Combining Theory-Driven Realist Approach and Systems Thinking to Unpack Complexity of Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension Management in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Realist Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the key characteristics of the management of T2DM and HTN in LMICs?

- What programs have been implemented for the management of T2DM and/or HTN in LMICs?

- What are the mechanisms of T2DM and/or HTN management that lead to outcomes in different contexts?

2. Materials and Methods

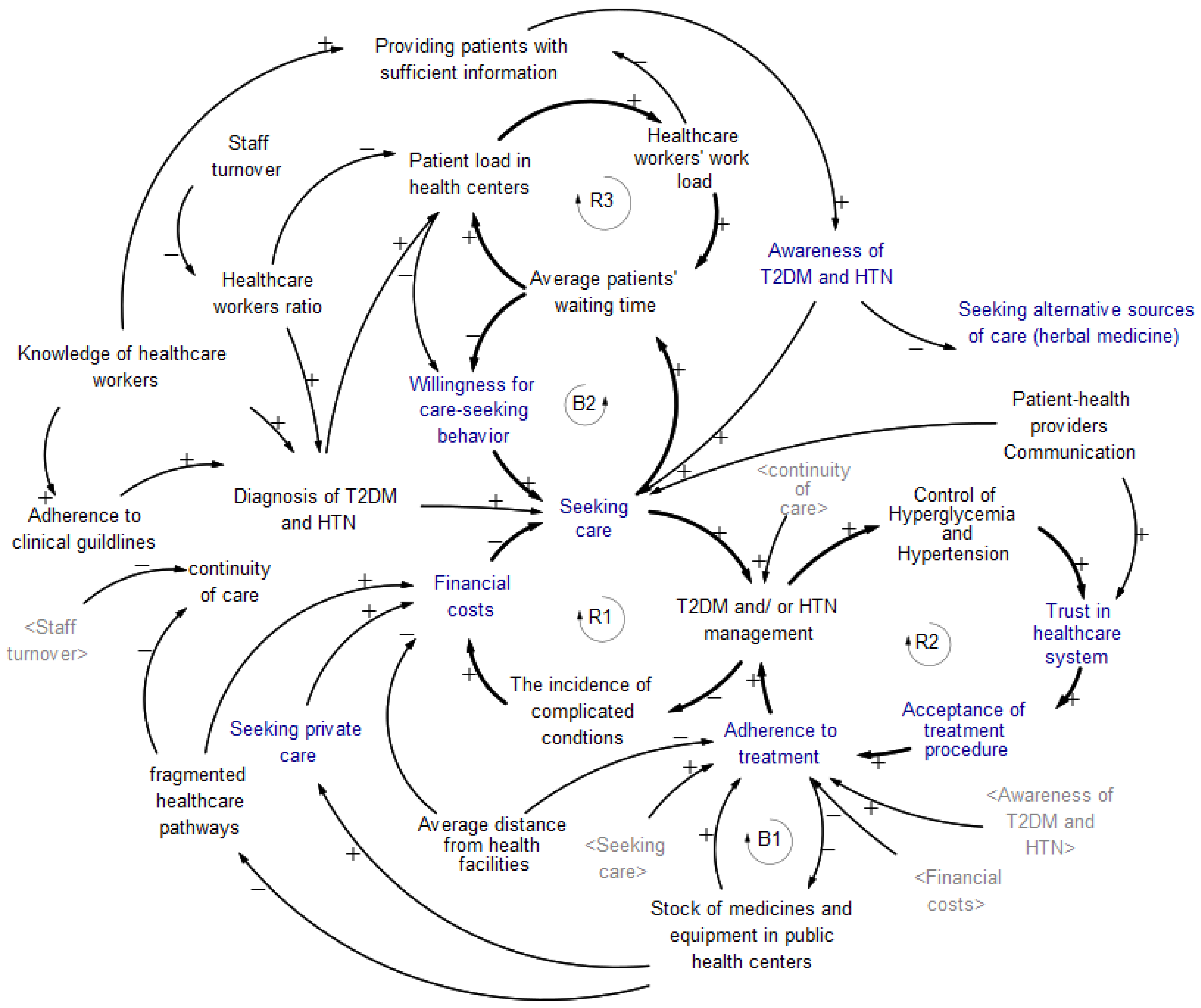

2.1. First Phase: Conceptualization of the Initial Program Theory to Address the Complexity of T2DM and HTN Management in LMICs Using a CLD

2.2. Second Phase: Search, Selection, Appraisal, Extraction of Evidence Regarding Programs for T2DM and HTN Management in LMICs

2.2.1. Search for Studies

2.2.2. Selection and Appraisal:

2.2.3. Extraction of Data

2.3. Analysis of Data and Development of the Middle Range Theory, i.e., a Revised CLD and then Validation through Group Model Building (GMB) Sessions

3. Expected Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Title | Target Condition | Study Setting | Study Type | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayked, Workneh and Kahissay, 2022 [28] | Sufferings of its consequences; patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in North-East Ethiopia, A qualitative investigation | Diabetes | Ethiopia | Qualitative study | 2022 |

| Beran, 2015 [29] | The Impact of Health Systems on Diabetes Care in Low and Lower Middle Income Countries | Diabetes | Low- and Lower Middle-Income Countries | Literature review | 2015 |

| Bhojani et al., 2013 [30] | Constraints faced by urban poor in managing diabetes care: patients’ perspectives from South India | Diabetes | India | Qualitative study | 2013 |

| Birabwa, Bwambale, Waiswa and Mayega, 2019 [31] | Quality and barriers of outpatient diabetes care in rural health facilities in Uganda—a mixed methods study | Diabetes | Uganda | Qualitative study | 2019 |

| Chary et al., 2023 [32] | Qualitative study of pathways to care among adults with diabetes in rural Guatemala | Diabetes | Guatemala | Qualitative study | 2023 |

| Chukwuma, Gong, Latypova and Fraser-Hurt, 2019 [33] | Challenges and opportunities in the continuity of care for hypertension: a mixed-methods study embedded in a primary health care intervention in Tajikistan | Hypertension | Tajikistan | Mixed methods study | 2019 |

| Dekker, Amick, Scholcoff and Doobay-Persaud, 2017 [34] | A mixed-methods needs assessment of adult diabetes mellitus (type II) and hypertension care in Toledo, Belize | Diabetes and hypertension | Belize | Mixed methods study | 2017 |

| Fort et al., 2021 [35] | Hypertension in Guatemala’s Public Primary Care System: A Needs Assessment Using the Health System Building Blocks Framework | Hypertension | Guatemala | Qualitative study | 2021 |

| Galson et al., 2023 [36] | Hypertension in an Emergency Department Population in Moshi, Tanzania; A Qualitative Study of Barriers to Hypertension Control | Hypertension | Tanzania | Qualitative study | 2023 |

| Gyawali, Ferrario, van Teijlingen and Kallestrup, 2016 [37] | Challenges in diabetes mellitus type 2 management in Nepal: a literature review | Diabetes | Nepal | Literature review | 2016 |

| Habebo et al., 2022 [38] | A Mixed Methods Multicenter Study on the Capabilities, Barriers, and Opportunities for Diabetes Screening and Management in the Public Health System of Southern Ethiopia | Diabetes | Ethiopia | Mixed methods study | 2022 |

| Kamvura et al., 2022 [39] | Barriers to the provision of non-communicable disease care in Zimbabwe: a qualitative study of primary health care nurses | Diabetes, hypertension, and depression | Zimbabwe | Qualitative study | 2022 |

| Karachaliou, Simatos and Simatou, 2020 [40] | The Challenges in the Development of Diabetes Prevention and Care Models in Low-Income Settings | Diabetes | Low-income countries | Literature review | 2020 |

| Kebede, Hailu, Kabeta and Mulugeta, 2023 [41] | Facilitators and barriers for early detection and management of type II diabetes and hypertension, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia: a qualitative study | Diabetes and hypertension | Ethiopia | Qualitative study | 2023 |

| Legido-Quigley et al., 2019 [42] | Patients’ experiences on accessing health care services for management of hypertension in rural Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka: A qualitative study | Hypertension | Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka | Qualitative study | 2019 |

| Lewis and Newell, 2014 [43] | Patients’ perspectives of care for type 2 diabetes in Bangladesh –a qualitative study | Diabetes | Bangladesh | Qualitative study | 2014 |

| Mendenhall and Norris, 2015 [44] | Diabetes care among urban women in Soweto, South Africa: a qualitative study | Diabetes | Soweto, South Africa | Qualitative study | 2015 |

| Mohseni et al., 2020 [45] | Challenges of managing diabetes in Iran: meta-synthesis of qualitative studies | Diabetes | Iran | Qualitative study | 2020 |

| Murphy, Chuma, Mathews, Steyn and Levitt, 2015 [46] | A qualitative study of the experiences of care and motivation for effective self-management among diabetic and hypertensive patients attending public sector primary health care services in South Africa | Diabetes and hypertension | South Africa | Qualitative study | 2015 |

| Musinguzi et al., 2018 [47] | Factors Influencing Compliance and Health Seeking Behaviour for Hypertension in Mukono and Buikwe in Uganda: A Qualitative Study | Hypertension | Uganda | Qualitative study | 2018 |

| Mwangome, Geubbels, Klatser and Dieleman, 2017 [48] | Perceptions on diabetes care provision among health providers in rural Tanzania: a qualitative study | Diabetes | Tanzania | Qualitative study | 2017 |

| Nang et al., 2019 [49] | Patients’ and healthcare providers’ perspectives of diabetes management in Cambodia: a qualitative study | Diabetes | Cambodia | Qualitative study | 2019 |

| Pati et al., 2021 [50] | Managing diabetes mellitus with comorbidities in primary healthcare facilities in urban settings: a qualitative study among physicians in Odisha, India | Diabetes with comorbidities | India | Qualitative study | 2021 |

| Pati, van den Akker, Schellevis, Sahoo and Burgers, 2023 [51] | Management of diabetes patients with comorbidity in primary care: a mixed-method study in Odisha, India | Diabetes with comorbidities | India | Mixed methods study | 2023 |

| Perera et al., 2019 [52] | Patient perspectives on hypertension management in health system of Sri Lanka: a qualitative study | Hypertension | Sri Lanka | Qualitative Study | 2019 |

| Quigley, Naheed, de Silva, Jehan and Samad, 2019 [42] | Patients’ experiences on accessing health care services for management of hypertension in rural Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka: A qualitative study | Hypertension | Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka | Qualitative Study | 2019 |

| Sato et al., 2023 [53] | Patient trust and positive attitudes maximize non-communicable diseases management in rural Tanzania | hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), and HTN/DM comorbidity | Tanzania | Qualitative Study | 2023 |

| Sharma et al., 2023 [54] | Determinants of Treatment Adherence and Health Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension in a Low-Income Urban Agglomerate in Delhi, India: A Qualitative Study | Diabetes and hypertension | India | Qualitative Study | 2023 |

| Vedanthan et al., 2016 [55] | Barriers and Facilitators to nurse Management of Hypertension: a Qualitative analysis from Western Kenya | Hypertension | Kenya | Qualitative Study | 2016 |

| Xiong et al., 2023 [56] | Factors associated with the uptake of national essential public health service package for hypertension and type-2 diabetes management in China’s primary health care system: a mixed-methods study | Diabetes and hypertension | China | Mixed methods study | 2023 |

| Yan et al., 2017 [57] | Hypertension management in rural primary care facilities in Zambia: a mixed methods study | Hypertension | Zambia | Mixed methods study | 2017 |

| Chang et al., 2019 [58] | Challenges to hypertension and diabetes management in rural Uganda: a qualitative study with patients, village health team members, and health care professionals | Diabetes and hypertension | Uganda | Qualitative study | 2019 |

| Barquera et al., 2013 [59] | Diabetes in Mexico: cost and management of diabetes and its complications and challenges for health policy | Diabetes | Mexico | Literature review of quantitative data | 2013 |

References

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, N.E.; Flood, D.; Marcus, M.E.; Theilmann, M.; Aung, T.N.; Agoudavi, K.; Aryal, K.K.; Bahendeka, S.; Bicaba, B.; Bovet, P. Diabetes risk and provision of diabetes prevention activities in 44 low-income and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative, individual-level survey data. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1576–e1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, J.R.; Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: Clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.R.; Lackland, D.T.; Niebylski, M.L. High blood pressure: Why prevention and control are urgent and important—A 2014 fact sheet from the World Hypertension League and the International Society of Hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2014, 16, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastra, G.; Syed, S.; Kurukulasuriya, L.R.; Manrique, C.; Sowers, J.R. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: An update. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2014, 43, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldsetzer, P.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Marcus, M.-E.; Ebert, C.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Wesseh, C.S.; Tsabedze, L.; Supiyev, A.; Sturua, L.; Bahendeka, S.K. The state of hypertension care in 44 low-income and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study of nationally representative individual-level data from 1· 1 million adults. Lancet 2019, 394, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Kondal, D.; Rubinstein, A.; Irazola, V.; Gutierrez, L.; Miranda, J.J.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Lazo-Porras, M.; Levitt, N.; Steyn, K. A multiethnic study of pre-diabetes and diabetes in LMIC. Glob. Heart 2016, 11, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Monat, J.P.; Gannon, T.F. What is systems thinking? A review of selected literature plus recommendations. Am. J. Syst. Sci. 2015, 4, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H. Introduction to Systems Thinking; Pegasus Communications: Waltham, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury, D.W.; Hirsch, G.B.; Vega, C.; Schwartz, C.E. Understanding social forces involved in diabetes outcomes: A systems science approach to quality-of-life research. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renmans, D.; Holvoet, N.; Criel, B. No mechanism without context: Strengthening the analysis of context in realist evaluations using causal loop diagramming. New Dir. Eval. 2020, 2020, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwashana, A.S.; Nakubulwa, S.; Nakakeeto-Kijjambu, M.; Adam, T. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: Understanding the dynamics of neonatal mortality in Uganda. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, R.; Borghi, J.; Semwanga, A.R.; Binyaruka, P.; Singh, N.S.; Blanchet, K. How to do (or not to do)… using causal loop diagrams for health system research in low and middle-income settings. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Malone, J.; McCormack, B.; Hutchinson, A.M.; DeCorby, K.; Bucknall, T.K.; Kent, B.; Schultz, A.; Snelgrove-Clarke, E.; Stetler, C.B.; Titler, M. Realist synthesis: Illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R.C.; Nanavati, J. Realist review: Current practice and future prospects. J. Res. Pract. 2016, 12, R1. [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh, J. Realist synthesis for public health: Building an ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist synthesis—An introduction. ESRC Res. Methods Program 2004, 2, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10 (Suppl. S1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Westhorp, G.; Pawson, R. Protocol-realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: Evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Buckingham, J.; Pawson, R. RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health, O. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kwong, J.S.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Sun, F.; Niu, Y.; Du, L. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: A systematic review. J. Evid.-Based Med. 2015, 8, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P.S.; Hovmand, P.S. Group Model Building and Community-Based System Dynamics Process; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bayked, E.M.; Workneh, B.D.; Kahissay, M.H. Sufferings of its consequences; patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in North-East Ethiopia, A qualitative investigation. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, D. The impact of health systems on diabetes care in low and lower middle income countries. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2015, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojani, U.; Mishra, A.; Amruthavalli, S.; Devadasan, N.; Kolsteren, P.; De Henauw, S.; Criel, B. Constraints faced by urban poor in managing diabetes care: Patients’ perspectives from South India. Glob. Health Action 2013, 6, 22258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birabwa, C.; Bwambale, M.F.; Waiswa, P.; Mayega, R.W. Quality and barriers of outpatient diabetes care in rural health facilities in Uganda—A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, A.N.; Nandi, M.; Flood, D.; Tschida, S.; Wilcox, K.; Kurschner, S.; Garcia, P.; Rohloff, P. Qualitative study of pathways to care among adults with diabetes in rural Guatemala. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e056913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, A.; Gong, E.; Latypova, M.; Fraser-Hurt, N. Challenges and opportunities in the continuity of care for hypertension: A mixed-methods study embedded in a primary health care intervention in Tajikistan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, A.M.; Amick, A.E.; Scholcoff, C.; Doobay-Persaud, A. A mixed-methods needs assessment of adult diabetes mellitus (type II) and hypertension care in Toledo, Belize. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, M.P.; Mundo, W.; Paniagua-Avila, A.; Cardona, S.; Figueroa, J.C.; Hernández-Galdamez, D.; Mansilla, K.; Peralta-García, A.; Roche, D.; Palacios, E.A. Hypertension in Guatemala’s public primary care system: A needs assessment using the health system building blocks framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galson, S.W.; Pesambili, M.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Manavalan, P.; Hertz, J.T.; Temu, G.; Staton, C.A.; Stanifer, J.W. Hypertension in an Emergency Department Population in Moshi, Tanzania; A Qualitative Study of Barriers to Hypertension Control. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, B.; Ferrario, A.; van Teijlingen, E.; Kallestrup, P. Challenges in diabetes mellitus type 2 management in Nepal: A literature review. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 31704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habebo, T.T.; Jaafaripooyan, E.; Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Foroushani, A.R.; Gebriel, S.Y.; Babore, G.O. A Mixed Methods Multicenter Study on the Capabilities, Barriers, and Opportunities for Diabetes Screening and Management in the Public Health System of Southern Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 3679–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamvura, T.; Dambi, J.M.; Chiriseri, E.; Turner, J.; Verhey, R.; Chibanda, D. Barriers to the provision of non-communicable disease care in Zimbabwe: A qualitative study of primary health care nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Karachaliou, F.; Simatos, G.; Simatou, A. The challenges in the development of diabetes prevention and care models in low-income settings. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, T.; Hailu, D.; Kabeta, A.; Mulugeta, A. Facilitators and barriers for early detection and management of type II diabetes and hypertension, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 6, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Naheed, A.; De Silva, H.A.; Jehan, I.; Haldane, V.; Cobb, B.; Tavajoh, S.; Chakma, N.; Kasturiratne, A.; Siddiqui, S. Patients’ experiences on accessing health care services for management of hypertension in rural Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.P.; Newell, J.N. Patients’ perspectives of care for type 2 diabetes in Bangladesh—A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, E.; Norris, S.A. Diabetes care among urban women in Soweto, South Africa: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, M.; Shams Ghoreishi, T.; Houshmandi, S.; Moosavi, A.; Azami-Aghdash, S.; Asgarlou, Z. Challenges of managing diabetes in Iran: Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Chuma, T.; Mathews, C.; Steyn, K.; Levitt, N. A qualitative study of the experiences of care and motivation for effective self-management among diabetic and hypertensive patients attending public sector primary health care services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musinguzi, G.; Anthierens, S.; Nuwaha, F.; Van Geertruyden, J.-P.; Wanyenze, R.K.; Bastiaens, H. Factors influencing compliance and health seeking behaviour for hypertension in Mukono and Buikwe in Uganda: A qualitative study. Int. J. Hypertens. 2018, 2018, 8307591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangome, M.; Geubbels, E.; Klatser, P.; Dieleman, M. Perceptions on diabetes care provision among health providers in rural Tanzania: A qualitative study. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nang, E.E.K.; Dary, C.; Hsu, L.Y.; Sor, S.; Saphonn, V.; Evdokimov, K. Patients’ and healthcare providers’ perspectives of diabetes management in Cambodia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Pati, S.; van den Akker, M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Sahoo, K.C.; Burgers, J.S. Managing diabetes mellitus with comorbidities in primary healthcare facilities in urban settings: A qualitative study among physicians in Odisha, India. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; van den Akker, M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Sahoo, K.C.; Burgers, J.S. Management of diabetes patients with comorbidity in primary care: A mixed-method study in Odisha, India. Fam. Pract. 2023, 40, cmac144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; de Silva, C.K.; Tavajoh, S.; Kasturiratne, A.; Luke, N.V.; Ediriweera, D.S.; Ranasinha, C.D.; Legido-Quigley, H.; de Silva, H.A.; Jafar, T.H. Patient perspectives on hypertension management in health system of Sri Lanka: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Nakamura, K.; Kibusi, S.; Seino, K.; Maro, I.I.; Tashiro, Y.; Bintabara, D.; Shayo, F.K.; Miyashita, A.; Ohnishi, M. Patient trust and positive attitudes maximize non-communicable diseases management in rural Tanzania. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Mariam, W.; Basu, S.; Shrivastava, R.; Rao, S.; Sharma, P.; Garg, S.; Mariam, W. Determinants of Treatment Adherence and Health Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension in a Low-Income Urban Agglomerate in Delhi, India: A Qualitative Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e34826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedanthan, R.; Tuikong, N.; Kofler, C.; Blank, E.; Kamano, J.H.; Naanyu, V.; Kimaiyo, S.; Inui, T.S.; Horowitz, C.R.; Fuster, V. Barriers and facilitators to nurse management of hypertension: A qualitative analysis from western Kenya. Ethn. Dis. 2016, 26, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Xiong, S.; Jiang, W.; Meng, R.; Hu, C.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Cai, C.; Zhang, X.; Ye, P.; Ma, Y. Factors associated with the uptake of national essential public health service package for hypertension and type-2 diabetes management in China’s primary health care system: A mixed-methods study. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2023, 31, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.D.; Chirwa, C.; Chi, B.H.; Bosomprah, S.; Sindano, N.; Mwanza, M.; Musatwe, D.; Mulenga, M.; Chilengi, R. Hypertension management in rural primary care facilities in Zambia: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Hawley, N.L.; Kalyesubula, R.; Siddharthan, T.; Checkley, W.; Knauf, F.; Rabin, T.L. Challenges to hypertension and diabetes management in rural Uganda: A qualitative study with patients, village health team members, and health care professionals. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquera, S.; Campos-Nonato, I.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.; Lopez-Ridaura, R.; Arredondo, A.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Diabetes in Mexico: Cost and management of diabetes and its complications and challenges for health policy. Glob. Health 2013, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories | Drivers | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-related system factors (demand side) | Awareness | Awareness of population affected by T2DM and HTN |

| Acceptability | Patients adopting treatment procedure | |

| Patients’ willingness to attend the health facilities | ||

| Seeking care | Seeking for alternative sources such as herbal medicine and private care | |

| Affordability | Financial burden due to medications and medical supplies, examination fees, healthcare visits and transportation fees | |

| Health care Providers related system factors (supply side) | Availability | Lack of essential clinical facilities for DM care |

| Out of stock of medicines and supplies | ||

| Shortage of equipment and laboratory services | ||

| Shortage and/or turnover of healthcare workers | ||

| Accessibility | Distance from health facilities (geographical distance) | |

| Knowledge | Knowledge of healthcare professionals on DM and HTN care | |

| Providing patients with sufficient information | ||

| Compliance | Compliance of health professionals to clinical guidelines | |

| Timeliness | Long waiting time due to providers’ work load | |

| Integration | Discontinuity between health center and district facilities | |

| Fragmented healthcare pathways and referrals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ehteshami, F.; Cassidy, R.; Tediosi, F.; Fink, G.; Cobos Muñoz, D. Combining Theory-Driven Realist Approach and Systems Thinking to Unpack Complexity of Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension Management in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Realist Review. Systems 2024, 12, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12010016

Ehteshami F, Cassidy R, Tediosi F, Fink G, Cobos Muñoz D. Combining Theory-Driven Realist Approach and Systems Thinking to Unpack Complexity of Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension Management in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Realist Review. Systems. 2024; 12(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleEhteshami, Fatemeh, Rachel Cassidy, Fabrizio Tediosi, Günther Fink, and Daniel Cobos Muñoz. 2024. "Combining Theory-Driven Realist Approach and Systems Thinking to Unpack Complexity of Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension Management in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Realist Review" Systems 12, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12010016

APA StyleEhteshami, F., Cassidy, R., Tediosi, F., Fink, G., & Cobos Muñoz, D. (2024). Combining Theory-Driven Realist Approach and Systems Thinking to Unpack Complexity of Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension Management in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Realist Review. Systems, 12(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12010016