing the importance of a sense of purpose for salespeople. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 272–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiyati, M.A.; Astuti, B. Student Careers: What Factors Influence Career Choice? J. Educ. Res. Eval. 2023, 7, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C. The Achieving Society; Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- French, P.E.; Emerson, M.C. One Size Does Not Fit All: Matching the Reward to the Employee’s Motivational Needs. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2015, 35, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Burrus, J. Predicting STEM Major and Career Intentions with the Theory of Planned Behavior. Career Dev. Q. 2019, 67, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.E.; Ogilvie, J.L. When sales becomes service: The evolution of the professional selling role and an organic model of frontline ambidexterity. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T. The protean career: A quarter-century journey. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Koen, J. Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Silva, L.C.; Barreiros Porto, J.; Arnold, J. Professional fulfillment: Concept and instrument proposition. Psico USF 2019, 24, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, B.; Shanka, T.; Rabbanee, F.K. From resentment to excitement—Australasian students’ perception towards a sales career. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 1178–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Belschak, F.; Verbeke, W. The role of emotional wisdom in salesperson’s relationships with colleagues and customers. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 1001–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, I.; Tsarenko, Y.; Wagstaff, P.; Powell, I.; Steel, M.; Brace-Govan, J. The development of competent marketing professionals. J. Mark. Educ. 2009, 31, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.; Bush, V.; Oakley, J.; Cicala, J. Formulating undergraduate student expectations for better career development in sales: A socialization perspective. J. Mark. Educ. 2014, 36, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butaney, G.T. A Commentary on “Undergraduate Education: The Implications of Cross-Functional Relationships in Business Marketing–The Skills of High-Performing Managers”. J. Bus.-Bus. Mark. 2007, 14, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.W.; Borgonovi, F.; Guerriero, S. What motivates high school students to want to be teachers? The role of salary, working conditions, and societal evaluations about occupations in a comparative perspective. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 55, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, F.; Quigley, C.; Bingham, F. A cross-national investigation of student intentions to pursue a sales career. J. Mark. Educ. 2011, 33, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillan, J.E.; Totten, J.W.; Ziemnowicz, C. What are students’ perceptions of personal selling as a career? J. Adv. Mark. Educ. 2007, 11, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.; Kubik, M.; King, A.; Weidman, G. Intention to Pursue a Sales Career: A Dyadic Study of Students and Parents Extended Abstract. Assoc. Mark. Theory Pract. Proc. 2022, 34. Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/amtp-proceedings_2022/34 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Leary, M.R.; Kelly, K.M.; Cottrell, C.M.; Schreindorfer, L.S. Construct validity of the Need to Belong Scale: Mapping the nomological network. J. Pers. Assess. 2013, 95, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastal, C.A.; Pilati, R. The Need to Belong Scale: Adaptation and Evidences of Validity. Psico-USF 2016, 21, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, M.C.; Schwepker, C. Empathy and political skill: Improving salespeople’s value enhancing behavior performance. J. Appl. Mark. Theory 2024, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Khalid, A.; Saeed, M.; Shafique, S.; Babalola, M.T.; Ren, S. Invigorating the spirit of being adaptive: Examining the role of spiritual leadership in adaptive selling. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 177, 114648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locander, D.A.; Locander, J.A.; Weinberg, F.J. How salesperson traits and intuitive judgments influence adaptive selling: A sensemaking perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 18, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A.; Inyang, A.E.; Saavedra, J.L. Empathy and affect in B2B salesperson performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpechitre, D.; Rutherford, B.N.; Comer, L.B. The importance of customer’s perception of salesperson’s empathy in selling. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, P.; Shao, J. A study of the mechanism of the types of emotions in retailers’ review request text on consumers’ reviewing intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 36, 1464–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supramaniam, S.; John, S.P.; Gaur, S.S. The Role of Sales Personnel Empathy and Customer-oriented Behaviour on Female Consumers’ Emotions and Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2024. Available online: https://04115tjo7-y-https-doi-org.z.e-nformation.ro/10.1177/23197145241241956 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Corsaro, D.; D’Amico, V. How the digital transformation from COVID-19 affected the relational approaches in B2B. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 2095–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan, D.; Sharma, A.; Lyngdoh, T.; Paesbrugghe, B. B2B selling in the post COVID era: Developing an adaptive salesforce. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Adhikary, A.; Borah, S.B. Covid19’s impact on supply chain decisions: Strategic insights from NASDAQ 100 firms using Twitter data. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Hamori, M. Adapting careers to the COVID crisis: The impact of the pandemic on employees’ career orientations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 139, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abessolo, M.; Hirschi, A.; Rossier, J. Development and validation of a multidimensional career values questionnaire: A measure integrating work values, career orientations, and career anchors. J. Career Dev. 2021, 48, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Hai, S. How does career future time perspective moderate in the relationship between infection anxiety with the COVID-19 and service behavior among hotel employees? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Park, J.; Hyun, S.S. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on employees’ work stress, well-being, mental health, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee-customer identification. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabawaningrum, A.B.; Nurdiyanto, F.A.; Putri, A.B.; Harjanti, E.P. Student career anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: A phenomenological exploration. Humanit. Indones. Psychol. J. 2023, 20, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.H.; Kinnunen, M. Reminiscence and wellbeing—Reflecting on past festival experiences during COVID lockdowns. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2024, 15, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K.I.; Jacobsen, M.H.; Wilson, J.L. Nostalgia and the Corona Pandemic: A Tranquil Feeling in a Fearful World. In The Emerald Handbook of the Sociology of Emotions for a Post-Pandemic World; Ward, P.R., Foley, K., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybema, S. Managerial postalgia: Projecting a golden future. J. Manag. Psychol. 2004, 19, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- MacNeil, S.; Deschênes, S.; Knäuper, B.; Carrese-Chacra, E.; Dialahy, I.Z.; Suh, S.; Durif, F.; Gouin, J.P. Group-based trajectories and predictors of adherence to physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 1492–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unver, B.; Temeloğlu Şen, E.; Öner Gücin, N. Development and Validation of the Physical Distancing Behavior Scale: A Study Based on the Integrated Behavior Model. Psikiyatr. Güncel Yaklaşımlar—Curr. Approaches Psychiatry 2023, 15 (Suppl. S1), 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Smith, S.R.; Keech, J.J.; Moyers, S.A.; Hamilton, K. Predicting physical distancing over time during COVID-19: Testing an integrated model. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 1436–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, E.; McGregor, I.; Klackl, J.; Agroskin, D.; Fritsche, I.; Holbrook, C.; Nash, K.; Proulx, T.; Quirin, M. Threat and defense: From anxiety to approach. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Olsen, J.M., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 49, pp. 219–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivett, V.J.; Maranges, H.M.; March, D.S. The unique roles of threat perception and misinformation accuracy judgments in the relationship between political orientation and COVID-19 health behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteegt, L.; van Dijke, M.; van den Bos, K. Physical distancing during the COVID-19 crisis: The roles of threat and moralization. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 54, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M. Emotional labor in a sales ecosystem: A salesperson-customer interactional framework. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 666–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Guo, Y. Influence of tourists’ well-being in the post-COVID-19 era: Moderating effect of physical distancing. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Schaik, L.; Duives, D.; Hoogendoorn-Lanser, S.; Hoekstra, J.W.; Daamen, W.; Gavriilidou, A.; Krishnakumari, P.; Rinaldi, M.; Hoogendoorn, S. Understanding physical distancing compliance behaviour using proximity and survey data: A case study in The Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transp. Res. Proc. 2024, 76, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, S.; Damghanian, H.; Farhadinejad, M.; Rastgar, A.A. Meta-analysis on application of Protection Motivation Theory in preventive behaviors against COVID-19. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grano, C.; Singh Solorzano, C.; Di Pucchio, A. Predictors of protective behaviours during the Italian COVID-19 pandemic: An application of protection motivation theory. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 1584–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habel, J.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Hartmann, N.; de Jong, A.; Zacharias, N.A.; Kosse, F. Neuroticism and the Sales Profession. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2024, 184, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey; Company. How COVID-19 Has Pushed Companies over the Technology Tipping Point—And Transformed Business Forever. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Willis Towers Watson. 10 Trends That Will Affect the Workplace Post-Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.wtwco.com/en-us/insights/2021/10/10-trends-that-will-affect-the-workplace-post-pandemic (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- UNCTAD. How COVID-19 Triggered the Digital and E-Commerce Turning Point. 2021. Available online: https://unctad.org/news/how-covid-19-triggered-digital-and-e-commerce-turning-point (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Calixto, N.; Ferreira, J. Salespeople Performance Evaluation with Predictive Analytics in B2B. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Atefi, Y.; Lam, S.K.; Pourmasoudi, M. The future of buyer–seller interactions: A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J. Essentials of Marketing Research, 4th ed.; South-Western Centage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, A.C.; Bush, R.F. Marketing Research, 7th ed.; Pearson/PrenticeHall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, M.A.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J.; Thurasamy, R.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Sample Size for Survey Research: Review and Recommendations. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2020, 4, i-xx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Nunan, D.; Birks, D.F.; Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: Applied Insight, 6th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pullins, E.B. An exploratory investigation of the relationship of sales force compensation and intrinsic motivation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, D.W.; Ingram, T.N.; LaForge, R.W.; Young, C.E. Behavior-based and outcome-based salesforce control systems. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, C.R.; Leasher, M. Examining the differences in salesperson motivation among different cultures. Am. J. Bus. 2011, 26, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlamäki, T.; Storbacka, K.; Pylkkönen, S.; Ojala, M. Adoption of digital sales force automation tools in supply chain: Customers’ acceptance of sales configurators. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 91, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D.; Raichel, N. Enhancing perceived digital literacy skills and creative self-concept through gamified learning environments: Insights from a longitudinal study. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 101, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.N.; Lussier, B. Managing the sales force through the unexpected exogenous COVID-19 crisis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBane, D.A. Empathy and the salesperson: A multidimensional perspective. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Jayachandran, C.; Babin, B.J.; Peterson, R.T. Empathy, nonverbal immediacy, and salesperson performance: The mediating role of adaptive selling behavior. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalci, I.; Ozyapici, H. Cultural values and students’ intentions of choosing accounting career. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2018, 16, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adya, M.; Kaiser, K.M. Early determinants of women in the IT workforce: A model of girls’ career choices. Inf. Technol. People 2005, 18, 230–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.; Lin, C.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.; Pakpour, A. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorca, M.; Martínez-Lorca, A.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Armesilla, M.D.C.; Latorre, J.M. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Validation in spanish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nockur, L.; Böhm, R.; Sassenrath, C.; Petersen, M.B. The emotional path to action: Empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltier, J.W.; Cummins, S.; Pomirleanu, N.; Cross, J.C.; Simon, R. A parsimonious instrument for predicting students’ intent to pursue a sales career. J. Mark. Educ. 2014, 36, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: A comparison of four procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowlin, E.L.; Walker, D.; Anaza, N.A. How does salesperson connectedness impact performance? It depends upon the level of internal volatility. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 68, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, N.N.; Gregory, A.; Pangestu, A.B.; Ramdlany, D.M.A.; Sanjaya, I.M.A. Employee influencer management: Evidence from state-owned enterprises in Indonesia. J. Commun. Manag. 2022, 26, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wong, C.-S. Theorizing parental intervention and young adults’ career development: A social influence perspective. Career Dev. Int. 2020, 25, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.T.; Wong, S.C.; Lim, C.S. Predictive modeling of career choices among fresh graduates: Application of model selection approach. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2023, 16, 1799–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.F.; Evans, K.R.; Zou, S. The role of salesperson motivation in sales control systems—Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation revisited. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz, B.A.; Sujan, H.; Sujan, M. Knowledge, motivation, and adaptive behavior: A framework for improving selling effectiveness. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Leader crisis communication and salesperson resilience in face of the COVID-19: The roles of positive stress mindset, core beliefs challenge, and family strain. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmier, S. The effects of incentives and personality on salesperson’s customer orientation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Castleberry, S.B.; Ridnour, R.; Shepherd, C.D. Salesperson empathy and listening: Impact on relationship outcomes. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2005, 13, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.E.; Soper, B.; Pettijohn, C.E. The effects of empathy on salesperson effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 1992, 9, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, L.M.; Lundstrom, W.J. Identifying successful industrial salesmen by personality and personal characteristics. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. How COVID-19 Has Changed B2B Sales Forever. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/these-eight-charts-show-how-covid-19-has-changed-b2b-sales-forever (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Inks, S.A.; Avila, R.A. An Examination of High Schools Students’ Perceptions of Sales as an Area to Study in College, and Factors Influencing their Interest in Sales as a Career to Pursue after College. J. Mark. Educ. 2018, 40, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, B. The work of sales representatives in the context of interactions and work with emotions. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 16, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).