Competitive Integration of Social Tourism Enterprises Through an Organizational Management System: The Case of El Jorullo in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Set of formally organized private enterprises, with decision-making autonomy and freedom of membership, created to fulfill the needs of their members through the market, the generation of goods and services, insurance or financing, in which both the distribution of profits or surpluses among the members and decision-making do not depend directly on the capital or individual contributions of each member, with each member having one vote, or are carried out in any case through democratic and participatory decision-making processes[6] (p. 23).

“…a type of collective entrepreneurial organization aimed at utilizing resources within a specific territory, whether ejidal or communal, where the management and operation of these business ventures enhance and empower the tenants. These initiatives arise as a response to the challenges of poverty within the agricultural sector”.

- (a)

- They offer solid agricultural production, and in their territories are located most of the forest areas, mountains, mangroves, coasts, mines, water, and various natural resources;

- (b)

- Those who are mainly engaged in non-agricultural activities have great potential due to their natural resources, traditional know-how, and knowledge that, if supported, could be avenues for local development;

- (c)

- Ejidos and communities have great potential to produce and conserve biodiversity;

- (d)

- A figure that emerges to convert farm workers into free wage earners, not tied to living off their salary;

- (e)

- Their lands are inalienable and cannot be seized under conventional procedures.

- (a)

- They have significant economic and ecological potential. However, given their considerable shortcomings, agricultural and forestry production is complex;

- (b)

- They are not homogeneous since there are significant differences in the allocation of resources;

- (c)

- The absence or weak cooperation resulting from a family organization prevents the implementation of strategies for the conservation, maintenance, and restoration of endemic resources, where families focus only on harvesting; and

- (d)

- The productivity of agricultural labor in Mexico is very low.

2. Theoretical Background

- -

- Variation: where new and varied forms appear in an organizational population.

- -

- Selection: contemplates a new organizational form and its aptitude to survive in its environment.

- -

- Retention: is the preservation and institutionalization of selected organizations to remain in the environment.

...these tangible elements play a fundamental role in a village’s daily life. They include goodwill, camaraderie, mutual support, and social connections among individuals and families that constitute a social unit—the rural community—where the school serves as its logical focal point

3. Materials and Methods

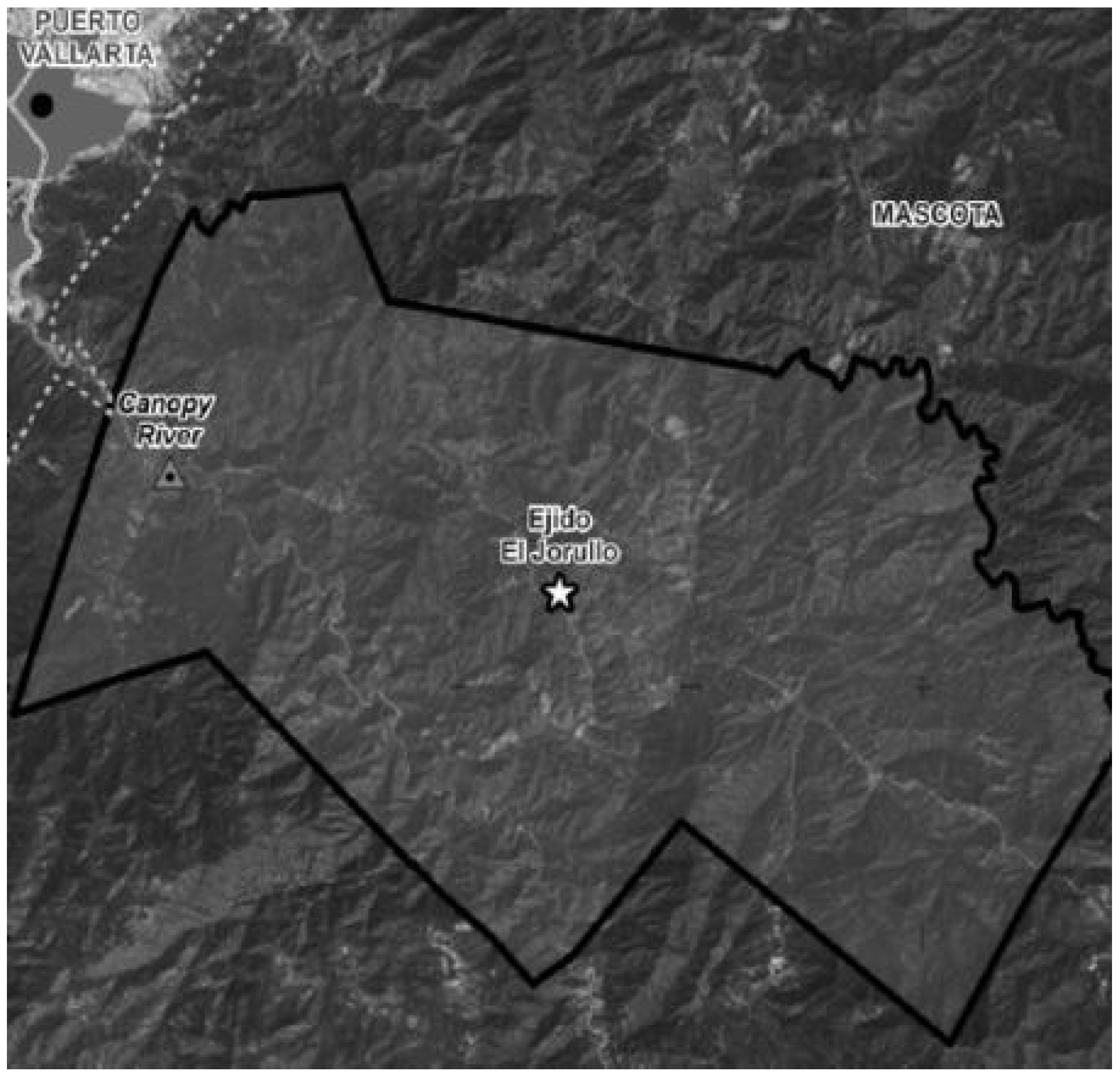

3.1. Context and Cases of the Study

- -

- An Environmental Management Unit (UMA) that currently has deer and wild boar.

- -

- A restaurant that uses local products to make traditional Mexican food. Its menu highlights these ingredients.

- -

- Sale of organic products made in the region.

- -

- Lodging system in cabins, nine in total.

- -

- Twelve hot springs pools.

- -

- Interpretive trails.

- -

- Farms.

- -

- Agricultural spaces.

- -

- Bird-watching walks.

3.2. Data Source and Processing

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Social Capital, Social Network Analysis, and a Socio-Ecological System of Entrepreneurship

4.2. Parts of the System

4.2.1. Develop Mission and Vision

4.2.2. External Evaluation

4.2.3. Formulation of Strategic Objectives and Strategies

4.2.4. Choice of Strategies

4.2.5. Plans and Budgets

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia Sáiz, A. ‘Globalisation, Cosmopolitanism and Ecological Citizenship’. Environ. Polit. 2005, 14, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R.; Berkhout, F.; Gallopin, G.C.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E.; Van Der Leeuw, S. The Globalization of Socio-Ecological Systems: An Agenda for Scientific Research. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Sánchez, R.; Peña-Casillas, C.S.; Cornejo-Ortega, J.L. Impact of the 4 Helix Model on the Sustainability of Tourism Social Entrepreneurships in Jalisco and Nayarit, Mexico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Casillas, C.S. Sistema de Gestión Organizacional Estratégica de Emprendimientos Como Medio de Influencia En La Competitividad. Caso El Jorullo En Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco; Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit: Tepic, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón Campos, J.L.; Chaves Ávila, R. La Economía Social En La Unión Europea; Comité Económico y Social Europeo: Bruxelles, Bélgica, 2012; ISBN 978-92-830-1966-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bargsted, A. Mariana El Emprendimiento Social Desde Una Mirada Psicosocial. Civilizar 2013, 13, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez Ramirez, J.M. La Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit y Sus Acciones En Torno a La Formación Para El Emprendimiento; Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit: Tepic, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Sánchez, R.; Cornejo Ortega, J.L.; Bravo Olivas, M.L.; Verduzco Villaseñor, M.D.C. Los Emprendimientos Sociales Turísticos. Nuevos Esquemas Para El Desarrollo Del Turismo En El Ámbito de Las Comunidades Rurales En Bahía de Banderas, México. Turpade Rev. Tur. Patrim. Desarro. 2018, 11, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social–Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, F.; Deng, M. Adaptation of Tourism Transformation in Rural Areas under the Background of Regime Shift: A Social–Ecological Systems Framework. Systems 2024, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, L. Multifunctional Rural Development in China: Pattern, Process and Mechanism. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Lopez, Á.; López Pardo, G.; Andrade Romo, E.; Chávez Dagostino, R.M.; Espinoza Sánchez, R. Introducción. In Lo glocal y El Turismo. Nuevos Paradigmas de Interpretación; Academia Mexicana de Investigación Turística A.C.: Chicoloapan, Mexico, 2012; pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-607-95909-0-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez Dagostino, R.M.; Sánchez González, Y.; Fortes, S. Introducción. In De Campesinos a Empresarios: Experiencia Turística del Ejido El Jorullo; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2017; pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-607-8525-22-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morett-Sánchez, J.C.; Cosío-Ruiz, C. Panorama de Los Ejidos y Comunidades Agrarias En México. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2017, 14, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández y Fernández, R. Problemas Creados Por La Reforma Agraria En México. El Trimest. Económico 1946, 13, 463–494. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce Lázaro, P.; Pérez Ramírez, S.V. Historia de Vida de Dos Líderes Emprendedores. In De Campesinos a Empresarios: Experiencia Turística del ejido El Jorullo; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2017; pp. 121–144. ISBN 978-607-8525-22-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez González, Y. El Proyecto Turístico Comunitario: La Experiencia de Canopy River. In De Campesinos a Empresarios: Experiencia Turística del Ejido El Jorullo; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2017; pp. 145–176. ISBN 978-607-8525-22-5. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R. Teoría y Diseño Organizacional; Cengage Learning Editores S.A. de C.V.: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2011; ISBN 978-607-481-764-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. The Population Ecology of Organizations. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 929–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L. Teoría y Diseño Organizacional, 15th ed.; Cengage Learning Editores: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2019; ISBN 978-607-526-814-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Organizational Ecology, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-674-64349-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hanifan, L.J. The Rural School Community Center. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 1916, 67, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifan, L.J. The Community Center; Wentworth Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Arechavala Vargas, R.; Hernández Águilar, E.D.L.P. Modelo de Procesos de Clusterización En Empresas de Jalisco. In Procesos de Clusterización en Jalisco. RETOS del Aprendizaje y La Colaboración Interempresarial; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2014; ISBN 978-607-450-953-3. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C. Ucinet 6 (Version 6.733—25 SEPT 2021) for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis 2002. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/ucinetsoftware/home?authuser=0 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Johnson, J.C. Analyzing Social Networks; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4462-4741-9. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Casillas, C.S.; Espinoza Sánchez, R.; Plascencia Cuevas, T.N. Aproximación Sobre Dinámica Relacional. Caso El Jorullo En Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. TURyDES Rev. Tur. Desarro. Local 2021, 14, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Verduzco Villaseñor, M.d.C. Propuesta de Planeación Estratégica Como Herramienta ParaLa Administración deNegocios y La Calidad deVida Laboral Del Emprendimiento Social Rancho El Coyote. Master’s Thesis, Universidad deGuadalajara, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Grisales, J.A.; Ceballos, Y.F.; Bastidas-Orrego, L.M.; Jaramillo Gómez, N.I.; Chaparro Cañola, E. Development of an Agent-Based Model to Evaluate Rural Public Policies in Medellín, Colombia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Barquero, R. Administración Estratégica 2016. Costa Rica Rodríguez Barquero R. Administración estratégica versión 4.2, 2016. Available online: https://www.tec.ac.cr/sites/default/files/media/curriculum/curriculum_v_rony_rodriguez_barquero_2021.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Andersson, E.; Haase, D.; Anderson, P.; Cortinovis, C.; Goodness, J.; Kendal, D.; Lausch, A.; McPhearson, T.; Sikorska, D.; Wellmann, T. What Are the Traits of a Social-Ecological System: Towards a Framework in Support of Urban Sustainability. Npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burholt, V.; Dobbs, C. Research on Rural Ageing: Where Have We Got to and Where Are We Going in Europe? J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šumrada, T.; Erjavec, E.; Šilc, U.; Žgajnar, J. Socio-Economic Viability of the High Nature Value Farmland under the CAP 2023–2027: The Case of a Sub-Mediterranean Region in Slovenia. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the World’s Countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-7619-4761-5. [Google Scholar]

- Baños Francia, J.A. Consideraciones Sobre La Gestión Metropolitana En México. Acercamiento al Caso de La Bahía de Banderas. Trace 2013, 64, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Casillas, C.S.; Espinoza Sánchez, R.; Bravo Silva, J.L. Emprendimientos Turísticos Rurales en Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. In Emprendimiento y Educación Superior en México: Diversos Enfoques en La Construcción de Ecosistemas; Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Facultad de Economía y Relaciones Internacionales: Tijuana, Mexico; Benemérita Universidad Autońoma de Puebla, Dirección General de Publicaciones: Facultad de Economía: Puebla, Mexico; Ediciones del Lirio, SA de CV: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2021; pp. 85–98. ISBN 978-607-607-732-0. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Navarro, K.L.; Sandoval Velázquez, I.V. El Territorio de El Jorullo. In De Campesinos a Empresarios: Experiencia Turística del Ejido El Jorullo; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2017; pp. 23–40. ISBN 978-607-8525-22-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes, S.; Sánchez González, Y. El Jorullo: Un Ejido Con Historia, Un Ejido Innovador. In De Campesinos a Empresarios: Experiencia Turística del Ejido El Jorullo; Universidad de Guadalajara: Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2017; pp. 97–120. ISBN 978-607-8525-22-5. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz García, M.d.C. Clubes de Productos Turísticos Como Estrategia de Negocios Para El Fortalecimiento de La Comercialización de Los Productos Turísticos Del Ejido El Jorullo. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Guadalajara, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- López Ramos, J.L.; González Gutiérrez, L.R.; Villanueva Sánchez, R. Turismo y Desarrollo Comunitario: El Caso Del Ejido El Jorullo En Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco; Universidad Nacional Costa Rica: Heredia, Costa Rica, 2017; pp. 491–500. ISBN 978-9968-687-02-7. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Sánchez, R.; Covarrubias, S.J.; Cornejo Ortega, J.L. Un Acercamiento al Estudio Del Paisaje Apoyado En La Ecología de La Población Empresarial Turística. In De la Dimensión Teórica al Abordaje Empírico del Turismo en México. Perspectivas Multidisciplinarias; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2014; pp. 95–102. ISBN 978-607-02-5863-3. [Google Scholar]

- Massam, B.H. Quality of Life: Public Planning and Private Living; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-08-044196-2. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Razo, C. Como Elaborar y Asesorar Una Investigación de Tesis; Pearson: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2011; ISBN 978-607-32-0456-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.B.; Mostafavi, A.; Kim, B.C.; Lee, A.A.; Boot, W.; Czaja, S.; Kalantari, S. Designing Virtual Environments for Social Engagement in Older Adults: A Qualitative Multi-Site Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 19 April 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Miguelez, M. Ciencia y Arte en la Metodologia Cualitativa; Trillas: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2007; ISBN 978-968-24-7568-9. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1967; ISBN 978-0-202-30260-7. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. El Diseño de La Investigación Cualitativa; Ediciones Morata S.L: Madrid, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-7112-806-5. [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada, I.; Miranda, F.; Pávez, T. Lineamientos de acción para el diseño de programas de superación de la pobreza desde el enfoque del capital social: Guía conceptual y metodológica; CEPAL, División de Desarrollo Social: Santiago, Chile, 2004; ISBN 978-92-1-322573-8. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, M.; Esteves, L.; Rodrigues, M. Clusters as a Mechanism of Sharing Knowledge and Innovation: Case Study from a Network Approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024, 25, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Geng, Y.; Dong, H.; Chen, W. Social Network Analysis on Industrial Symbiosis: A Case of Gujiao Eco-Industrial Park. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, P.; Golnam, A.; Wegmann, A. Coopetition-Based Business Models: The Case of Amazon.Com. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stages | Rodríguez (2016) | Rosas (2007) | Wheelen (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not applicable | 1. Diagnostic | Not applicable | |

| Nature of business | 1. Develop mission and vision | 2. Strategic factors | Not applicable |

| 1.1 Business Model | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| 1.2 Mission | 2.1 Mission | Not applicable | |

| 1.3 Vision | 2.2 Vision | Not applicable | |

| 1.4 Values | 2.3 Values | Not applicable | |

| 1.5 Competitive profile | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| External factors | 2. External evaluation | 3. Opportunities and Threats Analysis | 1. Environmental Analysis |

| 2.1 Great environment | Not applicable | 1.1 External: opportunities and threats | |

| 2.2 Nearby environment | Not applicable | 1.2 Natural, social, and industrial environment | |

| 2.3 Evaluation of external factors | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Internal factors | 3. Internal evaluation | 4. Strengths and Weaknesses Analysis | 1.3 Internal: strengths and weaknesses |

| 3.1 Value chain | Not applicable | 1.4 Structure, culture, and resources | |

| 3.2 Evaluation of internal factors | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Strategy generation | 4. Formulation of strategic objectives and strategies | 5. Quality Policy | 2. Strategy formulation |

| 4.1 Objectives, strategies, and indicators | Not applicable | 2.1 Mission | |

| 4.2 Strategic map | Not applicable | 2.2 Objectives | |

| 4.3 MECA Matrix | Not applicable | 2.3 Strategies | |

| 4.4 FODA Matrix | Not applicable | 2.4 Policies | |

| Study of strategies | 5. Choice of strategies | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| 5.1 Strategic position analysis | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| 5.2 Internal/external analysis | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| 5.3 Evaluation of strategies | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| 5.4 Strategy selection | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Start-up | 6. Plans and budgets | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| 6.1 Actions | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| 6.2 Tactical plans and budgets | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| 6.3 Implementation | Not applicable | 3. Implementation of strategies | |

| Not applicable | Not applicable | 3.1 Programs, budget, and procedures | |

| Not applicable | Not applicable | 4. Evaluation and control | |

| Not applicable | Not applicable | 4.1 Performance |

| Company or entrepreneurship | Name | Typology | Community | Status | Activity |

| Mundo Nogalito Canopy Tour | Private | Las Juntas y los Veranos | Active | Adventure tourism | |

| Canopy River | Social/public | El Jorullo | Active | Ecotourism and rural tourism | |

| Canopy Playa Grande | Social/public | Playa Grande | Active | Ecotourism and rural tourism | |

| Canopy El Edén | Private | Agua Caliente | Active | Ecotourism | |

| Rancho El Capomo | Private | Las Palmas | Active | Ecotourism and rural tourism | |

| Rancho El Charro | Private | Playa Grande | Active | Ecotourism | |

| Grupo Sustentable las dos aguas/Jorullo Paradise | Social/public | Los Llanitos, El Jorullo. | Active | Ecotourism | |

| Rancho El Coyote | Social/public | El Jorullo | Active | Rural tourism |

| Actors | Centrality | Intermediation | Network Proximity |

|---|---|---|---|

| EJIDO EL JORULLO | 0.276 | 46.276 | 43.939 |

| CANOPY RIVER | 0.345 | 12.701 | 48.333 |

| RANCHO COYOTE | 0.224 | 8.114 | 41.429 |

| JORULLO PARADISE | 0.224 | 5.985 | 42.029 |

| TRAVEL AGENCIES | 0.172 | 4.743 | 37.179 |

| STREET VENDORS | 0.073 | 2.477 | 35.802 |

| TOURIST GUIDES | 0.078 | 1.83 | 50.877 |

| REPS | 0.086 | 0.796 | 35.802 |

| MUNICIPAL TOURISM DEPARTMENT | 0.108 | 0.767 | 38.158 |

| RAMÓN GONZALEZ LOMELÍ (CONSULTANT 1) | 0.052 | 0.474 | 36.709 |

| VALLARTA VERDE | 0.022 | 0.391 | 34.524 |

| LOCAL DEPUTY | 0.009 | 0.24 | 29 |

| NATIONAL FORESTRY COMMISSION | 0.039 | 0.164 | 34.94 |

| JOSÉ MARIO MOLINA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY | 0.026 | 0.14 | 34.94 |

| UNIVERSITY OF GUADALAJARA (CUCOSTA) | 0.052 | 0 | 35.802 |

| PROJECTSMAN | 0.022 | 0 | 34.94 |

| HOTEL BUSINESSMEN | 0.103 | 0 | 36.25 |

| CRUISE SHIP MANAGEMENT | 0.129 | 0 | 36.709 |

| MEXICAN INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SECURITY | 0.069 | 0 | 34.524 |

| TAX ADMINISTRATION SERVICE | 0.069 | 0 | 34.524 |

| EMPLOYER’S CONFEDERATION OF THE MEXICAN REPUBLIC | 0.026 | 0 | 34.524 |

| SECRETARY OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT | 0.017 | 0 | 34.524 |

| CARLOS GUZMAN (CONSULTANT 2) | 0.017 | 0 | 34.524 |

| AIRLINES | 0.060 | 0 | 35.802 |

| STATE GOVERNMENT | 0.022 | 0 | 35.802 |

| NATIONAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE | 0.013 | 0 | 34.524 |

| SECRETARY OF COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSPORTATION | 0.004 | 0 | 33.333 |

| CYCLIST GROUP | 0.034 | 0 | 34.524 |

| NATIONAL FINANCIAL | 0.009 | 0 | 33.333 |

| CREDIT UNION | 0.004 | 0 | 33.333 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Casillas, C.S.; Espinoza-Sánchez, R.; López-Sánchez, J.A.; Aguilar-Navarrete, P. Competitive Integration of Social Tourism Enterprises Through an Organizational Management System: The Case of El Jorullo in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. Systems 2024, 12, 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12120549

Peña-Casillas CS, Espinoza-Sánchez R, López-Sánchez JA, Aguilar-Navarrete P. Competitive Integration of Social Tourism Enterprises Through an Organizational Management System: The Case of El Jorullo in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. Systems. 2024; 12(12):549. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12120549

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Casillas, Carlos Salvador, Rodrigo Espinoza-Sánchez, José Alejandro López-Sánchez, and Perla Aguilar-Navarrete. 2024. "Competitive Integration of Social Tourism Enterprises Through an Organizational Management System: The Case of El Jorullo in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco" Systems 12, no. 12: 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12120549

APA StylePeña-Casillas, C. S., Espinoza-Sánchez, R., López-Sánchez, J. A., & Aguilar-Navarrete, P. (2024). Competitive Integration of Social Tourism Enterprises Through an Organizational Management System: The Case of El Jorullo in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. Systems, 12(12), 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12120549