1. Introduction

The platform economy defines the organizational structure of the digital economy, which fosters the creation of new digital economic models and scenarios, and serves as a catalyst and propeller for the advancement of the digital economy. While the platform economy fosters the swift expansion of the digital economy and enables its considerable affluence, it also introduces novel social risks. Characterized by diverse participating entities, extensive transaction data, information disparities between online and offline sectors, and unique network externalities, the platform economy manifests market failure in distinctive ways. Issues such as the widespread existence of counterfeit and low-quality products, cyber-industrial crime, and the adverse effects of “big data” on growth have also become more prevalent [

1,

2]. These difficulties pose new challenges to the regulatory framework of the digital economy and the platform economy. This presents novel problems to the regulatory framework of the digital economy and platform economy.

By the end of 2023, the cumulative valuation of Chinese digital platform enterprises surpasses US

$6 trillion, encompassing approximately 279 enterprises with a market value exceeding US

$1 billion [

3]. Platform enterprises have experienced a significant increase in their growth rate, both in terms of size and quantity. The exponential growth of the platform economy has introduced novel complexities in its social governance and regulation, particularly the widespread occurrence of counterfeit and substandard products, cyber-industry crimes, the detrimental impact of “big data” maturation, and other related concerns. Managing data competition among platform enterprises, addressing platform monopoly, and defining the social responsibility of platform enterprises present highly intricate and delicate challenges.

In 2021, China’s platform economy saw the implementation of “stringent regulation” policies, which was prompted by the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (“CPC”) and the Central Economic Work Conference (“CEWC”) held in December 2020. These events explicitly emphasized the importance of “strengthening anti-monopoly measures and preventing uncontrolled capital expansion”, leading to the issuance of a mandate for rigorous regulation. The December 2020 Political Conference of the CPC Central Committee and the Central Economic Work Conference both emphasized the importance of “enhancing measures against monopolies and curbing the unchecked growth of capital”, issuing a directive for “rigorous regulation”. The year 2021 saw a succession of laws and regulations on data protection, anti-monopoly, anti-unfair competition, and workers’ rights and interests issued by several governmental departments [

4]. General Secretary Xi Jinping underscored the importance of maintaining a balance between promoting development and implementing regulations. He highlighted the need to regulate and standardize development activities, while also ensuring that regulations are developed in a way that supports further growth. The “Opinions on Promoting the Standardized, Healthy and Sustainable Development of the Platform Economy” was jointly issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and nine other departments on 19 January 2022. This document stresses the need to establish a robust regulatory framework for the platform economy and ensure its healthy and sustainable growth, in line with the strategic goal of enhancing the country’s competitive advantage. Key strategic focuses, including promoting the high-quality development of the platform economy, and forming a strategic perspective, aim to improve the development environment, strengthen innovation and development capabilities, support economic transformation and development, and establish an effective governance system for the platform economy [

5]. The Opinions hold significant practical importance in promoting the coordination of governance, strengthening sectoral coordination, and adhering to the principle of integrating online and offline supervision. They also aim to enhance collaborative research and decision-making on major issues in the field of the platform economy. It is of great practical significance.

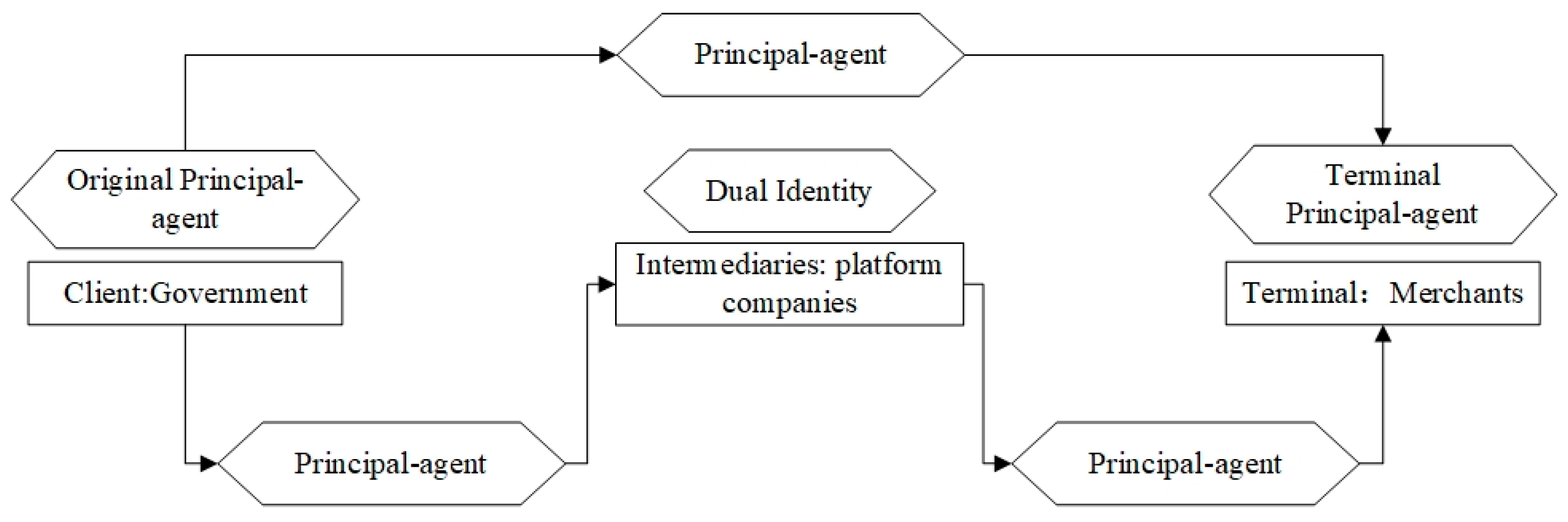

During the regulation of the platform economy, the government aims to ensure fair competition, protect consumer rights, and promote healthy economic development. Platform enterprises, on the other hand, prioritize maximizing profits alongside maintaining platform stability and attractiveness. Merchants, meanwhile, seek to expand their market share and increase their profits. These various interests are the key issues of platform economic governance. Nevertheless, the government may face challenges in comprehending the intricacies of platform enterprises and merchants’ operations and behaviors. Conversely, platform enterprises and merchants possess a greater amount of confidential information. This imbalance in information may impede the government’s ability to regulate and control platform enterprises and merchants effectively. Additionally, it may lead to platform enterprises and merchants prioritizing their own interests over the public welfare and other stakeholders. The principal–agent theory can elucidate the conflict of interest and information asymmetry between the government, platform enterprises, and merchants in the governance of platform economics.

Currently, there is significant academic interest in incentivizing platform economic regulation and conducting a quantitative analysis of incentives in platform economic regulation from many levels and perspectives. Early related studies focused on the pricing issues of platform enterprises. Subsequently, research delved into an analysis of the economic governance platform, focusing on its substance, the entities responsible for governance, the model of governance, and the establishment of the governance system.

1.1. Research Related to the Governance Content of the Platform Economy

In today’s digital era, the rise of the platform economy has significantly reshaped production, consumption, and social interaction. However, the rapid growth of the platform economy has sparked extensive discussions on governance issues as well. The most central and highly debated issues include antitrust concerns [

6,

7], pricing mechanisms [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], and the protection of user rights in the context of big data [

7,

13,

14].

First, regarding the anti-monopoly debate, the issue of monopolization in the platform economy has garnered significant attention. In a competitive economy, the maximum total consumer surplus and total social welfare are expected to be achieved with the consideration of personal information protection and first-degree pricing discrimination. Nevertheless, the prohibition of price discrimination can result in an inefficient product distribution, highlighting the intricate interplay between market competition and the protection of individual rights [

15,

16,

17]. Prior research has supported the idea that technological advancement and innovative business models might not always align with the market. It has been predicted that, under certain circumstances, the market will develop a competitive monopoly structure known as a mono-oligopoly. This highlights the significance of antitrust regulation in the platform economy [

18,

19,

20].

Second, pricing strategies also constitute a significant aspect of platform economic governance. The vast public concern has been intensified by the phenomenon known as “big data kills maturity”, where platforms utilize user data to implement tailored pricing. In this study, Yin et al. [

21] (2023) examined the possible conflicts that may arise between the rights of customers and operators of algorithmic discriminating behaviors at various phases. Relevant research has determined that conflicts may arise between operators and consumers regarding information gathering, pushing, and pricing, due to conflicting rights and interests. It emphasizes the necessity of implementing regulations to safeguard consumer rights and interests. To address this phenomenon, Lei et al. [

22] (2021) and Wu et al. [

23] (2020) established an evolutionary game model and a prospective benefit perception matrix, respectively, to deeply analyze the decision-making mechanism and regulatory mechanism of the “familiarization” behavior of e-commerce platforms, which provides an important reference for policy formulation.

Although antitrust and pricing methods are crucial components of platform economy governance, Denyer [

24] (2023) posited that a comprehensive understanding and resolution of the difficulties presented by the platform economy require more than just these two conventional viewpoints. The convergence of fintech and network economics, exemplified by prominent Internet platforms, constitutes a novel approach to social production and the organization of daily life. Hence, it is imperative to transcend the conventional anti-monopoly viewpoint and delve into the effective governance of the platform economy from a more comprehensive standpoint.

1.2. Research on Platform Economic Governance

Prior research on platform economic governance has primarily focused on the collaborative and interdependent connection among the government, platforms, users, third parties, customers, and various other entities involved in platform governance. Li et al. [

25] (2023) and Doellgast et al. [

26] (2023) examined the issues such as the degree of discriminatory pricing, acknowledgment of data rights, likelihood of social exposure, and government oversight. An evolutionary game model of “merchant–platform e-commerce–government” was constructed to investigate the collaborative governance approach of the government, enterprise, and consumer in platform e-commerce. The model aimed to examine the connection between government, enterprises, and consumers. In their study, Wang et al. [

27] (2020) examined the underlying “regulatory dilemma” associated with credit in platform e-commerce. They accomplished this by developing an evolutionary game model of the “merchant–platform e-commerce–government” system. The inherent “regulatory dilemma” in platform e-commerce credit was analyzed by creating an evolutionary game model of “merchant–platform e-commerce–government”. Wang et al. [

28] (2022) examined consumer complaints and developed a four-party evolutionary game model that incorporates the government, e-commerce platforms, merchants, and consumers to analyze the strategic decisions made by each party. In a groundbreaking study, Xu et al. [

29] (2024) developed a novel UCIP “multi-actor co-regulation” framework that involves active involvement from the government, industry associations, and platform users. Ma et al. [

30] (2023) studied the small-scale interactions between individuals and the key factors that influence the evolution process. They developed a four-party evolution game model consisting of super platforms, existing platforms, entrepreneurial platforms, and governmental regulators to investigate the evolution mechanism of the duopoly.

Furthermore, some scholars have argued that the central aspect of platform governance revolves around the collaboration between government and platform enterprises. They proposed that a dual cooperative governance model, combining “government regulation + industry self-regulation,” is the most effective approach to governing cyberspace. According to Nan et al. [

31] (2023), Li et al. [

32] (2018), Guo et al. [

33] (2019), and Lu et al. [

34] (2023), they emphasized the complementary and supportive nature of government regulation and platform self-regulation. Guo et al. [

33] (2019) also incorporated the concepts of dynamic balance and structural balance, along with the three regulatory approaches of ex-ante, ex-post, and ex-post. Guo et al. [

33] (2019) integrated the concepts of dynamic equilibrium and structural equilibrium, along with three types of regulation: pre-event, during the event, and post-event. Two regulatory strategies were proposed: single-body dynamic equilibrium and dual-body structural equilibrium. Based on this model, a cooperative regulatory framework between the government and platforms was developed [

35,

36].

Currently, there is a lack of validation for quantitative techniques related to principal–agent problems in platform economic governance, despite the existing literature on the subject [

9,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Extensive research revealed that a significant body of literature examined the implications and attributes of platform non-compliance, highlighting the beneficial impact of government regulation on platform economic governance. Additionally, some studies proposed strategies for the development of platform economies, providing a theoretical foundation and policy suggestions for platform economic governance. Nevertheless, there are still certain deficiencies. Initially, a substantial body of literature has extensively discussed the significance of government involvement in regulating platform monopolies, focusing on qualitative aspects and highlighting the insufficiency of current regulatory methods. The consensus is that the government should employ innovative regulatory measures to effectively address the issues of governing platform economies. Quantitatively, the number of economic restrictions on the platform is still rather low. Furthermore, while a few scholars have acknowledged the principal–agent dynamics in platform economic governance, the current study primarily focuses on the agent’s participation constraints and overlooks the principal’s minimum participation constraints. As a result, this oversight can result in a risk of financial loss despite maximizing the principal’s utility and a failure to establish effective incentives for the principal. Existing research on platform governance primarily centers around the development of incentive contracts. This approach viewed the platform enterprise as a risk-averse agent and overlooks the intricate motivations of the medical side to exert effort. Additionally, it failed to acknowledge the platform enterprise’s role as a mediator between the government and merchants.

This paper examines the regulatory incentive problem in the platform economy by analyzing the regulatory incentives of the government, platform enterprises, and merchants. It constructs a dual principal–agent model under conditions of asymmetric information and provides a theoretical foundation for regulating China’s platform economy through the solution and simulation of the dual principal–agent model. The primary advancements are as follows: (1) A dual principal–agent model is created to govern the relationship between the government, platform enterprises, and merchants in platform governance. An optimal contractual mechanism is designed by combining incentive and supervision mechanisms. (2) The role of platform enterprises as both principal and agent is taken into account, and the factors influencing the expected return of platform enterprises are analyzed, which provides theoretical support for the development of collaborative governance involving multiple subjects. (3) A quantitative analysis is conducted to determine the optimal incentives and supervision methods. This study performs a mathematical analysis of the most effective contract structure, taking into account optimal incentives, optimal regulation, and other relevant factors, while examining the different roles that regulatory mechanisms and incentive mechanisms can play.

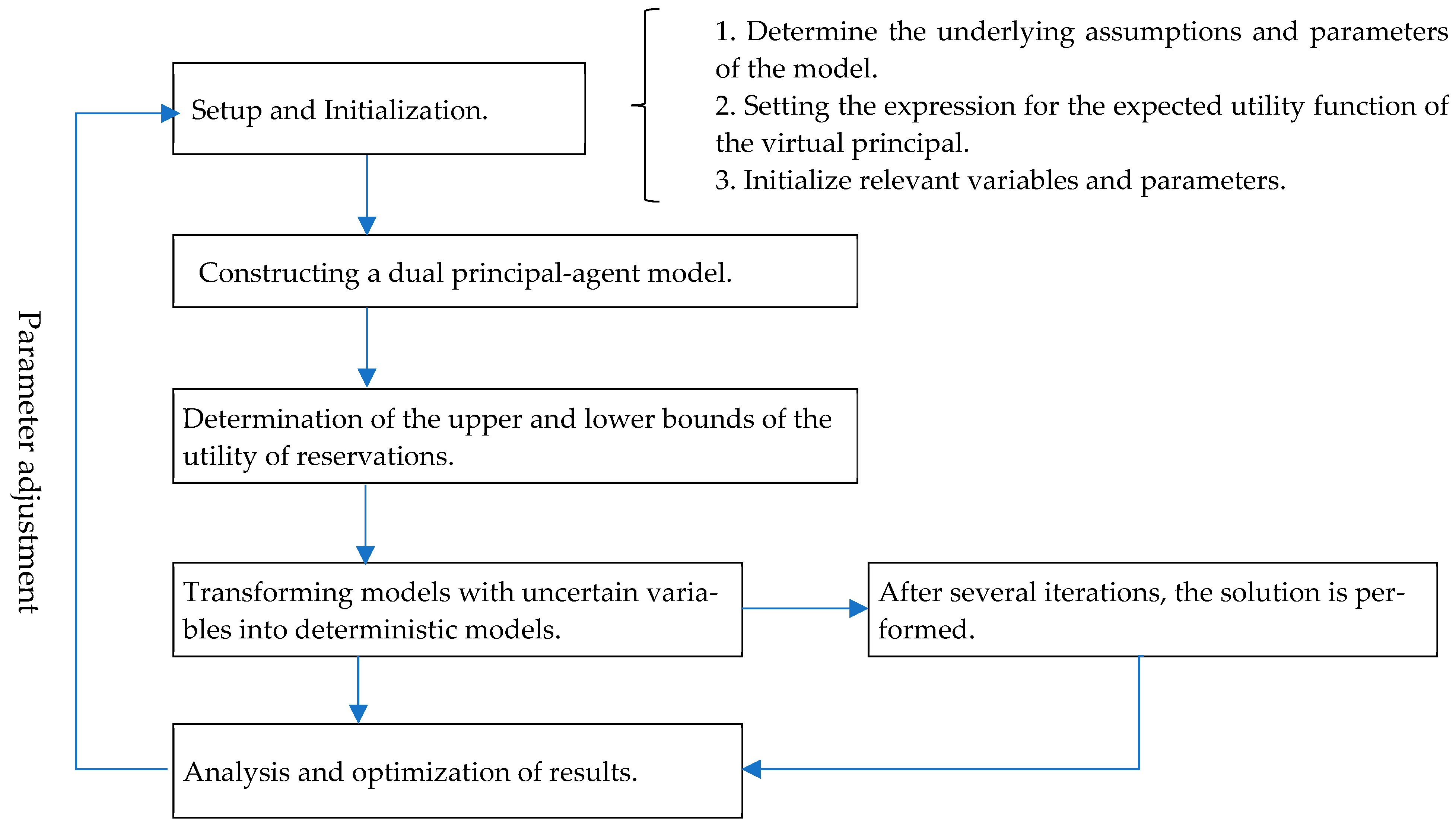

This paper is structured as follows: the first part describes the platform economic regulatory incentives problem and makes assumptions about the model; the second part solves the two-layer principal–agent model; the third part analyzes and discusses the nature and characteristics of the solutions to the two-layer principal–agent model; the fourth part simulates and analyzes the two-layer principal–agent model through simulation; and the fifth (and last) part offers conclusions and recommendations for countermeasures.

5. Numerical Examples and Analysis

Through numerical examples and simulation analysis, this part explores the key parameters and conclusions in order to more intuitively grasp the conclusions of this research and the corresponding model outcomes. For the purpose of this study, we primarily use up-to-date information about how the government regulates platform businesses and merchants, placing it within a realistic framework [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. The base data are taken as follows:

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

. The primary research objectives of the numerical simulation are as follows: (1) the relationship between the government’s incentive intensity

for platform enterprises and their capability coefficient

, their transformation coefficient of social benefits

, their maximum punishment amount

after the government uncovers their speculative behavior, and their effort–cost coefficient

; (2) the relationship between the platform enterprise’s incentive strength

and the merchant’s dependence on it

, as well as the platform enterprise’s incentive strength to the government

, the platform enterprise’s capability coefficient

, the maximum penalty amount that the platform enterprise will impose upon discovering the merchant’s speculative behaviors

, and the merchant’s organizational capability coefficient

; (3) the correlation between the effort level

of the platform enterprise and the coefficient of effort–cost

of the platform enterprise, the coefficient of capability

of the platform enterprise, the intensity of the government’s supervision as

, the coefficient of risk sensitivity

, and the coefficient of transformation of the social benefit

; (4) the correlation between the merchant’s effort level

and the merchant’s organizational capability coefficient

, the government’s incentive strength for the platform enterprise

, the merchant’s dependence on the platform enterprise

, and the merchant’s effort–cost coefficient

; and (5) the correlation between the expected utility

of the platform enterprise and the effort level of the platform enterprise

, the effort level of the merchant

, the transformation coefficient of the social benefit

, and the capability coefficient

of the platform enterprise.

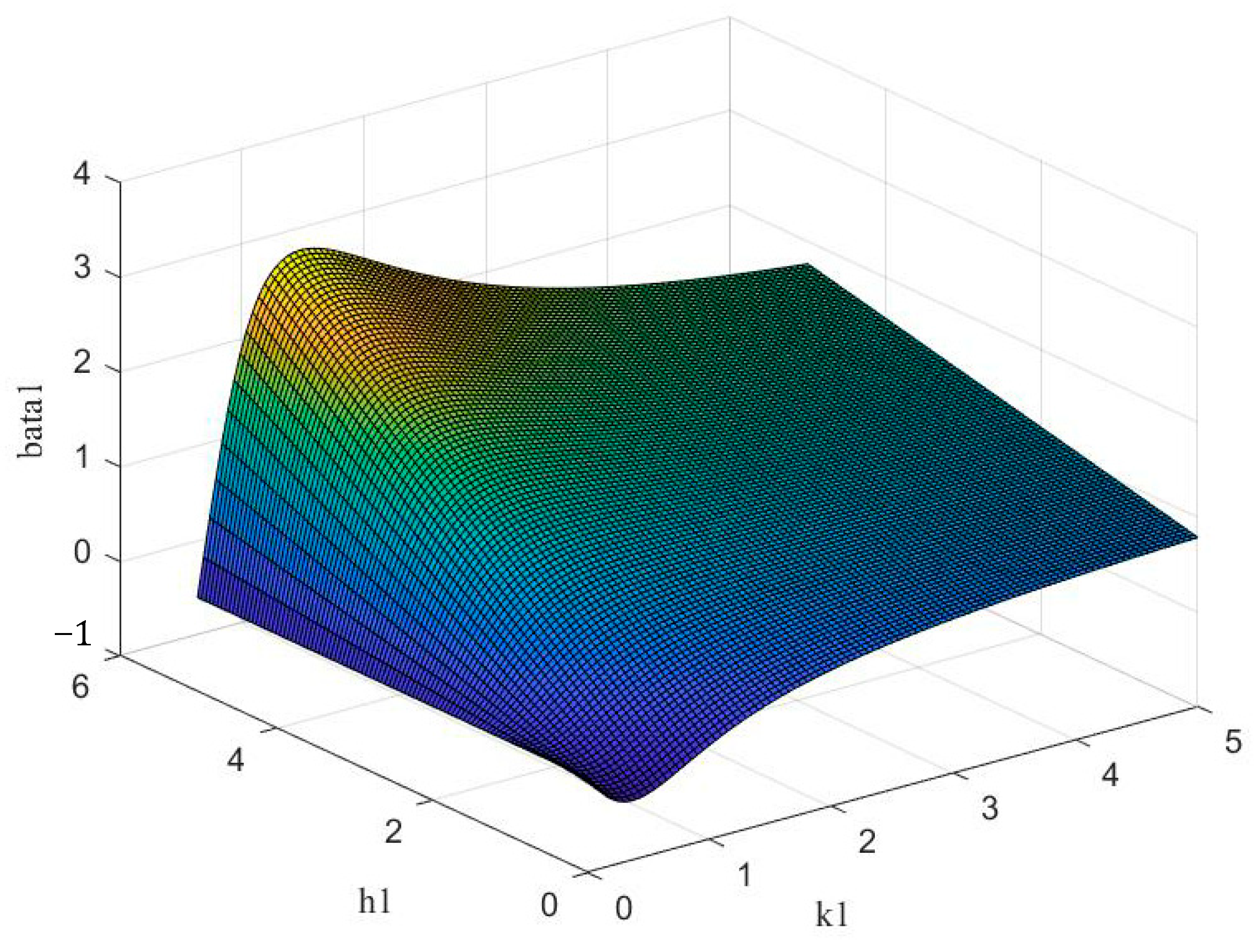

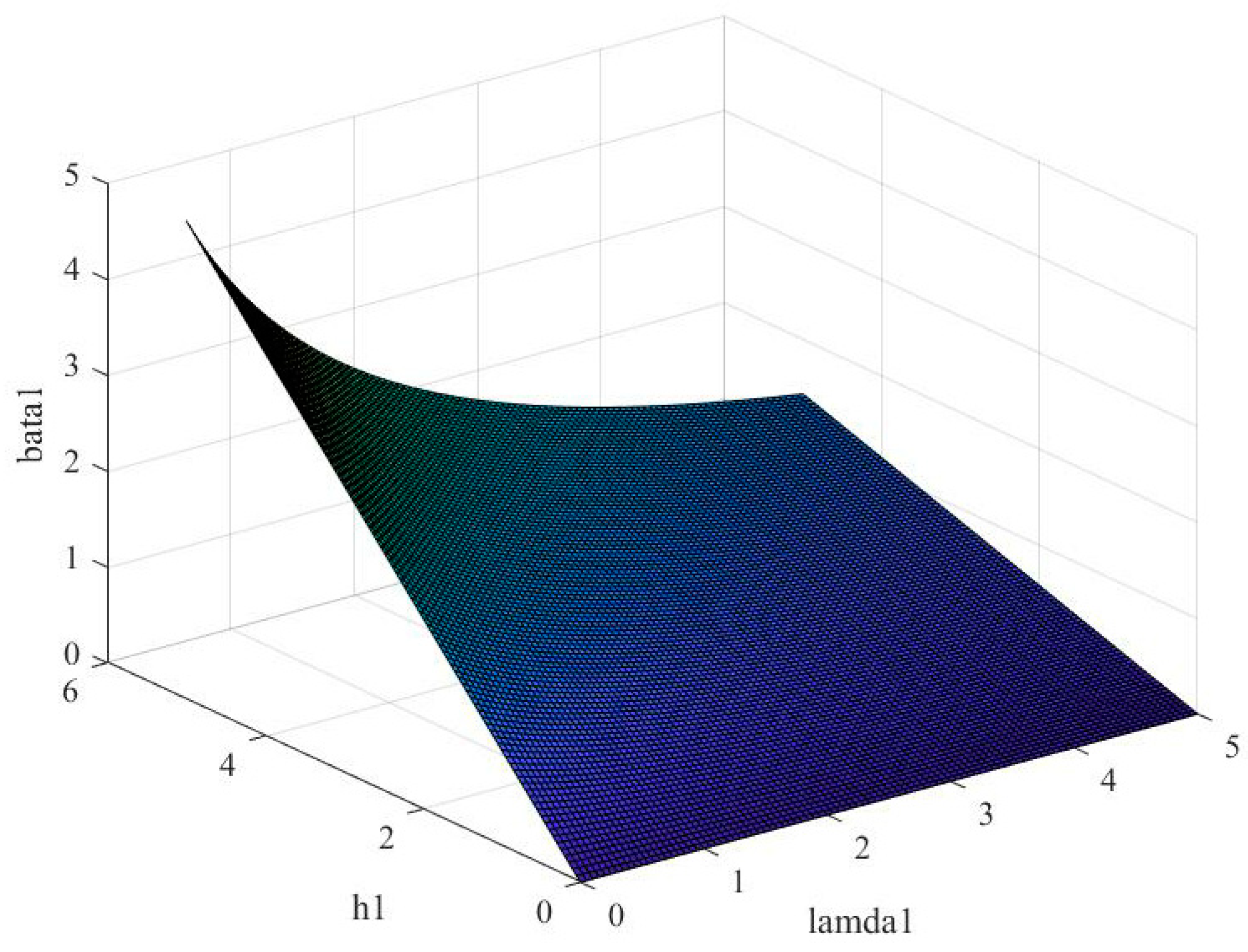

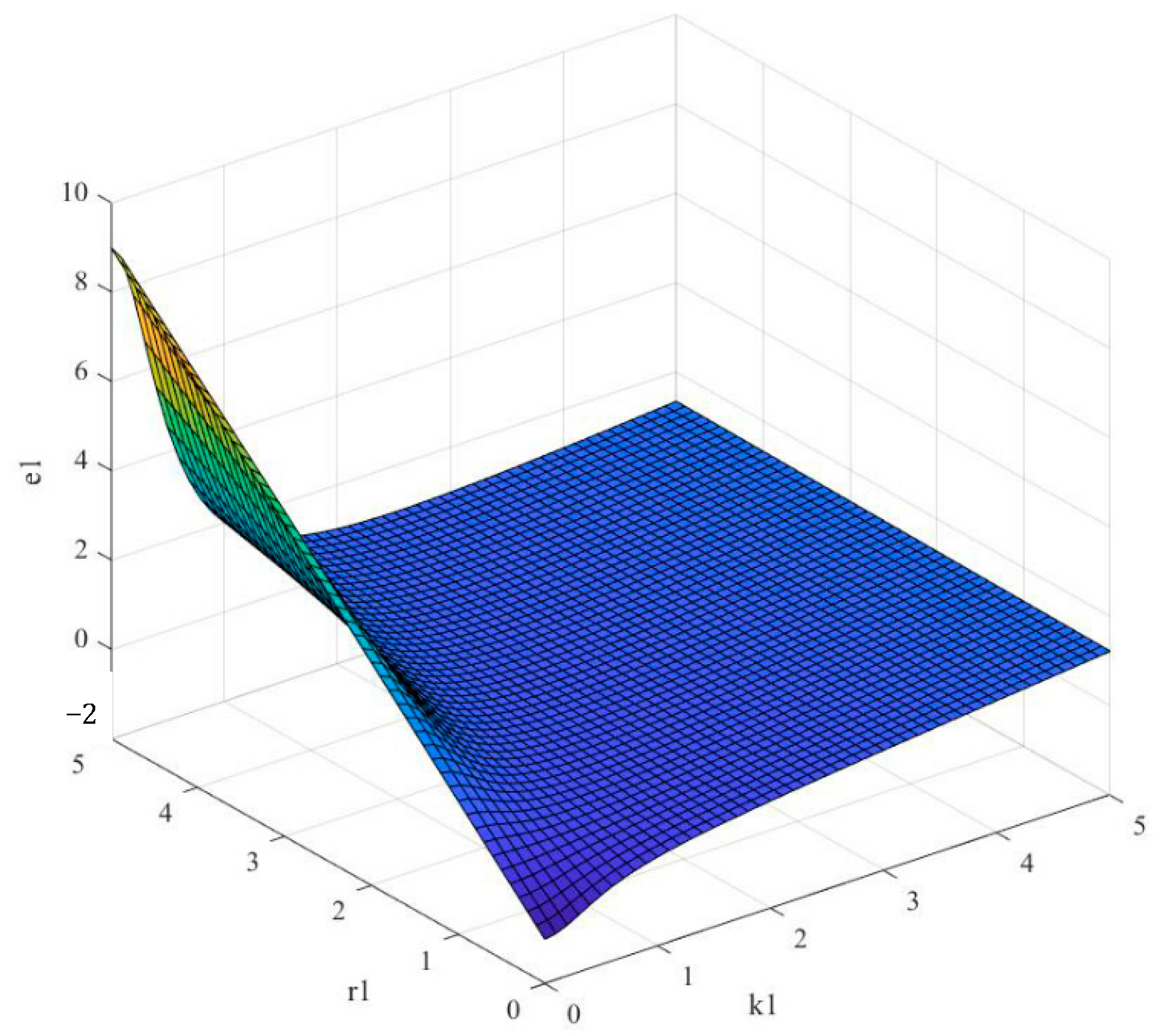

5.1. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Incentive Strength of Platform Companies for Merchants

As the capability coefficient

and the social benefit transformation coefficient

of the platform enterprises vary,

Figure 3 illustrates how the government incentive intensity

exhibits a downward distortion. However, the distortion will continue to decrease as

declines. The government incentive intensity

has a tendency that increases as the social benefit transformation coefficient rises, increases with the platform enterprise’s capability coefficient, and decreases with the latter. This indicates that, in the first place, the government will often boost the incentive intensity to push platform enterprises to enhance their own capabilities—such as technology, service, and management—when their capability coefficient is low. This is due to the fact that platform enterprises require greater resources and assistance in order to expand quickly during their early stages. Nonetheless, the government may suitably lower the incentive intensity when the platform enterprise’s capability steadily strengthens, or as its capability coefficient rises. This is due to the fact that platform businesses already possess a certain level of self-regulation and market competition, and the government’s incentive role is comparatively lessened. Secondly, the social benefit transformation coefficient indicates how much platform enterprise regulation contributes to the social economy. In order to encourage platform enterprise regulation and further expand its social benefit, the government will increase the incentive intensity in proportion to the increase in the social benefit conversion coefficient, which indicates the platform enterprise regulation’s contribution to the social economy. The rationale for the government’s incentive-based approach to platform enterprise regulation is to guarantee that these businesses comply with legal requirements and offer consumers dependable, secure, and superior products and services.

As the government learns about the platform enterprises’ speculative activity,

Figure 4 illustrates how the government incentive intensity

rises with an increase in the social benefit transformation coefficient

but falls with an increase in the maximum punishment

. This pattern suggests that, if the government decides to raise the maximum penalty amount after learning about the platform enterprises’ speculative activity, the government’s incentive intensity will drop in tandem. Put another way, by stiffening the penalties, the government seeks to curtail the speculative actions of platform companies, thus lowering the expenses and hazards associated with regulation. From an economic perspective, stiffer penalties make platform companies’ non-compliance more expensive, which lessens their incentive to act in a speculative manner. As a result, the government does not need to use strong incentives during the regulatory process to entice platform companies to comply. In addition, by stepping up the intensity of incentives, the government pushes platform companies to aggressively carry out their social obligations and increase the scope of their social benefits. This method of thoughtful deliberation supports the robust, orderly, and high-quality growth of the e-commerce sector as a whole as well as the sustained development of platform businesses.

Figure 5 shows that the government incentive intensity

rises when the platform enterprise’s effort–cost coefficient

rises, but increases when the social benefit transformation coefficient

rises. When the platform enterprise’s effort–cost coefficient B rises, the government incentive intensity A falls. In the event that platform enterprises must allocate significant financial, material, and human resources towards countering counterfeit and substandard goods and safeguarding the rights and interests of consumers, and the incentives provided by the government prove insufficient to offset these costs, the platforms may opt to scale back on their efforts to combat these issues, thereby exacerbating speculative behaviors.

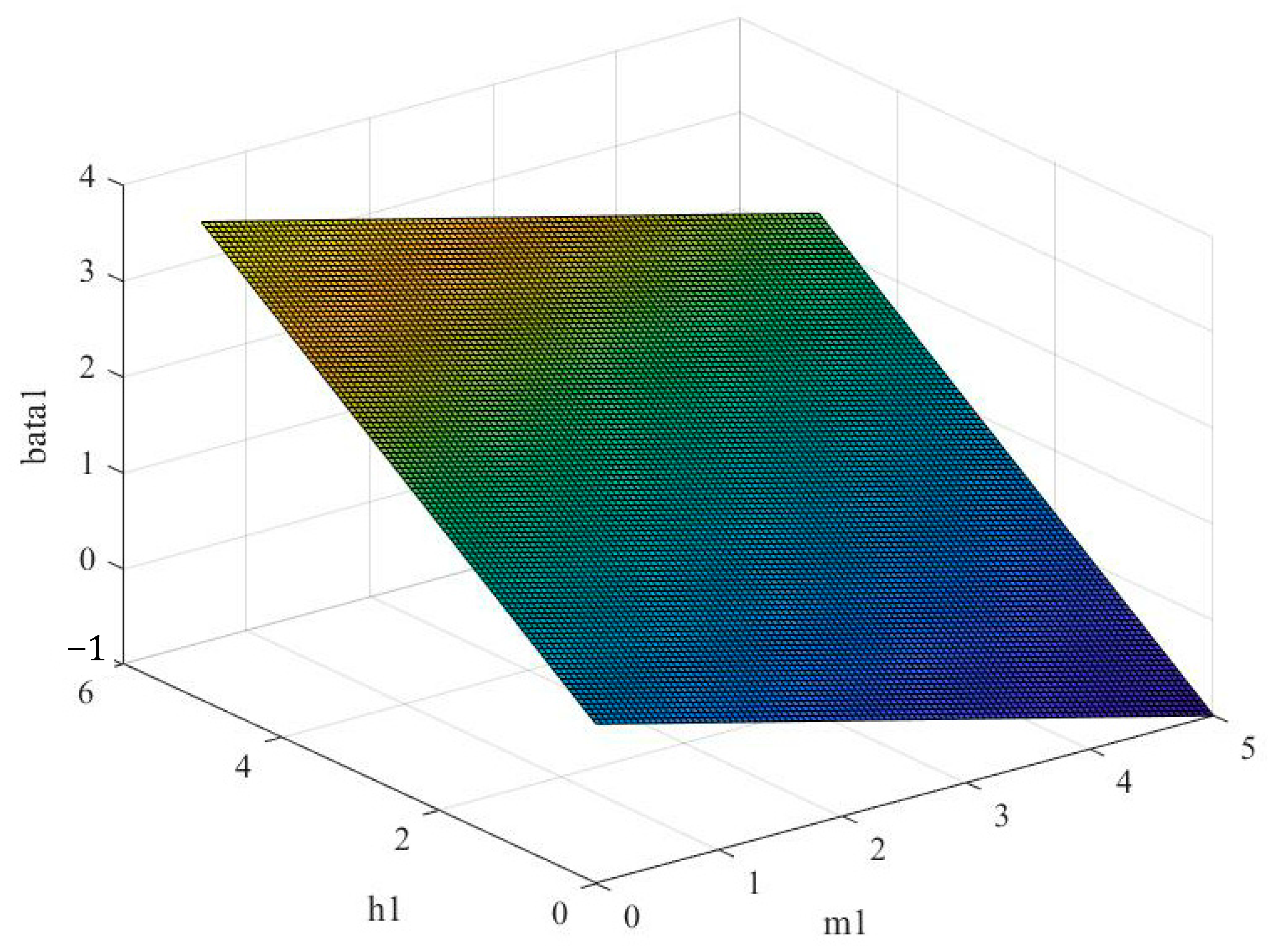

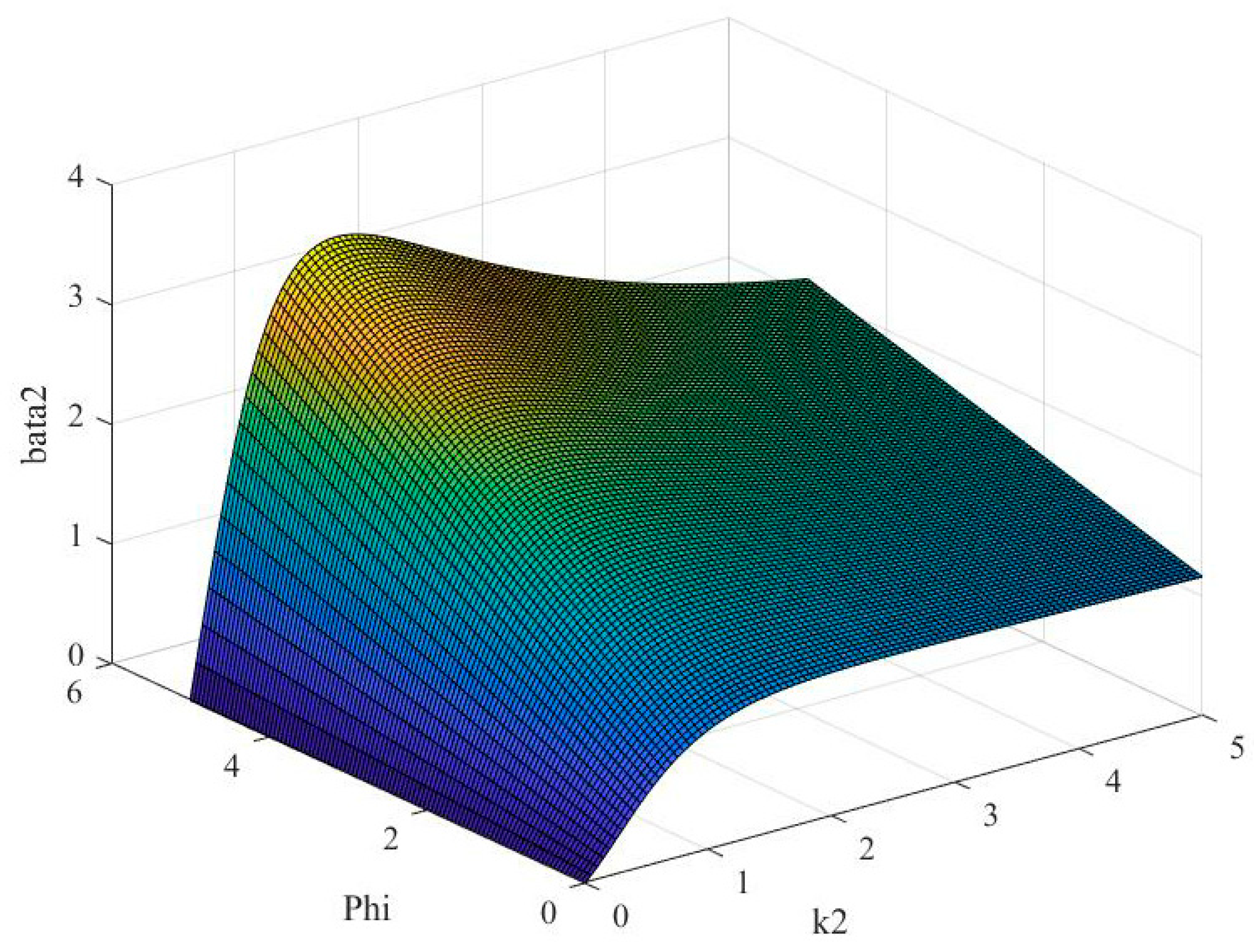

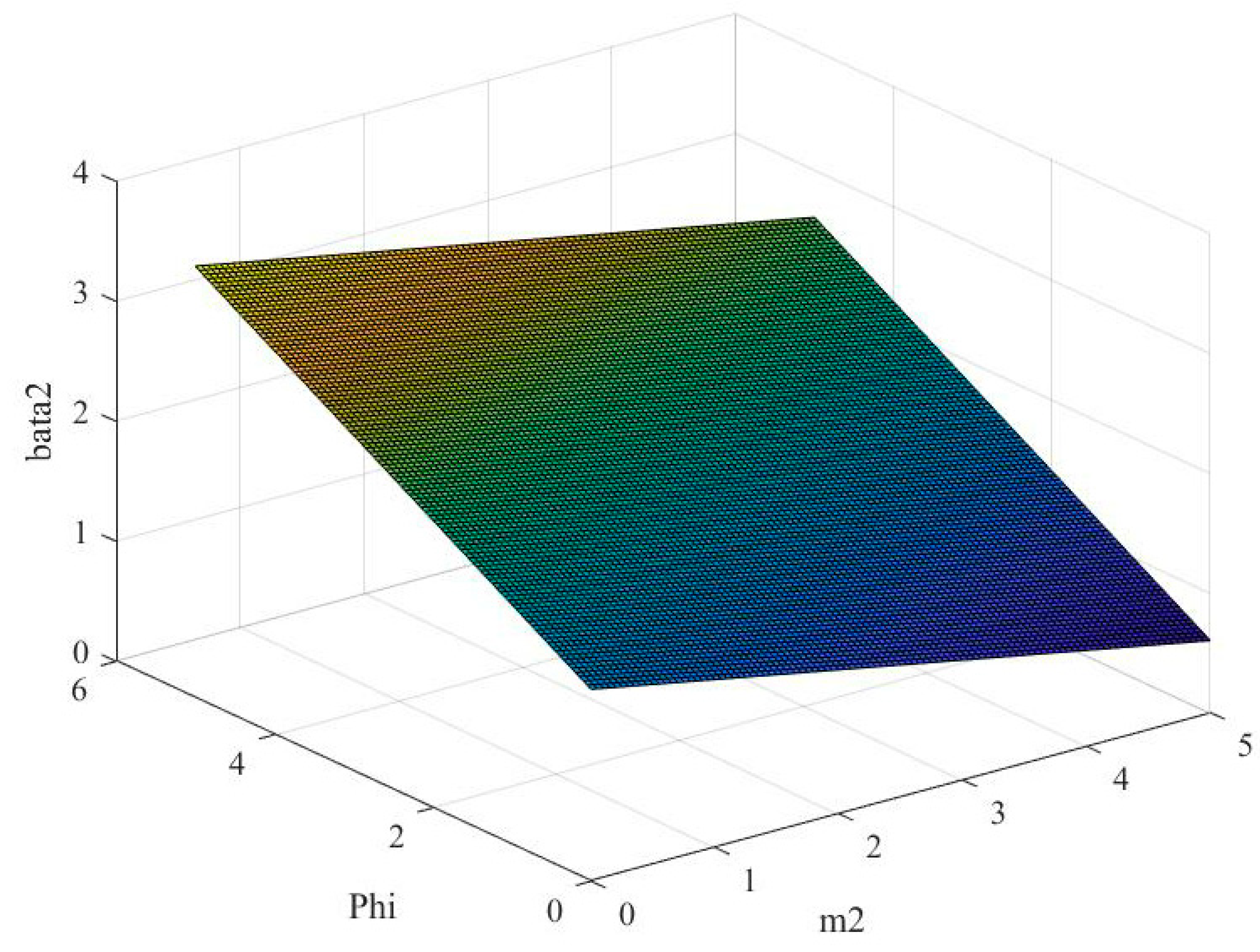

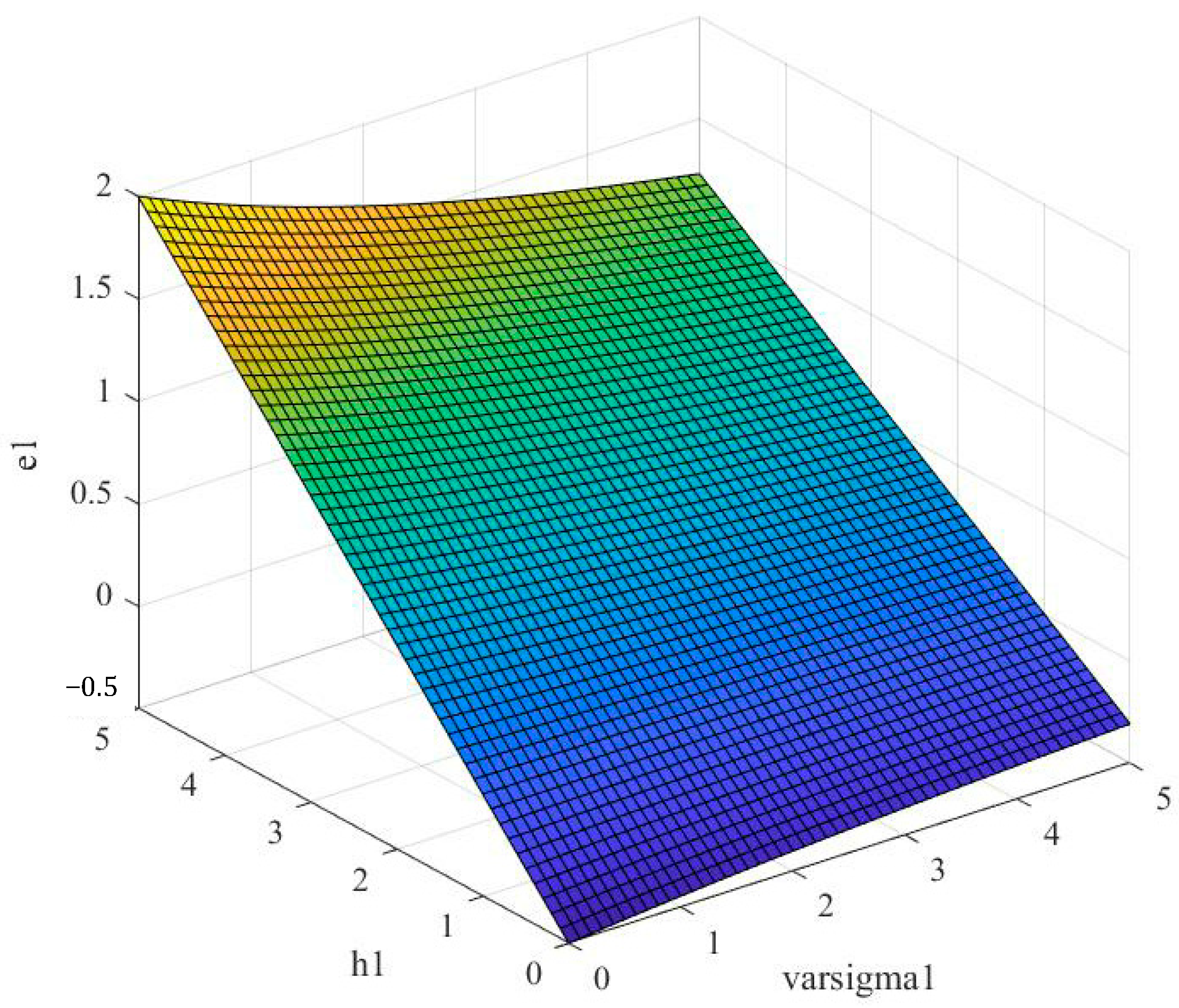

5.2. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Incentive Strength of Merchants by Platform Companies

Figure 6 illustrates how the platform enterprise’s incentive intensity

exhibits a downward distortion in response to changes in the merchant’s reliance on platform enterprise

and organizational capability coefficient

. However, this distortion will lessen as the coefficient decreases. With a rise in the merchant’s organizational capability coefficient

and an increase in the merchant’s reliance on the platform enterprise

, the platform enterprise’s incentive intensity tends to increase and decrease. This implies that, in general, the platform enterprise’s incentive intensity increases in tandem with the merchant’s increased dependency on the platform enterprise. This is because the platform is more important to the merchant for sales and promotions, and, as a result, the platform can guarantee the merchant’s engagement and loyalty by offering bigger incentives. Nevertheless, there may be a downward distortion to this increase in incentive intensity, which is not linear. The increase in incentive intensity provided by the platform enterprise may progressively decline following a certain point of increased merchant reliance. The degree of this distortion may decrease in tandem with the reduction in specific elements, such as regulatory expenses, market competition, and so on. Platform companies might be more equipped or more ready to offer ongoing incentives when these outside influences lessen. Secondly, the operational and managerial effectiveness of a merchant is reflected in its organizational capacity factor. A rise in an e-commerce merchant’s organizational capability coefficient indicates improved sales and operational activity management. Initially, when the merchant’s organizational capability factor rises, the platform enterprise’s incentive intensity may also rise. This is so that high-performing merchants can receive more rewards from the platform since they can increase their sales and market share. Nonetheless, the platform enterprise’s incentive intensity may tend to decline as the merchant’s organizational competence coefficient rises to a particular point. This can be because the platform does not need to offer as many outside incentives because the merchant is now more self-driven.

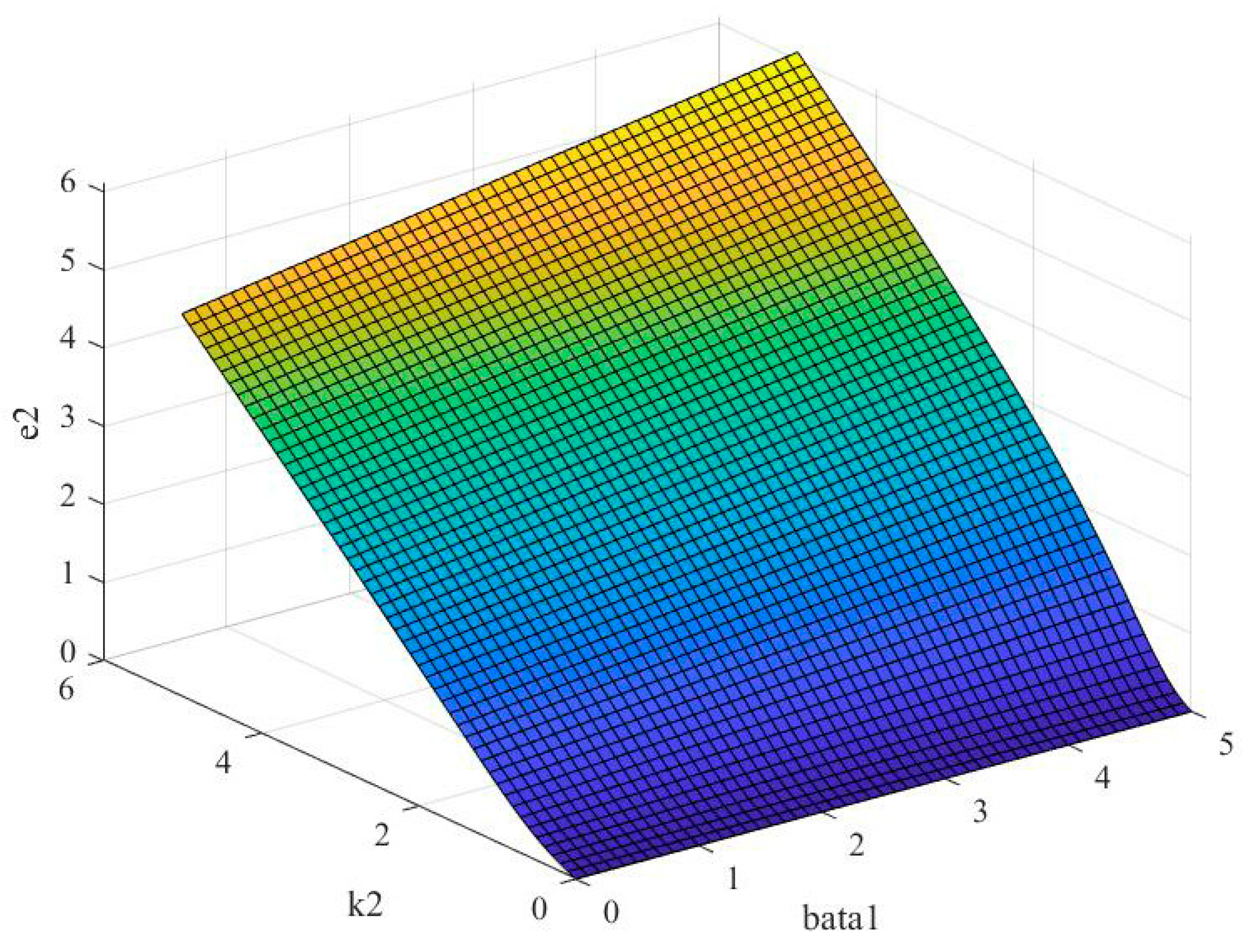

As seen by

Figure 7, the platform enterprise’s incentive intensity

rises in proportion to the merchant’s reliance

on it, but it falls in proportion to the maximum punishment

imposed by the platform enterprise upon discovering the merchant’s speculative activity. This implies that, in general, platform companies that regulate merchants’ speculative activities must continue to be appealing to merchants while also successfully controlling such behaviors. As a result, platform businesses can vary the incentive intensity based on the level of speculative activity and the reliance of merchants. In order to preserve the fairness and order of the platform, the platform enterprise will increase incentives when merchants are heavily dependent on it and speculative behavior is low. When speculative behavior increases, however, the platform enterprise will lessen the incentive intensity by imposing harsher penalties. The incentive intensity of platform businesses exhibits a diminishing trend with an increase in the maximum penalty that these firms impose for the speculative behaviors of merchants. This indicates a trade-off between platform enterprises’ incentives and regulation. Platform companies will not need to offer as many incentives if they impose harsh penalties for speculative activity because merchants will be less inclined to do so out of a concern for taking on unnecessary risk.

Figure 8 illustrates how platform enterprises’ incentive intensity

is trending upward in tandem with the government’s incentive intensity

and their capacity coefficient

. Consequently, the platform enterprise will offer merchants incentives that are more intense. Second, when the platform enterprise’s capability coefficient rises, its management quality and operational efficiency climb as well. This allows it to better control merchant behavior and discourage speculative activity. Platform businesses with high-capacity coefficients are also better able to offer a variety of incentives in order to satisfy the demands of various merchants and strengthen their position in the market.

5.3. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Effort Level of Platform Companies

Figure 9 illustrates this: as the platform enterprises’ effort–cost coefficient

rises, so does their level of effort

; conversely, as the government regulation effort

rises, the amount of effort A rises. This is a reliable measure of the platform companies’ level of effort. This implies that the expense of expanding the platform enterprises’ regulatory effort is reflected in the effort–cost coefficient. The cost of each extra unit of regulatory effort made by platform enterprises rises in proportion to an increase in this coefficient. As a result, platform companies may decide to scale back their regulatory efforts due to financial constraints. Platform businesses will come under more external pressure and scrutiny as government regulation grows. The fee that platform enterprises must pay rises in proportion to each unit of increased regulatory effort when the cost of effort coefficient rises. When government regulatory efforts expand, platform enterprises are subject to increased external pressure and scrutiny. Platform companies will typically step up their regulatory efforts to make sure that their platform activities are in compliance with the standards in order to abide by the government’s regulatory obligations, prevent potential penalties, and mitigate any bad effects. In summary, platform companies balance the advantages and disadvantages of controlling merchant conduct. Platform companies may lower their level of effort when their effort–cost coefficient is high, that is, when the cost of increasing regulatory effort is high. However, platform companies would typically step up their regulatory efforts in response to increased government regulation in order to minimize potential consequences and fines. This underscores that external government regulatory initiatives have a significant impact on platform enterprises’ regulatory conduct in addition to internal cost–benefit analyses. The regulatory actions of platform corporations are greatly influenced by the government’s responsibility in upholding consumer rights and interests as well as in maintaining market order.

According to

Figure 10, platform enterprises’ effort levels

increase in tandem with their competence coefficients

and government monitoring

. However, it should be noted that they are comparatively more susceptible to government oversight. This indicates that platform enterprises, firstly, recognize that, when their capability coefficient increases, they must exert a greater effort to guarantee the platform’s steady operation, optimize the user experience, and boost the market’s competitiveness. This approach includes the stringent regulation of platform rules, service quality, and user safety in addition to technology innovation and human investment.

On the other hand, there is a greater effect of government regulation intensity on the level of effort that platform enterprises put forth. This implies that platform companies respond to regulatory pressure from the government by changing their tactics and ways of operating more quickly. Platform companies are well aware of the severe legal repercussions and market hazards they would encounter if they breach regulatory rules, which contributes to this sensitivity. The government has considerable regulatory power and influence over the platform economy. Furthermore, platform enterprises’ proactive and adaptable approach to handling regulatory difficulties is shown in their sensitivity. Platform organizations will demonstrate proactive and adaptable approaches to regulatory challenges, continually enhancing their efforts and strengthening platform self-correction to ensure compliance with legal requirements and regulations.

According to

Figure 11, although platform enterprises are somewhat sensitive to the social benefit conversion coefficient, their effort level

increases with increases in both their own risk sensitivity coefficient

and social benefit conversion coefficient

. This implies that platform enterprises’ risk sensitivity coefficient, in the first place, indicates the weight they give to possible hazards. Platform enterprises are more likely to step up their regulatory efforts in an attempt to reduce the risks associated with inadequate regulation, like lawsuits and reputational damages, when the risk sensitivity coefficient rises. Additionally, platform enterprises’ regulatory efforts can be translated into real societal benefits, as measured by the social benefit transformation coefficient. Increasing the caliber of products, defending the rights and interests of customers, and encouraging honest competition in the marketplace are all part of this. When the social benefit conversion coefficient grows, it suggests that platform enterprises’ regulatory efforts can be more successfully converted into social well-being, which encourages platform enterprises to implement even more regulations. Lastly, a platform enterprise may be more concerned with the social consequences of its regulatory actions if it has a higher sensitivity to the social benefit transformation coefficient. The platform company’s emphasis on social responsibility or its strategic goals for long-term market development may be the cause of this sensitivity. The platform enterprise adapts its level of regulatory effort more quickly in response to changes in the social benefit conversion factor.

5.4. Analysis of Factors Influencing Merchant Effort Levels

Figure 12 demonstrates that, when the intensity of government incentives for platform enterprises

and merchants’ organizational capability coefficient

increase, there is a downward distortion in merchants’ effort level

. However, this distortion continues to decrease as merchants’ organizational capability coefficient

increases. This implies that, first, merchants may experience increased performance pressure or expectations in response to intensifying government incentives for platform corporations, which may prompt them to temporarily pursue more effective sales or operational techniques. But, in their quest for instant gratification, retailers risk ignoring long-term sustainable initiatives like customer service optimization and product quality enhancement due to the strong incentives. Because of this, a merchant’s level of effort could show a “downward distortion”, which would make it seem efficient in the short term but potentially hurt the company in the long run. Second, the potential of a merchant to react to government incentives rises with its organizational capacity coefficient. This implies that merchants can pursue performance while maintaining stability and sustainability in their level of effort. When the organizational competence coefficient rises, the downward distortion in merchants’ effort levels thus decreases.

Overall, this situation might suggest that, when regulating platform businesses, the government should take into account the various organizational capacities of merchants when creating incentive programs to prevent policies that are too general and cause distortions in the effort levels of merchants. In order to adapt more effectively to market shifts and government incentives while achieving long-term sustainable development, retailers need to concurrently aggressively strengthen their own organizational capacities.

Figure 13 illustrates this relationship: the merchant’s effort level A rises with the merchant’s reliance on platform company B, but it falls with the merchant’s effort–cost coefficient C. This implies that a merchant’s effort level rises in tandem with its dependence on the platform enterprise. Wohllebe [

41] (2022) and Engert, et al. [

42] (2022) also note that retailers depend more and more on e-commerce platforms since they offer them convenient shopping options and excellent business chances. Merchants typically step up their efforts to maintain a positive relationship with the platform and take advantage of these commercial prospects, such as by optimizing customer service and improving product quality. Second, a merchant’s effort level falls even as its effort–cost coefficient rises. A merchant may believe that the costs are too high and reduce effort when their operating cost coefficient, also known as the effort–cost coefficient, above a certain threshold (e.g., 10%). Conversely, quality merchants are generally able to maintain a good effort level, achieve cost control, and achieve operational benignity when the operating cost coefficient is kept within the range of 4–7% [

43] (Han et al., 2022).

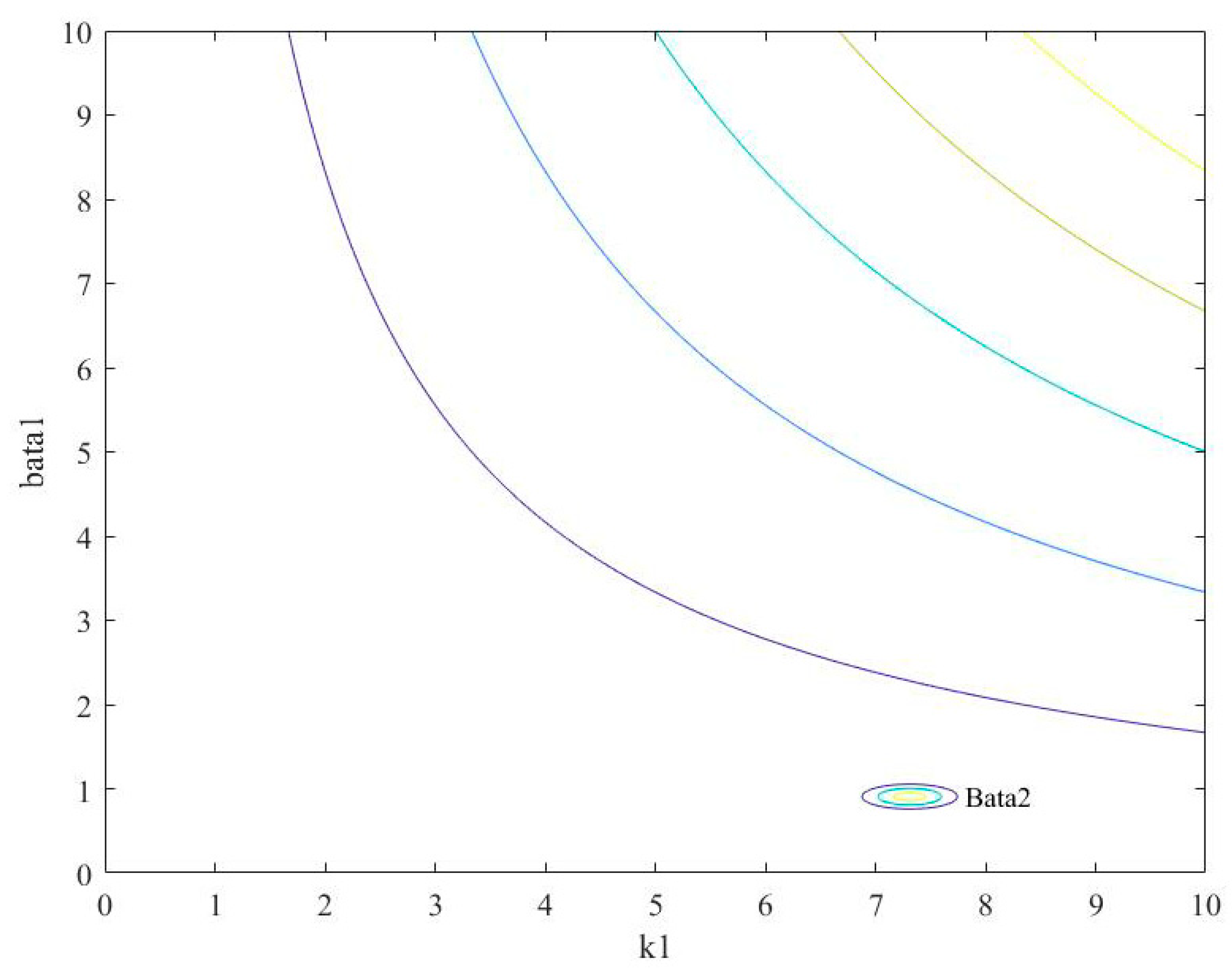

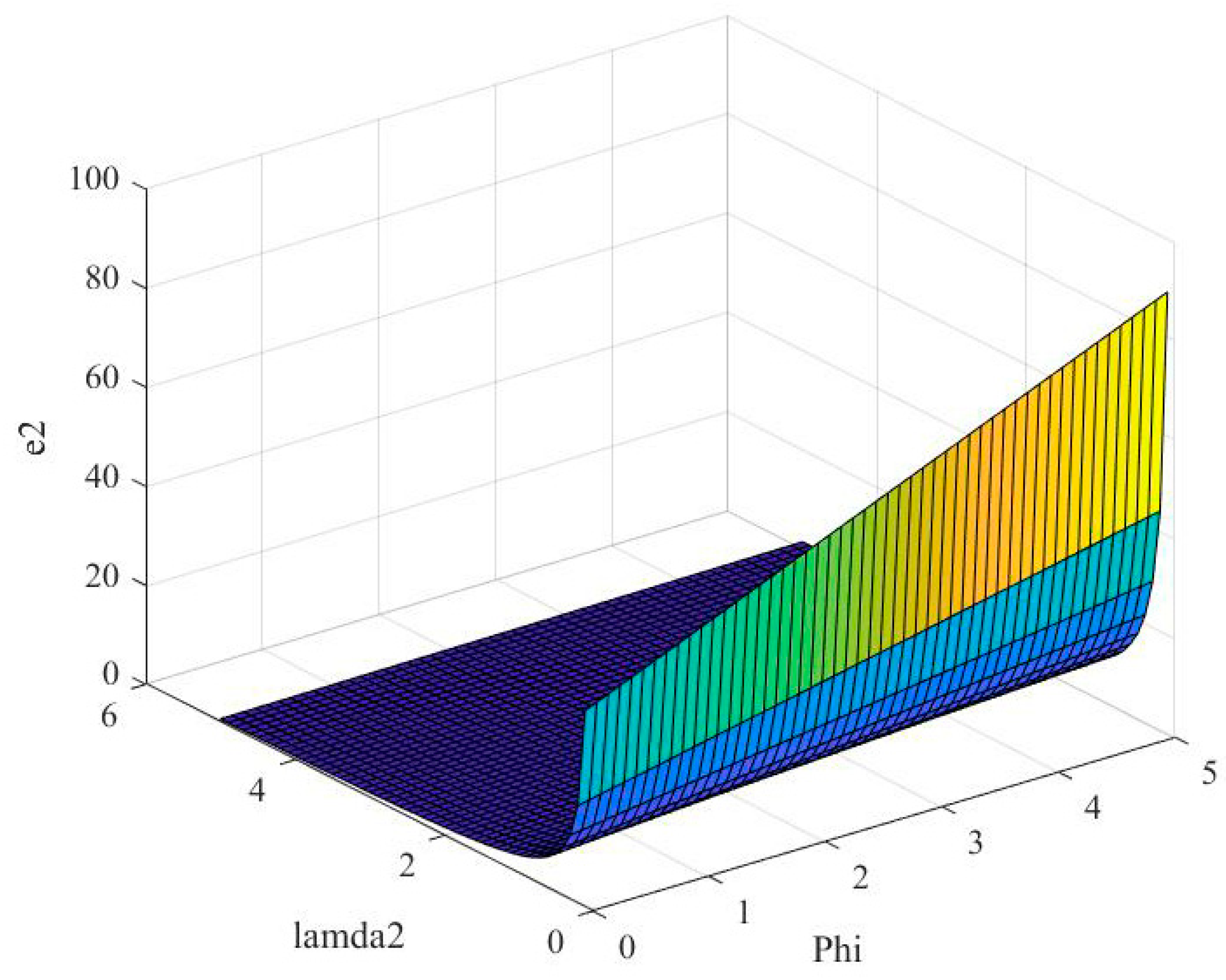

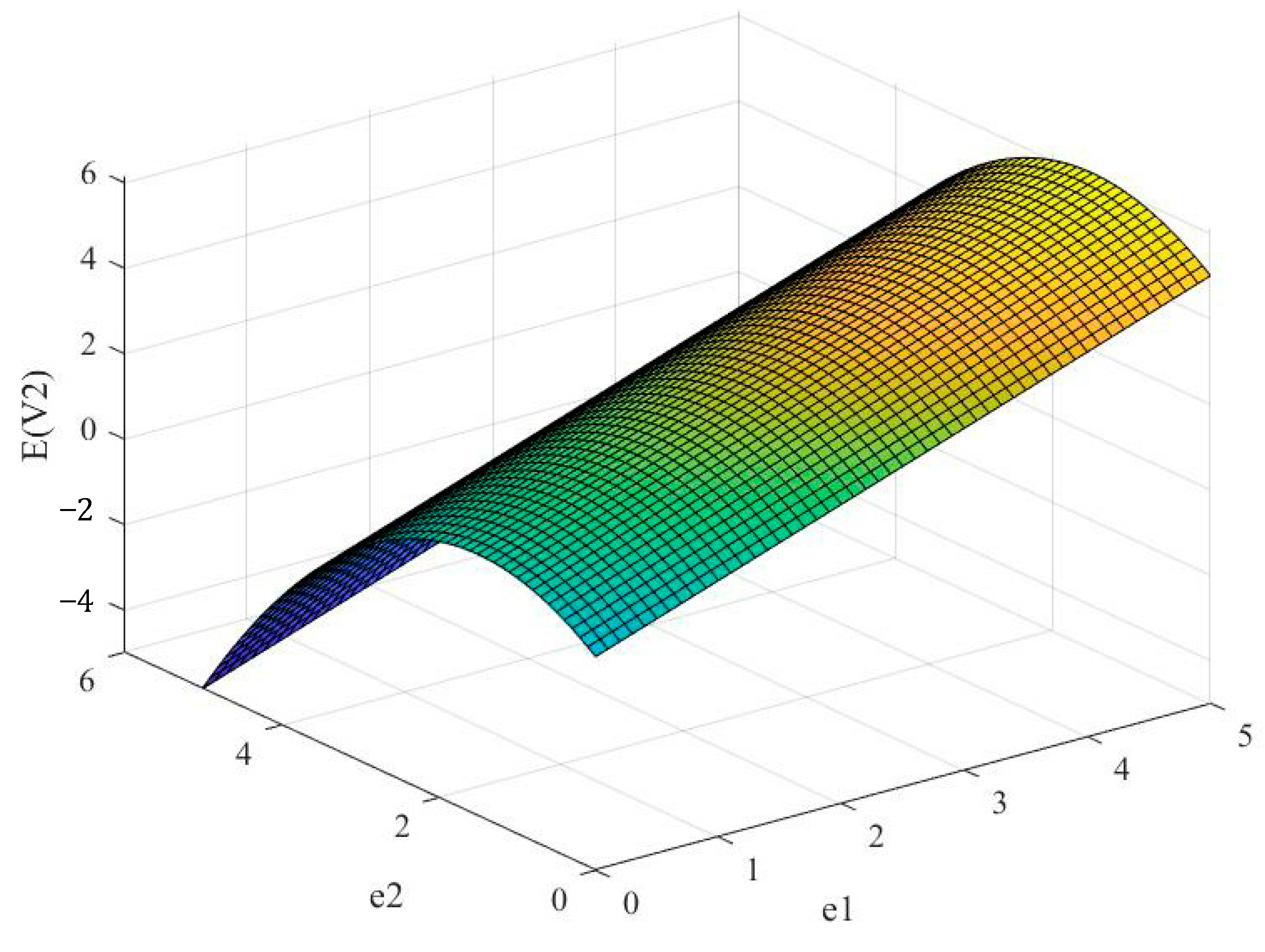

5.5. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Expected Utility of Platform Companies

The expected utility

of the platform enterprise rises as the capability coefficient

and the social benefit transformation coefficient

rise, as shown in

Figure 14. The expected utility effect of the two for the platform enterprise is comparatively constant. This shows that: firstly, the social benefit conversion coefficient represents the degree to which the socio-economic and cultural-development-promoting function that e-commerce platforms play is converted into the platform’s actual value. As the capability coefficient increases, platforms can expedite order processing, streamline distribution, and logistics, enhance customer support quality, and reduce operational costs, all of which contribute to increased profitability. Platform businesses may process orders more quickly, streamline distribution and logistics, raise the caliber of customer support, and more, as the capability coefficient grows, which lowers operating costs and boosts profitability. Second, the predicted utility of the platform is enhanced by the mutual reinforcement of the platform enterprise capacity and the coefficient of transformation of social benefits. Enhancing social benefits adds to the platform’s legitimacy, appeal, and profitability on the one hand; increasing the platform enterprise’s capability, on the other hand, helps to maximize operational effectiveness and service quality, which, in turn, enhances social benefits even more. They both collaborate on the anticipated utility of platform businesses, creating a positive feedback loop. The predicted usefulness of platform enterprises will rise in tandem with improvements in the capability and social benefit transformation coefficients, hence advancing the platform’s realization of sustainable development.

Ultimately, the expected utility of platform enterprises rises in tandem with the platform enterprises’ capability and social benefit transformation coefficients, and their respective effects on the expected utility of platform enterprises are largely consistent. This implies that, in order to achieve the platform’s long-term development, focus should be given to enhancing the platform’s capacity and social benefit during the platform enterprise monitoring process.

Figure 15 illustrates how the effort level

of the e-commerce platform and the effort level

of the merchants cause a negative distortion in the expected utility

of the platform enterprises. This demonstrates that, when the merchant effort increases, the projected utility of the platform improves and then drops, and the distortion becomes more noticeable as the e-commerce platform effort increases.

First, as merchants put in more effort, platform enterprises’ predicted utility first rises. This is due to the fact that the merchant’s efforts may be seen in the form of improved products and services, more forceful marketing initiatives, etc., all of which enhance platform functionality and user happiness, ultimately raising platform income. However, the predicted utility of the platform company may start to decrease when the merchant’s effort level surpasses a particular level. This might be the result of an increase in the merchant’s effort–cost, which compresses profit margins. It might also trigger unfavorable events like price wars and hostile competition, all of which could be harmful to the platform’s overall goals. Second, the e-commerce platform’s own degree of effort has a greater influence on the distortionary dynamics of predicted utility than does the merchants’ level of effort. This is because e-commerce platforms have more power and authority over marketing, technical innovation, and regulations. This is conceivable for two reasons: First, e-commerce platforms might overinvest in specific areas, including marketing and expansion, which would squander money and reduce productivity. Second, the platform’s reputation and interests could be harmed if there are oversight flaws or misconduct that leads to unfair competition among merchants, the spread of counterfeit goods, and other issues. Third, while technological innovations can enhance the operational efficiency and service quality of platforms, they may also bring about technical risks, security risks, and other issues that require platforms to invest more resources to deal with.

The aforementioned downward distortion implies that platform companies’ regulatory conduct should be balanced in order to allow merchants’ and platform enterprises’ efforts to further the platform’s overall development without compromising the intended utility. To uphold fair competition and market order, platform enterprises should enhance their regulatory efforts. At the same time, they should sanely direct merchants’ efforts to steer clear of aggressive and excessive competition. Furthermore, platform enterprises must make modest investments in their own level of effort in order to prevent resource waste and falling efficiency. They must balance the advantages and disadvantages of technological innovation and market marketing to make sure that investment returns are optimized.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Beginning with the background of collaborative platform economy regulation, this paper constructs a dual principal–agent model and solves and simulates the dual principal–agent model in order to analyze the regulatory incentive problem of government–platform enterprise–merchant, a tripartite subject of regulatory incentives of the platform economy under the condition of asymmetric information. This allows the investigation of the primary factors influencing the optimal incentive intensity, the optimal regulatory intensity, and the optimal level of effort. The following are the precise findings and managerial insights:

(1) Platform companies will ultimately impact merchants’ self-regulatory conduct through the government’s optimal incentives and regulation in the process of platform economic governance. Collaboration between the government, platform companies, and merchants is essential to achieve this broad, deep, and lasting impact.

Firstly, governments can offer a variety of incentives, such as tax breaks, financial aid, or other policy support, to motivate platform companies to better fulfill their regulatory obligations. Platform businesses may be more inclined to impose stringent management and oversight in order to preserve the stability and well-being of the platform ecosystem as a result of these incentives. To control and limit the operational behavior of platform enterprises, the government must establish a number of laws, rules, and regulatory policies. To make sure that platform enterprises may function legally, these regulatory regulations may include provisions for consumer rights protection, data protection, and anti-unfair competition.

Secondly, platform companies act as intermediaries between the public sector and retailers. Platform companies will develop the necessary internal policies and procedures to oversee and manage merchants in compliance with legal and regulatory standards as well as government incentives. Platform companies will monitor and assess merchants’ business practices in real time to ensure they adhere to platform guidelines as well as applicable laws and regulations. They will do this by using technological tools and data analysis.

Ultimately, platform businesses will enhance their oversight and management of merchants and raise the penalty for non-compliance with the best possible government incentives and regulations. Merchants must gradually increase their awareness of self-discipline and adhere to platform rules, laws, and regulations in order to grow steadily on the platform over time. Over time, this self-control conduct on the platform will become the standard and a habit, increasing the platform’s legitimacy and competitiveness.

(2) Platform companies and the government can support merchants in the platform economic governance process by implementing monitoring mechanisms; on the other hand, incentives and regulations have a certain relationship and must be closely monitored to achieve the optimal governance outcome. The government and platform companies must thoroughly analyze the relationship between incentives and regulation, as well as the associated changes in costs and benefits, as part of the platform economic governance process. The optimal governance effect can be achieved and the long-term, robust growth of the platform economy can be encouraged by thoughtfully combining and adjusting incentives and restrictions.

Governments and platform enterprises must consider the expenses related to implementing incentives and regulations. While the costs of regulatory measures include items like technical inputs and enforcement costs, the costs of incentives include things like tax incentives and financial outlays for funding support. To ensure the efficacy and sustainability of incentive and regulatory measures, the link between costs and benefits must be considered during implementation. There are definite advantages to enacting regulations and incentives. Regulations can preserve market order and fair competition while fostering the robust growth of the platform economy. Incentive measures can lower the cost and risk of noncompliance by merchants and improve their willingness and motivation to comply. It is crucial that we evaluate whether the benefits outweigh the costs to guarantee the economic and social benefits of the incentive and regulatory measures.

(3) The external regulation of businesses and merchants falls under the category of external incentives in the economic governance of platforms. These entities also require internal incentives to raise the overall level of governance by raising the bar for their own work, raising the coefficient of transformation of social benefits, and so forth. Building a pleasant and healthy atmosphere is essential to achieving this goal because it helps merchants and platform enterprises understand the value of sustainable development and self-improvement.

In the first place, platform companies should motivate merchants to add more value by setting up a fair incentive system. To help them differentiate themselves from the competition, this involves—but is not limited to—offering technical support, marketing support, training materials, and other help. Platform companies should also promote the transformation of social benefits at the same time, pushing merchants to prioritize sustainable development and social responsibility over economic gains, and boosting the social benefit transformation factor through doable initiatives.

Second, increasing this kind of intrinsic incentive can strengthen the cohesiveness and centripetal force of the entire platform in addition to encouraging platform businesses and merchants to practice self-control and self-improvement. Platform businesses and merchants will become more involved in the economic governance of the platform when they recognize how well their development styles complement one another. This will create a positive feedback loop and engagement.

(4) All stakeholders must cooperate to maximize the overall benefits in the platform economy governance process in order to maintain long-term cooperation between the government, platform companies, and merchants.

The government must first create and amend pertinent laws and regulations to provide a transparent and unambiguous regulatory framework for the platform economy. It should also promote the innovation and growth of the platform enterprises, safeguard the rights and interests of consumers, and uphold a fair and competitive market environment by offering policy support and guidance. This lays the groundwork for long-term collaboration by fostering a relationship of mutual trust between the government, platform companies, and merchants.

Second, in order to make sure that their business operations are lawful and compliant, platform companies should proactively adhere to the rules and laws established by the government and improve internal management. Simultaneously, platform companies ought to consistently enhance their technological proficiency and service caliber in order to furnish merchants with an enhanced and more convenient trading environment and facilitate their augmentation of operational effectiveness. Platform companies should also actively engage with the government, provide input on market demands and conditions, and work together to support the robust growth of the platform economy.

Lastly, in order to guarantee that the caliber of the products and services they sell fulfill the requirements, retailers must adhere completely to the platform’s guidelines. Merchants should also actively engage in platform activities, build strong working relationships with the platform, and work together to increase market competitiveness and brand influence. Merchants should also be aware of what customers want, deliver high-quality goods and services, gain the confidence and goodwill of customers, and support the growth of the platform economy.

The dual principal–agent model, in summary, offers a helpful analytical framework for the platform economy’s regulatory incentive problem. By creating a fair incentive structure, the government, platform companies, and merchants can work together to effectively coordinate the relationship and support the platform economy’s healthy development. In order to create an ideal contractual system, this study creatively builds a dual principal–agent model for the government, platform enterprise, and merchant in platform economy governance. This model integrates incentives and monitoring measures. The unique role that the platform enterprise plays in the dual principal–agent relationship—that is, as both the government’s agent and the merchants’ principal—is then thoroughly examined. Quantitative techniques are used to analyze the contract structure under optimal regulatory and incentive mechanisms. The interaction and substitution effects between regulatory and incentive mechanisms are also covered. However, the relationship between the parties in platform economic governance is more complex and involves multiple tasks; additionally, the benefits will vary over time, and future research will focus on this topic instead of the static study of regulatory incentives in platform economic governance.